Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 433

May 12, 2015

Obama Loses the First Battle of the Democratic Trade War

On Tuesday, the Senate failed to overcome a Democratic filibuster blocking “fast-track” Trade Promotional Authority from coming up for debate. For the past week, President Obama’s toughest opponent in his uphill struggle with Democrats over trade legislation has been Elizabeth Warren, the progressive leader who continues to fight the president even though she doesn’t want to be president. But it turns out that the president’s most difficult obstacle is not Warren but Harry Reid, his erstwhile ally and the Democratic leader in the Senate.

In opposing the trade bill, Warren has accused Obama of asking Congress to “grease the skids” for an international agreement that is being negotiated in secret and boosts corporations at the expense of workers. She’s even suggested that a pending trade deal with the European Union could unravel Obama’s prized Wall Street reform law, Dodd-Frank.

Warren has gotten under Obama’s skin to a degree that many of his Republican critics have not. “She’s absolutely wrong,” the president told Matt Bai of Yahoo News last week. Obama repeatedly referred to the first-term Massachusetts senator as “Elizabeth”—a tic probably meant to highlight their enduring friendship but which may have come across as condescending. And as if to further diminish a woman who has taken on the status of icon in some liberal circles, the president tossed around a pair of words—“law professor” and “politician”—that Republicans routinely use to knock him down a peg or two. (Remember, there is nothing a politician hates more than when another politician calls them out for being a politician.)

The truth of the matter is that Elizabeth, you know, is a politician just like everybody else. She’s got a voice that she wants to get out there, and I understand that. On most issues, she and I deeply agree. On this one though, her arguments don’t stand the test of fact and scrutiny.

The White House always understood trade authority would be a tough sell with Obama’s liberal base and that Warren would probably emerge as a leader of the opposition. With Republicans broadly supportive of the legislation, all the administration needed was a handful of Democrats in the Senate and a few dozen in the House to secure package. Yet on Tuesday, the bill failed in its initial attempt to clear even that low threshold.

Reid has made clear for months that he would vote against Trade Promotional Authority, but there is a big difference in Congress between a legislative leader who opposes a piece of legislation and one who plans to use his power to kill it. Administration officials told me they were confident Reid wouldn’t actively try to torpedo the bill, pointing to a statement he made in December that he wouldn’t “stand in the way” of Obama’s push for trade deals with Pacific and European nations. But they grew more concerned watching Reid rally nearly the entire Democratic caucus, including several pro-trade senators, to block Mitch McConnell’s attempt to bring the fast-track bill to the floor.

The president’s most dangerous Democratic opponent on trade is not Warren but Harry Reid, his erstwhile ally and the party leader in the Senate.Reid first threatened to stall the trade bill until Republicans brought up unrelated legislation to extend the Highway Trust Fund and reform the Patriot Act. In recent days, however, he’s pushed McConnell to package Trade Promotional Authority with other bills that would crack down on currency manipulation and provide assistance to workers who lose their job because of trade deals. McConnell has resisted, promising only that those measures could come up as amendments but not guaranteeing their passage. Without that assurance, Democrats banded together and defeated a procedural motion on Tuesday afternoon.

A Senate Democratic aide on Tuesday insisted that Reid was not trying to kill Obama’s trade bill—he just wanted to improve it and get as much as he could from Democrats. “Everyone here assumes trade will pass eventually,” the aide said. “The goal right now is to use our leverage to secure a better deal. It’s that simple.” Josh Earnest, the White House press secretary, also downplayed the development. “It is not unprecedented, to say the least, for the United States Senate to encounter procedural snafus,” he told reporters. (When ABC’s Jonathan Karl pointed out that “snafu” is an old World War II military acronym meaning “Situation Normal, All Fucked Up,” Earnest smiled and replied, “This is a family program, Jonathan.”)

Progressive activists opposed to the trade deal celebrated Tuesday’s vote, but they aren’t taking Tuesday’s vote as a definitive victory either. “The hundreds of thousands of activists who have rallied behind Senators Warren, Brown, and Sanders to defeat the [Trans-Pacific Partnership] will not rest until it is dead, buried, and covered with six inches of concrete,” said Charles Chamberlain, the executive director of Democracy for America. “We know the forces pushing the job-killing TPP won’t stop here, and they should know, neither will we.” Jim Kessler, vice president for policy at the centrist think-tank Third Way, shot back: "This is not close to being over."

Obama has fought progressives before and won, most memorably in his efforts to pass mediocre fiscal deals that they believed gave away too much to Republicans. But this struggle is different, and more reminiscent of the failed push that President George W. Bush made, during the twilight of his own presidency in 2007, to get enough Republicans to join the Democratic congressional majority in supporting comprehensive immigration reform. Then as now, immigration was a flashpoint for conservatives who feared a repeat of the broken promises made 20 years earlier by a president of their own party, Ronald Reagan. Democrats invoking the passage of NAFTA under Bill Clinton are invoking similar fears on trade. Barbara Boxer, the veteran California liberal, said in a floor speech that she was “suckered” into supporting fast-track authority—which helped expedite the NAFTA talks— in the late 1980s and came to regret it. “They’re making all these promises,” she said of the current TPA push, “and the more I hear it, the more I hear the echoes of the NAFTA debate.”

Just like Bush, Obama is finding that his powers of persuasion within his own party are dwindling the closer he gets to retirement. And while attention shifts to the campaign to replace him, he has gotten no help—so far—from Hillary Clinton, whose position on the trade deal is one big hedge. The setback in the Senate for Obama’s cause on Tuesday may be temporary, and either Reid or Clinton can still step in to turn momentum back in his favor. But without their assistance, another one of the president’s major second-term priorities could be doomed.

Why Is John Kerry in Russia?

Tuesday seemed like a particularly strange day for Secretary of State John Kerry to pay the highest-level U.S. visit to Russia in nearly two years. The ceasefire in Ukraine hasn’t stopped the daily violence between pro-Russian separatists and Ukrainian troops. The Russian-backed regime of Bashar al-Assad in Syria is reportedly dropping chlorine bombs on civilians again, despite a Russian-brokered deal requiring Syria to destroy its chemical-weapons stockpiles. And, earlier this week, the United States was the most prominent of Western countries to not to show up to Russia’s Victory Day celebrations commemorating the end of World War II.

Nevertheless, on Monday, Kerry’s trip was announced, with discussions about Iran, Syria, and Ukraine reported to be on the agenda. “This trip is part of our ongoing effort to maintain direct lines of communication with senior Russian officials and to ensure U.S. views are clearly conveyed,” read a State Department press release.

The Russians were quick to convey their views as well. “His [Kerry’s] visit began on an inauspicious note after the Russian Foreign Ministry issued a lengthy statement on Monday castigating the Obama administration for trying to isolate Russia,” reported Michael Gordon of The New York Times. On Tuesday morning, Kerry and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov

Writing Should Be a Continued Exploration

Doug McLean

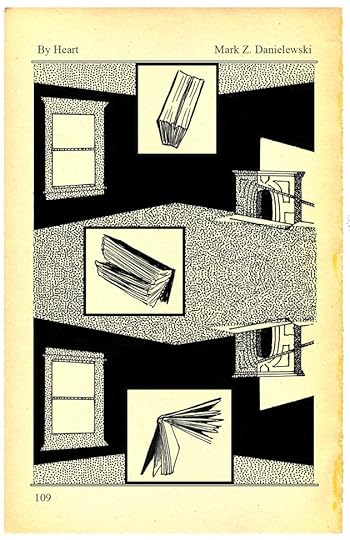

Doug McLean Some books teach you how to read them as you go. When I spoke to Mark Z. Danielewski—whose bestselling 2000 debut, House of Leaves, used a meta, multi-stranded narrative to lure the reader inside a shapeshifting haunted house—we discussed Richard McGuire’s Here, a graphic novel that employs a unique visual language to show a single plot of land changing over thousands of years. We discussed Danielewski’s attraction to books that invent their own narrative grammar, and why he’s committed to writing books that combine image and text without privileging either.

Related Story

Writers Should Look for What Others Don't See

Danielewski’s latest project is a whopping, 27-volume series called The Familiar, of which the first volume, One Rainy Day in May, comes out Tuesday. The book is a visual feast, and no two pages look alike. Throughout, Danielewski blurs the line between text and image, with full-spread illustrations made up of tiny letters. Images and epigraphs abound. There are nine narrators, each with a unique font and color-coded quick-reference tab. And Narcons—a fleet of artificially intelligent robots that serve as the book’s “objective” narrative device—butt in with factual asides. On the surface, the plot is simple—an epileptic 12-year-old named Xanther goes to buy a family pet and comes home with a creature we suspect is very dangerous. But as the narration stretches from Los Angeles to Singapore to Venice, Italy, there’s something else at stake: Danielewski wants to show the awesome, terrifying scale of a single earthly day.

Danielewski’s previous novel, Only Revolutions, was a finalist for the 2006 National Book Award. He lives in Los Angeles and spoke to me by phone.

Mark Z. Danielewski: Here is one of those books that just kept murmuring to me in the background. After I published my Only Revolutions—which features two teenagers moving through two hundred years of time—people kept mentioning this 1988 strip by Richard McGuire. I remember filing it away in my mind somewhere. Oh, that’s an interesting idea: being, as a reader, localized in one place and yet accelerating through an enormous amount of time.

Then Here, the book version, was published, and I started to hear from friends. I got a text from Gus Van Sant asking me if I’d read this book. I asked him what he was talking about, and he told me all about it, but I was in the middle of something and promptly forgot the conversation and went about on my merry way. Then I was in the offices of Pantheon, talking with Andy Hughes about various production details—and he started talking about Here.

It was at this moment that I just felt sort of embarrassed—the sense of shame you get when you know you should have read something a long time ago.

So I started to read. And when I realized how rapidly I was moving through it, I purposefully stopped. I understood that I could swallow this whole thing at once, so I decided to only read 10 pages a day. It became this slow, incredibly enjoyable experience for me. In the midst of the enormous amount of stress that goes with not only preparing Volume I [of The Familiar] and finishing Volume II, I found I could lose myself. I could transpose myself into the same place and a different place, and I loved sitting on the couch reading and looking out the window, imagining a kind of similar historical logic to everything around me.

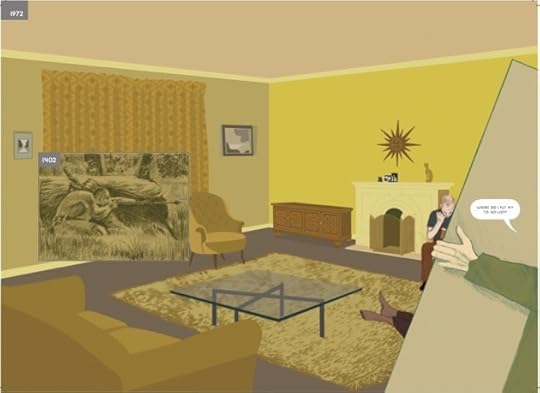

I’d describe the book as looking at a corner of a room and imagining all that took place there, whether it was the year 1553 or 1203 or 500,000 B.C. or 1955 or 2015 or 2315. Inset panes open up inside the room allowing us glimpses into what was happening in that very spot years ago, or years from now. The corner is also materialized by McGuire’s placing it almost always in the center of the spread: Since we usually hold a book so its pages are at an angle, we physically create the room’s walls when we open the book. We create physically that experience of this dead-end corner, and yet through it we not only open up the room of the book itself, but also see through the book into the wider world. And I think Here is very much about that. As much as it materializes opacity, it constantly pushes towards transparency—windows, and mirrors, and panes through which to look.

It’s very much like music in that you can quote music in terms of its melodies or its themes, but in order to really appreciate certain passages you need to experience them in context:

Richard McGuire

Richard McGuire  Richard McGuire

Richard McGuire  Richard McGuire

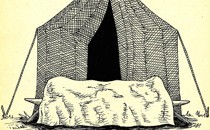

Richard McGuire I’d call this excerpt the arrow passage. It starts with a Native American man hunched behind a large log or rock, getting ready to fire an arrow—presumably at prey. Then over the next few pages, we track this arrow as it flies through space. As it moves from left to right across the page, this arrow is also moving through time and space in a linear fashion. So it’s this unifying idea of directionality, of temporality—but at the same time, there’s a sense of humor about it because, as the arrow floats across the page, we’re also privileged with glimpses at what it looks like in 3,500,000 B.C., or 1870, and 1920, while children play pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey.

On every page, there are all these visual echoes going on. The pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey game and the arrow seeking its mark. The deer (presumably) being shot at, the deer being hung on the wall. In fact at the end of this sequence the taxidermy replaces a clock—an interesting comment on time itself.

Concurrently, you have this Native American woman in 1352, approaching a lake. And instead of being transfixed by her image in the water, she dives in—the water isn’t a reflective surface, it’s something to plunge into, through. That’s what the book as a whole is constantly refiguring: As much as we can find our reflections in these panes, we can also dive into them, past them. That’s the potency of Here—a room is far more than the walls we’ve built; it’s a here and now alive with transcendent echoes of a world that’s constantly and continuously changing.

This section has no words:

Richard McGuire

Richard McGuire It’s a woman standing at the window. She may have just closed the window, she may be about to open it. There are no curtains. It’s all in 2014. And we see her shadow cast across the fireplace. In the middle, going across the spread is this beautiful pane that just shows the forest and stream and again there’s this little bit of reflection in the water, inviting us to look beneath it but at the same time denying us. Our bodies cast a shadow, but nature doesn’t—instead, it throws light. That idea is constantly in this book: The natural world casts light on where we are, and who we are, and what we’re becoming, and what we’ve been.

I love the wordlessness of it all, which may be a strange thing for a novelist to be saying. And yet I still find that there is a kind of textuality to it. I feel like there are sentences here, they’re just written out in a language that we’re not yet familiar with. Or we’re intimately familiar with, we just don’t recognize it yet as a language. The experience of the book is that, as you move through these images, you begin to understand there is a syntax. There is a grammar, and as we start to become fluent in it, we behold the world in a greater way.

I love texts that confront us with new grammar in this fashion, teaching us new ways to read and interpret as we go. I mean, we still don’t know how to read the world we’re in. We’re surrounded by a vast, nuanced, complicated text—our universe—and so any work that challenges us to open up the way we perceive things is something I adore. And Here is one book I adore all the way from its concept to its enactment.

What draws me is the dance between the visual and the textual. I don’t think I’m unusual in that way. Developments in the 60s and 70s started making it easier to access colors and different fonts, and things that were always so out of reach were suddenly in everyone’s hands, and I am one of many writers who found that very exciting. School taught us that these are things we can’t do—we have to scribble within the boxes, write cursive on lines—and yet suddenly new technologies enabled us to return to that place before school, when we could draw beyond the boundaries with colored pencils and pens. I was fortunate to be born in a time of such advancements, as well as somehow personally afflicted with a willful orneriness that said—I’m not going to give up writing this way, or exploring this way. The fruits lie before you. Eat if you dare.

We’re surrounded by a vast, nuanced, complicated text—our universe—and so any work that challenges us to open up the way we perceive things is something I adore.People over the years have constantly asked me if I’m a postmodern writer, or a deconstructionist writer, or whatever phrase was at hand. I finally decided I would invent a terminology myself: I describe my work as “signiconic,” which is a word that combines “sign” and “icon.” What signiconic writing does is embrace the possibility of engaging the mind not only on a visual level but on a linguistic level as well, and at the same time, without ever letting either side claim dominance. We can be completely immersed in text. And we can be completely intoxicated by the visual—whether it’s a television screen or an Instagram feed. But by engaging both at the same time, you destabilize both sides, and open the mind up to many other perceptions—even a third perception, if you will. My exploration is with how text and image can approach this place where both of them kind of fall away, allowing the reader to begin to sense a world beyond our purely retinal limitations or our syntactical, synaptic limitations.

At some point I made a choice that my writing would be a journey, an adventure, a continued exploration. Whatever repetitions took place, they would be through the reiterations of my own evolving (or devolving) mind and body. When I finished House of Leaves I had to ask myself: Do I want to stay here? Is this where I live? Is this the territory that I staked out and I’m going to stay within? No, I decided I wanted to move further out. House of Leaves, for me, had a very personal and limited feel—much of it reflecting the experiences of a young man in his twenties, my experience in academia, the books I’d read. Since then, I’ve found my work has moved outside of myself into the struggles of others.

Part of what makes Here so enjoyable is that the perspective is always unified—the view of these various slivers of time is always the same. We aren’t confused by the psychology of the inhabitants, we aren’t forced to see things from the perspective of people or the animals or the plants. It elevates us to a state of godhood, in a way. We can go from 300 million years ago to deep into the future—and we survive it. Our perspective doesn’t change. In The Familiar, I was interested in almost the opposite experience: There, our self is not preserved. In fact, our self is probably under assault. We aren’t granted our own autonomy. We have to filter through the prejudices of one character, the illiteracy of another, the hyper-literacy of another. In Here, you and I and strangers alike will perceive the boundaries of this structure. But in The Familiar, biased individual points of view shape everything encountered.

One of the joys of literature is we can always push back against established ways of speaking and seeing—and nothing has to be blown up.In The Familiar, I want to look at the vast differences of how we speak to one another, the way we represent the world to ourselves through our various linguistic tricks and errors. People have different vocabularies. They have different cadences. They have perspectives that can be extreme. How do those figures begin to shape a world in an ensemble? As we begin to lose that sense that we have a right to privilege one kind of linguistic approach over another, the whole structure starts to wobble. And it goes beyond the diversity of human beings—what do we do with those creatures that will never have a voice like we demand a voice? Where is that silent partner that we see in trees, or in insects, or in a simple cat? Because animals, and natural systems, do have their own language, in a way—just not one with the verbal accentuations that we have. How might we channel the voice of an animal, or an entire ecosystem?

It’s easy for any mode of writing to calcify into received tradition. When we come across something that works, we repeat it, and ultimately institutionalize it—even though it might come at the expense of other things that might be witnessed or participated in. But one of the joys of literature is that we can always push back against established ways of speaking and seeing—and nothing has to be blown up. No one has to be dispensed with. Huge tracts of land don’t have to be obliterated. By means of these fragile panes of paper, or lighted technological tablets, we start to mingle with other possibilities.

How Network Television Is Facing the Future

The status of network television as the medium’s dominant form has long been in decline. With the rise of cable television, the Internet, and streaming services, the mono-cultural reach of the “big five” networks isn’t what it once was. These days, a show only has to draw a few million viewers to be considered a hit, and the 22-episode model of storytelling is being switched up for a wider variety of schedules aping the more limited “prestige TV” run. But even with all that noted, 2015 is notably seeing the end of two shows that were flagships for the final era of network dominance: CBS’ CSI: Crime Scene Investigation and Fox’s American Idol.

Related Story

The Forgotten Bliss of Feeling Loyal to a TV Network

From 2002 to 2005, CSI was America’s favorite show, a mantle that was then claimed by American Idol from 2005 to 2011. Almost any new show that “launched” out of either hit (i.e. aired after it) became an instant success and an anchor for its network, from House to Without a Trace to Hell’s Kitchen. But both CSI and American Idol have slowly fallen in the ratings while getting more expensive. Neither will go gently (Idol ends after this coming cycle and CSI may get a sendoff movie), but both are long past their glory days.

For every network, the collection of cancelations, renewals, and new series pickups debuted at “Upfronts” (days of press conferences announcing next season’s schedules to reporters and advertisers) marks something of a pivotal moment in an era where a show on basic cable (The Walking Dead) and another on premium cable (Game of Thrones) out-draws almost everything the big five have to offer. Network TV has proven more and more adaptable over the years, offering more shows that embrace serialized storytelling, more single-camera comedies, and more dramas with morally complex leads and themes. But as the universe of TV continues to expand, the vision of network executives seems to be contracting.

Fox’s biggest surprise hit of the 2014-2015 season was Empire, Lee Daniels and Danny Strong’s widescreen soap opera about the hip-hop industry, which drew a weekly Super Bowl-level audience among black TV viewers and saw ratings go up with every subsequent episode—typically a TV impossibility. It will be given an expanded episode order and a more prominent position in the 2015-2016 schedule, but beyond Empire there’s little else the network can carry over with much pride. The former Fox chairman Kevin Reilly reveled in poaching hot talent from other networks, but much of his handiwork is being discarded: The Mindy Project will likely take its small but loyal fanbase to Hulu, Mulaney never quite found its creative voice, and the BBC remake Gracepoint was a ratings dud in an era where you could easily watch the original online.

Aside from Empire, Fox did well with the exceptionally strange Will Forte comedy The Last Man on Earth, a testimony to embracing unusual showrunners with pitches that might seem more suited to cable. The Batman prequel Gotham was never popular with critics, but it had an undeniable slickness that helped it catch on with viewers; hopefully it will up the ante in season two, unlike the previous cult success Sleepy Hollow, which will return for a third year but has creatively lost its way. Fox’s ratings have slowly declined, and the network now languishes in fourth place, which helps explain why its strategy for next season relies on genre dramas (such as the return of The X-Files and a Minority Report sequel) and age-old network stars like John Stamos, Rob Lowe and Fred Savage.

“Old network stars” is practically NBC’s watchword at this point, as it continues to harken back to its glory days of the 80s and 90s. The network actually finished in first place this season, but largely because it aired the Super Bowl (which it won’t get back until 2018). Its schedule consists of Dick Wolf procedural dramas (Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, Chicago Fire, Chicago P.D.) that have all seen better ratings days, and some warmed-over reality-competition shows (The Biggest Loser, The Voice, Celebrity Apprentice) that feel well past their shelf life. Almost everything new NBC threw at its schedule this year flopped, including a slew of single-camera comedies (A to Z, Bad Judge, Marry Me, One Big Happy) that took a broader reach than past cult hits but were met with shrugs from critics and viewers alike.

As the universe of dramatic TV continues to expand, the vision of network executives seems to be contracting.NBC won’t repeat that mistake—its 2015-2016 schedule eschews comedy entirely, except for an hour on Friday nights, and embraces the reboot, from the return of the cult genre hit Heroes to the baffling revival of the 90s Craig T. Nelson sitcom Coach (which, weirdest of all, originally aired on ABC). Its dramas feel as bland as last year: Melissa George is playing a tough workaholic lady doctor in Heartbreaker, replacing Katherine Heigl and the critically reviled political drama State of Affairs. Both shows seem equally shocked at the idea of a female protagonist who can work long hours in a stressful job—an antique viewpoint that ironically reflects NBC’s “throwback” programming vibe.

While NBC remains mired in the past, ABC has sought to embrace a more diverse slate of shows and as such scored a lot of solid hits last year, including Black-ish, Fresh off the Boat, and the John Ridley drama American Crime, all of which scored easy pickups, along with the bizarre (but sporadically charming) medieval musical comedy Galavant. The biggest mistake ABC made was passing on the charming Friday-night sitcom Cristela, largely for business reasons (the network didn’t own the show, so had less to gain from its success), but it remains worlds ahead of its competitors in presenting television that gives meaningful roles to people of color, helped by the network’s relationship with the producer/writer Shonda Rhimes, who scored another big hit this season with How to Get Away with Murder.

For more than a decade now, network television has been dominated by CBS’s ironclad lineups of multi-camera sitcoms (Two and a Half Men, The Big Bang Theory, 2 Broke Girls) and franchised crime dramas (the CSI, NCIS, Criminal Minds, and their ilk). Critical acclaim was rarely given but hardly needed: The much-coveted demographic of 18-to-49-year-old viewers didn’t watch in quite as high ratios, but overall viewer quantity trumped that concern. But the rust may finally be showing: CSI is dead except for the much-derided CSI: Cyber, which debuted this year, and two NCIS spinoffs may not be enough to prop up an entire schedule.

More than any other network, what happens to CBS will probably signify the future of terrestrial television broadcasting, which is taking cautious but deliberate steps into the world of online streaming. It’s already offering a monthly package to watch its shows online without a cable account. Its series orders for 2015-2016 include two reboots of popular films (Rush Hour and Limitless), the return of Supergirl, and a Criminal Minds spinoff starring Gary Sinise, all of which reeks of the kind of desperation that’s unusual for the network. For all the talk of cord-cutters and Internet broadcasting, TV viewers aren’t switching over completely just yet. But one look at what they’re being offered suggests that for all their reach, networks have less and less concept of what they actually want.

The Verizon-AOL Deal: It's About Mobile-Ad Revenue

U.S. telecom giant Verizon is buying AOL, paying $50 a share in a $4.4 billion deal. AOL is the owner of multiple online-media properties, including The Huffington Post and TechCrunch, but the brand is usually associated with the days of dial-up internet. They are so old-school that still having an AOL email address has been called a status symbol of early-adopter-hood, though more commonly it’s interpreted as a sign that someone is a bit behind the times. Last year, it was reported that more than 2 million people are still paying AOL $20 a month for dial-up. Verizon, for its part, is known for offering the most expensive cellular service in America.

Is this deal best described as a behemoth of the new, mobile internet acquiring an artifact of the old dial-up one? Sort of, but what’s also on the table is AOL’s booming advertising business. Just last week, AOL posted 7 percent growth in revenue in the first quarter of 2015, largely due to its third-party ad division. Additionally, AOL reported growth in search and contextual advertising. Trefis, a company that analyzes stock prices, estimates that AOL’s third-party ad division accounts for more than 40 percent of AOL’s current value.

By acquiring AOL’s technology for online advertising, Verizon is no doubt taking aim at the next battlegrounds of online advertising: mobile and video. (The word platform appears multiple times the press release.) In a statement, Verizon said that the combination of the two companies will create a mobile-first platform for ads—a market that’s been estimated to be as big as $600 billion globally. Though $50 a share and $4.4 billion aren’t particularly huge numbers in these heady days, the leaders of both companies seem eager to bring their trailblazing days back—and Armstrong made clear what that path is for AOL: "If we are going to lead, we need to lead in mobile," he wrote in a memo to his employees.

May 10, 2015

Grace and Frankie: A New Kind of Divorce Comedy

“I’m leaving you”: Works of entertainment have lobbed those sad Three Little Words at everyone from Dustin Hoffman to Tina Fey. The life-after-divorce genre is so robust—how many films has Woody Allen made?—that when Martin Sheen’s character, Robert, breaks up with Jane Fonda’s Grace over dinner in the first moments of the new Netflix comedy Grace and Frankie, viewers can already guess what’s to come: scenes of the recently jilted scarfing Ben & Jerry’s and treating her ex’s possessions in a less-than-respectful fashion.

Related Story

The Bruce Jenner Learning Curve

But there’s a twist to this relationship’s end. Robert’s leaving his wife for the man who’s across the table: his law partner Sol (Sam Waterston), sitting next to his own wife, Frankie (Lily Tomlin). The two men have carried on an affair for 20 years, while the two women have done all they could to avoid each other: Grace is a pill-popping former businesswoman who disdains even the sight of carbohydrates; Frankie is a muumuu-clad artist known to meditate on dining tables. Having ex-husbands who’re in love might be the first significant thing they’ve ever had in common.

The conceit helps Grace and Frankie to not feel redundant even as it trades in well-worn breakup tropes, odd-couple hijinks, and writing that’s as broad and nonsensical as the ‘90s sitcoms that co-creators Marta Kauffman (Friends) and Howard J. Morris (Home Improvement) worked on. In fact, the interplay between the relatively novel premise and the all-too-familiar material gives the show some edge. Is being ditched in your golden years because of sexual orientation all that different from being ditched because passions have dimmed, or because your husband was sleeping with another woman? At first, it doesn’t seem different at all. Both Frankie and Grace are devastated and embarrassed like spurned lovers of TV show eternal; at no point in the first three episodes I’ve seen do they express any empathy for their exes’ decades-long identity struggles.

But soon, it sinks in that this is a very specific shock hitting very specific people. “I’m feeling like the last 40 years have been a fraud,” Grace says as she maniacally brushes her hair, to which Robert expresses mystification that she doesn’t take the breakup as a relief: She never loved him in the first place. Frankie and Sol, on the other hand, really did have a deep bond; for them and their kids, the end of the marriage might mean the end of blissful times spent at farmer’s markets, movie nights, and “Jewish Christmas.” Meanwhile, the men excitedly start a new life together. Sol at one point tells Robert he feels guilty for leaving Frankie, saying, “You know what makes it worse? I’m so fucking happy.” But Robert refuses to agonize; he did enough of that when he was playing straight.

The focus on how LGBT liberation affects straight people might strike some as insensitive, but it’s necessary at this point.Grace and Frankie joins a pop-culture boomlet of stories about people coming out as something other than what their loved ones thought they were, late in life. In the most recent season of Girls, Hannah Horvath’s father abruptly exits the closet; Amazon’s Transparent tells of a family’s patriarch who starts living as a woman; in the non-fiction realm, Olympian and reality-TV dad Bruce Jenner has transfixed the nation by revealing that he’s transgender. As queer acceptance rises, the frequency of tales like these in real life and on screen is bound to rise as well; in Grace and Frankie, the uncloseting happens as the direct result of same-sex marriage becoming legal (“I hosted that fundraiser,” Grace moans). Often, the people affected by the coming-out receive as much or more attention than the person who’s actually coming out: Loreen Horvath rages bitterly against her gay husband; the Transparent kids shift the drama from “moppa”—mother and papa, in one—to themselves; the Kardashians’ reactions to Jenner’s announcement get their own TV segments. This focus on how LGBT liberation affects everyone else might strike some as insensitive, but it’s probably necessary when society has led so many relationships to be built on repressed truths.

In Grace and Frankie, the emphasis on the title characters allows the show to be somewhat radical on yet another front: portraying the tough position that single older women can find themselves in. Boomer icons Fonda and Tomlin play into some grandmotherly stereotypes—there are ongoing gags about hearing loss, bad backs, and the difficulties of text messaging—but also fiercely defy toward how circumstances and society treats them. At one point, they flip out at a supermarket employee who ignores them to instead help a younger woman, with Fonda roaring “What kind of animal treats people like this?” The moment is hammy but also poignant, well-earned after the show has methodically chronicled the stages of the women's nightmare: first, they face emotional shock; then, financial and legal indignities; then, boredom, lack of purpose, and invisibility. How will they overcome? The question feels fresh, even if not all the jokes do.

May 9, 2015

Liberia's Ebola Nightmare Is Over

The campaign to eliminate the Ebola virus marked a significant milestone on Saturday, as the World Health Organization declared that Liberia was free of the disease. The announcement came 42 days after the safe burial of the last confirmed Liberian victim of the Ebola, a period equal to twice the virus’ incubation period.

The news was met with jubilation in Liberia, which along with Sierra Leone and Guinea was the country most affected by the virus. But officials tempered their joy with a note of caution.

“Let us celebrate, but stay mindful and vigilant,” said Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, Liberia’s president.

Since the epidemic began last March, 10,564 people across Liberia contracted Ebola, nearly 250 out of every 100,000 people in the country, and 4,716 died. But the human toll still understates the sheer scope of the damage incurred by Liberia, one of Africa’s most impoverished countries.

Ebola exposed glaring deficiencies in Liberia’s public health system, where there are few qualified doctors and most hospitals lack access to electricity and clean water. In the early stages of the crisis, workers at Liberia’s clinics treated patients without adequate precaution, inadvertently spreading the disease. Private hospitals turned many patients away, and at the height of the outbreak Liberians reported seeing Ebola victims die on the street. Altogether, 189 medical workers in Liberia lost their lives to Ebola.

“Now is the time to address factors which contributed to Ebola’s spread.”In a country where the average citizen lives on just $1.25 per day, the Ebola epidemic also had a deleterious effect on Liberia’s economy—estimated at $180 million for 2015 alone. The disease cut the beleaguered country off from the outside world, as airlines like British Airways suspended service to the country, and complicated foreign travel. Liberians traveling to the United States were required to report their temperature to authorities over the first 21 days after their arrival. International fear of the disease grew so acute last December that India canceled a planned summit involving African heads of state due to concern about Ebola’s spread.

Ebola remains active in neighboring Sierra Leone and Guinea, which both reported nine cases of the disease in the last week. The World Health Organization has warned that the Ebola virus can survive in male semen for up to 82 days after infection, and have urged Liberians to refrain from unsafe sex as a precaution. Liberia’s health care system—despite vast improvements in treating Ebola—remains inadequate, and contraction of other diseases has surged. There have been 562 cases of measles in Liberia in 2015, including seven that proved fatal, and over 500 Liberians have contracted whooping cough.

Nevertheless, Liberia’s eradication of Ebola in 14 months was a significant accomplishment in a country just 12 years removed from a devastating civil war that killed 200,000 people. The victory resulted, in part, from the fast reaction of Liberia’s government as well as a sustained international aid effort. But crucial to the eradication effort were the Liberians themselves. Teams of community health workers traveled from door to door in the most dangerous slums of Monrovia, Liberia’s capital, and educated skeptical residents about the dangers of the disease.

"The communities were the heroes in this fight," Hassan Newland, a UNICEF official based in the country last year, told NPR.

But the same issues that have plagued Liberia for generations—poverty, misgovernment, and instability—ensure that the risk of another deadly outbreak has not gone away.

“Now is the time to address factors which contributed to Ebola’s spread, in particular, weak social service delivery, lack of accountability and overly centralized government,” said Karin Landgren, the UN Secretary General’s special envoy to Liberia.

Anna Wintour and Age of Ultron: The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

Self-Publishing

Laura Bennett | Slate Book Review

Selfish is an insane project, a document of mind-blowing vanity and deranged perseverance. It’s also riveting. I can’t recommend it enough.”

The Apple Watch: More Than Just a Bracelet

Jody Rosen | T: The New York Times

“Nearly a week in, I am still poking lamely at the Watch, wearing a pained expression last seen around these parts in 1983, when my grandfather spent a long night of the soul wrestling with a Betamax.”

Searching for Forgiveness at Friendly's

Keith Pandolfi | Eater

“Whenever I walk in the door, I want it to feel the same way it did back when I was a kid, but it doesn't, and I doubt it ever will again.”

Hot Shmurda

Robert Kolker | Vulture

“On the calls, Pollard sounds less like a criminal mastermind than a kid who grew up in a tough part of Brooklyn, where guns and drugs and violence were part of the landscape—as was music.”

In Conversation with Anna Wintour

Amy Larocca | New York Magazine

“'I hope that I set as good an example as I can, but it’s not—I don’t wake up in the morning thinking, I’m going to set a really good example today!'”

One Last Rave

Hua Hsu | The New Yorker

“Electronic dance music is now big business, a mainstream bacchanalia with its own universe of corporate-sponsored festivals and celebrity d.j.s. But the nostalgia for rave culture also seems like an attempt to recover something utopian.”

Alanis Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill was a powerful, DIY feminist statement

Annie Zaleski | A.V. Club

“Because it was so different, naturally many people weren’t sure what to do with Morissette and went for the predictably sexist (and misguided) assessment that she was an angry young woman.”

Engineers of Addiction

Andrew Thompson | The Verge

“'If we knew what that perfect game was, we'd just keep making that game over and over.'”

Age of Ultron's 'Black Widow Problem' Isn't a Problem: It's What the Movie Is About

Sam Adams | Indiewire

“Far from being an incidental character trait, Natasha's inability to bear children is inextricable from Age of Ultron's central theme: evolution.”

Through a Glass, Darkly: The Lady From Shanghai and the Legend of Orson Welles

Brian Phillips | Grantland

“Isn’t there something faintly preposterous, now, about the idea of genius? And especially about the kind of overblown, masculine, 20th-century variety of genius represented by Welles?”

The Surprising History of 'We Shall Overcome'

As marchers took to the streets of Boston in late April to demand justice for Freddie Gray, some of them began to sing: “We shall overcome, we shall overcome, we shall overcome some day ...”

It wasn’t a surprising choice. “We Shall Overcome” is a staple for civil-rights protests—and for that matter, for any kind of social-justice movement. The Library of Congress calls it “the most powerful song of the 20th century.” So it was a surprise to learn that not only is the identity of the person who made it into that anthem known, but he died only on May 2.

His name was Guy Carawan, and he was 87 years old. The story of the song and how Carawan helped make it ubiquitous is full of surprises, and it’s a wonderful demonstration of the folk tradition at work, accreting bits and pieces over the years until it became today’s widely known version. It’s also, appropriately enough for a civil-rights anthem, the story of a song that draws heavily on both African-American and European-American tradition, just like all the best American music. Like so many folk songs, it feels as though it’s existed forever; asking who wrote it seems ridiculous. Hasn’t it always been there?

Actually, although the song is old, its history can be fairly carefully traced. The first few bars seem to derive from a hymn first published in 1792, called “O Sanctissima,” also published as “Sicilian Mariners’ Hymn.” As The New York Times notes in its Carawan obituary, Beethoven wrote a setting of the hymn, and the resemblance is unmistakable for even the least trained ear, though it diverges after the first few lines. The Times says that a version published in the United States in 1794 was already recognizably the melody known as “We Shall Overcome.”

The basic frame of the words seems to have come from “I’ll Overcome Some Day,” a hymn written by the Reverend Charles Albert Tindley, a famed black preacher in Philadelphia, and published in 1901. Tindley’s tune bears little in common with “Sicilian Mariners,” as you can see here. His words are also far more elaborate, and focus more on salvation of the individual by God, rather than the power of collective action. The lyrical similarity comes with a refrain on each verse, in the familiar AABA structure, that presages “We Shall Overcome.”

Related Story

Pete Seeger's All-American Communism

So when the did the song cross over from the sacred to the secular? The first appearance of the modern version of “We Will Overcome” comes from 1945. Workers in the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural & Allied Workers Union in Charleston, South Carolina, went on strike at an American Tobacco Company cigar factory. The workers were largely, though not exclusively, black women. They reportedly ended each day’s picket with a verion of the song. Zilphia Horton, a labor organizer and musician, heard the song there, and Pete Seeger learned it from her. (Seeger is credited with changing the opening line from “We will overcome” to “we shall overcome,” though he wasn’t so sure.) Over the ensuing decade, the song was published and recorded several times.

Carawan, meanwhile, had served in the Navy in the U.S. during World War II and then studied at UCLA, taking a master’s in sociology. Able to play the guitar, banjo, and hammer dulcimer, he moved to New York City and joined the folk revival in Greenwich Village. In 1953, he traveled through the South with Frank Hamilton (who was not yet a member of the Weavers) and Jack Elliott (who was not yet Ramblin’). At Seeger’s suggestion, they stopped at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, an organizing school founded by Zilphia Horton and her husband Myles. Carawan learned “We Shall Overcome” there. In 1959, when Zilphia Horton died, he became Highlander’s music director.

In 1960, at the founding convention of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, in Raleigh, North Carolina, Carawan was asked to lead delegates in a song, and he chose “We Shall Overcome.” Carawan began accompanying himself on guitar, and soon the room was joining him. As he told NPR in 2013, it was an immediate hit:

That song caught on that weekend. And then at a certain point, those young singers, who knew a lot of a cappella styles, they said, “Lay that guitar down, boy. We can do this song better.” And they put that sort of triplet to it and sang it a cappella with all those harmonies. It had a way of rendering it a style that some very powerful young singers got behind and spread.

It’s not hard to see, or hear, why. The song is easy to sing, with a musical arc that seems to enact a rise to victory and then a relieved denouement. Hymns are, of course, made to be easy to sing for large groups of untrained singers. The melody of “We Shall Overcome”—unlike, say, “The Star-Spangled Banner”—spans a tiny range, barely more than an octave, from middle C up to a D. It’s easy to accompany, but instruments aren’t necessary. The lyrics are easy, too—the AABA structure, like a blues song, is straightforward, and it leaves long pauses for a leader to queue a group. Yet the combined effect of these simple elements is, as in all the best folk music, enough to send chills up the spine.

SNCC would go on to play a crucial role in that phase of the civil-rights movement, and soon the song was everywhere. In February 1965, speaking at Temple Israel in Hollywood, Martin Luther King cited it (while also quoting The Atlantic’s first editor, James Russell Lowell):

Yes, we were singing about it just a few minutes ago: "We shall overcome; we shall overcome, deep in my heart I do believe we shall overcome."

And I believe it because somehow the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice. We shall overcome because Carlyle is right: “No lie can live forever.” We shall overcome because William Cullen Bryant is right: “Truth crushed to earth will rise again.” We shall overcome because James Russell Lowell is right: “Truth forever on the scaffold, wrong forever on the throne. Yet, that scaffold sways the future and behind the dim unknown standeth God within the shadow, keeping watch above his own.”

King also mentioned the song in his final sermon in Memphis.

And when Lyndon Johnson called on Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act the following month, in March 1965, he too alluded to the song:

But even if we pass this bill, the battle will not be over. What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches into every section and State of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life.

Their cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice.

And we shall overcome.

After more than 150 years of near obscurity, the song hasn’t left the popular consciousness since. It was performed at the chaotic 1968 Democratic Convention and at countless grammar-school performances. It’s been adopted by Northern Irish Catholics protesting British rule and by fans of the second-tier British soccer team Middlesbrough F.C. It has been performed as a free-jazz dirge by Charlie Haden and as symphonic kitsch by Diana Ross, as soft rock by Roger Waters and, delightfully, as fast reggae by the Maytals.

Like all totems, “We Shall Overcome” has reached the stature that sometimes earns it derision. As marchers in Boston sang it, Kirsten West Savali dismissed it as a symbol of the past, complaining on The Root: “We’re expected to be angels when we’re faced with demons. We’re expected to hold hands, sing, ‘We Shall Overcome,’ and wait patiently for the wheels of justice to turn and for freedom to ring.” But for many people, the song remains an uplifting and unifying presence. When President Obama and other dignitaries went to Selma, Alabama, in March 2015 to mark the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, he, too, cited the song.

As it happens, Carawan's contribution with the song didn’t end with music. In the 1960s, Carawan, Seeger, Hamilton, and Horton’s estate obtained a copyright for the song—mostly, Seeger said, to prevent anyone else from doing it. The proceeds from the song go to a fund black cultural expression in the South, through Highland. As for Carawan, he stayed at Highlander until retiring in the late 1980s. He died at home, where he lived next door to the center. His legacy in introducing “We Shall Overcome” to the American people is as timeless as the song feels.

May 8, 2015

A Federal Civil-Rights Probe in Baltimore

Baltimore asked for a Justice Department investigation into its police practices, and now it is getting one.

Loretta Lynch, just five days into her tenure as attorney general, announced on Friday that she was launching a formal inquiry into whether the Baltimore Police Department has engaged “in a pattern or practice of violations of the Constitution or federal law.” The probe is the latest and most aggressive federal response to the untimely death of Freddie Gray in the back of a police van—an incident that Lynch said had “severed” the already frayed trust between the citizens of Baltimore and the men and women entrusted to protect them.

“If unconstitutional policies or practices are found, we will seek a court-enforceable agreement to address those issues,” Lynch said. “We will also continue to move forward to improve policing in Baltimore even as the pattern or practice investigation is underway. Our goal is to work with the community, public officials and law enforcement alike to create a stronger, better Baltimore.”

“If unconstitutional policies or practices are found, we will seek a court-enforceable agreement to address those issues.”The Justice Department has conducted similar “pattern or practice” civil-rights investigations in dozens of municipalities, but no report was more shocking in recent years than the one resulting from the department’s probe in Ferguson, Missouri. That study, released two months ago by Attorney General Eric Holder, found that beyond the single shooting of Michael Brown, law enforcement officials had used excessive and abusive police tactics, disproportionately against African Americans, as a means of raising revenue for the government.

Lynch took office on Monday and promptly traveled to Baltimore to meet with local officials, law enforcement, and protesters. What distinguishes this civil-rights investigation from many others is that the city’s mayor, Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, asked for it, and Lynch said it had also been welcomed by the city’s police union, the Fraternal Order of Police.

Loretta Lynch (Jim Bourg / Reuters)

Loretta Lynch (Jim Bourg / Reuters) Policing practices have come under scrutiny in cities across the country in the last year, police-related deaths have repeatedly made national headlines, whether in Staten Island, Cleveland, Ferguson, Baltimore, or South Carolina. On Thursday, the district attorney in San Francisco announced an inquiry into racial bias in the city’s police department following reports of racist and homophobic texts among police officers and the discovery that officers had gambled on forced fights between inmates in city jails.

“We’re talking about generations not only of mistrust but generations of communities that feel very separated from their government overall,” Lynch said. Yet she also acknowledged that the Justice Department had neither the intention nor the resources to investigate every local law enforcement agency. “We cannot litigate our way out of this problem,” she said. The broader goal of inquiries like the one in Baltimore is to prompt cities to look into their own departments and make fixes on their own or in collaboration with other jurisdictions.

Lynch’s investigation will likely document that Freddie Gray was not the first young black man to endure a “rough ride” or other abuses at the hands of the Baltimore police force. In seeking the formal inquiry, Rawlings-Blake pointed to statistics indicating that complaints against the police had dropped during her tenure, and perhaps she is hoping that the Justice Department’s findings won’t be as bad as expected. The report itself won’t repair the “fractured relationship” between Baltimore citizens and police, but perhaps it’s a start.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower