Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 435

May 5, 2015

With Brands, What Exactly Is Mad Men Selling?

On Sunday's episode of Mad Men, "Lost Horizon," the former SC&P partner and account executive Joan Harris (played by Christina Hendricks) faced more of the odious sexual harassment and discrimination the character's endured over the years. This time, the executives belittling her judgment, ignoring her opinions, and urging her to sleep with them were executives working at her new employer, the advertising firm McCann Erickson.

McCann Worldwide, as the firm is known today, reacted with a series of playful tweets, cut with a snarky defensiveness that indicated the company had taken the episode at least a little personally.

We have to go wash our hands. #MadMen

— McCann (@McCann_WW) May 4, 2015

Hi @eshire. What do you want to know? We’re kinda busy subjugating our new staff.

— McCann (@McCann_WW) May 4, 2015

@eshire People seem to appreciate we can make villainade out of villainy. #MadMen

— McCann (@McCann_WW) May 4, 2015

While some brands like Heineken have actually paid for product placement on the show, others like McCann have had to hold their breath and pray Mad Men won't invent a closeted drunkard CEO for them (Lucky Strike); use their product in the backdrop of a suicide attempt (Jaguar); or remind viewers of how they contributed to civilian deaths (American Airlines and Dow Chemical). For brands, a Mad Men mention, or even a full storyline, could summon either excitement or dread; and the way companies react to their portrayal reveals how they're often willing to let themselves be seduced by the show's nostalgic sheen. If the depiction is kind or neutral, it's free advertising. If it's ugly, brands have the excuse that it's just fiction. But either way, leaning into the publicity hints at a willingness to ignore Mad Men's series-long effort to lay bare the hollowness of so many popular products, and the cynical attempts by marketers to tie them inextricably to the American Dream.

Related Story

Of course, for some brands, the exposure is innocuous, even salutary: The headphone-maker Koss seized on its unexpected Mad Men appearance with a brief marketing blitz, and no one, fictional or otherwise, got hurt. (Let's also not forget the slew of fake or already-dead companies that have made their way into the show: Burger Chef, Topaz, Sugarberry Ham, Menken's Department Store, Secor Laxatives). But McCann couldn't back away from its portrayal so easily: For the ad agency, the sexism that pervades the higher rungs of large companies can't be written off simply as a plot device—nor can it be necessarily corralled by claims that the show belongs to a different time.

Perhaps the murkiest and highest-profile instance of Mad Men tying a storyline to a brand involves Jaguar. In a pivotal season-five episode, an executive from the company coerced Joan into sleeping with him to get the account, and the partner Lane Pryce tried and failed to kill himself in one of the cars, which wouldn't start. Initially, the vice president of brand development for Jaguar, David Pryor, told AdAge that the company was "fairly surprised at the turn of events" with regards to Joan, and that "obviously [the portrayal] was kind of tainted," but that ultimately the company was "confident that people know [the sleazy Jaguar executive was] a fictional character." Later, in a post for Jalopnik, Pryor and a colleague described how they felt watching the episode: They tried to "ignore" Joan's storyline, which inspired "revulsion," and they were sad about Lane's death because "it was Lane who first brought Jaguar to SCDP." All this dissonance and ambivalence aside, the company's verdict was simple: "Our job is to promote the desirability of our cars, not the morality of our fictional executives." Which, fair enough.

But brands are often willing to embrace that fictitiousness when it's convenient. Hershey's was thoroughly delighted by its role in the show's season-six finale, even going so far as to send the show's creator Matthew Weiner chocolate. When Vanity Fair asked what Hershey thought about being linked with Don's childhood memories of living in a brothel, the company said it wasn't concerned—"Obviously we know that this is a fictitious television show set in the 1960s"—but that it found the episode otherwise "wonderful, organic," and "memorable."

Some have complained that the show's nostalgic feel can have a tempering or softening effect on otherwise bad behavior like alcoholism, adultery, sexism, or racism. As a result, it can be easy to take the brand exposure at face value, and to overlook how the show critiques consumerism and the illusory nature of advertising, as well as how it often works its way into the uncomfortable corners of corporate (and American) history. But if Mad Men only reflected on the pitfalls of the past, it would still be at most just a "good" show, despite its superb writing, acting, production design, and cinematography. It's a great show in part because, in talking about the past, it illuminates the flaws of today.

Mad Men is a show that has little respect for things, products, stuff, and images.Which brings us back to Joan's McCann storyline from "Lost Horizon." The slightly embarrassed tenor of the company's tweets in response is understandable—no one wants to be associated with the kind of ruthless chauvinism on display in that episode.

But before Sunday, McCann didn't seem to terribly mind the attention Mad Men sent its way. It's certainly not as ubiquitous a brand in the way Hershey's, Coca-Cola, Heinz, American Airlines, or Playtex are, so the average viewer likely wouldn't be curious how the firm would respond to its portrayal. Yet the firm's proactive efforts to gamely play along on Twitter, to make villainade out of the fruit of villainy, paid off in at least one way: Since the show returned for its final stretch April 5, McCann's online mentions/impressions rose 46 percent, according to data reported by AdWeek. But being framed as a subsidiary-swallowing behemoth is preferable to being painted as a claustrophobic den of sexists. Even if the latter portrayal was fake in its specifics, it had authenticity in a broader sense, pointing an uncomfortable neon-lit arrow at the persistent issues of sexual harassment and gender discrimination in the workplace.

Not to mention the advertising industry's own ongoing gender-makeup problem. As FastCompany reported in 2013, while 80 percent of women control consumer spending, just 3 percent of creative directors are women. Just five of the 19 individuals listed on McCann's leadership page are women. With all this in mind, the awkwardly coexisting narratives of, "Well, it's just a story," and, "Thanks for the free publicity," collapse.

Against that canvas, does it truly make sense to embrace the Mad Men spotlight? In purely practical terms, probably, according to Kelly Cutrone of the PR firm People's Revolution:

Does having your products on a popular TV show in a subliminal or obvious way help sell them? Yes, it does. Does it increase awareness and comfort with the product — do viewers feel psychologically closer? Yes, they do.

Still, Mad Men is a show that has little respect for things, products, stuff, and images. It's a show deeply interested in exposing how desire is manufactured, how much effort goes into the appearance of effortlessness, how more can be less, and how the person who has everything can be left with nothing. Though there's always a degree of credibility to be wrung from self-awareness and self-deprecation, these themes are hardly great slogan-makers.

Among the show's most enduring images is the silhouette of a man—the guy who once said happiness "is the moment before you need more happiness" and that "people want to be told what to do so badly that they'll listen to anyone"—falling helplessly past a collage of images promising that fulfillment is just one purchase away. It makes sense that brands and companies like McCann would try to make the most of a Mad Men cameo, however risky. But in light of the overarching message from the show's seven seasons, it's hard not to conclude that they might be missing the point.

Enough of Silly Love Songs

In music, in fairy tales, in legends, the most famous loves are the big loves. The recent deaths of soul singers Percy Sledge and Bill E. King have offered as good a reminder of this as any. In their greatest songs, love leads people to sleep in the rain; love protects when the mountains crumble down; love transforms space and time.

Related Story

The Bittersweet New Maturity of Mumford & Sons

But there's just as rich a cultural tradition of not-so-epic love songs, opting for plain language and hedged declarations and a negotiator's precision. Three rock albums out this week work in this mode, offering examples of what makes a good relationship-real-talk song and what makes a generic one. Mumford & Sons, Best Coast, and My Morning Jacket all aim to portray feelings that fall somewhere between total infatuation and absolute heartbreak, an emotional zone that's not very cinematic but that certainly can be relatable and, occasionally, devastating.

Mumford & Sons have made lots of money, a few celebrity fans, and a contingent of dedicated haters over the past six years by becoming the figureheads for the new Americana movement, a fact widely seen as ironic given that they’re British. But after two albums of strummy hoedowns with vaguely religious lyrical themes, they’ve ditched their banjos and started trashtalking the old-timey outfits they used to wear on stage. The band’s new, sleek, modern-rock sound has drawn comparisons to the likes of U2 and Coldplay, but those band names give a false impression of big, goopy emotions. Mumford 2.0 is colder and more remote than that.

The real point of comparison is, improbably, Brooklyn indie mopers The National. The members of Mumford have talked about their obsession with that band, and The National’s guitarist, Aaron Dessner, helped record their third full-length, Wilder Mind. Accordingly, the album aims for a kind of muffled momentum, driven by drums and bass locking into machine-like grooves, guitars often indistinguishable from synths, and singer Marcus Mumford more often opting for a low tremble than the festival-friendly howls he'd previously been known for. The lyrics, too, ape The National in their cryptic introspection, with a few turns of phrase directly recalling Matt Berninger's. The band has said the album is largely autobiographical and features their "very first love songs," which indicates that at least one member is going through a period in a relationship when passions start to dim, old promises are tested, and it gets harder to express an unconditional anything about the other person.

The opener, “Thompson Square Park,” is a kiss-off made to sound inevitable, a lament to life getting in the way of a relationship. “No flame burns forever / You and I both know this all too well,” Mumford sings in the chorus. Later, he yearns for the simplicity portrayed by so many other love songs—“If only things were black and white / Cause I just want to hold you tight.” If those lines sound a bit platitudinal, they still stand out among the album's many vague mentions of monsters and beasts, city lights and tall walls. The National makes the mix of cryptic metaphor and direct emotional confession work with vivid, specific turns of phrase; Mumford & Sons aren't capable of that, though. When they opt for the big, singalong choruses and climaxes that characterized their earlier hits, something goes wrong—the message undermines the music. The only track where everything seems in harmony is "Ditmas," whose shanty-like melody recalls the band's old songs, and whose words work as a warning against anyone considering breaking up with Mumford & Sons for their new sound: "Don't tell me that I've changed because that's not the truth."

The California duo Best Coast hasn't undergone quite such a drastic sonic and emotional makeover for its third and most polished full-length, California Nights. Indeed, this album will only cement Best Coast’s reputation as the platonic ideal of a group where “all the songs sound the same.” The songs are simple but lushly rendered surf-rock tropes in short bursts, featuring singer Bethany Constantino's AA/BB rhymes about romantic longing. And the music's radical straightforwardness is what makes the band so pleasing to listen to. There’s no mystery to be solved; you can plug directly into Costentino’s wavelength, so long as the music's bubblegum traits and singleminded focus on certain topics doesn’t annoy you.

This time out, Costentino’s obsessing over end of a relationship—or rather, for the most part, the time after the end of a relationship. Where once she pined for someone she couldn’t have—“I wish he was my boyfriend” went the refrain that opened the band’s 2010 debut—California Nights has her trying to sort through where a relationship went wrong, and cobbling together some emotional acceptance. It's most moving on the second track, “Fine Without You,” where Costentino seems to be talking to herself about a boyfriend who’s moved on to another girl. “I know it's hard to understand / You've got to let it go / The situation is out of your hands,” she sings, and the rumbling power-pop backing sounds as insistent as the sentiment. A couple other songs are a bit more on the doting-eternal-love side, but always sneak in a note of melancholy. "I know it's love that's got me feeling ok," she sings in one surging chorus, right after referencing a doctor prescribing her antidepressants.

My Morning Jacket’s seventh album is, like all of the band's albums, more about the human race than about actual humans. The classic-rock reinvigorators aim for epic on The Waterfall, with multi-part songs that mash prettiness, jamming, and openhearted hooks that largely meditate on faith, existence, and nature. But a few songs have a smaller scope. "They are influenced by specific situations, but I'd rather not talk about it, because I want love in my life," singer Jim James told Rolling Stone about some of the lyrics. "In recent years, I've been trying to figure out, 'What have I done wrong in every relationship I've been in until now?' and tried to make them better."

It’s not clear that he’s figured out what his problem is. But he has figured out that when things start going wrong, it’s better to state it plainly rather than ignore it altogether or craft euphemisms about it. “Thin Line,” rides a woozy groove that dramatizes the wariness of the words, with James doing his best Marvin Gaye impression as he sings “It’s a thin line / Between lovin’ and wasting my time.” On “Big Decisions,” he tells of being stuck in stagnant codependency, with the other party not willing to do something about it. “Do I have to make all the big decisions for you,” he asks over stop-start guitars, and it doesn't come across as caustic as it might seem. Instead, it’s a pedal-steel-accompanied singalong, a moment of honesty about people coming apart that's meant to bring people together.

But perhaps the most powerful relationship song on any of these albums is "Get the Point," an explicit attempt to strip away the artifice, the metaphors, the philosophizing that normally accompanies love songs. “Well we talked and talked and carried on from sundown to the break of dawn,” James gently sings over acoustic picking, before indicating that all the talking became useless. He wishes the person he's singing to "all the love in this world and beyond," but his main sentiment is not so easy to take. “I guess you get the point: Our love is done.” Message received.

John Wick 2 and the Magic of the Surprise Sequel

Everyone's heard the complaints that Hollywood has become a sequel-making machine, in recent years, eager to greenlight any franchise entry that might seem vaguely recognizable to movie-goers. But amidst the cinematic universes and nine-picture contracts for actors, it’s easy to lose sight of the humble, unplanned sequel. In case you’re wondering what that means, a perfect example cropped up this week: John Wick, a low-budget, R-rated action movie starring Keanu Reeves that made a small splash in 2014, is reportedly getting a follow-up. This is neither a preordained, big-budget installment nor a cheap direct-to-DVD knock-off: The star and directors are simply returning to tell another story, an achievement they earned on merit alone.

Related Story

John Wick: An Idiot Killed His Puppy and Now Everyone Must Die

For an action flick in the Liam Neeson revenge-thriller mold, John Wick was surprisingly well-received. It did decent business at the box office, but nothing extraordinary, opening at the #2 spot in October (behind the already-forgotten Ouija) and earning $78 million worldwide on a $20 million budget. That's a solid take, but for the sake of context, John Wick was the 77th highest-earning film (domestic) of 2014, making just a smidge more than the Best Picture Oscar-winner Birdman. There’s nothing there to indicate the necessity of a sequel, even with its comparably low budget.

But considering that it’s a film about a retired hitman who murders hundreds of people in a revenge mission after his dog is killed, John Wick had the je ne sais quoi that a film with 10 times its budget dreams of—the kind of idiosyncratic attention to detail that spurs a cult following long after its theatrical run. The movie came out on home media and video-on-demand in February and unsurprisingly topped those charts, indicating strong word-of-mouth among action-movie fans who've recently been starved of the kind of fluid, beautifully shot set pieces John Wick boasts by the dozen.

The film's appeal is in the surprise of how fun it is. The dialogue is plodding and the plot is so obviously telegraphed that the characters barely need to speak, but there’s a dreamlike quality to the New York underworld Wick navigates, down to the mysterious gold coins used as currency in the hotel of assassins he books himself into. The action, a seamless mix of kung-fu and point-blank gun violence, feels original, even if it’s borrowing from Reeves’ greatest hits.

John Wick had the je ne sais quoi a film with 10 times its budget dreams of.How could one possibly be surprised by a John Wick 2? It’s an ambitious challenge, but there are worse ways for Hollywood to try and get lightning to strike twice. John Wick had a very strange creative team: Reeves took the script to Chad Stahelski and David Leitch, his stunt doubles from The Matrix films, hoping they would choreograph and direct despite never having done the latter before. Both will return for the sequel, and should be hard at work cooking up even more glorious stunts for Reeves to tumble through.

The surprise sequel almost always comes for a modestly budgeted film that exceeded expectations, and the best of them are ambitious, even if they don’t quite succeed. The clever 1984 horror-thriller Gremlins begat the postmodern touchstone Gremlins 2: The New Batch, in which director Joe Dante ran headfirst at audience expectations by making an unapologetically funny satire of sequel-making that gleefully broke the fourth wall. The same happened with Barry Sonnenfeld’s The Addams Family, which took everything that worked about the 1991 surprise hit—the anachronistic charm of its stars—and dialed it up for the darkly slapstick sequel Addams Family Values. Perhaps more relevant to Wick are the great surprise action sequels like Crank: High Voltage or Hellboy: The Golden Army; follow-ups that tapped into what appealed about their predecessors while shedding everything that didn’t work.

There’s every indication that John Wick could go the other way, as has happened with the moribund Taken franchise or every flagging attempt to revive Die Hard. Sequels usually demand repetition of whatever formula worked, and for John Wick, that’s Keanu Reeves shooting villains—the studio will make a quick buck on name recognition alone before script quality or originality enters the picture. But in an industry that's currently making more than 120 sequels or franchise entries for audiences to consume in the coming decade, it’s important not to lose sight of the diamonds in that vast rough. May John Wick remain on the side of good as he approaches his most daunting challenge yet: keeping things fresh.

What Memes May Come: The Perfect Ugliness of the Met Gala

Did you see Sarah Jessica Parker's headthing at the Met Gala? The one that called to mind a flame emoji/a series of Q-tips/Aku/the 2008 Olympics/Sideshow Bob?

Related Story

Fashion's Pointless Cultural Appropriation Debate

The Met Gala—full name: the Metropolitan Museum Costume Institute Gala—is sometimes called “the fashion Oscars” or the “Oscars of the East Coast.” But it is, in its spirit, less like an awards show than an elaborate costume party—“Final Fantasy cosplay,” @papapishi put it, “for rich people.” Each Gala, which doubles as a fundraiser for the museum—the money the event raises traditionally provides the entire annual budget of the museum’s Costume Institute—has a theme associated with the Met exhibit that opens the same night. (In 2008, it was "Superheroes: Fashion and Fantasy"; in 2013, it was "Punk: Chaos to Couture.") That theme doubles as a kind of sartorial framework for the 700 or so celebrities and other Important and/or Rich People who attend it: They’re meant to pay tribute to the theme through their clothing. You could equate the whole thing, perhaps, to the challenges on Project Runway, or to the secret ingredients on Iron Chef.

And since people attend the Met Gala not so much to see as to be seen, they’re meant to be as creative—and, more to the point, as interesting, and as weird, and as shocking—as possible with their outfits. Schlock and awe. Looking pretty, at this event, is pretty much beside the point.

The theme of last night’s event was “China: Through the Looking Glass.” Which is how it came to be that SJP, known both for her quirky headpieces and for her generally daring approach to fashion, donned a fire-themed headpiece to walk the red carpet with Bravo's Andy Cohen.

Aku gets bonus points for versatility RT @JChiron18: Who wore it better? pic.twitter.com/Pn9Q7moXaF

— Dionysus (@TheBlackHermit) May 4, 2015

who wore it best? pic.twitter.com/W72BQUeT7k

— L.A.S (@SartoriallyInc) May 4, 2015

SJP: "AFTER 10,000 YEARS I'M FREEE!" #MetGala pic.twitter.com/DsGkMCnZRp

— Jian DeLeon (@jiandeleon) May 4, 2015

Anyone else think Sarah Jessica Parker looked like Heat Miser at the Met Gala? Just me? Aight. pic.twitter.com/PI8Joa5jNN

— abby (@MissAbbyMcLain) May 4, 2015

This is also how it came to be that Rihanna walked the same red carpet in a yellow, furry, be-trained gown that reminded many of an omelette. And that Anne Hathaway did so in a Jedi-esque hood that resembled liquid gold. And that Vogue's Grace Coddington did so in floral pajamas.

Which is all, for the most part, just as it should be. Playfulness and absurdity, the pretensions of the word "gala" aside, are baked into the annual Metropolitan Museum Costume Institute affair. In 2014, Anna Wintour—a chair of the event, and its unofficial spirit animal—raised ticket prices for those not on the official guest list by $10,000, to $25,000 apiece. This was meant, in part, to increase the prestige of the proceedings. But, on that other hand, what is exclusivity without publicity? This year, the gala was filmed as part of a future Andrew Rossi documentary. It was recorded by 225 event-approved photographers and reporters (among them official Snapchatters); it offered livestreams; The Cut had a live blog and a Periscope stream of its happenings.

The Met Gala may celebrate the varying exclusivities of wealth and celebrity; as a media event, though, it is all about that most democratic of things: dirty, craven spectacle.

As a media event, the Met Gala is all about that most democratic of things: dirty, craven spectacle.There is something, despite and because of all the showmanship, wonderfully honest about all that. This is fashion, stripped down to its highest and lowest propositions: clothing as art, clothing as symbol, clothing as statement. This is fashion presented not as a practical concern, or even as an aesthetic one, but as a kind of philosophy. Rihanna's dress, and SJP's hat trick, and Solange's space-operatic mini-dress—they are what happens when the haughtiest of haute couture collides with the one percent: instead of "quiet luxurians," you get outfits that luxuriate in their very loudness. The looks that walked the red carpet last night were not, for the most part, pretty. And the ones that were pretty were also supremely boring. (“Cheer up, JLaw,” People tweeted to a celeb who had bored the magazine with her beauty.) The goal here is statement-making, “whoa”-inducing, meme-making both literal and figurative; beauty, in general, gets in the way of all that.

Compare all that to the "West Coast Oscars": the Oscars themselves. The winter awards show, which many people watch for the same reason they watch the Met Gala—the clothes—has the pretense of actually being about something. The Met Gala, as a media event, has no pretense to be anything but itself. It's all about the clothes. It's all about the red carpet. Sure, there's a dinner. Sure, there's entertainment. Sure, the thing is nominally a fundraiser. But the point here is the fashion, and there is something at once callow and wonderfully refreshing about that. The Met Gala's red carpet may host a lot of ugliness. But at least it's an honest kind of ugliness.

The 2016 Presidential Race: A Cheat Sheet

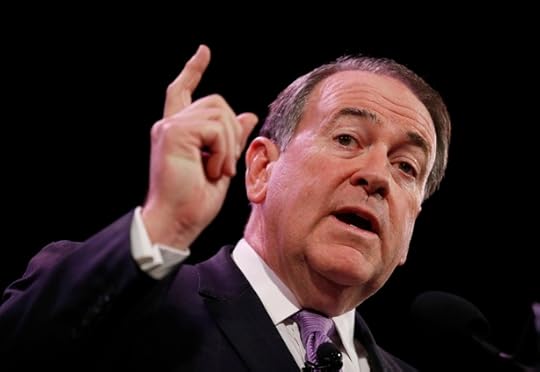

The man from Hope is back. Nope, not that one—the one whose wife is leading the Democratic field. The one who succeeded him as governor of Arkansas: Republican Mike Huckabee.

Huckabee is announcing Tuesday that he's a candidate for president with a kickoff in the hometown he shares with Bill Clinton. After a strong run in 2008 and a decision to take the 2012 cycle off, Huckabee is testing whether he still has the same pull he once did.

He's the third Republican candidate to announce this week alone, and the fourth in 10 days. On Monday, neurosurgeon Ben Carson and tech executive Carly Fiorina both announced campaigns, and last week Senator Bernie Sanders announced he was seeking the Democratic nomination.

With so many candidates in the mix—some announced, some soon to announce, and some still on the fence—it’s tough to keep track of it all. To help out with that, this cheat sheet on the state of the presidential field will be periodically updated throughout the campaign season. Here's how things look right now.

* * *

The Republicans Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Mike Huckabee

Is he running? Yes. He kicks off the campaign May 5.

Who wants him to run? Social conservatives; evangelical Christians.

Can he win the nomination? Huckabee's struggle will be to prove that he's still relevant. Since he last ran in 2008, a new breed of social conservatives has come in, and he'll have to compete with candidates like Ted Cruz. His brand of moral crusading feels a bit out of date in an era of widespread gay marriage—not least when curiously chose to attack Beyoncé. He faces fire from strict anti-tax conservative groups for tax hikes while he was governor. And fundraising has always been his weak suit. But Huckabee's combination of affable demeanor and strong conservatism resonates with voters.

What else do we know? Here is Huckabee's launch teaser video, with plenty of contrast with the Clintons.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Ben Carson

Is he running? Yes, after a May 4 announcement.

Who wants him to run? Grassroots conservatives, who have boosted him up near the top of polls, even as Republican insiders cringe. Carson has an incredibly appealing personal story—a voyage from poverty to pathbreaking neurosurgery—and none of the taint of politics.

Can he win the nomination? Almost certainly not. Carson's politics are conservative on some issues, but so eclectic as to be nearly incoherent overall. He's never run a political campaign, and has a tendency to do things like compare ISIS to the Founding Fathers. It's hard to imagine his candidacy surviving more serious scrutiny, but then again he's reportedly building an impressive political organization, especially in Iowa.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Carly Fiorina

Is she running? Yes, as of a May 4 announcement.

Who wants her to run? It isn’t clear what Fiorina’s constituency is. She’s a former CEO of Hewlett-Packard, but there are other business-friendly candidates in the race, all of whom have more electoral experience.

Can she win the nomination? Almost certainly not. Fiorina’s only previously political experience was a failed Senate campaign against Barbara Boxer in 2010. She has mostly been serving the role of harasser in the race so far, stirring up the news with slams on environmentalists for causing droughts (your guess is as good as mine), Obama for backing net neutrality, and Apple’s Tim Cook for speaking out on Indiana’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Mainly, though, she has strongly criticized Hillary Clinton, and some Republican strategists like the optics of having a woman to criticize Clinton so as to sidestep charges of sexism.

What else do we know? Fiorina's 2010 Senate race produced two of the most entertaining and wacky political ads ever, "Demon Sheep" and the nearly eight-minute epic commonly known as "The Boxer Blimp."

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Marco Rubio

Is he running? Yes—he announced on April 13.

Who wants him to run? Rubio enjoys establishment support, and has sought to position himself as the candidate of an interventionist foreign policy.

Could he win the nomination? Charles Krauthammer pegs him as the Republican frontrunner. His best hope seems to be to emerge as a consensus candidate who can appeal to social conservatives and hawks, and he's even sounded some libertarian notes of late. He's well-liked by Republicans, and has surged forward since announcing, but he needs to move up from second choice to first choice for more of them.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Rand Paul

Is he running? Yes, as of April 7.

Who wants him to run? Ron Paul fans; Tea Partiers; libertarians; civil libertarians; non-interventionist Republicans.

Can he win the nomination? That depends who you ask. The Kentucky senator would be an unorthodox pick, with many positions outside his party's mainstream. He's relatively permissive on drugs and same-sex marriage, passionate about civil liberties, and adamantly for restraint on foreign policy. But Paul has worked hard to firm up establishment ties since reaching the Senate, and he has recently worked to paper over his differences with GOP’s hawkish wing, calling for a declaration of war against ISIS and generally saber-rattling. He is positioning himself as a candidate with crossover appeal in the general election, and his announcement email mocked the idea that only an establishment candidate can win a general election.

What else do we know? One of Paul's greatest strengths is the base bequeathed to him by his father, three-time presidential candidate and former Representative Ron Paul. But as The Washington Post has reported, his father is also Senator Paul's biggest headache, due to his penchant to speaking his mind on issues like secession. Ron Paul's institute also publishes fringe views like the idea that the Charlie Hebdo attacks were a false-flag operation.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Ted Cruz

Is he running? Yes. He launched his campaign March 23 at Liberty University in Virginia.

Who wants him to run? Hardcore conservatives; Tea Partiers who worry that Rand Paul is too dovish on foreign policy; social conservatives.

Can he win the nomination? Though his announcement gave Cruz both a monetary and visibility boost, he still starts with some serious weaknesses. Much of Cruz's appeal to his supporters—his outspoken stances and his willingness to thumb his nose at his own party—also imperil him in a primary or general election, and he's sometimes been is own worst enemy when it comes to strategy. But Cruz is familiar with running and winning as an underdog.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Jeb Bush

Is he running? Almost certainly.

Who wants him to run? Establishment Republicans; George W. Bush; major Wall Street donors.

Can he win the nomination? No one really knows. Since jumping into the race, he has continued to poll well and raise lots of money. He seems like a lock to rack up all-important endorsements from top Republicans. But predictions that he would quickly come to dominate the field have not come to pass, and while many analysts predicted that his moderate record would cause trouble in Iowa and with grassroots activists, that problem seems to be deeper than expected. His poll numbers are probably helped by his name, which is a double-edged sword.

What else do we know? Since Bush's surprise announcement, he has tended to stay fairly quiet, delivering some big speeches and hitting fundraisers, but not making a great number of trips to Iowa or New Hampshire.

David Shankbone

David Shankbone Chris Christie

Is he running? It seems ever harder to imagine. With indictments of two of his former top aides in early May, and a guilty plea by a high-school friend and political appointee, the George Washington Bridge scandal has crept ever closer to him. The New York Times says he's trying to "salvage" his campaign. Christie does have some campaign infrastructure in place in New Hampshire, which is close to his home state, with staffer hires and town-hall meetings there. He has also formed a political-action committee.

Who wants him to run? Moderate and establishment Republicans who don't like Bush or Romney; big businessmen, led by Home Depot founder Ken Langone.

Can he win the nomination? The tide of punditry had turned against Christie even before the "Bridgegate" indictments. It's hard to imagine how he recovers at this point, given the crowded field and the fact that Jeb Bush seems to dominate the moderate end of the Republican Party. Citing his horrific favorability nominations, FiveThirtyEight bluntly puns that "Christie's access lanes to the GOP nomination are closed." A recent Monmouth University poll showed him trailing even Donald Trump (see below) for the nomination. Plus, he'd probably have to resign as governor to run, because of SEC rules that cover donations from companies that do business with the state. With such high stakes, he might not want to run at all if he doesn't see a clear path to win.

When will he announce? According to Time, Christie has told donors that running is harder than he had realized, and that he may have to push back an announcement to as late as June.

What else do we know? If you can tell what is going on in this GIF, please let me know. Is he tossing the jacket away? Or catching it? And what does it mean?

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Scott Walker

Is he running? Almost certainly.

Who wants him to run? Walker's record as governor of Wisconsin excites many Republicans. He's got a solid résumé as a small-government conservative. His social-conservative credentials are also strong, but without the culture-warrior baggage that sometimes brings. And Walker has won three difficult elections in a blue-ish state.

Can he win the nomination? No one knows. For all his strengths, Walker has never run a national campaign and isn't exactly Mr. Personality. But Jeb Bush's emergence seems to have helped Walker, propelling him to the front of the pack as a more conservative alternative to Bush. He's now solidly in the top tier of candidates.

When will he announce? Spring.

What else do we know? Barack Obama took a shot on April 7 at Walker for his criticism of a nuclear-deal framework with Iran. That's a sign that he's becoming a power player, and sniping from the White House is only likely to elevate Walker's standing with Republicans. Good news, bad news: Walker has a geographic advantage in his proximity to Iowa, but a potential biological disadvantage from his allergy to dogs.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Rick Santorum

Is he running? Yes.

Who wants him to run? Social conservatives. The former Pennsylvania senator didn't have an obvious constituency in 2012, yet he still went a long way, and Foster Friess, who bankrolled much of Santorum's campaign then, is ready for another round.

Can he win the nomination? It's tough to imagine. Santorum himself said his chances would hinge on avoiding saying "crazy stuff that doesn't have anything to do with anything." National Review Editor Rich Lowry praised his speech at a January summit in Iowa hosted by Steve King, the representative and conservative powerbroker.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Rick Perry

Is he running? Very likely.

Who wants him to run? Small-government conservatives; Texans; immigration hardliners; foreign-policy hawks. Noah Rothman makes a case here. (Perry's top backer four years ago, non-relative Bob Perry, died in 2013.)

Can he win the nomination? Maybe, but who knows? Perry and his backers insist 2016 Perry will be the straight shooter who oversaw the so-called Texas miracle, not the meandering, spacey Perry of 2012. We'll see.

When will he announce? May or June.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Sarah Palin

Is she running? A bizarre speech in January made a compelling case both ways.

Who wants her to run? Palin still has diehard grassroots fans, but there are fewer than ever.

Can she win the nomination? No.

When will she announce? It doesn't matter.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Mitt Romney

Is he running? Nah. He announced in late January that he would step aside.

Who wanted him to run? Former staffers; prominent Mormons; Hillary Clinton's team. Romney polled well, but it's hard to tell what his base would have been. Republican voters weren't exactly ecstatic about him in 2012, and that was before he ran a listless, unsuccessful campaign. Party leaders and past donors were skeptical at best of a third try.

Could he have won the nomination? He proved the answer was yes, but it didn't seem likely to happen again.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Lindsey Graham

Is he running? Sure, why not?

Who wants him to run? John McCain, naturally. Senator Kelly Ayotte, possibly. Joe Lieberman, maybe?

Can he win the nomination? Not really. The South Carolina senator seems to be running in large part to make sure there’s a credible, hawkish voice in the primary. It seems like Graham started his campaign almost as a lark but has started to get into and enjoy the ride, plus he’s shown he’s a great performer on the stump. He’s still a longshot to actually win the nomination, but he could complicate Jeb Bush’s life by performing well in his home state of South Carolina—though he wasn’t even included in a recent straw poll in the Palmetto State.

When will he announce? By mid-May.

What else do we know? It’s still amazing that the man has never sent an email.

Donald Trump

Is he running?

Others Still in the Mix:

John Kasich, Bobby Jindal, Pete King, Harold Stassen

* * *

The Democrats Wikimedia

Wikimedia Bernie Sanders

Is he running? Yes.

Who wants him to run? Far-left Democrats; socialists; Brooklyn-accent aficionados.

Can he win the nomination? No, although his campaign seems more about getting his ideas into the mix than about winning. In particular, he's an outspoken opponent of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the free-trade agreement President Obama is pushing. Hillary Clinton once seemed to back the deal, but she's offered far more equivocal statements since declaring her candidacy. But Sanders came out of the gate with strong fundraising numbers and has testily rebuffed reporters who suggest he can't win.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Hillary Clinton

Is she running? Yes.

Who wants her to run? Most of the Democratic Party.

Can she win the nomination? Duh.

What else do we know? Maybe a better question, after so many years with Clinton on the national scene, is what we don't know. Here are 10 central questions to ask about the Hillary Clinton campaign.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Joe Biden

Is he running? He won't rule it out, but he's made no serious steps toward a run. He's addressing a "secretive" group of gay donors on May 2.

Who wants him to run? Joe Biden, maybe.

Can he win the nomination? If Clinton didn't run, it would throw the Democratic field into disarray. But probably not.

When will he announce? It seems ever more likely that he won't.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Jim Webb

Is he running? He has launched an exploratory committee.

Who wants him to run? Dovish Democrats; socially conservative, economically populist Democrats; the Anybody-But-Hillary camp.

Can he win the nomination? Probably not.

Steven Senne / AP

Steven Senne / AP Lincoln Chafee

Is he running? Chafee—who served in the U.S. Senate as a Republican and then as Rhode Island governor as an independent and then a Democrat—has launched an exploratory committee.

Who wants him to run? No one knows! Chafee's exploratory committee came out of nowhere, with little anticipation or fanfare or even rumors. He opted not to seek reelection as governor in 2014, in part because his approval rating had reached a dismal 26 percent.

Can he win the nomination? No. Chafee seems to be positioning himself as an economic populist and says Clinton's 2002 vote for the Iraq war should disqualify her (he was the only Republican senator to vote against it). In other words: He's Jim Webb with a less impressive resume, a less compelling bio (he's the son of longtime Senator John Chafee), and less of a political base. He gives himself even odds, though.

When will he announce? He says he wants to gauge support and fundraising and then decide in the next few months.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Martin O'Malley

Is he running? Probably.

Who wants him to run? Not clear. He has some of the leftism of Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren, but without the same grassroots excitment.

Can he win the nomination? Unless Clinton's campaign falls apart, it's hard to see where O'Malley would get an opening. It's hard to judge how these things shake out, but the conventional wisdom since protests over the death of Freddie Gray is that protests in Baltimore undermine the case for his candidacy and make it harder for him to run.

When will he announce? By the end of May.

What else do we know? O'Malley says if he runs, the announcement will be in Baltimore. And have you heard that he plays in a Celtic rock band? You have? Oh.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Elizabeth Warren

Is she running? No. Seriously, no.

Who wants her to run? Progressive Democrats; economic populists, disaffected Obamans, disaffected Bushites.

Can she win the nomination? No, because she's not running.

Battering the Batter

Unless you’re a baseball historian, Ray Chapman probably isn’t a name that sounds familiar. If you do recognize him, it’s because he has the ignominy of being the last Major League Baseball player to die from being hit by a pitch. The Cleveland shortstop died in 1920 at the age of 29, after the Yankees pitcher Carl Mays accidentally struck Chapman in the head with a ball. That MLB has gone nearly an entire century without another on-field fatality has less to do with improvements in player safety and more to do with dumb luck.

Related Story

Every season, numerous pitchers are instructed to throw—with intent to injure—at members of the opposite team. Every season, these intentional hits result in bad blood, threats of future violence, and occasionally serious injury to players whose livelihoods depend on their ability to stay fit. And every season, MLB turns a blind eye to the practice. The recent high-profile dust-up between the Kansas City Royals and Oakland Athletics is only noteworthy because it so perfectly captures the absurdity of team-sanctioned assault. The hit batsman gets a free base, but pitchers pick their spots—waiting until there are two outs and no one on base, or after the outcome of the game is no longer in doubt. Unlike other sports, which assess a meaningful immediate penalty (lost yardage, free throws, forcing a team to play a man short for a period of time), MLB has no such disincentive and so this behavior happens frequently. Meanwhile, baseball fans roll their eyes and shrug—they’ve seen this all before.

But if you’re not a fan, this probably seems absurd: Throwing a baseball at 90 miles per hour or more at another human being qualifies as “assault with a deadly weapon.” It’s only between the foul lines that a violent felony is instead viewed as enforcing the game’s unwritten rules. But that’s the biggest problem in stopping such assaults: Nobody can agree on what the game’s unwritten rules are—presumably because they’re not codified and are thus subject to the whims of the various players and managers interpreting them that day.

It goes something like this: A player on Team A does something to offend Team B (or at the very least, Team B perceives that player did something). Team B orders its pitcher to throw at a batter from Team A. Sometimes that batter is the offending player, but other times, he’s just some poor soul who happens to wear the wrong uniform. Team A, realizing it was intentionally thrown at, then orders its pitcher to retaliate. If the two teams, in their infinite wisdom, decide the retaliation is commensurate with the original offense, play continues. But given that the teams are debating nebulous offenses, it's impossible to guarantee peace after the first attack-and-retaliate cycle. Sometimes these feuds can last for years.

Here are some of the violations of “unwritten rules” that have been the flashpoint for team feuds over the past few years. Being happy after hitting a home run. Being a promising rookie. Running on the pitcher’s mound while returning to a base after a foul ball. Sliding too late. Post-game swimming in a recreational outfield pool after clinching a divisional title.

It’s an absurd list precisely because there's never a good reason to throw a ball at a batter. Yet baseball teams take offense at either real or perceived slights and then kick off a cycle of aggression to which the league turns a blind eye. Umpires are nominally supposed to keep games under control and keep feuds from escalating, but they typically issue warnings rather than eject pitchers who hit another batter. This makes sense—it’s tremendously difficult to measure intent, and sometimes a pitch just slips, resulting in an accidental hit-by-pitch. But by leaving ejections to the discretion of umpires, MLB creates a perverse incentive to strike first: The retaliatory hit-by-pitch is far more likely to warrant an ejection than the event that precedes it.

It’s only between the foul lines that a violent felony is viewed as enforcing the game’s unwritten rules.Even when the league does mete out punishments, the sentence is laughably ineffective. The typical punishment for a pitcher found to have intentionally thrown at a batter is a suspension for fewer than 10 games. Yet starting pitchers only throw once every five days, so with clever scheduling of an appeal, a pitcher can serve his suspension while effectively missing zero games. Thus, there’s no disincentive for a pitcher to throw at a batter—indeed, it’s quite the contrary, as there are many managers and analysts who view assaulting batters as “defending the honor of the game” or “playing the game the right way.”

In fact, you only have to consult MLB’s official rules to see just how seriously MLB takes intentionally throwing at a batter: Rule 8.02(a) governs intentionally modifying the ball to gain an advantage. The mandatory penalty for doing so? Automatic ejection from the game and a 10-game suspension. Rule 8.02(d) governs intentionally throwing at a batter, but there’s no penalty specified. The only comment in this section of note is that throwing at a batter’s head is “condemned by everybody.”

Except it’s not condemned by everybody. Far from it. Take the former Arizona Diamondbacks general manager Kevin Towers, who kept his job for a year—and was celebrated in some corners—after explicitly endorsing hitting more batters with pitches. If you didn’t want to assault a fellow human being? Per Towers, “There’s ways to get you out of here. If you don’t follow suit or you don’t feel comfortable doing it, you probably don’t belong in a Diamondbacks uniform.” Towers was later dismissed as GM, but the fact that the Diamondbacks offered him another position, and that Towers ultimately joined the Cincinnati Reds’ front office, is a good indication that his way of thinking by no means condemns a person in the way the MLB rules suggest.

In other words, the message sent is this: “Throw at batters all you want and we’ll shrug it off, but don’t you dare doctor the baseball. Oh, and if you’re throwing at someone, take care not to hit them in the head. We don’t really know what we’ll do if you do it, but we’ll condemn the practice!”

The sentiment of “don’t hit people in the head” is a nice one, though it’s rather limited. Aside from the nebulous punishment associated with headhunting, pitchers trying to hit a batter don’t have very good aim. Pitchers train to throw at or around the strike zone, so preparing to throw a ball at a batter is an unnatural motion and has a wide variety of outcomes. It’s why you see pitchers throw behind batters when trying to hit them—they’re used to throwing strikes, not hitting people. So it’s not unreasonable to think that a pitcher might intentionally throw at a less-critical body part, miss, and end up hitting the head by mistake. It’s why Jim Bouton wrote in 1970’s Ball Four that he wouldn’t throw at a batter—there was too much risk involved. It’s why the pitcher and author Dirk Hayhurst, 40 years later, expressed the same sentiment. If you throw at a batter, there’s a very high risk of something terrible happening.

Given that executives like Towers think throwing at batters is acceptable—perhaps even laudable—there unfortunately needs to be a reason other than “assault is bad” to stop the practice. Owners, who invest an enormous amount of money in their best players, need to recognize the threat that intentional hit-by-pitches pose to their investments. Take the 2013 National League Most Valuable Player Andrew McCutchen, who was intentionally hit in the back in 2014 and went on the disabled list soon thereafter with ongoing rib issues. Or last year’s MVP runner-up Giancarlo Stanton, who was unintentionally hit in the face by a pitch, breaking his jaw and causing him to miss most of September's games. A player, however talented, is still just a mortal, and when you hit him with a baseball, he’s liable to get injured. Stanton signed a $325 million, 13-year contract this past offseason; it would be foolish not to do everything possible to protect him from further injury.

To that end, MLB should look at its counterparts in other major professional sports. It should also make a sweeping change to its own rules and remove umpire discretion from the game.

The National Football League, for example, is no stranger to scandal. Its treatment of domestic violence and willful ignorance regarding concussions are shameful. Nevertheless, when the NFL was faced with overwhelming evidence that Saints players were offered bounties for injuring opposing players, it acted, doling out suspensions of meaningful length—including some season-long ones. (Granted, like so many disappointing things in the NFL, many of the suspensions were later reduced or lifted, but at least the initial reaction was appropriate.)

MLB wouldn’t even need to mount an in-depth investigation: Pitchers admit to throwing at batters frequently. The Phillies pitching ace Cole Hamels, when he hit Washington’s Bryce Harper for the high crime of being a lauded rookie, explicitly said, “I was trying to hit him.” Hamels received a five-game suspension and missed zero starts. If MLB handed down longer suspensions for intentionally hitting batters, it would go a long way toward curtailing the practice. When teams start feeling an on-field effect from throwing at batters—playing with a 24-man roster or not having their best pitchers available for several starts—they’ll find other ways of enforcing the “unwritten rules.”

Ask Giancarlo Stanton’s jaw if it mattered that Mike Fiers wasn’t aiming at his head.MLB can also look at the National Hockey League, which has a rule that’s always enforced regardless of intent. The NHL gives a player a two-minute delay of game penalty if he shoots the puck over the glass out of his own end. It’s irrelevant if the delay of game occurred because the player was trying to stave off an offensive rush, or if he just ran into some bad luck.

MLB can follow the same process, though it would be far more controversial: automatic ejections of any pitcher who hits a batter above the waist. Doing so removes umpires’ inability to measure intent from the equation. Hit a batter above the waist, hit the showers early, no exceptions. Ask Giancarlo Stanton’s jaw if it mattered that Mike Fiers wasn’t aiming at his head—the injury is the same. An ejection isn't the same as a suspension—the team would only be without its pitcher for the duration of the game in which the hit-by-pitch occurred. A subsequent suspension would still be under the purview of the league office; it would still determine intent when assessing whether a longer punishment was necessary.

To be sure, this would have a profound impact on the game. Many pitchers rely on pitching inside—sometimes high and inside—to remain effective. Were automatic ejections the rule, offense would increase, as batters would no longer need to fear the inside pitch. Yet that might prove a blessing in disguise, as the new MLB commissioner Rob Manfred has stated that he’s looking for ways to increase offense in the sport. Severely penalizing dangerous pitching will improve offense while at the same time mitigating the risk of a gruesome or fatal injury. The sport has survived profound changes to offense over the last two decades; a player’s career may not survive a fastball profoundly changing the structure of his skull.

Even adamant defenders of the sport’s tradition can acknowledge that a baseball moving at high velocity is dangerous. The former outfielder Juan Encarnacion’s career ended when he was hit in the eye by a foul ball. The former player Mike Coolbaugh, while coaching, died after being hit by a batted ball. This is the reason why, when you go to a game, you’re instructed to keep an eye on play—bats and balls leaving the field are dangerous. For MLB not to crack down on pitchers intentionally throwing at batters is a profound oversight on its part at best, and a tacit endorsement of assault at worst. One can only hope the sport takes action before Ray Chapman's unfortunate status as the answer to a trivia question goes to another unlucky player.

May 4, 2015

How NBA Teams Campaign for Their MVP Candidates

On Monday, the National Basketball Association announced that Golden State Warriors guard Stephen Curry had been named the league's most valuable player. Despite the impressive victory—Curry garnered 100 of the 129 first-place votes from members of the press—this was one of the more competitive MVP races in recent history.

Ahead of the voting, Curry seemed an odds-on favorite, despite some support among pundits and players for second-place finisher James Harden of Houston as well as four-time MVP LeBron James of Cleveland and Russell Westbrook of Oklahoma City. With commentators largely vacillating between Curry and Harden throughout the year, team public relations offices launched campaigns to make their cases to voting members of the press.

In such an intriguing year, the criteria for determining what makes a player "valuable" was more subjective than ever. Week after week, analysts debated the merits of the leading players. The various splits in the MVP narrative not only made for a heightened publicity campaign, but also shaped the way teams lobbied for their respective candidates. Here's a glimpse at how the campaigns broke down.

Winner: Stephen Curry, Golden State Warriors

Stephen Curry led the Warriors to an otherworldly kind of season. The team netted a league-high and franchise-record 67 wins, seven better than the closest team. Along the way, Curry broke the all-time NBA record for three-pointers made, ruined lives with late-game heroics, and dazzled crowds with his electric offensive play.

Despite all this, Curry didn't appear to be a lock for the award for a few reasons. He played on a team that stayed healthy for most of the year and had a number of other players very ably back him up. In other words, he was the best player on the best team.

The Warriors campaign for Curry has been described as a low-key and old school affair. The Warriors media team simply called each of the voting members and emphasized that Curry had led his team to 67 wins, only the 10th team in league history to win that many games. According a voting member from the Orange County Register, the Warriors campaign helped to persuade him to change his vote from Harden to Curry.

2nd Place: James Harden, Houston Rockets

Unlike Curry, James Harden was the best player on a heavily injured and inconsistent Houston team. As the league's second-leading scorer (behind Oklahoma City's Russell Westbrook), Harden shouldered more of the Rockets' offensive load than he probably should have, at times willing his team to finish second in the Western Conference behind the Warriors.

With Rockets star center Dwight Howard out for half of the season, Harden led the NBA in free throws, minutes, and points as well as win shares, an advanced statistic that measures how many victories a certain player's contributions add to a team's total. Accordingly, the Rockets put together a publicity bid for Harden's season that emphasized his all-around performance on a team that badly needed his help.

"The Rockets were more cutting edge, producing a hard-bound book that, when opened, delivers to voters a slick video campaign message," wrote Jeff Faraudo of the San Jose Mercury News. "The inside cover has a sleeve that holds three large cards with more statistical reminders of the season Harden has assembled."

With total votes counted, Harden was the closest runner-up in MVP voting in four years.

The Field

While third and fourth place finishers LeBron James and Russell Westbrook didn't have a dedicated campaign blitz behind them, the two remained in the conversation for very different reasons. In James' return to Cleveland, his team's play was preternaturally lousy when James was injured or off the court. (They finished second in the Eastern Conference.) Meanwhile, Westbrook captivated fans by leading the league in scoring with teammate and former MVP Kevin Durant out for most of the season.

Then, of course, there's New Orleans forward Anthony Davis, who finished in fifth place. In just his third season, the star forward made his team suddenly relevant again as the Pelicans made the playoffs for the first time since the team changed their name from the Hornets. In a sly push, the team sent out dolls with Davis' unique likeness to MVP voters.

Just got my Anthony Davis unibrow MVP doll in mail from Pelicans. I know my No. 1. My 2-3 tough. Thoughts? pic.twitter.com/eCbNOjBvnL

— Marc Berman (@NYPost_Berman) April 10, 2015

Davis became the youngest player to finish in the top five of the MVP race in six years.

While Curry may have scored a very prestigious piece of hardware on Monday, the award hasn't always translated into the ne plus ultra of hoop dreams, an NBA championship. Since the NBA started handing out MVP awards in 1956, only 22 of the winners played on teams that went on to win a title. Nevertheless, many are betting heavily on Curry to win both.

Nepal's Recovery Stalls

Nine days after a major earthquake struck Nepal, the country remains mired in a humanitarian crisis. The death toll from the disaster stands at more than 7,200, while many thousands more are injured. The earthquake destroyed at least 70,000 buildings throughout the country, and officials estimate that more than 75 percent of those left standing in Kathmandu are uninhabitable or unsafe. More than 2.8 million Nepalis—roughly 10 percent of the population—have been displaced, and several million are in dire need of food, water, and sanitation services.

International assistance is essential in addressing the immense challenges posed by the April 25 quake. But on Sunday, government officials barred airplanes carrying aid from landing at Kathmandu's Tribhuwan International Airport on account of damage sustained by the airport's lone runway. Tribhuwan is Nepal's only international airport and, in a landlocked country with poor road and rail infrastructure, its most important transportation hub. Nepal's mountainous topography and poor infrastructure have made it difficult for rescuers to reach many of the hardest-hit villages. But the country's unstable and ineffective government—not its geography—remains its biggest liability.

The country's unstable and ineffective government is its biggest liability.According to a UN official, Nepali customs regulators have been slow to process incoming aid, and many materials have piled up at Kathmandu Airport. Krishna Gyawali, a senior bureaucrat in Sindhulpalchowk district, estimated to The Guardian that aid operations have only met 20 percent of need. Nevertheless, on Monday the Nepali government asked remaining international rescue workers to depart the country, having determined that they were no longer needed.

Nine years after a decade-long civil war, Nepali politics are characterized by gridlock and instability—problems that have been on display in the aftermath of the disaster. Aware that the area around Kathmandu is susceptible to earthquakes, the Nepali government established building codes mandating that new structures be earthquake-proof. But enforcement was often lacking.

“There is complete lack of accountability," Krishna Kanal, a Nepali political analyst, told the Hindustan Times. "This disaster was compounded by the absence of political leadership and will as well as ineffective urban planning and disaster management.”

As Nepal faces its largest reconstruction process in generations, the country's fractured and ineffective government may be as much a problem as a solution.

The Corruption of Bipartisanship

People say they want more bipartisanship. In poll after poll after poll, they decry the polarized atmosphere in Washington and say they want their leaders to work together.

To which the people of New York and New Jersey might reply: seriously?

It's indictment-and-arrest season in the tri-state region. Monday morning, New York State Senate Leader Dean Skelos, a Republican, and his son Adam were arrested on federal charges of extortion, fraud, and soliciting bribes. It's been just three months since State Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, a Democrat, was himself arrested on federal corruption charges. Meanwhile, across the Hudson River in New Jersey, Bridget Anne Kelly and Bill Baroni, two former top allies of Governor Chris Christie, pleaded not guilty to nine counts apiece including wire fraud and conspiracy in the George Washington Bridge Scandal. On Friday, David Wildstein, a Christie appointee, pleaded guilty to two conspiracy charges in the same scandal.

What New York and New Jersey share, besides oft-imitated accents and embarrassing reputations for political corruption, is bipartisan governance. It wasn't that long ago—before the bridge scandal, credit downgrades, and collapse of Atlantic City—that Christie seemed like a model of a Republican who could work with Democrats and achieve his priorities. Christie forged an alliance with Jersey Democratic boss George Norcross and his protege Steve Sweeney, the Democratic president of the State Senate. Christie even managed to gain many Democratic endorsements in his 2013 run for reelection. In fact, prosecutors say it was his aides' overzealous attempt to squeeze an endorsement from the Democratic mayor of Fort Lee that led to the bridge closure that now threatens to undo his career.

Related Story

'A Deliberate and Illegal Scheme' in New Jersey

Something similar was going on in Albany. Governor Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, became extremely close with Silver and Skelos, even though Skelos was a Republican. In his January State of the State address—the day before Silver's arrest, it turned out—he described his relationship with the two as "the three amigos." The alliance drove some other New York Democrats nuts. Even though Cuomo had delivered two major progressive priorities in passing gun control and legalizing gay marriage, he governed far too close to the center for liberals' taste on economic issues. But that allowed Cuomo to run the state government smoothly and implement his agenda.

In both cases, government functioned thanks to the lubrication of lucre, which allowed coalitions to grow across the aisle. There's been no clear evidence of illegality outside of the bridge scandal, but reporters including Alec MacGillis have shown how Christie doled out favors to his and Norcross's factions while bullying opponents into support or at least silence. In Cuomo's case, he launched a highly trumpeted ethics inquiry, the Moreland Commission, after a series of embarrassing arrests of lawmakers, but then muzzled and eventually shut it down—when, it seems, it annoyed too many members of both parties. Unfortunately for them, and for Cuomo, U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara decided to pick up where the commission left off and ended up with charges against the two leaders.

One common risk factor for scandal is single-party domination. If one political party controls a state long enough, the opposition party fails to be an effective counterweight and the ruling party may lapse into scandal through sloppiness or lack of competition. I wrote about this pattern a few years ago, discussing the travails of South Carolina, where Democratic Party politicians are perpetual losers. (In that article, I also suggested the Empire State might be getting its own act together, after years of Democratic-dominated corruption, under Cuomo. Oops!)

But bipartisanship holds its own risks, as New York and New Jersey show. Last year in The Atlantic, Jonathan Rauch argued that what the nation really needs is a bit more corruption. He pointed to the dysfunction caused by the abolition of earmarks in Congress, a step intended to stop corruption but also stopped dealmaking in D.C. More broadly, he said, old-school Tammany Hall politics aren't such a bad thing:

Earnest campaigns to take the politics out of politics can make governing more difficult, with results that serve no one very well. The next time you see some new reform scheme touted in the name of stopping corruption, pause to recall the wisdom of another old-school pol, the late Representative Jimmy Burke, of Massachusetts: “The trouble with some people is that they think this place is on the level.”

This isn't to say that there isn't a line between legal and illegal deal-making (or, as the Tammany mandarin George Washington Plunkitt phrased it, between honest and dishonest graft). If the charges against Baroni, Kelly, Skelos, and Silver are proven, it will show that they went past the sort of backroom pressure that makes politics run. But both inquiries are inseparable from bipartisanship—in New York, from Cuomo's apparent move to protect allies by shutting down the Moreland Commission, and in New Jersey, from the fervid quest to get Democratic support for the Republican governor.

Bipartisanship isn't a bad thing—but voters shouldn't imagine that politicians working across party lines will make everything work beautifully. As New Jerseyans and New Yorkers can attest, comity has its downsides too.

The Death of an Underdog in American Art

One by one, the Master’s figures will take their leave. Saint John the Evangelist. Abraham and Isaac; two little “profetini,” or child prophets; a gaunt figure known as the Zuccone, whose quizzically fierce expression has caused almost as much art-historian speculation as the Mona Lisa’s smile. Eventually, nine marbles created by or ascribed to Donatello, the greatest sculptor of the early Renaissance, will all be carefully packed into super-re-enforced wooden crates, sealed, and will leave the place that's served as their home for the past four months: a tiny (2,500 square-foot) museum almost nobody had heard of.

Related Story

How Sufjan Stevens Subverts the Stigma of Christian Music

That's until last February, at least, when The New York Times visited and announced, “Hard to believe, but true: an exhibition that includes three major works by … Donatello has come to New York, and it’s not at the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Frick Collection. It’s at the Museum of Biblical Art.” The review lauded the “beautiful, soul-stirring exhibit.” The New Yorker’s critic called it “splendid.” But in June the iconic figures will return to their home in the newly renovated Florence Cathedral Museum, and carpenters will tear down their temporary wooden pedestals.

And the little New York museum that could? A few months later, carpenters will tear it down too.

Art museums go out of business all the time: The truism is that few last more than three years. But fewer still disappear on the heels of a triumph like Sculpture in the Age of Donatello: Renaissance Masterpieces From the Florence Cathedral. It’s not only that the Museum of Biblical Art's exhibit is probably once-in-a-lifetime in this country—Florence’s Cathedral Museum (Museo dell’Opera del Duomo) won't be renovating again any time soon—so much as it's the fact that even the Duomo has never arranged these pieces with this kind of charged intimacy. The show, just as the critics said, is a wonderful, startling event, instilling in busy, secular New Yorkers the awe that 15th century Florentines must have felt under the scrutiny of dozens of marble saints when the sculptures were new; and one imbued with MOBIA’s deep understanding of early Renaissance spirituality.

And yet last Tuesday the museum’s board announced “with great sadness,” that it would be closing to the public on the last day of the Donatello show (June 14), and closing “altogether” on June 30. The American Bible Society, which had essentially been donating MOBIA space in its own building just north of Columbus circle, announced in February that it was selling the space to a developer and moving to Philadelphia. In “such a short time frame,” the board wrote, it was impossible to raise funds to rent and renovate a new site.

Said Marcus Burk, senior curator at the Hispanic Society of America and a past MOBIA collaborator, “This is just a torpedo at the water-line. It’s an enormous loss to the cultural life of New York and the whole country.”

***

Immediately following the news of MOBIA’s closing, it was clear that professional commentators knew that they had lost something, but they didn’t seem to know exactly what. In Slate, Ruth Graham mourned an institution that (as quoted from MOBIA’S “Mission and History” page) “celebrates and interprets art inspired by the Bible.” Graham legitimately took both secular and religious donors to task for not stepping up, but reported cheerily that all was not lost. “Luckily,” she announced, “the Metropolitan Museum’s remarkable collection of Christian art is just a 30-minute stroll across [Central] Park.”

That reaction, and others, suggested that the issue here was the simple loss of a venue for the art of religion. But MOBIA served a far more particular purpose that made it nationally unique. (A couple of museums in far smaller markets come close.) It corrected for a massive flaw in museum culture by being a gallery dedicated to the religious nature of religious art. And not only that, but it was a secular museum dedicated to the religious nature of religious art.

If “religious nature of religious art” seems tautological, blame Western curatorial history for making it not so. Although most important American institutions abound with the art of faith, until recently, those museums provided almost no information about that art’s spiritual inspiration, its ritual use, or where it fit into the roiling histories of popular belief or religious politics. Or as Ena Heller—MOBIA’s founding director and now director of the Cornell Fine Arts Museum at Rollins College in Orlando, Florida—remarked in 2004, most museums displayed “an undeniable reluctance to interpret the religious component of art.”

Louis C. Tiffany and the Art of Devotion, Courtesy of the Museum of Biblical Art

Louis C. Tiffany and the Art of Devotion, Courtesy of the Museum of Biblical Art That flaw is breathtaking: Imagine a museum showing Warhols being “reluctant” to talk about late-20th-century consumerism, or an institution exploring German Expressionism being leery of bringing up World Wars. For a decade, MOBIA, which Heller founded in a shoebox in 2005, has acted as a kind of two-cylinder antidote, presenting Christian and Jewish religious art with all the context museums traditionally ignored. And it's done so while maintaining a strictly secular curatorial philosophy, confuting those who think that to concentrate on religion means to evangelize. The victorious Donatello show seemed to assure that MOBIA could continue to explain the cultural influence of the Bible on art—obvious yet ignored—from a perch of true national stature.

Now, it's up to art consumers to internalize the museum’s insight for themselves.

***

The absence of religious context for religious art in American museums was not, as one might assume, a product of the culture wars or a precocious expression of the new atheism. It was actually the result of several hundred years of aesthetic politics. The first “modern” art museum, the Louvre, was the re-purposing of Louis XVI’s collection by the Revolution, which stripped out its religious aspect.

The Yale art-history professor Robert Nelson provides the English-language variant in his 2004 essay, “Art and Museums: Ships Passing in the Night?” Nelson recounts the immensely influential critic John Ruskin’s popularization of Venetian (Catholic) church architecture, but explains that “English Protestant prejudices, which [Ruskin] shared,” made it necessary to “aestheticize and thus secularize the churches.” Ruskin advised art pilgrims to avoid days when the churches were filled with “woeful groups” of believers, “fixed in paralytic supplication.” You could call it a triumph of the eye over the soul.

Nelson describes museums as becoming little factories for secularizing their own collections. The habit also caught on in the U.S., where curators were often Protestant—or later, Jewish refugees—with limited appetite for Catholic ritual or devotion. Other trends —an enthusiasm for abstraction, Vietnam-era anti-establishmentarianism, and postmodernism—made faith a non-topic, except when treated ironically. Eventually, said Gary Vikan, the former director of the Walters Museum of Art in Baltimore, what may have started in Europe as a Protestant aversion became “more a matter of intellectual snobbism and glib cynicism." Religion "was something you didn’t discuss in polite company,” and museums were the epitome of polite company.

By the 1990s, labels for religious paintings in permanent collections rarely included mention of the biblical verses the paintings were based on. As MOBIA’s current (and final) director, Richard Townsend, notes, “If a piece of art were based on a scene in Ulysses, it would be on the label.” The very function of Orthodox icons, created as mystical windows through which to access saints, went unmentioned, as did art’s role as a pictorial Gospel during Europe’s centuries of illiteracy. Excepting trailblazers like Vikan and Helen Evans at the Met, few curators offered shows organized around religion—or even admitted it as a category of interest: The subject subheadings in the 2001 Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibitions Services (SITES) catalog included gender studies, maritime history, and sports, but omitted naming religion even when faith-based art loomed large in a show.

***

MOBIA wasn't initially conceived to redress centuries of imbalance. It started out as the brainchild of the American Bible Society, a nearly 200-year-old Bible translation and distribution ministry. The ABS website announces, “We long for a world where no-one is separated from a loving and restorative relationship with Jesus Christ,” and its hope in 1997 for what became MOBIA was to further that mission with a gallery at its spectacular Midtown headquarters.

To run it, the ABS approached Heller, then a 33-year-old art historian . She accepted, but not out of evangelistic verve. “I was thinking, let’s look at these works of art not just as we’re used to looking at them in museums, but as objects that had been employed for a very specific purpose," she said. "Let’s understand how they were conceived, the way they were used and the way they were looked at.” She demanded that the gallery be secular, presenting the faith-based art in a religiously neutral light. She argued that this would expose the art to more people, and the ABS accepted her terms.