Foster Dickson's Blog, page 19

December 8, 2022

Southern Movie 62: “Bucktown” (1975)

The blaxploitation film Bucktown from 1975 has all the things: a strong hero with sideburns and a moral compass, evil and unnecessarily cruel white people, big afros, colorful clothes, groovy music . . . But this time, the story is not set in an urban ghetto or in the California hills. Instead, we’re in the Deep South, where Duke Johnson (Fred Williamson) takes on the corrupt small-town lawmen who killed his brother. Though Duke arrives alone for his brother’s funeral, he quickly gets help from Aretha (Pam Grier), a hapless drunkard (Bernie Hamilton), and a little boy who is a street hustler— that is, until he calls his friends to come down from up North and then has to deal with them, too! Directed by Arthur Marks, who would go on to make Friday Foster, JD’s Revenge, and episodes of The Dukes of Hazzard, this movie carries the 1970s cult genre out of big cities and brings it down home.

As Bucktown begins, we immediately see what’s going in. It is night, and along neon-lit city street – that does not even remotely resemble a Southern small town – we see a couple of swarthy white cops sitting in the car, ogling a prostitute who blows them kisses in return. Suddenly, a young black man comes running out of an alley, stops when he sees the police car, and runs the other way. The cops take off after him in the car, screeching through traffic, and catch up with him back by the railroad tracks. They beat him up, making no pretense at an arrest, as a stylish and handsome black man gets off the train. The new arrival witnesses their assault of the man, followed by them robbing him of his few dollars, and shakes his head at what he sees. The cops inquire toward him, but his answer is coy and he keeps moving without helping this hapless victim of police brutality. The cold-hearted officers pocket the money and go about their business.

The newcomer then walks over to cab where an old black driver lets him in the car. Now smoking a long cigar, he asks to be taken to Club Alabam. The driver makes a face and wants to know, “Son, do you believe in God?” He replies carelessly, “Sure, why not?” But the retort is quick and discomfiting, “Then you’re in the wrong place.” The elder man closes the car door, and they head off as the credits finish up.

We soon see that the club he has requested as his destination is dilapidated and has a Closed sign on it. So, this man we have yet to meet walks coolly down to the Dixie Hotel. As he approaches, two white men walk with a prostitute who promises them both a good time. Then a little boy hustles up and offers information on anything the stranger might be looking for. After finding out that drugs and prostitutes are not his thing, the boy lets the stranger know that his name is Stevie, if he needs anything later. Meanwhile, the two shady cops drive up just as the boy rides off on a motorcycle.

In the lobby, we see that the Dixie is probably a house of prostitution. The room costs $15, and our man Duke Johnson – who we now know – pays in cash. The woman behind the counter offers him some “fun,” but he is not interested. He is only in town to bury his brother. Once Duke walks away, the counter clerk calls the white police chief and tells him: a man named Duke Johnson has come for Ben’s funeral, she thought he ought to know about it. The surly-looking white chief (Art Lund) thanks her, and she reminds him that she was told to always check in and that’s what she’s doing. After hanging up, he sits down to a nice dinner, served by a black maid, and begins to pray.

The scene then shifts to a sparsely attended graveside funeral. Duke is now dressed in black leather and stands back near the hearse. Three people are near the casket: the boy Stevie from the previous night, an attractive young woman, and an older man in suit and a fedora. The preacher shares some stock phrases, then they wrap it up. As the older man hugs the young woman, he takes a pull from a pint bottle of whiskey, then calls after Duke, wondering how he might know the deceased. Duke tells him his name, and the older man Harley recognizes it, telling the others that Ben had bragged on his brother. Harley then introduces Duke to Aretha, who is not impressed. She chastises Duke for not being there to help. Duke asks what was going on that Ben needed help, but Aretha tells him that it doesn’t matter now. She and Stevie retreat to a nearby car, while Duke shrugs it off and leaves too.

After the funeral, Duke heads to the courthouse to find out about his brother’s estate. The clerk is a young black dude with a big afro who tells him that Ben left a house, its lot, and a wallet with $39 in it. Duke wants to take these assets immediately, but the clerk tells him that it will be sixty days . . . unless he wants to sign for an empty wallet. Duke remarks on the clerk’s backhanded way of doing business, but agrees. Out in the lobby, Harley and Stevie stop Duke to tell him that he should re-open Club Alabam. Then the good times will roll again! But Duke says no, all he wants is a buyer so he can get out of town. Harley and Stevie don’t like the answer but Duke doesn’t stick around for them to argue. Out on the lawn, they catch up with him and convince him to give it a try. Harley says that he could fetch a higher price if the place was open, and in the meantime, he could make money on the locals and on the soldiers at the nearby army base.

Over at the police station, Duke has to renew the club’s “city sticker.” First, he has to deal with the two police goons from the movie’s opening scene. They tell him that the sticker is $400— make that $450. About the time Duke has had it with them, the chief opens his office door, and Duke invites himself in to talk with the “main man.” Duke sits right down and puts his cigar in his teeth, and the chief remarks that he doesn’t have any manners. “I give what I get,” Duke replies. During the conversation, the chief explains that the club’s city sticker is overdue and that it will remain padlocked until the fee is paid. Duke stands up and rolls off the cash.

Over at the police station, Duke has to renew the club’s “city sticker.” First, he has to deal with the two police goons from the movie’s opening scene. They tell him that the sticker is $400— make that $450. About the time Duke has had it with them, the chief opens his office door, and Duke invites himself in to talk with the “main man.” Duke sits right down and puts his cigar in his teeth, and the chief remarks that he doesn’t have any manners. “I give what I get,” Duke replies. During the conversation, the chief explains that the club’s city sticker is overdue and that it will remain padlocked until the fee is paid. Duke stands up and rolls off the cash.

In the next scene, a white police officer and another loudmouth white guy are walking down a city street at night. They pass a neon-lit porn theatre and shake down a black doorman at another club, with the one guy cussing the whole time. After that, it’s over to the hotel to pick up the cash from one of the prostitutes, and the loudmouth sticks around to get some. Down at the bar, Harley comes in dancing and jive talking about the Club Alabam being open. Aretha is in there, drinking by herself. She is gruff with old Harley, who is a happy drunkard and an obvious screw-up, but he believes in Duke. Aretha tries to talk him out of his optimism, but it doesn’t work. Out in the street, the white officers all meet up, and we find out that they’re across the street from the Club Alabam, which is open. They decide it’s time for Duke to “join the club” and start paying.

Inside Club Alabam, they find Duke behind the bar. The insults and the shakedown begin immediately. The meanest of the officers, the one who was beating up the guy in the opening scene, tosses out racial slurs like crazy. But Duke is calm about it all. He tells them that he already paid, but they say no, they expect $100 every Saturday night. Duke’s answer is still no. He tells calls them “crackers” and tells them to leave. Over by the door, Harley and Aretha have come in and are watching the scene, as Duke takes on both cops. One goes after the cash register, and the other throws Stevie against the wall for calling them “faggots.” Duke takes his lumps, and the place gets broken up pretty good – Harley even tries to jump in – but ultimately Duke whips both their butts. The two corrupt cops end up knocked out and laying on the sidewalk. After the fight, Duke gives Aretha and Harley a piece of his mind for not warning him about the corruption and the payoffs that would be associated with opening the club.

By now, Bucktown is about a third of the way in— thirty minutes into an hour-and-a-half of action. We get the sense that this story is based loosely on Phenix City, but with a twist. We see the opportunities for sinful behavior out in the open, and Stevie mentions the soldiers from the nearby base, which would point to that scenario. However, we never actually see any of these soldiers. All in all, Bucktown doesn’t look Southern. A typical small town in the South would not have a porn theatre with clear signage and bright lights, mainstream bars wouldn’t have white and black patrons sitting around together, and there are far too many hepcats in this little town— even the courthouse clerk is styling! Moreover, Ben has lived in the town and operated the best club, and no one comes to his funeral. I don’t think so . . . But what is Southern works. There are no black cops and, after Duke wins the fight in the club, we hear the differing perspectives within the black community. Duke tells Aretha that they can eat the crap they’re handed by the whites, but he won’t, and she replies, “But we have to live here!”

After the fight, Duke heads into the police station and barges past the front desk to face off with the chief. Duke points his finger and proclaims that he won’t pay anybody any more than he already has. The chief takes it – which is also distinctly un-Southern – and calmly levels with Duke. He compliments Duke and assures himself of the black out-of-towner’s intelligence. However, his department can’t operate on the money from parking tickets. They need more revenue . . . to do things like investigate Ben’s death. Duke is puzzled, and the chief clears it up. Ben was beaten to death, but the chief says they don’t know who did it.

Later that night, Duke is chilling at Ben’s house when Aretha arrives. She is dolled up in white and carrying a six-pack of beer. At first, they’re peaceful as Aretha apologizes, but they quickly begin to argue. No one told Duke what he was facing in the little town. Aretha retorts that she has to play it safe, then she saw Duke stand up for himself. Just as it gets heated, Duke grabs her and lays a kiss on her . . . which leads the movie’s gratuitous sex scene.

The couple is awakened, however, by the three cops and their loudmouth friend. The four men are out in the yard with guns, and they blast the house up, while Duke and Aretha lay on the floor to avoid being sprayed. The onslaught is halted by the chief, who pulls up within a moment. He reminds them that too much violence will attract the attention of outsiders, who could come to investigate. Duke hears this whole conversation. After the police leave, Duke and Aretha get up off the floor, and Aretha urges him to leave town. He assures her coldly that he has never run from anything, then he picks up the phone.

On the end of the line is Duke’s friend Roy (Thalmus Rasulala), who is hosting a party, a mix of stylish black men and both black and white women. Roy comes to the phone and is jovial. He asks Duke when he’s coming back home. But Duke remains serious while asking for help without asking for help. Roy picks up on the signals, tells the pretty white woman who is doting on him to excuse him, and agrees to come down South. In the next scene, a train arrives at the station and four sharp-dressed black men get off at the station. One of the local cops is slouching on a bench, drinking a beer in uniform in broad daylight, and Roy asks him for directions. He isn’t helpful, and on their way, one of the men steps on the cop’s hat.

In town, the cool cats strut down the sidewalk as the locals gawk and stare. Stevie accosts them on the sidewalk, offering his services just like he did for Duke, but the man pass him by. At the Club Alabam, the old friends are reunited. Roy meets Harley and Aretha, then introduces his friends: Josh, TJ, and Hambone (Carl Weathers). It is immediately clear that Josh has his eye on Aretha, who is not interested.

Later in their hotel room, the crew begins to plan their next move. Aretha and Duke explain that there are a chief and four officers in the town. (This fact flies in the face of Duke’s earlier explanation to Roy on the phone that they would be outnumbered more than four or five to one.) Aretha explains that the mayor won’t be a problem, since he brought in the chief to clean up the town but can’t control him. (This trope sounds like In the Heat of the Night.) The men make another vague allusion to a previous “job” they’ve handled, and their plan seems to be in place. But before the scene is over, Josh makes a pass at Aretha who yells at him and slaps him. Roy asks what her problem, and Duke and Josh give each other the stink-eye.

Down in the street, the police are talking about the situation. They’re posted around the hotel, but the crew of black men have not come out for hours. The chief reminds them to be patient, that black people aren’t hard to handle. He also remarks that they’re the law so God is on their side.

Next we see Duke and Roy, they’re making arrangements to get started. Sitting in the strip club, Duke explains that one cop waits here on his girlfriend to get off work. The next cop spends his evenings hovering over an ongoing poker game. A third hangs around the whorehouse, because he is part owner of it. The final man stays in the police station to hear the radio. Duke and Roy agree that it’ll be easy pickings.

To get started, we see Hambone in the hallway of the hotel beating the loudmouth one who collects the money. He takes a baseball bat to the courier, who begs for mercy but gets none. Then Hambone takes the purse and leaves. Next, Roy and Duke flush one of the cops out of his apartment, causing him to go down the fire escape, where Hambone is waiting with a shotgun. He destroys the cop’s car, which goes up in flames, then unloads on the fleeing white man. The third is in the police station yelling at a black woman about wanting mustard on his hamburger when TJ sneaks in with a shotgun and does him in. The next victim is accosted at the poker game. The chase leads them out into the street, but ends with the cop being shot to death by Josh, who was hiding in the police car. The final guy is caught with one of his prostitutes, who is straddling him in the bed. She is pulled off of him and he is killed.

The last man to deal with is the chief. They find him sleeping peacefully and all alone. (Unlike his officers, he is behaving himself.) They roust him out of bed in his PJs and spend a little time musing on what to do with him. Still defiant, the chief replies that they won’t hurt him because they need him alive. In fact, the black mayor – The mayor is black! What!? – will want his chief there to recover from this situation.

In the next scene, the black mayor is overseeing his all-black staff counting the money that the officers had been taking. It comes to thousands of dollars. The squirrelly, nerdy mayor then wonders out loud how to repay the vigilantes, and Roy says slyly that they’ll figure out a way. The mayor suggests a parade in their honor, but no, that isn’t what they have in mind . . . They want badges. They want to become the police force.

Meanwhile, Duke has been on the outside of his own deal. Aretha finds him sleeping and tells him that Roy, TJ, Josh, and Hambone didn’t get on the train and leave, but are becoming police officers. Duke thinks it’s funny at first, but Aretha sees something sinister. And she’s right. Over at the jail, Hambone is sharpening a straight razor to help the chief talk about where his money is stashed. He doesn’t want to tell and calls them “street scum.” Unable to move the chief’s mind, Roy instructs Hambone to cut out his tongue.

Duke knows he has to see about what’s happening. He goes to see Roy, who is making out with a woman. Duke wants to hear it from the horse’s mouth, and Roy confirms what they are doing. He even offers Duke a badge, too. Duke says no, this is not a good idea— the thing was to stop the corrupt white cops and move on. Roy disagrees, saying that the town is his “pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.” He will be acting as the town’s enforcer, and Duke should run his club, and when Duke decides to come to his senses, there will be a place for him. Duke is skeptical.

Out on the street, it has gotten bad again. Hambone is strong-arming people just like his white predecessors. Later he meets up with Josh, who begins a conversation about his problems with Duke. Josh has been trouble since the start, and now he convinces Hambone that, if Duke and Roy weren’t friends anymore, then it would be easy to cut Duke out. That plan begins with tricking Harley into getting stone drunk, then beating him up and cutting him. He is carried out of the bar covered in blood, and Aretha and Duke show up as he is being carted off. Duke then goes to confront Roy who doesn’t appreciate being questioned, but Duke does plant the seed of doubt. Roy then questions Josh about Harley, and Josh lies, telling him that Harley was drunk and disorderly and fought them. We can see that Roy doesn’t believe it, but the rift between he and Duke is in place.

After Aretha visits Harley in the hospital, she is back in the bar with Roy. As we see Roy get out of a police car and go into the bar, Duke is across the street in the barber shop, talking to the mayor. The mayor laments this new situation, and he warns Duke that Roy is gathering forces against him. Over at the bar, Roy sweet-talks Aretha. He tries to convince her in his smooth way that she has two good choices: leave town with Duke and a roll of cash, or stay in town and run the bar without Duke. She asks about the option of her and Due both staying in town, and Roy replies, “That wouldn’t be too classy.” At first, Roy wasn’t openly against Duke. Now, he is.

And it gets worse. At night, when Josh and TJ see Aretha through the window at the house, Josh goes into get her. She stumbles on him and screams, and he punches her. But Duke is there, and he kicks that fool’s butt, gives him the beat down. When Duke throws him out in the yard, his pal gets out of the police car to help, but it’s too late. Duke brought his gun, and the antagonisms are exposed.

With about twenty minutes left in Bucktown, Duke goes to Roy’s place, and they have the showdown. Roy tells Duke that he has everyone in the town “by the balls” and proclaims that he’s not leaving. A wide-eyed Duke hears this, and it’s on. Roy calls TJ and tells him that there are new rules: everybody pays, even Duke. Back at the bar, Hambone, TJ, and Josh come in with gasoline and a shotgun to tear up the Club Alabam. Aretha and Harley try to stand up to them but can’t. An already beat-up Harley gets arrested for assaulting a police officer.

In the action-packed conclusion, Duke and Aretha are ready to take out the bad guys. Aretha comes to Roy, trying to talk him out of what he’s doing in the town, but he gives her a speech about the mean old world where people have to take what they can. She then ends up a semi-hostage of the group and tries to coax Josh into trading sexual favors for Harley’s release. But she has a trick up her sleeve, though it fails, and Josh ends up shooting the old police chief dead in his nearby cell. Soon, Duke arrives with a military-style armored truck to mount his assault on the would-be police force. After driving through a wall, Duke kills his enemies one by one. Of course, Roy is the most elusive. The two old friends agree to put down their guns and fight it out hand-to-hand. The winner gets it all, and the loser leaves town. By the end of an unnecessarily long fight scene, Duke kicks Roy’s ass and walks away with Aretha.

There isn’t much Southern about Bucktown expect the tropes it employs to execute the blaxploitation paradigm. First, while dens of sin like Phenix City did exist, the blatant exercise of gambling, strip clubs, and prostitution is not consistent with small town life. The town’s streets and the architecture don’t even look Southern at all. In fact, one building they pass several times advertises nineteen big screens for watching porn films— no small Southern town has a building large enough to have nineteen screens! In reality, these kinds of illegal and immoral behavior did (and do) exist in the South, but they are practiced in subtler ways. A second problem is that there are regular scenes of blacks and whites commingling in public: sitting in bars together, walking down the street together, even a few interracial couples. This would not have been happening in 1975, not even in larger Southern cities. A third problem: in several scenes, white lawmen are openly disrespected by Duke, Roy, and their friends, and in response, the white lawmen kowtow and take it, showing dismay and fear. The police chief even gives Duke his props after Duke barges in and drops an ultimatum. Though the reality of racist Southern mores is an unfortunate fact, this portrayal of four strong black men taking over a small town so easily and by themselves is pure fantasy. Part of the reason that it is fantasy lays in the fact that town has a black mayor. That could only happen if a small town had a vast black majority who were all brave enough to vote despite threats. In that case, such an electorate – in the post-Civil Rights South – would never have tolerated this four-man white police force. If there really was a small Southern town with a powerless black mayor and a brutally corrupt white police force, Duke and his friends would have been snuffed out quickly and immediately as a threat to white supremacy, because that tiny white minority would have been insufferably stringent. But in blaxploitation movies . . . the hero is above all that, so that’s the way it has to be. The white crooks are inept and easily bowled over.

Other minor problems exist, too. Ben’s funeral does not look like a black funeral in the South, with only three attendees. Moreover, the guys standing by who will inter the casket are white. In the South, white gravediggers didn’t bury the black deceased— black ones did. No white Southerner would have worked at a black graveyard. Another problem is Harley. If he really was an old football hero, he would have attended the local all-black high school and been very popular. But Harley is always alone, and no one talks to him except Aretha and Stevie. Finally, it is never explained how or why Ben came to this small town and ended up owning a club. In the rural South, black people had to stick close to friends and family – to places they were known and had people to depend on – and to amble unknown into a small town, operate a business and own a house, and still be so inconsequential that no one comes to his funeral . . . Man, come on. If that was true, if people were so afraid that they wouldn’t attend Ben’s funeral, then when Duke reopened the club, not a soul would have stepped foot in it.

Bucktown is not a bad movie if you watch it for what it is: a blaxploitation film. It does rely on Southern tropes but it gets too many of the nuances wrong. There really were corrupt, racist Southern police who leaned on the black community for bribes and payoffs. There really were white men who had affairs with black women. There really were places where whites and blacks commingled. But none of it happened out in the open. I guess that this town was modeled on something like Phenix City, which was cleaned up in 1954, but what it boils down to is: they got it right on the surface and wrong for real.

November 22, 2022

Welcome to Eclectic: The Environment in the News

It is heartbreaking to me to imagine what future generations will have to do without or struggle against, so that we can indulge in convenience now. My understanding is that the countdown to the year 2050 is, effectively, the Doomsday Clock of climate change, when the negative effects will become severe and irreversible. If I’m still alive in 2050, I will be 76 years old and on my out, while those who come after me will continue living in the world we leave behind. When people ask me why I recycle, compost, or avoid plastics, I answer, “Because I love my grandchildren.” I don’t have any grandchildren yet – my children are still school-age – but I am conscientious enough to assume that these yet-unborn progeny of my progeny will probably want things like air, water, and food.

I know very few people who make any efforts to curb pollution and waste. That may be due to a sentiment expressed in a disappointing story from PBS NewsHour last August: “Many in US doubt their individual impact on fighting climate change.” By contrast, I do believe that ordinary people can make a difference, but as a person who is willing to sacrifice, I feel like I’m swimming upstream, dodging and weaving among a recalcitrant majority. To be frank, almost every person I talk to about it chuckles cynically when I say that I care and suggest that they should, too. A few go even further to remark that it’s typical of a liberal like me. (I’m not all that liberal.)

The fact is that actual climate scientists – not the amateur, self-educated experts – are providing a grim assessment of our future. Near the end of October, NPR shared two stories of this ilk. In one from a few weeks ago, I heard that, essentially, plastics are not able to be recycled in the quantities we need them to be. (I still carry mine to the collection center anyway.) In another story that ran shortly thereafter, listeners learned that the UN is now calling for “urgent change,” as the current carbon-reduction goals appear to be unattainable. That latter story also shared this:

Within individual nations, the report acknowledges, are more inequities in consumption and emissions. The top 1% of consumption households pollute substantially more than the bottom 50% of households.This is an issue of environmental justice and steep, entrenched economic disparity. Andersen calls for a global economic about-face.

All of us have a role in meeting the goals. Notice that the passage above says “households.” Not corporations, not factories, not governments— households.

We can call each other names, laugh at people we disagree with, and buttress ourselves against change, but the facts remain. One day, we will all – everyone of every political leaning, in every nation on Earth – look at the distressing effects of pollution and waste, knowing that we could have done something to stop it. And when it happens, name-calling, laughing, and denial won’t do any good.

In 2050, my children will be about the age that I am now. They’ll probably be trying to do what my wife and I are doing: maintain a home, raise children, and lead a life of some quality. I hope they’ll be able to, but I fear that they won’t have what they need to do it.

To read more from Foster Dickson’s blog Welcome to Eclectic, click here.November 5, 2022

Welcome to Eclectic: “The horror! The horror!”

With Halloween in the rearview mirror, what I like to call “Horror Movie Month” is over. My affinity for horror movies began as a child in the early to mid-1980s with then-new films like Poltergeist, The Shining, and A Nightmare on Elm Street, as well as slightly older films like Friday the 13th and The Amityville Horror. These were off limits to us in theaters – as children we couldn’t get into Rated-R movies – but soon enough, they came to cable TV and VHS. We were not old enough to take girls to horror movies hoping they’d cling to us in the darkness, so for us younger boys, these frightening stories served as a test of one’s mettle. We would gather for a sleepover, wait until dark, turn out all of the lights, and put on a horror movie. We had to find out who would run out of the room, pull the blanket over his head, beg to turn it off, or worst of all, cry for momma. As Generation-Xers, our childhood was also marked by the heyday of Stephen King, who explored every terrible scenario one might imagine, from bullying victims who’d rampage the prom to pets that wouldn’t stay dead.

But not all horror movies are worth watching. My somewhat-literary attitude toward the genre says that there must be some reaching-out for meaning, some effort to explore a scenario the way that speculative fiction should. Slasher films, for example, are not interesting to me in the slightest. The blood, the gore, and the absurdly creative ways to kill or maim people – often with ordinary hardware or some tool – just don’t seem necessary or enlightening. No, the best ones require us to look inside ourselves and ask, What would I do in that situation? or What do I believe?

Perhaps the best and most frightening horror films involve situations that could really happen— or did happen. To me, The Exorcist is the scariest movie ever. (In fact, the hair on my neck just stood up when I typed that sentence.) The Amityville Horror is another great one. We have to ask, as the parents do in each of these movies, What do you do when neither scientists and doctors nor the police can explain – or stop – what’s going on? That is the source of true horror. All reasonable options are exhausted, but something must still be done. These movies dredge up our latent belief in things we can’t see, things that might want to hurt us.

Sadly, when horror movies are set down South, where I live, one of three pitifully stereotypical motifs are typically explored. The first and most obvious is the haunted mansion. This allows national audiences to presuppose that the antebellum homes that dot Southern landscape are full of mysterious entities that do not wish to be disturbed. For whatever reason, an unsuspecting person, group, or family comes to a once-grand home and wonder why it sits vacant . . . Of course, they find out. The second is the ever-popular New Orleans/voodoo/swamp scenario. Here, we must assume the presence of evil forces in a haunted place. This kind of movie can take the form of elegant productions like Interview with a Vampire, or it can manifest as low-budget things like Mardi Gras Massacre or The Witchmaker.

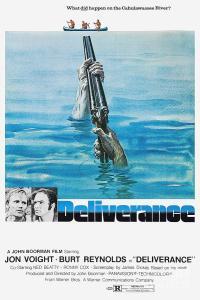

But the final one of the three may be the most pervasive and most exploited: the travelers who get lost on a backroad. This motif takes the South’s well-established disdain for outsiders and couples it with the helplessness of being far from civilization. This type of story isn’t particular to the South – The Hills Have Eyes is set in the desert Southwest, and Children of the Corn in New England – but the states of the Old Confederacy do provide a unique set of American cultural assumptions about ignorance, backwardness, and cruelty. Aside from traditional horror movies, we also can find these assumptions in mainstream Southern stories, like Deliverance and Trapper County War. These nightmare scenarios are based upon a myth: People in small towns don’t like you and won’t help you, and people in the backwoods are truly fucking crazy. This is frightening because urban cross-country travelers really can disconcerted by what hangs in the backs of their minds: these people out here could kill me and bury me, and no one would ever know.

And it is no surprise that films of the third type began gushing into the theaters in the 1970s, after the Civil Rights movement. In the 1950s and ’60s, groups of otherwise ordinary white men in small-town Mississippi committed horrific violence against Emmett Till in 1955, then against Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney in 1964. While those crimes occurred out of sight, in 1965, Alabama state troopers viciously attacked marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in plain sight. Americans could not deal with the fact that people who would commit such monstrous violence do live among us in this nation. Horror movies, like 1964’s Two-Thousand Maniacs!, presented a way to cope with the South’s intransigent legacy, while exploiting it simultaneously.

Today, mindfulness gurus and their adherents preach a gospel of deep breathing and thinking about something else, but horror movies tell us two things that we need to remember. First, there are monsters among us. Second, they can be defeated, but only when we face them. In horror movies, staying positive won’t accomplish much. Running won’t work either. Ultimately, monsters continue to do harm until they are stopped. On the screen, that end comes literally, when the creature or killer is dead or subdued. But in real life, the next atrocity is just around the corner. And just as there is always another horror movie to watch, there is always – always – another danger to face. We are never truly out of the woods.

To read more from Foster Dickson’s blog Welcome to Eclectic, click here.

October 27, 2022

The Houghton Library’s Mini-Conference: “Good Trouble”

On Tuesday evening, November 1, Huntingdon College’s Houghton Library will be hosting its annual mini-conference. This year’s theme is “Good Trouble,” a phrase that comes from the late Civil Rights activist and congressman John Lewis.

I will be giving a ten-minute presentation on the process of researching for and writing Closed Ranks. I began the research in 2013, after discussing the possibility of a book about the Whitehurst Case with the victim’s youngest son and widow. The process continued through 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017 with interviews, archival searches, and a longwinded effort to obtain federal court records. The book was contracted by NewSouth Books in 2017 and published in November 2018.

I will be giving a ten-minute presentation on the process of researching for and writing Closed Ranks. I began the research in 2013, after discussing the possibility of a book about the Whitehurst Case with the victim’s youngest son and widow. The process continued through 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017 with interviews, archival searches, and a longwinded effort to obtain federal court records. The book was contracted by NewSouth Books in 2017 and published in November 2018.

The Whitehurst Case is an unfortunate and neglected aspect of Montgomery, Alabama’s history. The victim Bernard Whitehurst, Jr. was shot and killed by a Montgomery police officer in December 1975. It was later alleged that a gun found near his body may have been placed there by police. A controversy followed in 1976, but no officers faced criminal charges in Whitehurst’s death. Ultimately, in 1977, nearly a dozen officers, including the city’s public safety director, left the department, and the mayor resigned amid charges that he was aware of a cover-up. Despite the public nature of this controversy, including the resignations, the family did not find justice in the courts, nor in voluntary compensation from the City. Thirty-five years later, in 2012, the City of Montgomery apologized to the Whitehurst family and placed a historic marker to the Whitehurst Case near City Hall. In 2015, a second marker was placed on the site of the shooting. Closed Ranks was written during the period that followed the 2012 events.

October 15, 2022

Southern Movie 61: “Macabre” (1980)

Set in New Orleans, the Italian horror-thriller Macabre weaves a complex plot that centers on an adulterous housewife whose extramarital affair goes horribly wrong. In the movie, a pretty wife named Jane Baker (Bernice Stegers) is seeing her lover Fred behind her husband’s back, but it is their young daughter who realizes what is going and reaps a terrible revenge on her mother. Directed by Lamberto Bava, Macabre also stars blue-eyed actor Stanko Molnar as the blind, homebound musical instrument repairman who provides the apartment where Jane has her affair. Like perhaps too many movies of the 1970s and early ’80s, we begin with an on-screen bit of text that tells us what we will watch is based on a true story . . .

Macabre begins simply enough with Jane Baker’s husband going to work, kissing their children on the his way to the car. He is older and bald, in a business suit and carrying a briefcase. A barely dressed Jane watches the scene with anticipation, then rushes back into the house, gets on the phone, and tells the man on the other end that they can meet in a half-hour. Outside, their children – an older daughter, who looks to be about twelve, and a son probably six – play on the lawn. The girl is clearly the dominant one, taking toys from her brother and informing him that she will dictate the rules of their game.

When Jane comes outside to tell them that she is leaving, that she has a meeting to go to, the daughter challenges her. Their mother was supposed to take them to the movies. That won’t be possible today, the mom replies. The girl is suspicious, and angry, at her mother’s betrayal.

Jane then takes a cab across New Orleans to a house, where she is let in by an old woman. The old woman’s grown son is taking a bath in the downstairs bathroom, and for some reason, his doting mother lets Jane come in there to say hello. The man Robert Duval – yes, with the same name at the actor – we soon realize is blind. Jane regards him with a smile and leaves the two to go upstairs to her apartment. Robert is clearly uncomfortable at being seen in the bath by a grown woman who is their guest.

Back at the Baker home, daughter Lucy snoops around the house, first lighting one of her mother’s cigarettes then searching for something to get into. She seems to know that something is going on with her mother. Across town, Jane gets ready for her lover to arrive, and the apartment phone rings— it is daughter Lucy calling her. Lucy has found her mother’s address book and makes the call to ask how the “meeting” is going. Jane hangs up on her, but seems unfazed and continues to prepare herself for sex.

What happens next is the horrifying part. While Jane rolls in the hay with her man Fred, Lucy coaxes her little brother into the bathroom. There, she drowns him in the bathtub. When she’s finished killing her brother, Lucy calls her mother to interrupt the liaison, but leaves out the detail that she was responsible for the death. Jane freaks out, of course, and she and Fred jump into his little Volkswagen Beetle to race toward the Baker home. Except that, in their frantic attempts to navigate the streets, Fred misses a curve. They crash into a metal guard rail, which decapitates Fred.

Next we see Jane Baker, it is one year later, and she is exiting a mental hospital, alone. She ambles back to the house where she had the apartment, and it takes the blind young man Robert a moment to answer the door. However, he lets Jane in and seems pleased to see her. We learn from their dialogue that Jane was paying rent on the apartment the whole time she was confined, and Robert says that he would have kept the place empty for her anyway. His mother has passed away, so it’s just him in the house. At this point, there is no sign of Jane’s husband or Lucy.

When Jane returns to the apartment, it is just as she left it. She opens the fridge, and somehow there are groceries waiting on her. She also notes that the icebox has a small gold lock on it, and smiles at the lock’s presence. We now know that Jane is deeply troubled, refusing to let go of her traumatic experience. We also know that the blind shut-in Robert is in love with this woman, but is too frightened to be straightforward about it. What also lets us know this is the presence of a triangle-shaped memorial to Fred, which looks like a display poster for a class project. There are pictures of Fred, as well as bits of ephemera like cigarette butts, all mounted on red velvet. This little altar-homage is something between creepy and pathetic.

From this point, we have two sources of tension, which will converge. First, Robert is in love with Jane. The problem is that Jane is beautiful and charming . . . and obsessed with a dead guy. On the other hand, Robert is quiet, squeamish, untidy . . . and blind. He is no match for the object of his affection. The second conflict revolves around Lucy, who re-enters the story when her father brings her for a very brief scheduled visit. The cuckolded husband is cold and resistant, wanting nothing to do with his former wife, while Lucy is bent on reuniting her parents. While the adults talk, Lucy looks around Robert’s house, and we get the sense that she has not mended her sneaky ways. (It is also clear that no one realized that Lucy killed her brother, that she suffered no consequences, and that she seems fine with being a murderer.)

As the plot of Macabre moves forward, the three central characters become intertwined. Robert makes attempts to show Jane that he is interested in her, but those attempts are vague and easily thwarted. Jane is so amused by his naive, shy behavior that she even calls him upstairs for a drink then gets into the bathtub naked, taunting him. She knows that he cannot see what is right in front of him. On the other front, Lucy uses his blindness in her own way, manipulating him to gain entrance to her mother’s apartment. She puts herself out there as a sweet child, then uses the fact that he can’t see to do as she pleases. First, Lucy comes when her mother isn’t home and puts a framed photo of her dead brother in the apartment. After being scolded for giving Lucy access, Robert tries to prevent Lucy when she comes back again and again. But Lucy is too sly for the young man with the kind heart. Lucy claims to want her parents to get back to together, but her actions seem aimed at making Jane suffer. Robert eventually realizes what he is enabling, by allowing Jane to stay, when he finds a human earlobe with a gold ring in it.

Ultimately, Jane Baker cannot fend off all of the crazy that she has incited. Lucy and Robert both want to know what is going on, each for their own reasons. By sneaking around quietly – in what is his house – Robert discovers Fred’s head in the icebox. When he calls the jilted Mr. Baker to rat out Jane, Lucy hears one side of the phone conversation and surmises that there is a secret to be unearthed. She rushes over to Robert’s house and worms her way in, again, to find out what the secret is. That won’t bode well for Jane either. Of course, nobody calls the police.

Lucy Baker brings it all to head in the final ten or twelve minutes by playing nice. She offers to fix dinner for Robert, who no longer trusts her, and Jane, who seems to for some reason. Lucy cooks up a soup, and the three sit down to a candlelight dinner. Jane begins to eat, while Robert is hesitant. They soon realize that bits of Fred’s head are in it. Robert takes off, but Lucy throws him down the stairs, leaving him knocked out on the landing. Jane tries to go get one of her anxiety pills, but Lucy follows her into the bathroom. There, she informs her mother of the truth: she murdered her younger brother! Jane then goes bat shit crazy, enacting some poetic justice on Lucy: the girl gets drowned in a bathtub.

If Macabre weren’t already weird enough, the director takes it one step further. With Lucy lying dead in the apartment’s tub, Jane dons her see-through nightie one more time and gets Fred’s head so they can get it on. With her dead daughter’s body soaking in the next room, Jane’s mind turns to satisfying her desire for necrophilia. Meanwhile, the running water from the bathtub overflows, rolls down the stairs, and wakes Robert up. He tries to leave but the front door is locked, the key removed. With no choice, he heads upstairs to confront Jane. Unwilling to give up her love affair with dead Fred’s frozen head, she attempts to fight Robert, who pushes her into the burning hot oven, which is still on from Lucy cooking dinner. Jane’s face is burned up, and she dies on the kitchen floor.

Now comes the real shocker. As Robert – who is blind, remember – is rooting around and trying to find something, what we don’t know. He climbs onto the bed and is feeling around where Fred’s nasty head lies on a pillow. And as Robert moves across it, Fred’s head jumps up by itself and bites into Robert’s neck! The image freezes, with Robert’s terror held in place. Text across the screen tells us that Robert Duval’s autopsy information was never revealed. No one really knows what happened to him. We are left to wonder whether Fred’s head was really alive and participating in all that sex that Jane was having with him.

Macabre is one part Diabolique, one part Psycho, one part The Bad Seed, and one part Wait Until Dark. We have adultery, creepy children, a momma’s boy, blindness, murder, and . . . necrophilia. But is it Southern? Not hardly. Because almost all of the story occurs inside of Robert’s house, it is virtually irrelevant that it takes place in New Orleans. Granted, Jane Baker does go out a few times, walking the streets of the French Quarter, but the city scenes could have really taken place in any city. She doesn’t do anything particular to the Crescent City, and frankly, the fake Southern accents aren’t even right for that city. Also, I can’t think of a less New Orleans name than “Jane Baker.” A woman with that name would live in Iowa or Indiana. Of all the names the writers could have given a sexy adulteress in New Orleans— Jane Baker, really? Though they do try to jazz it up by making Robert a guy who repairs trumpets and saxophones, he tells Lucy that he doesn’t know how to play them. Again, really— a guy in New Orleans who repairs brass horns but can’t play them? I’m sorry to say so, but: though Macabre is a reasonably good Italian thriller from its time, as a document of the South, it falls flat. If Jane’s last name had been Delacroix, if Robert had tried to woo her with a sax solo, or if she had visited a voodoo shop to animate Fred’s head, then maybe we could at least give the filmmakers a nod on the stereotype angle. The sad truth is: they didn’t check a single box.

September 20, 2022

Dirty Boots: Unencumbered

Ain’t nobody messin’ with you, but you . . .

— from “Althea” by The Grateful Dead

It was the last lines in the Gospel reading from June 26 – Luke 9:62 – that spoke to me: “. . . Jesus said, ‘No one who sets a hand to the plow and looks to what was left behind is fit for the kingdom of God.'” We had been at the lake and, though I hadn’t planned on it, I decided to come back to Montgomery with my daughter who wanted to go to Sunday evening Mass. My habit, when I arrive at Mass, is to kneel and pray for a few moments, then read the scriptures beforehand. That week’s Old Testament reading from 1 Kings made little sense to me, so I focused on the latter two, which were excerpts from Galatians and Luke. And I noticed those last lines right away.

The work of putting one’s past in the past is daunting. The Christian religion is chock-full of admonitions about forgiveness and living unencumbered, but here on Earth, our memories, judgments, and preparations are useful parts of our survival instincts. They’re also heavy burdens to bear in daily life— we try in the present to assess the future by using the past. By a worldly standard, only a fool would wander willy-nilly into tomorrow. On the other hand, tomorrow is not yesterday.

The work of putting one’s past in the past is daunting. The Christian religion is chock-full of admonitions about forgiveness and living unencumbered, but here on Earth, our memories, judgments, and preparations are useful parts of our survival instincts. They’re also heavy burdens to bear in daily life— we try in the present to assess the future by using the past. By a worldly standard, only a fool would wander willy-nilly into tomorrow. On the other hand, tomorrow is not yesterday.

Five and a half years ago, in February 2017, I wrote a post here on the blog titled “Things.” about being attached to my belongings, not because they have material value but because so many of them connect to old experiences and memories. My wife and I had watched a feel-good documentary called The Minimalists, and I was contrasting these guys’ ideas with Mark Doty’s book Still Life with Oysters and Lemon. I have long kept books, tapes, trinkets . . . because of my experiences that were tied to them. My office is littered with all manner of ephemera, an eclectic array of things that no one but me would see any reason to keep. I also wrote, a year later in January 2018, about my habit of clinging to old keepsakes in “The Boxes in the Attic: A Love Story.” When I look at any of it, I remember the story: where I was, what I was doing, who was around.

That was before the pandemic. I can’t speak for other people, but nothing has been the same for me after experiencing and witnessing what the years 2020 and 2021 brought. While most of us did survive it, those memories and revelations are not so easily put in the past. We “put hand to plow” to get through those hardships, but looking to “what was left behind” seems necessary to harvest the lessons from that suffering. So, recently, in considering that Bible verse from Luke’s Gospel, I had an idea: what if I just got rid of all the negative stuff— the things that hold the ugly reminders of past pain? And I threw out a garbage bag full: music, mementos, notes, photos, clippings. It felt good, and I haven’t missed any of things that I scrapped. In short, that small act felt like a step in the right direction, a shift toward something better.

I’m not one of those people who focuses on the positive, because some of the best lessons I’ve ever learned came from bad situations. I also saw a Thich Nhat Hanh quote on Instagram (on the right) that encapsulates why I feel that way. We got to misstep, fall down, and err in judgment in order to learn— and to be willing to! I struggle with this idea of not looking back, and sometimes intentionally remind myself of bad situations in the past so I can be aware and not repeat them. The trick, however, might be to remember and use those bad experiences without allowing them to usurp the present and the future. It’s a tightrope-walking kind of distinction, but one that seems important to embrace.

I’m not one of those people who focuses on the positive, because some of the best lessons I’ve ever learned came from bad situations. I also saw a Thich Nhat Hanh quote on Instagram (on the right) that encapsulates why I feel that way. We got to misstep, fall down, and err in judgment in order to learn— and to be willing to! I struggle with this idea of not looking back, and sometimes intentionally remind myself of bad situations in the past so I can be aware and not repeat them. The trick, however, might be to remember and use those bad experiences without allowing them to usurp the present and the future. It’s a tightrope-walking kind of distinction, but one that seems important to embrace.

September 6, 2022

The Great Watchlist Purge of 2022: A Late Summer Progress Report

*You should read the first post for this year’s Great Watchlist Purge.

As I began another Great Watchlist Purge, with over fifty movies in the list, I took a look around to see which ones were available. Not many, that’s why they were still in the list . . . Once again, my watchlist has tended to be heavy on the 1970s, so my viewing preferences haven’t changed: twenty-two of them – nearly half – were made during the Purple Decade. The oldest films on the list are 1929’s Prince Achmed and 1930’s Blood of a Poet. There is only one movie from the 1950s and one from the 1960s this time. However, there are eight from the ’80s and seven from the ’90s. The remaining films were made in the twenty-first century.

First, here are the twelve movies from the list that I’ve watched since mid-May:

1900 (1976)

I’ve liked Bernardo Bertolucci ever since I saw Stealing Beauty in the 1990s, but this four-plus-hour film was not at all the same thing. It stars Robert De Niro and Gerard Depardieu as boys then men then old men who are wrapped up in the politics of early twentieth-century Italy. Depardieu’s character is a peasant who has been raised on socialism, and De Niro is the child of landowner who doesn’t share his family’s uppity ideas about how to treat workers. Ultimately, they are both friends and enemies. While some portions of this movie did get tiresome, the end was bittersweet, and I was glad I finished it.

Haiku Tunnel (2001)

I remember this being one of the last attempts at a GenX zeitgeist films, but it came out too late— even well after the purely Hollywood takes on our generation: Singles (1992), Reality Bites (1994), and SubUrbia (1996). By the early 2000s, the youngest Xers were getting into the working world, and unfortunately for the Kornbluth brothers, all of the types and tropes had become clichés. I probably chuckled at this when I saw it the first time, but was generally disappointed in it this time.

Images (1972)

Knowing a little bit about Robert Altman, I felt that I knew what this film would be like, but it surprised me. I was picturing something like Play It as It Lays after watching the trailer, but it was more like The Wicker Man. The main character is a schizophrenic woman in Ireland, who has three men in her life: a dead husband, a current husband, and a former lover who is a friend of her current husband. The conflict comes from her mind not knowing which of them she is looking at, talking to, or sleeping with— and we don’t always know either. If that wasn’t complicated enough, she also sees another version of herself, who always seems to be far-off in the distance, until the end when she confronts herself. Yes, that’s as confusing as it sounds.

40 Years on The Farm (2012)

It has always been interesting to me that such an infamous hippie commune would exist in Tennessee of all places, and watching this documentary, I learned why. One of the early members explained that the San Francisco group led by Stephen Gaskin on a nationwide speaking tour had found friendly people in rural Tennessee, and they also saw that the East and West coasts were so heavily politicized that they wanted to avoid those regions. After a search and some minor obstruction from locals, they found a 1000-acre piece of land and started The Farm. I also hadn’t realized that Stephen from the infamous Monday Night Class was the founder. This documentary was not terribly exciting, but it was informative and well put together. I was glad to learn the backstory of this longstanding sustainable and peaceful community to my north.

Fascination (1979)

The only Jean Rollin movie I’d seen before was Shiver of the Vampires, which was hippie-weird and kind of hokey. This one was nothing like that; it was slow-paced, dark, and sinister. The story centers on a group of women who practice vampirism; they drink blood but are not vampires. They prey on a fleeing criminal who shows up at their chateau. He has double-crossed his cohorts and must get away, but he falls into something much worse. The movie’s star Brigitte Lahaie is beautiful, but there’s not much else to say about Fascination.

Zabriskie Point (1970)

When this movie began, it was seemed typical of its time and subject, and reminded me of the movie adaptation of The Strawberry Statement. The subtitle description says it is about a hippie revolutionary and an anthropology student hiding out in Death Valley, but that’s really not what the movie is about. Of the movie’s two hours, that part is about twenty minutes and has less to do with the story. Also, the way that scene is handled – as a hippie orgy, heavy with symbolism? – comes out of nowhere, since the rest of the film is stark realism.

Ravagers (1979)

I didn’t know anything about this movie, but it caught my eye for having been filmed in Alabama. The cast looked solid – Richard Harris, Ernest Borgnine, Art Carney, et al. – and the concept driving the plot seemed that way, too. But the story kind of wandered around in the space, and its style screamed late-1970s TV movie. I should have known to be suspicious when the IMDb rating was 4.3, but I was curious about the on-location stuff. So, I got what I was looking for: Alabama. I recognized Huntsville early in the film, and Mobile in latter parts.

The Beautiful Troublemaker (1991)

I was a little worried that this film would be just a bunch of rambling about abstract existential topics, since it’s four hours long and French, but there was a strong story here. An aging painter tries to recapture his old magic by restarting an unfinished work, using the girlfriend of a visiting painter as his model. Of course, there’s jealousy, ego, and the interplay of the two couples: the old painter and his wife, and the young painter and his girlfriend. The style of the film was very deliberate, sticking with shots for longer than one might expect in modern films, which emphasized the humanity of the characters through highly realistic storytelling. I liked this movie, but will admit that I started checking how much was left at about the two-hour point.

Simple Men (1992)

I knew nothing about the director or the stars of this one, but it appeared to be a GenX indie film. I gave it a half-chance, for about forty-five minutes, then admitted that it was pretty bad. The credits indicated that it was produced by a small theatre company, which I could see— a group of twenty-something stage players overacting for the camera. As for the Generation X elements: randomness, quirky characters, urban decay, absurd authority figures . . . I wouldn’t suggest watching this one, unless you’re just really into obscure ’90s stuff.

Rabid (1977)

This film reminded me a lot of Shivers, which preceded it by a few years. There was the medical angle to the horror, like Shivers, but this time, we had zombies, too. The pacing and the acting were typical of the ’70s, which was fine, but there was one major problem for me: the way the main character became the host/source of a monstrous epidemic. Somehow, a perfectly normal young woman (played by porn star Marilyn Chambers) got some skin grafts after being burned in a motorcycle accident near a cosmetic surgery resort, but while in a coma, she developed a tongue-like feeding apparatus in a hole in her armpit that murders people. I get that both horror films and Cronenberg films are supposed to be strange, but this premise didn’t fly. Something was missing in the leap from point A (healthy young woman) to point B (horror movie monster).

What the Peeper Saw (1971)

This movie was actually in the last Watchlist Purge, but I struck it after not being able to find it. Then it showed up recently in Tubi. At first, I thought it would be like The Bad Seed, but the story was more complicated than that. It took a turn similar to Images (above) or the 1990s drama Falling Down, where the person who starts out with our sympathy loses it slowly as we figure out he/she might be the actual problem. The boy they cast as the problem child is creepy, the star Britt Eckland is beautiful, and the interplay between them works. The ending is pretty gruesome— I won’t spoil it, but it’s unexpected.

Chronopolis (1982)

If I were going to describe this, I would say that it’s art-deco meets steam punk in a highly symbolic claymation sci-fi movie. This one is very abstract and mixed Polish and French. The plot, if there is one, seems to based around this amorphous substance that is living but can also be control kinetically with various tools. There is also a group of majestic but expressionless figures who are counterbalanced by – or possibly at odds with – some marionette-like mountain climbers. Chronopolis is visually very interesting, but I felt about it like I did about the surreal 1988 movie Begotten— I know watched something pretty cool, I’m just not sure what it was.

Booksmart (2019)

This was not in the original list from May, but a friend recommended this to me as “a female Superbad.” That was all I needed to add it to the Watchlist. . . . (No, I didn’t learn my lesson about adding to the list while trying to whittle it down.) This movie was laugh-out-loud funny in places, though in general, it was a little too Gen-Z for my taste. Booksmart is a best friend movie, a high school movie, a raunchy comedy, all at once. There are elements of Superbad here, but also of Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle and American Pie. I’d recommend it, yes, but if you’re over 35 years old, be prepared to spend a little time thinking condescending thoughts about younger generations.

The Psychedelic Priest (1971)

Another one that I added to the list since May, this one appeared on Tubi right after I learned about it. It was another of those might-be-terrible-but-might-be-great “lost” films— and . . . it was terrible. No story, bad acting, trite social commentary, cheap cinematography. With the alternate titles Electric Shades of Gray and Jesus Freak, it was made in 1971 but not released until 2001. It’s described as a road movie, which is one of my favorite genres, but they really just drive in the California mountains for no reason. I thought when I saw it, It could be like that Orson Welles thing with John Huston, The Other Side of the Wind, where they took the footage and made a film later, but probably less artistic and more indie . . . No, this was awful. At least hippie flicks like Zabriskie Point or Stanley Sweet have a point. This one should have remained lost.

The Downing of a Flag (2021)

This two-episode program on PBS looks back at the efforts to remove the Confederate flag from the South Carolina state capitol in Columbia after the killing of nine African-Americans in Charleston in 2015. The issue of the flag has long been an issue in Southern states, especially since 1961 when it was flown on many Southern state capitols in response to the Civil Rights movement. This two-part documentary was very well done, presenting speakers on both sides of the issue, as well as former governors and legislators who dealt with the politics of it themselves.

And as I went through the watchlist, I had one cut, too:

Salt of the Earth (1954)

This black-and-white, social justice film about the plight and lives of Mexican miners has been available on multiple platforms for quite a while. After passing up the opportunity to watch it over and over, I’ve finally admitted that I don’t really want to watch it.

So, these forty films are still in the list. So far, all of these have been harder to access, for various reasons. A few are available for rent-or-buy on streaming services, but most aren’t. A handful are foreign films that are available in a language that I don’t speak. I recently subscribed to Mubi, which has more foreign films, so we’ll if some come up.

The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1929)

I had never heard of this animated movie before seeing a reference to it on Twitter from an account that was disputing Fantasia‘s designation as the first full-length animated feature film. The clip attached to the tweet was interesting, and I want to see the whole film.

The River Rat (1984)

I found this film when I was trying to figure out what Martha Plimpton had been in. I tend to think of Plimpton as the nerdy friend she played in Goonies, but this one, which is set in Louisiana and has Tommy Lee Jones playing her dad, puts her in a different role.

The Mephisto Waltz (1971)

I’ve read about this movie but never seen it. I must say, the title is great, and it doesn’t hurt that Jacqueline Bisset is beautiful.

Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971)

This horror-thriller came up alongside Deep Red, which I watched last year, after I rated two recent horror films: the disturbing Hagazussa and the less-heavy but still creepy Make-Out with Violence. Deep Red was good, so I want to watch this one, too.

Born in Flames (1983)

This movie looks cool but is obscure. It’s an early ’80s dystopian film about life after a massive revolution. But it is difficult impossible to find. (Apple TV has it but I don’t have Apple TV.) I was surprised to see a story on NPR about it recently, so maybe it will show up.

Personal Problems (1980)

This one is also pretty obscure – complicated African-American lives in the early ’80s – and came up as a suggestion since I liked Ganja and Hess. Though the script was written by Ishmael Reed – whose From Totems to Hip-Hop anthology I use in my classroom – the description says “partly improvised,” which means that the characters probably ramble a bit.

Little Fauss and Big Halsey (1970)

Paul Newman movies from the late ’60s and early ’70s are among my all-time favorites. This one came out about the same time as Sometimes A Great Notion. Despite having seen Cool Hand Luke, Hud, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and Long, Hot Summer numerous times each, I’d never heard of this movie until a few years ago.

All the Right Noises (1970)

All the Right Noises (1970)

I found this story about a married theater manager who has an affair with a younger woman, when I looked up what movies Olivia Hussey had been in other than Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet. It looks a little like Fatal Attraction, like the relationship goes well until it doesn’t.

All the Colors of the Dark (1972)

I have memories of seeing this movie in the late 1980s when USA Network used to have a program called Saturday Nightmares, but every list that appears on the internet doesn’t include this movie as having been shown on that program. That weird old program turned me on 1960s and ’70s European horror movies, like Vampire Circus and The Devil’s Nightmare, and I could have sworn this one was on that show— but maybe not. No matter where I first saw it, I haven’t seen this movie in a long time and would like to re-watch it. However, the full movie was virtually impossible to find. One streaming service had it but said it was not available in my area, and one YouTuber has shared the original Italian-language movie . . . but I don’t speak Italian.

Deadlock (1970)

This western came up as a suggestion at the same time as Zachariah. It’s a German western, so we’ll see . . . Generally, it has been hard to find, with only the trailer appearing on most sites.

The Blood of a Poet (1930)

Jean Cocteau’s bohemian classic. I remember reading about this film in books that discussed Paris in the early twentieth century, but I never made any effort to watch it. I’m not as interested in European bohemians as I once was, but if the film is good, it won’t matter.

Landscape in the Mist (1988)

This Greek film about two orphans won high praise. I haven’t tried to find a subtitled version yet, it may be out of reach.

Phantom of the Paradise (1974)

I can’t tell what to make of this movie: Phantom of the Opera but with rock n roll in the mid-’70s?

Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb (1971)

As I’ve already shared, I just like ’70s horror movies. We’ll see if this one is any good.

White Star (1983)

This biopic has Dennis Hopper playing Westbrook. As a fan of rock journalism, I couldn’t not add it to the list!

The Strange Color of Your Body’s Tears (2013)

This French thriller, which came up as a suggestion from All the Colors of the Dark, caught my eye with the wonderful artwork on its cover image. The title is also compelling, and those two factors led me to see what it was. It didn’t hurt that the description contained the phrase “surreal kaleidoscope.”

Cronos (1993)

A mid-1990s film by Mexican director Guillermo del Toro, who later made Pan’s Labyrinth, which is an incredibly beautiful film. (He also made The Shape of Water, which won an Oscar a few years ago.) I had never heard of this movie at the time, but found it when I went down the rabbit hole of seeing what else the director of Pan’s Labyrinth made.

Da Sweet Blood of Jesus (2014)

Though I’ve seen most of Spike Lee’s movies, this one got past me. It doesn’t look at all like his classics Do the Right Thing or School Daze, so I’m curious to what it will be.

Valérie (1969)

Not to be confused with Valerie and Her Week of Wonders, this film is a Quebecois hippie film about a naive girl who comes to the city to get involved in the modern goings-on. This one came up as related to Rabid, but only has 5.1 stars on IMDb— it may be a clunker, we’ll see . . .

The People Next Door (1970)

I’ve been a fan of this movie’s star Eli Wallach since seeing The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, but this film will certainly be nothing like that one. This movie is about a couple in New York whose daughter ends up being on drugs. The premise and title remind me of the ultra-depressing Ordinary People and also of one subplot in the more recent film Traffic. Some of the reviews reference TV movies and those short films that were meant to scare kids into not doing drugs. I hope this is better than either of those genres.

The Slums of Beverly Hills (1998)

I remember seeing this movie when it came out but not much about it. I do remember it being funny in kind of an off-color way. In short, I’d like to watch it again.

Cat People (1982)

This is Natassja Kinski a few years before Paris, Texas. Early ’80s horror, but perhaps its redemption will come in its cast: Malcolm McDowell, Ed Begley, Jr., Ruby Dee, et al— a whole host of ’80s regulars. (Also John Heard, the jerky antagonist in Big, and John Larroquette from TV’s Night Court.) It’s possible that this movie won’t be good, but I’ll bet two hours on it and find out.

The Decameron (1971)

The Decameron (1971)

About ten years ago, I read The Decameron – the Penguin Classics translation into English – over the course of about a year, reading a story or segue each night. (Every year, I make a New Years resolution to read another one of the Western classics that I haven’t read, and this book was part of that annual tradition.) So, when I saw that Pasolini had done a film version, I was intrigued— how would anyone put 100 stories held within a frame narrative into a film? Well, he didn’t . . . He sampled from them. The Italian-language version is available on YouTube, but of course, I don’t know what they’re saying. I’d like to find this film with English subtitles.

The Amorous Adventures of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza (1976)

This film caught my eye because Hy Pyke is in it. Sometimes “erotic” means porno, and sometimes it means that there are just some gratuitously naked people. This movie was made in Spain, which is appropriate for Don Quixote. I seriously doubt if this one is up to par with Orson Welles’ version, but it should be good for a chuckle or two— if I can ever find it.

Tanya (1976)

Somebody, in the mid-1970s, made a sex comedy out of the basic plot line of Patty Hearst and the Symbionese Liberation Army. This movie is probably terrible, but it’s also hard to find. It appears that this was the only film for director Nate Rogers, who gave himself the pseudonym Duncan Fingersnarl, which is both creepy and gross. The young woman who stars in the movie was a topless dancer who also starred in one of Ed Wood’s movies. I serious doubt that Tanya is any good, but I have to admit that I’m curious . . .

The Lobster (2015)

I had to add this movie to the watchlist. The director made Killing of a Sacred Deer, which was infuriatingly tense, and Dogtooth, which was disturbing, and Colin Farrell was great in In Bruges. So, add it all up into a dark comedy, and I want to see it.

The Dreamers (2003)

Another Bertolucci film, this one set in 1968 in Paris during the time of student riots. The star here, Michael Pitt, I recognized from supporting roles in Finding Forrester in the mid-1990s and The Village in the early 2000s.

Burning Moon (1992)

What fan of strange horror films could resist this description of a German film made in the 1990s: “A young drug addict reads his little sister two macabre bedtime stories, one about a serial killer on a blind date, the other about a psychotic priest terrorizing his village.” The information on it says that it is really gory, which doesn’t interest me as much as tension and suspense do, but I’d like to see this for the same reason that I wanted to see House before.

The Double Life of Veronique (1991)

This film is French and Polish, and follows two women leading parallel lives. Though the film may be nothing like it, the premise reminded me of Sliding Doors, but this film preceded Sliding Doors by seven years. It gets high marks in IMDb, so it should be good.

Lamb (2021)

This came up as a suggestion on Prime, then it went to Rent or Buy status, and I should’ve watched it when it was available. I’ll probably bite the bullet and rent it sometime.

The Order of Myths (2008)

This documentary about the krewes involved in Mobile’s Mardi Gras was recommended by a friend who is a folklorist. I’ve written a good bit on the culture of Alabama, which is my home state, and I understand that this documentary caused some controversy when it was released.

Eddie and the Cruisers (1983)

I remember this being a really good movie. I like early 1980s Michael Paré generally – mainly from Street of Fire – and the Springsteen-esque main song from the soundtrack was really good: “On the Dark Side” by John Cafferty and the Beaver Brown Band. But this movie is virtually absent from streaming services.

The Spirit of the Beehive (1973)

An early ’70s Spanish drama set in 1940 about a seven-year-old girl who goes into her own fantasy world after being traumatized by watching a film adaptation of Frankenstein. I had never heard of the director Victor Erice, but browsing his other films, I’m excited to see what he does.

Wrong Turn (2003), Burnt Offerings (1976), and Session 9 (2001)

All three of these made it onto the watchlist from a documentary called The 50 Best Horror Movies You’ve Never Seen. I’d seen more than half of them, but these three I had not. They were numbers 39, 30, and 19, respectively.

Even Cowgirls Get the Blues (1993)

Based on the Tom Robbins novel, this film was one I remember watching when I was college-age. But I haven’t seen it in a long time, and now, it’s rather hard to find. Sadly, the movie gets low ratings on sites like IMDb, but I remember Uma Thurman being good in it. Right after this, she was in Pulp Fiction then Beautiful Girls, which were easily better movies, but I still don’t think this one was bad at all. I’d like to re-watch it.

Three Women (1977)

I actually ran across this one on one of the movie-themed Twitter accounts I follow. The description on IMDb says, “Two roommates/physical therapists, one a vain woman and the other an awkward teenager, share an increasingly bizarre relationship.” Sissy Spacek and Shelley Duvall star.

Shadow of the Vampire (2000)

Two of the most unique actors around, John Malkovich and Willem Dafoe, star in this story about the filming of 1922’s Nosferatu.

Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983)

Last, but certainly not least: I remember watching this movie as a boy. Jason Robards stars as an older father whose son is enthralled with a carnival that has come to town, but the carnival is a front for a sinister group of evildoers. Now, this movie is very hard to find. It’s not on any of the major streaming services, and a general search on Roku yields nothing.

As for those other movies that I added to the list . . . here they are:

Brother on the Run (1973)

I love blaxploitation films. There are literally hundreds of them, some look pretty cheesy, most are low-budget. This one looks like it could be better than most. The poster art caught my eye, to be honest, and the main character is a teacher or a professor, which is very different than most of the movies in this genre.

Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975)

This one was made by Peter Weir, who later made Gallipoli, Witness, and Dead Poets Society— all good movies. The description says, “During a rural summer picnic, a few students and a teacher from an Australian girls’ school vanish without a trace. Their absence frustrates and haunts the people left behind.” That’s just too tantalizing to turn down.

The Little Hours (2017)

I don’t know how I missed this one, as a Catholic, as a fan of Saturday Night Live, and as someone who has read the Decameron. I would watch this for Fred Armisen alone . . .

Synecdoche, New York (2008)

I remember this film coming out but I never went to see it. The director Charlie Kaufman wrote the script for Being John Malkovich and made Adaptation and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind in the years prior to making this one. I had to add it.

August 23, 2022

A Quick Tribute to “Mountain Man” Bill McKinney

Rewatching Deliverance to write last week’s Southern Movies post got me to thinking about . This unfortunate soul has gone down in the movie history as the “squeal like a pig” guy, but his legacy is much more than that, especially to a GenXer like me.

McKinney was born in Chattanooga, Tennessee in 1931. His IMDb bio shares that his family moved often, and “when [they] moved from Tennessee to Georgia, he was beaten by a local gang and thrown into a creek for the offense of being from the Volunteer State.” However, a stint in the Navy landed him in California, where he became part of The Actors Studio in the 1960s. After some minor roles on TV, he was cast as the Mountain Man in Deliverance.

This role is brief but haunting. From the moment we see him, the Mountain Man is standing on the shore, ready to accost the unwitting suburbanites. He speaks first with a threatening, “What the hell do you think you’re doing?” and then proceeds to taunt and then rape a man who did nothing more than happen by. When he is done, he comes over, sweating and panting, to his accomplice and asks how he wants to abuse the other man they’ve trapped. It’s a brutal part to play, and despite the fact that it only last seven minutes, I would say that no one who watches that scene will ever forget it.