Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 426

May 28, 2015

Manson Family Aside, Aquarius Is Just Another Cop Drama

Starting with its title, NBC’s Aquarius is a TV show at war with its own contradictions. The year is 1967, and as the song goes, it’s the dawning of the Age of Aquarius—flower children are converging on California, drugs and free love are flowing, but, sadly, there are still crimes to be solved. There’s plenty of weight to this “event series,” debuting Thursday, which among other things promises to tell the story of Charles Manson’s rise to depravity in the San Fernando Valley. But most of all, it’s a straightforward cop show, starring David Duchovny as a bullet-headed detective who has a few things to learn about the changing world around him—and the show’s rigid adherence to the conventions of that genre is its ultimate limitation.

Related Story

'American Crime'' Tackles Fear and Loathing in the U.S. Justice System

In the pilot, a lifer sergeant, Sam Hodiak (Duchovny), teams up with a shaggy-haired undercover cop, Brian Shafe (Grey Damon), to infiltrate the seedier side of California’s hippie revolution. But their partnership feels as staid as the show’s case-of-the-week plotting—specific not to 1967, but to any odd-couple cop drama from TV history, with Hodiak as the veteran tough guy who’s not afraid to rough up a suspect, and Shafe as the young innovator trying to teach him some new tricks.

Aquarius has a little fun portraying L.A. police work in the late-60s. The Miranda warning is new enough that Hodiak can’t remember it, and he frequently struggles to recite it to every collar he hauls in. But given the grim tenor of the show, NBC could have done even more to coax humor out of the unique time period and place. Meanwhile, the network has spared no expense on the show’s music, a greatest-hits medley of late-60s classic rock that fits nicely with the slightly grimy visuals and retro opening titles. Going vintage is perfectly appropriate in those instances—it’s just a shame the plotting feels so similarly old-fashioned and unoriginal.

Aquarius is being positioned by NBC as a miniseries—though its creator says there’s more story for future seasons if it does well, its “event” positioning at the start of summer suggests that the network considers it a potential one-time deal. In an unusual experiment, NBC is putting the entire series online the day after it premieres, while also airing it week-to-week—a mix of the Netflix binge-streaming approach and the model that it’s relied on for some 75 years. This strategy also reflects the two-pronged nature of Aquarius’s 13-episode story arc, which charts Hodiak’s week-by-week descent into the hippie underworld, and his longer-term investigation into Charles Manson’s growing Family.

The involvement of Manson (played by Gethin Anthony, best known as Renly Baratheon on Game of Thrones) is ostensibly Aquarius’ biggest hook, since it can blend its staid cases of the week with the much more lurid true-crime material of Manson’s cult. However, anyone looking for real drama should check the date again: Aquarius is set in 1967, and the infamous Tate-LaBianca murders that earned Manson’s notoriety didn’t happen until 1969, bringing a chilling end to the movement that’s only beginning in Aquarius’ first season. Anyone watching will know what Manson and his cultists will ultimately be capable of—but that’s likely several TV seasons down the road, and Hodiak isn’t going to change history. So why involve Manson at all?

Forgetting its 60s setting, Aquarius might as well be any other network crime show that wring drama from sexual victimization.The answer is a sad one: Even though Manson’s crimes have been thoroughly dissected in books, films, and TV shows over the years, it still makes for reliable, exploitative crime-show fodder. Forgetting its 60s setting, Aquarius might as well be The Following or Criminal Minds or innumerable other network crime shows that wring drama from sexual victimization—especially of young women. Manson is introduced via one of his newest inductees, Emma Karn (played by Emma Dumont, formerly of Bunheads), who’s drawn to the communal lifestyle of his group but is quickly coerced into sexual servitude. Manson was, of course, a serial abuser of women (and men), but he’s also the charismatic co-star of this drama, and the show tries to present the ugly truths of his crimes while also conveying a sense of his magnetism.

But it doesn’t work. A lot of that is to blame on Anthony’s performance—he wisely shies away from going too big, since Manson has been portrayed onscreen as a raving lunatic several times already. Instead, he makes the regrettable decision to alternate between charming and sullenly evil, talking up his music to record producers in one scene and holding a straight razor to his latest victim’s throat in the next. It’s a facile portrayal of villainy, and it reeks of the cop-show laziness that Aquarius can’t shake even with its period flair. Every time the show looks like it might wade into ambiguous territory, it snaps back to that dull morality: Manson is a bad man, Hodiak the hero who must hunt him down. It’s hard to disagree, but it’s also hard to really care.

Action Bronson and Hip-Hop's Never-Ending Misogyny Debate

The rapper Action Bronson, whose major-label debut came out recently, is mostly known for his love of food, his large frame, and the fact that he sounds so much like Ghostface Killah that even Ghostface Killah gets confused sometimes. He will likely now be known by more people for one particular lyric of his, due to a headline-making petition asking Toronto’s NXNE music festival to kick the artist off the bill because, in its words, he “glorifies gang-raping and murdering women.”

The lyrics in question come from the 2011 song, “Consensual Rape,” which has a verse that mentions giving a girl MDMA and then having very rough sex with her. The petition also calls out a 2011 music video that portrays Bronson happily disposing of a woman’s corpse.

Related Story

A$AP Rocky and the Liquifying of Rap

Though the protest has attracted enough interest for the festival to respond to it, it’s also been met in the rap world with a good amount of eye rolling. Part of the reason is that the materials being discussed are relatively obscure entries in Bronson’s back catalogue. “It's so funny the song that is causing these Torontonians to have their panties in a bunch literally has never been performed, ever,” Bronson tweeted. “5 years ago a lost track. That's what u base UR argument on? HOW ABOUT THE 9 PROJECTS THAT HAVE COME OUT SINCE? Don't single me out.”

Don’t single me out. It’s the natural first thought when anyone attacks a particular rapper’s particular bit of nasty wordplay. The entire genre is so suffused in misogyny—not just rape, but emotional cruelty, insults, and the portrayal of women as sex objects to be collected—that the topic has its own Wikipedia page. “Man, if you're upset about Action Bronson lyrics wait until you hear about rap music,” tweeted music critic Gary Suarez.

The truth is, though, that rapping about date rape may be one of the few topics that will actually get people in trouble. In 2013, Reebok dropped Rick Ross from an endorsement deal after he rapped the line, “Put molly all up in her Champagne, she ain't even know it, I took her home and I enjoyed that, she ain't even know it.” The outrage was such that, after a few botched attempts at excusing himself, Ross apologized, saying the lyric represented “one of my biggest mistakes and regrets.”

The Bronson lyric, which resembles the Ross one in its mention of giving a girl MDMA, is slightly more open to interpretation. A counter-petition, which has as of this writing … 11 … signers, argues that there’s no reason to think that the drug use in the verse was non-consensual—see the song title—and that, “None of the sexual acts described are illegal, and in a court of law this would not stand as proof that a rape has occurred.”

Still, it’s sort of bizarre that legal definitions, release dates, and close readings are the means by which it’s determined whether a rap lyric has gone “too far.” The conversation over sexism in rap can quickly become tedious because it’s hard to parse one rapper’s words without indicting the entire genre. Every so often, a public figure will snipe at rap for its lyrical content, starting a predictable cycle in which the person overstates their claims and hip hop’s defenders paint the critic as being clueless and, worse, using a double standard. Rock and roll is full of women-degrading, violent, and racist lyrics, too, and yet no one’s protesting outside Rolling Stones concerts.

Other defenders point to the genre’s history of reflecting broader mores—blame society, in other words, not the art it documents. Or they cite how rap’s identity as escapist art is inextricably tied to provocation, and the idea that rapping about something isn’t the same as endorsing it.

Some people decide on a case-by-case basis who they can stomach listening to. Others decide they can enjoy songs in spite of their messages.The NXNE festival has released a statement saying that it will not drop Bronson, noting that he performed at the same event in 2012 without controversy, and that attendees will have plenty of other musicians to choose from. "NXNE will also present a number of rap artists at various venues, such as Tink and Kate Tempest, who have be lauded for the undisguised feminist viewpoints in their music,” NXNE managing director Sara Peel said in the press release. “That being said, in the interest of moving forward in a positive manner, we are engaging in discussion with our community about this important issue, and looking to provide opportunities for concerned voices to be heard."

It’s a pretty good response, one that highlights the many different kind of artists and ideologies that exist within rap. One way of being a hip hop fan is realizing that you can enjoy a song in spite of its messages, just as you can enjoy any work of art in spite of some flaws. Another way is to decide on a case-by-case basis who you can stomach listening to and who you can’t. This isn’t the first time someone has called Action Bronson out for his attitudes towards women, and he’s neither apologized nor repudiated his 2011 work. So even before the petition made news, there may have been rap-listening NXNE ticketholders who’d planned to skip his set.

But it’s hard to not feel a little preemptive fatigue at the festival’s call for another public discussion of the topic. Not because the matter shouldn’t be discussed or that hip-hop shouldn’t change, but because the conversation has been happening for decades. Every few years, there’s a new flashpoint for widespread condemnations and defenses of the genre—2 Live Crew, Eminem, Odd Future—but most popular rappers’ treatment of women has barely altered at all. In 2013, when Kanye West released Yeezus, the rap critic Brandon Soderberg wrote a searching essay on the matter, asking whether the West album and the Ross controversy marked “the tipping point for rap misogyny.” But just this week, A$AP Rocky released a bound-to-be-successful album featuring a casual hint of violence towards a woman and a verse dissing a female pop star by name for refusing to swallow during oral sex.

Lots of other things about rap have evolved over the years. The word “fag” isn’t heard very often anymore. The number of commercially viable female rappers appears to be on the rise. Political lyrics seem back in style, with artists like Kendrick Lamar discussing the same problems that led to the Black Lives Matter movement. Then again, you could make similar observations about art forms from film to literature right now. That sexism persists probably says something about just how deeply ingrained it is, both in rap, and everywhere else.

The Dark Side of Design

The cognitive scientist Steven Pinker’s book The Better Angels of Our Nature posits that despite new high-tech methods of destruction and ongoing global conflicts, the world has overall become a less violent place. But this claim didn’t seem completely right to Paola Antonelli, a senior curator at the Museum of Modern Art, and to Jamer Hunt, the director of Parsons’ graduate program in transdisciplinary design. They instead believed that designers, intentionally or unintentionally, may have simply helped violence mutate into other, new forms.

Related Story

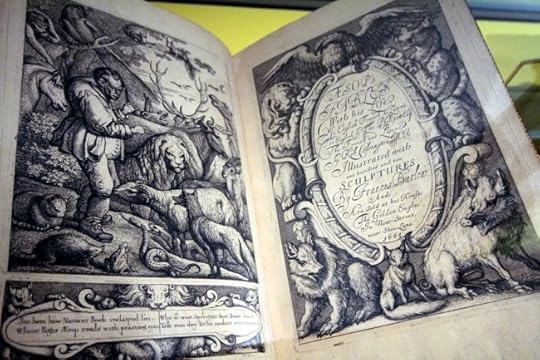

Pinker’s book inspired Antonelli and Hunt to curate Design and Violence, a hybrid “exhibition” and critical forum that has been hosted online by MoMA for the last 18 months. This week the museum published a book of the same title that addresses the impact of design on everything from shooting targets to lethal injection drug cocktails. The project looks specifically at changes that occurred after 2001—a watershed year for the perception of violence in the United States.

The project is organized around four different themes—“Hack,” “Control,” “Trace,” and “Annihilate”—and the website includes essays from critics and experts from outside the design world, including NPR’s Jad Abumrad, the novelist William Gibson, and the media mogul Arianna Huffington.

Unknown designer. The Protection Mask (also known as a bite/spit mask). c. 2000. Polyurethane, 7 2/3 x 6 3/4 x 6". Photograph by Jamer Hunt

Unknown designer. The Protection Mask (also known as a bite/spit mask). c. 2000. Polyurethane, 7 2/3 x 6 3/4 x 6". Photograph by Jamer Hunt The “Hack” section considers non-violent objects, such as the mundane box cutter, that have been repurposed for violent ends, regardless of the designer’s original intention. 3D printers, similarly, have been used to make guns. But, as Antonelli noted, 3D printers also prompt us to think about how open-source design can subvert subtler forms of violence such as governmental control of intellectual property. Sometimes hacked objects can be transformed from neutral to beneficial, Antonelli said, as when protesters in Istanbul’s Taksim Square used cleaning-product containers to spray milk into their eyes to minimize the effects of tear gas.

The curators said in an email that they noticed some surprising responses to the essays that appeared on the website. For one, people were more outraged about designs that engender forms of violence toward animals than toward humans. An analysis of Temple Grandin’s Serpentine ramp, designed to make the slaughter of cattle more humane, remains the most-discussed post on the site. “People were far less affected by the design of the lethal-injection cocktail, for example, even when we invited Ricky Jackson, an exonerated Death Row prisoner, to write a very eloquent response,” they said.

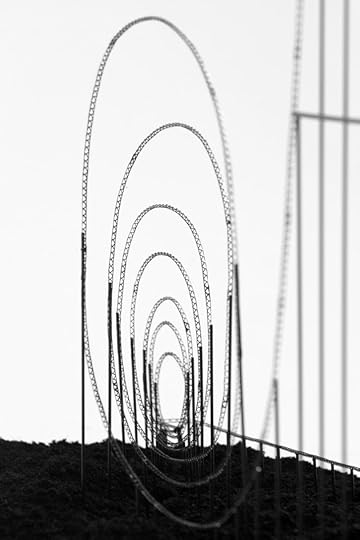

Antonelli recalled one particularly memorable reply from a commenter suffering from chronic pain who defended a speculative project by Julijonas Urbonas called Euthanasia Coaster. The metaphoric roller coaster was conceptually designed to humanely kill its passengers after offering a range of experiences, from euphoria to thrill, from tunnel vision to a loss of consciousness. Hunt and Antonelli said this kind of audience engagement is central to the project and wouldn’t have been possibly in a more traditional museum setting, which remains the standard of validation for critics. Design and Violence’s online hybrid form allowed the curators to “embrace ambiguity and even consider the necessity of violence, or at least its inescapable connection to design and life,” Antonelli said.

Euthanasia Coaster. Courtesy of Julijonas Urbonas

Euthanasia Coaster. Courtesy of Julijonas Urbonas

May 27, 2015

How Nebraska Abolished the Death Penalty

Nebraska on Wednesday became the first conservative state in more than four decades to repeal the death penalty. Its legislature, officially non-partisan but dominated by Republicans, voted by the narrowest of possible margins to override a veto by Governor Pete Ricketts, and enact a law scrapping a punishment that the state has struggled to carry out.

The final vote occurred amid a fierce lobbying campaign on both sides, but the outcome was years in the making: In the end, a growing coalition of liberals, religious groups, and libertarian-minded conservatives overcame more traditional tough-on-crime Republicans who saw the death penalty as the appropriate, ultimate punishment for murder. Underlying that ideological debate, however, was a far more pragmatic consideration. Nebraska has been unable to kill any of the murderers sentenced to death by its legal system since 1997.

In 2009, the state became the last in the nation to adopt lethal injections as its mode of execution, after its highest court ruled the electric chair unconstitutional. Yet like several other states, it has had a hard time procuring the cocktail of drugs needed to carry out the death penalty, and its lethal-injection chamber has remained dormant. That failure has given momentum to opponents of capital punishment, including a new group of conservatives that has invoked fiscal and religious arguments to woo right-leaning legislators to their side.

“It’s not just about the procurement of drugs,” said Marc Hyden of Conservatives Concerned About the Death Penalty, an organization that sprouted up in Montana several years ago and has since expanded nationally. “It’s not pro-life because it risks innocent life. It’s not fiscally responsible because it costs millions more dollars than life without parole.” Yet Nebraska’s bumbling and occasionally shady attempts to carry out death sentences—along with incidents in neighboring states like the botched execution of Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma—have given rise to another argument that sells among conservatives: the death penalty is just another example of government run amok.

“At the end of the day, this is just another big government program that’s really dangerous and expensive but doesn’t achieve any of its goals,” Hyden told me, summarizing his pitch to Republicans. “They don’t need to ask themselves, ‘Do some people deserve to die?’ The question they need to ask themselves is, do they trust an error-prone government to fairly, efficiently and properly administer a program that metes out death to its citizens? I think the answer to that is a resounding no.”

“Do they trust an error-prone government to fairly, efficiently and properly administer a program that metes out death to its citizens? I think the answer to that is a resounding no.”For liberal activists who have long opposed the death penalty on the grounds that it is immoral and an ineffective means of deterring violent crime, the conservatives have been a welcome, if unlikely, allies. “This has been a slow, steady move toward repeal,” said Stacy Anderson, executive director of Nebraskans for Alternatives to the Death Penalty. Danielle Conrad, executive director of the state chapter of the ACLU, cited the state’s unicameral, non-partisan legislature—unique in the U.S.—and a recent term-limits law that facilitated the election of more libertarian-leaning senators in recent years. While advocates say the death penalty has rarely if ever factored into election campaigns, it has been kept alive by the state’s longest-serving legislator (and its first African American state senator), Ernie Chambers, who has championed a ban for decades. (The new term limits forced him to sit out a term before his reelection in 2012.) “Each time that the Nebraska legislature takes this up, we get a little bit further down the road, a little bit closer to repealing the death penalty,” Conrad said.

Support for repeal reached its apex last week when, during a third round of voting, 32 out of the 49 senators backed legislation that went to the governor’s desk. Ricketts has aggressively lobbied legislators to sustain his veto, arguing that the death penalty was necessary and announcing that he had struck a deal with a pharmaceutical company to obtain the drugs needed to carry it out. “Repealing the death penalty sends the wrong message to Nebraskans who overwhelming support capital punishment and look to government to strengthen public safety, not weaken it,” the governor said in his veto message. He urged citizens to contact their senators, and he said the decision over whether to override his veto would “test the true meaning of representative government” and whether the 10 men now on death row would ever receive their rightful sentence.

In a two-and-a-half hour debate on Wednesday, some legislators agonized over the decision, including those who said they were under tremendous pressure from constituents to maintain the death penalty despite their own reservations. Senator Tyson Carson said he would vote to sustain Ricketts’s veto only because he had campaigned in favor of capital punishment, but he suggested he had changed his mind. “This might be the last time I give the state the right to take a life,” he said, as his voice broke. A few lawmakers read passages from the Bible, while others voted to kill the death penalty because, they said, the state’s system was simply broken.

Ultimately, supporters of repeal garnered exactly the number of votes they needed—30—to override the veto, and the death penalty fell. The question now is whether Nebraska will be an isolated example of a state that fumbled its ultimate punishment into extinction, or the first in a wave. “I don’t think Nebraska is unique in any way,” Anderson argued. “The same arguments that are resonating here are resonating across the country.”

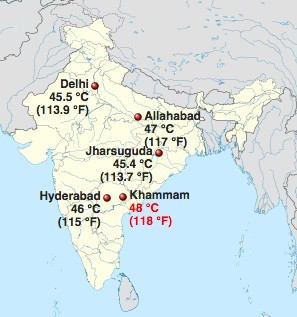

118 Degrees in the Indian Shade

“The capital remained on the roast pit for the fifth straight day,” The Times of India wrote Wednesday of New Delhi, which is in the grip of an unrelenting and deadly heat wave. The 113-degree high in India’s capital might be considered a relief when compared to temperatures in Balangir District to the southeast, where temperatures peaked at nearly 118 earlier this week.

On Tuesday, AFP reported that the mercury went as high as 122 degrees elsewhere the country, causing the roads to melt:

Photo of road melting in India's crazy crazy heat, from Hindustan Times. More than 1100 dead http://t.co/uKtnLT60IV pic.twitter.com/Y7PP8TGKJB

— Bill McKibben (@billmckibben) May 27, 2015

Most of those deaths across the country have occurred in just the past week. “Experts say that hot conditions should not usually lead to this many fatalities,” CNN noted. “But many of the affected areas in India are humid, which worsens the level of stress caused by excessive heat.” CNN also said that upwards of 800 million people—roughly two-thirds of India’s population—are already battling the extreme conditions without access to electricity.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia The Wall Street Journal placed the beginning of the catastrophe at the point “when cyclonic patterns of clouds and winds over the Bay of Bengal drifted away, bringing an abrupt end to pre-monsoon showers.” That turned one of India’s intermittent heat waves into a sustained one that has lasted now for weeks.

India’s summer heat claims lives every year. But the duration of this heat wave, along with India’s ongoing problems with infrastructure, power cuts, and some workers’ reliance on outdoor labor to support themselves, have helped make this year’s heat particularly deadly. "I get headaches, fever sometimes,” one scrap collector told Reuters. “But ... how will I make money?"

The elderly and the poor are also particularly vulnerable. Those hospitalized with heat-related ailments in the southern state of Telangana, one of the worst-hit states, were “mostly elderly people, and those working or living out in the sun,” one state official told The Wall Street Journal.

Temperatures in parts of the country hovered well into triple digits during the evening on Tuesday. In some parts of India, temperatures are expected to return to normal in the next few days. But for other parts of the country, there won’t be a respite until next week.

The 2016 U.S. Presidential Race: A Cheat Sheet

What does a guy have to do to get some respect in a presidential race?

Three years ago, in the 2012 election, Rick Santorum came out of political exile and a humiliating 2006 Senate defeat. No one expected him to go anywhere. Instead, he won the Iowa caucuses and ended up finishing second in delegate to Mitt Romney.

Now he’s back, formally announcing his new campaign on Wednesday. Yet once again, no one’s paying the Pennsylvanian much attention. There are, Trip Gabriel notes, several possible reasons. He’s a candidate of the past. (Wasn’t that true in 2012, too?) The field is stronger. His attempt at a blue-collar reinvention simply isn’t working. He has blasted new rules that limit GOP debates at 10 candidates—understandably, given that he’s polling at just 2.3 percent. With his kickoff in Cabot, Pennsylvania, today, he hopes to change that.

On Tuesday, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders—another candidate who represents his party’s ideological true believers—held a formal kickoff for his campaign. A lot has changed since Sanders made the formal announcement that he was running, during a hasty April 30 press conference outside the Capitol. Though the press has tended to present Sanders as essentially a loveable crank, he’s gained impressive momentum since then. His share of polls, while still some 50 points short of Hillary Clinton, has risen sharply. (Indeed, he has more support than Republicans Lindsey Graham, Bobby Jindal, Carly Fiorina, and John Kasich combined.)

If it remains hard to imagine Sanders winning the nomination (and it does), it’s also hard to brush him off anymore. His blunt form of left-wing politics adds an interesting dimension to the race. His success even threatens to squeeze out Martin O’Malley, who seemed poised to run as a progressive alternative to Clinton. But now the former Maryland governor is preparing his own announcement, planned for May 30.

On the Republican side, a large crop of expected candidates are near to finally making their decisions—spurred, perhaps, by the desire to make the cut for the GOP debates, which start this fall and are only going to take the 10 highest-polling candidates.

With so many candidates in the mix—some announced, some soon to announce, and some still on the fence—it’s tough to keep track of it all. To help out with that, this cheat sheet on the state of the presidential field will be periodically updated throughout the campaign season. Here's how things look right now.

* * *

The Republicans Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Rick Santorum

Who is he? Santorum represented Pennsylvania in the Senate from 1995 until his defeat in 2006. He was the runner-up for the GOP nomination in 2012.

Is he running? Yes, with a formal announcement on May 27.

Who wants him to run? Social conservatives. The former Pennsylvania senator didn't have an obvious constituency in 2012, yet he still went a long way, and Foster Friess, who bankrolled much of Santorum's campaign then, is ready for another round.

Can he win the nomination? It's tough to imagine. Santorum himself said his chances would hinge on avoiding saying "crazy stuff that doesn't have anything to do with anything." For now, his poll numbers remain in the basement.

Does his website have a good 404 page? No.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Bobby Jindal

Who is he? A former Rhodes Scholar, he’s the outgoing governor of Louisiana. He previously served in the U.S. House.

Is he running? Probably. He announced on May 18 that he is forming an exploratory committee, with a final decision to come after Louisiana’s legislative session ends on June 11.

Who wants him to run? It’s hard to say. Jindal has assiduously courted conservative Christians, both with a powerful conversion story (he was raised Hindu but converted to Catholicism in high school) and policies (after other governors reversed course, he charged forward with a religious-freedom law). But he still trails other social conservatives like Ted Cruz and Mike Huckabee.

Can he win the nomination? Probably not. Jindal still lacks traction at the national level, he faces an overcrowded field of social conservatives, and his stewardship of the state of Louisiana has come in for harsh criticism even from staunch fiscal conservatives. It’s hard to see how he gains momentum from here.

What else do we know? In 1994, he wrote an article called “Physical Dimensions of Spiritual Warfare,” in which he described a friend’s apparent exorcism.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Lindsey Graham

Who is he? A senator from South Carolina, he’s John McCain’s closest ally in the small caucus of Republicans who are moderate on many issues but very hawkish on foreign policy.

Is he running? Sure, why not?

Who wants him to run? John McCain, naturally. Senator Kelly Ayotte, possibly. Joe Lieberman, maybe?

Can he win the nomination? Not really. The South Carolina senator seems to be running in large part to make sure there’s a credible, hawkish voice in the primary. It seems like Graham started his campaign almost as a lark but has started to get into and enjoy the ride, plus he’s shown he’s a great performer on the stump. Molly Ball explores his chances in greater length here.

When will he announce? June 1.

What else do we know? It’s still amazing that the man has never sent an email.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Mike Huckabee

Who is he? An ordained preacher, former governor of Arkansas, and Fox News host, he ran a strong campaign in 2008, finishing third, but sat out 2012.

Is he running? Yes. He kicked off the campaign May 5.

Who wants him to run? Social conservatives; evangelical Christians.

Can he win the nomination? Huckabee's struggle will be to prove that he's still relevant. Since he last ran in 2008, a new breed of social conservatives has come in, and he'll have to compete with candidates like Ted Cruz. His brand of moral crusading feels a bit out of date in an era of widespread gay marriage—not least when curiously chose to attack Beyoncé. (His statements in support of Josh Duggar have also earned him criticism and quizzical reaction.) He faces fire from strict anti-tax conservative groups for tax hikes while he was governor. And fundraising has always been his weak suit. But Huckabee's combination of affable demeanor and strong conservatism resonates with voters.

What else do we know? Here is Huckabee's launch teaser video, with plenty of contrast with the Clintons.

Does his website have a good 404 page? It’s pretty good.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Ben Carson

Who is he? A celebrated former head of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins, Carson became a conservative folk hero after a broadside against Obamacare at the 2013 National Prayer Breakfast.

Is he running? Yes, after a May 4 announcement.

Who wants him to run? Grassroots conservatives, who have boosted him up near the top of polls, even as Republican insiders cringe. Carson has an incredibly appealing personal story—a voyage from poverty to pathbreaking neurosurgery—and none of the taint of politics.

Can he win the nomination? Almost certainly not. Carson's politics are conservative on some issues, but so eclectic as to be nearly incoherent overall. He's never run a political campaign, and has a tendency to do things like compare ISIS to the Founding Fathers. It's hard to imagine his candidacy surviving more serious scrutiny, but then again he's reportedly building an impressive political organization, especially in Iowa.

Does his website have a good 404 page? No.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Carly Fiorina

Who is she? Fiorina rose through the ranks to become CEO of Hewlett-Packard from 1999 to 2005, before being ousted in an acrimonious struggle. She advised John McCain’s 2008 presidential campaign and unsuccessfully challenged Senator Barbara Boxer of California in 2010.

Is she running? Yes, as of a May 4 announcement.

Who wants her to run? It isn’t clear what Fiorina’s constituency is. She’s a former CEO of Hewlett-Packard, but there are other business-friendly candidates in the race, all of whom have more electoral experience.

Can she win the nomination? Almost certainly not. Fiorina’s only previously political experience was a failed Senate campaign against Barbara Boxer in 2010. She has mostly been serving the role of harasser in the race so far, stirring up the news with slams on environmentalists for causing droughts (your guess is as good as mine), Obama for backing net neutrality, and Apple’s Tim Cook for speaking out on Indiana’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Mainly, though, she has strongly criticized Hillary Clinton, and some Republican strategists like the optics of having a woman to criticize Clinton so as to sidestep charges of sexism. Fiorina seems to be wowing voters in Iowa, but that hasn’t translated into national support—yet.

What else do we know? Fiorina's 2010 Senate race produced two of the most entertaining and wacky political ads ever, "Demon Sheep" and the nearly eight-minute epic commonly known as "The Boxer Blimp."

Does her website have a good 404 page? No.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Marco Rubio

Who is he? A second-generation Cuban-American and former speaker of the Florida House, Rubio was catapulted to national fame in the 2010 Senate election, after he unexpected upset Governor Charlie Crist to win the GOP nomination.

Is he running? Yes—he announced on April 13.

Who wants him to run? Rubio enjoys establishment support, and has sought to position himself as the candidate of an interventionist foreign policy.

Could he win the nomination? Charles Krauthammer pegs him as the Republican frontrunner. His best hope seems to be to emerge as a consensus candidate who can appeal to social conservatives and hawks, and he's even sounded some libertarian notes of late. He's well-liked by Republicans, and has surged forward since announcing, but he needs to move up from second choice to first choice for more of them. Rubio seems to scare Democrats more than any other candidate, too.

Does his website have a good 404 page? It’s decent.

Michael Vadon

Michael Vadon George Pataki

Who is he? Pataki ousted incumbent Mario Cuomo in 1994 and served three terms as governor of New York.

Is he running? Improbably, yes.

Who wants him to run? It's not clear. Establishment Northeastern Republicans once held significant sway over the party, but those days have long since passed.

Can he win the nomination? No. As my colleague Russell Berman previously noted, Pataki is one of the longest of the long-shot GOP candidates. He has touted his leadership as governor of New York on 9/11, but so did former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani. He was also a successful conservative governor in a deep-blue Northeastern state, but so was former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney. He seems be socially liberal enough to alienate primary voters, but not enough to capture Democrats.

When will he announce? May 28.

Does his website have a good 404 page? No.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Rand Paul

Who is he? An ophthalmologist and son of libertarian icon Ron Paul, he rode the 2010 Republican wave to the Senate, representing Kentucky.

Is he running? Yes, as of April 7.

Who wants him to run? Ron Paul fans; Tea Partiers; libertarians; civil libertarians; non-interventionist Republicans.

Can he win the nomination? That depends who you ask. The Kentucky senator would be an unorthodox pick, with many positions outside his party's mainstream. He's relatively permissive on drugs, passionate about civil liberties, and adamantly for restraint on foreign policy. But Paul has worked hard to firm up establishment ties since reaching the Senate, and he has recently worked to paper over his differences with GOP’s hawkish wing, calling for a declaration of war against ISIS and generally saber-rattling. He is positioning himself as a candidate with crossover appeal in the general election, and his announcement email mocked the idea that only an establishment candidate can win a general election.

What else do we know? One of Paul's greatest strengths is the base bequeathed to him by his father, three-time presidential candidate and former Representative Ron Paul. But as The Washington Post has reported, his father is also Senator Paul's biggest headache.

Does his website have a good 404 page? No.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Ted Cruz

Who is he? Cruz served as deputy assistant attorney general in the George W. Bush administration and was appointed Texas solicitor general in 2003. In 2012, he ran an insurgent campaign to beat a heavily favored establishment Republican for Senate.

Is he running? Yes. He launched his campaign March 23 at Liberty University in Virginia.

Who wants him to run? Hardcore conservatives; Tea Partiers who worry that Rand Paul is too dovish on foreign policy; social conservatives.

Can he win the nomination? Though his announcement gave Cruz both a monetary and visibility boost, he still starts with some serious weaknesses. Much of Cruz's appeal to his supporters—his outspoken stances and his willingness to thumb his nose at his own party—also imperil him in a primary or general election, and he's sometimes been is own worst enemy when it comes to strategy. But Cruz is familiar with running and winning as an underdog.

Does his website have a good 404 page? No.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Jeb Bush

Who is he? The brother and son of presidents, he served two terms as governor of Florida, from 1999 to 2007.

Is he running? Almost certainly.

Who wants him to run? Establishment Republicans; George W. Bush; major Wall Street donors.

Can he win the nomination? No one really knows. Since jumping into the race, he has continued to poll well and raise lots of money. He seems like a lock to rack up all-important endorsements from top Republicans. But predictions that he would quickly come to dominate the field have not come to pass, and while many analysts predicted that his moderate record would cause trouble in Iowa and with grassroots activists, that problem seems to be deeper than expected. His poll numbers are probably helped by his name, which is a double-edged sword.

When will he announce? No sooner than June, per The Washington Post.

What else do we know? Since Bush's surprise announcement, he has tended to stay fairly quiet, delivering some big speeches and hitting fundraisers, but not making a great number of trips to Iowa or New Hampshire.

Does his website have a good 404 page? No.

David Shankbone

David Shankbone Chris Christie

Who is he? What’s it to you, buddy? The combative New Jerseyan is in his second term as governor and previously served as a U.S. attorney.

Is he running? It seems ever harder to imagine. With indictments of two of his former top aides in early May, and a guilty plea by a high-school friend and political appointee, the George Washington Bridge scandal has crept ever closer to him. The New York Times says he's trying to "salvage" his campaign. Christie does have some campaign infrastructure in place in New Hampshire, which is close to his home state, with staffer hires and town-hall meetings there. He has also formed a political-action committee.

Who wants him to run? Moderate and establishment Republicans who don't like Bush or Romney; big businessmen, led by Home Depot founder Ken Langone.

Can he win the nomination? The tide of punditry had turned against Christie even before the "Bridgegate" indictments. It's hard to imagine how he recovers at this point, given the crowded field and the fact that Jeb Bush seems to dominate the moderate end of the Republican Party. Citing his horrific favorability nominations, FiveThirtyEight bluntly puns that "Christie's access lanes to the GOP nomination are closed." A recent Monmouth University poll showed him trailing even Donald Trump (see below) for the nomination. Plus, he'd probably have to resign as governor to run, because of SEC rules that cover donations from companies that do business with the state. With such high stakes, he might not want to run at all if he doesn't see a clear path to win.

When will he announce? According to Time, Christie has told donors that running is harder than he had realized, and that he may have to push back an announcement to as late as June.

What else do we know? If you can tell what is going on in this GIF, please let me know. Is he tossing the jacket away? Or catching it? And what does it mean?

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Scott Walker

Who is he? Elected governor of Wisconsin in 2010, Walker earned conservative love and liberal hate for his anti-union policies. In 2013, he defeated a recall effort, and he won reelection the following year.

Is he running? Almost certainly.

Who wants him to run? Walker's record as governor of Wisconsin excites many Republicans. He's got a solid résumé as a small-government conservative. His social-conservative credentials are also strong, but without the culture-warrior baggage that sometimes brings. And Walker has won three difficult elections in a blue-ish state.

Can he win the nomination? No one knows. For all his strengths, Walker has never run a national campaign and isn't exactly Mr. Personality. But Jeb Bush's emergence seems to have helped Walker, propelling him to the front of the pack as a more conservative alternative to Bush. He's now solidly in the top tier of candidates.

When will he announce? June.

What else do we know? Barack Obama took a shot on April 7 at Walker for his criticism of a nuclear-deal framework with Iran. That's a sign that he's becoming a power player, and sniping from the White House is only likely to elevate Walker's standing with Republicans. Good news, bad news: Walker has a geographic advantage in his proximity to Iowa, but a potential biological disadvantage from his allergy to dogs.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Rick Perry

Who is he? George W. Bush’s successor at governor of Texas, he entered the 2012 race with high expectations, but sputtered out quickly. He left office in 2014 as the Lone Star State’s longest-serving governor.

Is he running? Very likely.

Who wants him to run? Small-government conservatives; Texans; immigration hardliners; foreign-policy hawks. Noah Rothman makes a case here. (Perry's top backer four years ago, non-relative Bob Perry, died in 2013.)

Can he win the nomination? Maybe, but who knows? Perry and his backers insist 2016 Perry will be the straight shooter who oversaw the so-called Texas miracle, not the meandering, spacey Perry of 2012. We'll see. Perry has also made a point of quietly spending lots of time in Iowa, a strategy he didn’t use in 2012—but which Rick Santorum used very successfully.

When will he announce? June 4.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Sarah Palin

Who is she? If you have to ask now, you must not have been around in 2008. That’s when John McCain selected the then-unknown Alaska governor as his running mate. After the ticket lost, she resigned her term early and became a television personality.

Is she running? A bizarre speech in January made a compelling case both ways.

Who wants her to run? Palin still has diehard grassroots fans, but there are fewer than ever.

Can she win the nomination? No.

When will she announce? It doesn't matter.

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore Mitt Romney

Who is he? The Republican nominee in 2012 was also governor of Massachusetts and a successful businessman.

Is he running? Nah. He announced in late January that he would step aside.

Who wanted him to run? Former staffers; prominent Mormons; Hillary Clinton's team. Romney polled well, but it's hard to tell what his base would have been. Republican voters weren't exactly ecstatic about him in 2012, and that was before he ran a listless, unsuccessful campaign. Party leaders and past donors were skeptical at best of a third try.

Could he have won the nomination? He proved the answer was yes, but it didn't seem likely to happen again.

Gage Skidmore John Bolton

Gage Skidmore John Bolton Who is he? A strident critic of the UN and leading hawk, he was George W. Bush’s ambassador to the UN for 17 months.

Is he running? Nope. After announcing his announcement, in the style of the big-time candidates, he posted on Facebook that he wasn’t running.

Who wanted him to run? Even among super-hawks, he didn’t seem to be a popular pick, likely because he had no political experience.

Could he have won the nomination? Quantum physics teaches that anything is possible, but this would push it. A likelier outcome could be a plum foreign-policy role in a hawkish GOP presidency.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia John Kasich

Who is he? The current Ohio governor ran once before, in 2000, after a stint as Republican budget guru in the House. Between then and his election in 2010, he worked at Lehman Brothers. Molly Ball wrote the definitive profile in April.

Is he running? Almost certainly. He has visited early states, laid out ideas, and established a PAC.

Who wants him to run? Kasich’s pitch: He’s got better fiscal-conservative bona fides than any other candidate in the race, he’s proven he can win blue-collar voters, and he’s won twice in a crucial swing state. While his polling isn’t stellar, he still leads Graham, Fiorina, and Jindal.

Can he win the nomination? As Ball noted, Kasich seems in some ways perfectly suited to this race; in other ways, his insistent anti-charisma makes it hard to imagine him winning, and his attitude is amusingly blasé: “If they like it, great. If they don’t like it, I’ll play more golf.” He could be hurt by his embrace of Medicaid expansion under Obamacare, a move he had to circumvent the Republican-led General Assembly to make.

When will he announce? After June 30.

What else do we know? He doesn’t own a smartphone, and seldom uses a computer. Maybe he can be friends with Lindsey Graham—the old way, via U.S. Mail.

Donald Trump

Is he running?

Others Still in the Mix:

Bob Ehrlich, Peter King, Harold Stassen, Jim Gilmore

* * *

The Democrats Wikimedia

Wikimedia Bernie Sanders

Who is he? A self-professed socialist, Sanders represented Vermont in the U.S. House from 1991 to 2007, when he won a seat in the Senate.

Is he running? Yes. He announced April 30.

Who wants him to run? Far-left Democrats; socialists; Brooklyn-accent aficionados.

Can he win the nomination? No, although his campaign seems more about getting his ideas into the mix than about winning. In particular, he's an outspoken opponent of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the free-trade agreement President Obama is pushing. Hillary Clinton once seemed to back the deal, but she's offered far more equivocal statements since declaring her candidacy. But Sanders came out of the gate with strong fundraising numbers and has testily rebuffed reporters who suggest he can't win.

Does his website have a good 404 page? Yes, and it is quintessentially Sanders.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Hillary Clinton

Who is she? As if we have to tell you, but: She’s a trained attorney; former secretary of State in the Obama administration; former senator from New York; and former first lady.

Is she running? Yes.

Who wants her to run? Most of the Democratic Party.

Can she win the nomination? Duh.

What else do we know? Maybe a better question, after so many years with Clinton on the national scene, is what we don't know. Here are 10 central questions to ask about the Hillary Clinton campaign.

Does her website have a good 404 page? If you’re tolerant of bad puns and ’90s outfits, the answer is yes.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Joe Biden

Who is he? Biden, a longtime Delaware senator, is vice president and foremost American advocate for aviator sunglasses and passenger rail.

Is he running? He won't rule it out, but he's made no serious steps toward a run. He's addressing a "secretive" group of gay donors on May 2.

Who wants him to run? Joe Biden, maybe. The group Draft Biden (slogan: “I’m Ridin’ With Biden”) continues to do its best.

Can he win the nomination? If Clinton didn't run, it would throw the Democratic field into disarray. But probably not.

When will he announce? It seems ever more likely that he won't.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Jim Webb

Who is he? Webb is a Vietnam war hero and secretary of the Navy. The author of several books, he served as a senator from Virginia from 2007 to 2013.

Is he running? He has launched an exploratory committee.

Who wants him to run? Dovish Democrats; socially conservative, economically populist Democrats; the Anybody-But-Hillary camp.

Can he win the nomination? Probably not.

Does his website have a good 404 page? No.

Steven Senne / AP

Steven Senne / AP Lincoln Chafee

Who is he? The son of beloved Rhode Island politician John Chafee, Linc took his late father’s seat in the U.S. Senate, serving as a Republican. He was governor, first as an independent and then as a Democrat.

Is he running? He has launched an exploratory committee.

Who wants him to run? No one knows! Chafee's exploratory committee came out of nowhere, with little anticipation or fanfare or even rumors. He opted not to seek reelection as governor in 2014, in part because his approval rating had reached a dismal 26 percent.

Can he win the nomination? No. Chafee seems to be positioning himself as an economic populist and says Clinton's 2002 vote for the Iraq war should disqualify her (he was the only Republican senator to vote against it). In other words: He's Jim Webb with a less impressive resume, a less compelling bio (he's the son of longtime Senator John Chafee), and less of a political base. He gives himself even odds, though.

When will he announce? He says he wants to gauge support and fundraising and then decide in the next few months.

Does his website have a good 404 page? No.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Martin O'Malley

Who is he? He’s a former governor of Maryland and mayor of Baltimore.

Is he running? It’s virtually certain.

Who wants him to run? Not clear. He has some of the leftism of Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren, but without the same grassroots excitement.

Can he win the nomination? At the moment, O’Malley seems caught between Sanders, who has grasped the progressive mantle, and Clinton, who dominates the Democratic race overall. As with Sanders, though, it’s hard to see where O'Malley would get an opening unless Clinton’s campaign fell apart. The conventional wisdom since protests over the death of Freddie Gray is that protests in Baltimore undermine the case for his candidacy and make it harder for him to run, but he’s embraced the protests as a motivation for his run.

When will he announce? May 30 in Baltimore.

What else do we know? Have you heard that he plays in a Celtic rock band? You have? Oh.

Does his website have a good 404 page? No.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia Elizabeth Warren

Who is she? Warren has taken an improbable path from Oklahoma, to Harvard Law School, to progressive heartthrob, to Massachusetts senator.

Is she running? No. Seriously, no.

Who wants her to run? Progressive Democrats; economic populists, disaffected Obamans, disaffected Bushites.

Can she win the nomination? No, because she's not running.

A$AP Rocky and the Liquifying of Rap

To the Steve Jobs Hall of Fame for people who credit their creative breakthroughs to LSD, we can now add the 26-year-old rapper A$AP Rocky. The recent tabloid fixture and fashion tastemaker recorded his newly released sophomore album, At.Long.Last.A$AP, while holed up in Europe and apparently under the influence of psychedelic drugs, a fact about which he hasn’t been shy either in interviews or in songs. On one track, “Jukebox Joints,” he raps about people asking why he disappeared from the spotlight for a while. The answer is simple: “I'm tripping off the acid,” he explains, adding, “now yo’ ass is looking massive.”

Related Story

Sure enough, the first description that comes to mind when listening to At.Long.Last.A$AP is “druggy.” The songs collage tempos, styles, and echo-caked sounds, with backing vocals pitchshifted very low and melodies that coalesce from murk. This isn’t totally new: In his short but influential career—which includes making the 2012 top-10 hit “Fuckin’ Problems”—A$AP Rocky’s choice of production styles has gotten him lumped in with the “cloud rap” subgenre, whose name is pretty self-explanatory. But the difference this time out is that the song structures themselves have been liquefied, and the results are often thrilling.

Take “Fine Whine,” track three. For the first two minutes, it’s all comedown vibes, with a “slow, slow, slow” refrain from singer Joe Fox acting like the tempo notation in an Italian concerto. But then the taunts of the rapper M.I.A. cut in, and the drums start to pick up, hitting a congo-like gallop as another emcee, Future, unleashes his trademark warble-rap. Then it’s back to the comedown. The next track is called, descriptively, “L$D,” and it’s a mostly percussion-free singalong whose accompanying music video gives a good sense for Rocky’s greatest talents—imagery, coherence, vibes.

Interwoven throughout the album are Van Morrison-like bits of guitar and vocals from Fox, an amateur musician who Rocky says he found at 4 a.m. on a London street. His own particular skills probably matter less than the fact he’s there at all; like Kanye West bringing Bon Iver along to warble over baroque hip hop for My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy and Yeezus, the idea is to inject a bit of earnest campfire soul. Black soul appears too, both in samples and in new performances from singers like James Fauntleroy. Also in the mix: church bells, piano interludes, Rod Stewart as interpreted by Miguel, and a super-impressive guest verse from Lil Wayne.

Though it will burnish his status as an innovator, the album won’t dispel Rock’s reputation as an underachieving vocalist. His verses are often monotonous, his voice lacks the distinctive character of many of the emcees who appear alongside him, and his lyrical concerns are for the most part as generic as people who hate all rap assume most of the genre’s lyrics to be. Worse, his stock sexual boasting comes with a sickening mean streak: One verse in which he insultingly talks about a hookup with singer Rita Ora will go down as one of the ugliest pop-culture moments of the year. He makes a few nods toward inner-city crime, police, and the death of his friend and producer A$AP Yams, but it’s not like he’s out to make big statements. The opener “Holy Ghost” very clearly disses hypocritical clergy members, but Rocky recently told Complex that he “didn’t want this to get confused [as] bashing religion.”

Maybe the culture’s moving on from molly and its day-glo aesthetic.As strange as it is to say about a rap album, though, the words here are mostly beside the point. A$AP Rocky has touted his beatmaking on the album, and has coaxed a coherent and fascinating sound from a wide group of producers (including Danger Mouse, Mark Ronson, and Kanye West). LSD really does seem like the appropriate drug metaphor: Often the music’s as laid back as the work of any rapper who habitually touts booze and cough syrup, but like ‘70s prog rockers penning epic paeans to their third eyes, At.Long.Last.A$AP also features eruptions of sounds that beg to be described in visual terms. Rocky’s previous work has proved influential and other buzzed-about rappers have lately been name-dropping acid, so maybe the culture’s moving on from molly and its revved-up, day-glo aesthetic.

But it’s also likely that Rocky’s own personal drug fixation has happened to coincide with a creative flourishing across the genre. At a time when hip-hop rules the streaming-music economy, when distinctions between mainstream and alternative seem flimsy at best, standing out doesn’t necessarily mean executing well on an old formula. It means taking an original vision to its grandest scale. In a lot of ways, the sloshy, anything-is-possible soundscapes of Long.Last.A$AP feel related to some of the other big releases this year from young rappers who’ve left the underground. Both Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly and Tyler, the Creator’s Cherry Bomb also melt down radio-friendly song structures and instead offer long instrumental interludes, psychedelic textures, and tracks that shift styles without warning. Those two artists, incidentally, say they don’t take drugs.

The Clock Finally Runs Out for FIFA

Imagine this: A shadowy multinational syndicate, sprawling across national borders but keeping its business quiet. Founded in the early 20th century, it has survived a tumultuous century, gradually expanding its power. It cuts deals with national governments and corporations alike, and has a hand in a range of businesses. Some are legitimate; others are suspected of beings little more than protection rackets or vehicles for kickbacks. Nepotism is rampant. Even though it’s been widely rumored to be a criminal enterprise for years, it has used its clout to cow the justice system into leaving it alone. It has branches spread across the globe, arranged in an elaborate hierarchical system. Its top official, both reviled and feared and demanding complete fealty, is sometimes referred to as the godfather.

This organization isn’t the Mafia. It’s FIFA, the international governing body for soccer. But as anyone who’s ever watched a mob movie knows, even the best-laid schemes eventually hit rocky ground. For FIFA and its boss, Sepp Blatter, that moment came early Wednesday morning in Zurich, where seven top officials were arrested at a five-star hotel with views of Lake Zurich and the Alps.

The arrests came after a lengthy FBI investigation. In total, the Justice Department charged 14 people with 47 corruption counts, including racketeering, wire fraud, and money laundering, following “a 24-year scheme to enrich themselves through the corruption of international soccer.” In addition to FIFA officials, five corporate executives are charged, and Justice has unsealed several prior guilty pleas in the case. The FBI also raided the offices of CONCACAF, FIFA’s Americas affiliate, in Miami on Wednesday. The case originated in the Eastern District of New York; until her confirmation in April, that district was led by U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch.

Related Story

FIFA's Corruption Report Gets a Red Card

New York Times reporters, who’d apparently been tipped off, recorded the surreal scene in Zurich on Twitter. Swiss police, in street clothes, entered the deluxe Baur au Lac hotel. They arrived at the hotel bearing documents, and stopped at the front desk to request room numbers for their targets. Each of the targets apparently went quietly, with at least one bearing his luggage. The journalist Sam Borden overheard one of the arrested men asking another how he was. “Nervous,” the second replied. Police hustled them out of side doors and into waiting compact cars (it’s Europe, after all), using bedsheets to shield them from the media—a nod to restrictive privacy laws, but one that’s a bit slapstick given their high profiles. The hotel staff, meanwhile, reacted somewhat frantically to the proceedings.

Those arrested in Zurich will be extradited to the United States to be tried. Even as Swiss police shielded the men from public view, the U.S. Justice Department was trumpeting the arrests—only the most superficial sign of the deep differences between how various justice systems have historically approached FIFA. The British press has complained that even amidst allegations of corruption against FIFA, courts in Europe are unwilling to go after the organization—the sacrifices at stake in football-loving countries are simply too much. But The Telegraph’s Ben Wright argues the charges demonstrate that FIFA just isn’t able to intimidate the U.S. justice system in the same way—both because of a more aggressive mindset about white-collar crime, and because affection for soccer isn’t so ingrained. The academic Dan Drezner only half-jokingly suggests that the arrests are the best U.S. foreign-policy move of the year, with America taking on a powerful but widely disliked bully.

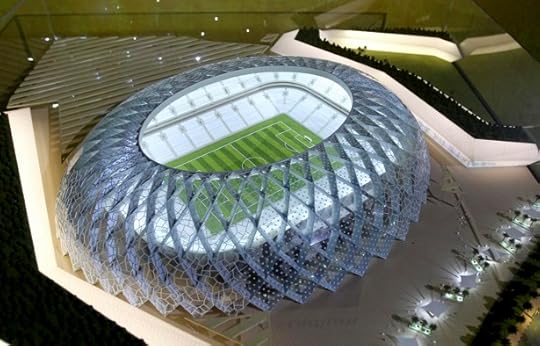

Meanwhile, the Swiss government announced it was opening investigations into the bidding processes for the next two World Cups, scheduled to be held in Russia in 2018, and in Qatar in 2022.

Allegations of corruption certainly aren’t anything new in global soccer. FIFA—which made $5.7 billion in revenue from 2011 to 2014—is in some ways perfectly designed to encourage fraudulent conduct. There’s no good analogue for FIFA in any other sport: It’s a huge multinational institution with billions in revenue that has a hand in practically every level of soccer, from children’s leagues up to the World Cup. With hundreds of different nationalities, dozens of languages, countries’ frantic jostling for position, and money sloshing around everywhere, FIFA is like a grand bazaar of soccer. And like any busy marketplace, it’s the perfect place for crime to flourish.

FIFA—which made $5.7 billion in revenue from 2011-14—is in some ways perfectly designed for fraud.Because of the prestige and potential economic benefits of hosting the World Cup, the process of bidding for it and rounding up support practically begs for bribery. Media and marketing rights, and the smaller, regional tournaments that lead up to the quadrennial World Cup, offer even more chances for potentially illegal dealings. FIFA’s rules also seemed geared toward shutting down any investigation that might smoke out trouble. One of the people indicted today is Jack Warner, the Trinidadian former head of CONCACAF. As Warner came under scrutiny in 2011 for trying to buy votes in his election and receiving millions in misappropriated funds, he resigned his post—automatically shutting down FIFA’s ethics investigations into his conduct.

Amid the chronic allegations of bribery, FIFA has also faced acute crises over the next two World Cups. The 2018 games, scheduled for Russia, have sparked outcry, both because of Russia’s human-rights record and involvement in Ukraine, and because of allegations of vote-buying in the process—allegations dismissed by a FIFA commission. The 2022 tournament in Qatar is, on its face, absurd: Why schedule an intensive tournament, in a sport that requires running for 90 minutes, in a country where summer temperatures generally exceed 100 degrees? The concern was exacerbated by brutal conditions during the 2014 Brazil World Cup, where unheard-of water breaks became essential.

Though Qatar promised to air-condition the field, the tournament was eventually pushed back to winter, disrupting league soccer schedules in the process. And vote-buying allegations have also dogged the tournament, along with accusations of human-rights violations and slave labor. Construction for the 2022 cup has relied heavily on poorly paid migrant workers. According to The Guardian, a worker died every two days on the project in 2014.

With so much at stake, the big trophy for any prosecutor is Sepp Blatter, the head of FIFA. Blatter, a 79-year-old Swiss national, has led the organization since 1998. The Argentine soccer icon Diego Maradona calls him a “dictator.” In April, Osiris Guzman, the Dominican soccer boss—who was suspended in a bribery inquiry in 2011—floridly compared Blatter to Moses, Jesus, Lincoln, Churchill, Martin Luther King, and Nelson Mandela. The Daily Mail, meanwhile, has called him a “smug, self-righteous Zurich gnome.” Other critics, deeming Darth Vader to be too humble an appellation, refer to him as Emperor Palpatine. Blatter seems to love the attention, even if it’s not all positive. FIFA spent an astonishing $26 million on a 2014 film featuring Blatter as a hero, in which he was played by the actor Tim Roth.

FIFA spent $26 million on a 2014 film featuring Blatter as a hero, in which he was played by the actor Tim Roth.Despite overseeing FIFA for most of the period covered by the FBI investigation, Blatter escaped indictment Wednesday—much to the chagrin of football fans worldwide. It’s another mafia-movie trope: the pater familias whom everyone believes to have dirty hands, but who seems to perpetually be one step ahead of the law.

But Blatter, who’s canceled his upcoming public appearances, might not be in the clear yet. His immediate challenge comes on Friday, when FIFA holds its election for the presidency. Blatter was widely expected to cruise to a fifth term—an outcome that may still hold, but which will surely be complicated and shadowed by the week’s arrests. FIFA’s spokesman insisted Wednesday that the organization was the victim in all of this—hurt by the malicious dealings of a few bad apples, no doubt.

In the longer term, the investigation is a blow to Blatter’s power. And there are signs that officials still hope to take him down. In a statement, Kelly Currie, the acting U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of New York, said: “Let me be clear: this indictment is not the final chapter in our investigation.” Soccer fans and anti-corruption campaigners around the globe will be watching for the next chapter as avidly as any qualifying match.

Protecting Priceless Art From Natural Disasters

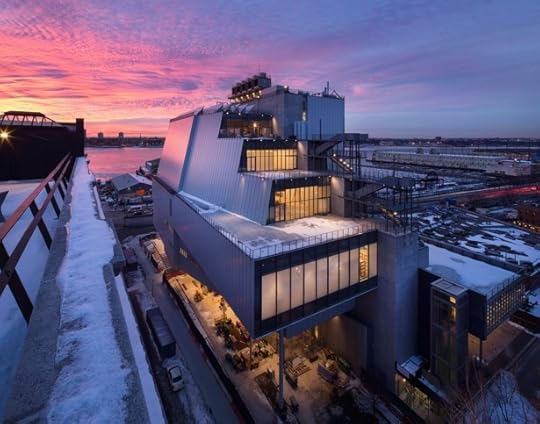

In New York City, toward the southern end of the High Line, a new building seems to float gracefully above the ground. Some critics have compared it to a ship, a nod to New York’s nautical past. But its angled gray surfaces, and the way in which it hovers in the air suspended on thin columns, make it seem more like a spaceship version of Michael J. Fox’s DeLorean in Back to the Future.

Related Story

Are Fine Art Museums the Next Starbucks?

The building, which opened on May 1, is the architect Renzo Piano’s new Whitney Museum of American Art, following a relocation from the museum’s old home on the Upper East Side. Piano himself has acknowledged the aeronautical aspects of the building’s design. “The new Whitney is almost ready to take off. But don’t worry, it won’t, because it weighs 28,000 tons,” he told a crowd at the official opening event.

The reviews of the new design have been glowing (The New York Times called it a “glittery emblem of a new urban capital.”) But the new Whitney’s most intriguing feature might be one that’s gone largely unnoticed: its custom flood-mitigation system, which was designed halfway through the museum’s construction, in the aftermath of 2012’s Hurricane Sandy, when more than five million gallons of water flooded the site. The system’s features include a 15,500-pound door designed by engineers who build water-tight latches for the U.S. Navy’s Destroyers. “Buildings now have to be designed like submarines,” said Kevin Schorn, an assistant to Piano, reflecting on the demands of a warming world and what it might mean for design. “Do we have to completely rethink our infrastructure? Do we have to completely rethink everything?”

Nic Lehoux

Nic Lehoux The Whitney’s system, with its technical sophistication and aesthetic sleekness, is proving to be a model for other U.S. art museums asking the same questions. While the country has been stuck in a surreal debate over the reality of climate change, disaster-preparedness has become a matter of pressing concern, and institutions in vulnerable areas are having to respond in real time. The museum’s actions—turning to specialists in naval engineering, for example—augur an era of improvised ingenuity, of localized efforts to address a problem in dire need of a global solution.

***

The Whitney, whose lobby is 10 feet above sea-level, is now designed to be water-tight against a flood level of 16.5 feet—seven feet higher than waters reached during Hurricane Sandy. The fortification includes a 500-foot-long mobile wall, comprised of stacked aluminum beams, that can be erected in less than seven hours. The flood door, located inside the building’s western facade facing the Hudson River, is 14 feet tall by 27 feet wide, and looks like something you might find at the back of an aircraft carrier. But despite its mass, the door is perfectly balanced so that a single person can push it shut. Both the wall and door are designed to withstand 6,750 pounds of impact from debris.

Schorn, an engineer who helped design almost every aspect of the Whitney’s exterior, has spent the past four years flying around the world while finalizing its various elements. As such, the story of the Whitney’s construction reads like a particularly rapturous passage from a Thomas Friedman book on globalization. The steel for the exterior gray planks originated in Belgium and was shipped to Germany to be cut and pressed by a special device. The pre-cast concrete was made in Quebec. The windows’ color-neutral, low-emissivity (i.e., heat-reflective) glass was made in Germany. The stone in the lobby is Spanish, but was shipped to Italy to be cut and fabricated. The lighting came from Italy; the audio-visual system from Canada.

While the country has been stuck in a surreal debate over the reality of climate change, institutions in vulnerable areas are having to respond in real time.Along with the more technical concerns, Piano also wanted to preserve the aesthetics of the building, which required engineers to design a flood-mitigation system that was all but invisible. And they succeeded: Reviews of the building have noted its interactiveness with the surrounding neighborhood, due to the lack of barriers between the interior and piazza-like space outdoors. “At the Whitney you’re kind of always in New York, always in the West Village, a little bit like you would be if you were with the artists in their studio,” Schorn said.

While flooding is a worldwide phenomenon—whether from storms or yearly rainy seasons—it’s only recently that interest in prevention has spiked. “After Sandy, the number of inquiries skyrocketed for us,” said Tom Themel, an engineer at Walz & Krenzer who helped design the Whitney’s system. “There’s no really comprehensive program that protects the entire city, literally building by building.”

The Whitney’s move to build a flood-protection system may be pointing to the future of Manhattan architecture. Until the city decides to invest in something like the former Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s $20-billion proposal for seawalls, buildings in vulnerable areas will be similarly exposed. The Harvard geologist Daniel P. Schrag has cited Hurricane Sandy's 13-foot storm surge as an example of what will, by 2050, be the “new norm on the Eastern seaboard.” And leading climate scientists have predicted that the intensity of hurricanes will increase in a warmer climate. (Sandy caused roughly $70 billion in damage overall and the deaths of more than 230 people.)

The Whitney’s flood-mitigation system includes a temporary wall and two flood doors, all designed by Walz & Krenzer. Kevin Schorn

The Whitney’s flood-mitigation system includes a temporary wall and two flood doors, all designed by Walz & Krenzer. Kevin Schorn Other art institutions are taking similar precautions, in New York and beyond. In 2013, the Pérez Art Museum Miami moved into a cutting-edge facility that was specifically designed to withstand hurricanes. The museum is raised on an elevated platform above the flood plain and features the largest sheets of hurricane-resistant glass in the U.S. Its art storage space is more than 46 feet above sea level, and its signature hanging gardens are reinforced with enough steel to withstand category-five hurricane winds. The museum also features an advanced backup-electricity system that runs on generators. “We can be refueled by truck or by barge,” noted Alexa Ferra, the Pérez’s public relations manager.

Similarly, the Rubin Museum of Art, in Manhattan’s Chelsea, has a disaster-preparedness plan that runs 151 pages, and a few years ago invested in fortifying its roof against flooding and high-speed winds. The museum faced challenges in the aftermath of Sandy that it never anticipated: “Simple things, like not being able to charge a cell phone,” said Patrick Sears, the museum’s executive director. “We now have high-capacity, long-term storage batteries on site just for that reason.” Sears compared the unpredictable, evolving challenge of protecting art from environmental threats to the mission of a hospital. “We think of the art as being patients,” he said. “And we don’t want them to die.”

The 9/11 Memorial and Museum, in lower Manhattan, took on 22 million gallons of water during Sandy and was flooded with seven feet of standing water, prompting it to work extensively with the Port Authority to assess its vulnerabilities. (An adjacent construction site had caused water to pour in.) Joe Daniels, the Memorial’s president and C.E.O., said the museum took precautions to make sure the premises were sealed and equipped with enough pumping power in case of leaks. Additional protocols were also put in place to move sensitive artifacts to higher ground if need be.

“We think of the art as being patients, and we don’t want them to die.”While the Museum of Modern Art sits on more protected ground in mid-Manhattan, its storage facility in Long Island City is near sea-level. Several years ago the museum invested in a flood-retaining pool, which helped keep the facility dry during Sandy. “Obviously we’re on higher alert post-Sandy,” said James Gara, the MoMA’s chief operating officer, “and we have more backups, as anyone would have.” Gara said the museum was considering other investments, looking ahead to the possibility of even more catastrophic events that could cause a longer-term loss of power.

These days, the Meatpacking District doesn’t feel like a neighborhood that’s threatened by the elements; rather, it’s enjoying a new cultural vibrancy. The Whitney—“a building that flies,” Renzo Piano said at the ribbon-cutting ceremony, with Michelle Obama sitting nearby—looms large above it all, helping revitalize this little triangle of Manhattan between the West Village and Chelsea.

For now, the only sign of the threat looming on the horizon are the small, nearly inconspicuous holes on the sidewalk—where the mobile wall's posts lock into the concrete—wrapping around the eastern, southern, and western sides of the building in perfectly spaced pairs. The day will come when they’re needed. Until then, the aluminum beams remain stowed in a warehouse, the 15,500-pound door opened wide, waiting to protect billions of dollars’ worth of American art.

The piazza-like atmosphere outside is relaxed and festive, a testament to the power of architecture to take what might have been closed and forbidding and render it open and inviting. And this openness, the lack of barriers between the museum and the city, is made feasible by the simple fact that, in a matter of hours, this stunning new American landmark can transform itself into a fortress.

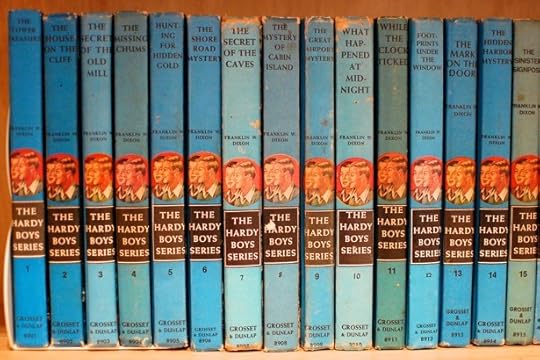

The Mystery of the Hardy Boys and the Invisible Authors

In the opening pages of a recent installment of the children’s book series The Hardy Boys, black smoke drifts though the ruined suburb of Bayport. The town's residents, dressed in tatters and smeared with ash, stumble past the local pharmacy and diner. Shards of glass litter the sidewalk. “Unreal,” says the mystery-solving teenager Joe Hardy—and he's right. Joe and his brother Frank are on a film set, and the people staggering through the scene are actors dressed as zombies. But as is always the case with Hardy Boys books, something still isn’t quite right: This time, malfunctioning sets nearly kill several actors, and the brothers find themselves in the middle of yet another mystery.

Related Story

Eighty-five years have passed since readers first encountered both the Hardy Boys and their teen-detective counterpart, Nancy Drew, yet new books continue to be released several times a year. The novels bear the same pseudonyms as the originals: Franklin W. Dixon and Carolyn Keene. A few things have changed, though—characters listen to MP3 players and reference science-fiction movies, and Hardy Boys chapters (oddly) alternate between the first-person perspectives of Frank and Joe. But the main modern achievement of the series is simply that it continues to exist.

The secret behind the longevity of Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys is simple. They’re still here because their creators found a way to minimize cost, maximize output, and standardize creativity. The solution was an assembly line that made millions by turning writers into anonymous freelancers—a business model that is central to the Internet age.

* * *

If writing seems like a lonely profession, try ghostwriting children's books. “You're usually in touch with one person, the editor,” says Christopher Lampton, who wrote 11 Hardy Boys books in the 1980s. He sent his books not to a publisher but to a packager called Megabooks—effectively a conduit between the writer and the publisher, Simon & Schuster. When Lampton mailed in drafts, they came back with comments written in several colors. “There were other people, looking at your books, making comments. They're phantoms,” he says.

Book packagers are a kind of outsourced labor, not unlike factories in China or tech-support centers in Mumbai. They develop new story ideas, recruit and manage freelance writers, and edit the first drafts of series books. Then they deliver manuscripts to the publisher, who rewrite and polish them to produce the final book. “Hiring a book packager is a way of hiring staff without putting them on your payroll,” explains Anne Greenberg, who worked for Simon & Schuster from 1986 to 2002, when Lampton was writing. Greenberg edited hundreds of Nancy Drew mysteries after they came in from book packagers, and suspects she worked on more books in the series (approximately 300) than anyone else. “You have to keep feeding the machine,” she says.

Alice Leonhardt, who wrote Nancy Drew books for Megabooks, never even met the intermediaries who passed on her manuscripts to the publisher. “I have no idea where they were,” she says.