Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 429

May 21, 2015

Mediterranea Explores the Perilous Journey to Europe

Few topics have more current relevance and urgency than the ongoing tragedy of African migrants crossing the Mediterranean, the subject of the Italian American director Jonas Carpignano’s first feature film. Since the start of the year, more than 1,500 people have died attempting the hazardous crossing—and thousands more have moved on to a precarious existence in Italy and other European countries. In Mediterranea, which screened in the Critics’ Week sidebar at the Cannes Film Festival on May 19, Carpignano goes beyond the gruesome headlines to focus on the little-known hardships of migrants after they set foot on Italian soil, patiently setting the stage for a dramatic reconstruction of the riots that rocked the southern town of Rosarno in 2010. The script is inspired by real events, interviews, and the director’s own journey through North Africa—interrupted only when Algerian authorities warned him about the presence of al-Qaeda cells in the area.

The film’s beautifully shot opening scenes give a cursory but vivid portrayal of the migrants’ grueling, initial journey to the sea. Clinging to overloaded trucks or walking through desert terrain, they’re easy prey for bandits and exploitative traffickers. Upon reaching the Libyan coast, the migrants find out they have to pilot the rickety vessel themselves because the smugglers won’t do it.

Amid the gloom, there’s a moment of levity when one man argues that the film’s protagonist, Ayiva (Koudous Seihon), who hails from Burkina Faso, can’t pilot the boat because he’s from a landlocked nation and has probably never seen the sea. The Mediterranean’s treacherous waters soon cause the vessel to capsize. Some on board survive by clinging to a floating structure until they’re rescued by the Italian coastguard, but a chilling underwater shot reveals the floating bodies of those who didn’t make it.

More From Saul’s Inferno: Searing Holocaust Drama Stuns Cannes Cannes 2015: What to Expect at This Year's Film Festival Cannes Film Festival Announces Jury

Saul’s Inferno: Searing Holocaust Drama Stuns Cannes Cannes 2015: What to Expect at This Year's Film Festival Cannes Film Festival Announces Jury The film follows Ayiva and his friend Abas (Alassane Sy) to Rosarno, in Italy’s southern Calabria region. They have received a three-month permit to stay in the country, but need to land a job to apply for long-tem residency—a near-impossible mission. Calabria turns out to be cold (it’s in the middle of the orange-picking winter season) and desolate, with few job prospects. The migrants live in filthy shacks and squats, vulnerable to eviction by the police. They’re exploited for their labor in the orange groves and paid a pittance.

The gap between their expectations of Europe and the reality they encounter is glaring. Ayiva promptly warns his sister and daughter, who stayed behind, not to attempt the crossing. The disillusionment is palpable, but so is his profound joy when he sends his first 50 euros and a gift for his daughter back home. While Ayiva is aching to go back, he knows this is not an option.

Mediterranea draws an equally insightful portrait of southern Italy, a traditional, economically backward land that’s ill-equipped for the challenges of immigration. It’s a place of contrasts, where the locals’ conflicting instincts of generosity and narrow-mindedness leave the migrants disoriented and insecure. The colorful cast of characters includes an improbable child hoodlum (played by the superb Pio Amato) who trades in stolen goods, and a patronizing Good Samaritan who cooks lasagna for the migrants and calls herself “Mamma Africa.” The film’s director is now working on a sequel centered on migrants’ interactions with the fearsome Calabrian mafia. If it’s anything as shrewd as his first feature, it should cast light on another little known facet of the Mediterranean’s great migrant tragedy.

Simon Pegg Shouldn't Panic About the 'Childish' State of Cinema

There’s something simultaneously exhilarating and tiring about a celebrity biting the hand that feeds. When the actor and writer Simon Pegg—a fixture in the worlds of comedy and genre films for the past two decades—told the British magazine Radio Times recently that cinema’s trend towards sci-fi and spectacle had “infantilized” the viewing public, to the point where “we’re essentially all consuming very childish things,” it was easy to understand both the fan outrage that followed and the knowing nods that maybe he had a point. After all, Pegg—who’s a member of the Star Trek and Mission Impossible franchises—knows the world he’s criticizing intimately.

“It is a kind of dumbing down, in a way,” he said, “because it’s taking our focus away from real-world issues. Films used to be about challenging, emotional journeys or moral questions that might make you walk away and reevaluate how you felt … Now we’re walking out of the cinema really not thinking about anything, other than the fact that Hulk just had a fight with a robot.”

Related Story

Hollywood Should Make More Superhero Films

It’s tempting to wonder where Pegg, the self-proclaimed “poster child” for geekdom, might be without the popular and acclaimed movie series that have made him personally wealthy and successful, but it’s also beside the point. While he’s right to ask questions about the moral and emotional complexity of the majority of films hitting the multiplexes, he’s ignoring the bigger picture. Comic-book adaptations and sci-fi franchises used to cater to a niche demographic and now seem to equal box-office gold, but that doesn’t mean the genre is totally devoid of deep meaning, or that its ascension threatens the kind of “challenging” filmmaking Pegg thinks more audiences should benefit from. Rather, tentpole movies and superhero series tap into a desire for spectacle that’s been inherent in cinema since its earliest days.

Before he was Scotty in J.J. Abrams’ rebooted Star Trek films (a series for which Pegg is currently scripting the third installment) or the comic anchor Benji in Mission: Impossible III and IV; even before he was the star of cult British genre flicks like Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz, Pegg was an up-and-comer in Britain’s 90s alt-comedy TV scene. He was part of the ensemble of the cult sketch show Big Train, and appeared in episodes of the news-magazine spoof Brass Eye, and the largely forgotten sitcom Hippies. All three trafficked in absurdity, cynicism and black humor, but it wasn’t until 1999 that Pegg found his true calling when he co-created the sitcom Spaced with Jessica Stevenson.

Spaced remains a brilliant love letter to the fandom of Pegg’s adolescence—Star Wars, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, horror films, video games—that simultaneously poked at the arrested development of a generation that filtered everything through their experience of pop culture. In a follow-up post on his website expanding on his comments, Pegg noted his long exploration of this dichotomy in his work. “One of the things that inspired Jessica and myself, all those years ago, was the unprecedented extension our generation was granted to its youth, in contrast to the previous generation, who seemed to adopt a received notion of maturity at lot sooner,” he said. “This extended adolescence has been cannily co-opted by market forces, who have identified this relatively new demographic as an incredibly lucrative wellspring of consumerist potential.”

In the 21st century, Hollywood has learned to cater to a subculture previously treated as irrelevant.Indeed it has—and Pegg would surely be the first to admit he’s benefitted greatly from that market adjustment. Watching Spaced now, you can easily detect the visual verve of director Edgar Wright, who would go on to make three films with Pegg and the terrific comic-book adaptation Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, even if you’d hardly have predicted in 1999 that Pegg would be writing Star Trek movies for Paramount Pictures. But in the 21st century, Hollywood has learned to cater to a subculture previously treated as an irrelevant sliver of the box-office pie, and it shows no sign of wanting to stop. Fans used to cross their fingers that an attempt at a big-budget superhero movie—say, 2000’s X-Men or 2002’s Spider-Man—would do well enough to convince Hollywood to produce more along the same lines. Now, when a comic-book film is announced, it comes with a handful of sequels and spinoffs already in the pipeline.

“I guess what I meant was, the more spectacle becomes the driving creative priority, the less thoughtful or challenging the films can become,” Pegg wrote, while allowing that he’d been buoyed by the quality of the recent movies Ex Machina and Mad Max: Fury Road. Much like the author and Grantland contributor Mark Harris, he points to the 1970s as a golden age where Hollywood explored real issues such as the Vietnam War with films like Taxi Driver—challenging films produced by major studios for big budgets.

But as Katherine Trendacosta noted at io9, Hollywood has always enjoyed spectacle, from the silent era on, and there’s plenty of genre filmmaking that has grounding in real-world issues. The Vox editor Todd Vanderwerff recently wrote a fascinating analysis of the 21st-century superhero movie’s inescapable connection to 9/11 and America’s response to that tragedy, and his argument doesn’t feel like a stretch. Yes, the Hulk fights a robot in Age of Ultron, but in a sequence of city destruction that spurs him to go into solitude to avoid further catastrophe—making a point about the relative value of the heroes’ immense power compared to the threats that power inevitably conjures. Pegg should know that Joss Whedon, who wrote and directed that film, is a thoughtful writer and director—after all, Pegg’s character in Spaced frequently prayed to a life-size cardboard model of Whedon’s most famous creation, Buffy Summers.

Hollywood has always enjoyed spectacle, but there’s plenty of genre filmmaking that explores real issues.Perhaps most ironic is Pegg invoking the name of the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard, specifically his 1986 book America, which Pegg says advanced the idea “that as a society, we are kept in a state of arrested development by dominant forces in order to keep us more pliant. We are made passionate about the things that occupied us as children as a means of drawing our attentions away from the things we really should be invested in.”

Indeed—and there was a film that explored those themes in some detail that had a fair amount of cultural impact, produced by a Hollywood studio in 1999, that even spawned a couple of sequels (it’s called The Matrix). The Wachowski siblings, who directed that sci-fi benchmark, praised Baudrillard for inspiring the work; their sequels, The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions, delved further into dense philosophical debate, though perhaps at the cost (most critics would argue) of enjoyment for the viewer. The issue with Pegg’s argument, or Harris’s, is the issue with almost any sweeping statement about an industry as large as Hollywood—it’s not hard to find exceptions.

But there’s no value in shouting down Pegg for sparking worthwhile discussion on the limits of this kind of commercialism. Hollywood constantly works to strike a nervous balance between art and commerce—trend too far in one direction, and audiences will lose interest, the thinking goes. Marvel’s films succeed not just because they’re empty spectacle, but because they’re presenting an exciting kind of long-form storytelling movies haven’t seen before. Still, at a certain point, just as with television or comic books, audiences will want a definitive conclusion, not another post-credits teaser. Pegg’s comments might have angered fans (and possibly studios) but they’re part of an ongoing conversation that can only help culture if both sides are willing to engage.

'If You Aint Cheating, You Aint Trying': The Brazen Greed of the Currency-Manipulating Bankers

Were they greedy, or were they just foolish?

It’s one of the big questions from the 2008 economic crisis that remains open to debate. Did the world’s banking system nearly collapse because financiers were grabbing money wherever they could, no matter the costs, or was it because bankers failed to understand the risks caused by a housing bubble and credit crunch?

In at least one case, there’s a ready answer: They were both greedy and foolish.

An agreement between five banks and the federal government, announced Wednesday, forces five banks to pay a combined $5.6 billion and plead guilty to rigging markets. Four banks—Barclays, Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase, and the Royal Bank of Scotland—pled guilty to antitrust violations. UBS received immunity in the antitrust case, but will plead guilty to manipulating the London Interbank Offer Rate, or LIBOR, a benchmark interest measure. (An earlier federal agreement with UBS was rejected by a federal judge as too lenient.)

“mate yur getting bloody good at this libor game . . . think of me when yur on yur yacht in monaco wont yu”In a combination of horrifying and entertaining, the settlement agreements provide many excerpts from conversations that show bankers who knew what they were doing was improper but enjoyed it anyway. In a series of chummy chats, they gleefully collude on setting exchange rates, help each other out at the expense of customers and, more broadly, violate the public’s trust in markets as fair exchanges. They also appear shockingly cavalier about creating a digital trail as they manipulate world markets. If it’s not a fair representation of the finance industry generally, it is certainly an excellent representation of the worst stereotypes about the industry.

“mate yur getting bloody good at this libor game . . . think of me when yur on yur yacht in monaco wont yu,” wrote one to another. LIBOR depends on banks self-reporting lending rates. But misreporting may have offered a falsely rosy impression leading up to the credit crunch, with banks reporting they could borrow more cheaply than they actually could.

As the quote shows, participants were blithe about what they were doing. One online chat room even referred to itself as “the cartel.” Documents record multiple cases of debates about who to allow in, who to keep out, and how to know whether to trust someone. In one case, a Barclays employee asked to join, but was invited only on a probationary basis—and with a threat:

After extensive discussion of whether or not this trader “would add value” to the Cartel, he was invited to join for a “1 month trial,” but was advised “mess this up and sleep with one eye open at night.”

In some cases, as in this one from UBS, bankers rewarded each other with booze for their work:

Broker-A1: think [Broker-A2] is your best broker in terms of value added :-)

Trader-1: yeah . . . i reckon i owe him a lot more

Broker-A1: he's ok with an annual champagne shipment, a few [drinking sessions] with [his supervisor] and a small bonus every now and then

Generally, the atmosphere was one of mutual encouragement and aggrandizement:

Subsequent to the fix, traders in the chat rooms congratulated one another by saying: “nice work gents…I don my hat”, “Hooray nice team work”, “bravo…cudnt been better” and “have that my son…v nice mate” and “dont mess with our ccy [currency]”. One of the traders commented “there you go … go early, move it, hold it, push it”. HSBC stated “loved that mate… worked lovely… pity we couldn’t get it below the 00” and “we need a few more of those for me to get back on track this month.”

Ostensibly, the figures involved were competing with each other, rivals for the same money. In practice, it seems they were pulling together. As a Barclays employee noted, “the less competition the better.” A sense of camaraderie pervades conversations, as the groups band together even against their own firms. Discussing a possible participant, one Citibank trader wondered, “is he gonna protect us like we protect each other against our own branches[?]”

Making money, even at customers’ expense, was cause for celebration. A bank might effectively lie to its customers about the price of foreign currency and pocket the difference, a Barclays vice president boasted:

markup is making sure you make the right decision on price . . . which is whats the worst price i can put on this where the customers decision to trade with me or give me future business doesn’t change . . . if you aint cheating, you aint trying.

Bankers also used codes and signals to jack up the amount customers would be charged:

Certain UBS FX salespeople and traders used hand signals during certain customers’ “open line” calls in order to conceal from customers that they were being marked up. For example, unbeknownst to the customer, a salesperson would hold up two fingers to signal that the trader should add mark up of “two pips” to the quoted price.

Remarkably, these conversations were conducted in online chat rooms, where they were legally discoverable. Not that there wasn’t concern. “[A]ll senior management ... want to show the world we are the strongest bank with loads of liquidity,” one UBS trader complained about his firm’s low submissions. “We’d lend at 0 US! Has been a lot of media focus on barclays libor fixes so they are paranoid.”

In another case, a UBS employee charged with adherence to LIBOR standards seems to acknowledge the funky business.

“JUST BE CAREFUL DUDE,” the banker wrote.

“I agree we shouldn’t ve been talking about putting fixings for our positions on public chat,” the employee who submitted rates replied.

Much of the conversation is far more quotidian. Bankers make requests to each other for submissions that will help them on certain trades and certain days, feel each other out, and thank each other for the help. Requests for changes to exchange rates and interest rates fly back and forth with the casual feel of video gamers swapping cheat codes.

The brazenness of the operations, and the many damning exchanges to be found in the court documents, might explain why this is a rare case where banks have been forced to plead guilty for conduct involved in the financial crisis. (Individual traders and brokers are neither named nor indicted.) Critics have attacked previous settlements in which banks agreed to pay fines but escaped actually pleading guilty, and in this case the Justice Department insisted on pleas.

On the other hand, the fines pale in comparison with the banks’ balance sheets—even when combined with the more than $4 billion that some of the banks agreed to pay regulators for currency manipulation in November. And despite being branded felons, all five banks have secured waivers that allow them to continue to do business as usual. In other words, they’ll be just fine. Greedy? Sure. But maybe not so foolish after all.

The Art of the Poster

When most museums put on poster exhibits, they tend to walk viewers through the histories of different artistic styles, ranging from Art Nouveau to Bauhaus. So when the Smithsonian’s newly renovated and re-energized Cooper Hewitt Design Museum in New York took stock of its hefty collection of 3,000 rarely seen posters, it wanted to create a display that would explore the works as more than just ink on paper.

The museum’s veteran senior curator of contemporary design, Ellen Lupton, aimed to host a non-traditional but accessible exhibition explaining the principles of visual communications that designers use to create posters in the first place. How Posters Work is gem of a show that gives visitors an opportunity to learn the logic behind the format. The exhibit is organized around 14 key concepts, prompting visitors to consider why some images grab their viewers’ attention while others are forgettable.

Related Story

“Posters are the only genre of graphic design that is explicitly created to be stuck on a wall,” Lupton told me in an email. “Many people are more comfortable displaying posters in their own homes or work spaces than they are with more formal or serious works of art. Posters are part of everyday life, so they feel approachable and real.”

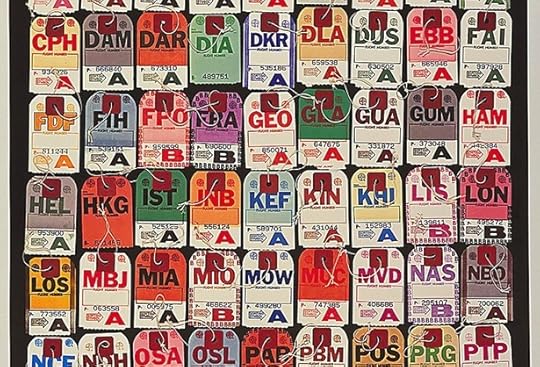

Among the guidelines laid out in the exhibit is the unofficial “10-foot rule,” which demands posters must be legible from at least 10 feet away. Lupton pointed to Ivan Chermayeff’s 1977 poster, which features dozens of luggage tags collected from different airports. From a distance, the large initials on each tag instantly convey a global urban experience—BRU, OSL, SAO, TYO. Up close, the tags have all the technical detail and complexity required for tracking luggage. “The rich texture of many posters comes from the printing process or from building up complex forms out of tiny graphic elements,” Lupton said.

The exhibit’s curators came up with the 14 principles after studying the entire body of work at their disposal. The concepts aren’t exactly universal, but they encapsulate a broad range of methods for approaching a design problem, Lupton said. One example she points to are diagonals. Victorian-era posters largely used centered type, which dragged down the overall layout. Then modern designers made a simple, but surprisingly effective change, using diagonal lines and compositions to create depth, motion, and direct the viewer’s eyes.

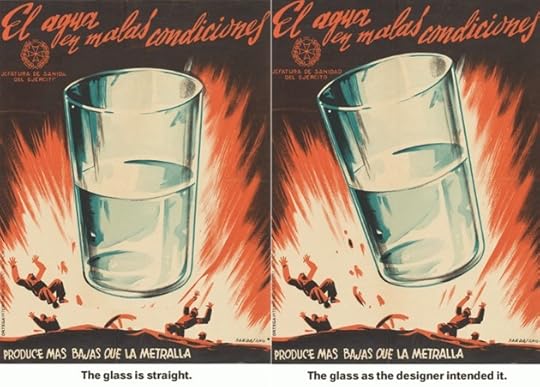

José Bardasano Baos (Spanish, 1910–1979) for Army Health Service (Spain). El agua en malas condiciones produce mas bajas que la metralla [Poisoned Water Causes More Casualties than the Shrapnel], 1937. Lithograph. Collection Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of William P. Mangold.

José Bardasano Baos (Spanish, 1910–1979) for Army Health Service (Spain). El agua en malas condiciones produce mas bajas que la metralla [Poisoned Water Causes More Casualties than the Shrapnel], 1937. Lithograph. Collection Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of William P. Mangold. A Spanish Civil War poster, for example, designed by José Bardasano Baos features a giant glass of water canted at a diagonal. (The poster promotes the democratically elected government's success in improving public hygiene in Spain.) “This poster would be so boring if the glass were straight instead of angled, so I made an animated gif to demonstrate this simple transformation,” Lupton explained. “Of course, any physics-minded viewer will notice that the water in the angled glass should be parallel with the ground plane. The designer created dynamism in the poster but ignored the laws of gravity!”

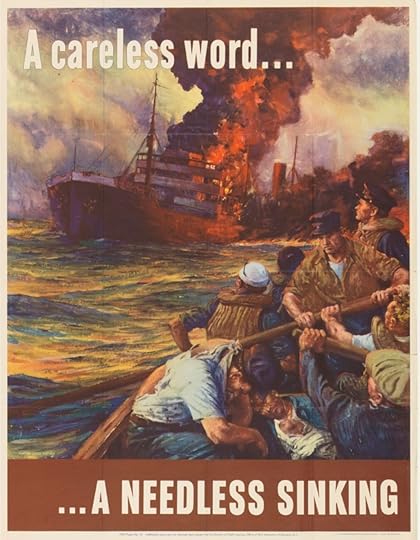

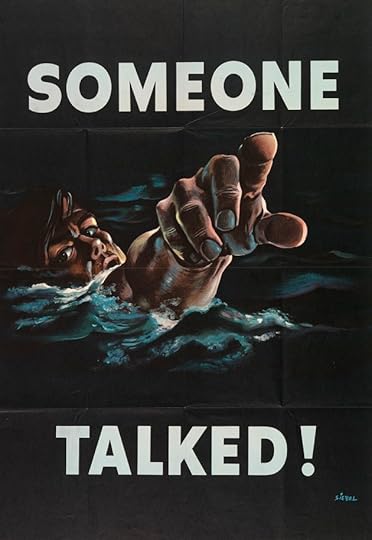

Digging through the Cooper Hewitt’s collection, Lupton discovered lost treasures, like a pair of World War II posters published by the U.S. Office of War Information. Both posters sought to discourage soldiers and civilians from idle talk about troop movements, because such chatter could fall into enemy hands and cause Allied ships to sink. One poster offers a more detailed narrative of a sinking ship, while the other uses a single, striking image of a sailor about to drown, with just the headline “Someone talked!” It’s works like these that prove the value of posters in a design context—but that also crystallize the format’s place in the history of commercial, political, and public life.

Anton Otto Fischer (German, active USA, 1882–1962) for the Office of War Information (Washington D.C., USA). A Careless Word, 1942. Lithograph. Collection Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Unknown Donor.

Anton Otto Fischer (German, active USA, 1882–1962) for the Office of War Information (Washington D.C., USA). A Careless Word, 1942. Lithograph. Collection Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Unknown Donor.  Frederick Siebel (American, Austrian, and Czech, 1913–1991). Someone Talked!, 1942. Lithograph. Printed by Devoe & Reynolds Painting Company (USA). Gift of Louise Clémencon.

Frederick Siebel (American, Austrian, and Czech, 1913–1991). Someone Talked!, 1942. Lithograph. Printed by Devoe & Reynolds Painting Company (USA). Gift of Louise Clémencon.

Why the Massive Air-Bag Recall Won't Make Driving Much Safer

On Tuesday, the air-bag manufacturer Takata announced that it would be expanding a previous product recall to include some 34 million American cars, which is the largest automobile recall in history. Anthony Foxx, the Secretary of Transportation, responded with hyperbolic determination: “We will not stop our work until every air bag is replaced.”

If he and his colleagues stick to that rule, they will never retire.

It’s a victory for consumer welfare whenever a large company is held accountable for products that turn out to be harmful, but Takata’s recall of its potentially explosive air bags shouldn’t bring a lasting peace of mind, considering that one out of every seven U.S. cars has been recalled but not repaired. The reality is that no matter how far-reaching an automotive recall is—and this one is quite far-reaching, affecting 11 different manufacturers—millions of demonstrably unsafe cars will remain on the road. In fact, one of the most recently reported Takata-associated deaths was in a 2002 Honda Accord that was recalled in 2011 but never taken in.

This is the narrative arc of the American automotive recall: Isolated deaths are reported and faulty parts are suspected. Years later, a recall is issued, the media covers it, and an investigation uncovers a higher death count. Lawsuits trickle in. Eventually, the stories fade from the headlines, and many people keep on driving their recalled cars.

The tale of the Takata recall will likely be no different. Replacing even a portion of the affected air bags is complicated and will likely take years. Takata has said it can manufacture millions of replacement air bags a year, but makes no assurances about being able to make tens of millions. And in a twist reminiscent of the credits of Monty Python and the Holy Grail, the administrator of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration acknowledged the possibility that eventually, the replacement air bags might themselves need to be replaced. On top of all that, air bags are embedded in a complicated system of sensors that is difficult and costly to work around in the repair shop. George Hoffer, an economist at the University of Richmond, suggested in some cases that it could be cheaper for companies to buy back a car instead of repairing its air bags.

The reality is that no matter how far-reaching an automotive recall is, millions of demonstrably unsafe cars will remain on the road.And even if the repair processes somehow went off without a hitch, it’s not clear that the Takata recalls will bring in more drivers than the usual disappointing numbers. The more-severe drivers perceive a defect to be, says Hoffer, the more likely a recalled car is to be taken in. He thinks the possibility of explosive air bags and flying shrapnel might induce a higher rate of repair. On the other hand, Hoffer says, older cars and foreign cars are less likely to be brought in, and the affected cars are relatively old and mostly foreign. (Hoffer maintains, as he has for years, that manufacturers could increase repair rates by offering small perks, such as free oil changes.)

If auto manufacturers are occasionally making products that put lives at risk and consumers often don’t do anything to replace them, what can be changed? Not much, it appears—these are two unavoidable features of being a car-loving nation. Hoffer isn’t convinced that there would be fewer recalls if production were more closely scrutinized, because manufacturers and suppliers are being held liable for products that are expected to last longer and longer. “As these complicated technological wonders age,” he asks, “how will they perform?” A decade after being manufactured, many of these parts will naturally start to fail, and it’s hard to design them to be safer without wildly increasing costs.

Hoffer thinks recalls will only become more common as cars are made with more electronic components. “When things were mechanical, one had more warning and they were easier to fix,” he says.

So far, Takata’s air bags have been linked to six deaths. These preliminary estimates tend to grow over time; General Motors’s faulty ignition switches have been said to have caused more than 100 deaths, but at first that number was 13.

Those deaths are tragic, they’re awful, they’re avoidable, and they deserve to be less than statistics, but some context might change the way conventional coverage of recalls looks. The two biggest recalls of the past year (GM’s and Takata’s) have probably been responsible for a couple hundred deaths over the course of about a decade. But in the past year, more than 30,000 people have died in traffic accidents. That means that it’s likely that during the average two-week period, more people are dying in car crashes than have died from the past decade’s recall-related product failures. Two significant determinants of traffic fatality rates are highway-patrol funding and the sales tax on alcohol—not faulty car parts.

Traffic deaths occur with astounding regularity. Without a distinct event, a press release, or a widely-covered announcement to accompany them, transportation secretaries don’t have an opportunity to comment on them and newspapers can’t seem to find an occasion to report on them. As a result, the public can’t seem to be bothered by them.

What Will Bobby Jindal's 'Marriage and Conscience Order' Actually Do?

The late Earl Long was governor of Louisiana, on and off, for more than a decade. “Uncle Earl” was a colorful, corrupt, and bizarre figure, even for the Pelican State; but “[s]omewhere along the line,” his lieutenant governor, William Dodd, wrote, “Earl Long changed from an amateurish shoe-polish salesman and political camp follower into a sound businessman and excellent government administrator.”

Louisiana’s present governor, Bobby Jindal, entered office as a capable administrator and seems determined to leave it as an amateurish salesman.

Jindal on Monday announced an exploratory committee to prepare for a presidential run. (Why not? All the other kids are doing it.) The next day, he issued a remarkable document, Executive Order BJ-2015-8, the “Marriage and Conscience Order.” The order was released just hours after a committee of the Louisiana Legislature defeated the “Marriage and Conscience Act,” HB 707, a bill designed to protect anyone in the state who acted “in accordance with a religious belief or moral conviction about the institution of marriage”—in other words, who discriminated against same-sex married couples. Its protections covered, for example, state contractors who might discriminate against employees in same-sex marriages; licensed professionals, such as doctors, who refuse to provide services to same-sex couples; and businesses that refuse to accommodate same-sex couples.

Indiana and Arkansas earlier this year passed much milder bills that would have had similar effects. After the business community, the NCAA, and Walmart spoke out against them, both states rewrote the laws to make clear that they didn’t do what HB 707 explicitly said it would do.

Similar voices weighed in on HB 707. IBM sent Jindal a letter warning that “IBM will find it much harder to attract talent to Louisiana if this bill is passed and enacted into law." Stephen Perry, the head of the New Orleans Convention and Visitors Bureau, issued a statement saying that the bill “has the possibility of threatening our state's third largest industry and creating economic losses pushing past a billion dollars a year and costing us tens of thousands of jobs."

Related Story

The 2016 U.S. Presidential Race: A Cheat Sheet

That kind of warning may have frightened off Indiana Governor Mike Pence and Arkansas Governor Asa Hutchinson, but Bobby Jindal is made of sterner stuff.* “I have a clear message for any corporation that contemplates bullying our state,” he wrote in a New York Times op-ed. “Save your breath.”

It turns out he didn’t speak for the legislature, however; a committee voted to bury HB 707. Within hours, Jindal had issued an executive order that sounds as if it does what the bill would have done.

Its effect is far from clear. The Democratic speaker pro tempore of the Louisiana House dismissed the order as “overreaching and more than likely unenforceable.” Perry, of the Convention Bureau, said it was “largely a political statement” that “will have very little practical impact.” The new order, in fact, seems likely to achieve very little—except what Jindal, who vacates the governor’s office next January, plainly wants. It puts Louisiana firmly on record as a place same-sex couples, and their families and friends and employers, should avoid, for work or play.

As The Washington Post has pointed out, the executive order seems at a minimum like hypocrisy—Jindal denounced Obama’s enforcement of an existing statute, the Immigration and Naturalization Act, as “an arrogant, cynical political move.” As I’ve noted before, however, executive-power hypocrisy is a bipartisan political pandemic. What’s more remarkable is that the governor has designated Louisiana an official discrimination zone, even though he has almost no power to do so.

The executive order says that religious freedom is of “preeminent importance,” but it explains that freedom extends to only one kind of belief: that of any “person” who “acts in accordance with his religious belief that marriage is or should be recognized as the union of one man and one woman.” It then quickly adds that “this principle [should] not be construed to authorize any act of discrimination.”

The rejected bill said the same thing; but what it provided—and what the executive order purports to provide—was that state government could not take any “adverse action” against anyone who did commit an “act of discrimination”—not even scold them. That’s not authorization for discrimination; it’s impunity for discriminators.

But unlike the legislature, the governor has relatively limited power to actually change state law—much less Article I, Section 3 of the state constitution, which provides that “[n]o person shall be denied the equal protection of the laws;” Section 12, which forbids “arbitrary, capricious or unreasonable discrimination based on . . . sex;” or Article II Section 2, which says that no official of one branch “shall exercise power belonging to either of the others.”

Much of Jindal’s executive order is actually occupied with rather mild-mannered suggestions to state agencies. To begin with, the order notes that Louisiana’s current Religious Freedom Restoration Act, passed in 2010, reads as if it covers only individuals and tax-exempt religious organizations. But, says the order, the Supreme Court interpreted the federal RFRA to cover Hobby Lobby Stores, a for-profit company; other Louisiana-state laws cover corporations as “persons”—would it be such a big deal for the state to pretend that its RFRA does the same?

The order next says that government “should” take “no adverse action” against those who reject same-sex couples; that covers revoking tax-exempt status for charities, penalizing state contractors or licensed professionals, or “deny[ing] or withhold[ing] ... any benefit” under state programs.

Any first-year law student, however, knows that “should” is not “shall,” because the governor can’t singlehandedly change the statutes under which state agencies run. He does say that state agencies are “authorized and directed” to interpret existing law to protect for-profit corporations, to read into the state RFRA a rule that religious discrimination against same-sex couples is permitted; but that doesn’t mean they have to—especially because he is not even in charge of legal interpretation. That job that belongs to Louisiana’s “chief legal officer,” the elected attorney general, James D. “Buddy” Caldwell. Caldwell’s office has not issued an opinion on the order, and a spokeman Wednesday would say only that “[i]t would be inappropriate for the office to provide legal analysis on a matter that . . . may be subject to litigation.”

Bobby Jindal isn’t crazy, but he has been acting a bit strange.It’s certainly not harmless; it may provide cover for some wretched jack-in-office somewhere in Louisiana to proclaim his or her private, homophobic state policy. But its major effect will likely be political. It may, perhaps, provide some boost to Jindal’s presidential campaign, meaning that JINDAL ‘16 will get nowhere faster than it otherwise would have.

Earl Long is the first governor of Louisiana I can remember. The whole country was electrified when, during Long’s last term, some of those around him determined that he would be happier in the state psychiatric hospital in Mandeville. Long was hustled off to a private room, but he eventually fired the hospital director and walked out the door.

Bobby Jindal isn’t crazy, but he has been acting a bit strange. He came to office the object of high hopes: a Rhodes Scholar, a health-policy wonk, and an intellectual who for a time headed the state-university system. He seemed like a rising star that heralded the dawn of a new, diverse Republican Party. “We’ve got to stop being the stupid party,” he said only two years ago.

Now his public proclamations are of impending doom for Christianity, and the peril of sharia law. Ambition can do strange things to even a powerful intellect. Jindal, now one of the least-popular governors in the country, seems a bit like Captain Ahab in Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. Obsessed with tracking the White Whale, Ahab smashes the quadrant he needs to navigate.

“Old man of oceans!” muses his first mate, Starbuck. “Of all this fiery life of thine, what will at length remain but one little heap of ashes!”

A Win for Progressives in Philadelphia

Is there a rising progressive tide in the Democratic Party? Liberals like to claim that there is. But beyond the recent elections of two vocal populists—Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and New York Mayor Bill de Blasio—there hasn't been a whole lot of evidence to point to. Indeed, in two of the most hyped challenges to centrist Democratic officeholders—the recent primaries of New York Governor Andrew Cuomo and Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel—the left has come up short. And things aren't looking much better for Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders in his left-wing challenge to Hillary Clinton.

On Tuesday, though, progressives scored a victory. The Democratic primary for Philadelphia mayor pitted a crusading left-winger against a charter-school advocate backed by suburban hedge-fund magnates. This time, the left-winger, a former city councilman named Jim Kenney, actually won. Given the city's overwhelmingly Democratic tilt, the primary is likely to decide the election.

Kenney ran on a de Blasio-esque platform of establishing universal pre-K, raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour, and ending stop-and-frisk police tactics. (Kenney, a 57-year-old Irish-American, also epitomizes the classiness and tact for which Philadelphia sports fans are famed: In December, he called New Jersey Governor Chris Christie "fat assed" and "a creep" for sitting in the Dallas Cowboys' box at an Eagles game.) On Monday, de Blasio endorsed Kenney, saying the two shared a "progressive vision." Kenney’s campaign was outspent many times over by supporters of his chief rival, Anthony Hardy Williams, a state senator who was backed by a $7 million super PAC. But on Tuesday night, Kenney took 56 percent of the vote.

The Kenney-Williams divide typifies the current split within the Democratic Party between those who style themselves "pro-business" and those who emphasize remedying income inequality. It's a conflict that's also currently playing out on Capitol Hill, where President Obama is in an increasingly acrimonious dispute with the majority of congressional Democrats over a Republican-backed trade-authority measure. The split has echoes of the 1990s battles between Bill Clinton's Democratic Leadership Council and the party base led by Jesse Jackson.

Education is a major fault line in the current Democratic divide—in Chicago, Emanuel's school policies were a principal driver of the dissatisfaction that forced him into a runoff last month. De Blasio has also been in high-profile fights with New York charter-school advocates, while Obama's stance in favor of education reform has dismayed the teachers’ unions that are a major Democratic Party constituency.

Williams, Kenney's rival, was the author of a state law that created a voucher-like system giving companies tax credits in exchange for student scholarships. The super PAC backing him was bankrolled by three financiers who support free-market education reform. Yet in addition to backing Kenney, Philadelphia voters on Tuesday also approved an advisory ballot question seeking to return public schools to local control. Kati Sipp, director of Pennsylvania Working Families, a union-backed liberal coalition, declared the primary "a big win for public education," adding, "Money men tried to buy this election, but they failed."

Liberal activists say Kenney's election is further proof that the center of the Democratic Party is indeed moving leftward—a trend that Clinton, even without a serious primary challenger, will have to grapple with in 2016. Also Tuesday, the city council in Los Angeles voted to raise that city's minimum wage to $15 per hour. "The energy in the Democratic Party is on the left," Anna Greenberg, Kenney's pollster, told me. "It's coming from the urban centers, and that's where Democratic votes come from."

May 20, 2015

After the Waco Shootout, Texas Lawmakers Debate Gun Laws

Authorities are still working to develop a clear picture of the bullet-riddled scene where nine members of biker gangs died in a shootout in Waco, Texas. Reports describe a chaotic fight that started in the bathroom of the bustling Twin Peaks restaurant, then escalated into a parking-lot brawl involving knives, brass knuckles, and guns. By Monday, 170 bikers had been arrested on murder-related charges and held with million-dollar bails. Autopsy reports released Tuesday indicated that all nine of the men killed were victims of gunshot wounds. As it happens, the gun fight coincides with the likely passage of a legislative initiative to loosen gun laws in Texas.

On Monday, deliberations over a bill that would allow for the open carrying of handguns in Texas went on as scheduled in the state’s Senate. Lawmakers offered support for the measure, which has already passed Texas House. “This bill does not have anything to do with what went on yesterday," a state senator remarked. This sentiment was echoed by others, including Texas Governor Greg Abbott, who told the AP on Monday: "The shootout occurred when we don't have open carry, so obviously the current laws didn't stop anything like that.”

Several witnesses who spoke to the bill on Monday did draw a connection between the open carry bill and Sunday’s bloodbath, the Texas Tribune reported. Austin Assistant Police Chief Troy Gay “told senators that the ‘chaotic situation’ in Waco could have been made much worse by the confusion an open carry law would bring to responding police officers.”

The law would bring handgun policy in Texas into line with the majority of states. Forty-four other states currently allow some form of open carry. A Dallas Morning News analysis from earlier this month illustrated a decades-long evolution among Texas lawmakers on the issue: In the 1990s, opponents of looser gun rights laws attached open-carry amendments to gun legislation “in an effort to sink the bills,” the Morning News pointed out. “Some Republicans, fearful of just that result, said open carry was unnecessary.”

Now, supporters of the pending open carry legislation point to the 90s as an indication that predictions of increased violence from loosened gun laws are overblown. In 1995, then-Governor George W. Bush signed a concealed carry bill into law. Firearm homicides in Texas declined 30 to 40 percent in the ensuing decades.

Among Texas law enforcement, opposition to an open carry law is not new. Prior to Sunday’s shooting, Texas Democrats frequently invoked police opposition to allowing concealed weapons, not only because of the confusion factor, but also for fear that the guns would “fall into the wrong hands.”

Another bill, which would require public colleges in Texas to permit concealed weapons on campus, is also close to passing, although it’s currently stalled in the legislature. Many school officials are not fond of the idea.

Why Congress Can't Solve America's Infrastructure Crisis

Congress does many things poorly, but there are few issues it has handled worse in recent years than providing funds for transportation and infrastructure. That’s not a point you’re likely to hear either Democrats or Republicans contest.

On Tuesday, the House passed a two-month extension of the Highway Trust Fund, which is set to expire at the end of the month. The stopgap measure would prevent a damaging shutdown of infrastructure projects across the country, but as lawmakers spent an hour debating the bill, all they could talk about was failure. Despite bipartisan agreement that the nation needs a long-term program to repair and replace its aging roads, rails, and bridges, Congress has been plugging the trust fund like a driver who refills his gas tank one gallon at a time.

Related Story

How Red States Learned to Love the Gas Tax

“We have known for months that this day was coming, and we have made no progress,” lamented Representative Jerrold Nadler, a New York Democrat. Minnesota’s Rick Nolan called the situation “a national embarrassment,” while a third Democrat, Lois Frankel of Florida, said the 60-day patch was the equivalent of slapping silly putty on a cracked bridge. Republicans, whose districts contain just as many creaky overpasses and congested highways, complained about the extension in only slightly less dire terms. Senator James Inhofe, the Oklahoma Republican famous for his denials of climate change, told the Huffington Post that his own party was to blame for the absence of a long-term solution and said a “true conservative” would support federal spending for roads and bridges.

The deadly crash of an Amtrak train last week outside Philadelphia cast an even brighter spotlight on the nation’s infrastructure woes. While the cause is still under investigation, Amtrak has pushed for more funding for years. The passenger railroad says it needs as much as $20 billion to dig new tunnels under the Hudson River and upgrade its rail lines. Just a day after the crash, House Republicans, who have been critical of the money-losing railroad’s management, voted to cut Amtrak’s budget by $260 million—a move that drew howls of protest from Democrats.

“We have known for months that this day was coming, and we have made no progress.”Both parties want to pass a plan to provide funding for surface transportation projects for up to six years, but they are stuck—and have been for a long time—on how to pay for it. The federal gas tax finances the Highway Trust Fund and hasn’t gone up in more than 20 years, but Republicans and many Democrats refuse to raise it, even as many red states have recently done so on their own to fund their transportation needs.

The most popular alternative at the moment is to use revenue generated by taxing repatriated earnings that U.S. companies now keep overseas. But there is disagreement over the details of that proposal, and Republicans believe it would only work if included in a broader tax-reform plan—an even heavier political lift. In fact, the reason Congress is reauthorizing the Highway Trust Fund for just two months is because lawmakers couldn’t agree on how to fund it for the remainder of the year, let alone for the rest of the decade. It has enough money to last through July, and Republicans are reluctant to simply transfer more money from the Treasury’s general fund, as they have done in the past. As a result, Congress probably will have to pass yet another extension this summer, which would be the third in the last year. A highway bill lasting for more than two years hasn’t passed on Capitol Hill in a decade.

The stopgap funding is bad, advocates say, because the biggest infrastructure projects can takes years of planning, and states won’t start them without knowing how much money they’ll get from the federal government. Industry officials estimate that $2 billion in projects have already been pulled back so far this year because of the inaction in Washington. “There is a real effect if we don’t do something,” said Brian Pallasch, managing director of government relations at the American Society of Civil Engineers, which gave the U.S. infrastructure system a D+ in its most recent quadrennial report card.

The Obama administration has proposed a six-year, $478 billion plan called the Grow America Act that would pay for infrastructure by imposing a 14 percent tax on foreign earnings being held overseas by U.S. companies. Republicans would also use repatriation as a revenue source, but their proposals have called for a far lower rate, and there is broader skepticism of whether the idea would really generate enough money. “It does not provide us that long-term, sustainable source of revenue,” Pallasch said. “It really is a one-time shot in the arm.”

Over the last several months, a few Republicans have stepped forward to endorse an increase in the gas tax, including Inhofe and Representative Jim Renacci of Ohio. Yet the party leadership has ruled it out as an option. Outside groups are now hoping Congress will turn to a method of payment that, until recently, had gone out of style: deficit spending. Nick Yaksich, a vice president at the Association of Equipment Manufacturers, noted that Congress recently approved a major change in Medicare financing that was only partially offset by new revenue and entitlement changes, with the rest going on the national credit card. “Why can't there be a similar path forward on a six-year highway bill?” Yaksich asked. With deficit mania having died down, lawmakers may well come around to that idea—but probably not before punting a few more times first.

May 19, 2015

L.A. Becomes Largest City to Boost Minimum Wage

Today’s vote to raise Los Angeles’ minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2020 is being called “the most significant victory so far” in the push to increase the minimum wage nationally. The City Council passed the ordinance 14-1, which will boost the current minimum of $9 in roughly $1 increments annually over the next five years. The first increase would happen in July 2016, boosting minimum wage to $10.50 an hour.

The response hasn’t been completely positive. While labor unions and supporters of the wage increase are displeased that the ordinance will take place piecemeal over 5 years, small business owners—who have until 2021 to comply—complain that the nearly 50 percent increase will hurt their bottom line.

“The impact of the council’s endorsement of a $15 minimum wage is huge. Analysis of a similar earlier proposal, raising the rate to $15.25 by 2019, found that more than 600,000 workers—over 40 percent of the L.A. workforce—would ultimately benefit from the increase,” says Christine Owens, executive director of the National Employment Law Project, in a statement.

The bill in its current form includes tipped workers—meaning that tips would not count towards the proposed minimum-wage base pay of $15. Currently California is one of seven states that include tipped workers among regular minimum wage workers, and they too would benefit from the pay bump. But restaurant industry representatives have expressed concern, namely that they expect some restaurants with thin margins to close once higher-wage standards kick in.

The question of whether cities should have different minimum wage than states or the nation has been an ongoing one. The trend has picked up popularity since Santa Fe and San Francisco enacted a higher wage than the federal minimum in 2003, with six major cities increasing wages to above the $10 mark in the coming years.

Councilman Paul Krekorian remarked: “Today the City of Los Angeles, the second biggest city in the nation, is leading the nation.”

In New York, Governor Andrew Cuomo has sought to increase the minimum wage for fast-food workers while Mayor Bill De Blasio has called for minimum wage to be raised to $15 by 2019. Nationally, congressional Democrats are looking to increase minimum wage to $12 by 2020.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower