Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 405

June 25, 2015

Scalegalese: The Distinct Vocabulary of Antonin Scalia

“Words have meaning,” Antonin Scalia insisted in 2013. “And their meaning doesn’t change.”

That notion is something most linguists and lexicographers will, at minimum, quibble with. It is also, however, a foundation of Scalia’s originalist approach to Constitutional interpretation. “I mean, the notion that the Constitution should simply, by decree of the Court, mean something that it didn’t mean when the people voted for it,” the associate Supreme Court justice explained to New York magazine’s Jennifer Senior—“frankly, you should ask the other side of the question! How did they ever get there?”

How indeed. Scalia is someone who loves words—not just as sources of literary performance (alliteration! puns! Kulturkampf! argle-bargle!), but also as sources of semantic stability. Words, Scalia believes, root us, collectively and epistemologically. So his famously saucy approach to language isn’t just about bringing literature to legalese, or about the schadenfreudic delights of sending reporters scrambling to dictionaries and thesauri when he issues a scathing dissent. It’s also a philosophical declaration about the unchanging nature of old truths, whatever document may enshrine them. As the speechwriter Jeff Shesol wrote in the New Yorker last year, “His approach has always been to reach for a dictionary; find, in one edition or other, a definition that drives toward his predetermined decision; and express, eyes wide with disbelief, utter amazement that anyone could even think of seeing it any other way.”

Related Story

The Twilight of Antonin Scalia

As a result, Scalia has cited, in his opinions, not just the Random House College Dictionary, but also Noah Webster’s American Dictionary of the English Language (publication date: 1828), Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1773), and Timothy Cunningham’s A New and Complete Law Dictionary (1771). Because words have meaning. And their meaning doesn’t change.

It was itself meaningful, then, that in his dissent on Thursday in King v. Burwell, arguing against the Court’s latest upholding of Obamacare, Scalia concluded: “Words no longer have meaning if an Exchange that is not established by a State is ‘established by the State.’”

It was also meaningful that he added, of the majority decision:

“The Court’s next bit of interpretive jiggery-pokery involves other parts of the Act that purportedly presuppose the availability of tax credits on both federal and state Exchanges.”

And also that he called the Court’s upholding of Obamacare the result of “somersaults of statutory interpretation.”

And also that he concluded: “We should start calling this law SCOTUScare.”

On the one hand, of course, this is just Scalia being Scalia (and the rest of us being Scalia’ed). Jiggery-pokery! In one of his earliest dissents, in 1987’s Johnson v. Transportation Agency, Scalia quoted that linguistic ur-innovator: Shakespeare. Citing an exchange from Henry IV, the new associate justice invoked “spirits from the vasty deep.”

In Romer v. Evans, a 1996 case on LGBT discrimination, he declared that “the Court has mistaken a Kulturkampf for a fit of spite,” referring to “the German policies designed to reduce the role and power of the Roman Catholic Church in Prussia, enacted from 1871 to 1878 by the Prime Minister of Prussia, Otto von Bismarck.”

In PGA Tour v. Casey Martin, a 2001 case addressing the Americans with Disabilities Act’s place in professional sports, he referred to the notion of “Platonic golf.”

In 2009, he debated a presenting lawyer about the ontology of the word “choate.” (“There is no such adjective,” Scalia insisted. “I know we have used it, but there is no such adjective as ‘choate.’ There is ‘inchoate,’ but the opposite of ‘inchoate’ is not ‘choate.’”)

In his dissent in 2013’s Maryland v. King, a case that revolved around the constitutionality of taking DNA samples from arrest suspects, Scalia warned of the dangers of creating a “genetic panopticon.”

Words, in the Court, are proxies for Constitutional interpretation: either living, breathing, contextual things, or inscribed to their original coinage.In his dissent against the striking down of the Defense of Marriage Act, Scalia famously categorized the majority opinion in the case as “legalistic argle-bargle.” (The term itself, its argliness and bargliness to the contrary, is not argle-bargle: It means, the lexicographer Ben Zimmer pointed out, “a description of ‘a verbal dispute’ or ‘a wrangling argument.’”)

And in that 2013 interview with New York magazine, Scalia used the word “ukase”—as in, the decision to strike down DOMA was “not at the ukase of a Supreme Court.”

His interviewer, Jennifer Senior—summoning the reaction most Americans would have to this creative diction—replied, simply: “What?”

“U-K-A-S-E,” Scalia answered, spelling it out. “Yeah. I think that’s how you say it. It’s a mandate. A decree.”

The Justice, the National Constitution Center notes, was correct. Merriam-Webster defines “ukase” as “a proclamation by a Russian emperor or government having the force of law.”

All of which—words have meaning. And their meaning doesn’t change—is classic Scalia. It’s words interpreted not just as conduits of meaning, but as solidifiers of it.

In The Second Amendment: A Biography, Michael Waldman notes that Scalia “has the feel of an ambitious Scrabble player trying too hard to prove that a triple word score really does exist.” But the stakes in his game, argle-bargle and jiggery-pokery notwithstanding, are high. Words, in the Court, are—or, at least, they can be—proxies for Constitutional interpretation. Justices can see them either as living, breathing, contextual things, or as things that are inscribed to their original coinage. There cannot, Scalia insists, be two sides to this argument. Elena Kagan, in a back-and-forth opinion-battle with Scalia last year, declared that “we must (as usual) interpret the relevant words not in a vacuum,” but instead with regard to their “structure, history, and purpose.” A notion to which, in a flourish fitting of his great philosophical frustration, Scalia has now replied: “Pure applesauce.”

A Summer of Fatal Weather: Pakistan's Heat Wave

As of Thursday, more than 1,000 people have died because of a deadly heat wave in Pakistan, a catastrophe made worse by its coincidence with Ramadan, during which many Muslims refrain from eating or drinking water during daylight hours. The heat wave is the latest of several episodes of fatally severe weather across the world this summer, including droughts, storms and floods in the United States and Mexico.

As NPR’s Christopher Joyce has explained, it can be difficult to trace whether any single bout of extreme weather is attributable to climate change—witness the debate among scientists in Pakistan on whether the country’s heat wave is linked to a changing climate. But there is widespread scientific consensus that climate change generally makes extreme weather events such as flooding, droughts and heat waves much more frequent and more intense.

A major report this week from The Lancet finds that climate change significantly increases the fatal risks of these types of events. The report, which was backed by the World Health Organization, diagnosed climate change as “a medical emergency” with the power to undo 50 years of progress in global health. In a landmark document released last week, Pope Francis aimed to focus the world’s attention on the matter of how climate change impacts the poor. “Climate change is a global problem with grave implications: environmental, social, economic, political and for the distribution of goods,” he wrote. According to NOAA and NASA, this year is on track to supplant last year as the warmest year on record.

Here are some of the deadliest weather catastrophes that have drawn headlines this year. As the summer progresses, we’ll continue to update this report with any new developments.

Heat Wave in PakistanCircumstances: The travails of the ongoing heat wave in Pakistan are being exacerbated by the Ramadan fast. On Wednesday, June 24, a religious cleric issued a rare fatwa permitting Muslims to eat during the day because of the heat and government officials in the Sindh district declared an administrative holiday in the hopes that it would keep residents from going outside.

Effects: At least 1,000 people have died, a number that continues to rise. According to reports, the morgues in Karachi have run out of space.

Tornados and Floods on the Great PlainsCircumstances: In late May, Texas was in the midst of a severe drought when heavy rains flooded the state so thoroughly, it managed to reverse the drought. In Oklahoma, in addition to two feet of rain in May, tornado warnings forced Governor Mary Fallin to declare a state of emergency in all 77 counties on May 26. As the National Weather Service noted, “122 tornado warnings were also issued in the state from May 1 to May 25, more warnings than that time period from 2011 to 2014 combined.”

People affected: More than 30 people died in Texas, Oklahoma and Mexico. Thousands either lost their homes or suffered severe property damage.

Heat Wave in IndiaCircumstances: A long-lasting heat wave in late May struck India with temperatures in some regions rising to the 120-degree range. The early end of pre-monsoon showers brought with it sustained and unseasonable heat. As two-thirds of the citizens battled the heat with no electricity, temperatures in the capital city of New Delhi surged to 113 degrees, causing the roads to melt.

Effects: More than 2,500 people died and hospitals were overrun with people who fell ill from the heat.

Welcome to Smarter Basketball

On Thursday, 60 of basketball’s most talented prospects will realize a lifelong dream when the NBA conducts its annual draft. Karl-Anthony Towns, the Kentucky University center, has been heavily rumored to be the number one pick, but after that, it’s a bit up in the air. Among the potential picks: Jahlil Okafor, D’Angelo Russell, Emmanuel Mudiay, and Kristaps Porzingis, a versatile 7 foot 1, 19-year-old Latvian who’s as lean as he is skilled. Regardless of who ends up where, this high-potential group will be entering a league that’s undergone a major transformation in the past few years. And it’s a revolution that’s indisputably linked to the NBA’s growing, but controversial, reliance on data to measure a team’s likelihood of winning—a phenomenon vaguely defined as “analytics.”

Once, the dominant way of judging how well a player or team would perform was the “eye-test”—the organic, gut-instinct impression that came simply from watching a game unfold. But that time has been replaced by an era in which coaches and their backroom staff pore over formulas and figures—how many mid-range jump shots a team uses versus attempts near the hoop, or how many three-point shots versus two-pointers—to predict the most effective methods for winning. While some doubt the importance of the shift, there are still coaches and legends of the sport who reject the practice of analytics and are leery of how number-crunching will fundamentally change the sport.

“People say that analytics are taking the fun out of it, I think the NBA is in a better position now than it’s ever been.”Last week’s NBA Finals may have offered the naysayers the strongest evidence yet that analytics does, in fact work, that it’s become an entrenched part of basketball today, and that it will remain so for some time. The most-watched Finals since the age of Michael Jordan ended with victory for the Golden State Warriors over the Cleveland Cavaliers—both of which are teams that have heavily incorporated data analysis into how they play the game. The playoffs were yet another clear indicator that if teams want to win, they’d do best to ignore the likes of detractors such as Charles Barkley, who infamously went on a rant against the approach in January on Inside The NBA. (“Smart guys wanted to fit in so they made up a term called ‘analytics.’”)

There’s proof of the benefits of more advanced analysis beyond the success of the Warriors and Cavaliers. The Houston Rockets—led by general manager and analytics buff Daryl Morey—are renowned for their use of data. The team rarely shoots long-range two-point jumpshots, as they believe it to be one of the worst strategies in basketball. And their reasoning makes sense: The shots are too far away from the rim to be rendered a high-probability scoring opportunity, yet not far enough—as in behind the three-point line—for the risk to be rewarded with an extra point. This ideology, backed up by mountains of data, is a prime example of analytics at work. The Rockets were successful despite an injury-plagued season losing in the Western Conference finals to the Warriors. They also set the all-time record for made three-pointers in a season, with 894 this year.

While the movement to employ more sophisticated metrics has been in motion for some time, the turning point could perhaps be pegged as 2013—the year the NBA installed player-tracking systems in all 29 of its arenas. This was a watershed moment for the league: Every micro-movement on the court could now be tracked, quantified, and eventually archived. No longer could a player “hide” his deficiencies on the court. Coaches, their assistants, and the data-crunching backroom staff now had far more knowledge about players’ tendencies, and how certain groups of players work together than ever before. This has lead to a re-imagining of what matters in basketball and thus, a shift in the paradigm of player evaluation.

Take for instance “volume scorers,” or players who traditionally take a lot of shots and score a lot of points, but don’t add much value in terms of defense, rebounding, or assists, among other things. In the past, such single-minded players escaped media scrutiny by putting up impressive raw-scoring numbers, even though they were sub-par in other facets of the game. Today, those types of players are maligned for their lack of overall impact. Even stars like Kobe Bryant and Carmelo Anthony have been criticized for their excessive shooting. This current shift isn’t simply due to some yearning for more team-oriented, inclusive strategies. Instead, the nouveau-NBA has moved toward “efficiency” being the dominant theme. No longer is it about raw totals as much as it’s about weighing the impact of each action. This has in turn affected how teams score.

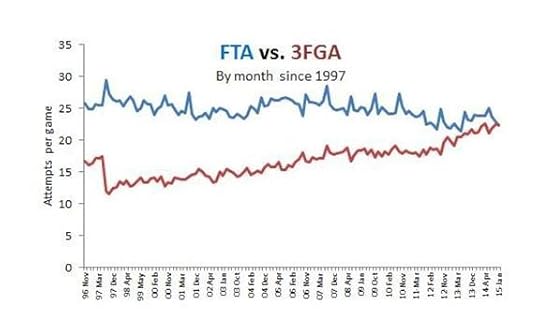

This January, for the first time ever the NBA saw more three-point shot attempts than free throws in a single month.

Free Throws Versus Three-Point shots, by Month Since 1997

Reddit

Reddit Harkening back to the Houston Rockets’s ethos, there’s been a league-wide shift from the two-point to the three-point shot over the years. And it’s a change that’s had tangible consequences for those who deny its reality. At the beginning of this recently completed season, the Los Angeles Lakers head coach Byron Scott, said that he would be eliminating a reliance on three pointers from the Lakers’ strategy. It was a move rightly condemned at the time as archaic—perhaps proven by the fact that the Lakers went on to finish this campaign with the worst record in franchise history. Of course, season-ending injuries to Kobe Bryant and rookie Julius Randle played a role in their dismal season, but completely divorcing their performance from that anti-three ideology would be granting Scott far too much of a pass. On the flip side, the 2015 Championship-winning Warriors were the league’s best three-point shooting team during the regular season. It’s almost impossible to disregard the success and importance of the three-point shot today: The last five teams remaining in the recently completed Playoffs were the five best three-point shooting teams during the regular season.

#goink RT @JoelCSchroeder: @tomhaberstroh 1. Rockets 2. Warriors 3. Clippers 4. Cavs 5. Hawks Top five teams in 3 pointers made.

— Tom Haberstroh (@tomhaberstroh) May 16, 2015

Casual fans who got wrapped up in the Finals would have noticed the long-range shooting prowess of Stephen Curry, who in his short six-year-career has become arguably the greatest shooter in NBA history. Curry’s father, Dell Curry, an NBA veteran of 16 years, was a three-point expert himself. But Curry’s skills are less the product of fatherly advice or genetics, and more the outcome of a cultural shift. Curry, now 27, grew up in an era where the shot became regarded as a more-integral facet of a player’s repertoire—not a just an unnecessary luxury, but a prized skill.

The three-point shot, which more than anything else defines the shift to analytics in the NBA, has come a long way from its rocky origins. Initially introduced in the now-defunct competitor to the NBA, the ABA, in 1967, the three-pointer was finally adopted after the two leagues merged 12 years later, to the chagrin of many basketball purists who deemed it gimmicky. Since they were never trained to make the longer-distance, higher-reward shot, most players ignored the three-point line and continued to play the game the old way, clogging the paint in an attempt to get to the basket.

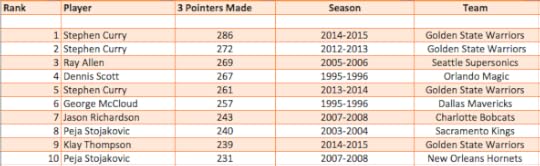

But, with time, the shot caught on. Eventually, three-point specialists abounded, and the game began to change. In 1982, Larry Bird led the league in three-point shooting with 90 shots made over the course of the 82-game season. This year, Curry beat his own record, racking up 286 three-point shots over the season and more than tripling Bird’s exploits. In fact, Curry actually dominates this list, a feat achieved all in the last few years.

Most Three-Point Shots Made in a Single Season

A graphic posted during ABC’s broadcast of the finals showed how far ahead of his peers Curry is. Curry has already made more three pointers during these Playoffs than the entire NBA did in 1980.

Curry would finish the Playoffs with 98 made 3-pointers, the most ever in a single Playoff season and 30 ahead of second place Reggie Miller. (ABC)

Curry would finish the Playoffs with 98 made 3-pointers, the most ever in a single Playoff season and 30 ahead of second place Reggie Miller. (ABC) Beyond giving rise to the three-pointer, analytics has also caused the casual fan to rethink and give long-overdue attention to the defensive side of the sport. Though people have always understood defense as important, it’s typically existed in the shadows of offense, which is easier to market and more exciting for the average viewer. This change to a heavier emphasis on defense has been relatively recent, but as Grantland’s Kirk Goldsberry told me, “Basketball is looking for the next challenge, and it’s obviously defense. Thanks to emerging data we can be smarter in terms of how we characterize overall basketball.”

A recent piece by Goldsberry offered groundbreaking evidence, based on a study he completed along with two Harvard Ph.D. students Andrew Miller and Alexander Franks, showing that for decades, defensive analysis has been largely anecdotal at best. While the statistical revolution on the offensive side has been a natural progression, on the oft-ignored defensive side of the ball it’s been an afterthought, until now. “Defense is literally half the game,” said Goldsberry, who added that players should be paid based on their ability to do both. “Unfortunately for the past dozens of years we’ve seen a huge imbalance in basketball towards the offensive end and part of it is because it’s hard to track defense.”

Now that we can quantify what had previously been intangible, players like Channing Frye and the recently retired Shane Battier are receiving praise for their versatility—something that wouldn’t have happened before analytics. It’s also why guys like the Warriors’ Draymond Green, who are adaptable and effective, are now so highly sought after throughout the league.

So after considering all this, why are so many—mostly older—NBA figures like Barkley still so opposed to the arrival of the data-driven NBA? For one, many played, and succeeded, at a time when analytics was in its infancy and most critical thinking around a player's impact on the court revolved around simpler, more straightforward metrics. As Stephen Shea, a professor who teaches analytics at Saint Anselm College in New Hampshire, told me, “It’s not shocking at all to see individuals who are highly successful in the NBA want to hold onto their way of doing things.” Indeed, Barkley’s era with—replete with its slower pace and emphasis on the individual over the team—has come and gone. Today’s NBA has evolved, partly due to rule changes that facilitate scoring, as well as a more organic maturing of strategy.

That said, whatever danger analytics might pose exists on a sliding scale. The worry is two-fold: that proponents of analytics often appear blindly devoted to proving their data’s legitimacy, and that a league-wide dependence on analytics could render the sport somewhat robotic.

Does it take all the unpredictability—the magic—out of the sport?For example, Sam Hinkie, the general manager of the Philadelphia 76ers, has been heavily criticized for taking a cynical approach to the sport. Hinkie’s main goal is to avoid “NBA purgatory” (essentially that middle ground between bad and the best.) If your team isn’t great enough to challenge for a championship each season, and is merely average, that’s the worst position to be in. For Hinkie, it’s far better to be last place and get a top draft pick (the NBA rewards the worst teams each season with the chance to select the best prospects the following year). Thus, Hinkie has purposely lost games the past few seasons in order to stockpile good young talent. Of course, his approach is hardly foolproof, since banking on potential is a somewhat rocky foundation, and many critics are convinced that he’s too smart for his own good.

On the court, the concern is what happens when everything is so scrupulously evaluated to the point that the best outcome is always predetermined. What happens when every team is employing the same strategies deemed to be the most effective? Does it take all the unpredictability—the magic—out of the sport?

Likely not. Basketball—like most team sports—is a fluid entity that melds and ultimately changes with the times. The three-pointer obsession the league currently has will eventually give way to something else, as defenses adjust and adapt accordingly. As Grantland’s Zach Lowe pointed out recently, the ubiquity of the three-point shot has inadvertently re-opened space for the post-up game, a prominent strategy in the ‘90s that’s rarely used today.

Goldsberry, like many other fans, only sees analytics improving basketball. “People say that analytics are taking the fun out of it, I think the NBA is in a better position now than it’s ever been,” Goldsberry said. “The league is more analytic ... and I think more aesthetically pleasing, than ever before.”

'We Doubt That Is What Congress Meant to Do'

The Affordable Care Act survived its second major challenge at the U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday. In a 6-to-3 decision, the justices ruled that the Internal Revenue Service can continue to provide health-insurance subsidies to middle-class people living in all states.

At issue in the case, King v. Burwell, was whether the subsidies should go to residents of the roughly three dozen states that use the federal health-insurance exchange, in addition to those who live in states that run their own exchanges.

It’s a highly technical difference, but had the decision gone the other way, Obamacare might have unraveled. Individuals who receive these subsidies make less than $48,000 per year, and many would struggle to afford health-insurance plans without the government’s financial help. Health-policy analysts feared that, without the subsidies in place, healthy people would withdraw from the health-insurance exchanges in large numbers. That, in turn, would cause premiums to skyrocket, making insurance unaffordable to almost anyone who does not receive insurance coverage through their jobs.

The Affordable Care Act gave states the option to either set up their own exchanges or to rely on the federal government’s marketplace through Healthcare.gov. The part of the law that describes the subsidies said they should only apply to people in the exchanges “established by the state.” The plaintiffs in the King case said that clause meant the IRS was offering subsidies to residents of federal-exchange states illegally.

Related Story

In the opinion of the Court, Chief Justice John Roberts dismissed the idea that the fate of the entire Obamacare law should hinge on such a technicality.

“In petitioners’ view, Congress made the viability of the entire Affordable Care Act turn on the ultimate ancillary provision: a sub sub-sub section of the Tax Code,” he wrote. “We doubt that is what Congress meant to do.”

Many patient advocates cheered the decision. “It means that millions of people with serious health conditions such as cancer will continue to have access to essential treatment and care, and millions of others at risk for disease will be able to afford preventive screenings and tests that could save their lives,” said Chris Hansen, president of the American Cancer Society’s advocacy arm, in a statement.

Justices Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito dissented, writing, “Words no longer have meaning if an Exchange that is not established by a State is ‘established by the State.’”

Roberts concludes by saying that the Court is attempting to respect what Congress hoped to accomplish in passing the law: “Congress passed the Affordable Care Act to improve health insurance markets, not to destroy them.”

There are still a few, more minor, legal challenges to Obamacare remaining. But at least for now, the law lives to see another day.

What's So Bad About Segregated Housing? Your Thoughts

Over the past six months, my colleague Alana Semuels has covered the contentious issue of affordable housing, reporting from places like Chicago, Detroit, Louisville, New York City, the Texas cities of Beaumont and Austin, and Amherst, Massachusetts. That issue came to a head on Thursday when the Supreme Court ruled that policies that result in segregating minorities in poor neighborhoods, even if unintentional, violate the Fair Housing Act. “This is a big deal for housing rights and civil rights groups, and a bit of a surprise,” writes Amy Howe at SCOTUSblog.

What exactly was at stake in this case? From Alana’s preview of Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. The Inclusive Communities Project, posted over the weekend and updated this morning in light of the ruling:

[B]uilding more low-income developments in high-poverty neighborhoods perpetuates class segregation, and Inclusive Communities argues it also perpetuates racial segregation. [...] Though Texas might not have been intentionally discriminating against minorities in the allocation of its tax credits [for affordable housing], its policies still had a “disparate impact” on minorities by segregating them in high-poverty areas, Inclusive Communities argues.

The Supreme Court case centers on whether Texas had to be discriminating against minorities on purpose to be found unlawful. After all, it’s difficult to prove that anyone had the intention to discriminate. It’s much easier to prove that an action had a discriminatory effect—and the evidence is clear that the policies did segregate families in Texas.

A lot of readers don’t see that de facto segregation as something the federal government should be trying to fix. Here’s TwoHatchet, the most prolific conservative in our comments section:

White people wanting to live apart from black people is not white people oppressing black people. Angelina Jolie is not oppressing me by not wanting to have anything to do with me.

Commenter Ed takes issue with another quote from Alana’s piece:

“If you want people of color who are low-income to be able to have an opportunity to live in a suburban community, you have to get a tax-credit development out there,” [fair housing advocate John Henneberger] told me.

This quote is devoid of logic. If people can afford the suburbs, they can live there. If they can’t afford it, why should the government put them there? Stop with the social engineering and go find something else to prove you’re a saint on Earth.

(This July 19, 2013 photo shows Jesus Medrano and Edwin Chavez on the swings at an affordable housing complex in Watsonville, California. In the bricked plaza, strolling musicians wearing glitzy cowboy outfits blast a mariachi song, while Spanish-speaking shoppers bustle between farm stands. Welcome to an increasingly typical town in California, a state where Hispanics become the largest ethnic group this summer. As the Golden State becomes less and less white, communities are becoming more segregated, not less. Marcio Jose Sanchez / AP)

ThinkingCritically has a more considered take:

No community can make a rule that minorities are not allowed. You are overlooking the common sense notion that people want to live among their economic peers, and that should be ok. Your economic peers are more likely to maintain their property at the same level you do. They won’t want to steal your stuff because their stuff is just as nice. And you probably don’t have worry about them setting a worse example for your children than you might already be setting.

So to use race and class interchangeably in this context muddies the waters. I for one would much rather live in a neighborhood where I am the only white person and all the other minority residents shared my same financial situation, rather than live in a big house in a trailer park full of destitute white people.

Race and class do have a correlation due to historical misdeeds, it is true. But depriving people of the right to live among those of their same socioeconomic status is not the only way to correct them.

TwoHatchet’s bottom line: “Government has no business in choosing to legally enforce segregation or integration, both of which can be executed by individuals exercising their choice.” Lisa Rice retorts:

Ahhh, but the problem is that for over a hundred years, our government did sponsor and support segregation. The Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968 to remedy that.

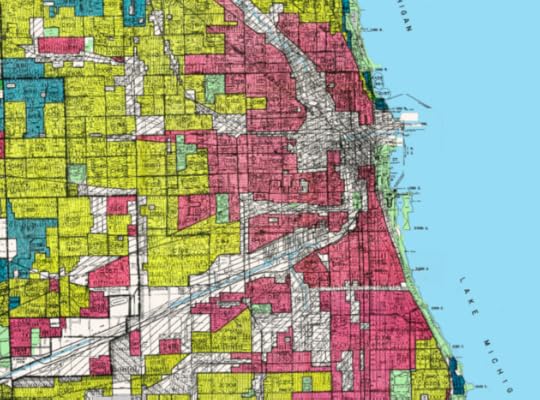

My colleague Ta-Nehisi Coates delved into that history in “The Case For Reparations,” which centers on the redlining of poor neighborhoods that prevented black families from getting federally-backed mortgages in Chicago for decades before the practice was outlawed in 1968.

(A 1939 Home Owners’ Loan Corporation “Residential Security Map” of Chicago shows discrimination against low-income and minority neighborhoods. Courtesy of LaDale Winling of urbanoasis.org)

(A 1939 Home Owners’ Loan Corporation “Residential Security Map” of Chicago shows discrimination against low-income and minority neighborhoods. Courtesy of LaDale Winling of urbanoasis.org) While the conservatives in our comments section have some compelling points, the most interesting part of the housing debate is between liberals with the same general goal—improving the lives of poor minorities through government intervention—but who advocate for different approaches. One major approach is to encourage poor families to move to wealthier communities using vouchers and affordable housing. The opposite approach is to use that money to invest in poor families within their existing neighborhoods. (Of course many liberals want to pursue both tracks simultaneously, but to some extent the investment is zero sum.)

One liberal commenter, Harvey Marx, maintains that housing segregation isn’t necessarily a bad thing:

Putting poor people in rich neighborhoods doesn’t really work—for the poor people. Most things in the suburbs are more expensive in absolute terms even before you start flailing to keep up with the Joneses. And your household will be under constant suspicion and your kid is gonna wind up a scapegoat for unrelated normal suburban delinquency.

The poor shouldn’t be shuffled around. We should build better neighborhoods with more opportunity for the poor.

Applauding that view is Arclight, who has financed, developed, and managed affordable housing for more than a decade:

You are totally correct, Harvey Marx; suburbs often don’t have the public transportation or social service infrastructure you want to see with affordable housing, and they don’t have the same concentration of jobs as one sees in the urban core. Do we really want to use a federal incentive to attract investment capital to areas that are already on solid ground?

Having spent most of my career in this industry—and one that leans decidedly left—I would honestly say that 90 percent of the people I know would prefer that the Inclusive Communities program is overwhelmingly used to target disinvested properties. Many of these areas will just get more rundown, and I don’t think that’s a fair tradeoff so a couple hundred units get built in the suburbs every year.

JoshN1 details more reasons why suburbs “are not a good place for the economic well-being of poor people”:

A suburb typically forces a family to have at least two reliable cars. Even if one of the parents stays home, he or she will need a car to run errands and shuttle the kids around. Poor people cannot really afford to have two cars.

The “amenities” of suburbs are typically not accessible to the poor anyway. They are typically expensive (e.g., public pools that charge $400 a year in membership fees) or not open to the poor (e.g., expensive and exclusive private golf clubs and gyms). Moreover, suburbs typically have limited social services such as food pantries, social workers, domestic violence shelters, free medical clinics, and doctors who take Medicaid that poor people may need at some point.

Suburbs also typically don’t have good low-skill jobs nearby. Most suburban jobs require very high skills or are low-wage service jobs. Most suburbs have very limited jobs trades, construction, or manufacturing.

So, the only benefit identified is that a handful of poor kids get to go to school with rich kids. That is hardly good public policy.

(Newly-built and rebuilt houses line U Street in northwest Washington, DC, on February 27, 2004. Housing for the poor is trying to look as much as it can like the houses of the more affluent houses down the street. Manuel Balce Ceneta / AP)

Jerimiah Johnson argues that money invested in suburban housing doesn’t stretch as far as investment in poor neighborhoods:

Putting taxpayer funded housing in lower land-valued areas allows the programs to build more houses due to the lower-valued land. It funds more people who temporarily need a handout to help them become self sufficient.

JoshN1 adds:

You have to wonder if some self-styled “housing advocates” are really just looking for easy routes to do their advocacy. Building cheap apartments in a wealthy suburb is probably easier and more immediate than trying to improve a poor neighborhood over a period of decades.

Another “dedicated liberal,” bdphd, suggests that the entire housing debate is a distraction:

Section 8 vouchers themselves are a problem and would be better switched to pure income support. Frankly, most housing policy is a sideshow to the real problem: poor people without access to good, well-paying jobs and benefits. Tackle that and housing and segregation problems will largely solve themselves.

Christine, on the other hand, sticks up for integration:

Because without integration there is no real development. Poverty just remains entrenched. When you cluster poverty, it ends up having a multiplier effect in terms of social ills (violent crime, unemployment, blight, disinvestment, etc). When you decluster poverty and integrate, you introduce inter-generational mobility because the people encounter people unlike themselves and begin to strive more.

Complicating that view is my colleague Hanna Rosin’s 2008 piece “American Murder Mystery,” which shows how the spike in violent crime in parts of suburban Memphis after 1997 mapped perfectly with the relocation of citizens with Section 8 vouchers following the closure of housing projects in the inner city:

If replacing housing projects with vouchers had achieved its main goal—infusing the poor with middle-class habits—then higher crime rates might be a price worth paying. But today, social scientists looking back on the whole grand experiment are apt to use words like baffling and disappointing.

Commenter ptullis counters:

This article had it precisely backwards! Three NYU public policy professors have analyzed the data from Memphis and nine other cities and this is what they found:

We find little evidence that an increase in the number of voucher holders in a tract leads to more crime...There is strong evidence for the reverse causal story, however. That is, the number of voucher holders in a neighborhood tends to increase in tracts with rising crime, suggesting that voucher holders are more likely to move into neighborhoods when crime rates are increasing.

MaryOK, on the other hand, observes that “the Chicago Housing Authority found crime higher in neighborhoods with relocated people.” Here’s a great video from that link detailing those findings:

What about the reverse process—white people integrating into black, working-class neighborhoods? Here’s Abe’s Ghost on the g-word that rankles many liberals:

Wanting integration and not wanting gentrification are incompatible: either mixed-race neighborhoods are preferable or they are not. I found this piece by Daniel Hertz to be a fair take on the situation.

[“Let’s face it,” John McWhorter wrote back in February, in response to Spike Lee’s rant about white hipsters moving into black neighborhoods in Brooklyn. “The reason there were black communities like that was because of segregation…. [N]o matter how beautiful they would look when shot lovingly in films like Lee’s, it would signify racial barriers…. When racial barriers come down, people mingle, cohabitate, mate.”]

I want to do away with the disproportionate spread of economic and political power in our cities that results from our history of white supremacy but I don’t know the best way to go about it. I tend to think that mix-raced neighborhoods would help overcome that. But I don't really see the difference between integration and gentrification in this context and I tend to regard the tendency among my fellow progressives to praise integration while damning gentrification to be contradictory.

If I’m missing a meaningful distinction, I’d be glad to hear it.

As would we. Email hello@theatlantic.com and I’ll update the post with your best arguments or personal experiences with public housing or gentrification. And stay tuned for a full analysis from Alana on today’s ruling.

June 24, 2015

The Importance of a Careful Pre-Flight, Cat Fancier Edition

Everyone in the flying world has seen this video. But not everyone in the world at large has, so here you go.

For context, the clip shows a male pilot taking off in a small ultralight craft from what is reported to be the airport in Kourou, French Guiana. Riding along with him is a female passenger on what the pilot says is her first small-aircraft trip. And riding along with them is another passenger, who makes an appearance about 40 seconds in.

Additional study notes:

The ten seconds seconds starting at time 1:00 are wonderful found-art comedy, as the pilot discovers that his aircraft has three rather than two “souls on board.” If this were a cartoon, the pilot’s eyes would be popping out ten inches from his head. Kourou is the site from which the French space program has launched its rockets. I’m not sure, but I think the Arianespace launch facility is what you can see in the background starting at around time 1:30. The pilot shows admirable sangfroid in getting his craft back on the runway quickly once he discovers what he had missed before takeoff. But in this he is matched by unflappability of his extra passenger, from about 1:45 onward. The human passenger seems to be having a good time throughout.In notes with his YouTube video, the man at the controls tells us:

Ok some details :

- the cat was INSIDE the wing, not on it. she was actually pretty safe in there, the danger was if she wanted to get down to reach us..

- i was the pilote, the woman was on her first flight as a passenger. she smile and giggle a lot, well because that's what flying does to people sometime.

-i told her not to reach for the cat. i told her not to move at all actually. i trusted the cat to not move if we didn't try to reach for her.

-you can see me fly shortly before landing. I was pretty assured by then that the cat wouldn't move and there was a relieve of tension; and the radio exchange with the control tower was kinda hilarious, i couldn't contain a smile.

Each decade I am allowed to post one cat video. Check with me again after 2020. Posting this one is in fact obligatory, given that it combines the themes of freedom-of-the-skies and the nature-of-cats. That is all.

Mr. Robot: A Dark, Compelling Drama for the Paranoid Internet Age

Elliot, the hacker protagonist of USA’s new drama Mr. Robot, looks like the dark corners of the Internet in human form. As played by Rami Malek, he’s pale and nervy-looking, and would be easy to miss in a crowd if it weren’t for his hollow stare. Elliot suffers from crippling social anxiety and mostly interacts with people by stalking them online, but he’s a well-meaning hacker, who despises his day job at a banking conglomerate and works at night to try to overthrow it. This, it seems, is the closest thing the 21st century gets for a hero: Despite airing on a typically stodgy network and being saddled with a ridiculous title, Mr. Robot is an angry, surprisingly effective screed against the current inequities of the world.

Much of this is thanks to Malek’s outstanding lead performance, which shoulders the burden of ranty voice-over narration (typically the death knell for a show’s credibility) and invests Elliot with sympathy, despite the fact that he’s, well, a bit of a creep. The hour-long pilot, which has been airing on YouTube for weeks but premieres on USA tonight, sets larger plot arcs in motion and has plenty of typical story elements seen a million times before, like Elliot pining for a pretty coworker. What feels different is that it’s presenting an antihero who doesn’t repeat the established norms of the role. Elliot isn’t some roguish charmer who can’t control his darker impulses—he’s a clinically depressed young man lashing out at a society he can’t fit into. That doesn’t mean he isn’t doing the right thing, but much of the show’s tension revolves around the question of whether he’s doing it for the right reasons.

Related Story

Hacking and the Future of Warfare

A creature of the Internet, Elliot does cybersecurity for the evil corporation that employs him while exposing evildoer CEOs in his side gig as an online vigilante. As he explains to his first target, a coffee-shop owner who downloaded child pornography, Elliot initially started investigating the owner’s servers just because he used the wi-fi at his cafés and couldn’t help but snoop. He can’t summon up the courage to show up at a friend’s birthday drinks, but he happily worms his way into everyone’s private information online. Sometimes, he catches criminals in the act, but at other times, like when he’s with his therapist (Gloria Reuben), his meddling feels like a downright violation. Elliot knows the dark secrets of everyone in his life, even if he never speaks up to reveal them.

The show’s creator, Sam Esmail, who wrote Mr. Robot as a feature film before adapting it for television, is clearly hoping to underscore how vulnerable privacy is in the Internet age. On social media, people reveal much about their personal lives, and the rest is laid bare via bank accounts, investments, and the like, leaving many vulnerable to the machinations of Elliot and friends. Mr. Robot does well in cultivating a sense of paranoia without coming off across like a lecture on the perils of the 21st century—there’s no need for it to mention the NSA, or Edward Snowden, or any other real-life horror story of online surveillance out loud, since it’s so woven into the fabric of the show.

Elliot’s online Robin Hood act attracts the attention of a grungy hacker called Mr. Robot (Christian Slater), who invites him to join his mysterious collective and upend the corporate system on a much larger scale. This is where the show skates closest to the long-standing clichés of hackerdom, dating back to ‘90s camp classics like Johnny Mnemonic or Hackers, which essayed that subculture as a collective of super-cool punks in army jackets wearing offbeat accessories (goggles, spiked collars) and ranting against the man. Mr. Robot, naturally, dresses like a homeless person and runs his operation out of an abandoned warehouse in Coney Island.

It’s a little cutesy, and Slater has never been the kind of performer who plays small. But Mr. Robot manages to pull it off, partly because it needs levity (Elliot’s house-bound stalking feels very grim at times) and partly because the set-up gives the show the kick it needs to serve as a long-term prospect. This isn’t just a diatribe against the system that rumbles about wealth inequality and the ongoing misdeeds of the one percent. It’s a dark fantasy that might actually see that system overthrown, and explore the consequences, good and bad. The show wants viewers to root for Elliot, but not without forgetting that he represents something frightening. There’s a self-seriousness that might not have been predicted from a show called Mr. Robot, but if viewers can run with it, it could be one of TV’s most surprising summer discoveries.

That Time the CIA Bugged a Cat to Spy on the Soviets

My favorite story about American spying is one I've never been able to verify with the Central Intelligence Agency, and not for lack of trying.

At the height of the Cold War, the story goes, officials in the United States hatched a covert plan to keep tabs on Russians in Washington, D.C. They would, they decided, deploy surveillance cats—yes, actual cats surgically implanted with microphones and radio transmitters—to slip by security and eavesdrop on activity at the Soviet Embassy. The project went by the thinly disguised code name “Acoustic Kitty.”

“They slit the cat open, put batteries in him, wired him up,” said Victor Marchetti, who was an executive assistant to the director of the CIA in the 1960s, according to an account in Jeffrey Richelson's 2001 book, The Wizards of Langley. “The tail was used as an antenna. They made a monstrosity.”

A whiskered, yowling, unbelievably expensive monstrosity. The agency poured some $10 million into designing, operating on, and training the first Acoustic Kitty, according to several accounts.

When it came time for the inaugural mission, CIA agents released their rookie agent from the back of a nondescript van and watched eagerly as he set out on his mission. Acoustic Kitty dashed off toward the embassy, making it all of 10 feet before he was unceremoniously struck by a passing taxi and killed.

“There they were, sitting in the van,” Marchetti recalled, “and the cat was dead.”

The CIA eventually scrapped the project, concluding—according to partially redacted documents in George Washington University's archives—that despite the “energy and imagination” of those involved, it “would not be practical” to continue to try to train cats as spies. I mean. Yeah. Good call, guys.

In the popular imagination, spying evokes fancy gadgets like lipstick pistols, briefcase cameras, microphones hidden in loafers, and the occasional tricked-out surveillance cat. And yet the most impressive government surveillance efforts have always been built around the comparatively mundane infrastructure of ordinary communications networks.

And those networks, in addition to enabling intelligence-gathering on huge scales, rarely discriminate between diplomatic friend or foe. The United States isn’t just interested in keeping tabs on its enemies; it has a robust history of spying on its allies and its own citizens as well. Which is probably why the revelation this week that the National Security Agency secretly spied on the last three French presidents provoked plenty of outrage—but not a whole lot of surprise. The U.S. has always leveraged the dominant technological systems of the day—whether telegraph, cell phone, satellite, or undersea cable—to spy on its friends.

Like when, in 1862, President Abraham Lincoln gave his secretary of war, Edwin Stanton, sweeping surveillance power that included, as The New York Times reported, “total control of the telegraph lines” and a means by which to track “vast amounts of communication, journalistic, governmental and personal.” Stanton's authority was so vast—he ended up influencing the news that journalists published—that it prompted a congressional hearing on the matter of “telegraphic censorship.”

Or how U.S. military officials convinced the country’s three major telegraph companies to give the Army copies of all telegrams sent to and from the United States during World War II. Or that time when the NSA tapped German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s cell phone. Or when the United States secretly tracked billions of phone calls made by millions of U.S. citizens in the 1980s and 1990s. Another way to think about it: If the technology exists for communicating, it has probably been used for eavesdropping. (Remember: We're talking about a government that has trained cats, dolphins, and pigeons as spies.)

“Let’s be honest, we eavesdrop, too,” a former French foreign minister, Bernard Kouchner, told a French radio station in 2013, according to an account by the Associated Press. "Everyone is listening to everyone else. But we don’t have the same means as the United States, which makes us jealous.”

Much of the outrage about spying revelations is “faked for public consumption,” Max Boot wrote for Commentary Magazine that year. “Does the NSA spy on your leaders? Probably. Do you spy on leaders of allied states including the United States? Probably. You just don’t have the resources or capability to spy as effectively as the NSA does. But if you did, you would.”

How Housing Policy Is Failing America's Poor

When a woman in McKinney, Texas, told Tatiana Rhodes and her friends to “go back to your Section 8 homes” at a public pool earlier this month, she inadvertently spoke volumes about the failure of a program that was designed to help America’s poor.

Created by Congress in 1974, the “Section 8” Housing Choice Voucher Program was supposed to help families move out of broken urban neighborhoods to places where they could live without the constant threat of violence and their kids could attend good schools.

But somewhere along the way, “Section 8” became a colloquialism for housing that is, to many, indistinguishable from the public-housing properties the program was designed to help families escape.

More From Confirmed: Millennials' Top Financial Concern Is Student-Loan Debt The Institution of Marriage: Still Going Strong Millennials Are in Search of a Different Kind of Career

Confirmed: Millennials' Top Financial Concern Is Student-Loan Debt The Institution of Marriage: Still Going Strong Millennials Are in Search of a Different Kind of Career How did this happen? To begin with, Section 8 is poorly designed. It works like this: Families lucky enough to get off lengthy waiting lists are allowed to look for apartments up to a certain rent, which varies for each metro region. This figure is called the “fair market rent,” and is calculated by HUD every year for each metro area. The tenant pays about 30 percent of his income, and the voucher covers the rest of the rent (this is based on the idea that families should not spend more than one-third of their income on rent).

But the fair market rent cut-off point often consigns voucher-holders to impoverished neighborhoods. This is in part because of how that number is calculated: HUD draws the line at the 40th percentile of rents for “typical” units occupied by “recent movers” in an entire metropolitan area, which includes far-flung suburbs with long commutes and, as a result, makes the Fair Market Rent relatively low. In New York City, for example, the Fair Market Rent for a one-bedroom is $1,249, a price that would relegate voucher-holders to the neighborhood of Brownsville in Brooklyn, one of the most dangerous places in the city, and where the most public housing is located.

Technically, voucher holders can live anywhere in a region that meets the price restrictions. But the tendency is for people to stay in neighborhoods that are familiar to them, though a few areas have created robust mobility-counseling programs to try and mitigate this. Additionally, as Eva Rosen has detailed, landlords in low-income areas aggressively recruit voucher-holders, as the vouchers are a much more reliable source of rent than other low-income tenants have available.

The failings of Section 8 go far beyond flaws in how the program was designed to how the the states have implemented it. People can argue all they want about the merits of subsidized housing, but given that Section 8 exists, it would seem advantageous for states and municipalities to take advantage of federal funds to help families find better housing. But many states seem especially determined to keep voucher-holders in areas of concentrated poverty.

“The whole idea of Section 8 in the beginning was that it was going to allow people to get out of the ghetto,” said Mike Daniel, a lawyer for the Inclusive Communities Project, told me. (Daniel has sued HUD over the way it is carrying out the program in Dallas.) “But there’s tremendous political pressure on housing authorities and HUD to not let it become an instrument of desegregation.”

For example, in much of the country, landlords can refuse to take Section 8 vouchers, even if the voucher covers the rent. And, unlike the landlords in poor neighborhoods in Eva Rosen’s study, many landlords of buildings in nicer neighborhoods will do anything to keep voucher-holders out. The result is that Section 8 traps families in the poorest neighborhoods.

One study in Austin found that there were plenty of apartments around the city that voucher-holders could afford. But only a small portion of those apartments would rent to voucher-holders.

The report, by the Austin Tenant’s Council, found that 78,217 units in the Austin metro area—about 56 percent of those surveyed—had rents within the Fair Market Rent limits. But only 8,590 of those units accepted vouchers and did not have minimum income requirements for tenants. Most were located on the east side of Austin, in high-poverty areas with underperforming schools and high crime rates. (The survey only looked at apartment complexes with at least 50 units.)

“Families don't have very many choices as to where they can actually use the voucher,” said Nekesha Phoenix, the Fair Housing Program Director at the Austin Tenants’ Council. “Although there are properties north and west that they could actually afford to live in, they can't do it because the properties won't take the voucher.”

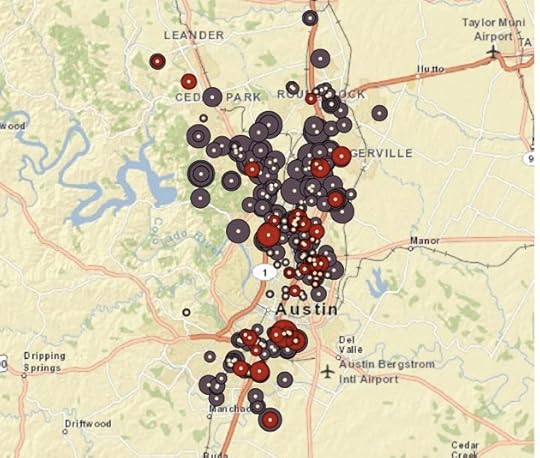

The purple and red dots represent apartments in Austin that cost Fair Market Rent or less. Red dots represent the apartments that would accept Section 8 vouchers. Austin’s west side, which is wealthier and has better schools, is close to devoid of options for voucher-holders. (Austin Tenants Council)

The purple and red dots represent apartments in Austin that cost Fair Market Rent or less. Red dots represent the apartments that would accept Section 8 vouchers. Austin’s west side, which is wealthier and has better schools, is close to devoid of options for voucher-holders. (Austin Tenants Council) Some cities have tried to prevent this. Last year Austin passed a “Source of Income” ordinance that prohibited landlords from refusing to rent to people solely because they have a voucher. And 12 states, as well as the cities of Los Angeles, San Francisco, Washington D.C., Chicago, and Philadelphia have all done the same.

But in Austin the landlords successfully pushed back. The Austin Apartment Association sued the city over the ordinance, asking for an injunction to block it. The apartment owners say that being forced to accept Section 8 meant more paperwork, onerous lease terms, and “burdensome inspections.” (Section 8 properties have to be inspected to ensure they are sanitary and safe.)

After a district judge left the law standing, the Texas legislature in May passed a bill banning any municipality from passing Source of Income ordinances. Source of Income discrimination will once again become legal in Austin when the state law goes into effect in September.

“A housing authority that on its own set out to use housing choice voucher as an instrument of desegregation would be brought to its knees by the elected officials of the cities that they’re in,” Daniel told me.

Why do some landlords try so hard to attract voucher-holders and others try so hard to avoid them? Section 8 tenants pay the rent reliably and stay in apartments for longer than market-rate tenants, according to Isabelle Headrick, the executive director of Accessible Housing Austin!, who is also a property owner. Though the apartment owners’ lobby had said that Section 8 requires landlords to sign a 400-page document and makes it more difficult to evict tenants, Headrick says that the contract is only 12 pages, and that the inspections required are “no more difficult than what a responsible landlord should be doing anyway.”

“Having Section 8 tenants makes my job easier, not harder,” she said.

But in Dallas, the Inclusive Communities Project found that some landlords who owned many units throughout the city would rent to voucher-holders in low-income neighborhoods, but not in high-income neighborhoods, even if the tenants could afford both apartments. Though the landlords would say they refused the vouchers because they didn’t want to deal with the paperwork, housing advocates say that property owners don’t want Section 8 tenants (read: minorities) in buildings because they might drive away market-rate tenants.

The Inclusive Communities Project sued HUD over the way it calculated Fair Market Rents in Dallas. It is now trying to make an arrangement with Dallas-area landlords so that it can rent apartments from them and then sublease them to Section 8 tenants, taking away landlords’ excuses for not wanting to deal with Section 8 paperwork. (Daniel also sued the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs over how it distributed tax credits for low-income housing, a case the Supreme Court will rule on in the next few days.)

“The idea that Section 8 people should be required to stay in areas of slum and blight—at some point they’re going to realize that’s just racial segregation,” Daniel told me.

Often, voucher-holders in Austin have such a hard time finding housing that they need to ask for multiple extensions to find housing. Tenants lose the voucher if they don’t use it in 60 to 90 days.

David Wittie, a voucher-holder in Austin, ran into this problem when he was looking for a new place last year. Wittie called around and found a few places that said they took vouchers. But by the time he got on a bus and arrived at the apartment building to sign a lease, the units would be rented. Wittie, who has been in a wheelchair since he contracted from polio in 1956, said that he had to ask for three extensions before he found a place.

“All I wanted was to find a nice place to live,” he told me.

In cities such as Austin, where rents are rapidly rising because of an influx of new, affluent residents, voucher holders may be having even tougher times finding a place to rent because the cost of housing has gotten so expensive. There are no rent-control laws in the state of Texas, and rents in Austin have gone up 7 percent over the past year, making it nearly impossible to find a place that is affordable with a voucher.

The result is that voucher-holders are pushed farther out from a city’s core, and into buildings that are dilapidated and have multiple code violations: In 2012, city enforcement officers ordered an apartment complex in Austin evacuated after a second-floor walkway sagged and then collapsed. Officials blamed termite damage, and said the low-income and Section 8 voucher-holders were hesitant to report unsafe conditions because they knew how hard it was to find an affordable place to live and didn’t want to be evicted.

Rufus Jones, a 51-year-old visually-impaired voucher-holder, had to look for a new apartment two years ago when the building where he’d lived for 13 years was sold to a new owner who quickly raised the rent. After months of searching, Jones moved into a place that soon became nightmarish when he discovered it was infested with cockroaches. The apartment was located in a noisy building where the hot water often didn’t work and where the sewage pipes leaked, but the final straw came when a roach crawled into Jones’s ear when he was sleeping and he had to go to the ER to get it out.

Rufus Jones, a visually-impaired Section 8 tenant, outside his rat-infested apartment (Alana Semuels)

Rufus Jones, a visually-impaired Section 8 tenant, outside his rat-infested apartment (Alana Semuels) It took Jones a long time to find the place he now lives, since fewer and fewer apartments would accept vouchers. But when I visited him at the apartment, a low-slung building on the far north side of Austin, he told me it wasn’t much better.

His new place is infested with rodents, which crawl into his bedroom and bathroom through holes in the wall, waking Jones’s service dog and Jones himself. Jones’s current place is only on one bus line, and he’s now once again going through the process of finding his way around a new neighborhood.

“It’s just so horrible right now—I can’t sleep, and I’m stressed out the whole time,” he told me.

* * *

The Housing Choice Voucher program is the nation’s largest housing subsidy, serving 2.2 million families, which is still only about 25 percent of eligible households. It makes up a big part of the government’s efforts to improve housing conditions for America’s poorest families. Advocates have called time and again for HUD to alter the Housing Choice Voucher program to make it a better tool for families to improve their lots in life, and some changes are afoot.

“There’s a growing recognition that there’s a shortage of affordable housing, and that families with vouchers have a hard time using them in neighborhoods and communities that haven’t traditionally had voucher families in them,” said Phil Tegeler, the executive director of the Poverty & Race Research Action Council.

As the result of a settlement, HUD tested a new program in Dallas and a few other metro areas that calculates fair market rent based on zip codes, rather than for a metro area as a whole. Called the Small Area Fair Market Rent Program, the idea is to make the voucher more valuable to landlords in nicer neighborhoods. Under the program, if a voucher holder wants to rent a place in the 75231 zip code, the Vickery Park area of Dallas, the voucher would support a rent up to $580 for a one-bedroom. Vickery Park is a lower-income area that gained notoriety as the home of America’s first Ebola victim. But if a voucher holder wants to rent an apartment in Forney, Texas, zip code 75126, the voucher would cover rent of a one-bedroom up to $1,090. Forney has some of the lowest crime rates in the state, and has also been designated the “Antique Capital of Texas.”

A feces-covered rat trap in Rufus Jones’ apartment

A feces-covered rat trap in Rufus Jones’ apartment (Alana Semuels)

A study out of Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies found that the Dallas small-area fair market rent program was successful in helping voucher families move to neighborhoods with lower violent-crime rates and lower poverty rates. Kathy O’Regan, HUD’s Assistant Secretary for Policy Development and Research, told me that the results of that study motivated HUD to use small-area Fair Market Rents in more areas. Earlier this month, HUD sought comments the idea of potentially changing the way Fair Market Rents are calculated.

“We agree with critics—we believe that we should be able to do better,” she told me. “It doesn’t look from geographic patterns as though households are getting enough choice.”

A HUD study also found that public housing authorities are significantly underfunded when it comes to managing Section 8. Administrative costs, which are used to pay for mobility counseling, have been limited by Congress. HUD is asking Congress to consider changing the limits on administrative costs for voucher programs.

“We want to give households choice, choices that help them in improving their lives,” she said.

If Section 8 can be fixed, it’ll be money well spent. The government spends billions of dollars each year creating a program that, for some families, is akin to winning the lottery. But what’s the point of winning the lottery if there’s nowhere safe to spend it?

The Value of Art No One Alive Will Ever Experience

Mark your grandchildren’s diaries: The year 2114 will be an eventful one for art. In May of that year in Berlin, the philosopher-artist Jonathon Keats’s “century cameras”—pinhole cameras with a 100-year-long exposure time—will be retrieved from hiding places around the city to have their results developed and exhibited. Six months after that, the Future Library in Oslo, Norway, will open its doors for the first time, presenting 100 books printed on the wood of trees planted in the distant past of 2014.

Related Story

As Katie Paterson, the creator of the Future Library, puts it, “Future Library ... is an artwork for future generations.” These projects, more than a century in the making, are part of a new wave of “slow art” intended to push viewers and participants to think in time frames beyond their own lifetimes. As initiatives, they aim to challenge the prevailing short-term thinking of contemporary institutions and the brief attention spans of modern consumers, forcing people into considering works more deliberately. In a similar fashion, every April on Slow Art Day, patrons are encouraged to gaze at five artworks for 10 minutes at a time—a tough ask for the average museum visitor, who typically spends less than 30 seconds on each piece of art. But in delaying gratification from art beyond the reach of current generations, “century art” borrows from the ethos underlying the “slow art” movement and extends it even further.

In its way, too, it represents a protest against the commodification of culture—not just regarding money, but also the way in which artistic worth is measured by attention. In an era that prizes “snackable content”—items that are short and easily digestible—century art is the opposite. Some contemporary artists reacting against the idea that art should be accessible and shareable have turned to ephemerality: The popular German-British artist Tino Sehgal, for instance, makes art from fleeting interactions such as kisses and refuses to allow his “constructed situations” to be documented. Century art goes the other way, seeking solidity in the accumulation of time.

In preparation for 2114, Future Library’s editorial panel will choose one book each year for a century, starting with a manuscript from the Booker Prize-winning novelist Margaret Atwood. The unpublished, unread texts (the rules for writers state that the work can be of any length, but must be words, not pictures, and must remain entirely secret) will be stored in a specially designed room in the new Oslo City Library when it opens in 2018. The room, described as “a space of contemplation,” will be lined with the wood of a thousand-tree forest, planted especially for Future Library in the parkland just outside the city.

The work was commissioned by a Norwegian property developer, whose representatives didn’t immediately see the appeal of a project that would remain unseen until long after they were dead. It’s perhaps a question many readers and art patrons share. But for its contributors, Future Library seemed to represent a gesture of faith—in both the written word and in humanity itself. “It’s very optimistic to do a project that believes that there will be people in a hundred years [and] that those people will still be reading,” Atwood said when she accepted the commission. The second writer chosen for the project, the English novelist and Cloud Atlas writer David Mitchell, said he agreed to participate because “contributing and belonging to a narrative arc longer than your own lifespan is good for your soul.”

It’s a sentiment with some precedent. Astronauts who see the Earth from space report a profound sense of wholeness, as worldly divisions fall away and the fragility of life becomes suddenly very apparent. The philosopher Frank White coined the phrase “overview effect” to describe the experience. As he told the makers of the 2012 short film Overview: “[Astronauts] see things that we know but we don’t experience, which is that the Earth is one system, we’re all part of that system, and there is a certain unity and coherence to it.” Looking at humanity from the grand overview of generational time seems to produce a similar shift in perspective.

A related desire for intergenerational connection motivated the century cameras project. Keats, a conceptual artist who has previously copyrighted his own mind and served gourmet sunlight to plants, invited one hundred Berliners to rent steel pinhole cameras, calibrated to let in light gradually over the course of a century. In exchange for a €10 deposit (to be returned in 2114, if the currency still exists), the new photographers could plant their century cameras anywhere around the city. If the devices remain stable, the resulting photographs will provide a compressed image of the passage of time itself, with buildings knocked down after 30 years appearing as a faint white blur, while the constant rush of traffic on a busy road emerges as a permanent landmark.

What will future generations make of century art, and will they see it as the gift that it’s intended to be?Keats, who has also initiated century camera projects in San Francisco and Phoenix, Arizona, sees the devices as a form of benign surveillance. The cameras function as an invisible spectator, prompting city-dwellers to think about the impact of their actions on future generations. Or as Keats put it, “The ways in which the decisions we make tend to most impact those who have the least power, that is to say, those who are not yet born.” Like the Future Library, the century cameras are very much an urban project, since it’s in cities that time runs fastest and the pace of life is most hectic. “Since I became an urban woman ... I’ve somehow been quite disconnected,” said Anne Beate Hovind, the Future Library project manager, who described how working on the library drew her back to the timescale she knew when she was growing up on a farm in her youth.

Works like Future Library and the century cameras raise all sorts of questions, ranging from the existential to the practical. Will any of the cameras survive? If they do, will they produce legible images? Will any of the Future Library works be any good—and does it matter if they are? What will future generations make of century art, and will they see it as the gift that it’s intended to be? More concretely, for those of us wrestling with what the philosopher Matthew Crawford labels “a crisis of attention,” the question seems to be: How can we adopt this attitude now, in everyday life? When we struggle to look up from our smartphones, how can we look beyond the present moment and think broadly and generously across time?

With their deliberate pace, works such as Future Library and the Century Camera Project resemble another Norwegian art form known as Slow TV. These live, uninterrupted broadcasts of ordinary events have become an unlikely hit, drawing millions of viewers to watch hours of knitting, or to observe the five-and-half-day progress of a cruise ship meandering gently along Norway’s western coast. For Keats, however, there’s more to century-long projects than a leisurely pace. “It has less to do with trying to slow down in any way and more to do with being able to experience more expansively the decisions that we make,” he said.

His century cameras are a study for a larger work: a set of millennium cameras that Keats hopes to set up in cities across the world. He’s already installed two, one in Tempe, Arizona, and another in Amherst College in Massachusetts. These copper-and-gold devices will produce images of such density that it may take “tens of thousands of years” to figure out how to develop them.

Deep time, the concept of the timespan within which the Earth has existed (around 4.5 billion years), is enjoying a flood of attention in the art world at the moment. Imagining Deep Time, a recent exhibition at the National Academy of Sciences, collected works that tried to explore and express a history that goes back well before humans existed. Chief among these projects is the Long Now Foundation's 10,000-year clock, a mechanical timepiece that will keep time for 10 millennia. The clock “models for us the creation of projects on a much larger scale than our own individual experience,” said the show’s curator, J.D. Talasek, echoing the rationale of Paterson and Keats. “It raises questions of how you plan for, finance, manage a project that will be in place for generations.”

For all its audacity, however, the 10,000-year clock's sense of its own importance can seem absurd, especially next to the low-cost communal efforts of Paterson and Keats. The first full-scale prototype is being backed to the tune of $42 million by Jeff Bezos, who has also donated space on his Texas ranch, and will have a chime composed by Brian Eno. Best-selling science-fiction author Neal Stephenson, who has also contributed to the Foundation, has written a novel inspired by the clock, including the notion that a quasi-religious order will have to arise to maintain it.

For slow art to succeed, it must be able to grow as time passes.Even more exclusive is another slow-art project that launched this year: the Wu-Tang Clan album Once Upon a Time In Shaolin. Described by its creators as “a capture of time,” the 31-track album is being sold to the highest bidder by private auction, on the condition that it can only be released to the public after 88 years. To preserve the scarcity of their creation, which they expect to sell for “millions of dollars,” Wu-Tang Clan have only made a single copy of the album, carefully destroying all other versions, both physical and digital. For the group, this uniqueness is what makes Once Upon a Time In Shaolin art, as well as justifying its eye-watering asking price. As Wu-Tang member RZA put it, “We’re making a single-sale collector’s item. This is like somebody having the scepter of an Egyptian king.”

At a moment when time is seen as the ultimate luxury, Wu-Tang Clan have turned slow art into a luxury good. By restricting Once Upon a Time In Shaolin to a single, very rich, owner, they’ve also effectively buried their music, thus taking their place in the grand American tradition of time capsules. Whether anyone will still be paying attention in 2103 is another matter—as the historian William E. Jarvis notes in Time Capsules: A Cultural History, most attempts to leave items for the future are greeted by their recipients with a mixture of disappointment and amusement. Will Once Upon a Time In Shaolin meet a similar fate? By the time its contents are available for public listening, the true oddity about the album may be its format: This dazzling one-off, set in a jeweled silver-and-nickel-plated box, is recorded on, of all things, a CD.

For slow art to succeed, it must be able to grow as time passes. Keats’s century cameras will evolve in private, but the Future Library appears more likely to prosper, because it will develop in plain sight, as year by year new writers add their work to the collection. Just as importantly, this time capsule is public in a concrete sense, because it is embedded in the fabric of the city. Atwood and Mitchell refer to the Future Library as a hopeful project, which in an existential sense it is, but its infrastructure does more than hope: It will survive as part of Oslo's institutional framework. Over time, the boundary between the artwork and its location will become indistinguishable—perhaps, the project suggests, the city itself is a form of slow art, created every day by its inhabitants for the benefit of future generations.

Paterson, whose previous works include a map of all the dead stars known to humanity and a live broadcast of the sounds of a melting glacier, admits that the span of the Future Library isn’t “vast in cosmic terms” like the 10,000-year clock. Yet, perhaps because it is closer—only 100 years away—the artwork feels more directly challenging. It is sufficiently awe-inspiring to remind visitors and contributors of their insignificance. But rather than simply daunting with its scale, Future Library prompts those who see it to consider their own role in its survival, not as a generic member of the human race, but as individuals with the capacity to act. “It gives hope,” said Hovind, the project manager. Hope not only in the future, but also in the possibilities of the present.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower