Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 432

May 15, 2015

Aca-Pale in Comparison

It’s maybe fair to assume that nobody expected Pitch Perfect, the 2012 comedy about an ill-matched, preposterously awkward collegial a cappella troupe, to be as good as it was. For one thing, the demographic it targeted was women under the age of 25. Its director, Jason Moore, was a rookie whose only previous experience was in theater and television. And its premise was enormously dorky, even if the concept of a group of misfits coming together in song in an educational setting had been previously popularized by Fox’s Glee. Pitch Perfect was, by turns, gross, offensive, and glorious, and its combination of acerbic one-liners and a cast full of oddballs made it that Hollywood white whale: a word-of-mouth success.

Related Story

Music Made 'Glee,' and Music Killed It

So it might be unfair to expect Pitch Perfect 2 to live up to the unanticipated brilliance of the first movie, and the film doesn’t really seem to try, even with the producer Elizabeth Banks now in the director’s chair. All of the characters are back—Anna Kendrick as the tomboyish wannabe DJ Beca, Rebel Wilson as the foul-mouthed extrovert Fat Amy, Brittany Snow as the sunny peacemaker Chloe—but this time, their chemistry is off, and what felt like winking cheekiness in the first movie can come across now more like clumsy provocation.

The film opens three years later, with Beca and the rest of the Barden Bellas living in a house on campus, having won three straight national championships. While performing an exhilarating set in front of the President and the First Lady at the Kennedy Center (a mashup of Kesha’s “Timber” and Miley Cyrus’ “Wrecking Ball”), Fat Amy comes in, indeed, like a juggernaut, suffering an unfortunate wardrobe malfunction that renders the Bellas, in the Barden University dean’s words, “a national disgrace.”

After this mishap, with their reputations in tatters and having been banned from recruiting new members, the plot revolves around the Bellas trying to redeem themselves and keep up with the competition: an absurd German troupe called Das Sound Machine, who manage to be world sensations even though accents this fake haven’t been seen in cinema since Bram Stoker’s Dracula. And after three years, the ladies are drifting apart. Beca secretly takes an internship at a recording studio where Snoop Dogg is trying to cut a Christmas album (her boss, played by Keegan-Michael Key, is a high point), Fat Amy is still secretly sleeping with Bumper (Adam DeVine), Chloe has deliberately failed Russian for three years straight so she never has to graduate and move on in the world, and … no one else gets anything to do. At all.

Pitch Perfect somehow delivered more than a dozen fully formed characters in under two hours, with much of the comedy coming from the supporting characters—the proudly sexually active Stacie (Alexis Conrad), the sexually ambiguous Cynthia-Rose (Ester Dean), the unabashed “I ate my twin in the womb” pixie Lilly (Hana Mae Lee). They’re all here, as is writer Kay Cannon, whose history working on shows like 30 Rock and New Girl was felt in every inappropriate punchline in the first movie. But they might as well not be, because they’re left alone almost entirely, with the focus instead being two new Bellas: a “legacy,” Emily (Hailee Steinfeld), who’s allowed to join because her mother was a legendary Bella in the past, and Florencia (Chrissie Fit), who gamely trots out gag after gag about the horrors of being from Central America (“when I was nine, my brother tried to sell me for a chicken.”)

What felt like winking cheekiness in the first movie can come across now more like clumsy provocation.The movie is slyly feminist throughout: In her role as the a cappella commentator Gail Abernathy-McKadden, Elizabeth Banks points out that the Bellas are icons for “girls all over the world who are too ugly to be cheerleaders.” The media criticism leveled at both Fat Amy and the Bellas feels appropriately hysterical in tenor, with everyone from Jake Tapper to the women of The View jumping in the fray to condemn the troupe’s lack of dignity (even in 2015, nothing is apparently as shocking to America as uncensored lady parts). And the plot doesn’t even try to mine drama from Beca’s relationship with Jesse (Skylar Astin), who appears only briefly as a loving and supportive boyfriend. In this—in making a movie about women that’s only summarily concerned with their love lives, at best—Pitch Perfect 2 should be saluted. But it also coasts on its own success, delivering quips that feel like pallid imitations of the first film’s zany charm, and resisting any urge to make the few song-and-dance routines any bigger than they contractually have to be. After the opening montage, an hour rolls by with barely a single number. “Is it weird that we didn’t do any singing?” asks Emily after her first Bella rehearsal. She’s not the only one wondering.

There are undeniable highlights: Reggie Watts, John Hodgman, Joe Lo Truglio, and Jason Jones have cameos as the second-weirdest non-collegiate a cappella troupe (the first-weirdest is even better, but to say any more would ruin the fun). There’s a weekend at a team-building lodge where another legacy member returns to try and whip the Bellas back into shape. There’s Robin Roberts (really). There’s Snoop Dogg singing “Winter Wonderland” while Keegan-Michael Key tries not to emit a primal scream of musical disgust. And there’s ultimately a showdown with a group of genetically superior Germans, in which only history can point at the probable victors.

But there isn’t the same sense of gleeful disregard for what people might think, or the weird, indescribable joy that comes from seeing a group of completely incompatible people come together in an interpretation of Kelly Clarkson that can only be described as transcendent. The actors don’t seem all that energized to be back, and the overarching sense of ennui is contagious. Instead, Pitch Perfect 2 relies, like so many comedies do, on fart gags and racial stereotypes and odd-couple pairings, without any of the wryness from the first film to indicate that everyone, including the audience, is in on the joke. It is, in the most basic terms, the worst thing a reigning a cappella champ can be—flat.

May 14, 2015

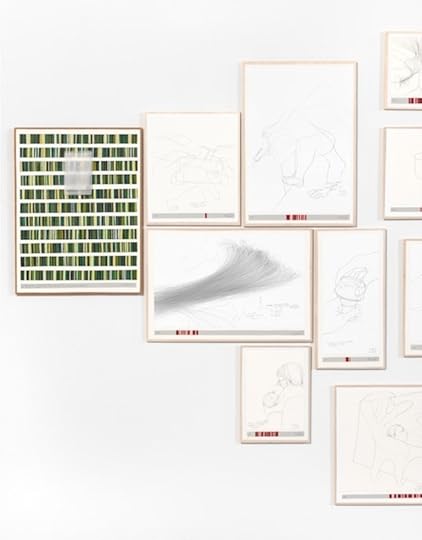

Painting By Numbers

It’s unlikely Claude Monet would have been Claude Monet without the portable paint tube, which allowed him to work outside and experiment with capturing natural light. Andy Warhol wouldn’t have been Andy Warhol without the modern movie star or the mass-produced Campbell’s soup can. Art is as much a product of the technologies available to artists as it is of the sociopolitical time it was made in, and the current world is no exception. A growing community of “data artists” is creating conceptual works using information collected by mobile apps, GPS trackers, scientists, and more.

Data artists generally fall into two groups: those who work with large bodies of scientific data and those who are influenced by self-tracking. The Boston-based artist Nathalie Miebach falls into the former category: She transforms weather patterns into complex sculptures and musical scores. Similarly, David McCandless, who believes the world suffers from a “data glut,” turns military spending budgets into simple, striking diagrams. On one level, the genre aims to translate large amounts of information into some kind of aesthetic form. But a number of artists, scholars, and curators also believe that working with this data isn’t just a matter of reducing human beings to numbers, but also of achieving greater awareness of complex matters in a modern world.

Related Story

Art confronts the uncertainty of human existence: Why am I alive? What makes me different from anybody else? Handprints made some 40,000 years ago, are a common feature of Upper Paleolithic cave art—a kind of prehistoric selfie. National Geographic describes the early artists as sending a timeless message: “Like you, I am human. I am alive. I was here.” So it’s unsurprising that many data artists are responding to an increasingly data-saturated culture. After all, almost every human interaction with digital technology now generates a data point—each credit-card swipe, text, and Uber ride traces a person’s movements throughout the day. The smartphone, as The Economist recently described, is a true personal computer, the defining innovation of the era, on par with the mechanical clock or the automobile in past centuries.

In turn, there’s been what the Pew Research Center calls a self-tracking explosion, whether it’s counting the number of calories or using a mood app to glean patterns in one’s mental state. Like a fingerprint, no two people have the same data set. A couple sharing a bed follow independent sleep cycles. Friends who spend the day together count different steps; their phones connect to different IP addresses. But what’s more remarkable is the idea that within all of these numbers lies a better way of understanding ourselves. The information doesn’t just provide a broad document of a life lived in the early 21st century: It can reveal something deeper and even more essential.

* * *

One data artist who believes this is Laurie Frick, who splits her time between Austin and New York City. She came to art circuitously, after spending 20 years in tech working for HP and Compaq and co-founding a software company. Frick believes that while numbers are abstract and unapproachable, human beings respond intuitively—and emotionally—to patterns. Unlike many of her peers, Frick has no assistants. She uses self-tracking data to construct objects and large-scale installations, including one called Floating Data that’s about two stories tall and made from 60 anodized aluminum panels that represent her walking patterns. Frick used her own records, gathering steps on her Fitbit and combining it with location data from the online program OpenPaths and her iPhone’s GPS. “I drew a little track that tries to capture the experience of walking speed, and the feel of walking through a busy neighborhood near my apartment in Brooklyn,” she explained.

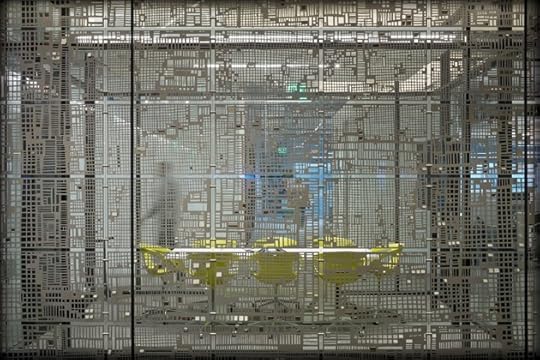

Floating Data, Walking Patterns, 2014. Laurie Frick

Floating Data, Walking Patterns, 2014. Laurie Frick In a series called Moodjam, Frick took thousands of Italian laminate countertop samples from a recycling center and created a series of canvases and billboard-sized murals based on her temperament. For weeks, she manually tracked her feelings, using the online diary Moodjam, which allows users to express their emotions in color patterns. The smaller Moodjam pieces capture only a day’s worth of data, Frick’s ups and downs over a 24-hour period. Larger ones reflect weeks of journal keeping and internal swings. For her upcoming solo exhibition this May, at New York’s Pavel Zoubok Gallery, Frick has made wood, leather, and paper assemblages based on accounts of her daily activities. In several pieces, she used apps like ManicTime on her laptop and Moment on her iPhone to track each click and touch of her screen for almost a month. Frick is adamant that her work is about more than simply visualizing information—that it serves as a metaphor for human experience, and thus belongs firmly in the art world.

Moodjam 1, 2012. Abet Laminati italian countertop samples on alumalite panels. Laurie Frick

Moodjam 1, 2012. Abet Laminati italian countertop samples on alumalite panels. Laurie Frick The distinction between data presentation and data art is often fuzzy, and the art world still struggles to separate the two. For example, MOMA’s recent show, Scenes for a New Heritage: Contemporary Art from the Collection, included digital prints with images generated from ArcGIS software. The work, Million Dollar Blocks, was designed at Columbia University’s Spatial Information Design Lab and showcased a series of maps based on data from the criminal-justice system. According to the project, of the more than two million incarcerated people in the U.S., a disproportionate number come from a handful of neighborhoods in the largest cities. The maps are meant to pose ethical and political questions about criminal justice reform, and they do that successfully. But Million Dollar Blocks may just be powerfully presented data, rather than conceptual art, which is where the artist’s underlying idea is more important than the execution.

7 Stages of ALS, 2010. ALS is a disease that defies pattern recognition: This work color-coded the cases of 264 patients at the Neurology Clinic in Charlotte, N.C. by severity of symptoms. Cut 2x4 wood and pigment. Laurie Frick

7 Stages of ALS, 2010. ALS is a disease that defies pattern recognition: This work color-coded the cases of 264 patients at the Neurology Clinic in Charlotte, N.C. by severity of symptoms. Cut 2x4 wood and pigment. Laurie Frick Similarly, the Whitney Museum of American Art’s current show, America is Hard To See, includes a 1971 piece by Hans Haacke, Shapolsky et al Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real Time Social System. The work comprises 146 photographs of Manhattan apartment buildings—mostly tenements—maps of Harlem and the Lower East Side, as well as charts documenting the ownership structures of the buildings. Haacke culled the data from public record, and the art, according to the Whitney’s label, is an “institutional critique” that “chronicles the fraudulent activities of one of New York City’s largest slumlords over the course of two decades.” Yet in a world of enhanced graphics, simply displaying data effectively—with or without photography—won’t constitute compelling art on its own. Nor does every important data pattern raise existential questions.

“I say, run toward the data," Frick said. "Take your data back and turn it into something meaningful.”But by blurring the boundaries, conceptual artists are helping scientists see their research more creatively. The New York Times recently chronicled Daniel Kohn, a Brooklyn-based painter, who spent roughly a year at the Albert Einstein School of Medicine teaching geneticists ways to represent their digital data in more intuitive ways. And while algorithms have seeped into daily life—informing everything from consumer music choices to dating options—they’re also edging into conceptual art. In March, the website Artsy held what it called the world’s first Algorithm Auction, “celebrating the art of code.” Works included Turtle Geometry, an 11-inch stack of programming on dot-matrix printer paper from 1969 made by Hal Abelson, a professor of electrical engineering and computer science at MIT. In fact, many data artists straddle art and science as Leonardo da Vinci did. Curators and historians still disagree about how to classify him: great artist or scientific genius? Or does the divide even matter?

Red Pokey Sleep, 2011. Nightly sleep data captured using a Zeo, EEG sleep monitor. Color-coded by type of sleep. Watercolor and ink on paper. Laurie Frick

Red Pokey Sleep, 2011. Nightly sleep data captured using a Zeo, EEG sleep monitor. Color-coded by type of sleep. Watercolor and ink on paper. Laurie Frick Current tools make self-tracking more efficient than ever, but data artists are hardly the first to express themselves through their daily activities—or to try to find meaning within life’s monotony. The Italian Mannerist painter Jacopo Pontormo kept records of his daily life from January 1554 to October 1556. In it, he detailed the amount of food he ate, the weather, symptoms of illness, friends he visited, even his bowel movements. In the 1970s, the Japanese conceptualist On Kawara produced his self-observation series, I Got Up, I Went, and I Met (recently shown at the Guggenheim), in which he painstakingly records the rhythms of his day. Kawara stamped postcards with the time he awoke, traced his daily trips onto photocopied maps, and listed the names of people he encountered for nearly 12 years.

* * *

“Have you ever thought about how much is known about you?” Frick asked in one of our conversations. Not what pops up in Google or on social media, she clarified, but what companies know about your character. If you have a Kindle, Amazon knows how fast you finish a book, and whether you’re a cheater and skip chapters or read the ending first. Netflix knows whether you’re a binge watcher. E-ZPass knows where you go, even on local streets. Frick understands that this type of data collection can cause discomfort. Few of us like the idea that the government or Google is watching our every move. As a data artist, however, she sees her role as convincing people to want more personal data—regardless of who’s tracking.

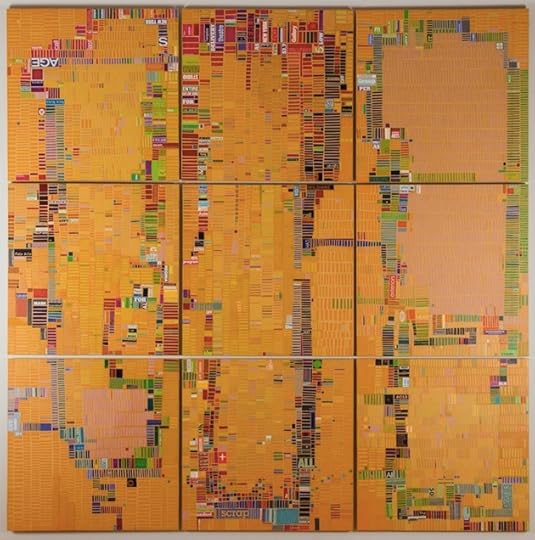

Austin, Week 47, 2015. Three walking tracks in Austin, light and color to match the heat of central Texas. Cut found paper and handmade paper on 9 panels, 2015. Laurie Frick

Austin, Week 47, 2015. Three walking tracks in Austin, light and color to match the heat of central Texas. Cut found paper and handmade paper on 9 panels, 2015. Laurie Frick “In all of these patterns, I do think there is an essential idea of who we are,” Frick said. Data art can’t capture the essence or totality of somebody—if either exists—any more than a handprint on a cave wall can. But she believes personalized data art can accomplish something traditional art forms can’t: It allows a viewer to see her nuances and idiosyncrasies in higher resolution—and to discover things she may have forgotten about herself or perhaps has never known. “I think people are at a point where they are sick of worrying about who is or isn’t tracking their data,” said Frick. “I say, run toward the data. Take your data back and turn it into something meaningful.” To prove her point, she’s developed a free app, Frickbits, which allows anyone to “create the ultimate data-selfie,” by turning personal data into personalized art.

The American artist Hasan Elahi turned to data in the wake of 9/11. A year after the attacks, Elahi, an associate professor at the University of Maryland, was detained at Detroit’s Metro Airport upon his return from the Netherlands. FBI agents suspected him of hoarding explosives in a Florida locker, thanks to an erroneous “tip” called into law enforcement. Elahi was born in Bangladesh and grew up in New York City, but is an extensive traveler. On average, he logs more than 100,000 miles a year, speaking at conferences and displaying his art. After six months of FBI interrogations and nine lie-detector tests, Elahi was finally cleared. But the experience transformed his relationship with personal information and inspired him to create a website site Wired called “the perfect alibi.” As Elahi puts it: When the Feds come after you, you can either resist or turn the tables.

One on One, 2010. Hasan Elahi

One on One, 2010. Hasan Elahi At first, Elahi started calling the FBI every time he would travel to notify them of his itinerary and his general whereabouts (during the investigation, they’d shared their contact info). Then, he began emailing them. “I would just say, hey giving you a heads up, I’m going to be out of town tomorrow,” he described. “Here are my plans. Here’s where I’m staying.” Soon, he began posting minute-by-minute photos of his life—sometimes a hundred a day at TrackingTransience.net—unmade hotel beds, receipts, Starbucks cups, toilets he’s used, the beauty of modern tedium. Elahi uses his iPhone’s GPS to sync his movements to a live map, also on his site. In the past few years, he’s amassed hundreds of thousands of pictures and data points. “It’s economics,” he said. Personal data conforms to supply-and-demand principles. So the best way to protect privacy is to give away as much as possible and “flood the market,” so that the government’s supply is worthless. People can also track themselves much more accurately than a third party. “You have data?” he asked, “Well I’ve got data too. By putting everything out there, the government’s data no longer means very much. I can tell them what I ate, where I slept, exactly what I was doing on every day over the last decade.”

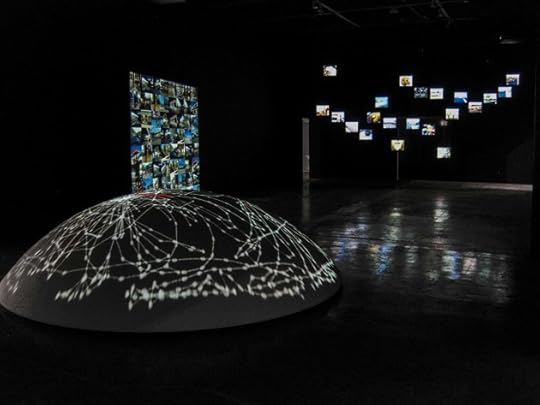

Thousand Little Brothers, 2014. Detail from a composite image made of 32,000 images taken from the artist’s daily life. Courtesy of Hasan Elahi and Open Society Foundations

Thousand Little Brothers, 2014. Detail from a composite image made of 32,000 images taken from the artist’s daily life. Courtesy of Hasan Elahi and Open Society Foundations Elahi may be the first artist to track himself in a post-9/11 context, but he’s hardly the first conceptualist to examine people’s unease with surveillance. During our interviews, Elahi pointed to Sophie Calle, who has been called France’s most celebrated conceptual artist. In 1980, Calle met a stranger named "Henri B." at a Paris gallery opening who mentioned he was soon leaving for Italy. Disguised in a blond wig, Calle famously followed him to Venice—without either his knowledge or prior consent. Tracking him throughout the city, Calle secretly documented Henri B.’s comings and goings from his hotel, as well as reportedly sneaking into his room to photograph his possessions. Fans of Calle believe her work treads a delicate balance between stalking and art. For her 1981 project The Shadow, Calle hired a private investigator (through her mother) to follow and photograph Calle for a day. The pictures appear rather mundane—a woman wandering the streets of Paris—and the detective’s notes are dry. In fact, Calle led the man on a tour of places imbued with meaning for her, such as the park where she had her first kiss. What appeared to be a set of trivial data points actually told an emotional and personal narrative about Calle.

Income’s Outcome. Danica Phelps

Income’s Outcome. Danica Phelps But even today, data art isn’t all Google Maps and iPhones—its practitioners embrace traditional mediums too. One of the earliest examples of the genre is Danica Phelps. In July 2008, two months before Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, The New York Times wrote, “For the last decade, Danica Phelps has chronicled her personal and financial lives with an exhaustive system of lists and charts accompanied by diagrams of colored stripes.” Her ongoing project, titled Income’s Outcome, tracks the money generated by each of her drawing’s sales. Every time somebody buys a piece from the series, Phelps creates a new series of drawings, depicting what she bought with the money from the previous transaction. The drawings reflect how consumption and debt are intricate parts of our personal identity. Phelps has also painted every dollar in her bank account, as well as gray strips for every dollar she owes her bank for her mortgage—627,000 grey lines. According to Phelps, Income’s Outcome is meant to question how we assign value and meaning to the purchases we make. In light of the 2008 market crash, the series is a critique of fairly banal activities—buying things and borrowing for a home—but both of which cause anxiety and fear in modern life. Art critics have likened Phelps to On Kawara, as she also documents the passage of time—but in this series she does so through money. “When I started showing my work, I put the price right on the drawing,” she recalled. “In my first exhibition, there were pieces ranging from $7 to $1600, based on how much I liked the drawing.”

There’s also the Danish artist Jeppe Hein, known for sculptures that frequently use mirrors in a gallery or outdoor space to reflect its visitors. But for his most recent show, All We Need Is Inside, at Chelsea’s 303 gallery, he experimented with self-tracking and data art as way to reveal himself to the viewer. In Breathing Watercolors, Hein’s breath guides his application of blue stripes painted directly onto a large white wall. As the gallery’s press release explains, “The intensity of color, deep and vigorous at the beginning of each stroke, gradually fades into a pale shade towards the bottom of each stripe, physically recording the process of air gradually escaping from the body.”

Breathing Watercolors. Jeppe Hein, Courtesy of 303 Gallery

Breathing Watercolors. Jeppe Hein, Courtesy of 303 Gallery Art is a constant march of expansion, according to Harvey Molotch, a professor of sociology and metropolitan studies at New York University, whose research includes the sociology of art. Pop art incorporated comic books and ordinary soup cans. Edvard Munch’s expressionist painting, The Scream captured the anxiety and isolation of modern life. “Now there’s the digital self, the newest kid on the block and so of course, artists are there,” he explained. “Art and environment are very much in cahoots.” In 2007, the Wired editors Gary Wolf and Kevin Kelley proposed a new movement. They called it the Quantified Self and now count over 45,000 members on their website and hold “self-quantifier meet-ups” around the globe.

For example, the Boston Quantified Self chapter describes itself as a “a regular show-and-tell for people who are tracking data about their body and conducting their own personal investigations and research into their bodies, minds, and selves.” “Datification” is a cultural process by which people put enormous faith in data, explained Gina Neff, an associate professor of communication at the University of Washington and the School of Public Policy at Central European University, as well as the co-author of the forthcoming book The Quantified Self. “What we see in the ‘quantified self,’” Neff explained, “is that people have taken up an N of 1, truly exploring what data means in their own personal lives, or in the artist’s case, as a form of artistic expression.” The line between data and self, she believes, is only where a person chooses to draw it.

Yet the question remains whether data art can endure as much as a simple, striking handprint on a cave wall. On the one hand, data art may just be a link in a chain of artists who record and display their personal movements— some of whom will be displayed at the world’s leading museums decades from now, some who will fall by the wayside. On the other, data art may be the apogee of self-expression—a digital fingerprint that says more about modern man, and the inevitable forward march of time, than anything artists have been able to produce before.

A Long-Awaited Reform to the Patriot Act

Fourteen years after the Patriot Act gave sweeping spy powers to the government in its war against terrorism, a consensus is finally emerging in Congress that the government needs to be reined in—at least a bit. The next two weeks could determine whether that consensus will yield a new law.

In a bipartisan vote of 338-88, the House on Wednesday afternoon passed the USA Freedom Act, which seeks to restrain the nation’s surveillance state while extending other key parts of the 2001 Patriot Act that are set to expire at the end of the month. At its core, the House measure ends the NSA’s bulk collection program first exposed two years ago by Edward Snowden, and requires the government to be more transparent about the data it seeks from citizens. The vote comes just a week after a federal appeals court ruled that PATRIOT Act’s controversial Section 215 did not authorize the bulk collection program, which allowed the NSA to access domestic telephone metadata. The ruling by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals didn’t end the program, which the Freedom Act would.

Related Story

Does the PATRIOT Act Allow Bulk Surveillance?

The House measure represented a rare and genuine bipartisan compromise, drawing support from the original author of the Patriot Act, conservative Representative James Sensenbrenner of Wisconsin, along with liberal Democrats like John Conyers of Michigan and Jerrold Nadler of New York, staunch civil libertarians. The White House has said that President Obama would sign it. Yet it faces an uncertain fate in the Senate, where Majority Leader Mitch McConnell wants to extend the entire Patriot Act, untouched, for another five years. Democrats have vowed to block that effort and are hoping that the strong House vote and the chance that the surveillance programs could expire altogether on June 1 will force McConnell to accept the reform bill. A short-term extension, giving the Senate more time to debate, is also possible. (The Senate has a recess scheduled after next week.)

“Today, we have a rare opportunity to restore a measure of restraint to surveillance programs that have simply gone too far.”The bill’s supporters say it’s the most far-reaching reform to U.S. surveillance programs in nearly 40 years. On the House floor, Conyers said the bill would put an end to “dragnet surveillance” in the United States. “Today, we have a rare opportunity to restore a measure of restraint to surveillance programs that have simply gone too far,” he said. Many privacy advocates, however, think it doesn’t go far enough to protect civil liberties. They’ve criticized provisions that expand surveillance powers by allowing access to data from more modern forms of communication, like video chats. And they say the proposal doesn’t sufficiently limit the search terms the NSA can use in requesting data and that it contains too many loopholes that would allow the government to access data in an emergency without a warrant. “It completely fails to meaningfully curtail mass surveillance and actually codifies some of the worst modern spying practices into law,” said Evan Greer, campaign director of Fight for the Future, an Internet-freedom advocacy group.

Activists also find little comfort in the fact that the bill has drawn support from the intelligence community and tech firms. An earlier version of the proposal passed the House last year but fell two votes of overcoming a filibuster in the Senate. The current bill is worse, Greer said, because it weakens transparency requirements and makes it easier for the government to cite “state secrets” and withhold information from a new “special advocate”created to serve as a watchdog for the FISA court.

What’s interesting is that supporters in both parties readily admit that the government will likely try to stretch the bounds of the new law just as it has with the Patriot Act. The difference, they say, is that the public will know when they’re doing it. “The government may one day again attempt to expand its surveillance powers by clever legal argument, but it will no longer be allowed to do so in secret,” Conyers argued.

“It completely fails to meaningfully curtail mass surveillance and actually codifies some of the worst modern spying practices into law.”There’s also recognition among some privacy advocates that although the Tea Party has helped elect more libertarian-minded conservatives to Congress, the USA Freedom Act is likely the most significant reform possible under majorities still led by old-school Republican national-security hawks, and at a time when fears of a terrorist attack remain ever-present. The ACLU, for example, is taking no formal position on the bill even though it sent lawmakers a list of areas in which it didn’t go far enough. That dynamic was on display this week when GOP House leaders rejected a bid by a group of younger libertarian members to offer amendments that would have further restricted the NSA. "This is a very delicate issue,” Speaker John Boehner explained to reporters. “I know members would like to offer some amendments, but this is not a place for people to bring out the wrecking ball.”

Broad majorities of House Democrats and Republicans decided on Wednesday that the Freedom Act was good enough as is, increasing pressure on the Senate to accept their compromise. Yet just how significant would the new law be? Lawmakers in Congress have a tendency to hail just about any bill that gets a bipartisan vote as a landmark achievement. Staunch privacy advocates dismiss it for paying lip service to reform while leaving intrusive surveillance programs untouched. The truth on this one lies somewhere in the middle, said Benjamin Wittes, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and the author of its Lawfare blog. “This is a significant reform and rollback of a FISA program,” he told me. But it pales in the context of the extensive collections of NSA surveillance tools and the many, often unrelated provisions of the Patriot Act. Section 215 is, after all, just one section, and the reforms in this bill beyond ending bulk data collection are modest. “This is one, small program,” Wittes said. “It is not the big enchilada, or even one of the big enchiladas of the NSA programs.”

May 13, 2015

Who Is in Charge of Burundi?

On Wednesday evening, citizens of Burundi went to sleep while it remained unclear exactly who is in charge of their country. Earlier in the day, Major General Godefroid Niyombare announced that he had deposed Pierre Nkurunziza, leader of the tiny east African country, while the president was at a summit in Tanzania. (Three months ago, Niyombare was dismissed as the country’s intelligence chief.)

The general’s radio announcement set off wide celebrations in the capital Bujumbura and police seemed to withdraw from the streets. From afar, however, Nkurunziza rejected the claims in a statement posted on social media.

"A group of soldiers mutinied this morning and made a fantasy declaration of a coup d'etat," said the statement. "This attempted coup was foiled and these people ... are sought by defense and security forces so they are brought to justice."

At The Week, Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry offered some background:

The incumbent president (Pierre Nkurunziza) wants to run for a third term, in defiance of the country's constitution; people are rioting in the streets; the police are cracking down; people are dying; the stench of a coup, or a civil war, or worse, is in the air.

The country’s history should inspire fear that the situation could devolve into mass violence; Burundi has a legacy of ethnic tension in the wake of a 12-year civil war that ended in 2005, and the country remains politically unstable.

At the summit in Tanzania, a number of African leaders offered their support for the embattled president. As of Wednesday night, it was unclear where Nkurunziza was. The BBC cited unconfirmed reports that Nkurunziza had attempted to fly back to Burundi but reversed course back to Tanzania.

Senate Democrats Relent on Trade Bill

Updated May 13, 3:35 p.m.

Senate Democrats on Wednesday relented in their opposition to the consideration of legislation expediting trade agreements, just 24 hours after their vote blocking the bill put a temporary halt on President Obama’s trade agenda.

In exchange for allowing Trade Promotion Authority to move forward, Democrats will get to vote Thursday on bills cracking down on Chinese currency manipulation and giving preferential treatment to imports from African countries. Majority Leader Mitch McConnell announced the deal on the Senate floor on Wednesday. Trade Promotion Authority allows the president to negotiate agreements that Congress must vote on without amendment. To secure Democratic votes, McConnell will combine that bill with a separate measure providing aid to workers displaced by foreign trade. Senate Democrats on Tuesday had demanded that McConnell package all four bills together, but he refused on the grounds that the currency proposal would have sunk the underlying trade legislation in the House. Now House Republicans can choose to ignore the currency and Africa measures even if they clear the Senate.

Tuesday’s rebuke of the president was hailed as a victory for the progressive activists led by Senator Elizabeth Warren. But the White House had downplayed it as a “procedural snafu,” and ultimately that might prove to be the case. Democrats will be able to tell their constituents they voted to crack down on China, but that bill is unlikely to become law. A final Senate vote on the fast-track trade bill is expected next week, and then it will face an even tougher path in the House, where a majority of liberal Democrats oppose Obama’s trade push.

May 12, 2015, 3:45 p.m.

On Tuesday, the Senate failed to overcome a Democratic filibuster blocking “fast-track” Trade Promotional Authority from coming up for debate. For the past week, President Obama’s toughest opponent in his uphill struggle with Democrats over trade legislation has been Elizabeth Warren, the progressive leader who continues to fight the president even though she doesn’t want to be president. But it turns out that the president’s most difficult obstacle is not Warren but Harry Reid, his erstwhile ally and the Democratic leader in the Senate.

In opposing the trade bill, Warren has accused Obama of asking Congress to “grease the skids” for an international agreement that is being negotiated in secret and boosts corporations at the expense of workers. She’s even suggested that a pending trade deal with the European Union could unravel Obama’s prized Wall Street reform law, Dodd-Frank.

Warren has gotten under Obama’s skin to a degree that many of his Republican critics have not. “She’s absolutely wrong,” the president told Matt Bai of Yahoo News last week. Obama repeatedly referred to the first-term Massachusetts senator as “Elizabeth”—a tic probably meant to highlight their enduring friendship but which may have come across as condescending. And as if to further diminish a woman who has taken on the status of icon in some liberal circles, the president tossed around a pair of words—“law professor” and “politician”—that Republicans routinely use to knock him down a peg or two. (Remember, there is nothing a politician hates more than when another politician calls them out for being a politician.)

The truth of the matter is that Elizabeth, you know, is a politician just like everybody else. She’s got a voice that she wants to get out there, and I understand that. On most issues, she and I deeply agree. On this one though, her arguments don’t stand the test of fact and scrutiny.

The White House always understood trade authority would be a tough sell with Obama’s liberal base and that Warren would probably emerge as a leader of the opposition. With Republicans broadly supportive of the legislation, all the administration needed was a handful of Democrats in the Senate and a few dozen in the House to secure package. Yet on Tuesday, the bill failed in its initial attempt to clear even that low threshold.

Reid has made clear for months that he would vote against Trade Promotion Authority, but there is a big difference in Congress between a legislative leader who opposes a piece of legislation and one who plans to use his power to kill it. Administration officials told me they were confident Reid wouldn’t actively try to torpedo the bill, pointing to a statement he made in December that he wouldn’t “stand in the way” of Obama’s push for trade deals with Pacific and European nations. But they grew more concerned watching Reid rally nearly the entire Democratic caucus, including several pro-trade senators, to block Mitch McConnell’s attempt to bring the fast-track bill to the floor.

The president’s most dangerous Democratic opponent on trade is not Warren but Harry Reid, his erstwhile ally and the party leader in the Senate.Reid first threatened to stall the trade bill until Republicans brought up unrelated legislation to extend the Highway Trust Fund and reform the Patriot Act. In recent days, however, he’s pushed McConnell to package Trade Promotion Authority with other bills that would crack down on currency manipulation and provide assistance to workers who lose their job because of trade deals. McConnell has resisted, promising only that those measures could come up as amendments but not guaranteeing their passage. Without that assurance, Democrats banded together and defeated a procedural motion on Tuesday afternoon.

A Senate Democratic aide on Tuesday insisted that Reid was not trying to kill Obama’s trade bill—he just wanted to improve it and get as much as he could from Democrats. “Everyone here assumes trade will pass eventually,” the aide said. “The goal right now is to use our leverage to secure a better deal. It’s that simple.” Josh Earnest, the White House press secretary, also downplayed the development. “It is not unprecedented, to say the least, for the United States Senate to encounter procedural snafus,” he told reporters. (When ABC’s Jonathan Karl pointed out that “snafu” is an old World War II military acronym meaning “Situation Normal, All Fucked Up,” Earnest smiled and replied, “This is a family program, Jonathan.”)

Progressive activists opposed to the trade deal celebrated Tuesday’s vote, but they aren’t taking Tuesday’s vote as a definitive victory either. “The hundreds of thousands of activists who have rallied behind Senators Warren, Brown, and Sanders to defeat the [Trans-Pacific Partnership] will not rest until it is dead, buried, and covered with six inches of concrete,” said Charles Chamberlain, the executive director of Democracy for America. “We know the forces pushing the job-killing TPP won’t stop here, and they should know, neither will we.” Jim Kessler, vice president for policy at the centrist think-tank Third Way, shot back: "This is not close to being over."

Obama has fought progressives before and won, most memorably in his efforts to pass mediocre fiscal deals that they believed gave away too much to Republicans. But this struggle is different, and more reminiscent of the failed push that President George W. Bush made, during the twilight of his own presidency in 2007, to get enough Republicans to join the Democratic congressional majority in supporting comprehensive immigration reform. Then as now, immigration was a flashpoint for conservatives who feared a repeat of the broken promises made 20 years earlier by a president of their own party, Ronald Reagan. Democrats invoking the passage of NAFTA under Bill Clinton are invoking similar fears on trade. Barbara Boxer, the veteran California liberal, said in a floor speech that she was “suckered” into supporting fast-track authority—which helped expedite the NAFTA talks— in the late 1980s and came to regret it. “They’re making all these promises,” she said of the current TPA push, “and the more I hear it, the more I hear the echoes of the NAFTA debate.”

Just like Bush, Obama is finding that his powers of persuasion within his own party are dwindling the closer he gets to retirement. And while attention shifts to the campaign to replace him, he has gotten no help—so far—from Hillary Clinton, whose position on the trade deal is one big hedge. The setback in the Senate for Obama’s cause on Tuesday may be temporary, and either Reid or Clinton can still step in to turn momentum back in his favor. But without their assistance, another one of the president’s major second-term priorities could be doomed.

The Twisty Satisfaction of Wayward Pines

As with many small-town mysteries, it’s best to get something out of the way quickly with Fox’s new series Wayward Pines: This is no Twin Peaks. Countless shows have consciously or unconsciously paid homage to Mark Frost and David Lynch’s surreal melodrama since its 1990 debut, and Wayward Pines falls firmly in the “consciously” column. The show follows a federal agent (played by Matt Dillon) as he investigates the disappearance of two of his colleagues in a small northwest town (this time, it’s in Idaho, not Washington). The show’s titular town looks like a sleepy slice of Americana, but looks can be deceiving.

Related Story

Maybe a Twin Peaks Revival Without David Lynch Wouldn't Be That Bad

The Twin Peaks influence is most obvious in the setting, but the plot of Wayward Pines represents another resurgent trend in television: the “miniseries event” that promises to actually solve a mystery within one season rather than string audiences along for spectacularly diminished returns. Twin Peaks became a cautionary tale for serialized storytelling: Once audiences know who the killer is, what compels them to stick around? Most TV shows with a supernatural element to them have relied on a procedural element to sustain the punishing 22 episode-per-season model of programming, The X-Files or Lost, but even these shows faltered when they finally got around to solving their original mysteries.

Adapted from the novel Pines by Blake Crouch, Wayward Pines is written by Chad Hodge and executive produced by M. Night Shyamalan. When Agent Ethan Burke arrives in Wayward Pines looking for his lost partners, it’s immediately apparent that something strange is going on: There’s a friendly bartender (Juliette Lewis) whose existence no one else acknowledges. Burke quickly finds one of his former partners (Carla Gugino), but she’s happily married with a new name. There’s a local sheriff (Terrence Howard) giving him a hard time and a psychiatrist (Toby Jones) insisting there’s something wrong with his brain.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given Shyamalan’s involvement, there’s a truly epic twist awaiting viewers in Wayward Pines. But unlike in Twin Peaks, which made its big reveal in the middle of its second season before stumbling to an awkward and seemingly unplanned end, Wayward Pines already has a solid ending in mind. In theory, this is a brilliant storytelling model for Fox: Draw the mystery out just long enough to reel viewers in, then satisfy them with a bombshell that leads to a proper conclusion, all in a miniseries that boasts an impressive cast because the actors don’t have to be locked into six-season deals.

But Wayward Pines is airing in the doldrums of summer and will almost certainly debut to low ratings as a result. Its cast is filled with familiar faces, but not too many current stars—in fact, Howard feels like the biggest name because his work on Empire has catapulted him back into stardom. In many ways, Wayward Pines feels like a cut-rate True Detective, mimicking the style of the prestige cable miniseries but not its quality. The production is slick, and Shyamalan’s visual flourishes in the pilot help, but the writing is facile and the plotting non-existent: Most scenes feature Dillon’s character bursting into someone’s office demanding answers, and getting nothing but pleasant smiles and vague, velvety threats in return.

Like so many Twin Peaks knock-offs, Wayward Pines makes the mistake of assuming a mystery is that’s needed to propel the drama.The question remains whether viewers will want to wait several episodes for the shocking twist and deal with Dillon’s grumbling trips around town in the meantime—like so many Twin Peaks knock-offs, Wayward Pines makes the mistake of assuming a mystery is what’s needed to propel the drama. Twin Peaks’ genius was that it played like a skewed, nighttime soap opera, down to the synth score and a story that was heavy on love triangles. Twin Peaks was a high-school caper, a domestic drama, and a cop story all in one, while Wayward Pines has barely enough going on to function just as a cop story.

Still, there’s an undeniable appeal to the mystery-box approach, no matter how many times it has been abused in the past—the appeal of Lost or Alias lay in the chase, not the reward. Some miniseries have discovered this during their supposedly limited runs, the most recent example being CBS’s Under the Dome, which was supposed to be a straightforward adaptation of Stephen King’s book, but was enough of a ratings hit to get picked up for a second (and now third) season. As a result, Under the Dome’s many elements of intrigue (purple alien eggs and butterflies and time travel) have been dragged out past the point of plausibility, but while the show’s quality has plummeted, its ratings have not.

Perhaps Wayward Pines could enjoy the same success and the same long life, but it was planned as a miniseries, and Fox will almost certainly keep it that way unless it becomes a surprise phenomenon. As it is, there’s something oddly fun in following Dillon as he traipses around town in search of answers—and there’s something to be said for the fact that he finds them, eventually, and that those answers are truly bonkers. Wayward Pines isn’t the second coming of Twin Peaks, nor is it some piece of great art, but perhaps it can serve as the prototype for something better—a network miniseries that matters.

You Win, Kim Kardashian

They do not make, to my knowledge, Very Special Episodes of reality shows. If they did, though, Sunday's installment of Keeping Up With the Kardashians would certainly have qualified for the honor. In it, Kim Kardashian, splayed on an impossibly white couch as Very Special music swelled to mark the moment, looked into the eyes of her sisters and made a shocking confession: She is insecure, sometimes. And insecure about the very thing she has offered up to the public with the wan regularity of ritual sacrifice: her body.

"I cannot leave the house," Kardashian admitted, in her iconically laconic way, "without Spanx."

See alsoKapitalism, With Kim Kardashian

This was pretty much the Kardashianic equivalent of Tim Gunn showing up to a Park Avenue dinner party in sweats, or of Oscar the Grouch giving Zoloft a try: Kardashian, who regularly asks her legions of fans to consider the subtle differences between self-confidence and self-absorption, is pretty much the last person you'd ever associate with Security Spanx. But there it was: Even Kim Kardashian, according to Kim Kardashian, doubts herself. Sometimes. The proof of this was the only evidence we can ever have when it comes to reality TV's hall of convex mirrors: It was presented to us on a screen.

The Kardashian confession (Konfession?) was made even more jarring by the fact that its airing coincided with the release of the book tellingly titled, simply, Selfish—a 448-page compendium of (a portion of the) photographic images Kim has taken of herself, from 2008 to 2014. In the vague manner of Kramer's coffee table book about coffee tables, Kim's collection is both of and about selfies: It takes her (in)famous love of her own image to a logical, and also absurdist, extreme.

And yet—though critics tend to discuss Kardashian in terms as exaggerated as her hips/breasts/eyelashes, treating her as an omen of either American culture's destruction or its salvation—Selfish is decidedly small. It is a series of selfies accompanied by brief captions, the end. But the smallness is also revealing. In the book's critic-taunting title, in its sleek production value (it was published in the U.S. by Rizzoli, an imprint specializing in art collections), in the quantity of wood pulp required to produce pages slick with ink that has been coaxed into the two-dimensional form of Kardashian's face, Selfish is predicated on the idea that deflecting criticism and absorbing it tend to amount to the same thing.

The MIT researcher Ethan Zuckerman once described the “Kardashian” as a unit of unmerited fame. Selfish responds to that with page after page of Kim Kardashian's boobs.

Beauty, at least since Cleopatra began experimenting with smoky eyes, has involved wide-scale deception.You could see all that—the book's, and its author's, nihilism-via-vacuity—as a profound commentary on our times, or as yet another of Kardashian's canny acts of capitalism, or as a succinct reply to Daniel Boorstin. You could see it as further proof that our media have coaxed us into living within the context of no context (or, in this case, the Kontext of no Kontext). But what Selfish also amounts to, in its flip book-on-amphetamines framing, is a kind of diary. The photos are presented year by year, chronologically. Which means that they don't just capture what Kim Kardashian looked like on a particular day, at a particular event, with a particular sibling or friend or fellow-celebrity; they also capture her evolution—and not just from the arm candy of Paris Hilton to the arm candy of Kanye West. In Selfish, you see a woman experimenting with new hair colors and new hairstyles (nb: she advises against bangs), with outfits tight and then tighter and then even tighter, with lips from the siren-red to the vixen-nude.

In all that, you see the work that goes into making Kim Kardashian, the person, into Kim Kardashian, the icon. What Selfish depicts, more than anything else, is the labor that goes into beauty. There are the pictures of Kim sitting, patiently, with her hair in Jetsons-esque rollers. There are the pictures of her after makeup lessons from one of the many makeup artists on her payroll. There are the pictures of her post-spray-tan. There are the pictures of her face streaked with the light-deflecting and -absorbing makeup (“I’m obsessed with contour," Kim confesses, breezily) that will, after assiduous layering and blending, narrow her nose and heighten her cheeks. Kardashian is taking that most intimate of things—primping—and making it a public event.

She is blunt, and entirely unapologetic, about all of that. Kim repeatedly mentions, and praises, the team of people required to give her her "glam." (In Kardashianspeak, "glam" is most commonly used as a noun.) "Getting my hair and makeup done has become a daily routine," she writes in an early caption in Selfish. "I have become family with my glam teams." Kim is naturally beautiful—she is gorgeous, pretty much empirically—but she is repeatedly unsatisfied with the methodical madness of chromosomes. She wants more. She works for more. The selfies compiled in her book may be harbingers of arrogance, or of insecurity, or of some combination of the two; what they also are, however, is evidence of an insistent materialism, of the conviction that one’s "look" is not a fleeting thing, but rather a thing that can be made into media. (Bedroom selfies: "Right before bed but you know your makeup looks good so you have to take a pic.") This is industrial production, applied to one’s appearance. Kim is inventing, in her way, a new strain of capitalism. Its currency is the selfie.

Kim's face is a like a Duchamp urinal: In declaring itself as a kind of public art, it mocks and dares and provokes.There is, say what else you will about it, something admirable, and refreshing, in that. Because Kim is, with her preening mirror selfies, calling the culture’s bluff. Beauty, since the dawn of time and definitely since Cleopatra began experimenting with the smoky-eye look, has involved a kind of wide-scale deception. On the one hand, the logic goes, women should, if at all possible, be naturally beautiful. On the other hand, no woman, naturally, is as beautiful as she could be. So beauty becomes, like so much else in life, a complex negotiation between good luck and hard work, with the work—here’s the real rub—meant to give the illusion of the luck. (Maybe she's born with it … maybe it's Maybelline!) Makeup and hair dye and hair relaxers and hair extensions and false lashes and curling irons and nail polish and skin darkeners and skin lighteners and teeth bleach and chemical peels and microdermabrasion and eye cream and liposuction and fillers and lip plumpers—their tacit promise is that one can buy one's way into the illusion of natural beauty.

Which is also to say that the cosmetics industrial complex has been dedicated to a tension that is, if we're being fully empathetic about it, also a rather cruel paradox.

It is a paradox that Kim Kardashian, bless her contoured cheekbones, does not embrace. Her way of beauty, instead, overtly rejects the illusion of "natural"; her way of beauty is messy and smelly and absurdly labor-intensive. It strives. It requires Kim to sit in a chair for hours on end as her "glam teams" treat her face like a canvas to be painted and spackled and chiaroscuro-ed. It requires brushes, of both paint and air. It requires tools—chemicals, expertly applied—and time and patience. It requires a collection of workers.

In all that, it becomes entirely reasonable that the person who owns the canvas would want to capture the work that has been done to, and for, her. It becomes entirely fitting that Kim would, without irony or shame, heed the advice of her fellow celebrity: “You better work, bitch.” It also becomes fitting that Kim would, as she admitted to her sisters earlier this week, occasionally be plagued by insecurity. For her, confidence does not, as the unthinking ideal goes, “come from within”; it is instead the result of widespread, collective effort. It is the product of Kim’s “glam team,” yes, but it also comes from Kim’s enormous audience—from the people who watched Keeping Up With the Kardashians on Sunday night, from the people who saw the Paper magazine cover that #broketheinternet, from the people who read People. Kim is, at this point, the unlikely embodiment of Duchamp’s urinal: In declaring herself, against all common sense, as art, she mocks and dares and provokes. She rejects what came before.

And with her candor about who she is and what it takes to make her that way, she might also, against all odds, move us forward.

Snoop Dogg Reminds That Fun Can Be Forgettable

Snoop Dogg’s memory of his own career is a bit hazy. Discussing the challenge of coming up with new sounds for each album in a recent New York Times Magazine interview, he asked Jon Caramanica, “When’s the last time I had a Snoop Dogg record out?”

“About four years ago,” Caramanica replied.

“Which was it? Doggumentary? Ego Trippin’ ? Malice N Wonderland? I don’t remember.”

Related Story

Snoop Dogg, Son of Memphis Soul

To be fair to Snoop, the last few years have been complicated. In 2013 he released the reggae album Reincarnated under the recording name Snoop Lion, which was followed by Seven Days of Funk, a collaboration with Dam-Funk, released under the name Snoopzilla. After all that rebranding and 23 years of making music, whose recollection of their earlier discography wouldn’t be a bit spotty?

In that same Times interview, he explained that he packed his new album Bush with old-school funk and R&B sounds because “there’s a void for that style of music.” It was another perplexing comment, given that one of the biggest trends in pop in the past few years has been a resurgence of the style in question, in large part thanks to Pharrell Williams, the man who produced Bush. The album’s crackling guitars, infectious bass lines, and mid-tempo syncopation are of a piece with “Get Lucky,” “Blurred Lines,” and “Happy.” Snoop’s not filling a need; he’s providing more of what’s recently proven to be a hot commodity.

Call it a cash grab if you want. The man who’s famous for keeping his mind on his money and his money on his mind has remained consistent in his intentions: “I don't do it for the haters, I do it for the players,” he says on the Bush single “Peaches & Cream” before correcting himself. “Well okay, I do it for the riches.” Besides, the style he’s working in is no betrayal of the g-funk sounds that helped make him famous. Much of Bush recalls the first minute and a half of the Doggystyle touchstone “Ain’t No Fun (If the Homies Can’t Have None),” which featured a strutting funk arrangement and Nate Dogg singing before Kurupt came in with a fierce verse of rapping.

There are no such verses here. Snoop himself has described the record as “only 30 percent rap and 70 percent singing,” which is probably right. Singing, of course, is not what people come to him for; it’s his unmistakable speaking drawl that has always made him stand out. Without it, the only definably Snoopish thing about the album is its lyrical preoccupations: weed, sex, weed. “She too fly for words / And where I'm at now I'm too high for birds” kicks off his verse on the aforementioned “Peaches & Cream”; the couplet just about sums up the album with its lazy, concise statement of themes. The only somewhat interesting refinement of those themes comes on the self-explanatorily titled “Edibles,” which has vaudevillian background vocals reciting a casually sexist menu—“cupcakes … cookies … girls … chocolate … molly.”

It’s probably best to think of Snoop as emcee by the literal definition, presiding over the celebration but not actually running it.But looking for innovation or even effort here isn’t just beside the point, it’s against the point. Bush is a forget-your-problems album. “There is always a party, whether it’s a birthday party or a house-warming party or a party in a club, and we wanted to represent the party, and represent sexy,” Snoop said to The Guardian of the record’s mentality. As fits the vibe, there’s a big group of A-list collaborators—Stevie Wonder, Bootsy Collins, Gwen Stefani, T.I., Kendrick Lamar, Rick Ross—and individually, most of them put in more work than Snoop ever does.

It’s probably best to think of Snoop this time out as emcee by the literal definition, presiding over the celebration but not actually running it. The real star is Pharrell, whose gift for familiar yet distinctive arrangements with ingratiating hooks serves up a few songs that demand repeat listens: the black-light sway of “Awake,” the flashy disco of “This City,” and the surprising smoothness of “I Knew That.” In the right mood—partying, smoking, walking around a sweltering city at night—the other tracks offer a good time too. You might not remember them after they’re over, but Snoop probably doesn’t expect you, or himself, to.

'An Absolute Disastrous Mess'

Updated 5/13/15, 11:34 a.m.

At a press conference on Wednesday morning, following the derailment on an Amtrak train near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on Tuesday night, officials announced the recovery of a black box, which investigators hope will shed some light on what might have cause the train to derail.

As medical teams continue to work the crash site, Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter noted not all passengers have been accounted for. He also added that Philadelphia hospitals had treated about 200 patients overnight and that half of them had been released.

"We are heartbroken by what we've experienced here," Nutter said. "We have not experienced anything like this in modern times."

An official from the National Transportation Safety Board also spoke on Wednesday morning and was bombarded by questions about the train’s speed along with concerns about the condition of the tracks. He urged patience and explained that an analysis of the black box would yield insights into how fast the train was going and what engineers did in the moments before the crash.

“You have a lot of questions, we have a lot of questions," NTSB official Robert Sumwalt told reporters. "We intend to answer many of those questions in the next 24 to 48 hours.”

At least six people are dead and dozens more are injured after an Amtrak train derailed in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on Tuesday night. The train, which had been traveling to New York from Washington, D.C., was carrying 238 passengers and five crew members at the time of the crash.

May 12, 2015

The Twilight of American Trains

Thirty-nine minutes into his southbound ride from Wilmington, Delaware, to Washington, D.C., Joseph H. Boardman, president and CEO of Amtrak, begins to cry. We're in the dining car of a train called the Silver Star, surrounded by people eating hamburgers. The Silver Star runs from New York City to Miami in 31 hours, or five more hours than the route took in 1958, which is when our dining car was built. Boardman and I have been discussing the unfortunate fact that 45 years since its inception, the company he oversees remains a poorly funded, largely neglected ward of the state, unable to fully control its own finances or make its own decisions. I ask him, "Is this a frustrating job?"

"I guess it could be, and there are times it is," he says. "No question about that. But—" His voice begins to catch. "Sixty-six years old, I've spent my life doing this. I talked to my 80-year-old aunt this weekend, who said, 'Joe, just keep working.' Because I think about retirement." Boardman is a Republican who formerly ran the Federal Railroad Administration and was New York state's transportation commissioner; he has a bushy white mustache and an aw-shucks smile. "We've done good things," he continues. "We haven't done everything right, and I don't make all of the right decisions, and, yes, I get frustrated. But you have to stay up." A tear crawls down his left cheek.

It's easy to love trains—the model kind, the European kind, the kind whose locomotives billow with steam in black-and-white photos of the old American West. It's harder to love Amtrak, the kind we actually ride. Along with PBS and the United States Postal Service, Amtrak is perpetual fodder for libertarian think-tankers and Republican office-seekers on the prowl for government profligacy. Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush repeatedly tried to eliminate its subsidy, while Mitt Romney promised to do the same. Democrats, for their part, aren't interested in slaying Amtrak, but mostly you get the sense they just feel bad for it. "If you ever go to Japan," former Amtrak board member and rail die-hard Mike Dukakis told me, "ride the trains and weep."

It's true: Compared with the high-speed trains of Western Europe and East Asia, American passenger rail is notoriously creaky, tardy, and slow. The Acela, currently the only "high-speed" train in America, runs at an average pace of 68 miles per hour between Washington and Boston; a high-speed train from Madrid to Barcelona averages 154 miles per hour. Amtrak's most punctual trains arrive on schedule 75 percent of the time; judged by Amtrak's lax standards, Japan's bullet trains are late basically 0 percent of the time.

And those stats don't figure to improve anytime soon. While Amtrak isn't currently in danger of being killed, it also isn't likely to do more than barely survive. Last month, the House of Representatives agreed to fund Amtrak for the next four years at a rate of $1.4 billion per year. Meanwhile, the Chinese government—fair comparison or not—will be spending $128 billion this year on rail. (Thanks to the House bill, though, Amtrak passengers can look forward to a new provision allowing cats and dogs on certain trains.)

A few decades ago, news of another middling Amtrak appropriation wouldn't have warranted a second glance; passenger rail was unpopular and widely thought to be obsolete. But recently, Amtrak's popularity has actually spiked. Ridership has increased by roughly 50 percent in the past 15 years, and ridership in the Northeast Corridor stood at an all-time high in 2014. Amtrak also now accounts for 77 percent of all rail and air travel between Washington and New York, up from just 37 percent when it launched the Acela in 2000.

And yet, despite this outpouring of popular demand, despite the clear environmental benefits of rail travel, despite the fact that trains can help relieve urban congestion, despite the professed enthusiasm of the Obama administration (and especially rail fan-in-chief, Joe Biden) for high-speed trains—despite all of this, Amtrak, which runs a deficit and therefore depends on money from Washington, remains on a seemingly permanent path to mediocrity.What gives, exactly? Why can't Amtrak create any momentum for itself in the political world? Why is the United States apparently condemned to have second-rate trains?

Part of the answer, of course, is geography: Density lends itself to trains, and America is far less dense than, say, Spain or France. But this explanation isn't wholly satisfying because, even in the densest parts of the United States, intercity rail is slow or inefficient.

More From National Journal 16 Vintage Photos of Amtrak's Early Years What's the Future of Amtrak? The Long-Running Battle Over Long-Distance TrainsIn an effort to solve the riddle of American passenger rail's stubborn feebleness, I spent a couple months seeking out train obsessives around the country. During these conversations, I heard no shortage of ideas for fixing Amtrak. But perhaps the place to start is in Washington, where Amtrak clearly feels mistreated by its bosses in the federal government. "I think they lost their way a long time ago," Boardman says of Congress. "I don't understand how they don't understand. It's an absolutely necessary service, and it should be much better than it is." Later during our trip, as he shows off a brand-new luggage compartment aboard theSilver Star, he elaborates. "Maybe it's about the kid who gets bullied," he says. "Once they start bullying you, they can't stop."

IN 1970, the Nixon administration did a massive favor for freight-rail companies by relieving them of their long-standing mandate to offer passenger service, which had become unprofitable and unpopular since the advent of commercial aviation and interstate highways. Amtrak (briefly, unfortunately "RailPax") was the nationalized rail service President Nixon created to inherit those routes. Despite the long odds of it ever managing to land in the black, it was designated a "for-profit" corporation.

Anthony Haswell, a train devotee who was instrumental in Amtrak's creation—in 1967, he had founded a political lobby called the National Association of Rail Passengers, or "NARP"—suspects the for-profit designation was just a ploy to doom Amtrak down the road. "There was no question that it would probably not pay for itself," Haswell told me. "But the Nixon administration and other conservatives thought that once it was demonstrated that it wouldn't pay for itself, it would be abolished."

Amtrak did keep losing money, but Congress kept paying for it. (Haswell, disgusted with all the losing of money, eventually became a vocal critic of Amtrak.) The tension between Amtrak's for-profit mandate and money-losing reality has always dogged it. In 1997, Congress mandated that Amtrak become self-sufficient by 2002 or get liquidated. It didn't and it wasn't. That same year, a government-commissioned group called the Amtrak Reform Council floated the idea of contracting out the operation of the Northeast Corridor—the one part of Amtrak that actually makes a profit—to private bidders. This didn't happen, either. Three years later, the board of directors—who are appointed by the White House and confirmed by the Senate—fired then–Amtrak president David Gunn, an iconoclastic public-transit guru who had openly admitted the company would never be profitable. ("The only good thing about the board they put in," Gunn says today, "is that they were so incompetent, they couldn't even kill the place.")

The recurring ambivalence in Washington about Amtrak's right to exist has mostly precluded the government from drafting a plan to dramatically improve train travel. For a brief moment in 2009, however, that seemed to change. President Obama, who would promise to link 80 percent of the country to high-speed trains, used his stimulus legislation to award more than $8 billion to the cause, nearly $7 billion of which would go to California, Florida, Wisconsin, and Ohio for what were billed as bullet-train proposals. (Congress tacked on $2.1 billion more in subsequent years for high-speed rail.)

But by early 2011, it was all falling apart. Two new tea-party-backed governors in Wisconsin and Florida, Scott Walker and Rick Scott, promptly gave back the money. Ohio's new Republican governor, John Kasich, did the same. (In fairness, the proposed Ohio train, which was projected to travel between 40 and 50 mph, wasn't by any sane definition "high-speed.")

Granted, all that rejected cash has been diverted into other perfectly worthy projects that will probably make certain trains go marginally faster. For instance, a $450 million injection should help the Acela boost its top speed from 135 mph to 160 mph on one 24-mile stretch between Trenton and New York City. Dozens of other incremental projects across the country, featuring terms like "obsolete signaling systems" and "hazardous materials shipments," received cash as well.

Still, none of this represented the dramatic step into a new era of train travel that Obama had initially promised. The only surviving project that represents a major leap forward is the ambitious 220 mph Los Angeles–to–San Francisco train—and that project now faces countless challenges. Cost estimates have ballooned, construction isn't slated to finish for another 15 years, and prominent Democrats, including the state's lieutenant governor, have turned against it. Before a scheduled phone call with Jeff Morales, CEO of the California High-Speed Rail Authority (a public entity, but one that is separate from Amtrak), a public-relations person sent me a link to a number of fact-sheets. One of them claimed the project would be funded with tens of billions of federal dollars. I asked Morales how that could be, considering the Obama administration granted it just $3.3 billion. "At the time, there were some assumptions in place," he said, clarifying that the project would in fact be paid for by revenue from state bonds and California's new cap-and-trade law. "We probably ought to update that."

Countries that boast more advanced systems support their trains with public subsidies that Amtrak could only dream of.Who’s to blame for this sad state of affairs? It depends whom you ask. To conservatives, America has a second-rate train system because the government is running it. Republican Rep. John Mica of Florida, a longtime Amtrak skeptic, told me it was both a "Soviet-style" and "third-world" passenger service. If by "Soviet-style," he meant that labor costs are out of whack, it's true that a 2009 report by the Amtrak Office of Inspector General found the company's infrastructure workers to be 2.3 times more expensive annually than their European counterparts. And if by "third-world," he meant that Amtrak is often bumbling and incompetent, it's true that Acela's cars were originally built four inches too wide, preventing them from handling curves with any deftness. (The problem was eventually solved.)

To liberals, however, the problem is that the government hasn't invested nearly enough. After all, countries that boast more advanced systems support their trains with public subsidies that Amtrak could only dream of. (Britain's private rail network, for instance, received roughly $8 billion from the government last year.)

In November 2011, Robert Dove, a managing director at the Carlyle Group, the D.C.-based asset-management firm, delivered a presentation to the annual meeting of the U.S. High Speed Rail Association (USHSR), a lobbying-cum-cheerleading group formed shortly after Obama's election. Dove began his slide show with the usual embarrassing stats about America's high-speed-rail ineptitude (290 million annual high-speed-rail passengers in Japan; 3 million in America). He went on to estimate that for the Northeast Corridor alone to facilitate legitimate bullet-train travel, up to $117 billion in improvements were necessary. (Amtrak itself, in a 2012 plan that will probably never come to fruition—New York to Boston in 94 minutes!—put the number at $151 billion.) "You will not find the private sector willing to come in at the construction stage or the development stage," he warned. For that, the government would have to pick up the tab. Only at that point would you "find people like me very, very willing to come in and buy it." In other words, to get to the conservative dream of a privatized Amtrak, you would first have to pursue the liberal path of spending a massive amount of public money.

Dove's plan might be more realistic if we conceived of Amtrak as a piece of infrastructure—like a bridge or a tunnel—rather than as a for-profit corporation that can't quite turn a profit. "This is a public service," argues Andy Kunz, president of USHSR. "Our highways don't make a profit. Our airports don't make a profit. It's all paid for by the government." (Together, the Highway Trust Fund and the Federal Aviation Administration receive about 45 times what Amtrak does, through subsidies and gas taxes.)

That line of thinking isn't persuasive to everyone, evidently. In 2008, the last time a major Amtrak reauthorization was passed, Congress introduced a game-changing new rail policy: The law stipulated that, on all routes except for long-distance and Northeast Corridor trains, the states had to pay for trains' operating costs, while the feds would still handle the bulk of any needed investments. In theory, this was a good idea. Not only did it get more potential funders and political partners involved, but it was probably more fair. "Otherwise," as Railway Age contributing editor and Amtrak maven Frank Wilner puts it, "the federal government is robbing St. Petersburg to pay St. Paul, extracting a handling fee as the money flows through Washington."

The state-federal collaboration has worked out nicely in places like Virginia, where Amtrak service has improved and ridership has shot up. But in other states, it has led to services being imperiled. Several weeks ago, Indiana narrowly avoided the suspension of an Indianapolis-to-Chicago train, while state legislatures in Illinois and Oklahoma may force Amtrak to shutter certain trains. The new federal-state partnership is, on one hand, "a real area of growth," says Sean Jeans-Gail, vice president of NARP. "But it's also a threat to a lot of lines, because now you have 23 battlegrounds."

Likewise, the most recent House reauthorization bill, which has not been marked up yet by the Senate, contains a handful of subtle measures that take aim at Amtrak's less popular offerings. One mandates that all Northeast Corridor profits be funneled back into the Northeast Corridor, rather than money-losing routes. Another mandates that food service—a frequent congressional punching bag—run a profit within five years. Since it's basically impossible to make a profit on food service on long-distance trains—and impossible to run long-distance trains while starving passengers—some see this as a poison pill intended to shutter those trains. "If it really leads to food service coming off of long-distance trains," says one rail labor-union official, "that could start a death spiral."

A death spiral may be the worst-case scenario; but the best-case scenario for Amtrak these days isn't anything to get excited about, either. "We're definitely going to be in a holding pattern when it comes to Washington," says Brookings Institution transportation scholar Robert Puentes. "You see this throughout all the infrastructure and transportation funding. … We're not seeing anything but the status quo. Probably the best we can hope for is the status quo."