Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 410

June 18, 2015

‘Hate Crime’: A Mass Killing at a Historic Church

Updated at 2:50 p.m. EST.

Dylann Roof, the 21-year-old who is suspected of a mass killing at a historic black church in Charleston, South Carolina, has been taken into law enforcement custody. Nine people were killed and at least one other was wounded in the shooting, which occurred at a Wednesday night prayer meeting at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, one of the oldest black churches in the South.

The Shootings and the Aftermath

Roof sat for about an hour with congregants in a weekly prayer meeting, Charleston Police Chief Greg Mullen said in a press conference. Then, shortly after 9 p.m., he allegedly opened fire.

A cousin of one of the victims, Sylvia Johnson, relayed a survivor’s account to NBC News claiming that the shooter reloaded his weapon five times. According to Johnson, the gunman told the survivor, “I have to do it. … You rape our women and you're taking over our country. And you have to go.”

“I will say that this is an unspeakable and heartbreaking tragedy in this most historic church, an evil and hateful person took the lives of citizens who had come to worship and pray together,” Charleston Mayor Joe Riley told reporters, according to the Post and Courier. Mullen went further in his remarks, saying,“I do believe this was a hate crime.”

As news of the shooting spread, locals gathered in the streets surrounding the church in an impromptu prayer session for the victims. By noon on Thursday, hundreds had gathered in local churches and on nearby streets to commemorate the dead, the Post and Courier said.

South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley issued her condolences after news of the shooting broke. “While we do not yet know all of the details, we do know that we’ll never understand what motivates anyone to enter one of our places of worship and take the life of another,” she said in a statement.

“Michelle [Obama] and I know several members of Emanuel A.M.E. Church,” President Barack Obama said at a White House press conference. “To say our thoughts and prayers are with them and their families and their community doesn’t say enough to convey the heartache and the sadness and the anger that we feel. Any death of this sort is a tragedy. Any shooting involving multiple victims is a tragedy. There is something particularly heartbreaking about that happening in a place in which we seek solace and we seek peace, in a place of worship.”

In his remarks, Obama linked the killings to a pattern of gun violence in the U.S.:

I’ve had to make statements like this too many times. Communities like this have had to endure tragedies like this too many times. We don’t have all the facts, but we do know that once again innocent people were killed because someone who wanted to inflict harm had no trouble getting their hands on a gun. Now’s the time for mourning and for healing, but let’s be clear: At some point, we as a country will have to reckon with the fact that this type of mass violence doesn’t happen in other advanced countries. It doesn’t happen in other places with this kind of frequency. And it is in our power to do something about it. I say that recognizing that the politics in this town foreclose a lot of those avenues right now. But it’d be wrong for me not to acknowledge it. And at some point, it’s going to be important for the American people to come to grips with it, and for us to be able to shift how we think about the issue of gun violence collectively.

The Iconic History of the Church

The targeting of Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal is particularly significant given its history and symbolism. One of the people killed was Clementa Pinckney, a South Carolina state senator and Methodist pastor at the church, and the youngest African African ever elected to South Carolina’s legislature. In a 2013 lecture posted on YouTube, Pinckney spoke about Emanuel A.M.E.’s significance to Charleston and the nation.

“Where you are is a very special place in Charleston,” Pinckney said in the lecture, addressing an audience of visitors to the church.

Pinckney continued:

In a nutshell, you can say that the African American church—and in particular, in South Carolina—really has seen it as its responsibility and its ministry and its calling to be fully integrated and caring about the lives of its constituents and the general community. ... Many of us don't see ourselves as just a place where we come and worship, but as a beacon, and as a bearer of the culture, and a bearer of what makes us a people. But I like to say that this is not necessarily unique to us; it's really what America is all about.

Could we not argue that America is about freedom—whether we live it out or not—but it really is about freedom, equality and the pursuit of happiness, and that's what church is all about. Freedom to worship, and freedom from sin, freedom to be fully what God intends us to be, and freedom to have equality in the sight of God. And sometimes you gotta make noise to do that. Sometimes, you maybe have to die, like Denmark Vesey, to do that. Sometimes you have to march, and struggle, and be unpopular to do that.

Emanuel A.M.E. is the oldest black church south of Baltimore, and one of the most storied black congregations in the United States. Its history is deeply intertwined with the history of African American life in Charleston. Among the congregation’s founders was Denmark Vesey, a former slave who was executed in 1822 for attempting to organize a massive slave revolt in antebellum South Carolina.

South Carolinians burned the church to the ground in response to the thwarted uprising; along with other independent black churches, it was shuttered in 1834. The church began to rebuild in 1865. It has continued to play a leading role in the struggle for civil rights.

The Briefcase: A Reality TV Show Straight From the Victorian Era

Though it’s a robust presence on the airwaves today, and has been since the 1990s, reality television can actually trace its origins back much farther than that. The cultural appetite for judging others and feeling worthy by comparison was strong a century ago in Victorian England, where “slum tours” offered the well-off the chance to see how the other, considerably poorer half lived. Philanthropists and curious members of the upper classes eagerly paid for the opportunity to gawk at London's worst neighborhoods, and the tours were especially thrilling thanks to the unspoken notion that money and morality were inextricably tied: The wealthy had earned their riches, and the poor had earned their rags. But this idea also led some activists in Victorian society to seek out the “virtuous poor”—the impoverished who were so inherently good that even the wealthy could admit they deserved better.

Related Story

TV’s Post-Recession Obsession With Stuff

Last month, CBS premiered the reality show The Briefcase. On the show, families in need are told they’re appearing in a “documentary about money,” handed a briefcase containing $101,000, and then asked how much they’d like to give to another struggling family. The twist? They don’t know that the people they’re evaluating have also received a briefcase of money and are judging how much they deserve to get. Each family gets the chance to wander through the other’s home, looking for signs of worthiness (artificial limbs resting against the wall, medical bills left out on a counter). And after an hour of viewers waiting to see how much money desperate people are honorable enough to hand over, there’s a meeting between the two families to rationalize, exchange money, and offer catharsis. It’s an O. Henry-esque short story of staged goodwill, and it’s as close to a Victorian slum tour as reality TV can get without a time machine.

The Briefcase is ostensibly about generosity in tough circumstances—a contestant from Wednesday’s episode opined that people should “show each other that if you’re falling down, we’re going to be here to pick you up.” But its structure encourages more judgment than empathy from its viewers. Each episode positions viewers to carry out their own assessment of the families on screen—how truly needy they are, and how authentic and generous they’ll prove to be. Vulture has pointed out the absurdity of how the contestants’ financial suffering compares to CBS CEO Les Moonves’s astronomical income, and The New Republic has declared The Briefcase to be part of a long tradition of “misery TV” that dates back to Queen for a Day, a reality-based show that debuted in 1945.

But The Briefcase’s cynicism runs deeper than its predecessors. It’s tapped into the 19th-century idea of moral worth as currency to be traded—the needy must prove they are the “virtuous poor” and worthy of better circumstances. This concept was perhaps most memorably depicted in the novels of Charles Dickens, where religious, humble, well-spoken, and grateful paupers won the sympathies of the wealthy. The upper classes reasoned to themselves that the invisible hand of Providence would act to reward the good—a belief that at once fit with the notion that the poor deserved their lot in life while reaffirming their own moral and class standing.

The Briefcase’s structure encourages more judgment than empathy from its viewers.It’s a concept born of the Victorians but infinitely renewable today. Ours is a time of perhaps even greater wealth inequality than the 19th century. NPR notes that the “85 richest people own as much as the poorest 50 percent of humanity,” while a 40-hour week at minimum wage isn’t enough to pay rent anywhere in the U.S. In this context, it makes sense that Victorian-level economic disparities have given birth to something with unintentionally 19th-century values like The Briefcase. The show seems to reassure viewers that the needy participants depicted on screen can raise themselves up, with their own humility, generosity, and tenacity. But this attitude redirects focus away from underlying problems. Some families that appear on The Briefcase are struggling because of holes in the social safety net—one family lacks health insurance, another lacks veteran support. The real solutions to those problems are more complicated and less TV-friendly than a briefcase full of money and the suggestion to play nice.

The entertainment value in The Briefcase lies, of course, in seeing goodness and altruism in people who might be reasonably expected to be selfish out of necessity. A needy family that’s humble and self-denying offers more comfort to onlookers than one that’s angry or desperate; a family that’s suitably grateful for humane treatment makes the onlooker feel like a better person. The Victorians were well aware of this particular benefit. The philanthropist and social reformer Beatrice Webb, Lady Passfield wrote in 1883:

[I]t is distinctly advantageous to us to go amongst the poor. We can get from them an experience of life which is novel and interesting ... contact with them develops on the whole our finer qualities, disgusting us with our false and worldly application of men and things and educating in us a thoughtful benevolence.

In order to reconstruct the virtuous poor for its audience, The Briefcase uses familiar storytelling techniques to build a narrative that encourages this moral stratification. The literary scholar Raymond Chapman notes in his 1994 book, Forms of Speech in Victorian Fiction, that in novels, the virtuous poor were often spared the transcribed drawl of the underclass, such as wide vowels and dropped h’s. Instead, writers honored them with “the giving of standard speech to virtuous but uneducated characters”—effectively a sympathetic edit meant to confer a certain nobility, and promote the character to personhood in the mind of the audience. On The Briefcase, this elevation occurs in a moment where a contestant vomits from the guilt of ever having wanted to keep money for herself. The audience is meant to see this epiphany as her noble elevation: The thought of not sharing her newfound wealth literally made her sick.

Edits like this are nothing new, nor is television that profits from the lamentable situations of others. Following the success of the Channel 5 poverty-porn series Benefits Britain: Life on the Dole, the BBC announced plans for a competitive reality show called The Hardest Grafter, which will allow low-income workers to “prove themselves” for an eventual cash prize of £15,000 (roughly $23,000). Despite subsequent outcry, the network has so far doubled down on its decision, claiming the series’s morals are in the right place by offering a venue to demonstrate how hard the poor work for their betterment.

Shows like The Briefcase demand a kind of performative morality from their contestants.This well-intentioned sentiment that people can “dis-pauperise” themselves recalls the Victorian workhouse, which offered a tidier version of the slum tour. The poor would live and perform menial tasks at a workhouse in exchange for minimal food and schooling, and visits from preachers and activists who’d stop by to judge the gratitude and virtue of the inhabitants. Shows like The Briefcase similarly demand this kind of performative morality from their contestants, whose hard work is only as good as they can convince the camera it is.

As such, reality TV exists in a delicate ecosystem: Audiences understand that a degree of illusion is necessary to build a story, but they expect enough verisimilitude in order to pass moral judgments. All it takes to throw a wrench in the audience’s perception of a “winner” is an obvious case of producer interference or a real-life disgrace. A current, deeply uncomfortable example is the Duggar family’s sex-abuse scandal. TLC has long positioned the Duggars somewhere between quirky sitcom and carnival sideshow (another Victorian mainstay that’s become reality-TV bedrock), but their TV-friendly, performative modesty has been shattered. The Briefcase will likely be free from such unanimous scrutiny for a little while longer; its audience (currently 5 million strong) is too aware of how reality TV works to feel manipulated by its carefully constructed charity, and not outraged enough to care about being sold a slum tour under the guise of tenderheartedness.

Still, the influence of reality TV that provokes moral condemnation is too strong to ignore, even if it’s nothing new. In an 1891 essay on socialism, the writer Oscar Wilde wrote that “a poor man who is ungrateful, unthrifty, discontented, and rebellious, is probably a real personality, and has much in him ... As for the virtuous poor, one can pity them, of course, but one cannot possibly admire them.” Words a reality-show casting agent could live by.

The Fight for Equality in Charleston, From Denmark Vesey to Clementa Pinckney

On Wednesday night, Dylann Roof, a 21-year-old white man, walked into a prayer meeting at Charleston’s Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. For an hour, he sat and listened to Clementa Pinckney, a South Carolina state senator and Methodist pastor at the church. Then he opened fire, killing nine, including Pinckney.

Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal is one of the oldest black churches south of the Mason-Dixon line, and its long history is intertwined with the struggle for civil rights. Among its founding members was Denmark Vesey, a free black man, who in 1822 plotted a slave revolt. The church remained a center of the black community after the Civil War, through the long decades of Jim Crow, and down to the present day.

To find out more, I turned to Douglas Egerton, a professor of history at Le Moyne College, and author of He Shall Go Out Free: The Lives of Denmark Vesey and The Wars of Reconstruction: The Brief, Violent History of America's Most Progressive Era. What follows is a condensed transcript of our conversation.

Appelbaum: Why was it important for blacks in the antebellum South to have their own churches in which they could worship, free of white supervision or control?

Egerton: The message that black slaves and freemen were getting was not what they wanted to hear. White church leaders stayed away from stories they would find dangerous: the Exodus, the brotherhood of all man.

More than that, when the A.M.E. church was founded in Charleston, it was the center of the black community. It was a church, it was a school, despite it being closed down because they were teaching literacy. It’s why the authorities regarded the A.M.E. church as so dangerous.

“Had there been no attacks on the church, there would’ve been no conspiracy.”Appelbaum: In 1822, Denmark Vesey is accused of plotting a slave revolt. He is one of 35 executed. How does that change the way that the church is viewed?

Egerton: The two main ministers knew something was going on, but were not complicit. One person said that Morris Brown counseled Vesey not to do this, because the risks were too high.

Because the church was the center of black cultural autonomy in Charleston, because it taught literacy, it was targeted by the authorities. The church was closed routinely: 1818, 1819, 1820.

Had there been no attacks on the church, there would’ve been no conspiracy. Slaves are never happy being slaves, but they have to weigh the odds. Even in a state that is 61 percent black like South Carolina, there are armed white militias. John C. Calhoun was the secretary of war, and prepared to use overwhelming force.

Appelbaum: How do the attacks on the church push Vesey into open revolt?

Egerton: It made it very clear that whites were never going to give them any sort of autonomy. In 1818, when the church is closed down, one of Vesey’s friends goes to Sierra Leone, and Vesey thinks of going. Then he decides he’s going to stay and see what he can do for his sons—he has sons who are still enslaved by his first two wives. Vesey is 54. His friends call him the old man—the average life expectancy for blacks at this time was 34 years. He wants to free slaves, and take them to live in Haiti.

Appelbaum: What happens to the church?

Egerton: It’s razed—literally burned down. The two ministers are actually put on trial because they have left the state to attend a conference. There’s a law that free blacks cannot leave South Carolina. The mayor effectively exiles the ministers to Philadelphia.

The congregation splits up. They worship underground. Some of them go to white congregations.

Appelbaum: When the church was rebuilt in 1865, the carpenter who designed it was Denmark’s son, Robert Vesey Sr. What role does it play in Reconstruction era Charleston?

Egerton: It’s a focal point for political organization. For most white politicians in the nineteenth century, they come out of law, they come out of business—these are the venues that give them a leg up. For blacks, the church is pretty much it. It is their place to congregate, to organize. And a large number of Union army chaplains get involved in organizing. They start organizing chapters of the Union League as a stepping-stone to political organization, which invariably meet in black churches. And that is why churches all across the south are constantly being attacked, being torched.

“53,000 black political activists have been assassinated. That’s more than the people who died at Gettysburg.”There are 1,510 identifiable people of color who hold political office in the south during Reconstruction. Disproportionately, they are veterans—and the largest single group, 243, are ministers.

For whites who don’t want to share political power, the churches become the targets. You can stop political movements through terror and through violence. One black congressman at the time, Robert Smalls, estimates 53,000 black political activists have been assassinated. That’s more than the people who died at Gettysburg.

A Methodist minister from Charleston, Benjamin Franklin Randolph, is assassinated in 1868 as he gets on a train. He was a state senator. It is not a coincidence that Clementa Pinckney, the minister who was killed yesterday, was also in the state senate. It’s the old mixture in South Carolina of religion and politics.

Appelbaum: Then the hopeful experiment of Reconstruction comes to an end. What role does the church play in the long decades of Jim Crow?

Egerton: They don’t abandon the struggle. There’s a march in 1969 that starts in the church. It remains the focal point for political struggle. People talk about Reconstruction ending; to a large extent it doesn’t. Whites give up, but blacks continue to fight on. And that continues to the present. Emanuel AME has a reputation as a church that is trying to keep the struggle alive.

Appelbaum: What is it about the existence of independent black congregations that has made them such targets?

Egerton: It allows for a kind of independence and autonomy and a launching point for political activity that some reactionary, supremacist whites don’t want.

The original plan for Denmark Vesey’s uprising is July 14, Bastille Day. It is moved back to midnight on June 16—they plan to free the slaves, and fight their way down to the docks—meaning the fighting will be on June 17. Historians don’t like coincidences. Either it’s a terrible coincidence, or he knows this history. The fact that June 17 would have been the day of the fighting is troubling.

Whites still refer to Vesey as a terrorist in Charleston; he was fighting for freedom. It looks like the terrorist was this young white man who shot up the church.

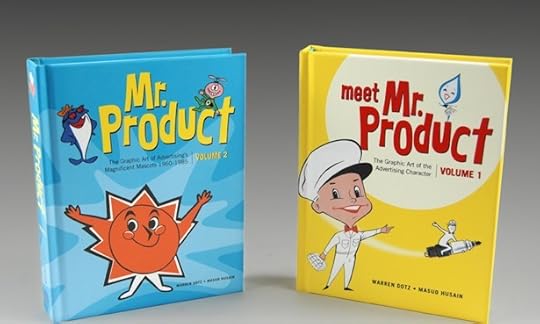

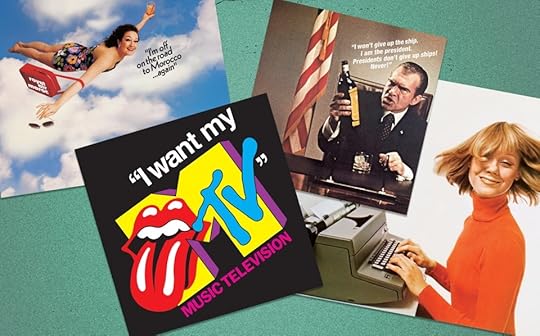

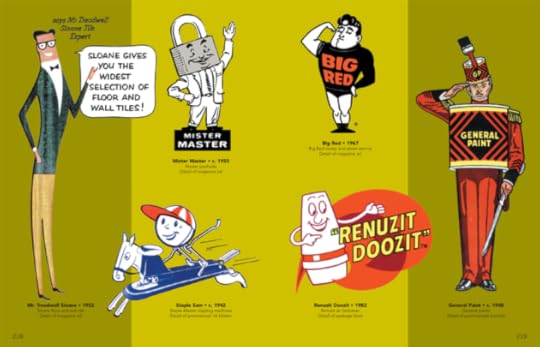

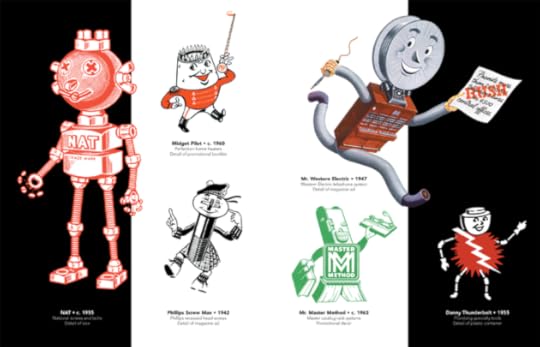

‘They're Grreeaat!’: The Enduring Charm of Advertising Characters

We’re all susceptible to their lure. They infiltrate our subconsciousness, colonize our homes, and supply us with everything from food to footwear, and in return we become loyal devotees. Such is the power of hundreds, even thousands, of advertising characters that help brands cultivate images of wholesome goodness—the Pillsbury Doughboy, Jolly Green Giant, Stay Puff Marshmallow Man, and Charlie the Tuna.

Related Story

Revisiting the Work of One of the 20th Century's Best Ad Men

These usually adorable, often anthropomorphic product proxies are nonetheless subversive. And those who believe themselves insulated from their power should pick up Warren Dotz and Masud Husain’s Meet Mr. Product: The Graphic Art of the Advertising Character Volumes 1 and 2 (Insight Editions), the latter installment of which was released in April. The books are based on a collection of logos, packaging, and brand spokescharacters the authors acquired over the course of 30 years.

Documenting advertising history and creating an exhibition isn’t Dotz’s primary job—he’s a dermatologist. But both he and his co-author Husain, a graphic designer, shared similar interests in collecting and in exploring the under-appreciated “art of commerce.” For Dotz, advertising characters are fascinating to study because they lie at the intersection of business, design, and the modern mythology of pop culture. Characters, Dotz figured, are not hard-sell pitchmen; they appeal to people through warm or funny mnemonics.

The first volume, Meet Mr. Product, focuses on the late 1940s through the 1950s.The new Mr. Product covers 1960 to 1985, when portable transistor radios and television ushered in commercials with cartoon spokescharacters. These charming and ingratiating figures help consumers identify and trust brand names. For example, Tony the Tiger’s “they’re grrrrrrrreat” isn’t just a pitch for cereal—it’s also an enduring slogan that has become part of the vernacular. Presidents, friends, and coworkers might change, but characters like Mrs. Butterworth and the Trix Rabbit are still around, Dotz says.

Courtesy of Warren Dotz

Courtesy of Warren Dotz “An advertising character, whether fictional or real, has a face,” he says. Those deliberately designed human features create empathy, and they become our friends. So while Kellogg’s has a recognizable logo on its products, that could never compete with the advantages of Tony the Tiger professing the greatness of Frosted Flakes or Toucan Sam promoting Froot Loops, Dotz says. On the same note, Procter & Gamble’s Mr. Clean may get the job done as well as its competitors, but the iconic Mr. Clean (along with humanoid shape of the bottle) gives the product a leg up.

Beyond the ubiquitous examples, the most curious and interesting characters happen to be the ones that weren’t bankrolled by major corporations. While these characters were perhaps less “filtered” or “focus-grouped,” they’ve gone on to become the overwhelming favorites of graphic designers and animators, Dotz says. Many are anthropomorphic and look like their names: Miss Fluffy Rice, Chokey the Smog Dog, Fiber Glass Man, Wiry Joe, and Sally Fasweet, among many others.

Courtesy of Warren Dotz Another group of less well-known but interesting characters were ones that were created when cowboys, secret agents, super heroes, beatniks, hillbillies, and astronauts were popular: Bond’s James Bread, the Man from Glad and Oster’s Super Pan. Even established characters like the Hush Puppies dog were sent into space, helmet and all.

Courtesy of Warren Dotz Another group of less well-known but interesting characters were ones that were created when cowboys, secret agents, super heroes, beatniks, hillbillies, and astronauts were popular: Bond’s James Bread, the Man from Glad and Oster’s Super Pan. Even established characters like the Hush Puppies dog were sent into space, helmet and all.  Courtesy of Warren Dotz

Courtesy of Warren Dotz The controversial ones might have been popular once, but they wouldn’t survive with today’s growing diversity and racial sensitivity. “Characters such as 3M’s Scotty McTape for Scotch tape and the Plaid Stamps girl are long gone,” Dotz says. “Frito Bandito and Funny Face drink’s Injun Orange and Chinese Cherry were some of the most immensely popular kid-centric ad characters that were eventually and unceremoniously retired due to complaints of stereotypical imagery.”

Consumers are much more aware today that advertising characters exist, on some level, to manipulate the consumer. However, even with all this savviness, these characters continue to entertain and charm.

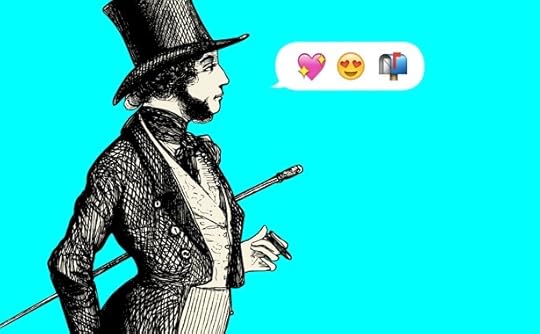

The (Re-)Invention of the Soul Mate

Humans, the playwright Aristophanes argued, once had four arms, four legs, and two faces. Our current, more streamlined look—current in ancient Greece, and current, still, today—came about because of pride. Those extra-ancient, multi-limbed humans had become arrogant, Aristophanes had it, and the gods, being gods, resented that. Zeus wanted vengeance. So he came up with a plan that was devious in its elegance: He would cut humans in half. This would, he figured, not only instantly double the number of people paying tribute to him; it would also create a kind of permanent humility, forcing humans into a sad state of severance: two bodies, one soul. Joined, but disconnected. Permanently incomplete.

After Zeus had done his work—he did the dividing, and Apollo helpfully sewed up the new creatures, with only the belly buttons remaining as evidence of the surgery—humans wandered the world a little bit lost, a little bit desperate. Sliced souls forever seeking their other halves.

* * *

Today, we don't necessarily think of soul mates in the Aristophenian kind of way, as an epic extension of the plot of the movie Face/Off. We do, however, tend to think of romantic partnerships with that same, ancient sense of bifurcated destiny. My “other half.” My “significant other.” Pretty much every song lyric ever written by Taylor Swift. Modern coupling, in much of the world, is about much more than mating; it’s about, on some level, soul mating. It’s about finding—and then keeping—the person who, in ways tiny and huge, completes you. As Phoebe Buffay summed it up: “He’s her lobster!”

Related Story

A Modern Guide to the Love Letter

I mention that because of Modern Romance, the new book written by the impish comedian Aziz Ansari (with an assist from the decidedly non-impish sociologist Eric Klinenberg)—which is nominally about the familiar vagaries of living and loving in the age of Tinder, but which is more broadly about the recent re-invention of the soul mate. It’s about the amazing and occasionally awkward things that take place when an entire culture, gradually but also suddenly, transforms its sense of what romance is all about.

It used to be, Ansari notes, that the thing that has traditionally brought cultural codification to the lobsterian ideal of mating-for-life—the institution of marriage—was mostly a matter of economic and social convenience. Marriage existed not just for reproduction, but for the encouragement of particular economic conditions: unions between families, partnerships that allowed for the efficient running of a household, etc. As Stephanie Coontz notes in Marriage, a History, the thing that today we tend to think about as the ending of the love story has historically had very little to do with romantic love: Until quite recently, marriage was simply about “creating conditions that made it possible to survive and reproduce.” It was, Ansari puts it, in a moment of Klinenberg-inflected seriousness, “too vital an economic and political institution to be entered into solely on the basis of something as irrational as love.”

All that, of course, has changed dramatically—and very, very quickly. “When the older folks I interviewed described the reasons they dated, got engaged to, and then married their eventual spouses,” Ansari writes, “they’d say things like, ‘He seemed like a pretty good guy,’ ‘She was a nice girl,’ ‘He had a good job,’ and ‘She had access to doughnuts and I like doughnuts.’” On the other hand: “When you ask people today why they married someone, the answers are much more dramatic and loving. You hear things along the lines of ‘She is my other half,’ and ‘I can't imagine experiencing the joys of life without him by my side,’ or ‘Every time I touch her hair, I get a huge boner.’”

We live, in other words, in a world that is shaped, in ways big and small, by the search for a soul mate. “Younger generations face immense pressure to find the ‘perfect person,’” Ansari notes—a pressure that “simply didn't exist in the past when ‘good enough’ was good enough.” Emerging adulthood, the phase of life between adolescence and marriage (and a phase that didn’t exist for most previous generations of Americans), now doubles as a time when many young people embark not just on a professional career, but on a romantic one. In the 1960s, 76 percent of college-aged women and 35 percent of college-aged men said they'd be willing to marry someone they didn't love. In a similar study conducted in the early 1990s, 91 percent of women and 87 percent of men said they wouldn't marry someone unless they were in love with them.

“Younger generations face immense pressure to find the ‘perfect person,’” Ansari notes—a pressure that “simply didn't exist in the past when ‘good enough’ was good enough.”Love has, accordingly, become a pursuit—something we look for and fight for and treat as a fundamental component of a happy and successful life. It’s the “organization kid” ethos, essentially, applied to romantic partnership, and it complicates the dominant, idyllic sense of love as the stuff of Shelley and Shakespeare, as the thing—that warm, soft, trembling thing—that transcends culture and gender and race and class and age and defines, in ways both big and small, what it means to be human.

Lol! From the anthropological perspective, instead, romance is simply a cultural assumption like anything else. And marriage, that symbol of success in one’s search for a soul mate, has become a status symbol—and also, Ansari notes, summoning Esther Perel, a luxury good.

That transformation—the result of, among many other things, the industrial revolution/the women's movement/a good economy/a bad one—has been, in the last couple of decades, complemented by another kind of revolution: the transformation in communications brought about by the Internet. There's the rise of texting, and the related decline of email/phone calls/letter-writing. There's the invention of Match and JDate and Farmers Only and eHarmony and OkCupid and Hinge and Grindr and Tinder, and all those services’ attendant possibilities and paradoxes of choice. Our communications are newly instant and newly distant, and that shift is changing not just the culture at large, but also the way we approach the sparking and the maintenance of relationships.

None of which, as Modern Romance presents it, is a revelation. The stuff explored in the book—the gender differences in approaches to online dating, the social effects of friends-with-benefits-ing, the psychological impact of a swipe-right economy—will feel familiar to anyone who reads magazines and/or is currently single. Ansari quotes all the experts (Michael Rosenfeld, Sherry Turkle, Natasha Schüll, Helen Fisher, Barry Schwartz) you’d expect to be quoted in a book like this. He cites exactly the research you’d expect to be cited. He sums it all up charmingly and winkily and am I rightily, with the same light snark he deploys in his standup. (Telling the story of Tim, an older gentleman who asked his future wife on a date in person, right after meeting her, Ansari points out: “That sounds infinitely cooler than texting back and forth with a girl for two weeks only to have her flake on a Sugar Ray concert.”)

The commonly accepted rules that used to direct coupling—wait three days to call, etc.—have largely been rendered obsolete.Modern Romance reads like a CliffsNotes to relationshipping as it is currently experienced by (mostly middle-class, Ansari admits, and mostly straight) Americans. It’s the familiar stuff of research and sitcomedy, distilled into a funny, and highly readable, summary.

And while Modern Romance’s revelations aren’t terribly revelatory, their telling is refreshing in an important way: They’re humanized. They operate at the scale of everyday life and everyday experience and everyday emotion. Too often, the data experts have gathered about the nebulous thing that is “modern romance” is presented precisely as that: data. We can read Christian Rudder's Dataclysm, about the way the Internet is affecting how people meet and date, or Eric Klinenberg’s Going Solo, or Michael Rosenfeld’s “How Couples Meet and Stay Together”; what those projects can gloss over, though, are the small joys and also the crushing existential anxieties that the new romantic order can provoke in its participants. The “…” that appears during a text exchange, suspending a conversation—and, sometimes, an entire relationship—in a wave of hidden characters. The sexting. The emoji-decoding. The LOL-sharing. The game-playing. The fact that the commonly accepted rules that had crystallized around the technologies that used to direct coupling—wait three days to call, etc.—have largely been rendered obsolete.

The fact that everyone, as a result, is a little bit confused, and a little bit overwhelmed, and a little bit convinced that that last text went unanswered because its recipient was obviously abducted/involved in a terrible accident/convinced to join a doomsday cult that requires its members to cancel their phone service.

Ansari, in the book, tells the story of his dealings with Tanya, a friend of his whom he was interested in in a more-than-a-friend kind of way. They hook up one night. He texts her the next day—a good, sweet text, offering just the right balance of “I’m casual” and “I care.” A few minutes after sending the message, he sees its read receipt. He sees the “…”: She’s replying! Yay! And then, right after they started—the dots go away. Minutes pass. Then hours. Then days. He never hears from her again (well, not until much, much later). All the things that could have been—the sweet little discoveries, the dumb little in-jokes, the brunches, the babies, the nights spent on the couch doing nothing but being together, the merged families and furniture and lives—disappear in the blink of a “...”

To deal with “the awful frustration, self-doubt, and rage that this whole ‘silence’ nonsense had provoked in the depths of my being,” Ansari goes to a comedy club. He does a set. He tells everyone about Tanya. He gets laughs. But he also gets, he notes, “something bigger, like the audience and I were connecting on a deeper level.” They understand, together, what it feels like—for better, for worse—to soul-mate. They understood what it means to be looking, with the help of phones and friends and the march of human progress, for one’s lobster.

“I could tell that every guy and girl in the audience had had their own Tanya in their phone at one point or another,” Ansari writes, “each with their own individual problems and dilemmas. We each sit alone, staring at this black screen with a whole range of emotions. But in a strange way, we are all doing it together, and we should take solace in the fact that no one has a clue what’s going on.”

June 17, 2015

A Gunman Strikes a Black Church in Charleston

A gunman in Charleston, South Carolina opened fire Wednesday night at a weekly Bible study at a local black church, killing nine people and wounding at least one other. “I do believe this was a hate crime,” said Charleston Police Chief Greg Mullen.

One of the victims is Clementa Pinckney, a South Carolina state senator and Methodist pastor at the church, according to NBC News. Charleston police described the suspected attacker as a clean-shaven white man about 21 years old, with sandy blond hair, clad in a grey sweatshirt and jeans. He is not currently in custody. The gunman struck during a weekly Wednesday Bible study, with families and children present.

“This is a tragedy that no community should have to experience,” Mullen said. He warned that the perpetrator “is extremely dangerous,” but vowed to “bring him to justice.” He added that the FBI was aiding in the investigation, and that additional resources were being flown in from Washington, D.C.

“I will say that this is an unspeakable and heartbreaking tragedy in this most historic church, an evil and hateful person took the lives of citizens who had come to worship and pray together,” Charleston Mayor Joe Riley told reporters, according to the Post and Courier. Locals gathered in the streets surrounding the church in an impromptu prayer session for the shooting victims.

South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley issued her condolences after news of the shooting broke. “While we do not yet know all of the details, we do know that we’ll never understand what motivates anyone to enter one of our places of worship and take the life of another,” she said in a statement.

The gunman’s attack targeted the oldest black church south of Baltimore, and one of the most storied black congregations in the United States. Emanuel A.M.E. Church’s history is deeply intertwined with the history of African American life in Charleston. Among the congregation’s founders was Denmark Vesey, a former slave who was executed in 1822 for attempting to organize a massive slave revolt in antebellum South Carolina. White South Carolinians burned the church to the ground in response to the thwarted uprising; along with other black churches, it was shuttered by the city in 1834. The church reorganized in 1865, and soon acquired a new building designed by Robert Vesey, Denmark’s son; the current building was constructed in 1891. It has continued to play a leading role in the struggle for civil rights.

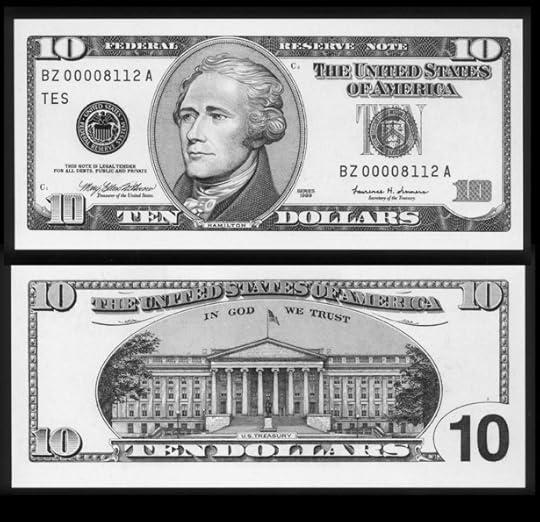

A Woman on the Sawbuck

On Wednesday, Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew made the surprise announcement that the $10 bill was getting an overhaul and that by 2020, the bill that features the first secretary of the treasury, Alexander Hamilton, would also feature a still to-be-named woman:

America’s currency is a way for our nation to make a statement about who we are and what we stand for. Our paper bills—and the images of great American leaders and symbols they depict—have long been a way for us to honor our past and express our values.

Lew also noted that the redesign coincides with the 100th anniversary of the passage of the 19th amendment, which granted women the right to vote.

The decision to remake the sawbuck may not necessarily knock Hamilton off the bill entirely. “There are many options for continuing to honor Hamilton,” read a statement on the Treasury website. “While one option is producing two bills, we are exploring a variety of possibilities.”

The last time the Treasury added a new face to a bill, it was Andrew Jackson’s, whose visage replaced that of Grover Cleveland on the $20 bill. It was also the $20 bill that seemed the most likely candidate to be resigned. Earlier this year, we noted the efforts by the group Women on 20s to replace Jackson, who cuts a controversial historical figure and hated paper currency, with a woman. (In a poll, Harriet Tubman edged out Eleanor Roosevelt as the winner.)

In April, as the initiative gained steam, Senator Jeanne Shaheen of New Hampshire introduced a (non-monetary) bill called the Women on the Twenty Act. Following Lew’s announcement, she declared half of a victory, “While it might not be the twenty-dollar bill, make no mistake, this is a historic announcement and a big step forward.”

Nevertheless, it does seem like an underwhelming choice. “The $10 bill is the third least-circulated among the seven major denominations, accounting for 5.2 percent of 36.4 billion notes in use at the end of last year,” Bloomberg noted. As Matt Phillips explained in The Atlantic in 2012, the $100 bill still dominates.

But Lew made clear that this just the first bill to be redesigned, as part of a comprehensive overhaul. “Democracy is the theme for the next redesigned series of U.S. notes,” he said. “Images that capture this theme will be featured on the next $10 bill, and on future bills.”

Game of Thrones and Sexual Violence

It’s a question that’s been asked of Game of Thrones as long as the HBO series has been on the air: Why so much sex and violence?

The question has been raised in different ways at different times. Early on, it principally focused on nudity and “sexposition”—the habit of featuring naked bodies (usually those of prostitutes) onscreen while a principal character enunciated some otherwise tedious plot details. (This was the era that spawned this famous SNL skit.)

Related Story

The Most Disturbing Thing About Game of Thrones' Most Disturbing Scene

More recently, and particularly over the course of the just-concluded fifth season (our Atlantic roundtable on the finale is here), the question has evolved into a more pointed one: Why does the show feature so much sexual violence—most, though not all, directed at women and even young girls?

Obviously part of the answer is that there’s a lot of sexual violence in A Song of Ice and Fire, the series of George R. R. Martin novels on which Game of Thrones is based. Martin has said himself that that though his books are fantasy fiction, one of his intentions has been to convey an accurately medieval sense of how the powerful prey upon the powerless, including men preying on women.

It’s worth noting that in condensing Martin’s work for the screen, showrunners David Benioff and D.B. Weiss have on occasion pared down or cut altogether instances of sexual abuse. Moreover, the books are much longer than the show and many of the horrors that take place in them—sexual and otherwise—are essential to the narrative. So when condensing their source material, Benioff and Weiss have had little choice but to increase the overall ratio of horror: Two gruesome events separated by hundreds of book pages detailing wedding feasts and noble sigils might, through the simple act of compression, find themselves onscreen in consecutive episodes—or even the same one. Finally, video is simply a “hotter,” more immediate medium than the printed word. Witnessing atrocities is inevitably a different experience from having them described on the page. (Former roundtabler Ross Douthat wrote about this a few weeks ago.)

All caveats aside, however, it’s also true that Benioff and Weiss have gone out of their way, time and time again, to ramp up the sexual violence well beyond their source material. New characters have been invented in order to become victims (or victimizers), and existing ones have had their sexual cruelty amplified. The following is a list of relevant examples—one that is in all likelihood not comprehensive. Readers are welcome to note other examples (and, of course, counterexamples) in comments.

Ros. A prostitute working for Littlefinger (who would later become his business partner), Ros was a character invented for the show and, for a while, a principal participant in the show’s sexpository moments. But in season three, after she crossed Littlefinger, he gave her to the sadistic boy-King Joffrey, who tied her up and shot her naked body full of crossbow bolts—including two in her groin and one between her breasts. (Whether that was the full extent of his defilements was left to the imagination.) Did this scene convey that Littlefinger was not a man to be crossed? Yes, it did. But it’s not difficult to imagine many less sexualized ways in which this might have been accomplished.

Joffrey. The Joffrey Baratheon of the books was, like that of the show, a petulant, murderous little monster. But on at least two occasions, the show went far out of its way to explicitly sexualize his malice. The first was a scene, not in the books, in season two, in which rather than sleep with the prostitutes Littlefinger had sent for his amusement, he had one (Ros) violently abuse the other with his royal scepter. Was the scene necessary to establish Joffrey’s sadism? Well, no, given that in the same episode we had already watched him have Sansa Stark stripped and beaten by his Kingsguard. The second example of the show going to extraordinary lengths to tell us something we already knew about Joffrey was, of course, the aforementioned torture-murder of Ros.

New characters have been invented in order to become victims (or victimizers), and existing ones have had their sexual cruelty amplified.Talisa. In the books, noble, doomed Robb Stark betrayed his vow to marry a daughter of Walder Frey’s by sleeping with a tertiary character named Jeyne Westerling, a young noblewoman who’d tended his wounds. On the show, Jeyne was replaced by Talisa Maegyr, a vastly more prominent character. A smart, capable battlefield nurse and Volantene beauty, Talisa gradually won Robb’s heart, married him, and conceived his child. There are some interesting things that Benioff and Weiss might have done with this role (ahem, Lannister honeypot); instead they just turned her into more grisly fodder for the Red Wedding, the camera focusing very particularly on the repeated stabbing of her pregnant belly. To what end? Because otherwise the massacre of Robb, his mother, and his entire army would not have been an unhappy enough development? Like Ros, Talisa seems to have been created in large part to be brutally murdered in a manner particular to her anatomy.

Ramsay Snow/Bolton. Among the more substantial alterations between page and screen has been the ascendance of the Bastard of Bolton as a central figure on the show. Though he played an important narrative role in the second of Martin’s novels—it was he who tempted Theon Greyjoy to child-murder—he was left out of the second season of the show. In the third book, by contrast, he was a distant, off-screen character about whom awful things were heard, and from whom care packages containing pieces of Theon were occasionally received. It was at this point, however, that Benioff and Weiss decided Ramsay merited ample screen time, dramatizing at interminable length his torture and eventual castration of Theon. Especially notable was a scene in which two naked beauties (one of them Myranda—see below) arrived to sexually arouse Theon in preparation for his gelding. Since then, the show has taken every conceivable opportunity to remind viewers that Ramsay is a violent sexual sadist. To pick two examples of many, there was the murder (with Myranda) of former bedwarmer Tansy, who was hunted through the woods, shot with an arrow, and then eaten alive by Ramsay’s dogs in season four; and the rape of Sansa at Winterfell this last season. (More on the latter in a moment.)

The show has taken every conceivable opportunity to remind viewers that Ramsay is a violent sexual sadist.Myranda. Seen only briefly in seasons three and four, Myranda became a regular, if minor, character in season five. She did not exist in the books (though she had some attributes in common with the “Bastard’s Boys” who occasionally participated in Ramsay’s abuses). Myranda’s role is essentially limited to a) having rough sex with Ramsay; b) assisting Ramsay in his violent depredations; c) being threatened by Ramsay when she suggested that she, like he, might marry; and d) making graphic promises of sexual torture and mutilation toward Sansa, the latter of which got her pushed off the Winterfell ramparts to her death. In short, her sole purpose was to make Ramsay even worse, principally as an eager accomplice but also as a potential future victim.

The mutineers at Craster’s Keep. Another example of Benioff and Weiss taking something implicit in the books and making it all-too-thoroughly explicit. The mutiny itself proceeded along similar lines to Martin’s source material (in which it was also clear that the mutineers went on to rape Craster’s wives). But the capture of Bran, Jojen, and Meera, and the commando raid by Jon Snow were storylines added by Benioff and Weiss. And, of course, they offered the opportunity to invent yet another sexual psychopath—Karl, based on a miniscule character in the book—and to dramatize onscreen the rape of one of Craster’s wives and the near-rape of Meera.

Cersei and Jaime in the Sept of Baelor. This example of Benioff and Weiss tweaking Martin’s material in order to make it more sexually violent differs from the others in that by all accounts it was essentially a mistake. In the book, Cersei kissed Jaime lightly, he returned the kiss lustily, she briefly pushed back at him out of fear they might be discovered, and then she quickly succumbed to lust herself, begging him to complete the act. It was a horrible scene—two twins having sex over the corpse of their dead son—but the sex itself was consensual. In their customary way, when adapting the scene for television (for last year’s “Breaker of Chains” episode), Benioff and Weiss seem to have decided to make the scene 20 percent more awful, with Cersei resisting more aggressively and never giving any meaningful form of consent. But that 20 percent changed everything: Suddenly, Jaime—by that point one of the most sympathetic characters on the show—was a rapist. Subsequent comments by the director and performers made pretty clear that this was not the intent of the scene. But one can easily make the case that this makes it even worse. If, as artists, you want to truck in images of sexual violence, you ought to be very aware of exactly what it is you’re doing. An “accidental” rape scene is arguably a worse indictment than a deliberate one.

An “accidental” rape scene is arguably a worse indictment than a deliberate one.Sansa. In the books, to secure the Bolton hold on the North, Ramsay married a minor character named Jeyne Poole, who was impersonating Arya Stark. To no one’s surprise, he abused her horribly (though, as with Theon, principally “offscreen”). To streamline the plot and increase the emotional stakes, Benioff and Weiss chose to replace Jeyne with Sansa—which was, overall, an excellent idea. But any viewer of the show was acutely aware of the danger to Sansa without needing to watch Ramsay’s wedding-night rape. Indeed, it didn’t need to happen at all: a creepy, earlier scene in which Ramsay forced Theon to apologize over dinner was more than successful in establishing the stakes. The rape and subsequent descriptions of abuse were not only unnecessary but redundant twice over. We were already well aware that Ramsay was a sexual sadist, and we’d already watched Sansa get abused by another one during her engagement to Joffrey.

Ser Meryn Trant. Ser Meryn was a bad guy. We knew this. He killed Arya’s fencing master, Syrio Forel, and beat Sansa on more than one occasion at Joffrey’s command. But Benioff and Weiss felt they had to make him a badder guy. And the inevitable way they accomplished this was to invent a wildly unnecessary storyline revealing him to also be a man who beats and rapes underage girls. The subsequent “Ramsay Lite” torture that Arya meted out upon him only compounded the ugliness.

(Note: The sacrifice of Shireen and Cersei’s walk of atonement may both have been horrible moments, but for a variety of reasons neither belongs on this particular list.)

Are Benioff and Weiss cynically ramping up the sexual violence because they think it’s good for ratings? Are they just blasé and careless when it comes to the subject? Or do they feel that by rendering Martin’s material even more extreme they are somehow increasing its moral heft? Regular readers will know that I tend to believe that it is some combination of the first two explanations. But whatever the case, it’s a pattern so ingrained that it seems unlikely to change. Given this history, viewers should brace themselves for the worst in season six.

The Earth's Evaporating Aquifers

Many—if not most—of the Earth’s aquifers are in trouble.

That’s the finding of a group of NASA scientists, who published their study of global groundwater this week in the journal Water Resources Research. Water levels in 21 of the world’s 37 largest known aquifers, they report, are trending negative.

The study is the first major accounting of groundwater change over time on the planetary scale. It was accomplished, not with wells or surveys, but with satellites.

Groundwater reserves are one of the environmental phenomena that’s hardest to conceptualize. Droughts are systemic and complex, sure, but a curious person can always go stand in a reservoir and see where the water is supposed to be. Dry lawns and fallow fields present another view on to what a drought is. But aquifers remain hidden, hard to measure, hard even to imagine: What does it mean that, beneath much of the United States, there are invisible seas full of drinkable freshwater? How can we think usefully about both their vastness and their finitude?

Already, 2 billion people worldwide rely on groundwater for daily use. That will have slosh over effects: A 2012 study reported that water from aquifers, moved to the surface by human activity like farming and mining, would constitute 25 percent of sea level rise before 2050, and possibly even more after that. Relocated groundwater, by that paper’s estimate, would be the third-most significant cause of sea level rise this century, after the melting ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland.

In the study released on Tuesday, researchers found that eight aquifers—particularly those in arid climates—were dangerously overstressed. Eleven major aquifers were “negatively recharging,” meaning people were pumping water out of them much faster than they were putting it in. “The water table is dropping all over the world,” Jay Famiglietti, a water researcher at NASA and one of the authors of the study, told The Washington Post. “There’s not an infinite supply of water.”

This study notably only allowed scientists to measure how aquifers were changing, not how big they are. But its methods seem to offer significant improvements on previous techniques.

Earlier groundwater research occurred by a sort of census. Government or independent researchers collect data about how people are accessing an aquifier—how deep they’re drilling, how much water they’re pumping, and how quickly they’re extracting it. They then combine this figure with other calculations about the size and depth of the aquifier to arrive at an estimate of its health.

The satellites in the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment—nicknamed GRACE—works by a different method: It observes the mass of water beneath the ground. The two satellites in GRACE chase each other across orbit, measuring their distance from each other. When they pass over something with more gravity—like a continent—the front satellite accelerates away from its partner. By measuring these accelerations, scientists can measure and estimate the planet’s gravity and heaviest regions. They can then estimate the presence of large, massy agglomerations—such as the underwater seas that are aquifers—that can’t otherwise be observed.

The two GRACE satellites launched in 2002, and their own methods have improved over time. Last year, NASA researchers found they could better measure groundwater by comparing GRACE’s findings to irrigation records, rather than by estimating the amount of water in the soil from climate records.

GRACE’s findings sometimes differed wildly from those on the ground. The study’s authors say that the aquifer beneath California’s Central Valley is in better shape than statistics would indicate. The aquifer beneath Democratic Republic of Congo, meanwhile, appears to be in considerably worse shape, losing water at least three times as quickly as statistics would estimate, the study says.

The sum of all these findings is that we’ll soon have to start treating and monitoring global groundwater with the same precision we track aboveground reservoirs. And last week, California took its first serious steps in that regard, issuing major regulations limiting how farmers could use water from the Central Valley aquifer. The mandate remains to treat groundwater—hard as it is to imagine—as the finite resource that it is.

California's Stand on Behalf of Uber Drivers

Bad news for Uber: On Tuesday, the California Labor Commission filed documents ruling that a driver for the popular ride-sharing company—which was recently rumored to have a $50 billion valuation—is an employee, not an independent contractor, a decision that could mean big changes for the way the company, and their competitors, run their businesses.

The commission ordered that the company pay the plaintiff, former driver Barbara Ann Berwick, a total of $4,152—most of which is reimbursement for business expenses incurred while driving for Uber.

The claim that Uber and other sharing-economy businesses have made to defend their use of contractors is that they are in the business of technology and logistics, finding more efficient ways to connect independent suppliers with those who demand services. The companies argue that workers, (in this case drivers), provide their own supplies (cars), make their own schedules, and have the freedom to pick up work when they want—provisions that would allow them to be classified as independent workers.

But critics have said that such explanations are flimsy at best, manipulative and illegal at worst—denying workers who provide the core functions of these businesses basic labor rights like workers comp, should they get hurt on the job, minimum wage, payment of payroll taxes, access to unemployment benefits, or the ability to unionize.

According to the ruling:

Plaintiff’s work was integral to Defendants’ business. Defendants are in business to provide transportation services to passengers. Plaintiff did the actual transporting of those passengers. Without drivers such as Plaintiff, Defendants’ business would not exist.

The decision in favor of labeling drivers as employees also focused largely on the concept of who really controlled the drivers’ ability to work.

Plantiff’s car and her labor were her only assets. Plaintiff’s work did not entail any “managerial” skills that could affect profit or loss. Aside from her car, Plaintiff had no investment in the business. Defendants provided the iPhone application, which was essential to the work. But for Defendants’ intellectual property, Plaintiff would not have been able to perform the work. In light of the above, Plaintiff was Defendants’ employee.

This decision could have serious ramifications for the company’s business model, since the cost of doing business would increase significantly if Uber is forced to pay for everything from benefits to payroll taxes for more workers. But for now, the ruling only affects a California driver, and not the company’s estimated million plus drivers around the globe. Uber is also appealing the judgment.

Related Story

In the Sharing Economy, No One's an Employee

Sam Estreicher, a professor of labor and employment law at NYU School of Law says that while the ruling is important, the fate of Uber and other ride-sharing companies and their contractors and employees may be decided more slowly, on a state-by-state basis, and hinge heavily on the interpretation of labor laws within those jurisdictions. In some places that may mean finding a midway point between employee classification and the current policy, which largely absolves the company of responsibility for its drivers. Estreicher says that beefed up regulations that bring the companies into compliance with similar, non-sharing-economy companies in each state might be a plausible solution. “Regulations that apply to local transportation companies don't apply to these guys. That can’t be the case, but that doesn't mean that the drivers are their employees,” he says. “They are gonna have to agree to a bunch of safety and consumer regulations that the existing businesses are subjected to.”

It’s also possible that the question of how to label sharing-economy drivers will eventually be reviewed under existing federal law, says Jeff Kirk, a legal analyst who has studied ground transportation. “Whether or not taxi-like drivers are independent contractors or employees is already well established as a matter of federal law,” Kirk says. “I think, in the end, this will end up being adjudicated in federal, not state court, and assuming the courts follow existing precedent, they will decide that Uber drivers are independent contractors.”

Still the labor commission's decision, especially if it holds up through appeals, has significance, especially as more and more companies rely on the on-demand workforce, says Arun Sundararajan, a professor at NYU’s Stern School of Business who studies technology’s impact on businesses. Prices of services provided by companies in the sharing economy would likely increase. Uber and Lyft would not only survive but continue to thrive, while smaller companies with less revenue to cover the additional exepnse, would likely find that their business models are no longer viable, Sundarajan said in an email.

“[The case] is drawing attention to a critical challenge we face over the next decade: to create a new social safety net as employment is unbundled and our workforce becomes largely freelance,” said Sundarajan. “In the U.S., we have created a safety net that relies heavily on full-time employment. Rather than forcing full-time employment on on-demand work firms, we should instead pursue a policy direction that creates a comparable safety net for workers who are not full-time employees.”

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower