Foster Dickson's Blog, page 7

August 1, 2024

Another Batch of New Works in “Nobody’s Home”

For Immediate Release

August 1, 2024

Nobody’s Home will publish three new works!

On August 10, 2024, the online anthology Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore is adding three new works of creative nonfiction by writers in the South. With a focus on the beliefs, myths, and narratives in Southern culture during the five-plus decades since 1970, these new works constitute the anthology’s fifth expansion.

The three contributors are Margaret Donovan Bauer, DeLane Phillips, and Pilar DiPietro, each of whom have had essays published in the anthology previously. Set in Tennessee and Louisiana, Bauer’s essay discusses gender roles and relationships in the 1980s. Phillips’s essay is set in the early 1970s and looks back at her mother’s habits as a homemaker. DiPietro tells us about a visit to a healing springs in rural South Carolina.

Editor Foster Dickson is proud to offer these additional essays that center on beliefs, myths, and narratives in the modern South. To learn more about the project, its focus, and its goals, you can read Foster’s introduction to the project “Myths are the truths we live by,” or other posts in his editor’s blog Groundwork. Writers who are still interested in adding their own voices to the anthology should read the submission guidelines to find out how to submit. The next Open Submissions Period for creative nonfiction will begin in April 2025, though reviews and interviews will be considered year-round.

The newly published works will be rolled out on social media on Saturday, August 10, and can also be accessed on the Index page later that day.

July 27, 2024

My review of “From Every Stormy Wind that Blows” by S. Jonathon Bass

I was proud to review historian S. Jonathon Bass’s new book From Every Storm Wind that Blows for the Alabama Writers Forum and just got word that the review is posted. The book was published by LSU Press in early 2024 and has the subtitle “The Idea of Howard College and the Origins of Samford University.” Bass is a professor at Samford, which is a Baptist university in Birmingham, and the author of He Calls Me by Lightning: The Life of Caliph Washington and the Forgotten Saga of Jim Crow, Southern Justice, and the Death Penalty (2017).

I was proud to review historian S. Jonathon Bass’s new book From Every Storm Wind that Blows for the Alabama Writers Forum and just got word that the review is posted. The book was published by LSU Press in early 2024 and has the subtitle “The Idea of Howard College and the Origins of Samford University.” Bass is a professor at Samford, which is a Baptist university in Birmingham, and the author of He Calls Me by Lightning: The Life of Caliph Washington and the Forgotten Saga of Jim Crow, Southern Justice, and the Death Penalty (2017).

July 25, 2024

My review of “Glass Cabin” by Tina Mozelle Braziel and James Braziel

I was proud to review James and Tina Mozelle Braziel’s new book Glass Cabin for the Alabama Writers Forum and just got word that the review is posted. The book was published by Clyde Hill Publishing in 2024. The authors’ website describes them as “a husband-and-wife writing team,” and the publisher’s description explains that the book “chronicles the thirteen years [they] spent building their home out of secondhand tin, tornado-snapped power poles, and church glass on Hydrangea Ridge.” Tina Mozelle Braziel’s recent collection Known by Salt was awarded the Philip Levine Poetry Prize. James Braziel teaches at University of Alabama at Birmingham, and his story collection This Ditch-Walking Love received the Tartt Fiction Award.

I was proud to review James and Tina Mozelle Braziel’s new book Glass Cabin for the Alabama Writers Forum and just got word that the review is posted. The book was published by Clyde Hill Publishing in 2024. The authors’ website describes them as “a husband-and-wife writing team,” and the publisher’s description explains that the book “chronicles the thirteen years [they] spent building their home out of secondhand tin, tornado-snapped power poles, and church glass on Hydrangea Ridge.” Tina Mozelle Braziel’s recent collection Known by Salt was awarded the Philip Levine Poetry Prize. James Braziel teaches at University of Alabama at Birmingham, and his story collection This Ditch-Walking Love received the Tartt Fiction Award.

July 23, 2024

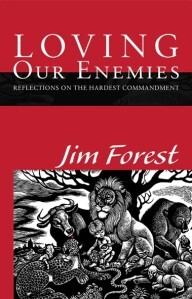

Reading: “Loving Our Enemies” by Jim Forest

Loving our Enemies:

Loving our Enemies:

Reflections on the Hardest Commandment

by Jim Forest

My rating: 5 out of 5 stars

I first came across the late Catholic peace activist Jim Forest when I read his book The Root of War is Fear: Thomas Merton’s Advice to Peacemakers a few years ago. And as will happen, after I bought that one, more of the author’s books were suggested by the ever-present algorithm. This one caught my eye. Forest has worked with groups like the International Fellowship of Reconciliation and Dorothy Day’s Catholic Worker. This book, one among several he has written, focuses on what really might be Jesus’s “hardest commandment”— to release ourselves from feeling “enmity” toward people who have wronged us or angered us, toward people whose actions or ideals we oppose, toward anyone we regard as an enemy by choosing to love them instead. It wouldn’t be hard at all to take a dogmatic or preachy approach to such a topic, yet Forest does it with humanity and with historical and textual evidence, while acknowledging that actually doing what he describes is never easy and is often not acceptable to others.

Loving our Enemies is organized into the three sections: “Thistles and Figs,” “Nine Disciplines of Active Love,” and an “Epilogue.” The first section sets the groundwork by rooting a desire for peace in the Bible, Catholic thought, and real life. The opening chapter provides block quotes of those passages in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, when Jesus gives his admonition to “do good to those who hate you.” Subsequent chapters offer a philosophical basis, then Forest describes what he calls “the Gospel of John Wayne.” This perspective says that justice comes when the good guys go out and find the bad guys and beat ’em down! Forest’s counterargument, which is accompanied by examples as proof, reminds us that the John Wayne perspective doesn’t lead to long-term peace and doesn’t align with Christianity. In Part II, we get direct instruction, which begins with the fundamental advice to look hard at ourselves and our own behavior. Forest suggests in the first chapter of Part II that his reader should make a list of “enemies” then consider praying for them. He also asks his reader to consider that these “enemies” may be not the main problem, that the actual source of derision might be the person in the mirror. Reminding us of the story of the road to Emmaus, which he brought up in Part I, the author uses this metaphor of our eyes being opened to move his reader forward, toward peace of mind and forgiveness. To end, Part III is very short, only a few pages that offer a brief story to think about. We learn about an elderly couple in Tennessee whose home was invaded by an escaped convict. Rather than giving in to fear or resorting to violence, the couple chose to embrace the man, feed him, pray with him, and convince him to turn himself in without incident. Thus, his life was changed, and so was theirs.

As I was reading, I thought several times about the old veterinarian I worked for in college, who used to say, “Foster, it’s easy to be nice to nice people.” His meaning was usually literal – to comment positively about someone he liked – but he also said it to acknowledge that it’s hard to be nice to crappy, rude, mean, or grouchy people. Doc was right in the worldly sense, but in Forest’s opening pages, there’s this from Matthew, chapter 5: “For if you love those who love you, what reward have you?” I think that Jesus was saying, I know it’s hard to be nice, kind, or compassionate to people who are being ugly, but we should anyway. Growing up in the South, I’ve always heard the opposite: You’ve got to stand up for yourself, or You just gon’ take that? A tidal wave of societal norms tells us to return fire, to hit back, because people know who’ll put up with it and who won’t. Furthermore, it’s hard to put up with ugly behavior for the simple reason that it feels pretty bad to get treated poorly; we don’t want to stand there and take it or just walk away. Forest does remind us that there is nothing wrong with defending ourselves, it is retaliation and hate that we should avoid. Why? Because Jesus said so, and Christians should try to do what Jesus tells us to do.

Though I don’t know how effective I will be at living out its lessons, I liked this book. Loving our Enemies is easy to read, clear in its message, and well-supported by real-life examples. Forest cites a number of people and incidents, some familiar and others that were new to me, and he draws from a range of sources: saints, historical figures, conscientious objectors, ordinary people. I was a little concerned when his opening pages describe how his parents were communists, and I started off wondering how that political perspective might be integrated. I was glad as I moved through the chapters that he was most interested in breaking down the walls between human beings and in reminding his readers to be compassionate toward all people, even those we are told to despise or fear, even ourselves. All in all, I didn’t agree with everything I read, but I will also acknowledge that Jim Forest probably didn’t write this book to be pleasing.

Read More:Pope John Paull II’s The Gospel of Life

Henry Nouwen’s The Prodigal Son

Pope Francis’s Laudato Si

Dorothy Day’s The Long Loneliness, Part One, Parts Two and Three

July 16, 2024

Dirty Boots: “Democracy in America”

For the past few months, I’ve been watching old episodes of Northern Exposure when I don’t have anything else to do, and it looks like I’m on my way to watching all six seasons. I’ve liked this show since the early ’90s, when I was still in high school, but didn’t pay as much attention to it as I did in the late ’90s, when A&E was showing re-runs. By then, I had finished college and was working nights in restaurants, and those re-runs came on late-morning about the time I got out of bed. Purely by coincidence, the show became part of my morning routine— coffee and Northern Exposure. These days, in the age of streaming, re-runs in a daily time slot are passé, but marked by old habits, my version of bingeing takes months, not days. I like to digest what I’ve seen before taking in another episode. And Northern Exposure is a show worth savoring.

Not long ago, it was an episode from February 1992 titled “Democracy in America” (season 3, episode 15) that caught my attention. The nation would have been heading into the Clinton-Bush election when the episode first aired. Thirty-two years and five presidents later, I have been watching in the months leading up to a Trump-Biden rematch, amid overheated debates about democracy in America. In the episode, long-time mayor Holling Vincoeur is challenged for his job as Cicely’s leader by local misanthrope Rita Taggart, who is angry that Holling never installed the stop sign she asked for five years earlier. The disgruntled woman is a loner who openly disdains other people, while Holling is well-liked and often-seen since he is the owner and proprietor of the town’s only bar. The outcome of such a matchup seems obvious, yet a challenge is issued, so an election must be held. Holling’s role as mayor is so miniscule that Joel Fleischmann, the New York City doctor who has by this point been in the town for a few years, wasn’t even aware that they had a mayor. Yet, the couple-hundred townspeople stir themselves up at the prospect of this choice. Ed Chigliak, in particular. He finds himself suffering from anxiety over doing his forthcoming duty. This is the first election in his lifetime. (Joel is also flabbergasted by this: there has never been an election held in the tiny town in Ed’s lifetime!)

Not long ago, it was an episode from February 1992 titled “Democracy in America” (season 3, episode 15) that caught my attention. The nation would have been heading into the Clinton-Bush election when the episode first aired. Thirty-two years and five presidents later, I have been watching in the months leading up to a Trump-Biden rematch, amid overheated debates about democracy in America. In the episode, long-time mayor Holling Vincoeur is challenged for his job as Cicely’s leader by local misanthrope Rita Taggart, who is angry that Holling never installed the stop sign she asked for five years earlier. The disgruntled woman is a loner who openly disdains other people, while Holling is well-liked and often-seen since he is the owner and proprietor of the town’s only bar. The outcome of such a matchup seems obvious, yet a challenge is issued, so an election must be held. Holling’s role as mayor is so miniscule that Joel Fleischmann, the New York City doctor who has by this point been in the town for a few years, wasn’t even aware that they had a mayor. Yet, the couple-hundred townspeople stir themselves up at the prospect of this choice. Ed Chigliak, in particular. He finds himself suffering from anxiety over doing his forthcoming duty. This is the first election in his lifetime. (Joel is also flabbergasted by this: there has never been an election held in the tiny town in Ed’s lifetime!)

But it is the ever-eloquent Chris Stephens who makes the episode. Those who are fans may remember, but for those who aren’t: Chris came to the tiny Alaska town years earlier after skipping parole in West Virginia. He had been a petty criminal who had spent a little time in prison, so as a convicted felon, he had lost his voting rights. Moreover, Chris couldn’t afford to appear on the government’s radar anyway. While Ed is suffering the throes and Joel is trying once again to satisfy his dismay, Chris is more excited about the election than anyone. On the radio, he is reading from Walt Whitman and pontificating about American freedom. By the end of the episode, Chris has cut off his long hair, shaved his scruffy face, and put on a suit-and-tie just to go stand in the polling place and experience the event. Ultimately, he is the character who makes us understand that freedom and the right to vote may be valued and appreciated most by people who don’t have them.

I’ll spoil it, since most readers won’t go and watch anyway: Holling loses the election, but only by a few votes. The campaigning has the side effect of revealing some long-held bitterness over past conflicts with the generally affable bar owner, individual resentments over an old slight here or an old argument there. When people are asked to make their choice official, we see a community divided and voters driven by a variety of motives. No one likes Rita, nor does she like them. She doesn’t really want the job, and the people don’t really think she’ll be a good mayor. But grouchy, antisocial Rita Taggart wins the mayoral election because some people want to see change, while others are simply voting against Holling. It’s a microcosm of our country, then as now, showing voters and their many ways of reasoning, and thus was aptly titled: “Democracy in America.”

Democracy is messy, and despite its beauty and value, it exposes unfortunate antagonisms, both individual and societal. It is by far the best system for governance, but its application can show us for what we too often are: lazy, uninformed, selfish, unforgiving, capricious, manipulative. I remember, back during George HW Bush’s presidency, the main fact that Americans knew about our president – the leader of the free world – was that he didn’t like broccoli. Across time, voter turnout statistics show that massive numbers of voters don’t show up at all. Some voters are influenced not to support the candidate they prefer because they don’t see that he or she can win— which is what makes the candidate unable to win! In Alabama, where I live, crossover voting had to be criminalized, because some voters were using the primaries as a way to infiltrate their opposing party’s process with a ballot for the weakest candidate. Alabama is also one of only six states that still allows straight ticket voting, which offers a single political-party check box on the ballot instead of having to mark every race. That practice’s issues and flaws have led to its abolition in sixteen states since the mid-1990s, but in Alabama, 67% of voters cast a straight-ticket ballot in 2022. It was just as true in that fictional Alaska town of the 1990s as it is in our nation today: there are few things that reveal our imperfections, our quirks and inconsistencies, our humanity, warts and all, like an election will.

June 20, 2024

Southern Movie 69: “Shanty Tramp” (1967)

Though it is relatively tame by current standards, 1967’s Shanty Tramp was an “adult movie” in its day. I first came across this film when I was writing about Alabama governor Albert Brewer’s attempts in 1970 to close down theaters that were showing any kind of porn films. After a legal battle typical of Alabama politics, the courts ruled that Brewer had done the right thing the wrong way, so ultimately he lost, and theaters around the state returned to showing these films. In viewing it today, Shanty Tramp is more than a dirty movie. Considering its 1967 release date alongside its unstated location in “Dixie” and its wild plot, the film becomes a commentary on the lives of poor whites in the South and an indictment of the culture’s taboos surrounding interracial sex. Directed by Joseph G. Pietro and starring Eleanor Valli, two Italians whose brief lists of credits are mainly comprised of throwaway potboilers, Shanty Tramp wasn’t made to be a hall-of-famer, but it does provide an example of how outsiders used the Southern paradigm to create storylines.

Shanty Tramp opens with a shot of a young woman in nice knee-length dress walking down a sidewalk at night. A white gospel choir is belting out “When the Saints Go Marching In,” which gives the audience the sense that this story is set in the South. (It’s kind of a poor directorial choice, considering the song’s themes and the film’s plot.) We see this woman from behind, and when the scene pauses for the credits to roll, we are looking at her rear end in the tight dress. When the motion resumes, she saunters past a few men, teasing them silently, smiling at some, but none of them give her more than a look.

Across the street, she sees a tent revival with a stereotypically boisterous white Southern preacher shouting about God and hell and sin and damnation to an audience that sits passively and listens. Our main character, whose name is Emily, goes into the tent but not before a group of bikers roar past in the dark. She ignores them and, in the revival, stays in the back rather than taking a seat. She smiles at the preacher, and we understand that it isn’t his message she is interested in. Also in the back is a young black man named Daniel who is standing with his mother. He keeps eyeing Emily with sideways glances, and his mother tells him to stop looking at the “shanty tramp.” Soon, the preacher gets to his real purpose, which is passing the collection baskets, and he admonishes the small crowd that their faith will be reflected in the amount of cash they put in the baskets.

After the revival, Daniel and his mother leave, but Emily sticks around. She comes on to the preacher, who takes the bait and offers to let her come back to his trailer with him. His sidekick, an older man who does little more during the film than shake his head in dismay, reminds him that there’s still work to do, closing things down. So, the preacher delays his gratification and sends Emily on her way.

Still, Emily is on the hunt for some action! On the sidewalk across the street, she runs into a drunkard, who turns out to be her father. He stumbles around and slurs, seeming to want his daughter to acknowledge him and to behave herself. She berates him and is disgusted by his behavior, and he does little more than say weakly that she shouldn’t treat her father like that. The conversation is brief, she walks away, and he takes a pull from a pint bottle in his coat pocket.

Nearby is a little café-bar that appears to be the local hangout for young people. The lettering across the front of the building declares that it is open from 8:00 AM until 2:00 AM. Inside, Emily finds a young man sitting at the bar by himself, so she walks past the half-dozen young couples who are dancing to the latest tunes from the jukebox. Emily orders a beer and entices the young man to dance with her.

Meanwhile, those bikers from earlier pull into the parking lot. Their leader is a tough guy, and he goes in first with the other four or five following him. These characters remind us of Buzz’s gang in Rebel without a Cause or the bikers in The Wild Angels: a mixture of kooky and badass. Inside, the first couple that the leader encounters is Emily and her newfound beau, and he grabs Emily away from their dancing, while his pals beat the guy up. Everyone else stands by and does nothing. The bikers then take over the place, each grabs a girl for himself, and they spend the rest of the night making out and drinking beers. When it comes time to pay up, they stiff the pitiful guy working there and make their way into the dark to consummate their new relationships. Before she leaves, Emily goes over the pouting proprietor and gets the key to the stock room.

Meanwhile, those bikers from earlier pull into the parking lot. Their leader is a tough guy, and he goes in first with the other four or five following him. These characters remind us of Buzz’s gang in Rebel without a Cause or the bikers in The Wild Angels: a mixture of kooky and badass. Inside, the first couple that the leader encounters is Emily and her newfound beau, and he grabs Emily away from their dancing, while his pals beat the guy up. Everyone else stands by and does nothing. The bikers then take over the place, each grabs a girl for himself, and they spend the rest of the night making out and drinking beers. When it comes time to pay up, they stiff the pitiful guy working there and make their way into the dark to consummate their new relationships. Before she leaves, Emily goes over the pouting proprietor and gets the key to the stock room.

Across town, the young black man Daniel, who we saw with his mother at the revival, is sitting on his front steps, dreaming sadly of Emily. His mother comes outside to tell him that his dinner is cold, but he isn’t hungry. She tells him again to stop thinking of that woman, and he blows her off. His mother then reminds him of the trouble he could get in, even mentioning that his father was lynched when Daniel was too young to remember. Daniel is troubled by this, but we know that he won’t let his infatuation go.

After everyone else has wandered away, following the gang leader’s instructions to go find an alley to get together in, Emily tells her man that she can take him to the back room where there is a mattress. The pair doesn’t know that Daniel is watching from across the street. The biker likes Emily’s idea, but once they get back there, he doesn’t want to pay for her services. She argues with him that their deal involves sex for money, but he isn’t going to pay. She fights him off, but he is too violent for her. He rips her clothes and is going to rape her. Just then, Daniel comes in! He pulls the guy off of Emily and beats him up, knocking him unconscious. Then Emily sets her sights on Daniel, while biker boy lays on the ground nearby. Now, Daniel can be the one who pays and gets some love. But no, Daniel doesn’t want that. He takes off his button-down shirt and gives it to her to cover up, since her dress is torn open. She tells the shirtless man that he can come get his shirt later, in her barn.

Meanwhile, Emily’s father has wandered his drunk self into the tent revival and has been persuaded to change. After listening to the preaching for a bit, he begins to weep and tells the whole crowd that his daughter behaves so badly. She is out there right now, doing those awful things, he tells them. So he stumbles out of the tent to go find her and stop her. The preacher folds his hands and thanks the Lord in Heaven that his good work has been rewarded.

Unfortunately for poor lovestruck Daniel, he goes to the barn later to meet Emily. She is there in his shirt, and he comes in cautiously. Though no sex is shown, we seem them lying together, naked (shown from the waist up) and sleepy, after a brief cut-to. But it isn’t long before Emily’s father shows up. Emily begins to holler to her father for help, saying that she tried to fight him off but Daniel was too strong. Daniel is over to the side, putting his clothes on and wondering, WTF?? When the time came, Emily decides to save her own skin and throw Daniel under the bus. Rather than fight the young black man himself, her father runs to gather a mob.

At this point, we are forty-five minutes into the seventy-minute film. The scandalous nature of the story must have been shocking in the late 1960s. We have a young woman in the South who is anything but a Southern belle, and her character’s actions are counterbalanced against two Southern stereotypes: the unscrupulous itinerant preacher and good-for-nothing, drunken white trash. The biker gang is somewhat out of place in this paradigm, but not too badly. These supporting characters serve to move Emily forward into the act that will be her undoing: interracial sex. Here, Daniel is the good guy, the naive young black man whose lovelorn foolishness causes him to make bad decisions, primarily giving in to temptation and believing in the goodness of a woman who has none.

The rest of Shanty Tramp is fairly predictable, but not altogether. Emily begins to cry after her father leaves and tells Daniel to run into the woods. She wants him to escape, she claims. Back in town, the old drunkard ambles around, finding no one at first, then he returns to the tent, where a crowd is still gathered. He riles them up, and they get organized to find Daniel. Back at the barn, Emily is still lying around topless when her father comes back with the sheriff and a doctor. She refuses to be treated by the doctor, which is a strange sign to the men, especially since she only wants them to “get him” and since she knows where he went. (Why would a rapist intent on escape tell his victim where he would be?)

As the white people in town try to find Daniel, who is slinking through the dark to avoid detection, Emily and her father are back at home. He is putting together the pieces of what he has seen and what he knows. He may be a shiftless drunk but he begins to understand what his daughter was up to. Emily in turn throws a temper tantrum, but her father takes his leather belt and beats her.

Nearby, we see Daniel stumble upon a moonshiner’s shack, as we near the end. Daniel steals a car from the moonshine guys and drives so fast in his getaway attempt that he crashes and dies. We expected things to go like this for Daniel, but here the plot twists dramatically for Emily. Her father, who has just beaten her, decides that since other men get to have Emily, he will too. He yanks off her dress and as he begins to unbutton his own clothes, Emily pulls a knife from the kitchen sink and stabs him repeatedly. Now, she goes on the run. However, the ending comes in a very different way for Emily than for Daniel. Emily comes upon the preacher in his trailer during her escape. The road show is packed up and heading out, and she stows away with him. The car and camper roll away, with the seedy preacher and his new mistress riding comfortably in back. Where Daniel died in a fiery car crash, Emily and her sinful ways will live on.

Shanty Tramp traffics in Southern stereotypes to create a noir/porn movie. That aspect of it isn’t as interesting as the way that the film treats the issue of interracial love and sex. Thinking about it in blunt terms, if a young black man were at a tent revival with his mother in the South in the late 1960s, and she caught him looking at a white woman, the mother’s reaction would not be calm and measured. At that time, any black Southern mother, especially one whose husband had been lynched, would be extremely worried about what her son might be thinking or doing. And moreover, the young man would know – just from living in small-town Southern culture – what he was risking, even if he were just caught looking. This might be explained away by the fact that Daniel and his mother are the only black people we see, but I have to remark that it is highly unlikely that you could find a Southern small town with only two black people in it. Nonetheless, this young man is smitten and thinks that the relationship can work out if he pursues it, which is unrealistic. (Hopefully, we all see the parallel with Daniel’s name being the same as the Biblical character in the lion’s den.)

Then we have Emily, a young white woman who would just as soon have casual sex with a black man as a white man. Although love affairs did happen between black men and white women in the Jim Crow South, I doubt if anyone would regard Emily’s feelings as love. She is baldly opportunistic and generally a terrible person. One of the flaws in the storytelling in this film regards that fact. Emily didn’t wake up that morning and decide to start behaving badly. In a small Southern town, everyone would have known her by this age, presumably her late teens or early 20s. Her presence at a tent revival would have been noticed immediately, and her presence in the little café would have been, too. But through the film, no one seems to know her. The only exception is the café proprietor who seems to understand that she uses his storeroom for prostitution. Perhaps the only reason to feel sorry for Emily, from what we know about her in this movie, is that her own father tries to rape her, and she is forced to kill him to resist that happening.

As a document of the South, Shanty Tramp is just wrong enough to be unbelievable. In small Southern towns, where people lived for generations, everyone’s past mattered every day and in every situation. Somehow, though, Emily and her father seem to blend into the crowd in the way that people could in a big city. What I’m saying is: there are Southern elements to this story, but they’re utilized incorrectly. But, if the filmmakers were trying to make a potboiler or a porno, it probably didn’t matter to them. Slapping the “hicksploitation” label on this film is more than fair, since the actress playing Emily spends about ten to fifteen minutes of the seventy without her top on. To be candid, that – not accuracy – was what the audiences were paying for.

If you have enjoyed reading or viewing the content on this website,consider this link your invitation to toss a few bucks in the hat.

June 15, 2024

The Open Submissions Period for “Nobody’s Home” ends today.

This year’s Open Submissions Period for Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore closes today. All submissions made between April 15 and June 15, 2024 will receive a response in July. Accepted submissions will be published in August 2025.

This year’s Open Submissions Period for Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore closes today. All submissions made between April 15 and June 15, 2024 will receive a response in July. Accepted submissions will be published in August 2025.

This was the sixth Open Submissions Period for Nobody’s Home. The project was founded in 2020, and the first three Open Submissions Periods were held within a year’s time, from the latter half of 2020 through the first half of 2021. Subsequently, in 2022 and 2023, unsolicited submissions have been read in the spring, with accepted works published each summer.

Today, Nobody’s Home features more than fifty essays that discuss a variety of beliefs, myths, and narratives that have affected or have arisen from Southern culture since 1970. In addition, the project offers secondary-education lesson plans for English and Social Studies classrooms, suggestions for documentaries about Southern culture, and Groundwork, the editor’s blog.

June 7, 2024

“Conrack,” Fifty Years Later

Today, June 7, 2024, marks the fiftieth anniversary of the release of the 1974 film Conrack. I wrote about this movie last year for the editor’s blog on Nobody’s Home. This discussion focuses on the film’s narratives and the myths it perpetuates.

The 1974 feature film Conrack explores then-common beliefs about the Geechee people on South Carolina’s barrier islands. Based on the book The Water is Wide by Pat Conroy, the story follows his trek into this isolated culture when he accepted a teaching job in a two-room schoolhouse. As a white teacher in an all-black classroom that holds grades five through eight, Conroy quickly finds two major hurdles to his work: first, the children are barely educated at all, and the school’s other teacher – a black female principal – vehemently expresses her views that these children are stupid and incapable of being educated. If those aren’t enough to stifle him, the white schools superintendent wants to counter Conroy’s lively and inclusive teaching style with an insistence on rigor, discipline, and corporal punishment. However, the determined young man pontificates daily in his own playful and vigorous way, and thus manages to instill some learning into the children’s lives, and in doing so, gets himself fired.

Though it is a quite a good movie, Conrack exposes unfortunate realities from its time, trafficking in early 1970s white liberal ideals about “saving” people in poor black communities. Pat Conroy, whose mispronounced last name gives us the film’s title, is the unorthodox instructor who will bring light into darkness through a potent mixture of caring, stubbornness, and joi de vivre. No ordinary teacher would accept this assignment, and our hero is no ordinary teacher. This narrative – now popularized in films like 1995’s Dangerous Minds and 2007’s Freedom Writers – tells us that impoverished schools in communities of color are completely hamstrung by the system and its operators, and so a wily interloper must open the door to knowledge and wisdom by defying the system. (These myths have been further perpetuated by other feel-good films featuring non-white educators, like 1988’s Stand and Deliver and 1989’s Lean on Me.) In Conrack, we also see two more stock characters that emerge again and again in these narratives: the realistic but hopelessly exhausted black educator whose aspiration is only the bare-bones basics, and the closed-minded superintendent whose willful allegiance to conformity pits him against any efforts at improvement.

The South’s schools are notorious for their comparatively low standing among American schools, and that fact is even more pronounced in rural communities and in communities of color. Seeing Southern states litter the bottom of the annual education rankings reifies the common belief that the South’s people are stupid, backwards, ignorant, or all three. Thus, we have a narrative that says that only teachers who defy authority can transcend accepted Southern norms, because the typically compliant and bureaucratic-minded teachers fail utterly. This narrative suggests that most teachers and other school officials are satisfied with failure, as evidenced by the results of their work— which is not true. While the tug-of-war between the uncommon educator and the rigid superintendent may be more interesting to watch than the daily practice of teaching and learning, this narrative omits the fact that the vast majority of teachers do their best with what they have, which is not much in poor communities, rural communities, and communities of color. Stories like the one in Conrack may show us the tension between the two extremes, but ultimately, it’s not the story of education in the South.

The South’s schools are notorious for their comparatively low standing among American schools, and that fact is even more pronounced in rural communities and in communities of color. Seeing Southern states litter the bottom of the annual education rankings reifies the common belief that the South’s people are stupid, backwards, ignorant, or all three. Thus, we have a narrative that says that only teachers who defy authority can transcend accepted Southern norms, because the typically compliant and bureaucratic-minded teachers fail utterly. This narrative suggests that most teachers and other school officials are satisfied with failure, as evidenced by the results of their work— which is not true. While the tug-of-war between the uncommon educator and the rigid superintendent may be more interesting to watch than the daily practice of teaching and learning, this narrative omits the fact that the vast majority of teachers do their best with what they have, which is not much in poor communities, rural communities, and communities of color. Stories like the one in Conrack may show us the tension between the two extremes, but ultimately, it’s not the story of education in the South.

June 4, 2024

Dirty Boots: Just Like Jim Stark’s Blues

In her short essay “Facing the world on fire” in this month’s issue of The Christian Century, Rachel Mann discusses the idea of choosing contemplation as a response to our modern socio-political conflicts, even in the face of criticism that this choice is a retreat, avoidance, the opposite of the action that is sorely needed. Mann, who is an Anglican priest and theologian, reminds readers that the word contemplation has its roots in the Greek word theoria, which means watching or seeing. In fact, argues Mann, contemplation is not inaction at all; it is an aspect of taking action— it is allowing ourselves a moment to step back from the problems and the division to look again at the situation with the benefit of distance and silence.

In her short essay “Facing the world on fire” in this month’s issue of The Christian Century, Rachel Mann discusses the idea of choosing contemplation as a response to our modern socio-political conflicts, even in the face of criticism that this choice is a retreat, avoidance, the opposite of the action that is sorely needed. Mann, who is an Anglican priest and theologian, reminds readers that the word contemplation has its roots in the Greek word theoria, which means watching or seeing. In fact, argues Mann, contemplation is not inaction at all; it is an aspect of taking action— it is allowing ourselves a moment to step back from the problems and the division to look again at the situation with the benefit of distance and silence.

As I was reading it, Mann’s essay reminded me of the police-station scene at the beginning of Rebel without a Cause. Jim Stark (played by James Dean) has been arrested for public drunkenness, and when his parents and grandmother arrive, they bicker all around him until he screams, “You’re tearing me apart!” The frustrated police officer Ray Fremick then takes Jim into an adjacent room, and while Jim calms down with a cup of water, they watch through a small window as the trio go at it. Nothing good will happen in that wild foray, everyone angrily blaming each other in turn. It is by stepping away, into silence, to watch and to see, that Jim and Ray get the best perspective on what is really going on. In that little side room, the officer begins to understand the teenager’s predicament, and so do we.

I also remembered, at the peak of the Black Lives Matter movement, how I would see on social media, Twitter especially, the sentiment that everyone who is “silent” is complicit in the wrongdoing. That narrow and incomplete understanding of political action implies that the only way to accomplish anything is to yell about it. Public protests and social media posts certainly have their place in making change, but so do quieter actions like reading credible information sources and listening to varied perspectives, both of which involve watching or seeing. Action has its place, as do rhetoric and speech, but so does contemplative silence. When the world gets like Ray Fremick’s little office, with everybody packed in tight and shouting, it’s time to step away to gain some clarity.

For about twenty years, I counted myself among those who were taking action. Starting in 2001, when I went to work at NewSouth Books, I participated in organizing events, creating resources, educating people, and helping to tell neglected stories. The world didn’t ask me whether I wanted to step away from it in March 2020. A microscopically tiny organism burst onto the scene, infecting and killing people, and governments everywhere decided that we would all experience some distance and silence. At that time, my life was full of action: a grant-funded student project on a neglected local history, a Literary Arts Fellowship project on myths in Southern culture, and a commissioned historical monograph on a long-standing educational institution. Yet, instead of the vibrant activity that such projects usually involve, the pandemic insisted upon distance and silence— far more than I wanted! Like millions of Americans, I had no choice but to succumb, and I found myself filling the time and the space with contemplation. Some of that contemplation was enlightening, some of it was painful. When we returned fully to in-person school in August 2022, I had changed, so had everyone else— the world had changed. I didn’t understand it then and don’t now. I don’t think anyone does. Which is why contemplation is so important today.

In Rebel Without a Cause, Jim Stark learns that no one around him has the answers he is looking for. He knows that his parents move the family regularly to avoid dealing with their problems and that they buy him expensive gifts to pacify his troubled mind. Jim’s parents push him to embrace middle-class normalcy as the solution to his problems. The swarthy troublemaker Buzz, who leads the small gang of toughs, invites Jim into their life of daring and danger, only to die in the “chickie run” he himself arranged. Pretty young Judy first harries Jim with teasing and mind games, but moves after Buzz’s death into sincerity and what we hope is love. Poor sad Plato, who just wants a friend, is so distraught by loneliness that he commits what we call today “suicide by cop.” The best answer ends up coming from the solemn police officer Ray Fremick, who invites true contemplation by asking Jim to set aside what others want or expect to consider instead what he thinks. Though the stone-faced lawman is an unlikely mentor to this confused teenager, he encourages the one thing that no one else does: look inside yourself for what is right. For Jim, action does not produce an answer, but contemplation might.

In the Transtheoretical Model of making change, there are five stages. Contemplation is the second one. In the first stage Precontemplation, a person is either unaware that there is a problem or is unwilling to acknowledge that there is. Next, in Contemplation, one starts thinking that maybe something is not what it should be and really does need to change. In Preparation then, possible solutions are sought, and during Action, attempts are made implement what seem to be most viable solutions. Finally, in Maintenance, there comes the effort not to revert back to the old way. Giving a nod to the detractors that Rachel Mann alludes to, if a person hits the Contemplation stage and never moves on, then yes, it is a retreat or avoidance. That would be like knowing you have to pee and not walking to the bathroom. (Then you’d have an even bigger problem!) Contemplation is a necessary part of the process that should lead to action— hopefully, the best action.

In the year or so since the pandemic ended, and since I’ve finished two of those three projects I listed above, I’ve been hanging back and watching other people take action while I spend time on contemplation. The world has been changed by movements like Black Lives Matter and #metoo, by a years-long pandemic that killed millions of people and devastated the lives of millions more, and by a growing sense of urgency about the Earth’s climate. And I have been changed by disruptions, societal and personal, that have disallowed the continuation of the way I had lived and worked before. I’ve been mighty quiet in the last few years, so quiet in fact that people some ask me when I see them in public, whether I’ve been OK. It’s not like you, they say. Well, it’s like me now.

In her recent essay, Rachel Mann writes that contemplation is about “seeking to perceive the world as it is [as] a work of education in the truth.” After Jim Stark and Judy have experienced the deaths of Buzz then Plato, nothing will be the same for them. They have known two young men whose lack of direction in life led to their untimely deaths. That’s the truth that they are changed by and have to live with. Though I’m no longer a teenager, I still understand Jim’s frustration at people who say, Why can’t you just live and think like me? Especially after a life-changing events have made that impossible. Quiet contemplation undertaken without interruptions or disturbance is not avoidance; it is a form of healing, before we go out and take on life’s challenges again, and it is necessary to ensure that the action we take is right.

May 26, 2024

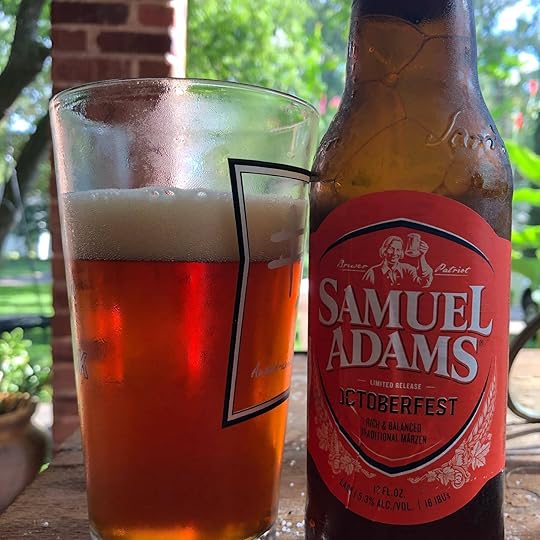

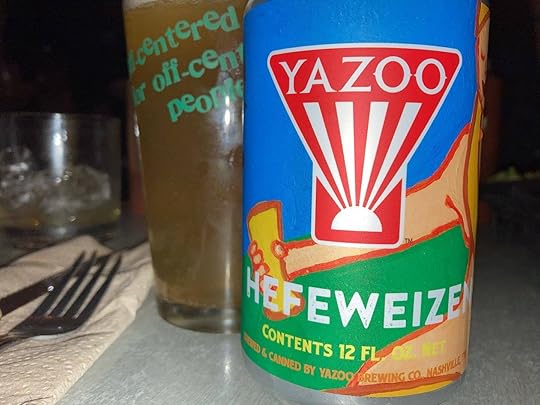

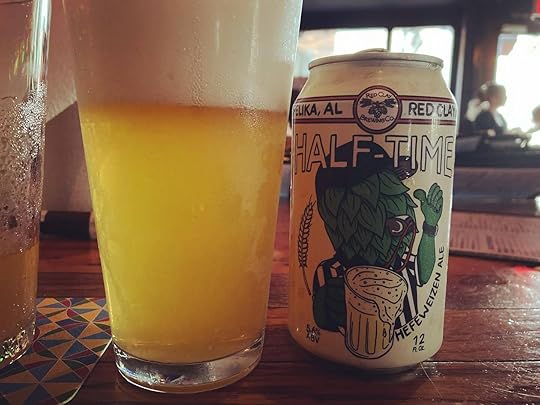

Craft Beers and Smart Phones

Ever since we got smart phones with cameras, I’ve snapped pictures of my beers, mainly because if I like one I don’t want to have to remember what it was. Some folks like selfies, others like documenting their good times with their friends . . . I like not forgetting which beers I enjoyed. Let this be a friendly reminder to have a happy Memorial Day weekend with something much, much, much better than White Claw or Michelob Ultra.