Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 428

May 23, 2015

Will Congress Let the Spying Stop?

On June 1, the spying stops.

Not all of it, of course, but after the stroke of midnight on that Monday morning the National Security Agency must halt some of the spying programs it launched in the months and years after September 11, 2001. And not because it wants to, either, but because several key provisions of the Patriot Act will expire without congressional action, and lawmakers can’t agree on how much of the surveillance state to keep in place. (June 1 is, of course, still more than a week away, but much like the objects in car mirrors, deadlines in Congress are usually closer than they appear.)

The House last week voted overwhelmingly to approve legislation to reauthorize the Patriot Act while ending the NSA’s bulk collection of telephone metadata and instituting reforms aimed at making the secretive agency more transparent. With its business completed, the House left the Capitol for a Memorial Day recess, with no plans to return before the afternoon of June 1st—hours after the deadline.

Related Story

A Long-Awaited Reform to the Patriot Act

The Senate, however, remains bitterly divided on the issue. A majority of senators support the House bill, dubbed the USA Freedom Act, but one of its staunchest opponents is the man in charge, Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. He believes the Patriot Act should be extended without changes, even though most senators are adamantly opposed to a clean reauthorization. McConnell allowed the House bill to come up for a vote shortly after midnight Saturday, but it fell three votes shy of the 60 it needed to overcome a filibuster. GOP national-security hawks like Lindsey Graham and Richard Burr oppose it, and enough Republicans stuck with McConnell to prevent the Senate from getting steamrolled by the House.

McConnell’s own bid to pass a two-month extension to buy time to negotiate a compromise also fell short, and senators wouldn’t allow him even to approve an extension of 24 hours. Because the House had already skipped town, it might have been a moot point, and it probably wouldn’t prevent a temporary spying slow-down at the NSA. “You can’t extend something that is dead,” declared Senator Patrick Leahy, the Vermont Democrat, in a floor speech Friday. With McConnell backed into a corner, lawmakers like Democrat Ron Wyden of Oregon and Republican Dean Heller of Nevada say they won’t support anything except the Freedom Act—not even the shortest of time-buying Patriot Act extensions. Burr, who heads the Senate’s Intelligence Committee, tried to break the impasse on Friday by proposing legislation that mirrored the House bill but provided a longer transition for the NSA to end its bulk collection program. It also sought to address concerns that the telephone companies wouldn’t retain data they would be newly charged with collecting in place of the government.

“After May 22, 2015, it will be increasingly difficult for the government to avoid a lapse in the current NSA program of at least some duration,” the memo said.And then there’s Rand Paul, the presidential hopeful who delivered a 10-hour speech-but-not-a-filibuster on Wednesday to protest a reauthorization of the Patriot Act, which he called “the most unpatriotic of acts.” Paul also opposes the House’s Freedom Act on the grounds that it doesn’t go far enough to curb surveillance. On this point he joins other privacy advocates who point out that the NSA would still be able to access metadata from phone companies and are concerned that the proposal contains too many legal loopholes. Early Saturday he made a point of objecting to any extension of the Patriot Act unless McConnell committed to having a broader debate on the merits of the spying programs.

So the Senate is essentially stuck, and the Obama administration, which supports the Freedom Act, isn’t offering much help. Ratcheting up pressure on McConnell, the Justice Department sent a memo to Congress warning lawmakers that even if they delay action until the weekend, they may be too late to avoid an interruption in surveillance—the programs can’t just be turned off like a light switch. “After May 22, 2015, it will be increasingly difficult for the government to avoid a lapse in the current NSA program of at least some duration,” the memo said. McConnell announced that the Senate would return to session on Sunday, May 31—just hours before the deadline—to figure out what to do.

What this all means for the security of the nation remains unclear. Privacy advocates believe the country would be better off if the entire Patriot Act was left to expire, while supporters of the surveillance programs argue that any interruption would put American lives in danger. “The intelligence community needs these tools to protect Americans,” McConnell said on the Senate floor on Friday. Come June 1, the country could find out if he’s right.

May 22, 2015

All Unhappy Families: The Downfall of the Duggars

On Thursday, news broke that Josh Duggar, the oldest son of the Duggar family's 19 children, had, as a teenager, allegedly molested five underage girls. Four of them, allegedly, were his sisters.

The information came to light because, in 2006—two years before 17 Kids and Counting first aired on TLC, and thus two years before the Duggars became reality-TV celebrities—the family recorded an appearance on The Oprah Winfrey Show. Before the taping, an anonymous source sent an email to Harpo warning the production company Josh’s alleged molestation. Harpo forwarded the email to authorities, triggering a police investigation (the Oprah appearance never aired). The news was reported this week by In Touch Weekly—after the magazine filed a Freedom of Information Act request to see the police report on the case—and then confirmed by the Duggars in a statement posted on Facebook.

The Duggars, Jim Bob and Michelle, knew what Josh had done; prior to the Harpo incident, however, they had handled the matter privately. But that their sad secret would be revealed because the family did an interview with Oprah seems, in retrospect, appropriate. All reality TV—and reality TV about families, in particular—revels in the systemic collision of intimacy and publicity, the none-of-your-business and the everybody’s-business. All famous families are alike; all famous families are unhappy in their own way.

Related Story

The Warrior Wives of Evangelical Christianity

But the Duggars, whose recent additions to their family have made them, now, the stars of 19 Kids and Counting, also represent a unique strain of reality TV stars. They are, on the one hand, like the Thompsons and the Kardashians and the hair-gelled kids from Jersey Shore: They consider what it means to be a family. These shows, which celebrate and denigrate their stars in pretty much equal measure, would be painfully unwatchable if it weren't for that. And 19 Kids presents a particularly charming answer to the question of family-hood. It offers up a (very large) group of people who enjoy each other, who tease each other, who laugh with each other—who seem to like as well as love each other.

The difference between the Duggars and their fellow reality-TV families, though, has been that the Kardashians and the Thompsons and their fellow families don't claim moral superiority over their viewers. They claim, instead, a moral distance from those viewers. The Kardashians, in some ways the polar opposites of the Duggars, revel in their uniqueness, in their marginality, in the collection of idiosyncrasies that got them their own reality show(s) in the first place. The Kardashians have no interest in making people want to be like them. They have an interest, instead, in making people want to be not at all like them. They have an interest in inspiring fascination rather than emulation. Their weirdness is their capital, and their currency.

Not so the Duggars, who use their fame—their TV show(s), their book(s), their various political appearances—as platforms for evangelism. And evangelism not just for a religion, but for something more basic: a lifestyle. A lifestyle that is so inflected with moral messaging that we might as well call it A Way of Life. The Duggar children are home-schooled. Michelle Duggar, who recently recorded a robocall arguing against protections for LGBT and transgender residents of Fayetteville, Arkansas, doesn't allow her daughters to wear shorts or skirts with hems that fall above the knee because an exposed thigh, she has explained, amounts to "nakedness and shame." The girls generally avoid beaches and swimming pools under the same logic. Jessa Duggar (whose recent wedding TLC treated as a Very Special Event, dedicating multiple episodes to it) married her fiancé not just having never had sex with him, but having never kissed him.

19 Kids and Counting doubles as an extended informercial for “family values” as the Duggars define them.“We really do know that this isn't for everyone,” Michelle admits in a blog she writes for TLC. Still, the overall effect of the show and the books and the overall omnipresence of the Duggars is promotional—and promotional, in particular, of a way of life that rejects the norms of the mass culture in favor a kind of moral libertarianism. 19 Kids and Counting doubles as an extended infomercial for “family values” as the Duggars define them. (Though many have associated them with the Quiverfull movement, they claim that they “are simply Bible-believing Christians who desire to follow God's Word and apply it to our lives.”) And the show, being what it is, spreads the messaging beyond television alone. On TLC's website, the older Duggar children keep "life books": virtual scrapbooks "where you can immerse yourself in the milestone events of Duggar family members who’ve recently had memorable life moments—courtship, marriage, pregnancy, and so on." Michelle has her blog. Jessa has her Instagram account. Josh has his, too—and, until yesterday, a high-profile job at Washington's conservative Family Research Council.

So the Duggars have built a micro-empire by way of the mass media. They are celebrating the rejection of mass culture through the tools of that culture. They have been using their fame; now, they are victims of it. The extremely sad scandal they are now contending with is what happens when family values collide with cultural norms.

What TLC will do with the Duggars is unclear. Earlier this year, the network cancelled Here Comes Honey Boo Boo, its alternatively beloved and belittled spinoff of Toddlers and Tiaras, after that show's matriarch, Mama June, began dating a convicted child molester. (He never appeared on the show.) But Here Comes Honey Boo Boo was not morality in the guise of entertainment; with 19 Kids, the stakes are higher. What will TLC do now that the show that so stridently celebrates the wholesome is wholesome no longer? Will the network cancel 19 Kids? Will it deal with the revelations in another Very Special Episode? It's hard to know—though it’s probably telling that the network seems to be scrubbing upcoming episodes from its schedule. Also telling? As of now, episodes of the show are still available, streaming, on the network’s website.

Unmanned

For as long as humans have been gathering in groups to kill each other, other humans have watched, whether from the front line or the sidelines, and made art about it. The impulse is a natural one—to document the most dramatic events of the time, and to make those who give their lives in the service of their country immortal—but it also allows for some understanding of the particular anxieties associated with war in different eras. As much as there are common threads, there are also distinct ones: The Iliad illuminates the grisly ramifications of wounded pride and incompetent leadership, while Picasso’s Guernica is an unflinchingly graphic depiction of the self-destruction that comes with civil war. Conflict is bloody, reports art, conflict is futile. (“The Trojans never did me damage, not in the least,” says Achilles to Agamemnon, a sentiment echoed in Tennyson’s “Theirs not to reason why/ Theirs but to do and die.”) But conflict is also specific to time and place in a way that makes cultural interpretations of it valuable excavations of the era.

Modern war—as fought primarily by drones, with 41 percent of U.S. military aircraft in 2010 being unmanned aerial vehicles—and modern renderings of it, is specific in that it is surgical, efficient, detached, and entirely inequitable. One side has the technology to target isolated military-age males from a trailer 7,000 miles away, and the other doesn’t even have a functioning air force. In his 2013 cover story for The Atlantic, Mark Bowden cited the story of David and Goliath as a parable about technology, concluding that, “David’s weapon was, like all significant advances in warfare, essentially unfair.” The fact that the odds might be stacked in the battle between “good” and “evil” might not immediately seem of primary concern, but as the endless cultural portrayals of war will testify, no side ever gets away completely unscathed.

Related Story

As drone warfare takes on an increasingly prominent role in contemporary conflict, it’s filtering into popular culture, distilling fears about agency, power, ethics, impotence, and technology all at once. In Andrew Niccol’s new film Good Kill, Ethan Hawke plays a fighter pilot relegated to a trailer in the Las Vegas desert. In George Brant’s play Grounded, running through May 24 in a production directed by Julie Taymor at the Public Theater, Anne Hathaway plays a fighter pilot who’s assigned to the same trailer (not literally) after she falls pregnant. And in the upcoming Muse album Drones, a nameless character is indoctrinated into a world of killing machines before finding his own autonomy and defeating his oppressors.

Drones have been hovering at the outskirts of the cultural zeitgeist for several years, but this is the first time they’ve been so explicitly addressed outside of the journalism and documentary worlds. Grounded debuted at the Edinburgh Festival in 2013 where it drew immediate critical acclaim, and has been staged at more than 30 theaters worldwide since then, but the current production, thanks to the star power and creative talent of Hathaway and Taymor, gives the work a new level of notability.

The play is narrated entirely by the unnamed pilot, a fearless, swaggering adrenaline junkie whose identity is shattered when she falls pregnant and is assigned to the “chair force”—the colloquial (and not entirely complimentary) term for the pilots who fly drones in 12-hour shifts from the safety of an air-conditioned trailer in the Nevada desert. “I kiss her goodbye and go to war,” the pilot says, referring to her daughter, but while the initial promise of war and peace somehow coexisting seems appealing—having a house, and a family, and the other totems of the American Dream while getting to fight terrorists by day—it soon becomes clear that the two worlds are fundamentally at odds. How do you fight a war and then go home to read bedtime stories? How do you kill others when you yourself are in no imminent danger?

“This is a story that I knew nothing about, and I was slightly ashamed about it,” says Taymor. “Telling a story about a drone pilot is a very new thing for America, but it’s going to be a topic now, as we start to engage with it. It takes a tremendous toll on somebody. What the play tells you is that it’s actually easier on the mind in a certain way to be far away with your fellow soldiers than it is to spend 12 hours a day killing people and then go home to your husband.”

* * *

The stories of Grounded and Good Kill are remarkably similar, with each focusing on the unique suffering of a pilot—whose identity is wrapped up in the act of flying itself, and the thrill of it—who’s removed from a plane and then given the incomparably difficult task of having to watch the havoc s/he wreaks in HD, in real time. “One of the things that grabbed me so much about the film was that Tommy’s ethical crisis starts not because he has problems with the war, or problems with what the government is doing,” Hawke says. “It has to do with his lack of agency in it. He misses flying. He’s omnipotent in some sense, but then impotent in his actual life. He’s totally defanged.”

Good Kill

Good Kill Tommy Egan, Hawke’s character, is a Major in the air force with a wife (January Jones) and two children, living what initially appears to be an idyllic existence. “I killed six Taliban in Afghanistan today, and now I’m going home to barbecue,” he tells a dubious liquor-store clerk in one of the film’s earliest scenes. But as with Grounded’s pilot, the chasm between his two worlds starts to become harder and harder to mentally cross. Taymor viscerally illustrates this distance with light and sound projections showing her pilot’s hour-long drive across the desert each day, past the simulacrum of the Las Vegas strip, and along a seemingly endless stretch of road. Good Kill focuses on the minutiae of life inside the trailer: the rows of screens, and the joysticks, and the various controls that feel more akin to video-game consoles than the inside of an F-16. “We are killing people,” says Lieutenant-Colonel Jack Johns (Bruce Greenwood), in a lecture to new pilots. “This isn’t fucking Playstation.” This, even though the rookies have been recruited via shopping malls and multiplexes thanks to their gaming skills.

Both Tommy and Hathaway’s pilot become attached to the flight suits they wear, seeing them as a symbol of an identity that’s rapidly being scraped away. And both are ultimately haunted by the new reality of having to stick around and watch after the bombs hit the ground. “Linger,” Hathaway says, describing her orders after a strike. “Linger.” Charles Lindbergh worried about the consequences of new military technology in the earliest days of the United States Army Air Forces, comparing fighting wars from the sky to “listening to a radio account of a battle on the other side of the earth. It is too far away, too separated to hold reality.” Then, as now, Americans were embracing a new technology that gave them enormous power without forcing them to be on the receiving end of the destruction. But the reality of being a drone pilot is different again—you’re removed from the conflict but forced to watch it on clear, high-definition screens long after people are reduced to dust and ashes.

As a drone pilot, you’re removed from the conflict but forced to watch it on clear, high-definition screens.“Tommy doesn’t put his own life at risk,” says Hawke. “It’s a very different feeling to take someone’s life when your life is threatened. There’s an integrity to it. But for Tommy, and this whole generation that’s being asked to do it, it’s a completely different things to be making mortal decisions from the safety of a Winnebago. It’s a different kind of ethical crisis.”

“When he was in an F-16,” Niccol adds, “he could drop his bomb and fly away. Now he drops the bomb and stays there, and watches the destruction he caused.”

This ability to watch the aftermath of a battleground from the comfort of a U.S. base was depicted in the first episode of the fourth season of Homeland, in which Carrie Mathison (Claire Danes) orders an air strike on a house in Pakistan after tip from a source reveals that a terrorist leader is hiding there. The strike ostensibly kills the terrorist, but also 40 civilians who’d gathered at the house to celebrate a wedding. Later, Carrie watches as a lone survivor stares up at the sky, and as bodies are pulled out of the debris. Before this is revealed, the team celebrates the strike by giving Carrie a birthday cake decorated with the words “The Drone Queen.”

* * *

A sense of anxiety about drones becoming autonomous forces in the fight against terror—fertile and powerful organisms rather than worker bees—is present in Good Kill and Grounded, even if it’s secondary to the concerns about how drone wars are affecting the Americans being asked to fight them. But it’s fully explored in Muse’s Drones, which sees drones not as a reality so much as a metaphor. The album tackles issues of agency and independence and coercion within relationships as much as it acknowledges warfare and an imagined totalitarian force that needs to be overcome, but the image of unmanned robots wielding power from the sky is always present. Muse’s Matt Bellamy told Rolling Stone that he came up with the idea for the album after reading Brian Glyn Williams’ Predators: The CIA’s Drone War on Al Qaeda. “I didn’t know how prolific drone usage has been,” Bellamy said. “I always perceived Obama as an all-around likable guy. But most mornings he wakes up, has breakfast, and then goes down to the war room and makes what they call ‘kill decisions.’”

The album sweeps between lyrics about killing and dictating orders and rejecting hope. “Your mind is just a program/ And I’m a virus, I’m changing the station,” Bellamy sings in “Psycho.” “And I’ll improve your thresholds, I’ll turn you into a super drone/ And you will kill, on my command/ And I won’t be responsible.” The song, a bass-heavy, soaring act of aggression, was released in March as a single, with an accompanying lyric video featuring a drill sergeant barking orders, and a recruit screaming, “Aye sir,” in response. “I’m gonna make you/ A fucking psycho,” the chorus goes. “Your ass belongs to me now.” Later, the song “Mercy” references a “puppeteer,” and “men in cloaks” who operate the “ghosts and shadows the world just disavows,” while “Reapers” disavows subtlety altogether to draw parallels between shady government forces and a cruel lover.

You rule with lies and deceit

And the world is on your side

You’ve got the CIA babe

And all you’ve done is brutalizeWar, war just moved up a gear

I don’t think I can handle the truth

I’m just a pawn

And we’re all expendable

Incidentally, electronically erased, by yourDrones

Killed by

Drones

As a work of art, Drones is less about overtly exploring the consequences of drone warfare than it is about making heavy-handed use of drone imagery to express feelings of isolation and rage. But it does tap into the anxiety expressed in other works about the long-term consequences of giving so much power to machines. In Grounded, this fear emerges as a suspicion directed by the pilot toward security cameras in a shopping mall, and a sense that she, too, is being tracked by the cameras she uses to monitor the movements of people several thousands of miles away. “We’ve lost privacy,” says Taymor. “She’s saying that we are being watched, and the idea that we’re not going to be watched by drones in the future is ridiculous. Drones are going to be delivering Amazon books and pizzas, but you will have no privacy. They will be able to find you anywhere.”

“Am I nervous about it? Niccol says. “It’s a fact. There’s a new step in drones, a thing called ARGUS, that has a 1.8 billion pixel camera. With two of those on drones, they could watch the whole of Manhattan.”

Good Kill’s final shot tracks Tommy Egan’s car from an aerial camera—the first time the movie gives a sense that he’s also being watched. “I really think that if you took this exact film and released it when [Niccol’s 1997 sci-fi film] Gattaca came out, it would have felt more dystopian and far-fetched,” says Hawke. “From Vegas, they’d be running these flights? Bombing a poor country like Afghanistan? The city of sin casting judgment? It would have felt too overtly metaphorical.”

“From Vegas, they’d be running these flights? The city of sin casting judgment? It would have felt too overtly metaphorical.”It’s notable that both Grounded and Good Kill explore the ways drone warfare affect the Americans participating in it, rather than the people on the other side of the world who are actually being bombed. Most cultural treatments of war tend to pick a side and stick with it, simply because it’s easier and more emotive than trying to understand the experiences of people who are projected to be the enemy. But with drones, the consequences felt by the Americans engaging in war aren’t inflicted by an enemy. They’re the product of a type of technological advancement whose benefits outweigh its unknown psychological ramifications. In Afghanistan, drones are so much a reality that they’re cropping up as designs on carpets. In the U.S., they’re still very much an abstract idea to most people.

“I remember, before I read the script, I felt hungry for it,” says Hawke. “I felt grateful, because before Bin Laden was killed there was all this talk of drones scouring the skies, and I didn’t know what it meant—was it a guy with a remote-control device a hundred yards away, was it a guy two miles away, was it a satellite feed? I didn’t know what it meant, and I had no vocabulary to understand it. I didn’t even know how to ask a question.”

As drones take on a increasingly prominent role in American warfare, so too will culture try and find ways to understand it. Often, this means interpreting the opaque language—the talk of good kills and splashes and double-taps and preemptive self-defense—as much as it does deciphering the more thorny ethical questions in play. “The population of America still thinks that drones are a great thing because they can’t put themselves in the shoes of an Afghani,” Taymor says. “They can’t reach out and have empathy and compassion for people far away. Americans have this need to identify in order to be moved to action.” Making art out of the complex realities of a new kind of warfare is a step forward, even if the stories seem to be focusing, for now, on the side with all the power.

See Spotify Run

Running alongside the Potomac River this past Wednesday afternoon, I had one of those thoughts that seems revelatory when high from either drugs or running, but obvious any other time: In the utopian future, we’ll make no decisions. Call it the cresting of the stream or the resolution of the paradox of the choice; the idea is that after the Internet has overwhelmed so many of us with so many options about so many things, the innovations to come will ease the burden of indecision. Here’s what you need to know, say newly trendy newsletters; here’s what you’re going to eat, say meal-delivery services. And now, here’s what you’re going to listen to while you sweat off brunch, says the new Spotify, the cause of this particular endorphin rush.

Though I try not to get too worked up about any app’s messianic marketing material, I couldn't help but be a little intrigued by the promotional video for Spotify’s new features for runners, unveiled at a press conference on Wednesday. Music, study after study has shown, can improve a person’s exercise routine by motivating, distracting, and pushing the body’s tempo. I’ve found this to be the case, but I’ve also found it tougher than expected to pick the correct music to achieve the desired effect. For me at least, it’s got to be fast-paced, be interesting and distinctive enough to occupy the brain, and maybe offer a few whooshing climaxes and motivational lyrics. I tend to overplay albums that fit the bill (it’s stressful to encounter a Disclosure song in the wild now, for example), never remember to make playlists ahead of time, and am constantly irritated by what radio stations choose to play. Spotify, save me from this first-world problem!

Related Story

The Golden Age of Streaming Is Over (And a New One Is Beginning)

Upon activating the feature and selecting the “Recommended for You” playlist as I trotted out of the office parking garage, Spotify asked me to run a bit so as to figure out the appropriate tempo before settling upon 165 steps per minute. The music started. Drums kicked in, the beat nicely interlocking with my footfall. But then: detuned guitars, some pained singing … uh oh, I thought. Linkin Park. The playlist purports to make choices based on your listening history, and I had, in fact, played to some Linkin Park on Spotify a while back in preparation for writing a (never finished) article about nostalgia for bad music. But I don’t actively listen to angst-at-your-parents nu metal anymore, and besides, the song Spotify served up was late-period Linkin Park—so there wasn’t even the middle-school throwback appeal. Skip.

Next up was Ariana Grande’s first hit, “The Way,” which was pleasant enough. I’d never really noticed the handclaps keeping tempo before; if you ask me to describe the song, I’d say it’s a vocal workout, not a cardiovascular one. Later, I look up the beats per minute of the track: 86, about half of 165, which with mathematical reduction being what it is, explains why it was chosen. But though the song matched my speed, it just kind of bored me, featuring none of the dynamism that my favorite running soundtracks serve up. Same went for the Big Sean, Azealia Banks, and Wiz Khalifa tunes that followed (though I liked that the app was bolstering my mainstream hip-hop cred after the rap-rocky start). Spotify knew what I’d listened to, and it knew how fast I ran. But it still didn’t know what I wanted to listen to while I ran.

So I scrolled down the menu to the “Running Originals” playlists, which had been created specifically for the Spotify running app, and selected the one that’d been promoted explicitly at Wednesday’s press conference: “Burn,” by the Dutch DJ Tiesto. Immediately, I felt less like a reluctant and occasional jogger than a Mad Max psycho soldier who’d just sprayed painted his teeth. Spotify was smart to bring Tiesto in, as dance is often called “body music” for a reason. Looping past the World War II memorial and then down the south flank of the reflecting pool, I tried sprinting. Were the increasingly excited drums in the Tiesto track accelerating along with me? No, actually. Whether I was stopped at a traffic light or weaving through tourists or bolting, Spotify never noticed when my pace changed. The screen said 165 the whole time.

The way to greater exertion: just request a faster beat.That is, until I hit the arrow buttons next to that number, raising it to 190. The music’s volume lowered momentarily as a woman pleasantly said, “Adjusting tempo.” Then there was a kind of a fast-forwarding effect on the music before the song came back, with the beat sped up to manic, Aphex-Twin-freakout levels, but without the chipmunk effect on the rest of the music that you’d expect (CEO Daniel Ek said that the tracks “magically rearrange” rather than just stretch temporally). I had the sudden urge to gun it, and galloped furiously up the Lincoln Memorial steps to strange glances from school groups, looked out at the National Mall as the music reached an epic swell—eff yeah, America!—and then went back down again.

Ah ha, there it was, the way to manipulate myself into greater exertion: just request a faster beat. Which defeats the idea of never having to choose anything, of course. And it also defeats the idea of music being an expression of personal preference: The soundtrack was Spotify’s creation, literally made with scientific assistance, intended to hype up me and anyone else who listens. In addition to the Tiesto song suite, the app has a number custom-made running “experiences,” ranging from “Epic” (which sounds like a Trent Reznor movie score) to “Seasons” (straightforwardly gorgeous orchestral arrangements). They’re each quite clever and straightforwardly pleasing, with recurring melodies, an escalating sense of excitement, and arrangements that work as well at 140 BPMs and 190. But they’re unmistakably utilities, not art.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with that. There have been other apps that offer similar running-and-listening experiences, but Spotify is the first music-streaming one to do it, and it will soon unveil more workout features courtesy of its alliance with Nike+ Running (hopefully that means it will offer route-tracking, whose omission from the service at this point is pretty glaring). Spotify didn’t revolutionize my run, but I could see turning to its Running Originals playlists when I can’t decide which of my favorite albums to try and sweat to.

The more interesting thing here might be the business philosophy. Spotify, like seemingly every app these days from Snapchat to Facebook, wants to become a Swiss Army tool that’s integrated into every aspect of your life. At Wednesday’s press conference, the company also announced it was adding video content à la a Netflix and Hulu for shortform, and moment-specific radio stations à la Songza. The mission creep irritates some critics, but the objective is clear: to make its service cooler and more useful than rivals like Tidal and Apple’s Beats, and to grab new users. That’s a crass capitalistic goal, sure, but it’s also one that could help artists. If Spotify’s new bells and whistles attract more people to participate in the paid and ad-supported streaming economy, that means more money to musicians because royalty payouts are directly tied to the company’s total revenue. That’s a beat I can run to.

Remembering Bill Zinsser

On Friday, family, friends, and legions of former students will gather in a church in New York to celebrate the life of William Zinsser, whose On Writing Well has sold more than 1.5 million copies and taught several generations of writers how to bring clarity, simplicity, specificity, and, most of all, their own voices to their writing. Like his devoted readers, his encouraging voice is the one I hear when I'm stuck on an article, and like his many former students, his red pen is the one I try to wield when revising my pieces, the hundreds of Atlantic stories I've edited, and now the many students whose writing I edit.

Related Story

They will gather in the same church where we celebrated the life of his mother, Joyce Knowlton Zinsser, just a year after he and I drove together to New York City from New Haven to start new lives—he to edit the magazine of the Book-of-the-Month Club and me, about two days past getting a diploma, to be a junior editor at a magazine. At the time, he was already an experienced critic, columnist, feature writer, teacher, editor, and longtime master of a Yale residential college, Branford, which he made a center of journalistic activity. When we arrived in New York, he had introduced me to his mother, who in turn helped welcome me to the city. When I walked down the church aisle at her funeral, he hugged me—an unexpected gesture from someone who had for so long been my teacher and who had relatively recently become a friend, and yet a gesture that was completely characteristic. Bill's life was to be open, welcoming, approving. I'd been lucky enough to experience that from his mother, an avid reader whose delight in reading I could see in her son. She wanted only news of the outside world when I visited, and was little interested in the past.

The closing hymn at her memorial that day continually repeated the word "joy," apt not just for his mother's name but also for the attitude toward life she instilled in her son. He recounted her approach in one of the essays he wrote in the dawn of the digital age for The American Scholar and that were collected in a book—the last of his 19, on subjects that ranged from collected columns for Life magazine to jazz to his writing manuals—called The Writer Who Stayed:

She thought it was a Christian obligation to be cheerful, and she managed that duty with unfailing grace to the end of her life, keeping to herself the physical and emotional aches and pains of her later years. Today, at Easter, it occurs to me that she defined being “cheerful” as far more than just maintaining a positive and life-affirming nature ... I now see that she made it her everyday task to generate light.

Of course Bill paid attention to the words to the hymn: He loved lyrics, and his favorite of his books, and mine, is Easy to Remember: The Great American Songwriters and Their Songs. We traded sheet music, of which he had reams, like baseball cards; just after I moved to a walkup near where he was living, he would generously let me spend as long as I liked leafing through it, looking for long-forgotten second verses to Irving Berlin and Cole Porter songs. We would sing them at the frequent musicales he hosted at his house and later at the Century Club; he took every chance he could to play for friends, and, as Douglas Martin recounted in his obituary in the Times, Bill said that getting paid to play jazz piano "might have been his proudest achievement."

The heart of that playing, though, was to bring people together. At the office he rented on West 56th Street, a way he found to fight the loneliness of the freelance life—a loneliness that he said brought him to Yale those many years ago—he was open to anyone who wanted advice or to say hello. He taught all over the city, and on one of my visits recounted teaching immigrant students at Columbia "who didn't know what a comma was, let alone how to construct a sentence in English." Helping people find their voices was his business, and his pleasure was keeping in touch with practically everyone he ever helped. "Come see me," he would end every phone conversation—and those were the only conversations he did not conduct in person. Though one of the first of the many follow-up writing manuals to On Writing Well that he wrote was Writing With a Word Processor, human contact was what he insisted on. No email, with its chances for, and usually insistence on, one-way communication.

Helping people find their voices was his business, and his pleasure was keeping in touch with practically everyone he ever helped.Bill’s constant interest in people and engaging with them led The New York Times to devote a front-page story to the letter he sent out, at the age of 90, inviting everyone to "attend the next stage of my life" when, blind from glaucoma, he was confined to his apartment. On my last visit, to bring him copies of a marvelous piece he wrote for The Atlantic on the pianist Dick Hyman for his website, which he kept meticulously up-to-date and complete, he was as utterly lucid and interested as always, and funny as always too: He began a sentence, "When you're 82, or 102, or 92, or however old I am ..."

Echoing his mother, he wanted only news of the present, and wasn’t interested in being drawn on the past. I offered to bring him news of the many Broadway shows I get to see in my lucky duties as a nominator for the Tony Awards; he'd been the New York Herald Tribune's theater critic in the late 1940s, but didn't want to hear about "whatever damned thing the butler says." Instead he liked movies, and had consented to go to a showing of Lincoln with his longtime student and devoted friend Mark Singer, whose own warm and precise tribute just appeared on The New Yorker's website, because of their shared love of Lincoln's language. "I want you to come with stories to read me from The New York Review of Books or anything that will tell me things I don't know about the world I'm living in now," he said.

I won't be coming down the aisle again, waiting to hug Caroline, his wife of 60 years, and his children, Amy and John, who were already fully formed characters on campus when I was a student, or the many former students who have long defined ourselves by having been his students. (My classmate Wilder Knight years ago said, cannily, "Bill is the person I want to be when I grow up. He's showing us how to grow old.") I write this from a gig I think he wouldn't have wanted me to cancel: an intensive writing seminar at Slow Food's University of Gastronomic Sciences, where I have regularly taught since it began, 11 years ago. I hear Bill as I try to cut constantly to find the heart and essence of a story, and urge them to read every piece aloud to be sure it sounds like them and always, always rewrite. On Writing Well is a classic for a reason: His voice is always on the side of the writer, and always tells you that you can find your way out of a problem. It helped my students at an MIT course on the science essay this semester, where we observed a moment of silence the night he died.

This afternoon I found myself counseling a student who assured me she couldn't write by saying, No, the inarticulateness she imagined actually led to unusually rich and spare prose full of life and meaning; she was a wonderful writer. It was Bill's voice I was hearing as I spoke. When I would come to read him my very first freelance stories, along with the constantly wielded red pen he would always find some quote I'd picked out, or some small phrase, to make him look up, shake his head, repeat it, and say "Just wonderful." That's what he did in class, what his mother would have done, and what kept his hundreds of students going through the inevitable, constant rough patches. We'll have to hear that constantly cheerful, constantly encouraging voice for ourselves now.

In Tomorrowland, the End of the World Is Disneyfied

Disney’s Tomorrowland opens with the pleasant visage of George Clooney, recording an explanatory video for purposes unknown. “Am I on?” he wonders aloud. “Hey, I’m Frank. How’re you doing? ... This is a story about the future, and the future can be scary.” A young woman interrupts from off-camera: “Try to be a little more upbeat.”

Related Story

The State of 2015's Summer Movies

It’s hard to imagine a more accurate advertisement for the movie to come—a perfect proxy for the essential question posed by the blockbusters residing at the multiplex this weekend: How do you like your apocalypse? If your tastes run to the arid and spiky, to desolate, post-nuclear landscapes populated by automotive marauders clashing over dwindling supplies of oil, water, blood, breast milk, and viable fetuses—then get yourself to Mad Max: Fury Road immediately. (Or, if you’ve already seen it, get yourself back to it again.) But if you prefer your End of the World to be a little shinier, more optimistic, more Disney—it may be that Tomorrowland is just the ticket.

That is not, incidentally, intended as an insult. Or at least, not entirely as one. At its best, Tomorrowland, is a clever, good-natured, PG adventure featuring robots and ray guns, jetpacks and Jules Verne. At its worst ... Well, we’ll get to that. Suffice it to say that Tomorrowland is considerably better than you might expect given that it is named after a region—not even a ride, a region—within Disneyworld’s Magic Kingdom and its associated theme parks around the globe. Does that conical dome in the distance bear a striking resemblance to Space Mountain? Why yes, it does. (Remarkably, this is not the first time Disney has offered up the same gag: In the 2007 animated movie Meet the Robinsons, a segment taking place decades in the future featured a Space-Mountain-y ride at a theme park called “Todayland.”)

That the movie succeeds at all is a testament to the gifts of director Brad Bird (The Iron Giant, The Incredibles, Mission: Impossible–Ghost Protocol), who keeps things rolling along amiably, from a script he co-wrote with Damon Lindelof. Following Frank’s half-hearted self-introduction, we get his backstory: a boyhood visit to the 1964 World’s Fair, where he presents his homemade jetpack; an encounter with a peculiar young girl, Athena (Raffey Cassidy), who tells him “I’m the future”; and a trip on the “It’s a Small World” ride, which debuted at that World’s Fair and in which—I promise I am not making this up—young Frank discovers an inter-dimensional portal to a futuristic metropolis in the middle of a wheat field, featuring flying “hover-rails” and the aforementioned building that looks just like Space Mountain.

If you prefer your End of the World to be a little shinier, more optimistic, more Disney—it may be that Tomorrowland is just the ticket.The movie soon switches gears, however, as the young woman we initially heard off-screen takes over narration duty from grownup Frank to tell her own backstory, which is essentially the main plot. Her name is Casey Newton (Britt Robertson), and like the young Frank, she’s a precocious tech wiz. Her principal hobby, however, is sabotaging efforts to tear down the NASA launch pad at Cape Canaveral, which for her offers a ray of hope for the future—reach for the stars!—in a sea of contemporary pessimism. (Her high-school curriculum seems to consist exclusively of dismal warnings about global warming and nuclear Armageddon; even her English class teaches only Brave New World, 1984, and Fahrenheit 451.) When Casey is picked up by police following another episode of vandalizing federal property, she finds a vintage pin among her returned belongings—a pin that, when she touches it, transports her to the selfsame Tomorrowland where Frank traveled as a boy.

Casey’s journey is fleeting, however, and soon enough she’s dumped back in our grubby, compromised world, desperate to return to her shiny utopia. Cue up the smilingly murderous robots, the rendezvous with Frank—now grown into full Clooneyhood as a reclusive inventor—a visit to the Eiffel Tower (which is Not At All What You Think It Is), and so on. For much of its running time, Tomorrowland plays as a lighthearted techno-conspiracy thriller, Men in Black by way of Nancy Drew with the occasional whiff of Philip K. Dick paranoia and Pixarian high concept. And if the movie now and then bears a niggling resemblance to a theme park ride—well, therein lies its genesis and, quite possibly, its future.

Finally though, Casey and Frank make their way back to Tomorrowland, and the movie’s heady, gee-whiz velocity largely gives way to a series of sententious sermons about hope and despair, the abiding importance of imagination, etc., etc. Is the Earth—our Earth—truly doomed to destruction? Why was Frank expelled from Tomorrowland long ago? What was that video he and Casey were making at the beginning of the movie? If you’re like me, you might feel that some of these mysteries might have been better left unsolved.

In an unintentionally telling moment, Frank, exasperated by Casey’s constant inquiries, asks her, “Do I have to explain everything? Can’t you just be amazed and move on?” If only Tomorrowland had heeded his sage advice.

The Messy Politics of Trade and the Export-Import Bank

The debate over trade, jobs, and economic growth took an unexpected turn on Thursday, as an unusual alliance of senators linked congressional approval of President Obama’s trade agenda to another, less-heralded piece of his economic platform: reauthorization of the Export-Import Bank. The two issues collided in a dramatic Senate vote, and the White House barely escaped having one of its prized policies derail the other.

On the president’s top priority—Trade Promotion Authority—wavering Democrats joined most Republicans to push the bill over a key procedural hurdle. Yet those Democrats offered up their votes in exchange for a commitment from Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to consider legislation next month reauthorizing the Export-Import Bank, an 80-year federal lending agency that has been on life support in Congress for nearly a year.

On the surface, the trade pacts and the Ex-Im Bank are distinct issues, and their intersection this week had a lot to do with timing. (The bank’s charter expires at the end of June, and Congress is about to depart for a weeklong Memorial Day recess.) But they are more related politically than you might think. Liberals oppose agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership because they believe they would undermine government regulations that protect American workers. The Ex-Im Bank supports U.S. jobs by helping companies find markets for their goods overseas—or at least that’s the argument from its backers in both parties.

But many conservatives oppose the bank for interfering with the free market, regarding it as a form of corporate welfare in which taxpayers end up subsidizing giants like Boeing and GE that don’t need government help. They oppose tariffs and trade restrictions on much the same grounds. Creating an unfettered market, they argue, entails more free trade and the elimination of the Ex-Im Bank.

Politically, the two issues make up something of a Venn diagram—the support for both overlaps in the middle. Centrist Democrats and most Republicans back Trade Promotion Authority and the agreements that would follow, while most Democrats and a sizable chunk of establishment Republicans support the Export-Import Bank. Progressives like Bernie Sanders oppose both trade deals and the bank; more business-friendly Democrats like Maria Cantwell and Republicans like Senator Lindsey Graham support the two policies; and committed free-marketeers like Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio back trade but want to kill Ex-Im.

For the Obama administration, the absence of defeat is not the same as victory. The “fast-track” trade bill now has a clear path to passage in the Senate, so long as it doesn’t get tripped up by a few more amendment votes. It faces a much tougher road in the House, however, where leaders in both parties have indicated it currently lacks the votes to pass. The president’s traditional Democratic allies have thus far withheld their support, and Republican leaders can’t pass it on their own because some of their members won’t support anything that helps Obama.

The fault lines on the Ex-Im Bank are in many ways more parochial. Two of the banks biggest supporters in the Senate are Democrats Patty Murray and Maria Cantwell of Washington State, which is home to Boeing. Both also back the president on trade, but when it came time to break a Democratic filibuster on the fast-track bill Thursday morning, Murray and Cantwell led a group of senators who refused to cast their votes until McConnell promised to schedule a vote on Ex-Im in June before its charter expires. One of those senators was Graham, who tweeted that McConnell assured him that he’d attach the Ex-Im reauthorization to another must-pass bill replenishing the Highway Trust Fund in July—which might be necessary if the House fails to act.

The House is again the biggest obstacle to re-upping the Ex-Im Bank. Deriding the agency as the embodiment of “crony capitalism,” conservatives have turned its impending demise into a cause célèbre, and the chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, Jeb Hensarling of Texas, has made it his personal goal to let the bank’s charter expire. Speaker John Boehner supports Ex-Im, but due to his shaky political standing, he has treaded carefully in defying his conference’s right flank. He told reporters on Thursday that he refused a personal request by Cantwell to commit to allowing a vote on the bank’s reauthorization, and he said that if the Senate passed a bill next month, he’d let conservatives try to amend it.

Working together, Cantwell, Murray, and Graham seized an opportunity to leverage their influence on trade—and the joint desperation of McConnell and Obama to break that impasse in the Senate—by securing a lifeline for the Ex-Im Bank. “I’m not going to support a trade bill that doesn’t deal with this issue,” Graham said, according to Politico. Cantwell said Obama assured her that he would make the bank “a part of the entire trade package.” The issues may now be linked, but that doesn’t mean Obama will necessarily get two wins for the price of one: For that to happen, Republicans would have to abide the government’s hand interfering in one part of the market while lessening its role in another.

May 21, 2015

What's Missing in the Indictments Over Freddie Gray's Death

In a very brief news conference at the end of the day Thursday, State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby announced that a grand jury had indicted six officers in the death of Freddie Gray.

For the most part, the indictments closely track the charges the Baltimore prosecutor announced in a May 1 press conference. (ABC2’s Christian Schaffer has the full charges here.) In particular, the second-degree depraved-heart murder charge against Officer Caesar Goodson, the most serious of the charges, remains. All six officers were also indicted for reckless endangerment, which was not on the original charge sheet.

The big change: None of the officers was indicted for false imprisonment. That’s notable, because Mosby emphasized during her initial statement that Gray’s very arrest was illegal, saying officers had no basis for detaining him.

Argument since Mosby’s May 1 announcement has focused on the knife Gray was carrying. Attorneys for the officers say that the knife was in fact illegal, making the arrest legal. The debate hinges on both the jurisdiction and whether the knife was spring-loaded. Prosecutors indicated earlier this week that they believe the arrest was illegal even outside of that debate, since Gray was arrested before officers discovered his blade.

Related Story

Can the Baltimore Prosecutor Win Her Case?

Mosby didn’t offer any comment on the dropped false imprisonment charge on Thursday. Earlier this month, I spoke with David Jaros, an associate professor at the University of Baltimore School of Law, who noted that a false-imprisonment charge in a case like this was unusual. While he said it could prove to be a useful tool for prosecutors in trying to tamp down police abuse, he also doubted that prosecutors would use it. “At the end of the day, prosecutors want police officers out there making arrests. I think most prosecutors think the solution to being arrested for actions that are not a crime is simply that [arrestees] get released,” he told me.

Grand juries are generally fairly willing to follow prosecutors’ lead on charges, so it’s not a surprise that the indictments largely follow Mosby’s original charge sheet. But she did come in for criticism from observers who felt that she had moved too quickly after Gray’s death and should have waited for a grand jury to review charges. Thursday’s indictment ratifies most of her original judgment, but the broader question of whether Mosby’s charges are well-suited to the case won’t become clear until later in the process. The six officers are due to be arraigned on July 2.

Why Are the Republican Debates Limited to 10 Candidates?

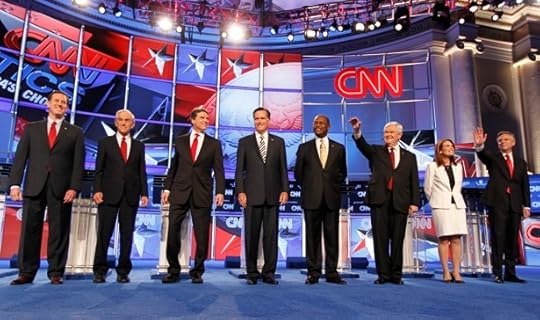

In an increasingly quantified and poll-obsessed political world, it’s not often that you get arbitrary numbers. A rare exception came Wednesday, when CNN and Fox both released their guidelines for 2016 Republican debates—coming to a swing state near you, this fall! The most discussed, and curious, element in the rules set was the number of candidates who will be allowed on stage: an even 10.

Fox’s standard for an August debate in Cleveland is fairly straightforward. A candidate “must place in the top 10 of an average of the five most recent national polls, as recognized by FOX News leading up to August 4th at 5 PM/ET. Such polling must be conducted by major, nationally recognized organizations that use standard methodological techniques.”

CNN uses a similar but more elaborate standard for its September 16 debate at the Ronald Reagan Library:

The first 10 candidates—ranked from highest to lowest in polling order from an average of all qualifying polls released between July 16 and September 10 who satisfy the criteria requirements ... will be invited to participate in 'Segment B' of the September 16, 2015 Republican Presidential Primary Debate.

But then it takes a weird turn. CNN also creates a loser’s bracket (or as the Atlanta Journal-Constitution calls it, a “kid’s table”) for candidates who are polling at 1 percent or higher in three national polls but don’t otherwise meet the requirements. They’ll appear in a separate segment of the same debate, a rather limp consolation prize.

There have been controversies over who gets invited to a debate before—you could ask Dennis Kucinich or Gary Johnson, though they’d probably be happy to tell you even if you don’t ask. But usually the question is cutting out the candidates who don’t seem to be a real factor, not about making sure you can fit them all on stage.

This year, the problem is that the Republican Party simply has too many legitimate candidates. It’s not that there haven’t been large debates before—the Republicans had as many as nine candidates for a debate during the 2012 cycle, and Democrats topped out at eight during the 2008 cycle. But in each of those cases, they were including every plausible candidate, plus often at least a couple who weren’t plausible. (Sorry, Mike Gravel.)

Related Story

The 2016 U.S. Presidential Race: A Cheat Sheet

But the 2016 field seems unique. It’s fairly easy to name some members of its top tier, which includes Jeb Bush, Scott Walker, and Marco Rubio. But it’s hard to design a criterion that makes a great deal of sense for sorting the rest. What’s strange is not that there are so many candidates, since there are often plenty of long shots. What’s strange is that there are so many candidates who could plausibly go a long way in the field, but who also might burn out early.

How high is Rand Paul’s ceiling? Is Ben Carson a serious candidate? Is he more serious than, say, John Kasich, an experienced politician who’s polling well behind Carson? (One strange artifact of the rules is that if the cutoff were today, the debate in Cleveland would exclude Kasich, who is governor of Ohio.) Should Carly Fiorina be on stage? Especially at this early point, it’s hard to know who will sink into oblivion (or remain mired there) and who will rise. Anyone seeking proof of this volatility need only look at the dizzying changes on the GOP leaderboard in 2012.

And yet it’s very clear that the field needs to be limited. The 2008 and 2012 examples showed that eight and nine candidates are simply too many. The result is something more like a round-robin quiz than a debate—every candidate can answer a question, but it’s hard to create any serious discussion or exchange of ideas, and the only way a candidate can delve into a topic is at the expense of his or her rival’s given time. In fact, 10 is likely to be far too many for any conversation, too, meaning that the networks have chosen an arbitrary limit that neither accommodates all of the candidates nor facilitates a satisfying debate.

The GOP has an especially diverse field of candidates this year, including Carson, Fiorina, and Bobby Jindal. But as Joshua Green noted, there’s a danger that the rules could end up knocking out some of that diversity. Neither Fiorina and Jindal would make the cut if the cutoff were today, using RealClearPolitics’ rankings.

But 10 is a nice round number, and it’s also the number of buttons on a standard telephone keypad—which may not be a coincidence. Steven Shepard noted last week the challenge facing pollsters right now. “There are 19 Republicans seriously considering launching campaigns for president, and 10 numbers on a phone. That causes a big problem for pollsters using automated polling technology, one of the most common forms of public polling,” he wrote. Some pollsters like to include an undecided option—knocking the number of available slots down to nine. The result is that it’s very hard to design and execute a reliable automated survey that accounts for the entire field. (Non-automated polls, meanwhile, are extremely expensive and time-consuming.)

One last complicating factor: With a field this large, at this early stage, and with a month between debates, the top 10 candidates in the field could be a substantially different group at the two debates. That will make for some freshness, but it’s not the best way to guarantee continuity of discussion, especially with a small battalion of hopefuls behind podiums. Perhaps the debates will at least produce some funny memes, outlandish wagers, and … uh, I forgot the third thing. Oops.

The End of the Boy Scout Ban on Gay Adults?

On Thursday, Boy Scouts of America President Bob Gates called for the end to the organization’s ban on gay adults who serve as troop leaders or have other roles within the organization. Addressing the group’s National Annual Business Meeting, he said:

I am not asking the national board for any action to change our current policy at this meeting. But I must speak as plainly and bluntly to you as I spoke to president when I was director of CIA and secretary of defense. We must deal with the world as it is, not as we might wish it to be. The status quo in our movement’s membership standards cannot be sustained.

What This Means for the Boy Scouts

In addition to calling for an end to the ban, Gates added that he would not seek to revoke the charters of Boy Scouts chapters that allow gay adults to serve in defiance of the existing ban. He specifically mentioned two chapters, one in New York and the other in Colorado, that hired gay scoutmasters or volunteers. (Just last year, a chapter in Seattle had its charter revoked for refusing to fire a gay scoutmaster.)

He also warned that “any other alternative will be the end of us as a national movement.” Should the Boy Scouts of America embrace his statement, a resolution to change the policy will likely materialize when the group’s governing body meets next.

A Brief Timeline of the Gay-Rights Movement Within the Boy Scouts

Gates’s statement is the latest in a progressive push by the Boy Scouts. In May of 2013, Boy Scout leaders voted to end its ban on gay youths with nearly two-thirds supporting a measure that said membership could not be denied “on the basis of sexual orientation or preference alone.”

Despite the flurry of recent activity, Zach Wahls of Scouts for Equality told me that the movement to permit gay youths and gay adults began in earnest in the 1970s. One particular turning point was a Supreme Court decision in 2000 that reaffirmed the group’s constitutional right to ban gay members.

That decision cost the organization some of its more politically neutral local sponsors upon which the group relies. “When the Scouts won their Supreme Court case, all the public schools walked away,” Wahls said.

He noted that 70 percent of the local nonprofit groups that the Boy Scouts work with are frequently churches. The Girl Scouts, which rely less on local institutions for support, have long allowed gay and lesbian scouts and leaders. The Girl Scouts set a national culture while the Boy Scouts have autonomy on the local level.

That dynamic has made the division over gay scouts and gay leaders particularly contentious over the years. As Erik Eckholm notes, “Conservative religious groups that sponsor many Scout troops, including the Mormon Church and the Roman Catholic Church, have opposed the participation of openly gay members while local leaders in more liberal areas have called for an end to the ban.”

What Gates’s statement ultimately does is call for the end of a national ban at the national level. While local chapters may go their own way, they may find themselves on the opposite side of a groundswell.

“What we’re seeing is the beginning of the end,” Wahls added.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower