Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 404

June 26, 2015

Scalegalese: The Distinct Vocabulary of Antonin Scalia

Updated on June 26

“Words have meaning,” Antonin Scalia insisted in 2013. “And their meaning doesn’t change.”

That second argument is something most linguists and lexicographers will, at minimum, quibble with. It is also, however, a foundation of Scalia’s particular approach to Constitutional interpretation. “I mean, the notion that the Constitution should simply, by decree of the Court, mean something that it didn’t mean when the people voted for it,” the associate Supreme Court justice explained to New York magazine’s Jennifer Senior—“frankly, you should ask the other side of the question! How did they ever get there?”

How indeed. Scalia is someone who loves words—not just as sources of literary performance (alliteration! puns! Kulturkampf! argle-bargle!), but also as sources of semantic stability. Words, Scalia believes, root us, collectively and epistemologically. So his famously saucy approach to language isn’t just about bringing literature to legalese, or about the schadenfreudic delights of sending reporters scrambling to dictionaries and thesauri when he issues a scathing dissent. It’s also a philosophical declaration about the unchanging nature of old truths, whatever document may enshrine them. As the speechwriter Jeff Shesol wrote in the New Yorker last year, “His approach has always been to reach for a dictionary; find, in one edition or other, a definition that drives toward his predetermined decision; and express, eyes wide with disbelief, utter amazement that anyone could even think of seeing it any other way.”

Related Story

The Twilight of Antonin Scalia

As a result, Scalia has cited, in his opinions, not just the Random House College Dictionary, but also Noah Webster’s American Dictionary of the English Language (publication date: 1828), Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1773), and Timothy Cunningham’s A New and Complete Law Dictionary (1771). Because words have meaning. And their meaning doesn’t change.

It was itself meaningful, then, that in his dissent on Thursday in King v. Burwell, arguing against the Court’s latest upholding of Obamacare, Scalia concluded: “Words no longer have meaning if an Exchange that is not established by a State is ‘established by the State.’”

It was also meaningful that he added, of the majority decision:

“The Court’s next bit of interpretive jiggery-pokery involves other parts of the Act that purportedly presuppose the availability of tax credits on both federal and state Exchanges.”

And also that he called the Court’s upholding of Obamacare the result of “somersaults of statutory interpretation.”

And also that he concluded: “We should start calling this law SCOTUScare.”

It was meaningful as well that, on Friday, in his dissent in Obergefell v. Hodges—which found that same-sex marriage is a Constitutional right—Scalia fumed, “The Supreme Court of the United States has descended from the disciplined legal reasoning of John Marshall and Joseph Story to the mystical aphorisms of the fortune cookie.”

And that, in the same dissent, he added, riffing on the majority opinion:

“The nature of marriage is that, through its enduring bond, two persons together can find other freedoms, such as expression, intimacy, and spirituality.” (Really? Who ever thought that intimacy and spirituality [whatever that means] were freedoms? And if intimacy is, one would think Freedom of Intimacy is abridged rather than expanded by marriage. Ask the nearest hippie.

On the one hand, of course, this is just Scalia being Scalia (and the rest of us being Scalia’ed). Jiggery-pokery! The nearest hippie! In one of his earliest dissents, in 1987’s Johnson v. Transportation Agency, Scalia quoted that linguistic ur-innovator: Shakespeare. Citing an exchange from Henry IV, the new associate justice invoked “spirits from the vasty deep.”

In Romer v. Evans, a 1996 case on LGBT discrimination, he declared that “the Court has mistaken a Kulturkampf for a fit of spite,” referring to “the German policies designed to reduce the role and power of the Roman Catholic Church in Prussia, enacted from 1871 to 1878 by the Prime Minister of Prussia, Otto von Bismarck.”

In PGA Tour v. Casey Martin, a 2001 case addressing the Americans with Disabilities Act’s place in professional sports, he referred to the notion of “Platonic golf.”

In 2009, he debated a presenting lawyer about the ontology of the word “choate.” (“There is no such adjective,” Scalia insisted. “I know we have used it, but there is no such adjective as ‘choate.’ There is ‘inchoate,’ but the opposite of ‘inchoate’ is not ‘choate.’”)

In his dissent in 2013’s Maryland v. King, a case that revolved around the constitutionality of taking DNA samples from arrest suspects, Scalia warned of the dangers of creating a “genetic panopticon.”

Words, in the Court, are proxies for Constitutional interpretation: either living, breathing, contextual things, or inscribed to their original coinage.In his dissent against the striking down of the Defense of Marriage Act, Scalia famously categorized the majority opinion in the case as “legalistic argle-bargle.” (The term itself, its argliness and bargliness to the contrary, is not argle-bargle: It means, the lexicographer Ben Zimmer pointed out, “a description of ‘a verbal dispute’ or ‘a wrangling argument.’”)

And in that 2013 interview with New York magazine, Scalia used the word “ukase”—as in, the decision to strike down DOMA was “not at the ukase of a Supreme Court.”

His interviewer, Jennifer Senior—summoning the reaction most Americans would have to this creative diction—replied, simply: “What?”

“U-K-A-S-E,” Scalia answered, spelling it out. “Yeah. I think that’s how you say it. It’s a mandate. A decree.”

The Justice, the National Constitution Center notes, was correct. Merriam-Webster defines “ukase” as “a proclamation by a Russian emperor or government having the force of law.”

All of which—words have meaning. And their meaning doesn’t change—is classic Scalia. It’s words interpreted not just as conduits of meaning, but as solidifiers of it.

In The Second Amendment: A Biography, Michael Waldman notes that Scalia “has the feel of an ambitious Scrabble player trying too hard to prove that a triple word score really does exist.” But the stakes in his game, argle-bargle and jiggery-pokery and fortune cookiery notwithstanding, are high. Words, in the Court, are—or, at least, they can be—proxies for Constitutional interpretation. Justices can see them either as living, breathing, contextual things, or as things that are inscribed to their original coinage. There cannot, Scalia insists, be two sides to this argument. Elena Kagan, in a back-and-forth opinion-battle with Scalia last year, declared that “we must (as usual) interpret the relevant words not in a vacuum,” but instead with regard to their “structure, history, and purpose.”

A notion to which, in a flourish fitting of his great philosophical frustration, Scalia has now replied: “Pure applesauce.”

The Soccer Moms

Amy Rodriguez had just won an Olympic gold medal when she discovered she was pregnant. Rodriguez, a 28-year-old forward for the U.S. women’s soccer team known as A-Rod, says her son, Ryan, is the “biggest blessing in her life,” but initially, she panicked. She had no idea how her body would react or how willing she’d be to leave her son to go to training camps and tournaments. “I had no idea how I would do it,” she says. “I just knew I wasn’t ready to be done.”

Related Story

‘Pele With a Skirt’: The Unequal Fortunes of Brazil's Soccer Stars

Having signed with the Seattle Reign in the third iteration of a U.S. women’s pro league, she was expected to be their star forward. Instead, she spent the 2013 season watching the team play without her. In September of that year, a month after giving birth, Rodriguez went to breakfast with the Reign coaching staff. They told her they were eager to get her back on the field and gave her a tiny baby onesie with the team’s logo. “I was like, okay, they are excited about me,” says Rodriguez. “It meant a lot to me.”

One month later the team traded her to Kansas City F.C.

Rodriguez had been traded before; she understood that it was a business decision. “I interpreted it as, ‘Oh, they don’t have faith in me, they don’t think I can come back.’ I was definitely motivated to prove to them, that, ‘Hey, you probably should’ve kept me.’” While her husband Adam had family in Seattle whom the couple had been counting on to help with their newborn, in Kansas City their closest family members would be 1,700 miles away. Adam, a physical trainer, couldn’t go with her. For the six-month long season, they would be forced to live “like a divorced household,”as she put it, taking turns spending time with their son.

Before becoming pregnant, Rodriguez had intended to wait to start a family until she’d finished her professional career. Now, she’d be attempting to follow the lead of the athlete-mothers who came before her. In 2015, there are more and more examples of female athletes who not only continue to compete after becoming mothers, but who also perform better after having children. Of course, that’s not how the story unfolds for everyone. “I’d seen teammates come back really strong,” says Rodriguez. “But for others, it was a lot more difficult—they had a rockier road.” Athlete moms are up against more than the physical challenge of mounting a comeback. In the fledgling National Women’s Soccer League, where players make as little as $6,800 a year, they face sacrifice, instability, and uncertainty—circumstances that become much more difficult to navigate when you’re no longer thinking only of yourself.

***

In 1894, three years after giving birth to her son, Blanche Hillyard became the first of four mothers ever to win Wimbledon. In the 1948 London Olympics, the Dutch sprinter and mother of two Fanny Blankers-Koen won four gold medals—more than any other athlete at the games that year. In 1996, in the first year of the WNBA, the women’s professional basketball league, Sheryl Swoopes, the number-one draft pick, announced her pregnancy—she missed the first two-thirds of the seasons but made it back onto the court six weeks after giving birth, leading the Comets to a Championship. Many WNBA players have followed her example—Tina Thompson, Lisa Leslie, Candace Parker all became mothers and continued to star in the league. In 2010, there were five mothers on the Los Angeles Sparks alone.

In the women’s soccer world, in 1994, Joy Fawcett became the first player to have kids mid-career. She’d go on to play for another decade—she was the only competitor to play all minutes of the 1995, 1999, and 2003 Women’s World Cups. She also played in the U.S.’s first attempt at a women’s pro league, Woman’s United Soccer Association, which grew out of the success of the 1999 World Cup. Playing for the San Diego Spirit, Fawcett was back on the field six weeks after giving birth to her third child. She breastfed her daughter at half time.

Her teammates reported that she came back from every pregnancy faster and stronger. Her U.S. teammate Julie Foudy told ESPN, “In the past, all those years before Joy, players would say, ‘I'm going to retire because I want to have kids; I have to quit because it’s time to start a family.’ But Joy said, ‘Wait, why do I have to retire, why don’t I just keep playing and I'll pop ‘em out in between World Cups and Olympics?’” Other mid-career soccer moms followed—Carla Overbeck, Kate Markgraf, Danielle Fotopoulos, Tina Ellertson.

The current national-team player Christie Rampone is Fawcett’s successor as team super-mom. Rampone has two daughters, nine-year-old Reece and five-year-old Rylie. She’ll turn 40 this month—the oldest player in Women’s World Cup history—and is still one of the fastest and fittest on the team. Professionally, she’s played in all three iterations of the women’s pro league in the U.S. She was three months pregnant with Rylie when she won the 2009 championship of the Women’s Professional Soccer league. “I always joke with Christie that she made it all look so easy,” says Rodriguez. “I had no idea how hard it was.”

***

Rodriguez wasn’t the only women’s soccer mother to give birth in 2013—the U.S. national players Heather Mitts, Shannon Boxx, and Stephanie Cox also started their families. Mitts announced her retirement from soccer, but Boxx, A-Rod, and Cox weren’t ready to hang up the cleats; they all intended to make a run for the 2015 World Cup roster. All three women were considered long shots—in a country with an ever-deepening talent pool, it’s harder and harder to hold on to your spot. As Rodriguez puts it, “When a player can’t play, for whatever reason, another talented player steps up.”

Amy Rodriguez (left) and New Zealand defender Rebekah Scott (right) fight for the ball at a game April 2015. The U.S. team defeated New Zealand 4-0. (Jeff Curry / USA Today Sports)

Amy Rodriguez (left) and New Zealand defender Rebekah Scott (right) fight for the ball at a game April 2015. The U.S. team defeated New Zealand 4-0. (Jeff Curry / USA Today Sports) Cox, a defender with nearly 100 appearances with the national team, was Rodriguez’s former Seattle teammate. (When A-Rod got traded to Kansas City, she gave her Seattle Reign onesie to Cox, saying, “You’ll have more use for this than I will.”) Cox gave birth four months before A-Rod did and made it back on the field for the last four games of the 2013 Seattle Reign season.

Boxx, at age 37, perhaps faced the longest odds: She had lupus, a chronic autoimmune disease that got worse during and after pregnancy. “Getting back to where you were is tough, especially at my age,” she says. “It took my body a lot longer than I’d expected. I went off the radar for so long.” She was away from the national team for two years before she came back into a residency camp in January 2015—which left only a handful of months to play her way onto the team. “I’d been on the team for 10 years. I’d won three Olympic Gold Medals—but now I had to start over and fight to get my spot back.”

Between Rampone and the four national team players who gave birth in 2013, it might seem like the women’s pro league is full of mothers, but that’s not really the case. Most professional women’s soccer players still quit before beginning families. This goes for stars like Mia Hamm, Julie Foudy, and Abby Wambach. It’s also true for the players who aren’t stars or on the national team.

With every successive professional league, salaries for non-national team players have gotten lower, in an attempt to keep expenses down and keep the league alive. The U.S. Soccer Federation subsidizes the NWSL, covering the salaries of the national team players. The non-national team players receive between $6,842 and $37,800, but most make nowhere near that top figure. In 2015, the league has seen a slew of retirements: “One-by-one this offseason, National Women’s Soccer League players opting to retire possessed a common trait: They are women in their mid-20s, and are either at their athletic peak or nearing it,” writes Jeff Kassouff for NBC Sports. It’s difficult to make it in the league in the first place—throw in motherhood, and for most, it’s impossible.

The NWSL commissioner Jeff Plush commented on the early retirements:

Anytime you have young players retiring it gives you reason to ask why. I would say the numbers are not that large relative to the entire player pool. I think we have to be careful and try not to evaluate our player pool through the prism of other leagues and especially men’s leagues. Women are different. Women are quitting for a variety of reasons, including having families. Those are things to be celebrated. If someone wants to go back and get a master’s degree to take a teaching job, those aren’t negatives. The question is, are we doing what we can do to build a platform for our players to stay in our league for as long as they choose to. That’s what we’ll continue to work on.

Jenny Anderson-Hammond is one professional player who retired upon learning she was pregnant. While she’d played for New Jersey’s Sky Blue F.C. in the WPS in 2009, she, like many of the other players, lived in an extended-stay hotel and worked a second job as a coach, fighting rush hour to make it back for team training. She saw her new husband, a teacher, once a month. These weren’t the easiest circumstances, yet she thought it was worth it to continue to play the game she loved. But a child was different. In 2013, the third women’s pro league was starting up, and Hammond had every intention of trying to make the roster. Half-Filipino, she was also slated to help the Philippines national team qualify for the World Cup. But when she found out she was pregnant, and she opted to stop chasing the soccer dream. “I had a family to support now, I couldn’t do it financially,” she says. “I had to make a bigger contribution. I’d seen Christie (Rampone) and other players do it so I knew it was possible—but I don’t know how.”

Beyond Rampone, Cox, Boxx, and Rodriguez, there’s only one other mother in the NWSL—30-year-old Jessica McDonald, the only mom in the league who hasn’t played for the national team. But McDonald has made sacrifices, fought to make ends meet, and stayed in the game because—like Cox, Boxx, and Rodriguez—she too dreams of playing for her country.

Had a great time downtown. Even went to food carts. And a little play time, not sure who had more fun, son or hubby? pic.twitter.com/KDixhXFqeU

— Jessica McDonald (@Jess_Mac14) April 29, 2014

In 2010, McDonald assumed her career was over. She’d had a disappointing WPS season with the Chicago Red Stars, tore her patellar tendon, and found out she was pregnant. Game over, she thought. But in 2012, she was offered the chance to play for the Australian W-League side Melbourne Victory and relaunch her career. “I took that ticket and ran with it,” says McDonald. That meant leaving her new husband and baby for three months. “I felt fully attached to my family … leaving them behind was terrible,” she says. But her lifelong dream had been to make the women’s national team, to play in a World Cup. “After I had my baby, I didn’t want that to be an excuse, the reason I stopped going for it.”

In 2014, she was acquired by the NWSL Portland Thorns. Her husband, who worked a job in Arizona, didn’t come with her—he kept working to save money so they could eventually be together. McDonald became the Thorn’s leading scorer: She scored 11 goals, third-highest in the league, while her superstar teammates Christie Sinclair and Alex Morgan scored 13 goals between them. While she hoped her results on the field would earn her a call-up, that didn’t happen. She’s never been invited to a U.S. training camp, where players audition for the team.

Like Rodriguez, she too got unexpectedly traded. “It was a big adjustment for my family,” says McDonald. They’d planned on finally living together in Portland; her husband had enrolled in firefighter school. “We had worked so hard to get things set up, to get his career kicked off,” she says. “He’s been supporting me for so long and once again, because of my career, he had to put his own on hold. You don’t know where you’re going to be tomorrow. It’s kind of hard to plan a future.”

It’s difficult to make it in the league in the first place—throw in motherhood, and for most, the balance is tipped toward retirement.McDonald and her family packed up and headed to play with the Houston Dash. Portland had a players-only policy at the apartment complex where they put up the Thorns—no significant others or families were allowed to live with the team, but McDonald talked them into letting her son stay, and eventually her husband, too. Houston, on the other hand, worked to accommodate McDonald—they found an apartment for the family and helped set up her husband with a job at the stadium.

On the field, McDonald has continued to excel—as of June 22, 2015, she had scored 5 goals, one goal shy of leading the league. “After having a child, my career just skyrocketed,” says McDonald. Post-pregnancy, her body got stronger and faster. “You have all that weight to kill off—you’re working 10 times harder.” When she ran 120-yard sprints, a standard fitness test in soccer, she clocked times that were two to three seconds faster than her pre-pregnancy times.

***

After a woman has gone through the process of creating and delivering a baby, how is her body different—and what impact does that have on her ability to run at full speed, to perform? In recent years, there’s been a theory gaining ground that having a child can actually boost your performance.

This discussion comes up most often in long-distance running, where improvements are easiest to track. Many runners experienced personal peaks after having a child. In 1984, the 27-year-old Norwegian runner Ingrid Kristiansen won the Houston Marathon five months after having her first child, then set the course record at the London Marathon four months later. In 1991, nine months after giving birth, the Scottish runner Liz McColgan blew away the competition in the World Championship in the 10,000 meters, winning by more than 20 seconds. In Feburary 2014, the Kenyan runner Mary Keitany broke the half-marathon world record, 15 months after giving birth. “I need to run well to give a good future to my son,” Keitany, 29, told the National Post.

Research on the physiological effects of pregnancy on elite athletes is unclear. Very few concrete studies have been done on performance changes in high-level athletes post-pregnancy. With so many variables—how the pregnancy went, how the birth went, whether there was a C-section—it’s difficult to have a controlled study.

Michelle Mottola, an exercise physiologist at the University of Western Ontario, told The Guardian in 2014 that she believes there’s evidence to suggest that “super mom strength” is more than a myth: “With all the physiological changes that occur during pregnancy, it’s not like you can turn the valve off and switch back to normal once the baby’s born. The postpartum period can potentially last up to a year afterwards ... scientific evidence suggests that, in some ways, she may find performance a bit easier during this period because of the changes to her heart and her lungs.”

Jim Pivarnik, a professor of kinesiology and epidemiology and the director of the Human Energy Research Laboratory, studies athletes during and after pregnancy. Like Mottola, he notes there may be changes in the body—such as a 60 percent increase in blood volume and a strengthened musculoskeletal system—that can benefit athletic performance in post-partum runners. But he also states that if there’s any physiological advantage, it ends after the first two months. While most mother-athletes he interviewed reported personal heights in physical performance, Pivarnik believes this is less physiological and more mental—stemming from an “I’ll show them” mentality.

Chris Lundgren, the author of Running & Pregnancy, saw her marathon times improve each time after she gave birth. She noted another aspect of the mental shift. “In the back of your mind when you’re running a marathon is: ‘This is nothing compared to labor,’” she says. “You have a totally different benchmark for pain.”

Whether these outlier athletes’ uptick in performance is credited to mental or physical changes, both Mottola and Pivarnik attach a caveat—every woman, pregnancy, and delivery is different.

***

During her pregnancy, Rodriguez gained 35 pounds and weighed almost more than her husband. “It was embarrassing,” she says. “And my muscles got ... gooey.”

Six weeks after giving birth, she was medically cleared to train—she had a post-natal physical therapist, a personal trainer, and a husband who was also a personal trainer. Her first day back in the gym, she was lightheaded, nauseous. “I thought, if I’m getting blurred vision and losing my footing just from lifting weights, what was going to happen when I hit the field?” Far from her pre-pregnancy fitness level, she started out playing with teenage boy club teams and youth national teams. Being on the field felt awkward—she had no strength, and her balance was off.

Every day, the U.S. fitness coach Dawn Scott sent her exercise regimes. Her parents watched the baby while she trained. She’d drop him off in the mornings, go work out, shower, come back, and be a mom. “I’d be pumping and breastfeeding, not sleeping, but I was so determined,” says Rodriguez. “I’d missed the sport for months and months ... I could not wait to get back.”

Her hard work paid off. In January, Rodriguez was invited to her first U.S. training camp since giving birth. Because her son wasn’t a good sleeper, she’d sleep in three-hour stretches at night before waking up the next morning to train. “And not just train, but train with the best players in the world. And not just train, but have to stand out,” she says.

Four months after getting back on the field, she lined up for one of the U.S. speed tests, a 40-meter dash—and to her shock registered the fastest time on the team. (She explained it with the fact that she had spent all winter preparing for the camp while other players had taken some time off.)

Four months after getting back on the field, Rodriguez lined up for one of the U.S. speed tests—and registered the fastest time on the team.Before the start of the pro season, she said goodbye to her husband and headed with her son Ryan to Kansas City, where she moved in with Lauren Holiday, a longtime U.S. teammate. Holiday’s cousin took care of Ryan during training sessions and games. Holiday helped out too: “She became his other mom—she’d play with him while I’d go pump, make baby food, or shower,” says Rodriguez. Ryan came along on road trips, and the entire Kansas City team took him in. “It was like having 20 aunties who wanted to play with him all the time.”

In the first game of the 2014 season, Rodriguez scored ... and she just kept scoring after that. Logging 13 goals in the regular season, she was the second-leading scorer in the league. She led her team to the league championship, where she faced none other than Seattle, the team who had traded her. And Rodriguez scored both goals in the 2-1 victory.

Rodriguez fully believes being a mother has made her a better player. Kicking a ball is no longer her number one priority, and that, somewhat counter-intuitively, has helped her career: “As a forward, you’re required to be composed in front of the net. I think the reason why I scored so many goals this year is because I was more relaxed. I know now that my son is what’s important in my life. Soccer, I just play for the enjoyment.”

Rampone also believes motherhood made her better on the field: “Before kids, as a player, you have a tendency to over-think stuff. You’ve got too much time on your hands—you sit there in the hotel room over-thinking, stressing out, imagining things. As a mom you can’t do that—you’re focused on your true problems. The real things. And that really helped my game.”

***

Of the four new mothers in the league—Cox, Boxx, Rodriguez, and McDonald—two made the 2015 World Cup Roster.

Cox wasn’t selected for the final 23. “I knew that if [it] doesn’t work out, I need to be OK with having to be done,” she told KUOW. “I think you have to be willing to let it go if you’re going to get pregnant.” Cox continues to play for the Seattle Reign. “I’m having too much fun to be done.”

McDonald continues to hope that her success at the professional level will eventually lead to an invite from the national team. She now has her sights set on the 2016 Olympics. “I want to be able to tell my son that I went for it,” says McDonald. “I want him to be proud of his mom.”

Boxx and Rodriguez made the team, and have spent 2015 balancing motherhood and national camp. This often requires leaving their kids at home. “Ryan’s at that age where he’s not going to remember … but I remember,” says Rodriguez. “It’s super hard to let go of him when I go into camp. When I’m leaving, I’m crying … I’m super emotional when it comes to my son and being his mom.”

Often, the kids do get to come to camp. U.S. Soccer supports the mothers by paying for nannies at training camps and tournaments. (This is not yet the international standard—each World Cup team with mothers has its own policy.) And the children’s presence is embraced—one U.S. Soccer video features players competing for the affections of Rampone’s youngest daughter on a road trip.

Beyond the effect of motherhood on elite athletes, there’s the effect of the elite athletes on their kids: Rampone’s daughters, Rylie and Reece, have traveled with the national team on and off since they were born: “They’ve gotten to see the world. And being with the team, they get to see and connect with different personalities.”

Both Boxx and Rodriguez think the chance to share the experience with their kids is worth the challenges. “Knowing my daughter’s at my games, it’s the coolest thing,” says Boxx. “Even though she’s too young to know what’s going on—just to have her there in the stands, to take her picture and to be able to say one day, you were there—you were a part of this experience.”

Rodriguez says, “I want Ryan to see me as somebody who can go after a gold medal, or a World Cup—I want him to be proud of me.”

Rampone, Boxx, and Rodriguez have all gotten onto the field in the 2015 World Cup. Only Reece is old enough to begin to understand the lengths her mother has gone through in order to be there. But all four kids are watching, absorbing the buzz of excitement as their mothers attempt to bring home the Cup.

***

In U.S. Soccer’s “Back Home” video series, Rampone heads into her New Jersey basement to give a tour of her 16 years worth of soccer memorabilia—she holds up a giant cut-out of herself in a professional soccer jersey. “This cutout actually saved me with Reece a couple of times when I had to step away,” she says, referring to the times she’d stick the cutout in front of baby Reece to console her.

Fast-forward to June 22, 2015. Before the USA’s game against Colombia in the knockout round, Reece once again looked up to a larger-than-life image of her mother: Rampone tweeted the picture of her daughter standing in front of the wall-sized poster of the U.S. team, alongside the caption “Game Face.” Reece’s pose is identical to her mom’s—arms folded, face defiant.

Game Face! #USAvCOL #SheBelieves pic.twitter.com/MdbeBvfxCR

— Christie Rampone (@christierampone) June 22, 2015

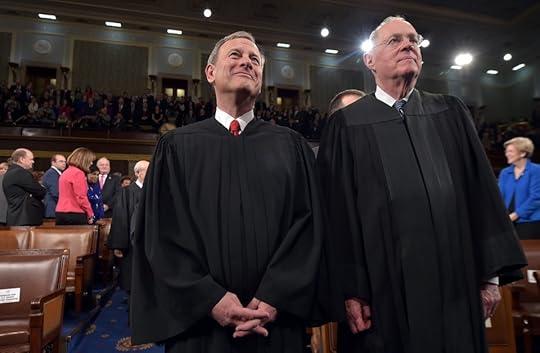

A New Right Grounded in the Long History of Marriage

On Friday, when the United States Supreme Court recognized a constitutional right to marriage, it turned to history to explain its decision. “The history of marriage as a union between two persons of the opposite sex marks the beginning of these cases,” wrote Justice Anthony Kennedy, on behalf of the 5-4 majority. “To the respondents, it would demean a timeless institution if marriage were extended to same-sex couples.” But, he added, this view of marriage as timeless and unchanging was contradicted by an abundance of scholarly work. “The history of marriage is one of both continuity and change.”

When the Supreme Court met last April for oral arguments in Obergefell v. Hodges, the justices spent a lot of time talking about past. The question seemed to be—on whose side is history? Can a historical case be made for legalizing same-sex marriage, or would this be some kind of radical break with thousands of years of legal and cultural history of matrimony?

The history lesson began from nearly the first moment of oral arguments. Plaintiff’s attorney Mary Bonauto introduced her position, fielded a quick question from Justice Ginsburg, then argued that her client and a “whole class of people” were being denied the right to “join” in an “extensive government institution.” Chief Justice Roberts jumped in, “Well, you say join in the institution. The argument on the other side is that they're seeking to redefine the institution. Every definition that I looked up, prior to about a dozen years ago, defined marriage as unity between a man and a woman as husband and wife. Obviously, if you succeed, that core definition will no longer be operable."

Roberts was just the beginning. Justice Stephen Breyer, assumed to be sympathetic to the plaintiffs, also referenced thousands of years of marriage tradition that didn’t include same-sex couples. Anthony Kennedy and Antonin Scalia cited anthropological evidence for marriage customs, both ancient and contemporary. Justice Samuel Alito talked about ancient Greece and Plato. Bonauto was forced to concede, “I can’t speak to what was happening with the ancient philosophers.”

Fortunately, there are people who can speak to the ideas of ancient philosophers. I consulted Anise Strong, an assistant professor of history at Western Michigan University. Strong, the author of the forthcoming book Prostitutes and Matrons in the Roman World, studies gender and sexuality in the ancient world and the use of ancient history in the modern era. She notes that despite the approval by Plato and his social circle of “short-term, possibly unconsummated (‘platonic’) relationships between older man and teenage boys whose beards had not yet grown,” it’s true that ancient Greeks did not have gay marriage. Instead, they favored:

Closely endogamous marriages between uncles and nieces (and sometimes half-siblings), marriages in which women retained almost no property rights or independence and were regularly both physically segregated and violently abused, and a system in which marriage was designed explicitly to increase and safeguard the property of closely related men while encouraging the production of definitely legitimate male heirs to those men through tightly restricting access to their wives.

Strong also notes that across the great sweep of marriage across human history, societies have often embraced polygyny.

In other words, given that most Americans would find abhorrent the types of marriages of which ancient Athens approved, why should they care whether they would have disapproved of gay marriage? The history of ancient marriage is fascinating and important, but by citing Plato’s stance on gay marriage, the conservative justices are snatching out the one bit that’s useful to them, ignoring the broader cultural context. It’s using history to confirm biases.

In fact, when you really dig into the history of marriage, the only consistent feature is change. My own professional group, the American Historical Association, filed an amicus brief that leveraged the combined expertise of twenty historians of marriage. The AHA brief used examples drawn largely from American history to show that marriage has never been solely about procreation, with issues like property management taking center stage. Moreover, Ruth Karras, author of Unmarriages, told me in an interview that marriage has almost never been about joining one man and one woman, but instead about “two families.” In that sense, same-sex couples looking for equal protection under the law with respect to healthcare and property rights are pretty consistent with “traditional marriage.”

That is, if there even is such a thing as “traditional marriage.” Karras began studying the multiple forms of medieval marriage—or at least the socially-accepted and often semi-legal long-term forms of relationships—because of her frustration with the idea that, “there was some sort of time that we could go back and look at where marriage was this perfect ideal between a man and woman for purposes of reproduction or creating family. The Middle Ages clearly haunts that formulation.” In fact, Karras continued, for many medieval people, “traditional marriage didn't even exist. Yes, for aristocrats there was this system, but it's really not very possible to know much about how people without any money formed and possibly didn’t form their marriages. People seem to have this idea that until the 1960s in America, everybody was pro-marriage—in fact, in the Middle Ages a lot of people lived in other kinds of relations besides what was recognized formally as marriage.”

Karras likes to use “clerical marriage” as a good example of how social institutions change over time. During the later Middle Ages, the church refused to let priests marry. And yet, clerical marriages existed all over medieval Europe, and were often recognized by neighbors and local communities, although they had no legal standing, and non-birth parents had no rights over any offspring. She suggested this was a good analogy for the status of same-sex marriage in America over the last few decades, though it’s obviously rapidly becoming more legitimate. Today, of course, thanks to Protestantism and Orthodox Christianity, clerical marriage is more common than clerical celibacy among Christian populations, and even half of all Catholics worldwide think priests should be able to marry. “This kind of union, [once] grudgingly tolerated and informally recognized, is now formally recognized and tolerated,” Karras said.

Today, married status still confers major legal rights for partners, much as it did in past eras. But even that point of consistency indicates change. These legal benefits are adjacent to the real cultural center of marriage today—love. While the link between marriage and love dates back far into the recesses of history and literature, it was often marginal; the legal forms, particularly those affecting property, came first. Now, thanks to the popularization of romantic marriage in the 19th century, that relationship has flipped. In the words of historian Stephanie Coontz, “Love conquered marriage.”

On Friday, Kennedy cited the work of Coontz, and other historians, as he endorsed the continued evolution of marriage as an institution:

Decades of careful scholarship showing that the most constant element of marriage is change allowed the Court to decide that far from undermining the institution of marriage, some changes can actually strengthen it. I suspect that will be the case here.As women gained legal, political, and property rights, and as society began to understand that women have their own equal dignity, the law of coverture was abandoned...These and other developments in the institution of marriage over the past centuries were not mere superficial changes. Rather, they worked deep transformations in its structure, affecting aspects of marriage long viewed by many as essential…These new insights have strengthened, not weakened, the institution of marriage.

Books by Friends: Skyfaring, America's Moment, Republic of Conscience

As in several previous installments in this series, I disclose for the record that I have some connection with the authors of these books. But as in the previous cases, these are all books I’d recommend whether or not I’d known their authors. I’m mentioning them with deliberate brevity, both to encourage you to find out more yourself and because if I waited to do "real" write-ups I'd take longer to get around to it.

Seriously, these are books you will be glad to have read.

An elegant description of flight (Penguin

An elegant description of flight (PenguinRandom House)

1) Skyfaring, by Mark Vanhoenacker.

Like many readers, I was sorry to hear last week of the death of James Salter. His books Light Years and Burning the Days are among those I remember most clearly for their grace of expression and power in conveying particular moods.

But Salter was also interesting to me because of his career as a Korean War-era military pilot and his ongoing interest in aviation. The one time I met him, at a conference in Austin 15 years ago, we spent most of the time talking about flying. First he grilled me on how much experience I had. When I told him, he said, “Well, if you’ve made it this far, you’ll probably live.” Then we talked about why it was that flight, and the ability to see the world from a perspective humanity had only dreamed of until the past century, had lost its sense of magic and the literary fascination it held in the days of Beryl Markham (West With the Night) and Antoine de St. Exupéry (Vol de Nuit).

Apart from Salter, my friend and one-time Atlantic colleague William Langewiesche has probably done more than any other writer to sustain the idea that traveling “Inside the Sky” should be seen as a deeply interesting pursuit and a complement to a literary sensibility. Now Mark Vanhoenecker makes a dramatic, elegant addition to this small group with Skyfaring. Vanhoenecker is a commercial airline pilot—and at the words “commercial airline,” the spirit sinks. Therefore it is all the more remarkable that this book lifts the thoughts and spirits. It is a highly informative book about how the world looks from the cockpit of a modern jetliner, but it also is a truly beautiful book about possibilities and limits, connections and separations, surprises and habituations, and other long-standing themes of literature.

(And, by the way, I don’t know the author, but I did a blurb for the book and thus put it in the “by friends” category.)

An argument that better economic times are ahead

An argument that better economic times are ahead(W. W. Norton & Company)

2) America’s Moment, by the Rework America team for the Markle Foundation.

Many of the reports Deb Fallows, John Tierney, and I have done in our American Futures travels amount to documentation of the country’s response to changed economic circumstances. Everyone knows about the damage done by the most recent crash, about the opportunities closed off by global competition or technological shifts, about the bad ways in which the early 21st century resembles the original Gilded Age.

What has surprised us in our travels is evidence of the efforts—by individuals, by companies, by communities with their schools and civic organizations, by states and the entire nation—to find opportunities in the changed circumstances, as has of course happened after the great dislocations of the past. The Rework America team, coordinated by Philip Zelikow (who was director of the 9/11 Commission and wrote its best-selling report), addresses the question of opportunities created, versus opportunities lost, in a more systematic way than we have been able to do—and argues that a despairing, closed-horizons mood is exactly the wrong response to the next stage of economic creation. It is especially powerful in examining the history of America’s stages of growth and stagnation and applying those lessons to the years ahead.

I took part in two meetings of the working group and submitted some ideas. (And the book mentions some examples we have reported on.) But if I’d had nothing to do with the project I’d still say that this book is a clear-headed, economically sophisticated, historically grounded, vividly argued guide to the next stage of American growth. You can see an interesting video narrated by Robert Wagner here.

Has politics gone bad? You don’t know the half

Has politics gone bad? You don’t know the halfof it. (Penguin U.S.A.)

3) The Republic of Conscience, by Gary Hart.

Who is your nominee for the public figure who has been right most often, over the longest period of time, on the broadest questions of national security? I propose Gary Hart.

From his anti-Vietnam War stands in the 1970s, through his leadership of Congressional defense-reform efforts in the 1980s, to his warning in the late 1990s on the Hart-Rudman Commission about the risk of terrorist attack, to his prescience about the imperial overreach of the past dozen years, Hart has been strikingly right more often, and embarrassingly wrong less often, than other public figures I can think of.

He has become a prolific author in his post-elective-politics years. His latest book is a jeremiad, but an informed and precise one. He argues that what has gone wrong in national politics is even worse than you think, and a lot of it comes down to the untrammeled role of money and the expansion of the security state. You’ve heard other people say this: What’s different in Hart’s analysis is the way he grounds his argument in the real things he has seen through a real career of running for office and seeing policy made. Practical point: If you’re inspired by the pleas-for-change speeches by Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren, or for that matter by Marco Rubio, by all means read this book.

***

Previously in the “books by friends” series, a mention of Erik Tarloff’s All Our Yesterdays; Jack Livings’s The Dog; Michael Zakkour’s China’s Super Consumers; and Mark Bernstein’s The Tinderbox Way last fall. Then a few months ago, another report covering Robert Wachter’s The Digital Doctor; Gabriel Weimann’s Terrorism in Cyberspace; Andrew Guthrie Ferguson’s Why Jury Duty Matters; Sven Beckert’s Empire of Cotton; and Patrick Evans’s Grand Rapids Beer.

June 25, 2015

The Supreme Court Barely Saves the Fair Housing Act

As the Supreme Court term winds down, there is discussion whether the Court is in some way drifting to the left. That narrative may take on additional steam after Thursday’s decisions—King v. Burwell, negating a far-right challenge that might have destroyed the Affordable Care Act, and Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. Inclusive Communities Project, an attempt by the state of Texas to radically scale back the scope of the federal Fair Housing Act.

Both challenges failed Thursday. But it would be a mistake to read Inclusive Communities as a “liberal” decision. Although four justices clearly wanted to radically cut back the Act, the majority—Justices Anthony Kennedy, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan—signed on to an opinion narrowing it in crucial ways.

This was no ringing victory for civil rights; it was a near-death experience that may produce health problems for the Act down the road.

Related Story

The Supreme Court Walks a Fine Line on Race

The issue in Inclusive Communities was whether the Act allows plaintiffs only if they can show that a government agency or private actor in renting, selling, or otherwise making housing available on the basis of race, intended to discriminate on the basis of race, or whether the Act also forbids acts that have a “disparate impact” on housing opportunities. Disparate impact means that some policy, adopted for a non-racial reason, might end up burdening minority-housing opportunities more heavily than those provided to whites; if so, the policymaker would be required to justify the policy to a court on grounds other than race.

In this case, for example, the plaintiffs produced evidence that the Texas Housing Department awarded tax credits to more developments in poor, minority areas than in areas with majority-white population. The effect, they argued, was to lock minorities into certain parts of the Dallas metro area, perpetuating and extending the area’s segregated housing patterns. The department argued that its decisions followed a complicated set of criteria generated in conjunction with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and including questions like the cost of land and construction (lower in low-income areas) and “community revitalization,” meaning the economic boon that development can represent to poorer areas. The federal district court held that the agency’s non-racial justifications were not sufficient. The Court of Appeals reversed, arguing that disparate-impact claims are permitted but that these plaintiffs had not made their case.

Before that case could be reheard, however, the state of Texas asked the Supreme Court to take a radical step by reinterpreting the FHA to bar disparate-impact claims altogether. Every circuit court of appeals that had considered the issue had held that the Act permitted disparate-impact claims. But the high court granted review. The Court had granted review in two earlier cases, but both had settled at the last minute. The Texas case finally teed the issue up squarely.

“The Court acknowledges the Fair Housing Act’s continuing role in moving the Nation toward a more integrated society.”From a distance, the result in Inclusive Communities looks like a win. Writing for himself and the four moderate-liberals, Justice Kennedy explained that the disparate-impact interpretation had a lot going for it: it tracks two other Court precedents concerning the employment-discrimination provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act; it has been upheld by every court of appeals to consider the issue; Congress readopted the Act in 1988 with language that seems to recognize disparate-impact liability in all but a few categories of cases; and it has become a part of the landscape of urban planning, such that many large cities—including San Francisco, New York, Boston, and Baltimore--submitted a brief asking the Court to leave the Act alone. Eliminating disparate-impact claims would thus destabilize not only other areas of civil-rights law, but also a great deal of city planning. “The Court acknowledges the Fair Housing Act’s continuing role in moving the Nation toward a more integrated society,” Kennedy concluded.

But the majority opinion is less a ringing reaffirmation than a stern warning—claims like those brought by the plaintiffs in this case, Kennedy wrote, actually might raise “serious constitutional questions.” That is, the use of statistics, no matter how persuasive, to show disparate impact without additional evidence creates a danger of “abusive disparate impact claims” that may hobble local governments and developers. Without strict safeguards, the opinion said, “disparate-impact liability might cause race to be used and considered in a pervasive way and ‘would almost inexorably lead’ government or private entities to use ‘numerical quotas.’”

Kennedy concluded that “we must remain wary of policies that reduce homeowners to nothing more than their race.” And the implication is that anything outside the “heartland” of disparate-impact liability—that is, “zoning laws and other housing restrictions that function unfairly to exclude minorities from certain neighborhoods without any sufficient justification”—would be dangerous territory.

These particular plaintiffs, the opinion made clear, almost certainly must lose on remand. Disparate impact lives on. But the lower courts have plenty of ammunition in this opinion to use against any novel use of the FHA.

If the result seems “liberal,” it is only in contrast to the dissenting opinions, which are truly radical—contemptuous both of judicial precedent and the history of executive enforcement of civil-rights laws over the past half-century. Justice Clarence Thomas, writing for himself, urged the court to begin overturning all those precedents—especially the case that originated the theory of disparate-impact liability, Griggs v. Duke Power, which used it to invalidate a neutral-seeming employment policy that had the effect of trapping black workers in laborers’ positions. The Civil Rights Act, Thomas said, didn’t justify the decision; the Court had relied on a deceitful bunch of bureaucrats at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, who schemed to enlarge the scope of the law—and their own power—by hoodwinking the Court. It is a striking argument, especially when made by the former head of the EEOC—one who, during his tenure, had tried to reorient the Commission away from the role it had played in the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Thomas concluded with a strange set of musings about racial disparities in general. Disparity is the way of the world. He quoted conservative economist Thomas Sowell to the effect that some minority groups end up running the economies of entire nations: “the Chinese in Malaysia, the Lebanese in West Africa, Greeks in the Ottoman Empire, Britons in Argentina, Belgians in Russia, Jews in Poland, and Spaniards in Chile—among many others.” Besides, he said, “over 70 percent” of players in the NBA are black.

The principal dissent, by Justice Samuel Alito writing for Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Antonin Scalia, is, a bit less eccentric but equally radical. The precedents are not worthy of respect, Alito argued. Congress may have re-enacted the Act in 1988, but its changes didn’t mean everyone supported DI; the Reagan administration had said the Act didn’t allow DI claims. HUD, which issued regulations supporting DI, was actually trying to manipulate the Court rather than expressing its “’fair and considered judgment.’”

Like Thomas, Alito pointed out that disparities are everywhere—not only in the National Football League but in the Office of the Solicitor General, which mostly sends young lawyers to argue in front of the Court.

With one more vote, these two screeds would have created a gaping hole in the fabric of civil-rights law, with malign effect far beyond housing. That Kennedy rejected that course is an occasion for relief. But if you think that the great danger facing our country is too much separation rather than too much equality, Kennedy’s opinion is no cause for celebration. It is a slow and measured step to the right, rather than a radical one. But its direction is clear.

The Anticipated Spider-Man

When is a reboot not a reboot? When it happens every five years.

In 2010, the reaction to the recasting of Spider-Man with Andrew Garfield was fierce enough to inspire charged Internet campaigns. On Tuesday, the role changed hands again, going to the 19-year-old English actor Tom Holland, who will appear in the third Captain American movie next year before getting his own film in 2017. This time, the news was greeted with shrugs. Holland is by all accounts a talented young actor, and since he’s actually a teenager, he’s perhaps a better fit to play the comic books’ high-school student Peter Parker than Garfield or Tobey Maguire, both of whom were in their mid-to-late 20s when they took on the role. Still, Holland will be the third onscreen Spidey in less than 10 years, and is by far the least familiar face, raising the question of whether audiences have the appetite to watch this particular origin story again.

Related Story

Could Sony and Marvel's Deal Mean a Non-White Spider-Man?

Holland’s casting is a by-product of corporate negotiations: Marvel Comics owns the film rights to most of its characters, but Spider-Man is in the hands of Sony, which has produced two franchises since 2002—a trilogy from director Sam Raimi starring Maguire, and two films from Marc Webb starring Garfield. Now, thanks to a unique production deal, Spider-Man can exist in the shared Marvel Cinematic Universe, but Sony can keep the profits from his appearances: Starting next year, fans can watch Spider-Man work with Iron Man and Captain America. But box-office returns show that as the superhero has been recast and rebooted, audience loyalty has fallen dramatically—and the lukewarm reaction to Holland’s casting is perhaps further proof of the same downward slide.

The recasting will also be the biggest test yet of whether audiences care more about characters or actors—and there’s already evidence for the latter. Garfield’s performance as Spider-Man was generally popular with critics (the films, less so), but The Amazing Spider-Man took only $262 million domestically, and its sequel barely pulled in $200 million (less than its $255 million budget). That marked a huge drop from the $403 million the first Spider-Man movie earned, and these depressed receipts came in an era of inflated returns for every Marvel box-office bonanza. Iron Man the comic-book character is perhaps one-tenth as popular as Spider-Man, but when it comes to the movies, that doesn’t seem to matter.

The simplest way to explain it is star power, but a better way might be brand familiarity. Robert Downey Jr.’s performance as Iron Man in the many Marvel films is crucial to their success, but the longer he’s in the role, the harder it’ll be to imagine someone else taking the job. That’s why he’s getting paid $40 million to appear in Captain America: Civil War, a film he’s not even starring in, with another bonus built into his contract if the movie does better than its predecessor (which, given his involvement, it certainly will). Marvel will have to continue backing up the truck for any future Avengers installments he signs on for, and despite its reputation as a frugal company, it’ll happen—replacing him might generate the same loss of recognition and viewer interest Spider-Man is currently suffering from.

Box-office returns show that as the superhero has been recast and rebooted, audience loyalty has fallen dramatically.Can the brand be rescued? Given the lack of interest in Holland’s casting, it doesn’t appear likely. In 2003, there was a frenzy over rumors that Tobey Maguire couldn’t film a Spider-Man sequel because of a back injury and that Jake Gyllenhaal would take his place, a concept that seemed near-sacrilegious after Maguire’s work had been so well-received. But Maguire recovered, and the rumor became a weird piece of Hollywood lore. In 2010, the comedian and actor Donald Glover floated the idea that maybe he could replace Maguire in the Amazing Spider-Man reboot, and furious debate broke out again over whether Peter Parker could be played by an African American actor. This evolved into a larger debate of why comic-book fans are so reactionary about such a concept.

The Sony deal seemed to give Marvel an opportunity to change course and cast a non-white actor in the role. With audiences clearly tired of Peter Parker, perhaps the new Spider-Man could have been Miles Morales, a Black Hispanic character who was created in the comics partly as a response to the Glover controversy. After all, an onscreen portrayal of Morales would have gotten around a contract requirement discovered in the Sony hack that stipulated Peter Parker had to be white and heterosexual. Whether or not that option was seriously considered, Holland (who is white) was the final choice.

Like Robert Downey Jr., he will crop up in Captain America: Civil War next year, perhaps as a way to get around re-telling the Peter Parker story for the third time in recent memory—if Spider-Man just shows up onscreen a fully formed hero, it’s likely audiences will play along. After that, there’ll be yet another solo adventure for Spidey, with another new ensemble of family members, love interests, and villains to clash with, and another indie director (Jon Watts) being thrust into the spotlight. Will serving as a cog in the larger Marvel system help box office totals rebound to their former heights? It’s uncertain. But if not, Spider-Man will serve as the first example of something that’s bound to start happening more often as current stars get superhero fatigue and retire: that rebooting with a new actor won’t be enough to guarantee audiences keep coming back for more.

Churches Are Burning Again in America

“What's the church doing on fire?”

Jeanette Dudley, the associate pastor of God's Power Church of Christ in Macon, Georgia, got a call a little after 5 a.m. on Wednesday, she told a local TV news station. Her tiny church of about a dozen members had been burned, probably beyond repair. The Bureau of Alcohol, Firearms, and Tobacco got called in, which has been the standard procedure for church fires since the late 1960s. Investigators say they’ve ruled out possible causes like an electrical malfunction; most likely, this was arson.

The very same night, many miles away in North Carolina, another church burned: Briar Creek Road Baptist Church, which was set on fire some time around 1 a.m. Investigators have ruled it an act of arson, the AP reports; according to The Charlotte Observer, they haven’t yet determined whether it might be a hate crime.

These fires join the murder of nine people at Charleston’s Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church as major acts of violence perpetrated against predominantly black churches in the last fortnight. Churches are burning again in the United States, and the symbolism of that is powerful. Even though many instances of arson have happened at white churches, the crime is often association with racial violence: a highly visible attack on a core institution of the black community, often done at night, and often motivated by hate.

As my colleague David Graham noted last week, the history of American church burnings dates to before the Civil War, but there was a major uptick in incidents of arson at black churches in the middle and late 20th century. One of the most famous was the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, which killed four girls. Three decades later, cases of church arson rose sharply. In response, in 1995, President Bill Clinton also set up a church-arson investigative task force, and in 1996, Congress passed a law increasing the sentences for arsonists who target religious organizations, particularly for reasons of race or ethnicity. Between 1995 and 1999, Clinton’s task force reported that it opened 827 investigations into burnings and bombings at houses of worship; it was later disbanded.

In recent years, it’s been harder to get a clear sense of the number of church fires across the country. The National Fire Protection Association reports that between 2007 and 2011, there were an average of 280 intentionally set fires at houses of worship in America each year, although a small percentage of those took place at other religious organizations, like funeral homes. One of the organization’s staffers, Marty Ahrens, said that tracking church arson has become much more complicated since reporting standards changed in the late ‘90s. Sometimes, fires that are reported to the National Fire Incident Reporting System are considered “suspicious,” but they can’t be reported as arson until they’re definitively ruled “intentional.” Even then, it’s difficult to determine what motivated an act of arson. “To know that something is motivated by hate, you either have to know who did it or they have to leave you a message in some way that makes it very obvious,” she said. “There are an awful lot of [intentionally set fires] that are not hate crimes—they’re run-of-the-mill kids doing stupid things.”

The investigations in North Carolina and Georgia are still ongoing, and they may end up in that broad category of fires of suspicious, but ultimately unknowable, origin that Ahrens described. But no matter why they happened, these fires are a troubling reminder of the vulnerability of our sacred institutions in the days following one of the most violent attacks on a church in recent memory. It’s true that a stupid kid might stumble backward into one of the most symbolically terrifying crimes possible in the United States, but that doesn’t make the terror of churches burning any less powerful.

The Supreme Court Walks a Fine Line on Race

The Roberts court has had a lot to say about race. It upheld a Michigan ban on affirmative action for university admissions. It struck down a key provision of the Voting Rights Act, arguing that laws addressing the South’s history of racial discrimination were no longer needed. And it nixed voluntary school-desegregation plans that assign students to schools based on racial quotas.

But the court isn’t blind to the effects that decades of discrimination have had on minorities in this country, as became evident Thursday in its 5-4 decision upholding the “disparate-impact” standard of the Fair Housing Act. That standard allows groups to challenge policies that adversely affect minorities, that, for instance, segregate them in high-poverty, high-crime areas of town. Discrimination doesn’t have to be intentional to be unlawful, the court found.

The case was brought by a Dallas-area non-profit, the Inclusive Communities Project, who argued that the Texas Department of Housing and Community Development had approved housing projects predominantly in high-poverty, minority neighborhoods, a policy that had a “disparate impact” on minorities.

The court agreed, writing that disparate-impact claims have proven useful across the country as a way to combat discrimination that has gotten more subtle since the civil-rights era.

Recognizing disparate-impact liability “permits plaintiffs to counteract unconscious prejudices and disguised animus that escape easy classification as disparate treatment,” Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote, in his opinion for the majority. “Disparate-impact liability may prevent segregated housing patterns that might otherwise result from covert and illicit stereotyping.”

The decision was hailed as a win for civil-rights groups, who had argued that disparate-impact claims are the only way to remedy policies that lead to segregation. But it’s important to note that in this decision, the Supreme Court did not approve compulsory integration. In fact, Kennedy’s opinion specifically warns that policies that integrate housing by race quotas are unconstitutional. Instead, the ruling allows groups to continue to challenge the policies that perpetuate segregation, not segregation itself. The distinction may seem small, but it’s important.

As I’ve detailed before, the Inclusive Communities Project argued that the points system Texas formerly used to award low-income-housing tax credits to developers favored building projects in high-poverty areas, isolating poor, minority residents in poor, minority neighborhoods. Social scientists say this makes it more difficult for families to escape poverty and to access the resources, such as good schools and jobs, that they would be available in more affluent areas. But under this ruling, a remedy could not simply order the state to build housing projects for minorities in white areas. Instead, a remedy would have to address the policy guiding how tax credits are assigned, taking into account whether that policy as a whole perpetuates segregation (In 2010, for instance, a District Court ordered Texas to change how it awards tax credits, which it did).

When courts find remedies in disparate-impact cases, they should “concentrate on the elimination of the offending practice” that leads to arbitrary racial discrimination, Kennedy writes.

In that way, the decision is in line with the Parents Involved decision about school segregation, said Andrew Scherer, the policy director of the Impact Center for Public Interest Law at New York Law School.

“Inclusive Communities and Parents Involved are not about quotas, they are about the obligation to be aware of the consequences of government and private action, and to avoid actions that have discriminatory impact,” he said.

The remedy that Texas came up with back in 2010 as a result of the lawsuit was, in fact, race-neutral, a giddy Mike Daniel, the lawyer for the Inclusive Community Project, told me on the phone.

“This says you have to give equal points to projects located in high income and low-poverty areas,” he said. “There’s no race there. And it did, in fact, work.”

After the state changed its formula, developers proposing projects in high-opportunity areas received more points than they had before. Since then, more developers have built tax-credit developments in the suburbs, Betsy Julian, the executive director of Inclusive Communities, told me.

Fearing legal action, Dallas-area cities with predominately white populations, including Frisco and McKinney, also agreed to build affordable properties in the last few years. Though Inclusive Communities had to fight “tooth and nail” to get these projects built, “what you’ll see is a lot of the fears that people had with regards to the effect of the project on the value of their homes didn’t really have merit,” Julian said. One of the projects built because of an Inclusive Communities is in Sunnyvale, a Texas town that banned multifamily units and fought multiple court orders to allow them. D Magazine recently called it “the whitest town in north Texas.”

Still, Justices Thomas, Scalia, Alito, and Roberts heartily dissent with the decision. In a separate opinion, Justice Thomas reminds the court that racial imbalances don’t always disfavor minorities—Chinese were minorities in Malaysia, for instance, but still controlled the industry in that nation.

Furthermore, “This Court has repeatedly confirmed that ‘racial balancing’ by state actors is patently unconstitutional,’” Thomas writes.

But the majority does not see the policies behind Inclusive Communities as “racial balancing,” and indeed, warns against such policies. Instead, it allows housing developers to work with states to show that certain projects serve a valid interest, whether it be rejuvenating a depressed neighborhood or creating new housing for minorities in a wealthy area.

“The [Fair Housing Act] does not decree a particular vision of urban development; and it does not put housing authorities and private developers in a double bind of liability, subject to suit whether they choose to rejuvenate a city core or to promote new low-income housing in suburban communities,” Kennedy writes.

Many housing advocates still worry that this ruling will lead to less spending on housing in high-poverty, inner cities that need the most help.

“They're going to leave the neighborhood-based programs in the dust,” Mark Rogers, the executive director of Guadalupe Neighborhood Development Corporation, an East Austin-based housing group, told me.

Indeed, some Austin projects built before the Inclusive Communities lawsuit that have helped to revitalize high-poverty neighborhoods would not have won tax credits now, Julian Huerta, the deputy executive director of Foundation Communities, an Austin tax-credit developer, told me. M Station, a project approved in 2009 and located in East Austin, would have lost in the tax-credit process to another Foundation Communities development in Austin’s wealthy west side, called Southwest Trails.

This was also a concern expressed by the minority in the Supreme Court case. Frazier Revitalization Inc. had filed a brief arguing that recognizing disparate-impact claims could limit its goal of bolstering a high-poverty neighborhood. Giving credits to wealthy areas violates “the moral imperative to improve the substandard and inadequate affordable housing in many of our inner cities,”the brief argued.

Failing to improve substandard housing could also be argued to have a “disparate impact” on minorities, Justice Alito argues. The decision leaves it up to HUD to decide which policies adversely affect minorities, and which don’t. But that plan is too vague to work.

“The effect of these regulations, not surprisingly, is to confer enormous discretion on HUD—without actually solving the problem,” he writes.

But John Henneberger, an affordable-housing advocate in Texas, says there is a way to balance both concerns, and the court’s majority understood that. At the end of the day, this case is less about race, he said, than it is about choice.

“There needs to be a balance, and everybody acknowledges that, between revitalization and creating choices in other areas,” he said. “What it means is that a state like Texas cannot deny applications, cannot steer all of its affordable-housing stock into the poorest and most racially segregated parts of the city. It has to provide its citizens choice.”

‘You've Got a Hit’: How a James Taylor Album Finally Reached Number 1

James Taylor is going to number one, but not just in his mind—on the Billboard charts, too. The folky singer-songwriter notched the first top record of his career this week with Before This World.

Let’s contemplate how unlikely this is. Taylor’s first record came out in 1968. Sweet Baby James, generally considered his biggest record, only made it to No. 3. These days he seems more in demand as an ad-hoc Obama administration aide—performing at the 2012 Democratic National Convention or dispatched to France after a jihadist attack. He hasn’t had a song in the Hot 100 since 1988, and even that one only made it to No. 80. The song was “Never Die Young,” a synth-adorned lite-reggae period piece that makes one yearn for the Eagles, but Taylor was apparently wise to take its counsel.

Taylor’s late-career success isn’t a fluke, though. The collapse of the music business has been bad for many people, good for some musicians, and beneficial to cash-strapped listeners. But the changes have been great for the chart prospects of aging white dudes who play guitar-based rock.

In August 2014, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers notched the first No. 1 record of the band’s career with Hypnotic Eye. Two weeks earlier, Weird Al Yankovic did the same with Mandatory Fun. In October, Tony Bennett’s record with Lady Gaga topped the charts, but it wasn’t the first No. 1 of his decades-long career—he’d achieved that in 2011, with Duets II. (Bennett’s 54-year gap between his first chart appearance and first No. 1 is the only one to exceed Taylor’s 45-year wait.) 2011 was also the year in which Cake had its first No. 1 record, unseating Taylor Swift’s Speak Now. The sardonic Sacramento rockers didn’t go the distance, though—they were knocked off the chart the following week by, and I am not kidding you, the Decemberists.

What’s going on? Are these guys all having late-career renaissances? Probably not. You’d be hard-pressed to find many listeners who think any of the first-time No. 1 records cited above were the musical peak of the artists’ careers (except perhaps the Decemberists). What’s changing are patterns of buying in the music industry. Shaped by the Internet, music consumption has shifted away from albums, first to the buying of individual tracks, and now to streaming. The result was that the album chart was getting warped, offering an unrealistic impression of what was “popular,” even as the Hot 100 offered a more accurate look. In late 2014, Billboard changed the way it calculates the album chart to account for this:

The updated Billboard 200 will utilize accepted industry benchmarks for digital and streaming data, equating 10 digital track sales from an album to one equivalent album sale, and 1,500 song streams from an album to one equivalent album sale. All of the major on-demand audio subscription services are considered, including Spotify, Beats Music, Google Play and Xbox Music.

The shakeup seems to have had some effect. Just look three slots below Taylor on this week’s chart and you’ll see another Taylor—Taylor Swift, who has criticized royalty rates for streaming and is arguably the most influential person in the industry right now. In fact, the album chart is full of artists who are more of the zeitgeist: Scanning over the last few years of the chart, Swift, Beyoncé, Justin Timberlake, Adele, and Coldplay appear frequently, and they stick around for a long time—unlike Cake and Weird Al and co., who tend to drop out of No. 1 after just a week. The music those artists make—dancier, poppier, and more rhythm and synthesizer-based—is unquestionably closer to what contemporary music sounds like in 2015.

Even with the streams included, the number of albums being sold is way, way down. Taylor’s Before This World sold only 96,000 copies. That’s tiny; not long ago, selling fewer than 100,000 copies in week one wouldn’t land you anywhere near the top spot. Cake’s Showroom of Compassion, which hit No. 1, sold just 44,000 copies, the lowest ever for a top record. That’s not just a slide for the chart—it’s a slide for Cake, too. Two of the band’s previous records went platinum and a third went gold, but none of them got past No. 13 on the Billboard chart. Showroom topped the chart but hasn’t been certified gold.

It isn’t too hard to see what’s happening. The people who buy CDs and full-albums tend to be older, whiter, and more male than the general music-buying population. So when Tom Petty or, say, Bob Dylan (who’s had several No. 1 records in the last decade) or Bruce Springsteen (likewise) releases a new record, a small army of aging Boomers (and maybe their nostalgic children) emerges from its pop-culture cocoon and buys the new record in a shiny, shrink-wrapped jewel case. That burst of buying is enough to vault the disc to the top of today’s anemic sales numbers for a week. Just last week, the Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers was at No. 3 on the chart, in a fancy new edition with extra bonus tracks, which sure looks like a clever way to convince those same Boomers to buy a record they already bought on vinyl, on CD, and maybe even a third time in a previous souped-up CD edition. (And who knows, maybe on 8-track or cassette or Blu-Ray or Pono or MP3, too. These are the same fans willing to shell out hundreds of dollars to see the Stones on tour, after all!)

But since most of the music-buying population isn’t really into it, the sales peak and decline quickly—which is why most of these unlikely late-career No. 1s only last for a week. In other words, it’s great for James Taylor that he finally snagged a No. 1 record, but this is a sunny day that’s sure to end.

John Roberts Calls a Strike

Chief Justice John Roberts tossed a bucket of cold water on the arguments against tax subsidies under the Affordable Care Act on Thursday, and the deadly threat to Obamacare melted away like the Wicked Witch of the West. Writing for a 6-3 majority, Roberts, like the consummate A student he is, offered an excellent third-year administrative law exam answer to the questions the challengers posed.

There had been speculation that the crucial votes to save the Act would come from Roberts and Justice Anthony Kennedy, and that they would have to be lured across the Court’s liberal-conservative line by soothing words about the prerogatives of the states. But federalism was the dog that didn’t bark Thursday.

Instead, Roberts wrote for himself and five others—Justices Kennedy, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan. The challengers had argued that one clause of the Act limited its tax-benefits to “an exchange established by a state,” and so the subsidies could not be offered to those who purchased their plans on state-level exchanges established by the federal government. Roberts explained in his customary breezy style that this clause, read in context, referred to all American Health Benefit Exchanges established under the act, whether by the states themselves or by the federal government.