Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 412

June 16, 2015

Colorado: Smoking Weed, Even Legally, Is Fair Grounds for Firing

On Monday, Colorado’s Supreme Court found it legal for a company to fire an employee who has legally smoked marijuana. The court decided against Brandon Coats, a former Dish Network employee who was fired in 2010 after testing positive for marijuana, which his doctors prescribed him to treat the muscle spasms and seizures he still experienced several years after being paralyzed in a car crash. Even though Dish Network conceded that Coats wasn’t smoking on the job, it stood by its zero-tolerance policy. While Coats’s case dealt with medical marijuana, the ruling affects nonmedical marijuana use as well—any marijuana use, even off-duty, is grounds for firing in Colorado.

However, the Coats ruling shouldn’t be interpreted as a sign that employers in every state will be able to fire employees who smoke marijuana under the protection of state laws. Colorado has its own particular set of labor laws and marijuana laws that resulted in the court’s finding. Other states, with other combinations of labor and marijuana laws, might see different outcomes.

Colorado, for example, has a law stating that employees can’t be fired for engaging in any “lawful” activity, and the question was whether ingesting marijuana (even for medical reasons) was “lawful,” given that Colorado state law permits it and federal law doesn’t. The court decided that federal law took precedence, which means that Dish Network was within its rights when it fired Coats for his positive drug test. “The Coats case can be seen as a win for employers because the decision continues the trend of courts concluding that an employer can terminate an employee for testing positive,” says Barbara Johnson, an employment lawyer at the law firm Paul Hastings.

Related Story

The Pointlessness of the Workplace Drug Test

But litigants like Coats might see different rulings in other states. “This is really going to come down to states and how states handle these types of employment issues,” says Mason Tvert, the director of communications at the Marijuana Policy Project. "Different states have different laws on the books regarding employment, just like we have some states that are right-to-work states and others that aren't." Tvert notes that Arizona, Delaware, and Minnesota have laws that explicitly protect medical-marijuana patients from being fired after failing a drug test. Others, such as New York and Rhode Island, have similar protection, but don’t refer to drug testing. Still others have no employment protections related to marijuana use.

Colorado may have resolved the question for the time being, but it’s not clear how state and federal laws interact in other places, and the uncertainty leaves patients confused about whether their jobs are safe. Back in 2010, for Coats, this produced a situation in which the results of a drug test would never be a surprise—but his employer’s reaction to the results would be. (Even though no federal law requires that employers give drug tests to their employees, about 40 percent of employers nationwide still do.)

Even if employers aren’t embracing marijuana use, American society appears to be. Nearly half of Americans report having tried it, and four states and the District of Columbia have legalized its recreational use. "We expect the laws to catch up with the culture, and increasingly, employers are not going to want to fire employees for using marijuana off the job and then go through the process of hiring and training.…They will treat marijuana similarly to how they treat alcohol," says Tvert. Coats himself noted the existence of a double standard. He told The New York Times last year: “A person can drink all night long, be totally hungover the next day and go to work and there’s no problem with it.”

The First Hispanic President?

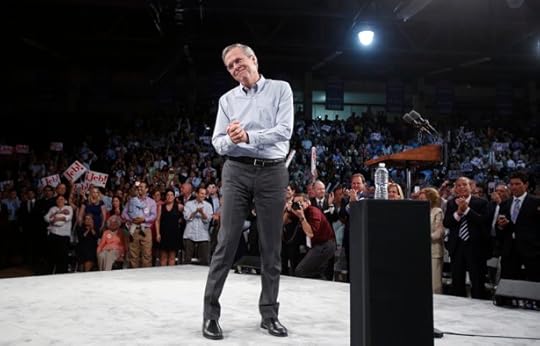

Hillary Clinton’s announcement emulated the style of the presidency itself: vast, formal, the spotlight narrowly focused on one person. Jeb Bush’s announcement was that of a humble office-seeker facing a tough race: a rally in a compact space, lots of cheering and amateurish music, introductions of introductions, culminating in the candidate in open shirt jogging his way onto the stage. Message: I’m fit! Message: I’m accessible! Message: I’m unentitled!

Unlike Hillary Clinton, Jeb Bush offered little in the way of an agenda. He reviewed highlights of his record as governor of Florida, diagnosed some general ills in the country, and offered a generic aspirational goal: 4 percent economic growth and 19 million new jobs.

The sharpest contrast he drew was in his long discussion of family. He referenced his presidential father and brother (but not by name), saluted his highly popular mother, and lavished praise on his wife, children, and grandchildren. “See, a loving, united family! Not like that other weird presidential family that will go unmentioned here today.”

But all of this was bunting. The central message of the announcement was that the GOP also has a history-making first to offer: after the first black president, as an alternative to the first female president, here is your chance at the first Hispanic president. Okay, maybe not literally and personally Hispanic, but close enough! The pre-rally music was all Spanish. The setting was Miami Dade College, which graduates more Hispanics than any other in the United States. Bush was introduced by the chair of the college’s board of trustees, a bilingual journalist, Helen Aguirre Ferre, and by his bicultural son, George P. Bush. Bush himself delivered some of his remarks in his fluent Spanish, for the benefit of “the many who can express their love of country in a different language.” In response to hecklers, he spontaneously reasserted his commitment to comprehensive immigration reform.

It’s a winning message for South Florida. How will it play elsewhere?

The most ingenious thing about the Bush speech is the way it played jujitsu with issues of entitlement and inheritance. The most quoted line in the speech will likely be this one: “Not a one of us deserves the job by right of resume, party, seniority, family, or family narrative. It’s nobody’s turn. It’s everybody’s test, and it’s wide open—exactly as a contest for president should be.” A few paragraphs up, however, Bush presented his family background in a much more audacious way. “In this country of ours, the most improbable things can happen. Take that from a guy who met his first president on the day he was born, and his second on the day he was brought home from the hospital.” Yes, incredible as it may seem, a person can run for president despite overcoming the handicap of being the son of one and the brother of another! Truly, this is a country where anything can happen—except, of course, a wage increase for middle-income workers. There, you’re moving from the realm of the improbable to the fantastical.

Same-old-Republicanism minus 47-percent insults is an improvement over same-old-Republicanism with insults.Jeb Bush acknowledged that latter trouble when he promised “growth that lifts up the middle class—all the families who haven’t gotten a raise in 15 years.” That last is an interesting number. 15 years takes us back to … 2000. All the way to the beginning of his brother’s presidency. The obvious question is: if your brother’s policies failed to deliver middle-class income growth, what are the different policies you’d offer in their place? That question went unanswered. In fact, you could write a pretty arresting presidential announcement based on the questions unanswered and the topics omitted from Jeb Bush's. “Healthcare” and “health”? Nowhere to be found. The environment? One reference—to over-regulation by the EPA. Retirement security for the baby boomers? Not there. Against the coming Clinton policy barrage, Bush will offer emotions, images, and bilingualism. If the Clinton campaign hopes to build a coalition of the disaffected and the alienated with a series of specific benefits and payouts, Bush seems to be seeking to revive his brother’s 2004 coalition with broad themes, unspecific commitments, and the promise of a compassionate heart.

After Mitt Romney’s loss in 2012, the Republican National Committee convened a post-mortem into the causes of the defeat. The project was co-chaired by Sally Bradshaw, whose day job is serving as Jeb Bush’s top political adviser. The report rejected any substantial policy changes and called instead for better technology, a softer tone, and developing an immigration message to appeal to Hispanics. That theory of the defeat will be theory of the Jeb Bush presidential campaign. At the core, however, not much has changed intellectually in the GOP since 2012, or really for that matter, since 1984: no more tangible help for the medical class, no acceptance of the principle of universal health coverage, no acknowledgement that most Americans are struggling with the same economic problems they struggled with long before the election of Barack Obama, no reckoning with climate change. Most arrestingly of all, in a speech that does touch again and again on America’s deteriorating position in the world, no mention of the most fundamental shift: China’s economic rise and the relative decline in U.S. power that has followed.

Same-old-Republicanism minus 47-percent insults is an improvement over same-old-Republicanism with insults. But same-old-Republicanism was losing even before Mitt Romney’s 47 percent gaffe, for reasons that could have been explained back in 2012—and that all too probably will be detailed by the post-mortem after the election of 2016.

Trans Fats to Be Illegal

For years, granola bars were like balsa wood. They could be instruments of blunt force trauma. I’m not certain, but I believe several people were killed when they tripped and were impaled by granola bars. So in the 1990s, Quaker’s line of Chewy bars were a giant leap for granola-bar kind, landing them within the domain of, as Quaker put it, the chewy foods. That was possible in part because of trans fats: the purposeful placement of a hydrogen molecule on a fatty acid in such a way that created a modification of the standard cis unsaturated fat structure. Partially hydrogenated oils were at once soft and malleable while resisting spoilage. It was a triumph of science that made a shelf-ready product out of something as unimaginable as frosting, and made the buttery compound “I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter” a source of so much indignation.

And, a boon for food producers, trans fats never had to undergo approval by the Food and Drug Administration. They were a synthetic version of something that already existed in some foods, like red meat, in very small amounts, so why should they be bad? As in all things we put in and on our bodies, though, quantity is everything. After several decades of mounting evidence against the safety of consuming trans fats at levels above the trivial, today the FDA claimed a grandiose but ultimately late-game victory, acting on a 2013 proposal requiring that trans fats be removed from its long list of compounds that are “generally recognized as safe.” Synthetic trans fats must be phased out of all foods within three years.

Few consumers will notice much change, though, as trans fats have already been voluntarily removed from many foods, including Quaker Chewy granola bars. In 2006, the FDA enacted a requirement that trans fat content be labeled on packages in response to a petition by the nonprofit advocacy organization Center for Science in the Public Interest, which had performed studies showing an increase in LDL cholesterol associated with the intake of trans fats. Years of consumer awareness and demand for trans-fat-free products, legitimized by local bans in New York City and elsewhere, led to widespread phasing out of trans fats and decrease in nationwide consumption by 85 percent over the past decade. Even the new iteration of I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter contains no trans fats (or, purportedly, butter).

Today FDA acting commissioner Stephen Ostroff said the move “is expected to reduce coronary heart disease and prevent thousands of fatal heart attacks every year.” It’s extremely difficult to isolate the role of a single nutrient in a fatal heart attack, and this estimation may be optimistic given the currently modest national consumption of trans fats. In the late 1990s, at peak trans fat intake, Walter Willett at the Harvard School of Public Health calculated the effect to be at least 30,000 premature deaths annually. CDC director Thomas Frieden later endorsed an estimate of 50,000. But if Ostroff is right, and there is still much public-health ground to be won through this ban, fine. There is no coherent health argument for a high-trans-fat diet. If you like food that’s chewy and juicy and cheap and not spoiled, there are new synthetic ingredients introduced all the time to accomplish these ends. A few may prove harmful to our health eventually, and we’ll figure that out and introduce a ban over the course of decades, at first in practice, with dollars and stomachs, and then, once industry lobbying is minimal enough to be overcome, federal agencies will take credit for protecting consumer well-being, and that’s the way things tend to work.

Pop's Septuagenarian King

Giorgio Moroder’s first solo album since 1985 represents either a tale of overcoming odds and reclaiming success late in life, or of record-company cynicism and the stagnant state of much of pop music. Let’s check out the heartwarming option first.

Related Story

Moroder, a 75-year-old Italian producer, is one of the most influential disco and electronica musicians of all time, having set the template for years of songs to come with his ‘70s work with Donna Summer. Any popular track featuring four-on-the-floor bass thump, synthesizer arpeggios on loop, and a general sense of whooshing and acceleration and robots grooving owes something to him. He kept finding success through the mid-‘80s, helping mint hits for the likes of David Bowie, Blondie, Freddie Mercury, and the Top Gun soundtrack. Then he mostly disappeared from public consciousness, until Daft Punk’s 2013 album Random Access Memories featured a track called “Giorgio by Moroder,” on which he could be heard talking about wanting to create “a sound of the future.” He’s said that song helped restart his career, and now he’s back with Déjà vu, featuring collaborations with Britney Spears, Kylie Minogue, Sia, Charlie XCX, Kelis, and other Top 40 staples.

You might expect this to be a throwback affair, one that highlights the lineage of some of today’s newest stars. Instead, it sounds like it could be the latest That’s What I Call Music Now! compilation (yes, those still exist) except for the fact that most of these songs aren’t yet popular. That the album’s on-trend, to some extent, shouldn’t surprise: Pop’s currently obsessed with dance music that has Moroder’s sonic DNA, both in the form of the sleek drama of EDM and the warm, springy disco repopularized by Pharrell.

But Moroder’s new music doesn’t just harken back to the styles that everyone else is hearkening back to—it sounds like the 2015 versions of them, like it’s been recorded with the same presets that Max Martin uses, made in the same studio as “Blurred Lines,” mixed by Calvin Harris to slot into a Las Vegas nightclub set. Accordingly, the Kylie Minogue-featuring single “Right Here, Right Now” shot to the top of the Billboard dance chart. It wouldn’t be surprising if the “Call Me Maybe”-esque title track featuring Sia, or the speak-and-spell workout “Diamonds” with Charlie XCX, or the Maroon 5 imitation “Tempted” with Matthew Koma, end up having similarly strong showings. (Meanwhile, the Britney Spears cover of “Tom’s Diner," with gloriously overdrawn production from Moroder, represents a perfectly modern act of trolling.)

The uncanny relevance of these songs is enough to make even the most poptimistic listener a little alarmed—has mainstream music really evolved so little that the reigning champ of 1975 can reclaim his spot with such ease? Well, maybe. But there are current tropes—tension building in the verses with mathematic predictability, zillion-hook choruses, the existence of Mikky Ekko—that would have taken a certain amount of studying-up to replicate. It’s tempting to suspect that folks hired by RCA, the label that coaxed Moroder into recording the album and helped line up singers and writers, focus-grouped and fidgeted with each measure for maximum impact.

But it seems more likely that Moroder himself figured out how to play the 2015 game. Name checks from Internet-age boundary-pushers like Daft Punk and James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem have built him up as an indie touchstone, but Moroder’s always been interested in chart domination. Kraftewerk and their contemporaries helped make electronica into art; Moroder made it into product. “The way I know if something works is if it sells,” Moroder told Spin in 2013, going on to talk about how in his heyday he knew which particular BPMs and bass sounds would get people to dance in New York. In a 2015 interview with the same publication, he talked about keeping knowledgeable about current recording techniques. “It’s quite complicated right now,” he said. “Certain sounds, especially the drums, they get old after six months.”

The interest in staying 100 percent relevant like this is rare for a senior citizen in popular music, to say nothing of the ability to pull it off. In art forms like literature and film, elder icons regularly keep producing major works late in life, but in pop—youth worshipping, novelty-obsessed, self-consciously disposable pop—former hitmakers are often consigned to nostalgia-act status. Or they become venerated credibility-keepers, like when Johnny Cash turned younger artists’ songs into solemn reflections on mortality. But as is perhaps fitting for someone who helped artificial sounds go mainstream, Moroder might chuckle at traditional ideas of how aging works. The most distinctive thing here is called “74 Is the New 24,” which surfs on waves of darkly thrumming Tron sounds that almost recall industrial music. The song seems to signal doom, not for the septuagenarian behind the vocoder, but for all those who’ve tried to take his place.

The Limits of Jeb Bush's Compassionate Conservatism

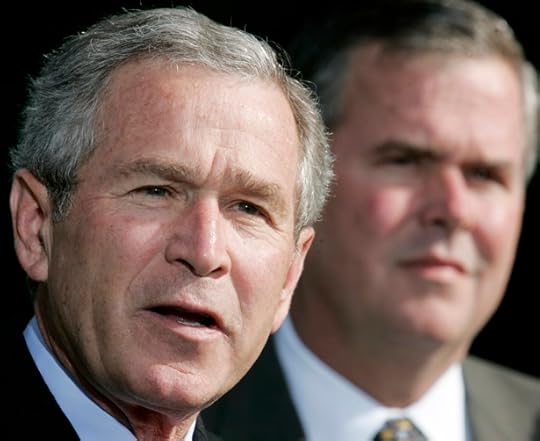

If Jeb Bush wants to prove that he’s different from his brother, he has an odd way of showing it. In the video that accompanied Monday’s announcement that he’s running for president, Jeb declared that, “The barriers right now on people rising up is the great challenge of our time” and that “my core beliefs start with the premise that the most vulnerable in our society should be in the front of the line and not the back.” Sound familiar? It should. It mimics George W. Bush’s presidential announcement, right down to the mangled prepositions. “I’ll tell you what’s on my heart,” George W. declared on June 12, 1999. “The purpose of prosperity is to leave no one out, to leave no one behind. I’m running because my party must match a conservative mind with a compassionate heart.” Sixteen years later, almost to the day, compassionate conservatism is back.

Let’s hope that this time, the press isn’t fooled.

In 1999, compassionate conservatism was George W.’s way of saying “I’m not Newt Gingrich.” Three years earlier, Bill Clinton had won reelection by lashing Republican nominee Bob Dole to the Gingrich Congress, which Clinton accused of seeking deep cuts to spending on Medicare, Medicaid, education, and the environment. Rhetorically, Bush offered a dramatic contrast, and a Republican talking about poverty intrigued the press. There were endless stories about Bush’s efforts in Texas at education reform and the rehabilitation of prisoners. Commentators pored over the writings of Bush advisors like Marvin Olasky, Myron Magnet and Stephen Goldsmith, who promised to fight poverty by outsourcing government services to businesses (which were supposedly more efficient) and religious groups (who supposedly cared more).

In his stated concern for the poor, George W. Bush was almost certainly sincere. “If he’s trying to allege that I’m a hardhearted person and I don’t care about children, he’s absolutely wrong," Bush fumed after Al Gore criticized his healthcare policies in Texas. But Bush’s heart was irrelevant; his policies were typical GOP fare. As governor, he had passed the largest tax cut in Texas history. And on his watch, Texas had been one of only three states that failed to make it easier for poor children to receive Medicaid, with the result that while Medicaid enrollment increased nationwide between 1997 and 1999, it dropped in Texas by more than seven percent. When Bush left the governor’s office, Texas had the seventh-highest poverty rate in the country and the highest percentage of children without health insurance.

Bush didn’t create these realities by himself, of course: Texas had been a low-tax, low-service, high-poverty state long before he entered office. But as governor, he had presided over an economic boom, the fruits of which he largely funneled to upper-income taxpayers rather than to the poor. “If there was ever an opportunity to invest, our current booming economy provides that opportunity,” Patrick Bresette, the associate director of the non-partisan, Texas-based Center for Public Policy Priorities, told the Los Angeles Times in 2000. “The governor has not stepped up a lot to say, ‘We’ve got more revenue coming in than we’ve seen in a decade. How can we spend it to help the least among us move up?’”

Related Story

Can Jeb Bush Make Republicans Believe?

When George W. became president, it was more of the same. Once again, the media lavished attention on the new Office of Faith-Based and Community Programs, which would supposedly use religion to transform the lives of the poor. But there was no there there. John DiIulio, the office’s first head, lamented the “virtual absence as yet of any policy accomplishments that might, to a fair-minded nonpartisan, count as the flesh on the bones of so-called compassionate conservatism.” In Washington, as in Austin, Bush’s real agenda was massive tax cuts geared to the rich. On his watch, America’s poverty rate rose even before the Great Recession. Then it went through the roof.

Now Jeb is trying something similar. If George W. in 1999 set out to prove that he’s not Newt Gingrich, Jeb is out to prove he’s not Mitt Romney, whose perceived callousness towards the 47 percent helped doom his presidential chances. So Jeb announced his candidacy at Miami-Dade College, two-thirds of whose students are Latino. He filled his announcement video with African American and Latino strivers, who credit him for their success. And he named his Super PAC, “The Right to Rise.”

To hear Jeb tell it, what made all this rising possible in Florida was his educational policies, which allowed students in bad public schools to attend charter or private schools. But there’s not much evidence for this. Yes, Florida fourth graders, whose reading scores had been below the national average when Jeb took office, had surpassed the national average by the time he left. But former University of South Florida education professor Sherman Dorn attributes that less to school choice than to Jeb’s laudable decision to hire more primary school reading specialists—a decision he doesn’t talk about much on the stump, perhaps because it sounds like big government. When I asked University of North Florida professor Matthew Corrigan, author of Conservative Hurricane: How Jeb Bush Remade Florida, to explain the rise in scores, he pointed to the state’s refusal to let poor-reading third graders ascend to fourth grade, which led many to enroll in summer school and boost their scores. But Dorn and Corrigan also note that compared to the national average, Florida eighth graders showed far less improvement, and that even fourth graders showed significantly less improvement on math than on reading. As Dorn puts it, “Bush is correct that Florida’s children benefited from his time in office if children graduated high school at the end of fourth grade, and only evidence of general reading skills mattered. For most other independent test-score measures, the picture is less impressive.”

This isn’t to question Jeb’s sincerity. Like his brother, Jeb seems genuinely interested in the education of poor kids, a subject he talks about with more knowledge and more conviction than Romney or many of his current Republican rivals. But like his brother, his overall economic policies benefitted not Florida’s poor, but Florida’s rich. During Jeb’s time as governor, a real-estate boom filled the state’s coffers. (Conveniently for Jeb, it only crashed the year he left office.) And like his brother, Jeb responded to the economic windfall with large tax cuts for the rich. “A review of tax cuts enacted during Bush's terms,” noted the Gainesville Sun, “show the bulk of the cuts have aided businesses or investors.”

On his PAC website, Jeb declares that, “While the last eight years have been pretty good ones for top earners, they’ve been a lost decade for the rest of America.” But partly because of Jeb’s own policies, that observation is even more true of his time as governor. Between the late 1990s and the mid-2000s, Florida saw the sixth-highest growth in income inequality of any state.

Like Texas, Florida is also a state with vast numbers of uninsured: Almost a quarter of its non-senior citizen residents lack health coverage, the second-highest rate in the nation. Yet, like his brother, Jeb opposed efforts to expand coverage. When Florida Governor Rick Scott, a Republican, urged the state legislature in 2013 to accept the Obamacare money that would allow the state to expand Medicaid, Jeb opposed the move, falsely claiming that after “three or four years” Washington would pick up only 55 percent of the tab. (The feds will actually pick up 90 percent until at least 2020).

In 2000, the press paid too much attention to George W.’s rhetoric and persona and not enough to his policies. Now journalists have the chance to learn from that mistake. When it comes to the poor, Jeb’s offering the same basic formula as Romney and most of his rivals: tax cuts, deregulation, and school vouchers. Rhetorically, Jeb may be less condescending. When he talks about “the barriers right now on people rising up,” he may even show real passion. But it’s only the style that’s new. The substance is all too familiar.

When Writers Put Themselves Into the Story

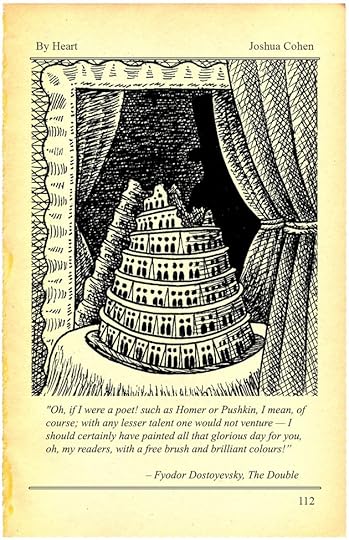

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Karl Ove Knausgaard, Jonathan Franzen, Amy Tan, Khaled Hosseini, and more.

Doug McLean

Doug McLean As a teenager, the novelist Joshua Cohen loved Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novella The Double for its eerie conceit, in which a man encounters a stranger who looks exactly like himself. But Cohen returns to the book, today, for the strange, thrilling moment that opens the fourth chapter: In an unusual narrative salvo, Dostoyevsky dispenses with his third-person narration and begins speaking to the reader as himself.

In our conversation for this series, Cohen said this gesture dramatizes the anxiety novelists feel about the texts they write—the books that, in a sense, become doppelgängers stalking their creator. After examining the literary origins of The Double’s story, Cohen explained his attraction to writers (from Cervantes to David Foster Wallace) who write themselves into their fictions, his mistrust of the third-person narrative voice, and the crises novelists face in the Internet age: Who’s talking? Who’s listening? And how should we speak?

Related Story

To Write a Great Essay, Think and Care Deeply

Cohen’s new novel, Book of Numbers, is a kind of doubles story, too; the book’s two main characters share their author’s name. The premise: Joshua Cohen, a floundering novelist, is hired to ghostwrite the memoir of Joshua Cohen, founder of Tetration—a Google-sized tech company redefining the Internet search. The money’s good, but there’s a catch. The non-disclosure agreement is so muscular that, in order to complete the book, Joshua Cohen (the writer) must essentially erase himself, effectively becoming his subject. As we become increasingly connected, Cohen suggests, we must cherish—more than ever—the power of the singular, individual voice.

In a review for The New York Times, Dwight Garner called Book of Numbers “more impressive than all but a few novels published so far this decade.” Joshua Cohen is also author of the novel Witz and the story collection Four New Messages, among other books. A critic for Harper’s, he lives in New York City, and spoke to me by phone.

Joshua Cohen: I first read Dostoyevsky when I was 14 years old, and was entranced. Dostoyevsky truly is a writer for 14-year-olds, and I mean that in the most approving way—approving of his energy, and rage, his endless pessimism, and endless innocence. There’s something especially adolescent—especially half-cracked, and sweaty—about The Double, which might’ve been the first book of his I read. When Golyadkin bumps into a stranger who appears to be him, or exactly like him, we aren’t sure if our hero’s haunted by a ghost, or suffering a psychosis. Which is to say, we aren’t sure which world we’re in. Ancient or modern? Magic or science? Ultimately, the plot will pass judgment—but until then, the ambiguity intrigues.

The doubles tale found its way from folklore into literature during the Enlightenment, whose concern for individual rights was romanticized into two separate, even contradictory, strains. That destiny or fate could be controlled, but urges couldn’t—that if you wanted to leave hearth and home, you needed to. Impulses were imperatives: To go abroad, self-fictionalize, and become another person.

The earliest doubles tales take on two forms. One is where the double escapes—from your reflection in the mirror, or in the water—or else it’s your shadow that escapes, and ventures into the world to do its business, or to do your business: desublimating all your appetites, acting out all your suppressed or repressed desires. Traditionally, this version concludes with a character dueling with his double—to assert his claim over a woman, or just over his original uniqueness. But if the double dies in the duel, the original dies too—it’s a fairly convoluted way of committing suicide.

Then there’s the second form of the doubles tale, where the double emerges from the original, only to return, and become reintegrated—through an occult spell, or a technological feat. But the doubling of this version is most frequently bound to cycles, as if indoor urban humanity were attempting to more firmly root itself in the seasons and phases from which it’d been alienated—from the full moon that causes hairs and snouts to sprout and sends werewolves out to go ravage the fields.

For the first type I’d cite the Germans. In E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “Die Geschichte vom verlornen Spiegelbilde” [“The Story of the Lost Reflection”], a stolid, gloomy burgher visits Italy, is enchanted by a local temptress, and leaves his double behind in her embrace. For the second type I’d cite the English. In Robert Louis Stevenson’s Jekyll & Hyde, the hero decides on the terms of his transformation, in a process that’s explained not through the supernatural but the natural, or at least through biochemistry.

Other classics of the genre have been hybrids: Hoffmann’s “Die Doppeltgänger” [sic] is the story of conjoined twins who are also writers—rivals in art, rivals in body—each fighting to be, but unable to be, independent of the other. Edgar Allan Poe’s “William Wilson” is the story of how guilt splits a personality into schizophrenia: The second self is the conscience, always latent, or mental, and manifesting physically only when the original cheats at cards, or tries to cheat with a married woman.

To Freudians, the double is the nocturnal counterpart to the daytime bourgeois—the embodiment of the id, dispensing with law, religious strictures, monogamy, propriety. To Marxists, the double is the mascot of mass-production: a person who looks and sounds and acts like you, who doubles your capacity for labor. The double’s existence represents the strain against time, and against limited resources of energy: the double works more so you can play more, produces more so you can consume more. It’s a fantasy of slavery—of having, if not being, your own slave.

When Golyadkin bumps into a stranger who appears to be him, or exactly like him, we aren’t sure if our hero’s haunted by a ghost, or suffering a psychosis.The Double, the book by Dostoyevsky, can survive any reading—even a deconstructive reading, in which the primal doubling isn’t between the hero Golyadkin and his identical avatar, but between Golyadkin and the author himself.

Golyadkin is a civil servant in St. Petersburg, but hasn’t climbed the ranks: He’s unintentionally too crude, rude, and curt, and has a tendency to blunder through every encounter. Enamored of his supervisor’s daughter, Klara, he shows up to her birthday party early and stays too late, insults his fellow guests by making nervous remarks, makes a fool of himself by trying to dance, and finally gets himself ejected. It’s at that point, wandering the embankment by the Neva, that he finally comes face to face with the man who turns out to be him. Another him.

Reading about Dostoyevsky’s life during the writing of The Double reinforces the suspicion that he shared Golyadkin’s predicament. By which I mean that Dostoyevsky’s not just writing a doubles story, he’s writing a doubled story: a version of Gogol’s The Overcoat, with a few wrinkles of The Nose. He’s also trying to write a second book to surpass, or equal, his first—Poor Folk, which was praised and even financially successful. The Double’s phantom themes are the author’s anxieties: about not being as talented as Gogol, or even as his own younger self.

This anxiety breaks out in the extraordinarily strange, break-the-fourth-wall opening to the book’s fourth chapter. It begins with a description of that party, which Golyadkin’s essentially crashing:

That day the birthday of Klara Olsufyevna […] was being celebrated by a brilliant and sumptuous dinner-party, such as had not been seen for many a long day within the walls of the flats in the neighbourhood of Ismailovsky Bridge—a dinner more like some Balthazar’s feast, with a suggestion of something Babylonian in its brilliant luxury and style, with Veuve-Clicquot champagne, with oysters and fruit from Eliseyev’s and Milyutin’s, with all sorts of fatted calves, and all grades of the government service. This festive day was to conclude with a brilliant ball, a small birthday ball, but yet brilliant in its taste, its distinction and its style …

An upscale ball deserves an upscale writer, is the implication: Dostoyevsky elevates his language, mock-elevates it, makes reference to the Bible and Semitic Antiquity, name-checks Veuve-Clicquot. But then this posturing’s suddenly interrupted—by the authorial “I,” Golyadkin-clumsy, barging in, and directly addressing the reader:

Oh, if I were a poet! such as Homer or Pushkin, I mean, of course; with any lesser talent one would not venture—I should certainly have painted all that glorious day for you, oh, my readers, with a free brush and brilliant colours! Yes, I should begin my poem with my dinner, I should lay special stress on that striking and solemn moment when the first goblet was raised to the honour of the queen of the fete. I should describe to you the guests plunged in a reverent silence and expectation, as eloquent as the rhetoric of Demosthenes …

I should describe this scene, is how Dostoyevsky narrates this scene, I should describe its food and drink and music and dress—but I can’t, because I’m not welcome here either, as a writer. Dostoyevsky laments not being up to the task, even as he’s completing the task—which is not to write about a revel, so much as it is to exorcise self-doubt.

This rhetorical doubling reinforces the book’s theme in a manner far more sophisticated than Dostoyevsky is usually given credit for. Perhaps the decision to do this wasn’t a decision, though—perhaps it was unconscious.

I spent my 20s unhealthily fascinated by the fact that fiction writers had been appearing as writers in their own fictions forever—as early as the ages of Cervantes and Sterne, as late as the ages of Gilbert Sorrentino, William H. Gass, Robert Coover, John Barth, William T. Vollmann, and David Foster Wallace. My reading of their texts had two consequences: It made me mistrust the unacknowledged narrators of third-person omniscience, and confirmed my debt to Dostoyevsky, for introducing me to this technique.

I was deep into my 30s, however, before realizing that Dostoyevsky’s neuroses weren’t exclusively literary—because if the writer’s anxious about how to write, the hero’s anxious about how to speak, and the reader must be too.

I’ll explain: Throughout The Double Golyadakin gets himself into trouble because he’s never sure how to express himself in public—outside his own head, or outside his own internal monologue. He doesn’t know how to present himself socially—or, in a contemporary phrasing, he doesn’t know which self to present, struggling as he is with a decaying class system, stagnant bureaucracy, Godlessness, materialism, precarity, and dread—all of which have rendered him incapable of appropriate behavior, or even of defining appropriate behavior, in front of friends, lovers, colleagues, the church, the state, himself. And I think we’re living in a culture like that today.

Writers today are writing for an unprecedentedly vast audience. It’s daunting if not damaging to speak to everyone directly. The larger your audience, the smaller your vocabulary, and range of referents—the fewer your means of expression. You can’t rely on the luxury of intimacy.

Writers today are writing for an unprecedentedly vast audience. You can’t rely on the luxury of intimacy.Say you’re an American novelist, published by the largest publishing house in the world. Their goal is to make as much money from you as possible, to have as many people read your book in as many formats as possible. How can you hope to speak intimately to the numbers of people that represent the book sales required? But also how can you not? This bind becomes even more fraught the more you’re writing from a minority perspective: You’re forced to explain your subculture to an incomprehensible and uncomprehending mass, and so you become the translator, the interpreter, the totem or symbol of your subculture, and not an individual, not an artist.

An immense audience makes the discernment of humor more difficult, for example. Humor has a lot to do with shit and piss and fucking—it’s impossible, or nearly impossible, to be funny while working clean. Humor has a lot to do with saying the odious aloud, and so ridding yourself of shame. But with an audience the size of the world, there’s always going to be someone offended by something. Not to mention that pretentious word: “discourse,” which with an increase in the volume of communications, and communicants, must be compressed, reduced, for practicality’s sake. Expressions are to be quantified—qualifications are extraneous.

Incidentally, Dostoyevsky can be funny, but never on purpose.

Historically, many periods—many genres of certain periods—have benefitted from accepted, common valences of rhetoric: Think of form letters, think of crime fiction. What we call the modern is just the awareness of an antipathy between what we want to say and how it needs to be said to be comprehended—to be widely comprehended.

The books that have been the most meaningful to me have been made of this clash, between individual and audience. They’re doubles of neither, and yet of both.

June 15, 2015

Can Jeb Bush Make Republicans Believe?

MIAMI—Things ought to be pretty good for Jeb Bush right now. The former Florida governor leads by a narrow margin in national polls for the Republican presidential nomination, and by a wider margin in New Hampshire. He is overwhelmingly dominant in fundraising. And he does not lack for connections to the Republican donors, officials, and grandees collectively known as "the Establishment."

Yet before Bush's campaign could even officially begin on Monday, it seemed to be falling apart. His staff was in turmoil, the apparent result of tensions between new hires and longtime loyalists and potential opponents, unintimidated, kept jumping into the race. Bush's poll numbers, while still good enough for first place in a 15-way contest, have been on a downward trajectory since he stepped out on the campaign circuit. Pundits have compared him to Rudy Giuliani, the former New York mayor who led the field in the early run-up to the 2008 primaries, only to see his candidacy collapse when Republican activists in early-voting states turned their backs. The party that nurtured Bush's father and older brother seemed disinclined to grant him the same deference.

And so the stakes were high as Bush took the stage here on Monday, in a community-college gymnasium in a heavily Cuban neighborhood. The arena was packed with a diverse and passionate crowd (about 3,000, according to the campaign). They carried inflatable thundersticks and red-and-white signs with the candidate's exclamatory new logo, "Jeb!" (in Spanish: "¡Jeb!"). Bush was preceded onstage by a family of Cuban salsa musicians; an African American pastor; a Colombian American advocate for children with disabilities; his own Mexican American son, Texas Land Commissioner George P. Bush; and two slickly produced biographical videos. The ambiance, some noted, was that of a national convention in miniature, as if Bush could project his way to the nomination by acting as if he'd already achieved it.

Bush's speech maintained the ruse. He attacked not his Republican rivals but President Obama, Hillary Clinton, and "the progressive agenda." He promised 4 percent growth and 19 million new jobs, through a regimen of tax and spending cuts. He promised school choice, religious liberty, and a rebuilt military. He spoke a few sentences in fluent Spanish. "Not a one of us deserves the job by right of resume, party, seniority, family, or family narrative," he said. "It’s nobody’s turn. It’s everybody’s test, and it’s wide open."

Bush leaned hard on his Florida record, which his campaign has indicated will be the focus of his relaunched message. Education reform—a far-reaching expansion of vouchers, charter schools, and high-stakes testing, which critics say hollowed out the public education system with questionable results—was a centerpiece of his tenure. The economy grew, though largely on the back of a population and real-estate boom that would crash to a halt shortly after he left office. Bush enjoyed broad, robust popularity and a reputation for seriousness and determination. In the audience after the speech, I met a Democrat and environmentalist named Jenny May who said she passionately supported Bush since working with him on Everglades preservation. “He sits down at the table and he listens to everyone,” she said. “He walks the walk.”

As written, Bush's speech did not mention immigration. In the past few years, he has written a whole book advocating immigration reform and said that many undocumented immigrants are guilty only of “an act of love.” His position has left Bush in a difficult bind. In a general election, support for immigration reform is broadly popular, particularly with the Hispanic voters Republicans will need to win—but many committed GOP activists are adamantly against it. Activists on the other side of the debate, meanwhile, criticize Bush for not going far enough. Midway through Bush's speech, a row of spectators suddenly stood up and tore off their overshirts, revealing neon-yellow T-shirts underneath that spelled out “LEGAL STATUS IS NOT ENOUGH” one letter at a time.

The crowd tried to shout down the protesters (who, having made their point, filed out through a nearby door), but Bush took the bait: “The next president will pass meaningful immigration reform so that that will be solved—not by executive order,” he said. It was not exactly a commitment, and it was cloaked as an implicit attack on Obama. But it was a signal that Bush didn't intend to try to avoid the issue.

As a speaker, Bush is (like Hillary Clinton) workmanlike at best. Engaging, if intense, in one-on-one interactions, he often seems bored with the choreography of public speaking. Throughout Monday's address, he had a slightly panicked look in his eyes; pausing to let the crowd cheer, he clasped his hands in front of him and stepped away from the podium, looking around uncertainly. Clinton's kickoff speech on Saturday was mostly devoid of pageantry—there was, for example, no parade of introductory speakers—as if to strip away her larger-than-life aura and bring her down earth. Bush's presentation was the opposite, a campaign trying to build its man up and convince people he was bigger than he seemed.

What has gone wrong for Bush so far? Some have characterized it as a policy problem—the party has moved right since he was in office, from 1998 to 2006, and its activist base loathes the Common Core educational standards, which Bush championed, as well as immigration reform. Others have theorized that the problem was one of perception, pointing out that Bush racked up a slew of conservative accomplishments as governor—the party activists elsewhere just had not gotten the message. (“We're not talking about a health-care bill in Massachusetts,” former Senator Mel Martinez told me, an implicit jab at 2012 nominee Mitt Romney. “He had a very conservative record as governor. He ended affirmative action!”)

My own view is that Bush's problem has mainly been one of performance: He just hasn't impressed people since reemerging on the political scene. Republicans were open to the idea of him—in a CNN poll in December, when he first began exploring a run, he had the support of 23 percent. But as they watched him give mediocre speeches and fumble obvious questions—notably the one on Iraq, which took him days to get straight—their ardor dimmed and his standing dropped.

Republicans, who have lost the popular vote in five of the last six presidential elections, badly want to win this time around. Many of the activists I've spoken to—even staunch conservatives in rural Iowa—are concerned primarily with nominating a candidate who can win a general election; they are haunted by the unexpected defeat in 2012, and with it, a bewildering sense that they are out of sync with their country's mainstream. But Bush's stumbles—and their array of other options—make them wonder if he is the candidate who can turn the tide. Why compromise their beliefs for someone who can’t close the deal?

On Monday, Bush tried to impress them with a vision of the future with him as the nominee. In the coming months, he must convince them to believe in it.

‘You've Come a Long Way, Baby’: The Lag Between Advertising and Feminism

In July of 1968, Philip Morris released a spin-off of its popular Benson and Hedges cigarette brand. The modified cigarette, in design narrower and longer than Philip Morris’ previous offerings, was launched during a time that found many Americans newly aware of the dangers of smoking. It was meant, as a distraction from that, to evoke elegance—a certain daintiness. Which is to say that the new cigarette brand was marketed toward women. Virginia Slims, Philip Morris announced in its ads, were “tailored for your hands—for your lips.” And they were, in all that, “slimmer than the fat cigarettes men smoke.”

But the cigarettes also had, the company suggested, a deeper appeal. Virginia Slims were, in Philip Morris’ presentation of them, tobacco-infused celebrations of progress itself. And their marketing was broad in every sense of the word. Virginia Slims were aimed at the newly liberated (or, well, “liberated”) women of the ‘70s—women whose lives had been transformed by advances in politics and medicine, women who were newly able to think about “careers” as well as “jobs,” women who were able to consider divorce in a way that would have scandalized their mothers and grandmothers. These were women, essentially, who were able, for the first time, to think about their lives playing out on somewhat of an equal footing with men. And ads for Virginia Slims, the cigarette that celebrated this equality by contradicting it, spoke to those women as directly as they did breezily: “You’ve come a long way, baby.”

How marketing defined and influenced an era

How marketing defined and influenced an eraRead More

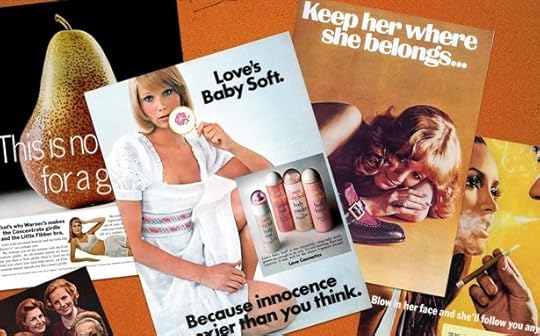

This was, of course, a promise about the world much more than an accurate reflection of it. Advertising, aimed so squarely at the public id, has a way of cutting through noise and niceties and reflecting what people really want. Or at least what advertisers have decided they really want. And what women of the ‘70s really wanted, the (mostly male, mostly white) advertisers of the time assumed, was similar to what many of them still want today, despite all the progress that has been made in the meantime: to be attractive to men.

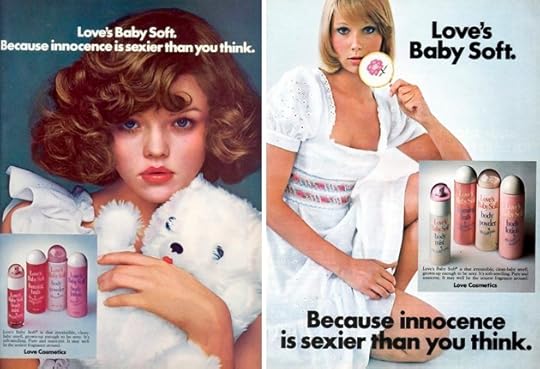

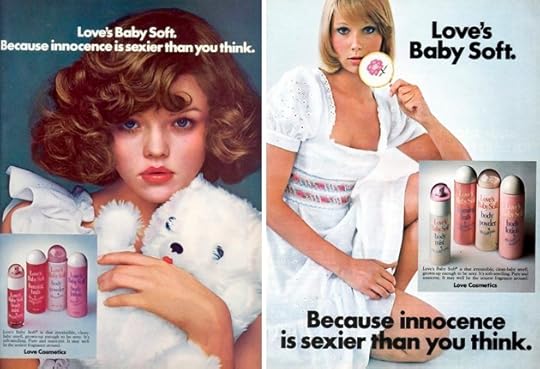

Take, for example, these Lolita-esque ads for Love’s Baby Soft—“perhaps the most feminine of all feminine products to have ever existed on Earth,” as this cultural history of the product sums it up. Baby Soft, a scent that was a kind of proto-Axe for Girls, was developed by the pharmaceutical company Smith & Kline, and released in 1974. Its oooof-inducing slogan was, “because innocence is sexier than you think.” It was unclear, oooofingly, whether the innocence in question was being marketed to women … or young girls.

The campaign’s print ads were accompanied by a TV spot that was approximately 1,000 times more disturbing, by today’s standards, than the still images. The ad, narrated by a man whose voice alone evokes Burt Reynolds’ mustache, promises that Love’s Baby Soft offers the scent of “a cuddly, clean baby … that grew up very sexy.”

Women, buying products based on what ads tell them men want: This, of course, is a tale as old as Madison Avenue, and also as old as time itself.

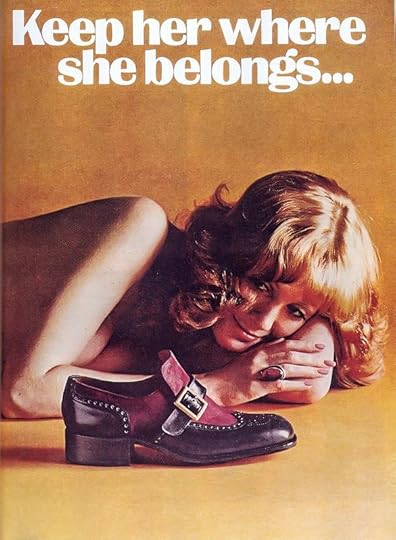

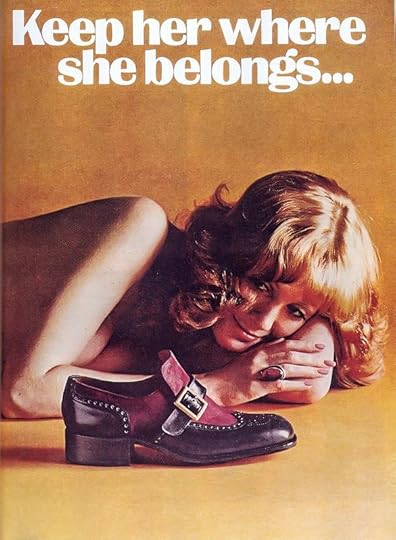

Sometimes the campaigns were explicit about that. Take this ad for Weyenberg Massagic shoes, published in (yep) Playboy in 1974 and submitted to Ms. Magazine’s “No Comment” section:

The ad was, unsurprisingly, controversial—not just because of its slogan or its bare-chested model, but also because of its core assumption: that the way to keep a woman “where she belongs,” if that is indeed your goal, is to buy her things. Captivation by way of consumerism.

Weyenberg, Jerome Rodnitzky notes in Feminist Phoenix: The Rise and Fall of a Feminist Counterculture, reveled in the controversy. “Weyenberg is taking the first positive stand for masculinity,” the brand declared, expressing a sentiment that will feel faintly familiar today, “against the influences of the women’s liberation movement.” The brand, it explained, was trying to target the men who rejected “effeminate and women’s liberation appeals.”

In response to this logic, the National Organization for Women gave Weyenberg a mocking prize: the “Keep Her in Her Place Award.”

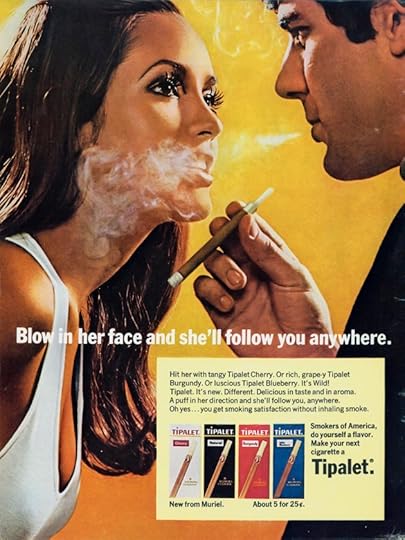

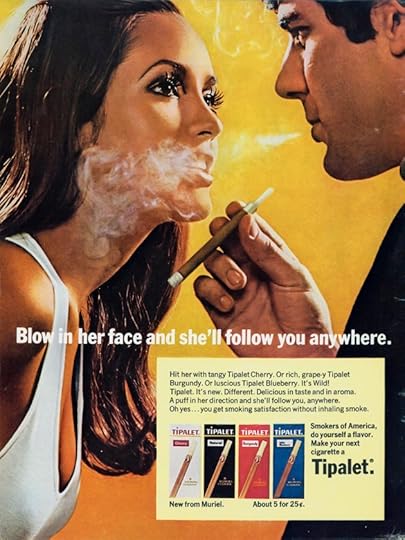

N.O.W.’s nominating committee might have also enjoyed this gem, first issued in 1969 but extant into the ‘70s:

As Stanford’s School of Medicine notes, in its

What’s striking, seeing ads like these through the lens of the 21st century, is—in spite of everything—their familiarity. Feminism may have, in the decades that intervened between the ‘70s and today, solidified into a set of conventions and norms. The women’s movement may have become absorbed into the culture—into our conversation and our media and our habits of mind. We may take for granted the idea that women’s bodies and lives are much more than playthings for men. We may assume that if the arc of history bends toward justice, that goes for matters of sex and gender, too. But pop culture also has a way of lagging behind political movements. And many ads today—be they for underwear or footwear or baby-powder-scented body spray—are in their way as retrograde as these specimens from the ‘70s. They can assume that women’s consumer decisions are based on conceptions of male desire. They can assume that the key decision-maker in a commercial transaction, regardless of who spends the money, is a man.

We may well have come, in the words of Virginia Slims ads, “a long way, baby.” But we still have far—very far—to go.

'You've Come a Long Way, Baby': The Lag Between Advertising and Feminism

In July of 1968, Philip Morris released a spinoff of its popular Benson and Hedges cigarette brand. The modified cigarette, in design narrower and longer than Philip Morris’s previous offerings, was launched during a time that found many Americans newly aware of the dangers of smoking. It was meant, as a distraction from that, to evoke elegance—a certain daintiness. Which is to say that the new cigarette brand was marketed toward women. Virginia Slims, Philip Morris announced in its ads, were “tailored for your hands—for your lips.” And they were, in all that, “slimmer than the fat cigarettes men smoke.”

But the cigarettes also had, the company suggested, a deeper appeal. Virginia Slims were, in Philip Morris’ presentation of them, tobacco-infused celebrations of progress itself. And their marketing was broad in every sense of the word. Virginia Slims were aimed at the newly liberated (or, well, “liberated”) women of the ‘70s—women whose lives had been transformed by advances in politics and medicine, women who were newly able to think about “careers” as well as “jobs,” women who were able to consider divorce in a way that would have scandalized their mothers and grandmothers. These were women, essentially, who were able, for the first time, to think about their lives playing out on somewhat of an equal footing with men. And ads for Virginia Slims, the cigarette that celebrated this equality by contradicting it, spoke to those women as directly as they did breezily: “You’ve come a long way, baby.”

How marketing defined and influenced an era

How marketing defined and influenced an eraRead More

This was, of course, a promise about the world much more than an accurate reflection of it. Advertising, aimed so squarely at the public id, has a way of cutting through noise and niceties and reflecting what people really want. Or at least what advertisers have decided they really want. And what women of the ‘70s really wanted, the (mostly male, mostly white) advertisers of the time assumed, was similar to what many of them still want today, despite all the progress that has been made in the meantime: to be attractive to men.

Take, for example, these Lolita-esque ads for Love’s Baby Soft—“perhaps the most feminine of all feminine products to have ever existed on Earth,” as this cultural history of the product sums it up. Baby Soft, a scent that was a kind of proto-Axe for Girls, was developed by the pharmaceutical company Smith & Kline, and released in 1974. Its oooof-inducing slogan was, “because innocence is sexier than you think.” It was unclear, oooofingly, whether the innocence in question was being marketed to women … or young girls.

The campaign’s print ads were accompanied by a TV spot that was approximately 1,000 times more disturbing, by today’s standards, than the still images. The ad, narrated by a man whose voice alone evokes Burt Reynolds’ mustache, promises that Love’s Baby Soft offers the scent of “a cuddly, clean baby … that grew up very sexy.”

Women, buying products based on what ads tell them men want: This, of course, is a tale as old as Madison Avenue, and also as old as time itself.

Sometimes the campaigns were explicit about that. Take this ad for Weyenberg Massagic shoes, published in (yep) Playboy in 1974 and submitted to Ms. Magazine’s “No Comment” section:

The ad was, unsurprisingly, controversial—not just because of its slogan or its bare-chested model, but also because of its core assumption: that the way to keep a woman “where she belongs,” if that is indeed your goal, is to buy her things. Captivation by way of consumerism.

Weyenberg, Jerome Rodnitzky notes in Feminist Phoenix: The Rise and Fall of a Feminist Counterculture, reveled in the controversy. “Weyenberg is taking the first positive stand for masculinity,” the brand declared, expressing a sentiment that will feel faintly familiar today, “against the influences of the women’s liberation movement.” The brand, it explained, was trying to target the men who rejected “effeminate and women’s liberation appeals.”

In response to this logic, the National Organization for Women gave Weyenberg a mocking prize: the “Keep Her in Her Place Award.”

N.O.W.’s nominating committee might have also enjoyed this gem, first issued in 1969 but extant into the ‘70s:

As Stanford’s School of Medicine notes, in its

What’s striking, seeing ads like these through the lens of the 21st century, is—in spite of everything—their familiarity. Feminism may have, in the decades that intervened between the ‘70s and today, solidified into a set of conventions and norms. The women’s movement may have become absorbed into the culture—into our conversation and our media and our habits of mind. We may take for granted the idea that women’s bodies and lives are much more than playthings for men. We may assume that if the arc of history bends toward justice, that goes for matters of sex and gender, too. But pop culture also has a way of lagging behind political movements. And many ads today—be they for underwear or footwear or baby-powder-scented body spray—are in their way as retrograde as these specimens from the ‘70s. They can assume that women’s consumer decisions are based on conceptions of male desire. They can assume that the key decision-maker in a commercial transaction, regardless of who spends the money, is a man.

We may well have come, in the words of Virginia Slims ads, “a long way, baby.” But we still have far—very far—to go.

Why the Pope's New Climate-Change Doctrine Matters

According to the Catholic Church, a number of acts qualify as mortal sins: murder, apostasy, stealing from the poor, etc. But in the eyes of a Vatican official who spoke to Bloomberg News on Monday, there’s another kind of sin that qualifies as a “heinous act”: when a newspaper leaks a papal encyclical three days before it’s supposed to come out.

For more than a year, Pope Francis and his close advisors have been preparing this document, called Laudato Si, or Praised Be. The text focuses on environmental stewardship and, in particular, the effects of climate change on human life. The themes are directly in keeping with the rest of his papacy: When he was elected to the office, he told journalists he took the name “Francis” in honor of St. Francis of Assisi, who stood for the poor and for peace, and was a “man who loved and cared for creation ... in this moment we don’t have such a great relationship with the creator.” The official copy of the encyclical doesn’t come out until Thursday, but on Monday, the Italian magazine L’Espresso leaked an Italian version, which Church officials are calling a “draft.”

Related Story

Pope Francis's Radical Environmentalism

The Vatican has reacted so strongly to the leak because this encyclical is a very big deal within the Catholic world. It’s one of the most formal statements the pope can make about Catholic doctrine, and it’s the first of his papacy. (Last spring, he released another piece of writing on the topic of poverty, but it was a slightly less formal document called an apostolic exhortation.) Francis chose a theme that’s long been a focus for pontiffs: Benedict XVI is cited 21 times in the draft version of the text, and John Paul II is cited 22 times. But this is the first instance in which the environment has been a topic of an encyclical. “No pope has ever issued a statement [about the environment] on this level of document,” said Kevin Irwin, a priest and theologian who teaches at the Catholic University of America. “John Paul put it into a World Day of Peace message, but a World Day of Peace message is down the rung on the ladder of the hierarchy of Catholic documents. And Benedict gave a number of homilies and speeches on it, but never a document on this level.”

In the draft version of the document, the pope makes a strong case that humans are at fault for the degradation of the environment. “Numerous scientific studies indicate that the major part of global warming in recent decades is due to the high concentration of greenhouse gas … emitted above all because of human activity,” he writes. His thinking on the environment connects with other major themes of his papacy, including care for the poor and the importance of human life. In the draft, he writes that the heaviest impacts of climate change “will probably fall in the coming decades on developing countries. Many poor people live in areas particularly affected by phenomena related to heating, and their livelihoods strongly depend on natural reserves and so-called ecosystem services, such as agriculture, fisheries, and forestry.” He also discusses the effects on immigrants and refugees: Changing environmental conditions force them into a position of economic uncertainty in which they can’t sustain livelihoods, he writes.

What this encyclical is not is a love letter to Greenpeace—although Francis is embracing the idea of environmental stewardship, he's doing so as a Catholic theologian, not a liberal activist. Especially in the American press, the pope’s encyclical has often been discussed in terms of U.S. politics, where a significant minority of mostly Republican voters and legislators deny the existence of climate change. Earlier this month, Oklahoma Sentor James Inhofe said of the encyclical, “The pope ought to stay with his job, and we’ll stay with ours.” Rick Santorum, a Catholic former U.S. senator and presidential candidate, advised the pope to “[leave] science to the scientists and [focus] on what we’re good at, which is theology and morality.”

What this encyclical is not is a love letter to Greenpeace—Francis is embracing environmental stewardship as a Catholic theologian, not a liberal activist.But, in fact, the topic of this encyclical is squarely in the pope’s wheelhouse. Francis links his call for environmental stewardship to the book of Genesis, and he repeatedly couches environmental degradation in theological language. “That human beings destroy the biological diversity in God's creation; that human beings compromise the integrity of the earth and contribute to climate change, stripping the earth of its natural forests or destroying its wetlands; that human beings pollute the water, soil, air; all these are sins,” he writes.

Although American Catholics are a sizable group, they’ve got nothing on the whole of Francis’s church: There are 1.2 billion Roman Catholics in the world, and nearly 40 percent of them live in South America, not North America. Sub-Saharan Africa is another area of rapid growth for the Church; demographers expect the number of Christians in the region to double by 2050 to nearly 1.1 billion, although some of those will be Protestants. Considering that Latin America and Africa are Francis’s two biggest “constituencies,” it’s no wonder that the environment is a point of pressing concern for the global Church: Climate change affects those who are poor and live in developing countries much more intensely than those who live in the developed world. Francis is coming out against climate change, yes. But he’s mostly continuing the focus of his entire papacy: speaking for the world’s poor.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower