Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 434

May 8, 2015

What Caused a Fatal Helicopter Crash in Pakistan?

On August 17, 1988, just a few minutes after takeoff, an airplane carrying the president of Pakistan, General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, and the American ambassador to Pakistan, Arnold Raphel, suddenly crashed, killing them and 29 others. The cause of the accident has never been fully agreed upon: American investigators concluded it was a matter of mechanical failure, while the Pakistani government blamed sabotage. And there were many conspiracy theories—Zia, a military dictator, had plenty of enemies, and had killed his predecessor Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

Pakistan is again reeling from an air crash that has killed foreign envoys. Once again, the circumstances are unclear, and there are competing explanations for what happened.

Here’s what’s known: A Pakistani Air Force helicopter crashed while close to landing in Naltar, a town in the Gilgit-Baltistan area in Pakistan’s northeast, part of the Pakistani-controlled portion of the disputed Kashmir area. Among the dead were the Norwegian and Filipino ambassadors to Pakistan; the wives of the ambassadors from Malaysia and Indonesia; and two pilots and a crew member. The Dutch, Indonesian, Malaysian and Polish ambassadors survived the crash. All of them were en route to attend the inauguration of a tourism project when the helicopter crashed. According to reports, the craft hovered briefly, then crashed into a Pakistani military school on the ground.

What caused the crash is disputed. In a mirror image of the Zia crash, the Pakistani government says it was nothing more than a tragic accident. The BBC notes there has been a series of crashes with the same chopper. But the Pakistani Taliban also quickly claimed credit for taking the helicopter down, saying it was attempting to assassinate Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. Sharif was expected to travel to Naltar, but has now canceled his trip.

Related Story

"A special group of Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan had prepared a special plan to target Nawaz Sharif during his visit but he survived because he was travelling in another helicopter," a spokesman told AFP, adding that a ground-to-air missile had been used to execute the attack.

In addition to the Pakistani government’s rejection of the claim, initial reports from witnesses on the ground suggested the chopper had lost control but that there had been no explosion that would suggest an attack.

It’s true that Kashmir is not the Pakistani Taliban’s traditional territory. The group’s strong hold is on the Federally Administered Tribal Areas adjacent to Afghanistan, in northwestern Pakistan. From that base, the group has launched deadly attacks across the country. As Reuters noted, Naltar isn’t a militant stronghold, and terror groups are often eager to claim credit for attacks, whether they actually had a connection or not. Earlier this year, the Asia-Pacific publication The Diplomat reported that the Pakistani Taliban was seeking to build up its presence in Gilgit-Baltistan.

Over the last year, the Pakistani Taliban’s most notable attacks haven’t been assassinations or missile launches. In June 2014, the group laid siege to the Karachi airport, leading to 21 deaths, including 10 attackers. In December, militants attacked a school in Peshawar, killing 145 people including 132 children at a military-connected school. The attack brought the group widespread condemnation throughout Pakistan, including among figures who had been accused of sympathizing with the group or its aims. While the Peshawar attack was the bloodiest, school assaults have become something of a trademark for the Pakistani Taliban. Most famously, it shot Malala Yousafzai, a 12-year-old advocate for women’s education, in 2012. Yousafzai survived the attack and won the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize.

But attacks on political leaders aren’t exactly unusual, either. The Pakistani government blamed Baitullah Mehsud, a Pakistani Taliban leader, for the 2007 assassination of Benazir Bhutto. Bhutto—a former two-time prime minister and daughter of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Zia’s deposed nemesis—died when an attack hit her parade as she campaigned for a return to power. Then-President Pervez Musharraf was later charged with murder for failing to provide adequate security. Musharraf himself survived several assassination attempts. So did Sharif, in a previous term as prime minister.

Being a diplomat in Pakistan is dangerous, too. Four diplomats were killed in a 1995 bombing of the Egyptian embassy. Other strikes have targeted foreign diplomats, including an assault on the U.S. consulate in Peshawar. An attack on the American consulate in Karachi killed U.S. diplomat David Foy in 2006.

Still, if it were an attack, this incident would seem to fit a different profile. It’s too soon to know what effects the crash might have on Pakistan’s foreign ties, but Islamabad is working to try to project an image of strength and stability in the region, and a tourism event like the one planned for Friday is just the sort of event to do that. In a poignant note, the late Norwegian ambassador Leif Larsen praised the opportunities for Norwegian business in Pakistan in an interview published just last month in Newsweek Pakistan. “Pakistan is doing an excellent job with its operation against extremism, and we hope to see it completed,” he said.

The battle continues, but Larsen will never have the chance to see it to its end.

Damned Yankee: The Troublesome Brilliance of Alex Rodriguez

On Thursday night, one of the least holy men in baseball reached a holy number. Alex Rodriguez’s third-inning home run in New York against the Baltimore Orioles was his 661st, moving him past Willie Mays into fourth place on baseball’s all-time list. The Yankee Stadium crowd—the only one on earth that doesn’t reliably boo the player—stood and cheered the accomplishment, summoning Rodriguez from the dugout for a curtain call.

Even to the segment of the American population that prefers the nightly news to SportsCenter, the Rodriguez story should be familiar. It was only a decade ago, after all, that baseball fans and casual followers alike watched the San Francisco Giants’ Barry Bonds pass Mays, his godfather, on his own climb to the top of the home-run list. Then, as now, the ascendant slugger’s ties to performance-enhancing drugs provoked consternation; many of the arguments from the mid-aughts will be rehashed in the coming weeks, with only Rodriguez’s name and the applicable legalese substituted.

Related Story

Who Will Miss A-Rod When He's Gone?

Despite their surface similarities, though, the cases are different. Bonds played the perfect villain, feuding with teammates, snarling at the media, and whacking homers with clinical, nefarious ease. He entertained, in his way, and served as the early 21st century’s primary entrant into the catalog of Bad Baseball Men. In The New Yorker, Roger Angell likened him to Lord Voldemort, and this wasn’t entirely an insult; things can get pretty dull without a scoundrel.

Rodriguez, on the other hand, connotes less plainly. He can’t be a hero: Populist heroes tend not to sign quarter-billion dollar contracts at the age of 25, as Rodriguez did in 2000 with the Texas Rangers. They certainly don’t wither in multiple postseasons, as he did during his early years with the Yankees, or participate in multiple drug scandals, as he has: the first in 2009, when Selena Roberts brought his steroid use in the early 2000s to light, and the second in 2013, when Rodriguez became the face of the expansive Biogenesis inquiry and was eventually suspended for the entirety of the 2014 season. Rodriguez’s can’t be a redemptive case, even in a sporting climate increasingly amenable to them. His ledger of offenses is too full, his expressions of regret too difficult to parse.

Nor, though, is he a Bondsian villain. This is partly because the story isn’t new, and because baseball fans tend to reserve their heartiest vitriol for the original perpetrator, but it also owes something to the actions of Rodriguez’s antagonistic employers. The tactics used by Major League Baseball in its 2013 investigation—the purchase of purportedly stolen documents, the threat of a suspension out of keeping with the collective bargaining agreement’s penal structure—tapped a resource thought to be depleted: sympathy for Rodriguez.

This season, the Yankees’ efforts not to honor a clause in the player’s contract that grants him a $6 million bonus for reaching certain home run milestones—Mays’ number among them—scan less as a stand for the game’s integrity than as an attempt to back out of an inconvenient deal. Were it not for the amount of money remaining on his contract (three years and $60 million, including this season), they’d likely have released him altogether. One senses that Rodriguez, who’s feuded with everyone from general manager Brian Cashman to the team physicians, wouldn’t have considered it a tragedy.

How, then, to think of this player who stands at the steps of baseball immortality without any clear narrative, amenable or otherwise, in tow? How do fans place him next to the notorious Bonds, the enduring Hank Aaron, the monumental Babe Ruth, the immaculate Mays? What, after all his own sins and those of his prosecutors, is Rodriguez’s attendant adjective?

* * *

On the evening of April 17, three weeks before he broke Mays’ mark, Rodriguez played in his tenth game of the season at Tampa Bay’s Tropicana Field. He served as the Yankees’ designated hitter, this former defensive whiz with old legs and a surgically repaired hip, as he has all year and will for the foreseeable future. The fans in Tampa booed him, adhering to national habit, but Rodriguez showed no signs of caring. As he walked to the plate, white resin coated the front of his batting helmet where his hand landed to adjust it between pitches.

Rodriguez remains a beautiful hitter, even if his effectiveness isn’t what it once was. He stands at the plate easy and still, as sure of his objective as a loaded trap, his stance neither open nor closed. He keeps his black bat lifted off his shoulder, stirring the air behind his ear. Batting, he looks almost exactly how he did when he won his first Silver Slugger award as a 20-year-old Seattle Mariner in 1996. He’s a little fuller, the pocket of flesh between chin and neck a little more pronounced, but structurally and technically the same.

Batting, Rodriguez looks almost exactly like he did when he won his first Silver Slugger at the age of 20.The second pitch Rodriguez saw that evening was a high fastball from Nate Kearns. Snap. The trap sprung, the left foot lifted and dropped, and the black bat breezed through the zone and was deposited with a little flourish in the dirt. The home run traveled 471 feet to left-center, the longest shot in the majors this season. Five innings later, Rodriguez homered again, this one a hard and low liner to left field, and two innings after that, in the eighth, he flicked a single to center to drive in what would prove the winning run.

This was the kind of game that, three decades ago, would have left every fan in attendance with a good little story: an all-time great, two homers, the deciding RBI. Now, it gets a mixed reaction. In some corners of the baseball world, Rodriguez’s star turn less than a fortnight into his return season was welcome retribution against an overstepping league; in others, it was only a redundant coat in the slow painting over of baseball history by the excesses of the present.

* * *

Of the major American sports, baseball has the most insistent past. The game measures modern players by how closely and in what combinations they mimic those of yesteryear; it’s slower than any other to admit stars into rarified historical air. Some leagues rejoice when its players accomplish novel feats—Stephen Curry, this year’s NBA MVP, broke his own three-point shooting mark, and scoring records fall every winter in the pass-happy NFL—but baseball delights in reminding its contemporary talents that others have been where they are now.

I’ve never seen anyone like him is for other sports. Baseball says, He hits like Mays, he runs like a young Mickey Mantle, he has a Koufax curve. The comparisons are not only compliments; they also remind the player of his place, impressive but not singular, in its history. This historical obsession is distinguishing, and sometimes fun, but it’s also limiting. It presents baseball as fodder for some other comparative enjoyment, a means instead of an end. It writes history in real time, cleaning up before the party’s over.

Rodriguez, now, can’t be anything but a ballplayer, his connection to the generational folklore obscured.So while watching a player like Rodriguez can be a little sad, can make you pine for the days when there was no suspicion to disregard or ledger of grievances to weigh, there’s also a kind of perverse cleanliness to it. Rodriguez, now, can’t be anything but a ballplayer, his connection to the generational folklore obscured, if not severed entirely, by his missteps. He’s lost the ability to resonate in any broader context, to signify in the way we are used to—at least without the immediate intrusion of a number of counter-significances—and so all that’s left is the moving image of him on the field, his play itself. The black bat cuts the air, the runs come home, and that is all.

Maybe, then, this is how best to classify the late-career, post-scandal Alex Rodriguez, accumulator of argued-over records: as a player who snaps baseball back to the present. He eschews talk of legacy these days, instead saying, “I’m really just trying to do the best I can every at-bat.” He makes the generational comparison, the basic unit of baseball discourse, nearly impossible. This robs us of something, but it gives us something else. It gives us the chance to watch this once-excellent player, still formally if in no other ways pristine, in the moment: the rarest context of all.

1991: The Most Important Year in Pop-Music History

On June 22, 1991, Billboard announced a new album had surpassed Out of Time, by R.E.M., to become the most popular in the country. It was Niggaz4life, by N.W.A., which had debuted the previous week at number 2 and sold nearly a million copies in its first seven days. Billboard had published an album chart for 45 years, but this marked a historic week: It was the first time that a rap group claimed the top spot on the Billboard 200.

Related Story

The Neuroanatomy of Freestyle Rap

For several years, music historians have considered this, the consecration of rap on mainstream music charts, the watershed moment in modern music, marking the death of hard rock and the dawn of a period where hip-hop has merged with several genres, including country, dance, and even alt-rock, to become the modern sound of pop.

Now the theory gets some quantitative cred. New analysis from researchers in the United Kingdom, who studied the chord structure and sounds of 17,000 songs in last half-century, determined that 1991 marked the most significant revolution in the history of modern pop music. The rise of rap and hip-hop, they authors wrote, marked “the single most important event that has shaped the musical structural of the American charts."

It's something to reach back in time and take the temperature of astonished music critics in the early 1990s. Some contemporary music experts worried that hip-hop was one genre too many, and the diversity of pop music would shatter the very idea of a mainstream. David Samuels, writing in The New Republic in 1991, described rap to the magazine's readers as if it were a particularly complicated new entry in an officious encyclopedia:

"Hip-hop," the music behind the lyrics, which are "rapped," is a form of sonic bricolage with roots in "toasting," a style of making music by speaking over records. (For simplicity, I'll use the term "rap" interchangeably with "hip-hop" throughout this article.)

Why did rap's emergence seem so sudden on the charts? And why did this all happen in 1991?

After all, "Rapper's Delight," by Sugar Hill Gang, the first radio hit that contemporaries considered hip-hop, was released 12 years prior, in 1979. Rick Rubin founded Def Jam Records in 1982. Run-D.M.C. released King of Rock and performed in Live Aid in 1985, and the Beastie Boys came out with Licensed to Ill in late 1986. The first music show dedicated to rap, the perfectly-named "Yo! MTV Raps," debuted in 1989, and some historians look back on the program as the baptism of hip-hop as a mainstream genre. "Hip-hop did not just appear out of the blue [in 1991]," said Matthias Mauch, a co-author of the paper. "We see a rising trend towards less chord-orientated sound a few years earlier."

But for chart-watchers and Top 40 radio listeners, rap clung to the fringes until the early 1990s. It might have gotten its critical boost from an unlikely ally: Billboard's statistical method. (I promise this is an interesting story about methodology, perhaps the only one I know.)In the middle of the 20th century, Billboard started publishing the Hot 100, which lists the most popular songs in the country, and the Billboard 200, which does the same for albums. For decades, these lists were put together using methods that would offend even the most careless statistician, as I explained in "The Shazam Effect." Billboard had few ways to truly measure what albums were being sold in stores or played on the radio. Instead, they relied on an honor system, by asking record stores and DJs to self-report the most popular musicians of the moment. Both parties had reasons to lie, and not just because the labels would pressure radio stations and record stores to play the hand-picked hits.

Imagine, for example, that you're a record-store owner in the 1980s. You’ve just sold out of AC/DC, but you're still stocked with Bruce Springsteen albums. The honest thing to do would be to tell Billboard that AC/DC is the band of the moment. But the smart thing to do would be to tell Billboard that Bruce Springsteen is selling like crazy. That way, the Boss's album flies up the chart, which encourages fans of popular music to come back to the store and empty the shelves still holding his records.

The Hot 100 changed from a political document to a statistical register.So, for many years, Billboard wasn't a perfect mirror of American tastes. It was warped by label preferences and record-store inventories. It often over-counted songs that labels preferred (like rock) and under-counted genres they were indifferent toward (like country and rap).

But in 1991, this changed. First, Nielsen ended the record-store charade by releasing SoundScan, which used point-of-sales data from cash registers in stores. Finally, Nielsen had timely information on which albums were really selling. Around the same time, Billboard switched from trusting radio stations’ self-reports to monitoring airplay through a third party. The Hot 100 chart changed from a political document to a statistical register, honestly tracking the songs Americans were really buying and listening to.

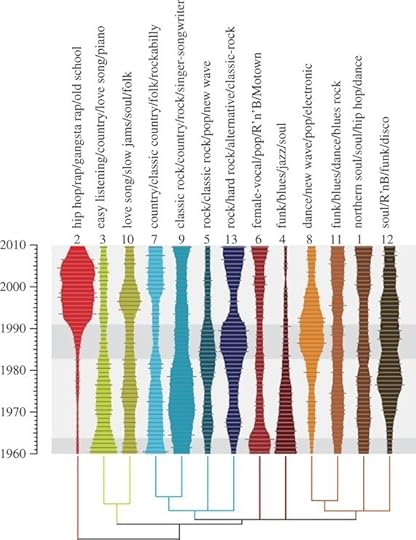

Within a few weeks, N.W.A. replaced R.E.M. on the charts. The swapping of acronyms—out with soft rock, in with hip-hop—was a harbinger. In the early 1990s, the "hip-hop/rap" genre exploded to become, by far, the most common genre of music on the Billboard Hot 100 charts for two decades (see the graphs below). These methodology changes “helped new artists, particularly in hip-hop,” said Silvio Pietroluongo, director of charts at Billboard. When British researchers studied 30-second segments of 17,000 songs in the Billboard Hot 100 between 1960 and 2010, they looked at features like chord-changes and "timbral" sounds, like drums and voices. They used this analysis to determine how certain styles and genres go into and out of fashion. For example, they discovered that the frequency of dominant-seventh chords common in jazz and the blues declined by about 75% between 1960 and 2009, while the frequency of hit songs without prominent chord structures, as in much of rap, tripled between the late 1980s and the mid-1990s. (See the graph to the right.)

When British researchers studied 30-second segments of 17,000 songs in the Billboard Hot 100 between 1960 and 2010, they looked at features like chord-changes and "timbral" sounds, like drums and voices. They used this analysis to determine how certain styles and genres go into and out of fashion. For example, they discovered that the frequency of dominant-seventh chords common in jazz and the blues declined by about 75% between 1960 and 2009, while the frequency of hit songs without prominent chord structures, as in much of rap, tripled between the late 1980s and the mid-1990s. (See the graph to the right.)

But their most dramatic discovery fits with our story: In the early 1990s, rap and hip-hop emerged as, not only a mainstream sound, but the defining genre on the Billboard charts. As you can see in this, their rather awesome graph of the ebb and flow of music styles, no other mega-genre has been so dominant for so long.

The History of Pop Music: 1960-2010

Mauch, et al

Mauch, et al One week after Billboard updated its chart methodology in 1991, the first rap album hit number one. For the next quarter-century, the British scientists found, the emergence of rap and hip-hop has proven to be more durable to the sound of pop music than even the dawn of classic rock. More than the British Invasion or the brief tyranny of 1980s drum-machines, Matthias Mauch said, 1991 was the most significant year in the history of pop music.

The Limits of Marvel's Comic-Book Storytelling

Midway through Avengers: Age of Ultron, after a debilitating battle, Marvel's titular heroic team takes shelter at a quiet farm to recover and take stock of themselves. Joss Whedon's film, the eleventh in the increasingly overwhelming "Marvel Cinematic Universe," is a bombastic experience that lays several action sequences end-to-end, with only brief pauses for humor or character development. The most significant is the farm interlude: It’s a crucial moment, because it lets the team reflect on their failings and ponder their relevance to the world, which is the film’s core theme. But it’s not the Marvel Universe’s core theme, which is why, according to Whedon, the studio “pointed a gun” at the sequence during post-production.

Related Story

The Most Joss Whedon-y Twist in Avengers: Age of Ultron

Studio interference is hardly a novel concept in Hollywood, and Whedon is hardly the first director to complain about the intersection of business and art in moviemaking. But Marvel’s approach to storytelling increasingly comes into conflict with the idea of a film being able to stand on its own, even as part of a series. Amid complaints of too many sequels, Marvel has largely dodged criticism because of the generally consistent output of its products, but while Age of Ultron has gotten decent critical notices, its seams are far easier to see. Nowhere is Marvel’s interference more obvious than a scene following the trip to the farm, where Thor the Avenger zips off to take a bath.

There’s no other way to put it. Thor, already one of the more inscrutable Avengers, decides he’d much rather be introspective on his own and jets off to a secret Asgardian cave, where he dips into a wading pool and has visions of Infinity Stones, the various multi-colored deus ex machinae that have been MacGuffins in so many Marvel movies thus far. Satisfied, he returns to the team with helpful expositional info on the stones, which are guaranteed to play a much bigger role in the third Avengers film, already earmarked for two-part release in 2018 and 2019.

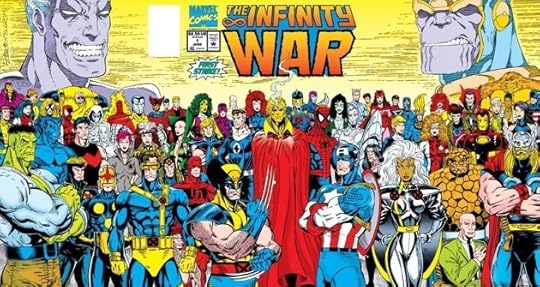

Marvel Studios

Marvel Studios It's a baffling diversion, and to hear Whedon tell it, Marvel insisted on its inclusion as part of an "unpleasant" creative battle. Speaking on the Empire Film Podcast, he said “With the cave, it really turned into: They pointed a gun to the farm’s head. They said, ‘Give us the cave or we’ll take out the farm.’” After making both Avengers movies for Marvel, Whedon is calling it quits, handing the keys over to the talented Russo Brothers for the third installment, and that's enough reason for him to finally discuss the negative side of working on a project as vast as this one.

For all of Whedon's storytelling skills (and vast capital with the "nerd community," accumulated from his TV projects Buffy, Angel, Firefly, and Dr. Horrible's Sing-Along Blog), he was never the creative point man for the Marvel Cinematic Universe. That honor goes to Kevin Feige, the producer of every film since the first installment (2008's Iron Man), who sold the comic-book company on the prospect of making a grand, interconnected series of films that aped the storytelling style it had used for generations. Each individual hero—Iron Man, Captain America, Thor, the Hulk—could have his own series of films, like an individual monthly comic-book title—and then they would all be united for an Avengers movie, which would function as a grand, unifying event.

For all of Whedon’s storytelling skills, he was never the point man for the Marvel Cinematic Universe.Marvel Comics has obeyed this creative process for generations. In 1984, editor in chief Jim Shooter devised Secret Wars, a limited series that would see all of the company's heroes united in a grand battle royale by an omnipotent alien being. Shakespeare, this was not—Secret Wars was tied into a line of action figures sold by Mattel and was quickly followed by an equally preposterous sequel. Shooter was Marvel's editor-in-chief for nine years and was notorious for the strict creative control he placed on all of its titles, and the frequent clashes he had with writers, many of whom would quit and move to rival company DC after a few years, citing creative burnout.

By all accounts, Feige is no Jim Shooter—even when Whedon gripes about creative clashes with Marvel in the Empire interview, he refers to its production team as "artists" and cites his respect for their process in keeping the grand enterprise knitted together. But Age of Ultron isn’t the first time Marvel has clashed with its creative staff. After working with the director Edgar Wright for years on an Ant-Man project (Wright was hired because he had a personal take on one of the company's more idiosyncratic heroes), Wright left the project a year ago citing "differences in vision." Given that Ant-Man was Wright's baby, one would figure that his departure would stall the project, but Marvel quickly found another director (Peyton Reed) to usher it to the screen, and the resulting product (due out in July) looks dashed-off, to say the least.

But Ant-Man had to come out this July, because Marvel can't futz with its schedule: There are nine more films in the pipeline through May 2019, each one feeding into the next, setting up a grand finale with the two-part Avengers: Infinity War, which will presumably see the celestial purple space goon Thanos (Josh Brolin) gathering the films' Infinity Gems to wage a galactic war with the Avengers. It's straight from the Marvel playbook—starting in 1991, after the Secret Wars model, the company published a multi-year series of special events, titled Infinity Gauntlet, Infinity War, and Infinity Crusade, which drew in all the company's characters. The idea was, if you were reading the Hulk, the book's plot would suddenly tie into this special event, and one would be compelled to buy it and all the related titled, just to keep abreast of all the Marvel happenings.

Marvel Comics / Ron Lim, Al Milgrom

Marvel Comics / Ron Lim, Al Milgrom This is the creative standard in the comics world: Individual heroes and team have their books, which plod along unaffected for a year, then they're all tossed together in a universe-spanning "event series" that simply has to be read to make sense of anything. In 2006's Civil War, everyone does battle over the idea of "superhero registration." In 2008's Secret Invasion, alien sleeper agents infiltrate Earth's super-teams. In 2013's Age of Ultron, the world is conquered by artificial intelligence. It's worth noting how often the Marvel films have borrowed from these comic book "events," even if it's as simple as aping a title.

But one thing the Marvel films do not have the advantage of is the agelessness of its characters. The original Avengers ensemble is getting old and expensive—Robert Downey Jr. commanded more than $40 million for what appears to be a supporting role in the coming Captain America: Civil War and that film's star, Chris Evans, has spoken of taking a break from acting after fulfilling the colossal Marvel contract he signed in 2010 (which covers six films). Downey Jr. will be 54 years old when Avengers: Infinity War Part 2 comes out in 2019, and Marvel seems to be planning for his eventual retirement, ushering in new characters to supplement the originals. Age of Ultron ends with Iron Man quitting the team and Captain America looking to train a new batch of recruits, although one imagines future twists are on the horizon.

The comics can always hit reset and return to the status quo: Readers expect Iron Man, Captain America, and Thor to be on the Avengers, even if the characters take breaks from time to time. Without casting changes, that will eventually be impossible for Marvel's movies, and within a few years Hollywood will know if it's the superhero brand, or the original cast of characters, that has guaranteed its consistent box-office returns since this grand enterprise began in 2008. Marvel's unique branded storytelling has catapulted these characters to global fame, but to keep things going, it's going to have to repeat the same trick again in a much more crowded marketplace.

The D Train: When Bromedy Meets Gay Panic

Dan Landsman is a loser among losers, a pariah even among the fellow geeks with whom he’s planning his 20th high school reunion. When, after a meeting, he asks if anyone wants to get a drink, they all demur—and then go out to a bar without him. (In case viewers miss the significance of the snub, we’re informed that they’ve done exactly this before.)

Related Story

The Unbearable Softness of Get Hard

So Dan (Jack Black) hatches a plan. After spotting a popular former classmate, Oliver Lawless (James Marsden), in a Banana Boat sunscreen commercial, he concludes that if he can persuade Oliver to attend the reunion, it will make everyone in the class want to attend, and thus render Dan a hero. The fact that this feeble premise does, in fact, come to fruition is among the smaller failures of The D Train, a thin and painfully unfunny “dark” comedy by writer-directors Jarrad Paul and Andrew Mogul.

I use quote marks because although The D Train clearly imagines itself to be a daring excavation of a soul in turmoil, it is in fact an utterly formulaic comedy save for the extreme unlikability of its protagonist and a theoretically edgy central twist that the film has absolutely no idea what to do with.

As portrayed by Black, Dan is a bottomless well of self-pity and self-absorption. Closed off as a husband (Kathryn Hahn has the thankless task of playing his wife) and negligent as a father, he does little more than fester in his insecurities. That is, until he sees the Banana Boat ad and hatches his far-fetched plan. Lying to both his wife and his boss at a small Pittsburgh consulting firm (Jeffrey Tambor, another performer too good for his material), he feigns a “work” trip to L.A. Once there, Dan tracks down Oliver, who improbably agrees to a night on the town. Following a frenzy of booze- and drug-fueled bar-hopping, Oliver and Dan.… Well, let’s just say that they find themselves in a situation Dan never anticipated. Surprising? Yes. Daring? Not nearly so much as the filmmakers seem to believe.

A moderately traumatized Dan returns to Pittsburgh a hero—Oliver has agreed to come to the reunion!—but, given his experience in L.A., a conflicted one. More festering ensues: Does Dan want Oliver close to him? Yes! He’s the golden child in whose reflected popularity Dan can bask. Does he want him far away? Also, yes! Their history is too awkward. So Dan behaves more and more unpleasantly toward everyone else in the film until the big climax at the reunion, in which he is utterly humiliated in front of his wife and classmates. But never fear: A redemptive, uplifting conclusion of Oprah-esque proportions is a mere ten minutes away.

The D Train has nothing to offer except for a stereotypical bromedy plot and a series of tedious homilies.The D Train fundamentally fails as black comedy because, apart from its central, moderately homophobic twist, it has nothing to offer except for a stereotypical bromedy plot (the nerd and the Hollywood star!) and a series of tedious homilies. (Be yourself! Popularity isn’t everything!) Unlike, say, The King of Comedy—another film about an intolerably narcissistic loser—it has no larger social context or commentary. Its out-of-left-field twist remains just that; the movie makes no effort to mine it for any deeper meaning than a kind of low-grade gay panic. The D Train isn’t smart enough to be dark; it’s merely disagreeable.

But the film fails in the opposite direction as well: caricature this broad should be, you know, funny, but there are far more cringes than laughs as the movie progresses. Marsden has his moments as Oliver: This is not the first time it’s been apparent that he’s a gifted comic actor trapped in the body of a romantic lead. But ultimately his polysexual gadabout is written as thinly as Dan’s character. (Yes, for all his looks and “fame,” at heart he too considers himself a loser: a Z-list commercial actor barely getting by in a city of genuine stars.) Up until its fulsome conclusion—which is punctuated, of course, with an anatomical joke—The D Train is as morose and ill-tempered as its protagonist. But in the movie’s case, the self-loathing is well-earned.

May 7, 2015

The Iran Bill Clears the Senate

Updated May 7 2015, 4:15 p.m.

The Senate on Thursday afternoon overwhelmingly approved legislation allowing Congress to review a potential nuclear agreement with Iran. The vote was 98-1, as lawmakers came together across party lines to assert their role in a key foreign-policy decision.

The only senator to oppose the legislation was Tom Cotton, the freshman Republican from Arkansas who has campaigned against the Obama administration’s negotiations with Iran and was blocked from offering amendments to the bill. The House is expected to take up—and likely pass—the measure in the coming weeks.

Passage of the legislation still won’t make it easy for Congress to reject the Iran deal. Under a compromise worked out by Senators Bob Corker, the Tennessee Republican, and Benjamin Cardin, a Maryland Democrat, lawmakers would have 30 days to approve, disapprove, or take no action on a final nuclear agreement. If Congress failed to act, the deal would take effect. And any vote of disapproval would be subject to a presidential veto, meaning that President Obama would need the support of just 34 senators to sustain an agreement. The White House dropped its opposition to the bill last month, and Obama is expected to sign it.

Updated May 6, 2015, 6:17 a.m.

Last week, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell turned to the members of his caucus with their eyes on the White House, and asked, "You think running for president is hard?" He didn't have to complete the thought, but it would have been: Try running the Senate.

The Kentucky Republican has been tested from the start, but the debate over legislation to give Congress a role in reviewing the Obama administration's potential nuclear agreement with Iran is showing just how complex his job can be. The bill is a rare proposal with broad bipartisan support, and its passage on Thursday marks a notable victory for lawmakers in their long-running tug-of-war with the White House over the proper balance of powers. McConnell's problem was not with Democrats but with Republican Senators Tom Cotton and Marco Rubio, among others, who wanted votes on changes to the bill that threaten the hard-fought consensus its backers have built. Call it death by amendment.

Related Story

Congress Makes Obama Back Down on Iran

Rather than indulge Cotton and Rubio, McConnell moved to end debate on the bill, cutting off the opportunity to offer amendments and expediting its passage later this week or next. It's a move that Harry Reid, the Nevada Democrat, perfected during his time as majority leader. Yet that's exactly the kind of top-down, heavy-handed maneuver that McConnell pledged to curtail if he was in charge. That he did it to prevent members of his own party from poisoning a bill makes it all the more awkward.

Just four months into his Senate career, Cotton has made a name for himself with his opposition to the Iran deal, and he tried his own procedural gambit last week to force a vote on his amendment to compel Tehran to shut down all its nuclear facilities—a certain deal-breaker. Rubio also proposed a number of amendments, but the most controversial—at least in the context of the Senate debate—sought to make Iran's recognition of Israel a necessary condition of any final nuclear accord. The vote would have been politically difficult, if not impossible, for senators of both parties to oppose, but its inclusion could have torpedoed the bill, as its supporters had already pledged to block efforts to undermine the administration's negotiations with Iran.

McConnell's strong-arming won't necessarily make it any easier to finalize a deal with Iran. Under the compromise struck by Senators Bob Corker and Ben Cardin, Congress's ability to reject a nuclear agreement would have been limited, so much so that the White House dropped its objection to the interference from Capitol Hill. Had Cotton or Rubio succeeded, the most likely casualty would have been that opportunity for congressional review, as opposed to the negotiations themselves.

The greater significance of McConnell's decision is his willingness to turn aside a pair of rising stars in his caucus.The greater significance of McConnell's decision is his willingness to turn aside a pair of rising stars in his caucus. As McConnell has learned from Speaker John Boehner, managing the more confrontational conservatives is a constant challenge for any Republican leader who hopes to pass legislation that has a chance of becoming law. Cotton has already made the most out of his aggressive moves in the Iran debate, so it's not particularly surprising that McConnell is now telling him, "Enough." Yet the Senate leader's unique challenge over the next year will be handling the four declared presidential candidates among his members (Rubio, Ted Cruz, Rand Paul, and Lindsey Graham), all of whom will seek, at one time or another, to use the Senate as a tool to advance their campaigns. McConnell is nominally backing Paul, his home state's favorite son, but his move against Rubio can be read as a signal to all four hopefuls that he is not ready to relinquish the Senate floor to their political designs.

On the whole, McConnell has had an up-and-down start to his tenure as majority leader. He waged a rather hopeless battle over immigration policy in a funding bill for the Department of Homeland Security, and he spent a month on the Republicans' first major bill—to approve the Keystone pipeline—only to watch Obama swiftly veto it. Yet McConnell has also presided over an undeniably more productive Congress so far; the Senate has approved bipartisan legislation to overhaul Medicare payments and combat human trafficking, confirmed two Obama Cabinet appointees (one after needless delay, however), and passed a Republican budget.

McConnell has also made progress on what he said would be his top priority as majority leader: "Restoring the Senate" as a functioning legislative body—one that debates, amends, and ultimately passes bills rather than bottling them up or suffocating them with filibusters. And some Democrats have acknowledged there have been improvements in the legislative climate this year, even if they come in fits and starts, and even if the Senate occasionally reverts to old habits. The Iran bill is a prime example. Supporters banded together to defeat a pair of "poison pill" amendments last week before Cotton and Rubio got in the way. McConnell spent a few days trying to find a compromise. But when that didn't pan out, he shut down debate to save the bill, and with the presidential campaign heating up, this probably won't be the last time he has to sacrifice process for substance.

The Star Wars Sequel Lucas Didn't Get to Make

George Lucas is not involved with the creation of Star Wars: The Force Awakens. When interviewed by Stephen Colbert about the forthcoming sequel, the now-retired filmmaker said "I'm excited, I have no idea what they're doing"—they being director J.J. Abrams and his team.

But according to Bruce Handy's new Vanity Fair cover story on the creation of Episode VII, Lucas at one point did have a vision for the story that the new Star Wars film would tell. By the time he sold Lucasfilm and related properties to Disney for more than $4 billion, he’d “sketched out ideas for episodes VII, VIII, and IX,” writes Handy, and had already approached Harrison Ford, Carrie Fischer, and Mark Hamill about being involved. Once the property was in Disney’s hands, though, the company and executive producer Kathleen Kennedy mostly scrapped Lucas's ideas. Why? Apparently, people involved may have been getting flashbacks to child actor Jake Matthew Lloyd’s performance in the first prequel:

[Abrams] said Lucas’s treatment had centered on very young characters—teenagers, Lucasfilm told me—which might have struck Disney executives as veering too close for comfort to The Phantom Menace and its 9-year-old Anakin Skywalker and 13-year-old Queen Amidala. “We’ve made some departures” from Lucas’s ideas, Kennedy conceded, but only in “exactly the way you would in any development process.”

Handy’s article drives home just how much The Force Awakens came out of the idea of getting to fill an entirely blank space with new Star Wars story. Luke, Han, and Leia are back and are 30 years older, but other than that, the filmmakers had to fabricate something completely fresh. The initially reluctant Abrams says this feeling of open-ended possibility is what brought him on board: “This idea of what’s happened in these past 30-something years. Where is Han Solo? What happened to Leia? Is Luke alive?”

Related Story

Star Wars: The Nostalgia Awakens

The writing process apparently was somewhat tortured, with the Little Miss Sunshine screenwriter Michael Arndt making a first attempt but ultimately failing to pull together a script in time. As of early November 2013, the studio walls and whiteboards were filled with ideas, but the actual narrative hadn't been set in place. Abrams and the Empire Strikes Back/Return of the Jedi co-writer Lawrence Kasdan took over, starting from something very close to scratch. “We didn’t have anything,” Kasdan told Handy. “There were a thousand people waiting for answers on things, and you couldn’t tell them anything except, ‘Yeah, that guy’s in it.’ That was about it. That was really all we knew.” The two men then hashed out the story in conversations as they walked around Santa Monica, New York City, London, and Paris, and kept refining the script even as production began.

Abrams keeps talking about wanting to evoke the feel of the originals rather than the prequels—in the Vanity Fair story, he says he considered putting Jar Jar Binks's bones in the background of a Force Awakens scene. But perhaps an even bigger part of the reason for the fervent fan interest in every drib and drab of info about the Star Wars sequel is that its out-of-whole-cloth nature differs fundamentally from other big-budget franchise reboots. The Marvel universe is raiding published comic books for a years-long master narrative; other based-on-previous-films films, from Abrams’s take on Star Trek to recent updates of Robocop and Terminator, often retread familiar stories and feature old characters recast with newer actors. By contrast, Star Wars, for the most part, has the potential to be an all-new vision in a familiar setting. It probably can't blow minds as thoroughly as Lucas did in 1977, but at least fans don't have to worry about spotty child-acting derailing the story that defined their own childhoods.

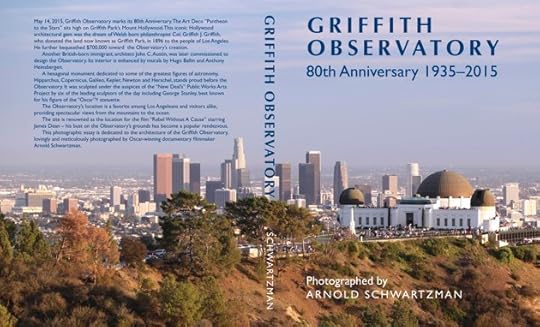

Hollywood's Griffith Observatory at 80: Still a Gateway to the Stars

The landmark Griffith Observatory sits regally atop Mount Hollywood in Los Angeles, like an acropolis on some Olympian peak. As such, it has a long history of serving as a backdrop for scenes in movies such as Rebel Without A Cause, The Terminator, The Rocketeer, and Charlie’s Angels, among others. It's captured the imaginations of many; the late Leonard “Mr. Spock” Nimoy was one of the Observatory’s keenest supporters and with his wife Susan, donated $1 million toward the Observatory's 2002 renovation. Eighty years after the Observatory first opened on May 14 ,1935, it continues to function as a bonafide laboratory, and a new book of photographs, Griffith Observatory: A Celebration of its Architectural Splendor, by the graphic designer and documentary filmmaker Arnold Schwartzman chronicles the building’s otherworldly beauty and mythic aura.

Related Story

The Observatory's construction began in 1933 under Franklin D. Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration and was based on designs by the British-born architects John Austin and Frederic M. Ashley, as well as the consultant Russell W. Porter. Austin had previously collaborated with another British architect, John Parkinson, on the late-20s design of the iconic Los Angeles City Hall.

The architects' plan of adding a number of touches of Greek revival to the contemporary Art Deco style, such as fluting from the Greek classical orders, indicates that they wanted the structure to stand as a monument for all time, Schwartzman told me. It also neatly pairs up with the Greek Theatre, he noted, which was built nearby in 1929 as an open-air auditorium with a capacity of almost 6,000 seats.

The Observatory was the dream of the Welsh philanthropist Col. Griffith J. Griffith, who also donated the Greek Theatre. After a visit to Pasadena's giant 60-inch Hale telescope, built in 1908—then the largest in the world—Griffith's reaction to looking through the lens at the sky was: "Man's sense of values ought to be revised. If all mankind could look through that telescope, it would change the world."

This view into space inspired Griffith, who made his fortune in mining and real estate, to donate a "Christmas gift" to the City of Los Angeles for the building of the Observatory and a theater on the land that he had previously donated, now known as Griffith Park. Col. Griffith died in 1919 before more than a decade before work began on the building.

For Schwartzman doing the book was also something of a dream come true. “My wife Isolde, who was responsible for the book's art production, and I would observe the sky each day, especially during the winter as there tends to be less smog,” he explained. “If there was an unusual cloud formation or a great sunset we would dash up the five miles from our home to the Observatory, sometimes to find that by the time we arrived, the optimal conditions had unfortunately changed.”

Nonetheless, for the London-born Schwartzman, the two years he spent documenting the building gave him a sense of pride. “I like to think that I had captured every prospect, aspect, and angle of the building's gleaming white surfaces," he said. "Depending on the time of day, the building and the Astronomers Monument would take on a completely different look.” His biggest surprise, he said, was “that the Observatory that I had seen featured in the film Rebel Without A Cause sixty years ago while serving in the British Army in Korea was not a studio set but the real deal.”

Arnold Schwartzman

Arnold Schwartzman  Arnold Schwartzman

Arnold Schwartzman  Arnold Schwartzman

Arnold Schwartzman  Arnold Schwartzman

Arnold Schwartzman  Arnold Schwartzman

Arnold Schwartzman  Arnold Schwartzman

Arnold Schwartzman

Spoilers: The Most Joss-Whedon-y Twist in Avengers: Age of Ultron

For fans of Joss Whedon, plenty of the writer-director’s signature flourishes were on display in his latest foray into superhero blockbusterdom, The Avengers: Age of Ultron—the humorous banter, the sudden reversals, the clever callbacks. (That scene with the Vision and Thor’s hammer offered perhaps the movie’s second-best moment, behind only … the initial scene with the hammer.)

But in the run-up to the film, the most nervously anticipated Whedon trope was the filmmaker’s longstanding penchant for killing off characters to whom viewers had grown attached.

Related Story

Avengers: Age of Ultron Is Too Much of a Good Thing

This compulsion dates all the way back to the shocking death of Jenny Calendar in the second season of Buffy the Vampire Slayer in 1998. Over the years, a couple of particular sub-variations on the theme have become evident. First, Whedon enjoys killing off characters on the cusp of a long-awaited romantic fulfillment: Ms. Calendar and Tara on Buffy; Fred (who died in Wesley’s arms) and Wesley (who, perversely, died episodes later in Fred’s arms) on Angel; Penny in Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog, etc.

Second, he has a fondness for killing characters off in indiscriminate, even accidental fashion (a stray bullet, a malfunctioning Death Ray), often after a principal battle appears already to have been won: Tara (again); Penny (again); Wash in Serenity.

So the question of whether Whedon would try to kill off an Avenger—and whether Marvel would allow him to do so—has been in the air ever since a sequel to the original movie was announced. (Whedon did kill Agent Coulson—temporarily, as it turned out—in the first Avengers, but the death took place in the middle of the film and was unconnected to any romance.) Cinemablend even took a reader poll on who would be the most likely casualty.

The major franchise characters were generally presumed to be off the table (though Captain America and Iron Man do have potential successors in place to eventually take up the shield and helmet in Bucky Barnes—possibly also Sam Wilson—and James Rhodes, respectively). So speculation tended to fall on two non-franchise characters, Black Widow and Hawkeye. The first possibility, in particular, picked up steam after the trailer for Age of Ultron was released.

If there's anything Whedon likes to do more than kill off characters, it's confound expectations of whom, exactly, he's going to kill off.Now, Joss Whedon was obviously aware of all this speculation, and if there’s anything he likes to do more than to kill off characters, it’s to confound viewers’ expectations of whom, exactly, he’s going to kill off. (To this day, I am convinced that Whedon intended for Serenity viewers to worry that Kaylee would be his chosen victim—sweet, helpless, Fred-like Kaylee, right on the verge of having her crush on Simon requited—and toyed with us by killing Wash instead.)

So what does Whedon do in Age of Ultron? (Again, big-time spoilers ahead. Get out if you don’t know what’s coming.)

Well, he supplies Hawkeye with a secret, loving, pregnant(!) wife and two adorable kids hidden in a bucolic paradise far away from the carnage. (This is roughly akin to being the likable cop partner who’s two days away from retirement.) He also introduces both a tragic backstory and a budding romance for Black Widow. (This is akin to being the likable minority cop partner who’s two days away from retirement.) The imminent demise of one or both characters could hardly have been more aggressively advertised if it had been announced in a screen crawl. (It’s probably worth noting here that Whedon says Marvel execs didn’t like the family-man-Hawkeye subplot and that in order to keep it he had to make compromises elsewhere.)

Fast-forward to the climactic battle with Ultron and his robo-minions. Stranded on floating hunk of Eastern European terrain, Black Widow notes to Captain America that she’s willing to die if need be: “There’s worse ways to go. Where else am I going to get a view like this?” Likewise, Hawkeye gives the Scarlet Witch a heartfelt, inspirational speech about the necessity of courage in the face of desperate odds. None of this is accidental.

The heroes all do their hero thing, and Ultron finally appears to be defeated, shattered beyond repair and hurled off the floating island to his presumed death. Hurray! But as no one knows better than Hoban Washburne, in a Joss Whedon movie it’s never too late to seize death from the jaws of victory. A battered but still-functional Ultron improbably finds himself a quinjet, and pilots it back for one last round of trouble.

Each character is one step removed from rescuing a kitten while holding hands with someone they love.What is Black Widow busy doing when Ultron returns? On the assumption that the fight is basically over, she is gently calming the Hulk down so that he will revert to Bruce Banner, the man she loves. What is Hawkeye doing? He is rescuing the very last local trapped on the floating island, a little boy whose mom lost track of him in the market. I mean seriously. Each character is one step removed from rescuing a kitten trapped in a tree while holding hands for the first time with someone they’ve secretly loved since childhood.

So when Ultron strafes the island, whom does he target? If you haven’t been paying attention, he shoots at exactly two characters: Black Widow (OMG! She’s dead!) and then Hawkeye (No, wait! He’s dead!). The truth, of course, is that Whedon has been toying with us all along. Black Widow turns out to have been protected by the Hulk, and Quicksilver takes the bullets intended for Hawkeye, expiring with yet another callback on his lips, this one to the first line shared between the two characters in the movie’s opening scene.

A few final notes: Who knows what Marvel would and would not have allowed Whedon to do, character-death-wise. But if he’d had Ultron kill Black Widow as Hulk reverted to Banner-dom, so that we could watch the latter’s helpless horror and despair as he cradled his dead or dying love in his arms, it would probably have been the most Whedon-y moment of all time—for good, ill, or (quite possibly) both. By contrast, one assumes that Marvel was unperturbed by the death of Quicksilver, a newly introduced character saddled with movie-rights issues, who was probably never going to top the “Time in a Bottle” scene that Bryan Singer and Fox afforded him in X-Men: Days of Future Past. (Though Whedon did shoot a version of his movie in which Quicksilver survived his wounds, just in case.) Regardless, Whedon ended up with arguably the best of all worlds: killing off a character whose death will not overly enrage the Marvel fan base, while once again toying with—and ultimately confounding—the expectations of his own longtime viewers.

May 6, 2015

The Hamburglar Is Dead; Long Live the Hamburglar

Once upon a time, the Hamburglar was a teeny tiny scoundrel with red hair and a cheeky snaggle tooth, so winning in his features that no one minded when he insisted on trying to steal all the hamburgers, all the time. With his black Zorro hat, his stripy prison clothes, and his impish grin, it was easy to forget that the Hamburglar was just another down-on-his-luck American reduced to robbing others to feed his insatiable addiction. Presumably things have been hard for him, because the last time he surfaced was in 2002, when he appeared in an advertisement with the tennis stars Venus and Serena Williams.

Related Story

The New McDonald's Mascot Is Terrifying

Not any more. The lovable McDonald’s mascot of yore has grown up. New images released by the fast-food chain depict the Hamburglar as a grown man wearing a fedora and macintosh atop a black-and-white t shirt. He still has a mask, but his face now also sports a good half-inch of designer stubble. "We felt it was time to debut a new look for the Hamburglar after he’s been out of the public eye all these years,” Joel Yashinsky, McDonald’s vice president for marketing, told Mashable. “He’s had some time to grow up a bit and has been busy raising a family in the suburbs and his look has evolved over time.”

“Evolved” is one way of putting it. Not since Mary Kate and Ashley grew from tweenage VHS stars to the high priestesses of haute couture have childhood icons had such a radical transformation. The old Hamburglar was maybe four foot two, with a giant cartoonish head, two sticky-out ears, and an endearing mop of auburn hair, a bit like Dennis the Menace. The new Hamburglar looks like one of the creepier models wearing a “Sexy Hamburglar” outfit on a Halloween costume website. The Artful Dodger has become an out-of-work actor, and with him, childhood innocence has been dispelled faster than the average fast-food consumer can say, “Robble Robble.”

It’s important to note, however, that this isn’t the first time the Hamburglar’s been made over. Before he was the miniature criminal with the innocent expression, he was a hideous creature of normal size with two teeth, a hook nose, and a cape, who was inexplicably known as “the Lone Jogger.” Like the later Hamburglar, he was non-verbal, but instead of articulating nonsense words he made a kind of gargling sound, like a bathtub whose water was being drained. In this commercial from the 1970s, he doesn’t appear to jog so much as sweep into a McDonald’s, grab a tray of breakfast, and spread his cape victoriously to show off his “Lone Jogger” shirt, a bit like a flasher.

YouTube

YouTube It wasn’t until 1985 that (presumably) someone in the McDonald’s marketing department discovered this character was actually enormously disturbing, at which point the Hamburglar was reinvented to be more child-friendly. But judging by the recent revival, the anxiety surrounding a fast-food behemoth deliberately marketing its products to children has led the company to target a much more profitable demographic: nostalgic adults. Like us, the Hamburglar has grown up. He’s abandoned his city condo for a house in the sticks, but he hasn’t quite left his love for burgers behind (there’s one on his watch). The most unrealistic part of all of this is that the prospect of a new McDonald’s product (a Sirloin Third Pound Burger) appears to be more enticing to this hamburger aficionado than the fresh-made patties he’s grilling in his own front yard.

Wait, is this who we think it is??! https://t.co/rc9xhQrAUi

— McDonald's (@McDonalds) May 6, 2015

What’s next for McDonald’s and its $2 billion annual marketing budget? Will Grimace discover Atkins and shed 70 percent of his excess body weight, emerging sleeker in his purple frame, like an eggplant emoji? Will Mayor McCheese enter the Republican presidential race? Will Ronald McDonald ever not be disturbing? As offbeat as the decision to make the Hamburglar (a) a parent and (b) human might be, it’s important to remember that even a 40-year-old with a hamburger on his watch is less disturbing than 99 percent of the characters McDonald’s has used to sell its hamburgers over the years.

Flickr: NathaninSanDiego

Flickr: NathaninSanDiego

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower