Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 409

June 19, 2015

Blessed Are the Peacemakers

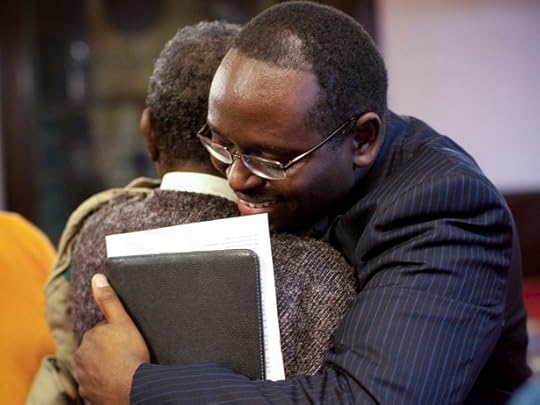

The Reverend Clementa Pinckney, of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, knew he was in a dangerous line of work. He may not have known that particular Wednesday evening would be his last, but he was the rock of a church that had been baptized in blood and fire.

Pinckney certainly knew the story of Denmark Vesey, one of the founders of Emanuel A.M.E., whose church was razed to the ground and whose life was ended because of his efforts to set blacks free. Vesey himself was a free man, and wealthy, and yet he marched boldly and knowingly toward the peril of death by trying to lead a slave revolt. The judges who sentenced him to death remarked on this:

“It is difficult to imagine,” says the sentence finally passed on Denmark Vesey, “what infatuation could have prompted you to attempt an enterprize so wild and visionary. You were a free man, comely, wealthy, and enjoyed every comfort compatible with your situation. You had, therefore, much to risk and little to gain.” Is slavery, then, a thing so intrinsically detestable, that a man thus favored will engage in a plan thus desperate merely to rescue his children from it?

Is slavery so intrinsically detestable that a free and wealthy man will risk death merely to rescue his children from it?

Vesey’s answer? Yes. One of Vesey’s co-conspirators recounted his sentiments: “He was satisfied with his own condition, being free, but, as all his children were slaves, he wished to see what could be done for them."

Vesey’s chief co-conspirator was Peter Poyas, another man who marched boldly toward the peril of death. While in prison, Poyas and a cellmate were tortured and threatened by their jailors to extract the names of their accomplices:

[Poyas’s] companion, wearied out with pain and suffering, and stimulated by the hope of saving his own life, at last began to yield. Peter raised himself, leaned upon his elbow, looked at the poor fellow, saying quietly, “Die like a man,” and instantly lay down again.

Like these men, Pinckney felt his work was both necessary and not safe. “Freedom, equality and the pursuit of happiness,” Pinckney had said to a room of visitors to his church two years prior, “that's what church is all about. Freedom to worship, and freedom from sin, freedom to be fully what God intends us to be, and freedom to have equality in the sight of God. And sometimes you gotta make noise to do that. Sometimes, you maybe have to die, like Denmark Vesey, to do that.”

If you have not yet listened to Pinckney’s recounting of his church and its history, spare 10 minutes and watch.

Clementa Pinckney knew the history of his own city. He probably knew the name Benjamin Franklin Randolph, another black minister and state senator from Charleston to have died at the hands of angry white men, 147 years prior.

He may not have suspected that the person who had joined his small fellowship of believers at Mother Emanuel that night would sit with these few people for an hour, listen to their prayers and their blessings, then take up a gun and end their lives. But he knew that humankind had been cursed from its beginnings by hatred so potent it could be lethal—the third human mentioned in Pinckney’s Bible, after all, had killed another man out of jealousy for what he had.

Much attention will be given to tracing the motives that gave rise to these murders. There will be news broadcasts and lengthy stories about the mind of the killer. At the end, we’ll probably conclude—as Karl Ove Knausgaard did when he reported on the Norwegian killer Anders Breivik—that those motives, whether you call them “hate” or “illness” or “terrorism,” are petty, ancient, and banal.

So let’s spare a thought for those who undertook the dangerous work of prayer and fellowship, and were killed for it. For Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, Cynthia Hurd, Tywanza Sanders, DePayne Middleton-Doctor, Susie Jackson, Ethel Lee Lance, Myra Thompson, the Reverend Daniel Lee Simmons Sr., and the Reverend Clementa Pinckney.

And I don’t know whether they got to say it when their meeting was abruptly and violently ended, so I’ll say it now.

Amen.

How Is the Blackhawks’ Name Any Less Offensive Than the Redskins’?

Hockey’s Stanley Cup is now held by a team with a Native American name. The Chicago Blackhawks triumphed over the Tampa Bay Lightning this week to win the National Hockey League championship for the sixth time. On Thursday a parade honored the team whose logo shows an Indian wearing a feathered headdress.

Washington’s professional football team also has a name referencing Native Americans, and a similar logo—yet the two teams have been received very differently in recent years. Some news organizations avoid saying “Redskins,” a word many Native American groups and linguists consider a slur. In 2014, the federal government revoked the Redskins’ trademark protection, ruling that the name was disparaging.

Related Story

The Blackhawks face less controversy, and have argued that their team name is not a generic racial stereotype. It honors a real person, Black Hawk.

The team may yet face its moment of reckoning. But it’s worth hearing the incredible story behind the name, part of the vast narrative of westward settlement. That story, in turn, points to a new standard that can help citizens decide when, if ever, to favor sports names with Native American themes.

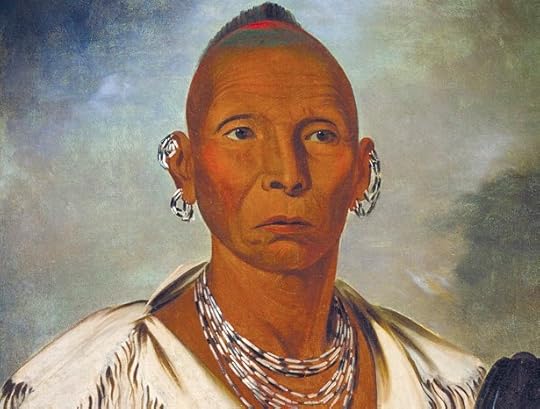

Black Hawk was a leader of the Sauk people, who were pressured to give up Midwestern land in the early 1800s. A treaty they considered unjust forced them out of modern-day Illinois and west of the Mississippi. Like many Indians who opposed land-grabbing American settlers, Black Hawk sided with the British in the War of 1812.

The Sauks got nothing for their war. In 1832 they tried again to recover land they believed to be theirs, crossing east of the Mississippi. The resulting conflict became known as the Black Hawk War. White residents, including a young Abraham Lincoln, volunteered to fight the incursion.

Black Hawk was forced to surrender. He was sent to Washington, and brought before President Andrew Jackson. The president scolded Black Hawk, but soon ordered his release. Jackson also arranged for him to tour Eastern cities, so that he would see he could never defeat a nation so large and powerful.

Black Hawk became a celebrity on that tour, mobbed by curious crowds. “I ought not to have taken up the tomahawk,” he was quoted as saying in Baltimore. “But my people have suffered a great deal.” President Jackson was touring Baltimore at the same time. The former enemies both attended the same stage show, a popular act called Jim Crow, which featured a white man in blackface. (It was a rather different time.)

For some European settlers and their descendants, associating with Indians was part of what it meant to be American.The early 19th century did have one thing in common with the modern era: It was popular for white people to appropriate Indian names and symbols. Long before the Cleveland Indians ever played baseball, there was Tammany Hall, a powerful New York City political organization named for a Delaware Indian leader. Its workers were “braves,” and its leaders were “sachems” or “chiefs.” Artists and writers put native characters in novels and paintings. A famous actor of the 1820s commissioned a play in which he took the title role of Metamora—an Indian chief who denounces white men as they kill him and take his land. For some European settlers and their descendants, associating with Indians was part of what it meant to be American.

Once it’s understood that modern sports teams are choosing to follow a centuries-old tradition, it’s easy to see how perilous their choice can be. White settlers began embracing certain trappings of Indian life even while displacing Indians themselves. Indians were dismissed as wandering savages, “children of the woods,” or … redskins.

But it’s also part of the tradition that some Indians became heroes. Black Hawk’s name was given to a military unit in World War I. A veteran of that unit later re-used the name when he started his Chicago hockey team in the 1920s. Still later, it graced the type of helicopter seen in Black Hawk Down. There was also Osceola, who resisted the drive to remove Seminoles from Florida. In 1835 he murdered a federal agent in what today might be labeled a terror attack. But the government later captured him while he was negotiating under a white flag, an act considered so unfair that today counties in several states are named for him, as is the mascot for the Florida State Seminoles.

So which sports names, if any, are tolerable in 2015?

One common standard is simply whether people are offended. That’s the standard that trademark officials applied to the Redskins case. Of course, not everyone will find the same things offensive. Even as the American Indian Movement has organized protests outside Redskins games, team owner Dan Snyder has called the name a “badge of honor.”

Even as the American Indian Movement has organized protests outside Redskins games, Dan Snyder called the name “a badge of honor.”A different standard is whether a team can find a native group that approves of the name. Even the Redskins have cited some Native Americans who say they aren’t bothered by that particular word. The Blackhawks have the support of the Chicago-based American Indian Center, which has received grants from the team. But this is tricky. The center’s director, Andrew Johnson, who is Cherokee, told me the center held a town hall meeting where many Indians denounced the team name as racist. He said native culture requires “respect” for those different opinions.

There’s also a public wellness standard: The American Psychological Association declared a decade ago that Native American names and mascots created a “hostile learning environment” for native students. But clearly some teams aren’t persuaded.

So here is a new standard. Do we learn anything from the team name? Does the name teach us anything we want to pass on about this country, its history and its people?

If people learn the story behind a team name, they can make an informed decision about whether they approve or not. Indians are part of the American fabric, and it’s not automatically bad to include them in pop culture. The Chicago Blackhawks at least have a case to make, even if it’s one that needs to be weighed against other factors.

It’s not surprising that “redskin” evolved into a word that simply diminishes the people it describes.With other teams, it’s more complicated. The Kansas City Chiefs say they’re named after a former Kansas City mayor whose nickname was “Chief,” but they also use the native image of an arrowhead in their team logo. The Atlanta Braves’ story is awkward. The team is in Georgia, where streets, shopping malls and a county are named for Cherokees, but actual Indians were evicted almost 200 years ago.

Could the Redskins meet the standard?

They’d have to complete a sentence. “It’s important for Americans to think about the word redskin because …” If Redskins fans can complete that sentence and feel proud of it, they’d have a better case for keeping the team’s name.

I asked a Redskins spokesman for the “redskin” story. He pointed out the work of the scholar Ives Goddard, who argued in 2005 that “redskin” was used in colonial times by some Native Americans themselves. They were trying to define the racial difference between Indians and encroaching whites. But the same scholar records the expression used by Indians in an oddly negative way (“I am a red-skin,” one confessed, “but what I say is the truth”), and by whites in a patronizing way (President James Madison referred to “my red children”). It’s not surprising that “redskin” evolved into a word that simply diminishes the people it describes.

Do the Redskins want to hang their identity on that? If so, their name will tell a story that stretches far beyond football, whether their fans want it to or not.

Dope: When High-School Hijinks Are Life-or-Death

Dope opens by showing the dictionary-style definitions of the movie’s title—essentially drugs, dumbass, and cool. But the real keyword for Rick Famuyiwa’s breakout Sundance comedy is on the posters: “It’s hard out here for a geek.” Geek—that’s how the hero, Malcolm, is labeled by himself and the people around him. Which might prompt some skepticism. Are we still making movies about jocks vs. nerds? Didn’t dissing geeks go out in 1985? I remember arriving at high school a certified geek and being surprised that the coming-of-age movies I’d seen had greatly exaggerated the teenage caste system—no one was stuffing anyone in lockers for knowing the order of operations.

Related Story

With Inside Out, Pixar Returns to Form

A few minutes into Dope, though, and you realize that the rules are slightly different for this particular entry into the high-school movies tradition. Yes, like so many other films, it’s about uncool kids falling in with the cool kids and then having their values tested. Yes, Malcolm and his best friends Diggy and Jib worry about bullies, prom dates, and getting into college. At first, it might seem like the movie’s novelty is merely because of racial transposition—maybe it’s a black Breakfast Club, where the geeks’ geekdom mostly comes from their love of ‘90s hip hop and “white shit.”

But the locker-lined hallways depicted in the film are fundamentally different from the ones populating John Hughes films, Superbad, and Mean Girls, less because of the color shift than because of what this particular color shift means in the real world. Being a geek here isn’t just about being obsessed with unpopular stuff; it’s about opting out from cultural expectations as a way to try and survive. Early in the film, it’s established that in the low-income neighborhood of “the Bottoms” in Inglewood, the drug trade is an inescapable part of the social scene, and anyone can be killed for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. This isn’t presented as a big, dramatic stakes-raiser, but rather as a simple fact, as it is for so many Americans. And as with so many simple, horrible facts, it becomes a source of grim humor. A student gets shot during a robbery at a burger shack, and the real tragedy, the narrator says, is that he was seconds away from defeating a level on his Game Boy.

The setup: Despite the armor of geekdom—which makes him either invisible or a joke to most of the people around him—Malcolm unwittingly ends up with a stash of molly and must figure out how to sell it, all the while trying to land the cute girl down the street and mail his application to Harvard. In the process, he tiptoes through gang war zones, allies with a rich white stoner who wants permission to use the N-word, nearly loses his virginity to a character played by the model Chanel Iman, and has the strangest college-admissions interview of all time. If that all sounds like mere hijinks, remember: The guys of 21 Jump Street might get chased by drug dealers or the kids of Dazed & Confused might get roughed up by upperclassmen, but you never really worry anyone’s going to die. Here, as is the case with the other cinematic traditions Dope pulls heavily from—the gangster-narratives of the ‘90s like Boys N the Hood and Juice—bloodshed’s plenty likely. This means you watch all the hijinks unfold with a heightened level of attention, a queasy and bracing mix of amusement and dread.

You watch all the hijinks unfold with a heightened level of attention, a mix of amusement and dread.It helps that the writing is hilarious and dense, delivered with ace comic performances and energetic, fearless style. The 20-year-old Shameik Moore plays Malcolm, emanating natural charisma while also mumbling and stumbling as is appropriate for his character. His pal Diggy, played by Kiersey Clemons, nearly steals the movie as a quick-witted but no-nonsense lesbian, and the rapper A$AP Rocky brings a surprising amount of easy wit as well as danger to his performance as the drug dealer Dom. The pacing’s uneven—contemplative one minute, frenetic the next—but deliberately so, and the effect is almost musical.

It should be obvious by now that in addition to revitalizing a genre, Dope has a social message about being true to yourself and about transcending one’s circumstances without leaving them behind or condemning them. And it joyfully humanizes a group of people too often left to grim stereotyping in pop culture. Forest Whitaker’s hammy narration, and a recitation of Malcolm’s college admission essay toward the end of the movie, puts too fine a point on the film’s political points. But whenever the energy starts to flag or it tempts preachiness, Dope quickly recovers, often with help the soundtrack—a mix of classic and contemporary hip hop plus catchy post-punk from the geeks’ band Awreeoh, whose songs are ghostwritten by the film’s co-executive producer Pharrell. One of Awreeoh’s earworms is called “Can’t Bring Me Down,” and if that title sounds trite, by the end of the film, in the context of these geeks’ lives and the reality they represent, it seems anything but.

President Obama's Hard Rhetorical Shift on Gun Control

In the days following the 2011 Tucson shooting, in which six people, including a federal judge and a 9-year-old girl, were killed and Representative Gabby Giffords was severely injured, President Obama flew to Arizona to address the attack.

“For the truth is none of us can know exactly what triggered this vicious attack,” the president said. “None of us can know with any certainty what might have stopped these shots from being fired, or what thoughts lurked in the inner recesses of a violent man’s mind.”

The speech, which took place four days after the shooting, is regarded as one of the best of his presidency for its palliative force. For its dearth of overly political claims, it also earned the president an on-air high-five from Charles Krauthammer and praise from Newt Gingrich and Senator John McCain.

On Thursday, the president addressed the shooting at Charleston’s Emanuel A.M.E. church just hours after the tragedy unfolded and moments after the suspect had been apprehended. Like the Tucson speech, there was “heartache” and there was “sadness.” But there was also “anger.”

“...once again, innocent people were killed in part because someone who wanted to inflict harm had no trouble getting their hands on a gun.”In displaying anger, President Obama deviated from a precedent set in over six years of delivering speeches about mass shootings and gun violence. This time, there was the same rhetorical splay of uncertainties, but with an entirely different conclusion:

We don’t have all the facts, but we do know that, once again, innocent people were killed in part because someone who wanted to inflict harm had no trouble getting their hands on a gun.

There are plenty of potential reasons for the shift. At the time of the Tucson speech, the president was 22 months shy of reelection and his approval ratings were among the lowest for a president entering his second year of office since Eisenhower. There’s also a shrewd political calculation in initially letting a horrible moment speak for itself. The circumstances of the Tucson shooting and the motives of its perpetrator, Jared Lee Loughner, differ from what we currently know of the suspect in the Charleston shooting. And between Tucson and Charleston came shootings in Aurora, Oak Creek, Isla Vista, and Newtown.

Both sets of the president’s remarks about the Aurora shooting, which took place in the summer of 2012, were particularly anodyne. Compare the president’s remarks as events in Charleston unfolded with this chestnut on the stump on the day of the shooting: “And if there’s anything to take away from this tragedy it’s the reminder that life is very fragile. Our time here is limited and it is precious.”

In the hours after the 2012 Newtown massacre, President Obama addressed the nation from a room in the White House named for James Brady, one of the four men shot during John Hinckley’s attempt on life on Ronald Reagan. The president’s speech was more memorable for the image of him wiping away tears than it was for any clarion calls for gun reform. Here’s the speech’s most assertive section:

As a country, we have been through this too many times. Whether it’s an elementary school in Newtown, or a shopping mall in Oregon, or a temple in Wisconsin, or a movie theater in Aurora, or a street corner in Chicago—these neighborhoods are our neighborhoods, and these children are our children. And we're going to have to come together and take meaningful action to prevent more tragedies like this, regardless of the politics.

As with the Isla Vista shooting, the president’s more pointed words came two days later at a memorial service in Newtown during which he said, with some exasperation, “We can’t accept events like this as routine.” He added, “Are we really prepared to say that we’re powerless in the face of such carnage, that the politics are too hard?”

The answer, as Wednesday night proved, turned out to be “yes.” And while some have pushed back against the idea that the gun proposals proffered by the White House and the Democrats would have prevented what happened in Charleston, killings like these have become appallingly routine. That might be what pushed the president to break with his own routine.

With Inside Out, Pixar Returns to Form

Welcome back, Pixar. You were sorely missed.

Over the course of 15 years and nearly a dozen films, the animation studio had put together one of the most remarkable runs of sustained excellence in cinematic history, culminating with the trifecta of Wall-E (2008), Up (2009), and Toy Story 3 (2010).

Related Story

But nothing lasts forever. A few members of the studio’s central brain trust branched out into live-action (Andrew Stanton with John Carter, Brad Bird with Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol and Tomorrowland), head honcho John Lasseter added Walt Disney Animation Studios to his list of responsibilities, and Pixar came down with an acute case of sequelitis. Brave (2012) was a solid addition to the canon, but it was sandwiched between Cars 2 and Monsters University—almost certainly the two worst movies the studio has produced. The subsequent year, 2014, was the first in a decade in which Pixar didn’t release any feature at all.

But right now, none of that matters. Because writer-director Pete Docter—the man responsible for arguably Pixar’s most underrated picture, Monsters Inc., and its best overall, Up—has now given us Inside Out. At once achingly heartfelt and magnificently high-concept, the film tells the story of a girl named Riley (Kaitlyn Dias) and the five emotions that together make up her psyche: Joy, Sadness, Fear, Disgust, and Anger.

Let’s begin with the glorious anthropomorphizing of said emotions. Joy (Amy Poehler) is a sunshine-yellow pixie of enthusiasm who presides over the “control room” of Riley’s mind as a benevolent dictator, trying to keep the less-upbeat of her colleagues off the controls. Sadness (Phyllis Smith, who played Phyllis on The Office) is blue and blobby, unsure of her role and seemingly destined to ruin everything she touches. Fear (Bill Hader) is a purply, perpetually jangled nerve-ending, and Disgust (Mindy Kaling) is a sickly green guru of sarcastic judgmentalism. Squat, blocky Anger is—as if you hadn’t already guessed—fire-engine red and voiced by Lewis Black.

As its title suggests, the true drama (and comedy) of the film takes place inside Riley’s head.When the story begins, Riley is an 11-year-old coasting through life with Joy firmly at the steering wheel. She has two loving parents (Diane Lane, Kyle MacLachlan) and a perfect Minnesota childhood made up of equal parts friendship and ice hockey. But calamity strikes, as it so often does, in the humblest of ways. Her dad gets a job at a tech startup and he moves the family out to that bleak nowheresville known as the Bay Area. (One of better inside jokes that the Emeryville-based Pixar works into the movie is the portrayal of San Francisco as a kind of miserable anti-utopia, gray and foreboding.)

Indignities accumulate one upon another: The moving van containing all of Riley’s furniture and belongings is delayed, and delayed again, leaving her huddled on the bare floor of her new bedroom in a sleeping bag. Her normally cheery dad is rendered distant and irritable by the demands of his new job. An introductory presentation to her new classmates dissolves into a wave of tears. Even hockey tryouts are a source of frustration. Before long, Riley becomes sullen and closed-off, snapping at her parents and hanging out alone in her room.

But as its title suggests, the true drama (and comedy) of the film takes place behind the scenes, inside Riley’s head. I won’t belabor the complex mechanics of the movie, but each memory Riley accumulates is like a glass ball, colored the hue of the emotion associated with it—overwhelmingly Joy-ish yellow at the start. Some of these balls become “core memories,” which sustain the “islands” that make up Riley’s essential personality: friendship, family, hockey, etc.

As things begin to go awry in Riley’s external life, so too, they fall apart on the inside. Sadness keeps touching happy memories and turning them blue. And when Joy tries to get the situation back to normal, she winds up inadvertently exiled to long-term memory with Sadness in tow. Much of the “action” of the plot involves their efforts to get back to the control room, traversing such terrain as Imagination Land, Abstract Thought, the Dream Production studio (featuring such classics as “I Can Fly” and “Something is Chasing Me”), and the Subconscious (which, we’re informed, is “where they take all the troublemakers”). There are innumerable clever gags along the way, including explanations of why TV jingles get stuck in our heads and how facts and opinions become jumbled together. Most important, Joy and Sadness meet Bing Bong, Riley’s long-forgotten imaginary friend, who is voiced wonderfully by Richard Kind and offers many of the film’s most wistful, Toy Story-like moments.

If this sounds like a lot of gloopy therapeutic uplift—well, it is, except for the gloopy part.The real journey, of course, is not from point A to point B, but toward an acceptance of the full breadth of our emotional lives. Joy learns not only that she can’t always be in charge, but that Sadness—initially dismissed with an “I’m not actually sure what she does”—has an important role to play as well. (Docter was inspired to make the film by the childhood experience of his family moving to Denmark and, more immediately, by a bout of insecurity that his daughter went through when she was 11.)

If this sounds like a lot of gloopy therapeutic uplift—well, it is, except for the gloopy part. Inside Out is a vibrant, witty film, full of dazzling visuals and, at a zippy 94 minutes, wise enough not to let its intricate workings overwhelm its storytelling. And while the lessons it offers may be straightforward, they’re eminently useful ones, for kids and parents alike. This is Pixar once again at the top of its game, telling the kind of thoughtful, moving meta-story it’s hard to imagine being produced anywhere else.

See it now. Savor the moment. And do your best to forget that Cars 3, Toy Story 4, The Incredibles 2, and Finding Dory are all rumbling down the pipeline behind it.

Why a Black Church?

Late on Wednesday night, nine people were murdered and one person was wounded while praying at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. Police have taken the suspected killer, 21-year-old Dylann Roof, into custody. The Justice Department has opened a hate-crime investigation into the shooting.

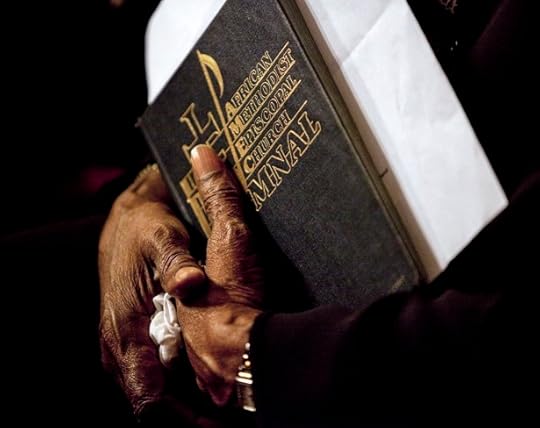

If these murders were racially motivated—and there’s ample reason to suspect they were—it’s significant that the shooter chose a church, and specifically this church, as a target of violence. “What African Americans see when they hear about this kind of violence being done in a black church ... [is] this whole pattern of violence dating back to the 18th century of attacks against their churches,” said Laurie Maffly-Kipp, a professor of religion and American history at the University of Washington in St. Louis. As my colleague Yoni Appelbaum wrote on Thursday, Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church is one of the oldest black churches in the South and has been an important part of the African American community in Charleston, particularly in the fight for civil rights. And as my colleague Conor Friedersdorf wrote, there’s a long history of violence against black churches in the U.S., particularly in the South.

To this day, churches are the center of social and political life in the American black community—and they are clear symbols of black influence and power. “To attack a black church in 2015 means that that young man, Dylann, understood that Emanuel A.M.E church was a focal point for not just the history of African Americans in the country ... but where they also mobilize,” said Anthea Butler, a professor of religious studies at the University of Pennsylvania.

Related Story

Thugs and Terrorists Have Attacked Black Churches for Generations

There’s a cliched saying about religion and race in United States, something along the lines of “Sunday morning is the most segregated hour in America.” Black and white Christians still overwhelmingly tend to worship in separate congregations, for many reasons. “A lot of it has to do with the history of separation which led to different kinds of worship,” said Maffly-Kipp. In the early American republic, a number of black churches existed independently of white churches, “but they were pretty much shut down after the 1820s. Church Emanuel in Charleston was burned to the ground [in 1822] and shut down because of fears about the kinds of activities that were going on in churches.”

After it burned, Emanuel A.M.E wasn’t able to formally rebuild until 1865; it was closed by the South Carolina government. In the years leading up to the Civil War, independent black churches were outlawed, and African Methodist Episcopal congregations became concentrated in the North. But after the war, these churches were among the first to proselytize, Maffly-Kipp said. “There were missionaries in the A.M.E. church going down into the Southern states trying to get to black Methodists there.”

As blacks struggled to reconstitute their communities in the decades following the Civil War, churches became the center of African American life—largely, Maffly-Kipp said, because they didn’t have any other spaces they could fully claim as their own. Churches built schools, helped families raise their kids, and fostered political activity, particularly during the civil-rights era. “It’s the one safe space they have for decades that is out of the surveillance of white communities. It has a sacredness just by virtue of being a separate space,” she said.

In 2015, the de facto segregation in American churches is more complex than it was 200 years ago. “You see in white churches ... hourlong service on Sunday mornings, and in black churches, you have a three-hour services. … The style of the service is completely different.” But it’s also not just a matter of worship preferences. “Dylann was able to come in on a Wednesday night bible service and nobody asked any questions about him because black churches have always been open, even though they have also been targets of violence,” said Butler. “In white churches, especially in white evangelical churches, there is an expectation that you will become white. … You cannot bring your culture into that door.”

In a video from 2013, Clementa Pinckney, Emanuel’s pastor and one of the people murdered in the attack, said, “The African American church—and in particular, in South Carolina—really has seen it as its responsibility and its ministry and its calling to be fully integrated.” This may not seem like the right moment to consider that challenge—in such a stark moment of racial hatred, the obvious and most important response is solidarity and mourning. But the fact of racial segregation in American churches made Emanuel A.M.E vulnerable in a way that’s not paralleled in any other sphere of life—the black church is “the one symbol white people know about black people in this country,” Butler said. White Christians did not wish murder upon their black brethren, but it’s also true that the status quo of divided church life in America made it much easier for Roof to find a room full of black men and women to gun down during prayer. That is a deeper cultural context of these attacks, but it’s much more difficult to integrate America’s churches than to condemn horrific violence. “They are saying this is an attack on Christianity. Bullshit,” said Butler. “This is an attack on black Christians.”

The True Face of Medicare Fraud

A specter is still haunting American politics—the mythological specter of the welfare queen. Even after Clinton-era welfare reforms, and despite an ever-growing list of state restrictions on how public benefits can be used, Americans remain convinced that there’s waste, fraud, and abuse in the system, and that stronger controls would keep undeserving citizens from bilking the taxpayer. There is fraud, it’s true. But it’s not nearly large enough to make a dent in the federal budget, and it’s not freeloading welfare queens who are taking advantage of the system.

Nearly lost Thursday in the response to the atrocity in Charleston was Attorney Loretta Lynch’s announcement of arrests in what she called “the largest criminal health care fraud takedown in the history of the Department of Justice.” A total of 243 people were arrested and charged with stealing $712 million from Medicare. The arrests included 46 doctors, nurses, pharmacy owners, and other medical professionals. Facilities billed the federal government for therapy sessions where patients were actually just moved, never treated. In a particularly disturbing case, a Michigan doctor allegedly “prescribed unnecessary narcotics in exchange for patients' identification information, which was used to generate false billings. Patients then became deeply addicted to the prescription narcotics and were bound to the scheme as long as they wanted to keep their access to the drugs.”

A doctor in Los Angeles is accused of being responsible for $23 million in losses alone, after he prescribed 1,000 power wheelchairs that were not medically necessary and in some cases weren’t even delivered to patients. People in three Texas cities were arrested for allegedly coaching patients so that they could get doctors to prescribe unneeded drugs.

Medicare’s prescription-drug program is a common target for fraud, it turns out. A 2013 investigation by ProPublica and NPR focused on the program. Reporters looked into the case of Ernest Bagner, a psychiatrist in whose name millions of dollars of drugs were prescribed. Bagner claimed his identity had been stolen and used to acquire the drugs, and while authorities weren’t convinced that his story was true, Medicare also never restricted his ability to prescribe drugs through the program.

Related Story

Just How Wrong Is Conventional Wisdom About Government Fraud?

While Thursday’s bust may be exceptionally large in scale, it isn’t unusual in type. Looking back through government news-release archives shows similar announcements: $260 million in false billing, including 27 doctors, nurses, and medical professionals, here; $223 million in false billing, again involving doctors, nurses, and medical professionals, there.

Are these numbers huge or tiny? Maybe both. It’s hundreds of millions of dollars, but it’s also only a fraction of the total estimated fraud, which runs into the tens of billions of dollars. It’s probably around 10 percent of the annual Medicare budget, which is more than $500 billion. And that’s still a tiny fraction of the overall federal budget.

A couple years ago, Slate’s Josh Levin investigated the origins of the welfare-queen myth, tracing it to a real figure, Linda Taylor. What Levin found was that Taylor’s story was far weirder than simply bilking the system—that might have been the least of her crimes. Despite being a singularly bizarre figure, the idea that there are hundreds of Linda Taylors out there making money off the safety net is a powerful political force. And that makes fraudulent schemes like the ones Lynch alleged today all the more pernicious. Not only are doctors who rip the system off stealing from taxpayers, they’re reshaping public opinion in ways that harm the people who truly need health care.

June 18, 2015

Take Down the Confederate Flag—Now

Last night, Dylann Roof walked into a Charleston church, sat for an hour, and then killed nine people. Roof’s crime cannot be divorced from the ideology of white supremacy which long animated his state nor from its potent symbol—the Confederate flag. Visitors to Charleston have long been treated to South Carolina’s attempt to clean its history and depict its secession as something other than a war to guarantee the enslavement of the majority of its residents. This notion is belied by any serious interrogation of the Civil War and the primary documents of its instigators. Yet the Confederate battle flag—the flag of Dylann Roof—still flies on the Capitol grounds in Columbia.

The Confederate flag’s defenders often claim it represents “heritage not hate.” I agree—the heritage of White Supremacy was not so much birthed by hate as by the impulse toward plunder. Dylann Roof plundered nine different bodies last night, plundered nine different families of an original member, plundered nine different communities of a singular member. An entire people are poorer for his action. The flag that Roof embraced, which many South Carolinians embrace, does not stand in opposition to this act—it endorses it. That the Confederate flag is the symbol of of white supremacists is evidenced by the very words of those who birthed it:

Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth...

This moral truth—“that the negro is not equal to the white man”—is exactly what animated Dylann Roof. More than any individual actor, in recent history, Roof honored his flag in exactly the manner it always demanded—with human sacrifice.

Surely the flag’s defenders will proffer other, muddier, interpretations which allow them the luxury of looking away. In this way they honor their ancestors. Cowardice, too, is heritage. When white supremacist John Wilkes Booth assassinated Abraham Lincoln 150 years ago, Booth’s fellow travelers did all they could to disassociate themselves. “Our disgust for the dastardly wretch can scarcely be uttered,” fumed a former governor of South Carolina, the state where secession began. Robert E. Lee’s armies took special care to enslave free blacks during their Northern campaign. But Lee claimed the assassination of the Great Emancipator was “deplorable.” Jefferson Davis believed that “it could not be regarded otherwise than as a great misfortune to the South,” and angrily denied rumors that he had greeted the news with exultation.

Villain though he was, Booth was a man who understood the logical conclusion of Confederate rhetoric:

"TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN":

Right or wrong. God judge me, not man. For be my motive good or bad, of one thing I am sure, the lasting condemnation of the North.

I love peace more than life. Have loved the Union beyond expression. For four years have I waited, hoped and prayed for the dark clouds to break, and for a restoration of our former sunshine. To wait longer would be a crime. All hope for peace is dead. My prayers have proved as idle as my hopes. God's will be done. I go to see and share the bitter end….

I have ever held the South were right. The very nomination of ABRAHAM LINCOLN, four years ago, spoke plainly, war—war upon Southern rights and institutions….

This country was formed for the white, not for the black man. And looking upon African Slavery from the same stand-point held by the noble framers of our constitution. I for one, have ever considered if one of the greatest blessings (both for themselves and us,) that God has ever bestowed upon a favored nation. Witness heretofore our wealth and power; witness their elevation and enlightenment above their race elsewhere. I have lived among it most of my life, and have seen less harsh treatment from master to man than I have beheld in the North from father to son. Yet, Heaven knows, no one would be willing to do more for the negro race than I, could I but see a way to still better their condition.

By 1865, the Civil War had morphed into a war against slavery—the “cornerstone” of Confederate society. Booth absorbed his lesson too well. He did not violate some implicit rule of Confederate chivalry or politesse. He accurately interpreted the cause of Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee, men who were too weak to truthfully address that cause’s natural end.

Moral cowardice requires choice and action. It demands that its adherents repeatedly look away, that they favor the fanciful over the plain, myth over history, the dream over the real. Here is another choice.

Take down the flag. Take it down now.

Put it in a museum. Inscribe beneath it the years 1861-2015. Move forward. Abandon this charlatanism. Drive out this cult of death and chains. Save your lovely souls. Move forward. Do it now.

How Much Has Changed Since the Birmingham Church Bombing?

"The climate of racial division across the country is extreme."

So said Deval Patrick, then-U.S. assistant attorney general for civil rights. The year was 1996, and citizens and law-enforcement officials were struggling to reckon with a wave of arson across the south, mostly (though not exclusively) targeting black churches.

Those crimes connect to a long history of terrorist attacks against black houses of worship—a history as long as the United States, encompassing early post-colonial America, running through the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, and continuing up to Wednesday’s shooting at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. As the Baltimore Sun reported in 1996, “Since the end of the Civil War, when freed slaves began to erect their own churches, racist whites have attacked those houses of worship to stir fear in black leaders and to quash efforts by blacks to improve their lives.”

Related Story

The Fight for Equality in Charleston, From Denmark Vesey to Clementa Pinckney

Today, as in 1996, as in 1963, it seems that the climate of racial division in the United States is extreme. The attacks are a reminder that white violence against black people remains a powerful presence in America.

“The fact that this took place in a black church obviously also raises questions about a dark part of our history,” President Obama said during a brief statement Thursday afternoon. “This is not the first time that black churches have been attacked.”

But there are some hopeful signs in the ways the nation responds to such crimes. The immediate national reaction of sorrow and outrage, bringing with it a near-unanimous labeling of the attack as a racist hate crime, stands out from past incidents. So too does the united response across the political spectrum. Unlike in past incidents, local, state, and federal law-enforcement officials are already working carefully in concert, including the arrest of suspect Dylann Roof over the border in Shelby, North Carolina.

Almost as soon as the news of the Charleston shooting broke, people began reaching back to the example of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing on September 15, 1963. That attack killed four young girls and galvanized the nation, but that reaction was in many ways atypical. By the time four Ku Klux Klan members planted dynamite at the church, the Alabama city had long since been nicknamed “Bombingham.” Between 1947 and 1965, white supremacists planted more than 50 devices targeting black churches, black leaders, Jews, and Catholics. It was the size of the explosion and the massacre of young children that seemed to make it different. Even Governor George Wallace, one of the nation’s most outspoken and virulent segregationists, offered a $5,000 reward for the arrest of the bombers.

But many leaders rejected Wallace’s overture as calculated and false. “The blood of four little children ... is on your hands,” Martin Luther King angrily wired the governor. “Your irresponsible and misguided actions have created in Birmingham and Alabama the atmosphere that has induced continued violence and now murder.” The bombing was the climax of a tense period that began when a federal court ordered the integration of local schools. Wallace, backed by local authorities, refused to follow the order and said the state needed a few "first-class funerals"—a statement widely interpreted as encouraging the attack.

After the bombing, more violence struck the streets of Birmingham, as riots and battles between blacks and whites broke out. Two black children were shot, one by police and one by a white teen.

President John F. Kennedy spoke the day after the bombing, calling for racial justice and peace, and the attacks helped catalyze the passage of the Civil Rights Act that Kennedy would not live to see enacted. As Andrew Cohen recalled in 2013, there were some courageous reactions to the bombing. A young white lawyer named Charles Morgan Jr. laid out responsibility for the attack clearly on September 16:

All across Alabama, an angry, guilty people cry out their mocking shouts of indignity and say they wonder, "Why?" "Who?" Everyone then "deplores" the "dastardly" act. But you know the "who" of "Who did it" is really rather simple. The "who" is every little individual who talks about the "niggers" and spreads the seeds of his hate to his neighbor and his son. The jokester, the crude oaf whose racial jokes rock the party with laughter. The "who" is every governor who ever shouted for lawlessness and became a law violator. It is every senator and every representative who in the halls of Congress stands and with mock humility tells the world that things back home aren't really like they are. It is courts that move ever so slowly, and newspapers that timorously defend the law.

And yet no perpetrator was tried or jailed for the church bombing until 1977—the delay in justice the result of, at best, a fractured relationship between the authorities charged with investigating the crime and, at worst, a conspiracy by officials—including FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover—to prevent a meaningful prosecution. Almost immediately, investigators focused in on four Klan members as perpetrators. Two were convicted of illegally possessing dynamite, fined, and given 180-day suspended sentences.

While the FBI named them as suspects, the case closed without prosecution in 1965, reportedly because of mistrust between local and federal authorities. It later emerged that some essential evidence gathered by the FBI had been ordered sealed by Hoover himself, the longtime lawman under whose direction the bureau once attempted to coerce King into suicide. In 1977, newly elected Alabama Attorney General Bill Baxley convicted Robert Chambliss of the attack; Baxley had to threaten the FBI with revealing its obstruction in order to get evidence. The last of the four suspects was not convicted until 2002.

The ground had changed for the better, somewhat, 30 years later, when black churches across the south began going up in flames. President Clinton traveled to Greeleyville, South Carolina, the site of one arson, to speak out and promise justice. But despite the apparent political will, justice was again slow coming. The Sun noted that even though 27 churches burned in the first half of 1996 alone, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms had made arrests in only five cases since January 1995.

Law-enforcement agents professed confusion. “The pattern to these crimes is that there is no pattern,” said Robert Stewart, chief of the South Carolina State Law Enforcement Division. "There are a few cases where we can say definitively that race is the motive. But in most cases, it's not so clear-cut." The Sun reported:

As law enforcement officials across the South struggle for answers to explain why more than 60 black churches have been burned in the last year and a half, they find themselves taking into custody aimless teen-agers like [17-year-old suspect Robert Glenn] Emerson, who are looking for kicks. Nationally, very few arrests have been made of people who are members of white supremacy groups, making it harder for police to predict where and when the arson attacks will occur.

Clinton launched a special task force on church arson and signed a new law granting prosecutors special leeway in dealing with burning and desecration of houses of worship; many arrests and convictions were eventually obtained. Among those convicted were members of the Ku Klux Klan.

Yet even then, there were some crucial differences. Several of the churches that burned were in North Carolina, which was at the time represented in the Senate by Jesse Helms, perhaps the last unrepentant racist to achieve a long and prominent career in national politics. Six years earlier, during his 1990 reelection campaign against a black Democrat, Helms had shamelessly appealed to white fears of black advancement in a TV ad—which was credited with vaulting him back into the lead and winning the race. In 1996, even as he spoke of Jim Crow laws and enduring black poverty in the South, Clinton implausibly tried to argue that the burnings were somehow not a political question: “We must keep this out of politics.” (Jesse Jackson, speaking at the same event, was not similarly fooled, and discussed “anti-black mania.”) Even so, Clinton was pilloried by the GOP:

The President's visit nonetheless brought criticism from some Republicans, who said he was using the misfortune of dozens of black congregations to serve political purposes. David Beasley, the Republican Governor of South Carolina, called the appearance "a political event," and said, "I only hope that the President is sincere." At a Washington news conference, Haley Barbour, the Republican national chairman, said the visit had been motivated by "transparent, shameless politics."

(It was Haley Barbour who, in 2010, would solemnly insist that 1960s white-supremacist Citizens Councils were a force for racial justice.)

That sort of backlash has been mercifully absent so far in the aftermath of the Emanuel shooting. Democratic Mayor Joe Riley and Republican Governor Nikki Haley stood side-by-side at a Thursday morning news conference in Charleston. Republican State Senator Larry Grooms choked up talking about Clementa Pinckney, the pastor of Emanuel Church, one of Wednesday’s victims, and a Democratic state senator.

There’s no doubting that this attack was about race. A survivor reportedly said that suspect Dylann Roof said, “I have to do it. You rape our women and you’re taking over our country. And you have to go.” A picture on Facebook showed him wearing patches with the flags of apartheid South Africa and of Rhodesia, the white supremacist precursor of Zimbabwe. Unlike in 1963 or 1996, all information to this point suggests that Roof was acting on his own, rather than a member of the Ku Klux Klan, yet another case in which traditional institutions of violence seem to be weakening and giving way to “lone-wolf” terror attacks.

“Everyone then ‘deplores’ the ‘dastardly’ act. But you know the ‘who’ of ‘Who did it’ is really rather simple.”But South Carolina’s relationship with race remains difficult, just as it was 20 years ago. Although officials hastened to describe Wednesday’s shooting a hate crime, the state is one of few without a hate-crimes statute of its own on the books. In Columbia, the state capital, the Confederate battle flag flies over a memorial near the state house. It was moved there in 2000, having previously flown atop the building. It was first placed there in 1962—intended, some say, as a way to commemorate the Civil War centennial, though it’s impossible to overlook the coincidence of hoisting the flag in the midst of the civil-rights movement. Elsewhere on the grounds are statues of two South Carolina senators, of onetime Dixiecrat presidential candidate Strom Thurmond and “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman, a virulent white supremacist who spoke out in favor of lynch mobs. And Walter Scott, an unarmed black man, was shot in the back by a white policeman in April in North Charleston, less than 11 miles away from Emanuel Church.

It’s possible in this history to find hopeful signs that the United States is getting better at coming to grips with white-supremacist violence. Yet that progress stands alongside a history of attacks on black places of worship as old as the Constitution.

How Obama Might Get His Trade Deal After All

Shortly before the House voted on Thursday—for the second time in a week—to deliver President Obama the authority he was seeking to negotiate trade agreements abroad, Speaker John Boehner was asked if he had learned anything from the dead-one-moment, alive-the-next legislative battle.

Nope, the speaker replied. “I would describe most of what’s gone on the last three weeks as close to bizarre,” he told reporters. “I don’t think I’ve learned anything from it.”

Related Story

Boehner was certainly correct in the initial part of his reply. Just six days ago, House Democrats overwhelmingly repudiated Obama’s trade agenda by defeating the one part of that package—Trade Adjustment Assistance—that was included to garner their support. Led by Republicans, the House then approved the core piece, “fast-track” Trade Promotion Authority, but because Democrats rejected the aid for displaced workers, the underlying legislation remained stalled. Nancy Pelosi, the president’s loyal partner for six-and-a-half-years, betrayed him on the House floor, and Obama’s top domestic priority was left for dead—or so everyone thought.

The Democratic revolt was surprising enough, but what’s happened since has been equally unusual. Spurned by his friends, Obama responded to the setback not by trying to win them over, but by conspiring with Republicans against them. (Yes, the same Republicans who are simultaneously suing him for abuse of power.) With backing from the administration, the House jettisoned the worker assistance from the trade package and on Thursday, approved Trade Promotion Authority on its own. The vote, 218-208, was nearly identical to the one last week, but now the new bill must go back to the Senate before Obama can sign it.

“I would describe most of what’s gone on the last three weeks as close to bizarre.”To keep pro-trade Democrats on board, the White House and Republican leaders promised them that they would pass Trade Adjustment Assistance, or TAA, separately if they can. How do they hope to do that? By attaching that measure to an even more popular bill—which passed the House and Senate nearly unanimously—that maintains trading preferences for African nations.

In other words, we’ve reached the peak sausage-making phase of the trade fight. It’s oddly reminiscent of the biggest legislative lift of Obama’s first term: healthcare reform. After Scott Brown’s surprise Senate victory in Massachusetts cost Democrats their filibuster-proof majority, then-Speaker Pelosi considered all sorts of legislative machinations—remember “deem and pass”?—to get Obama’s landmark bill to his desk. When she finally turned to the obscure budget maneuver known as reconciliation to finish the job, Republicans cried foul.

This time, the protesters were Democrats. Rosa DeLauro, the Connecticut liberal who has led the fight against trade in the House, denounced the move as “a gimmick,” and she noted ruefully that Obama had ignored his party’s plea for changes to the bill. “The administration,” DeLauro said, “has shown absolutely no interest in improving this deal or even listening to our concerns.” Union leaders complained about “parliamentary trickery” just days after they used similar legislative tactics to defeat the trade bill initially. Pelosi, meanwhile, criticized the legislation but held her tongue on the process. “God knows,” she said, “I know the power of the speaker.”

Obama’s trade agenda may be revived, but it is not yet enacted. The Senate next week must vote again on both TPA and TAA, and the strange Obama-GOP alliance will have to hold on to the same dozen or so Democratic senators that supported the trade bills last month. Once Trade Promotion Authority passes the Senate again and goes to the Oval Office, the House would vote again on Trade Adjustment Assistance, with the assumption that Democrats will have no reason to oppose it if doing so won’t stop fast-track trade authority from becoming law.

It’s confusing, and, yes, bizarre. But contrary to Boehner’s take on the whole ordeal, there might be something to learn after all. Republicans have complained, to the president, the public, and the courts, that when they don’t give Obama what he wants, he simply goes around them. The last week has demonstrated that he’s perfectly happy to go around Democrats, too.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower