Foster Dickson's Blog, page 15

June 4, 2023

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week 190

Show me a man who has forgotten words . . . so I can have a word with him.

— attributed to the Chinese poet Chuang Tzu in The Tao of Symbols by James N. Powell

Read more: The QuotesMay 28, 2023

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week 189

When broadly based on a good knowledge of Western European history (including that of the the United State), the historical sense is a comforter and a guide. The possessor understands his neighbors, his government, and the limitations of mankind much better. He knows more clearly not what is the desirable, but what is possible. He becomes “practical” in the lasting sense of being taken in neither by panicky fears nor by second-rate Utopias. It is always some illusion that creates disillusion, especially in the young, for whom the only alternative to perfection is cynicism. The historical sense is a preventative against both extremes.

from the chapter “Clio: A Muse” in Jacques Barzun’s Teacher in America

Read more: The QuotesMay 23, 2023

Alabamiana: Albert Brewer vs. the Drive-Ins, 1969

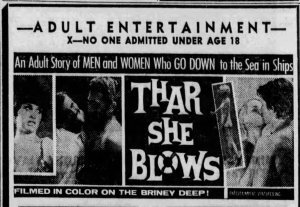

The headline was a big, bold one in the “City Page” section of the July 10, 1969 Alabama Journal: “7 State Theaters Hit in Attack on Smut.” Governor Albert Brewer had ordered state and local law enforcement to take swift action against drive-in movie theaters that were showing pornographic films. The article named the seven theaters along with the films being shown at the time of the raid. Hartselle’s Ranch Drive-In was showing Shanty Tramp, while Auto Movie No. 1 in Midfield had Thar She Blows for its patrons. Both the 80 West Drive-In near Selma and the Festival Cinema in Birmingham were putting Starlet up on their screens. The Etowah Arts Theater in Attalla was offering Barbette. The Tide No. 2 in Tuscaloosa featured The Secret Lives of Romeo and Juliet, while The Jet Drive-In in Montgomery’s was screening Inga.

The headline was a big, bold one in the “City Page” section of the July 10, 1969 Alabama Journal: “7 State Theaters Hit in Attack on Smut.” Governor Albert Brewer had ordered state and local law enforcement to take swift action against drive-in movie theaters that were showing pornographic films. The article named the seven theaters along with the films being shown at the time of the raid. Hartselle’s Ranch Drive-In was showing Shanty Tramp, while Auto Movie No. 1 in Midfield had Thar She Blows for its patrons. Both the 80 West Drive-In near Selma and the Festival Cinema in Birmingham were putting Starlet up on their screens. The Etowah Arts Theater in Attalla was offering Barbette. The Tide No. 2 in Tuscaloosa featured The Secret Lives of Romeo and Juliet, while The Jet Drive-In in Montgomery’s was screening Inga.

So what was the problem? The theaters were in violation of a law that was passed in 1909 and updated in 1961: Section 374, Title 14 of the Code of Alabama. It read, in part:

” Importation, sale or possession of obscene printed or written matter; penalties. — (1) Every person who, with knowledge of its contents, sends or causes to be sent, or brings or causes to be brought, into this state for sale or commercial distribution, or in this state prepares, sells, exhibits or commercially distributes, or gives away or offers to give away, or has in his possession with intent to sell or commercially distribute, or to give away or offer to give away, any obscene printed or written matter or material, other than mailable matter, or any mailable matter known by such person to have been judicially found to be obscene under this chapter, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and, upon conviction, shall be imprisoned in the county jail, or sentenced to hard labor for the county, for not more than one year, and may be fined not more than two thousand dollars for each offense, or be both so imprisoned and fined in the discretion of the court.

By the late 1960s, the concept of obscenity was being tested in courts all over the country, and Alabama’s place in the middle of the Bible Belt made it a worthy locale for such tests. Of course, sexually explicit texts and artwork have existed for millennia, but this subject matter had gotten a boost in modern times from technologies like photography and cinema. The rulings in the 1956 Howl case and other cases like it meant that conservatives, neophobes, prudes, and other moralists were losing the culture wars, something they weren’t happy about.

One of those conservatives was Albert Brewer, Alabama’s lieutenant governor who became governor after the death of Lurleen Wallace. The Encyclopedia of Alabama remarks about Brewer that, despite progressive efforts to improve education funding and reduce cronyism in state government, he was still a “life-long Baptist” and a “conservative in certain areas.” Which could explain his next move a few days later that broadened the crackdown. This time, the manager and assistant manager of the Ritz Theater in Montgomery were arrested for showing Angelique in Black Leather and previews of Love Camp No. 7 and A Young Man’s Wife. Both men posted bond and were out the next day. Once again, the issue of underage patrons came up. Officers from the state police and the vice squad had gone incognito in plain clothes to observe the scene, then to take action. And once again, the copies of the films were confiscated. Since these raids were becoming a habit, this might have been Brewer’s coup de grace in an effort to cast himself as the kind of guy that Alabamians would elect in 1970 to be their governor. (He announced his candidacy around this same time.)

Yet, it didn’t take long for the theater owners and the filmmakers to fight back. By July 18, four of the seven drive-in owners were filing federal lawsuits against the state, Governor Brewer, Public Safety Director Floyd Mann, and others. Joining the theaters as plaintiffs was Entertainment Ventures, Inc., the company that made the some of the films. Among the plaintiffs’ objections were that these films had been shown many times already without incident and without legal action: Starlet had been showing for more than two weeks, and Thar She Blows had been shown more than three hundred times. Another objection was that patrons in attendance during the raids had their names and birthdates taken down by officers. Law enforcement regarded that as making sure that everyone was over age 18, while the theater owners saw it as “harassment.” The lawsuits sought monetary damages, the return of confiscated films, and an injunction from further harassment.

A few days later, the infamous Judge Frank. M Johnson, Jr. ruled that the four cases should be combined for trial. The July 23, 1969 Montgomery Advertiser explained the plaintiffs’ issues with raids: no hearing had been held in advance to determine whether the films themselves were problematic, and no warrants had been issued for the raids to be undertaken. Also noted in that article was an additional “complaint” against one state trooper made by the owner of Tuscaloosa’s Tide No. 2 drive-in, stating his aggravation that the undercover officer had sat through the film and waited until it was almost over to begin arresting people.

By the fall of 1969, it was not looking good for state officials. A judge ruled that they had to return the films they’d seized from the theaters in the raids. While the ruling didn’t go into whether the films themselves were or were not obscene, it did say that the Alabama law violated the First and Fourteenth Amendments, with respect to freedom of expression. Those were not the only problems: while the original law delineated age 18 to see or possess such material, a more-recent statute had the age set at 16.

The combined cases went to trial in late 1969 in the Middle District of Alabama, with a three judge panel presiding: Richard Rives, Frank Johnson, and Virgil Pittman. The first order of business was to make it clear that the judges would not be watching the films:

The Court stated also that, to decide the issues developed under the present state of the law and facts, there is no necessity for it to view the motion picture films or to make any finding as to the obscenity vel non of any of the films.

Ultimately, the court ruled against Brewer and the state’s law enforcement officials. Acknowledging that “a state possesses power to prevent distribution of obscene matter,” the three-judge panel also declared that “a state is not free to adopt whatever procedure it pleases without considering the possible consequences for constitutionally protected speech.” Because the “seizures of the various films in these cases were admittedly made without a search warrant or pursuant to an arrest warrant,” the seizure was unconstitutional. The problematic thing here was that the discretion of whether a film was obscene was left to an individual police officer, rather than to a judge who would issue a warrant.

. . . if two conditions are met the film may be seized prior to an adversary hearing: (1) The judge himself must view the motion picture before issuing the warrant, or in some other manner must make a constitutionally sufficient inquiry into the factual basis for the officer’s conclusions, and (2) existing state law must limit the holding of the film to a brief specified period within which the obscenity vel non of the film must be determined after an adversary hearing or the film must be returned to the exhibitor.

Notwithstanding the hasty overreach, it seems reasonable to say that Brewer saw two opportunities in this crackdown. First, he could use his office to impose his conservative social views on other people, and second, he could stir up support for a 1970 gubernatorial campaign among conservative voters. Lieutenant Governor-turned-Governor Brewer had served only a partial term since 1968, and it was no secret that he wanted to be elected for a full term in 1970. However, Brewer’s goal was too lofty in an Alabama where George Wallace still held sway. He did manage to beat Wallace in the Democratic primary, but “the little fighting judge” took it to mattresses in the runoff. According to the EOA:

The Wallace camp whispered claims ultimately proven true of Republican support for Brewer, spread nasty and untrue rumors about Brewer’s family, and spread doctored photographs of Brewer in friendly poses with controversial black activists. Wallace supporters covered Brewer bumper stickers with their own that read, “I’m for B & B: Brewer and the Blacks.”

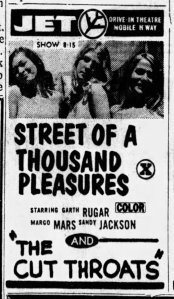

Brewer might have pulled a trump card in going after masturbators, but it was no match for Wallace’s tried-and-true tactics as a master race baiter. Not only did Brewer’s efforts fail to win him the governor’s office, they also failed to stop porn films from being shown. The ad shown at right was from 1972, where the Jet drive-in was showing Street of a Thousand Pleasures. But the fight did continue. Montgomery’s Capri Theatre courted controversy in late 1973 and early 1974 when it showed Last Tango in Paris. The debate over whether it was obscene to the point of being illegal was settled once again by a three-judge panel, who ruled in favor of the movie house. Perhaps to rub it in, the Capri showed Emmanuelle in May 1975 and Russ Meyers’ Super-Vixens later that year. Around the same time, the case Ballew v. State of Alabama went all the way to the state’s Supreme Court in 1974. It involved a Mobile bookstore owner who sold a copy of Penelope No. 1 to a man who was over 18 years of age. Yet, the magazine contained pictures of female genitalia, so it was considered “hard-core pornography.”

Brewer might have pulled a trump card in going after masturbators, but it was no match for Wallace’s tried-and-true tactics as a master race baiter. Not only did Brewer’s efforts fail to win him the governor’s office, they also failed to stop porn films from being shown. The ad shown at right was from 1972, where the Jet drive-in was showing Street of a Thousand Pleasures. But the fight did continue. Montgomery’s Capri Theatre courted controversy in late 1973 and early 1974 when it showed Last Tango in Paris. The debate over whether it was obscene to the point of being illegal was settled once again by a three-judge panel, who ruled in favor of the movie house. Perhaps to rub it in, the Capri showed Emmanuelle in May 1975 and Russ Meyers’ Super-Vixens later that year. Around the same time, the case Ballew v. State of Alabama went all the way to the state’s Supreme Court in 1974. It involved a Mobile bookstore owner who sold a copy of Penelope No. 1 to a man who was over 18 years of age. Yet, the magazine contained pictures of female genitalia, so it was considered “hard-core pornography.”

The State of Alabama has never been friendly to the porn industry, and this fight didn’t end in the early 1970s either. James H. “Jimmy” Evans expended a good bit of energy combating adult movies and magazines first as Montgomery’s DA in the 1970s and ’80s then as the state’s attorney general in the 1990s. Which leads to two major rhetorical questions: if Alabamians dislike porn so much, how did these bookstores and theaters get their business licenses, then how did they stay in business? If a drive-in was showing Thar She Blows three hundred times, it’s because people were coming to see it. Moreover, people kept patronizing these films, even when criminal charges were a possibility. As with so many things, the public face and the private reality were different. So, politically, the only acceptable and respectable stance was to oppose it— which was how Albert Brewer tried to bolster his chances in a bid for Alabama’s highest public office. Why not attack the peddlers of “smut” . . . who’s going to defend them?

May 21, 2023

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week 188

Stories are wonderous things. And they are dangerous.

from “‘You’ll Never Believe What Happened’ Is Always a Great Way to Start” in Thomas King’s The Truth about Stories: A Native Narrative

Read more: The QuotesMay 14, 2023

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week 187

So I would like to recommend a code for creative nonfiction writers— a kind of checklist. The word “checklist” is carefully chosen. There are no rules, laws, or specific prescriptions dictating what you can or can’t do as a creative nonfiction writer. The gospel according to Lee Gutkind doesn’t and shouldn’t exist. It’s more a question of doing the right thing, following the golden rule: Treat others with courtesy and respect.

First, strive for the truth. Be certain that everything you write is as accurate and honest as you can make it. I don’t mean that everyone who has shared the experience you are writing about should agree that your account is true. As I said, everyone has his or her own very precious and private and shifting truth. But be certain your narrative is as true to your memory as possible.

— from “The Creative Nonfiction Police?” in In Fact: The Best of Creative Nonfiction edited by Lee Gutkind

Read more: The QuotesMay 7, 2023

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week 186

The general feature of life that I want to evoke is its fundamentally dialogical character. We become full human agents, capable of understanding ourselves, and hence defining an identity, through our acquisition of rich human languages of expression. For purposes of this discussion, I want to take “language” in a broad sense, covering not only the words we speak but also other modes of expression whereby we define ourselves, including the “languages” of art, of gesture, of love, and the like. But we are inducted into these in exchange with others. No one acquires the languages needed for self-definition on their own.

— from Charles Taylor’s The Ethics of Authenticity

Read more: The QuotesApril 30, 2023

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week 185

We are now in a position to answer the view that human culture is an inexcusable frivolity on the part of creatures loaded with such awful responsibilities as we. I reject at once the idea which lingers in the mind of some modern people that cultural activities are in their own right spiritual and meritorious—as though scholars and poets were intrinsically more pleasing to God than scavengers and bootblacks. [ . . . ] We are members of one body, but differentiated members, each with his own vocation.

— from CS Lewis’s “Learning in War Time”

Read more: The QuotesApril 29, 2023

Thirteen Years of Unapologetically Eclectic Pack Mule-ing

Thirteen years ago today, I put up that first post. I had just finished a Surdna Foundation Arts Teacher Fellowship, which I used for the Patchwork project, and had been blogging that year about modern life in Alabama. So, with a phrase from a poem I wrote in 2002 – “pack mule for the new school” – I started my own blog. At that time, in 2010, I considered myself something of a writer and activist-educator, having taken part in a variety of committees and projects mostly devoted to reviving or sharing the history of the Civil Rights movement. Most of my student projects had also revolved around these subjects – bringing often-untold stories to a new generation – and that idea of being one simple, humble worker in the ongoing movement for social justice was what led me to that title. I saw myself as one relatively unimportant person doing humble tasks within the groundwork for social justice. My speciality: helping to create a more vibrant and more public recognition of the South’s actual history and current reality.

Yet, as the 2010s progressed, I began to notice the tenor of social-justice work was intensifying and becoming compartmentalized. In 2011, Occupy Wall Street applied a greater degree of urgency to the economic challenges coming out of the Great Recession. After the deaths of Trayvon Martin and others, the Black Lives Matter movement emerged, took to the streets, and became prominent on social media. During those years, a growing LGBTQ movement saw a major victory in the 2015 Obergefell ruling. Among these societal changes, I noticed how my roles among local social-justice groups was diminishing. Since the early 2000s, I had worked mostly among older people (Boomers) seeking to enshrine the history of the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s. By the mid-2010s, the mantel had been taken up by groups and projects led mostly by Millenials, who were seeking to reclaim the narratives: to have female voices telling female stories, to have black voices telling black stories, to have LGBTQ voices telling LGBTQ stories, and so on. While I had no problems with that new approach – in fact, I understood completely – it had real effects on my role in this work that I had been doing from my late twenties through my early forties. This new approach meant that the attitude toward me as a participant in social-justice projects became: Thank you for service, but your presence will not be necessary.

It took a while for that to sink in. But once I had fully recognized and accepted that reality, the name of this blog changed from “Pack Mule for the New School” to “Welcome to Eclectic” in June 2018. Later that year, I felt the impact of the new reality most sharply after the release of Closed Ranks in November 2018. Though local media gave the book some coverage, local social-justice groups showed no interest in it, even though it tells one of Montgomery’s most significant social-justice stories. By then, the once-regular invitations to join committees and other planning groups had all but stopped coming, and my own efforts to join in were usually met with indifference. Also, though this was completely unrelated, school system policies for field trips had become very stringent (out of fears about injuries and lawsuits), and the resulting inability to get my students out into the community all but halted what was left of my activist-educator work. The last of those student projects, Sketches of Newtown, was undertaken prior to and during the ultra-restrictive years of the COVID-19 pandemic. I could tell, as we tried to get that project done, that it would be the last one of its kind.

Today, in the early 2020s, in a post-pandemic society, my role in our local community and my work with the history of the South have taken on a markedly different shape. I am no longer a public school teacher, and taking a cue from the social-justice groups that I described above, much of my writing work is now centered on being a GenXer telling GenX stories. Though I am still keen on issues of race, gender, identity, economics, education, and equity, it was time to accept my role as an ally to groups who want to tell their own stories, and to step aside gracefully and without complaint. For about a decade-and-a-half, I played many small roles in progress by working with the Southern Poverty Law Center, the Selma-to-Montgomery National Historic Trail, the Rosa Parks Museum, the Freedom Rides Museum, and other institutions. I also played various roles in publishing books and educating young people. Since 2020, I’ve been focused on building two projects that suit my place in this new reality: Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore and level:deepsouth— for Generation X.

The only chagrin I have about what I see among current social justice efforts is this: the progress being made is disappointing. In Alabama, where I live, a conservative supermajority took over the legislature, the governor’s office, and the courts in 2010, and they are not going to be moved by public art, social media, symbolic gestures, and online shops. The Alabama Republican Party’s staggering disregard for solving glaring problems in schools, prisons, healthcare, poverty, and jobs will necessitate the successful implementation of substantive policy reforms, like restructuring tax codes, budgets, and criminal codes. A new generation of activists who intend to improve life here must learn the deepest truths of history and, with a fact-based understanding, carry forward what worked : community organizing, issue-driven politics, coalition building, voter mobilization, legal challenges, and reliance on institutional support to achieve goals. Right now, those elements are either woefully lacking or absent in an environment that is rhetoric-driven and compartmentalized.

After all these years have passed – a lot has changed between 2010 and 2023 – my beliefs about this state, its culture, the South, and the answers to the problems remain pretty solid. We do need to excise and exclude the shysters, the profiteers, and the resumé-builders from the meaningful work of building a better society, but what we want can only come if we embrace inclusion and community, allowing contributions from all people of good will. The way I see it, all of us have to live together, so all of us should be involved in the giving, taking, cooperating, compromising, and creating. For now, I’m spending my energies in ways that I believe I can be useful: serving students as an educator, critiquing the ways that narratives have been used to craft beliefs and myths in the modern South, exploring the history of Generation X in the modern South, examining how movies have shaped the way that the South is regarded, recognizing and promoting young writers, and writing substantive histories that have not yet been written.

If somebody were to ask me at this late date, why should I read your blog? For an independent perspective. I’m a liberally conservative moderate and a Southern Christian who isn’t Protestant. I am also among a distinct minority of Southerners with a graduate-level education. All in all, I’m a whole lot more likely write things you haven’t read everywhere else. That may not be the thing for folks who like single-issue politics with simplified platforms and agendas that rely on heuristics and stereotypes, but it’s the only way that works for me.

Read More: Books • On Life & Education • Poetry • Nobody’s Home

April 23, 2023

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week 184

SYNOPSIS:

This bill would prohibit certain public entities, including state agencies, local boards of education, and public institutions of higher education, from promoting or endorsing, or requiring affirmation of, certain divisive concepts relating to race, sex, or religion.

This bill would prohibit certain public entities from conditioning enrollment or attendance in certain classes or trainings on the basis of race or color.

This bill would also authorize certain public entities to discipline or terminate employees or contractors who violate this act.

— from the page-one introductory text to Alabama’s version of the “divisive concepts” bill HB7, which is currently under consideration in the state legislature

Read more: The QuotesApril 20, 2023

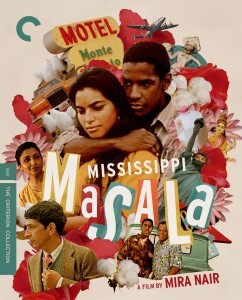

Southern Movie 64: “Mississippi Masala” (1991)

The 1991 film Mississippi Masala tells the story of an interracial love affair between an African-American man and an Indian woman. Set in Greenwood, Mississippi in 1990, we see the crossroads where a family of Indian immigrants who have fled political violence in Uganda meets the black community in the small-town Deep South. The film, directed by Indian-born and Harvard-educated Mira Nair, stars Denzel Washington and Sarita Choudhury as two lovers who first meet through a fender bender. Their affair develops amid the conservative Indian culture of her parents, who live at a motel and run a liquor store, and his work as the owner of a carpet cleaning business.

The first fifteen minutes of Mississippi Masala have nothing to do with Mississippi. An Indian family is living in Uganda during the rise of Idi Amin, and pro-African sentiments have led to a political situation in which non-Africans are not welcome and probably not safe. To exacerbate that danger, the father – who is a lawyer – has gone on BBC radio and criticize the oncoming regime. His African best friend advises him to leave Uganda as soon as possible. With tears and chagrin, the Indian family does pack up a few belongings leave, and unfortunately they must move so quickly that they leave much of their wealth and property behind. They are harassed by armed soldiers as they board a bus then an airplane, but ultimately do escape. During all this, our main character Mina is a little girl, old enough to be aware and frightened but too young to perceive fully what is going on.

Though the flight of an Indian lawyer and his family may have little to do with late-twentieth century Greenwood, Mississippi, this early portion of the film makes a clear statement: the family was removed for reasons driven by racism. But this time, the racism was perpetrated by black people. This ethnically Indian family had done nothing wrong. They were productive members of the community and good citizens. Their only crime was not being ethnically African, and within the larger framework of that pro-African sentiment, even the Africans who loved them and valued their presence would not be able to protect them from the racism that was sure to bear terrible fruit. Anyone who knows anything about the history of the South, and the history of Mississippi more specifically, should recognize some parallels here.

As the opening credits roll, we see a map that depicts the family’s trek across continents. Their first destination is England, and then as the music shifts to the blues, we follow the panning camera to where our story will occur: Greenwood, Mississippi.

The first image we see of Mina, our main character, she flips her thick main of hair out of her face, while she is shopping in a modern American supermarket. A bit of text shows on the bottom right of the screen, which tells us where we are and that it is August 1990. Mina is beautiful and young – we could guess that she is in her early 20s – and for some reason, she is purchasing an unusually large amount of milk, with numerous jugs and cartons overfilling her cart. As she struggles with the heavy buggy, we hear an older Indian woman calling her name, and when they meet up, Mina asks if this will be enough. “You wanted to serve milk at the wedding,” Mina reminds her, and they go to pay. When the cashier cracks a bland joke about her purchase, Mina stares at him coldly. The older woman seems indifferent. Soon, they are outside the Piggle Wiggly as a bag boy loads paper bags into their trunk. The older woman is sitting alone in the back seat, and Mina gets in to drive.

Immediately, we see the cultural differences between the Indian immigrants and the people of the South. First, I cannot imagine anyone serving milk at a wedding in August in Mississippi. Second, it is pretty common in the South to make a harmless joke about an unusual occurrence for the purpose of inquiring discreetly for an explanation. About the milk, the boyish cashier is hoping for a word about why they are buying nearly three-dozen gallons of milk, but he gets nothing and thus says, “Hey, I was jus’ trying to be friendly.” He really was. But the newcomers don’t get that. They see a guy being rude about their way of doing things, when he was actually trying to open a door and have a conversation.

On the way home, Mina is speeding down a dirty street lined by dilapidated buildings. The older woman in the back seat is telling her to slow down, then when she turns around to retort, Mina rear-ends a van that is stopped in the road. The front of her car is smashed, and next we see, the owner of the van gets out. He (Denzel Washington) is a black man in work clothes. As he attempts to discern calmly what has happened, a white guy from the truck in front of him gets out and begins yelling. The white guy, who is a redneck in a ball cap and a Harley Davidson t-shirt, believes he has been rear-ended by the blue van and immediately begins to berate the black man in front of a bunch of black people in what is obviously a black neighborhood. The van driver, though, tries to calm him down, first asking why he was stopped in the road and second informing the belligerent white guy that it was him who got hit from behind. The argument is going nowhere when a black police officer arrives and separates them. For comic relief, another white redneck in a straw cowboy hat and aviator sunglasses comes over from his wrecker and interjects, “Anybody here need a ride?” Amid all this – the cop has paid her no attention – Mina trades information with the van driver and seems to be leaving. Then the cop pays attention and calls after her, “I ain’t finished with you yet, young lady.” Mina turns and scowls.

In the next scene, we are at the Monte Cristo Motel. In a small hotel room, Mina’s father Jay is writing a letter and speaking its contents out loud. He is writing to the new government of Uganda to have his wealth and property restored. His wife Kinnu comes out of the bathroom and tells him to let it go, that years of writing these letters has yielded nothing. But his resolve is strong. He was born in Uganda and should not have been put out.

Their conversation is interrupted by a ruckus outside. A tow truck has brought Mina and the wrecked car back home. A whole cadre of Indian people emerge into the parking lot. The owner of the car is Anil, a young man who is about to get married. Jay looks over the car and tells him not to worry, and Anil launches into a diatribe, saying that Jay can’t even feed his family but is telling him not to worry. This make Mina angry, and she calls Anil a wanker— not exactly what a guy wants to hear from a woman who wrecked his car and has no money. Then, Anil’s friend adds to the tension, saying that Anil must worry now because all Americans like to sue by claiming whiplash. To relieve that tension, an older man Canti Napkin standing nearby asks for the business card of the van driver, saying to let him handle it.

After that scene, everyone is getting ready for Anil’s wedding. Mina comes into her parents’ room dressing in a traditional Indian outfit, and her mother checks her feet then chastises her about her slippers. Mina laughs it off, saying that she is a “darkie” and that no one will think much of her. Her mother, however, is not amused and sends her daughter to change shoes. After she leaves, Kinnu fusses at Jay for not being harder on their daughter, but Jay is not worried about it.

Our view of this community then shifts to black life in 1990s Greenwood. We see a group of young man and kids standing on a street corner, rapping and laughing as one young man emerges. He is stylishly dressed in bright colors and shorts with a heavy pan-African medallion-like necklace on. As they banter back and forth, the van driver from earlier, whose name is Demetrius, comes walking up, and he does not look happy. The stylish young man is alerted by his friends, and he looks downtrodden and goes over. Demetrius is coming once again to retrieve his lazy, ne’er-do-well younger brother from the streets. He chides the young man for not being at home when their father said to be, then asks him whether he went to the unemployment office. Yes, the young man says, but they have nothing for him and claim that veterans come first.

Though the story is clearly sympathetic to plight of the newcomers, the Indian immigrants, its telling does not go without giving some sympathy to the struggling black people as well. When the younger brother remarks that the employment people always have some excuse why they won’t help him, Demetrius replies angrily that, no, it’s him who always has an excuse! Here we see two responses to poverty and the lack of opportunity: one says that the system must do better in providing help, and the other says that people must help themselves.

In the next scene, we meet the young men’s father Willie Ben (Joe Seneca), who is a waiter in an old-school restaurant, the kind with tables in small nooks behind curtains. He is in a bow-tie and red jacket, rolling a cart with bussed dishes to an all-white clientele. As he is finishing, Demetrius has come to pick him up from work. He speaks to two white women at the counter, and the younger of the two explains after he walks away that her family talked to the bank for Demetrius to help him start his carpet cleaning business. In the kitchen, Willie Ben empties his tray of dirty glasses, then hangs up his red waiter’s coat. On the way out the door, he alludes to a woman who called – Alicia – and Demetrius is not pleased. Willie Ben told her she could come over to the house on Sunday. Judging from Demetrius’ reaction, she is an old girlfriend.

At the motel, it is Anil’s wedding. A traditional Indian ceremony and party are going on. As people mingle and children play, two middle-aged women are talking about a desirable young man named Harry Patel. One wants this young man to marry her daughter, but they acknowledge that he likes Mina. However, one assures the hopeful mother-in-law, that both skin-color prejudice and economic situation are working against Mina: one cannot be dark-skinned and poor and get a man like Harry Patel for a husband. They laugh, and the scene moves to Anil’s father, who leads the group in a sung prayer, yet Harry moves through the crowd and asks Mina to leave with him. She smiles and agrees, telling her mother that she is going. Yet, this scene isn’t over . . . Before they cut away, we see two white men in a small office, and one is on the phone reporting the loud gathering to the police. The older of the two says, when he hangs up the phone, “Send ’em all back to the reservation, that’s what I say.” But the younger man corrects him, “It ain’t that kind of Indian.”

Across town, Harry Patel and Mina are getting out of the car and going into a black club called The Leopard Lounge. Inside, a crowd of black people are dancing and drinking. Harry orders them two Michelobs, and young black woman who Mina knows comes up to say hello. She invites them to join the line dancing that’s going on, but Harry – still in his tux – is no dancer. Mina goes, however, and who is among those dancing? Demetrius. Mina speaks to him first, reminding him who she is, but all they can say is hello before Demetrius sees something he clearly doesn’t like. Across the room is a well-dressed and put-together woman standing with a Geri-curl guy who is equally dolled up. Demetrius goes over and hugs her, just as the DJ welcomes Alicia over the loudspeaker. Demetrius looks unhappy about the whole thing, and when Geri-curl guy says something about being her producer, we know: his old girlfriend is a singer who left him for bigger dreams. To make Alicia jealous then, he goes over and asks Mina to slow dance, and pulls her very close while he glares at Alicia. Frustrated by all this, Harry suggests to Mina that they leave, but Mina tells him that she will stay . . . He can go, if he wants to.

Across town, Harry Patel and Mina are getting out of the car and going into a black club called The Leopard Lounge. Inside, a crowd of black people are dancing and drinking. Harry orders them two Michelobs, and young black woman who Mina knows comes up to say hello. She invites them to join the line dancing that’s going on, but Harry – still in his tux – is no dancer. Mina goes, however, and who is among those dancing? Demetrius. Mina speaks to him first, reminding him who she is, but all they can say is hello before Demetrius sees something he clearly doesn’t like. Across the room is a well-dressed and put-together woman standing with a Geri-curl guy who is equally dolled up. Demetrius goes over and hugs her, just as the DJ welcomes Alicia over the loudspeaker. Demetrius looks unhappy about the whole thing, and when Geri-curl guy says something about being her producer, we know: his old girlfriend is a singer who left him for bigger dreams. To make Alicia jealous then, he goes over and asks Mina to slow dance, and pulls her very close while he glares at Alicia. Frustrated by all this, Harry suggests to Mina that they leave, but Mina tells him that she will stay . . . He can go, if he wants to.

Now, the story is all set up. Mina and Demetrius go to the bar, where Tyrone is hanging out. He is the T in D & T Carpet Cleaning. Tyrone is what we used to call back in the ’90s a “skeezer”— a guy who hits on every woman in such obvious ways that it’s clear that he only wants one thing. He gives Mina the once-over, looking her up and down, and tries a few lines. Demetrius tells Tyrone to cool it, though, and he drives Mina home.

Back at the motel, Anil is trying to get his sleeping bride to wake up and have sex, while the Indian dudes are all drunk. Napkin is trying to tell Mina’s dad Jay about money, and another guy there scoffs at Jay, saying that in Uganda he was a champion defender of blacks but then blacks put him out. Jay quietly accepts the mockery with a remark about color-blindness. Meanwhile, outside, Mina is sitting by the pool alone, and her mother comes outside. They talk about Mina’s interest in Harry Patel – she has none – but Mina wants to know why her father doesn’t write to his best old friend back in Uganda. Their conversation wanders among these topics, until it ends with no resolution.

The next morning, while they are getting ready to go to work, Tyrone wants to know why Demetrius didn’t sleep with Mina. Demetrius says that he has more on his mind than sex, and Tyrone fusses at him for being stuck on Alicia. The two take a minute to make fun of her Geri-curl boyfriend, then they load up with Willie and are off.

Over at the motel, Demetrius and Tyrone are cleaning carpets when Napkin shows up with tea. He stops them and initiates an awkward conversation about how black people are good at sports, but knows so little that he rattles off names of athletes who aren’t black. The two black men correct him, and he gets to the point: no matter, in America there are white people . . . and everyone else is colored. The two agree but don’t see where he is going. Napkin then weasels his way – smiling the whole time – into getting Demetrius to admit that there was no personal injury or vehicle damage in the previous day’s car wreck, and thus . . . no need to sue. Demetrius seemed bewildered but gets it now, since he had no such idea about suing anyway. Napkin, though, is pleased with his outcome and leaves the conversation saying that all non-white people have to stick together. The two black men laugh and agree, but it is clear that they are mocking his notion that he has pulled a clever move.

Soon, Mina calls the room that Demetrius is cleaning and interrupts his work. She thanks him for taking her home, but his retort is not what she expects: I’m not going to sue, he says. He thinks that her friendly call is to doubly ensure his cooperation, but he quickly realizes that that way of doing things isn’t her. Demetrius invites her over to his house for dinner on Sunday. She accepts, then returns to a Chinese lunch with her father. They talk about his desire for Mina to continue her education, but she reminds him they have no money. As an exiled lawyer, he is frustrated that his daughter is cleaning bathrooms. She is OK with it, she assures him, and adds that she will go to college later, after he wins his legal case and gets his money and property returned to him.

Jay is then walking through a poor black neighborhood to his wife’s liquor store. A bluesman named Skillet plays a quick tune as Jay walks in, then buys one can of Stroh’s beer and leaves. Alone, Jay and Kinnu talk, and Jay has a flashback to his childhood in Uganda and remembers his black friend fondly.

Across town, Mina is on the way to Demetrius’ house. Slide guitar plays in the background, and Demetrius is asking Mina questions about herself. He finds out that she has lived in Africa, England, and now Mississippi, and he is surprised to hear that she has never been to India. She tells him that she is like masala, the spice, though Demetrius has never heard of it. They arrive at the house, and Demetrius’ family is waiting on them. Willie Ben introduces himself, and Tyrone still has his eye on Mina. We find out that Tyrone has tried to go to LA to be an actor, but has come back home when it didn’t work out. We also find out that Willie Ben has invited Alicia, the old girlfriend from the bar, and Demetrius is not pleased. It is Willie Ben’s birthday, and his sister and Demetrius’ younger brother are there. The meal goes well, but the family has a lot to say to Mina . . . and a lot to ask her about herself. They are curious about her, about Indian people, and other related matters. Mina answers in a friendly and open way, and everything is going fine until Alicia arrives. Then Mina and Demetrius are out. From there, they go to stroll by the riverside and talk, and kiss.

This is the one-hour point in the film – halfway – and the story brings us back to the motel. Mina is working the front desk with Anil’s father who owns the motel. He can tell that something is make her smile, and he is trying to figure out what it is, then a series of customers come through. An old Chinese man comes in smiling, turns in a room key, and remarks when asked how many times he did it, “Chinese don’t do no hanky-panky.” Then a fat white guy in a plaid sport coat comes in with a sassy young woman, but he is nervous and haggles over the rate while his side girl pinches and rubs him. Finally, Demetrius ambles in, whispering to Mina about Biloxi as she tries to cover up the fact that she knows him. Ultimately, Demetrius leaves still pleading in whispers and gestures for her to go with him, and the old Indian guy leaves it with Mina so he can go to bed. Sadly, of all the people who are getting some love, Anil is shown once more being rejected by his wife. (We get from this that, in traditional Indian culture, marriage is an arrangement that has nothing to do with love or sex.)

Later, on the phone, Mina and Demetrius concoct a plan for her to meet him in Biloxi, which is about 250 miles south on the coast. In the scenes that follow, the multiple plot lines begin to converge. Anil gets his car back from the repair shop after the wreck, and he and a few others agree to take it on the road for a test drive to see a friend’s new motel. Next, we see Mina behind the motel counter, and a letter arrives for her father. Jay rushes in and is reading it, as she asks if she can go to the beach with a female friend and come back tomorrow. Preoccupied, her father says yes, then continues reading. We know that Mina is actually going to meet Demetrius so they can be out of their own community’s sight. A voiceover then relays the contents of the letter: Jay’s letters of inquiries about his property and assets have been considered, and his case will be heard by a Ugandan court, but he must appear in person.

Down in Biloxi, things get much better then much worse. Mina gets off the bus, and Demetrius is waiting there. They get to talk about their lives, about the South, and about race. But before they get to the motel to spend the night together, they are on the big Ferris wheel and are spotted. Anil, Napkin, and their friend are playing mini-golf below, and the skinny friend with the mullet recognizes them. The two lovers don’t see the three men, however, and thus move on to their night of passion— which is interrupted in the morning when the friend sees Demetrius’ van outside a beach motel. The three Indian men go to confront Mina and Demetrius, with Anil charging in first in an attempt to attack Demetrius. Anil gets his butt kicked, and the friend runs for help. When he arrives back with the police, Demetrius is taking care of Napkin next. Seeing only that Demetrius is the aggressor, the cops arrest him and Mina both.

The scene skips to the police station, where first we see Mina escorted out and given over to father and Napkin, while Demetrius is released to Tyrone. Mina’s expression is defiant and hurt, and Jay receives her silently and with seeming compassion. Tyrone, on the other hand, reprimands his friend, telling him he should know better and to “leave them fucking foreigners alone.” While Demetrius sits silently in the passenger seat, Tyrone also recalls Napkin’s quasi-friendly speech about “united we stand, divided we fall,” which foretold some kind of solidarity between them. “But if you fall in bed with one of their daughters, you gon’ swing.”

Meanwhile, Mina is tearfully confronting her parents about her predicament. She is 24 years old and is stuck with them like she is still a child. Her mother pleads with her to embrace traditional Indian values about family and marriage, but Mina retorts that this is America. She loves Demetrius, and that’s all that matters. Her father scolds her for not being sorry about what she has done, but she is not sorry. To drive this point home, in the scene that follows, we see other Indian women only phone gossiping about Mina’s faux pas, as they gloat and enjoy her problems. One woman asks the other, “Can imagine turning down Harry Patel for a black?” Mina can, but they cannot.

A montage then shows the array of opinions to be held on this interracial love affair and its apparent end. Demetrius tries to call the motel to ask for Mina, but Anil – who has two black eyes and a busted nose – hangs up on him. The white racist we heard earlier confusing Indians with Native Americans has a good chuckle as he asks, “What’s a matter, y’all having nigger trouble?” The white woman who we saw earlier in the film, the owner of the restaurant where Willie Ben works, is telling someone that she will call the bank about Demetrius’s loan. Napkin is there too, explaining that he has already hired another carpet cleaner. Even the ex-girlfriend Alicia chimes in, claiming the Demetrius has betrayed his race. A man from the Chamber of Commerce even says in vague terms that Demetrius will be losing their support, too. The last diatribe comes from Willie Ben, who is concerned about his own job since his boss connected Demetrius to the bank. However, his sister chides him, saying that the days of slavery are over and that Willie Ben shouldn’t be OK with how these white people control their family.

Ultimately, Demetrius must go do something about it. His brash younger brother tries to be supportive, but he is so foolish and inept in his attempt that Demetrius brushes him off. Down at the bank, the man tells Demetrius and Tyrone that part of having a loan from them means exhibiting good character—which is total bullshit and they know it. But the end result is the same: The Man has decided to pull the plug. On the way out, Demetrius laments, “Character, Collateral. Capital. Color is the one they left out.” As one final blow, Tyrone then tells Demetrius that he’s not going to stick out with him. Tyrone is heading for LA to try is luck there again.

Out of options, Demetrius walks into the motel and asks to see Mina. Instead, Anil’s father at the front desk calls Jay. Confused, Demetrius follows Jay outside, and the elder man tells him that he has caused enough trouble. So, Demetrius is left to confront Jay about his racism, which he perceives as the source of the problem. Jay tries to implore the would-be suitor that he too once believed that he could challenge the world’s ways and be different, but now he just wants protect his only child from the realities of a cruel world. Demetrius is defiant though, saying that people like Jay come down to Mississippi, and though they are only a shade or two lighter than him, they immediately begin acting white, trying to treat black people like they are less-than. Jay is shocked by the accusation and is left speechless as Demetrius walks away. Jay is then left to remember his last night in Uganda, when he had to face race prejudice in such a severe situation.

In the next scene, Jay is trying to explain to Mina why he is taking this stance against Demetrius. He tells her that his old friend in Uganda told him that “African is for Africans, black Africans,” and that it all came down to the color this skin. He learned the harsh lesson that people stick to their own kind. Mina, however, disagrees and says that his friend did not feel that way. She reminds him that, when they left he came to say goodbye to Jay and his family, but Jay wouldn’t even look at him. It was Jay who interpreted the situation the way he did.

To ratchet up the pressure, Demetrius decides to hire a lawyer after all. We see a white guy in a a suit and a big cowboy hat encouraging Anil to settle out of court. Jay is there to help him, calling the bluff and soothing Anil. Yet, Anil is having none of it. He tells Jay that he and his family must leave, that he has had enough of the trouble they cause. Jay announces first to his daughter then to his wife that they are heading back to Uganda.

In the film’s final twenty minutes, Jay and his family are packing to leave. But Mina sneaks away and makes yet another brash move, stealing Anil’s car. She goes to see Willie Ben at the restaurant. He is irritated by her coming to his workplace, and he tells her exactly what Jay told Demetrius, You’ve caused enough trouble for us, so go away. She wants to talk to Demetrius, to say goodbye, since they are leaving for Africa. Reluctantly, Willie Ben tells her that he is trying to drum up carpet cleaning work with motels in Indianola. She speeds over there and soon finds him, but he refuses to speak to her. Something of car chase ensues, and eventually Demetrius pulls over on a rural road. At first, there is tension between them, but they reconcile through conversation when she convinces him that she wants to stay in Mississippi with him rather than go back to Africa with her family. They both make difficult phone calls, explaining this fact to their respective families. Demetrius tells Willie Ben that he will have to fend off the bank, because he does not intend to give it back to the repo man.

The final scenes have Jay and Kinnu back in Africa. Although he wanted to make amends, Jay finds out that his old friend is dead. The movie ends in a celebratory street scene, where people dance and where an African child climbs into Jay’s arms lovingly. We get the symbolism: love and humanity have triumphed over racism in Africa.

What makes Mississippi Masala particularly interesting are its two predominant messages that Southern black people are prejudiced – and possibly even racist – against Indian immigrants, and that the Indian immigrants who feel the effects of that prejudice have their own way of dealing out prejudice: skin color, social class, marriageability, assimilation, ethnic solidarity. In this complex mixture, Mina’s family has left a place where black people conducted an aggressive campaign to purge non-blacks and purify their homeland and their culture . . . and the family has arrived in a place where black people are on the receiving end of race prejudice from white people, while also naively regarding Africa as a place where race prejudice is not a problem. Further adding to the complexity is a blurry line that is evidenced by Napkin’s talk with Demetrius and Tyrone about the car wreck: the Indians want to team up with black people as “people of color” while also maintaining a separate cultural identity that sets them apart from black people. This approach by the Indian immigrants is a convenient and manipulative way to minimize their own victimization by appealing to Southern black people’s sense of victimization. Meanwhile, local black people, who are grounded and well-versed in trickery and double-talk, do not regard these newcomers in any way that would indicate solidarity.

So, Mina and Demetrius are both interlopers in each other’s culture. On each side of this different and unique color line, we have various symbolic caricatures. Mina’s father Jay is the worldly and enlightened man who recognizes his predicament, while his wife Kinnu is the voice of India’s traditions in a new world. Demetrius’ father Willie Ben is the wise elder who embraces life in a realistic but loving way, while Tyrone is an unreliable friend who sexualizes Mina. Demetrius represents the hard-working bootstrapper in the Southern black community, while his brother shows us the young man who is unwilling to work or accept responsibility, preferring instead to complain and blame. Anil and the other money-conscious Indians show us the inner workings of a group that has come to a place where they do not fit in, yet try to make their way. And by crossing from one world to another, our main characters find their romantic relationship to be difficult due to the lack of acceptance on both sides.

As a document of the South, Mississippi Masala shows us more than the same old black-white paradigm. We do see a handful of white racists appearing as minor characters, but this story encourages us to think about a multicultural South. During the car ride to Demetrius house on their first date, Mina explains that she has lived in Africa, England, and now America, and so she is like masala, a spice used in Indian food. This analogy encourages us to consider Indian immigrants, who we may not think of as Southerners, but we can also extend that to the “Mississippi Chinese” or the Hispanic people believed to have introduced one of Mississippi’s well-known food traditions, tamales! It also asks us to consider that race prejudice in the South is not just simply a one-way street running from whites toward blacks, and that prejudice is multidimensional and involves issues of nativity, social class, family structure, and religion as well as race. Ultimately, Mina and Demetrius find that their relationship cannot continue in Greenwood, because of the cultural pressures on them both. They don’t know where they will go, as the movie ends— they just know they can’t stay where they are. This ending is particularly pessimistic considering that Jay wins his right to have his case heard in Uganda and returns there with some hope of redemption . . . while in the South, Mina and Demetrius have no idea where to turn, only knowing that the South will never allow them to have the relationship that they want.