Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 423

June 2, 2015

The Paradigm Lag: Why It's (Still) Awkward to Talk About Caitlyn Jenner

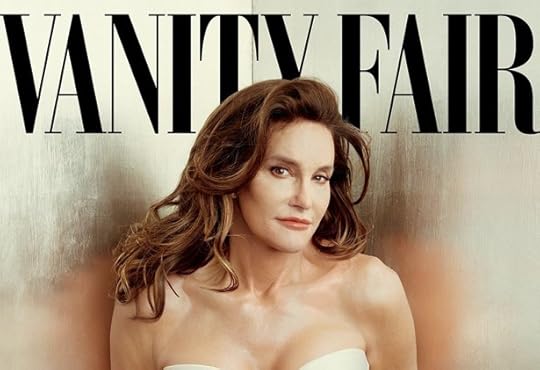

This week, Caitlyn Jenner made her debut on the cover of Vanity Fair. The reaction to this from the rest of the media was largely supportive. It was also, however, just a little bit awkward. The AP write-up of Jenner’s debut initially referred to Caitlyn as "Bruce" and as “he.” The Washington Post, in a similar vein, retracted a headline that referred to Jenner as “Bruce.” An analysis of the tweets about Jenner's Vanity Fair shoot announced that “people are generally using the correct gendered pronoun when mentioning Caitlyn’s official Twitter account,” finding that, in the first flurry of discussion, 1,179 tweeters used “she,” compared to 176 who used “he.” This was presented as good news—evidence, essentially, of the progress that’s been made when it comes to progress itself.

Which it was, sort of. Compare the response to Jenner's transformation to the reaction two years ago when Chelsea Manning’s attorney announced that Manning identified as a woman, and wished to be referred to with female pronouns. News organizations debated whether she should actually be referred to as “a woman” named “Chelsea,” and Manning ended up taking the matter to court, which ruled that she should be referred to, indeed, as a woman. What has been pretty much taken for granted in the conversation about Jenner is implied by the media reports’ quick corrections of their errors: the idea that Jenner herself should get to decide how she is identified by other people. The GLAAD guidelines that advise that one should “use the descriptive term preferred by the individual” have been adopted by mainstream news organizations. There’s a sense—as people struggle to show support using the right pronouns, the right adjectives, the right assumptions—that there are, in fact, correct terms to be used: “she,” not “he,” “woman,” not “man,” “Caitlyn,” not “Bruce.” These terms are correct because, as GLAAD says, they are preferred by the individual.

* * *

We live in a fast-moving culture. Memes rise and fall in the space of days, and often hours; new words become cliched almost as instantly as they’re formed. And in the same way that long-held assumptions about language (“his or her”) get abandoned in favor of other approaches (“their”), so do cultural institutions. Only a few years ago, same-sex marriage was a pipe dream; now, it's on its way to normalization. Marijuana, until recently the stuff of black-market subculture, is quickly developing into a full-blown industry.

Related Story

'Call Me Caitlyn': The Radical Simplicity of Vamity Fair's Cover

The shifts can feel, to those of us who are living within them, whiplashing. Cultural conventions haven’t yet caught up to cultural realities. Etiquette and language, the discursive products of quandaries that have been hashed out over time, can be slow to catch up with the fast-moving realities of the culture. And so, in an America that still often elides “sex” and “gender,” a bit of awkwardness when it comes to talking about Caitlyn Jenner is pretty much inevitable. The vocabulary is, to many people, unfamiliar. The lines between “transgender” and “transexual” are murky. People, generally, mean well; people are also, to a certain extent, confused. Culture is fast; convention is slow.

In Jenner’s case, what we're seeing, essentially, is a subculture—in this case, the trans community—becoming, gradually but also sort of suddenly, mainstream. The trans community, of course, already has set conventions and mores, precise words and phrases that are the product of dialogue and trial and error. The challenge is figuring out how those translate to the level of the mass culture, as paradigm shifts are shifting, suddenly, beneath our feet.

There’s something that happens in that shift, as convention catches up to culture. Call it a paradigm lag. It's the nebulousness that sets in, temporarily, as subcultures seep into the mass culture. It's the process of education and explanation that was on display, for example, in Jenner's recent interview with Diane Sawyer, which seemed aimed as much at educating the American public about transgenderism as it was about telling Jenner's particular story. It's the time required to figure out whether “transgender” or “transsexual” or “trans” is the appropriate adjective to describe a particular person. It's the learning curve of culture.

It’s the revealing imperative of the cover line of Jenner’s Vanity Fair issue: “Call Me Caitlyn.”

* * *

In Jenner's case, much of the language that will be used to describe her comes from a similarly imperative place: There are guidelines that exist; it is up to people simply to follow them. The murkier aspects of legislation, though, will likely take place in the form of questions about the lines between appreciation and objectification when it comes to someone in Caitlyn’s position. How should we talk about Caitlyn’s new appearance—which she has fought for, and which is so much a part of her identity—without objectifying her? How do we avoid the kind of casual misogyny that is so deeply ingrained in our conversations about women’s bodies?

Again, the AP's write-up is instructive: “Bruce Jenner,” the news wire initially announced, “made his debut as a transgender woman in a va-va-voom fashion in the July issue of Vanity Fair.” So was that analysis of gender pronouns used to describe Caitlyn, which pointed to tweets that called her “beautiful” and “gorgeous” and “the hottest Jenner.” These were meant to be supportive; their effect, though, was also to suggest that now that Jenner is a woman, she is fair game for the stuff that women deal with: an obsession with their looks, objectification, support about their behavior expressed as support of their appearance.

The balance, when it comes to questions about language and objectification and respect, is now for the culture to figure out, collectively.On the other hand, though, Caitlyn's transformation is specifically about the transformation of her physical form. In choosing Vanity Fair as the publication to announce that transformation, Jenner was also making a statement: Vanity Fair is glamorous. It will get the fashion just right, the lighting just so. It has a way of turning people into art. As my colleague Spencer Kornhaber pointed out, “a Vanity Fair cover story with Annie Leibovitz’s photos is at the same time an exercise in glamorization and humanization—making [Jenner’s] tale both more epic and more specific.”

The balance between the epic and the specific, when it comes to language and when it comes to deeper questions about objectification and respect, is now for the culture to figure out, collectively. And, if history is any guide, it will do that in fairly short order. The current awkwardness in the conversation about Caitlyn will subside; common language will emerge; norms will announce themselves. We’re just in a gray zone right now. We’re just catching up. As “Bruce,” Caitlyn Jenner was known for clearing hurdles. There's a moment, after the great leap is made, when the hurdler hovers in the air, detached from the track, seeming suspended over all that is solid. The ground, for that tense instant, is far away.

That's where we are right now: hovering, uncertain, suspended. But we’re moving forward, as quickly as we can. And soon, gravity being what it is, we'll land.

'A Profound Restructuring': The Resignation of FIFA Chief Sepp Blatter

Sepp Blatter, the four-term FIFA chief who weathered an unprecedented period of scandal and controversy in international soccer, announced on Tuesday that he would resign. His statement capped a furious few days of drama during which several FIFA officials and executives were indicted on mass corruption charges, conspiracy theories churned over the U.S. Justice Department’s involvement, and Blatter was nevertheless reelected FIFA chief by a wide margin.

“For the next four years I will be in command of this boat called FIFA, and we will bring it back,” he crowed triumphantly on Friday. “We will bring it back offshore, we will bring it back to the beach, where finally football will be played.”

But by Tuesday afternoon at a hastily organized press conference, Blatter’s tone had changed."This mandate does not seem to be supported by everybody in the world of football,” he said. “FIFA needs a profound restructuring."

It also needs a credibility boost. Last week, Justice Department officials accused FIFA officials of taking nearly $150 million in bribes over the course of the past 24 years. Swiss investigators also announced that they would open investigations into the bidding processes for the 2018 and 2022 World Cups, set to take place in Russia and Qatar, respectively.

In recent days, the reach of inquiry into the corruption has drawn closer and closer to Blatter, implicating a top deputy for transferring $10 million from FIFA accounts in 2008 to an account controlled by Jack Warner, a FIFA official who was indicted last week.

On Tuesday, the 79-year-old Blatter called for an immediate conference to select his successor and said that he would not stand for office again. Last week, Blatter had promised to stand down after his fifth term, but for reasons that still remain entirely unclear, he decided to resign instead.

One of the frontrunners to replace Blatter appears to be Prince Ali of Jordan, who finished second last week and signaled his interest to run again on Tuesday. Bookies have named Michel Platini, the head of the Union of European Football Associations, as the odds-on favorite to replace Blatter.

The TSA Doesn't Work—and Never Has

It’s customary among critics to deride the Transportation Security Administration as “security theater.” One has to wonder what kind of theater this is, though. A period drama, satirizing the 2000s? Vaudeville farce?

Witness the latest embarrassing lapses by airport screeners, as reported by ABC:

An internal investigation of the Transportation Security Administration revealed security failures at dozens of the nation’s busiest airports, where undercover investigators were able to smuggle mock explosives or banned weapons through checkpoints in 95 percent of trials, ABC News has learned. The series of tests were conducted by Homeland Security Red Teams who pose as passengers, setting out to beat the system.

In case the data don’t seem convincing, have an anecdote: In one case, a Red Team member strapped a fake bomb to his back. The screening machinery detected something amiss—so far, so good. But a patdown by an agent failed to detect the device, and the man passed through.

TSA’s failure to detect undercover agents might seem like familiar news, since it’s a part of a pattern. Reports about the TSA failing to find planted weapons and the like pop up every few years. In 2013, the GAO found that a nearly $900 million screening program didn’t work. In 2013, then-Administrator John Pistole was run through a congressional gauntlet over failures, but he insisted that the failures to catch members of Red Teams shouldn’t be viewed so negatively. After all, he reasoned, these were people who knew all of TSA’s internal protocols and were trying to test them—“super-terrorists,” he called them.

The problem with that rationale—leaving aside the presumption that real terrorists would also seek to learn and circumvent TSA protocols—is that non-super-terrorists seem to frequently bypass checks, too. In 2008, my colleague Jeffrey Goldberg wrote the kind of piece that would be hilarious if wasn’t terrifying, about traveling through checkpoints with fake boarding passes, no I.D., and ostentatious paraphernalia of terrorist organizations:

Because I have a fair amount of experience reporting on terrorists, and because terrorist groups produce large quantities of branded knickknacks, I’ve amassed an inspiring collection of al-Qaeda T-shirts, Islamic Jihad flags, Hezbollah videotapes, and inflatable Yasir Arafat dolls (really). All these things I’ve carried with me through airports across the country. I’ve also carried, at various times: pocketknives, matches from hotels in Beirut and Peshawar, dust masks, lengths of rope, cigarette lighters, nail clippers, eight-ounce tubes of toothpaste (in my front pocket), bottles of Fiji Water (which is foreign), and, of course, box cutters. I was selected for secondary screening four times—out of dozens of passages through security checkpoints—during this extended experiment. At one screening, I was relieved of a pair of nail clippers; during another, a can of shaving cream.

In this case, however, the secretary of Homeland Security has moved quickly to show that there is accountability. Secretary Jeh Johnson reassigned the administrator of TSA, Melvin Carraway, with a curt valediction: “I thank Melvin Carraway for his eleven years of service to TSA and his 36 years of public service to this Nation.” Except that Carraway wasn’t really the administrator—he was the acting administrator. The last permanent administrator, John Pistole, left on New Year’s Eve 2014, leaving the agency without a leader. It took the administration until the end of April to nominate a new administrator, in part because there was great concern to bring in someone who could get confirmed by the Senate.

See alsoPresident Obama finally nominated Peter V. Neffenger, the current vice commandant of the Coast Guard for the gig. Even then, Politico reports, he could face a difficult challenge, in part because while everyone seems to hate the screening process, members of Congress are especially frequent fliers and therefore are more acquainted with the miseries of air travel than most. (Jeh Johnson used his statement relieving Carraway of his duties to call on the Senate to confirm Neffenger.)

One way to think about this is as a grave threat to national security. The agency that’s in charge of addressing threats to America’s air travel is rudderless, and even the acting administrator has been kicked off the boat. Even worse, it comes as several provisions of the Patriot Act expire, which some argue endangers the nation’s security. (Others, needless to say, fiercely dispute that characterization.) On Tuesday morning alone, there were bomb threats against five U.S. flights, though officials didn’t believe they were credible.

Another way to think about it is, so what? TSA doesn’t ever seem to have been able to stop Red Team agents (or Atlantic correspondents) from bringing contraband through checkpoints. Meanwhile, American air travel has been largely free from attacks. The most notable recent case of an attempted attack on an airliner was Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab’s Christmas Day flight in 2009, and in that case the attacker boarded in Nigeria. Flying remains exceptionally safe, despite such high TSA failure rates. Like vaudeville theater, the screening process seems to exist largely to create a spectacle. Just don’t expect a soft shoe—you’ll have to remove those and put them on the belt, thank you.

A Human Disaster Near the World's Largest Dam

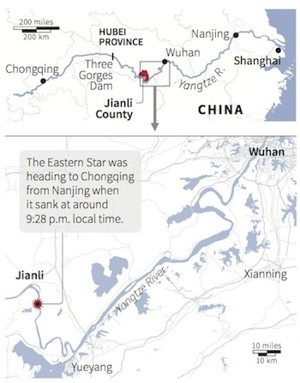

Rainy weather and low visibility disrupted Tuesday’s efforts to rescue hundreds of passengers from a four-story ship that capsized overnight on China’s Yangtze River. The Eastern Star was carrying over 450 passengers, the majority of whom were elderly tourists, when what Reuters described as a “freak tornado” struck the vessel.

As of Tuesday evening local time, a small number of both survivors and bodies had been located; however, The New York Times reported that rescue divers are searching for people who may be trapped in the hull of the ship with limited access to air. The paper also noted that Chinese Premier Li Keqiang had visited the site, “an indication of how seriously the ruling Communist Party regarded the accident.” The captain and the chief engineer have been detained.

Reuters

Reuters The ship was traveling on a 930-mile route from Nanjing, a city in eastern China, to Chongqing in the southwestern part of the country.

Along the way, the ship was due to pass the Three Gorges Dam, the world’s largest dam, which the BBC described as “a place of pilgrimage in its own right and a powerful symbol of China's rising economic might, attracting about two million visitors a year.”

In addition to being a token of Chinese ascension, the $24-billon dam has also been a symbol of the costs of China’s ambition.

The creation of the dam, which generates eight times the power of the Hoover Dam, displaced more than a million people and brought environmental problems like landslides and water pollution. In 2008, Scientific American noted that building “a massive hydropower dam in an area that is heavily populated, home to threatened animal and plant species, and crossed by geologic fault lines is a recipe for disaster.”

It also helped make the area a magnet for tourism, introducing the possibility of a different kind of disaster. As divers continued their search on Tuesday, the dam’s operators were instructed to reduce the flow of water in order to ease the rescue efforts.

Why Is It a Crime to Evade Government Scrutiny?

Dennis Hastert is a hard man to defend. The former House Speaker got filthy rich as a Washington, D.C. lobbyist by trading on the contacts and knowledge that he gained while in office. His time in Congressional leadership coincided with that body’s abject failure to exercise oversight or protect civil liberties after the September 11 terrorist attacks. And now he stands accused of a serious personal transgression: improper sexual contact with a boy he knew years ago while teaching high school and trying to hide that sordid history by paying the young man to keep quiet.

If federal prosecutors could meet the legal thresholds for charging and convicting Hastert of a sex crime, they would be fully justified in aggressively pursuing the matter.

Instead they’ve done something alarming. The Hastert indictment doesn’t charge him for, or even accuse him of, sexual misconduct. Rather, as Glenn Greenwald notes, “Hastert was indicted for two alleged felonies: 1) withdrawing cash from his bank accounts in amounts and patterns designed to hide the payments; and 2) lying to the FBI about the purpose of those withdrawals once they detected them and then inquired with him.”

It isn’t illegal to withdraw money from the bank, nor to compensate someone in recognition of past harms, nor to be the victim of a blackmail scheme. So why should it be a crime to hide those actions from the U.S. government? The alarming aspect of this case is the fact that an American is ultimately being prosecuted for the crime of evading federal government surveillance.

That has implications for all of us.

By way of background, financial institutions are required to report all transactions of $10,000 or more to the federal government. This is meant to make it harder to commit racketeering, tax fraud, drug crimes, and other serious offenses. Hastert began paying off the person he allegedly wronged years before by withdrawing large amounts of cash. But once he realized that this was generating activity reports, he allegedly started making more withdrawals, each one less than $10,000, to avoid drawing attention to the fact that he was paying someone for his silence.

Again, the payments weren’t illegal. But as it turns out, structuring financial transactions “to evade currency transaction reporting requirements” is a violation of federal law.

To see why that is unjust, it helps to set aside Hastert’s case and consider a more sympathetic figure. Imagine that a documentary filmmaker like Laura Poitras, whose films are critical of government surveillance, is doing her taxes next year. And she discovers that, having earned more freelance income than she anticipated in 2015, she must write the IRS a check for $9,000. Say that at the beginning of a typical month, she moves $3,000 from her savings to her checking account to cover basic expenses. But next April, anticipating her tax payment, she needs to move $12,000 between accounts. Vaguely knowing that a report to the federal government is generated for transactions of $10,000 or more, she thinks to herself, “What with my films criticizing NSA surveillance, I don’t want to invite any extra scrutiny—out of an abundance of caution, or maybe even paranoia, I’m gonna transfer $9,000 today and $3,000 tomorrow. The last thing I need is to give someone a pretext to hassle me over anything.”

That would be illegal, even though in this hypothetical she has committed no crime and is motivated, like many people, by a simple aversion to being monitored.

I don’t much like the $10,000 reporting requirement: as I see it, behavior that lots of people engage in every day for perfectly legal reasons shouldn’t trigger surveillance. And it is certainly perverse to set a threshold for government scrutiny, only to make it a criminal offense to purposely avoid triggering that threshold.

Think of applying the same logic in another context.

What if the government installed surveillance cameras on various streets in a municipality and then made it a crime to walk along a route that skirted those cameras?

Of course, Hastert may also have committed more serious offenses. The current charges could be motivated by a desire to prosecute him for sex crimes. But that dodges the issue.

“In order to punish him for that crime, the government should charge him with it, then prosecute him with due process and convict him in front of a jury of his peers,” Greenwald argues. “What over-criminalization does is allow the government to turn anyone it wants into a felon, and thus punish them without having to overcome those vital burdens. Regardless of one’s views of Hastert or his alleged misconduct here, it should take little effort to see why nobody should want that.”

If the state can decide that specific, legal behavior will trigger scrutiny by federal law enforcement and that any attempt to avoid that scrutiny is illegal, even if no other crime is proved, everyone’s privacy and freedom from unjust arrest is undermined.

Jamie xx's In Colour Transcends the Past

In a world of superhero TV shows connected with superhero movies connected with superhero comics, Tarantino films about films about films, and pop hits that set legal precedent as they imitate the “feel” of classics, “recycled” is no longer an epithet of any meaning when applied to art. Some cultural works mine the past for the cynical purpose of not having to make anything original, and some do it for the clever purpose of using what’s come before to create something that’s actually new. But the mere fact of having reused something, it would seem, is value neutral: A work of art is neither good nor bad merely because it looks back.

Related Story

You have to keep this in mind when reading about music these days, and especially when evaluating the acclaim surrounding Jamie xx’s new album, In Colour. A lovely New Yorker essay last month by Hua Hsu pointed to the 1999 experimental film Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore as a decoder for the work of Jamie Smith, who’s half of the successful indie-rock act The xx and who’s worked on songs for Drake, Rihanna, and Gil Scott Heron. That film itself was a pastiche of footage from three decades of nightclub dancing, from 70s discoteques to 90s warehouse raves, and its woozy, nocturnal score captures something about the emotions of dance culture rather than imitating the actual sound of it. Like that film, Smith’s music looks back at dance heydays from before his time without aping them.

I’m not well acquainted with UK rave history, and reading Hsu’s piece after spending some time within In Colour was a bit of a revelation. The synthesizer that beams through the spookily gorgeous opener “Gosh,” it turns out, “recalls the melody of the 1991 rave anthem ‘Belfast,’ by Orbital” and the vocal sample that gives that song its title comes from an unaired BBC radio show about underground dance music. The rest of the album is peppered with similar references. Hsu calls In Colour Smith’s “homage to club culture—or a version of it that you might imagine if you’ve arrived a few years late, after the pirate radio stations have been shuttered and the legendary after-hours spot has been converted into condos.”

Is it essential to know all of this context, listening to the album? Certainly, the primer helps explain why Jaime xx’s music sounds the way it does. The songs are largely instrumental collages that seem somewhat decayed, with breakbeats making a muffled clamor like animals rummaging through abandoned houses. But without being aware of the nostalgic ethos behind the music, you can still get the gist of a track like “Sleep Sound,” which has chopped-up doo wop song, a snippet of a woman lazily saying “yeah,” and a churning bass line that’s often left unaccompanied. It evokes what it’s like to be tossing and turning as the neighbors party loudly, and I’ve found myself humming the melody that emerges from the din.

Similarly, it takes no foreknowledge to be enraptured by a track like “The Rest Is Noise,” an expanding-and-contracting swirl of electronic distortion, handclaps, waterfalling piano, and chiming noises. Nor do you need to study up to sway along to “I Know There’s Gonna Be (Good Times),” a potential summer hit featuring rapper Young Thug and dancehall singer Popcaan over lackadaisical finger snaps and a sample of the Persuasions that a Persuasions singer apparently forgot he OKed. Some of the songs make far less of an impression, even after multiple listens and some reading around about what’s being sampled. A good text is a good text, and a bad text is a bad text; referentiality might deepen one’s appreciation, but it can’t account for it.

In fact, perhaps the most thrilling thing about the album is how alien it can seem when completely divorced from its source material. “Gosh” rides a beat that sounds like a tennis-ball machine firing at a squeaky toy; the “oh my gosh!” sample could come from a Vine or a medieval TV show or be an original recording—there’s fun in not knowing. And the much-discussed keyboard that enters towards the end seems so out of place and yet is so viscerally affecting that it’s nice to imagine its inclusion resulted from a mistake.

The other bit of outside knowledge that can shape one’s understanding of the album concerns Smith’s original band, The xx. Smith and singer Romy Madley-Croft are responsible for some of the most devastating relationship songs of the past decade, and when Madley-Croft shows up on a few songs here’s it’s a cue to tune in to a slightly different emotional frequency, one where lyrics suddenly matter. With a keyboard pattern that whirs like a malfunctioning control panel and a hip-hop beat that fades in and out, the music in “Seesaw” dramatizes Romy’s simple, sighed mantra: “I’m on a seesaw, up and down with you.” And on album highlight “Loud Places,” she sings about going out at night to try and replace a lover who’s left her, before multi-tracked male voices back her up: “I have never reached such heights.” Even if you don’t realize those voices come from a song released 38 years ago, the sentiment expressed feels eternal.

To Write a Great Essay, Think and Care Deeply

Doug McLean

Doug McLean Every memoirist, at least implicitly, advances a fraught claim: My life makes a good story. But Lucas Mann—like most nonfiction writers—isn’t always so sure. When he struggles with self-doubt, questioning the literary value of his own, lived experience, Mann turns to J. R. Ackerley’s My Dog Tulip, an unabashed, lyric tribute to a well-loved German Shepherd. In his essay for this series, Mann celebrates Ackerley’s ability to make anything compelling—even the discreditable genre of pet lit—demonstrating how honesty and specificity have the power to redeem the banal, imbuing our smallest private moments with significance.

Related Story

Writing Is the Process of Abandoning the Familiar

In Lord Fear, his second book, Mann takes on his brother, Josh, who was two decades older, handsome, talented, and helplessly addicted to drugs. Josh died of a heroin overdose when Mann was just 13, leaving behind big, unfulfilled ambitions and scads of self-castigating notebooks. (In sternly worded lists with headings like “Rules!!,” Josh details the things he hopes he will no longer do—take drugs at work, at the Met, before noon, after 9 p.m., etc.). As Mann tries to learn more about a sibling he loved and lost, he grapples with the fact that his portrait can never be objective or complete; the book explores the imperfect nature of our recollections, the way cherished memories tend to blend with myth.

Mann attended the University of Iowa Nonfiction Writing Program. His first book, Class A: Baseball in the Middle of Everywhere, profiled a minor-league farm team, the Clinton LumberKings. He teaches writing at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, and lives in Providence, Rhode Island.

Lucas Mann: When I first encountered J.R. Ackerley’s My Dog Tulip, I was in a particularly angsty phase of my graduate-school career. I got my M.F.A. in nonfiction writing, a tiny, separatist sect within the already over-specialized community of literary academia. When anyone asked what I was working on, I couldn’t simply answer “my novel,” and be done with it. This might seem to be a very minor concern, and it is—still, I winced each time someone found out my chosen genre and asked me, with a sneer, “Oh, so what horrible event brought you here?” Again and again, the type of work I aspired to was met by outsiders with either confusion or derision, and that pattern only served to create within me a heightened sense of panic and defensiveness every time I sat down to write. It felt as though the gnawing question that plagues every fledgling writer was extra-magnified for those of us writing essays; it extended beyond What makes you think that you have something interesting to say? into, What makes you think you could possibly have something interesting to say about the petty circumstances of your own life and interests?

As a general guideline, I don’t think this is a bad line of inquiry—ultimately, all writers should put that pressure on their work. But as I wrote about baseball and about my family, two topics that can easily verge into the maudlin or the insular, I faced more than literary self-doubt—I exhausted myself questioning whether the things I cared about were worth care in the first place. Enter My Dog Tulip, a book-length essay dedicated entirely to a poorly behaved German Shepherd that Ackerley cared for more deeply than anything else in his life. (So much, in fact, that he changed her name for the book, as though protecting her from the attention, a detail that still gives me a ton of joy. Her real name was Queenie.) I’d just finished Ackerley’s investigative family memoir, My Father and Myself, which had really resonated with me, and I wanted to read more of him. Still, I came to Tulip with some skepticism. After all, dog writing is … a challenge, to put it gently, something most commonly found alongside tributes to dead grandparents in the personal statements of unsuccessful college applicants. I can’t bring myself to write about my own beloved dog, because I imagine a reader reacting the way I do when a celebrity goes on a talk show and tells a story about their kids as though no other child has ever existed.

As I wrote about baseball and about my family, I exhausted myself questioning whether the things I cared about were worth care in the first place.But Ackerley, amazingly, seems immune to shame. He spends no energy on the page justifying why Tulip is a worthy literary subject. Instead, he focuses on detail. Every detail. The book features a chapter called “Liquids and Solids,” which is about exactly what you think it’s about, beginning with a quote on a particularly satisfying [bowel movement] of Napoleon’s and then moving into careful descriptions of Tulip in the act: “A mild, meditative look settles on her face.” As the book moves forward, the specificity only increases. At first, the reader is suspended in a sort of purgatory of literary expectation. Something has to happen soon, we reason. The plot will kick in or the larger purpose of the book will reveal itself. But the plot is only that Tulip is alive, and the larger purpose is only Ackerley attempting to support and record that life. Somehow, though, we begin to feel a subtle yet undeniably forceful momentum. It’s as though we’re building to a critical mass of the mundane. I notice this, he tells us. And I notice this, and this and this. When Tulip wakes up, I watch her. When she goes to the bathroom, I watch her. When she falls asleep, falls ill, gives birth, I watch her.

My favorite passage comes at the very end of the book. Every time I return to it, it has the same goosebump effect on me, even though I know what’s coming — Ackerley had been building to a crescendo without me even noticing it. After 170 pages, he tweaks the register he’s working in. I feel him open up the throttle and finally, after so much careful observation and notation, the emotion begins flowing freely out of his descriptions. There are a few more paragraphs after this one (I’m leaving them out because I don’t want to spoil it), but this is the moment where my heart begins to quicken as I read.

The passage begins quite simply; Ackerley is walking Tulip in the park. The sentences are very intentionally matter-of-fact, at first: “It is winter. It is her thirteenth day. It was on her thirteenth day that she was fertilized, three years ago.” This is almost cartoonishly deadpan, a doctor reading a chart. Ackerley is reaffirming for us just how dedicated he is to every detail. But look how quickly he turns from the matter-of-fact to the operatic, as he shows us how much he worries for her:

I pick up the broken glass that is everywhere to be found and upon which Tulip sometimes cuts her feet. I pick it up throughout the year whenever I notice it, but it is only now when the high summer seas of bracken have sunk to a low brown froth that I can see it where I fear it most, at their roots. Here, where she was so lately pouncing … The scattered fragments of broken bottles are bad enough—so sharp that, cautiously though I gather them, I often prick my fingers—but in their midst I sometimes find the butt-end still planted upright in the turf where boys stuck it, the other day or years ago, as target for their stones. Its splintered sides stand up like spears. I gaze at Tulip's slender, long-toed feet in dismay. The little knuckly bones that curve over the four front pads are more delicate than a bird's claw. And the pads themselves: I used to suppose them made of some tough, resistant, durable substance, such as rubber or gutta-percha; but they are sponges of blood. The tiniest thorn can pierce them, a sharp edge of glass, trodden on merely at walking pace, can slice them open like grapes. How they bleed! And what age they take, by slow granulation, to heal! Together they fit, indeed, to form a kind of quilted cushion; but dogs spread their toes for pouncing, and in between is only soft furry flesh and all the vital tendons of the leg. One pounce upon this bottle, with both front feet perhaps ... I pick it up. I pick it all up, every tiny fragment. I seek it out, I root it up, this lurking threat to our security, our happiness, in the heart of the wood; day after day I uncover it and root it up, this disease in the heart of life.

Shards of broken glass, the kind found in every public park in every city in the world, become spears; overgrown grass that hides the spears becomes the high summer seas of bracken, and when the grass recedes we’re left with a low, brown froth where the spears lurk. Every word is ominous. The details of the setting loom larger and larger, not because they grow but because Ackerley creates the opposite effect. We feel him leaning closer, looking so carefully, and it’s the closeness in his gaze, his dedication to looking, that transforms the subject.

Tulip’s paws are sponges of blood, he realizes. What a phrase. It is, on the one hand, simply put and true. But it also takes on such weight. Tulip is so full of life, she is life, and yet the blood can be drained so quickly, from one prick or squeeze. How they bleed! Ackerley writes of her paws, and we feel every bit of the emotion behind these words, the tiny trauma that occurs whenever he sees the dog he loves in pain. So much narrative power is derived from this simple series of observations: There is glass everywhere; Tulip is fragile enough to be cut by glass; Ackerley remembers how it looks when she gets cut. There is both story and back story pulsing through this moment, and there’s suspense, too, as he wonders on each new walk whether he’ll fail to protect her and she’ll get cut again.

Life is small. Our routines are rote and nearly imperceptible. Often, in writing classrooms, we’re told that it’s this smallness that makes a piece of literature. There are a million quotes to this affect adorning a million white boards in every school in America: Most of our lives are basically mundane and dull, and it’s up to the writer to find ways to make them interesting (that’s Updike). Or, Life is not plot; it’s in the details (that’s Jodi Picoult). I could go on. Usually, though, this sentiment ends up seeming as hollow and insincere as write what you know. Because we do cherish plot, we do fetishize the arc, the action, the twist. In nonfiction, we also fetishize the aboutness. We openly question if the reality of a writer’s subject is worth discussing. We prioritize a weighty topic over the force of an author’s gaze, the clarity of her prose, the sincerity of her emotion. Underneath it all runs that same droning question that plagued me as a student, and still does sometimes: Who cares? Who cares? Who cares?

That’s all a great essay is: a virtuoso performance of care.Ackerley answers this simply: I do. And he goes on to give us a virtuoso performance of care. I think I keep returning to this passage, and the book as a whole, because it’s important for me to remind myself sometimes that, at its heart, that’s all a great essay is: a virtuoso performance of care. Sure, Ackerly is not the only writer who seems to intuit this. There are many wonderful and far more canonical examples of this quality that I can turn to: Virginia Woolf really cared about that poor moth, and Didion really cared about her notebook, and Montaigne really cared about, well, everything. But Woolf’s moth was a metaphor, an animal being used very overtly to get at larger themes within Woolf herself. And Didion’s style is always as much of her passion as her subject (as well it should be). And Montaigne is constantly pushing out into the grandiose; whatever topic any of his essays is originally “on” quickly gets left behind. I read Ackerley because his care for his subject is ever-focused, non-metaphorical, pure. He understands the narrative power of a writer’s concentrated gaze, and he never wavers. So we see Tulip’s “little knuckly bones” and the “slow granulation” of her healing wounds, details that mean so much because he bothers to notice them.

I know there’s some danger in celebrating a writer’s blind fidelity to his own interests. It can smack of over-supportiveness—kumbaya, all essays are special snowflakes, etc, etc. But that’s not the sense that reading My Dog Tulip gave me. It didn’t absolve me from hard, self-critical work. Instead, it woke me up to the fact that spending one’s time fretting about aboutness is a deflection from the essayist’s real challenge: to think and feel as deeply and specifically as possible about whatever it is you’re looking at. Tulip reminds me that the subject of an essay does not need to prove itself worthy of the writer or reader’s care, but rather that the force of the care in the writing should be able to render any subject worthy. J.R. Ackerley had a dog and he watched her live her life and he cared about every detail of that life while knowing that someday it would end. What could be a worthier subject than that?

Does a True Threat Require a Guilty Mind?

“Given our disposition, it is not necessary to consider any First Amendment issues.”

Not since “For God, for country, and for Yale!” have so few words conveyed so bitter an anticlimax. They were written for the United States Supreme Court by Chief Justice John G. Roberts. He was writing for seven justices in Elonis v. United States, the “Facebook threats” case.

Many commentators (including me) had suggested that Elonis might be an important case about the First Amendment and rap music, or about the rules for threatening and abusive language on social media.

Not so much. In fact, the case discusses only the basic issue of “mental state”—the staple of first-year criminal-law classes. Every One L knows that crime requires a “guilty mind.” In our system, we don’t convict people who don’t know what they’re doing. They don’t have to know it’s against the law; but most criminal statutes specify some mental state that must be proved. Does the defendant only have to know what actions he or she is committing (general intent)? Must the defendant be reckless—that is, know that there’s a substantial risk that actions will do harm, and disregard it? Or does the crime require specific intent—that the jury must find beyond a reasonable doubt that this defendant wanted and understood that the that the actions would cause harm?

Related Story

When Does the First Amendment Protect Threats?

Elonis required the Court to decide what sort of “guilty mind” is necessary to violate a federal criminal statute, 18 U.S.C. Section 875(c). The law forbids using “interstate communications” to transmit a “threat to injure the person of another.” It doesn’t specify any “mental state” at all. Courts have wrestled with its language for years.

The lower court held that Elonis himself only needed to know the meaning of the words he wrote; if “a reasonable person” would “foresee” that the words would be read as a threat, he could be convicted. As the prosecutor told the jury, “it doesn’t matter what he thinks.”

In Monday’s decision, seven justices firmly said that “general intent” is not enough. Okay, then, is the answer recklessness or intent?

Yes, Roberts wrote.

Well, which? The chief justice wasn’t saying.

Anthony Elonis was a theme-park worker in Pennsylvania. In 2010, his wife left him, taking their two children. Soon after, he was fired from his job. He began posting on Facebook that he was thinking of killing his wife. Here’s a sample:

There’s one way to love you but a thousand ways to kill you. I’m not going to rest until your body is a mess, soaked in blood and dying from all the little cuts. Hurry up and die, bitch, so I can bust this nut all over your corpse from atop your shallow grave.

His wife, terrified, got a restraining order—in response to which he posted, “fold up your [order] and put it in your pocket./Is it thick enough to stop a bullet?” Meanwhile he posted similar words (and some pictures) about his former co-workers, children at nearby elementary schools, and a federal agent.

Elonis was posting under the “rap” name “Tone Dougie,” and claimed that his words were just artistic expression and emotional therapy. He argued that the First Amendment required proof of a “subjective intention” to convey a threat. The trial court and the Third Circuit Court of Appeals rejected that: General intent was enough. The Supreme Court Monday simply reversed the court of appeals. You guys figure out the right “mental state,” it said, and we will let you know later if you got it right.

The Court has repeatedly said that the First Amendment does not protect “true threats.” That phrase does not mean that the defendant can and will do what he threatens to do; it simply means that the words really mean what they say—“I intend to hurt you.” Two kids phoning in a bomb threat are making a “true threat”; a Vietnam-era anti-draft speaker warning that “If they ever make me carry a rifle the first man I want to get in my sights is L.B.J.” was not.

So—was “Tone Dougie’s” page a “true threat”? Elonis could be, and almost certainly should be, convicted under any standard. He knew he was terrifying his wife—a court had told him so and ordered him to stop. He posted that he intended to carry out “the most heinous school shooting ever imagined”; when two federal agents visited him after the school threat, Tone Dougie warned them that if they came again he would blow them up with a suicide vest.

To prove that Elonis had a “guilty mind,” the prosecution—even under the demanding intent standard—would not have to x-ray his skull, or find words saying, “I intend to cause fear.” As in any other criminal case, they’d only have to show that what he said, what he did, and the circumstances make it almost impossible to deny that he must have intended to scare somebody. That’s how the criminal law reads the mind of man, and Elonis’s doesn’t seem terribly opaque.

When he was confirmed as chief justice, Roberts told the Senate Judiciary Committee that he aimed at a Court that was less divided and more modest. Fewer dissents, more unanimous decisions. He is proving—in some areas at least—true to his words. It may be that Monday’s decision attracted seven votes precisely because it decided so little.

There was one additional vote to reverse—Justice Samuel Alito, who wrote that “[t]he Court’s disposition of this case is certain to cause confusion and serious problems.” Most of Alito’s opinion is a careful roadmap for the Third Circuit, explaining that it should decide that recklessness is the correct standard. Justice Clarence Thomas dissented—not because he thought Elonis’s speech was protected, but because he believed that a “general intent” standard was good enough. Quoting a 2000 case, he said, the proper standard was that “‘the defendant [must] know the facts that make his conduct illegal’—but he need not know that those facts make his conduct illegal.”

Elonis is, then, a disappointment, declining to reveal what the Court really thinks. Half a millennium ago, Chief Justice Thomas Bryan of Britain’s Court of Common Pleas, in exasperation, wrote that “[t]he thought of man is not triable, for the devil himself knoweth the mind of man.” If we could summon him from that grim shade into which pass heroes of the common law, I suspect that he would confess that in this particular case, neither he nor the devil could know the mind of Chief Justice John G. Roberts.

June 1, 2015

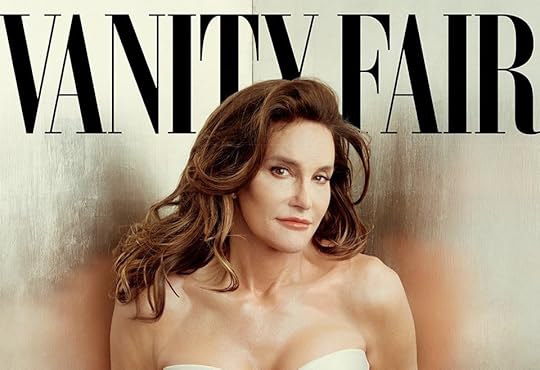

'Call Me Caitlyn': The Radical Simplicity of Vanity Fair's Cover

At first, you might not recognize the woman on the cover of the new Vanity Fair. I didn’t, for a second. The text certainly isn’t helpful—just one line, “Call me Caitlyn.” Who is Caitlyn? Then you really look at the face and realize it’s the person who the public has known as Bruce Jenner, the Olympic medalist and Kardashian patriarch who recently came out as a woman.

This process of recognition is, of course, part of the point. Jenner is, for the first time in public, dressing herself in women’s clothes and going by a woman’s name. The explanation for why is inside Buzz Bissinger’s long profile of her, but the simplicity of the cover says that you aren’t owed an explanation. Many transgender people have spoken about the desire to be seen for who they are, not who they used to be. I always think about the lyrics to the title track on Transgender Dysphoria Blues, the first album that Against Me! put out after singer Thomas James Gabel became Laura Jane Grace: “You want them to notice the ragged ends of your summer dress. You want them to see you like they see every other girl.”

Related Story

The Bruce Jenner Learning Curve

For Jenner in particular, this is a difficult goal: Bruce was a celebrity for a long time, one who’s become only more famous since announcing herself a woman in an interview with Diane Sawyer on 20/20. Like the reality-TV universe that so many people know her from, a Vanity Fair cover story with Annie Leibovitz’s photos is at the same time an exercise in glamorization and humanization—making her tale both more epic and more specific. Some people are complaining that she’s creating a spectacle, but it’s hard to see how it could be any other way, nor why that’s inherently a bad thing given the circumstances.

As a cast member on a hugely popular TV show, Jenner faced a few options when trying to face her inner torment. One was to do nothing, a notion that Jenner dispatches when telling Bissinger, “If I was lying on my deathbed and I had kept this secret and never ever did anything about it, I would be lying there saying, ‘You just blew your entire life.’” Another was to try and hide it as if it were a shameful secret rather than just who she was. And the third option was to treat it as the media event it would inevitably be. In doing so, she immediately became a sociopolitical figure, informing many people about a minority struggle they may not have ever tried to understand before. Jenner’s oldest four children believe, in Bissinger’s words, that she may end up being “the most socially influential athlete since Muhammad Ali."

Jenner’s oldest four children believe that she may end up being “the most socially influential athlete since Muhammad Ali.”Those children, though—Brody, Casey, Burt, and Brandon, all born before Jenner married his third wife, Kris—do not want to participate in her reality-TV show. They support Jenner’s transition, but Bissinger documents the discomfort they have with the manner in which she has announced it, objecting especially to the fact that Jenner’s E! program will be produced by the same people behind Keeping Up With the Kardashians. Brandon Jenner, 33, fears it could be a “circus”: “They're gonna make a show about the Jenners versus the Kardashians," he says, and it’s hard to miss the fact that Bissinger’s story comes close to doing the same. E!’s head of programming, Jeff Olde, replies by saying, “We will not resort to spectacle ... We understand the power and responsibility to be able to share this story.”

The story really is extraordinary; Bissinger writes that it’s the most remarkable thing he’s ever worked on as a journalist. Some of the details are heartbreaking. As a gold medalist touring the country giving motivational speeches in the 70s, Jenner wore panty hose and a bra under a suit; Jenner’s second wife expressed sympathy but says they broke up because “I married a man”; Jenner underwent some medical procedures to look more feminine in the late 80s, before giving up on the process for several decades. Many personal relationships have been strained—Jenner’s adult children’s contend that their father was too-often absent—and it’s impossible to know how much gender identity played a role.

There’s no doubt that Jenner’s public persona, the politics around transgender people, and the delicate familial dynamics involved will be affected by the cover and the story. It’s important to remember, however, that those will be side effects, and that Jenner’s decision was made despite all these considerations, not because of them. “I'm not doing this to be interesting,” Jenner told Bissinger. “I'm doing this to live.” During the short video accompanying the Leibovitz photos, Jenner talks about how her old life was filled with lies. No more, she hopes. “As soon as the Vanity Fair cover comes out, I'm free.”

The FIFA Scandal Enters Its Conspiracy-Theory Phase

Perhaps no human endeavor inspires the turning of more conspiratorial gears than professional sports. From Michael Jordan’s eyebrow-raising first retirement to Sonny Liston’s suspicious fall against Muhammed Ali to Curt Schilling’s bloody sock, the quest to identify corrupting forces is a sport unto itself.

Of course, when it comes to the world’s most popular game, the Internet is practically one enormous smoke-filled room. Last week’s arrest of several FIFA officials and executives, which preceded the surreally tidy re-election of FIFA head Sepp Blatter, appeared to be unimpeachable proof of true sports wickedness—corruption, graft, shadowy dealings, thrown bidding processes—the very salt and meat of evil connivances.

What could trump this kind of malfeasance? According to the anti-American conspiracy theorists, the indictments themselves are the real scandal. Russia was among the first to cry foul. “We know the pressure that was exerted on [Blatter] with the aim of banning the 2018 World Cup in Russia,"said Russian President Vladimir Putin, who blamed the United States for “persecuting” the FIFA chief.

On Sunday, Blatter’s daughter Corrine chimed in to call out the “dark forces” responsible for the plot against her father. "I wouldn't say from the Americans and the British, but certainly people working behind the scenes, yes absolutely,” she said.

Then there were the remarks of Jack Warner, a former FIFA executive, who released a video to protest the corruption charges against him. In it, he said American actions against FIFA were simple revenge for the U.S. loss of its bid to host the 2022 World Cup. “The U.S. applied to hold the World Cup in 2022 and they lost the bid to Qatar —a small country, an Arabic country, a Muslim country,” said Warner in the video.

More notably, Warner actually held up a printed out copy of an article from The Onion, which claimed (satirically) that a separate World Cup tournament was already underway in the United States, organized by FIFA to get the Americans off its back. The article concluded thus:

At press time, the U.S. national team was leading defending champions Germany in the World Cup’s opening match after being awarded 12 penalties in the game’s first three minutes.

Warner deleted and reposted an edited version of the video later without the article in it, but the desperate seizing upon of farce didn’t start and end with The Onion.

On Sunday, as The Moscow Times reported, the Russian state newspaper Rossiiskaya Gazeta responded to a satirical blog post by The New Yorker’s Andy Borowitz. In it, Borowitz had written that Senator John McCain had called for military action against FIFA: “‘These are people who only understand one thing: force. … We must make FIFA taste the vengeful might and fury of the United States military.’”

Rossiiskaya Gazeta’s Vladislav Vorobyov cited the fake quotes as proof of American willingness to bomb “any place on the planet.”

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower