Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 411

June 17, 2015

Violence Has Forced 50 Million People From Their Homes

War reporting tends to capture the devastation of buildings and the casualties of battle, but it’s harder to visualize the effect of conflict on those who aren’t killed or enlisted to fight. Even sweeping vistas of tent cities set up at dusty border crossings don’t seem to convey the scale of destruction.

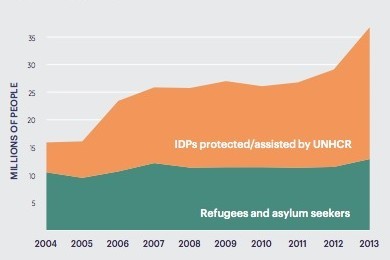

Numbers can go a long way toward filling that gap. For example: According to the annual Global Peace Index report, released on Wednesday, there are more than 50 million refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs) around the globe right now. Put another way, that’s one in every 133 people worldwide and 0.75 percent of the world population. Put yet another way, that’s roughly the equivalent of the entire population of South Korea being pushed out of their homes, or as if the combined populations of Australia and Taiwan had to leave.

Not since World War II have there been so many refugees or IDPs. (Finding definitive numbers is tough, but the UN reports that the number of refugees and IDPs last exceeded 50 million during the Second World War, an astonishing figure given that the global population was significantly smaller then.) Most of the growth now is actually not from refugees—that number has grown a comparatively scant 23 percent in a decade—but among IDPs, or those uprooted within their home country, whose ranks have swelled by more than 300 percent since 2004.

Total Refugees and Internally Displaced People, 2004-2013

UNCHR via IEP

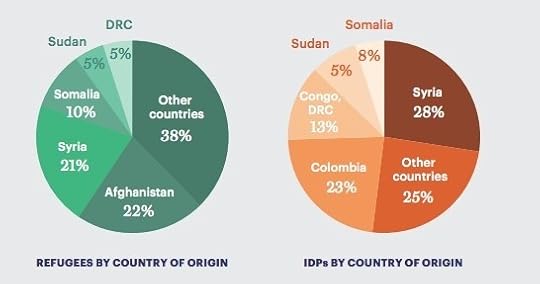

UNCHR via IEP Unsurprisingly, many of these people are concentrated in the Middle East and in particular in Iraq and Syria, where ISIS’s advance and the Syrian civil war have driven many people from their homes. A third of the world’s refugees come from those two nations alone. More than 9.5 million Syrians, or 43 percent of the Syrian population, are currently displaced. Last year, Uri Friedman dug deeper into displacement in Syria; Alan Taylor this week compiled a powerful gallery of Syrians attempting to get over the Turkish border and escape ISIS fighters.

Somewhat more surprising, given the comparative lack of attention, is the share of IDPs in Colombia, where people have been forced to move due to the government’s battle with the leftist Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC.

Refugees and IDPs by Country of Origin

UNCHR via IEP

UNCHR via IEP The Global Peace Index, produced by the Australia-based Institute for Economics and Peace, places the numbers in a broader context of conflict. If it seems like the world is getting more violent at the moment, that’s not just an illusion—the index’s metrics suggest that the world has become less peaceful over the last eight years, after a sustained period of improved stability after the Cold War.

This mass movement of people has a huge monetary cost. Economic activity stalls in the locations from which people flee; displaced people often lose most of what they possess and have trouble earning money; and someone has to pay to help feed and shelter them wherever they end up. The annual cost of this displacement, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, has now reached almost $100 billion.

But the most important effects are probably hidden far in the future. Studies have documented the deep and long-lasting effects that war and migration have on mental health. And World War II led to huge cultural changes across the globe, from the elimination of centuries-old ways of living to an intellectual efflorescence in the United States spurred in part by European Jewish refugees. While it’s impossible to predict what changes today’s surge of refugees and IDPs will set in motion, it’s fair to assume the reverberations will extend far beyond the Middle East.

How the Upstart Warriors Went All the Way

Even when an outcome is expected, it can still manage to be surprising. When the Golden State Warriors beat the Cleveland Cavaliers on Tuesday night to win the NBA title, it should have seemed like a formality. After all, the team cruised through the season, amassing the third-most wins in league history and breaking records with Stephen Curry, the NBA’s most valuable player, at the helm.

Related Story

How NBA Teams Campaign for Their MVP Candidates

Nevertheless, there was something odd about watching the team storm the court after the final buzzer. Few had predicted the Warriors would win a title this year, much less cement the team in the pantheon of all-time greats.

There were plenty of reasons to doubt the Warriors. Curry, their undisputed leader, has a history of injuries. Then there’s the persistent myth of jump-shooting teams—the veritable definition of the Warriors’ offensive style—failing to win championships. Playing a number of their games at late hours on the West Coast, the Warriors literally couldn’t be seen to be believed by many viewers across the country.

Then there was the opposition: the formidable Western Conference with its dynastic Spurs, towering Rockets, and flashy Clippers. To win the title, the Warriors had to defeat LeBron James, the world’s best player, who was making his fifth consecutive NBA Finals appearance. Meanwhile, not a single player on the Warriors’ roster had ever played in the Finals—it was the first time a team with no experience in the championship round had won a title since Michael Jordan and the 1991 Chicago Bulls. The Warriors also pulled it off while being led by Steve Kerr, a coach in his first year with the team.

For a few moments, particularly after the Cavaliers went up 2-1 in the series, it looked as if experience would win out. But the Warriors, already stocked with both chemistry and talent, ultimately came back because their roster was also deep.

The difference wasn’t a combustible scorer like Curry or a shutdown defender like Draymond Green, but rather a bench player, Andre Iguodala, who became the first player

An American Kidnapping

I took some time this weekend to re-read Jennifer Gonnerman’s piece on the odyssey of Kalief Browder. I wanted to understand how, precisely, it happened that a boy was snatched off the streets of New York, repeatedly beaten, and subjected to the torture of solitary confinement, and yet no one was held accountable. To understand this question is to journey into a world of legal-speak and phraseology all of which, in the case of Browder, allows what we would normally label thuggery to mask itself under the banner of law. Browder was supposed to be held no longer than six months. But as Gonnerman explains, poor people and the courts do not use the same clocks:

Many states have so-called speedy-trial laws, which require trials to start within a certain time frame. New York State’s version is slightly different, and is known as the “ready rule.” This rule stipulates that all felony cases (except homicides) must be ready for trial within six months of arraignment, or else the charges can be dismissed. In practice, however, this time limit is subject to technicalities. The clock stops for many reasons—for example, when defense attorneys submit motions before trial—so that the amount of time that is officially held to have elapsed can be wildly different from the amount of time that really has. In 2011, seventy-four per cent of felony cases in the Bronx were older than six months.

In the case of Browder, the clock stopped for all sorts of reasons. In one instance a prosecutor claimed he was not ready because of “conflicts in my schedule.” In the other the excuse was jury duty. Another time the prosecutor was on vacation. In the meantime the courts repeatedly tried to exact a guilty plea from Browder—at first offering him three and half years (he was facing fifteen) and eventually offering him time served. Browder refused each time. From Gonnerman’s article, it seems Browder refused on principle, but there were also practical reasons for Browder to refuse. In New York, black men with criminal records represent an untouchable class in the job market. Accepting a guilty plea would not merely have been a symbolic act for Browder, but one with damaging long-term consequences. And Browder could take no comfort in the fact of having been a juvenile at the time of the alleged crime. Taking a guilty plea would not have been a harmless act. For Browder it would have meant being branded as a criminal at the very start of his adult life, which would forever injure his attempts to make a living.

This threat to Browder’s life was birthed by the era of Willie Hortons, three strikes, and super-predators. Bragging about how many people you didn’t jail has, only recently, become supportable politics. It remains to be seen how well it shall endure. The politics which entangled Browder were of another era, the era of the Rockefeller Drug Laws. Those politics were not private, but public. It was through the urging, ascent, and endorsement of the public that mass incarceration was born. Kalief Browder’s case was entitled The People v. Kalief Browder not Despotic Autocrat v. Kalief Browder. The People themselves elected the politicians that saw no problem with Rikers, or with all the other Rikers across America.

There are some unavoidable conclusions in this. At our implicit behest, a boy was snatched off the streets of New York. His parents were told to pay a certain sum, or he would not be released. When they did not pay, he was beaten and then banished to lonely cell. Browder’s captors then offered him a different way out—pay for your freedom in the political currency of a guilty plea. He refused. More beatings. More solitary. The sum was lowered. Browder still refused. He was subjected to the same routine. Browder defeated his captors. They tired, released him, and likely turned to perpetrate the same scheme on some other hapless soul.

Browder’s victory came at the cost of martyrdom, and in his name we should be strong enough to speak directly about what he endured. Kalief Browder was kidnapped in our name. Kalief Browder was held for ransom in our name. Kalief Browder was tortured in our name. Kalief Browder was killed in our name.

Let us not pretend that this kidnapping scheme gone awry was somehow moral, or tolerable, just because it was lawful. Let us not accept the notion that our laws are simply sanctification—an expensive tuxedo for base criminality. And let us not pretend that Browder’s death was imposed on us from above. Americans are living in the America that we wanted; New Yorkers are living in the New York that we wanted. This must be accepted. If Americans are not responsible for what happened to Kalief Browder, for the ransoming of children, then we are not responsible for ensuring that it never happens again

By some cosmic coincidence we are confronted with the death of Kalief Browder at exactly the moment American media is obsessing over the life of Rachel Dolezal. Coincidental as it may be, it is also instructive. Through duplicitous means, Dolezal was able to masquerade as a member of the black race. Such masquerades are neither novel nor original. What fuels the fascination is the way in which it taps into one of America’s greatest and most essential crimes—the centuries of plunder which birthed the hierarchy which we now euphemistically call “race.”

Kalief Browder died, like Renisha McBride died, like Tamir Rice died, because they were born and boxed into the lowest cavity of that hierarchy. If not for those deaths, if not for the taking of young boys off the streets of New York, and the pinning of young girls on the lawns of McKinney, Texas, the debate over Rachel Dolezal’s masquerade would wither and blow away, because it would have no real import nor meaning. It is the killing of John Crawford III and the beating of Marlene Pinnock which elevates this charade beyond what Jeb Bush calls himself or what Elizabeth Warren called herself.

“I think race is oppression,” writes Richard Seymour, “and nothing else.” Indeed. It is the oppression that matters. In that sense, I care not one iota what Rachel Dolezal does nor what she needs to label herself. I care solely, totally, and completely about what this society does to my son, because of its need to label him.

How Apple and IBM Marketed the First Personal Computers

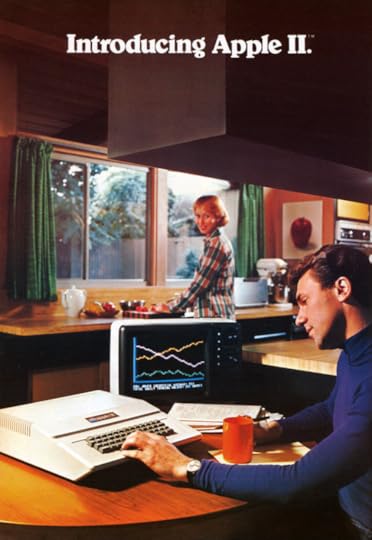

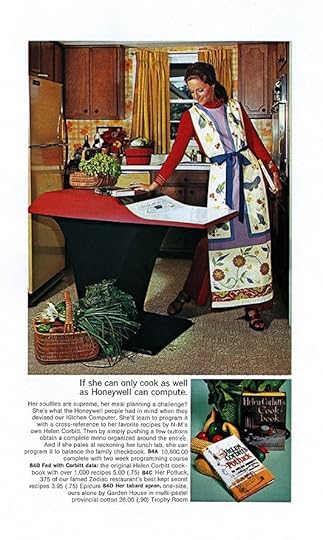

As ubiquitous as they might be now, in the 1970s, few things were more mysterious and unknown than the “personal computer.” For years, these shadowy, ever-shrinking machines had been touted as the next revolution in the American home, although few people had a sense of how they might actually work. In April 1977, that changed with the launch of the Apple II, one of the first affordable, mass-produced PCs in history. Here was a machine small enough to fit in the home and intuitive enough to use without a programming degree. Still, the advertising challenge—how to convince people to shell out for a product no home had ever needed before—was daunting. The best answer was the simplest one: make it seem like they'd always been there.

Apple ads offered straightforward, striking imagery, emphasizing clarity rather than elaborate claims on behalf of its wares—an approach it maintains to this day. In this full-page spread, a husband and wife enjoy their normal daily routine in the kitchen, with the husband tapping away on his Apple II. Forget the numerous wires and cables that would be tangling up the floor, or the limited household applications of such a device. This was the first time a computer could look seamless in the home, and that was what Apple, and each of its competitors, wanted.

How marketing defined and influenced an era

How marketing defined and influenced an eraRead More

Today, Apple makes a habit of stripping its advertising of everything but the most essential details to let the product speak for itself. In 1977, there was still much that needed explaining. The Apple II “home” ad came with a facing page describing, in detail, all of its technical specs and practical programs. Here was a machine that could teach your children spelling and arithmetic, “paint” dazzling displays using color graphics, and balance your checkbook. And unlike any machine before it, the Apple II wasn't a “kit”—a computer the customer had to assemble herself from purchased parts. Here was a machine you could set up in moments, even if the ad's opening lines might sound like a daunting amount of work to the iPhone generation: “Clear the kitchen table. Bring in the color TV. Plug in your new Apple II, and connect any standard cassette recorder. Now you're ready for an evening of discovery.”

The idea of clearing off the kitchen table had strangely recurred in the computer market for years prior. At the start of the ‘70s, Honeywell marketed an item called the “Kitchen Computer,” a desk-sized recipe book that would supposedly make the housewife's job easier. This regressive piece of advertising marked a curious landmark (published in the Neiman Marcus catalog, it was the first piece of personal-computer marketing in history), but the Kitchen Computer (retailing for $10,000) was essentially vaporware—a product that was announced, but never made. You would have needed to take a programming course to even figure out how to use the thing, and none were ever sold, but Honeywell was making a primitive effort at trying to understand how its product could figure into everyday life of Americans.

When Byte Magazine witnessed the Apple II in action before its launch, the publisher Carl Helmers wrote that it might be the first official “appliance computer”—a computer you could buy off the shelf, bring home, and plug in without much fuss. While PCs largely remained a luxury item, his prediction proved correct. Roughly 48,000 personal computers were sold worldwide in 1977; more than triple that amount shipped the next year. Companies rushed to an old trick: recruiting celebrities to endorse their products—the beloved science-fiction author Isaac Asimov became the face of Radio Shack, while Bill Cosby dubbed Texas Instruments’ Home Computer “the one” to buy. But while every home computer ad bragged about technical specs and affordability in big blocks of text, Apple more quickly understood that it was selling a way of life. This was something also grasped by its biggest competitor: IBM, the first giant in the American computer industry.

IBM didn’t officially enter the “personal” market until 1981, when it jump-started sales with the introduction of its much-copied IBM PC. But in the late ‘70s, it made the same strides toward emphasis on small size and ease of use, advertising its IBM 5100 (a predecessor to the PC) as the “first portable computer.” A 1977 TV commercial featured a real-estate manager, a farmer, and an insurance salesman, all of whom praised the machine as offering major relief on the job, and how easily it sat on a desk. “It weighs about 50 pounds,” the voice-over brags. If you still didn’t get the picture, a magazine ad made it simpler, with an image of someone holding it in his hands, as if carrying a box of files.

It would, in fact, take another generation before the home computer became much more than a hobbyist’s toy. Apple and IBM would lead the revolution, but not before the market weathered a 1983 video game bust that turned the public against buying such fancy toys. When prices came down, and programs became more practical, the idea of an Apple on the kitchen table became less and less fanciful. Apple’s innovations in the advertising sphere never lost their boldness, but through today the core aim remains the same: convincing the consumer that there’s a practical application for its latest high-end product. Just watch the TV advertising for the Apple Watch, derided by some tech critics as useless and inconvenient. Out and about? Exercising? Planning meetings at work? Talking to friends? Taking a picture? The watch is always seamlessly involved. Selling technology can’t only hinge on bragging about specs. Now, as it was in 1977, it’s about convincing the consumers that there’s a computer-sized hole in their lives that they never noticed before.

These 21 Republicans Voted Against a Torture Ban

The Senate approved an amendment Tuesday that would make it harder for future presidents to torture prisoners like the CIA did during the Bush Administration. As written, it “does not directly confront all the ways the CIA might try to circumvent U.S. torture rules,” Joshua Keating writes, “but it is an important step toward ensuring that the worst abuses committed by U.S. personnel after 9/11 won’t be repeated—even if those who did the torturing won’t be punished.”

Before the vote, I argued that it should be regarded as a moral test and a reaffirmation of a civilizational taboo. Now let’s take note of who passed that test and who failed it. The amendment passed 78 to 21. All 44 Democrats in the Senate voted for it.

Among Republicans, the amendment still won a majority, 32 to 21 with one not voting: Florida Senator Marco Rubio, who is vying to win the GOP presidential nomination.

That leaves 21 Senate Republicans who voted against the amendment.

Though the U.S. illegally tortured prisoners, some of them innocent, in the recent past—and even though none of those instances of torture took place in a ticking time-bomb scenario, the absurd hypothetical that torture apologists are always raising—these Senators have cast a key vote against important anti-torture safeguards.

Here are their names:

Jeff Sessions of Alabama, a former U.S. attorney and state attorney general Tom Cotton of Arkansas, an Iraq War combat veteran Michael Crapo of Idaho James Risch of Idaho Daniel Coats of Indiana, who is not expected to seek reelection Joni Ernst of Iowa, who has served more than two decades in the Army Reserve and National Guard Pat Roberts of Kansas, a former chairman of the Senate intelligence committee, which oversees the CIA Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the Senate majority leader David Vitter of Louisiana Thad Cochran of Mississippi, a former Eagle Scout and Navy veteran, and current chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee Roy Blunt of Missouri Deb Fischer of Nebraska Benjamin Sasse of Nebraska Jim Inhofe of Oklahoma, who said during a congressional hearing into the Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse scandal, “I'm probably not the only one up at this table that is more outraged by the outrage than we are by the treatment.” James Lankford of Oklahoma, who holds a graduate degree in divinity and was formerly an evangelism specialist for the Baptist General Convention of Oklahoma Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, who is seeking the GOP presidential nomination and worked to strip federal courts of jurisdiction to hear cases from Guantanamo Bay detainees Tim Scott of South Carolina, an evangelical Christian who is opposed to abortion, gay rights, stem cell research, and euthanasia, and once fought to install the ten commandments outside a municipal building where he was an elected official John Cornyn of Texas, a former state attorney general and associate justice of the Texas Supreme Court Orrin Hatch of Utah, who called Jay Bybee, a primary author of Bush era torture memos, “one of the most honorable people you'll ever meet” while defending him against torture critics who wanted to remove him from a federal judgeship. Mike Lee of Utah, who has opposed extending controversial portions of the Patriot Act as well as the indefinite detention of Americans in the War on Terrorism John Barrasso of WyomingThe wrongheaded votes cast by these Republicans should not be forgotten. Challengers should question their moral fitness in future primaries—many reside in states filled with Christians whose faith teaches that torture is an abomination. And anytime one of these Senators seeks higher office, is considered for a presidential appointment, or seeks a leadership position on a committee related to national security, he or she should be pressed about his or her position on the abuse of prisoners. If unwilling to condemn torture in speech and deed, all “nay” voters should be denied any role that puts them in a position to enable torture in a future panic.

June 16, 2015

The Hacking of America's Pastime

A pitcher uses pine tar to get a better grip on a baseball. A batter takes performance-enhancing drugs to knock a pitch out of the stadium. A baserunner steals a catcher’s sign to tip off a teammate about an upcoming pitch. Players bet on and even throw games.

The scandalizing of America’s pastime is nearly as old as the pastime itself. But Tuesday’s New York Times story about an investigation into whether employees of the St. Louis Cardinals hacked into the Houston Astros player database is like nothing professional baseball has ever seen.

In fact, the news is a first for any professional sport. “The attack would represent the first known case of corporate espionage in which a professional sports team hacked the network of another team,” wrote the Times reporter Michael Schmidt. According to Schmidt’s report, FBI and Justice Department investigators have evidence that in 2013, members of the Cardinals front office infiltrated the Astros’ specialized system and became privy to “internal discussions about trades, proprietary statistics and scouting reports.”

To find a more unnatural-seeming baseball story, one might have to go back to the moment when Johnny Damon sported a New York Yankees jersey. The story is particularly jarring because the alleged culprit—the St. Louis Cardinals—is one of the league’s oldest and most respected franchises.

“Ambitious baseball front offices make their living locating and exploiting inefficiencies in the system.”Since the story broke, debate has raged over whether the motivation for the alleged attack might have been strategic or emotional in nature. The database in question was built by a former Cardinals executive named Jeff Luhnow, who was hired away by the rival Astros in 2011 in part because of his skill at using big data to build efficient player rosters.

“Ambitious baseball front offices make their living locating and exploiting inefficiencies in the system,” Nicholas Dawidoff, a longtime baseball writer and author of The Catcher Was a Spy, wrote in an email.

Luhnow built a similar model for the Cardinals, which won the World Series in 2011. The Astros, which were historically bad after Luhnow first became their general manager and in 2013 when they were allegedly hacked, are now (surprisingly) one of the league’s best teams.

It’s still not clear how hacking into the Astros system might have helped the Cardinals, or how significantly the system might have been hacked. What is clear is that, for the second time in a month, federal agencies are taking a lead role in a major sports scandal. As Craig Calcaterra notes, the Cardinals’ alleged hack, however small, would fall under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, which was used to prosecute hacker Aaron Swartz. Considering that the hack would have involve crossing state lines, this scandal has the potential to get even stickier than pine tar.

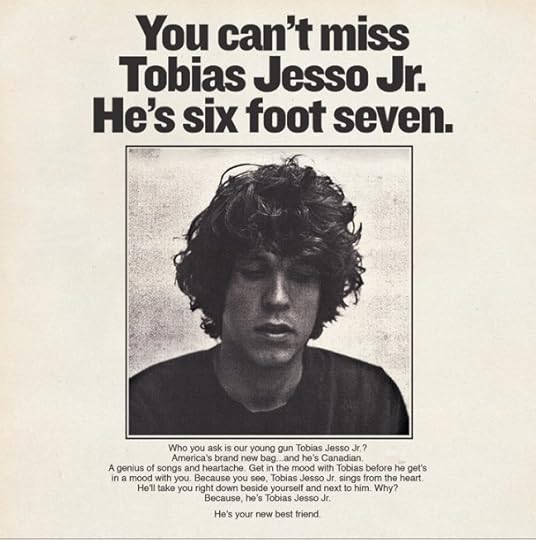

When Words Sold Music

Earlier this year, the image of a mop-headed young man went up on a billboard off Sunset Avenue. “You can’t miss Tobias Jesso Jr.,” the text said. “He’s six foot seven.” On similarly designed posters, in smaller type, were some statements of dubious grammatical merit and general musical praise—“A genius of song and heartache. Get in the mood with Tobias before he get’s in the mood with you. Because you see, Tobias Jesso Jr. sings from the heart.”

True Panther

True Panther The fragments, the vague promises of genius, the period as favored punctuation mark—even setting aside the yellowed background color and cruddy ink-on-paper picture quality, the ad was a clear callback to printed music ads of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Which makes sense: Jesso, one of the most acclaimed new musicians of 2015, sounds a lot like Randy Newman or Paul Simon. His music recreates the earnestness of those singers’ heyday but with the faintest hint of a smirk, not unlike the uncanny-valley text used in his album’s ad campaign.

How marketing defined and influenced an era

How marketing defined and influenced an eraRead More

“I feel like the visuals of that era have really been mined to death,” said Dean Bein, the head of Jesso’s label, True Panther. “The pop-art, psychedelic whatever. But the humor, the language, and the style, where you’re trying to have a conversation with whoever’s looking at the ad, you’re trying to tell a story—I haven’t seen so much of that.”

The early, much-romanticized years of rock magazines—the ‘60s and ‘70s, when Cameron Crowe was living out Almost Famous and Lester Bangs was starting to inspire a generation of imitators—were a time when print advertising relied on a lot more words than it usually does today, and when it was one of the few means available to promote music to new audiences. (MTV wasn’t around; YouTube-style song sampling would have seemed like science fiction.)

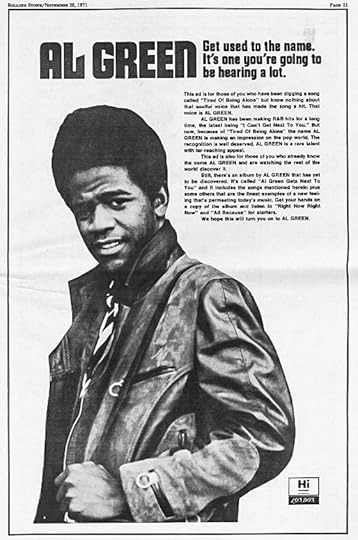

Rolling Stone

Rolling Stone Of course, per the famous expression about dancing about architecture, writing about music is hard. Rolling Stone and others were pioneers in doing just that, but advertisers who tried to capture the same energy and linguistic innovation of the magazines’ editorial content were hobbled by the fact that their rock criticism could contain no actual criticism. Instead, many of their ads read like resumes. Promotional space in old Rolling Stones is filled with notices for releases by sidemen for famous artists, whose impressive credentials made for an easily made pitch—usually in the same declaratory but familiar voice. Bein said that voice appealed to his team when coming up with ways to promote Jesso: “It was so much more conversational—and maybe in a way that we think of as cheesy now, but I think that started resonating with us.”

Rolling Stone

Rolling Stone Other copywriters made spirited attempts to sound like authentic, gonzo record reviewers. The track-by-track description of Fairport Convention’s Angel Delight set out to prove that ads could be as hip and filthy and in tune with the counterculture as anything. One song is referred to as “a warning to all those about to launch their frail human canoes on the raging river of clap.”

Rolling Stone

Rolling Stone Genre and politics also made for useful ad grist. The mainstream began fragmenting with ever more genres, leading to the fan wars over “realness” that still rage today—progressive rock vs. “MOR,” guitar-lovers staging “disco sucks” demonstrations, etc. Identity and gender were increasingly hot topics as well. This ad for Sirani Avedia, from a late 1979 Rolling Stone issue, just about hit upon every talking point the preceding 10 years had produced:

Rolling Stone

Rolling Stone Some of the best copy was for artists who had their own mythology and shtick. Is it any surprise that Parliament Funkadelic was able to stand out with tales of “the baddest motherfunkers from throughout the galaxy” and commands to “GO WIGGLE!”?

Rolling Stone

Rolling Stone Flip through the music magazines published today, and the album ads that still exist are almost entirely image-based, or else feature a couple of quotes from favorable reviews. Which makes sense, given both the distribution changes for music, the shift in pervading ad styles—fewer words!—and the obvious pitfalls of trying to pitch records that the reader couldn’t yet listen to. The ad writers themselves, even in the ‘70s, were aware of the strange task before them. The one below tells a short story of being asked to write a Rolling Stone ad for Ampex records.

Rolling Stone

Rolling Stone The story features a debate over what exactly to portray (“A full-page shot of a nude 12-year-old boy”? “Maybe something rousing copywise to make them do competitive somersaults over at Warner Brothers”?). But in the end, “we never settled on no thing … Why, I think we even came round to believing that ads can’t really sell records.”

But while the Jesso ad might seem to send up that old style, it’s also a loving embrace of it and a reaction to recent trends towards obscurity, mystery, and image in music promotion. “Everything feels like it’s become very logo-based, holding away information,” said Bein. “But it’s fun for people who have become Tobias fans to see his personality and the context for his music in all these different ways, not just visuals but being able to read a long-form thing about him.”

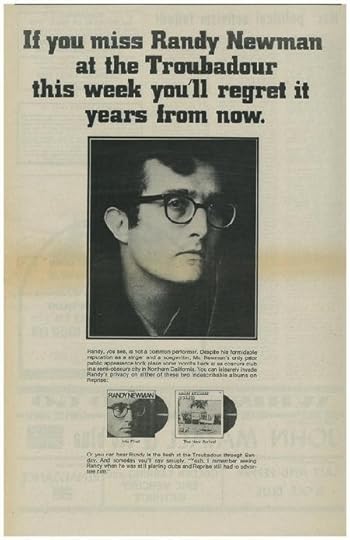

The most direct inspiration for the Jesso poster was a promo for Randy Newman in concert. The parallels are obvious, and like many of the ads of its era, it couldn’t help but be a little meta. The text promised that one day, the people who went to watch Randy Newman live could brag, “I remember seeing Randy when he was still playing clubs and Reprise still had to advertise him.”

Poster Scene

Poster Scene

The 'Carnival Barker' Joins the 2016 Circus

NEW YORK—The Donald J. Trump campaign for the presidency began here on Tuesday with the expected gusto: Descending a gold-rimmed escalator into an atrium packed with reporters and cameras inside the eponymous tower, the golden-haired mogul promised to be “the greatest jobs president God ever created.” He lampooned the men and women now running the government—as well as those running to run it—as idiots and losers, and he vowed to bully foreign terrorists and American businessmen alike in his drive “to make America great again.”

Yes, the Trump campaign started with a flourish, and fittingly, it also began with a bald lie. “This is some group of people. Thousands,” he said, as he surveyed a modest audience that must have seemed several times larger in his mind. In truth, Trump strode past perhaps a couple hundred supporters wearing t-shirts emblazoned with his name and slogan (“Make America Great Again”), and holding signs distributed by his campaign. Another hundred-or-so members of the media were jammed into the pit-like atrium below, giving the appearance of a large crowd and demonstrating that he did, in fact, understand the first rule of campaigning: Always hold your events in a space a little too small.

“There’s never been a crowd like this,” Trump crowed. He had a point there. While Trump’s modest draw was dwarfed by the hordes that attended the kick-off events for Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, and most of the dozen other Republicans running, none of those amateur showmen thought, as Trump apparently did, to put their most devoted supporters in the balcony. If nothing else, his priorities are clear: Press in the front, voters in the back. (Except for George Stephanopoulos, that is. The ABC News star arrived too late to get a good view of The Donald and was forced to watch Trump’s announcement on a monitor off to the side.)

After a 15-minute, nativist diatribe in which he declared that the American Dream “is dead” and that the U.S. has become “a dumping ground for everybody else’s problems,” Trump finally declared what everyone had come to hear. “Ladies and gentleman,” he said, “I am officially running for president of the United States.” With that formal announcement, the hearts of a dozen (or perhaps a hundred) GOP operatives sank. As Buzzfeed’s McCay Coppins has ably documented, Trump has been toying with a run for public office for the better part of 25 years, but he’s never actually done it—until now.

And really, why not run? The Republican field is a splintered free-for-all, and to the chagrin of the party establishment, Trump could find himself on the 10-person debate stage by dint of his universally-recognized name alone, without even setting foot in Iowa and New Hampshire. As of this moment, Trump is polling ahead of Rick Perry, John Kasich, Rick Santorum, Lindsey Graham, Carly Fiorina, Bobby Jindal, and George Pataki—that’s two current governors, two former governors, and a sitting U.S. senator, if you’re counting. He’s 69 years old (so it’s probably now or never), his reputation among the political elite has nowhere to go but up, and he has nothing to lose except money—and he’s done that plenty of times before.

The Republican field is a splintered free-for-all, and to the chagrin of the party establishment, Trump could find himself on the 10-person debate stage by dint of his universally-recognized name alone.Of course, as others have noted, Trump could be punking us again. He could fade quickly back into reality TV, or he could use the auspices of a campaign to promote himself for a few months and drop out before the voting starts. The banners, t-shirts, and bumper shirts at his Manhattan launch event were paid for by an “exploratory committee,” and he apparently hasn’t yet filed his paperwork with the FEC. But Trump insisted that he would (“without extensions”), and from the Trump Tower he was headed to Iowa and then on to New Hampshire and South Carolina later in the week. For now, he’s a candidate.

There are few people who cause the political establishment more agita than Trump. President Obama famously called him a “carnival barker,” a rare presidential statement with which many Beltway Republicans would agree. They fear he’ll make a mockery of their nominating contest, bringing down an already-damaged party brand in advance of the general election. More cynical observers would say that Trump is the candidate a disengaged, celebrity-obsessed America deserves.

Yet all the hand-wringing might be a bit much. “Carnival barkers” have a long history in American politics, and voters have long been drawn to anyone who can credibly claim they are not politicians. The people of California have twice elected Republican actors as their governor, including Ronald Reagan, who went on to become president. Minnesota voters sent the fake-wrestler Jesse Ventura to the statehouse and the comedian Al Franken to the Senate. As for his views, Trump’s political incorrectness is no more objectionable than that of many lawmakers who have repeatedly been elected to Congress—that more conventional proving ground for the presidency. (I’m looking at you, Louie Gohmert.) And say what you will about Trump, but he already has at least one astonishing and unprecedented political accomplishment on his résumé: He almost single-handedly forced the democratically elected president of the United States to prove that he was constitutionally eligible to hold the office. That’s not to say that Trump has a chance—he doesn’t. But is he really all that out of place on the stage?

Democrats greeted Trump’s entry into the race with relish, happily bestowing upon him the kind of gravitas that Republicans won’t. “Today, Donald Trump became the second major Republican candidate to announce for president in two days,” said Holly Shulman, a spokeswoman for the Democratic National Committee. “He adds some much-needed seriousness that has previously been lacking from the GOP field, and we look forward hearing more about his ideas for the nation.”

“He adds some much-needed seriousness that has previously been lacking from the GOP field, and we look forward hearing more about his ideas for the nation.”So who were the people who turned up on Tuesday morning, walked into the lobby of the Trump Tower, put on a Trump t-shirt, and screamed (at the exhortation of a man with a bullhorn), “We want Trump! We want him now!” For the most part, these are the people who tell pollsters that electing a “strong leader” is their highest priority. “I like how bold he is,” Simone Perry told me. “He’s not afraid to say what’s on his mind. He’s not a politician.” Perry, a 40-year-old from the Bed-Stuy section of Brooklyn, said she voted for Obama and (gasp) for Bill de Blasio. “But I don’t think that was the right thing to do,” she said sheepishly, disavowing her past support for the liberal New York mayor.

Plenty of the Trump faithful were tourists, including a group of choir girls from—where else?—Iowa, who stumbled onto the event while they were browsing at Tiffany’s next door. “I didn’t even know he was running,” said Lauren Pfeil, who will turn 18 in time for the caucuses next year. They didn’t need a lot of convincing. “I’m for Trump right now, because he’s made a strong impression on me,” explained Katherine Smoldt.

No one cheered louder for Trump than Lori Burch, a 56-year-old retiree from Jersey City who leaned over a railing alongside the escalator and offered him vocal encouragement several times during his speech. “Thank you, darling,” Trump said at one point, when her enthusiasm became too much to ignore. Burch told me that she, too, voted twice for Obama, but said she was done with “career politicians.” “The man’s been bankrupt, and he came back,” she said of Trump.

He sure did put on a show. In what may have been a first for a presidential campaign launch, Broadway classics blared from the speakers at dance-club levels. The exception was, “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” which was an odd choice for a campaign rally. Did it represent a platform of belt-tightening austerity? Or did it refer to the man himself, who is now running for president whether anyone likes it or not? The irony is that although Trump may be offering himself up as the anti-politician, there is nobody who does a better job at telling people what they want to hear, regardless of how accurate or nonsensical it is.

Trump on Tuesday presented himself as the Herculean savior of the American dream. He promised to repeal and replace Obamacare, rebuild the nation’s infrastructure, construct a “Great Wall” on the Southern border (“Nobody builds walls better than me”), defeat ISIS, and literally intimidate the titans of American business into re-opening factories that had been shipped overseas. “We’re dying,” he lamented. “We need money.” And of course, he has plenty of that. Seeking to put to rest years of speculation about his true wealth, Trump’s campaign gave reporters a laminated sheet outlining his financial assets and debts, claiming a net worth of $8.7 billion—enough to make Mitt Romney and the Clintons look like paupers by comparison.

Trump repeatedly lapsed into the sort of anti-immigrant screed to which he’s been prone in recent years. He referred to immigrants coming over from Mexico as “criminals” and “rapists,” although he said that some, “I assume, are good people.” Mostly, however, Trump did what he does best: He bragged about his success. And the hundreds—not thousands—in attendance seemed to eat it up. There might be a constituency for his antics, but they are unlikely to wear well over the long months of the campaign. After 45 minutes of Trump talk on Tuesday morning, the enthusiasm inside the tower lobby was waning. The Donald returned to some semblance of his script, finished up, and walked out to more loud music.

Mercifully, he took no questions.

How a Suspected War Criminal Got Away

The conviction of Charles Taylor seems like a signal triumph for international courts. The former Liberian president was caught after fleeing justice, tried in the Hague, convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity, and sentenced to 50 years in prison. The system worked.

Or did it? Traveling in Liberia recently, John Mukum Mbaku, a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a professor at Weber State University, heard rumors than Taylor was actually in cahoots with the CIA and living it up outside of prison. But you could see the trial on TV, he protested. Oh sure, came the reply. But you can put anything on TV—that doesn’t make it real.

That might seem conspiratorial, but in a nation where institutions can be corrupt, incompetent, or both, it’s not surprising. It also offers some insight into the bizarre near-arrest and ultimate escape of Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir this week.

Bashir is one of the world’s most wanted men, with charges of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide leveled against him by the International Criminal Court, in connection with violence in Darfur in the 2000s. By visiting South Africa, Bashir tempted fate, but he managed to get away thanks to a combination of division among South African authorities and a general ambivalence about the ICC throughout the continent.

Bashir was in South Africa to attend an African Union summit. Because South Africa is a member of the ICC, it was obligated to arrest him on the two outstanding warrants—one from 2009 and one from 2010—against him. South Africa’s High Court court ruled on Sunday that he shouldn’t be allowed to leave the country until it finished deciding on the obligation to arrest him. Monday morning, Bashir’s plane took off from Pretoria without obstruction, bound for Khartoum. A few hours after that, the court ruled that he should have been held.

“The government’s failure to arrest Bashir is inconsistent with the Constitution.”“The government’s failure to arrest Bashir is inconsistent with the Constitution,” Judge President Dunstan Mlambo said.

But of course by then it was too late. Six years after the ICC first issued a warrant for Bashir, this was the closest he’d come to being arrested. Now the court’s champions and detractors alike are saying his near-miss is a serious blow to the court’s standing. “South Africa has been a traditional defender of the ICC and has previously insisted that it would arrest Bashir if he stepped foot on its territory,” wrote Mark Kersten, a researcher at the London School of Economics who studies criminal justice and conflict resolution. “His visit to South Africa with impunity seemingly sent a powerful signal that the ICC’s indictment no longer constrains his movements.”

The high court’s ruling does likely mean that Bashir won’t be able to return to South Africa, since he’d face arrest there. And the fact that the court moved against him is a sort of progress. Since the ICC warrant was issued, he’s visited numerous other member countries, only to have them refuse to act, including Chad, Kenya, and Nigeria.

Opinion about the ICC has shifted in Africa since it was chartered in 1998. Initially, it had strong support—particularly in the aftermath of the Rwanda genocide, Mbaku has written, when “there was an urgent need in Africa to squarely confront impunity and the mass violation of human rights.” Since then, some governments and thinkers have apparently revised their opinions.

One reason is that every indictment issued by the ICC has been in Africa. The court’s jurisdiction is somewhat hobbled by the non-participation or non-cooperation of many countries, most notably the United States. But the fact remains that Africa has been the focus of a court based in Europe, and given that memories of colonialism are in some places still fresh and very raw, that raises hackles.

Add to that the fact that while the court can mete out an abstract sort of justice, it has little power to make things right for victims. It’s all well and good to lock up a perpetrator, but it doesn’t do much to restore the damage. When those trials happen in The Hague, far away from where the crimes were committed, there may be little chance for many victims to take part in the proceedings anyway.

Taylor’s trial was not in the ICC but in the Special Court for Sierra Leone, though the trial was moved to The Hague for security reasons. But to Mbaku, it demonstrates the flaw in international justice systems like the ICC.

“The international community pats itself on the back that they were able to force Charles Taylor to stand up for what he did, but in terms of looking at the big picture, I don’t really see what the benefits are for the people of Liberia and the people of Sierra Leone,” Mbaku told me in an interview.

While Bashir’s indictment in 2009 irked many African leaders, the indictment of Uhuru Kenyatta, now the president of Kenya, for crimes against humanity during post-election violence in 2007 and 2008, seems like it was a breaking point. The indictment was widely criticized by African leaders. The African Union has argued that no sitting head of state should be prosecuted by the ICC. In December, the ICC withdrew charges against Kenyatta, citing the inability to acquire evidence.

“If you are an African, you know that African countries are not currently able to deliver justice. The question is, who is going to deliver it?”There’s a clear problem with the African Union’s proposal: Bashir has been Sudan’s leader since 1989 and there’s little suggestion he’ll leave unless either his health or a coup forces him. He’s basically empowered to act with impunity within Sudanese borders, even if the universe of countries to which he can travel is ever-shrinking. But the South African government took a similar position to the AU before High Court, saying its agreement to grant immunity to visiting heads of states trumped its obligations under the ICC. The court disagreed—but by then Bashir was gone. And the government’s skeptical view of its ICC obligations shows the danger of ambivalence toward the ICC through the continent.

“If you are an African, you know that African countries are not currently able to deliver justice. The question is, who is going to deliver it?” Mbaku said. For now, there’s simply no alternative to the ICC, but “this should not be a long-term solution. Each African country should be able to develop its legal system so that it would administer justice at the local level.”

That would certainly sidestep the problem of relying on the whims of the South African or Chadian or Nigerian government to arrest a leader like Bashir. Building institutions and rule of law to achieve that will take years or decades. On the other hand, the ICC doesn’t seem to have much power to bring Bashir to justice either.

Al-Qaeda's Middle-Manager Problem

Nasir al-Wuhayshi, the leader of al-Qaeda’s branch in Yemen, is now the second major jihadist figure since the weekend to be reported killed. News of his death in a Friday airstrike in Yemen surfaced on Monday, following weekend airstrikes in Libya that reportedly killed Mokhtar Belmokhtar, an Algerian terrorist affiliated with al-Qaeda in North Africa. U.S. officials

There Is No Global Jihadist 'Movement'

How al-Qaeda’s franchises behave can come down to people like Wuhayshi and Belmokhtar. Wuhayshi, who in 2009 announced the merger of al-Qaeda’s Saudi and Yemeni branches into the unified al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, rose in the central hierarchy to be appointed al-Qaeda’s “general manager” in 2013, a job that involved coordination and communication among the group’s far-flung affiliates. Belmokhtar, by contrast, appears to have been more of a problem employee—a bureaucratic infighter who chafed at authority and quit when challenged. In an October 2012 letter found in Mali by Rukmini Callimachi, then of the Associated Press, AQIM’s leaders said Belmokhtar ignored management’s phone calls, failed to turn in expense reports, and skipped meetings. “The employee,” Callimachi wrote, “responded the way talented employees with bruised egos have in corporations the world over: He quit and formed his own competing group.”

It was through that new organization that Belmokhtar achieved a new level of international infamy in January 2013 when he claimed responsibility for one of the largest hostage-taking operations in history, at a gas plant near In Amenas, Algeria. His fighters held hundreds of foreign and local workers for four days; 38 of them died. In a video message claiming responsibility for the In Amenas attack on behalf of his new group, “Those Who Sign in Blood,” he said, “We did it for al-Qaeda.” As Callimachi pointed out on Twitter Sunday night, Belmokhtar—who named his son after Osama bin Laden—went out of his way to emphasize his loyalty to al-Qaeda central, repeatedly pledging fealty to leader Ayman al-Zawahiri. Apparently, he just didn’t want to deal with the local middle management.

Belmokhtar’s story demonstrates that a split organization doesn’t necessarily mean a weakened or less violent one. Indeed, it was another problem al-Qaeda employee who helped develop and spread the brutal tactics that have since become a hallmark of ISIS, the al-Qaeda affiliate turned competitor. The savagery of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the Jordanian who led al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) until his death in 2006, was famously chided by al-Qaeda’s now-leader Ayman al-Zawahiri, then Osama bin Laden’s deputy, who urged him to restrain himself. ISIS, the successor of AQI, also emerged from what in essence was another management dispute, when Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the head of what was then the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI), attempted to absorb al-Qaeda’s Syrian affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra. Zawahiri told him he couldn’t; Baghdadi struck out on his own. That was in 2013. A year later, his new organization swept into the Iraqi city of Mosul and declared itself a caliphate. The organization is now openly fighting al-Qaeda affiliates across multiple fronts, including in Syria and Libya.

America’s success in killing al-Qaeda leaders has the potential to reproduce these kinds of disputes as successors compete for position within the local affiliate and the larger organization. The United States has more than once killed leaders of al-Qaeda’s Somali affiliate, al-Shabab, which has continued to stage spectacular attacks—achieving its highest death toll yet in an attack on Kenya’s Garissa University College this year that killed 147 people. AQAP itself, which has lost several senior leaders in addition to Wuhayshi this year, has at the same time expanded the territory it holds in Yemen.

If al-Qaeda has indeed lost two loyal operatives in recent days, that will likely further inhibit Zawahiri’s ability to influence al-Qaeda affiliates at the local level. But it’s precisely the local power of those franchises that will determine whether or not that’s a good thing for the United States.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower