Foster Dickson's Blog, page 24

May 6, 2021

Groundwork, the editor’s blog of “Nobody’s Home”

“Groundwork,” the editor’s blog of Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore, features project updates, brief ruminations, long-form reviews of books, guidance for submitting writers, quotations from books, and other peripheral bits of interest related to beliefs, myths, and narratives in Southern culture. Because Nobody’s Home is an online anthology, not a print anthology, the format allows for an ongoing editor’s commentary, which in a book would be provided by a single introduction. This dynamic aspect of the project creates opportunities for me, as an editor, to keep the ideas flowing, growing, and evolving, without the limitations of a page count or publication date. And now, as COVID-19 and its associated travel restrictions ease up, I’ll hopefully be more able to include one of the original ideas behind the editor’s blog that I haven’t been able to add yet: to travel and interview ordinary people about beliefs, myths, and narrative. It is titled “Groundwork,” after all.

“Groundwork,” the editor’s blog of Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore, features project updates, brief ruminations, long-form reviews of books, guidance for submitting writers, quotations from books, and other peripheral bits of interest related to beliefs, myths, and narratives in Southern culture. Because Nobody’s Home is an online anthology, not a print anthology, the format allows for an ongoing editor’s commentary, which in a book would be provided by a single introduction. This dynamic aspect of the project creates opportunities for me, as an editor, to keep the ideas flowing, growing, and evolving, without the limitations of a page count or publication date. And now, as COVID-19 and its associated travel restrictions ease up, I’ll hopefully be more able to include one of the original ideas behind the editor’s blog that I haven’t been able to add yet: to travel and interview ordinary people about beliefs, myths, and narrative. It is titled “Groundwork,” after all.

Below is a sampling of the posts. Click on the links to visit the site and read the post.

April 2021: More Substance than Stereotype

March 2021: Reading Myth and Southern History, Volume 2: The New South

February 2021: Reading Alexander Lamis’ The Two-Party South

January 2021: Reading Stephen A Smith’s Myth, Media, and the Southern Mind

December 2020: Reading Jack Temple Kirby’s The Countercultural South

December 2020: The Looming Specter of the Dormant Voter

November 2020: Reading Charles Reagan Wilson’s Judgment & Grace in Dixie

November 2020: Work

November 2020: Reagan at Neshoba, August 1980

October 2020: Crazy, Wrong Madness

September 2020: A Personal Religion that Goes Public

September 2020: Narratives, Old and New

Forthcoming in May and June are posts on the South to a New Place anthology (literary criticism) and Matthew Lassiter’s The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South.

April 27, 2021

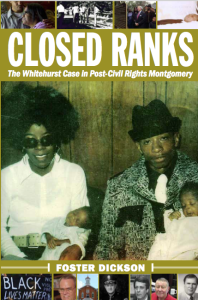

Summer Reading: “Closed Ranks”

Though you may not know his name, Bernard Whitehurst, Jr. was killed by a police officer in Montgomery, Alabama in December 1975. Whitehurst was black, the officer who shot him was white, and his death occurred during a search for a robbery suspect that resulted in a chase. Whitehurst was walking in the area, was mistaken for a suspect, and was then pursued. After being shot as he tried to climb a fence, he died among weeds and trash in the backyard of an abandoned house as the sun set in the late afternoon.

His family has been seeking justice ever since. Sadly, the Whitehurst Case was left unresolved. No officers were charged with his killing. The family’s 1976 civil lawsuit failed in federal court, and the appeal was denied. One city councilman’s resolution to make a financial settlement with the family was tabled indefinitely. Though the controversy over Whitehurst’s death did result in firings or resignations of police officers, the public safety director, and the mayor, an April 1977 special election brought Montgomery a new mayor, whose position on the Whitehurst Case was to move on. It has been forty-four years since that special election, and more than forty-five year since his killing.

As our country grapples with these issues of race and policing, I want to invite everyone to learn more about the Whitehurst Case by choosing Closed Ranks as one of your summer reading books this year. Then, join me, eldest son Stacy Whitehurst, and other Whitehurst family members for one of two talkbacks on Sunday, June 27 or Sunday, July 25 on Facebook Live. We will talk about the Whitehurst Case and its long-term legacy, then take questions from the audience.

As our country grapples with these issues of race and policing, I want to invite everyone to learn more about the Whitehurst Case by choosing Closed Ranks as one of your summer reading books this year. Then, join me, eldest son Stacy Whitehurst, and other Whitehurst family members for one of two talkbacks on Sunday, June 27 or Sunday, July 25 on Facebook Live. We will talk about the Whitehurst Case and its long-term legacy, then take questions from the audience.

Closed Ranks was published by NewSouth Books and is widely available. However, as a special promotion, Montgomery’s Read Herring bookstore is offering a discount on copies purchased directly from them. This discount will be available from May 1 through July 15. You can call the store at 334-834-3552 or email manager Mike Breen to take them up on that offer.

Links, times, and further information about the two Facebook Live events will be posted on my author page on Facebook.

April 14, 2021

The Great Watchlist Purge of 2021: A Springtime Progress Report

After publishing the original post on January 14, this is my three-month progress report on the Great Watchlist Purge of 2021. The watchlist had seventy-two titles in it when I made a resolution to try to whittle down this self-imposed cinematic to-do list. I’ve long had a habit to noting and stockpiling books, movies, whatever makes me think, “That could be cool, I need to look at later.” Then it gets out of hand . . .

The good news is that I’ve found and watched twenty-two of the seventy-two films from the original January list, and have only given up on four as being either unavailable or unwatchable. Of the twenty-one, two were from the 1960s, eleven from the ’70s, four from the ’80s, and five from the 2010s. I started out with movies that were readily available, ones streaming on Prime mainly, then searched other sources. Though it took a little effort, I was glad to find some of these films after believing they might not be available. The streaming service Tubi usually requires a subscription but has a watch-ads option on its Roku app. I found several of the films there. And a few appeared free on YouTube, surprisingly. Below are a few notes on the titles I’ve watched, with notes in gray.

Francesco (1989)

Mickey Rourke was not terribly convincing as Saint Francis, though Helena Bonham Carter did a good job in this movie. Told as a frame story, the action moves back and forth between past and present, as Francis’ early followers remember him. Good way to tell the story, I guess.

Born to Win (1971)

Born to Win tells a sad story in an episodic way. Karen Black is also in the film and plays the character I feel like I’ve seen her play a lot: the girl whose guy can’t act right and doesn’t treat her very well. The ending was particularly disappointing, didn’t resolve anything, and just left the main character sitting there.

Bruges-Le-Morte (1978)

Bruges-Le-Morte had a very 1970s feel to it. It was slow-paced, sometimes awkward, and, in some scenes, surreal and creepy. This extremely straight-laced guy gets sucked in by a group of carnies because he thinks he sees his wife, who he believes to be dead. It becomes kind of like that Bob Dylan song “Ballad of a Thin Man”— what have you gotten yourself into, Mr. Jones?

Is the Man Who is Tall Happy? (2013)

I watched some of this documentary on Noam Chomsky because he always has interesting ideas, even if I don’t agree with them. The animation was stellar, but there was one glaring problem: it was very difficult to hear and understand what was being said. The director speaks with a thick French accent, and Chomsky mumbles. It stinks since I was more interested in Chomsky’s ideas than the director’s animation, but what I got was the opposite.

Quiet Days in Clichy (1970) This movie was rambling, raunchy, and filthy, like the book. Unlike Rip Torn in Tropic of Cancer, the guy who played Henry Miller this time actually looked like him. I’ll also add: I was surprised to see that Country Joe McDonald (of “Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” fame) made this movie. The soundtrack began with his music, but later switched to jazz for some reason, then ended with acid rock. The majority of the movie was sex scenes and walking around Paris.

This movie was rambling, raunchy, and filthy, like the book. Unlike Rip Torn in Tropic of Cancer, the guy who played Henry Miller this time actually looked like him. I’ll also add: I was surprised to see that Country Joe McDonald (of “Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” fame) made this movie. The soundtrack began with his music, but later switched to jazz for some reason, then ended with acid rock. The majority of the movie was sex scenes and walking around Paris.

The Wicker Man (1973)

This was a well-done thriller. I wouldn’t classify it as horror, since the premise was more suspenseful than frightening. It’s very British, with a stiff-upper-lip police officer trying to goad a passel of odd, uncooperative villagers into telling him what he needs to know. Ultimately, he wishes he didn’t find out what he came to find out . . .

The Baby (1973)

If I didn’t enjoy weird ’70s horror movies, I’d have turned this one off pretty quickly. But it had all the things that make people like me enjoy ’70s horror movies: bad acting, a bizarre premise, cheap effects. The ending was unexpected, I will say that for the movie.

Heavy Traffic (1973)

I had seen Heavy Metal before, but never Fritz the Cat, so I had little background in how gritty and harsh Bakshi’s portrayals of urban life were. This movie is basically about a young white guy who draws cartoons and who wants to have this one particular black woman in the neighborhood to be his girlfriend. The opening and closing portions are live action, but the majority of the film is animated. It’s one man’s perspective on the inner city in the 1970s. I watched it all the way through but probably won’t watch it again, and wouldn’t really recommend it.

Six Pack (1982)

When I found a way to watch this movie, I made my wife and kids watch it with me. Of course, my wife was enthusiastic, remembering it from our childhood, but my kids were clearly bored. Sure, Six Pack is dated and cheesy but it also brought back great memories. I can remember my dad busting a gut laughing when the mouthy kid says that Brewster has gone “to shake the dew off his lily.” This movie is very Gen-X in the Deep South, and that’s why I like it.

The Sky is Gray (1980)

This short film had a very made-for-TV/classroom-use feel. There wasn’t much to it. At only forty-five minutes long, it’s a screen version of a short story. But I couldn’t escape the feeling that the story was better than the adaptation.

The Effects of Gamma Rays on Man in the Moon Marigolds (1970)

Not only is Paul Zindel’s stage play really powerful, it won a Pulitzer Prize, so I would have thought that they’d stick closer to the actual script. This film was kind of like when you see “based on true events” and know that they’ve changed whatever they felt like changing. It might have been based on Zindel’s play, but I’m not even sure that it should have had the same title. I expected better.

Boxcar Bertha (1972)

Boxcar Bertha is based on the autobiography of a real woman who lived through the Depression. This adaptation was an early ’70s crime movie directed by Martin Scorsese. Given the cast – David Carradine, Barbara Hershey – and the director, I expected the movie to be sharp. But it wasn’t. It was cheesy and felt forced.

Pink Motel (1982)

This movie was exactly the poorly acted 1980s comedy I hoped it’d be. I got several good chuckles, and the feathered hair, one-off jokes, lack of a cohesive plot, and dated music were perfect!

The Rebel Rousers (1970), Ride in the Whirlwind (1968), and Psych Out (1968)

I would call Ride in the Whirlwind an existential western. After watching it, I still have no idea why it was titled that. There was nothing about a whirlwind in the movie. Jack Nicholson played the main character but never really stood out, just sort of mumbled his dialogue in his nasally way without much fanfare.

Despite having a strong cast – Jack Nicholson, Bruce Dern, Diane Ladd, Harry Dean Stanton – The Rebel Rousers is pretty weak. It seems at first like it’ll be Wild Angels with a biker gang coming into a small town, but then there’s a side plot about two unmarried lovers who are having a baby. The movie seems like one of the early to mid-’60s things that try to show how cool and wacky the hip crowd is, but then they end up being dangerous, too.

Of these movies, Psych Out is easily the best of the three. There’s actually a story. Sure, there’s also lots of trippy music-heavy scenes with little relevance to the plot, but each time the movie gets back to the main storyline. The acting and production value are also reasonably good in this one.

Mood Indigo (2013)

This was visually and creatively one of most interesting movies I’ve seen in a long time. Even though I had seen Tautou in Amelie, I had not expected this to be similarly quirky but it was far more quirky. I really liked this movie.

Lucky (2017)

Lucky was not exciting, but it was quite good. How much action can you derive from a story about an old man who lives alone, walks everywhere he goes in his small town, and finds out that he’s dying? But action isn’t really what it’s about this time. This time, it was about lonely guy who is greater than what the people around him realize he is. This one has some quirky moments – David Lynch’s character is obsessed with an old turtle he can’t find, and Ed Begley play Lucky’s perhaps-too-blunt doctor – but the movie is mostly sentimental with a few odd parts sprinkled in.

Big Sur (2013)

I liked this movie more than I thought I would. I was so fond of Kerouac’s work when I was younger that I hesitate to watch any dramatizations of his books or his life, but I said “What the heck” when this one came available on Amazon Prime. The story was well done, the casting was appropriate, and the characterizations weren’t over done. Kerouac was such a sad guy . . .

The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh (1971)

Once again, 1970s horror-thrillers— I enjoy them. And ones from Europe are even better, with the stylized cinematography, zooming in on people’s faces, playing the sound of people’s footsteps too loud, overly long chase scenes, and stuff like that.

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Minnesota (2017)

This was a very, very good film. I’m sorry that I didn’t get off my rear end and watch it sooner. Frances McDormand is her usual wry, chilly self, and Sam Rockwell plays a great asshole cop. The story was dark but quirky, too. Woody Harrellson’s police chief character adds a lot of humanity to the story, too.

Belladonna of Sadness (1973)

The artistry in the animation was something like I’d never seen – I don’t watch anime, mind you – but I hadn’t expected so much of the story to be sexual. Some of the long, trippy, acid rock scenes could have been cut down or tamed a bit. I don’t get offended by sexual material in movies, but at some point, I go, “OK, OK, I get it, now get back to the story.” That’s how I felt watching Belladonna of Sadness. Also, the little squeaky noise that the main character made constantly got on my nerves, but that’s neither here nor there.

Those were the ones I watched, but there four that I gave up on:

Mondo Cane (1962)

I tried watching this again and quickly found myself fast-forwarding to find something interesting. The opening scene, where the guy drags the dog by its neck in front of cages full of barking dogs is disturbing enough. As for wanting to watch the rest of it . . . not so much. Beside that, a lot of what I did see was incredibly dull.

Macunaima (1969)

I started watching this again and only got a short way into it before admitting that I didn’t really want to watch it. If I understood the context better, maybe it’d make more sense. I had to give up on this one.

Alabama (1985)

I doubt if I’ll ever find this movie, and even if I did, I won’t understand the Polish that they’re speaking. I wasn’t terribly interested in it anyway. The title just made me wonder why a love story from Poland was titled “Alabama.”

How Tasty Was my Little Frenchman (1971)

And . . . like Macunaima, I started this one too – again – and quickly gave up.

Those are the titles I knocked off the list. But there’s also bad news, at least it’s bad when you’re trying to reduce the number of items in a list. In addition to the twenty-two movies I watched and the four I scrapped, I’ve continually added more since January— almost as many as I’ve watched! Of these fifteen that were added, I went ahead and watched two of them.

Thomasine & Bushrod (1974)

This blaxploitation film was directed by Gordon Parks, Jr. and is billed as a Bonnie & Clyde story in the early 1900s. This is different from most blaxploitation films, which are typically urban and set in the then-modern 1970s.

Fox Style (1973)

I started watching Fox Style, but quit before it was over. This might the worst, cheapest blaxploitation movie ever made. And that’s saying a lot for that genre.

Zachariah (1971)

Although it was a new addition to the list, I went ahead and watched Zachariah, which is a rock n’ roll western that has cameos from James Gang and Country Joe & the Fish. I feel pretty certain that it came up as a suggestion because I was watching hippie films and because Quiet Days in Clichy had Country Joe associated with it. The movie kind of reminded me of Hair a little bit.

Deadlock (1970)

This Western came up as a suggestion at the same time as Zachariah. It’s a German Western, so we’ll see . . .

The Tenant (1976)

The only other Roman Polanski movie I’ve ever seen was The Fearless Vampire Killers, which was stupid and not funny. I don’t know why I added this movie to the list but I figured I’d give it a chance.

Landscape in the Mist (1988)

This Greek film about two orphans won high praise. I haven’t tried to find a subtitled version yet, it may be out of reach.

The Blood of a Poet (1930)

Jean Cocteau’s bohemian classic. I remember reading about this film in books that discussed Paris in the early twentieth century, but I never made any effort to watch it. I’m not as interested in European bohemians as I once was, but if the film is good, it won’t matter.

Phantom of the Paradise (1974)

I can’t tell what to make of this movie: Phantom of the Opera but with rock n roll in the mid-’70s?

Abby (1974)

Another blaxploitation movie. I’ve seen most or all of the significant and well-known ones, and most of the lesser-known ones, and am more recently finding and watching the pretty obscure ones. In this one, a woman is possessed.

The Magic Garden of Stanley Sweetheart (1970)

If Joe Delassandro is in a movie, you know it’s going to be weird and sketchy.

Alone in the Dark (1982)

A good ol’ 1980s horror movie about escapees from an insane asylum. It should be terrible! I can’t wait!

The Hunger (1983)

I’d seen this movie before but thought I’d watch it again— a vampire movie with David Bowie, Catherine Deneuve (from Belle Du Jour), and Susan Sarandon (from Rocky Horror Picture Show).

It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books (1988)

This is a Richard Linklater movie I’d not heard of. It predates Slacker.

Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb (1971)

As I’ve already shared, I just like ’70s horror movies. We’ll see if this one is any good.

White Star (1983)

This biopic has Dennis Hopper playing Westbrook. I couldn’t pass it up.

The Spider Labyrinth (1988)

One of the reviewers under mentioned this Italian horror/thriller in his review of another movie. He had high praise for it. Once again, we’ll see what happens.

Since this is a progress report, I’ll end it this way: I started with seventy-two movies, watched twenty-two and scrapped four, which means that I knocked out a little over one-third of the list. But I added fifteen more but watched two of those . . . which leaves watchlist with just over sixty movies now. Mathematically, I made a little progress— three steps forward, two steps back.

April 6, 2021

Southern Movie 54: “Trapper County War” (1989)

If you were to ask me what the 1989 movie Trapper County War was about, I might tell you to imagine My Cousin Vinny meets The A Team. The story centers on two young guys from New Jersey who are passing through North Carolina on their way to California. For some reason, they’ve decided to take two-lane backroads instead of the interstate and have also decided to travel south when they’re destination is to the west. Those two poor decisions land them in rural Carolina and put them in hot water— very hot water. The movie was directed by Worth Keeter, known at the time for the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers and Silk Stalkings TV series, and it features TV mainstay Rob Estes, Patrick Swayze’s brother Don, and Ernie Hudson (the fourth Ghostbuster).

Trapper County War starts off with our two heroes driving mountainous backroads in the fall or winter. The trees are barren, and no cars pass by, but they’re still having fun, goofing off, and making the best of being generally lost. Soon, they enter fictional Trapper County, which appears to be in the western part of North Carolina. Their map is useless, since the two zany city boys can’t figure out what road they’re on. Briefly, they pull into a dirt driveway and honk the horn, calling the residents outside. One of the young guys Bobby (Noah Blake) asks for directions, but the hillbilly who comes out onto the porch just spits and stares at them while his blank-faced wife stands behind him, mouth agape. So, with a big, smartass grin, Bobby replies, “Thank you!” and they drive off again. That night, they sleep in a hay barn, but while they sleep, a shadowy man observes them there but leaves in silence.

The next morning, the pair come into a small riverside town that appears to be a county seat. We see a large, courthouse-like building from the aerial view; otherwise, there is a standard Main Street. The guys ease down the main drag and comment that every business is named Ludigger. They surmise that one family must own everything there, so they jokingly remark that they should try the Ludigger Cafe. Which they then do.

Inside, a pretty, black-haired waitress is singing along with the radio in the empty café. The boys come in the front door, but the waitress doesn’t see them, so they sneak to their seats and observe her performance. When she does realize they’re there, she gets a little miffed, but the two young men quickly begin to flirt their way out of it. They tell her that they play in the hottest band in Hoboken – a place she has never heard of – and that they’re heading for California, where they’ll certainly be famous. The pretty waitress takes a shying to Ryan (Rob Estes) over Bobby, and soon she is sitting in a booth with them. Their conversation reveals that there will be a dance that night, so Ryan wants to stay a while to attend the soiree. Bobby objects, but Ryan insists.

Outside, Bobby and Ryan find a man leaning in the passenger door of their truck, going through it. They say something to him, and when he emerges, it is a sheriff’s deputy. But this time, it’s not the usual swarthy, big-bellied hoss of a Southern sheriff, but an angry-looking young redneck with a shaggy mullet. Of course, the lawman wants to know who they are and why they’re there, and the boys smart off when replying to him. The tension is broken by a big, smiling small-towner who ambles by, asks what’s going on, and tells the travelers not to mind Walt Ludigger (Don Swayze), he’s just like that. Bobby asks what’s up with these Ludiggers, and the big fellow tells him that they own the whole town. He advises that they’d be better off leaving ASAP. The ominous warning is hanging in the air: move along, outsiders, you’re not welcome here.

The scene then shifts away so we can understand the context in the town. The big fellow from the sidewalk ambles into local barber shop, where we meet Sheriff Sam Frost (Bo Hopkins). There are some chuckles had over a domestic conflict that resulted in a killing, but the stone-faced sheriff isn’t amused. After the sheriff leaves, the barber and the big man comment that he’s an odd cat. Meanwhile, the sheriff heads over to the graveyard where he puts flowers down on his wife’s grave, saying, “Happy anniversary, babe.” From there, he goes to the Ludigger Cafe, where the barber shop lunkheads are now at the counter. The woman behind the counter – not Lacy, this is a grown woman – treats him coldly about being taken out on a date, and we learn two things from her outburst: first, they’re relationship is not moving to the next level like she wants, and second, she wants them to get married and leave town.

That evening, we see that Ryan had no intention to moving along, even though Bobby is in favor of making tracks. It’s the evening now, and they have put on their cool trench coats and wacky button-downs, gelled their hair, and gone to the dance to impress the ladies. To their chagrin, officer Walt is trying to pick up on Lacy, who isn’t hearing it. Bobby and Ryan step in, and of course, Walt gets angry and wants to fight. They offer Lacy to take her for a ride instead of staying at the dance. Some man who looks like a high school principal intervenes, but the tension isn’t abated. Walt walks away, and an uneasy Lacy agrees to ride with them as the hometown country band plays on.

As if we hadn’t guessed, Walt and his buddies are outside in the parking lot. Walt comes out from behind a dumpster and goads Ryan into a fight. Ryan kicks his ass with some kind of cheap judo, and Walt’s friends sense they don’t want more of the same. Who wants to get their ass kicked by a guy in pleated, acid-washed jeans? At this point, we’re wondering whether Lacy is naive or just stupid. She has agreed to leave a crowded public place with two guys from out of town, one of whom has just shown how violent he can be. But lucky for her, they’re nice guys, and she spills her life story to Ryan. She tells him how she and her brother were adopted by the Ludiggers, who are terrible people. Ryan tells her that she should come to California with them. She agrees.

Back at the Ludigger home, Lacy goes in to get her clothes before they skip town. When she walks in wearing Ryan’s trench coat, she finds Ma and Pa Ludigger at the table with Walt, who is busted up, and her brother. Pa silently drinks his moonshine out of a jar, while Ma lights into Lacy as Walt sits scowling. Lacy’s brother is there, but remains helpless. After Lacy goes upstairs, Walt leaves to go back into town.

While Ryan and Bobby wait in the truck behind an outbuilding, Lacy packs her bags in a cloth sack, goes out the second-floor window, and drops down into Ryan’s arms. They sneak away, but Lacy breaks it to them that the only way out of town is through the town of Ludigger. Back in town, the dance has let out, so traffic is heavy, and Walt spies them while he is directing traffic. Of course, Walt tries to stop them, but Ryan speeds through, which leads to a police chase on a rural roads outside of town. The Jersey boys and their new gal pal are busted.

Once they’re stopped, the levelheaded sheriff Sam rattles off a series of reasonable charges, but Walt screams back at him that they’ll be charged with kidnapping. Lacy is not yet eighteen! Once the two outsiders are in cuffs, Sam tells Walt to drive their red truck and Lacy back to town, but Walt has other ideas. Walt attempts to sexually assault Lacy, who cries out and is saved by the sheriff. Walt is clearly embarrassed by being caught by his boss and tells Lacy, “We’ll finish this later.” Now we know that Walt is both a butthole and a guy who wants to molest his adopted sister.

Unfortunately for Bobby and Ryan, they’re in the clink. Bobby is shouting for somebody to come help them but Ryan tells him to hush. Then a deputy comes and tells them they’re free to go. Great! Not really. The boys are led out, but when they try to go out the front door, the deputy tells them that they need to go out the back, where their truck is. Okay. Not really. In the alley, the local yokels are waiting on them. Bobby and Ryan have been released so they can be lynched.

As Bobby and Ryan try to walk out of the alley, two trucks pull in, blocking their way. It’s the Ludigger family! Walt jumps out with a pump shotgun and loads the boys into the back, face down. They drive the two offenders into the woods, to what looks like an abandoned work site, and Ma begins to berate Ryan: “You think we’re just a bunch of dumb hicks . . . Well, we ain’t dumb.” She then snatches his earring out of his ear, as Walt hold him, then she tells Pa to get the sledge hammer out of the truck.

We see that Ma is the boss, and a mean one at that. Nearby Lacy’s brother Elmore has the shotgun on Bobby, while Walt and Pa hold Ryan. Ma readies the hammer, telling Bobby, “When I get through with you, you won’t even be able to feed yourself!” But as she goes to swing, Bobby shoves Elmore into them, causing Ma to miss Ryan and clunk Elmore on the temple, killing him. Ryan and Bobby make a run for it, but Ma now has the shotgun and blasts Bobby, killing him too. Somehow, though, her second blast misses Ryan entirely and he escapes. But, he’s living a city boy’s worst nightmare: he is alone in the woods at night and being chased by hillbillies who want to kill him.

At this point, Trapper County War is only halfway through. We would think that the conflict would work itself out pretty quickly, since we have a guy from New Jersey in the North Carolina woods in the winter with no food or shelter. But there are still some wild cards left to play: the sheriff Sam Frost . . . and that shadowy figure who observed them in the barn at the beginning of the movie.

At this point, Trapper County War is only halfway through. We would think that the conflict would work itself out pretty quickly, since we have a guy from New Jersey in the North Carolina woods in the winter with no food or shelter. But there are still some wild cards left to play: the sheriff Sam Frost . . . and that shadowy figure who observed them in the barn at the beginning of the movie.

Next we see our antagonists, they’re in Sam Frost’s office trying to explain away the deaths of Elmore and Bobby. Ma Ludigger tries to claim that Bobby and Ryan were the aggressors. When little brother didn’t come home last night, they claim, they went looking for him and found the murder scene. Sam is bothered by the fact the Ludiggers have moved things around, altered the scene, and also by the fact that the Jersey boys didn’t seem to have a gun the night before. Sam remarks to Walt that he checked out the truck when they arrested the pair, but Walt says he hadn’t looked behind the seat. Despite Ma Ludigger’s hard-charge for her brand of “justice,” Sam makes it clear that he’ll try to find out what really happened.

Meanwhile, Ryan has slept in the woods and is now traipsing around. Somehow a boy from Hoboken knows to climb a tree on a ridgeline to get a better view of the terrain. He finds a two-lane road, where he tries to flag down a truck that won’t even slow down. Soon, Ryan finds a backroads gas station where an old grease monkey is working on a white Jeep, and he asks about the phone. The scowling old man tells him that the pay phone is all there is, and Ryan makes a call to New Jersey. But the old man overhears, goes inside, and suddenly the call is cut off.

Inside the gas station, Ryan tries to complain to the gas station man, but the old fellow doesn’t seem interested. He tells Ryan that it’s a party line and that the operator will probably call him back once his folks are on the line. Ryan is apprehensive and fidgety, which prompts the old guy to remark about two out-of-towners who killed a local boy last night. The man repeats what would be the Ludiggers’ version of events, and Ryan halfheartedly protests, trying to pretend simultaneously that he doesn’t know anything about it. It doesn’t take long for the man to say, “I didn’t introduce myself. I’m Ludigger, Billy Ludigger,” and he’s pointing a pistol at Ryan.

But Ryan thwarts his attempt at a capture by turning over a wire-framed potato chip rack on him! He then runs out the door, climbs in the Jeep, and speeds away just as sheriff’s car is coming. What ensues is a Dukes of Hazzard-style chase down dirt roads, with Walt half out of the passenger window, shooting at the Jeep from behind. After Ryan escapes by making a daring jump over a log wall that blocks the road, the sheriff’s car crashes. Walt then remarks that’s Ryan has gone into Jefferson territory. He may get himself done away with up there.

Ryan ditches the Jeep, which of course has rebel flag stickers in the window, and goes into the woods on foot. He is trying to start a fire by rubbing sticks together, when a black man (Ernie Hudson) appears out of nowhere to jump on him. Could this be Jefferson? After a few moments of Hollywood-style karate, the man grabs Ryan and asks, “What’re you doin’ on my mountain?” Ryan tries to explain, and Jefferson shrugs him off. Ryan desperately needs help, but Jefferson tells him to walk away, that the Ludiggers are his problem.

Once night has fallen, the Ludiggers have a half-dozen good ol’ boys at the house planning to hunt Ryan down. They allude to Sam Frost being a problem, but they’ll get the job done either way. Poor Walt gets rougher looking each time we see him, after having his butt kicked at the dance then being in the car crash on the dirt road. With her slow drawl, Ma leads the effort to organize. After that’s done, she goes upstairs and tries to make nice with Lacy, who is sitting stoically in her bedroom. Ma brushes her hair and lets her in on tidbits of the news. Though her brother was killed less than twenty-four hours ago, Lacy’s main concern is Ryan, who she has just met. Ma tells her that she’ll need to testify that the two outsiders killed her brother, and that raises Lacy’s suspicions. Ma then gets angry at her insolence.

With about a half-hour left in the movie, it’s time for the action. Sam has organized fifteen or twenty locals to form a search party, though he doesn’t know that the Ludiggers have already organized part of the group as a lynch mob. He gives them orders to split up and move toward each other, to hem Ryan in. Meanwhile, Ryan is stumbling through the woods with the shotgun he found.

Soon, the posse catches up to Ryan, but he takes momentary shelter in a little cabin. They let the dogs loose on him, but he guns down two of them. That leads the group to open fire on the cabin without mercy. Ryan manages to escape and jump down an embankment, but he’s hanging on by a thread. They’ve found him.

However, Sam and his group have come from the other direction. He arrives just in time to see Ryan get away. But he looks at the Ludiggers and tells them squarely, “I don’t like this. I don’t like this at all.” The sheriff is onto their plan to kill the only witness to their actions.

Ryan, who is cold, wet, and exhausted soon finds Jefferson again. Lucky for the young man, Jefferson is cooking dinner over an open fire and invites him in to eat, after telling him he’s a “pain in the butt.”

Here is where the story shifts. For an hour and ten minutes, Trapper County War has been about Bobby and Ryan (Yankees) versus the Ludiggers (Southerners). Now, over dinner, Ryan goads Jefferson into a monologue about race relations, Vietnam, patriarchy, and white supremacy. Jefferson, we learn, was the son of sharecroppers who joined the Marines and went to Vietnam because he was dissatisfied with watching his black, Southern parents work hard and get nowhere. But he came back home to find that nothing had changed; the Ludiggers still ran everything and still, despite winning medals and honors in the war, called him “boy.” Ryan is humbled slightly by the speech, but uses it to goad Jefferson into fighting on his side— against the Ludiggers.

If Jefferson wasn’t sure before, the next scene will convince him. After a brief glimpse of Ma telling Lacy that her beau will be dead soon, we see Walt and his two pals ease up into Jefferson’s cabin in the dead of night. Jefferson is sitting at the table alone, and Walt tries to feign friendliness, but Jefferson isn’t having it. Walt soon turns back into his normal rude self and threatens Jefferson, telling him that if he doesn’t help, they’ll come after him, too. Jefferson isn’t amused and says loudly, “Ya hear that, Cassidy, they want me to help them find you!” Ryan emerges from behind a curtain, and Jefferson puts a gun to Walt’s neck. The Vietnam vet then tells Walt and his pals to leave. They have incited war, and it’s coming.

For the next few moments, we see the two sides preparing to fight. The local hillbillies are gathering, and Jefferson is training Ryan to fight guerrilla style.

Sam, ever the levelheaded one, dreads what is coming. In his office, he hears Jefferson calling for assistance over a radio channel, but turns it off instead of answering. Sam has been staring at his dead wife’s picture, then, for odd some reason, the love-interest subplot is dredged back up. His waitress girlfriend comes in, asking him to leave town with her, but he doesn’t answer and she leaves. Sam has nothing left to lose.

Back on the mountain, Jefferson and Ryan are ready. Jefferson hands him Bobby’s harmonica, says that he found it, then the redneck brigade arrives in a convoy of old trucks. In the melee that follows, Jefferson and Ryan are hunkered down on a hilltop with the country folks below. Ma brings out a secret weapon— she gets Lacy out of the truck and ties her to a tree where she could easily be hit with a stray bullet. Then Sam arrives from the other direction. He wants to get justice for Bobby and Elmore, but the Ludiggers aren’t going to allow it. When Pa turns his gun on Sam, Sam has no choice and kills him. Now, the group is going after Sam, while Jefferson fires mortars at them from where he is.

Ultimately, the forces of evil are defeated, and unlikely team of Jefferson, Sam, and Ryan emerges victorious. Ryan kills Walt while freeing Lacy. Sam and Jefferson go to apprehend Ma and the few folks who are still around. But Ma won’t go down so easy. She tries to draw her gun, but Lacy grabs Ryan’s semi-automatic pistol and gets justice for her brother. We go out on an aerial view of the carnage, and the credits roll.

The sad fact is: Trapper County War is a weak movie. The website Rotten Tomatoes has it with 2.1 out of 5 stars, and that seems fair and accurate. The acting is questionable, the premise is unoriginal, and the action scenes are straight out of an ’80s TV show— some quasi-karate moves and explosions that cause men to fly/leap through the air.

As a document about the South, the film’s portrayals are built on stereotypes and not a very good interpretation of them. Plenty of Southern stories are based on conflicts when Northern outsiders coming into an insular small-town community, but in this case, it made no sense for two guys from New Jersey to be there. Who would travel that non-interstate route through western North Carolina on their way to California from New Jersey? Moreover, if one family did “own” an entire small Southern town, they’d probably be somewhat more aristocratic than the unshaven, moonshine-swilling Pa Ludigger and his unkempt, bawling wife Ma. Also, tough guy Walt gets beat down every single time he engages anybody. Perhaps the most convincingly Southern aspect of the film was Jefferson’s minute-long speech about returning from war to find the same injustice he left to escape, but that diatribe, which has nothing to do with the main story, doesn’t redeem the movie.

To see more posts, visit the Southern Movies page

March 31, 2021

Six months into “Nobody’s Home”

Though the website has been online a little longer, tomorrow (April 1) marks six months since Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore officially got started. The first half-a-year has been productive, with two reading periods and subsequent batches of works added to the anthology in January and March. During those reading periods, ads on Facebook and New Pages have swirled around the inter-webs, and mailouts to colleges, writing programs, indie bookstores, and newsrooms have offered flyers to hang on bulletin boards. (If people still do that— I don’t know, do they?)

Within the first two batches of published works are twenty-one essays that cover a variety of subjects, from the current effects of the legacy of slavery to wondering out loud who is (or is not) “Southern.” Of course, when I created the project, I knew what kinds of works I envisioned, but also knew that I’d have to wait to see what I would receive. I like being open to new ideas, and editing this anthology suits that side of my personality. If I’d wanted my understanding of Southern beliefs, myths, and narratives to be the final product, I’d have written a work about it. But I didn’t— I chose to edit a compilation of others’ works about it. The twenty-one essays that have been published so far constitute the beginnings of my goal for the project, and there’s more to come as the call for submissions continues until mid-August.

Within the first two batches of published works are twenty-one essays that cover a variety of subjects, from the current effects of the legacy of slavery to wondering out loud who is (or is not) “Southern.” Of course, when I created the project, I knew what kinds of works I envisioned, but also knew that I’d have to wait to see what I would receive. I like being open to new ideas, and editing this anthology suits that side of my personality. If I’d wanted my understanding of Southern beliefs, myths, and narratives to be the final product, I’d have written a work about it. But I didn’t— I chose to edit a compilation of others’ works about it. The twenty-one essays that have been published so far constitute the beginnings of my goal for the project, and there’s more to come as the call for submissions continues until mid-August.

Though the project has been going well overall, my main disappointment is that COVID-19 wrecked my plans to travel and conduct impromptu interviews with people about the myths, beliefs, and narratives that thread through Southern culture. I had envisioned a lively editor’s blog that included lots of real-world conversations – thus the title, “Groundwork” – but the pandemic has been peaking during this six-month period from October 2020 through March 2021. I’m usually a full-speed-ahead kind of project manager, but it would have been unwise and probably fruitless to traipse off in search of people to talk with in-person. Some people might ask, “What about Zoom . . .?” and my reply would be: “Thanks, I’m good.”

The bright side is that there are six more months to go. For the next six weeks or so, until May 15, the current reading period will continue. Some good submissions have already come in, and I’m looking forward to seeing more. Accepted works from that batch will be published in June. There will certainly be more posts in the editor’s blog, too. And, if things continue to look up, some of them might involve having a word with a few folks out on the road.

March 23, 2021

Watching: “Rooted in Peace” (2016)

Like “Out of Print” and some of the other documentaries I’ve written brief posts about, I missed “Rooted in Peace” back in 2016. I rarely go to movie theaters to see things when they’re new, so good ones often slip past me unless I read about them. This one appeared among the choices when I was looking for something about Pete Seeger. I’d never heard of director Greg Reitman, but the film’s description was enticing and the runtime was not too long, so I decided to give it a try.

Reitman’s basic premise is that much of American culture is based on violence and violent attitudes. In the beginning of the movie, he goes to a comic bookstore then a video game convention, looking for works based on the value of peace— and finds that there aren’t any. As he continues looking around, he recognizes that even medicine and hygiene products are portrayed as attacking and killing what would otherwise hurt us. I’d never thought of it that way, but once I did, I realized that he’s right. We do seem to prefer the notion that we fight to preserve domination, rather than trying to understand how to coexist with what’s around us. Where the violent imagery in sports, movies, and video games might be obvious, other imagery is more subtle: we fight weeds in our gardens, our deodorant fights odor, our detergents removes stains . . . It’s all about defeating, killing, and forcing out what we don’t want around us.

As the film’s title says, the director is looking for a life that is “rooted in peace” instead. It’s an interesting idea, albeit a hard one to sell these days. As Reitman puts it, our culture constantly reinforces the idea that a quality life is based on who and what we can defeat, suppress, or even destroy. It’s difficult to see (or take seriously) the products, clubs, media, activities, and memorials that are built on the value of cooperation, symbiosis, and respect, which leads to coexistence.

So, what about coexistence? Some people see that question and think, Oh great, here’s another guy who wants to defund the police and abolish the military . . . That’s not what I’m driving at (though the film does use the example of Costa Rica as a nation where demilitarizing worked). What I’m talking about are personal choices: how to manage the plants in our yards, what games to play and shows to watch in our spare time, what school extracurriculars to participate in, which memorial sites to visit on vacation. What if we chose not to support violent imagery, activities, and methods? Maybe if we handle things that way, instead of regarding everything as a battle to be won . . .

March 15, 2021

Congratulations to the Winners of the Fitzgerald Museum’s Literary Contest: “The Education of a Personage”

Congratulations to this year’s winners and honorable mentions in the F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald Museum’s third annual Literary Contest and to our first-ever winner of the Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald Young Writers Award!

Grades 9 – 10:

Jessica Kim, “This Side, Reimagined”

Grades 9 – 10 Honorable Mentions:

Sarah Mohammed, “Abstain”

Sruti Peddi, “Letters from War”

Grades 11 – 12:

Kaya Dierks, “The Hunted”

Grades 11 – 12 Honorable Mentions:

Brenna McCord, “Blood and Bone”

Tina Huang, “Similarities”

Undergraduate:

Nardien Sadik, “Painfully Silent”

Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald Young Writers Award

Colby Meeks, Lee High School in Huntsville

The theme for 2020 – 2021 was “The Education of a Personage” to honor the centennial of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s debut novel This Side of Paradise. The Fitzgeralds’ literary and artistic works from the 1920s and 1930s are still regarded as groundbreaking, and The Fitzgerald Museum is pleased to honor these young writers as daring and revolutionary writers of their generation. Thank you to Alina Stefanescu for judging the high school entries and to Ashley M. Jones for judging the undergraduate category.

About the two high school winners, judge Alina Stefanescu

This beautiful poem [Kim’s poem “This Side, Reimagined”] speaks directly into the legacy of Fitzgerald’s literature and unfinished buildings. In an intertextual key, the poet converses across time with F. Scott’s novel, creating sparks with each enjambment. In looking at war, the poem revises what man learns from it, turning the usual lesson on its head while placing this in the context of Fitzgerald’s life. Daring and revolutionary in a soft way—in a way that challenges the modality and aggression of war itself– Kim recontextualizes the past in lyric.

In this short piece [Dierks’ story “The Hunted”] about hunting with a father, the narrator sets up a tension about what predation means in the context of heritage—and the writer meets the expectation he sets. A haunting and violent immersion in the socialization of southern masculinity and the tools required to inhabit it. One feels how complex inheritance can be, and what it asks of gender- identifying males with respect to silence about violence. How much the son wants to be significant in the fathers’ eyes, and how there is no reprieve from the crime of wanting to belong, to be loved.

About the undergraduate winner Nardien Sadik, judge Ashley M. Jones had these remarks:

[Sadik’s poem] “Painfully Silent” enthralled me with its authenticity and clear vision of the failures of a colonial sense of belonging that does not always leave room for those, like the poet, who come to America from other places. This poet shows us their truth and the ways in which they matter, even in a world which attempts to discount their efforts at being here in this “land of the free.”

In its three years, the contest, which is open to high school students and college undergraduates, has received submissions from around the United States and overseas. This year’s honorees attend schools and colleges in California, Arizona, and Tennessee. The three grade-level winners will receive a monetary prize, and all honorees will have their works published on the Fitzgerald Museum’s website.

This year was the first year for the Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald Young Writers Award. Montgomery, Alabama native Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald was daring and revolutionary in her life, art, and writing, and award that bears her name seeks to identify and honor Alabama’s high school students who share her talent and spirit.

About winner Colby Meek’s portfolio, judge Josef Wise

All submissions were impressive. One, however, stood out above all the rest. Writing with a voice well beyond the age of the writer, exploring sometimes provocative, but always bold and evocative themes and boldly experimenting with verse and poetic style, tone, and voice, as well as form, C. Meeks’ portfolio submission of original poems deserves the distinction of receiving the inaugural Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald Young Writers Award for high school students in Alabama. Each of the seven poems in this portfolio is unique and in total they display a range of poetic devices and mastery of several forms, as well as being a pleasure to read. This gifted writer has an amazing, distinct, and powerful voice, and I’m glad to have had the opportunity to have heard it expressed in these poems.

For more information about the contest, visit the contest webpage on the Fitzgerald Museum website. Guidelines for next year’s contest will be posted in August 2021.

For information on the winners to past year’s contests, click the year: 2019 • 2020

March 2, 2021

One Whole Year of “level:deepsouth— for Generation X”

Yesterday, level:deepsouth marked its first full year online. I started developing the project early in 2020 and got the site online on March 1. The first submission, “Camp Earl Wallace” by Elena Vale Wahl, was published in the summer. Since then, the anthology has added thirteen long form works, three shorter pieces, four book reviews, and a variety of images.

level:deepsouth is a project that I considered for years before getting off my butt and starting on it. As a writer and editor who grew up in the 1980s and ’90s in Alabama, I had seen no forum or venue or publication dedicated to Generation X in the Deep South. For all of the stuff on the internet – the obviously great, the truly wonderful, the simply terrible, the totally offensive – why was there no hub devoted to this set of experiences?

level:deepsouth is a project that I considered for years before getting off my butt and starting on it. As a writer and editor who grew up in the 1980s and ’90s in Alabama, I had seen no forum or venue or publication dedicated to Generation X in the Deep South. For all of the stuff on the internet – the obviously great, the truly wonderful, the simply terrible, the totally offensive – why was there no hub devoted to this set of experiences?

Sure, there are Southern writers now in their 40s and 50s who are working and publishing – some of them making sure we know how Southern they are – but that’s not what I’m talking about. What I am talking about is an effort to collect and document an eclectic group of experiences that are difficult and confusing and don’t necessarily make sense together. Unlike other Southern-focused publications and websites, level:deepsouth is only concerned with Deep Southern, Generation X experiences from the last three decades of the twentieth century. And I’m not mixing the content with commentaries on obscure old blues records, features about out-of-the-way restaurants, and ads for block-lettered graphic tees. level:deepsouth is about one thing: the formative years of my generation in the region where I grew up. That’s all. Being young in the weird, mixed-up, and constantly changing 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s in the the heart of the old Confederacy, the heart of the Bible Belt, the heart of Dixie.

In addition to the twenty works that are already in the anthology and available to read, the call for submissions remains wide open in year two. There is no deadline to submit, and works will be considered throughout the year. If you grew up in this place and during that time, consider adding your story. There’s no way that the anthology could ever be diverse enough.

February 25, 2021

Presenting at the Monroeville Literary Festival, March 4 – 6

I’m pleased to share that I will be a presenter at the Monroeville Literary Festival this year! The 2021 festival will be virtual, not on-site in Monroeville, and my presentation will be on Thursday, March 4 at 2:00 PM. Information on how to register for the festival can be found at this link. All sessions are free.

This is the festival’s second official year, though it evolved out of the Alabama Writers Symposium, which began in 1998. The location is, of course, the hometown of the late Harper Lee, author of To Kill a Mockingbird. The main event will be children’s author and poet Angela Johnson receiving the Harper Lee Award, which “recognize[s] the lifetime achievement of a writer who was born in Alabama or who spent significant time living and writing in the state.” Two others will also be honored: Allen Wier with the Truman Capote Prize, and Dr. Alan Gribben with the Eugene Current-Garcia Award.

February 16, 2021

Third Reading Period for “Nobody’s Home” Begins Today

Today begins the third reading period for my current project Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore. This reading period will begin on February 16 and end on May 15, with works accepted during that period being published in early summer 2021. Hopefully, you’ll see the project’s ads on New Pages and Facebook.

Today begins the third reading period for my current project Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore. This reading period will begin on February 16 and end on May 15, with works accepted during that period being published in early summer 2021. Hopefully, you’ll see the project’s ads on New Pages and Facebook.

For interested readers and for writers who are considering a submission, the works from the first reading period were published in mid-January and are available to read through the project’s Index. The accepted works from the second reading period will be published in March and will also appear on the Index page.

Nobody’s Home is an online anthology of creative nonfiction works about the prevailing beliefs, myths, and narratives that have driven Southern culture over the last fifty years, in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. The publication is collecting personal essays, memoirs, short articles, opinion pieces, and contemplative works about the ideas, experiences, and assumptions that have shaped life below the old Mason-Dixon Line since 1970.