Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 400

July 2, 2015

In Praise of the Humble Workplace Safety Video

The jaunty synthesized music. The black-and-white flashbacks. The somber voiceover narration that warns of the dangers of “social media” and “serious physical injury” and “quid pro quo.” These are the staple elements of that most inelegant and unintentionally funny staple of corporate life: the workplace safety video.

Have you ever texted a friend while walking down a staircase? Failed to properly secure a lid while pouring hot coffee? Stood on an unstable chair to reach a high shelf? These are all habits that greatly concern corporate America, which is why, over the past four decades or so, the business of corporate-education films has grown into a multi-billion dollar industry in the U.S. alone. The poor production values and heavily emphatic warnings that define the genre have led to its being gently mocked in SNL skits about workplace diversity (“Let’s put that diversity truck in reversity”) and a whole episode of The Office that revolved around the hilarity of sexual-harassment awareness training.

Related Story

‘The More You Know’: There's More to Know

But while corporate-safety videos are often terrible by their very nature, they’re nevertheless an art form, tracing their roots back to the earliest PSAs and the pulpy social-guidance films of the mid-20th century. They’re also a business that, if nothing else, keeps struggling actors and wannabe filmmakers afloat while warning the workers of America that everything—a stapler, a high-heeled shoe, a compliment—can be dangerous when used without caution.

Today’s videos are typically entertaining only by accident, but it wasn’t always so. A 1969 production by Xerox Films is a masterpiece of comic timing and political incorrectness, using animation, sound effects, elaborate special effects, and a girl in a bikini to educate viewers about the fragility of the human body. “Here’s a pretty package of brittle bones, delicate organs, and precisely balanced chemicals, all bagged up in a sack of skin you can scratch a hole in with your fingernail,” the voiceover states, while a comely woman in a swimsuit covers herself in sunscreen. “Mark it ‘fragile.’” The film goes on to warn how everything can be hazardous to human health—bumblebees, typewriters, filing cabinets, and even a lone pencil left on the floor.

The idea that modern life is a nonstop parade of hazards and threats dates back to the late 1930s, when the actor Richard Massingham established an agency for the purpose of making short educational films, and thus birthed the public service announcement. One classic example is Coughs and Sneezes, a 1945 lesson on the dangers of not using a handkerchief. “Look here, what do you think you’re up to?” a plummy voiceover asks Massingham, who plays a bumbling, balding gentleman who can’t stop sneezing in crowds. “You’ve probably infected thousands of people already.”

In the U.S., this new genre was soon emulated by Sid Davis, a former stand-in for John Wayne who found a lucrative career in classroom-safety films. In the ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s, Davis produced more than 40 short movies intended to terrify American teens about all the awful things that could ever happen to them. In his sensationalist universe, so much as trying marijuana (“everything speeds up to 100 miles an hour”) leads to heroin addiction, crime, and—most significantly—ravaged looks. “It’s fantastic, it’s unbelievable, it’s terrible, but most importantly, it’s true,” the voiceover states.

Davis’s first film, The Dangerous Stranger, was made on a $1,000 budget (donated by Wayne), and ended up bringing in more than $250,000. Today’s safety films are more in the vein of Davis than Massingham, in that they earnestly seek to strike fear in the hearts of workers while proving extraordinarily profitable for the people who make them. Canada, in particular, has produced some of the most gruesome examples, notably Alberta’s $850,000 “Bloody Lucky” campaign in 2008, which featured a series of grisly videos showing terrifying footage of chemical burns in a bathroom, head trauma in a shoe store, and a foot mangled by a forklift truck at a construction site.

The Ontario Workplace Safety and Insurance Board campaign “Prevent-It” from around the same time also proved popular on YouTube, even while it prompted numerous complaints for being unnecessarily graphic and disturbing. The ads feature bloodied, zombie-like workers who lecture their colleagues on workplace safety. “This is no accident,” a character named Jim tells his boss after being impaled by two steel bars. “The company knows it’s against code to store too much weight up there.”

There are no statistics relating to whether safety videos actually decrease occurrences of injuries and fatalities in the workplace, but they definitely offer a healthy defense against one serious threat: lawsuits. “The U.S. Department of Labor estimates that organizations spend about $1 billion a week to compensate employees for safety-related job inquiries,” says a statement on the e-learning website Docebo. “Beyond this financial burden, organizations can also face litigation of they don’t train their employees on job-related safety issues.” In other words, expenditure on prevention is seen by many companies as infinitely preferable to expenditure on compensation after injury, which is why production companies are able to charge several hundred dollars per video. Popular titles on the website TrainingABC.com include “Dealing With Hazardous Spills” ($249), “Office Safety: It’s a Jungle Out There” ($495), and “Miracle on the Hudson: Prepare for Safety With Captain Sully Sullenberger” ($495).

Of course, potential threats/lawsuits in the workplace are no longer limited to physical injury, which is why many of the most expensive and popular current workplace safety films relate to subjects like sexual harassment, diversity, and the dangers of social media. “There’s that term again: ‘social media,’” says one actress in a film about the dangers of sharing private company information on Facebook. “Sounds like techno-Klingon to me.” While such videos are frequently greeted with lukewarm enthusiasm by the employees obliged to watch them, they’re a boon for actors and voiceover artists. “Even if you’re tired of ‘corporate America,’ you won’t get tired of being hired by them as a voiceover narrator for corporate work,” says the website of the production company Edge Studio. “Webinars, trade-show videos, podcasts, product demonstrations, sales videos ... corporations constantly need to hire voiceover talent.”

If nothing else, corporate safety videos provide late-career stability to public figures including the actor John Cleese, the college-football coach Lou Holtz, and the aforementioned Captain Sullenberger. They offer cheerful nostalgic flashbacks to the synthesized sound effects and dubious visuals of 1980s VHS specials. They’re easy to parody. And they allow corporations to protect themselves from expensive lawsuits while mandating that overworked employees take a break to watch movies at work. In a world full of horrifying dangers at every turn, perhaps it’s reassuring to know there’s nothing more quintessentially American than that.

Is Running for President Donald Trump's Worst Business Decision Yet?

Donald Trump’s run for the presidency is premised on one fact above all: He’s a fabulously successful businessman. And yet, paradoxically, running for president may be the most disastrous business decision he’s made—or, at the very least, his worst in a while.

The trouble started with Trump’s rambling announcement speech on June 16. “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending the best,” Trump said of immigrants to the United States. “They’re sending people that have lots of problems and they’re bringing those problems. They’re bringing drugs, they’re bringing crime. They’re rapists and some, I assume, are good people, but I speak to border guards and they’re telling us what we’re getting.”

Those comments have proved costly. On June 25, Univision announced it would not air the Miss USA pageant, which Trump partly owns, due to his remarks. The network’s five-year contract was reportedly worth $13 million. Trump, in typical fashion, sued Univision for $500 million.

On June 29, NBC followed suit. In a statement that launched a thousand bad “You’re fired!” headlines, the network that once aired Trump’s Apprentice and also Miss USA and Miss Universe said it was cutting ties and ending those programs. Trump says he’ll sue.

On Wednesday, Macy’s also announced it was dropping the Trump-branded line of clothing. "We are disappointed and distressed by recent remarks about immigrants from Mexico. We do not believe the disparaging characterizations portray an accurate picture of the many Mexicans, Mexican Americans and Latinos who have made so many valuable contributions to the success of our nation," Macy’s said. (Trump claimed the decision was his own.)

Late Wednesday, Serta announced it would no longer sell the Trump Home mattress, a product no one even knew existed. The city of New York is also reviewing its dealings with the magnate related to a $230 million golf course in the Bronx.

It’s unclear what the value of Trump’s NBC, Macy’s, and Serta deals were, but it’s a safe bet that altogether they’re a bigger deal to Trump than they are to any one of those corporations. Macy’s made $10 billion last year; NBC made more than a billion. Taking into account the value of the Univision contract, the total numbers seem likely to be somewhere in the tens of millions—hardly chump change, but not a serious hit for someone who claims to be worth $9 billion, as Trump does.

Of course, Trump’s $9 billion claim isn’t taken very seriously by very many people. In 2005, New York Times reporter Timothy O’Brien dug deep into Trump’s finances and estimated his actual value in the low hundreds of millions—enough to qualify him as “really rich,” in his words, but far, far short of billionaire territory. (Trump sued, naturally; he lost.) Trump also has a history of business troubles, to go along with some notable successes; he has filed for corporate bankruptcy four times and according to O’Brien had to ask his siblings to float him loans in the 1990s. They didn’t believe he’d repay them.

How did Trump get from $250 million, the upper end of O’Brien’s range, in 2005 to $9 billion today? It’s been 10 years, and an already-wealthy person can make a lot of money in 10 years, but that decade also included a massive economic slump, a crisis in real estate (putatively Trump’s core business), and a 2009 declaration of Chapter 11 bankruptcy by his casino group. One way to get to the $9 billion figure is that,

Does Iran Have Its Own Tom Cottons?

On Tuesday, the final deadline for concluding international negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program was extended again; after 18 months of talks, negotiators are working toward July 7 as a “soft deadline” to conclude a deal. Assuming that deadline is met, the conclusion of international diplomacy will set in motion distinct processes for implementing a deal in Iran and the United States.

Related Story

Tom Cotton: Obama's Iran Deal May Lead to Nuclear War

In March, U.S. Senator Tom Cotton sent an open letter, signed by 46 of his colleagues, to Iran’s leadership, advising the recipients that “you may not fully understand our Constitutional system,” and in particular Congress’s (debated) role in approving and instituting international agreements. The Obama administration has argued that since the deal would not be a formal treaty, it does not trigger the constitutional requirement that “two-thirds of the Senators present concur;” however, Congress does ultimately get to decide on crucial aspects of implementation, such as whether and when to lift sanctions on Iran.

But what’s required to implement the deal on the Iranian side? Are there domestic forces in Iran, similar to those in the United States, that could derail a deal even if the leadership wants it? Are there Tom Cotton equivalents in Iran’s parliament? I asked Farzan Sabet, a visiting fellow in the Department of Government at Georgetown and managing editor of IranPolitik, a website on Iranian political affairs, to explain what might happen in Tehran after talks end in Vienna.

Kathy Gilsinan: Say the negotiators actually strike a nuclear deal. How does the Iranian system process it domestically? Does parliament have to pass laws to implement it? Can the supreme leader simply reject it if he doesn’t like it?

Farzan Sabet: According to Article 77 of Iran’s constitution, international treaties, protocols, contracts, and agreements have to be ratified by parliament. In the case of the nuclear negotiations, this means that parliament has to ratify both a final agreement and other legal documents Iran may choose to accede to for the purpose of a deal’s implementation, like the International Atomic Energy Agency’s Additional Protocol, which would allow inspectors expanded access to verify Iranian compliance [with the agreement]. We should keep in mind that these things are not always as predictable in Iran as in other places. For example, parliament may choose to hand off a final agreement to the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC), a body which coordinates foreign and national-security policy decision-making between Iran’s main centers of power, for review and consultation before deciding for or against ratification.

The supreme leader can reject a deal if he doesn’t like it through an “executive command” (hokm-e hokumati). However, since the supreme leader is regularly briefed and consulted on the progress of the talks, the assumption is that any nuclear deal that is struck will already have his acquiescence and is unlikely to be rejected. If he does choose to reject it, he doesn’t have to do it directly. The supreme leader’s power pervades Iran’s political system and there are other ways to kill a deal that keep his hands clean.

Gilsinan: Like what?

Sabet: It depends on how Iran ultimately implements the deal domestically and the final procedures it establishes. Based on this, it could be through parliament, the president, the SNSC, etc. For instance, under a new law passed by parliament on the nuclear negotiations, the foreign minister and parliament’s National Security and Foreign Policy Commission are required to report to the legislature every six months about whether an agreement is being implemented in the “appropriate” manner. Procedures like this could give a pretext for parliament to derail an agreement months or even years down the road.

“The supreme leader’s power pervades Iran’s political system, and there are ways to kill a deal that keep his hands clean.”If Iran’s parliament were to derail the deal, however, the initiative probably wouldn’t come from the legislature by itself. This is different than in the U.S. where Congress could decide not to give the sanctions relief required in an eventual deal, and thereby derail it unilaterally. Parliament can theoretically try to dismantle an agreement after it is signed, but it is unlikely to do so as long as there is a regime-wide consensus that an agreement serves the national interest.

Gilsinan: When is the deal actually “done” within Iran? What other forces within the system could derail it after it’s signed?

Sabet: There are “known knowns” like parliamentary ratification, “known unknowns” like whether the supreme leader chooses to exercise his executive command, and then there are “unknown unknowns” like ad-hoc procedures adopted along the way which could provide opportunities to derail an agreement.

The important point to remember is that the decision-making process behind the nuclear negotiations has been so centralized in Iran that it’s not only President Hassan Rouhani negotiating, but the regime. The relevant foreign-policy and national-security power centers in Iran have had input in the nuclear negotiations decision-making process and operate under the supreme leader as final arbiter, so if an agreement is reached they are unlikely to try and derail it.

Gilsinan: Does Iran have its own Tom Cottons? What have they been saying about the negotiations?

Sabet: Yes and no.

Yes in the sense that there is a bloc of legislators who absolutely distrust their president and the other negotiating party, and think the current nuclear negotiations compromise their country’s national interests. One place you can find them in the Iranian parliament is the Persevering Front of the Islamic Revolution faction. One of the episodes that really stands out in terms of what they’ve been saying about the negotiations is when MP Mehdi Koochakzadeh confronted Foreign Minister Javad Zarif on the floor of Iran’s parliament in a yelling match and called him a “traitor” for his conduct of the talks. Otherwise it’s just been the usual “Death to America” chants from this small but vocal faction and nothing quite as memorable as Senator Cotton’s letter.

“‘Hardliners’ in the U.S. and Iran aren’t equivalent. In Iran, they aren’t powerful enough to block a deal by themselves.”No in the sense that Senator Cotton arguably represents the tip of the spear of a powerful coalition who opposes America’s current stance in nuclear negotiations. It’s probably not too far of a stretch to say that Senator Cotton’s position is supported by many congressional Republicans (perhaps even some Democrats), a large swath of the American public (and the interest groups who represent them), and key U.S. allies in the Middle East.

In Iran, groups like the Persevering Front are, at the moment, fairly marginal. I’ve seen some in D.C. try to draw equivalence between “hardliners” over here (the U.S.) and over there (Iran) undermining negotiations, when it’s really not the case. Senator Cotton and the coalition he represents can bring pressure to bear on the Obama administration to change its negotiating stance and potentially even block the implementation of a final deal. The Persevering Front, and even parliament as a whole, are not powerful enough to block a deal by themselves. If and when the regime consensus turns against the implementation of a deal—and the parliamentary leadership would have input in any shift—the legislature may become a vehicle for its undoing. And the Persevering Front and their ilk would be the regime and leader’s most loyal pawns leading the headlong charge.

An Untimely Loss, a Timely Memorial

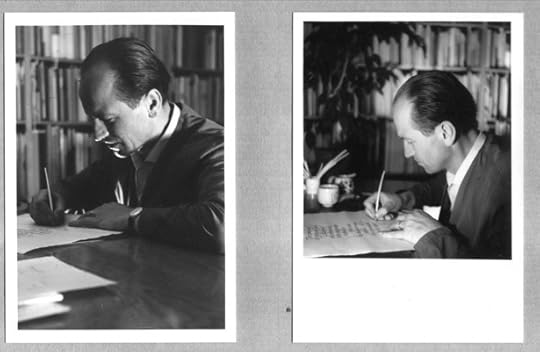

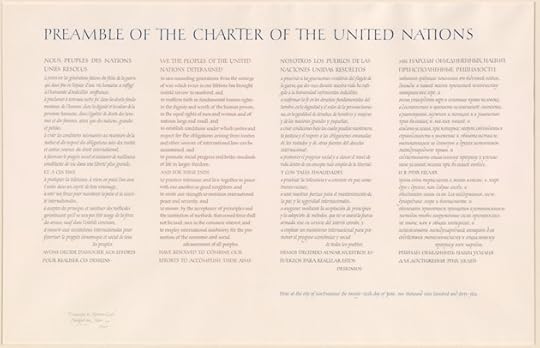

June 26 marked the 70th anniversary of the signing of the United Nations Charter, which the current Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon called a compass for “the hope and home of all humankind.” In part to commemorate the event, New York’s Morgan Library and Museum is currently exhibiting an original calligraphic manuscript of the preamble of the UN Charter, precisely hand-lettered in French, English, Spanish, and Russian by Hermann Zapf. The master type designer, who was also a typographer and calligrapher, died a few weeks earlier on June 4 at the age of 96. Even those unfamiliar with Zapf’s name have likely seen his typefaces—including Palatino and Optima—in books, newspapers, and logos.

The preamble manuscript was personally commissioned in 1960 by Fred Adams, then the director of the Morgan, who greatly admired Zapf and wanted the library's impressive collection of books and typographic material to include the work of “the foremost calligrapher and type designer practicing in Germany today.” The Morgan’s Christine Nelson, who curated the current show, noted the “soaring language” Adams used to announce the acquisition of Zapf’s manuscript: “If typography is basically two-dimensional architecture, and calligraphy contains elements of both music and poetry, it might be said that none of the arts is alien to Mr. Zapf, though he would never say so himself.”

Courtesy of the Morgan Library and Museum

Courtesy of the Morgan Library and Museum The Zapf manuscript, normally stored in the Morgan Library collections vault, has only been exhibited a few times since it was painstakingly lettered, most recently in 2000 in the Grolier Club exhibition. And yet the work meant so much to Zapf that he always kept a full-scale imitation of it in his studio.

As for exactly why the UN Charter’s preamble was chosen for the Morgan’s Zapf commission, it’s unclear. Nelson speculates that it might have something to do with the Soviet Union leader Nikita Khrushchev’s famous appearance at the UN in 1960, or with a special event some UN visitors attended at the Morgan at about that time. But regardless of the actual reason, Nelson says, “Words matter, and the way we experience them matters, and in Zapf’s version of the UN’s founding document I find the words and their form to be, quite simply, worthy of each other.”

The timing of this exhibit is bittersweet since it both celebrates an institution and memorializes an individual. The Morgan had been planning on showing the manuscript a few years from now as part of a permanent collection cycle. Since most of the items in the Morgan's collection are works on paper or vellum that are damaged by prolonged exposure to light they are therefore exhibited sparingly. But then Nelson learned of Zapf’s death. “I found myself overwhelmed with emotion and I wanted to show it immediately,” she says. After further examining the manuscript, Nelson realized that the 70th anniversary of the signing of the UN Charter itself was, by coincidence, just weeks away.

The Zapf UN preamble went on view on June 26 and will be open to the public until October 25, the weekend of UN Day, which marks the date that the Charter went into effect.

July 1, 2015

After Cuba: The Only 3 Countries That Have No Relations With the U.S.

On Wednesday, the United States and Cuba announced that they would reopen embassies in each other’s capitals, thus restoring diplomatic relations for the first time since 1961. The agreement doesn’t mean that Washington-Havana ties will go back to where they were before Fidel Castro’s revolution: Congress still maintains an economic embargo on the island, a policy that’s unlikely to change anytime soon. But the re-establishment of embassies, scheduled to occur on July 20, is nonetheless a major breakthrough in the long-acrimonious relationship between the two countries.

According to The New York Times, the overture to Cuba leaves just three countries with which the United States has no diplomatic relations. Two of these are easy enough to guess: Iran and North Korea. Washington severed ties with Tehran in 1980, months after Iranian students seized the U.S. embassy there and took 52 Americans hostage. U.S. ties with North Korea, meanwhile, have been fraught throughout the latter country’s existence, and have only grown worse since Kim Jong Un assumed control of the country in 2011.

Bhutan is a country with which the U.S. has no real dispute or grievance—or really much history of any kind.But the third country is one with which the United States has no real dispute or grievance—or really much history of any kind. It’s the South Asian kingdom of Bhutan.

Bhutan is a landlocked nation around the size of Switzerland that’s situated in the Himalayan mountains between India and China. Since joining the United Nations in 1971, the country has maintained a Swiss-like aversion to foreign entanglements of any kind. The kingdom has no relations with any of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, and only two states—Bangladesh and neighboring India—have embassies in Bhutan’s capital, Thimphu. Bhutan is so isolated that until 2007, it didn’t even conduct its own foreign policy—India took care of it for them.

In spite of its retreat from the rest of the world, Bhutan is not free of contentious relations. The kingdom has a long-running border dispute with China, which claims roughly 10 percent of Bhutanese territory as its own, and the Chinese government is eager to include Thimphu in its sphere of influence. So far, however, Bhutan has kept its distance: The country recently declined to join the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, a Beijing-led rival to the World Bank. Bhutan’s resistance to China has led some analysts to speculate that the United States should seize the opportunity to formalize relations with the kingdom, a newly consolidated democracy.

But Bhutan’s leaders just don’t see any reason to get closer to the United States. In 2011, Jigmi Yoser Thinley, Bhutan’s then-Prime Minister, told the Bhutanese News Agency that “there was a time when diplomatic relations signified one’s position vis-à-vis conflicting powers, choosing sides. It’s no longer the case.”

The United States also appears to be satisfied with the status quo. In January, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry met with Tshering Tobgay, Bhutan’s prime minister, at a regional summit in Ahmedabad, India, the first-ever meeting between America’s top diplomat and a Bhutanese leader. The talks were apparently warm and productive, but “establishing diplomatic relationship was not a subject of the conversation,” said Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asia Nisha Desai Biswal.

Ebola Returns to Liberia

Less than two months after Liberia was declared Ebola-free by the World Health Organization, the virus is back in the country.

Over the weekend, a 17-year-old boy died in a small town outside the Liberian capital of Monrovia, The New York Times reports. His family had the burial team swab his body to test for the virus. The tests came back positive, as did a blood test taken by an Ebola response team on Tuesday. According to The Times, a clinic initially diagnosed the boy with malaria, which has similar symptoms to the early stages of Ebola.

Agence France-Presse reports that two more patients have tested positive for the disease, and according to the WHO’s latest situation report, health authorities have identified 102 people who were in contact with the boy, a number that is “expected to increase as investigations continue.”

Even when the outbreak fizzled out in Liberia, neighboring Guinea and Sierra Leone have continued to see 20 to 27 cases a week since late May, according to the WHO. There have been more than 11,000 total deaths from the outbreak since it began in March 2014.

Health authorities have identified 102 people who were in contact with the boy, a number that is expected to increase.Right now it’s unclear how the boy got infected—he reportedly had not been to Guinea or Sierra Leone, nor is he thought to have been in contact with anyone visiting from those countries, making it all the more mysterious how the virus found a foothold again in Liberia.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in a statement that the agency is “on the ground with the Liberia Ministry of Health and others working to understand the origin of the reported case of Ebola and stopping spread to others.”

When Ebola first came to Liberia, it overwhelmed the country’s thinly spread health system. Only 170 doctors lived in the country before the outbreak, according to The Wall Street Journal, many of whom weren’t practicing. Protective equipment was sorely lacking, and “few medical staff had been trained in the basic principles of infection prevention and control,” allowing the disease to spread through hospitals and healthcare facilities. West Africa had never seen an Ebola outbreak before, and many people were fearful and distrusting of health workers, and loath to stop traditional burial practices, which included the washing of dead bodies.

But according to the WHO, cases began to decline in the fall of 2014 in Lofa County, which had been one of the epicenters of the disease, and in Monrovia. The WHO credits the eventual eradication of Ebola in Liberia to the leadership of President Ellen Sirleaf, who went on field visits and coordinated the response efforts from international partners, and to “community engagement, acceptance, and ownership of the response.” For example, Liberia’s National Incident Management System divided the country’s largest county, Montserrado, into sectors, and had locals work with health officials to track Ebola cases and educate people in their own communities.

Related Story

A Liberian Hospital After Ebola

“Intensification of technical interventions, like increased laboratory capacity, more treatment beds, and a larger number of contact tracing and burial teams, will not bend the curve in the absence of community engagement and ownership,” the WHO wrote in its January 2015 report, one year into the epidemic.

Since the epidemic began, there’s been significant training of healthcare workers, and new procedures implemented at hospitals. In April, Liberia put forth an Ebola Recovery Plan that includes the goal of improving health delivery, especially in rural areas. However, the plan costs hundreds of millions of dollars, and Ebola hit Liberia’s economy hard, meaning that a lot of that money will have to come from elsewhere.

“There’s a lot we don’t know yet, and this is a reminder of how hard it can be to control Ebola,” the CDC said in a statement. “Liberia is in a much better place to do that today than a year ago.”

The hope is that now that Ebola is a known quantity—albeit a no less dangerous one. Liberia should be better prepared to deal with it this time around.

Magic Mike XXL: This Time It Really Is for the Ladies

Shameless cash-grab. I confess that was my first thought, months ago, when I saw that a sequel to Steven Soderbergh’s 2012 male-stripper movie, Magic Mike, was scheduled to open for the Fourth of July weekend. Unpromising title (Magic Mike XXL)? Check. Tacky teaser poster? Check. Virtually unknown director inheriting duties from Soderbergh? Check. Major star (Matthew McConaughey) who declined to make a return appearance? Check. It hardly helped that the movie’s only competition for the holiday weekend opening was the definitionally shameless cash-grab Terminator Genisys.

But I’m happy to report that my fears of a third-rate sequel have proven entirely misplaced. Magic Mike XXL is, if anything, better than its predecessor: looser, funnier, stranger, and vastly more subversive, a buddy road comedy that unexpectedly evolves into a celebration of female desire.

Related Story

'Magic Mike': Male Strippers Reveal the Naked Truth About the Recession

The first Magic Mike was a well-told but fairly conventional coming-of-age story. Thirtyish Mike Lane (played by Channing Tatum and loosely based on his own experiences) was a self-described entrepreneur by day—his passion was crafting handmade furniture—and a sex-god stripper by night. Over time, and with the help of a Good Woman, he realized that the Dark Temptations of Show Business (meaningless sex, drugs, greed, partying) were preventing him from becoming the Man He Wanted To Be. So he quit.

Magic Mike XXL inverts this story in almost every particular. It’s a movie not about growing up but about recapturing youth, one in which the most cherished value is not responsibility but joy. And unlike the first film, in which considerable attention was placed on the men’s own sexual gratification—think: Matt Bomer inviting others to partake of his wife’s “tits,” or Alex Pettyfer boasting that “I can fuck who I want to fuck”—Magic Mike XXL concerns itself overwhelmingly with the pleasure they offer their female customers. In the earlier movie, these customers were treated mostly as marks, silly young women to be picked up in bars and fleeced; this time out, they’re extolled as “queens” and “goddesses.”

Magic Mike XXL picks up three years after the last installment. Mike’s handmade furniture business is succeeding, but only barely, when his old Kings of Tampa buddies phone to let him know they’ll be passing through town on their way to an annual strippers convention in Myrtle Beach. I won’t give away an early joke by saying what has become of the group’s founder and M.C., Dallas (McConaughey). But suffice it to say that neither he nor “the Kid” (Pettyfer) are along for the ride.

McConaughey’s absence creates one of those tidy instances in which cinematic text and subtext are precisely aligned. In the movie, the guys are happy to be out from underneath Dallas’s domineering thumb, free to experiment with dances more personal and esoteric than the usual cop, firefighter, and construction worker. (Yes, there’s a whiff of Pitch Perfect here.) But more broadly, the lack of McConaughey gives the other, lesser known performers vastly more room to stretch and breathe. Big Dick Richie (Joe Manganiello), Ken (Bomer), Tarzan (Kevin Nash), and Tito (Adam Rodriguez) were barely differentiated as characters in the original; in the sequel, they all come to individual life, with Manganiello a particular delight.

These dudes may be greased-up sex machines lewdly pumping their bethonged pelvises all over the bodies of their paying customers. But that doesn’t mean they’re not gentlemen.Mike—of course—agrees to join his old mates on the trip to Myrtle Beach for One Last Blowout Performance, and what follows is a road trip movie told in three distinct chapters, each lengthier than you might expect and bordering on the surreal. First, the boys visit a strip club catering mostly to women of color situated in a Savannah mansion. (Call it Ladies’ Night in the Garden of Good and Evil.) There, Mike has the opportunity to work through a little complicated history with the proprietress, Rome (an exceptionally good Jada Pinkett Smith). The next stop is a fancy Charleston home, where the fellas intend to visit a young lady, but find themselves instead spending a great deal of quality time with her mother (Andie McDowell) and said mother’s friends. Finally, there’s the Myrtle Beach convention itself, where the Kings unveil such new acts as “Romantic Painter” and “Candy Shop.” (Tucked in along the way are a nice performance by Donald Glover, a.k.a. Childish Gambino, and another by Elizabeth Banks, as a character who claims she “learned everything from Rome.” Her name? Paris.)

There are more conventional elements scattered throughout the film, which is written, like the first, by Reid Carolin, and is directed by the longtime Soderbergh collaborator Gregory Jacobs. A potential love interest for Mike (played by Amber Heard) is supplied, for instance, but her role is peripheral at best.

Whereas the original Magic Mike had a studious verisimilitude to it, this outing represents pure fantasy, simultaneously ridiculous and possessed of a slight glint of magical realism. The sex acts are more rococo than before, but they’re also not only about sex: On at least three occasions, a male performer affectionately serenades his lady with a ballad. In the middle of their Myrtle Beach act, Richie calls out to the ladies in the audience: “There are so many of you and so few of us that we can’t give you all what you deserve. But we’re gonna try.” Unexpectedly, the word that flashes on a screen behind him is “commitment,” and the subsequent number is perhaps the first live strip act ever based on the theme of “marriage.”

It’s a scene that neatly captures Magic Mike XXL in microcosm. Sure, the movie tells us, these dudes may be greased-up sex machines lewdly pumping their bethonged pelvises all over the bodies of their paying customers. But that doesn’t mean they’re not gentlemen.

Can States Ignore the Supreme Court on Gay Marriage?

The Supreme Court’s decision last week did make gay marriage legal around the nation. Unfortunately for social conservatives, it did not, however, make nullification legal around the nation.

Nullification is the historical idea that states can ignore federal laws, or pass laws that supercede them. This concept has a long but not especially honorable pedigree in U.S. history. Its origins date back to antebellum America, where Southern states tried to nullify tariffs and Northern states tried to nullify fugitive-slave laws. In the 1950s, after Brown v. Board of Education, some Southern states tried to pass laws to avoid integrating schools. It didn’t work, because nullification is not constitutional.

Yet futile hope springs eternal. Since the ruling, a handful of officials have suggested that states need not issue licenses for same-sex marriages. The two most notable voices are two Republican candidates for president, Mike Huckabee and Ted Cruz.

They cannot ignore a direct judicial order. The parties to a case cannot ignore a direct judicial order. But it does not mean that those who are not parties to case are bound by a judicial order ....

The entire premise of the decision on marriage was that in 1868, when the people of the United States ratified the 14th Amendment, that we were somehow silently and unawares striking down every marriage law across the country. That's a preposterous notion. That is not law. That is not even dressed up as law.

This is a little slippery to interpret—Cruz’s words are opaque, so that it’s unclear whether he’s actually arguing that officials should refuse to issue marriage licenses, or simply making an intellectual argument that they could. (Or perhaps it’s a dogwhistle!)

Is he right? “It’s ridiculous,” said David Vladeck, a professor of law at Georgetown. “The Supreme Court says the Fourteenth Amendment requires states to issue licenses .… That is the law of the land. We have something in the Constitution called the Supremacy Clause,” which states that the Constitution is the ultimate authority in the U.S.

One argument here is that the ruling only applies to the Sixth Circuit, as that’s where the case the justices decided originated. That might hold true if it was a statutory, rather than constitutional ruling, Vladeck said—but it wasn’t. “Ted Cruz ought to know that. I knew Ted Cruz before he became the new Ted Cruz, and he was an able lawyer,” Vladeck said. “My guess is this is just political posturing of the worst kind.”

“Ted Cruz ought to know that. My guess is this is just political posturing of the worst kind.”Now, a state—say, Texas, where Attorney General Ken Paxton has told clerks they can refuse to issue same-sex marriage licenses—could try its luck: “You don’t have to obey a red light,” Vladeck cracked. But it’s pretty easy to guess what would happen: A plaintiff would bring a civil-rights suit; courts would rule in their favor; and the state would probably have to pay for the plaintiffs’ attorneys fees, under a federal law.

Mike Huckabee takes a slightly different approach: “I'm not sure that every governor and every attorney general should just say, well, it's the law of the land because there's no enabling legislation.”

The former Arkansas governor has been trying this line for some time, but it hasn’t gotten any more correct since I wrote about it in January. Huckabee is claiming that there needs to be an affirmative law authorizing gay marriage, but that’s wrong. The justices ruled only that provisions banning same-sex marriage are illegal, not that all marriage laws have to be rewritten. By analogy, the Supreme Court’s decision overturning bans on mixed-race unions in Loving v. Virginia didn’t eliminate all marriage laws.

Really, the only way a state or jurisdiction could legally circumvent the Court’s ruling would be to stop issuing marriage licenses altogether. “But that would be self-defeating, particularly among people who view marriage as the foundation of American society,” Vladeck noted.

There’s some precedent for that, though it’s not pretty. After Brown, some whites pulled their children out of public schools and opened all-white “segregation academies”—effectively reconstituting the public schools as private ones and avoiding integration orders. Virginia tried to close public schools that integrated. When that was ruled unconstitutional, Prince Edward County simply closed down its entire public-school system. Elsewhere in the South, the resistance was less elaborate—governors like Orval Faubus and George Wallace simply tried to block integration, sometimes by literally standing in the doorway. They were overruled by the federal government.

Related Story

Nullification, Now Coming to the Supreme Court?

Unlike in the 1950s and 1960s, it seems unlikely that the government will send in troops to enforce the Court’s ruling on marriage. That’s because they won’t have to, which is a positive sign for the rule of law in the United States. But there may be a period of litigation as marriage-equality opponents exhaust every possible path (and possibly their states’ coffers) fighting against the ruling.

To see how real the shift is, look to the example of Roy Moore, the chief judge of the Alabama Supreme Court. Moore became famous in an earlier term as chief judge, when he refused to remove a Ten Commandments monument and was removed from the bench. He later returned, and in February instructed Alabama probate clerks not to issue same-sex marriage licenses, despite a federal court striking down Alabama’s gay-marriage ban—a bid for state judiciaries to trump the federal one. This week, Moore issued a confusing order, but then clarified to say that he was not instructing probate clerks to disobey the Supreme Court.

Perhaps Moore doesn’t want to be remembered alongside Orval Faubus and George Wallace. Or maybe he’s just realized what some people were saying all along: There’s no such thing as nullification.

June 30, 2015

Greece Defaults

6:15 p.m.

What happens now?

Greece’s missed payment to the IMF is a milestone—it’s both the first time a developed country has missed such a payment, and the first time a Eurozone country has defaulted on its debt. (Or it’s “in arrears”—as Bouree Lam explains below, the IMF isn’t using consistent terminology.)

But that doesn’t mean automatic expulsion from the Eurozone. Yanis Varoufakis, the country’s finance minister, made the case on his blog three years ago that “a defaulted Greece can easily remain in the Eurozone,” and that in fact “Europe’s optimal strategy is to let Greece default.” The Lisbon Treaty, which forms the legal basis of the European Union, actually makes no provision for a member’s expulsion. A 2009 legal analysis by the ECB found that, “while perhaps feasible through indirect means, a Member State’s expulsion from the EU or EMU [the European Monetary Union], would be legally next to impossible.”

In practice, though, Greece still has to pay its bills with some kind of money—and it’s running out of euros. At the stroke of midnight, there were still euros in Greek banks, but how long Greece can remain on the currency depends, in part, on how long they can keep euros in their coffers—to wit, whether Greece can scrape together new infusions of euros before it runs out entirely. As CNBC explained:

If the Eurosystem—the European Central Bank and the central banks of euro zone members—refuses to finance Greece by halting the release of more emergency loans ... there could be a rapid withdrawal of deposits from Greek banks. Athens would then need to refinance the banking system by creating a new currency to do so.

That’s the “fast exit” option, which Greece could slow down by closing the banks (as it already has) to delay withdrawals. In the “slow exit” option, Greece’s creditors don’t demand their deposits back immediately, but if Greece fails to secure outside sources of financing as public bills such as pensions and state salaries come due, “Greece could substitute ‘IOU's’ for euros in some of its payments,” per CNBC. In the short term, these would in effect become a parallel currency. As the Wall Street Journal explained, “Over time, euros would disappear from circulation because people would hoard them as a store of value—and people would spend the government IOUs. De facto, the drachma, whether or not it would so be called, would become the main means of exchange.”

But there’s also the “no exit” option, where the country just keeps the euro. Polls have indicated that this is what Greeks want to do, and it’s what Prime Minister Alex Tsipras promised to do. If, say, he manages to secure a post-default bailout deal in negotiations set for tomorrow—allowing it to pay its debts to the IMF a few hours, or a few days late—Greece stays in the Eurozone that much longer. But the course of negotiations so far doesn’t give much reason for hope.

—Kathy Gilsinan

6:00 p.m.

It's midnight in Brussels: Greece has officially defaulted.

5:11 p.m

Fitch Ratings Agency has downgraded Greece one level to ‘CC’ as the country nears their midnight deadline. In a release, the agency cited ongoing political and economic turmoil that has kept the country from making a deal to avoid defaulting on its debts as the reasoning behind the downgrade.

With less than one hour left until midnight, it is a virtual certainty that the country will not receive an extension on loans owed to its creditors. In an interview, Eurogroup President Jeroen Dijsselbloem said, “The facts are that the program will expire tonight, and Greece will be in default tomorrow. That is something that I don’t think we can stop between now and tomorrow morning.”

—Gillian White

4:28 p.m.

U.S. markets finished the day with the Dow gaining 0.13 percent and the S&P climbing 0.27 percent for the day. Stocks were up more significantly during morning trading but retreated somewhat after news from Europe made it apparent that Greece wouldn’t reach a deal with creditors to avoid default.

On Tuesday, European markets unsurprisingly showed the greatest sensitivity to Greece’s impending deadline with the Stoxx Europe 600 Index dropping 1.26 percent at close and the FTSE 100 down 1.5 percent.

—Gillian White

3:57 p.m.

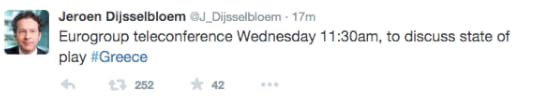

Eurogroup president Jeroen Dijsselbloem has tweeted the time for tomorrow’s meeting:

Meanwhile, Greece’s deputy prime minister Yannis Dragasakis is also calling for a resolution despite reports that a third bailout might impose tougher conditions.

—Bourree Lam

3:09 p.m.

Greece is now just a few hours from falling into “arrears,” unless the IMF agrees to give them more time. This morning, Greece’s finance minister Yanis Varoufakis confirmed that the owed payment would not be coming today. Falling into arrears means that Greece will no longer be eligible for IMF aid. It will be the first advanced economy to fall into arrears with the IMF in its history.

Some say it’s just semantics, because the inability to pay back a loan is generally known as a “default.” But according to Bloomberg: “IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde said on June 18 that she’d consider Greece in ‘default,’ spokesman Gerry Rice said last week that the fund wouldn’t use the term in official communication and would instead refer to Greece being in ‘arrears.’”

—Bourree Lam

3:03 p.m.

The German newspaper Bild is reporting that the Greek government has asked the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to delay today’s midnight deadline for the repayment it owes. According to Reuters, the IMF has declined to comment on the matter.

—Bourree Lam

2:25 p.m.

As expected, an emergency conference call between Eurogroup officials has ended without a deal for Greece, according to tweets from Finland’s representative, Alexander Stubb. The BBC reports that Eurogroup chief Jeroen Dijsselbloem said conversations will resume tomorrow after Greece sends a new proposal, there’s no extension. That means even if tomorrow’s talks are successful, they won’t be in time to prevent Greece from defaulting on its debt at midnight. The European Financial Stability Facility tweeted a release about the impending default from their account on Tuesday.

The Prime Minister of Malta has made comments that Greece would suspend Sunday’s referendum if an agreement is reached.

—Gillian White and Bourree Lam

2:07 p.m.

President Obama made remarks at a press conference today that the Greek debt crisis would create more problems for the Europe than the U.S., though he maintains that it’s an issue of “substantial concern.”

From Politico, Obama said: “In layman’s terms for the American people, this is not something that we believe will have a major shock to the system.”

—Bourree Lam

2:02 p.m.

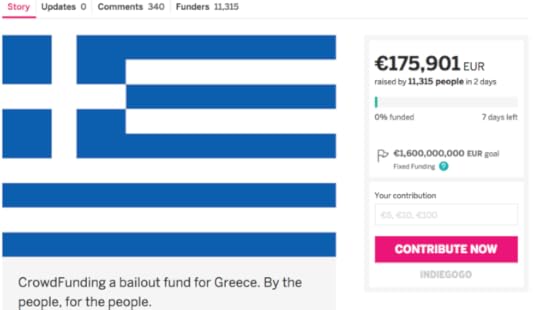

With the midnight default deadline swiftly approaching and most official avenues declaring that they wouldn’t step in to provide emergency funding (or step up to pay) the people of the Internet tried to come to Greece’s aid. In fact, too many people tried, causing the Indiegogo page aimed at using crowd funding to solve the debt default, to crash.

The page, started by a British man named Thom Feeney, asked Europeans to donate “the cost of a feta and olive salad" to the cause, reasoning that together, they could raise the €1.6 billion to prevent default. A noble endeavor.

The Indiegogo Greece bailout page Tuesday morning, prior to the crash. (Indiegogo.com)

The Indiegogo Greece bailout page Tuesday morning, prior to the crash. (Indiegogo.com) Still, raising over €1 billion is a herculean task. Earlier today, despite numerous donations that topped €175,000, the campaign had yet to even reach 1 percent of its funding goal.

—Gillian White

1:06 p.m.

Protesters are gathering in Athens to agitate for a “yes” vote on Sunday’s referendum about whether to accept the terms of the deal Greece’s creditors offered last Thursday. Greek Prime Minister Alex Tsipras, who effectively shut down negotiations Saturday morning with his surprise announcement he’d put the proposals to voters, has urged a “no” vote. A “yes” vote could mean the end of his government. “If the Greek people want to have a humiliated prime minister, there are a lot of them out there. It won't be me," he said, according to Reuters, which reported “tens of thousands of Greeks” rallying in his favor on Monday.

Demonstrators gather during a rally organized by supporters of the YES vote to the upcoming referendum, at Syntagma square in Athens Tuesday. (Thanassis Stavrakis/AP)

Demonstrators gather during a rally organized by supporters of the YES vote to the upcoming referendum, at Syntagma square in Athens Tuesday. (Thanassis Stavrakis/AP)  Demonstrators hold a giant European Union flag reading ''YES'' during a rally organized by supporters of the YES vote to the upcoming referendum in Athens, Tuesday (Daniel Ochoa de Olza/AP).

Demonstrators hold a giant European Union flag reading ''YES'' during a rally organized by supporters of the YES vote to the upcoming referendum in Athens, Tuesday (Daniel Ochoa de Olza/AP).  Pro-euro protestors attend a rally in front of the parliament building, in Athens, Greece, June 30, 2015. (Marko Djurica/Reuters)

Pro-euro protestors attend a rally in front of the parliament building, in Athens, Greece, June 30, 2015. (Marko Djurica/Reuters) —Kathy Gilsinan

1:03 p.m.

At this point, Greece’s best (if only) bet for avoiding a default at midnight is emergency funding. With a conference call happening shortly, Reuters asked about the likelihood that finance ministers would provide a lifeline before midnight. A Eurogroup official all but dashed hopes of a last-minute reprieve saying that there was “no way” funds would be released in time to cover the IMF payment.

—Gillian White

12:32 p.m.

Stocks in Europe were calmer earlier today on the news that Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras might reach a last minute bailout deal with Greece’s creditors. Things took a turn before the markets closed as no deal has been reached yet. The Stoxx Europe 600 Index dropped 1.26 percent at close, the FTSE 100 closed down 1.5 percent, with losses in Germany’s Dax index and France’s Cac 40 as well.

U.S. stocks were up earlier today as well, rebounding from yesterday’s selloff. Though at the moment, it looks like the Dow and S&P have erased much of the gains from this morning—likely on the news that a deal might not be reached tonight.

—Bourree Lam

12:13 p.m.

William Antholis, the former director of international economic affairs on the White House National Security Council, writes in Fortune about his experience with the politics and politicians behind the current crisis and reflects on the most important aspect of the debt debacle—how it impacts the people of Greece.

This year the crisis came home directly. The look of real frustration and fear in the faces of hotel clerks, cab drivers, restaurant owners, and politicians remind us that modern, industrial societies can experience true depression.

...

There is still a chance that they can pull a rabbit out of the hat. But for the first time in the last five years, I’m not optimistic.

You can read the entire essay here.

—Gillian White

11:54 a.m.

Greece’s finance minister Yanis Varoufakis is mobbed by reporters as he leaves his office in Athens on motorbike to meet with Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras at Maximos Mansion.

(Daniel Ochoa de Olza / AP Photos)

(Daniel Ochoa de Olza / AP Photos) Greece is several hours from the midnight default deadline, and Eurozone finance ministers are set to review Tsipras’ new bailout proposal using European Stability Mechanism loans in an hour.

—Bourree Lam

11:37 a.m.

Deutsche Welle notes that Nobel prize-winning economists are divided on whether or not Greek voters should accept the deal they’re being asked to vote on in Sunday’s “Greferendum.” Joseph Stiglitz and Paul Krugman are in the “no” camp.

Here’s Stiglitz, who scolds Greece’s creditors in The Guardian for the “abysmal” economics behind the last bailout, and warns that the current proposals will “inevitably result in a deeper downturn”:

I can think of no depression, ever, that has been so deliberate and had such catastrophic consequences: Greece’s rate of youth unemployment, for example, now exceeds 60%.

It is startling that the troika has refused to accept responsibility for any of this or admit how bad its forecasts and models have been. But what is even more surprising is that Europe’s leaders have not even learned. The troika is still demanding that Greece achieve a primary budget surplus (excluding interest payments) of 3.5% of GDP by 2018.

....

[A] no vote would at least open the possibility that Greece, with its strong democratic tradition, might grasp its destiny in its own hands. Greeks might gain the opportunity to shape a future that, though perhaps not as prosperous as the past, is far more hopeful than the unconscionable torture of the present.

I know how I would vote.

Here’s Krugman, doubling down on the Greece-related portmanteaus in a blog post titled “Grisis:”

I would vote no, for two reasons. First, much as the prospect of euro exit frightens everyone—me included—the troika is now effectively demanding that the policy regime of the past five years be continued indefinitely. Where is the hope in that? Maybe, just maybe, the willingness to leave will inspire a rethink, although probably not. But even so, devaluation couldn’t create that much more chaos than already exists, and would pave the way for eventual recovery, just as it has in many other times and places. Greece is not that different.

Second, the political implications of a yes vote would be deeply troubling. The troika clearly did a reverse Corleone—they made Tsipras an offer he can’t accept, and presumably did this knowingly. So the ultimatum was, in effect, a move to replace the Greek government. And even if you don’t like Syriza, that has to be disturbing for anyone who believes in European ideals.

Christopher Pissarides, another Nobel-winner who was one of Stiglitz’s co-authors in a Financial Times letter to the editor urging debt relief for Greece in exchange for reforms, said Greece should vote yes:

The only thing that could get us moving in a good direction is a Yes vote and a strong government to sit there and renegotiate some parts of the program. I know the suggestions have been withdrawn by the European institutions, but I am sure if there is a Yes vote, especially if there is a good majority, they would come back to the negotiating table and negotiate something on the debt, negotiate some immediate policy needed now to get us into a reform program and move forward from there. I can't see how a No vote would help anything at all now.

I would vote Yes and I would encourage everyone that I can to vote Yes, because a No vote would be a complete dead end which would lead eventually to a Grexit.

FT’s Martin Wolf, is “a-pox-on-both-their-houses” noncommittal:

In making my decision, I would bemoan both the idiotic leftism of my own government and the self-righteousness of the rest of the eurozone. Nobody comes out of this saga with credit.

The Syriza government has failed to put forward a credible program of reform that might solve the multiple problems of the Greek economy and polity. It has instead made populist gestures. It is, in brief, a dreadful government produced by desperate times.

Yet the eurozone, too, deserves substantial blame for the outcome. One would never guess from its rhetoric that Germany was a serial defaulter in the 20th century. Moreover, there is no democracy, including the UK, whose politics would survive such a huge depression unscathed. Remember, when Germany last suffered a depression of this magnitude, Hitler came to power. Yes, Syriza is the outcome of infantile and irresponsible Greek politics. But it is also the result of blunders committed by the creditors since 2010 and, above all, insistence on bailing out Greece’s foolish private creditors at the expense of the Greek people.

As for what Greek voters themselves are facing, the text of the referendum itself, which my colleagues posted below, is confusing. It refers to “the plan of agreement” submitted June 25, 2015—which, given Greece’s apparent new offer, and the imminent threat of Greece not paying the IMF by today’s deadline, may not even still be on offer by the time Greeks are expected to cast ballots on Sunday. (Though, who knows, the referendum itself might be called off.) As the BBC notes, “there is still a question over when and how voters will be presented with those documents, and whether world-class economists will be on hand at polling stations to explain them.”

—Kathy Gilsinan

11:35 a.m.

The BBC reports that German Chancellor Angela Merkel has said no new aid proposals will be discussed until after Sunday’s Greek referendum. If true, that would mean that Greece’s decision to not pay creditors on Tuesday will result in default.

—Gillian White

10:47 a.m.

Politico has posted Greek Prime Minister Alex Tsipras’ letter to Eurogroup president Jeroen Dijsselbloem for rescue funds as well as an extension for the current bailout which expires midnight tonight (6 p.m. ET). Should the extension be granted, the question remains on whether Sunday’s Greek referendum will still happen. The Guardian is reporting that the proposal has just arrived in Brussels, and Dijsselbloem tweeted that eurozone finance ministers will hold a teleconference in 2 hours to discuss how to move forward.

—Bourree Lam

10: 32 a.m.

The future of Greece’s currency is not as black and white as it might seem. A “no” vote on Sunday’s referendum doesn’t mean that Greece will automatically leave the Eurozone, a fact that Germany’s finance minister, Wolfgang Schaeuble, was keen to remind lawmakers of on Tuesday, according to reports from Bloomberg. The Wall Street Journal has put together a roundup of five possible options for the country’s currency, which include keeping the euro, having both euro and drachma circulation, and pegging drachmas to euros.

—Gillian White

9:54 a.m.

Reuters is reporting a new rescue proposal from Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras’ office has just been submitted to Greece’s creditors. A statement from Tsipras says that the Greek government wants a new two-year deal under the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) program, a move some are calling a third bailout. The late-breaking request asks for debt restructuring and would tap into the ESM—which has a €500 billion lending capacity. It’s unclear how Greece’s creditors will react, although Germany’s chancellor Angela Merkel hasn’t yet given any reason for hope on the matter.

—Bourree Lam

9:45 a.m

After the largest decline of 2015, U.S. stocks pushed higher on Tuesday with both the Dow and S&P up by about 0.50 percent just after the market’s opening. The optimistic performance follows a strong rebound in Asian markets overnight.

—Gillian White

9:22 a.m.

Markets across Asia rebounded strongly with the Tokyo Nikkei closing up 0.63 percent, Hong Kong’s Hang Sang Index up 1.09 percent, Seoul up 0.67 percent, and the Shanghai Composite up 5.6 percent. The euro is down, but some investors and traders say the experts will wait to see how the debt crisis pans out before making big moves.

—Bourree Lam

8:59 a.m.

According to the Wall Street Journal, Greece’s finance minister has said that some bank branches may reopen on Wednesday to service those who don’t have access to debt or credit cards, including many pension recipients. Withdrawals will be limited to €120 ($134). The finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, has also said that Greece has no intention of paying the IMF by the end of Tuesday’s deadline, and that he instead hopes that a last-minute deal is reached.

—Gillian White

8:42 a.m.

World markets are still on edge as Greece nears its deadline. News of the a last-minute deal have given European stocks a boost and U.S. futures are also looking up.

Tom Metcalf and Robert Lafranco over at Bloomberg tallied how much the world’s 400 richest people lost yesterday and arrived at a combined $70 billion, or an average of $175 million each.

—Bourree Lam

8:04 a.m.

Last-minute talks are reportedly happening in Athens. One of Greece’s creditors, the European Commission, has reached out to make a deal—though it remains unclear what the details of the deal are and whether this is the same deal from last week.

The new offer will likely involve Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras trying to encourage Greeks to vote “yes” in Sunday’s referendum. Yesterday, Tsipras appeared on television to appeal to Greeks to vote “no.” Tsipras has been hinting that he would resign if the outcome of the vote is a “yes.”

—Bourree Lam

7:51 a.m.

On Tuesday, markets in Asia recouped the losses sustained during Monday’s sell off on the news of an impending Greek default. In China, stocks gained about 5.6 percent.

—Gillian White

Greece is officially out of time.

A decision on whether or not the deeply indebted country will work out a plan with its creditors or default on the €1.54 billion ($1.69 billion) it owes to the IMF and EU—a move that could serve as the prelude to the country exiting the eurozone, the much feared “Grexit”— has come down to the wire, with the country’s future still uncertain today, the deadline for payments or extension. Notable economists have called for Greece to sign a deal immediately, and for its creditors to abandon austerity.

On Monday, the English text of the Greece’s referendum ballot question was posted to Twitter.

Should the agreement plan submitted by the European Commission, European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund to the June 25 eurogroup and consisting of two parts, which form their single proposal, be accepted? The first document is titled ‘Reforms for the completion of the Current Program and Beyond’ and the second ‘Preliminary Debt sustainability Analysis’.

On July 5 Greek citizens will vote yes or no to the proposal.

The situation is already bleak. According to one estimate, Greece owes its lenders a total of €242.8 billion ($271 billion). In Greece, banks are closed, capital controls have been imposed, and the stock market shuttered. The rest of the world doesn’t have much faith in the ability for a deal to get done either. On Monday, stocks in the U.S. had their worst showing in 2015, as the Dow tumbled 350 points and the S&P had its worst day of the year Monday.

The post will be continually updated above.

What Is the European Union, Exactly?

In 1961, the economist Robert Mundell published a paper laying out, per the title, “A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas.” In it, he inquired about the appropriate geographic extent of a shared unit of money. Was it the world? A country? Part of a country? A border-spanning region of, say, the western parts of the United States and Canada, with a separate currency circulating in the eastern parts of the two countries?

“It might seem at first that the question is purely academic,” he wrote, “since it hardly seems within the realm of political feasibility that national currencies would ever be abandoned in favor of any other arrangement.” But it was worth considering anyway, in part because “certain parts of the world are undergoing processes of economic integration and disintegration,” and an idea of what an “optimum currency area” would look like could help “clarify the meaning of these experiments.”

Related Story

The Greek Debt Crisis: Live Updates

Mundell’s paper was published four years after the establishment in 1957 of the European Economic Community, which aimed to more closely integrate European countries economically and politically, and laid the groundwork for a common market that would enable the free movement of goods and people across the region’s borders. Sixteen years ago, in 1999, the euro was adopted as the common currency of 11 European countries; the same year, Mundell won a Nobel Prize in economics in part for his work on optimum currency areas. Fourteen years ago, Greece joined the currency union. Five years ago came the first hints that a debt crisis might force Greece to leave. Today, 19 countries share the euro, but the dominant headlines are more about disintegration than integration, with Greece’s finance minister confirming that the country will miss Tuesday’s deadline to repay a roughly $1.8 billion loan to the International Monetary Fund. Greece’s banks are now closed as it heads into a Sunday referendum on further government spending cuts and tax increases that may determine whether the nation stays in the eurozone. Whatever else the question of optimum currency areas is, it’s not just academic.

Mundell noted that a previous generation of economists had “generally favored a world currency.” John Stuart Mill, for example, wrote in Principles of Political Economy, first published in 1848, that it was due to “barbarism … in the transactions of most civilised nations, that almost all independent countries choose to assert their nationality by having, to their own inconvenience and that of their neighbours, a peculiar currency of their own.” In 1869, Walter Bagehot, then the editor of The Economist, conceived of a kind of trans-Atlantic currency union between Britain and the United States “as a step towards a universal money.” Observing the French-led formation of “a great coinage league”—the Latin Monetary Union, which established fixed exchange rates among a membership that grew to include 11 countries before it fell apart during World War I—Bagehot warned that “Before long, all Europe will have one money, and England will be left outstanding with another money.” Mundell wrote:

Mill, like Bagehot and others, was concerned with the costs of valuation and money-changing ... and it is readily seen that these costs tend to increase with the number of currencies. Any given money qua numeraire or unit of account fulfills this function less adequately if the prices of foreign goods are expressed in terms of foreign currency and must then be translated into domestic currency prices. Similarly, money in its role of medium of exchange is less useful if there are many currencies. ... (Indeed, in a hypothetical world in which the number of currencies equaled the number of commodities, the usefulness of money in its roles of unit of account and medium of exchange would disappear, and trade might just as well be conducted in terms of pure barter.) Money is a convenience and this restricts the optimum number of currencies.

The mid-19th century was a time “of monetary chaos around the world,” Kathleen McNamara, an associate professor of government and foreign service at Georgetown University, told me. That chaos extended to the United States, where until the Civil War a number of different currencies circulated. The Industrial Revolution had provided incentives “to integrate markets and trade across areas,” she said, “but they had these chaotic, very local monetary systems, where the transaction costs were huge, because you have to kind of figure out what the different exchanges are.”

Given all the costs associated with multiple currencies, why not just establish a world currency? McNamara said there are two main takeaways from the literature on optimal currency areas. “One is the notion that currency changes help economies adjust.” If a country lets its currency depreciate, or lose value, for example, its exports become cheaper and thereby more in demand relative to other goods on the world market, helping ease unemployment. “So if you take that away, if you in fact create one large currency area, then you have to make sure that that currency area has other ways of adjusting” to shocks like inflation or rising unemployment, she said. “And the easiest way of adjusting is to move factors of production, so labor moves. So for example, say there’s unemployment in one part of the currency area, labor has to be able to move easily to other parts of the currency area.” (In principle, the European Union permits free movement of labor, although in practice, language differences and immigration restrictions among eurozone countries pose barriers to such movement.)

“The second thing is this ‘asymmetric shock’ idea,” McNamara said. For example, if one part of an economic region is booming and another is facing a slowdown—as was the case with Ireland and Germany, respectively, in 2002—they require different kinds of policies to adjust. “The more alike a region is, the more likely they’ll need the same kinds of economic prescriptions in the case of a shock.”

“People think about the United States as a nation-state. People don’t know how to think about the European Union.”In that sense, the United States itself might not have been an optimal currency union for much of its history. In a 2000 paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research, Hugh Rockoff argued that until the 1930s, “the United States might well have been better off if each region had had its own currency,” since shocks to agricultural or financial markets hit different regions and their banks differently. “Often, an interregional debate over monetary institutions would follow,” he wrote. “The uncertainty created by the debate would further aggravate the contraction.”

Asymmetric shocks like these persist in the modern U.S. economy. Florida, for example, can experience a housing bust even as the timber markets of the Pacific Northwest remain relatively robust. Florida can’t devalue its currency to stimulate exports, and yet nobody was talking about the threat to the dollar zone from a potential Florexit back in 2010.

McNamara maintains that the difference is less technical than political. “People think about the United States as a nation-state,” she said. “People don’t know how to think about the [European Union]. … Throughout the entire eurozone crisis, traders, financial actors, have been kind of casting around to figure out, ‘How tightly bound together is the EU as a political entity? Can we really count on the other members bailing out Greece?’”

As of Tuesday, the answer seemed to be no—but that uncertainty has lingered for five years as voters in the eurozone’s richer core, most notably in Germany, have signaled an unwillingness to help Greece pay its debts. The United States, by contrast, has since the 1930s developed institutions to make those kinds of transfers automatically, as Paul Krugman explained three years ago in regard to Florida:

America may have a small welfare state by European standards, but it’s still pretty big, with large spending in particular on Social Security and Medicare—obviously both a big deal in Florida. These programs are, however, paid for at a national level. What this means is that if Florida suffers an asymmetric adverse shock, it will receive an automatic compensating transfer from the rest of the country: it pays less into the national budget, but this has no impact on the benefits it receives, and may even increase its benefits if they come from programs like unemployment benefits, food stamps, and Medicaid that expand in the face of economic distress.

“For all of the United States’ problems, we still are a federal nation-state. … Nobody doubts that,” McNamara said. The European Union is not a nation-state, and the anxiety surrounding Greece has revealed that markets—and even the eurozone’s constituent nations—still aren’t quite sure what the EU is.

“It’s this innovative, emergent kind of governance form,” McNamara explained. In that sense, the current crisis is bigger than Greece’s 2-percent share in the European Union’s GDP; it tests the very meaning of EU membership. It’s an experiment that’s ongoing as Greece runs out of money, and it won’t be settled anytime soon whether or not Greece remains in the union. Rockoff estimated that it took a minimum of 150 years for the United States to become an optimal currency area.

For now, the result of the EU’s identity crisis is turmoil. As McNamara noted, “Markets hate uncertainty.”

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower