Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 396

July 8, 2015

Can Better Data Help Solve America's Housing Problems?

Ever since the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968, the federal government has been obligated to try and foster inclusive, diverse communities. In practice, that means moving poor, black families into richer, white neighborhoods and providing grants for improving areas of concentrated poverty.

But for decades, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD, has fallen short of these goals, and at times its efforts have even backfired, perpetuating patterns of segregation by building more housing for America’s poorest in America’s poorest neighborhoods. Deep racial and economic segregation continues to dictate where Americans live.

More From Getting Rid of Bosses Affordable Housing, Always The Customizable Retirement

Getting Rid of Bosses Affordable Housing, Always The Customizable Retirement “One of the problems with the failure to really give this statutory provision meaning and teeth up until now is that people could pretend it didn’t mean anything, and failure to comply with it didn’t have consequences,” said Betsy Julian, the president of Inclusive Communities Project, a Dallas non-profit that recently won a Supreme Court case protecting parts of the Fair Housing Act. (Julian also served as HUD’s Assistant Secretary for Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity in the Clinton Administration.)

On Wednesday, HUD took a big step toward fixing its own ineffectiveness, releasing a new rule that requires that cities and regions evaluate the presence of fair housing in their communities, submit reports detailing the presence of segregation and blight, and detail what they plan to do about it. Communities will be required to hold meetings or otherwise solicit public opinion about housing planning and integration every five years, and will have a new trove of resources to assess their progress.

“This important step will give local leaders the tools they need to provide all Americans with access to safe, affordable housing in communities that are rich with opportunity,” said HUD Secretary Julian Castro.

Parts of the new rule will take effect in 30 days.

By law, communities are expected to affirmatively further fair housing through the way they use federal funds, including Community Development Block Grants (used for a variety of development initiatives), public-housing-authority programs such as Housing Choice Vouchers and housing complexes, and HOME grants, which fund the development of affordable housing.

But the law previously only required that, to get these funds, communities certify that they have a document called an Analysis of Impediments outlining why people could not find affordable housing, and that they are taking actions to overcome these impediments. Many communities don’t update their Analysis of Impediments, though; a 2010 GAO report found that some grant recipients didn’t have a document at all, and in other communities, the reports were from the 1990s.

The new rule replaces this process with a tool that allows participants to assess fair housing issues in their communities with the aid of data provided by HUD. Cities, regions, or housing authorities will submit a document called an Assessment of Fair Housing to HUD, which will review and accept the document. That document will analyze integration patterns and disparities in access to high-quality affordable housing, and will include input from the community on what to do about it. HUD can choose to reject parts of a community’s Assessment of Fair Housing if it determines that that plan is incomplete or is inconsistent with fair-housing laws.

This may all just sound like a change in the way housing authorities do their paperwork, but for housing advocates, this is a big deal.

“This is going to be an incredibly important and positive step to changing things over the long run,” said Ed Gramlich, a special advisor to the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Previously, there had been no definition of what, exactly, an impediment to fair housing is, and what communities should do about it. The county of Westchester, in New York, for example, took millions of dollars of federal housing money and claimed to comply with fair-housing mandates. It signed a consent decree in 2009 to settle a lawsuit about this, but still has not taken any steps to comply with fair-housing laws, and the county executive there has spoken publicly about his opposition to integration.

Now, HUD will be hopefully able to spot such misuses of funds before the money is spent. Jurisdictions have guidance for how they can “affirmatively further fair housing,” and administrations that want to enforce the Fair Housing Act have more tools at their disposal.

The tools and data that jurisdictions will use to figure out whether they are promoting fair housing are the “centerpiece” of the new rule, according to the Washington Post’s Emily Badger.

“The premise of the rule is that all of this mapped data will make hidden barriers visible—and that once communities see them, they will be much harder to ignore,” she writes.

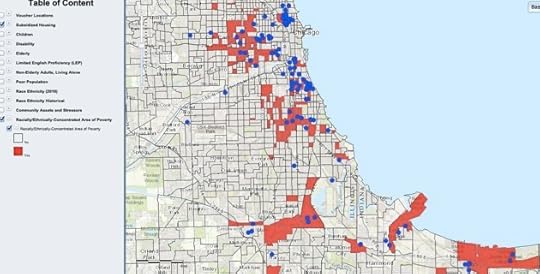

The mapping tool will include data about housing, voucher locations, subsidized housing, income, limited income proficiency and other factors. A prototype of that map, released last year, is a stark reminder of the segregation that exists across the country today.

The new HUD map allows users to look at factors including racially-concentrated poverty (red) and public housing complexes (blue). (HUD)

The new HUD map allows users to look at factors including racially-concentrated poverty (red) and public housing complexes (blue). (HUD) The new rule comes on the heels of the Inclusive Communities decision by the Supreme Court, in which the Court ruled, 5-4, that housing policies that have a disparate impact on minority populations are illegal, whether or not discrimination is present. Disparate impact is a separate issue than policies that “affirmatively further fair housing,” but both concern what the law has to say about integration and fairness in the nation’s housing stock.

Taken together, said Julian, of Inclusive Communities, the new HUD rule and the Supreme Court decision require public entities that administer federal funds to take a hard look at whether their programs are working to integrate their residents..

These entities don’t just include HUD—they also include states that distribute Low Income Housing Tax Credits, which were the subject of the Supreme Court case, as well as transportation entities that administer urban development funds and city housing authorities that build in urban and suburban areas.

They’ll have to look at whether “those programs have been operating with the effect of perpetuating segregation, containing people in neighborhoods and communities marked by conditions of slum and blight, and excluding people from well-resourced neighborhoods and communities,” she said.

The new rule makes communities look at their segregation and poverty patterns, Julian said, while at the same time holding them accountable for remedying them. That was the goal of the Fair Housing Act of 1968. Now, it might just begin to happen.

“The imperative to appropriately address those conditions of distress becomes a civil rights and fair housing imperative, not just a feel good community development policy,” she said.

The Unbearable Darkness of Prestige Television

Never has California seemed as gloomy as it does in the premiere of True Detective’s second season. It would be hard to choose the episode’s darkest moment—was it the near-suicidal nighttime motorcycle ride? The sad blowjob? The brutal beating of a man in front of his son, by a cop whose own child may be the result of an unsolved rape? So far, at least three of the show’s main characters are so dour, drunk, and all-around dyspeptic, they make the denizens of film noir look positively chipper by comparison.

Related Story

The Golden Age of TV and the Rise of the Antihero

And yet, such moodiness is far from an anomaly. Consider how many other current acclaimed shows cultivate a similarly somber mood. From the bro-style bloviating (or, broviating) of True Detective’s first season, to the ominous proclaiming that punctuates the general whoring and slaying of Game of Thrones, to the unceasing climatological and psychological punishments meted out to the cast of The Killing, it seems as though some of the most celebrated recent examples of serial drama have elected self-seriousness as their default tone. Especially paradigmatic of this drift toward the ponderous is The Walking Dead, whose third season includes episodes entitled “Made to Suffer,” “The Suicide King,” and “This Sorrowful Life”—titles that could just as easily characterize the despondent state of affairs on any number of shows viewers and critics alike have been singling out for praise. Game of Thrones, for instance, killed off one of its most jovial characters, Robert Baratheon, in the seventh episode, and with him, seemingly any hope of ensuring the series’s main players—in the words of the murdered king—“don’t look so fucking grim all the time.” It’s as if these programs, intent on proving their “quality,” fall into the trap of protesting too much.

This new strain of humorlessness comes across most palpably in programs that are also works of genre, from the police procedural (in the case of True Detective or The Killing), fantasy (Game of Thrones), to horror (The Walking Dead). In fact, it’s probably no coincidence that genre series are the most committed to this sort of sober and high-minded tone. This new solemnity could be seen as a sign of status anxiety: a byproduct of both serial television’s desire to disassociate from its soapy origins, and genre programming’s striving for cultural legitimacy. In short, these shows are victims of their own pretensions. TV might be enjoying a Golden Age, but it appears it may also be harboring some self-doubt.

To prove that such cheerlessness isn’t unique to American drama, there’s the BBC series The Fall. During the second season there’s precisely one moment that earns a laugh, and it’s when a member of the Belfast police department—engaged in what’s supposed to be a surreptitious search of a suspect’s house—puts his foot through the attic floor, causing the bedroom ceiling to collapse. It’s the sole instance of slapstick in a show that’s otherwise unwaveringly grim. Of course, its primary concerns—sexual violence, psychopathy, Irish sectarian tensions—don’t exactly lend themselves to lighthearted treatment. But there’s a difference between tackling bleak topics, and making a virtue, if not a fetish, of bleakness.

TV may be enjoying a Golden Age, but it appears it may also be harboring some self-doubt.It’s a tendency that hasn’t gone unnoticed by critics. The New Yorker’s Emily Nussbaum, for instance, argued that one of True Detective’s principal transgressions was that it remained “dead serious” about even the most “softheaded” of its own premises. “Which might be O.K. if True Detective were dumb fun,” she notes, “but good God, it’s not: It’s got so much gravitas it could run for President.” Similarly, in his review of the most recent season of The Killing, Matt Zoller Seitz lamented that the series remained “full of itself, occasional moments of levity notwithstanding,” and was ultimately undone by its “gravely solemn, we-are-reinventing-the-genre swagger that doesn’t sync up with the stereotype-driven, sub-Special Victims Unit procedural you are actually watching ... ”

But lately, such solemnity feels less like the exception than the rule.

Call it serial pretension—a product of genre television’s still-uncertain sense of its own value. On the one hand, it seems quaint to suggest that programs in the postmodern era should be entangled with questions of taste, or that audiences might be embarrassed by their appetite for genre entertainment, or what the film critic Pauline Kael famously hailed as “trash.” But even the most masterly examples of serial drama aren’t immune to such worries. As the film scholar Linda Williams notes in her study of The Wire, its creator David Simon made a habit of comparing his series “up”—likening it to Sophoclean tragedy, for instance—while its fans have frequently analogized it to Dickens, as if to prevent its being designated as “mere” television. Equally revealing is Daniel Mendelsohn’s defense of Game of Thrones, which hinged on the show’s exceptionally “literary” qualities—the explanation, he suggests, for it having “seduced so many of his [writer] friends, people who have either no taste for fantasy or no interest in television.”

This sense of hierarchy when it comes to culture is evident not only in the regular invocations of literature in discussions about television, but also in the broader deprecation of comedy. As The New Yorker’s Richard Brody put it bluntly, in a larger discussion of Hollywood cinema and award-season trends, “comedy gets no respect.” The situation may be somewhat different in television, where series like Veep, Silicon Valley, and Girls receive regular accolades, but even the most admired comedies don’t tend to attract the kind of genuflecting reserved for drama. And no genre remains more routinely and unselfconsciously maligned than melodrama. Anecdotal evidence suggests that few people admit to an enjoyment of prime-time soaps like Nashville, Empire, or Revenge without qualifying their predilection as “guilty,” or bracketing off the show as “trash.”

The extent to which TV drama has internalized this value system is reflected not only in its bias toward dark and punishingly tragic content, but in its narrative tendencies, as well—particularly its emphasis on what the television scholar Jason Mittell calls “narrative complexity.” For Mittell, a hallmark of complex TV is that it prioritizes plot events over character relations, in contrast to the relationship-driven soap opera. It’s a description that readily applies to shows like The Walking Dead or Game of Thrones, which don’t just give precedence to plot (leading one critic to dub GoT the “plottiest show on television”), but which do so at the expense of characters, who are casually and often gruesomely dispatched. It’s true these two shows, in particular, take their cues from literary (or graphic literary) sources. Regardless, their veneration for plot suggests they’ve seized on complexity as the surest path to prestige.

The very structure of Game of Thrones seems to telegraph its ambitions. Take “The Wall”: a 700-foot-tall barrier of solid ice that separates the north of Westeros from the dangers beyond. On the far side, we’re in the realm of pure pulp: a world of unchecked blood-letting, incestuous coupling, and White-Walking. Not so different from what takes place within the Wall, only there’s far less concern that the unfolding events must mean something. Back in the Seven Kingdoms, however, the target mode is historical realism. Here, the set pieces are epic; the moral stakes high; and the dialogue portentous, so that even passing exchanges are made to seem positively refulgent with meaning. Here, characters are given to announcing a scene’s thematic significance: The scheming counselor Varys can proclaim, in the season five premiere, “We’re talking about the future of our country!” Or Daenerys Targaryen, the aspiring queen and current warlord, can remind viewers—in a Days of our Lives-worthy piece of exposition,—“I did not take up residence in this pyramid so I could watch the city below decline into chaos!”

In this light, while early reviews of Game of Thrones often focused on rescuing it from the genre label—“boy fiction,” as Ginia Bellafonte termed it in The New York Times—one issue with the show is that it isn’t genre enough. If, as Nussbaum has observed, “fantasy—like television itself, really—has long been burdened with audience condescension,” the solution is not to tamp down (or wall off) the fantasy. In contrast to proud genre series like The Americans, Justified, or Orphan Black—which concern themselves with the subjects of spy-craft, gun thuggery, and clone warfare, respectively—Game of Thrones, The Walking Dead, and True Detective seem almost self-loathing, and for all their nudity and gore, ashamed to indulge their B-movie impulses. That’s not to say there are no funny moments; as Lord Tyrion on GoT, Peter Dinklage has performed heroic feats of comic relief. But on balance, these programs qualify as punitive pulp: a subcategory of shows that exploit viewers’ love of swordplay, zombies, and serial killers while denying them the lurid pleasures therein.

So who’s to blame for this grim state of affairs? It’s tough to say. Not only because the collaborative nature of the medium makes it hard to determine who’s “responsible” for a program’s tone, but because tone itself is so slippery, a product of viewers’ perceptions as well as showrunners’ intentions. At the same time, it seems significant, as Mittell mentioned to me, that three of the above-mentioned series were created and/or written by those with little previous experience in TV, and far more in the worlds of fiction (Nic Pizzolatto), film (Frank Darabont), or both (David Benioff). It’s not farfetched to think that they might be bringing to one medium the norms and practices of another.

These programs qualify as punitive pulp, exploiting viewers’ love of swordplay, zombies, and serial killers, while denying them the lurid pleasures therein.It’s a factor that could help explain the difference between these shows and the many dramas that don’t suffer from such pomposity of spirit, including canonical series like The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, or The Wire—which as Jacob Weisberg noted in Slate, “attains the dimensions of tragedy without being depressing.” It’s true that some of the shows I mention occasionally manage a similar feat. True Detective’s pilot, for instance, has lots of fun deflating Rust’s addlepated philosophizing; when he tells his partner that a dead body is a “a paraphilic love map,” or mentions that he can “smell the psychosphere,” Marty’s reaction is to tell him to “stop saying odd shit like that.” But it’s a spirit of amusement that dissipates as the show progresses, overwhelmed by the increasingly baroque mythos, Southern-baked stereotypes, and heavy confessional talk.

The problem, then, is not that these shows are serious, or even that they’re almost always serious. It’s that they expect the audience to be, too. In other words, the major flaw of True Detective or Game of Thrones is their monotone, the fact that they only ever ask for or permit from viewers a single, worshipful stance. It’s this allergy to camp—to deviant interpretations—that likely makes these shows so ripe for deflation. Both SNL and Key & Peele recently featured sketches spoofing the body count on Game of Thrones, while one of the liveliest debates about The Killing’s fourth season concerned Detective Linden’s chapped lips. Similarly, it can be hard to watch True Detective without recalling A.O. Scott’s comments about August, Osage County that its performers should win an award for “most acting.”

That said, in recent years there’s been an encouraging counter-trend: the embrace of a hybrid tone that, if hardly unique to contemporary television, may be emerging as a distinctive characteristic of post-network-era programming. In her roundup of the best 2014 TV, for instance, Nussbaum remarked in passing that the “distinction between comedy and drama” had dissolved. It could be premature to declare this erosion complete, given the entrenchment of so many current series on the dark, dreary side of the tonal spectrum. But it’s a worthy goal. If excellent tragicomedies like Enlightened, Getting On, Louie, and Transparent are any indication, new programs may increasingly aspire to move among tonal registers, rather than insist on wholeheartedly embracing one.

Life After No Child Left Behind

No Child Left Behind is really, really unpopular. Roughly three in 10 Americans think the George W. Bush-era federal education law has actually worsened the quality of education, according to a 2012 Gallup poll. The original law on which No Child Left Behind is based—the half-century-old Elementary and Secondary Education Act—was supposed to be renewed nearly a decade ago. Politics just kept getting in the way.

Congress appears poised to finally reauthorize the act and get rid of No Child Left Behind for good. Politicians on Capitol Hill are shooting for a compromise that avoids giving the feds too much clout while ensuring already disadvantaged children don’t get put at an even greater disadvantage. But they have a lot of work ahead of them.

The most promising proposal is a bipartisan bill—the Every Child Achieves Act—that the Senate began debating Tuesday after getting unanimous approval from rather unlikely allies on the education committee, including Rand Paul and Elizabeth Warren. Meanwhile, the House will be taking up a separate proposal to rewrite the law: the GOP-drafted Student Success Act, which was pulled off the floor earlier this year after it failed to garner enough support but could return for a vote as soon as Wednesday.

Both proposals could easily flounder, and senators were already clashing Tuesday over how accountable states should be to the federal government. “It’s far from a slam dunk,” wrote Education Week’s Alyson Klein. The Obama administration said it “can’t support” either of the bills as they stand because they “lack the strong accountability provisions that it is seeking,” according to The New York Times.

Why has No Child Left Behind left such a sour taste in people’s mouths? And how, if at all, would the proposed rewrites make amends?

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act, or ESEA, was designed to earmark extra funding for poor students—a program that would give the federal government a much greater role in classrooms. Giving disadvantaged schools an extra boost was certainly a worthy goal; it still is. Unfortunately, “the widespread challenges faced by children from low-income families in America remain extraordinarily difficult to tackle as they continue to struggle with vastly inadequate educational opportunities,” wrote Julian Zelizer, a Princeton history professor, for The Atlantic. The gap in test scores between students from lower- and higher-income families has grown by 40 percent since the 1960s.

Despite its bipartisan roots, No Child Left Behind, Zelizer argued, has done little to reverse those trends. Testing became the centerpiece of education reform, and schools faced harsh sanctions if they didn’t fulfill expectations. Teachers invested more time in test prep and less time in valuable instruction. Schools were shut down were in poor communities. Achievement levels are still greatly uneven.

Here’s a rundown comparing how the current law and proposed legislation (as of Tuesday) address some of the key challenges in American education today:

Testing

No Child Left Behind: The law mandates annual testing in math and reading for kids in grades three through eight as well as high school. Schools are expected to show progress in student test scores and face penalties if they don’t.

Every Child Achieves: The law would have the same testing requirements as No Child Left Behind. States would have to make test scores public, including data on how scores break down by race and income.

Student Success: Under this measure, states would be allowed to opt out of federal accountability requirements if they develop their own plans. (Education Week reports that the proposal now includes an amendment that would allow parents to opt their kids out of testing without those zeros counting against schools’ performance rankings.)

Standards

No Child Left Behind: The federal government uses test-score benchmarks as the standards against which schools are assessed.

Every Child Achieves: The law would explicitly prohibit the federal government from requiring states use a specific set of standards—i.e., Common Core. However, it would mandate that all states adopt “challenging” math, science, and reading standards that ensure kids are prepared for college or vocational pursuits.

Student Success: Similar to Every Child Achieves, the law would strictly prohibit the federal government from prescribing (or incentivizing states to adopt) standards such as Common Core.

Teacher Evaluations

No Child Left Behind: No Child Left Behind required all teachers to be “highly qualified.” In exchange for waivers from key aspects of law, which a majority of states have sought, the DOE required states to evaluate teachers. These typically rely at least partially on student test scores.

Every Child Achieves: Under this proposal, states wouldn’t be required to evaluate teachers nor use test scores as a metric for assessing them.

Student Success: The law’s stipulations would be similar to those outlined in the Every Child Achieves Act.

Economic Segregation of Schools

No Child Left Behind: Under No Child Left Behind, schools with the highest concentrations of low-income students receive extra funding. The theory is that targeting money at high-poverty schools helps lift them—and their students—out of poverty. But research suggests that the extra funding doesn’t always compensate for the various social disadvantages associated with attending high-poverty schools, such as student and parent engagement and higher teacher expectations.

Every Child Achieves: The Senate proposal would largely retain No Child Left Behind’s funding formula, though the Department of Education is expected to promote provisions that would encourage economic diversity.

Student Success: The bill includes a school-choice provision that would make public money “portable,” allowing it to follow low-income children to different public schools. Democrats tend to oppose this tactic, arguing it would shift money from poor schools to rich ones.

Local Control

No Child Left Behind: The federal government plays a large role in determining what defines a struggling school and prescribes the sanctions applied to such schools.

Every Child Achieves: The law would shift to the states decisions about how test scores are used to assess school and teacher performance. It’d be up to states to determine how to improve struggling schools. This is a major reason civil-rights groups say they don’t support the existing legislation.

Student Success: The law would give states significant control over accountability.

The California Democrat Setting the National Agenda

After President Barack Obama called for paid sick leave in his most recent State of the Union address, most progressives praised his leadership. Lorena Gonzalez thanked him for finally following her lead.

When Gonzalez, a California state assemblywoman, wrote a law making California the first state to guarantee paid sick days for all private-sector workers, it was a bold and controversial move. It passed last September. Fast-forward six months and paid sick leave has gone from “pet Democratic cause” to legislative reality in several states. Gonzalez, who's been in office just two years, has campaigned for paid sick-leave measures in other states and consulted with lawmakers around the country on how to replicate her work. Obama’s call for action remains unfulfilled; Gonzalez’s law took effect last Wednesday.

In addition to paid sick leave, Gonzalez has had a hand in many of the high-profile laws to come out of the state in the last two years. Among the bills Gonzalez has written or co-written are measures that would massively expand voter rolls by automatically registering all eligible Californians with driver's licenses to vote; offer workplace protections to NFL cheerleaders and grocery store workers; require most public schoolchildren to be vaccinated; and eliminate taxes on diapers. The breadth and scope of her legislative efforts have helped catapult her ahead of California's two powerful U.S. senators, its up-and-coming attorney general, and its first gay woman to serve as speaker of the Assembly to become arguably the state's most influential female politician.

"Some people get to Sacramento and have to figure out where the bathrooms are. She knows where the bathrooms are. She didn't waste a lot of time," said Joel Anderson, another member of the San Diego delegation in the state senate. Anderson is as conservative as Gonzalez is progressive, but he’s become an unlikely ally.

"Some of my legislation, I get ribbed a little that it's not serious. Which is funny to me, because, like, have you ever went and talked to somebody about what matters in their life?" Gonzalez, who spent most of her career as an organizer and labor leader, told me. "They'll say with the diapers tax, 'Oh that's only $100 a year.' Well that may not mean a lot to you, but that means a lot to my neighbors. How do we get past this idea that big policy only has to do with infrastructure or water or rainy day funds?”

Many of Gonzalez's bills die before making it to the governor's desk, including one that would have doubled pay for employees forced to work certain holidays and an earlier version of the diaper bill that would have made them a welfare benefit. But even her failed efforts still get outsize attention. One reason why: She pays as much attention to the media as it tends to pay her. She decided to focus on diaper affordability after reading a Huffington Post article on families who struggle to afford them. As the debate over Confederate flags heated up in the aftermath of the Charleston church shooting, Gonzalez found a way to inject San Diego (and herself) into the conversation, calling on local leaders to rename Robert E. Lee Elementary School. She wants to turn her attention next to labor protections for California nail-salon workers, an effort inspired by an explosive New York Times story about the exploitation in New York and New Jersey salons.

At this point, you'd be forgiven for wondering the obvious: How hard can it be to pass progressive legislation in progressive California; to support working women in a state that is known for doing just that?

In some cases, it’s harder than you might think. "It is a downhill slope for a progressive in the Legislature. That said, it is fairly unusual for a newer member to make so much of an impact so quickly," said Dan Schnur, the director of the Jesse M. Unruh Institute of Politics at the University of Southern California.

Although California as a whole votes reliably Democratic, its state legislature is much more politically diverse, and infighting can hold up legislation. Attempts to reform the state's landmark environmental law and another law that limits welfare benefits have drawn wide bipartisan support, yet keep stalling after years of effort.

Because she represents a solidly Democratic district—she ran unopposed in her first re-election effort in 2014—Gonzalez has had the luxury of being able to pursue her agenda without fear of voter backlash. But her tendency to gravitate toward controversial topics has cost her some opportunities to shore up support from those who'd otherwise be natural allies.

Gonzalez said she almost withdrew from the Women's Legislative Caucus last year when the group declined to support the paid sick-leave legislation, even though groups like The Shriver Report on women and poverty list paid sick days as the single largest reform that could be made to improve working women's lives.

On both sides of the aisle, Gonzalez earned a reputation for being publicly combative but privately conciliatory."This year [the Women's Caucus] is doing a little bit better. They're doing the backlog of rape kits, which is really important, but it's not controversial. So everybody of course supported that. I think it's easier to get together and have priorities that are not controversial," said Gonzalez.

Gonzalez finds herself in an unusual political position: She’s a progressive who can win over conservatives, but who often has trouble playing nice with other progressives. As a result, she’s been snubbed in terms of committee assignments and was yanked from a high-profile committee earlier this year. "People say, 'Oh but we're all Democrats,' and it's like yeah, wait till you talk to some of these Democrats,” she explained. “They're my friends, but we're coming from different places in life.” On both sides of the aisle, she’s earned a reputation for being publicly combative but privately conciliatory.

The state's raucous debate over mandatory vaccination is the latest example of her unique approach. Gonzalez is co-author of a bill signed by Governor Jerry Brown this week that removes the personal belief exemption from California's vaccine laws, which allowed parents to forgo vaccinating their children without a medical reason. Video of Gonzalez aggressively questioning opponents over their claims of how the bill would deal with immigrants—her district borders Mexico—went viral. She also publicly sparred with actor Rob Schneider, a vaccine denialist, on Twitter.

But few people know about another celebrity vaccine encounter that went differently. During the California Democrats Convention in May, Gonzalez slipped out with some staffers to grab lunch. They were sitting at a communal table inside a restaurant when some women squeezed in next to them. One of them was the actress Jenna Elfman. Elfman's group noticed the various stickers and pins Gonzalez and her team were wearing for the convention, including one that said "I (heart) immunity." Elfman, who was there to protest the vaccine measure, asked if she and Gonzalez could talk about the issue. Despite the public rancor surrounding vaccines, their discussion was polite and friendly.

"She was the most reasonable person I've had a discussion with on this," Gonzalez said about her discussion with Elfman. "It was very civil compared to everything else. She was a nice woman, just wrong."

That willingness to engage behind the scenes is also how Gonzalez won over Anderson on two bills that she co-authored. One measure would eliminate taxes on diapers; the other one cracked down on fraudulent legal-services companies that prey on immigrants seeking help in obtaining U.S. citizenship. "We don't agree on how to address the immigration issue, but we agree nobody should be exploited," said Anderson. "She invested time to figure out who I was as a person and then she pitches her ideas in a way I can understand. That's not normal. Most people in the majority usually dictate—'I need you to vote this way.'"

It's a much different portrait than the one of Gonzalez that usually surfaces in the media. That version of Gonzalez was the only San Diego-area lawmaker who spoke out in favor of a bill that would have ended killer whale performances at SeaWorld San Diego. That portrait of Gonzalez seethed at a vaccine opponent who'd asked in a committee hearing how immigrant children could prove they'd been vaccinated. "You know, other countries actually document vaccines. I know it's incredible but Mexico requires it for school as well," she told him. That portrait of Gonzalez throws shade at the Democratic speaker of the state assembly on Twitter.

Gonzalez seemed to revel in the hate mail and nasty phone calls that poured in as a response to her first failed diaper bill. "I had two older brothers, so I always say, 'You can say anything to me because I promise you they've said something worse,’” she explained. "Plus, we were working class, so you constantly have to deal with things like, 'So what, I'm wearing $5 shoes from K-Mart, leave me alone.' You become one of two things: You're either very embarrassed, or you're like, ‘No, none of that matters.’"

Gonzalez said that she’s mindful of working-class families like hers when she considers which issues to take up. She first got the idea to push for paid sick days when she served as leader of the San Diego and Imperial Counties Labor Council. Gonzalez would attend celebrations for groups that had successfully unionized. When she asked people what made them excited to join a union, she was surprised by the most common answer. "What you heard time and time again wasn't wages, wasn't benefits, it was, 'Oh my gosh, I get sick days. I get days to go pick up my kids when they're sick.'"

At first, Gonzalez brainstormed ways to push universal sick days as a ballot measure, but didn't get very far. "How do you convince workers who already have sick days to put it on the ballot for workers who don't?” she asked. “So we were trying to work with various foundations, and then I get elected, and I'm like, 'Oh, I can write a law.'" Six months after it passed, President Obama pushed for the same policy nationwide. Sometimes, the unconventional approach works.

The Verdict on Charter Schools?

A few years ago, Pablo Alba was called to the principal’s office to meet with me, an aging white guy he’d never met before. A lanky sophomore, Alba volunteered little beyond a cautious glance upward as he plunked down before me, but he instantly perked up when I asked him about the typical freshman experience at San Francisco’s City Arts and Technology High School. I was conducting research on local organizing and what makes potent charter schools like City Arts work, and I wanted to hear about the student experience. “You make a lot of friends, it’s small,” Alba said, allowing a slight grin.

Alba, who had struggled at the conventional middle school he had previously attended, would thrive at City Arts over the next three years, thanks largely to the young teachers who tirelessly engaged their classes of restless teens. This small campus—which sits atop a knoll overlooking a sea of weathered, two-story flats—offers a relatively rare opportunity for blue-collar families: a shot at college for their kids.

The charter-school movement now serves roughly 2.3 million students nationwide at more than 6,000 campuses—schools that are primarily funded by taxpayers but free from the bureaucracy and tangled union rules typically found at regular public schools. But the movement, which enjoyed a vibrant growth spurt and turns 25 next year, no longer seems to espouse the same grassroots values that it once did. Charter-school management firms like Green Dot in Los Angeles and the Knowledge Is Power Project (KIPP) out of Houston—many of which were founded by dissident parents or educators—and large private donors now orchestrate key sectors of the movement. Most charter schools fail to push learning curves any higher than conventional schools do, a widely circulated (albeit controversial) Stanford University study suggested earlier this year.

“Quality matters more than originally thought, and it’s harder than it looks.”Politically, the movement continues to gain strength. New York’s governor, Andrew Cuomo, received campaign funding last year from hedge-fund managers who awarded $4.4 million total to pro-charter candidates across the state, according to The Huffington Post. Similarly, The Los Angeles Times has reported that the CEO of Netflix, Reed Hastings, and the housing developer Eli Broad (both Democrats) spent hundreds of thousands of dollars this past spring for each Los Angeles school-board candidate in support of charters.

But politics aside, when do charter schools lift students? What lessons do charter educators provide that could inspire traditional educators? Is this aging movement, first spurred by grassroots activists, drifting into middle-age regularity—losing its appeal among parents and its inventive edge among educators?

* * *

The charter-school movement began with a simple idea that traces back to a rather odd set of political bedfellows.

Albert Shanker, the late head of the American Federation of Teachers, spoke in 1988 to a gaggle of Minnesota policy thinkers, pitching what he defined as an easy way of liberating inventive teachers from the burdens of staid classroom routines, bland textbooks, and cumbersome union contracts. Shanker trumpeted the idea of granting charters to creative teachers, a concept that had already been floated in policy circles.

Ember Reichgott, then a 34 year-old state senator, listened keenly to Shanker’s pitch. “As a good Democrat I wanted to create new opportunities—innovative possibilities,” Reichgott, who wrote the country’s first charter-school law, later told me. But she aimed her efforts way beyond the union chief’s proposal, instead striving to charter entire schools in which principals controlled their budgets and hired and fired their own teachers.

Labor leaders struck back at Reichgott’s 1991 bill, painting it as a radical plan that had the potential to send public dollars to renegade schools with little public oversight. Abandoned by many of her fellow Democrats, Reichgott said she ultimately compromised on provisions limiting the number of new charter schools in Minnesota to six. Moreover, their establishment was contingent on whether the founding teachers could gain approval from local school boards and the state education commissioner, who at that time happened to be the teachers union’s former chief lobbyist.

Upon hearing of Reichgott’s near-defeat, Shanker penned a rather sardonic letter to his fellow charter enthusiasts: “The Minnesota bill seems to be traveling to other states,” he wrote. “I still see the baby in it, but the bath water has covered it up.”

The idea proved quite portable, soon finding its way into California, where another Democratic lawmaker, Gary Hart, further expanded the scope of this charter-school experiment. Hart said his number-one goal in 1992 was “to stop vouchers”—taxpayer-funded checks for parents that could be used to pay for private-school tuition. “I viewed charters as an alternative,” he recalled as I interviewed him in a Sacramento cafe.

Thanks in part to support from Republicans, Hart’s bill was passed, authorizing up to 100 charters statewide. He said he predicted they would yield “a little boutique reform, an R-and-D effort just like Shanker was talking about.” Still, Hart worried that charter schools would take hold in well-heeled areas (“places like Palo Alto”), while in urban centers “you would give a party and no one would come.” Things turned out a little differently than anticipated.

Bill Clinton, entering the White House in 1993, quickly embraced the idea of charter schools, touting their ability to “reinvent government” while pushing for grassroots accountability and the ability of parents discontented with traditional schools to vote with their feet. Clinton soon approved federal funding to build thousands of new charter schools.

The robust movement demonstrated how Clinton-era Democrats could spark experimentation in the public sector and mimic Silicon Valley's outside-the-box thinking. Now the Democratic party could look beyond teachers unions for campaign cash; wealthy progressives and Manhattan financiers could offset the loss of support for pro-charter Democrats from labor.

This new coalition of advocates would change minds coast-to-coast as support for charter schools flourished among local politicians and huge foundations. I attended a celebration of Oakland activists in 1998, where a staff aide to the late John Walton (the son of Walmart’s founder), a bible placed before him, conferred with black and Latino church leaders on how to expand charter schools citywide.

* * *

Do charter schools lift students as much as they reflect the aspirations of political activists and private donors? It seems that the abstract idea of charter schools began to outshine hard evidence on whether they were having a positive impact on student learning.

Established charter schools such as KIPP that have been in operation for years, along with those serving large shares of black and Latino kids, do often lift achievement at higher rates than do traditional counterparts. But charter campuses can limit the learning of white, urban students relative to their counterparts who remain in traditional public schools, according to Stanford’s Margaret Raymond, who tracked over 1 million charter students in dozens of cities over five years.

The abstract idea of charter schools began to outshine hard evidence on whether they were having a positive impact on student learning.Raymond—whose research methods, to be sure, have been widely disputed—found that charter students in a third of the cities featured in the study did worse than their regular-school peers in reading and math. I’ve found in my own research that many of the traditional campuses that reinvented themselves as charter schools, such as those in Los Angeles, appear to undermine the learning progress among children from middle-class families.

Again, certain charter schools—including those that have been able to retain strong teachers and offer longer school days—do help students thrive. The campuses run by KIPP, which has access to a range of public and private funding, yield strong results for kids of color. Another tracking study in New York City found stronger gains for charter pupils, relative to their peers in conventional schools.

Back in San Francisco, Pablo Alba’s story helps to illuminate the kinds of charter-school practices that do lift poor or working-class students. When I visited the campus one damp, foggy morning, I observed his 34-year-old history teacher, Danielle Johnson, standing beside her classroom door with a stern look as she awaited the arrival of two tardy girls to their “advisory period.” Inside the room, Alba and others proceeded to work on their “personal reflections document,” sharing with partners six personal attributes that stemmed from family or emerging passions inside school. Advisory period is a bit like homeroom for first-year students and is a place where teachers and kids get to know each other, where relationships take root.

“We see ourselves as generalists first—my real job is to be an advisor,” Johnson said, emphasizing the importance of “core values.” “If you can’t get these relationships down, the teaching isn’t going to happen.” Like Alba, Johnson took refuge at City Arts from what she described as huge, alienating urban schools. She now defines her role as a “warm demander” in the parlance of City Arts.

The mostly blue-collar students at City Arts spend plenty of hours over the year preparing for standardized tests in math and English. But the school’s core work involves hands-on projects, from designing a sustainable rooftop garden to creating a multimedia explication of Emiliano Zapata’s role in powering the Mexican Revolution. They present these projects to peers and parents at evening performances.

The writer Zadie Smith talks of how the lives of teenagers are based on “a relation with verbs, not nouns.” It’s a sentiment that teachers at City Arts—a Deweyian wonderland of sorts—understand, meshing lessons with the “core values” described by Johnson, whether that entails digging into personal challenges or tying their curricula to real-world projects.

Three years after we first met, Alba stood before a faculty panel for his final assignment, the capstone performance required for graduation from City Arts; his Peruvian mother sat in the second row. Alba dove into a presentation on a reflective art piece, a black-and-white sketch that he described by discussing his own personal growth. “In the beginning of ninth grade I was a very shy person,” he said. “But by the time I was in 12th grade I was able to make the most convincing arguments of my class.”

He then shifted to reporting on a lab experiment that simulated how oil slicks, like the Gulf BP disaster, can be chemically scrubbed clean. The presentation sparked a flurry of queries from three teachers who pressed for crisper logic, asking Alba to be more precise in explaining how he weighed the conflicting evidence. It was a Socratic grilling of sorts, reminiscent of how some elite private schools nurture growth on multiple fronts. But kids like Alba—many the first in their family to consider college—are seldom expected be capable of this range of learning. “Man, he’s like a smart machine,” one student said of Alba’s performance.

Charter advocates recognize that not all of their schools cultivate such rich learning and downright caring for kids. “Quality matters more than originally thought, and it’s harder than it looks,” said Don Shalvey, who created California’s first charter school and now works in Seattle for the Gates Foundation. “Choice is not enough. We must care about rigor and press for rigorous caring inside.”

* * *

Charter adherents also struggle to dodge claims that their schools exacerbate the segregation of students along lines of race or class, peeling off the more-motivated and affluent kids and parents. In New Orleans, where the vast majority of kids attend charters, district officials recently settled a lawsuit in which the plaintiffs, parents of students with disabilities, alleged that the schools violated federal law by discriminating against the special-needs kids, many of whom were also disadvantaged minorities.

“If you can’t get these relationships down, the teaching isn’t going to happen.”Still, charters today serve larger concentrations of poor families than do traditional public schools. Nonwhite students make-up at least 80 percent of enrollments in over two-fifths of all charter schools, roughly double that for regular public schools, according to a paper published with the National Bureau of Economic Research last month. Still, while advocates say charters tend to admit a more-heterogeneous array of students than do public schools, a growing body of research suggests the contrary. And one national study from RAND found that high-achieving white children often migrate into charter schools at higher rates than do their lower-performing white peers.

Meanwhile, the Reichgott- and Hart-era architects worry that the aging movement may start to exclude youthful, feisty innovators, like the teachers at City Arts. “I still see charters as R and D, a radical experiment,” spurring deep change within conventional schools, Hart said. “I could never see it like a religion,” as have some advocates who aim to make every school a charter school.

The loss of kids to charters has perhaps prompted some leaders at traditional urban schools to mimic the decentralization within the regular district system. Los Angeles has created a network of so-called pilot schools that are exempt from the kind of bureaucracy that too often produces mediocre teachers or promotes inflexible budgeting. Backed by labor groups—since pilot-school teachers retain healthcare and pension benefits—these small campuses compete for charter students.

Though they may display less fervor than they once did, charter activists continue to help diversify the nation’s landscape of schools; few parents yearn for the public-education status quo. A growing percentage of parents across the country now seek a school that’s outside their neighborhood attendance zone. The issue being debated in education circles is whether charters have gone “too corporate,” said the Gates Foundation’s Shalvey, but “thirtysomething parents don’t notice these debates. They simply see lots of options now.”

And whether America’s widening kaleidoscope of schools will one day elevate student learning overall or simply breed a patchwork of segregated schools remains a pressing question. But Shalvey may be right. A quarter-century later, charter schools offer worthy options for many parents, rich or poor. “I began teaching in the Summer of Love,” Shalvey said. “All those earlier education fads—team teaching, moving classroom walls around—quickly disappeared. The charter movement has stuck.”

Lil Wayne in Love

Lil Wayne feels good. We know this because the third song on his new release, Free Weezy Album, is called “I Feel Good.” It samples the “I feel good part” of James Brown’s “I Got You (I Feel Good),” and features Wayne saying likes like, “I feel good / I'm smoking that good / I feel good / my girl got that good / yeah!”

It’s certainly not surprising to hear a rapper thrilled with all the sex and drugs he has access to, but you can’t take for granted this particular rapper’s state of mind these days. His much-anticipated Tha Carter V album languishes on a computer somewhere, the victim of ugly fighting between Wayne and his longtime label boss and former mentor, Birdman of Cash Money Records. His output lately has been widely seen as inferior to the material of the late-Bush/early-Obama years when he credibly claimed to be the Best Rapper Alive. But FWA, released exclusively to Jay Z’s new streaming platform Tidal, is supposed to make people forget all that. The cover art is literal flames. “I honestly gotta say that this #FWA album is my best work yet!” he tweeted. “I won't let u down as a fan.”

Related Story

Rap Enters Its Psychadelic Phase

For the first couple tracks, the album is, if not flames, at least hot enough to generate some excitement that listeners are in store for classic Wayne—which is to say filthy, entertaining, hugely imaginative nonsense. More than ever, he appears to be writing off of self-created prompts, picking a keyword and riffing on it. For track 1, “Glory,” that keyword is “shit,” and what results is a revolting yet creative flood of puns about stenches, coffee, coffee-related stenches—at one point, he crowns himself “Porta-Potty Tunechi.” If the gross-out factor outweighs the entertainment factor for you, it’s probably best to turn back now. On the next track, “He’s Dead,” Wayne, using an oddly loping verbal cadence, buries his Cash Money career and walks the land as newly undead. Naturally, he says, “bitches want to sleep with my remains.”

But soon, the manic-spitter shtick begins to feel a bit put-on, hollow. “I Feel Good” squanders its no-doubt pricey James Brown sample by serving up a rap with next to no quotables. You could say something similar about “I’m That Nigga,” whose infectious beat recalls a malfunctioning cyborg but whose boasts crest, weakly, with, “I’m having foursomes / Don’t have to force ‘em.”

The truth is that the foursome talk does feel a bit forced. A remarkably large portion of the album devotes itself to songs of devotion—ballad backings with soaring melodic choruses around which Wayne mumbles about his main squeeze, whom listeners can assume is his girlfriend, Christina Milian. This doesn’t mean he’s no longer writing elaborate peans to oral sex, or that he doesn’t dis faceless “hos”—he just does those things to praise the girl he love.

It’s pretty relatable, even if the demands of hustling weren’t the reason your last relationship failed.In “Psycho,” he’s engaged in all sorts of stalker-boyfriend behavior, but gives it a strangely tender dimension by acting shocked by infatuation: “I never knew a girl would have me out here trippin' / I thought I was different, I thought I was pimpin.'” And on “Thinking About You,” he uses his hardened ex-con image for a mushy, summer-jam singalong—“I was chilling on a set / With a fully automatic tec / Thinking bout you, girl.” This isn’t the first time Wayne has written about romance, but for him to do so with such focus and consistency feels new and sweet. (Or maybe I’m just high off this video of Milian coyly confirming their relationship.)

It’s not just his current affair that has him feeling emotional. “Without You,” one of many FWA songs with a melodramatically sung hook aimed straight at 2010 radio, offers an honest confession about pining for the one who got away. It’s pretty relatable, even if the demands of hustling weren’t the reason your last relationship failed:

Do you ever miss me?

Do you ever wish we get it right and the rest is history?

I wish I could go back in time and fix my lack of time

Because back then I had to grind, but see you thought I’d rather grind

You thought I had the time, thought I was lying half the time

And now I fantasize and agonize to pass the time

The lovely closing track, “Pick Up Your Heart,” synthesizes Wayne’s romantic longing, streets origins, and present-day ambition, and helps to explain some of what’s come before. Over a muffled soul sample and strings, he talks about being worn out by people using him and by him using people—“I don't want to do it no more, no / But I got to get my paper baby.” For the album’s final moment, he delivers a spoken-word bit that references both a William Hughes Mearns poem and a Progressive Insurance commercial. “Yesterday I met a woman on the stairs that wasn't there,” he drawls. “… She said I think you think I think you think of us.” Then he makes a “hmm” noise. It’s a weird, ambiguous moment—is he talking about a lost lover? Success? A different life? You’re not sure how Wayne feels for a second and that, in itself, feels good.

The Death of the Hippies

In 1967, just after the Summer of Love, The Atlantic published “The Flowering of the Hippies,” a profile of San Francisco’s new youth culture. “Almost the first point of interest about the hippies was that they were middle-class American children to the bone,” the author noted. “To citizens inclined to alarm this was the thing most maddening, that these were not Negroes disaffected by color or immigrants by strangeness but boys and girls with white skins from the right side of the economy ... After regular educations, if only they’d want them, they could commute to fine jobs from the suburbs, and own nice houses with bathrooms, where they could shave and wash up.”

The 1960s through the eyes of The Atlantic

The 1960s through the eyes of The AtlanticRead More

A middle-class boy from the right side of the economy: That was my mother’s cousin Joe Samberg. When they were growing up, she spent every Thanksgiving at his family’s home in the upscale Long Island suburb of Roslyn Heights. His father was a successful businessman who, somewhat incongruously, had far-left sympathies. Throughout the 1960s, Joe and his four brothers became more and more radical. Two of the Samberg boys eventually went down to Cuba to cut sugar cane for Castro’s revolution.

In 1969, when Joe was 22, he moved out to California. By then, the Haight-Ashbury scene described in the Atlantic article had mostly migrated across the bay to Berkeley’s Telegraph Avenue. Rents were a little cheaper there, and for those who couldn’t pay rent at all, the weather was a little warmer. The college town was also more sympathetic to the long-haired kids who crowded the sidewalks day and night—talking, protesting, kissing, dancing, fighting, and taking lots and lots of drugs.

“What I find really interesting about this picture is the people standing on the sidelines,” says Joe. “The guy on the right, with the Dutchboy haircut, is trying to be a peacemaker. Then you go all the way to the left, and you see this guy in a tie-dyed shirt just kind of like, ‘Ho hum, this is interesting,’ smoking his cigarette. Then there are the three black girls holding onto each other, really pulling for the black guy, Archie, to win. And then there’s one of the young white girls, Vanessa—the thing that seems to fascinate her is how the black girls are so anxious about the fight. Archie did win the fight, incidentally, but really, both of these guys just sort of collapsed from fatigue.” (Joe Samberg)

“What I find really interesting about this picture is the people standing on the sidelines,” says Joe. “The guy on the right, with the Dutchboy haircut, is trying to be a peacemaker. Then you go all the way to the left, and you see this guy in a tie-dyed shirt just kind of like, ‘Ho hum, this is interesting,’ smoking his cigarette. Then there are the three black girls holding onto each other, really pulling for the black guy, Archie, to win. And then there’s one of the young white girls, Vanessa—the thing that seems to fascinate her is how the black girls are so anxious about the fight. Archie did win the fight, incidentally, but really, both of these guys just sort of collapsed from fatigue.” (Joe Samberg) Joe was part of it all, but he was also slightly outside of it, watching everything through the lens of his camera. Years later, when he was a highly regarded professional photographer—after he’d settled down and raised three children (including the comedian Andy Samberg)—he showed me some of his early portraits from Telegraph Avenue. They’ve been in my mind’s eye ever since, a counterpoint to all the popular images of peace signs, daisy chains, and Aquarian circle dances. The reality Joe saw was very much like the one the Atlantic author described: hordes of kids who had been lured to California by utopian ideals and then settled into a life of sex, drugs, and lethargy.

Joe often quips that he headed out west for the same reasons as Jojo in the Beatles song: “for some California grass.” But like most kids who landed in the San Francisco area during the late 1960s, he had very personal reasons for leaving his old life behind. In 1965, his college girlfriend was killed in a car accident just as they were starting to talk about marriage. Six months later, his mother died of cancer. “I really started to sink,” he says. “I couldn’t concentrate. I couldn’t find anything about school that would hold my attention for very long.”

So he dropped out of Emerson College and moved down from Boston to Manhattan, where he found work at a color lab in midtown. He spent his free time in Harlem, seeing James Brown and other R&B singers at the Apollo Theater, or in the rough alphabet streets of the Lower East Side, hanging out in Andy Warhol’s orbit. He watched the Velvet Underground play at the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, then went back to dilapidated apartments to snort meth. “What I was doing was grieving,” he says now. “But I was too young to understand that. All I knew was I was desperate to feel good again.”

Left: Kids walk up the steps of the “Telegraph Hilton,” a run-down boarding house above a clothing store called Rag Theater. Right: Two guys trip together on the curbside. “My dad sent me $200 a month, which I used to pay rent for an apartment my brothers and I shared. I managed to eat for almost nothing. There were places where you could get rice plates for a dollar, and a lot of days, one of those was all I ate.” (Joe Samberg)

Left: Kids walk up the steps of the “Telegraph Hilton,” a run-down boarding house above a clothing store called Rag Theater. Right: Two guys trip together on the curbside. “My dad sent me $200 a month, which I used to pay rent for an apartment my brothers and I shared. I managed to eat for almost nothing. There were places where you could get rice plates for a dollar, and a lot of days, one of those was all I ate.” (Joe Samberg) In 1969, just after he got laid off from his job, his youngest brother, Frank, came to town. Frank had been living out in Berkeley, and he persuaded Joe to head back there with him. The drive took three or four days, almost all of it through dreary, frozen fields. They crashed on a floor somewhere in Ohio. In Wyoming, after they locked themselves out of their car, the local sheriff let them in, looked them over, and then told them never to come back to town. They crossed the Sierras during a blizzard, barely able to see the road. Eventually, they felt their car heading downhill instead of up.

“And then,” says Joe, “all of a sudden, we found ourselves in this lush valley. It looked like a first-grade primer. The hills were rolling and green, all soft and curved like the beautiful body of a young woman. The sky was perfectly blue. And the clouds were all puffy, you know? Pure and white and glowing. I almost wondered, ‘Did we run off the road and fall into paradise?’”

When they pulled into Berkeley, the hippies were everywhere—standing on every corner, lining every avenue. Joe had never seen anything like it. “People don’t really understand this now, but at that time, in most of the country, you couldn’t have long hair and not be in danger of being beaten up,” Joe explains. “In Boston, cars used to come screeching to a halt and guys would jump out and want to kill me. I’d have to run.” Even in New York, whenever he left Greenwich Village, “I was continually harassed, spit on, and shoved around.” And Joe wasn’t even really a hippie. “I was hip,” he says. “That meant boots, black jeans, a black t-shirt, a leather jacket—the kind of thing you’d maybe see the Rolling Stones wearing.”

“In this picture, you can see that all of the Krishnas have their heads shaved except the most flamboyant one, who has long blond hair,” says Joe. “The story I heard was that he was from Hawaii, where the Krishnas didn’t have to shave their heads. The others were standoffish—they felt that his long hair showed vanity. So he was on the outs with them.” (Joe Samberg)

“In this picture, you can see that all of the Krishnas have their heads shaved except the most flamboyant one, who has long blond hair,” says Joe. “The story I heard was that he was from Hawaii, where the Krishnas didn’t have to shave their heads. The others were standoffish—they felt that his long hair showed vanity. So he was on the outs with them.” (Joe Samberg) In California, the flower-child style was at its apex. “People had really developed their individual looks,” he says. “They were no longer trying to figure out what being a hippie meant. I found that really stimulating. It made a great subject for a photographer—even though, by any middle-class standards, these people were living totally miserable lives.”

Joe found a place to live and began spending his days out on the sidewalk. “I didn’t really own any clothes other than the ones I had on,” he says. “I hardly ever ate. Whenever I had money, my priorities were drugs, film, and food—in that order.”

There were two types of drug users on Telegraph Avenue. One group unapologetically shot heroin. The other group took mind-altering drugs but believed that opiates were a sinister way for The Man to keep poor people from climbing out of the ghetto. At first, some of the kids put up signs declaring, “No heroin dealers here.” Over time, Joe says, those signs came down and more and more people started using hard drugs. “All that stuff about consciousness was just sort of dropped.”

“You see these kids drinking Southern Comfort? Those two bottles appeared and disappeared in what couldn’t have been more than two minutes. These kids were 13, maybe 14. But they just consumed anything that would come their way.” (Joe Samberg)

“You see these kids drinking Southern Comfort? Those two bottles appeared and disappeared in what couldn’t have been more than two minutes. These kids were 13, maybe 14. But they just consumed anything that would come their way.” (Joe Samberg) Looking at Joe’s pictures, it’s clear how young some of those addicts were. One group of junior-high-aged girls, known as the Mini Mob, often showed up in Mickey Mouse t-shirts. “There were people there who had those young kids very much in their thrall,” says Joe. “They told them, ‘Listen, you don’t need to go to school. Everything you need to learn in life is right here on the street.’”

A lot had changed in Berkeley since 1964, when thousands of students—many of them wearing suits and ties—gathered at Sproul Plaza to champion civil rights and demand free speech. Campuses had been the sources of the counterculture’s boldest ideas, the places where young activists mobilized to fight segregation and the Vietnam War, taking classes in political theory and Eastern philosophy.

Left: A Christlike figure perches on a garbage can. Right: A top-hat-wearing local character called Groovy (since deceased) parades down the avenue with some of his many friends. “There was still this spark of an idea of a new society, a better way to live. But all of that was on the decline.” (Joe Samberg)

Left: A Christlike figure perches on a garbage can. Right: A top-hat-wearing local character called Groovy (since deceased) parades down the avenue with some of his many friends. “There was still this spark of an idea of a new society, a better way to live. But all of that was on the decline.” (Joe Samberg) Now, college dropouts were congregating with misfits and runaways on the other side of Sather Gate. The outrage was still there, but the issues were murkier. While Joe was hanging out on Telegraph Avenue, his brother Paul published an anthology of underground newspaper diatribes called Fire! Among other things, the book ridiculed the whole idea of higher education:

College is a fantasy in the suburban mind of Mr. and Mrs. Work-Hard-Our-Life-Is-No-Fun-But-the-Kid-Will-Get-What-We-Can’t-Afford. The campus is a cultured nest egg where I-Don’t-Understand-He’s-Always-Been-a-Good-Boy and Oh-No-She’s-Not-That-Kind-of-Girl stroll hand in hand up the ladder to success, their tender heads floating in the lessons of the gentle professor. Only the kids never saw the professor. He was in his lab developing the new improved tear gas the kids are coughing under while the university president sits above it all.

Protesters tear down the chain link fence surrounding People’s Park. “In our house, there were always socialist publications lying around,” says Joe. “I read them all and I understood it all. I just never really believed in it to the same extent as the rest of my family.” (Joe Samberg)

Protesters tear down the chain link fence surrounding People’s Park. “In our house, there were always socialist publications lying around,” says Joe. “I read them all and I understood it all. I just never really believed in it to the same extent as the rest of my family.” (Joe Samberg) Even at the time, though, Joe says he was “too sarcastic” to fully buy into the radical agenda. “The average person on the avenue was almost completely ignorant politically,” Joe says. “All they really cared about was drugs, drugs, drugs. They were nihilists and hedonists. They just supported anything that was against the establishment. There was no intellectual foundation. The spirit everyone had talked about—the feeling of love and new age and progressive politics—was dying a miserable death.”

Joe eventually got married, started a family, and settled into a middle-class existence, but he never moved away from Berkeley. There are still homeless people hanging out on Telegraph Avenue, but as Joe points out, they barely even pretend to be hippies anymore. The movement itself is dead, and so are are many of the people who used to frequent the strip.

Over time, Joe says he watched “mind-expanding” drugs give way to more and more heroin. “I never had the wherewithal to be a full-fledged drug addict,” says Joe. “I never had enough money. And I was never willing to sell my camera.” (Joe Samberg)

Over time, Joe says he watched “mind-expanding” drugs give way to more and more heroin. “I never had the wherewithal to be a full-fledged drug addict,” says Joe. “I never had enough money. And I was never willing to sell my camera.” (Joe Samberg) “That was my problem with the whole thing,” says Joe. “There’s no growth for people if they’re continuously on drugs. It started out with all this higher thinking—expanding your mind to become more conscious of what’s really going on in the universe. But once the drugs took over, all of those big ideas disappeared.”

The author of the Atlantic article, Mark Harris, reached a similar conclusion. He was a generation older than the Baby Boomers, but as a white New Yorker who wrote for Ebony and The Negro Digest, he was highly sympathetic to the youth activism of the 1960s. He just didn’t think the hippies, in particular, were bringing about any meaningful change. Drugs had stunted their emotional development, leaving them at the mercy of “their illusions, their unreason, their devil theories, their inexperience of life, and their failures of perception.” Instead of promoting brotherhood and equality, they’d taken over public spaces, picked all the flowers in Golden Gate Park, and refused to turn their music down to let their hardworking neighbors sleep. And as they begged for money and frequented free clinics, these children of the suburbs siphoned away resources away from the urban locals who needed them most.

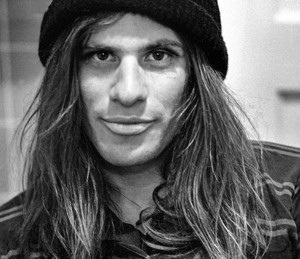

Joe in 1970 (Margie Samberg)

Joe in 1970 (Margie Samberg) Still, the hippies did end up having a lasting impact on American culture—even if it wasn’t quite the one they’d had intended. “After a while, I started to notice something,” Joe says. “All those people who used to want to beat the hell out of me because of my long hair—now their hair was long!” In the mid-1970s, when Lynyrd Skynyrd sang “Sweet Home Alabama” at the Oakland Coliseum against the backdrop of a giant Confederate flag, they looked oddly similar to the hippies of Telegraph Avenue. “So, yeah,” Joe concludes. “I guess there was a revolution.”

July 7, 2015

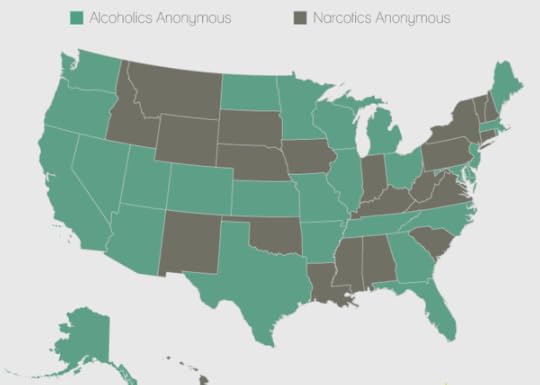

Why More Women Are Turning to Heroin

Throughout the history of modern medicine, substance-abuse researchers have focused their investigations almost exclusively on men. It wasn't until the 1990s that scientists, prompted by federal funding aimed at enrolling more women in studies, began widely exploring how drug dependence and abuse affects women.

And it turns out that gender differences can be profound.

Women tend to become dependent on drugs more quickly than men, according to the most recent data from the Substance Abuse Mental-Health Services Administration. This is especially the case among those who abuse alcohol, marijuana, and opioids like heroin. Women also find it harder to quit and can be more susceptible than men to relapse, according to Harvard Medical School.

Heroin use has increased dramatically in the United States in the past decade. A new report from the Centers for Disease Control finds heroin use has increased across all income levels and in most age groups.

About 9 percent of those surveyed said heroin would be “fairly or very easily available,” according to the most recent Health and Human Services data. Three in 1,000 Americans report having used heroin in 2013, the most recent year for which data is available. That’s up from two in 1,000 people who reported using heroin a decade ago, according to the Associated Press, and represents 300,000 more heroin users in a span of 10 years. Heroin use among women doubled in that time.

“We have seen increases in groups such as women, non-Hispanic whites, higher incomes, and the privately insured,” said Eric Pahon, a CDC spokesman. “These new demographic groups closely resemble the populations with high rates of prescription opioid abuse in the past 15 years.”

In many cases, people are thought to be turning to heroin as a cheaper alternative to prescription pain pills. Nearly half of people who reported using heroin were also addicted to opioid painkillers, the CDC reported.

Related Story

“We also know that the supply of heroin in the United States has increased substantially in the last few years and law enforcement reports indicate that heroin is showing up in communities where it has not typically been found,” Pahon told me. “These demographic shifts highlight the importance of reaching physicians with messages about appropriate prescribing of opioids, identifying people with problematic use as early as possible.”

Women face other risks associated with heroin. They're far more likely than men to be introduced to heroin injection by a sexual partner, and women report feeling more influenced by social pressure as a result, according to a 2010 study by the National Institutes of Health.

One key difference: Women often take heroin in smaller doses than men do, which may explain why men are more likely to die from overdoses. The number of overdose deaths involving heroin was nearly four times higher for men than it was for women in 2013, according to the CDC.

But with increased use among women, that may change. Since 2002, heroin deaths in the United States have quadrupled.

Why Would a Fighter Jet and a Little Cessna Be in the Same Part of the Sky?

Mid-air collisions are among the rarest but most horrific aviation perils. The most famous collision involving airliners in the United States, the crash of planes from United Airlines and TWA over the Grand Canyon nearly 60 years ago that killed everyone on board, led to dramatic changes in U.S. air-traffic control procedures. (There were two other U.S. airline collisions in the 1960s). In 2002, a Russian passenger airliner and a DHL cargo jet collided over Überlingen, Germany. Investigators eventually traced the cause to shortcomings in the Swiss air-traffic control system. Two years later, a Russian architect whose wife and children had died in the crash stabbed to death the Swiss controller who had been on duty at the time, even though an investigation had found the controller not personally at fault.

In the statistically much riskier world of non-airline, “general aviation” flight, collisions are also statistically rare. The most authoritative source in this realm is the annual Joseph T. Nall Report from the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association. (AOPA is known as the NRA of the skies for its effective lobbying on behalf of general aviation; as a member, I’m entitled to say so.) According to the latest report, in 2013 general-aviation airplanes were involved in 948 accidents of all sorts, 165 of which were fatal. (The accident rate has steadily gone down.) Typically 1 to 2 percent of the total, 10 to 20 per year, involve collisions. So in practice mid-air crashes are not a major source of risk; but when you’re flying, you spend half the time scanning the surrounding air to see who might be headed your way. (Also, if you’re on an Instrument Flight Rules, IFR, flight plan, the controllers are supposed to be keeping planes separated. Pilots on Visual Flight Rules flights have official responsibility to “see and avoid” other traffic. But with a “flight following” service, controllers can help by calling out traffic in the vicinity. Despite their tips, it is much, much harder than you would think to spot other little planes in the big sky. Many modern planes have traffic-detection systems, like the one in my Cirrus. By 2020 most planes will be required to have an advanced traffic-avoidance system called ADS-B, which you can read more about here.)

* * *