Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 438

April 30, 2015

The Play That Took Me Inside My Autistic Son's Head

For 16 years we’ve been locked outside my firstborn son’s head. Sam is a boy, fast becoming a man, whose sense of the world around him is defined by his own fixed point on the autism spectrum. He can rarely conceive what’s expected of him in social situations, and by that I mean a setting as routine as a family dinner with his parents and his two brothers—let alone an environment as demanding as high school, or the adult world.

Related Story

Making Theater Autism-Friendly

But for two hours recently, we got a glimpse at some of the chaos that might be raging in there, thanks to The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time—the innovative, high-tech theatrical adaptation of Mark Haddon’s 2003 best-selling novel of the same name. The play, which was recently nominated for six Tony Awards, came to New York from London’s National Theatre in a production directed by Marianne Elliott (War Horse). It takes an immersive approach to communicating the internal state of its hero, Christopher. Like Sam, Christopher is an autistic teenage boy who’s often perplexed by the day-to-day demands of human interaction.

“People often say, ‘Be quiet,’ but they don’t tell you how long to be quiet for,” says Christopher at one point, attempting to explain the confusion he feels almost constantly. The show isn’t without humor in the way it portrays the poignancy of the missed emotional connections between Christopher and his family and the people he meets, and the line drew a healthy laugh from the audience. But for me and Sam’s mom, it lingered.

Unlike Christopher, who is rather on the voluble side for a kid on the spectrum—Haddon has stated that his book is more about cognitive differences than “any specific disorder”—Sam has been diagnosed not just with Asperger’s but also “selective mutism,” an extension of his social anxiety. If he’s uncomfortable, he gets stuck, and he won’t, or can’t, talk. When he was overwhelmed at a new school full of high-functioning extroverts two years ago, his shutdown lasted all summer.

Haddon’s book surely wouldn’t have worked with an uncommunicative main character, and it goes without saying that a theatrical adaptation would have been out of the question. Even so, for years the author considered his beloved book to be “unadaptable.” But the ingenious storytelling methods devised by Elliott, playwright Simon Stephens, and their choreographers and set designers are the primary reason the show succeeds. Christopher’s anxious chatter isn’t the only window into his mind—the design elements illuminate his turmoil, too.

The production team set the show inside a big black box. (It’s the same team that premiered the play in London, with a different cast.) The three walls facing the audience are lit to look like graph paper; letters and symbols and mathematic equations cascade across them, sometimes defying gravity, streaming up from the floor to the ceiling. When Christopher is distressed, electronic music pounds and seizure-inducing hot white lights flash.

When Christopher is distressed, electronic music pounds and seizure-inducing hot white lights flash.Long before he was diagnosed, we knew something was different about Sam. On a trip to Los Angeles just after the birth of our second son—Sam was a year and nine months old—we were stunned as we sat in a parking lot and he blurted out the letters on the sign in front of us: “S-T-A-R-B-U-C-K-S.” We had no idea he’d already learned the alphabet. Soon, to soothe himself to sleep, he was reciting the alphabet forward and backward.

As he grew older, Sam’s stony facial expression, so characteristic to the condition, would only rarely betray any kind of emotion. But we’ve come to understand that’s a hard mask for his inner turbulence. Seeing it imagined onstage was a revelation. The play’s bad-trip-at-a-rave depiction of Christopher’s rampaging synapses represents a stark contrast with the theater industry’s recent efforts to make shows such as The Lion King more accessible to kids on the autism spectrum, with softer volume and dimmer lighting.

In another of the play’s inventive moments, when Christopher (played by Alex Sharp, a Broadway newcomer and recent Juilliard graduate) is having an out-of-body experience, his supporting cast members take their roles literally. They hold him up parallel to the ground so he can sprint around the walls, like another science-minded high schooler, Peter Parker, after his spider bite.

Curious Incident's creative use of visual elements is just one way the show communicates how many people on the autism spectrum experience seeing the world. In the book Life, Animated, Ron Suskind writes about his son’s Asperger’s and how the two were able to connect through Disney movies. Sam, too, has an affinity for animation: He creates amusing short films using a graphics tablet and a software suite, and has a remarkable facility for perspective. Temple Grandin, the animal behaviorist and autism activist, has written extensively about her own visual thinking, stating, “My mind is similar to an Internet search engine that searches for photographs.” And Christopher might agree. “I see everything,” he says in the play.

Most people gazing out the window on a train, he states, will acknowledge the general view: the grass, the cows, the fence. Then their mind will begin to wander. But if Christopher is on that train, he’ll calculate the whole scene: 19 cows—15 of them black and white, four brown and white. Thirty-one houses visible in the village in the distance, plus one church without a spire. The landscape is highest to the northeast. It’s exhausting just hearing him describe it, but it gives some sense of what it must be like to be so attuned to minute details.

"I see everything," Christopher says.The “curious incident” mentioned in the show’s title is Christopher’s discovery of a dead dog in a neighbor’s yard. He wants to find out who killed the dog and left it there, but he’s quickly marked as a suspect himself. The event prompts Christopher to uncover some upsetting family secrets related to his parents’ reactions to their own shortcomings, and their despair that they can’t properly care for their son.

The moments in the show that focused on the parents’ frustrations were all too familiar for us. Ed, Christopher’s well-meaning, working-class dad (played with lumbering sensitivity by Ian Barford), whips painfully between tenderness toward his child and fist-clenching fury over his inability to help him navigate the world. Ed and his estranged wife, Judy (Enid Graham), have become trapped by their own sense of discouragement, and find it hard to imagine a more hopeful future for themselves and for Christopher.

We’ve been there—we’re forever backtracking there, it seems—with Sam. But we left the show buoyed, at least for the night. The show ends on an up note (spoiler alert): Christopher celebrates, in his own curious way, his successes. Against the odds, he’s aced a major exam, survived a harrowing trip to London, reconciled with his mum and solved the mystery of the death of Wellington, the dog.

“Does that mean I can do anything?” he asks.

For the parents of a child on the spectrum, the true answer might not be the one we want. But it’s our continuing job to help Sam understand his own mind. As much as we’ve struggled, seeing such an inspired interpretation of my son’s baffling affliction gave us the gift of a necessary reminder: Sam, like Christopher, is the one trying to find his bearings at the center of his own curious world.

April 29, 2015

The Qu'osby Show

The first scene of Halal in the Family, a new Funny or Die web series, opens with a family sitting in a suburban living room with lemon-colored walls and a drab couch as the focal point. The set isn't the only element transporting viewers back into an episode of All in the Family or The Cosby Show: There's a laugh track, a multi-camera setup, over-the-top acting, and an ugly-sweater-clad father. There's one key difference though: This sitcom family is Muslim. The Daily Show correspondent Aasif Mandvi’s new comedy is a parody of TV classics, but it’s also a uniquely modern show that centers on a batty family called the Qu'osbys, who navigate the kinds of discrimination and stereotypes faced by many of the two million Muslim Americans living in the U.S. today.

Related Story

What I Learned Trying to Write a Muslim-American Cop Show for HBO

The show’s four episodes—all currently online—tend toward the preposterous and exaggerated, with storylines involving FBI moles, sharia law in high school, and a haunted terrorist training camp. “We have created something that is not only funny but also has a strong message against intolerance and fear mongering, and racism,” Mandvi told MTV in a recent interview. The show uses goofy humor to confront unnervingly real issues like FBI surveillance and nationwide mosque protests head-on, and it largely succeeds at being clever and provocative while generating laughs. Halal in the Family doesn’t claim to be a definitive fix, remedying all misperceptions about Islam and Muslims in the media. But in its effort to address years of misunderstanding, the show risks further cementing the very stereotypes it's ostensibly trying to deconstruct. In going to great lengths to prove they’re just like every other American, Mandvi's characters obscure their Muslim identity in the process and dilute the otherwise positive efforts of the project.

Mandvi stars as Aasif Qu’osby, the ignoramus father whose jovial candor makes him every bit as lovable as he is embarrassing. In the first episode, “Spies Like Us," Aasif suspects his son’s white math teacher, Wally, is an FBI informant when he says he volunteers at a mosque. Fatima invites Wally to join them for dinner saying, “We’re having Aasif’s favorite: deep fried pork chops with bacon sauce!” The cheeky humor and satirical packaging of the premise is clear, but proclamations like these push Halal in the Family into murky territory, reinforcing the most troubling stereotype of all—that the more “religious” a Muslim is, the more dangerous he or she is. In another episode, Aasif says, “Why would I want to build a mosque? I’m not trying to start any trouble.” Jokes like these might be lost on many, in an era when religious practice is an indicator of extremism in the eyes of law enforcement, and activists like Ayaan Hirsi Ali are propagating the idea that many tenets of Islam are reprehensible and should be separated from modern understandings of the faith.

Still, the web series is meaningful in an industry that tends not to feature many Muslim stories in the first place. Halal in The Family is the product of a concentrated and drawn-out effort by Mandvi and his supporters. The series originated as a sketch by another name on The Daily Show four years ago, and emerged from a collaboration between Mandvi and his Daily Show writing partner Miles Kahn. Mandvi opted to put it up online instead of pitching it to TV networks, giving his team full creative control and allowing broader access to his message. The series enjoys financial support and guidance from a list of high-profile advocacy groups and non-profit organizations including the Brennan Center for Justice, Muslim Advocates, and MTV’s Look Different campaign. Mandvi also launched a crowdfunding campaign on Indiegogo to raise additional funds and received an enormously positive response. The strong backing and public support is a testament to the significance of Mandvi’s endeavor—having a Muslim family at the center of its own series adds representation that is noticeably missing from the pop-culture landscape.

But Halal in the Family assumes too much if it expects its viewers to largely be in on the joke, or at least to be able to separate fact from fiction. Islamophobic sentiment and misinformation about Muslims is prevalent in the U.S., a trend Mandvi himself discussed in a recent interview with Al Jazeera America. An anti-Islam group recently won a ruling in a federal court to run offensive ads across subway cars and buses in New York. One such ad features a black-and-white image of a man in a checkered scarf and reads, “Killing Jews is Worship that draws us close to Allah, That’s His Jihad. What’s Yours?” A Muslim advocacy group filed a complaint last week on behalf of two hijabi women who were asked to move out of camera view during the taping of the daytime talk show The Real. This sort of messaging has chilling repercussions. A recent Pew Research Center poll found that the majority of Republicans and nearly half of Democrats surveyed felt that Islam was more likely than other religions to encourage violence. Hate crimes against Muslims are five times as common today as they were before 9/11.

Halal in the Family assumes too much if it expects its viewers to largely be in on the joke, or at least be able to separate fact from fiction.Speaking to the implications of Islamophobia, Mandvi referenced the recent Chapel Hill shooting, where three young Muslim students were murdered in their home in what many believe was a hate crime. Examples like these are precisely the reason some might feel that Mandvi misses the mark, despite his good intentions. During the catchy and clever intro for the show, Aasif yells “We’re not that kind of Muslim!” as he’s being hauled away by FBI agents. Which prompts the question: What kind of Muslim is he referring to and, however jokingly, distancing himself from? The businessman who refuses a drink at an office party? The bearded student who prays in public on campus? The young headscarf-clad women who are active leaders in their local mosque?

By these standards, the three students who were brutally killed at Chapel Hill were “those” kinds of Muslim. They were active in the Muslim Student Association on campus, wore the hijab, and exhibited all the outward characteristics of Islam one could think of. These are the American Muslims who bear the brunt of Islamophobia and who are perhaps being alienated by efforts like Halal in the Family. Mandvi is spot-on in attempting to unravel the idiocy in the idea that simply assimilating with “American” culture makes you “normal." But where Halal in the Family stumbles is implying that one has to be a certain kind of Muslim to be "normal," too.

Mandvi’s audience may not be aware enough of the complexities of faith and practice, or even the current Islamophobic landscape, to fully grasp the extent of his satire. And if they’re of the Netflix generation, their pop-culture repertoire likely doesn’t extend far back enough to understand how All in the Family informs this series. Archie Bunker—a bigoted, blustering dolt—challenged audiences to see the ignorance in his racist, sexist purview. While Aasif Qu’osby is ignorant like Bunker, he's not sneering at the world around him. He’s looking in a mirror. A protagonist who directs ire toward himself rather than at the flawed universe he lives in could be seen as sending a puzzling message to the people who are like him.

Mandvi said in his Al Jazeera interview that “there are many American Muslims out there who feel like there’s an underrepresentation of this voice out there in the American media.” To this end, Halal in the Family is a cultural milestone. He and his team deserve kudos for managing to be funny while fearlessly tackling problems like the broad surveillance of Muslim student groups, mosques, and leaders by law enforcement agencies after 9/11. (Halalinthefamily.tv uses the four episodes to provide a wealth of information and statistics on the specific issue each episode tackles.) But it's also worth noting that Muslims might also become more sympathetic characters in entertainment without their Muslim-ness, with all its political and cultural undertones, preceding them. Maybe one day a sitcom in the vein of Friends will feature a woman who wears the hijab, and it won’t be indelicately discussed as a teaching tool.

Now that would be normal.

Shinzo Abe Bets on America's Fading Memories

Throughout his speech to a joint session of Congress Wednesday, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe cited continuities in the relationship between his country and the U.S. "Our alliance has lasted more than a quarter of the entire history of the United States," he noted. He mentioned his grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi, a former Japanese prime minister who helped forge the close U.S.-Japanese alliance that developed after World War II.

But in many ways, Abe's speech, and themes he propounded, tested the limits of generational turnover. How far have memories of the war receded? Has enough time passed that Japanese and Americans alike are comfortable with Abe's vision of reversing military limits in the post-war constitution the U.S. wrote for Japan? And will members of Congress forget the sometimes-tense U.S-Japan trade relationship of the 1980s and agree to a sweeping new free-trade agreement?

Abe—the first Japanese head of government to address a joint session of Congress—was born in 1954, nearly a decade after the war ended. His praise Wednesday for the late Senator Daniel Inouye as a beacon of Japanese-American achievement served as a reminder that there are no World War II veterans left in Congress. The prime minster opened with a lengthy reflection on the war, recounting a visit he paid to the World War II Memorial on the National Mall before his speech:

Pear Harbor. Bataan. Corregidor. Coral Sea. The battles engraves at the memorial crossed my mind and I reflected upon the lost dreams and lost futures of those young Americans. History is harsh. What is done cannot be undone. With deep repentance in my heart, I stood there in silent prayers for some time. My dear friends, on behalf of Japan and the Japanese people, I offer with profound respect, my eternal condolences to the souls of all American people that were lost during World War II.

While Abe's sentiments seemed heartfelt and extensive, he didn't make a great effort to delve into Japan's role in starting the war, nor its conduct during the fighting. He has come under heavy international criticism for visiting the Yasukuni Shrine, which memorializes fallen Japanese soldiers, including convicted war criminals. Abe also didn't mention "comfort women," the women forced into sexual slavery during the war. That the Japanese used them is not in historical dispute, but some members of the nationalistic wing of Japanese politics to which Abe belongs have denied it. This makes the issue a sensitive one for the prime minister, who finds himself caught between foreign demands and his political base. American politicians, including Senator Marco Rubio, have called on him to apologize, which he declined to do Tuesday.

Abe's nationalistic politics has also involved the promotion of a stronger national-defense policy. The post-war constitution sets out limits on the scope of Japan's military, but he has sought to loosen them, and on Wednesday vowed to continue efforts to expand Japan's Self-Defense Forces, citing their deployments in peacekeeping missions around the world. While the U.S. has been publicly supportive, many American observers worry that the military buildup could stoke tension in Asia. But Abe didn't mention by name the elephant in the room: China, whose own military expansion and efforts to claim disputed territory are a major factor in Japan's calculations. How to balance support for an ally with the need to maintain relations with China is a signal challenge of America's foreign policy in Asia.

After recounting his visit to the memorial, Abe embarked on a lengthy discussion of how American trade and aid, and especially the importation of American free-market capitalism, had rebuilt Japan after the war. "It was Japan that received the biggest benefit from the very beginning: The economic system that the U.S. has fostered by opening up its own markets and calling for a liberal world economy," he said.

Related Story

A GOP Deal to Give Obama More Trade Power

The intended takeaway for members of Congress: It's time to put your votes where your capitalist rhetoric is, and move forward on the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a major free-trade deal involving a dozen countries on both sides of the Pacific. Abe is in Washington to negotiate with President Obama on the deal, and while they haven't reached a final agreement, both sides said there was progress. As Abe knows, a final deal will also have to win over Congress, and a good number of Democrats oppose it. Particular sticking points include Japanese resistance to cutting agricultural and American carmakers' complaints that the Japanese auto market is effectively closed to them.

Abe took a notably conciliatory tone on agriculture, remembering his own staunch defense of tariffs during negotiations for the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade two decades ago. "I was much younger and like a bowl of fire, and opposed to opening Japan’s agricultural market," he said. "However, Japan’s agriculture has gone into decline over these last 20 years. ... In order for it to survive, it has to change now." But he made no mention of automobiles during his roughly hour-long speech.

Given Japan's two decades of economic stagnation, memories of the 1980s-era panic about Japanese takeover of American companies and landmarks have also faded—perhaps even dimmer than those of World War II. Abe received a warm welcome from Congress, with extended applause and generous laughter for his jokes ("I have lots of things to tell you, but I am here with no ability nor the intention to filibuster," he cracked at the outset). His hopes for congressional backing are premised on the most negative memories already having faded.

Born to Be a Wild Card

Pop quiz: When you hear the term “PSA,” what comes to mind?

Many people will answer: Public Service Announcement. For men of a certain age, another likely response is more ominous (prostate-specific antigen, to be precise). Only a select few will say “Professional Squash Association,” which refers to the organization that oversees squash, a fiercely competitive racquet sport played in an indoor court with a squishy little black ball that goes up to 170 miles per hour.

Related Story

In the United States, squash remains pretty obscure, but it has a realistic chance of becoming an Olympic sport, and the PSA sponsors a tour, organizing more than 200 tournaments annually all over the world. Last week, the tour found its way to Charlotte, North Carolina. In an act of extraordinary generosity, the promoters invited me to participate as a wild-card entry.

In plain English, “wild card” is shorthand for “not good enough to qualify on one’s own merits.” To be sure, my participation wasn’t entirely random. When Richard Nixon was president, I competed in national junior tournaments, and during the Ford Administration, I played on a national championship team in college. (To give some idea of how long ago this was, in our triumphant year, “Afternoon Delight” was the national champion of songs.) After a hiatus of about 15 years, I fell head-over-heels in love with the game again in 2008—with its breakneck speed, its emphasis on both power and skill, its grace and sheer physicality, and, above all, its constant demand for immediate decisions. In squash, it’s not unusual to have five apparently reasonable options from which to choose in less than a second—with two leading to victory and three to catastrophe. The most common question: Play it safe, or take a risk?

You also have to fight as hard as you can while treating your opponent with respect and courtesy: The game is played in very close quarters, and it’s easy to hurt someone with a ball or racquet. They call soccer the beautiful game, but if I had to identify just one sport to show members of some alien species what the human race is all about, I’d nominate squash.

Over the last few years, I’ve played a lot, sometimes in local leagues with pretty strong players. But even if you’re the most avid tennis player, you wouldn’t exactly expect to find yourself facing Roger Federer one day. Still, wouldn’t you like to give that a try? To see what it’s really like, to learn what separates the pros from the rest of us? For two months in advance, I trained as hard as I could, playing at least five times a week, sometimes with Sat Seshadri, a professional from Bombay who now plays in New York.

If I had to identify one sport to show aliens what the human race was about, I'd nominate squash.Arriving at the gorgeous Charlotte Squash Club courts the day before, I felt a lot like the goofy new kid in high school. The professional players obviously knew each other, and were friends as well as competitors. It was a diverse group, with players from Mexico, Egypt, Pakistan, Guyana, Paraguay, Jamaica, Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom. There isn’t a lot of money in the sport: In Charlotte, the winner earned exactly $902.50. The professionals play, and are willing to travel constantly, because they love it—above all the intensity of the competition and the sense of camaraderie. Most of them have been playing since they were kids, and are hooked; it’s what they do.

In Charlotte, the players smiled and joked in the locker room, but they had a palpable sense of seriousness and commitment during practice, with established routines. I sat awkwardly in the corner with my two racquets, thinking that I really needed to get a sense of what the courts were like. A forlorn question hung in the air: Which of them might be willing to play with me? As it happened, one of the professionals was hitting on a court, all by himself, and I worked up the courage to ask him if he might want to play. (In my mind, I might have rehearsed how to pose the question: “Would you like to play with ME?” “Would YOU like to play with me?” “Would you LIKE to play with me?” “Would you like to PLAY with me?” In the end, I opted for hand gestures.)

He turned out to be Dane Sharp, a Canadian. The name might not be familiar, but he’s one of the ten best players in North America. In the world team championships, he played a competitive match against Egypt’s Ramy Ashour, the Michael Jordan of squash. Sharp isn’t quite squash’s Lebron James, but he’s fast as lightning, and strong, and the ball explodes off his racquet like a rocket. As it happens, he’s also a really nice guy.

After I introduced myself, and told him I knew who he was, he asked what I was doing there. Our conversation:

Me (brightly, and like a complete idiot): I’m here to play in the tournament.

Dane: Which tournament?

Me: This tournament.

Dane (unsure he heard me correctly): Our tournament?

Me (quietly): I’m the wild card.

Suitably informed, Sharp suggested that we try a little drill, apparently familiar among professional players. I asked him to explain it, and he seemed to say, “You hit a drv and then a bsst, and then I hit a drp and then a drv, and we do that over and over.”

To me, this was completely baffling. What’s a “drv”? What’s a “bsst”? Where was I supposed to try to hit that small black ball? And how many times could I ask Sharp that irritating question?

Days later, I think I understand. I was supposed to hit a hard drive, the whole length of the court, and then I was supposed to hit a “boast,” which hits the sidewall and then the front wall. He would then hit a drop shot, meaning a soft shot that would drop at the front wall, and then he would hit a hard drive back to me—and then the cycle would start again. Get it?

When the drill didn’t work, Sharp suggested that we play an actual game. In what seemed like five seconds, he got up to 10 points. You need just 11 to win, and I resolved to do all I could to stop him from winning the decisive point, which meant that I would hit as hard and run as fast as I possibly could. Unfortunately, I tripped over my own legs and fell down. (Hard; my elbow is still badly bruised.)

In the actual tournament, my opponent was Jamaica’s Lewis Walters, ranked 105th in the world. Twenty-seven years old, he’s obviously strong and fit, with over 300 professional matches and some big wins against top players under his belt. Desperate for advice, I asked one of the American pros, the former Stanford superstar Sam Gould, what he does when he plays someone who’s a lot better than he is. Here’s our conversation.

Sam (cheerful): I know I can’t win, so I just try to show the audience how good the other player is. I play very long points, with a lot of movement by both of us, so that he can be at his best.”

Me (despairing): My goal here is not to show people how good Lewis Walters is.

Nonetheless, I think I might have succeeded in that endeavor. Squash is physically demanding (far more so than tennis), and despite my training for the tournament, the first three points seemed to take a lifetime. (Could I take a nap in the middle of the match?) Walters is scarily quick, and as I saw up close, professional athletes have an uncanny sense of anticipation. Like chess players, pilots, and doctors, they recognize patterns immediately. So wherever I put the ball, Walters was there, seemingly even before the ball itself was.

This is the cruelty of the sport: the longer a point goes, the more you have to run, and the more exhausted you get. That creates a perverse incentive. If you hit good shots against a good player, you have to keep running (and your body cries out, “No!”). But if you miss, or hit a stupid shot, the point is immediately over, and at least for a few seconds, you don’t have to run (and your body exclaims, “Hurray!”).

The author (r) with Lewis Walters (Cass R. Sunstein)

The author (r) with Lewis Walters (Cass R. Sunstein) Noticing that I didn’t really belong, the audience was definitely on my side, cheering loudly on the rare occasions that I managed to win a point. (I learned a surprising fact: Fist bumps are hardwired into the human psyche.) But my opponent seemed to enjoy running a lot more than I did. It was a romp for Mr. Walters, 11-4, 11-2, 11-5. At least I didn’t fall down. (Evidently energized by the rout, Walters made it all the way to the final, losing a nailbiter to Mexico’s Eddie Galvez.)

In the locker room after the match, I ran into some of the other professionals on the PSA tour, who had watched the proceedings. “Good fighting,” one of them said, adding, “Nice last game.” And then he offered some of the most beautiful words I have ever heard, as if they might be true: “See you around, at another tournament.”

Probably not. But I left Charlotte not only with increased admiration for the unworldly skill and intense focus of professional athletes, but also with real gratitude for their low-key kindness, and for a lucky, brief glimpse into their sense of brotherhood.

April 28, 2015

An Empty Stadium in Baltimore

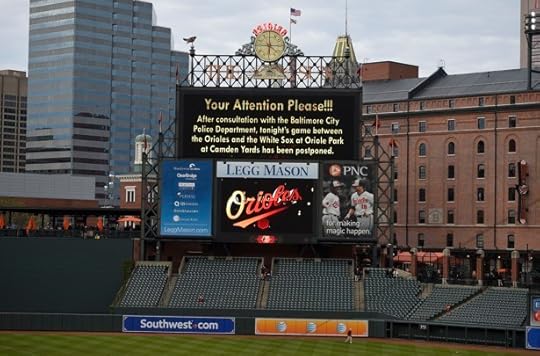

When the Baltimore Orioles host the Chicago White Sox at Camden Yards on Wednesday, it won't really feel like a baseball game. There will be no cheering, and no booing. Nor will there be heckling, hot dogs, or beer. There will be no fans in the stadium at all, in fact. After riots in the city forced the postponement of games for two straight days, Major League Baseball announced that the Orioles will play on Wednesday, but the game will be closed to the public.

Related Story

Two States of Emergency in Baltimore

For a sport that takes significant pride in its history, this may be a particularly sad first: An MLB official told me that after conferring with a historian and several longtime veterans of the game, the league was unaware of any prior examples in which fans have been deliberately barred from attending a game. Those with tickets to the game (or either of the ones postponed) can exchange them for a game later in the season, and they'll still be able to watch Wednesday's contest on TV. The league is also moving the Orioles' next three games to Tampa, where they'll be the "home team" against the Rays at Tropicana Field—a move typically made during emergencies caused by natural disasters, not civil unrest. When rioting erupted in Los Angeles following the Rodney King verdict in 1992, the Dodgers postponed four games until later in the season. More recently, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, forced Major League Baseball to cancel games for a week across the country.

While it hasn't happened in baseball, soccer matches overseas have been played in empty stadiums, although those decisions are usually made to punish a team or its fans for bad conduct. MLB teams in small markets routinely play before crowds so tiny that the stadiums probably feel empty. But this is different.

Baseball, of course, doesn't matter much compared with the pain of parents who lost their son in the back of a police van. It probably isn't a concern to the families of officers injured in the riots, or to shop-owners who've watched their businesses get looted and torched. Nobody made that point more eloquently than the Orioles' chief operating officer (and the son of the team's owner), John Angelos, who wrote in a series of tweets on Monday that the systemic problems that led to Freddie Gray's death make "inconvenience at a ball park irrelevant." Here's a partial transcript, via Deadspin:

Speaking only for myself I agree ... that the principle of peaceful, non-violent protest and the observance of the rule of law is of utmost importance in any society. MLK, Gandhi, Mandela, and all great opposition leaders throughout history have always preached this proper precept. Further, it is critical that in any democracy investigation must be completed and due process must be honored before any government or police members are judged responsible.

That said, my greater source of personal concern, outrage and sympathy beyond this particular case is focused neither upon one night’s property damage nor upon the acts group but is focused rather upon the past four-decade period during which an American political elite have shipped middle class and working class jobs away from Baltimore and cities and towns around the US to 3rd world dictatorships like China and others plunged tens of millions of good hard working Americans into economic devastation, and then followed that action around the nation by diminishing every American’s civil rights protections in order to control an unfairly impoverished population living under an ever-declining standard of living and suffering at the butt end of an ever-more militarized and aggressive surveillance state.

The innocent working families of all backgrounds whose lives and dreams have been cut short by excessive violence, surveillance, and other abuses of the Bill of Rights by government pay the true price, an ultimate price, and one that far exceeds the importance of any kids’ game played tonight, or ever, at Camden Yards. We need to keep in mind people are suffering and dying around the US and while we are thankful no on was injured at Camden Yards, there is a far bigger picture for poor Americans in Baltimore and everywhere who don’t have jobs and are losing economic civil and legal rights and this makes inconvenience at a ball game irrelevant in light of the needless suffering government is inflicting upon ordinary Americans.

The MLB commissioner Rob Manfred said Tuesday that "after conversations with the Orioles and local officials, we believe that these decisions are in the best interests of fan safety and the deployment of city resources." With Governor Larry Hogan deploying the national guard and neighboring states sending in reinforcements, certainly Baltimore police officers have better things to do than protect 20,000 fans at Oriole Park. (Though playing baseball in a burning city is not without precedent, as the Daily Beast's Justin Miller noted.) On the other hand, why not simply postpone this game as well? What's the point of a baseball game without fans? The ballpark will be eerily quiet, a stark contrast to the unrest outside that will undoubtedly affect both the fans watching on TV and the players on the field. It's not how baseball is supposed to be, which suggests that the decision to play the game in an empty stadium is more than just a tactical move; it's a statement about the behavior of a fractured city.

The History of 'Thug'

Last night, as Baltimore erupted with riots and violence and anger, the city's mayor, Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, took to Twitter to share her thoughts on the events sweeping the city. The mayor talked about "the evil we see tonight." She promised that "we will do whatever it takes" to stop the destruction and restore "the will of good." Because "too many people," she said, "have invested in building up this city to allow thugs to tear it down."

"Thugs." "Thug." The derision here—dismissive, indignant, willfully unsympathetic—is implied in the sound of the word itself. Spoken aloud, "thug" requires its utterer first to sneer (the lisp of the "th") and then to gape (the deep-throated "uhhhh") and then to choke the air (that final, glottal "g"). Even if you hadn't heard the word before, even if you had no idea what it meant, you would probably guess that it is an epithet. "Thug" may have undergone the classic cycle of de- and re- and re-re-appropriation—the lyric-annotation site Genius currently lists 12,590 uses of "thug" in its database, among them 19 different artists (Young Thug, Slim Thug, Millennium Thug) and 10 different albums—but the word remains fraught. In a series of interviews before last year's Super Bowl, the Seattle Seahawks' Richard Sherman—who had been described by the media as a "thug," and who is African American—referred to "thug" as an effective synonym for the n-word. And in Baltimore over the past few days, the term has been flung about by commenters both professional and non-, mostly as a way of delegitimizing the people who are doing the protesting and rioting. To dismiss someone as a "thug" is also to dismiss his or her claims to outrage.

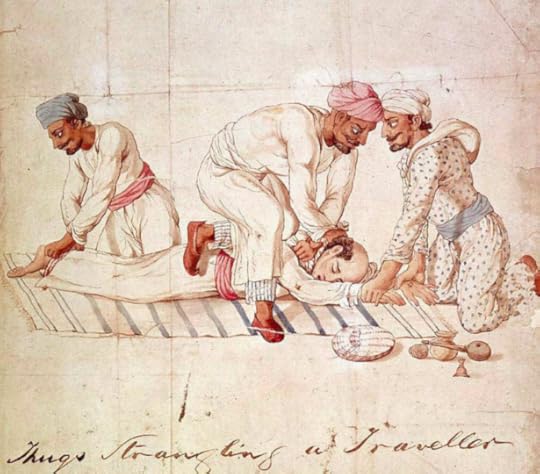

In all that, the history of "thug" goes back not just to the hip-hop scene of the 1990s, to Tupac Shakur and the "Thug Life" tattoo that stretched, arc-like, across his abdomen; it goes back to India—to the India, specifically, of the 1350s. "Thug" comes from the Hindi thuggee or tuggee (pronounced "toog-gee" or "toog"); it is derived from the word ठग, or ṭhag, which means "deceiver" or "thief" or "swindler." The Thugs, in India, were a gang of professional thieves and assassins who operated from the 14th century and into the 19th. They worked, in general, by joining travelers, gaining their trust ... and then murdering them—strangulation was their preferred method—and stealing their valuables.

The group, per one estimate, was ultimately responsible for the deaths of 2 million travelers. Mark Twain, reporting on the Thugs in his book Following the Equator: A Journey Around the World, called the collective a "bloody terror" and a "desolating scourge":

In 1830 the English found this cancerous organization embedded in the vitals of the empire, doing its devastating work in secrecy, and assisted, protected, sheltered, and hidden by innumerable confederates—big and little native chiefs, customs officers, village officials, and native police, all ready to lie for it, and the mass of the people, through fear, persistently pretending to know nothing about its doings; and this condition of things had existed for generations, and was formidable with the sanctions of age and old custom.

The Thugs, indeed, ran rampant in India until the British colonial period, when the governor-general, Lord William Bentinck, heard of them and made a concerted effort to prevent them from operating along India's roadways. According to this fantastic overview of Thuggee history from NPR's Code Switch blog, "nearly 4,000 thugs were discovered and, of those, about 2,000 were convicted; the remaining were either sentenced to death or transported within the next six years." The British overlords had successfully eradicated the network; as William Sleeman, Bentinck's deputy in charge of the effort, proudly declared: "The system is destroyed, never again to be associated into a great corporate body. The craft and mystery of Thuggee will not be handed down from father to son."

The Western fascination with the criminal collective, however, was only beginning. Through Twain's writings about them, and through 1837's vaguely anthropological Illustrations of the History and Practices of the Thug, and through Philip Meadows Taylor's 1839 novel Confessions of a Thug, "thug" entered the English language and the British and American consciousness. It came, through the authors' portrayals of systematized violence, to take on the connotation of "gangster"—a sense of the word that would get another moment of life in the popular culture through 1984's Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, which finds its hero rescuing a group of children who have been abducted by the Thugs.

Mark Twain noted that all of human history has found "Thugs fretting under the restraints of a not very thick skin of civilization."More recently, as NPR notes, there have been attempts to reclaim (or re-reclaim, or re-re-reclaim) "thug" through heavy irony. There's the blog Thug Kitchen, which is dedicated to the sharing of healthy recipes and cooking tips. There's "thug lit" in publishing, which refers to fictional genres that have yet to break into the mainstream. There's the web series Thug Notes, which features a character named Sparky Sweet explaining classic works of English literature." (Sparky's summary of Heart of Darkness: "When it comes to swinging ivory for clean dollars, this fool Kurtz got the Congo sewn up.") There are all those "thug life" memes.

Given all that: Who is a thug? Who is not a thug? "The thug," the Brown University professor Tricia Rose writes in her book The Hip Hop Wars, "both represents a product of discriminatory conditions, and embodies behaviors that injure the very communities from which it comes." Thugs, in this conception, are both victims and agents of injustice. They are both the products and the producers of violence, and mayhem, and outrage. So it is fitting that, as the word's history suggests, there is—contrary to Mayor Rawlings-Blake's claims last night—a kind of universality to thuggery. Thugs are not necessarily "evil"; thugs are not necessarily opposed to "the will of good"; thugs are not necessarily unsympathetic. Which is another way of saying that thugs are human. And, being such, they evolve. Mark Twain, in Following the Equator, noted that all of human history, on some level, has found "Thugs fretting under the restraints of a not very thick skin of civilization."

He continued:

We have no tourists of either sex or any religion who are able to resist the delights of the bull-ring when opportunity offers; and we are gentle Thugs in the hunting-season, and love to chase a tame rabbit and kill it. Still, we have made some progress—microscopic, and in truth scarcely worth mentioning, and certainly nothing to be proud of—still it is progress: we no longer take pleasure in slaughtering or burning helpless men. We have reached a little altitude where we may look down upon the Indian Thugs with a complacent shudder; and we may even hope for a day, many centuries hence, when our posterity will look down upon us in the same way.

The Bruce Jenner Learning Curve

Bruce Jenner’s 20/20 interview about being a transgender woman has prompted all kinds of different reactions, but from people in the entertainment industry, the public response has in general been positive. The Kardashians have each voiced support for the person whom they’d come to know as the family patriarch, and many other blue-checkmarked Twitter users have expressed admiration for the difficult announcement the former Olympian made.

But yesterday, the actress Alice Eve, of Entourage and Star Trek: Into Darkness fame, had some not-so-supportive things to say. Referring to Jenner on Instagram, she wrote,

Nope. If you were a woman no one would have heard of you because women can’t compete in the decathlon. You wouldn’t be a hero. You would be a frustrated young athlete who wasn’t given a chance … Until women are paid the same as men, then playing at being a ‘woman’ while retaining the benefits of being a man is unfair. Do you have a vagina? Are you paid less than men? Then, my friend, you are a woman.

At first, it might seem as if Eve was outing herself as part of the “radfem”—"radical feminist"—community, whose controversial philosophy portraying transgender people as interlopers was traced last year by Michelle Goldberg in The New Yorker. But Eve’s comments apparently weren’t so thought through, and soon she began walking back the idea that people like Jenner don't get to define who they are. Instagram followers began calling Eve out—"Your notion that Jenner is 'playing' at being a woman is honestly disgusting," "This is transphobia at its finest"—and in the comments, Eve responded: “"I do agree that the struggle for transgenders is unique and horrific. However, I do want to also support a cause I strongly believe in, the right for women to have equal rights to men. The transgender equality struggle is the next one, as we all know. And very real it is, too."

This, too, was not a fully baked opinion. How does accepting Jenner set back women’s equality? Who decides which struggle is "next" versus which one is "now"? She followed up by posting pictures of the Harnaam Kaur, the British “bearded lady” and body-confidence activist, and of David Bowie, that icon for ambiguity. Neither of those people say they are transgender, and when Eve wrote “I am a supporter of anyone who wishes to explore their gender identity” on the Bowie picture, she still seemed to be missing the point: When Jenner goes on national TV and says “I am a woman," he’s not “exploring”—he’s explaining.

She deleted her initial post and replied to one of the many commenters criticizing her by saying she just wants to “refine the language on this topic”—despite the fact that there's already a vigorously debated set of terms to use on this topic, and that her end goal still seems to be defining Jenner outside of the term "woman." But more significantly, she said this:

Maybe this needs a little thought. Thank you for engaging with me on this subject, because I felt confused and now I feel enlightened and like I know what education I need to move forward. I appreciate the time and thought. #smartbunch

Is this, maybe, what a happy ending looks like for one of those Internet outrage cycles that are so fashionable to bemoan lately? Eve said something uninformed and hurtful to many people, and those people told her why they took issue with it. She still hasn't hit upon a particularly coherent point of view, but she is, in public, evolving, learning, and listening. Should she have done some research before making an inflammatory statement about a topic on which no one asked her opinion? Of course. But this is what the Internet does—it allows people to speak their minds, but it also holds them accountable for what they say.

And this is what something like the Jenner interview does: As the most visible and famous transgender “coming out” moment in American history, it's forced many people to think about a struggle that they hadn't considered before. The conversations that ensue are likely to be awkward, but they're also likely to be productive. “What I'm doing is going to do some good,” Jenner told Sawyer when she asked why he chose to go public. In her roundabout, foot-in-mouth way, Eve has just proved him right—for people who are both movie stars and not, it's time for an education.

The Day After: Cleaning Up in Baltimore

On Tuesday, Baltimore residents began to clear the wreckage of rioting and fires that erupted the day before, after the funeral of a 25-year-old black man who died in police custody. Riot police and National Guard troops stood guard on the smoldering streets after protesters after protesters torched cars and buildings and looted stores. Nineteen buildings and 144 vehicles were set on fire, and 202 people were arrested, according to the mayor's office. People around Baltimore formed volunteer clean-up crews on Tuesday to help affected store owners, repair damaged structures, and clean streets strewn with debris.

On Tuesday, Baltimore residents began to clear the wreckage of rioting and fires that erupted the day before, after the funeral of a 25-year-old black man who died in police custody. Riot police and National Guard troops stood guard on the smoldering streets after protesters after protesters torched cars and buildings and looted stores. Nineteen buildings and 144 vehicles were set on fire, and 202 people were arrested, according to the mayor's office. People around Baltimore formed volunteer clean-up crews on Tuesday to help affected store owners, repair damaged structures, and clean streets strewn with debris.

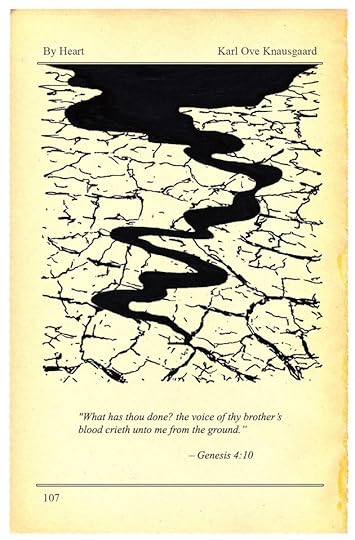

Karl Ove Knausgaard on the Power of Brevity

Doug McLean

Doug McLean Karl Ove Knausgaard isn’t known for being brief. My Struggle—his celebrated six-volume, 3,600-page autobiographical novel—is an experiment in radical scope, a kind of literary ultra-marathon. How long can a narrator extend a moment?, he seems to ask. How much banality can a story include? How long can a novel digress and still remain compelling?

Related Story

How Writers Can Grow by Pretending to Be Other People

In our conversation for this series, though, Knausgaard chose to examine the biblical story of Cain and Abel—a text he admires for its extreme compression. We discussed the story’s extraordinary economy, its multivalence, and the eternal appeal of family as a subject. (Cain and Abel’s themes—family, ambition, violence, shame—are Knausgaard’s own.) Finally, he gave insight into the process he used to write My Struggle: a willed naivety, a way of writing without thinking, that he compares to improvising music.

My Struggle is being serially translated into English, and the latest volume—Book Four—comes out Tuesday. This installment focuses on 18-year-old Karl Ove’s first job as a schoolteacher in a Norwegian fishing town. Living alone for the first time, he makes his first stumbling forays into work, writing, self-determination, and sex. It’s a story told with a comic grimace—the mature narrator bears unblinking witness as a young man’s overblown ambitions are cut down, one humiliation at a time.

Knausgaard’s work has been translated into more than 15 languages. In addition to the widely-praised My Struggle series, he is the author of Out of This World and A Time For Everything. He lives in Sweden and spoke to me by phone.

Karl Ove Knausgaard: I first heard the Cain and Abel story at school, when I was seven or eight. My teacher told it to our class, and it very much made an impression on me. I returned to it later when I was writing a novel which is set in the Bible, so to speak, and I re-read all those stories again. I was struck by how extremely small it was, just 12 lines or something. It was almost shocking to see that this little story could have such an impact, and become the big story about killing, violence, jealousy, brothers—so many huge topics within the culture.

I need 300 or 400 pages to say something significant. I need space to express simple, banal truths—I don’t have the ability to express them without that space, and a novel for me is the way of building that space. But Cain and Abel always surprises me in the way it manages to be both extremely powerful and extremely short.

In some ways, this concision is typical of the Old Testament. If you look at other very important texts—say, The Odyssey—it’s often different. The Odyssey is very loose and very long, and it’s a completely different way of storytelling. You have that looser, longer form in the Bible, too, but not in this story. In the Bible, if it’s very important, it’s very short. If it’s not important, it’s very long. That’s a rule in almost all texts.

I was invited to be a consultant for the New Norwegian Bible translation of this story. They made lots of different bibles available to us—the King James, of course, but also Swedish bibles, Danish bibles, old Norwegian bibles. The fun and most interesting thing for me was that we had a bible-translation computer program that made all these different editions available. We could click on a single word and get a translation of it. This helped me get closer to the Hebraic original, which was extremely useful during the work with the text.

The Hebrew text is very raw and very direct—almost impossible to translate. I tried to keep as much of that intact. That version has tremendous power because it’s so simple, with the same words coming over and over again in this short passage: earth, blood, faith. The language is so archaic and interesting. Though I haven’t shown this to anyone who’s mastered the language, so I may get everything wrong, this is my sense of the Hebrew original, when Cain has seen his sacrifice rejected by God:

It burned in Cain and his face fell.

Jehovah said to Cain: “Why do you burn, and why does your face fall?”

The simplicity, and the complexity in the simplicity: It’s bottomless. These are texts people have written about for thousands of years, and keep having different kinds of understandings about. The text is so rich and complex that you can take out one element and look at it, and find it expresses something deeply true. It can support all kinds of different interpretations depending on the way you live, or when you live, or who you are.

For instance, I became very interested in the way looking is described in the text. Jehovah looks down at Abel instead of Cain, and that’s when the jealousy begins. As a result, Cain’s face falls—another way of looking down. Jehovah then tells him, “Look up, because if you don’t look up evil will creep at your door.” I interpret this as being about the obligation of looking up at others, of facing the other. To look down is to not face your community—to be alone, to exist outside of society—and, as we see in this story, that is dangerous. I wrote about this when I wrote about the killing in Olso and Utoya three years ago. He [the mass-murderer Anders Behring Breivik] looked down. And if he planned this massacre with someone else, it would have stopped him. It would have been impossible. He could only do it because he was alone.

All those kinds of relevancies exist in this text. You may say that you reduce it when you use it as a psycho-sociological thing, but I don’t see it like that. I see it as the opposite. You can take one element out and look at it, and let it express something deeply true—without diminishing other potential interpretations, or the text’s overall richness and complexity.

I need 300 or 400 pages to say something significant. I need space to express simple, banal truths.This piece could also be about a basic moment in human history: the first murder, and its connection with sacrifice. The story shows us that sacrifice is meant to take the place of violence. The sacrifice Jehovah wants to see is the sacrifice of Abel’s sheep, which is blood—not the vegetables Cain grew. The next thing you know, Cain’s killed his brother—which is not just blood, but his own blood, spilled on the earth. This brings us in a direct circle back to the sacrifice. When he wrote about this story, the French philosopher Rene Girard wrote that sacrifice—symbolic violence—is an act meant to replace transgression against life. It unites us as a “we.” Without it, there is no “we”—and Cain turns against Abel, brother turns against brother. Symbolic blood becomes real blood. Inside a society, that’s a very dangerous thing.

Of course, it’s a story about family, too. And though I don’t reflect on themes when I’m writing, it’s obvious to me that I’ve always been writing about family. I think it’s because I’m interested in identity—and the family is the first group of people who form your identity and sense of self.

When my last daughter was born, I saw what happened when she was lifted up in the first seconds of her life. She was just by herself. She hadn’t met anyone. But she was lifted, held onto by the neck, and looked at by my wife, and by myself. Those kinds of bonds are the first you have, and you’ll always define yourself in relation to those few people. Later, you’ve got your larger community. You’ve got your nation, and your profession. But it’s all layered on top of this core. The core is the same, no matter what.

I wrote my own version of the Cain and Abel story because I wanted to write about brothers. There’s a lot of me and my brother in that retelling of the story. I’ve always been interested in writing about all those mixed feelings brothers have: your jealousy, and hatred, but always a kind of unremitting love. My brother could do anything he wants—but no matter what kind of horrible thing he does, he would still be my brother. And I think it’s the same way with him.

Part of it is because it’s always been us against our parents—the bond there of coming from the same place, but still being very, very different. When so many qualities are the same, but so much is different, it allows for the kind of compression you see in the Cain and Abel story. It’s a very good place to write from. It’s also a story about losing complete control. Because losing control is the worst thing you can do, and no one wants to do it—I’m sure about that. What is it to lose control so completely?

In a completely different sense, writing My Struggle has been an exercise in giving up control. Every morning now, I write one page. I get up early and write one page in two hours. I start with a word. It could be “apple” or “sun” or “tooth,” anything—it doesn’t matter. It’s just a starting point—a word, an association—and the restriction that I write about that. It can’t be about anything else. Then I just start, without knowing what it’s going to be about. And it’s like the text produces itself.

I’m not talking about quality. For God’s sake, no. It’s not like this text ever looks good or anything. It’s just sitting there writing. Not thinking, and writing. I think it’s a state of mind, one I usually compare with music. When you watch musicians, they’re not thinking about what they’re doing, they’re just playing. Well, the same thing can be with writing. It’s just writing.

When you are not aware of yourself, you start to write things you have never thought about before. Your thoughts do not take the path they would normally have followed, and the thinking is different from your own. The language is in you, but it’s out of you, and it doesn’t belong to you. That’s what literature can do—when you throw something in, something else comes back.

This approach was something I discovered very early on, when I first started to write with ambition. I was 17, 18. I just wrote. I didn’t think. It wasn’t hard, because I was so naive and innocent. But what I mostly did was spit out clichés.

Later, I had many years when I couldn’t write because I felt I knew too much—suddenly, I had a notion of quality. But when I was 27 or 28, I had a new experience for the first time: I just disappeared somewhere. I just wrote and followed the text. It was like reading, basically. I knew I was onto something because I couldn’t predict what was coming and I couldn’t identify it with myself when I read it—it was outside my normal reach, in a way. Not that it was better. But it was different.

This is what makes my work so difficult for me to read and see again. The first thing I think is—oh Jesus, it’s naïve. But in that naivety there is something that’s very direct and true, in a sense.

There’s a difference between writing naively now and when I was 20. When you’ve been writing for 20 years, you know something about writing. You don’t have that knowledge present as you work, but it is still there somewhere and kind of directs you.

Now I have to learn to write differently. I can’t repeat what I did in My Struggle.For My Struggle, the revision process developed during the process of writing those six novels. I edited the first novel with my editor—we did it like a classical novel, more or less. It wasn’t hard. There were some bridges made, and then it looked like a novel. But the second book we hardly edited at all. Much of the editing I’m doing while I’m writing, so when I reached the end—we just kept it, basically. We took out some pages, of course, but it was mostly there. The other books were written in a similar way, with the exception of Book Six—that was so long we needed to take out 150 pages. The others are more or less left alone.

But now I have to learn to write differently. I can’t repeat what I did in My Struggle. It’s become a kind of technique: I write a little bit about how I feel about something, a little bit about failure or shame for something, and then there is a reflection of a more essayistic kind, and then there is a description of something ordinary, and so on. I can’t write that way for the rest of my life. I would be less and less satisfying for myself because there’s nothing new in it. Or, the subjects can be new, but the insights are exactly the same.

What I’d really like to do is think differently, but that’s impossible.

Starting to write differently will be very difficult. Maybe it will create a kind a vacuum where it will be impossible to write. That has happened before. It will happen again. And it will pass again.

The privilege of a novelist is that you’re able to sit for three years by yourself, and no one’s interfering with anything if you don’t want them to. If you have faith in your writing, it’s easy. It’s when you remove that faith that things become difficult—when you start to think, this is stupid, this is idiotic, this is worthless, and so on. That’s the real fight: to overcome those kinds of thoughts. When you start a novel—well, 99 out of 100 novels start in a stupid way, I’m sure. You need to go on so that it can become something. Maybe it will take 50 pages, or 100 pages, but it will be okay.

When I go to bed, I look forward to the next morning because I know I have these two hours to write. It’s a magical place. And I know it’s going to happen. I can trust it.

Blur Takes on the World

Damon Albarn of Blur isn’t a fan of what’s on the radio these days. "Look at music now,” he told The Sunday Times earlier this month. “Does it say anything? Young artists talk about themselves, not what’s happening out there. It’s the selfie generation. They’re talking platitudes."

Is that the sound of a middle-aged musician making like middle-aged musicians everywhere and sniping ignorantly at Kids These Days, or is it a valuable critique of the vapid mainstream? Take your pick. In either case, Albarn's comment is also a salvo in that universal record-geek bargument over whether lyrics truly matter. The reasonable answer is “sometimes” or “it depends”: Many classic songs have nonsense words, and many decent ones have been elevated by their poetry. But Albarn speaks for a lot of people when he implies that, in general, culture is worse off when songwriters just spit out cliches and faux-introspection instead of trying to communicate something about the wider world.

The irony is that Blur offered one of the all-time-great pieces of evidence in favor of the idea that it doesn't matter what music says: The woohoo-laden “Song 2” tried to parody U.S. rock radio and ended up ruling it, with most American listeners never getting that the joke was on them. In Britain, where Blur were far more popular than in the States, the band's subversive edge has been more widely understood. But with the release of The Magic Whip, Blur's first album in 12 years, much of the coverage on both continents has focused on Blur as Blur, rehashing the old Britpop mythology and puzzling over the relationships between the members rather than focusing on what Albarn’s music says.

Then again, parsing his musical messages can be complicated. The Magic Whip came about spontaneously, when five days of downtime in Hong Kong during a Blur tour turned into a studio session. Somewhat controversially, the recording location seeped into the album both visually—Chinese lettering on the album cover, Chinese cooking in the first music video—and lyrically, with references to Asian locales from the Java Sea to Kowloon. Albarn has called the album “political” and says the title is a metaphor for power; bassist Alex James told The Quietus that the foreign environment imbued the band with “the sense of time pressure and urgency, the claustrophobia from being in a unknown place overseas.”

You can hear those ideas most clearly on The Magic Whip's slower songs. “New World Towers” sees Albarn marveling at the colors of a glowing skyline; “Pyongyang” achingly describes “the pink light that bathes the great leaders” of the North Korean capital; “There Are Too Many of Us” conveys in its title the claustrophobia that James talked about; “I Thought I Was a Spaceman” imagines a time when sand dunes have covered London's Hyde Park. The words, overall, are impressionistic; the uniting emotions seem to be wonder at unfamiliar sights, isolation amid crowds, and anxiety about the environment.

Do those thematic concerns make the album good? No—the music does. Blur has always stood up for the idea that rock arrangements can be quirky without being alienating, and The Magic Whip continues in that tradition, offering crisp tunes with sprinklings of strange. The opener, “Lonesome Street,” is a prime example, featuring chugging guitar with burbling background noises, newscaster yammering, and Beatles-esque vocal refrains. For a similar busy-city effect, “I Broadcast” grafts the giddy vibe of The Romantics’ “What I Like About You” onto a bed of electronic pings. The best track and lead single, “Go Out,” rides a “My Sharona”-esque riff through a cloud of dissonance as Albarn moans tiredly, evoking masses of weary people lurching toward a local pub.

Listening to these songs, you get snippets of concrete, on-theme lyrics—“too many Westerners” crowd the bar of “Go Out,” sweat-shop consumerism shows up on “Lonesome Street,” images of melting tarmac sit between campfire-ready “la-la-la”s on “Ong Ong.” But besides the swirling-strings overpopulation ballad “There Are Too Many of Us,” the only song where Albarn’s message needs no decoding is “My Terracotta Heart.” Over a clock-like rhythm and spindly guitars, he sings about his relationship with guitarist Graham Coxon, a relationship that was severed more than a decade ago and has only been tentatively repaired. "Is something broke inside you?" he asks, movingly. "Because at the moment I'm lost and feeling that I don't know If I'm losing you again." You might note that this is the exact kind of lyrical style—personal, possibly platitudinal—that Albarn wishes fewer people would indulge in. But amid the abstractions of The Magic Whip, it's a reminder of when, exactly, words really do matter.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower