Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 397

July 7, 2015

Outrageous Humor Is an American Tradition

Whether you found it brilliant or offensive, Louis C.K.’s Saturday Night Live monologue from May’s season finale made it abundantly clear that things were very different in the 1970s. Racism was as pervasive as polyester, and the average suburban neighborhood was only mildly ruffled by the presence of a child molester on the block. C.K.’s town predator never took a particular shine to the comedian, he recalled, but did try and lure a number of his boyhood friends with the promise of McDonalds. “This is a true story,” C.K. said, hardly suppressing his own chuckles.

By the end of the bit, the audience’s uncomfortable groans had overpowered their laughter. “How do you think I feel? This is my last show probably,” C.K. quipped. The bit earned mixed responses on social media, with many claiming he’d crossed a line by comparing child molestation to eating candy bars. Closing out the show’s 40th season, the material was certainly edgier than anything audiences had seen on SNL in a while, but that’s not necessarily saying much.

In June, the film critic A.O. Scott suggested in a piece for The New York Times that America is in a “humor crisis.” “The world is full of jokes and also of people who can’t take them,” he wrote. “We demand fresh material, and then we demand apologies.” Fittingly, just a few days after the article’s publication, Jerry Seinfeld appeared on ESPN and declared political correctness to be comedy’s mortal enemy. This prompted polarized responses, from a Daily Caller piece titled “The Left’s Outrage at Jerry Seinfeld Proves His Point” to a critique by Salon’s Arthur Chu. “Yes, a stand-up comedian is crying political oppression because people didn’t laugh at his joke,” Chu wrote, “and because his infallible comic intuition tells him the joke, in a world undistorted by politically correct brainwashing, would be objectively hilarious.”

Given the renewed frenzy in the debate surrounding the (mis)placement of comic boundaries, the history of two great American comedic institutions are ripe for exploring how sensibilities have changed when it comes to humor. One is, of course, SNL, which considered its approach to comedy revolutionary when it began in 1975. The other is the show’s one-time contemporary, the influential but now-defunct National Lampoon magazine, which gave SNL some of its biggest early stars. A pair of new documentaries about the respective humor behemoths—Boa Nguyen’s Live From New York! and Douglas Tirola’s Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead—offer some timely and compelling context for understanding how social changes and technological shifts have changed the milieu for contemporary American comedy. As both films show, today’s artists aren’t saying anything more shocking than their predecessors: The history of comedy over the past 50 years is steeped in offensiveness, but it’s that willingness to cross lines that has led to some of the most meaningful subversion in popular culture.

* * *

Though perhaps best remembered for producing films like Animal House and Family Vacation, the National Lampoon began in 1970 as an offshoot of the Harvard Lampoon. A wild mix of bawdy boys-club humor and sharp political satire, the magazine reached its apex in the mid-‘70s, spawning album recordings, a live theater show, and its nationally syndicated radio hour. There’s a telling little nugget in Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead that credits the brand’s failure to put John Belushi on retainer as the primary reason for SNL’s early success. It’s an oversimplification, to be sure, but it many ways it was a classic case of video killed the radio star: Once Belushi was poached by NBC, Gilda Radner, Chevy Chase, head writer Michael O’Donoghue, and eventually Bill Murray followed suit. The National Lampoon Radio Hour died out completely and the magazine began to unravel, before going out of circulation in 1998.

But at its inception, the Lampoon began with the goal of using humor to take on (and take down) the establishment. In the midst of Vietnam and the Watergate scandal, the magazine’s original staff—mostly young, whip-smart (white) men, firmly believed that America was in desperate need of a stern wake up call and that offending people was merely an inescapable part their job as humorists. Comedy was a means of sublimating their rage against the country’s policy makers and power structures. As O’Donoghue puts it in an archival interview in Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead, “We’re doing this instead of hitting you in the face.”

Related Story

Swear Words, Blasphemy, and Justin Timberlake

And people noticed. Despite the recent outcry over the dangers of political correctness, the National Lampoon saw plenty of backlash during its day: The host of talking heads in Tirola’s film fondly recalls angry letters accusing them of being sexist, racist, and generally a bunch of filthy animals. But for them, getting a rise out of people was precisely the goal, and the magazine was steadfast in its dedication to what it saw as a decidedly non-partisan approach to humor. For the writers, it was important to make fun of everyone and everything with equal impudence—Jews, African Americans, Catholics, Muslims, homosexuals and heterosexuals, the political left and the political right. Taboos were meant to be talked about, and nothing was off limits—sex, race, religion, incest, or abortion.

Like its spiritual successor, SNL, National Lampoon was at its best when it focused its energy on the social and political hypocrisies of the time. One particularly noteworthy piece of satire from the magazine’s early years was the “Vietnamese Baby Book” whose pages were marked with important milestones like “baby’s first wound” and “baby’s first funeral.” There was also a segment featuring children’s letters to the Gestapo (“Dear Heinrich Himmler: How do you get all those people into your oven? We can hardly get a pork roast into ours”) and a faux advertisement asking for donations to help bolster the sadly dwindling funds of the Klu Klux Klan (“The Klu Klux Can … with your help.”)

National Lampoon’s idea of good comedy also came with the implicit mandate of punching up, not down—or the idea of targeting those in positions of power in society, as opposed to the defenseless or already downtrodden. Take, for example, the mock vice-presidential campaign ad featuring an image of Nelson Rockefeller gleefully blowing someone’s head off with a pistol. The caption reads: “Bye Fella! I’m Nelson Rockefeller and I can do whatever I want!”

Things become more complicated when jokes broach subjects like race, religion, and gender. At one point in Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead, the discussion turns to a particularly cringe-worthy cover with a grotesque cartoon titled “Kentucky Fried Black People.” The editors had intended the cartoon as a comment against racism not as a racist work, but how do you measure the intent of a joke? Distinguishing between “solidarity and aggression” is difficult, as Scott points out in his Times piece: “It can be virtually impossible to make a joke about racism that isn’t also a racist joke.”

* * *

Catering to the same demographic, SNL in many ways picked up where the Lampoon’s Radio Hour left off—and the show has, quite remarkably, managed to stay relevant for nearly half a century. As Nguyen’s documentary shows, SNL was born out of a very specific time and place—namely, New York City in the 1970s: a time when CBGB was a booming venue and young talent could actually afford to rent spacious lofts with high ceilings. As the former writer Anne Beats (also a Lampoon transplant) notes in an interview in the film: “People actually came here to make it.” Indeed, Beats—as well as cast members such as Radner, Murray and Chase—was already settled in New York and happily working for the Lampoon’s Radio Hour by the time the show launched in 1975.

Like its spiritual successor, SNL, National Lampoon was at its best when it focused its energy and attention on the social and political hypocrisies of the time.The medium, of course, is a huge part of SNL’s message. When the show entered the scene in 1975, the television landscape was largely sterile, scripted, and for the most part, whitewashed. Considered against the backdrop of primetime TV, SNL aimed to be revolutionary by airing live. There was a “sense that it was time to destroy TV,” former cast member Chevy Chase says in the film, and that late-night slot provided the perfect space for contained subversion.

Consider the well-known word-association skit from SNL’s inaugural season: Chase is interviewing Richard Pryor for a job, and the final task involves a psychological test in which Pryor is instructed to blurt out the first word that comes to mind based on a prompt. Chase moves from benign nouns like “rain” to racial slurs like “tarbaby” before escalating to “the N-word,” meanwhile Pryor, his face twitching with rage, matches Chase with his own insults—“honky,” “cracker,” and eventually “honky honky!” By the end of the skit, Chase’s character is so overcome with white guilt that he not only gives Pryor’s character the job, he raises his salary and gives him two weeks paid vacation before he even starts. “It’s funny how things have changed,” Nguyen told me. “They had the word-association sketch back in the day, and they said the n-word on television. Nowadays that would be totally censored.”

And he has a point: While the show’s format has remained remarkably consistent for 40 years, the way in which viewers consume it has changed dramatically. It’s redundant at this point to state that comedy, like everything else, lives on (and largely for) the Internet. With bite-sized highlights available on Hulu and YouTube the morning after, the deviant appeal of SNL’s midnight time slot, not to mention the immediate thrill of live television, has been all but obliterated. A notably bummed-out Amy Poehler sums it up nicely in the film: “SNL: the show your parents used to have sex to that you now watch from your computer in the middle of the day. Is that good?”

Whether or not it’s good is perhaps beside the point—it certainly makes things more complicated. As Scott points out, the ubiquity of the Internet has ensured that we’re now all in the same room together at all times, and joke-telling is no longer the comfortably segregated business it once was. “The guys at a stag smoker could guffaw at dirty jokes about women without the awkwardness of having real women present,” Scott writes. “Racist humor could flow freely at country clubs where the only black faces belonged to waiters and caddies. With a few exceptions, African-American humorists plied their trade on the chiltlin circuit, and Jews mostly stuck to the borscht belt.”

Considered against the backdrop of primetime TV, SNL aimed to be revolutionary by airing live.In one of the most telling scenes in Live From New York!, the camera catches up with the current cast member Leslie Jones directly after she performs a controversial bit on “Weekend Update” in which she theorizes that had she lived in the days of slavery, she would’ve had a better sex life. Not that she wants to go back there, she clarifies—of course not. All she’s saying is that as a tall, strong, woman, she would have been considered “master’s choice breeder” and been set up with the best men on the plantation. It’s touchy material to say the least, but Jones, who recently joined the cast after working as a writer on the show since 2013, explains backstage the importance of using comedy as a means of exorcising very deep pain. She was prepared for angry tweets, but was dismayed that the fury came primarily from the black community—precisely who she imagined her target audience would be.

The intricacies of interpersonal awareness and private sensitivities, collectivism, and exclusion, extend far beyond the reach of the blanket term “political correctness,” which for all its pervasive use of late has become virtually meaningless. “Fighting about what is or isn’t funny is our way of talking about fairness, inclusion, and responsibility.” Scott writes. “Who is allowed to tell a joke, and at whose expense? Who is supposed to laugh at it? Can a man tell a rape joke? Can a woman? Do gay, black, or Jewish comedians—or any others belonging to oppressed, marginalized, or misunderstood social groups, or white ones for that matter—have the exclusive right to make fun of their own kind, or do they need to be careful, too?”

If the reactions to recent unpopular or controversial bits are any indication, the answers to those questions are growing less clear-cut. Audiences don’t seem as bothered, for example, when Amy Schumer jokes about sleeping with a minor as they were with Louis C.K.’s foray into pedophilia. Comedians and audiences alike are learning in real time how much humor is changing year to year. As Live From New York! and Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead both illustrate, decades of social movements and shifting values can add new context to old jokes, change the stakes for current ones, and reinvent the blueprint for future humorists.

At the end of his monologue in May, C.K. took a deep breath, looked out at his audience, and sighed, “Alright, we got through it.” It’s perhaps a fitting statement for the SNL’s 40th season as a whole: The major overhaul of the cast and writing team following the departure of the likes of Seth Meyers, Bill Hader, and Kristin Wiig has left the current players struggling to find their footing, and with no presidential election to provide an immediate anchor of relevance, the show has felt a bit scattered. But even as SNL works to adapt to changes in how humor is produced, shared, and digested, C.K.’s monologue at the very least reminded viewers that Saturday Night Live, and comedy as a whole, is at its most powerful when it gives viewers something to talk (or tweet) about, gasp at, and unravel—even if they’re not all laughing at the same joke.

Most States Elect No Black Prosecutors

It’s no mistake that the most enduring fictional prosecutors are white guys—whether they’re dignified older men like Jack McCoy or hotheaded, handsome younger ones like Dan Kaffee. Art doesn’t always imitate life, but here it does. According to a new survey, an overwhelming portion of the elected officials ultimately responsible for charging criminals, deciding what sentences to seek, and determining whether to allow them to strike plea bargains are white men.

How overwhelming? Here are a few of the numbers, according to a report on elected prosecutors commissioned by the Women Donors Network and conducted by the Center for Technology and Civic Life, a nonpartisan group that grew out of the progressive National Organizing Institute:

95 percent of elected prosecutors are white; 79 percent are white men; three in five states have no black elected prosecutors; 14 states have no elected prosecutors of color at all*; just 1 percent of elected prosecutors are minority women.As The New York Times, which first published the findings, noted, the media has focused intently on the racial composition of police forces over the last year or so, since Michael Brown was shot and killed by an officer in Ferguson, Missouri. That focus makes sense: Each incident of a black man being killed by police under questionable (at best) circumstances seems to be succeeded by another. While there are few good statistics on the number of fatal shootings by American police each year, the absence of black police officers can be seen and measured.

If the issue is how best to reform the justice system overall, however, there’s an argument to be made that prosecutors are far more important. In May, The New Yorker’s Jeffrey Toobin wrote:

In the U.S. legal system prosecutors may wield even more power than cops. Prosecutors decide whether to bring a case or drop charges against a defendant; charge a misdemeanor or a felony; demand a prison sentence or accept probation. Most cases are resolved through plea bargains, where prosecutors, not judges, negotiate whether and for how long a defendant goes to prison. And prosecutors make these judgments almost entirely outside public scrutiny.

It isn’t just a lack of scrutiny—it’s the impossibility of scrutiny. As criminal-justice experts told Matt Ford, prosecutors aren’t required to keep statistics on the many of the most relevant matters, from racial bias in the charging process to how plea bargains are conducted. And even less of this data is currently collected, or reported, than in the recent past.

This ought to be worrying in a democracy: Although trying to assemble a government that perfectly represents each minority population may be a recipe for disaster—ask Lebanon!—the magnitude of the disparity here should startle even jaded observers. At the federal, state, and local levels, African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians hold elective office at rates lower than their percentages of the overall population, but even so, the gap among prosecutors is particularly large. There’s also little question that the U.S. justice system as it exists perpetuates and encourages huge racial gaps, leading to much higher incarceration rates for black men and serious social disparities in housing, education, employment, and beyond.

Related Story

Can the Baltimore Prosecutor Win Her Case?

But just because prosecutorial discretion has a huge impact on the way the system works doesn’t necessarily mean that a more racially representative corps of district attorneys would close the racial gaps in results. (There are also reasons to be concerned about elected prosecutors per se; only three states—Alaska, Connecticut, and New Jersey—have appointed prosecutors.) Police departments that better represent the racial makeup of the population may be desirable in and of themselves, but more diverse police departments don’t seem to produce less police violence against black citizens. Since the problem is not the personal racism of officers but systemic racism, putting more black cops on the beat doesn’t solve it. Is there any reason to believe the case would be different with prosecutors?

A short answer is: surely not on its own. The decision by Baltimore City State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby—a veritable unicorn as a black, female elected prosecutor, according to this report—to charge six police officers in the death of Freddie Gray is one of the more prominent cases of a prosecutor speaking out about racial disparities in the system and taking action to correct them. Another recently elected black prosecutor is Brooklyn District Attorney Ken Thompson. Thompson beat an aging incumbent who was implicated in multiple questionable investigations, and he immediately sought to address racial gaps in enforcement. He has indicted police officers who beat or killed black citizens, and he effectively decriminalized marijuana by refusing to prosecute low-level offenses, which tend to disproportionately fall on blacks (even though whites are actually more likely to use). But there are reform-minded prosecutors of other backgrounds, too. Toobin profiled Milwaukee County DA John Chisholm, who is white but has become obsessed with the racial disparities in his own system—which were invisible even to him until he began to seek data and then solutions to them.

In sum, race doesn’t definitively correlate with careful consideration by prosecutors of how their power can exacerbate or alleviate racial gulfs in criminal justice. The most important factor is an interest and willingness to delve into the data and then respond to it. But given that whites tend to be far blinder to the reality of gaps in the system than blacks do, it seems particularly important that prosecutors become a more diverse bunch.

Saying so is the easy part. Filling more of the posts by election, not by appointment, might help, but it’s hard to convince voters to surrender their ability to select officials, and whites and men (and particularly white men) dominate elected office across the United States right now, although some indicators have improved. Even as the solution seems elusive, the problem is glaring.

For Readers, Writing Is a Process of ‘Emotional Osmosis’

Doug McClean

Doug McClean In 2011—long before his debut, The Sympathizer, was published—Viet Thanh Nguyen was struggling with his book. It wasn’t until he stumbled across The Land at the End of the World, a 1971 novel by Antonio Lobo Antunes, that the tide started to turn. For reasons he didn’t fully understand, daily engagement with the novel helped Nguyen solve his most vexing literary dilemmas: Slow, consistent reading helped him find his narrator’s voice, his descriptive mode, and the perfect first sentence he’d long sought. In our conversation for this series, we discussed the way reading provides creative fuel, and the mysterious, indirect ways one book can help another find its shape.

Related Story

When Writers Put Themselves Into the Story

The Sympathizer is the coerced confession of a political prisoner, writing from the confines of a 3x5 solitary cell. The unnamed narrator looks back on his life as a double agent, betraying his post with the South Vietnamese Army as a spy for the Viet Cong. As the story moves from the Fall of Saigon to the movie sets of Southern California, the novel explores the cultural legacy of a brutal war—and the psychology of a character who will betray someone or something he cares for, no matter where he turns. A front-page review in the The New York Times Book Review said The Sympathizer “fills a void in the literature, giving voice to the previously voiceless while it compels the rest of us to look at the events of 40 years ago in a new light.”

Viet Thanh Nguyen was born in Vietnam and raised in California. The author of the academic book Race and Resistance, he teaches English and American studies at the University of Southern California. He lives in Los Angeles, and spoke to me by phone.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: It was the late spring or summer of 2011, and I was having trouble with my novel. For months, I struggled to write the section that would begin the book. I felt I really needed to grab the reader from the beginning. I was thinking of certain books—like Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man—that immediately established both the narrator’s voice and the narrator’s dilemma. I was looking for a sentence that, once it was written, would drive the rest of the novel completely. But as I worked through various first lines and opening scenarios, nothing seemed quite right.

Then I came across this book review of António Lobo Antunes’ Land at the End of the World. The novel was originally published in the 1970s—this was a new version by Margaret Jull Costa, one of my favorite translators of Spanish and Portuguese literature. The excerpts I read in the review had an incredible effect on me. I have to go out, I thought, and read this entire book.

I bought a copy, and kept it on my desk the entire time that I wrote my novel. For two years, every morning, I’d read a few pages of the book until my own urge to write became so uncontrollable that I finally had to put the book down and start writing myself. Two or three pages at random every morning before writing, until I felt my own creative urge take over.

My interest was partially due to the content of the book: Lobo Antunes was writing semi-autobiographically about his experiences as a medic in the Portuguese army, fighting brutal colonial warfare in Angola. That was happening roughly around the same time as the war with which I was concerned, the Vietnam War. The perspective of his narrator—someone who was bitter and disillusioned with his country and the conflict—was something that led to the direct development of my narrator.

I was looking for a sentence that, once it was written, would drive the rest of the novel completely.But the language of the book was the most important thing to me. It was so dense, so rhythmic and beautiful. The sentences just go on and on in unpredictable ways, often leading from the present into the past all within one sentence. This effect really served the purposes of my book, because the novel takes the form of a written confession. The narrator’s concerns at the time of writing always bring him back into the past—his own personal past, but also the history of his nation, the history of colonization, the history of war, all of which are unescapable to him. There was something incredible about the ways these sentences were constructed, in terms of the languidness of their rhythm, that would engulf me and pull me back into the past of my narrator’s own time.

And then, the images—throughout, the novel is filled with great, indelible pictures. Take this short passage, for instance, from the opening of the book:

I know it may sound idiotic, but, on Sunday mornings, when we used to visit the zoo with my father, the animals seemed more real somehow, the lofty, long-drawn-out solitude of the giraffe resembled that of a glum Gulliver, and from the headstones in the dog cemetery there arose, from time to time, the mournful howls of poodles. The zoo had a whiff about it like the open-air passageways in the Coliseu concert hall, a place full of strange invented birds in cages, ostriches that looked just like spinster gym teachers, waddling penguins like messenger boys with bunions, and cockatoos with their heads on one side like connoisseurs of paintings; the hippopotamus pool exuded the languid sloth of the obese, cobras lay coiled in soft dungy spirals, and the crocodiles seemed reconciled to their Tertiary-age fate as mere lizards on death row.

I love how precise, and how unexpected, these images are. And the way that Lobo Antunes doesn’t just give us one image in these sentences—he gives us several in a row. That’s excessive, I think, for a lot of people. Having one great image in a sentence is often times more than enough. But here he’s giving us a whole sequence: the ostriches look “like spinster gym teachers,” the penguins look “like messenger boys with bunions,” the list goes on and on. There is something in this method about not wanting the reader to move on, wanting the reader to stop, look, and luxuriate in these kinds of images that I personally found seductive.

I think some readers don’t want to be stopped in their tracks—they want to be carried along by the language to whatever destination it wants to take them. But because my book was deeply concerned with how you can’t get away from the past, I wanted that reflected in the way you couldn’t get away from beautiful or dramatic images, either. The way that Lobo Antunes was able to extract these incredible pictures was something I wanted to emulate—something I feel I actually failed at, in writing the book. I couldn’t do what he did. Still, it served as a high marker for me to aim at.

When I say I’m attracted to this passage because of its rhythm and its images, there’s still a logic to these things that is separate from the more rational process of saying, I need to construct my story or my characters in such and such a fashion. The language itself had some kind of impact on me that was more emotional than intellectual. The book acted as a condensed, compact, extremely powerful substance that woke me up to what I needed to do, each day, as a writer. I thought of it as espresso. It wasn’t coffee—I couldn’t drink it all day long. I could only take small doses, and that was enough. With caffeine, how do you quantify what’s happening with that? You just know you need it. The process was mysterious, and it worked.

One day, a line came to me after reading The Land at the End of the World:

I am a spy, a sleeper, a spook, a man of two faces.

It just came to me. And I thought, that’s it. All I have to do is follow this voice for the rest of the novel, however long it takes.

Immediately, that day, I wrote to one of my friends who was going to read the manuscript and said: I found the opening line to the novel! That was true. It enabled me to start writing without hesitation, after that.

One of the challenges of the novel’s prose was: I created a character who is going to be a spy, and a double agent, and was inevitably going to do bad things. I knew in advance what some of those things were, although not all of them. My protagonist does kill people and betray people. These are not things I’ve done—things the majority of people haven’t done—and yet you have to get readers to follow this person, for a very long time. So I felt that the whole book would be dependent on the seductiveness of our narrator’s voice and character.

One of the reasons why I paid so much attention to the narrator’s voice was that he needed an ability to persuade or seduce simply through the way he spoke. I needed him to be able to draw the reader in, and accept that they were going to follow him, regardless of his actions—which might be objectionable in many different ways. His seductiveness—if that’s what it is for some readers—is partly due to his beliefs, his politics, his character, but also a lot to do with how he uses the language.

The book acted as a condensed, compact, extremely powerful substance that woke me up to what I needed to do, each day, as a writer.Another part of the seduction was an effect I wanted: a sense of high dramatic and emotional stakes from the very first page. In an interview, Tim O’Brien said his fiction always begins with a big moral question he wants to answer. It also happens in Invisible Man: We’re told first paragraph, the first page, what the major theme of the book is going to be. This is a tricky thing to do—you don’t want your fiction to come off as didactic, or polemical, right from the very beginning. And yet I wanted my novel’s first paragraph to announce to the reader that this is a narrator who is very intent on meditating on certain important issues. It was difficult to know how to do that in a way that was dramatically interesting as well.

The question he arrives at, I think on the second page, is: What is to be done? That was always a question I encountered in college reading Lenin and other Marxist variants, and it’s something I was never able to adequately answer—it was the question I wanted to wrestle with through the writing of the novel. The book itself, writing the story about this person, and what he encounters, and what he does, was a way of forcing myself to answer that question.

At the same time there’s a big, existential, political/moral question, I also wanted to present the reader with a difficult problem of plot: Put a character in a situation he can’t get out of, and watch what he does. I wanted the book to be entertaining, given its literary constraints, despite the very serious questions and issues the narrator confronts.

Through it all, I had The Land at the End of the World. There’s something very mysterious about my attraction to the book—and that is one of the powerful things about writing. As someone who’s a scholar, I try to rationalize and think about why I make certain kinds of artistic choices. But there’s also the part that’s intuitive and emotional. Whatever happened with this book, it was a decades-long process of osmosis: the product of reading hundreds and hundreds of books and authors, absorbing all their styles on conscious and unconscious levels. Some of them mean more to me than others. There was a short shelf of books that I kept near me of writers whose styles and stories I felt I wanted to try to emulate or take something away from. Then I came across this book—somehow, it seemed to be the work that spoke most intimately to how I saw myself as a writer, and how I saw my narrator as a character. It seemed to be the culmination of all these years of influence and inspiration.

Bringing Broken-Windows Policing to Wall Street

The call came from another trader near midnight one night in ‘95. I assumed it was about a crisis in the financial markets, something bad happening in Asia. No, it was about a strip club. “Dude, turn on the TV news. Giuliani is raiding the Harmony Theater.”

The Harmony Theater was a two-level dive club in lower Manhattan, popular among Wall Streeters because it bent rules. It was a place where almost anything, including drugs and sex, could be bought in the open.

When I turned on the TV I saw a swarm of close to a hundred police, many in riot gear, escorting handcuffed strippers and sad-looking clients into waiting police vans. No traders, or at least none that my friends or I knew, were arrested that night.

The closing of the Harmony Theater was broadcast widely because it was the public launch of the “zero tolerance” policy of Mayor Giuliani and his police commissioner William Bratton, who argued New York City was out of control, not because it was too big, but because it was badly managed.

Zero tolerance was the first big application of “broken windows,” a theory of policing first argued in a 1982 Atlantic article by James Q. Wilson and George Kelling. They suggested that by targeting minor crimes, “fixing broken windows,” police could reduce the sense of disorder that often causes more serious crimes. “One unrepaired broken window is a signal that no one cares, and so breaking more windows costs nothing,” they warned.

Broken windows proposed that disorderly behavior left unchecked, even if it seemed harmless, made cities “vulnerable to criminal invasion.” Its implementation by Giuliani was an attempt to lower crime by fundamentally changing the behavior of New Yorkers and the culture of New York. It would, for the next 20 years, reshape the average New Yorker’s life. Rule breakers, no matter how inconsequential, would be arrested and jailed. Gone, after repeated arrests and considerable fines, was anyone who bent or broke the law (well, anyone in minority and lower-income neighborhoods, that is), no matter how gray or small the offense: The squeegee men, folks littering, anyone with marijuana, graffiti artists, prostitutes, panhandlers, and subway-fare jumpers.

At the same time an opposite policy, launched out of Washington, reshaped Wall Street. While the average New Yorker was being subjected to increased police scrutiny, under the theory that individual liberty can collectively be corrosive, financial firms in Lower Manhattan were being subjected to almost no scrutiny, under the theory that individual liberty, especially when applied to businesses, can be collectively beneficial.

My banker friends and I benefited from both policies. We were ignored during the day by regulators and free at night from squeegee men and muggers.

Wall Street and New York City boomed. The firm I joined in ‘93 was an investment bank with 5,000 employees and $110 billion in investments. Fourteen years later it had grown, through acquisitions and mergers, into a financial conglomerate with more than 200,000 employees and $2.2 trillion in investments.

That growth in the financial sector culminated in the massive financial crisis of 2008, which bankrupt my firm and almost bankrupt the country. Following the crisis politicians were finally forced to deal with the reality that it was Wall Street that was out of control and had too many broken windows.

* * *

In ‘93 I joined a Wall Street that was going out of style, a Wall Street where graying partners were served lunches on fine china at their desks by waiters. I joined a Wall Street that celebrated birthdays with strippers on the trading floor and successes with Cuban cigars.

The old Wall Street, filled with medium-size private investment partnerships, had been molded by the financial regulation following the Great Depression, which set strict limits on who could do what. By ’93 these firms were almost entirely gone, being bought up, merged, and replaced by large public megabanks that followed a wave of banking deregulation in the ’80s.

Partnerships were quirky and often eccentric places (think Trading Places), but had a structure that incentivized financial caution. Employees were required to keep their money in the company, so if the firm failed, everyone failed, resulting in a degree of self-policing.

In this era of complete regulatory permissiveness, Wall Street morphed into floor after floor of traders sitting behind walls of computers, watching numbers flash.The newer megabanks paid employees yearly, and allowed them to mostly do with their money what they wanted, leaving little financial stake in their banks. Size also diminished the sense of community; many firms now had employees well into the hundreds of thousands. For some, the only thing that now linked them to the banks that employed them was the yearly bonus and a few sad cheerleading emails from HR.

The relationship to customers also changed. As the industry expanded the distance between bankers and borrowers increased, hidden behind increasing layers of financial engineering. Borrowers no longer walked into a bank to take out a loan. They walked into a lending company in a strip mall, which then sold their loan to a third party, who then sold it to another middleman, and so on, until it eventually was bought by a Wall Street bank who would then put it in a big pile, slice, dice, tranche, and CDO it, and then finally sell it to distant and often foreign investors. Or, as many did, just keep it as one of the bank’s ever-growing investments.

In this era of complete regulatory permissiveness, Wall Street morphed into floor after floor of traders, like myself, sitting behind walls of computers, watching numbers flash, moving other numbers around spreadsheets, and betting on them all. If the bets worked out, they would get paid millions. If they lost, they only got paid hundreds of thousands. Nobody ever had to give anything back to the bank, or to the customer, no matter how badly they erred.

Wall Street was a huge digital neighborhood, almost completely unpatrolled, and steeped in a culture with a diminished sense of fiduciary responsibility to the firm, the customer, or really anyone. It was, in language Giuliani would understand, an environment filled with broken windows, and conducive to abuse.

* * *

One of the intellectual frameworks of the broken-windows theory was a psychological experiment from 1969 by Philip Zimbardo, in which a car, stripped of any ownership (plates removed, hood up) was placed in a bad neighborhood in the Bronx, and in a good one in Palo Alto. The car in the Bronx was quickly surrounded by residents, stripped, and left denuded except for a steel frame. Twenty-four hours later it became an impromptu jungle gym for kids. The car in Palo Alto was left alone until Zimbardo himself started vandalizing it, then others joined.

Wall Street had become a neighborhood that feasted on loose regulations and rules.The lesson, according to broken windows, was that “the appearance of disorder begets actual disorder—and that any visual cues that a neighborhood lacks social control can make a neighborhood a breeding ground for serious crime,” wrote journalist Daniel Brook in a piece critical of the theory. Put simply, don’t leave a car unattended in the South Bronx.

A similar adage applied to Wall Street: Don’t leave a rule unattended. By 2001 you could walk into any Wall Street bank and give them a new regulation or a rule. The result would be the same. Within a few weeks the rule would be surrounded by a scrum of lawyers and traders, stripped of any real meaning, denuded of all except the most absurdly benign interpretation, and the remaining flimsy frame used by traders as an impromptu platform for making money.

Wall Street had become a neighborhood that feasted on loose regulations and rules. It developed new products to evade the letter of the law. Derivatives, complex financial products used to “transform cash flows,” exploded, becoming a tool to shift money away from regulators or taxes. They were used to move money among countries, between long and short capital gains, switch it from debt into equity, interest into dividends.

By 2001 housing was the perfect target for Wall Street: a huge market that was a tangle of rules and regulations, of quasi-guaranteed government agencies, and customers desperate to borrow.

Wall Street went to work bending rules, splitting hairs, exploiting loopholes, lobbying politicians, and building corrupt relationships, hiding all of it behind a layer of complexity. By 2007 Wall Street and the housing market were enmeshed, and banks overloaded with overvalued assets tied to an overvalued housing market, much of it hidden from regulators by derivatives. When the housing market collapsed, Wall Street collapsed even quicker, wiping out profits from the prior decade in a matter of months. The rest of the U.S. was dragged down into a deep recession that it is yet to fully recover from.

* * *

In the aftermath of the crisis, an outraged public demanded things. Angry speeches were given, congressional hearings held, and fines close to $100 billion levied for the most extreme and transparent cases of fraudulent lending practices.

Legislation to reform banking practices and the mortgage market was also passed, mostly notably the Dodd-Frank Act. It was a well-intentioned attempt to address the fundamental problems that contributed to the financial crisis. But Dodd-Frank is itself a huge set of complex rules, and played into the hands of Wall Street.

It was like building a sprawling glass house in a neighborhood filled with broken windows. Since its passing in 2010, regulators have watched as the shiny new bill has been surrounded by the financial industries lawyers, lobbyists, and sympathetic politicians, and much of it either amended, reinterpreted, or whole parts rewritten to favor banks.

Frustrated, regulators have started to shift their focus, realizing that maybe the only way to regulate someone who thrives on ducking regulations is to bring something like broken-windows policing to Wall Street in hopes of changing its culture.

What is the financial equivalent of rounding up the squeegee men, graffiti artists, and those smoking joints in front of the police station? It means going after the easy targets, the transparent businesses where the abuses were well documented.

Doing so has resulted in a bevy of investigations and scandals named after acronyms: LIBOR, FXfix, and ISDAfix. Despite the names, all are routine and boring parts of banking. In the first two cases wrongdoing was clear, admitted to, and massive fines of close to 50 billion were levied against the major banks. The third case is still in its infancy.

None of these practices contributed directly to the financial crisis, or were really that wrong, by Wall Street’s abusive standards. Rather they were just games being played at the edges by bankers used to bending rules. The cost and direct harm of these scandals are also hard to figure out, although it probably fell mostly on other bankers and financial institutions, not the grandmothers and farmers politicians like to worry about.

The investigations did further expose a banking culture so rife with rot that cheating was normal. As one trader from the FXfix case was found saying, “If you ain’t cheating, you ain’t trying.”

And that is what regulators care about, and why they are now following the playbook from broken windows. They want to change the culture of permissiveness and to finally tend to long untended behavior, in the hope of affecting serious fundamental change. From the 1982 Atlantic article,

This wish to “decriminalize” disreputable behavior that “harms no one” is, we think, a mistake. Arresting a single drunk or a single vagrant who has harmed no identifiable person seems unjust, and in a sense it is.

But failing to do anything about a score of drunks or a hundred vagrants may destroy an entire community. A particular rule that seems to make sense in the individual case makes no sense when it is made a universal rule and applied to all cases. It makes no sense because it fails to take into account the connection between one broken window left untended and a thousand broken windows.

* * *

It is unclear if broken windows for Wall Street will work. Penalizing the corrupt businesses you can get your hands on might slow down the more opaque and dangerous businesses you can’t. It might make them less abusive of rules and regulations. It might help to forge a renewed fiduciary responsibility of bankers to customers, clients, and their own firms. Or it might only provide incentive to Wall Street to bury its crimes further, shielding them behind more complexity.

It might also be just scapegoating, an exercise in making the public feel like something is being done while leaving the more damaging structural issues unchanged. Employee compensation is still incentivized toward short-term and capricious risk taking and the megabanks are still too big to fail.

Twenty years after the New York City police force started applying broken windows to address street crime, the benefits are being questioned. The costs, in human terms, have been huge, with record numbers of citizens, mostly minorities, incarcerated, and untold others denied basic constitutional rights.

If a broken-windows approach to Wall Street doesn’t work, if it doesn’t change the culture, decrease the fraud, and doesn’t decrease the risk and consequences of future financial crises, the cost in human terms will have been close to nothing.

So far the only consequences for Wall Street bankers has been fines levied at their companies. The number of bankers whose personal lives have been disrupted is tiny.

More people will probably have served time from that first Giuliani raid on the Harmony Theater in ‘94 than will serve time for all the acronym scandals. That is not a very high threshold though, because nobody has yet to serve time for the acronym scandals. Just like almost nobody has served time for any part in the financial crisis.

And that is the biggest difference in all of this: Bankers get fines. Everyone else goes to jail.

The Clinton Campaign Is Afraid of Bernie Sanders

Obscured by the recent avalanche of momentous news is this intriguing development from the campaign trail: The Hillary Clinton campaign now considers Bernie Sanders threatening enough to attack. Fresh off news that Sanders is now virtually tied with Hillary in New Hampshire, Claire McCaskill went on Morning Joe on June 25 to declare that “the media is giving Bernie a pass … they’re not giving the same scrutiny to Bernie that they’re certainly giving to Hillary.”

The irony here is thick. In 2006, McCaskill said on Meet the Press that while Bill Clinton was a great president, “I don’t want my daughter near him.” Upon hearing the news, according to John Heilemann and Mark Halperin’s book Game Change, Hillary exclaimed, “Fuck her,” and cancelled a fundraiser for the Missouri senator. McCaskill later apologized to Bill Clinton, and was wooed intensely by Hillary during the 2008 primaries. But she infuriated the Clintons again by endorsing Barack Obama. In their book HRC, Aimee Parnes and Jonathan Allen write that, “‘Hate’ is too weak a word to describe the feelings that Hillary’s core loyalists still have for McCaskill.”

McCaskill, in other words, is a great surrogate: someone eager enough to regain the Clintons’ affection that she’ll not only praise Hillary, but also slam their opponents. On Morning Joe, she had two talking points. First, journalists are giving Sanders a pass. Second, Sanders is a socialist, and thus can’t win. Asked about Sanders’ large crowds, McCaskill compared him to Ron Paul and Pat Buchanan, other candidates who sparked enthusiasm among their supporters but couldn’t win a general election because of their “extreme message.”

Related Story

Don't Underestimate Bernie Sanders]

On point number one, McCaskill is undeniably correct: Media coverage of Sanders has been fawning, partly because many journalists harbor sympathy for his anti-corporate message but mostly because they’re desperate for a contested primary. Given Sanders’s strong poll numbers, the media would eventually have gotten around to tearing down the man they pumped up. But Team Clinton clearly wants to accelerate this process before Sanders gets any more momentum.

More intriguing is point number two. Sanders probably would be a problematic general-election candidate. But the liberals flocking to his side don’t much care. Nor are the Clintonites likely to scare off many liberals by reminding them that Sanders is a socialist. Most of them already know. And far from hiding it, Sanders is quite effective when challenged on this point. Right after he jumped in the race, George Stephanopoulos gave Sanders exactly the treatment McCaskill is calling for now. First, he reminded Sanders he was a socialist. Then, when Sanders pointed to Scandinavia as his socialist model, Stephanopoulos snarked that, “I can hear the Republican attack ad right now: He wants America to be look more like Scandinavia.” But Sanders was not cowed. “That’s right. That’s right,” he replied. “And what’s wrong with that? What’s wrong when you have more income and wealth equality? What’s wrong when they have a stronger middle class in many ways than we do?” It was the kind of performance more likely to leave liberals inspired than alienated.

McCaskill grew even less effective when Mark Halperin did something TV interviewers too rarely do: He demanded substance. Give “three specific positions” of Sanders that “are too far left,” he insisted. “I am not here to be critical of my colleague Senator Sanders,” McCaskill responded, absurdly. But Halperin caught her, noting that, “With all due respect, you already were: You said he was socialist and not electable.”

Then things got interesting. The specifics McCaskill offered were that Sanders “would like to see Medicare for all in this country, have everybody have a government-insurance policy,” that “he would like to see expansion of entitlement,” and that “he is someone who is frankly against trade.”

If Hillary actually goes after Sanders on these specifics, the Democratic race will get very interesting very fast. A debate about Obamacare versus single-payer health insurance, about expanding Social Security versus restraining its growth, and about the merits of free trade would be fascinating. But I doubt it’s a debate Hillary wants to have. She is, after all, running a campaign based on generating enthusiasm among the party’s liberal core. By taking bold, left-leaning positions on immigration, criminal justice, and campaign-finance reform, she’s trying (and so far succeeding) to erase her reputation from 2008 as a timid triangulator unwilling to offer big change. Yet the more Hillary emphasizes her opposition to single-payer health care, her opposition to expanding Social Security, and her support for free trade, the more she undermines her own strategy. By taking on Sanders on these issues, Hillary also implicitly takes on Elizabeth Warren, who has made expanding Social Security and opposing the Trans-Pacific Partnership two of her recent crusades.

The irony is that in 2008, when Hillary was trying to distinguish herself from her party’s left base in order to appeal to general-election moderates, an opponent like Bernie Sanders might have seemed like a blessing. In 2016, by contrast, when Hillary is running to the left, attacking him as too far left is dangerous.

No wonder McCaskill wants journalists to bury the curmudgeonly Vermonter. The Hillary campaign knows how tricky it will be to bury him themselves.

July 6, 2015

‘BBHMM’: Rihanna's New Video Does Exactly What It's Supposed To

Of all the scandalized reactions to Rihanna’s music video for “Bitch Better Have My Money,” my favorite comes, as is not surprising for this sort of thing, from the Daily Mail. Labelling herself in the headline as a “concerned parent” (a term to transport one to the days of Tipper Gore’s crusade against lyrics if there ever was one), Sarah Vine opens her column by talking at length about how so very, very reluctant she was to watch Rihanna’s new clip. Then she basically goes frame-by-frame through the video, recounting her horror at what unfolds. “By the time it had finished, I wondered whether I ought not to report [Rihanna] to the police,” Vine writes. “Charges: pornography, incitement to violence, racial hatred.”

Related Story

Rihanna, Queen of Frustrating Marketing

Savor the outrage, luxuriate in the shock—these are as much the intended pleasures of the “Bitch Better Have My Money” video as the insane images onscreen are. Rihanna is looking to prosper through controversy in the same way that her idol Madonna has done so many times via the medium of the music video. “Bitch Better Have My Money” might be the most successfully provocative output from a major star in years, a fact it achieves in large part by hewing to the tropes of mainstream entertainment.

In the seven-minute clip, the pop star kidnaps and torments the wife of an accountant who bilked her, dismembers the accountant, and then lounges, naked and covered in blood, in a box of money. The staging and editing is striking, comic book-like, almost whimsical—I felt sickened as I watched, but I also giggled as Rihanna, making a phone call, casually stepped aside to avoid the trophy wife swinging from the rafters like a pendulum.

The song and the video are reportedly inspired by a real-life case of Rihanna’s accountant allegedly cheating her out of millions of dollars, and here the swindler is played by Mads Mikkelsen, who also stars as the titular cannibal on the NBC drama Hannibal. It’s a small bit of casting that offers a key to the entire message. If Rihanna’s display of violence is any more shocking, any more objectionable, than the displays of violence seen on Thursday night TV, or in Rated-R films, or in any number of previous carnage-laden music videos, it’s the objector’s burden to say, exactly, why.

The most common response: By treating the kidnapping of a woman as a badass, comical activity, Rihanna feeds the idea of females as objects to be used and abused for material gain and an audience’s enjoyment. The middle-aged male man who ends up sliced to bits gets almost no screen time compared to the model Rachel Roberts, who’s stripped naked, strung up like a piece of meat, conked on the head with a bottle, and nearly drowned. But each humiliation, in the end, is just a particularly vivid contribution to an old entertainment tradition. “There was little fuss over the raped and murdered bank teller in From Dusk Till Dawn, the brutalized prostitutes in Frank Miller’s Sin City, or the bikini clad college girls snorting coke and shooting down pimps in Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers, all of which are hailed as ‘cult classics,’” writes Roisin O’Connor at The Independent in a defense of the video.

“Bitch Better Have My Money” is that most American of genre—revenge fantasy, which includes about 100 percent of Hollywood’s action output. The “fantasy” component of this particular version is heightened by the total caricature of the victims and the fur-bikini swagger of the heroes. In films from Taken to most all of Quentin Tarantino’s output, defenseless women—raped wives, kidnapped daughters—are habitually the means by which righteous-and-entertaining violence is justified. So when Rihanna, a woman, takes revenge on a man by snatching his woman, it’s not so much a flipping of the script as a total rewriting of it. We live in a world where women are victims? Fine, Rihanna says; it’s in that world that she’s got to get her money back.

We live in a world where women are victims? Fine, Rihanna says; it’s in that world that she’s got to get her money back.There’s a racial component here, too. It’s likely no accident that Rihanna’s riding with a multicultural female posse and that Roberts’s character inhabits one of the ultimate stereotypes of whiteness—the banker’s prissy wife. Rihanna was ripped off by a caucasian financier who was supposed to help her; she’s not the first person of color in that position, and she’s probably not the first to fantasize about doing something drastic about it. Why wouldn’t she make art about it?

Yes, Rihanna has lots of young fans who look up to her; yes, fantasy or not, airing a video like this constitutes bad behavior. But Rihanna’s entire brand is predicated on the fact that she’s not afraid to be bad. Being bad gets people to talk about her. Being sexy and violent does the same. She did not make this video to make the world a better place; she did it to project an image and get paid. Judging by the response, she’s succeeded on both counts.

An American Victory at the World’s Game

In the end, most of the game itself felt like an afterthought: With America’s breakout player Carli Lloyd scoring a hat-trick in the first sixteen minutes, the nation’s victory in the Women’s World Cup final seemed assured. The U.S. team’s barnstorming 5-2 victory over Japan was sweet revenge for its loss to the same team in the 2011 final on penalties, as well as a showcase for Lloyd’s surgical scoring ability (from literally everywhere on the field). But just as admirably, the champions never lacked for dignity and grace, playing and celebrating with assured sportsmanship even as the Japanese team seemed to crumble under the early deficit.

Related Story

The Grass Ceiling: How to Tackle Inequality in Women's Soccer

The statesmanlike authority of the U.S. team perhaps underlines what has felt so unique about the 2015 Women’s World Cup, which attracted record viewing figures while inspiring hope that women’s soccer can endure domestically as a popular professional sport after the trophy-winning hoopla dies down. Carli Lloyd, who was named the player of the tournament and whose hat-trick was the first ever in a Women’s World Cup final, plays for the Houston Dash in the regular season, a team in the fledgling National Women’s Soccer League where salaries reportedly range from $6,800 a year to a maximum of $37,800. At 32 years old, she’s spent her whole career under similar circumstances, rising to captain her national team and help boost the sport’s popularity nationwide. She, like her teammates, was truly on the field for the love of the game.

This isn’t to discount the effort of other athletes who earn fair compensation from their own professional sports leagues, which are far wealthier from multi-year TV deals, hefty sponsorships, and the like. Even while soccer’s governing body, FIFA, reliably hits the headlines for the wrong reasons, the World Cup has always held a special appeal: Here are players taking the field for their country, not their paychecks. It’s worth noting that FIFA gives out $2 million in prize money to the winning team at the Women’s World Cup—but that number pales in comparison to the $35 million that goes to the winning men’s team, and the $27 million the organization spent making the film United Passions, a much-derided piece of propaganda about the organization’s history.

This is America’s first World Cup trophy since 1999, when the tournament was still in its infancy, and the star player Mia Hamm had no professional league to play for in the United States (she would help found the first two years later). This year, Lloyd cemented her status as the 2015 World Cup’s breakout star with those three goals, making the near-impossible look very easy, especially the effort that sealed her hat-trick and gave the U.S. a commanding 4-0 lead sixteen minutes in. Picking up the ball around the halfway line, she noticed the Japanese goalie had come off of her line and launched a shot; Ayumi Kaihori did what she could to get back, but it was too late. If the U.S. lead had felt dominant before, it was now almost insurmountable.

That early flurry of goals made for an otherwise perfunctory game; even the Japanese team scoring twice and bringing the score to 4-2 couldn’t raise a scare, and Tobin Heath sealed the game with the U.S.’s fifth goal in the 54th minute. This flurry of early scoring came in a tournament where the Americans had struggled to score early; indeed, that was what made the semi-final against Germany the most nail-biting match of the tournament. But one player opened the scoring there, in what really functioned as the de facto final in terms of pure skill on display: Carli Lloyd.

Abby Wambach, for so long the figurehead of the American women’s team, finally captured the trophy that had eluded her since 2001.Lloyd wasn’t the only hero of the day. Goalkeeper Hope Solo, for all her personal struggles, capped her sterling work throughout the tournament with the Golden Glove award; Abby Wambach, for so long the figurehead of the American women’s team and now entering her twilight years, finally captured the trophy that had eluded her since she was first called up to the team in 2001. Her victory sealed, she ran to the stands to embrace her wife Sarah, which will stand as an indelible image of progress in sport, just like so much else.

But there’s still more progress to come. 2015 marks the first women’s tournament to feature 24 teams, and hopefully it can eventually expand to the 32 nations that play in the men’s World Cup every four years. The controversy over the artificial turf the women played on, a much shoddier and more dangerous surface than the natural grass featured in men’s soccer, helped underline the gender disparity that still exists, one that will hopefully be addressed by the time the 2019 tournament takes place in France. But with all that said, more than 53,000 fans watched Sunday night’s final unfold in Vancouver, while tens of millions more tuned in on Fox, proving that an audience for women’s soccer is very much alive for the sport in the future.

What Schools Will Do to Keep Students on Track

Desiree Cintron’s name used to come up a lot during “kid talk,” a weekly meeting at Chicago’s North-Grand High School at which teachers mull over a short list of freshmen in trouble.

No shock there, says Desiree now, nearly three years later.

“I was gangbanging and fighting a lot,” she says, describing her first few months of high school. “I didn’t care about school. No one cared, so I didn’t care.”

Had Desiree continued to fail in her freshman year, she would have dropped out. She is sure of that. It was only because of a strong program of academic and social supports put together by her teachers that she stuck it out. Desiree pulled up a failing grade and several Ds. She gave up gangbanging and later started playing softball. She connected with a school determined to connect with her.

Today, although Desiree still is not a strong student at North-Grand, which serves mostly low-income Latino kids in Chicago’s West Humboldt Park neighborhood, she has the grades to make graduation within reach.

A student who passes ninth grade is almost four times more likely to graduate than one who doesn’t.At the core of Desiree’s success story is a strikingly simple tactic that research says really works: Get a high-school student through freshman year and the odds skyrocket that he or she will graduate. Chicago was a pioneer of the strategy, first applying it in 2007, and has the numbers that would seem to prove its worth, even after accounting for inflation by principals possibly gaming the system. The potential is huge for school systems across the nation, especially those in urban areas plagued by low graduation rates.

Between 2007 and 2013, the number of freshmen in the Chicago Public Schools making it to the 10th grade grew by 7,000 students. The school system’s four-year graduation rate also jumped, from 49 percent in 2007 to 68 percent in 2014. Graduation rates are up across the country, but Chicago’s double-digit growth stands out.

This is astounding progress, especially in a school system where the vast majority of students come from low-income families and where a budget deficit—which Mayor Rahm Emanuel recently announced is forcing him to make cuts worth $200 million—has undermined programming and teacher satisfaction. And the progress was achieved without a shiny new program or a drastic educational overhaul: The schools simply stepped up the most basic interventions to help freshmen avoid failure, such as tightly monitoring grades and offering more tutoring sessions. Between 2007, when the school system began to monitor the data, and 2014, freshmen pass rates leaped from 57 percent to 84 percent, with the biggest gains for black and Latino boys and students in “dropout factories”—schools few other academic reforms have helped.

“I’ve been arguing against silver bullets my whole career—but this is one,” says the University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research’s Melissa Roderick, who has led research into the role of freshmen pass rates. “Failure is horrible; it’s overwhelming for every kind of kid. But a kid who passes is off to a good start in high school. And it turns out, if you keep children in front of teachers they actually learn.”

* * *

More than a decade ago, Roderick’s colleagues at the University of Chicago discovered that passing the ninth grade—earning at least five credits and no more than one semester F in a core class—is a better predictor that a student will graduate than are his or her previous test scores, family income, or race. A student who passes ninth grade is almost four times more likely to graduate than one who doesn’t.

Schools like North-Grand that have successfully improved freshman pass rates employed variations of the same set of interventions. They adopted data systems to track freshmen progress, carefully picked the right teachers for ninth-graders, created weekly grade checks, provided mentors and tutoring sessions, stepped up truancy monitoring, set aside one day a week for students to make up work, and started freshman seminars that teach kids to “do high school.” Some schools also switched to forms of grading that are designed to be more fair and modern—less emphasis on turning in homework on time and more emphasis on actually learning—but have been accused of inflating GPAs.

Desiree Cintron, now a junior at Chicago’s North-Grand High School, says she would’ve dropped out of high school had she not made it through her freshman year. (Kate Grossman / The Atlantic)

Desiree Cintron, now a junior at Chicago’s North-Grand High School, says she would’ve dropped out of high school had she not made it through her freshman year. (Kate Grossman / The Atlantic) These approaches are consistent with a national effort in urban education to move from a punitive, sink-or-swim model toward one built on second chances. It reflects an understanding that moving up from the strictures of elementary school to the freedoms of high school, at an age when hormones are raging, can be awfully hard. Kids of all academic backgrounds—A students and D students—cut class more and get worse grades when they hit ninth grade.

“Ultimately, what you get is a different understanding of the purpose of schools, that it’s not about weeding bad kids from good ones,” says Sarah Duncan, who co-directs the University of Chicago-affiliated Network for College Success. Launched to help educators put research into practice, the network coaches staff at 17 Chicago schools, including North-Grand—most of which have seen major boosts in freshmen pass rates.

But in Chicago, other schools are seeing improvement, too. And that has raised questions. Once Chicago began pushing for higher freshmen pass rates, teachers started to complain that school administrators were cheating by doctoring attendance records and inflating grades—particularly at the schools that had switched to the new grading strategies, which many consider too lenient.

“It’s like Campbell’s law—the more you depend on a measure, the more it’s subjected to corruption,” says Jackson Potter, a member of the Chicago Teachers Union leadership team.

“It’s like Campbell’s law—the more you depend on a measure, the more it’s subjected to corruption.”Staff in a few schools tell of principals putting pressure on teachers to pass all students, of kids who cut more classes than they attend but still pass; the idea of giving kids an extra chance is grossly perverted, they say, pointing to fudged attendance records and the lenient grading models. One teacher at Washington High School on Chicago’s Southeast Side, for example, says freshmen often get passed along in ninth grade and begin tenth grade without basic skills, advancing in a similar fashion all the way to graduation.

Attendance is crucial because truant kids aren’t learning—or improving graduation and freshman pass rates. Any school with a rising on-track rate but a static attendance rate is automatically suspect. CPS also gives schools higher ratings for good attendance, and the state funds CPS in part on the basis of attendance.

At Manley High School on Chicago’s West Side, students frequently skip first and last periods, according to attendance records provided by three teachers. The records show that administrators frequently change absences marked by teachers as “unexcused” to “school function,” a notation that once covered field trips or assemblies but now appears to cover almost any reason for being out of class. This change marks the child as present, boosting attendance data for the student and the school.

This year, 19 percent of Manley students supposedly went to more than 100 school functions, missing more than 100 classes each; 64 percent of students racked up more than 50 functions. Among the most common reasons administrators cited for the changes from “absent” to “school function” was to account for students supposedly in “attendance recovery detention” rather than class even though the school, according to the teachers, doesn’t have detention.

Administrators, they say, are trying to blunt a huge problem with cuts: Even with the school-function changes, nearly 60 percent of the school’s students had unexcused absences from more than 100 classes each. “It’s all data-driven and whatever they can do—lie, fudge, and steal—they’ll do to get the numbers up,” says Marilyn Parker, a Manley teacher. The two other teachers requested anonymity because they feared retaliation. The school system’s inspector general is investigating Manley. Citing that, the school system would not allow the principal to be interviewed.

The inspector general also is investigating Juarez High School, where teachers similarly allege that attendance data is being tampered. One student, for example, accumulated unexcused absences marks in 381 separate classes, amounting to 54 full school days, records provided by a teacher for the 2012-13 school year show. The student’s final transcript showed just 21 unexcused absence days. Juarez has after-school tutoring, where attendance from one cut class each day can be made up, per CPS policy, the principal said, flatly denying any attendance rigging. Citing the investigation, CPS would not answer detailed questions about student records.

The IG also documented problems at Washington High two years ago. Tardy kids were sent to detention rather than to first period and were then labeled at a school function. The IG cited “hundreds of thousands” of lost instructional minutes, and the practice has ended. But teachers say a new scheme appeared this year. A minority of students racked up abnormally high numbers of school functions, as many as 90.

The school’s principal, Kevin Gallick, also denies the accusations. “We don’t play games with this stuff because there is too much at stake,” he said, pointing to growing ACT scores and college-acceptance rate at his mostly low-income, Latino school. “Look at the big numbers we’re putting up. Why would we want to damage our school’s reputation when we’ve done such good work?”

“It’s all data-driven and whatever they can do—lie, fudge, and steal—they’ll do to get the numbers up.”One reason teachers are particularly concerned about the possibility of fudged attendance data is that they are evaluated in part by student test-score growth over the year. When these kids fail, which those who are frequently truant often do, it unfairly reflects poorly on teachers. Teachers also accuse the school system of cheapening the high-school diploma and graduating kids who aren’t prepared for college or work life.

Still, a UChicago Consortium study last year of 20 schools that had early success improving their on-track rates did not find widespread gaming by principals eager to make their schools look good. The average ACT score remained very close to what it had been before the on-track focus began at the 20 schools, and during the same time period, it went up by half a point for CPS as a whole. If freshmen were being passed along, the overall junior year ACT scores likely would have dropped. More broadly, it found the most compelling proof yet of a direct link between improved freshmen pass rates and dramatically improved graduation rates. And a more comprehensive study of all schools, now near completion, will show that improved freshmen pass rates played a role in pushing graduation rates up districtwide, the consortium’s director, Elaine Allensworth, says.

Nonetheless, at least one Chicago media outlet recently questioned the integrity of Chicago’s graduation rate. The local National Public Radio affiliate, in partnership with Chicago’s Better Government Association, found that dropouts were being mislabeled at some schools to make it seem like a higher percentage of students were graduating. The impact wouldn’t be enough to undercut the larger narrative—graduation rates have increased by double digits—but the revelations bolster anecdotal evidence that some number rigging is going on.

Comparison of Freshmen Pass Rates and Five-Year Graduation Rates in Chicago Public Schools

The University of Chicago

The University of Chicago Meanwhile, many teachers across Chicago fear that the new grading policies—with names like “standards-based grading” and “no zero” grading—make passing too easy. Some schools go too far, they say, by declining to penalize students for late work and prohibiting teachers from giving grades below 50. Traditionally, a student who didn’t hand in work would get a zero.

A single zero can disproportionately pull down a student’s average, but teachers at some schools say the new grading tactics come with a destructive practical effect. At Manley, some students refuse to work until the very end of the quarter—in some cases just cutting classes—when teachers must give them a make-up packet for any classes they attended but for which they failed to submit assignments, or those classes marked as a school function. If the student completes most of the work, they are likely to pass.

“They’re letting kids manipulate the system,” says Manny Bermudez, a Juarez teacher who last year publicly confronted his school’s administration about attendance and grading practices and was later fired, after which he sued and was ultimately reinstated.

The school system denies any wrongdoing, and Juarez’s principal, Juan Carlos Ocon, says Bermudez has a “fundamental misunderstanding” of the grading system. “Other teachers will tell you the rigor has increased,” Ocon says. “Most of our teachers support what we’re doing because they think it enhances learning.”

Even ardent defenders of CPS’ on-track results admit some gaming likely goes on, but they emphasize that it’s not widespread and that there’s a greater good here: It’s far better for a student, especially a low-income one, to graduate than to drop out.

* * *

At North-Grand, the percentage of students on track to graduate has risen so much since 2012 that it has a new mantra: “Bs or better,” the latest push by the school’s leaders that relies on student data to design customized interventions. Simply getting a passing grade is no longer good enough.

“If I miss an assignment, I get a paper telling me what I need to make up—they really want us to succeed,” Ronnita Grimes said during a freshman seminar this spring. Ronnita this year completed missed assignments to convert two Cs into two Bs.

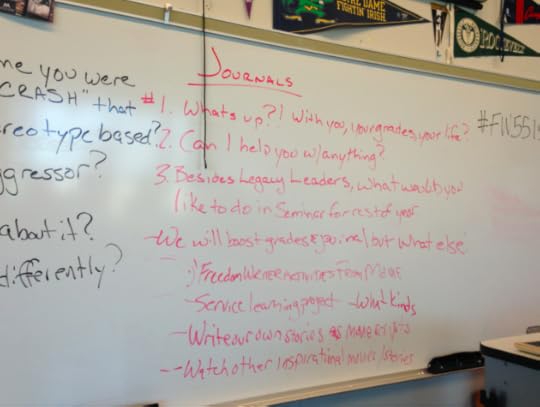

The seminar is central to North-Grand’s freshmen on-track program, focusing on life lessons in perseverance and team-building, providing them time to make up missed assignments, and offering impromptu group and individual counseling.

“Some kids probably got away with something, I don’t doubt it … [but] if kids get away with something in adolescence and still go on to graduate high school … that’s a good thing.”Desiree, the student who almost failed her freshman year, says two staffers, including teacher Brett Murphy, who designed the freshman seminar, changed her life. “Mr. Murphy opened up to me so I opened up to him,” Desiree says. “It felt good to know, wow, he’s actually here for me.”

Each week in the seminar, Murphy’s students write in a “diary that writes back”—Murphy responds to the entries—sharing whatever is going on, from mundane boy trouble to family abuse or gunshots in the neighborhood. “Hopefully every bit they can shed allows them to focus,” says Murphy, who finds out where students are struggling, lets them do make-up work in his class, and helps them negotiate with other teachers. But Murphy and a fellow freshman seminar teacher aren’t flying solo, and that’s crucial to the school’s improved ninth grade pass rate and their “Bs or better” strategy.

An outside group comes in each week to teach leadership skills to students, while a team of carefully selected freshman teachers, an attendance clerk, a counselor, and administrators convene weekly for “kid talk.” For kids in deep trouble—there are plenty in a neighborhood marked by violence and poverty—teachers can turn to the school’s “care team,” which finds ways to get kids more intensive help. The heart of the work is helping students make up assignments they blew off or didn’t understand, but extensions aren’t endless, and late work is marked down in many cases.

“We teach them they have control over how well they do in school, even if they’re struggling,” says Phillip Cantor, a science teacher. “When a kid’s grade changes, they say ‘it feels good.’ Then I say ‘we can do this again.’”

Tough love long reigned in many urban districts. But kids simply dropped out, and the no-excuses approach is falling out of vogue. “Teachers will say an F will give them a kick in pants,” says Lisa Courtney, a North-Grand teacher who helped design the freshman seminar. “We have to get away from the idea that F is a motivator. It’s a de-motivator.”

The white board in Brett Murphy's freshman seminar class one day this spring tells students what he wants to hear from them when they write in their diaries. (Kate Grossman / The Atlantic)