Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 430

May 19, 2015

Hot Chip's Electrical-Emotional Power

Dissing the songs dominating the radio at any given moment has become standard practice for musicians on press tours, and Hot Chip member Joe Goddard recently kept the tradition going. “It is a little frustrating because when I listen to quite a lot of modern chart music … it sounds very much as though it relies on the computer,” he told The Independent in an interview promoting his band’s sixth album, Why Make Sense? “Pretty much all the rhythms are quantized, so rhythmically they’re very severe. And people do make amazing music like that, modern popular music that I think is incredible for those things, but I also think a lot of the time it squeezes the humanity out of music, which makes it harder to fall in love with those songs.”

It’s an interesting complaint, coming from him. When people think of London’s Hot Chip, they might think of computers, or at least sounds that recall computers. The music’s largely synth-driven, references electronica history, and is often laden with samples and vocal manipulation. The band has played up the mechanistic aspect of its shtick in promotional photos that have the members dressed a bit like lab techs.

But Goddard was talking in particular about rhythms that result when percussion’s not recorded with drum sets but rather with software that allows beats to be laid precisely on a grid. The imperceptibly off-kilter elements that come when a person and not a machine is keeping time—or playing a melody, or singing—can indeed add a feeling of novelty and surprise to music. So even though the synth pads and keyboards that Hot Chip take the stage with create artificial sounds, in Goddard’s words, the effect should be more “human.”

“Human” is a pretty good description for everything Hot Chip does, in fact. Three years ago, after helping to define the sound of dance rock in the aughts, the band made its masterpiece—or, depending on how much you like their earlier work, a masterpiece—with its fifth album, In Our Heads. Inspired by the epic sweep of both house music and gospel, the songs rolled out with steady beats and lush keyboard textures intermixed with horns, children’s choirs, and birdsong. The band has its detractors, and they’re mostly people who can’t get past frontman Alexis Taylor’s voice: comically gentle, almost whimpering at times, a nerd’s take on soul. But he writes with both an earnestness and precision that suits his voice and dispels notions that he’s aping better singers. For In Our Heads, the overriding theme was love as a kind of joyful negotiation, marked by openheartedness but not naivety. “These chains you bound around my heart complete me,” he sang. “I would not be free.”

Related Story

Sufjan Stevens, Sovereign of Sorrow

After the life-affirming vibe and flat-out brilliance of that album, super-fans might see Why Make Sense? as a letdown. But it’s still pretty wonderful, an example of a band doing something that’s entirely its own. The cover of each copy sold of the new album is a one-of-a-kind piece of artwork, generated by ever-so-slight alterations in color and line placement during the printing process. The idea works pretty well as a metaphor for what the band’s up to: shading fine gradations, attempting to encapsulate complicated parts of life in an appealing, striking package.

The emotional palette here has become a little bit darker than previous Hot Chip releases; listening to it, you wonder if someone involved has gone through a breakup, or is at least missing an ex. “Started Right” contrasts head-over-heels infatuation against the difficulties of lifelong romance, with a cheeky stop/start arrangement—complete with fake bass sounds that recall a toy keyboard—accompanying lyrics about the illogic of love: “You make my heart feel like it’s my brain.” Similarly, “Easy to Get” opens with thin funk riffing as Taylor tells of a late-night seduction; by the end, the affair seems to have ended but he’s telling the subject of the song to “wipe away your regret” as the band joins in for worship-service singing. Often, this kind of wistful, bittersweet feeling is communicated with single sounds tuned to lump-in-throat frequency: a high thread of guitar distortion piercing through the sad mantra-singing of album centerpiece “Dark Night,” thrumming organ chords underlying “Need You Now,” huge drum echoes on the psychedelic title track that closes the record.

The press notes for Why Make Sense? say that 15 years into Hot Chip’s career, the members were wondering what their place was, whether they had anything new to say, and what set them apart from other bands. They took a stab at an explicit answer on the album-opener and first single “Huarache Lights.” Early on, it features a sample of the 1977 Philadelphia disco song, with a female vocalist yelling that she’s “got something for your mind, your body, and your soul.” By the end of the song, those same words are being quoted by Taylor or another band member using a talk box or vocoder, and what had started as a stripped-down dance beat has been gilded with layers of shuddering synths, robo-vocals, and tender sighing. It’s indeed a mind/body/soul experience, just like all the great music should be.

The Problem With Hillary's 'Old Friends'

First, it was Hillary’s private server. Now, it’s her private network.

On Monday, The New York Times reported on Libya-themed memos from longtime Clinton friend Sidney Blumenthal, which were sent to Hillary Clinton during her time at the State Department. The two dozen or so missives are said to “make up about a third of the almost 900 pages of emails related to Libya that Mrs. Clinton said she kept on the personal email account she used exclusively as secretary of state.”

In the memos, Blumenthal dishes warnings, business gossip, and intelligence assessments relating to Libya. Clinton forwarded some of them along to staff as credible or noteworthy, but her state-department staff often dismissed or derided them for their poor sourcing.

The substance of Blumenthal’s memos, though, isn’t as noteworthy as the fact that Blumenthal was working with people trying to do business within Libya when he sent them, and not laboring as a bona fide public official at Foggy Bottom.

“Much of the Libya intelligence that Mr. Blumenthal passed on to Mrs. Clinton appears to have come from a group of business associates he was advising as they sought to win contracts from the Libyan transitional government,” a later Times report noted. “The venture, which was ultimately unsuccessful, involved other Clinton friends, a private military contractor and one former C.I.A. spy seeking to get in on the ground floor of the new Libyan economy.”

The memos covered everything from warnings about possible terrorist attacks and the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood within Libya to the potential training of Libyan rebels and the hiring of new economic advisers by the Libyan premier. As the National Journal reports, the House Benghazi Committee is already seeking Blumenthal’s testimony.

So what to make of all of this? Blumenthal’s associates don’t seem to have profited from his efforts. Clinton herself has long touted her ability to leverage longtime friends and informal relationships as a key asset. Here, she seems to have used her network to supplement the often-limited views she receives through formal channels.

That, at any event, is the benign view. To her critics, it is just the latest episode in a long pattern of similar behavior, blurring the lines between public service and private profit. Back in 2013, Huma Abedin’s status as a special government employee in the Clinton state department drew attention and scrutiny. Abedin served as a senior adviser at the same time she was paid by the Clinton Foundation, by a consulting firm run by a Clinton retainer, and as a personal assistant to Hillary Clinton.

“This raises important questions about whether her dual role was adequately disclosed to government officials who may have provided her information without realizing that she was being paid by private investors to gather information,” Iowa Senator Chuck Grassley wrote at the time.

Speaking of the Hawkeye State, on Tuesday, a court filing revealed the State Department’s plan not to make all 55,000 pages of Clinton emails from her tenure public until January of next year, just two weeks before the Iowa caucus. The federal judge overseeing the case found that unacceptable, and has ordered the department to submit a schedule for releasing them in batches, as soon as possible. That raises the prospect of further revelations at regular intervals through the summer and fall, keeping the story in the spotlight, at a time when Clinton would rather be focusing on her campaign.

L’affaire Blumenthal also coincides with another transparency-related mini-drama over Clinton’s ostensible unwillingness to field questions from the press. To dispel that criticism, Clinton spontaneously took questions from the press in Iowa on Tuesday afternoon. In response to a question about Blumenthal, Clinton characterized his memos as “unsolicited emails which I passed on in some instances.” She took the tack that her ability to include outside perspectives was an important part of avoiding “the bubble.”

“I’m gonna keep talking to my old friends no matter who they are,” she said. With some emphasis, she also declared, “I have many, many old friends.”

Writing Is the Process of Abandoning the Familiar

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Karl Ove Knausgaard, Jonathan Franzen, Amy Tan, Khaled Hosseini, and more.

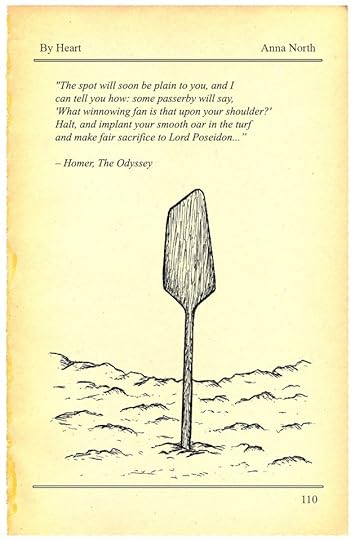

Doug McLean

Doug McLean When I spoke to Anna North, the author of The Life and Death of Sophie Stark, she pointed out that the Odyssey doesn’t really end with its hero’s dramatic, suitor-slaying return. In Book 11, while in the underworld, the dead seer Tiresias orders Odysseus to take one last trip before settling down. If he wants to appease the gods, Odysseus must take his oar and journey as far inland as he can. When people start to gawk, with no recognition, at the strange tool on his back, he’s travelled far enough.

Related Story

Writing Should Be a Continued Exploration

In our conversation for this series, we discussed what North called “the oar moment”: the sudden, profound realization that you’ve gone too far from home. She explained, too, how writing a novel is a bit like taking advice from Tiresias—undertaking a long journey with no clear destination, for reasons you don’t fully understand.

The Life and Death of Sophie Stark takes the form of a fictional oral history, one that explores the way cultural myths are made. The title character, a pioneering film director, never speaks to us directly: We learn about her only through a chorus of competing voices, plus a handful of journalistic reviews. We’re asked to consider a flawed cultural hero whose greatness stems from the fact that she can’t separate people from actors, life from art—and whose reputation rests on the biased narratives of people she inspired, manipulated and hurt.

Anna North is a staff editor at The New York Times. Her first novel was America Pacifica, and her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in The Atlantic, Salon, and The San Francisco Chronicle. She lives in Brooklyn and spoke to me by phone.

Anna North: My grandfather first recommended the Odyssey to me. When he died a few years ago, I went looking for my original copy because I wanted to read from it at the funeral. I found it in my parents’ house, with the original receipt still inside. So I could date exactly when I first got the book: I was eleven years old.

I have strong memories of reading it for the first time. The Odyssey’s a great book for kids. A lot happens. There’s strangeness, magic, excitement. Of course, the names are very weird to a modern person, and I remember getting tripped up over that. But still, I loved it.

The Odyssey’s a great book for kids. A lot happens. There’s strangeness, magic, excitement.It’s an obsession that’s stayed with me into adult life. I’ve always been interested in Greek and Latin literature. I’m excited by the ways those traditions show how old our concerns are. If you read Livy, for instance, you find that almost everything that’s said in American politics had probably said by the Romans, too: everything from concerns about men not being manly enough anymore to debates about the kinds of things the founding fathers cared about. With the Odyssey, it’s possible to see how many of the stories we still tell exist in ancient texts—they’re archetypal. There are things that human beings like to talk about, and always have, and a quest is one of them.

For me, the Odyssey is more appealing than the Iliad and other war narratives. Compared to the Iliad, which may be more widely read, I think of the Odyssey as a book that’s much more feminist. There are almost no women in the Iliad at all, because it’s about a war in which basically no women were allowed to fight. The Odyssey, by contrast, has female characters, and they’re much more interesting. They’re ancient Greek, so they’re not generally in positions of power, and yet some of them are very powerful. They are witches. They can turn you into a pig—things like that. There’s lots of interesting thinking, too, on the ways in which Odysseus himself might be feminine or embody feminine qualities. As a character, his whole thing is less about his prowess and battle and more about his wits. The first line talks about how he’s a man of twists and turns, which is one of his epithets—and though it’s stereotypical to say that a woman couldn’t be good at war, and would only be good at twists and turns, it does feel like he has a gender-bending aspect as a character.

Obviously, the Odyssey is a hero-quest story, and that’s one reason I became so fixated on it. I’m really interested in how someone becomes a hero or an icon. In what ways do you have to give up part of your humanity, your human life, when you’re a hero? Odysseus obviously gives up a huge chunk of his life—time with his family, his ability to do normal things. But, by contrast, what does he gain? What are the ways that you become larger than life when you’re a hero? In what ways can you become superhuman?

For a long time, I’ve been obsessed with this particular part of the Odyssey where Tiresias, the seer, explains to Odysseus what he has to do before he can really go home for good. The whole drama of the book has been Odysseus’ getting home to Penelope and all her suitors. You’d think he’d be done after he returns, kills all those men, and reclaims his family. Instead, Tiresias tells him that he has to do one more thing:

But after you have dealt out death—in open

combat or by stealth—to all the suitors,

go overland on foot, and take an oar,

until one day you come where men have lived

with meat unsalted, never known the sea

nor seen seagoing ships, with crimson bows

and oars that fledge light hulls for dipping flight.

The spot will soon be plain to you, and I

can tell you how: some passerby will say,

'What winnowing fan is that upon your shoulder?'

Halt, and implant your smooth oar in the turf

and make fair sacrifice to Lord Poseidon:

a ram, a bull, a great buck boar: turn back,

and carry out pure hekatombs at home

to all wide heaven's lords, the undying gods,

to each in order. Then a seaborne death

soft as this hand of mist will come upon you

when you are wearied out with rich old age,

your country folk in blessed peace around you.

And all this shall be just as I foretell.

Tiresias instructs Odysseus that, before he can go home, he must take his oar and walk inland until someone mistakes it for a winnowing fan—a tool for winnowing grain—and asks him what it is. In other words, as soon as he’s gone to a place where people don’t know what an oar is, then he’s gone far enough. If he plants the oar in the earth, and makes an offering there, then he can go home. But he has to make this symbolic gesture of going so far away that his oar—the thing he’s based his life on—becomes unrecognizable. Only then can he return home safely.

As advice, it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. There are a lot of instructions like this in the Odyssey: strange, inexplicable things you must do to avoid incurring the wrath of gods. But there’s a way of thinking about this particular passage that does make sense to me: If the point of this book is to go on a journey, then to finish it you have to go away as far as possible before you can truly return and be done.

In a funny way, this takes Odysseus down a peg. He’s a known hero to the Greeks, and he’s been the hero of this story. I love the idea that, before he can go home, he has to go to this place where he’s totally humbled. Not only do they not know who he is, they don’t even know what his oar is. He’s meaningless to them—and that’s an interesting thing to force him to do.

I think a lot about home and away, and that’s one reason this passage feels resonant to me. I’ve felt very conflicted about where my home is ever since I left Los Angeles, which is where I’m from. In all the places where I’ve lived, I’ve asked myself: Am I home now? It’s a hard question for me to answer. But I like having this passage, which helps me define what not home is. This is how you know when you’re really not home—when something precious to you becomes unrecognizable to everyone else—and that feels helpful to me.

If the point of this book is to go on a journey, then to finish it you have to go away as far as possible before you can truly return and be done.An example is when I moved to New York after getting my MFA in Iowa City. I’d lived here not that long—maybe a month. And one day I walked into this coffee shop wearing these bright green pants. The guy behind the counter said, “Nice pants! Where did you get those?”

I told him I got them in Iowa City. He was like, “Where’s that?”

And I said, “Um, it’s in eastern Iowa.”

“Oh,” he said, “I thought it was a store.”

That was the oar moment.

But there’s an opposite of that type of moment, too: If you’re far from home, but then you meet someone from your home, or see something you also have at home, and you have this enormous sense of recognition.

Another aspect of this comes up for me related to the fact that Odysseus basically has to do something for no reason. There’s no clear reason why he should to take this long journey Tiresias asks him to go on, and that’s a lot like writing. Writing is this strange impulse, not a very practical impulse, and it doesn’t make sense to everyone. But for some reason—if you have the impulse—you have to do it anyway. You have to go on this long journey and do something that’s really hard, and all of it for no real reason. I don’t entirely mean that. I love reading, and I think books are so important, and both writing and reading give me a lot of pleasure. I think they have real meaning. And yet, it’s not like you’ve built something when you write a novel. You’re not producing anything physical. You’re putting symbols together. Just the way that what Odysseus is asked to do is symbolic—planting his oar in the ground is a symbolic gesture.

On different level, though, Odysseus’s act has actual meaning: Presumably, the gods would be angry if he didn’t do it. There could be real-life consequences if he fails to perform this action. Similarly, if you’re someone who really loves writing, it can be really hard if you don’t listen to that impulse. There could be real-life consequences, at least in terms of you feeling sad.

It might sound cheesy, but I think writing is a kind of a journey. For me, especially if I’m working on a novel, it takes at least a year of fumbling around before I really get anywhere. As you try to imagine yourself into this world, it’s a process of writing stuff, throwing it out, writing, throwing it out. You’re trying to create this place for yourself inside your head; it’s very hard to get to that place, and it takes a long time to get there. But then, finally, there is the sense that maybe you’ve arrived, though you’ve had to discard a ton of stuff along the way.

Sometimes I wish someone could tell me: Just go to this specific place, and then you’ll be there. I think that’s why I like that passage so much. It’s almost a fantasy to imagine that someone would tell exactly how to get somewhere creatively, and you could just go there, and then you would know. “The spot will become plain to you,” Tiresias says. And yet it’s true with writing that, every now and then, you do get a feeling of total rightness. Suddenly, you can say: Yes, now I’m in the right place with this piece of work. That’s when you can plant your oar in the turf.

That feeling is the only thing I can use as a guide for when things are going well. There’s so much wandering. But every now and then you have this clarity, and—ding!—the sudden sense that things are where they’re supposed to be.

Lindsey Graham Is for Real

When Senator Lindsey Graham first began to flirt with the idea of running for president a few months ago, most people assumed it was a joke. "Lindsey has a sense of humor," his fellow South Carolina Republican, Senator Tim Scott, told Bloomberg. But in the ensuing months, as Graham has set about doing the things presidential aspirants do—traveling to early-state cattle calls, forming an exploratory committee—the suspicion that he is staging an elaborate political prank has faded, replaced by the dawning, incredulous realization that he's serious about this. On Monday, he confirmed it: "I'm running," he said on CBS This Morning, adding that he would make a formal announcement on June 1.

It's easy to list the reasons Graham—who is 59 and in his third Senate term—can't win the GOP nomination. He's reviled by his party's base as a Republican in Name Only for his sometime moderation, including vocal advocacy for immigration reform and climate legislation. Tea Partiers have dubbed him “Flimsy Lindsey” and “Grahamnesty.” To many on the right, he's the epitome of the odious Washington Republican—that breed that haunts talk-show green rooms, mingles with the chattering classes, and fetishizes bipartisan compromise for its own sake. Graham is also a confirmed bachelor who's been known to put his sister's family on his campaign literature. He's not particularly tall or distinguished-looking, and he dresses like a small-town car dealer.

Yet Graham believes he has a point to make. "I'm running because I think the world is falling apart and I've been more right than wrong on foreign policy," he said Monday, adding, "It’s my ability in my own mind to be a good commander-in-chief and to make Washington work." In the same interview, Graham, who is known, along with his buddy John McCain, as one of the Senate's biggest proponents of military intervention, was asked the Republican question du jour: Would he, knowing what we know now, have invaded Iraq? He replied, "Would I have launched a ground invasion? Probably not.” But Saddam Hussein had to go, he added, and "at the end of the day, he is gone. And I’m worried about an attack on our homeland.”

In 2014, conservatives took aim at Graham and missed. Running for reelection in one of the most conservative states in the country, Graham practically dared the Tea Party to try and topple him. During the primary, he proclaimed to anyone who would listen that the race was a referendum on whether the GOP could take a more constructive turn; he was heckled at his party's state convention, yet discussed his liberal views on immigration at nearly every campaign stop. When he won the June primary—avoiding a runoff by taking 56 percent of the vote against six lesser-known candidates—he declared it proof that there was a silent majority of pragmatic Republicans. "I've tapped into something here, and I hope Republicans understand it," he told me at the time. (The message went largely unheard, though, when, the night of Graham’s primary triumph, House Majority Leader Eric Cantor lost his primary in a surprise upset.)

If you look at Graham's record a certain way and squint, he doesn't look quite so unlikely: military veteran, Southern Baptist, working-class roots; vocal critic of the Obama administration's foreign policy and the 2012 Benghazi affair; native of a state that holds the third presidential nominating contest; an experienced legislator in a field short on same. (The other three senators in the race—Marco Rubio, Rand Paul, and Ted Cruz—have each been in Washington for five years or less.) Graham grew up in an apartment above his family’s pool hall and liquor store, and became his younger sister’s legal guardian when his parents both died unexpectedly while he was in college. (When they were young, he decided Darlene should spell her name “Darline” instead, and she spells it that way to this day.) Graham is a deft politician, quick on his feet and funny, and his speeches so far have impressed early-state activist audiences. McCain, who preemptively endorsed his friend back in January, predicted the onetime Air Force lawyer would “shred ’em” in the debates.

The crazy-large Republican field seems to be having a snowball effect, where the more candidates enter (six so far, not counting Graham, with many more signaling their impending entry), the more potential contenders think they may as well give it a try. In a 15-way race, anyone can get lucky, right? And Graham, as he told me back in June, has never been one to back away from a fight. "If it's not me, who's it going to be?" he said. "Why should I hide in a corner because it's hard and somebody may not like it?" Lindsey Graham’s whole career, as he sees it, is testament to the idea that, in politics, you can’t wait around for somebody else to do the job you want done.

May 18, 2015

The Painful Loss of Ramadi

On Monday, a day after the reported fall of the Iraqi city of Ramadi to Islamic State forces, the Pentagon downplayed the significance of the loss.

"To read too much into this single fight is simply a mistake," said a Pentagon spokesman."What this means for our strategy, what this means for today, is simply that we, meaning the coalition and our Iraqi partners, now have to go back and retake Ramadi."

The reality is much more complicated. Even as the Islamic State takeover of the capital city of Iraq’s largest province seemed nearly complete on Sunday, the Pentagon

Obama's Missing Police-Reform Proposal

President Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing released its final, 116-page report on Monday after six months of work. And the boldest proposal made by former Attorney General Eric Holder was nowhere to be found.

The study included dozens of recommendations for local law-enforcement agencies and the Justice Department aimed at repairing the mistrust between police officers and citizens that has deepened to the point of crisis in communities across the county. The mindset guiding police officers should be that of a “guardian,” not a warrior, the panel concluded, and called for better training, more communication and transparency, more community involvement, and better reporting of excessive force incidents. As part of that effort, the president also announced a ban and other limitations on the transfer of certain military-style weapons from the federal government to local law-enforcement agencies.

Missing from those recommendations, however, was any mention of a change in the law that Holder proposed on his way out of office earlier this year: It should be easier, he told reporters, for the federal government to bring charges and win convictions in civil-rights cases, including instances where police officers use excessive force against citizens. The Obama administration evidently decided to make its primary focus the changes it could enact on its own, and those it might recommend to local jurisdictions, instead of asking Congress to pursue a more far-reaching overhaul.

For decades, the Justice Department has functioned as a backstop for local prosecutors who are unable or unwilling to take on such cases, and Holder launched federal investigations into the high-profile deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Eric Garner in Staten Island, Trayvon Martin in Florida, Walter Scott in South Carolina. Local authorities did not secure indictments in Missouri or New York, and George Zimmerman was acquitted in Martin’s death in Florida. The federal inquiry in South Carolina will likely wait until after state prosecutors try their murder case against Officer Michael Slager.

Unlike in state and local jurisdictions, the standard of proof is so high in federal cases that even bringing charges can seem futile, casting doubt on just how effective the federal “backstop” can be. Citing conflicting evidence, the Justice Department declined to seek an indictment against Officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, and officials in February blamed the “high legal standard” for hate crimes as the sole reason they could not prosecute Zimmerman in the 2013 killing of Trayvon Martin. “We do need to change the law. I do think the standard is too high,” Holder told NBC News in February. “There needs to be a change with regard to the standard of proof.”

“We do need to change the law. I do think the standard is too high. There needs to be a change with regard to the standard of proof.”Charging Zimmerman for shooting Martin on account of his race would have come under a different statute than prosecuting the officers who killed Brown, Garner, Scott, or Freddie Gray in Baltimore, but both crimes require the federal government to prove that perpetrators acted “willfully” to violate their victims’ constitutional rights. “It’s not enough to use excessive force. You have to know at the time it was excessive” to be convicted as a police officer, said Margo Schlanger, a law professor at the University of Michigan who tried cases in the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division during the Clinton administration. An officer who claims he fired his gun out of fear—even if that fear was irrational—can therefore escape a federal conviction. “Boiled down into its simplest terms, the cop has to intend to use more force than is reasonably necessary under the circumstances,” said William Yeomans, a law fellow at American University who served as acting assistant attorney general for civil rights.

Take the Ferguson case. The Justice Department did not find evidence capable of proving that Darren Wilson “willfully” used excessive force when he shot Michael Brown beyond a reasonable doubt. Yet federal prosecutors noted in their announcement that while state courts could charge Wilson with a lesser crime, such as manslaughter or negligence, the Justice Department did not have that option. “The argument in Ferguson was much stronger that Officer Wilson acted with reckless disregard than that he intentionally set out to kill Michael Brown thinking that he wanted to violate Michael Brown’s Fourth Amendment right not to be unreasonably seized,” Yeomans explained. “That’s just a crime you’re never going to make out. Whereas you might make out that he was either reckless or criminally negligent in shooting him.”

Despite Holder’s comments to NBC News and Politico’s Mike Allen in late February, he evidently declined to follow through with a major push during his final two months as attorney general. The Justice Department did not respond to inquiries about exactly what kind of changes Holder wanted to see, and civil-rights experts said they had heard nothing about a behind-the-scenes effort to alter the federal standard. The president’s commission on policing didn’t take up the cause either, instead focusing their recommendations mostly on changes that police departments or the Obama administration can make on their own. Changing federal civil-rights law, however, requires an act of Congress, and there’s little evidence that Republican leaders intend to embrace that cause anytime soon—particularly when police unions are almost certain to oppose any changes making it easier to prosecute their members.

“Nobody has ever gotten anywhere trying to move a new substitute standard. The question is whether this is the movement.”The question of how aggressively to press for changes to the civil-rights law—and how to address policing issues without them—now falls to Loretta Lynch, whose first week on the job coincided with protests and unrest in Baltimore following the death of Freddie Gray. Lynch acted quickly to launch an inquiry into whether the Baltimore Police Department had engaged in a “pattern and practice” of abuses of federal law, similar to federal probes that took place in Ferguson, Cleveland, and elsewhere. Schlanger said those investigations could be just as, if not more effective, than federal prosecutions of individual cops, since they are aimed at jumpstarting institutional reforms. Yet as Politico noted earlier this month, one of Lynch’s biggest challenges is that of resources—the relevant section of the Civil Rights Division has about 50 lawyers and cannot possibly take on every police department in the country. “We cannot litigate our way out of the problem,” the new attorney general warned in announcing the Baltimore investigation.

In recent years, the Justice Department also has been more aggressive in stepping in soon after a police-abuse incident or potential civil-rights violation occurs, even if the feds don’t ultimately prosecute. The more assertive approach, experts said, can maintain pressure on local prosecutors, who may otherwise be reluctant to bring charges against police departments with which they work on a regular basis. “It can be helpful to show a community you’ve left no stone unturned,” Schlanger said.

While the push for changing the federal standard of proof has fallen off the radar, attention has focused on increasing the use of police body cameras as a way to hold law enforcement accountable and stop the use of excessive force. Another achievable first step, Yeomans said, is mandating that police departments collect and report to the federal government data on deaths that occur in custody or as a result of an officer’s use of force. That recommendation did make it into the presidential commission’s report, and Obama noted it during an appearance Monday in Camden to highlight the city’s effective use of community policing. The protracted push to enact hate-crimes legislation got a boost, Yeomans noted, when the government first required local jurisdictions to collect and report data on incidences in which race, ethnicity, religion, and other factors played a role.

Could more data be the spark that leads to a change in the legal standard for prosecuting police abuse cases in federal court? Perhaps. “Nobody has ever gotten anywhere trying to move a new substitute standard. The question is whether this is the movement,” Yeomans said. “If it can grow and sustain some momentum, who knows? It’s not going to happen soon.”

The 2016 U.S. Presidential Race: A Cheat Sheet

Late May and early June are shaping up to be peak periods for presidential announcements. On Monday, Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal formed an exploratory committee with plans to make a final decision in June and Lindsey Graham, the senator from South Carolina, said he would start his campaign on June 1. Former New York Governor George Pataki announced last week he would announce his decision on May 28, followed by former Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley two days later.

These possible entries would cap a frenetic month of campaign kick-offs. Neurosurgeon Ben Carson and tech executive Carly Fiorina both announced campaigns on May 4, followed shortly thereafter by former Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee. If he enters, O’Malley would be the second Democratic candidate to join the race this month after Senator Bernie Sanders.

With so many candidates in the mix—some announced, some soon to announce, and some still on the fence—it’s tough to keep track of it all. To help out with that, this cheat sheet on the state of the presidential field will be periodically updated throughout the campaign season. Here's how things look right now.

* * *

The Republicans Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Bobby Jindal

Who is he? Before holding public office, Jindal worked in Louisiana’s public hospital system and led its state university system. He served two terms in the U.S. House before being elected governor of Louisiana in 2007.

Is he running? Probably. Jindal announced on May 18 that he would form an exploratory committee, with a final decision to come after Louisiana’s legislative session ends on June 11.

Who wants him to run? Conservative Christians, who have long embraced Jindal, who was raised Hindu but converted to Roman Catholicism in high school; Louisiana’s oil and gas industry; GOP voters who want a more diverse party.

Can he win the nomination? Maybe. He's a nationally known figure within the GOP, and the 43-year-old governor provides a very different face for a party that tilts old, and white. But his first foray into national politics could give some voters and donors pause. His nationally televised rebuttal the 2009 State of the Union address received near-universal criticism, including among many Republicans.

What else do we know? Wrote an article in 1994 titled “Physical Dimensions of Spiritual Warfare” in which he described a friend’s apparent exorcism.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Lindsey Graham

Who is he? First elected to the U.S. House in 1995, Graham won Strom Thurmond’s Senate seat after the long-time legislator retired in 2002.

Is he running? Sure, why not?

Who wants him to run? John McCain, naturally. Senator Kelly Ayotte, possibly. Joe Lieberman, maybe?

Can he win the nomination? Not really. The South Carolina senator seems to be running in large part to make sure there’s a credible, hawkish voice in the primary. It seems like Graham started his campaign almost as a lark but has started to get into and enjoy the ride, plus he’s shown he’s a great performer on the stump. He’s still a longshot to actually win the nomination, but he could complicate Jeb Bush’s life by performing well in his home state of South Carolina—though he wasn’t even included in a recent straw poll in the Palmetto State.

When will he announce? June 1.

What else do we know? It’s still amazing that the man has never sent an email.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Mike Huckabee

Who is he? Huckabee worked as an ordained preacher before turning to politics, eventually serving as Governor of Arkansas from 1996 to 2007.

Is he running? Yes. He kicks off the campaign May 5.

Who wants him to run? Social conservatives; evangelical Christians.

Can he win the nomination? Huckabee's struggle will be to prove that he's still relevant. Since he last ran in 2008, a new breed of social conservatives has come in, and he'll have to compete with candidates like Ted Cruz. His brand of moral crusading feels a bit out of date in an era of widespread gay marriage—not least when curiously chose to attack Beyoncé. He faces fire from strict anti-tax conservative groups for tax hikes while he was governor. And fundraising has always been his weak suit. But Huckabee's combination of affable demeanor and strong conservatism resonates with voters.

What else do we know? Here is Huckabee's launch teaser video, with plenty of contrast with the Clintons.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Ben Carson

Who is he? As the director of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins, Carson became one of the most prominent doctors in America. His speech condemning President Obama during the 2013 National Prayer Breakfast catapulted him to conservative stardom.

Is he running? Yes, after a May 4 announcement.

Who wants him to run? Grassroots conservatives, who have boosted him up near the top of polls, even as Republican insiders cringe. Carson has an incredibly appealing personal story—a voyage from poverty to pathbreaking neurosurgery—and none of the taint of politics.

Can he win the nomination? Almost certainly not. Carson's politics are conservative on some issues, but so eclectic as to be nearly incoherent overall. He's never run a political campaign, and has a tendency to do things like compare ISIS to the Founding Fathers. It's hard to imagine his candidacy surviving more serious scrutiny, but then again he's reportedly building an impressive political organization, especially in Iowa.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Carly Fiorina

Who is she? Fiorina became one of America’s most prominent businesswomen during her tenure as CEO of Hewlett-Packard. After her ouster following a merger with Compaq, she challenged incumbent Senator Barbara Boxer her California seat in 2010 and lost.

Is she running? Yes, as of a May 4 announcement.

Who wants her to run? It isn’t clear what Fiorina’s constituency is. She’s a former CEO of Hewlett-Packard, but there are other business-friendly candidates in the race, all of whom have more electoral experience.

Can she win the nomination? Almost certainly not. Fiorina’s only previously political experience was a failed Senate campaign against Barbara Boxer in 2010. She has mostly been serving the role of harasser in the race so far, stirring up the news with slams on environmentalists for causing droughts (your guess is as good as mine), Obama for backing net neutrality, and Apple’s Tim Cook for speaking out on Indiana’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Mainly, though, she has strongly criticized Hillary Clinton, and some Republican strategists like the optics of having a woman to criticize Clinton so as to sidestep charges of sexism.

What else do we know? Fiorina's 2010 Senate race produced two of the most entertaining and wacky political ads ever, "Demon Sheep" and the nearly eight-minute epic commonly known as "The Boxer Blimp."

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Marco Rubio

Who is he? After nine years as state Speaker of the House, Floridians elected Rubio to his first term in the U.S. Senate in 2010.

Is he running? Yes—he announced on April 13.

Who wants him to run? Rubio enjoys establishment support, and has sought to position himself as the candidate of an interventionist foreign policy.

Could he win the nomination? Charles Krauthammer pegs him as the Republican frontrunner. His best hope seems to be to emerge as a consensus candidate who can appeal to social conservatives and hawks, and he's even sounded some libertarian notes of late. He's well-liked by Republicans, and has surged forward since announcing, but he needs to move up from second choice to first choice for more of them.

Michael Vadon

Michael Vadon George Pataki

Who is he? After rising through the state legislature, Pataki ousted incumbent Mario Cuomo in 1994 to serve three terms as Governor of New York.

Is he running? Maybe.

Who wants him to run? It's not clear. Establishment Northeastern Republicans once held significant sway over the party, but those days have long since passed.

Can he win the nomination? As my colleague Russell Berman previously noted, Pataki is one of the longest of the long shot GOP candidates. He previously touted his leadership as governor of New York on 9/11, but so did former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani. He was also a successful conservative governor in a deep-blue Northeastern state, but so was former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney.

When will he announce? May 28.

What else do we know? Unusually for a GOP candidate, Pataki is fairly socially liberal: He passed a gay-rights bill as governor, supports same-sex marriage, and is pro-choice.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Rand Paul

Who is he? Paul practiced opthalmology in Kentucky before his election to the U.S. Senate in 2010. His father, Representative Ron Paul, briefly served alongside him in Congress.

Is he running? Yes, as of April 7.

Who wants him to run? Ron Paul fans; Tea Partiers; libertarians; civil libertarians; non-interventionist Republicans.

Can he win the nomination? That depends who you ask. The Kentucky senator would be an unorthodox pick, with many positions outside his party's mainstream. He's relatively permissive on drugs and same-sex marriage, passionate about civil liberties, and adamantly for restraint on foreign policy. But Paul has worked hard to firm up establishment ties since reaching the Senate, and he has recently worked to paper over his differences with GOP’s hawkish wing, calling for a declaration of war against ISIS and generally saber-rattling. He is positioning himself as a candidate with crossover appeal in the general election, and his announcement email mocked the idea that only an establishment candidate can win a general election.

What else do we know? One of Paul's greatest strengths is the base bequeathed to him by his father, three-time presidential candidate and former Representative Ron Paul. But as The Washington Post has reported, his father is also Senator Paul's biggest headache, due to his penchant to speaking his mind on issues like secession. Ron Paul's institute also publishes fringe views like the idea that the Charlie Hebdo attacks were a false-flag operation.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Ted Cruz

Who is he? Cruz, a lawyer, served as deputy assistant attorney general in the George W. Bush administration before being appointed Texas Solicitor General in 2003. In 2010, he won his first term in the U.S. Senate.

Is he running? Yes. He launched his campaign March 23 at Liberty University in Virginia.

Who wants him to run? Hardcore conservatives; Tea Partiers who worry that Rand Paul is too dovish on foreign policy; social conservatives.

Can he win the nomination? Though his announcement gave Cruz both a monetary and visibility boost, he still starts with some serious weaknesses. Much of Cruz's appeal to his supporters—his outspoken stances and his willingness to thumb his nose at his own party—also imperil him in a primary or general election, and he's sometimes been is own worst enemy when it comes to strategy. But Cruz is familiar with running and winning as an underdog.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Jeb Bush

Who is he? Bush served two terms as Governor of Florida from 1999 to 2007. His father and brother were the 41st and 43rd presidents of the United States, respectively.

Is he running? Almost certainly.

Who wants him to run? Establishment Republicans; George W. Bush; major Wall Street donors.

Can he win the nomination? No one really knows. Since jumping into the race, he has continued to poll well and raise lots of money. He seems like a lock to rack up all-important endorsements from top Republicans. But predictions that he would quickly come to dominate the field have not come to pass, and while many analysts predicted that his moderate record would cause trouble in Iowa and with grassroots activists, that problem seems to be deeper than expected. His poll numbers are probably helped by his name, which is a double-edged sword.

When will he announce? No sooner than June, per The Washington Post.

What else do we know? Since Bush's surprise announcement, he has tended to stay fairly quiet, delivering some big speeches and hitting fundraisers, but not making a great number of trips to Iowa or New Hampshire.

David Shankbone

David Shankbone Chris Christie

Who is he? Christie cut his political teeth as a state legislator before his appointment as U.S. Attorney for New Jersey from 2002 to 2008. He is currently in his second term as Governor of New Jersey.

Is he running? It seems ever harder to imagine. With indictments of two of his former top aides in early May, and a guilty plea by a high-school friend and political appointee, the George Washington Bridge scandal has crept ever closer to him. The New York Times says he's trying to "salvage" his campaign. Christie does have some campaign infrastructure in place in New Hampshire, which is close to his home state, with staffer hires and town-hall meetings there. He has also formed a political-action committee.

Who wants him to run? Moderate and establishment Republicans who don't like Bush or Romney; big businessmen, led by Home Depot founder Ken Langone.

Can he win the nomination? The tide of punditry had turned against Christie even before the "Bridgegate" indictments. It's hard to imagine how he recovers at this point, given the crowded field and the fact that Jeb Bush seems to dominate the moderate end of the Republican Party. Citing his horrific favorability nominations, FiveThirtyEight bluntly puns that "Christie's access lanes to the GOP nomination are closed." A recent Monmouth University poll showed him trailing even Donald Trump (see below) for the nomination. Plus, he'd probably have to resign as governor to run, because of SEC rules that cover donations from companies that do business with the state. With such high stakes, he might not want to run at all if he doesn't see a clear path to win.

When will he announce? According to Time, Christie has told donors that running is harder than he had realized, and that he may have to push back an announcement to as late as June.

What else do we know? If you can tell what is going on in this GIF, please let me know. Is he tossing the jacket away? Or catching it? And what does it mean?

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Scott Walker

Who is he? Elected Governor of Wisconsin in 2010, Walker became nationally known for his staunch conservative policies. He became the first governor in U.S. history to survive a recall election in 2013 and won a second term the following year.

Is he running? Almost certainly.

Who wants him to run? Walker's record as governor of Wisconsin excites many Republicans. He's got a solid résumé as a small-government conservative. His social-conservative credentials are also strong, but without the culture-warrior baggage that sometimes brings. And Walker has won three difficult elections in a blue-ish state.

Can he win the nomination? No one knows. For all his strengths, Walker has never run a national campaign and isn't exactly Mr. Personality. But Jeb Bush's emergence seems to have helped Walker, propelling him to the front of the pack as a more conservative alternative to Bush. He's now solidly in the top tier of candidates.

When will he announce? Spring.

What else do we know? Barack Obama took a shot on April 7 at Walker for his criticism of a nuclear-deal framework with Iran. That's a sign that he's becoming a power player, and sniping from the White House is only likely to elevate Walker's standing with Republicans. Good news, bad news: Walker has a geographic advantage in his proximity to Iowa, but a potential biological disadvantage from his allergy to dogs.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Rick Santorum

Who is he? Santorum represented Pennsylvania in the U.S. Senate from 1995 until his defeat in the 2006 midterms. He subsequently sought the GOP presidential nomination in 2012.

Is he running? Yes.

Who wants him to run? Social conservatives. The former Pennsylvania senator didn't have an obvious constituency in 2012, yet he still went a long way, and Foster Friess, who bankrolled much of Santorum's campaign then, is ready for another round.

Can he win the nomination? It's tough to imagine. Santorum himself said his chances would hinge on avoiding saying "crazy stuff that doesn't have anything to do with anything." National Review Editor Rich Lowry praised his speech at a January summit in Iowa hosted by Steve King, the representative and conservative powerbroker.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Rick Perry

Who is he? As Lieutenant Governor of Texas, Perry automatically became governor after his predecessor George W. Bush was elected president in 2000. He became the longest-serving governor in Texas history by the time he left office in 2014.

Is he running? Very likely.

Who wants him to run? Small-government conservatives; Texans; immigration hardliners; foreign-policy hawks. Noah Rothman makes a case here. (Perry's top backer four years ago, non-relative Bob Perry, died in 2013.)

Can he win the nomination? Maybe, but who knows? Perry and his backers insist 2016 Perry will be the straight shooter who oversaw the so-called Texas miracle, not the meandering, spacey Perry of 2012. We'll see.

When will he announce? May or June.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Sarah Palin

Who is she? A first-term governor of Alaska largely unknown outside her state, Palin became a national name after John McCain chose her as his running mate in 2008.

Is she running? A bizarre speech in January made a compelling case both ways.

Who wants her to run? Palin still has diehard grassroots fans, but there are fewer than ever.

Can she win the nomination? No.

When will she announce? It doesn't matter.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Mitt Romney

Who is he? Romney served one term as governor of Massachusetts from 2003 to 2007. He previously sought the GOP nomination in 2008 and won it in 2012.

Is he running? Nah. He announced in late January that he would step aside.

Who wanted him to run? Former staffers; prominent Mormons; Hillary Clinton's team. Romney polled well, but it's hard to tell what his base would have been. Republican voters weren't exactly ecstatic about him in 2012, and that was before he ran a listless, unsuccessful campaign. Party leaders and past donors were skeptical at best of a third try.

Could he have won the nomination? He proved the answer was yes, but it didn't seem likely to happen again.

Gage Skidmore John Bolton

Gage Skidmore John Bolton Who is he? Bolton received a recess appointment as U.S. ambassador to the UN from President George W. Bush in 2006, where he served for seventeen months.

Is he running? Probably.

Who wants him to run? People who don’t like the United Nations. During his brief stint as U.S. ambassador to the organization, Bolton opposed everything from arms-control treaties to the Millennium Development Goals. He accepted a post at the American Enterprise Institute after leaving diplomatic service.

Can he win the nomination? Quantum physics tells us anything is possible, but this would be pushing it. A likelier outcome could be a plum foreign-policy role in a hawkish GOP presidency. In 2012, Newt Gingrich said he would have nominated Bolton to be his Secretary of State.

When will he announce? Thursday, on Facebook.

What else do we know? Somehow maintains a strict 9 PM bedtime.

Donald Trump

Is he running?

Others Still in the Mix:

John Kasich, Bobby Jindal, Pete King, Harold Stassen

* * *

The Democrats Wikimedia

Wikimedia Bernie Sanders

Who is he? Sanders represented Vermont in the U.S. House from 1991 to 2007, when won a seat in the Senate.

Is he running? Yes.

Who wants him to run? Far-left Democrats; socialists; Brooklyn-accent aficionados.

Can he win the nomination? No, although his campaign seems more about getting his ideas into the mix than about winning. In particular, he's an outspoken opponent of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the free-trade agreement President Obama is pushing. Hillary Clinton once seemed to back the deal, but she's offered far more equivocal statements since declaring her candidacy. But Sanders came out of the gate with strong fundraising numbers and has testily rebuffed reporters who suggest he can't win.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Hillary Clinton

Is she running? Yes.

Who wants her to run? Most of the Democratic Party.

Can she win the nomination? Duh.

What else do we know? Maybe a better question, after so many years with Clinton on the national scene, is what we don't know. Here are 10 central questions to ask about the Hillary Clinton campaign.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Joe Biden

Is he running? He won't rule it out, but he's made no serious steps toward a run. He's addressing a "secretive" group of gay donors on May 2.

Who wants him to run? Joe Biden, maybe.

Can he win the nomination? If Clinton didn't run, it would throw the Democratic field into disarray. But probably not.

When will he announce? It seems ever more likely that he won't.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Jim Webb

Is he running? He has launched an exploratory committee.

Who wants him to run? Dovish Democrats; socially conservative, economically populist Democrats; the Anybody-But-Hillary camp.

Can he win the nomination? Probably not.

Steven Senne / AP

Steven Senne / AP Lincoln Chafee

Is he running? Chafee—who served in the U.S. Senate as a Republican and then as Rhode Island governor as an independent and then a Democrat—has launched an exploratory committee.

Who wants him to run? No one knows! Chafee's exploratory committee came out of nowhere, with little anticipation or fanfare or even rumors. He opted not to seek reelection as governor in 2014, in part because his approval rating had reached a dismal 26 percent.

Can he win the nomination? No. Chafee seems to be positioning himself as an economic populist and says Clinton's 2002 vote for the Iraq war should disqualify her (he was the only Republican senator to vote against it). In other words: He's Jim Webb with a less impressive resume, a less compelling bio (he's the son of longtime Senator John Chafee), and less of a political base. He gives himself even odds, though.

When will he announce? He says he wants to gauge support and fundraising and then decide in the next few months.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Martin O'Malley

Is he running? Probably.

Who wants him to run? Not clear. He has some of the leftism of Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren, but without the same grassroots excitement.

Can he win the nomination? Unless Clinton's campaign falls apart, it's hard to see where O'Malley would get an opening. It's hard to judge how these things shake out, but the conventional wisdom since protests over the death of Freddie Gray is that protests in Baltimore undermine the case for his candidacy and make it harder for him to run.

When will he announce? May 30.

What else do we know? O'Malley says if he runs, the announcement will be in Baltimore. And have you heard that he plays in a Celtic rock band? You have? Oh.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Elizabeth Warren

Is she running? No. Seriously, no.

Who wants her to run? Progressive Democrats; economic populists, disaffected Obamans, disaffected Bushites.

Can she win the nomination? No, because she's not running.

May 17, 2015

Asia's Looming Refugee Disaster

In recent weeks, the international media has devoted significant attention to the immigration crisis in the Mediterranean Sea, where hundreds of African and Middle Eastern refugees have lost their lives attempting to flee to Europe. But an even more serious crisis is now occurring many thousands of miles to the east, in the crystalline waters near Southeast Asia. In the last week, more than 5,000 refugees from the Rohingya ethnicity have fled Burma on overcrowded, unseaworthy vessels, desperately attempting to escape a humanitarian crisis at home. Some of the ships—whose occupants lack sufficient food, water, and methods of communications—have successfully docked in countries like Thailand and Malaysia. But an estimated 2,500 Rohingya remain marooned in international waters, and more are likely to come. According to Reuters, more than 25,000 Rohingya boarded refugee boats in the first three months of 2015.

Burma’s Apartheid State

The Rohingya are a dark-skinned, Muslim ethnicity native to the area near Burma’s border with Myanmar. A religious minority in a country that’s 90 percent Buddhist, many of the 1.1 million Rohingya live in a state of apartheid, clustered in concentration camps that are largely disconnected from the outside world. In a 10-minute documentary produced by the New York Times last year, columnist Nicholas Kristof found that the Rohingya almost completely lack access to medical care or international aid.

“We have treated them humanely, but they cannot be flooding our shores like this.”This isolation has caused a humanitarian catastrophe, captured in harrowing detail in the documentary. Kristof profiles an older man now permanently disfigured as no doctor could treat his broken right arm. A pregnant young woman, in labor for more than 20 hours, is turned away from an overwhelmed clinic. She miraculously survives—but her baby does not.

The Rohingya are subject to violent attack from Buddhist Burmese, who speak of them with intense hatred. In the documentary, Kristof asks a group of Buddhist children what they’d do if they encountered a Rohingya of their age.“I’d kill him,” said a boy of no more than ten. Last January, a Buddhist mob did just that, hacking 22 Rohingya—including five children—to death.

The Burmese government denies basic citizenship to the Rohingya, who are unable to vote and whose movements are strictly limited. Even Ang San Suu Kyi, Burma’s revered Nobel Peace laureate who is now a member of parliament, has refused to take up the Rohingya cause, fearful of jeopardizing the chances of her National League for Democracy party in elections scheduled for this October. Suu Kyi refuses to even use the word “Rohingya” in public.

An Unwanted People

The Rohingya who flee Burma face severe limits on where they can go. Many attempt to migrate to Malaysia, a Muslim country whose developed economy faces a shortage of unskilled workers. Malaysia claims it has accepted over 120,000 Rohingya, but that it cannot take them indefinitely.

“What do you expect us to do?” Malaysian Deputy Home Minister Wan Junaidi Jafaar told The Guardian. “We have been very nice to the people who broke into our border. We have treated them humanely, but they cannot be flooding our shores like this.”

Thailand, which faces a slow-burning Muslim insurgency in its southern provinces, also doesn’t want more Rohingya. Neither does Indonesia. And unlike in Europe, where the Mare Nostrum organization performs search and rescue missions in the Mediterranean, no parallel institution exists in Southeast Asia. Those Rohingya who are rejected from foreign ports are destined, then, to float indefinitely.

Little Help from the U.S.

On Saturday, the Malaysian government claimed that the ultimate responsibility for the Rohingya belongs to Burma, a country now opening up after decades of tyranny and isolation. But American advocacy for the Rohingya has also fallen short. President Obama has touted this Burmese perestroika as one of his administration’s signature foreign policy achievements, and became the first sitting American president to visit Burma in 2012. In the years since, the U.S. has made little effort to apply real diplomatic pressure on Burma. According to Kristof, Obama’s criticisms of the country’s human rights record have been “pathetically timid.” In a routine letter sent to Congress last week, Obama said he would maintain sanctions on Burma. But earlier this month, the administration welcomed a Burmese official known for his extremist anti-Rohingya views to Washington.

“In a statement released afterwards, the White House’s press office even avoided using the word ‘Rohingya,’ apparently so as not to offend Myanmar,” Kristof wrote.

Meanwhile the Rohingya themselves—persecuted at home and abandoned at sea—struggle just to survive.

The Great War Novelist America Forgot

On May 27, the American novelist Herman Wouk will attain the prodigious age of 100. Over his long career, Wouk has achieved all the wealth and fame a writer could desire, or even imagine. His first great success, The Caine Mutiny (1951), occupied bestseller lists for two consecutive years, sold millions of copies, and inspired a film adaptation that became the second highest-grossing movie of 1954. Wouk’s grand pair of novels, The Winds of War and War and Remembrance, likewise found a global audience, both in print, and then as two television miniseries in the 1980s.

Related Story

Where's the Great Novel About the War on Terror?

Wouk won a Pulitzer for The Caine Mutiny. From then on, however, critical accolades eluded him. Reviews of the two “War” novels proved mostly dismissive—sometimes even savage. Critics assigned the proudly Jewish Wouk to the category that included Leon Uris and Chaim Potok rather than Saul Bellow and Philip Roth.

Negative critical judgment matters. After the first fizz of publicity, it is critics who in almost all cases determine what will continue to be read. The novelist known as Stendhal described books as tickets in a lottery, of which the prize is to be read in a hundred years. If enduring readership is the ultimate prize for a writer, then Wouk is at present failing. Readers under 40 know Wouk, if they know him at all, as a name on the spine of a paperback shoved into a cottage bookshelf at the end of someone else’s summer vacation—or perhaps as the supplier of the raw material for Humphrey Bogart’s epic performance as Captain Queeg of the USS Caine. What they don’t know is that Herman Wouk has a fair claim to stand among the greatest American war novelists of them all.

The plot of The Caine Mutiny is easily summarized. A spoiled, self-indulgent young man named Willie Keith joins the Navy, mostly because it promises less walking than the Army. (If you want to see Keith as a symbol for America itself, Wouk won’t object.) Keith finds himself aboard an antique minesweeper, the Caine. The ship performs a succession of minor missions under oddball commanders. One of those commanders, Queeg, ultimately puts the whole ship at risk. The officers of the Caine mutiny against Queeg’s leadership, and are subsequently court-martialed. They are acquitted but never forgiven by the Navy higher command. The bravest and most capable of the officers forfeits his hopes of promotion. After an unexpected act of heroism, Willie Keith finds himself the last commander of the Caine. When he is finally demobilized, months after the war has ended for everybody else, he emerges chastened, matured, and ready for the responsibilities of the postwar world.

The two “War” novels aren’t as compactly formed as The Caine Mutiny. The “War” novels tell the stories of two families, that of a U.S. naval officer, “Pug” Henry, and that of a Jewish-American scholar, Aaron Jastrow. The Henry and Jastrow families become connected when one of Pug’s sons marries Jastrow’s niece. Wouk deploys the members of the two families—and their friends, lovers, and military units—around the planet in order to tell the story of the war from the late 1930s until the liberation of the Nazi death camps. Pug himself at various points meets President Roosevelt, Benito Mussolini, Adolf Hitler, Winston Churchill, and Josef Stalin, along with much of the U.S. naval and military high command. In title and structure, the two “War” novels invite comparison to Tolstoy’s War and Peace. That’s asking for trouble right there. But if the only books worth writing or reading were those that equal War and Peace, then none of us would need much bookshelf space. What Wouk did in the “War” novels is accomplishment enough.

Herman Wouk has a fair claim to stand among the greatest American war novelists of them all.Pull that paperback from off the cottage shelf, open the pages—and suddenly there you are: walking a Polish country road as a Stuka buzzes overhead … in the wardroom of a warship tasting thin Navy coffee … shivering in the unpressurized cabin of a bomber above Germany … or waiting amid a roomful of desperate visa applicants for the stamp that will mean the difference between life and death. Between these dramatic incidents, Caine and the “War” novels pulse with the everyday details of 1940s America: what it felt like to wait for a letter in the post, the passage of time on a transcontinental railway trip, the crinkle of the carbon paper between two copies of an army report, the uncertainty of knowing who would win the war, and when, and how.

“It is the war itself,” was reportedly Henry Kissinger’s high praise for the “War” novels. Even as we retain memories of the war’s events, the war’s atmosphere—the way people felt and talked and thought—fades from our understanding. In The Imitation Game, the recent movie about the British computer scientist Alan Turing, the moviemakers got every visual detail right: clothes, cars, streetscapes. Then they represented Turing as a single lonely scientist building a machine by hand out of discarded spare parts in a Victorian stable. The industrial vastness and technological sophistication of the British war effort somehow eluded the moviemakers’ memories or failed to engage their interest.

Wouk never lets the reader forget that the Second World War was the biggest collective undertaking in the history of the human race. No movie could ever depict it, because no movie could ever have the budget. Imagine, however, a movie with an infinite budget—because the special effects are all in the reader’s mind—and you have something of the effect of Wouk’s Caine and his War novels. Wouk’s methods are cinematic. He describes battles as a moviemaker would try to film them, cutting back and forth from a wide-angle view of the contending armies or battle fleets to the individual experience of a particular character. His account of the attack on Pearl Harbor , for example, shifts back and forth between an omniscient narration of the Japanese bombing of the U.S. battleships at anchor and the vantage point of Pug’s daughter-in-law, who happens to observe the bombing of the ships from the shoulder of a road on a hill above the U.S. naval base.

Wouk uses the wide angle because he wants us to see the whole war and understand what it was all about. More critically admired novelists of the 20th century—from Erich Marie Remarque to Pat Barker—want us to feel the terror and filth and cruelty of war from the perspective of the individual caught in its violence. Wouk wants us to see war’s cruelty too. But he also wants us to appreciate why the generals or admirals made the decisions they did, why each side won or lost. His war is not a roar of irrational violence without form or purpose. His war is the war of a documentary on the History Channel: violent, yes, but violence with a shape, a goal, and a justification.

One of the most harshly depicted characters in The Caine Mutiny is an aspiring writer at work on a novel sharply critical of the Navy. The aspiring writer makes the mistake of missing the barbed compliment when a character who (obviously) speaks for Wouk congratulates the writer for satirizing the Navy’s “stupid, stodgy Prussians.” The Wouk stand-in then upbraids the writer: While the two of them were enjoying the benefits of peace, it was those “stupid, stodgy Prussians” of the regular Navy and Army who were “standing guard on this fat, dumb, and happy country of ours.” Even as the cultural climate shifted in the Vietnam era (Winds of War was published in 1971; War and Remembrance in 1978) Wouk stood his ground in believing that war can be necessary, and that death in battle is a risk that men can rationally accept.

Wouk doesn’t deny the horror of war, but he doesn’t look closely at it. There’s nothing here like the horrific description of the death of the bombardier Snowden in Heller’s Catch-22: the still-living intestines spilling out of a man’s gashed, bleeding body. Even the most painfully described death in the War novels (that of Pug’s aviator son Warren) is presented as somehow uplifting. Having heroically sunk a Japanese warship at the Battle of Midway, Warren’s plane is struck by Japanese anti-aircraft fire. Wouk describes the heat of burning gasoline roasting a human being alive; the flyer’s anguished awareness of imminent death and the loss of all future hopes. The plane tumbles into the ocean. The pain of the fire is soothed by the inrush of water, and the not altogether likable Warren’s final thoughts are brave and noble.

Wouk’s war is not a roar of irrational violence without form or purpose.This is war literature as influenced by Rupert Brooke rather than Wilfred Owen. Again and again through the War novels, flawed characters—a coward, a cad—are redeemed by the manner of their deaths: one parachuting into France to aid the Resistance; another saving his submarine from enemy air attack by giving the order to submerge before he can re-enter. Yes, as Joseph Heller shows, people get their intestines blown out in war. They can also get their intestines blown out by an armed invader if they refuse to defend against a military aggressor—and it’s that latter horror about which Wouk has the most to say.

The Nazi Holocaust pervades the War novels and lurks in the corners of Caine too. Some of Wouk’s characters stumble into the Holocaust’s maw; others glimpse inside and are transformed forever. Adolf Eichmann makes a large and memorable appearance in War and Remembrance. Let it be noted that the supposedly middlebrow Wouk more shrewdly penetrated the Nazi murderer’s self-serving lies than the echt highbrow Hannah Arendt. Wouk’s Eichmann is no banal bureaucrat, but a fanatical plunderer and murderer—just as the historical documents that have become available since the writing of Wouk’s novels have confirmed.

It’s really a striking thing how unexpressed a place the Jewish Holocaust occupied in the writing of American Jewish novelists in the decades after the war: Heller, Bellow, Malamud, Doctorow. (Mordecai Richler too, to include a Canadian.) With Wouk, the Holocaust is always front of mind. In 2012, at 97, when he was asked by Vanity Fair which living person he most despised, he answered, “The Jewish writer who traduces his Jewishness.” (The runner-up, it would seem, is the U.S. military veteran who traduces the U.S. military.)

Just as the invention of photography forced painters to rethink the purposes of their art form, so writers have had to rethink their medium since the advent of cinema. What’s the novel for when a story can be told so much more immediately by film? The various possible answers to this question supply the literary history of the 20th century. Some writers decided that the purpose of the novel was to explore the artistic potential of language itself. Some writers plunged beneath the surfaces of people and things to explore human psychology and the structure of consciousness. Wouk’s answer was to revert to the foundations of human story, to The Iliad and the troubling mysteries of combat. Wouk was a participant in the most terrible war in human history, and he wanted to record what had happened and why it had to be done. To achieve that end, Wouk fused fiction with history in ways sometimes hugely successful (his character sketch of Franklin Roosevelt—even better as rendered in FDR’s Groton accent in the audiobook superbly performed by Kevin Pariseau), and sometimes not (the interpolation of an imaginary history of the war by a fictitious German general).

The contrivances necessary to move Wouk’s characters from event to event sometimes creak. The characters themselves, however, never feel contrived—not the fictitious characters and (even more difficult) not the historic ones. Their stories and their personalities endure in the memory. Wouk may not be a stylistic innovator or a polisher of the perfect phrase. What he does achieve however is to create characters one finds oneself talking about years afterward as if they were people one knew, with problems as urgent as one’s own.

Half a century ago, Norman Podhoretz accused Wouk of lacking moral sophistication. Here’s an extract from Podhoretz’s harsh 1955 review of Marjorie Morningstar, Wouk’s first major post-Caine novel:

That Wouk should pass for a serious writer is perhaps no more an occasion of surprise than the success of a dozen other inconsequential novelists. But an error of taste alone obviously cannot account for his reputation. The people who enjoy Wouk, I would guess, read him earnestly, with a reverence they never feel when confronted by, say, Thomas B. Costain or Sloan Wilson. His books are not “mere entertainment,” time-killers to carry on the subway; they “stimulate the mind,” they “provoke thought.” Marjorie, like The Caine Mutiny (which is, incidentally, a better novel), gives its audience a satisfied sense of having grappled with difficult questions, of having made an honest, painstaking effort to examine both sides of a problem before reaching a mature decision.

Podhoretz would later recant the severity of his assessment. Yet he wasn’t wrong in saying that moral ambiguity is not Wouk’s idiom. The Caine Mutiny builds to a big set-piece speech by the attorney who wins acquittal for the mutineers. In that speech, the attorney angrily condemns the mutineers for failing to appreciate that it’s men like Queeg who keep the Navy afloat in between great wars. The speech might have jolted us into rethinking our view of Queeg … if Wouk hadn’t so relished depicting Queeg as not merely a paranoid tyrant, but also an incompetent seaman, a coward in the face of the enemy, and a petty crook and cheat.

But if the case for and against Queeg isn’t as morally challenging as Wouk might imagine, Queeg as a character is absolutely unforgettable. His name is familiar even now to people who have no idea what book it comes from. How morally complex are the characters of the early Dickens, really? They are real, they are memorable, and that’s enough to prove their literary power.

In his famous essay on the fox and the hedgehog, Isaiah Berlin characterized Wouk’s model, Tolstoy, as a fox who wanted to be a hedgehog. (The fox, as you’ll remember, knows many things, while the hedgehog knows one big thing.) Wouk comes as close to being a hedgehog as probably any novelist can. Wouk’s novels aren’t books that yield a different point of view on a second reading. Every time you read them, they will say the same thing. Yet if didacticism is Wouk’s worst fault as a writer, it is not the fault that has done most damage to his reputation. Contemporary critics don’t mind didacticism in the right cause. (See Walker, Alice, career of.) Wouk’s, however, was very much the wrong cause.