Foster Dickson's Blog, page 21

March 26, 2022

Reading: “Sky Above, Great Wind” by Kazuaki Tanahashi

Sky Above, Great Wind: The Life and Poetry of Zen Master Ryokan

by Kazuaki Tanahashi

My rating: 5 out of 5 stars

I have liked Ryokan since I first read “First days of spring— the sky” in Stephen Mitchell’s anthology The Enlightened Heart when I was in college in the mid-1990s. So I was glad to get this biography and accompanying poetry collection recently, after more than twenty years of general familiarity. Because Ryokan was not a court poet, eschewed attention and fame, and was so poor as to often not have ink and paper, less is known about him than about other poets. Though, the biographer here, who is a calligrapher, does a good job of bringing the anecdotes and other ephemera into a cohesive narrative that introduces the collection.

I hadn’t known much about Ryokan – the man who wrote one of my favorite poems – in part because there isn’t much to know. Like many brilliant creatives, he had an opportunity at a normal kind of success early in life, but found himself unsuited for it. So, thus, he went into a life of austerity that allowed him the freedom to be himself, to be a Zen fool. Some of the stories are bittersweet, showing a man who starved and froze in a hut on a mountainside but who also accepted those discomforts as part of the life he wanted to lead. The first half of the book reads more like literary criticism than biography, but that nonlinear form, along with a substantial array of poems in the latter half, does a good job in bringing the poet to life.

March 15, 2022

Congratulations to the Winners of the Fitzgerald Museum’s Literary Contest: “The Radiant Hour”

Congratulations to this year’s winners and honorable mentions in the F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald Museum’s fourth annual Literary Contest and to our second winner of the Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald Young Writers Award!

Grades 9 – 10:

Arim Lee, “Inheritance”

Grades 9 – 10 Honorable Mention:

Natalie Jiang, “feeling lost in the crowd”

Grades 11 – 12:

Avery Gendler, “A Playlist, or a Sonnet Crown”

Grades 11 – 12 Honorable Mention:

Samantha Hsiung, “chinatown pt. 2”

Undergraduate:

Ria Dhingra, “A Modern-Day Manual to the Midwest”

Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald Young Writers Award

Kathleen Doyle, LAMP High School in Montgomery

The theme for 2021 – 2022 was “The Radiant Hour” to honor the centennial of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel The Beautiful and the Damned. The Fitzgeralds’ literary and artistic works from the 1920s and 1930s are still regarded as groundbreaking, and The Fitzgerald Museum is pleased to honor these young writers as daring and revolutionary writers of their generation. Thank you to Jason McCall for judging the high school entries and to Pat Reeves for judging the undergraduate category.

About the two high school winners, judge Jason McCall had these remarks:

Lee’s “Inheritance” presents the definition of the word as only poetry can. This haunting poem grips readers with movement, imagery, and cutting diction to show how the beauty and weight of family and tradition live on in the body, mind, and spirit.

Gendler’s “A Playlist, or a Sonnet Crown” shows how even the most traditional forms can be revived and made fresh by the mind of a modern writer. Part formal masterclass in formalism, part masterclass in narrative, the poem shines a brilliant light on how moments and emotions can be immortalized in verse.

About the undergraduate winner Ria Dhingra, judge Pat Reeves had these remarks:

“A Modern-Day Manual to the Midwest” by Ria Dhingra seems initially to take the form of advice given to a newcomer to the Midwestern United States, but eventually pivots toward a personal meditation. [ . . .] The beauty of this piece is not in any single line, but in the accumulation of images, the vignettes that make up a typical day, that move us into adulthood, and finally, that weave into a whole that is a life. The rhythm and cadence of the short sentences begins to have a dreamlike effect that, even when the images are jolting, echoes the boredom of the day-to-day.

In its four years, the contest, which is open to high school students and college undergraduates, has received submissions from around the United States and overseas. This year’s honorees attend schools and colleges in Massachusetts, Michigan, California, and Wisconsin. The three grade-level winners will receive a monetary prize, and all honorees will have their works published on the Fitzgerald Museum’s website.

This year was the second year for the Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald Young Writers Award. Montgomery, Alabama native Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald was daring and revolutionary in her life, art, and writing, and award that bears her name seeks to identify and honor Alabama’s high school students who share her talent and spirit.

About winner Kathleen Doyle’s portfolio, judge Kerry Madden-Lunsford said:

From her moving and funny piece “Lonesome George” about Pinta tortoise on a trip to Galapagos with her frail grandfather to her literary narratives on the work of Hemingway and Gatsby to the modern gothic world of the aptly-named “Renfroe’s Foodland,” (I kept thinking of Renfield running the grocery store somewhere in the Deep South) to her sparkling Yelp reviews, Kathleen shows her range as a writer of creative nonfiction with a keen eye for detail and a wonderful sense of humor and timing. She has a tremendous ability to paint a world with her words with her bright cinematic descriptions and deep empathy for her subjects, and I found myself wanting to linger in the places she created.

For more information about the contest, visit the contest webpage on the Fitzgerald Museum website. Guidelines for next year’s contest will be posted in August 2022.

For information on the winners of past year’s contests, click the year:

2019 • 2020 • 2021

March 10, 2022

Local Events for National Poetry Month, April 2022

Though COVID put a damper on that last two years’ events — in April 2020 and April 2021 — the Four Mondays of Poetry program will return (in slightly modified form) for National Poetry Month. This longstanding collaboration between the high school Creative Writing program that I teach and the English department at Auburn University at Montgomery has typically featured a poetry workshop, a local poets reading, an open mic event, and a featured poet. Past years have seen AUM bring Frank X Walker, Denise Duhamel, Neil Carpathios, Jacqueline Trimble, and others. This year, the program will proceed without a featured poet, effectively becoming Three Mondays of Poetry. Below is the schedule of events with brief descriptions:

April 4: poetry workshop at Auburn University at MontgomeryAnyone in the Montgomery area is free to submit a poem for the workshop, led by AUM Creative Writing professor Kent Quaney. Please email your poem (before March 20) to kquaney@aum.edu. The workshop will be held in the Liberal Arts building on the AUM campus, room TBA.

April 11: Local Poets at Kress on Dexter(hosted by BTW Magnet Creative Writing)

The reading will begin at 7:00 PM and end at 8:30. It will feature Susie Paul, Jacqueline Trimble, and Jonathon Peterson (JP da Poet). The reading is free and open to the public.

April 18: High School Open Mic at LAMP High SchoolThis event will begin at 4:00 PM and end at 5:30. Any Montgomery area high school students may come read poetry or just come to listen.

March 3, 2022

“level:deepsouth” turns two.

level:deepsouth is a crowdsourced online anthology about growing up Generation X in the Deep South during the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s. The anthology is open to submissions of creative nonfiction (essays, memoirs, and reviews) and images (photos and flyers), as well as to contributions for the lists.

level:deepsouth is a crowdsourced online anthology about growing up Generation X in the Deep South during the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s. The anthology is open to submissions of creative nonfiction (essays, memoirs, and reviews) and images (photos and flyers), as well as to contributions for the lists.It was two years ago this week that level:deepsouth went online. I had had the idea for a while before that, since there was no publication, no project, no website – none that I could find – devoted solely to Generation X in the Deep South. I had pondered first whether such a project could be a newspaper or magazine, whether it should be a book, then I gave in to the reality that, even though we were raised on print, this is now an internet world. And while I am an editor, this subject is larger than a single print anthology or similar compilation.

level:deepsouth is devoted to collecting, archiving, and sharing stories, images, videos, texts, and links that speak to what it was like growing up in the Deep South in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s. You can read my editor’s introduction “Definitions, Numbers, An Exodus, and the Stories” for a better idea on what that means more specifically, but I’ll add this. In the 2000s, I worked on quite a few projects that collected the stories and images from the Civil Rights movement. By that time, most movement veterans were elderly or close to it – having been born in the 1940s or earlier – and there were obvious challenges associated with talking with them at that late date: foggy memories, re-interpretations over time, forgotten names, lost photographs. Often, in response to a question, we would hear, “You know, that was a long time ago . . .” which was then followed by a shaky recollection. Those experiences lead me to devise the idea for level:deepsouth. In the 2010s, GenXers were in our 30s and 40s, a prime age range for remembering and retelling stories from the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. Perhaps, I waited too long to begin, but let’s be honest: we’re not exactly “old” . . . yet.

Probably the most important thing to include here is that level:deepsouth remains open for submissions. The project has published some stories from Generation X, but there are a lot more out there. I have continued to track down sources for “the lists” and to write up scattered information for “tidbits, fragments, and ephemera,” but what will bring the project to life are the stories. To truly represent our generation in this place at that time will require more firsthand recollections. For those who aren’t confident in their writing ability, I am offering my editorial help. Finally, I’m aware that the lack of an author payment leads some writers to decline the opportunity, but as long as I’m funding the project with my own money, they’ll just have to miss out. (If anyone is confused by the lack of payment, please read this.)

We’ll see what the next year holds. No matter— if you grew up in Generation X in the Deep South, consider adding your voice to this fledgling cacophony. I’ll be here for a while longer to impose some order on that chaos.

February 22, 2022

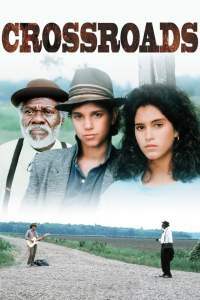

Southern Movie 57: “Crossroads” (1986)

Fresh off his success in 1984’s The Karate Kid, Ralph Macchio played a young guitarist named Eugene Martone in the 1980s blues-themed movie Crossroads. Martone studies at New York’s Julliard School but his love for the blues supersedes his interest in classical studies. That focus leads him to track down Willie Brown, the last man alive who might know Robert Johnson’s “lost song.” (Those familiar with blues history will know about Johnson’s recordings in 1936 and ’37, but let’s be honest: this movie wasn’t made for the blues crowd.) Directed by Walter Hill, who also directed 1981’s Southern Comfort, this film is very ’80s and somewhat similar to Karate Kid, playing heavily on a young underdog’s unlikely success that comes in part from lessons taught by an older mentor.

Crossroads opens in sepia tones as we see a black man in a suit carrying an acoustic guitar. He walks along a gravelly dirt road toward an intersection by an old dead tree. A blues piano plays in the background as the man looks down one road then down another. Next, we see him notice someone who has apparently arrived without warning, and he regards the person, who we don’t see, skeptically. We understand that this is Robert Johnson’s infamous experience at the crossroads, the deal made famous by the song.

Next, we see the same man walking the narrow halls of what looks like a hotel. He knocks on a door, a white man opens it without a word, and after removing his hat, Johnson sits down to record “Crossroad Blues.” With that basis laid, the song segues into Eugene’s dorm room in modern times. The walls are covered in blues imagery, and the tables are littered with records and magazines. The young student has his beat-up acoustic and is trying to play along with a cassette-tape recording.

We learn soon that Eugene is more than a boy who likes music when we see him scrolling through microfilm of old newspapers, reading about Willie Brown, whose name appears in the song. His studious expression tells that he has found something, then we see him crossing the street to a prison-nursing home in the city. Inside, he has a pass to come in, shows it to a gruff orderly, then proceeds to the nurse’s station where he announces that he is there to see Willie Brown (Joe Seneca). The nurse goes down the hall into a room and returns quickly, telling Eugene that Willie doesn’t know him. Eugene’s insistence and his attempts to explain himself only illicit the retort that Willie doesn’t want to see anyone at all.

Dejected, Eugene starts to leave but on his way out sees a sign announcing a janitorial job that needs to be filled. When the scene shifts to Eugene wearing coveralls and mopping the hall, we know he has found his in-road. A woman waddles by and tells him to empty her trash can, but he just keeps mopping, eventually finding his way into Willie Brown’s room. Willie is sitting in a wheelchair and playing his harmonica. He stops and asks, “What you want, Mr. Janitor Man? I ain’t made no mess.” Eugene comes in, trying to be friendly, but he has an agenda, which he quickly reveals. Spouting tidbits of blues history that he has read in books, Willie has an indignant answer for every aspect. Eugene pushes hard: he must be the Willie Brown from the song, he must be the man whose alias was Blind Dog Fulton. Willie brushes him off then shuts him down, but we see from Willie’s expression after Eugene leaves that there must be something to Eugene’s notion.

In the next series of scenes, we get to see Eugene’s dilemma a bit better. First, he is in a classroom with a group of students and plays his classical piece for a teacher who is evaluating him. At the end of his classical piece, he adds a little blues turnaround and is told by his instructor that the flourish was disrespectful. Back at the nursing home, he runs into Willie again, and the elder man asks why he was asking those questions. Eugene tells him that he is looking for Robert Johnson’s lost song, because he is a bluesman. Willie laughs out loud and mocks him until a nurse comes to roll him away. Back at Julliard, Eugene is then in his professor’s office, where he is being told that his devotion to non-classical music is hampering his development in classical studies. Eugene wants to know whether he can do both. The professor tells him no. This, we now know, is not so much a story about the blues but about a young man whose inner struggle revolves around what he is versus what he wants to be.

When Eugene sees Willie again, the old timer is drawing a picture of the crossroads with crayons. Eugene comes in to empty the trash, and Willie mocks hims some more without really looking up. Eugene’s consternation is obvious, and he asks Willie one more time whether he’s Blind Dog Fulton. Nope is the reply. So Eugene pulls his trump card: a photograph of a much younger Willie Brown, standing among a group of musicians at a bar— same round face, same glasses, same smile.

This item leads Willie to smile and then flashback to the time when he made his deal with the Devil at the crossroads. Unlike the movie’s opening scene, this time we see a befuddled-looking young man in overalls (not a suit) who is approached by a man in a car. The smooth-talking, arrogant driver gives the young Willie a contract, which he signs with his mouth hanging open. Where Robert Johnson seemed like he knew what he was doing, young Willie does not.

Once we’re back in the present day, we do not return to that particular scene of Willie being confronted, but later. Eugene storms into the break room with his guitar, plays a few licks, then follows Willie down the hall proclaiming that he plays just like Son House. Willie is not impressed, knowing that the blues is about more than technique. Eugene also makes the absurd suggestions that Willie could teach him the song and that they could record it in the hospital. But now, twenty minutes in, we are about to the see the crux, that moment when Eugene must make a choice. Willie stops his wheelchair and whispers, “Get me outta here.” Willie, who has nothing to lose, proposes a bargain: break him out and get him back to Mississippi, and he will teach Eugene the song. However, Eugene is flabbergasted and says to the old man, who is incarcerated, “What’re you trying to do, get me arrested?” In Willie’s room, the two argue a bit, and Willie reveals that he can walk and that he has this plan. With a stashed money roll and Eugene’s help, he can get out of that inner-city hospital and back to his home down South. The change comes when a grimacing Eugene reluctantly agrees. Be ready at 5:00 AM tomorrow, he tells Willie.

The next morning, Eugene sneaks quietly into the nursing home and finds Willie dressed in a suit and carrying a suitcase— not exactly low-key sneaking out clothes. On their way out, that gruff orderly from earlier in the movie chases them, but Eugene manages to lock the door and get Willie to a waiting cab. The two fugitives arrive at the bus station, and Eugene asks for the money roll that Willie showed him the night before. Willie refuses, saying that it’s unwise to pull money out in public. Go get us tickets to Memphis, he says, and I’ll pick it up from there. At this point, Eugene has two good reasons to be wary: Willie claims to know the song but won’t share it and claims to have money but won’t use it. (What follows the bus station scene, unfortunately, doesn’t make much sense. They’ve broken out at 5:00 AM, went straight to the bus station, but are leaving town at night. For that to be right, the escaped inmate and his helper would have had to sit in the bus station all day long, until the sun went down . . . Wouldn’t they have gotten caught?)

On the bus heading south, Eugene and Willie talk in the dark. Eugene shares his book learning, and Willie tells him what really happened. He was there for everything and had made a deal with the Devil. Now, it is nearing time to pay up, and all he could do is sit in an “old folks’ cage” after shooting a fellow musician who double-crossed him over money.

In Memphis, the two unload with the intention of changing buses. Eugene asks for the money, but Willie is slow to give it . . . until Eugene insists. It turns out that money roll was only two $20 bills wrapped around newspaper clippings. They won’t be able to get any bus tickets with that little money. Eugene is learning the hard way about life on the road. Willie informs him that they’ll be walking the rest of the way. In trying to use an old man, Eugene finds out that he has been used himself. “Welcome to Bluesville, son,” Willie tells him.

Next we see the pair, they’re hanging their feet off the back of an old pickup full of chickens. They get dropped off right in front of a Highway 61 sign, and Willie changes his necktie. Meanwhile, Eugene is pouting about their circumstances. As they walk on up a two-lane road, a train comes. Willie smiles and pulls out his harmonica to play like the train. Eugene tries to mimic it on the guitar, behaving as though he’s never heard of such. Strange that a young man who has read so much blues history seems not to know about something to elemental as “making the train talk.” Because he’s a greenhorn, though, he disappoints Willie when he tries. In an effort to fend off the criticism then, Eugene makes a smart remarks about how he’ll just make a deal with the Devil, and Willie slaps him across the face.

Later that day, in a little store, the tension is palpable. Willie is frustrated with Eugene, and Eugene is fed up with what he has gotten himself into. The boy only wanted a song and to be famous for playing it. What he got was an immersive experience in what he’d been reading about. Willie finally lets out that he has his own reasons for being down in Mississippi, which are none of Eugene’s business. He also tells the novice that he’s a fool for playing on a squeaky old acoustic guitar, trying to mimic his heroes. “Muddy Waters invented ‘lectricity,” he says.

Which carries them into the pawn shop, where Eugene is looking at a Telecaster. Two things don’t make sense here: where they got money, since they couldn’t afford two bus tickets, and why a black man’s pawn shop has so much Confederate symbolism in it— but okay, we’ll go with it. The older black man behind the counter talks up the guitar and a portable Pig Nose amp to go with it. Eugene likes the new set up, so Willie takes the man aside to speak with him about the price. Offering Eugene’s watch and Lord knows what else, he gets Eugene electrified.

Which carries them into the pawn shop, where Eugene is looking at a Telecaster. Two things don’t make sense here: where they got money, since they couldn’t afford two bus tickets, and why a black man’s pawn shop has so much Confederate symbolism in it— but okay, we’ll go with it. The older black man behind the counter talks up the guitar and a portable Pig Nose amp to go with it. Eugene likes the new set up, so Willie takes the man aside to speak with him about the price. Offering Eugene’s watch and Lord knows what else, he gets Eugene electrified.

Nearing the halfway point in the story, Willie and Eugene are running down a dirt road in the pouring rain and find an abandoned house where they take shelter. Inside is a pretty young white girl changing clothes. She pulls a knife on them, telling them to leave, but Willie takes the knife from her. Some tense getting-to-know-you ensues, and we learn that the girl – Frances (Jami Gertz) – is a runaway heading to LA to take a “dancing gig.” Willie tries to mythologize their own roots, saying that Eugene broke him out of prison, but Eugene ruins it by clarifying that it was a nursing home. Frances is brash and streetwise and wants nothing to do with our heroes. But Willie has different ideas, since her pretty face is going to attract more rides than Eugene’s thumb.

Frances’ attractiveness does draw them a ride on that muddy dirt road, and they arrive at a small-town bar that has a motel across the parking lot. Willie and Eugene play to a small crowd outside, but they get run off when the shady owner arrives in his convertible Cadillac. The two musicians then go hide behind a dumpster with their tips and see Frances going into one of the motel rooms with shady Cadillac man. Inside, the proprietor explains that he’ll be getting one for free, to test her out, and then she’ll be able to sell herself out of the room all night long. He goes into the shower then, and she begins to undress when Willie and Eugene come to the rescue. They urge her to leave with them, and with a pistol that Willie produces out of nowhere, they rob the shady redneck pimp of his money and the keys to his car. Eugene is very disturbed by the gun, and Willie shares that he bought it at the pawn shop.

Now, our duo is a trio. Despite the fact that they are regularly committing felonies, we’re pulling for them. After the robbery, they’re riding in style, at least until they go to a junkyard and sell the Cadillac. Back on foot again, they make their way into a barn to stay the night— a particularly unwise move since they cross a freshly plowed field to get there. But this nighttime scene allows for another complication in the plot when Eugene and Frances go up into the hayloft together.

Our heroes are woken up by flashlights, and local sheriff’s deputies show up to expurgate the trespassers. Unlike the common trope that almost always has Southern deputies to be white and corrupt, the deputies this time are black— but equally corrupt. While arresting Willie, Eugene, and Frances, one of them takes the money out of Frances’ bag. The daylight then finds them waiting by a bridge, in the back seat of the deputies’ car, when the sheriff, who is also black, arrives. He informs them that he’s in a good mood and will let them go. They can cross the bridge and be in another county, where they won’t be his problem anymore. But Frances objects and wants her money back. The deputy who took it remains silent when accused, and the sheriff then tells her that he can help her out: he can put her in the county farm while she presses charges and waits on the deputy’s court date. Willie sees the wisdom in moving on, making a cutting remark about corruption as they begin to walk.

After another narrow escape, they arrive at a small hotel and book a couple rooms. Willie asks the older black woman behind the desk whether she’s seen the crossroads in his crayon drawing. She says no, but tells that the town of Weaver (or maybe Weevil) is about two miles down the road. Willie knows the town, which turns out to be very small with a dirt Main Street. Of course, there is a white barroom on one side and a black juke joint directly across. This scene is one of few in the film that ties itself directly to race. Outside in the streets, Willie gives them instructions to go into the white barroom and “bring home the big eagle.” Grifter that she is, Frances knows what to do, but Eugene is hesitant, so Willie gives him the gun for protection. Here, at about the two-thirds mark in the movie, Eugene finally calls bullshit on Willie, reminding him that everywhere they go, no one has ever heard of Fulton’s Point, Willie’s supposed homeplace. Willie bites his lip but sends them on, remarking to Frances they should stay on their side of the road.

Inside the crowded barroom, Frances stalks the room while Eugene hangs back. A messy-looking middle-aged man in a plaid sports coat quickly picks up on her, asking her to dance. Frances obliges with a smile, but in a moment, he realizes that she has stolen his wallet. Called out in front of everyone and knowing that she is guilty of the theft, she has no choice but to shout that her friend has a gun. Eugene is in deeper than he should be and shows off the pistol, clearly knowing that he won’t use it. To resolve the situation, the old surly bartender then brandishes a shotgun, orders Eugene to relinquish the pistol, which he does, then tells them to get out— and to grow up. With no other choices, they leave and go into the black juke joint across the street. Big mistake. The whole place stops, and everyone moves toward them. Eugene and Frances are confronted by black people wanting to know why they’ve come in there. They just want to find their friend Willie, that’s all. And out of nowhere, a harmonica breaks the near silence— it’s Willie, saving the day, calling the crowd to let them through to the stage. However, once Eugene gets to the stage, Willie pulls him aside, calls him a “dumb shit,” and threatens that he’d better play good or they’re all in trouble. Of course, they do, and the whole place erupts.

Back at the hotel, Eugene feels like he has finally made it. He has survived some hardship and played blues in a juke joint. But a drunk Willie won’t let him fly high. An argument ensues between the two, with Frances taking Eugene’s side. Willie returns to his room, with nothing resolved, and has a dream about his deal with the Devil. Lest we forget, in paying attention to Eugene’s journey, that Willie is on a journey, too.

In the morning, Frances packs up her suitcase and leaves Eugene without saying goodbye. Willie is awake, though, and speaks to her before she leaves. Frances has no interest in following them around, she has her own dreams to chase, and Willie gives her a few bucks for the road. Last we see Frances, she is walking up a rural highway at sunrise.

When Eugene wakes up and finds that Frances is gone, that’s not the only problem he has to face. After learning that she snuck out on him, Eugene walks out in the rain and stares off in the distance sadly. Returning inside, Willie knows his pain and, during their talk about the blues, lets out the truth: there is no lost song. Willie lied to Eugene to get out of that nursing home. A stunned Eugene walks over, picks up his guitar, and starts to play, while Willie ruminates out loud. Eugene has now learned what it means to play the blues.

With Crossroads winding down, almost everything has been addressed . . . except Willie’s deal. In town, they pull up in a cab at a house, where Willie asks for a woman who has not been mentioned so far. The young black woman at the door tells her that she’s dead. This was a house of prostitution long ago, but it’s just a quiet home now. He asks the young woman about his crayon crossroads. That’s where they have to go.

At the crossroads, Eugene is skeptical that any such magic will happen, but soon a sports car races toward them, and the same brash man from Willie’s sepia-toned deal gets out. He has not changed nor aged. Willie wants to see Legba, but the wily man says that he goes by Scratch now. A surlier-than-ever Willie says to stop playing games, he needs to see him. And suddenly the Devil appears. He is wearing an old-style black suit and hat, and has a broad smile. He is friendly to Willie, but Willie is all business. Both men ignore Eugene, who is baffled. The deal is off, proclaims Willie, but the Devil responds that it doesn’t work that way. Willie tries to offer him money, to no avail, and the Devil suggests coyly that Eugene’s soul might make him change his mind. Willie says no, but Eugene laughs it off, saying, “I don’t believe in any of this shit anyway.”

What must happen is: Eugene will “cut heads” with the Devil’s man named Jack Butler, played by ’80s guitar hero Steve Vai. If Butler wins, then both Willie and Eugene are under contract. If Eugene wins, then Willie is free. Magically, they are all transported to a big juke joint, and there on the stage is the man Eugene must outplay. He is long-haired and wearing spandex, a stark contrast to Eugene’s humbler clothes. The duel begins, with Butler’s crazy antics and wild solos, and Eugene responds with his old school blues. After a short back-and forth, it appears that Jack Butler will win. The crowd cheers, the Devil laughs, and Willie hangs his head. Until Eugene breaks in with his classical music, flying up and down the guitar’s neck as everyone slowly realizes that he is not defeated after all. When he is done, Jack Butler can’t respond, the wild man can’t play the carefully measured music. Finally, our underdog comes out on top by relying on the very thing he thought he wanted to discard. Willie’s contract gets torn up, and Eugene has gained the experience he wanted.

Back on the road, Eugene is rambling about their new musical partnership and his plans, but Willie tells him that they must part ways. We already understood that they were at different points in their lives, and soon – though we won’t be there to see it – their paths must diverge. The end.

Crossroads leaves the viewer with some very reasonable questions to ask. Any person would wonder: after Eugene defeats the evil guitar player, what will happen next? Certainly, Willie was reported as an escapee and Eugene as his accomplice, and when the two emerge with their music, the law will easily swoop in. Put simply, Willie might not be going to hell, but Eugene is going to jail, where he will learn some real blues. At least in The Karate Kid, we could see Daniel going back to high school on Monday and enjoying his triumph. Here, that’s not the case.

Back in 1986, the late Roger Ebert saw this movie a lot like I do now:

It borrows, obviously, from Macchio’s movie, “The Karate Kid” (1984), which also was the story of a young man’s apprenticeship with an older master. It also borrows from the countless movies in which everything depends on who wins the big fight, match, game or duel in the last scene.

But the question for me, ultimately, is: what does it say about the South?

Crossroads is built on a common, generally white half-understanding of the blues, but it helps itself slightly by having Eugene “Lightning Boy” Martone to be the embodiment of that very person. If all a white person in the 1980s knew about the blues was Robert Johnson, slide and harmonica, Mississippi, and Highway 61, this movie would be very digestible. And at the same time, it would show that person to himself, as he watched Eugene try too hard, rely on trite symbolism, and make claims he shouldn’t be making as he sets about committing serious acts of cultural appropriation. After all, Eugene wants the lost song to make himself famous, and arrogantly expects Willie to share it with him for that reason. My personal favorite part of Eugene’s comeuppance comes in the pawn shop when Eugene dons a pork pie hat and says, “Look, Willie, I’m a bluesman,” to which Willie replies, “Yeah, you need a lot more than that hat.” Our protagonist is the case study in the kid who thinks that, if he wears the clothes and plays the tunes, then he must be the real thing. Uh . . . no.

Thankfully, the other character we see throughout the film is Willie Brown, played by Joe Seneca. This character speaks for the South and for the blues, and he does it regularly and with authority, correcting Eugene whenever he gets the chance. What is interesting is that this Willie Brown makes little mention of race, reinforcing my idea that this film was made to be easily digestible for 1980s white people. There are inferences to be made from his actions, like when he admonishes the young white couple not to come on the black side of the road and into the black club. He often scolds Eugene for being naive and childish, but less often for being white and arrogant.

If I had to guess, the idea for Crossroads probably sprung from a mainstream interest in the blues in the 1980s. After the heyday of blues-rock in the 1970s, Eric Clapton and a few others like him had dropped the heaviness of rock music (as in Cream’s 1968 version of “Crossroads”) and followed a somewhat more purist path. As a teenager, I remember the compilation tapes, like the ones Eugene listens to, being cheap and often sold at gas stations. By the 1980s, there was a better understanding of how badly black blues musicians had been exploited, and many of the great mid-century folks were elderly or dying. (Muddy Waters died in 1983.) I would assume that feelings of guilt and a twinge of nostalgia each played a part in creating the film. But if we wanted mainstream Americans to understand the blues, what it was, what it involved, this movie – about a white kid who wants to exploit an old bluesman – wasn’t the way to achieve that. The way I see it: the movie Crossroads is about living the blues in the same way that the TV show Full House was about living in a nontraditional family.

February 6, 2022

Southern Movie Bonus: Another Black History Month Sampler

In February, we take time to celebrate and recognize the contributions and achievements of African Americans. So, in honor of Black History Month, the Southern movies listed below are either about African Americans in the South or come from African-American culture in the South. From more recent years, moviegoers may be familiar with 2012’s The Help or 2013’s Selma, but here are eight Southern movies that may be less familiar to modern audiences.

Murder in Mississippi (1965)Released the year after the 1964 murders of Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner, the film follows a carload of Civil Rights workers who head south to help with voter registration. In the beginning, the interracial group is optimistic but the events and circumstances they face quickly sour that. While the movie is low-budget and at times dogmatic, its candor about the violence and cruelty of white supremacy is remarkable, considering the time in which it was made. Particularly interesting is its open recognition that white Civil Rights workers were not facing the same situation as black Civil Rights workers.

One notable face from the film is D’Urville Martin, who played the angry beatnik at the ice cream stand in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner and later was Willie Green in Dolemite. In this film, he is listed in this movie as Martin St. John, but film buffs won’t mistake that face and voice.

The Black Klansman (1966)More than fifty years before Spike Lee made his film of almost the same name, this stark, low-budget film used “passing” to tell the story of a black man who infiltrates the Ku Klux Klan. It brought viewers, who were in the midst of the Civil Rights era, the Deep Southern story of a light-skinned “negro” in Los Angeles who infiltrates the Ku Klux Klan in his old hometown of Turnerville, Alabama after they kill his young daughter in the fire-bombing of a church. The opening credits explain that the screenplay is based on a song of the same name by Terry Harris. Though it’s probably too early to be considered “blaxploitation,” this one from the mid-1960s does have some of those characteristics.

tick . . . tick . . . tick . . . (1970)This film tells the story of a small Southern town whose long-time white sheriff has been voted out of the office by newly enfranchised blacks. The new sheriff is a cool-and-collected family man played by football great Jim Brown. Of course, the white townspeople are not fond of their new black sheriff, but neither are the few militant blacks, who want this new empowerment to mean a reversal of the power structures. Jim Brown’s righteous character Jimmy Price is determined to have law and order prevail— but he is caught in the middle. Though we never get to know exactly where they are in the South, one bit of dialogue implies that their small town lies somewhere between Atlanta and Birmingham.

While taking on the well-known racial issues of the day, this film throws in a few of the supporting characters that we expect: an omnipresent Ku Klux Klan looming near every precarious scene, a troublemaking bigot from a notoriously shiftless family, and a self-important local bigwig. It’s all there. We even get a mass-violence scene full of lawless mayhem near the end.

Quadroon (1972)With a title based on an old racial distinction, this early ’70s movie deals with the plight of biracial women in Creole society in Louisiana. We find our way to the story, which is set in the 1840s, through a white Northerner who comes to stay with relatives down South. He encounters the ugliness of slavery and those who make their living from it, but in seeking employment as a teacher, meets a beautiful young woman and falls in love. The problem is: they can’t be together.

Though it has a point in presenting the moral quagmire that was the pre-Civil War South, the film’s plot moves slowly, and its main character is white. However, the bulk of its message revolves around the difficult lives of biracial women who were limited by and exploited within rigid social strata.

JD’s Revenge (1976)This one has a supernatural premise: a gangster murdered in New Orleans in the 1940s comes back to get revenge using the body of a law student. The main character Ike (Glynn Turman from Cooley High) begins behaving uncharacteristically once he is inhabited by the spirit of JD Walker, who wants to kill his killer Theotis. The film’s other star Louis Gossett, Jr. was primarily a TV actor during this time, and a few years shy of his big-screen successes in the ’80s (in An Officer and a Gentleman then Iron Eagle).

A Gathering of Old Men (1987) and A Lesson Before Dying (1999)Ernest J. Gaines, who died in 2019, was an incredibly good storyteller whose works capture the complexity of Southern life, but he was also one whose works did not always make good adaptations. Of course, he wrote the novel that became the well-known 1974 movie The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman, which did well. Unfortunately, A Gathering of Old Men was turned into a made-for-TV movie in 1987, and did not do so well. While that latter film is true to the novel’s story, the screenplay gives away the ending at the very beginning, which removes much of the novel’s tension. Here again, we have Louis Gossett, Jr. who plays Mathu, the man at the center of the plot. Finally, Gaines’ novel A Lesson Before Dying was also made into a TV movie in 1999, with Don Cheadle and Mekhi Phifer playing the main roles. This last film won several Emmys as well as other awards.

Rosewood (1997)The Rosewood Massacre occurred in January 1923, following a period of severe racial violence in late 1922. The tiny rural community of Rosewood is located on Florida’s Gulf Coast about halfway between Tallahassee and Tampa. This film dramatizes the historical events. It stars Ving Rhames and was directed by John Singleton, who made 1991’s Boys N the Hood.

To see last year’s Black History Month Sampler, click here.January 22, 2022

Follow.

January 6, 2022

Reading: “The Return of the Prodigal Son” by Henri Nouwen

The Return of the Prodigal Son by Henri JM Nouwen

The Return of the Prodigal Son by Henri JM Nouwen

My rating: 5 out of 5 stars

It’s a story that most people know, at least partially. In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus tells the Pharisees about a young man who gets his inheritance in advance, leaves home, and squanders it, then comes home starving and desperate to his happy, forgiving father and bitter, resentful brother. Henri JM Nouwen’s short book, published in 1994, explores this Christian parable using the 1669 painting of the scene by Dutch master Rembrandt van Rijn as a framework.

Nouwen writes about the painting as a catalyst for a spiritual journey. He took a special interest in the artwork when he saw a print of it in someone’s office, then later got to see the painting itself in St. Petersburg, Russia. Thus, his book has three parts – the prodigal son, the resentful brother, and the forgiving father – which are framed by a narrative about his personal experiences with Rembrandt’s representation. Throughout his discussions, Nouwen reminds his reader that we aren’t necessarily going to be one or the other of the two sons. On some occasions, we are more like the wasteful younger son who is open to redemption; at other times, we are more like his bitter older brother who has not strayed but remains closed. But no matter which, the forgiving father who wants his children to be happy and cared for will always be there, offering a joyful home no matter what.

One nice thing about this little book is how accessible it is. It could be tempting to assume that a highly educated Catholic priest discussing a Biblical parable in the context of a Renaissance-era painting might require a lot from readers, but Nouwen doesn’t. The style and the message are clear and easy to follow. The length is also very manageable at about 150 pages.

In my own reading, one passage stood out particularly: “Real loneliness comes when we have lost all sense of having things in common.” Nouwen had been writing in this first section on the younger son about how we often let the world define and forge our own sense of worth. This sense of deserving to belong or earning admiration then creates a sense that it can also be lost. However, God’s love – like father’s in the parable – isn’t like that at all. He simply wants us to be home, with Him, and a part of the joy that He offers. There’s no deserving or earning it, so each one of us always something in common with others— call it the human condition, maybe. And though this book was published twenty-seven year ago, it was a welcome reminder about our interconnectedness as we continue to traverse the COVID-19 pandemic, which has involved periods of separation, quarantine, isolation, and dissociation from each other.

December 28, 2021

A Deep Southern, Diversified & Re-Imagined Recap of 2021

2021 was one of the worst and best years of my adult life. Worst— because of the pandemic. The 2020 – 2021 school year was a wild ride (and not in a good way). Sometimes weeks-long quarantines affected my mental health, and I was totally dismayed at how athletics got to proceed while other aspects of life, like the arts, had to shut down. But best— for an array of reasons. Despite the challenges of virtual learning, my students and I published Sketches of Newtown in the spring. And despite being frazzled, I continued to work on projects (Nobody’s Home, level:deepsouth, the Fitzgerald Museum’s Literary Contest, and the Montgomery Catholic history book) that I care about very much. Perhaps most importantly, everyone in my family followed public health recommendations, got vaccinated as soon as we were eligible, and made it through two peaks of the pandemic without serious illness. Below is a recap of what I’ve been up to this year:

2021 was one of the worst and best years of my adult life. Worst— because of the pandemic. The 2020 – 2021 school year was a wild ride (and not in a good way). Sometimes weeks-long quarantines affected my mental health, and I was totally dismayed at how athletics got to proceed while other aspects of life, like the arts, had to shut down. But best— for an array of reasons. Despite the challenges of virtual learning, my students and I published Sketches of Newtown in the spring. And despite being frazzled, I continued to work on projects (Nobody’s Home, level:deepsouth, the Fitzgerald Museum’s Literary Contest, and the Montgomery Catholic history book) that I care about very much. Perhaps most importantly, everyone in my family followed public health recommendations, got vaccinated as soon as we were eligible, and made it through two peaks of the pandemic without serious illness. Below is a recap of what I’ve been up to this year:

Presenting at the Monroeville Literary Festival, March 4 – 6 (February)

One whole year of level:deepsouth— for Generation X (March)

Congratulations to the Winners of the Fitzgerald Museum Literary Contest: “Education of a Personage” (March)

Six Months into Nobody’s Home (March)

Summer Reading: Closed Ranks (April)

The Fourth (and Final) Reading Period for Nobody’s Home (May)

new page: Photography

On Instagram: Life and Education (June)

“tidbits, fragments, and ephemera” on level:deepsouth (July)

The Fitzgerald Museum’s Literary Contest and Zelda Award (August)

Year 19 in the Classroom (August)

From Judas Priest to the Dalai Lama (October)

A Quick Tribute to Hy Pyke, Gone Fifteen Years Now (October)

Children of the Changing South Turns Ten! (November)

Thank you, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts! (December)

ReadingStill Life with Oysters and Lemon by Mark Doty

and published in “Groundwork,” the editor’s blog for Nobody’s Home:

Myth, Media, and the Southern Mind (1986) by Stephen A. Smith

The Two-Party South (1984) by Alexander P. Lamis

Myth and Southern History, Volume 2: The New South (anthology, 1988) edited by Patrick Gerster and Nicholas Cords

South to a New Place (anthology, 2000) edited by Suzanne W. Jones and Sharon Monteith

The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South (2006) by Matthew Lassiter

Outside the Southern Myth (1997) by Noel Polk

The South Never Plays Itself (2020) by Ben Beard

Heritage and Hate (2021) by Stephen M. Monroe

A Movement of the People (2017) by Katie Lamar Jackson

Watching(2021)

Sustenance (2020)

Rooted in Peace (2016)

The Great Watchlist Purge of 2021

The Great Watchlist Purge of 2021: A Springtime Progress Report

The Great Watchlist Purge of 2021: A Mid-Summer Progress Report

The Great Watchlist Purge of 2021: As Done as Done is Gonna Get

and published in the editor’s blog for level:deepsouth :

Penelope Spheeris’ Suburbia (1983)

Southern Movies

The Blood of Jesus (1941)

Trapper County War (1989)

Six Pack (1982)

The 2021 Spooky, Scary Southern Sampler

Poor Pretty Eddie (1975)

December 15, 2021

Thank you, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts!

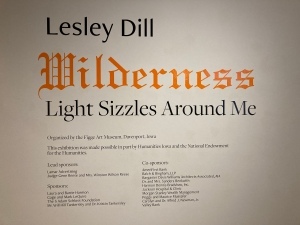

Thank you to the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts for including me in their Wilderness Inspires program last night. It was an honor to read my work alongside writers Barbara Wiedemann, Susie Paul, Jae Green, and Kirk Curnutt, sharing literary works based on the exhibit Lesley Dill, Wilderness: Light Sizzles Around Me. I read a new work titled “A Broken Haibun within the Place Where Wild Deer Go.”

Thank you to the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts for including me in their Wilderness Inspires program last night. It was an honor to read my work alongside writers Barbara Wiedemann, Susie Paul, Jae Green, and Kirk Curnutt, sharing literary works based on the exhibit Lesley Dill, Wilderness: Light Sizzles Around Me. I read a new work titled “A Broken Haibun within the Place Where Wild Deer Go.”

The event was free and open to the public and was also broadcast on the museum’s Facebook Live.