Foster Dickson's Blog, page 12

September 21, 2023

The end of “level:deepsouth”

It was a good idea from the start, which made this a hard decision. In December 2023, level:deepsouth will close up shop and go offline. The project is now in a read-only format. Submissions are no longer being accepted.

For me, level:deepsouth was always about publishing stories from Generation X in the South and sharing them with readers, not about making money or establishing a business. “Open source” – to borrow a term – is a tough model, since it doesn’t prioritize the revenue that would sustain the project. That approach to the project meant that submissions were always more important to me than dollars. However, over its first three years, from March 2020 through March 2023, submissions became harder and harder to come by. I had tried in various ways and through various avenues to attract submissions, but for whatever reasons, those efforts have yielded less fruit than I’d hoped. I bought Facebook ads and NewPages ads, and those led to clicks on the “submit” page, but few queries and submissions. In my mind, a project like this one would only thrive and become meaningful through the steady publication of first-person stories. Unfortunately, by this last summer, I had to face the sad fact that that too few of those were coming in.

For me, level:deepsouth was always about publishing stories from Generation X in the South and sharing them with readers, not about making money or establishing a business. “Open source” – to borrow a term – is a tough model, since it doesn’t prioritize the revenue that would sustain the project. That approach to the project meant that submissions were always more important to me than dollars. However, over its first three years, from March 2020 through March 2023, submissions became harder and harder to come by. I had tried in various ways and through various avenues to attract submissions, but for whatever reasons, those efforts have yielded less fruit than I’d hoped. I bought Facebook ads and NewPages ads, and those led to clicks on the “submit” page, but few queries and submissions. In my mind, a project like this one would only thrive and become meaningful through the steady publication of first-person stories. Unfortunately, by this last summer, I had to face the sad fact that that too few of those were coming in.

Knowing that, I had to give some thought to the idea of paying contributors, which would inevitably attract more writers. But there just wasn’t money for that. I have funded the project myself and have looked into other funding sources – grants, GoFundMe, institutional support, etc. – but haven’t found any viable routes to take. level:deepsouth is not at all unique in being a non-paying literary publication. One way that it is unique, however: most non-paying, independently edited publications last about a year to a year-and-a-half. level:deepsouth lasted almost four years— three times the average. Beside that, it offered writers more than a one-issue presence.

While I am proud of every work that was published in the anthology, my decision to close the project is prompted by what I have not been able to procure as an editor. level:deepsouth contains strong works that serve the project’s goal, but as a whole, a certain diversity of experiences from Generation X in the South is still lacking. Last March, at the three-year anniversary, I set and pursued a goal to publish a healthy number of new stories by first-time contributors. I have would have been glad to see queries from any Southern state, but particularly glad about stories from Arkansas, Mississippi, or South Carolina. Those states had no representation in the anthology at all. Equally interesting would be submissions about growing up in east Texas, Louisiana, or North Carolina, states that have one contribution each. Another striking deficiency that I tried to remedy but can’t explain is that no submissions by writers of color were ever sent in. Despite efforts to include these experiences, to achieve a fuller representation, and to fill the gaps, the works necessary to do that did not come in. After more than three years, I am accepting that I probably won’t be able to accomplish this goal (especially without funding for author payments).

My ultimate standard for whether to close the project or not was: if the anthology in its current form came across an acquisitions editor’s desk as a manuscript, would that editor say yes to publishing it? I had to admit that, as a whole, the project’s strengths are real and significant, but its incompleteness is inarguable. As the project’s editor, then, I would have to remedy that for it to be viable. Yet, if I don’t how to remedy the problems; otherwise, I would have kept the project going as a work-in-progress. An editor can keeping seeking, requesting, and soliciting works, but if the writers don’t send them . . .

I still believe that a substantial compilation of nonfiction essays from GenXers who grew up in the South is a worthy project. To be candid: before I ever created level:deepsouth, I pitched the subject as a manuscript proposal to a couple of publishing houses, only to be told that they didn’t believe that there is public interest in such a work. I also pitched it on a two different fellowship applications as the project to be undertaken, and those weren’t approved either. In creating level:deepsouth, I took the bull by the horns and moved forward with what I did have: editorial skill, basic web skills, a personal knowledge of the subject matter, a few bucks of my own. But that hasn’t been enough to carry it all the way to where it needs to be.

Ultimately, much of the content that I produced for the project will migrate here: a few blog posts, two reviews, one essay, and all of the content in “the lists.” That last one will be published here on four pages titled GenX in the South: A Bibliography, A Discography (Plus), A Videography, and Random Stuff.

September 17, 2023

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week 205

Ludie Gutshall: Now, how come you make all the decisions and I end up taking all the risk?

Pap Gutshall: Because this time it’s a question of principles.

Ludie: Well, with me it’s a question of scruples.

Pap: What kind of scruple?

Ludie: Bad. You know how it is with scruples, Pap. Hell, you probably got as many scruples as I do.

Pap: I don’t think this here falls under the category of scruples. It leans more from your basic scruples to your basic principles. And my basic principles is that you and me and . . . all the rest of us . . . ought to do something to help that girl?

Ludie: You know what my basic scruple is?

Pap: What?

Ludie: Not to get my ass shot off for your basic principle!

— from the 1973 film adaptation Lolly Madonna XXX, based on the novel The Lolly Madonna War by Sue Grafton

Read more: The QuotesSeptember 14, 2023

September 10, 2023

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week 204

Wretches find comfort in fellow sufferers.

— spoken by the character Mephistopheles in the 1967 film adaptation of Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus

Read more: The QuotesSeptember 7, 2023

Southern Movie 65: “Nothing but a Man” (1964)

Set in small-town Alabama in 1963, the black-and-white drama Nothing But a Man shows the trials and tribulations of a black couple trying to lead a quiet, humble life. The man is a railroad worker who leaves his good-paying job to get married, and woman is a schoolteacher and a preacher’s daughter. In a 1993 review written when the film was re-released, Roger Ebert called it “more famous than familiar,” and remarked that “today there are few people who have seen it.” The story is bleak and stark, and the realism within the style suits the story. The main characters live in a culture that offers them little decency or dignity. It belittles and denigrates them and everyone around them. The plot and conflict center on their efforts to overcome that and live like decent, hard-working people. Directed by Michael Roemer and starring Ivan Dixon and Abbey Lincoln, Nothing But a Man also features Yaphet Kotto, Julius Harris, and some real-deal down-home gospel— as well as the Motown sounds of Stevie Wonder, The Miracles, and Martha and the Vandellas.

As the opening credits go up, we see a small group of men working on section of railroad. The old man in the crane is white, and the men on the ground swinging hammers are black. Our main character Duff (Ivan Dixon) is operating a jackhammer that buries the spikes other men put in place. After the work day is done, they are all back in the train car where they bunk. Duff is beating a man named Frankie in checkers, while another man named Jocko (Yaphet Kotto) is nearby shaving. Frankie is jovial and smiley, while Jocko is sullen and serious. Most of the men are silent as they either play cards or rest in their bunks.

Later, after they’ve gotten cleaned up, they take a small flatbed railcar into town. They pass by industrial squalor and rural poverty, but their moods are not sour. They’re going to have a good time. In the bar, some men drink beers and play pool. Jocko plays pinball. A prostitute named Doris comes over, and Frankie harasses her. Duff buys her a beer then pays and leaves. Doris offers to leave with him but he says no.

Out in the streets, it is quiet, then Duff comes upon a church with a vigorous service going on. Preacher is preaching, women are singing. He moves through the sanctuary and out back where food is being served. There, he sees a pretty young woman who gives him a shy smile. This is Josie (Abbey Lincoln), and they start out toward falling in love. In a brief conversation, Duff explains that he works on the “section gang,” and he finds out that she is teacher. For a moment, his face goes sullen, probably knowing that she is out of his league, but he stays and keeps talking. He finds out that she went to college in Birmingham, which is his hometown. She asks if he has family there, and he replies, “Nope, my mother’s dead.” (This, implying that he had no father in his life, which will come up later.) At the end of the conversation, he asks if she’s going back inside to the church service. She is, but he isn’t. He has never had much use for religion. By contrast, her father is the preacher. Before leaving, Duff takes a long, pensive look at the church folk then he walks out into the night.

In the next scene, we see the men in their train-car bunkhouse after another day at work. Everyone else is relaxing, but Duff is cleaned up and heading out. He asks to borrow another man’s car, and Frankie chides him for messing around with a hometown church girl like Josie. Why waste your time, he wonders out loud. One older man declares with a half-smile, “All a colored woman wants is your money.” But Duff isn’t hearing it. Jocko offers the advice that he should just get her drunk, but that gets no response either.

At Josie’s house, she is sitting at the dinner table with her parents. The household is very different from the train car where Duff lives. It is clean and crisp, giving off an air of middle-class respectability. Her father sits at the head of the table in a suit and tie. We find out in the short conversation that Josie’s parents don’t approve of her going out with Duff, but she reminds them that she is twenty-six years old. Just then, the doorbell rings.

The couple goes out to the club, where Motown is blasting and people are dancing. Duff is having a good time with Josie, then Jocko and Frankie show up to heckle him a bit. They leave and go sit in the car on a quiet road, but two white guys show up to cause problems. Duff tries to stand up for himself, but he is outnumbered and this is the South, after all. It is scary for a moment, and Duff and Josie wonder what these two rednecks will do. Then one of them recognizes Josie as a preacher’s daughter and says to his friend that they should move on. Here, we see the dangers that black people face. As the end of the scene comes, Duff remarks, “They don’t seem human, do they?”

On the ride home, Duff wants to know why Josie stays in the little town. It makes no sense to him. Josie replies that it’s better than it used to be, then tells him about a lynching eight years earlier. Her father knew who had done it, and we understand from her simple statement that there was nothing he could do about it. At the house, Josie tells Duff that she does want to see him again. Duff doesn’t see where it goes from here, but he still seems amenable. His objection is: what do we do next, “hit the hay” or get married? He brings it out into the open that she isn’t going to want to sleep with him, and he isn’t willing to get married (and leave his traveling job). All Josie can say to him is: “You’ve got some primitive ideas, don’t you?” Before getting out of the car, she tells him that most men she knows seem sad but Duff doesn’t and that’s why she went out with him.

Back in their daily lives, we next see Duff and his pals beating rabbits out of the tall grass so they can roast them, while Josie is teaching in a one-room schoolhouse. Outside, she sees Duff and dismisses her students. They talk on the swing set for a moment about how Duff was in the Army and how he lived up North for a bit. But it wasn’t much better anywhere else, so he figured he’d come back to Alabama. The couple runs through the rain to Josie’s house, and when they scurry in, a white man in a suit and tie is standing with Josie’s father. They straighten up but the man only smiles. It is Mr. Johnson, the school superintendent. Josie then introduces Duff to her father, who extends his hand for a handshake, then to Mr. Johnson, who smiles and nods— no handshake from the white man. We then learn from a brief interchange why Mr. Johnson has come to their home. He first comments to Duff, “Watch your step, boy” about dating Josie, then turns to the preacher and reminds him that it’s no time for “your people” to sue. (He is referring to Civil Rights and school integration, of course.) The conversation that we do see is a veiled reference summarizing the one that we did not see, which occurred before Duff and Josie arrived: a seemingly friendly but not actually friendly chat between a white leader and a black preacher about how the latter man should fend off Civil Rights action before it starts. What is important to remember, with Birmingham being referenced and with the year being 1963, that this is the time and place of the Birmingham church bombings, the Children’s March, and Bull Connor.

The conversation that follows is between the old preacher and the young rambling man. It is clear that Duff is nervous, while the elder man is very calm. He starts by saying that it’s hard to know how to talk to white people now, in these changing times, and Duff retorts that it has never been easy. Apparently, the deal has been made for a new black school, but Duff wants to know why the town isn’t integrating. The preacher tells that there has been no trouble in eight years – he calls a lynching “trouble” – and vows not to let there be anymore. Duff reminds him that you can’t live without trouble. So, the preacher changes the subject and asks Duff if he attends church. Duff tells him no, that the black folks spend more time in church when the white folks are the ones who clearly need to. The conservative preacher has now heard all he wants hear and rises from his chair to say they have nothing else to talk about. And one more thing, he says, stay away from my daughter. Duff says that it figures, and then stands to say that here it’s just like it is everywhere else.

At this point, the film is nearing one-third of the way through. Though he seems to be a good guy, Duff is an interloper. He is free of obligations and only has to take care of himself. By contrast, the black people who live in the town must be careful, as we’ve seen from the two rednecks who came up to their car and from the smiling superintendent who calls Duff “boy.” We’ve got a free-spirited man who has to make a choice: will he continue down the road he is on, or will he marry Josie and try to live a settled life? Out on the porch, Duff and Josie have their heart-to-heart talk. Amid the discussion, Duff tells her that he is going to Birmingham the next day to see his child. Josie didn’t know that he had one and asks if he is married. No, he isn’t married. After the talk with her dad and now this, he’s pretty sure that’s over.

At this point, the film is nearing one-third of the way through. Though he seems to be a good guy, Duff is an interloper. He is free of obligations and only has to take care of himself. By contrast, the black people who live in the town must be careful, as we’ve seen from the two rednecks who came up to their car and from the smiling superintendent who calls Duff “boy.” We’ve got a free-spirited man who has to make a choice: will he continue down the road he is on, or will he marry Josie and try to live a settled life? Out on the porch, Duff and Josie have their heart-to-heart talk. Amid the discussion, Duff tells her that he is going to Birmingham the next day to see his child. Josie didn’t know that he had one and asks if he is married. No, he isn’t married. After the talk with her dad and now this, he’s pretty sure that’s over.

The following day, there is Josie on the bus, claiming jokingly that it is a coincidence that she is heading to Birmingham, too. She wants to know how old Duff’s son is. He is four, and Duff hasn’t seen him in a few years. When they arrive, Duff is walking down a crowded street and finds a woman in a poor apartment. She doesn’t know who he is, and he has to tell her. She looks sad and angry and tells him that it’s about time he showed up. The child’s mother got married and left for Detroit, not wanting to take the child with her. The woman and several small children are living in squalor in a two-room apartment. Once Duff is taken back to see his son, the boy won’t really look at him. The scene is awkward and sad, but it gets sadder when the woman tells Duff that his father has been seen around town. Duff knows nothing of him and asks a few questions. We see here a cycle of poverty and absent fathers— Duff’s father abandoned him, and now Duff is not around for his son’s childhood.

He leaves the apartment – without his child, but promising to send money to this random woman who he doesn’t know and who states openly that she has no interest in raising the boy – and goes looking for his own father. Duff finds him living in a one-room apartment, also in dire poverty. The father Will Anderson (Julius Harris) does not know his son to lay eyes on him, but he does welcome him in. Will appears middle-aged, he drinks heavily straight from a pint of whiskey, and he has one lame arm that just hangs. Duff asks about the arm, and Will tells him that he injured it in a sawmill accident. Just then a woman comes in. Her name is Lee. She could be an attractive woman, but instead she looks tired and angry. She appears indifferent to the fact that Will’s son has come to see him and offers them both some coffee.

This is where the plot gets thick. There would be enough to explore in trying to tell a love story between a local woman and a traveling man, both black in Jim Crow-era Alabama— a railroad man and a preacher’s daughter. But here the film adds another layer. Duff’s alcoholic father, who he hasn’t seen enough times to be sure that it’s actually him, is so beaten down by life that he is alternately pathetic and cruel. An astute viewer will recognize that Duff has just met his own son, who didn’t know him either, and those parallels will play out later. Now, Duff has three people who he must either reconcile into his life or abandon – a woman, a father, and a son – and to become whole, he must face what each one means to his own life. An astute viewer will also recognize that these are aspects of the story that fit with the title: Nothing but a Man. We now have seen several facts of life for black men in the segregated South as well as their ways of handling them: the men in the railroad car embrace their high isolation and relatively high pay, the preacher embraces caution and safety to maintain his comfortable life, the old crippled man embraces drunkenness to deal with his sorrows. As Duff navigates these different worlds, he is encouraged by each type of man to embrace their worldview, and Duff must decide what to do.

Duff’s encounter with his father and Lee is tense. First, they drink coffee in the small apartment, and during the conversation, Duff finds out that his father has health problems. Then they go to a nearby bar. Will is openly cruel to Lee while they are there, telling Duff that she used to have sex with the white man whose house she cleaned. Lee is clearly embarrassed, and we see Duff’s jaw muscles clench as he grits his teeth. Will also tells his son – right after he was just explaining how Lee has taken care of him and how he hasn’t worked in months – to avoid marriage because it’s no good and only ties a man down. There is also a certain sexual tension between Lee and Duff, which Will seems to recognize and almost encourage. It grows a bit stronger when Will leaves to go the restroom, as Lee and Duff dance to a song that’s playing. When Will returns, he is drunk enough to insist that Duff has to leave, that he is unwanted.

After walking through the Birmingham night, Duff is back in the bus station to meet Josie and ride home. She comes in, smiling. She is wearing white gloves and is demure and proper, a stark contrast to Will and Lee. (The scene is a bit problematic because this black couple walks right in, sits down at the counter, and orders coffee; we see white people walking around in the background as though everything is normal. In that place and time, Birmingham in 1963, that wouldn’t be normal.) Then, almost immediately, Will does exactly what his father said not to do: he asks Josie to marry him. The scene is a mixture of happiness and tension as they converse about what that could mean. Josey wants to know about the woman who is his son’s mother, and he assures her that all that is in the past. Ultimately, she agrees coyly.

Back in the railroad car, the fellas think Duff is making a mistake. Frankie has no idea why he would do such a thing. Jocko assumes that Duff has gotten her pregnant. Here is the first kind of pressure that Duff will face: don’t do it, man!

Next we see, Duff and Josey are riding over to look at a small house they will move into. It is dilapidated and full of some family’s past life. Josey tells Duff that she knew the people, they went North. Duff looks around at the mess and says, “I can see why.” Over next door is another family with a bunch of kids running around. Josey knows them, the husband works at the mill. Duff asks, “I guess you’ll want a house full of pickaninnies, too.” She smiles a bit but says, “Don’t call them that.” They both remain good-natured until Josey suggests that Duff’s son could come live with them. Duff prefers to see how they get along first.

Only the beginning of their wedding is shown. Frankie and Jocko are there. Josey looks pretty in her white dress, and Duff looks pleased. Josey’s father, who is presiding, does not look pleased at all. At this point in the movie, it is half-over— forty-five minutes into a ninety-minute runtime. Duff has made his choice and will settle down, in defiance of his friends’ advice and of his father’s advice, and as it relates to his now-father-in-law’s position on the relationship, in defiance of him too. To use two old clichés at once, Duff is swimming upstream in shark-infested waters. He has only Josey on his side.

After the wedding, we see Duff heading to work at the sawmill. Josey is still in bed. They both look happy. A carload full of men pick up Duff for work, and they joke and cut up a bit on their way. On the job, Duff is singled out by a white man on a forklift, probably a foreman, and Duff has little to say to him. At first, Duff does not even respond, being called first “Jack” then “boy.” After working a while, the black men are at lunch and goofy-looking white guy sits in their midst. He is talking about sex with black women, addressing Duff directly by remarking that his new wife is “the best looking colored girl in town.” Duff is obviously displeased but stays silent, and the white guy asks, “What’s the matter?” Ultimately he keeps pushing Duff then walks away when he gains no ground, but only after making sure that Duff sees how he can make the other black men yield. After the white guy is gone, the other black men comment to Duff in various ways that he’d better learn to give in to this kind of taunting and degradation. Duff responds that if they all stuck together the whites wouldn’t get away it. “Like hell they wouldn’t,” one black man responds as he walks off. As the men disperse, it is clear that Duff is causing trouble, and his co-workers don’t want any.

The next few scenes show Duff and Josey happy at home. First, they are eating in the kitchen, then hanging up laundry. Then they are in bed. Josey remarks that she is very happy, and Duff replies that he is, too. After that, the railroad guys have come to their house for dinner. They finish up, and Duff walks them out. The crew is leaving town, different ones going different places from there, and this would be Duff’s last chance to join back in. He politely refuses, and the men wander into the night, heading back to their lonely train car. In the last of this succession of scenes, we find out that Josey is pregnant. They are cautiously optimistic about it. During that conversation, Josey asks again about Duff’s son, and he gets irritated, saying, “He ain’t mine. So just forget about it.”

But that happiness won’t last. Back at work, a white supervisor comes into the locker room at the sawmill and confronts Duff. The supervisor wants to know if Duff is a “union man.” Duff replies that he was when was on the railroad. When the white supervisor asks Duff what he meant by “sticking together,” Duff knows that the other men have ratted him out. Most won’t look at him, and a few that do show shame and fear. The black man who called him “trouble” is smirking during the interaction. Finally, the supervisor tells Duff that, if he isn’t trying to organize them into a union, then all he has to do is say, in front of his co-workers, that he didn’t mean what he said about “sticking together.” Duff refuses, and he loses his job.

But he has his dignity – Duff wouldn’t let the men at the sawmill take that away – and he also has a pregnant wife, so he has to hit the streets and find a job. It doesn’t go well. The first job he applies for looks like it will work out, until the hiring manager finds out about his recent actions at his last job. Here and there, one man says, “I already got a boy,” and another offers pay so low that it’s insulting. During these scenes, one of his old co-workers from the sawmill sits down next to him at a cafe, telling Duff that it was only one man who “talked” and that in hindsight the man shouldn’t have. But that doesn’t help or change anything. Duff then has to swallow his pride and ask Josey for any money she has, to fix the car so he can keep looking for jobs. She gives him her last few dollars, and he heads out to find work picking cotton. It is obvious that this is the lowest of the low when it comes to jobs. The white foreman announces that he will only hire a limited number of them, and his pay rate is sparse. Duff turns and walks away during this speech and does not even attempt to get one of those few jobs.

Back at home, Duff is really irritable. He was a just a little bit irritated when he lost the sawmill job, but now he’s full-on pissed off. They’re out on the porch and Duff is trying to fix chair, knowing the leg back into place. Josey is trying to assure him and give him hope, but that just makes Duff angrier, and he smashes the chair.

If that wasn’t enough, Duff has to talk to his father-in-law, who seems in some way to be enjoying the young man’s problems. The older preacher tells Duff to “use psychology” and “make them think you’re going along until you get what you want.” Duff replies, “It ain’t in me.” That’s not what his father-in-law wants to hear. He suggests that Duff take his wife and go North, but Duff isn’t interested. The preacher begins to get frustrated, continually calling Duff “boy,” and tries to impress upon him that he just doesn’t get it. Duff calmly retorts that the elder man has been cowing down so long that he doesn’t even know how to stand up for himself. He calls his father-in-law “half a man.” While we are watching this, we see interspersed cuts to Josey in the kitchen; she has broken a dish and is crying. The scene ends with the preacher offering one last thing: he knows a man who owns a filling station, and maybe Duff could work there. After the preacher leaves, Duff and Josey talk. Duff wants to know why Josey doesn’t “hate their guts.” Josey remains her usual calm self and says she is only afraid of being hurt, because “they can’t hurt me inside.” Duff responds, “Like hell they can’t. They can reach right in with their damn white hands and turn you off and on.” Josey remains hopeful however and says, “Not if you see them for what they are.” This really pisses Duff off, and it is visible in his face. He tells his wife, “You have never really been a n****r, have you, living in your father’s house? So just shut your mouth.”

Here, entering the film’s last twenty minutes, nothing is going well. It looks like Duff’s decision to quit the railroad and marry Josey will be a disaster. What we see, which is perhaps most important, is: in mainstream Southern culture, a black man cannot have dignity and expect to earn a living. An equally important message is: if a black man expects cooperation in his pursuit of a dignified life, he shouldn’t expect that, not even from other black men who are experiencing the same things.

This is where Duff goes off the rails. Up to this point, he has been an admirable character, but he is being tested to his limits. At the service station, his job is menial, and his boss Bud Ellis is not friendly. A call comes in that a man has hit a tree in his car, and Bud Ellis sends him with the tow truck. Duff goes out on a rural road and finds the white man who called. The man tries to be friendly but is getting in the way as Duff hooks up his car. Duff snaps at him, and the white driver doesn’t like it but also doesn’t have much choice. Later, who pulls up at the service station but the wise guy from the sawmill. He has a carload full of white men, the offended white driver among them, and he begins harassing Duff with smart remarks. The wise guy is there to avenge the slight that his weaker friend will not speak up about. Then when Duff gets aggravated, Bud Ellis comes out to see what’s going on. Duff gets fired again.

Then Duff snaps. He comes home to Josey who already knows that he has lost his job. She tries to console him again but Duff throws his wife on the floor. He grumbles angrily that he never should have married her. He then packs his suitcase and leaves, with Josey lying in the bed helpless against his anger. He returns to Birmingham and finds his father delirious from liquor and untreated high blood pressure. Lee cannot help him, and Will tries to drink his way through the suffering but he can’t even do that. They put Will in the car and try to rush him to get medical care, but he dies in the back seat with his head in Lee’s lap. At the funeral home, Duff realizes, through the undertaker’s questions, that he knows nothing about his father, not his age nor where was he born. After a funeral that we don’t see, he and Lee part, and we sense that this will mean relief for Lee. In the movie’s final scenes, after Duff has refused Lee’s offer to come and live with her, we see Duff return to the row houses where his son is. He carries the sleeping boy in his arms and puts him in the car. They return home to Josey, and Duff makes up with her. We know from this point that, though his life will still be hard, he will not follow in his father’s footsteps down a path of rootlessness, despair, and temporary comforts. He will embrace the people he loves and do his best.

Nothing But a Man is a brilliant film for more than one reason. Primarily, it spoke hard truths in a plain style at a time when such truths were not well-received. In that respect, the film may have been – as they say – before its time. The effects of racism and poverty are seen and felt in vivid, unvarnished detail. Second, the film does not try to make cardboard heroes out of its protagonist or his supporting cast. Duff is a good man who is doing his best, but his behavior is not always admirable. Likewise, we see the struggles of two black fathers – Duff’s and Josie’s – and the vastly different ways that each man deals with a life hampered by inequality and injustice, and in that context, we can see Duff’s struggles to be a father. Third, we see black women represented sympathetically, not as simple love interests but as human beings who suffer, too, in their own ways— Josie, Lee, the nameless woman looking after Duff’s son. Fourth, we see white supremacy and racism in multiple forms and not reduced to the stereotypes. There are the two young men who intend to terrorize a black couple who are parked and talking, and we see the condescension of the well-to-do Mr. Johnson who is there to use the black community’s preacher to do his own will.

Another brilliant aspect of this film is its focus on the effects of Southern racism and of Jim Crow segregation without resorting to the spectacle of violent, hateful acts. There is no violence in the film, but we see the weight of the system on Southern blacks. The men in the railroad car lead a lonely, transient life so they can maintain a higher rate of pay and keep a relative distance from the mainstream culture. Josie is a grown, educated, amd refined woman but the possibility for a fulfilling life with a husband who shares her sensibilities and her values is not there. Her preacher father enjoys the relative comfort of a middle-class life and a level of respect among his peers, but he is hemmed in by the necessity of accepting what threatens his whole community. On the other side of the line is the prostitute Rosie, who has no opportunities and can’t even make a living that way in such a poor community. Then there’s Duff. When he leaves the railroad car, he finds that he cannot have his principles and make a living too, and thus, the vibrancy of his personality – the very thing that attracted his wife to him – is diminished. Perhaps the most pathetic characters are Will Anderson, his woman Lee, and the woman keeping Duff’s son, whose desperate poverty is awful to witness.

As a document of the South, this film is powerful. Its timely portrayal of the realities on the ground are not overshadowed by the normal theatrical conventions: violence or sex. This is a human drama about real people’s lives. And to be candid, though the film’s substance is political in the raw sense, politics are virtually absent here. Some of Duff’s remarks could be construed as such, but in general, he is expressing the frustrations of a man who is facing hardship, not spouting polemics or an ideology. I can see why this movie was not a box-office success. It was ahead of its time, portraying black people as human beings with the same basic concerns that any person would have in a situation of powerlessness, frustration, oppression, and/or discrimination. Works of art and literature truly succeed when the particular becomes universal, and in this film, it does.

September 3, 2023

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week 203

If you’ve ever been moved to tears by a song, if you have a favorite track you blast in the car with the windows rolled down in the sun, or if listening to a good song can change your mood, then you have a talent for poetry. And who does not? Not matter how educated or unsophisticated, we all know the pleasure of listening to song. The root of that pleasure may be a mystery, but we all know it’s true: that words wrestled into music have a charm and power ordinary language does not.

— from the “Introduction: What is Poetry?” in The Seagull Book of Poems, fourth edition, edited by Joseph Kelly

Read more: The QuotesAugust 31, 2023

A Deep Southern Throwback Thursday: The Death of Mary Crovatt Hambidge, 1973

Though her name may not be familiar to many, Mary Crovatt Hambidge was an important Southern artist. This week marks the fiftieth anniversary of her death on August 29, 1973. Her legacy continues at The Hambidge Center in northeastern Georgia.

Born in 1885 in coastal Brunswick, Georgia, Mary Crovatt went to school in Cambridge, Massachusetts before moving to New York City, where she met artist Jay Hambidge. During a visit to Greece with him in 1919, she was fascinated by weavers doing their work near the Acropolis, and later became involved with the textile artists in Rabun County, Georgia where she moved in the late 1920s. Jay, who was eighteen years her senior, had died in 1924. According to the Hambidge Center’s History page, “While no marriage certificate has been discovered, they considered themselves married and referred to themselves as such in numerous documents. Until 1938, common law marriage was legal in New York, and Mary was the beneficiary and executor of Jay’s estate.” It was there in Georgia where she began the work for which she is now known.

The one time I went to the Hambidge Center, I was on a residency at the nearby Lillian E. Smith Center and the artist in the adjacent cabin suggested that I ride up there with her. We mostly looked at the place from the car, but I was lucky enough to be there when the grist mill operator was working. He was tired and sweaty but still kind and gracious about my request to buy some meal from him.

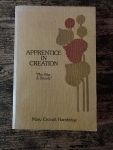

Another of my encounters with Hambidge’s works involves the book Apprenticeship in Creation: The Way Is Beauty, which was printed by the Hambidge Center in 1975. This whimsical and somewhat odd collection contains mostly short essays and even shorter ruminations. Though it spans more than 300 pages, many of those pages only contain a sentence or two. Overall, her writing gives the reader a sense of a very broad worldview, which leans toward a Unitarian-Universalist kind of spirituality combined with distinctly anti-commercial politics. It’s a good book to flip through and engage in small bites, though a straight read-through might be difficult.

Another of my encounters with Hambidge’s works involves the book Apprenticeship in Creation: The Way Is Beauty, which was printed by the Hambidge Center in 1975. This whimsical and somewhat odd collection contains mostly short essays and even shorter ruminations. Though it spans more than 300 pages, many of those pages only contain a sentence or two. Overall, her writing gives the reader a sense of a very broad worldview, which leans toward a Unitarian-Universalist kind of spirituality combined with distinctly anti-commercial politics. It’s a good book to flip through and engage in small bites, though a straight read-through might be difficult.

For those interested in knowing more about Mary Crovatt Hambidge, the thirty-minute documentary Mary Crovatt Hambidge: Whistler, Wanderer, Weaver, Utopian can be viewed on Vimeo.

August 27, 2023

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week 202

“Sho now,” Jody said. He took a toothpick from the china receptacle on the table and sat back. “Burning barns aint right. And a man that’s got habits that way will just have to suffer the disadvantages of them.”

— from the novel The Hamlet by William Faulkner

Read more: The QuotesAugust 24, 2023

A Deep Southern Throwback Thursday: The Death of Jerry Clower, 1998

It has been twenty-five years since the death of Southern comedy legend Jerry Clower. He died on this day in 1998, at age 71.

Jerry Clower’s rise to fame began earlier in the 1950s, and he was a bona fide Southern superstar by the 1970s and ’80s. Clower was born in 1926 in Liberty, Mississippi, then he had served in the Navy in World War II before becoming a salesman back home. Biographical sources report generally that the storytelling he developed in his sales job became so well-known that he was catapulted into comedy because he was just that good. The clip below is probably his most famous story, “Coon Hunting,” as it was recorded on his first album.

With his big hair and cheesy clothes and big personality, Jerry Clower was a performer, a hard worker, and a character. His Los Angeles Times‘ obituary called him a “hulking 275-pounder who wore stunning red or yellow suits,” then continued:

Clower pronounced his first name JAY-ree and was known for spinning truth-based tales about rural Southern culture and the fictional Ledbetter clan. His stories often involved church revivals, country fairs, cotton farming or crappie fishing.

The Mississippi Country Music trail historical marker dedicated to his memory recalls him this way:

A Liberty native, Jerry Clower (1926-1998) brought his colorful, observant, comic stories of southern life — developed as a sales tool as he worked as a fertilizer salesman — to live shows, recordings, television, bestselling books, and, for over twenty-five years beginning in 1973, Grand Ole Opry broadcasts. He became one of the most successful and acclaimed country comedians of all time.

It is no wonder that he was so successful. In addition to performing live, the comedian published several books and put out an album every year of the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s— some years more than one.

By all accounts, Jerry Clower is remembered fondly because he was just a good guy. Neither during his life nor since his death has news come out to say he was another kind of person behind the scenes. He was a family man who was married to one woman, Homerline, from August 1947 until his death in August 1998; they had four children, a son and three daughters. Those who knew him described him as a Christian man who lived his faith and whose comedy performances could be played in the church and the club alike. His Mississippi persona was not a put-on or a marketing gimmick— he was the real deal. One of the more endearing testimonials that appeared after his death was this unsigned editorial, which ran in several Mississippi newspapers. (You can click on it to enlarge it and read.) The world – the South, in particular – certainly misses him.

By all accounts, Jerry Clower is remembered fondly because he was just a good guy. Neither during his life nor since his death has news come out to say he was another kind of person behind the scenes. He was a family man who was married to one woman, Homerline, from August 1947 until his death in August 1998; they had four children, a son and three daughters. Those who knew him described him as a Christian man who lived his faith and whose comedy performances could be played in the church and the club alike. His Mississippi persona was not a put-on or a marketing gimmick— he was the real deal. One of the more endearing testimonials that appeared after his death was this unsigned editorial, which ran in several Mississippi newspapers. (You can click on it to enlarge it and read.) The world – the South, in particular – certainly misses him.

Other Tributes:

The Grave of Jerry Clower, from the Back Roads channel on YouTube

“The Mouth of Mississippi, Jerry Clower” (October 2022) from The Southern Voice website

August 20, 2023

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week 201

Zen insight is at once a liberation from the limitations of the individual ego and a discovery of one’s “original nature” and “true face” in “mind” which is no longer restricted to the empirical self but is in all and above all. Zen insight is not our awareness, but Being’s awareness of itself in us.

— from the chapter “Mystics and Zen Masters” in Mystics & Zen Masters by Thomas Merton

Read more: The Quotes