Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 408

June 21, 2015

When Do Multicultural Ads Become Offensive? Your Thoughts

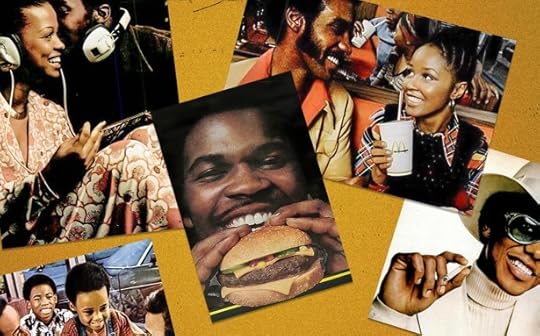

As part of The Atlantic’s “Selling the Seventies” series, my colleague Lenika Cruz recently explored the moment in the early 1970s when major companies began marketing directly to African Americans. The resulting debate in the comments section revolved around a central tension in the ad industry: How to connect with demographics without stepping on stereotypes. Regarding the ads featured in Lenika’s piece, mostly from McDonald’s, commenter JohnJMac facepalms:

My God, these commercials are hysterical. It’s a parody of what a bunch of white Mad Men would conceive, having spent a weekend watching movies starring Pamela Grier.

Benson Stein says of the early ‘70s, “This was the era of blaxploitation films such as Blacula, Shaft, Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song, so I could see this spilling over into mainstream advertising.” UrbanRedneck2, on the other hand, shrugs:

I don’t get the problem. The ads were showing African Americans dressed in the way they often did back then and also showed how many of them talked. So what’s the problem? Why does every advertisement have to be sanitized and one size fits all?

KlugerRD points to a part of the story that’s missing:

(Courtesy of Tom Burrell)

You get the impression from the article that the normal white-populated agencies did these McDonald’s ads. Wrong.

In 1971, Tom Burrell started his own ad agency in Chicago called Burrell Communications. Tom was an African-American guy who began a trend with agencies specializing in creating advertising targeted at African Americans. He began with accounts like Coca-Cola, Philip Morris, and McDonald’s. So it’s very likely the ads you showed were done by Burrell or another African-American agency.

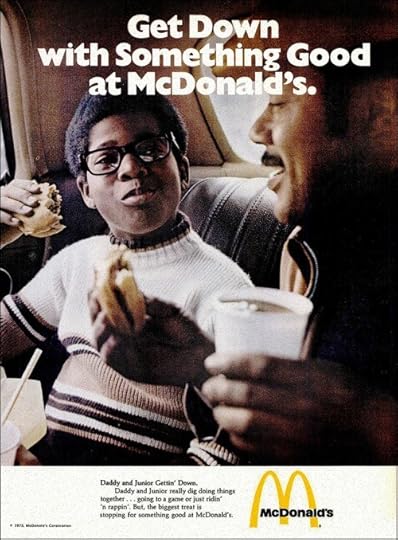

I reached out to Tom Burrell and he confirmed that those McDonald’s ads were indeed from his agency. He also mentioned that his founding partner, Emmett McBain, submitted a bunch of prints to the Smithsonian back in 1985, so I ventured down to the archives of the National Museum of American History to check them out. (Coincidentally, the museum is about to open a big new exhibit on business history that includes “marketing campaigns targeted to diverse audiences, including teens, African Americans and Latinos.”) Here’s one of the prints from the McBain collection:

As awkward or even offensive as that copy might look today, did it offend black people at the time? Lowell Thompson, an African-American adman since the early ‘70s who worked at Burrell Advertising and helped Burrell on his book, appeared in our comments section to shed some light on the question:

What seems so lame and stereotypical to EurAmericans here in 2015 seemed much less so to AfrAmerican in 1970. Most AfrAmericans were happy to be recognized as thinking, buying human beings after over 300 years of being “branded” as subhuman beasts. (I’m working on a book, “Mad Invisible Men & Women,” that chronicles the history of “black” images and image makers in America.)

Commenter Valyrian Steel suspects the McDonald’s ads were successful:

The purpose of an ad campaign isn’t to fit the sensitivity rubric of a professor’s race, class, and gender seminar 40 years into the future. Ads exist to sell product. So the article omits the most important and interesting info: Did these campaigns (no matter how clumsy) increase revenue in the demo? Given that McDonald’s has far more locations, market share, and revenue than any other restaurant on Earth, I suspect the ads worked extraordinarily well.

They did, according to Madison Avenue and the Color Line, Jason Chambers’s history of African Americans in the ad industry:

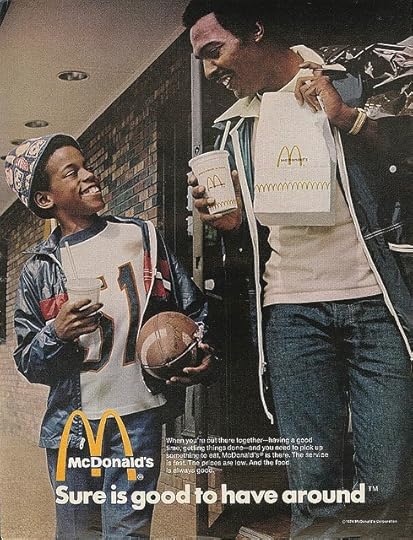

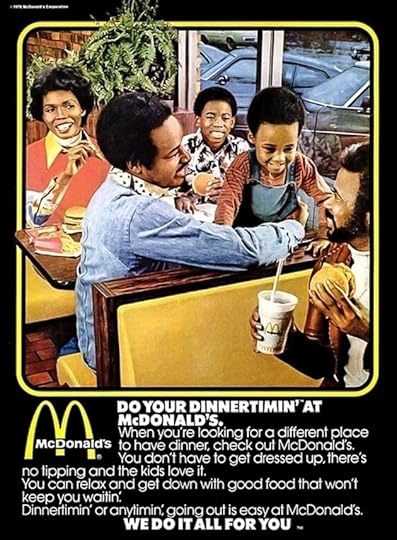

After studying the slogan for McDonald’s [in 1971], “You deserve a break today,” Burrell decided it was ineffective in reaching blacks. He believed the theme presented McDonald’s as being a “special treat” that families used sporadically. In contrast, his research suggested that McDonald's restaurants were a part of many blacks’ daily experience. Therefore the idea that the restaurants were only useful when one needed or wanted a break was meaningless to blacks. In place of the original slogan, he suggested the theme “McDonald's is good to have around” for the black consumer market.

The new slogan and accompany advertising campaign were a hit among black consumers. From that point onward, McDonald's remained one of the agencies largest clients.

I asked Burrell to respond to the critiques of his McDonald’s ads from Professor Charlton McIlwain and adman Neil Drossman, who were quoted in Lenika’s piece:

“Cynical”? “Superficial”? All of these comments take me from confused to incredulous. Are you sure they’re referring to Burrell’s advertising? The comments have me bewildered because, after making critical comments about the McDonald’s ads, both go on to speak of general market agencies. I say “incredulous” because I can’t believe commercials like "Daddy’s Home”, “First Glasses”, “Joey”, “Double Dutch” [seen below], "Counting Fries,” “Family Reunion”, “Calvin” and countless other classics could be perceived as negative, cynical and shallow.

Our agency has been consistently heralded by consumers, corporations, community and trade organizations for the respect with which we address the African-American consumer. So I’m more than a little confused by the criticism. I’m also not sure what is being recommended as an antidote to what they perceive to be problematic.

[Ed. note: This Coke ad from Burrell in ‘76 won him his first Clio, the industry’s version of an Oscar:

I am sure we, on occasion, might have been less than perfect, but we also know the following from years of research during my 32+ years in charge:

Our work has been very successful in creating work that makes our target feel good about ourselves and our culture. [This approach is called “positive realism.”] That black people are not dark-skinned white people; we came on the American scene in a totally unique way: against our will and enslaved. And we know that those circumstances led to the formation of unique consumer attitudes and behavior patterns. That our work was instrumental in enhancing the image, sales and brand loyalty for our clients.

Drossman emails a response to Burrell:

I said I thought those three McDonald’s ads [one seen to the left] were cynical and superficial. Little bit a sterotypin’ goin’ on there, no? I still think that. Listen, we all get up to the plate and strike out every now and then. In no way was this an indictment of Burrell Communications. I didn’t even know who did those ads. But I thought they were representative of the tone deafness of the times.

I have seen a lot of your work and there’s much to be proud of there. And you have the awards and accolades to show for it. What’s more, agencies like yours were pioneers in their efforts to reach the African-American market, an underserved market, given short shift by the mainstream agencies of the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s. My view is that it wasn’t a sea change, maybe just a puddle change.

McIlwain also believes the ‘70s “did not live up to those bold intentions” of Burrell and other ad pioneers:

On the one hand, black folks for the first time began seeing themselves in television advertising. For folks who had been so invisible for so many years, to look and say “hey, I see myself on that screen.” That was significant.

On the other hand, people viewing advertisements rarely know the personalities and circumstances behind the production. They take the ads at face value.

Here’s Burrell one more time:

The “casualization" of the English language, while strongly associated with black culture, came into being long before the ‘70s, and it goes far beyond the black race. G-dropping? If I recall correctly, there were lily-white ditties like “Puttin’ on the Ritz,” “Doodlin’,” “Makin’ Whoopee,” “Goin’ Fishin’,” “Moanin’,” “Nothin’ says lovin' like somethin’ from the oven,” “Hey, Good Lookin', whatcha got cookin’?,” “S’posin',” “Singin’ in the Rain,” etc.

So let’s dispel the specious notion that g-’droppin’ was created in the ‘70s to reach black consumers. It all came down to attempts (admittedly occasionally failed) to warm up what had been a stilted or non-existing relationship between the advertiser and black consumer.

For more on the history behind Burrell’s work and others’, be sure to check out Planet Money’s recent episode “This Ad’s For You.” Back to our readers, KoreanKat makes some good points:

While it is interesting to analyze these ‘70s ads, it invites the overcompensating leftist reflex to denounce them disproportionate to their historical distance and context. It’s also important to remember you can’t please everyone. If advertisers depict minority persons reflecting mainstream culture, I can see the same ______ Studies professors inveighing about how it is “white washing” diversity.

The Acedian points a finger at the media:

I’ve a feeling that younger journalists have no real connection to the eras they’re writing about and feel everything from a bygone era was “racist.” People in urban communities did indeed speak in a certain way, as many U.S. regions tend to have their own vernacular, inflection, and pronunciation, and advertisers were never shy about picking up on that to “speak” to those demographics.

Kwame_zulu_shabazz nods:

Yes, Acedian, I had a similar take. Some of the critique in the Atlantic article sounded like upwardly mobile black “respectability politics.” African Americans in ghettos (I’m from Inglewood) frequently dropped the “g,” so it seems to be the opposite of “tone deaf.”

And marathag doesn’t see the g-droppin’ as anything special: “All advertising is really cynical and nothing but superficial effort to ‘reach’ a targeted audience.” Tom agrees:

Painfully stupid ads aimed at blacks was not the end of it. This era was filled with painfully stupid and overly earnest ads aimed at young people, where everyone said “groovy” and “let’s rap” (in the ‘70s, “rap” meant “talk”) and dressed like a middle-class hippie.

A prime example was easy to find:

A snipe from poolside:

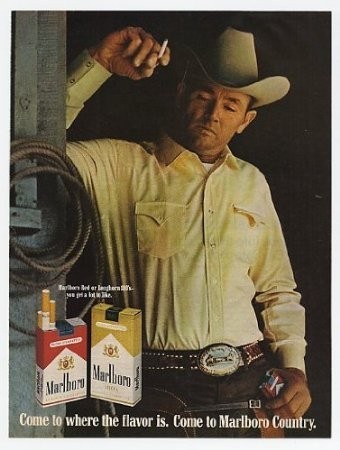

Never seen in The Atlantic: An article about how Marlboro perpetuated “fraught stereotypes” of white Americans by featuring a cowboy on a trail ride.

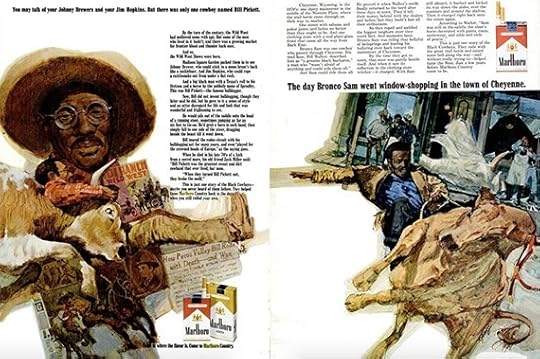

Speaking of Marlboro, Burrell was also hired by Philip Morris in the early ‘70s to develop a “Black Marlboro Man.” The company had already tried to market directly to black smokers but with little success.

Those ads appeared in Ebony magazine in July 1970 and June 1970, respectively, and they featured Bill Pickett and Bronco Sam, two black cowboys from the late 19th century. The ads flopped. Another one I saw in the Smithsonian archives, from 1968, features a standard scene of the Marlboro Man riding a horse juxtaposed with an inset of a formally-dressed black couple lighting a cigarette: “Come to Marlboro Country.” It’s as if Philip Morris just slapped a stock image of African Americans onto an existing ad, and the contrast looks bizarre.

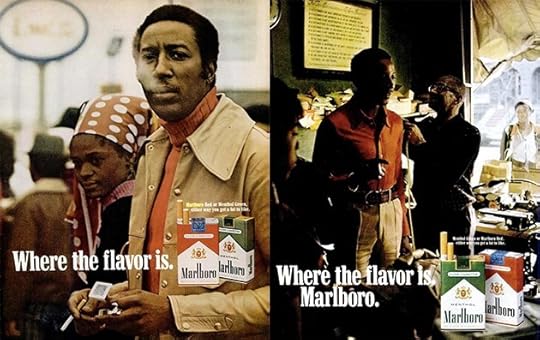

Then, in 1972, Burrell and McBain stepped in. From Madison Avenue and the Color Line:

[Burrell and McBain] argued that, although whites considered the Marlboro Man a “hero,” blacks considered him a “loser.” Research suggested that blacks defined manhood as “a man who took charge of family, lived in the city, [and] was involved with people in a responsible role.” Where the cowboy was an individual, a black man was with his family or friends; where the cowboy was alone, a black man was active in his community.

Therefore blacks’ definition of manhood was an almost complete reversal of that of both the white and black individualistic cowboys prevalent in Marlboro ads. The advertisements created by Burrell and McBain [...] featured a black man as the central figure, located in urban settings, involved with his community, and on the move.

Two examples from the McBain collection:

Another ad in the archives features a “Black Marlboro Man” with an Afro browsing a sidewalk sale with a female companion in a head wrap. Another ad shows a similar man buying fruit from an older black gentleman on the street. AdAge acknowledges, “The campaign was able to increase the brand’s market share among African-American males.”

Commenter Sirius Jones fast-forwards:

It’s a huge shame that ads today have gone in the complete opposite direction as the early ‘70s. Every time there are non-whites represented in advertising they’re always white washed. Advertisers feel as though there is nothing distinct about people of color. They are nothing more than white people who were dipped in paint. You see blacks in advertisements wearing a European suit smiling nicely with his white colleague. You see a black guy wearing a polo shirt watching some white sitcom. POC are treated as white people with no distinct culture.

Diana Mitford responds:

The only solution is to have PoC make their own ads. We need more diversity in the workplace to represent the multicultural place that America is becoming.

Some pioneering examples of multicultural ads were chronicled by Kyle Coward in his recent Atlantic piece, “When Hip-Hop First Went Corporate”:

This 30-second 1994 commercial was part of a campaign for St. Ides, a low-cost, previously obscure brand of malt liquor, that was the first to weave a hip-hop aesthetic into its central messaging.

Today—when Dr. Dre is an Apple executive, Jay-Z has partnered with Samsung on an album release, and Snoop Dogg has appeared in Chrysler commercials—the St. Ides campaign appears strange, a relic from a time when hip-hop culture hadn’t yet earned wider Madison Avenue respect.

“Back then, part of the excitement within the hip-hop subculture, as it still was at that time, was the dawning realization of the potential for hip-hop marketization,” says Eithne Quinn, a senior lecturer in American Studies at the University of Manchester, in the United Kingdom. “Many artists, from poor backgrounds as they often were, didn’t see this as selling out.” …

[W]hat made St. Ides different was that it’s one of the earliest examples—if not the earliest—of a brand with no inherent ties to hip-hop completely building its identity around the genre, entrusting the culture’s tastemakers with its messaging.

A more recent example of entrusting hip-hop tastemakers with ad messaging occurred in 2013 when Mountain Dew hired Tyler, The Creator to write and direct a series of three commercials:

Twitter exploded in outrage, led by Syracuse academic Boyce Watkins, who called the third ad “arguably the most racist commercial in history.” Tyler responded at length:

I guess he found it racist because I was portraying stereotypes, which is ridiculous because, one, all of those dudes [in the line-up] are my friends. Two, they’re all basically in their own clothes. [...] Three, no [commenters] saw that commercial and said, this is racist. Everyone either said, “Wow, this is ridiculous, it’s a goat talking,” or they said, “Wow, this is the dumbest, why would they even make this?” [...]

It’s a black guy making this, and if it’s so racist and feeding into stereotypes, why in the first commercial that goes along with it, is there a black male with his Asian wife? In the second commercial, it’s a black male with a professional job as a police officer listening to hardcore rock music -- which supposedly the stereotype is that black people don’t listen to that.

Can you think of other controversial ads that blurred the line between authenticity and stereotype? Email hello@theatlantic.com and I’ll update the post with the best examples.

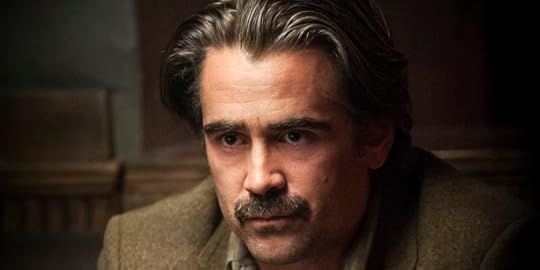

True Detective Season 2: Welcome to Vinci

Each week following episodes of True Detective, Spencer Kornhaber, Sophie Gilbert, and Christopher Orr will discuss the murders and machinations depicted in the HBO drama.

Kornhaber: In 2010, the Los Angeles Times ran a story about the city of Vernon, home of approximately 90 people and 1,800 businesses. “Vernon a tightly controlled fortress,” read the headline, and the article detailed how the tiny industrial town had become a hotbed of alleged corruption, with city officials earning huge salaries, participating in shady commercial deals, and setting residency rules that amounted to vote rigging. Some of those officials lived, according to the Times, “in tidy, wood-frame homes with green lawns tucked hard in a world of gray smokestacks, meat packers, heavy industry, power plants, and transmission lines.”

Related Story

Colin Farrell’s Evolution: From Movie Star to Actor

Sound familiar, watchers of True Detective season 2? In tonight’s premiere, Colin Farrell’s Detective Ray Velcoro emerged from a cute lil clapboard cottage nestled in a metal jungle and then made about a 10-foot commute to the municipal building where he works. The town is called Vinci, but the parallels with Vernon are obvious, right down to the newspaper that’s investigating it. This setting, perhaps more than anything else, is what’s promising about the second outing of HBO’s super-hyped noir miniseries. Early in the episode, a character voiced the essential truth about corruption—“Everyone gets touched”—and the lightly fictionalized city of Vinci, with its refineries abutting homes abutting freeways, already embodies that idea.

The first True Detective featured ravishing filmmaking and a pointless plot, full of sumptuously rendered characters, storylines, and settings that never fit together in a coherent way. It seemed to want to be about how personal struggles intertwine with the wider world, but Rust Cohle’s and Marty Hart’s domestic drama and spiritual speeches didn’t, in the end, have much to do with the murder mystery, and the vast conspiracy they investigated never really materialized on screen. So far, Season 2 is as deliciously moody as its predecessor, but also seems faster-paced and more deliberate. Interconnection—between home and work, sex and ambition, family and society—isn’t just a theme, it’s a plot engine: Farrell’s character moonlights for the city’s crooked business interests and lives on the doorstep of his daytime employer; Rachel McAdams busts her sister’s webcam business and investigates her dad’s spiritual center; Taylor Kitsch stumbles into a murder scene while fleeing his girlfriend; Vince Vaughn and Kelly Reilly conspire in their shared bathroom.

Which doesn’t exactly mean that the plot will be easy to follow. With so many principle characters and interlinking plotlines, viewers will have to take notes as they watch and hope they add up to something more significant than they did last season. Here’s what I’ve got on the major characters so far:

•Frank Semyon (Vince Vaughn): Shady business guy. Appears to have gone from blue-collar crime boss to white-collar one. Working on a lucrative development deal involving high-speed rail and Vinci city manager Ben Caspere. Anxious for investment from Osip Agranov, who appears to be a Russian gangster. Also anxious about the newspaper investigation of Vinci. Not afraid to call in a hit on a reporter. Married to …

•Jordan Semyon (Kelly Reilly): Business partner with her spouse. Looks cool sipping champagne. Has, in Frank’s words, “brains.” The two are trying to have kids.

•Raymond Velcoro (Colin Farrell): Vinci police detective. Previously worked for the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s department for eight years. His wife gave birth to a son nine months after being beaten and raped, before which he and she were supposedly trying to have kids. Frank gave him info on the rapist, and in the time since then Velcoro has become Frank's hired muscle. Drinks hard, angers easily, and might just take brass knuckles to your face if your son bullies his son. Is assigned to investigate the disappearance of Caspere. Is also in a custody battle, and for some reason sends messages to his son using an old-school voice recorder rather than a smartphone.

•Paul Woodrugh (Taylor Kitsch): California Highway Patrol officer. Is put on paid leave after a celebrity lies(?) about him soliciting her during a traffic stop. Has a girlfriend who really, really likes his body, though he needs to take a pill to have sex with her (which maybe is connected to why his coworkers chuckled at the idea of him asking a woman for a blow job?). Was in the army. Was involved in something called “Black Mountain.” Likes riding motorcycles and has wicked scars.

•Antigone “Ani” Bezzerides (Rachel McAdams): Ventura County Sheriff’s officer. Takes on a missing-person case after delivering a foreclosure notice to a woman with a suspiciously large TV. Has capital-I Issues that include: a sexual proclivity that freaks out the guy she’s sleeping with; a love of booze, gambling, and maybe cocaine (“When you walk it's like erasers clapping” says her sis, which could mean a few things); a strained relationship with her free-spirited sister who’s doing webcam porn; and a more strained relationship with a hippy-guru father who did not stop Ani's mother from walking into a river (I think?). Owns a surfboard.

•Ben Caspere: Vinci City Manager. Dead, with eyes removed and a wound to the pelvis. Owned a big house filled with lots of kinky/creepy stuff in it. Had recently hired a new secretary. Visited Sonoma’s Russian River Valley a lot (perhaps of note: Ani’s missing person was headed to Sonoma when she left the Panticapaeum Institute). Was involved with the high-speed-rail land scheme. Was left as a corpse on a road shoulder next to an Adopt a Highway sign that says “Catalyst Group,” the name of a company affiliated with the Semyons.

These characters—angsty, secretive authority figures—are all tropes, yes. But they all seem to have great, juicy secrets. Don’t you want to know more? Of course, this is how True Detective hooked people in Season 1, and the payoff was a flimsy storyline and Matthew McConaughey’s audition reel for Lincoln. One interesting change: In contrast to the blatant sexploitation in the first season, there was no live female nudity in this episode—even in the porn shop, even from Woodrough's seductive girlfriend. It’s a small change, but it might mean that creator Nic Pizzolatto and HBO absorbed some of the criticism they received last year.

Interconnection—between home and work, sex and ambition, family and society—isn’t just a theme, it’s a plot engine.The loss of director Cary Joji Fukunaga and arrival of Justin Lin hasn’t hurt the show’s appeal as cinema, as far as I can tell. Some of the images tonight were gasp-inducing, like when Velcoro put on a ski mask and hushed a crackhead or when a gang of county agents silently closed in on a farm bungalow. Perhaps the overhead shots of snaking roads and belching machinery will soon bore; for now, they’re mesmerizing. The show’s totally straight-faced nature hasn’t changed either—characters might tell jokes, but in general these people are so serious that there are times when it feels like parody. I’m just going to go with it, I’ve decided, and try not to giggle when Taylor Kitsch’s cheeks flap during a nearly suicidal motorcycle ride or Colin Farrell uses the term “butt fuck.”

There’s still a lot to get into. How’d you two like the credits sequence scored by Leonard Cohen, or the episode’s other musical moments? What’s the “Western Book of the Dead”? And is the whole series going to end up being about Ani converting to her dad’s woo-woo philosophy like Rust Cohle finding god?

Gilbert: Whatever Ani’s dad’s philosophy is, his knowledge of Greek mythology is woefully lacking. “Athena, goddess of love,” he purred at his elder child, ignoring the fact that (a) Aphrodite was the goddess of love, (b) Athena was the goddess of war and wisdom, and (c) she was chaste. He named his younger daughter Athena and can’t get the history straight? And then he named his other daughter after Antigone, who was locked in a tomb before killing herself? No wonder she likes knives.

This show is fascinating, and suspenseful, and gorgeous, and artfully made. It is also completely and utterly ridiculous. I have to acknowledge that before proceeding, because it wasn’t enough for Pizzolatto to give his characters metaphorical scars—he had to give them literal ones, at least in the case of Woodrugh, and the waitress who asked Ray why he wasn’t eating his nachos. It wasn’t sufficient to have one character be a hard-drinking, emotionally rabid cop with addiction issues and searing family trauma, which is why we have two (or three, if you count Woodrugh’s love of Viagra and playing freeway games of chicken with himself). And in case anyone was missing the point that these people are FUBARed, that heroin-chic singer in the bar had a whole musical number about it, including the lyrics, “The nights that I twist on the rack are the times that I feel most at home.” The cops are very, very messed-up and self-destructive. Got it.

I hope that I’m wrong, and that something’s going to happen later in the season to subvert the cliché of the tortured officers using their personal gaping wounds to help solve horrific crimes, but then again, the show is called True Detective. So let’s focus on the good. How brilliant was Colin Farrell’s 180 from caring dad to maniacal nightmare? How scary were his eyes when the lawyer asked him if they’d ever caught the man who’d raped his wife? I loved the percussive interludes between scenes where the drums sounded like a beating heart and the freeways looked like veins crossing each other. And it’s wonderful to have a woman be part of the action this season, even if said woman isn’t Oprah, or Blue Ivy, or Rory Gilmore.

This show is dank, and sweaty, and fetid, and teeming with pain—and that’s exactly why we love it.Like everyone else (probably), I googled “The Western Book of the Dead” and still don’t really know what it is, but you can read it here, and it seems to be some kind of mystical hippie tract written in the ‘70s. Essentially, man evolved from matter, found God, lost God, found nihilism, found art, found solace in sex and psychedelic drugs and necrophilia (eek), abandoned morality, and became a miserable, “meaningless, enigmatic, machine-like piece of MATTER,” which about as well describes the state of my workdays as any term I can dream up. The next episode, also directed by Justin Lin, is called “Night Finds You,” so anyone who had hopes that TDS2 might be leaving darkness behind for even a fraction of a second is clearly being optimistic. This show is dank, and sweaty, and fetid, and teeming with pain—a veritable corpse of a drama whose eyes have been chemically removed—and that’s exactly why we love it.

The other thing to note about TD, and one of the things that makes it so fun to unpick, is its attention to detail. Like Mad Men, it’s very much a show of the Internet age, in that every scene has 100 visual elements and throwaway lines that beg to be unpicked. You couldn’t get away with that on a drama a decade ago, before Reddit discussions and comment threads and screengrabs, because the audience would have missed everything. But now, with our ability to rewind and rewatch every scene, we too have become detectives, hoping to find crumbs on a very gory trail. I have no idea why Ani has an entire wall of weaponry in her apartment and reads the Hagakure, or why there were pink ribbons tied to stakes in the episode’s opening scene, or why Ray uses voice recorders to send messages to his son instead of just Facetiming him like a normal deadbeat—albeit sociopathic—dad. But isn’t it going to be fun finding out?

My favorite lines from this episode:

“I am not comfortable imposing my will on anyone, and I haven’t been since 1978.”

“Is that blood on your sleeve?”

“We just had a thing, me and you. Totally, totally my fault.” (Ray has definitely spent some time in parenting therapy but it doesn’t seem to have helped.)

“Ginsberg said this to me once.” (Seriously, what an ass.)

Orr: Thanks to you, Spencer, for setting the scene and establishing the dramatis personae. When we’re dropped into the middle of a show of this complexity, it helps to have a scorecard. You also did a way better job of answering the question posed by Ani’s partner right at the end (“What the fuck is ‘Vinci’?”) than Ray did (“A city, supposedly”). I’d heard about Vernon, but I didn’t realize how closely Vinci was based on the place.

You guys did such a nice job of describing the episode’s major themes this week that I thought I’d opt for a series of mostly narrower observations.

•Regarding the Leonard Cohen-scored title sequence: I like it a lot, but I don’t love it quite so much as the masterpiece that was last season’s—a strong contender for my favorite TV title sequence ever. If I’m not mistaken, it also served as a (looser) model for the opening to HBO’s extraordinary The Jinx. (If you haven’t seen it, trust me: you should.)

•One of the things I like about the new season is the way it conjures last season—which I liked way more than you, Spencer, at least up until that disappointing finale—while still clearly standing on its own. One of the most obvious confluences is the use of those magnificent aerial shots, which I doubt I’ll ever tire of. This season may have exchanged Louisiana bayous for the highways snaking up and down California, but the idea of a landscape being poisoned by human industry (in every sense of the word) is still there. If you looked very closely in the opening scene of the episode, there was even a momentary glimpse of a sign warning “contamination.” (As for those pink ribbons on stakes, Sophie, my best guess was that they were marking an area for future construction. But maybe not.)

•I also loved the way Ray’s house is plunked down feet away from the police department, in the midst of an industrial wasteland—like a noir version of Carl Fredricksen’s house in Up. (All Ray needs to find his way to a happy ending is 10,000 balloons.) Hell, even dead city manager Ben Caspere’s playboy mansion overlooks heavy industry.

•Another of the early pleasures of this new season is the way it digs into the gold mine that is California crime fiction, from Chandler and Hammett through Chinatown and beyond. (It’s probably not a coincidence that Farrell’s character is named “Raymond.”) But by far the strongest echo for me is to James Ellroy, and in particular to his L.A. Quartet. Three intersecting cops—one of them also a crook, two of them drunks, and all three screwed-up sexually; the tragic family pasts (a mom’s suicide, a wife’s beating and rape, whatever the hell accounts for Paul’s scars from “a long time ago”); the omnipresent whiff of sexual depravity. (Did you notice the mayor ostentatiously groping his wife’s ass in public?) You’re right that it’s overkill, Sophie. But it’s also so very, very Ellroy.

•I also spotted (or perhaps, in a case or two, imagined) several little crime-cinema Easter eggs scattered throughout the episode. Frank’s response to Ray after he gives him information about his wife’s assailant—“Maybe we’ll talk some time. Maybe not”—seems like a pretty clear updating of Don Corleone’s “Some day, and that day may never come” under nearly identical circumstances (vengeance for a daughter, not a wife) in The Godfather. I don’t think I’ll ever again hear a door-chime like the one at the bar where that scene takes place and not think of Holsten’s in the finale of The Sopranos. It may just be me, but that brief glimpse of a bird-of-prey head(???) in the passenger seat of the car that drove Caspere to his (not final) resting place certainly conjured thoughts of the Maltese Falcon. And finally, the shot in which Caspere’s “chauffeur” drags his lifeless body from the car and across the dry earth was definitely a nod to Blood Simple. (If anyone is skeptical of the idea that Pizzolatto would toss in such references, I refer them to last season's clear call-out to the best line of Mickey Rourke's career, in Body Heat.)

Frank is a mobster trying to go legit, played by a comic actor who keeps trying to establish himself, without much success, as a serious actor.•I’m not yet sold on Vince Vaughn as Frank, but I’m not unsold either, which was probably a greater risk. We’ll see how his performance develops, but I’m at least intrigued by the (almost certainly deliberate) parallels: a mobster who keeps trying, without much success, to go legit, played by a comic actor who keeps trying, also without much success, to establish himself as a serious actor. This will be something to watch.

•What I am definitely unsold on is the idea that a self-identified police officer could brutalize a middle-class homeowner on his very own doorstep, without a disguise and in front of a witness, and not face serious repercussions. I don’t care how corrupt Vinci is. It was tough enough to swallow Ray’s masked beating of (and theft from) a newspaper journalist—which would, of course, be bigger news than anything else the poor guy was going to write. But I’m willing to suspend my disbelief for shots as good as Ray’s finger-to-the-mouth shushing (which you mentioned, Spencer), and the way the violence that ensued was conveyed by the merest fluttering of the bedroom blinds.

•Which is another way of saying that, like you, Sophie, I’m buying into the delightful ridiculousness of the show. I was one of those who went deep, deep, deep down the rabbit hole last season in the expectation that all the clever hints and repetitions would ultimately be revealed to be part of a vast and brilliant narrative contraption. Instead, the series concluded with (another) redneck psycho in the swamp. In part as a result of that disappointment, this season I feel liberated of the burden of expectations that what we’re watching might be Great Television. I’m content with it just being damn good TV.

•I’m also glad that I wasn’t the only one suppressing guffaws at Taylor Kitsch’s motorcycle cheek-flaps. I don’t think I’ve seen anyone look so silly since Roger Moore’s jowls were pinned to his ears by the G-force centrifuge in Moonraker.

•The final scene, with the principal characters finally united and eyeing each other like gunfighters in a Sergio Leone movie, was also a bit over the top, but in the most delicious way possible. I loved the camera spiraling away from them and up into the night sky. Finally, I don’t know whether you guys recognized it, but the gloomy, electric dirge that accompanied the credits was actually a cover of the Gatlin Brothers’ 1979 pop-country ditty “All the Gold in California.” Anyone in need of a bit of light, chuckling nostalgia after the grimness of the episode can find the original here. See you next week!

June 20, 2015

In Charleston, Forgiveness Meets Hatred

On Saturday, news broke that Dylann Roof, the 21-year-old charged with the murder of nine people in Charleston, South Carolina, had apparently published a lengthy manifesto on The Last Rhodesian, a website he registered in February, in which he described African Americans as genetically inferior to whites and defended legal segregation. The site, whose name refers to a former British colony governed by an apartheid regime, also contained images of Roof at plantations and in front of a Confederate museum in South Carolina—iconography of the state’s history of slavery. In the months before his attack, Roof reportedly spoke often of his hatred toward blacks and his desire to ignite a “race war” in the United States. The manifesto, a seething catalog of hatred encompassing Jews, blacks, and Hispanics, feels quite plausibly like the work of a killer who spared one person’s life reportedly so she could tell the world what he had done.

The manifesto showcases a character markedly different from those the world saw on Friday, when several relatives of the nine people slain inside Charleston’s historic Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church appeared in court and addressed Roof. The family members of the dead told Roof, a professed white supremacist, of their pain and anguish. But they also said they would forgive him.

“I will never be able to hold her again, but I forgive you,” a daughter of one victim said. “We have no room for hating, so we have to forgive,” said the sister of another. “I pray God on your soul.”

Given the heinous nature of the crime, the willingness of Charleston’s survivors to forgive was remarkable—and earned particular praise from President Obama. But the act of forgiving is more than just an expression of grace toward a wrongdoer. It’s also an effective tool in helping individuals and communities touched by tragedy accelerate the healing process.

The act of forgiving is more than just an expression of grace toward a wrongdoer.In March, the Atlantic’s Olga Khazan profiled Everett Worthington, a professor of psychology at Virginia Commonwealth University whose mother was brutally murdered in a 1995 burglary. As it happened, Worthington’s own research examined the effects of forgiveness. So in the days after his mother’s death, he decided to employ a five-step process he had previously devised:

First, you “recall” the incident, including all the hurt. “Empathize” with the person who wronged you. Then, you give them the “altruistic gift” of forgiveness, maybe by recalling how good it felt to be forgiven by someone you yourself have wronged. Next, “commit” yourself to forgive publicly by telling a friend or the person you’re forgiving. Finally, “hold” onto forgiveness. Even when feelings of anger surface, remind yourself that you’ve already forgiven.

Worthington found that his approach worked—and that other examples confirmed his intuition. Studies have shown that forgiveness aids mental and physical health, while the opposite reaction—holding a grudge and harboring resentment—has the opposite effect. This can also be applied to entire communities touched by mass tragedy. In 2006, 32-year-old Charles Roberts stormed into a one-room schoolhouse in an Amish community in Nickel Mines, Pennsylvania and shot ten girls, killing five before turning the gun on himself. Despite enormous shock and grief, several of the victims’ family members appeared at the killer's funeral just days later. When Roberts’ aggrieved mother then announced plans to leave the community, relatives of the dead persuaded her to stay. Seven years later, CBS News reported that the elder Roberts had become the primary caregiver for a girl her son had wounded in the attack.

“Is there anything in this life that we should not forgive?” said Roberts.

An individual or community’s gift of forgiveness, however, does not obviate a society’s demand for justice. In a 2014 case described by the Atlantic’s Andrew Cohen, a Colorado prosecutor seeking the death penalty for a prison inmate charged with murdering a corrections officer engaged in a contentious dispute with the victim’s parents, who opposed capital punishment. After months of back and forth, the prosecutor finally agreed to forgo the death penalty. The defendant, whose attorneys believed him to suffer from mental illness, ultimately pled guilty and is now serving a life sentence.

In the wake of the Charleston murder, South Carolina governor Nikki Haley said that the state would “absolutely want” the death penalty for Dylann Roof. Even Roof’s own uncle said he would support his nephew’s execution, telling reporters that he’d volunteer to “be the one to push the button.”

Several months—at the very least—will pass before a judge determines Roof’s fate. But the decision of the victims’ relatives to forgive may ease some measure of their pain.

Forgiveness After Mass Murder

On Friday, several relatives of the nine people slain inside a historic black church in Charleston, South Carolina appeared in court and addressed Dylann Roof, the 21-year-old charged with mass murder. The family members of the dead told Roof, a professed white supremacist, of their pain and anguish. But they also said they would forgive him.

“I will never be able to hold her again, but I forgive you,” a daughter of one victim said. “We have no room for hating, so we have to forgive,” said the sister of another. “I pray God on your soul.”

Forgiving Roof will not be easy. Entering the Emanuel AME church on Wednesday evening, the unemployed 21-year-old sat through an hourlong service before opening fire on fellow parishioners. Captured the next day, investigators soon found that the attack was clearly premeditated. Roof published a lengthy manifesto on The Last Rhodesian, a website he registered in February, in which he described African-Americans as genetically inferior to whites and defended legal segregation. The site, whose name refers to a former British colony governed by an apartheid regime, also contained images of Roof at plantations and in front of a Confederate museum in South Carolina—iconography of the state’s history of slavery. In the months before his attack, Roof frequently spoke of his hatred toward blacks and his desire to ignite a “race war” in the United States. After committing the mass murder last Wednesday, Roof told a survivor that he spared her life so she could tell the world what he had done.

Given the heinous nature of his crime, the willingness of Charleston’s survivors to forgive was remarkable—and earned particular praise from President Obama. But the act of forgiving is more than just an expression of grace toward a wrongdoer. It’s also an effective tool in helping individuals and communities touched by tragedy accelerate the healing process.

The act of forgiving is more than just an expression of grace toward a wrongdoer.In March, the Atlantic’s Olga Khazan profiled Everett Worthington, a professor of psychology at Virginia Commonwealth University whose mother was brutally murdered in a 1995 burglary. As it happened, Worthington’s own research examined the effects of forgiveness. So in the days after his mother’s death, he decided to employ a five-step process he had previously devised:

First, you “recall” the incident, including all the hurt. “Empathize” with the person who wronged you. Then, you give them the “altruistic gift” of forgiveness, maybe by recalling how good it felt to be forgiven by someone you yourself have wronged. Next, “commit” yourself to forgive publicly by telling a friend or the person you’re forgiving. Finally, “hold” onto forgiveness. Even when feelings of anger surface, remind yourself that you’ve already forgiven.

Worthington found that his approach worked—and that other examples confirmed his intuition. Studies have shown that forgiveness aids mental and physical health, while the opposite reaction—holding a grudge and harboring resentment—has the opposite effect. This can also be applied to entire communities touched by mass tragedy. In 2006, 32-year-old Charles Roberts stormed into a one-room schoolhouse in an Amish community in Nickel Mines, Pennsylvania and shot ten girls, killing five before turning the gun on himself. Despite enormous shock and grief, several of the victims’ family members appeared at the killer's funeral just days later. When Roberts’ aggrieved mother then announced plans to leave the community, relatives of the dead persuaded her to stay. Seven years later, CBS News reported that the elder Roberts had become the primary caregiver for a girl her son had wounded in the attack.

“Is there anything in this life that we should not forgive?” said Roberts.

The virtue of forgiveness, however, can encounter a legal system and population that seeks to maximize punishment. In a 2014 case described by the Atlantic’s Andrew Cohen, a Colorado prosecutor seeking the death penalty for a prison inmate charged with murdering a corrections officer engaged in a contentious dispute with the victim’s parents, who opposed capital punishment. After months of back and forth, the prosecutor finally agreed to forgo the death penalty. The defendant, whose attorneys believed him to suffer from mental illness, ultimately pled guilty and is now serving a life sentence.

In the wake of the Charleston murder, South Carolina governor Nikki Haley said that the state would “absolutely want” the death penalty for Dylann Roof. Her viewpoint is hardly unusual: Despite well-publicized execution-related mishaps, a Pew survey from last October found that 63 percent of Americans favor capital punishment. Even Roof’s own uncle said he would support his nephew’s execution, telling reporters that he’d volunteer to “be the one to push the button.”

Several months—at the very least—will pass before a judge determines Roof’s fate. But the decision of his victims’ relatives to forgive him indicates that the healing process, despite an enormity of pain, is well on its way.

Blink-182 and Game of Thrones: The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

The Internet Accused Alice Goffman of Faking Details in Her Study of a Black Neighborhood. I Went to Philadelphia to Check.

Jesse Singal | New York Magazine

“‘They’re funny to people,’ Goffman said of these videos. ‘They’re really funny, these cat videos. And my feeling was, these cats don’t have any choice in this, and why are they being pushed into the bathtub for sport for all of the humans to watch? ”

I Made a Linguistics Professor Listen to a Blink-182 Song and Analyze the Accent

Dan Nosowitz | Atlas Obscura

“Pop-punk vocals are on the forefront of shifting regional dialects and, especially, a major vocal change happening in California in the past few decades. The three-minute pop-punk song, one of the dumbest forms of music ever conceived (in a good way, I’d say), maybe isn’t so dumb, after all.”

Cersei’s Walk of Shame and Game of Thrones’ Evolution on Sexual Violence

Cersei’s Walk of Shame and Game of Thrones’ Evolution on Sexual ViolenceAmanda Marcotte | Slate

“More than any other in the show’s history, this season showed the writers' deep understanding of sexual violence: that it’s not about titillation or sexual gratification, but about dominance.”

This Is the Part Where I Defend Me and Earl and the Dying Girl

Dave Ehrlich | The Dissolve

“I first saw the movie at its storied premiere (every Sundance has that one screening that feels more like a happening), after which I called it ‘The Citizen Kane of teen cancer tearjerkers,’ a somewhat backhanded compliment that nevertheless was meant to convey a genuine admiration for what I’d just watched. A little more than a month after returning to sea level, I learned my dad had a Grade IV brain tumor.”

Film From the Ashes

John Lingan | The Verge

“Cultural artifacts, like natural ones, go extinct as a matter of course. The question is simply how to carry history into each new era. There will never be a final film format; the movies will keep getting upgraded and compressed into tinier units of digital memory. But as they do, the world’s slowly improving stock of nitrate film will beckon—romantic, profound, extraordinarily novel.”

Start-up Costs: Silicon Valley, Halt and Catch Fire, and How Microserfdom Ate the World

Alex Pappademas | Grantland

“Rather than an on-the-ground account of the first tech boom, then, Microserfs is an inadvertent time capsule of the moment just before the explosive growth of the consumer-facing Internet transformed society’s relationship to technology.”

LeBron’s Handling of Blatt Unbecoming

Marc Stein | ESPN

“James’ otherworldly performance in this series, on top of everything he’s done for Northeast Ohio just by returning to the area and revitalizing it beyond words, doesn't make any of this stuff palatable.”

Painting’s Point-Man

Peter Schjeldahl | The New Yorker

“Among other things, Oehlen offers an insight into why digital pictorial mediums can be exciting—and certainly are triumphant in global visual culture—but still fail to sustain intellectual interest or to nourish the soul. They are all in the head.”

The 40-Year Legacy of Jaws

If Jaws were released today, rather than 40 years ago, it’d be greeted as a mid-budget creature feature, a small-town drama centered around three relatable characters. There’s action, yes, and suspense, and some shocking gore. But it bears little resemblance to the blockbuster culture it’s credited for creating: Steven Spielberg’s film was given a near-unprecedented “wide” release, opening on 409 screens when it hit cinemas on June 20, 1975. Last weekend, Jurassic World debuted on 4,274. Jaws might be the primordial ooze from which Hollywood’s modern-day strategies emerged, but to look back on it now, it’s almost disarmingly quaint.

Related Story

Shark Week: Remembering Bruce, the Mechanical Shark in ‘Jaws’

Jaws’s strengths and weaknesses have been dissected at length in the years since its release. Only Spielberg’s third feature-length film at the time, the adaptation of Peter Benchley’s hit novel about a man-eating shark went almost three times over budget and featured a mechanical prop that looked the furthest thing from terrifying. To combat that, Spielberg mostly shot around it, building tension through underwater point-of-view footage and John Williams’ landmark, minimalist score. Rolled out nationwide with the kind of blitzkrieg advertising and promotional tie-ins that would later become Hollywood norms, Jaws is the prototype of the modern blockbuster, and was the highest-grossing film of all time until Star Wars came out two years later. If there’s anything you love or hate about the big-budget, studio action movie, it can probably be traced back to Jaws. And yet what makes the film work is not the history-making blueprint it set out, but instead all of the charming, unsung idiosyncrasies that make it a great film.

Spielberg’s first stroke of genius was in the casting—the director shied away from booking any A-list stars, knowing their screen presence might overpower the picture (Charlton Heston was among those interested in the script, but was turned down). Roy Scheider was probably the biggest name, coming off The French Connection, as Amity’s flustered police chief, Brody; Robert Shaw, as shark hunter Quint, was a well-regarded British character actor who usually played villains, and Richard Dreyfuss, as marine biologist Matt Hooper, was best known for his role in George Lucas’ American Graffiti.

Jaws is hardly a high-stakes, apocalyptic tale; the central conflict has a more intimate, claustrophobic feel. In the film, Amity’s shark attacks are claiming lives in the single digits, not the thousands, and they’re occurring on a single tourist-clogged beach, not the whole planet. The three men who take it upon themselves to destroying the beast are hardly the best at what they do—Quint is a washed-up fisherman, Brody a seaside cop who’s afraid of the water, and Hooper’s an agreeable nerd who’s just as excited to photograph the shark as he is to kill it. Spielberg spoke of wanting to make the film feel like it could happen to anyone, and that approach helped soften the blow of Jaws’s disappointing technical effects. The shark is a powerful beast, but once it emerges from the water, it almost looks as hapless as the people around it, flailing around on Quint’s boat in a failed effort to sink it.

When the protagonists manage to triumph over the monster, it’s a success that feels truly earned, rather than dictated by formula.Spielberg’s grounded, everyman approach to heroism was one he would repeat throughout his career. Jurassic Park doesn’t feature any superstars, nor does E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, because Spielberg wanted to replicate that same familiarity with his characters—audiences don’t look for an obvious savior, but rather identify with the real people swept up in an impossible situation. Like Jaws, those films also kept a foot in reality by keeping their environments small. Viewers can reckon with the crisis in Amity and the foolish decisions made by the people in charge (its mayor refuses to close the beaches despite the shark-attack risk), just as they can follow the specific beats of how things go wrong, one by one, at John Hammond’s unopened dinosaur park.

It’s an approach that many blockbusters have failed to heed, even if a successful tale can be told on a much grander scale—look at the wide-screen success of Mad Max: Fury Road this year, or the infinite parts of the Marvel cinematic universe. Even Spielberg himself would acknowledge that his biggest error in his Jurassic Park sequel, The Lost World, was bringing a T-Rex to wreak havoc in San Diego—the story got too big, and too messy. Meanwhile, Jaws’ heroes have a simple mission: Take down an oversized shark with a couple of guns and cans of pressurized air. When the protagonists manage to triumph over the monster, it’s a success that feels truly earned, rather than dictated by formula.

Jaws might be the prototypical blockbuster, but that was more a feat of studio genius and marketing than Spielberg’s filmmaking—in the 1970s, the only films that would be crammed into hundreds of theaters on their release day were B-movies and exploitation dramas, so as to avoid bad reviews. More reputable studio films would start slowly, screening in just a few theaters, before building up to a wider release across the country over many weeks. Jaws was not the first film to buck that strategy, but it was one of the first well-reviewed films to do it, coupled with an unprecedented advertising campaign. It was a strategy that studios would refine and repeat over the next 40 years.

In honor of its anniversary, Jaws will be back in select theaters on June 21, and even if for fans who’ve seen it enough times to be prepared for every jump and twist, it still has the ability to surprise. Jurassic World, the latest heir to Jaws’s box-office throne, will likely be playing on a screen nearby. Asked to top an already perfected formula, it bemoans its legacy, meta-textually winking at the impossible task given to sequels of beloved original works. Jaws, by contrast, is a film about three men in a boat looking for a shark, and it’s all the better for it.

What Happens If Greek Banks Can't Open?

The scariest quote for the world economy this week came from a member of the European Central Bank’s executive board. Asked by Eurogroup President Jeroen Dijsselbloem whether Greek banks would open Friday, his answer was stark:

"Tomorrow, yes. Monday, I don't know," replied Benoit Coeure.

So far, Coeure is right: Greek banks were open on Friday, though that wasn’t what people were worried about. The important issue is whether Greece can come to an agreement with its creditors to release bailout funding that will keep banks running. At the moment, Greece is due to owe creditors €1.6 billion at the end of June, money the government says it doesn’t have. If it can’t either repay or reach an extension deal, Greece might leave the eurozone—the doomsday scenario with the somewhat silly name “Grexit”—though default wouldn’t necessarily mean departure.

On Friday, the ECB apparently gave Greece a short-term cash infusion to last through the weekend, and the eurozone ministers will reconvene on Monday to try to hammer out a longer-term deal. If you feel like you’ve been hearing about this for years, you’re not entirely wrong—there have been dire warnings about Greece departing the eurozone since the spring of 2012. This time really does seem to be different. Greece’s left-wing government has refused to make as many concessions as its creditors want—which isn’t to say that Grexit is inevitable.

Related Story

How Greece Escaped a Major Crisis—for Now

”I don’t think we should be too dramatic,” said Simon Johnson, a professor at MIT and former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund. “The Europeans want to keep the Greeks in the eurozone and the Greeks want to stay in the eurozone. There’s still room for deals here, and all of these deals get done at the last minute.”

Johnson isn’t alone. Although the mood has darkened a bit over the last few days, there’s a widespread expectation among many analysts that an agreement will be reached. As some Greeks demonstrated outside of parliament in favor of remaining in the eurozone, others headed to banks to prepare in case that doesn’t happen. “A steady stream of people—though never enough to call a queue—were withdrawing money from the National Bank branch on Athens’s central Syntagma Square,” reported The Guardian’s Jon Henley. Greek depositors withdrew a billion euros on Thursday alone, and €3 billion since Monday.

That’s not quite a full run on the banks, but it’s a step toward it. The way to stop that is to close the banks, but doing so would likely also herald Grexit.

“The typical reason [a bank closure] would happen is that at the bank level or country level you have a lack of reserves, and so you just say, ‘We’re going to stop this earlier rather than wait for the inevitable to happen,’” Johnson said. “I don’t see that as part of a negotiating strategy—you only close them if you’ve been told the ECB system isn’t backing your banks.”

“There’s still room for deals here, and all of these deals get done at the last minute.”The result would be a series of intriguing but catastrophic complications. The economy wouldn’t stop, exactly, but finding ways to conduct everyday transactions would suddenly become all-consuming. For as long as banks stayed closed, Greeks would have to find ways to get by without using the financial system and accessing their own savings—using cash they had withdrawn before the closures or IOUs, for example. (This is the vicious cycle of a bank run—people are worried about closures, so they withdraw their funds; those withdrawals only make a closure even more likely.)

Meanwhile, the government would have to quickly switch course from frantically negotiating a way to remain in the eurozone to implementing a new currency—presumably a return to some variety of the drachma, used from 1832 to 2001. (CNBC recently guessed it would take around $430 million to mint new money; who knows where funding would come from.)

There’d be all sorts of complications to that. Johnson laid out the simplest: If I loan you €10 on Friday and Greece leaves the euro on Monday, what do I owe you on Tuesday? Is it €10? Or some equivalent in drachmas? If the latter, what is the exchange rate?

Now, imagine that on the level of an entire economy, with elaborate loans and contracts and business agreements laid out over time, and all denominated in euros.

“The bigger problem is disrupting credit; disrupting contracts, which are all in euros; having to renegotiate everything; and whatever that does to trade between Greece and the EU, including of course tourism,” Johnson said.

There aren’t a great number of real-world examples for how this might happen. One recent case is in Argentina, where the peso was pegged to the dollar from 1991 to 2002. Late in that period, it became clear that it wasn’t working—just as Greece, Spain, and other eurozone countries with struggling economies have found, the inability to control your own monetary policy makes it very hard to dig out of an economic hole. In anticipation of a currency devaluation, Argentines began withdrawing cash from banks in U.S. dollars. In response, the government instituted a “corralito,” or little corral, on the system: Residents were limited to small weekly cash withdrawals; those whose accounts were denominated in dollars could only withdraw money after converting to pesos; and business had to be conducted with plastic.

The move was politically disastrous; a series of short-term presidents came and went. Argentina was forced to devalue the peso and establish a floating exchange rate. But within a couple years, the Argentine economy was being hailed as a turnaround success. (More recently, it has hit some turbulence.) That’s perhaps a positive sign. “Would this be a negative hit to Greek GDP and real wages and so on? Absolutely,” Johnson said. “But it’s not the end of the world. Economies do recover from this.”

Economists have speculated that Greece might implement its own capital controls—for example, limiting withdrawals, capping the amount Greeks can send overseas, and preventing the cashing of checks. That would stop short of closing banks, and it could help stave off a Grexit in the event that Greece ran short on cash. It would slow down normal processes and allow more time to strike a deal with creditors, even though the immediate effects on the economy would be nasty.

“Would this be a negative hit to Greek GDP and real wages? Absolutely. But it’s not the end of the world. Economies do recover from this.”The hope in Brussels—and in Berlin and in Athens—is that no one will have to find out how a Greek exit would play out. Both sides have sounded pretty acid in the last few days: Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras has been courting Vladimir Putin (does he know what the Russian economy looks like right now?); EU President Jean-Claude Juncker blasted Tsipras in an interview with Der Spiegel and effectively accused him of being a phony socialist who wouldn’t raise taxes on his country’s wealthy. But both sides seem to be fairly close together and have strong incentives to get to yes. For the Greeks, that’s avoiding a massive economic upheaval. For Europe, that’s the preservation of the euro as a permanent currency union. Even if an Españexit or Portuguexit (look, I’m doing my best here) isn’t imminent, creating a precedent where a country can leave would open the possibility to other departures in the future.

And there are spillover effects outside of the currency. While the United Kingdom doesn’t use the euro, it is slated to hold a referendum on EU membership, amid growing euroskepticism. France’s Le Monde used the anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo to publish an English-language editorial pleading with Britain to avoid “Brexit.”

Of course, these have been the stakes all along, and yet European leaders continue to feud as the deadline approaches. Mondays are never fun, but this coming Monday could be a particularly manic one.

June 19, 2015

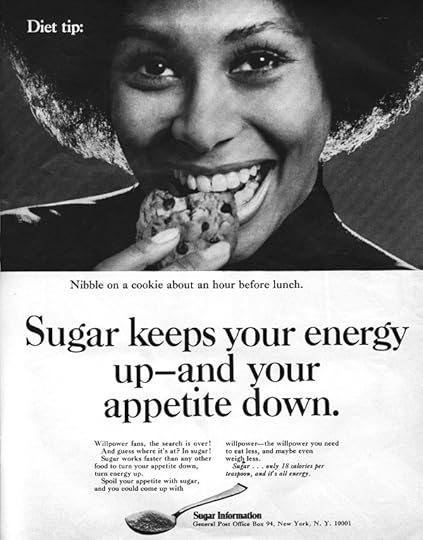

‘If Sugar Is Fattening, How Come So Many Kids Are Thin?’

Sugar, these days, has a bad reputation. The crucial ingredient in the foods that many Americans count among their favorites (hey, Ben! what is up, Jerry?) has become, in the public mind, not just a source of sweetness on the palate, but also a “poison.” A “toxin.” Something that, some argue, should be regulated the same way alcohol is. The consumption of refined sugar, as we commonly understand it today, is a direct cause not just of obesity and fatigue, but also of diabetes and depression—not to mention many more maladies that are the current subjects of research. Refined sugar, the current thinking goes, won’t just make you gain weight; it will also leech away your health, pretty much, one red velvet cupcake at a time.

How marketing defined and influenced an era

How marketing defined and influenced an eraRead More

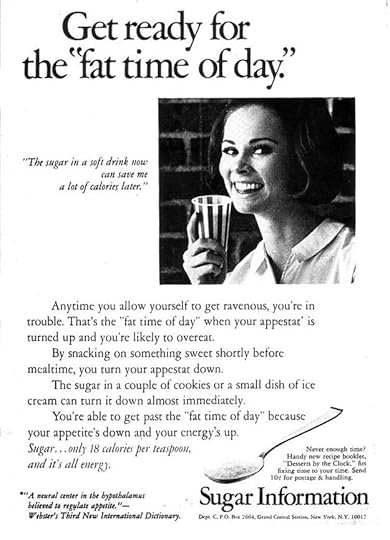

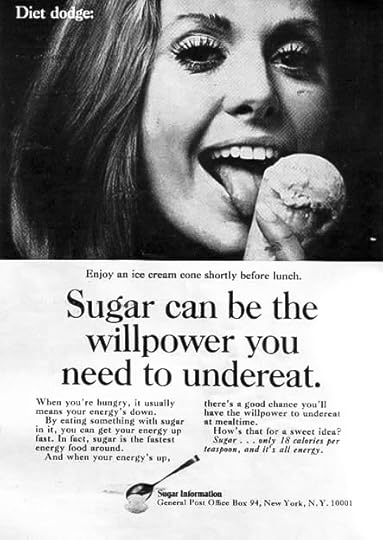

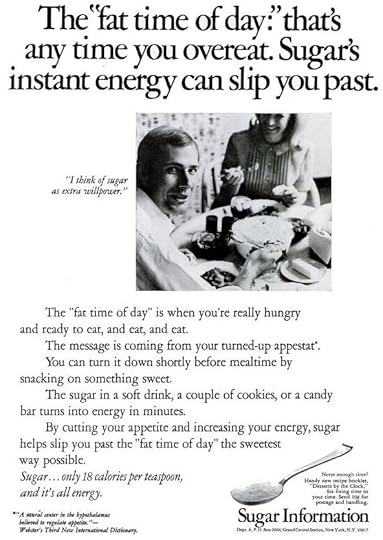

All that thinking, though, has come about relatively recently. Just a few decades ago, in the early 1970s, the PR arm of the Sugar Association, the leading trade group representing both sugar growers and sugar refiners, launched a campaign premised on the idea that sugar was ... a useful diet aid. The campaign came during a time when the Sugar Association itself was discovering links between the consumption of sugar and conditions like diabetes and obesity. It sidestepped concerns about sugar’s effect on one’s health, however, by focusing on sugar’s effect on something else: one’s appearance.

One of the ads in question summoned neuroscience, invoking the appestat—“the region of the hypothalamus of the brain that is believed to control a person's appetite for food”—and suggesting that sugar consumption was a way to trick the appestat into a sense of satiety.

Another took a more emotional approach to the idea that sugar could suppress the appetite, focusing on the willpower required to, as this ad unironically puts it, “undereat.”

Another, from a 1970 issue of Life magazine, told the same basic story—a cyclical hunger-monster that must be fooled into submission in order for weight loss to be achieved—from the male point of view:

Another, from Life’s November 1970 issue, was even more brazen, cheekily claiming that sugar can “spoil your appetite.” (And recommending that a dieter “nibble on a cookie about an hour before lunch.”)

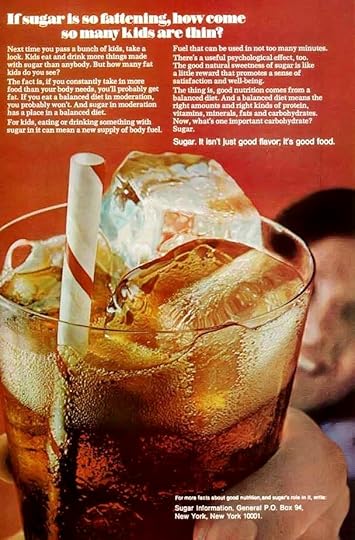

Yet another, from 1977, took a more orthogonal approach to the sugar-as-diet-aid idea, focusing on the health benefits of sugar in kids’ diets, in particular. Sugar’s “good natural sweetness,” the ad argued, its spunky glass of cola thrust forward by a blurry child, can be an important part of any “balanced diet.”

Credit

Credit The rhetoric here—“good natural sweetness”—was in part a response to the rise of artificial sweetener, particularly as ingredients in sodas and other beverages.

Saccharine, discovered in the late 1870s, had been available in commercial foods for most of the early 20th century. (So had controversies about the dangers the sweetener posed to public health: In 1908, after a government chemist proposed a ban of the substance, Theodore Roosevelt declared, in his Bull Moosian way: “Anyone who says saccharine is injurious to health is an idiot.”) It wasn’t until mid-century, though, that artificially sweetened sodas entered en masse, and with an emphasis on their abilities as diet aids. In the early 1950s, New York's Jewish Sanitarium for Chronic Disease—known today as the Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center—produced a soda for its diabetic patients. The drink was called No-Cal, and it sold surprisingly well, much better than you’d expect for such an ostensibly niche product. It turned out that more than half the consumers buying the drink were doing so not because of diabetes, but because of diets. A new kind of soda was born—with No-Cal quickly followed by Coca-Cola’s diet soda, Tab, and Patio Cola, rebranded in 1964 as Diet Pepsi.

It was natural, given all that, that the interest group known today as “Big Sugar” would try to corner its own segment of the diet market. It was natural that it would try to emphasize the naturalness of sugar when compared to the synthetic sweeteners. The sugar advertising that took place in the 1970s may have been laughably inaccurate. It is also, however, a reminder of how dynamic our assumptions about health and wellness can be, and of how deeply informed those assumptions can be by people who are experts in marketing rather than medicine. In 1976, for its pro-sugar campaign, the Sugar Association won the Public Relations Society of America’s prestigious Silver Anvil award. In its citation, the PRSA praised the campaign’s ability to “reach target audiences with the scientific facts concerning sugar,” and to “establish with the broadest possible audience the safety of sugar as a food.”

Colin Farrell’s Evolution: From Movie Star to Actor

In True Detective’s second season, Colin Farrell is playing exactly to type. As the washed-up, corrupt Detective Ray Velcoro, his skin looks leathery, his temples are gray, and he pours endless glasses of whiskey under his push-broom mustache. If brooding were an Olympic sport, Farrell would be a repeat medalist, and so it seems hardly notable that he’s endured in an industry that loves haunted male protagonists. But Farrell’s career in many ways has subverted the typical Hollywood model. After becoming a pin-up early in his career, and taking on high-profile roles in huge studio movies, he flamed out, personally and professionally. But failure, rather than ending his career, allowed him to tackle more daring and versatile roles, and find subsequent credibility as an actor.

Related Story

A Very Forgettable ‘Total Recall’

Farrell entered show business as a ready-made star, thrust at audiences in the kind of pandering Hollywood way that almost guarantees backlash. He had the charisma to sell subpar work, but whenever he was given the chance to cut loose, it was in trashy genre exercises like Phone Booth or Daredevil that critics largely ignored. Following the initial boom and bust of his early years in Hollywood, though, Farrell has carved out a more serious reputation by working with legendary directors, taking on offbeat projects, or both. It’s the opposite of the typical A-list trajectory: Actors like Jennifer Lawrence or Leonardo DiCaprio started small and built up credibility in independent movies before transitioning to blockbusters. Farrell, by contrast, was thrust into that territory instantly, and it almost proved his undoing.

It’s easy to forget that he was once Hollywood’s newest golden boy. A young Irish actor who had a handful of TV roles in the ‘90s, he got his big break as the darkly charming lead of Joel Schumacher’s Tigerland (2000), a low-budget Vietnam drama that made no money but received acclaim and a handful of critics’ awards. After that, he appeared in a glut of studio films, from the forgotten American Outlaws and Hart’s War to a memorable supporting turn in Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report. His one true box-office hit was the 2003 action drama S.W.A.T., which took $116 million at the domestic box office. But the rest of his career is a collection of middling hits and outright flops: Only four years from after his Hollywood debut, Farrell headlined a one-two punch of big-budget bombs that seemed to confirm his overrated status.

The first was Oliver Stone’s 2004 biopic Alexander, a misguided three-hour rumination on the life of the legendary warrior, told largely through flashbacks, with Farrell playing the Macedonian with an Irish accent alongside Angelina Jolie as his mother (despite her being only a year older than him). Stone has repeatedly recut the film for multiple DVD releases, but at best it remains an ambitious failure, and Farrell looks lost amid its epic trappings. His next blockbuster was 2006’s Miami Vice, a retelling of the ‘80s cop drama from Michael Mann. Billed as an action thriller, it plays as a big-budget, avant-garde mood piece with occasional surges of gun violence. Audiences were baffled, and the production was reportedly torturous—Farrell checked into rehab soon after it wrapped.

After these failures, the actor turned to artier projects, but he was already well on that road even if no one saw it. His work in True Detective echoes his Sonny Crockett turn in Miami Vice; Farrell suggests the weight of the world through just a mournful gaze, furrowed brow, and half-mumbled dialogue. His role as the explorer John Smith in Terrence Malick’s Pocahontas drama The New World (2005) worked along the same lines, suggesting rage and sadness with every glance. Farrell’s early film work saw him playing roguish charmers jittering with energy; it was only as his career began to spiral, and he began to work with demanding auteurs like Malick and Mann, that he tapped into a darker well.

In Farrell’s hands, Ray Velcoro is a person first, an archetype second.In a 2010 interview with the Daily Telegraph, Farrell acknowledged that getting so famous so fast thrust him into the L.A. party circuit, which stunted his development. “There was an energy that was created,” he said, “a character that was created, that no doubt benefited me. And then there was a stage where it all began to crumble around me.” The breakdown began with the punishing filming on Alexander and crested during the making of Miami Vice, he said, where he finally had to confront how unprofessional his behavior had made him.

His rebound began with the violent, raucous 2008 comedy In Bruges, written and directed by the playwright Martin McDonagh. As Ray, a hitman ordered to lay low after accidentally shooting a young boy during a botched job, Farrell is maniacally funny, but only in an effort to distract himself from the terrible weight of his actions. He won a Golden Globe and rebounded into consistent, but less high-profile Hollywood work, giving memorable supporting performances in hits like Horrible Bosses and Crazy Heart while also pursuing auteur-driven indie projects like Liv Ullmann’s adaptation of Miss Julie, or the recent Cannes hit The Lobster, from the Greek filmmaker Yorgos Lanthimos.

The clearest analogue to Farrell’s decline and rebound is Marvel’s franchise star, Robert Downey Jr., who is currently the highest-paid actor on the planet. After a similar wunderkind start, Downey Jr. struggled with substance abuse and could no longer book big-studio pictures. He regained his credibility with little-seen but highly-praised work in indies like Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, but used that to catapult himself back to the top of the Hollywood heap. Now he’s the centerpiece of two franchises (the Marvel Universe and Sherlock Holmes) and has publicly vowed never to make another indie film. He’s lost none of his on-screen magnetism, but may never take a creative risk again.

In True Detective, Farrell is walking the line between indie hits and high-profile projects. The role is an opportunity to cement his rehabilitation from junky B-list star to respected performer, as it was for Matthew McConaughey in the anthology series’ first season. Nic Pizzolatto, the show’s writer, has handed Farrell plenty of ponderous, weighty dialogue to deliver in a half-audible growl, and while he rises to the challenge, the show always seems to be operating at the very edge of self-parody. But whether or not True Detective sustains the atomic critical buzz and viewership it attracted last year, Farrell’s participation, at the very least, suggests that something special could happen.

‘Hate Crime’: A Mass Killing at a Historic Church

Updated on 6/19

On Friday, as he was set to be charged with nine counts of murder, Dylann Roof admitted his role in Wednesday’s shooting at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

“In addition to the nine murder counts, Roof is charged with possessing a weapon during the commission of a violent crime,” the AP reported. South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley added that the state will “absolutely” seek the death penalty against Roof.

Updated at 2:50 p.m. EST.

Dylann Roof, the 21-year-old who is suspected of a mass killing at a historic black church in Charleston, South Carolina, has been taken into law enforcement custody. Nine people were killed and at least one other was wounded in the shooting, which occurred at a Wednesday night prayer meeting at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, one of the oldest black churches in the South.

The Shootings and the Aftermath

Roof sat for about an hour with congregants in a weekly prayer meeting, Charleston Police Chief Greg Mullen said in a press conference. Then, shortly after 9 p.m., he allegedly opened fire.

A cousin of one of the victims, Sylvia Johnson, relayed a survivor’s account to NBC News claiming that the shooter reloaded his weapon five times. According to Johnson, the gunman told the survivor, “I have to do it. … You rape our women and you're taking over our country. And you have to go.”

“I will say that this is an unspeakable and heartbreaking tragedy in this most historic church, an evil and hateful person took the lives of citizens who had come to worship and pray together,” Charleston Mayor Joe Riley told reporters, according to the Post and Courier. Mullen went further in his remarks, saying,“I do believe this was a hate crime.”

As news of the shooting spread, locals gathered in the streets surrounding the church in an impromptu prayer session for the victims. By noon on Thursday, hundreds had gathered in local churches and on nearby streets to commemorate the dead, the Post and Courier said.

South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley issued her condolences after news of the shooting broke. “While we do not yet know all of the details, we do know that we’ll never understand what motivates anyone to enter one of our places of worship and take the life of another,” she said in a statement.

“Michelle [Obama] and I know several members of Emanuel A.M.E. Church,” President Barack Obama said at a White House press conference. “To say our thoughts and prayers are with them and their families and their community doesn’t say enough to convey the heartache and the sadness and the anger that we feel. Any death of this sort is a tragedy. Any shooting involving multiple victims is a tragedy. There is something particularly heartbreaking about that happening in a place in which we seek solace and we seek peace, in a place of worship.”

In his remarks, Obama linked the killings to a pattern of gun violence in the U.S.:

I’ve had to make statements like this too many times. Communities like this have had to endure tragedies like this too many times. We don’t have all the facts, but we do know that once again innocent people were killed because someone who wanted to inflict harm had no trouble getting their hands on a gun. Now’s the time for mourning and for healing, but let’s be clear: At some point, we as a country will have to reckon with the fact that this type of mass violence doesn’t happen in other advanced countries. It doesn’t happen in other places with this kind of frequency. And it is in our power to do something about it. I say that recognizing that the politics in this town foreclose a lot of those avenues right now. But it’d be wrong for me not to acknowledge it. And at some point, it’s going to be important for the American people to come to grips with it, and for us to be able to shift how we think about the issue of gun violence collectively.

The Iconic History of the Church

The targeting of Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal is particularly significant given its history and symbolism. One of the people killed was Clementa Pinckney, a South Carolina state senator and Methodist pastor at the church, and the youngest African African ever elected to South Carolina’s legislature. In a 2013 lecture posted on YouTube, Pinckney spoke about Emanuel A.M.E.’s significance to Charleston and the nation.

“Where you are is a very special place in Charleston,” Pinckney said in the lecture, addressing an audience of visitors to the church.

Pinckney continued:

In a nutshell, you can say that the African American church—and in particular, in South Carolina—really has seen it as its responsibility and its ministry and its calling to be fully integrated and caring about the lives of its constituents and the general community. ... Many of us don't see ourselves as just a place where we come and worship, but as a beacon, and as a bearer of the culture, and a bearer of what makes us a people. But I like to say that this is not necessarily unique to us; it's really what America is all about.