Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 403

June 28, 2015

Ramadan Is Not a Time for Bloodshed

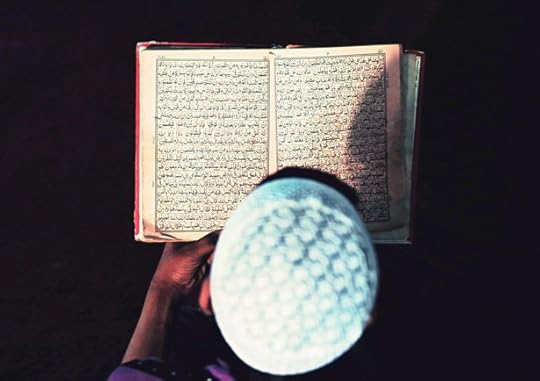

For most Muslims around the world, the month of Ramadan marks a yearly renewal, a time to turn inward in spiritual reflection, upward to God in worship, and outward toward other human beings in acts of charity. It is a time when many Muslims who do not offer the five required daily prayers or have much to do with religion for the rest of the year still refrain from food, drink, and sex during the daylight hours of an entire lunar month for the sake of God. Among the five pillars of Islam it is the fast of Ramadan, not the daily prayers, that is the most universally observed Muslim practice worldwide, behind only belief in God and the Prophet Muhammad. People fill mosques at night to offer extra prayers in congregation, and some even spend part or all of the last 10 days of Ramadan in a state of spiritual seclusion following the example of the Prophet. It is a month when many Muslims pay their yearly required alms (zakat) and when generosity reaches its peak in Muslim societies, especially through giving free break-fast meals (iftar) to the poor.

In a way, Ramadan combines the spirit of Christmas with the inwardness of the Easter season. Indeed, Muslims consider Ramadan to be the month that the Word of God (the Quran) first descended into the world through the revelation to Muhammad, as Christmas is the time when the Word of God (Jesus) came into the world through the virgin birth.

Related Story

The Ramadan fast is marked by its anonymity and intimacy with God. The Prophet said that God says, “Every good deed is [rewarded] 10 times its like, up to 700 times, except for fasting. It is for Me, and I will reward it.” No one but God can see you fast. The Prophet said that especially while fasting one should not shout or return insults, but respond to an abuser by saying, “I am fasting. I am fasting.”

Just a day without food and one realizes how fragile the body is, how it becomes harder not only to move but even to think! It is a bodily experience of emptiness and poverty that Sufi Muslims say should be the state of the soul before God at all times. Muslims are reminded of the dependence of human beings upon that which is other than themselves for their happiness, and through the daily Ramadan ritual they practice breaking free of even their wholesome and licit desires in order to turn inward. It is an exercise of the spiritual heart overcoming the ego. The Prophet directed Muslims to the inner nature of the fast by warning, “Many people get nothing from the fast but hunger and thirst.”

* * *

In contrast, at the beginning of the current month of Ramadan, an ISIS spokesman said, “Aspire to battle in this noble month … make Ramadan a month of disasters for the unbelievers.” It was a message that mangled lofty teachings about the holy month drawn from sayings of the Prophet and combined them with warmongering rhetoric whose spirit was summed up in the spokesman’s declaration, “No acts of worship are equal to [military] jihad.” On Friday, the second Friday of Ramadan and just days after the release of the statement, vicious attacks struck three different countries. ISIS has claimed responsibility for the atrocities in Kuwait and Tunisia, but not, as yet, France. The group’s brutality has also escalated in Syria, where at least 145 civilians were reportedly killed in the town of Kobani.

It is tempting to view ISIS’s Ramadan statement as a manifestation of dueling (and tiresome) narratives between a fringe and a mainstream—“ISIS is Islamic!”, “No, it’s not!”—but in reality there is something deeper going on.

The idea of Ramadan as a season of cruelty and aggression is not just incorrect but unthinkable. So how does it become thinkable?A great danger in all religions is the drift from the inward to the outward, resulting in a focus on the shell at the expense of the kernel. When this happens, rituals like fasting are seen less as interiorizing and illuminating ways of approaching God, and more as measures of conformity and participation in a greater human project. For those people who are usually but misleadingly called fundamentalists (even the most peaceful kind), the pursuits of truth, law, contemplation, and social life are often mashed together into a mechanistic fervor in the service of a supreme goal: the fulfillment of an ideological blueprint. These people fuse and confuse the spiritual and the material, and measure all goodness in terms of adherence to a pre-ordained program and vision of what society (and perhaps the entire world) is supposed to look like.

Without inner meaning and truth, spirituality is reduced inexorably to some social, communal, or legal obligation. Instead of being about the sacred, religion is about “the community” or “the glory of [insert name of group].” For different reasons, modern secular systems of thought tend to see religion as being entirely reducible to (and not only comprising) matters of class, gender, race, and the like. But what about the truth as such? What about the sacred?

When all that is left of religion is its shell, something more sinister will inevitably take the place of the kernel. Rituals, when they cease to nourish the soul and allow participation in a transcendent truth, can become mechanisms of control: you perform the actions and are punished if you do not, and prayer and fasting become gears and levers in a machine designed to build a perfect world. This is the Ramadan of ISIS, where boys are reportedly hung by their wrists for eating during the fast. Only with such a vision of things does it become plausible to say that no act of worship is superior to war, and that a month of fasting and prayer is a special season for bloodletting.

* * *

It is precisely the spiritual power, joy, and generosity of Ramadan that the cynical propagandists of ISIS are trying (and, I would argue, failing) to redirect for their own demented purposes. They will be unsuccessful because for almost all Muslims, Islam is still a beautiful religion whose truths satisfy the mind and whose rituals fill hearts with peace. The idea of Ramadan as a season of cruelty and aggression is not just incorrect but unthinkable. So how does it become thinkable?

A religion is not simply a set of beliefs and rituals. It is a community that enshrines and transmits wisdom across generations and, in the case of Islamic civilization, across continents. Such a tradition enables the believer to know what they must do, but also answers questions like: Why must I do this? What is the nature of the world such that this ritual means something? What is the soul and how will it be changed by this act? Institutions like the Sufi orders, Islam’s philosophical and theological schools of thought, and its vast spiritual literature are delicate and precious, not easily recreated once destroyed or abandoned.

Rituals, when they cease to nourish the soul, can become mechanisms of control.Yet Muslim modernists and “fundamentalists” of many stripes share a conviction that they should jettison over a thousand years of Islamic spirituality, philosophy, and theology, and presume to extract truth and meaning from the Quran and Sunnah (the sayings and doings of the Prophet Muhammad) all by themselves. For the modernizing reformers (Muslim and non-Muslim), this spiritual deforestation is meant to bring Muslims out of a hidebound and even superstitious tradition into a more progressive future, while for revivalists it is meant to purify the tradition of its wayward accretions.

The effect is ultimately the same: believers bereft of a thousand years of wisdom flailing, at best, to make sense of their sacred texts, or at worst, capitalizing on ignorance among some of their co-religionists to enforce their vision of the world, no matter how brutal.

My Son’s Boyfriend Is Not His ‘Friend’

If gaydar is the ability to intuit someone’s sexual orientation merely by looking at them, what’s the flip side? It’s the ability to tell, with one word, whether someone might be homophobic. And that word, I’ve found, is “friend.”

“Where does your son’s friend live?” “What’s his friend’s name?” “Where does his friend go to school?” These questions have repeatedly been asked by people—neighbors, actual friends, relatives I essentially like—who already know that my 23-year-old son Sean is gay and that Henry is not his “friend.”

Related Story

There Is No ‘Neutral’ Word for Anti-Gay Bias

Henry is Sean’s boyfriend—I’ve made this point clear. And yet these smiling offenders persist in asking about him in a way that seems to both acknowledge and diminish the two’s relationship in a single stroke. The word “friend” catches in my ear; it may as well be an air-horn blast. I consider it my ultimate, secret weapon for outing what I consider to be the homophobes in my midst.

Brian Powell, however, sees it a little differently. A sociologist from Indiana University whose recent research suggests moral disapproval is the real reason same-sex marriage opponents want to ban the practice, Powell is no stranger to the controversy surrounding the subject. But, with the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark ruling Friday establishing a Constitutional right to same-sex marriage, he views the evolution of language as a key factor influencing those who are still calling my son’s boyfriend his friend.

“For some people it may well be homophobia,” Powell told me. “But I think for a large number of people today, with so much social change going on, it’s hard to keep up with what’s appropriate. The question is how to distinguish between the people who mean well but just don’t know what to say, and those who really have a hard time with gay relationships.” It’s a tough distinction indeed. I’m well aware of my bias—a protective, Mama Bear instinct that clouds my thinking about anything affecting the son of mine who happens to be gay (as well as my three straight kids).

I can see the logic in Powell’s theory that language simply needs to catch up to social progress, as it has during other seminal moments in history. After all, I experienced my own evolution of sorts, learning over many months how to weave my son’s sexual orientation into casual conversations on sports sidelines or at Scout socials. By now, though, just about everyone I know more than in passing is aware my oldest son is gay. Closer connections—including all the “friend” brandishers—know he’s got a boyfriend, a fiercely intelligent musician who can whip up a gourmet meal like nobody’s business (and lovingly transform my kitchen into an aromatic wreck in the process).

The word “friend” catches in my ear; it may as well be an air-horn blast.But while my gaydar may be lacking (I didn’t know for certain that Sean was gay until he came out to me at age 16), I can usually tell from these everyday exchanges who isn’t ready to hear about my son’s boyfriend as comfortably as they are, for instance, to hear about my daughter’s. After years of fits and starts, the staggering pace of progress in LGBT rights has made it a lot easier to sniff out those hiding behind a façade of gay acceptance in polite company. Even before Friday’s Supreme Court ruling, 37 states had legalized same-sex marriage over the last 11 years, and a new Gallup poll indicates a record 60 percent of Americans now support marriage equality.

Powell has witnessed this evolution firsthand in the years since his research began. In 2003, he noticed that when many of those he interviewed said the words “gay,” “lesbian” or “homosexual,” they used a verbal filler like “um” before the word or even lowered their voices, “not unlike when I was growing up,” he recalled, “and my mother said the word ‘cancer.’” By 2010, study participants had all but ceased these verbal tics. “The change we’ve seen over the last dozen or so years,” he posited, “is a result of a combination of factors: a very strong social movement; a very effective legal campaign; changes in the media; and open discussions in households and workplaces about these issues.”

But this sea change—and its effects on the language surrounding gay rights—hasn’t even caught up with everyone in the trenches. Powell himself has gay friends who won’t refer to themselves as husband and husband or wife and wife, if only because they hadn’t heard others like themselves referring to their spouses this way in the past. “People’s use of language is very much shaped by the language they used while they were coming of age,” Powell said. “Words are hard to get used to.”

Even a linguist wrestles with the “right” terminology. “Do we say gay marriage, same-sex marriage or marriage equality?” mused Geoffrey Nunberg, an adjunct full professor of linguistics at University of California at Berkeley. “It’s hard to distinguish genuine micro-aggression from mere discomfort,” explained Nunberg, whose many books include The Way We Talk Now and The Years of Talking Dangerously. “When I first heard a friend of mine refer to his husband, I did a double take. Of course, he was talking about a male spouse. But it sat me up in my chair the first time I heard it. The line between confused and obtuse is not an easy one.”

“It’s hard to distinguish genuine micro-aggression from mere discomfort.”Are Powell and Nunberg being forgiving—or sage? I have to wonder if my age colors my perception of the issue, contributing to my cynicism. Powell is 60; Nunberg, 70. At 48, I barely remember when “women’s lib” was a thing, though I can vividly recall other major shifts toward gender, racial, and religious acceptance (and sadly, shifts backward as well). Bearing witness to a decade or two less of historical trends may place me at a disadvantage in fairly assessing what’s happening on my watch, and often in my own home.

Maybe I’m splitting hairs and getting greedy on my son’s behalf. He is, in a way, fortunate to be young and gay during a period in history where the combination can seem irresistible and widely in vogue. For his part, Sean finds the “friend” phenomenon merely “annoying,” he told me, “especially after Henry has been introduced as my boyfriend. It shows social tactlessness.”

But even my son has to speculate how much this apparent and subtle resistance to social progress actually affects his day-to-day life. How damaging is these folks’ discomfort on a practical level? “This neutral-toward-negative language, in terms of the continuum, may be somewhat negative, but compared to other things, I don’t think this is quite as important,” Powell reassured me. “If in a few years people are still doing this, it would be a sign of resistance.”

Confusion over language can be a good thing, too. It means people are actually thinking about what to say and why, instead of lapsing into outdated terms or callously disregarding the social change that’s otherwise impossible to ignore. “Once language settles into a particular pattern, then you don’t have to think about it anymore,” Nunberg said. “It’s only when you have to stop and think, ‘Do I call him a Negro or black, a Jew or a Hebrew?’ that it gets people talking and makes them aware there are issues here. Language is full of these decisions we have to make now.”

And full of decisions about how to respond as well. My inborn repulsion to any form of confrontation means I don’t overtly correct offenders who refer to Sean’s “friend.” But I never let their wording pass unchallenged. When they pepper me with questions, I always respond, “His boyfriend’s name is Henry,” “His boyfriend is a grad student in Germany,” or “His boyfriend’s family is from Maryland.” In my own way, I’m going to make sure they fully acknowledge my son.

And, according to Powell and Nunberg, that’s exactly how I should play it. “If you say ‘boyfriend’ back, you’ve made the point,” Nunberg said. I’m also wearing them down bit by bit—or, if they’re simply unsure, I’m subtly pointing the way by affirming the new wording, increasing their comfort with it. “This is a matter of strategy,” Nunberg pointed out. “You can’t change people’s minds about things directly, but you can change the way they talk about things, and that may change how they think. Nobody likes to be a hypocrite.”

June 27, 2015

Obama's Grace

I think Barack Obama’s eulogy yesterday for parishoners of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston was his most fully successful performance as an orator. It was also one that could have come only at this point in his public career—and not, for instance, when he was an intriguing figure first coming to national notice, as he was during his celebrated debut speech at the Democratic National Convention in Boston 11 years ago; or when he was a candidate fighting for political survival, as he was when he gave his “Race in America” speech in Philadelphia early in 2008.

I’ll explain why I say so, but first a word about the odd circumstances in which I’ve heard and learned about the speech.

* * *

During the past week’s tumultuous events I have been physically and electronically removed from the swirl of news. Through the Confederate-flag aftermath of the murders in Charleston, to the Supreme Court’s healthcare and same-sex marriage rulings, to the president’s speech yesterday, I wasn’t in range of TVs or radios or more than a little trickle of the Internet and thus am catching up on everything all at once now.

Our scene of removal was the American Prairie Reserve in northeastern Montana, a Serengeti-scale longterm project to restore the northern grasslands to their original plant and animal population. It is a deeply impressive undertaking, and part of its power is the very fact that it is so far distant from urbanized America and its dramas and concerns. We’ll be writing more about it.

Yesterday, on our Cirrus flight down from northern Montana to the Denver area, we were listening to news programs on Sirius XM radio—which is (properly!) designed so that the news/music programming automatically blanks out whenever there’s a transmission on the air-traffic control frequencies. We were about 100 miles (or 30 minutes) north of Gillette, Wyoming, where we’d planned to make a refueling stop, when we came across a station playing the memorial service for Reverend Clementa Pinckney. We began listening, and heard the introduction for the president when we were about 20 minutes out.

The closer we got to the airport, the more frequent the air-traffic chatter became. In the final few minutes, it was back and forth: “We do not earn grace. We don’t deserve it. It is freely given by God—” “—Cirrus Five-Sierra-Romeo, runway three-four in use, report ten miles out, altimeter three zero two four—” “—We cannot leave our children in poverty.” It was only when we’d landed and were rolling along the taxiway to the refueling area, and the controller part of the conversation was done, that Sirius kicked back in with someone singing Amazing Grace. Deb and I looked at each other and thought: Could that have been Obama?

* * *

And of course it was. His singing was the aspect of the speech that will be easiest to remember. That is in part because it was so unusual and in part because it was so brave: Obama sang well, but not perfectly. For someone so precise and aspiring-to-perfection in most other realms of achievement, and so obviously hyper-aware of his levels of skill (he told Marc Maron in his remarkable WTF interview that he didn’t like playing basketball any more, now that he recognized that age had made him the weakest player on the court), singing like another enthusiastic parishioner, and not like a featured member of the choir, was brave and said something about his comfort with this crowd.

And of course he was aware that “this crowd” was not simply the many hundreds packed into that arena but the many millions around the world who would see it live, or later on. I cannot emphasize strongly enough the value of seeing this speech, in one of the video versions now available, versus just reading the text. (For the record: a video of the full nearly five-hour session is here, with Obama appearing around time 3:55; a New York Times video of his 35-minute speech itself is here; and the White House transcript of his remarks is here.) Like most Obama speeches, the text is indeed carefully written. But it is something entirely different as … I was going to say “as delivered,” but really the term is “as performed.”

Here are the three rhetorical aspects of the speech that I think made it more artful as a beginning-to-end composition than any of his other presentations:

— The choice of grace as the unifying theme, which by the standards of political speeches qualifies as a stroke of genius.

— The shifting registers in which Obama spoke—by which I mean “black” versus “white” modes of speech—and the accompanying deliberate shifts in shadings of the word we.

— The start-to-end framing of his remarks as religious, and explicitly Christian, and often African-American Christian, which allowed him to present political points in an unexpected way.

* * *

On grace:

When I finally watched the speech today, having been aware that it ended with Amazing Grace, I was increasingly surprised by the way in which Obama had built the whole preceding part of the speech toward that conclusion.

What were the advantages of his emphasizing grace—and not “justice” or “compassion” or “equity” or “opportunity”—as the recurring note of this speech? There were many:

— The president, the most powerful man in the world, could put himself in the closest thing possible to a stance of humility. “We don’t earn grace. We're all sinners. We don't deserve it. But God gives it to us anyway.”

— It allowed him to recast one part of the shooting’s aftermath in the most glorious way. When the families of the nine murdered churchgoers told the killer that they forgave him, one undertone of their saintliness was that we might be in for another “noble victim” episode. Black people would be killed or abused; their survivors and community would prove their goodness by remaining calm; and in part because of their magnanimity, nothing would change.

But by characterizing their reaction as a reflection of grace rather than mere “forgiveness,” Obama was able to present it as something much different than patient victimhood:

[The killer of Reverend Pinckney and eight others] surely sensed the meaning of his violent act. It was an act that drew on a long history of bombs and arson and shots fired at churches, not random, but as a means of control, a way to terrorize and oppress. (Applause.) An act that he imagined would incite fear and recrimination; violence and suspicion. An act that he presumed would deepen divisions that trace back to our nation’s original sin.

Oh, but God works in mysterious ways. (Applause.) God has different ideas. (Applause.)He didn’t know he was being used by God. (Applause.) Blinded by hatred, the alleged killer could not see the grace surrounding Reverend Pinckney and that Bible study group—the light of love that shone as they opened the church doors and invited a stranger to join in their prayer circle. The alleged killer could have never anticipated the way the families of the fallen would respond when they saw him in court—in the midst of unspeakable grief, with words of forgiveness. He couldn’t imagine that. (Applause.)

The alleged killer could not imagine how the city of Charleston, under the good and wise leadership of Mayor Riley—(applause)—how the state of South Carolina, how the United States of America would respond—not merely with revulsion at his evil act, but with big-hearted generosity and, more importantly, with a thoughtful introspection and self-examination that we so rarely see in public life.

Blinded by hatred, he failed to comprehend what Reverend Pinckney so well understood—the power of God’s grace. (Applause.)

— It allowed him to use a genuinely brilliant rhetorical device through the “policy” portions of his speech. The president recited the words to Amazing Grace midway through the speech, before singing them at the end. Including these crucial, closing words: “Was blind, but now I see.”

Soon after reciting those words the first time, Obama said:

As a nation, out of this terrible tragedy, God has visited grace upon us, for he has allowed us to see where we’ve been blind.

And from that point on in the speech, he consistently used the “we’ve been blind / but now we see” pairing to present all the policy points he wanted to discuss. For instance, with emphasis added:

For too long, we were blind to the pain that the Confederate flag stirred in too many of our citizens. (Applause.) It’s true, a flag did not cause these murders. But as people from all walks of life, Republicans and Democrats, now acknowledge—including Governor Haley, whose recent eloquence on the subject is worthy of praise—(applause)—as we all have to acknowledge, the flag has always represented more than just ancestral pride. (Applause.) For many, black and white, that flag was a reminder of systemic oppression and racial subjugation. We see that now.

And on throughout the speech. We were blind to a problem; but now through God’s grace our eyes have opened; and we can see what we should do. Another example:

For too long, we’ve been blind to the unique mayhem that gun violence inflicts upon this nation. (Applause.) Sporadically, our eyes are open: When eight of our brothers and sisters are cut down in a church basement, 12 in a movie theater, 26 in an elementary school. But I hope we also see the 30 precious lives cut short by gun violence in this country every single day…

The vast majority of Americans—the majority of gun owners—want to do something about this. We see that now.

If you watch the speech again, note how carefully the “was blind, but now I see” theme knits together its elements. As a matter of composition, this is harder to pull off than you would think. And as a matter of political framing, it may not actually make a difference, but it’s as much as a political speech could possibly do to induce people to think about issues in a different way. Appreciate how this approach comes across, versus “you were wrong, we are right.”

* * *

On shifting registers:

— Listening to chopped-up snippets of the speech in the airplane, I was struck by something that was all the more impressive when I heard the whole thing today. That was the way Obama, certainly on purpose, “code switched” with regularity through the speech. Sometimes he spoke almost as if he were an AME preacher, and certainly as if he was so comfortable in this setting as to know its stresses and pronunciations and styles. Listen for the words “Shout Hallelujah!” about 12 minutes into the speech to hear this tone. (If I do a line-by-line annotation, I’ll mention the times when he speaks in each register. But it’s not that hard to pick out.)

In other places—including, fascinatingly, his most explicit discourse on racial justice late in the speech—Obama sounds as neutrally professional-class-white-American as he does in most speeches from the Oval Office. When Obama first emerged as a national figure, the both-black-and-white story of his personal background conveniently paralleled the “bring us together” message of his political oratory. Manifestly the Obama years have not been a time of bridging the red-versus-blue divides. But I thought this speech more completely illustrated his own bridging potential than others he has given. Paralleling his shifts in diction was a surely non-accidental shift in his use of the word “we.” At different points in the speech he uses it to mean: we Christians; we African-Americans; we members of the black church; we parents; we people of all faiths and any faith; we Americans.

In his 2004 debut speech Obama had to explicitly spell out that he embodied the different strands of America: white mother from Kansas, black father from Kenya, himself the more fully American because of that mixture. In this speech he conveyed that message implicitly, through diction and use of “we.”

One thing we’ve learned about post-presidencies is that much of the poison drains away. We like nearly all of these people better once they’re out of office than when they were in the middle of the fray. You can imagine a post-presidential Obama being able to do more, on the “bring us together” front, than the poison of today’s national politics has allowed him to do in office.

— Here is another reason to watch rather than just read about the presentation. It reinforces the fact that this was a major national ceremony, involving fundamental discussion of national issues and prospects, in which all the major participants were black: president, preachers, mourners, congregation. I can’t think of a comparable previous event. Someone writing about our time will, I think, note it as an important step that this was treated not as a “minority” commemoration but as a central American discussion.

* * *

On religion:

If asked to describe Obama (as I once tried to do here), I would probably use up a lot of other adjectives before I got to “religious” or “Christian.” Obviously that is not because I believe he is a secret Muslim. It is just because he has struck me as so coolly cosmopolitan, and so much more likely to explain his views with reference to history or literature or economics or jurisprudence than to the teachings of his faith.

But in this eulogy he was obviously completely at ease in the black church. He opened with a verse from the Old New Testament [Book of Hebrews], not even needing to spell out what he was quoting. He referred to the black church as the “beating heart” of the black community. Actually as “Our beating heart. The place where our dignity as a people is inviolate.” (Note this use of our.) He knew the cadence of preaching. And of course there was the hymn at the end.

I cannot presume to know whether Barack Obama is in a deep way a “believer.” I will say that no fair-minded person who watches this presentation can doubt that the church is also part of his beating heart. Again this is where I see post-presidential potential for him as a bridging figure. Some of the people who hate him most ferociously now might eventually be open to the grace of such a presentation.

* * *

I took minute-by-minute notes while watching the speech today, which I might conceivably apply in a follow-up post. For now I am out of time at the computer, and have certainly said enough about this speech.

I have my complaints about and disappointments with Obama. But I hate the conventional DC-media disdain for him as a guy too cool, too aloof, and too generally above-it-all to be interested in the grimy work of public affairs. Think of the columns that begin, “Barry is bored ...” We can’t yet fully reckon the ways his era has changed our country, from the long aftermath of the 2008 recession to the consequential court decisions good and bad. (Side point: political writers wonder when the Republican party will produce its next really shrewd strategist, the one who knows how to pick his battles rather than getting mired in obstructive pandering to the base. Such a figure already exists. His name is John Roberts.) But I think the events of this past week, leading to the Grace speech, will play an important part in the reckoning.

The Sports World's Slow Embrace of Gay Rights

The Supreme Court’s declaration that same-sex marriage was constitutional triggered widespread jubilation across the United States on Friday, as millions of people took to Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to show their support. This enthusiasm was matched by numerous brands, such as Chipotle and Target, who used cleverly-produced tweets to trumpet their position on Twitter.

The response from the country’s sports teams, by contrast, were relatively muted. Of the 122 teams in the four major American professional sports leagues—the NFL, NBA, MLB, and NHL—only five explicitly mentioned Friday’s ruling as of 7:30 pm Eastern time last night. Three—baseball’s San Francisco Giants, football’s San Francisco 49ers, and basketball’s Golden State Warriors—hail from the famously progressive Bay Area, while the other two (the NBA’s Los Angeles Clippers and Sacramento Kings) play elsewhere in blue-state California.

“Professional sports teams still haven’t been able to shake that toxic culture of masculinity.”In fairness, social media isn’t the only arena in which sports teams interact with their community, and several have expressed support for gay rights in other ways. The Seattle Mariners, for example, will fly a rainbow flag during their game against the Chicago Cubs on Sunday. But the silence of so many teams on Friday was nonetheless striking. Why is the professional sports world so slow to embrace a social change favored by a large majority of Americans?

Homophobia in sports has deep roots. In the 1980s, the Los Angeles Dodgers reportedly offered Glenn Burke, a player widely believed to be gay, $75,000 to marry a woman. Two decades later, the retired NBA player John Amaechi described rampant homophobia among his former teammates and the relative indifference of league authorities. Even in the absence of traditional gay bashing, players encounter an extremely heteronormative environment when entering the world of professional sports. At the NFL Combine in Indianapolis, a venue for prospective amateur players to try out in front of professional executives and scouts, teams reportedly asked the players whether they were married or had a girlfriend.

“Professional sports teams still haven’t been able to shake that toxic culture of masculinity,” said Dave Zirin, a journalist who specializes in the intersection of sports and progressive politics. “It’s still something that dominates the industry in a much more intense way than executives would like to admit.”

Will American sports eventually embrace gay equality? According to Zirin, leadership is unlikely to come from the top. “It’d certainly be welcome if a commissioner were to come out strongly in favor of same-sex marriage,” he said. “But doing so would put their bosses—the league owners—on the spot. That might prove polarizing at the next owner’s meeting.”

A likelier driver of change may be the players. When Jason Collins became the first active NBA player to announce his homosexuality in 2013, stars like Kobe Bryant and Dwayne Wade tweeted out their support. But Collins—who has since retired—remains a singular figure, and the prediction that his coming out would lead to several others has not yet come true. The beliefs of players like Minnesota Vikings cornerback Josh Robinson, who on Friday compared same-sex marriage to pedophilia, no doubt contribute to the reluctance of closeted players to announce that they are gay.

Instead, Zirin believes that change is likely to occur not through executive fiat but rather a persistent, under-the-radar effort.

“People forget that professional sports are social institutions, and that social institutions change when people organize on a granular, grassroots level within those institutions,” he said.

Ted 2 and Translating Seinfeld: The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

Dumber Than Your Average Bear

Wesley Morris | Grantland

“You never expect a movie to hurt you. Disappoint? Dismay? Depress? Fine. But when a movie has a field day asserting the humanity of a fake toy bear at the expense of your own, it hurts.”

The Truth About TV’s Rape Obsession: How We Struggle With the Broken Myths of Masculinity, On Screen and Off

Sonia Soraiya | Salon

“Rape on television is the theater through which both men and women grapple with masculinity—with the fact that in its most corrosive form, masculinity is a quality that wreaks violence on those closest to it. Destruction and power are built into our concept of maleness; rape plots on TV work desperately to allow men that access to power while also codifying when it’s acceptable to use.”

Translating Seinfeld

Jennifer Armstrong | The Verge

“In one Radboud University study of Dutch viewers’ reactions to Seinfeld, viewers commonly reported being baffled by the show’s laugh track; the audience regularly missed the joke. Some of those who did laugh told researcher Elke Van Cassel that they were laughing only because the characters reminded them of Americans they knew.”

How Minions Destroyed the Internet

Brian Feldman | The Awl

“Minions are the Target graphic tees of the Internet.”

Taylor, Apple, Tidal and the Politics of the Rip Off

Eric Harvey | Pitchfork

“Those born during the CD’s late ‘90s/early ‘o0s sales peak have lived their entire lives in a world in which the economic and cultural value of music is an open question.”

Kate Bolick Was My On Call Dating Advice Guru

Allison P. Davis | The Cut

“As we prepare to part at the end of the meal, a bride and groom walk into the restaurant. They were literally just married: She’s still clutching her bouquet. I look at Kate. Kate looks at me. The meaning is clear: Kate Bolick’s advice is going to get me married by the end of the weekend.”

Why Women Apologize and Should Stop

Sloane Crosley | The New York Times

“When a woman opens her window at 3 a.m. on a weeknight and shouts to her neighbor, ‘I’m sorry, but can you turn the music down?’ the ‘sorry’ is not an attempt at unobtrusiveness. It’s not even good manners. It’s a poor translation for a string of expletives.”

How Smosh’s Doofy YouTube Videos Got 7.4 Million Views

Jane Borden | LA Weekly

“Smosh is exceptionally childish and dumb. But teens and children are their market, and that market regenerates. When asked why teen-focused digital content is so popular in general, Hecox replies, ‘People have a lot of time when they’re younger. Then they start getting jobs.’”

The Mark Wahlberg Playbook Is the Oldest One in Hollywood

Anne Helen Petersen | Buzzfeed

“When people say they love Mark Wahlberg films, they’re saying they love this kind of film—like their classic Hollywood antecedents, they’re basic, broadly palatable, and incredibly enjoyable, if not entirely memorable. They rank high on the ‘I’ll totally watch this on Netflix’ scale.”

What Happened to Nina Simone?

In the 1990s, some years after Nina Simone had fled America, the country that fueled both her meteoric fame and her crippling depression, she agreed to give an interview at her home in France. During the exchange, a seemingly sincere television personality asks her to gauge the how far the civil-rights movement had come.

“There aren’t any civil rights,” Simone says.

“What do you mean?” the bemused interviewer asks.

“There is no reason to sing those songs, nothing is happening,” Simone replied. “There’s no civil-rights movement. Everybody’s gone.”

Related Story

Simone’s exile hadn’t been a sunny haze of Riviera vistas and Haut-Médoc wines. After spending some time in Barbados and two years in Liberia, she settled in Paris, where, broke, she performed in dingy cafes for a few hundred dollars a night. But still, she expressed no longing for the country where she’d been rich and famous.

The clip is from a new documentary, What Happened, Miss Simone?, which arrived on Netflix on Friday. The film is just one part of a renewed interest in the singer, with an accompanying tribute album set for July and two other Simone-related films set for release this year.

The timing of this particular release, though, is poignant. On the same day that the documentary was released, President Obama delivered a eulogy for Clementa Pinckney, the state senator and Mother Emanuel A.M.E. pastor who was murdered by a white supremacist on June 17. What Happened, Miss Simone?, which gets its title from a Maya Angelou poem, focuses heavily on the years after Simone went from being an ambivalent activist to a pillar of the civil-rights movement.

As depicted in the film, what ultimately spurred the artist to risk the safety of her musical success in order to pursue activism was another act of violence in a church—the 1963 bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, which killed four young black girls who’d just concluded a Bible-study session.

Accounts differ, but legend has it that it took Simone anywhere from 20 minutes to an hour to write “Mississippi Goddam” in response—an anthem that would become a standard in the 1960s protest repertoire.

Writing in The New Yorker last year, Claudia Roth Pierpont eloquently tied the song to its era.

A freewheeling cri de coeur based on the place names of oppression, the song has a jaunty tune that makes an ironic contrast with words—“Alabama’s got me so upset, Tennessee made me lose my rest”—that arose from injustices so familiar they hardly needed to be stated: “And everybody knows about Mississippi, goddam!”

For Simone, who lived next door to Malcolm X in Mt. Vernon, New York, and whose first interaction with Martin Luther King, Jr. involved a heated declaration that her activism was on the “by any means necessary” part of the scale, the tune bore none of the turn-the-other-cheek wholesomeness of other protest songs. “Mississippi Goddam” was also an upshot of Simone’s time spent in the care of intellectual co-conspirators like Lorraine Hansberry, James Baldwin, and Stokely Carmichael.

Via unreleased photos and diary entries as well as audio and video interviews, the film pivots on this revolution in song. Dick Gregory, the comedian, erstwhile presidential candidate, and activist, appears onscreen to doff his cap. “If you look at all the suffering black folks went through, not one black man would dare say ‘Mississippi Goddam.’ We all wanted to say it. She said it.”

In other words, Simone’s brand of activism was like no one else’s. Born Eunice Waymon and brought up in Tryon, North Carolina, a small town just miles from the South Carolina border, she was a piano prodigy who dreamt of playing Bach at Carnegie Hall as the venue’s first black female performer.

Following a stint at Julliard, Eunice became Nina after she was rejected from the Curtis Institute of Music, ostensibly because of her race. She took the stage name so that her church-going parents wouldn’t find out that she’d starting playing piano for money at a bar in Atlantic City.

In a perhaps overlong biographical sweep, the film does deliver viewers to Carnegie Hall, where “Mississippi Goddam” is performed and recorded as an album before a mostly white audience. “This is a show tune, but the show hasn't been written for it yet,” Simone says acidly in the introduction.

The backlash was furious. The song was banned in several states. Simone’s daughter Lisa describes how boxes of the records would return from radio stations around the country cracked in half. Her career never fully recovered. But the show went on. In 1965, Simone performed “Mississippi Goddam” before tens of thousands of marchers in Selma on a stage propped up by coffins.

In her later years, Simone, who died in 2003, recounted how the moment of credible civil-rights resistance had seemingly passed. “The protest years were over not just for me but for a whole generation and in music, just like in politics, many of the greatest talents were dead or in exile and their place was filled by third-rate imitators,” she wrote in her 1991 memoir.

But in a year with no shortage of harrowing stories and despite Simone’s late-in-life exhortations about her own irrelevance, there may never be a more appropriate time to slake a new generational curiosity about Simone than now. What Happened, Miss Simone is a pretty good place to start.

June 26, 2015

A Eulogy in Charleston

On Friday, President Obama stood in the White House and delivered a triumphant statement on the Supreme Court’s affirmation of same-sex marriage. Then he traveled to Charleston, South Carolina, for a very different task: delivering a eulogy for Clementa Pinckney, the pastor and South Carolina state senator who was gunned down last week at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church.

The president spoke at the church that Pinckney led, offering a remembrance of a man he knew personally. In paying tribute to Pinckney, Obama joins a number of leaders—local and national, secular and religious—who have testified to the ways in which he affected their lives.

President Obama spoke for about 40 minutes, touching on the personal, political, and religious, and melding sermon with eulogy and, movingly, song. The theme of the speech was grace, but the president also talked about racism, poverty, gun control, the legacies of black American churches, and Confederate iconography.

His words:

We are here today to remember a man of God who lived by faith. A man who believed in things not seen. A man who believed there were better days ahead, off in the distance. A man of service who persevered knowing full well he would not receive all those things he was promised, because he believed his efforts would provide a better life for those who followed.

If you were following the speech strictly from the text of the chyrons on television, you might have walked away thinking the president’s eulogy consisted of only a few short statements—a pro forma sentence about the nation’s shared grief, a small digression about the Confederate flag, and a communal singing of “Amazing Grace.”

But the speech was more than soundbites. It wasn’t readymade for a television newscast; it was a conversation that demanded the full attention of its audience. It was directed not just at the political leaders who filled the pews in Charleston, including Vice President Joe Biden, House Speaker John Boehner, and Hillary Clinton, but also ordinary Americans across the country who paused to pay their respects. “They were still living by faith when they died,” Obama said of the nine Americans who were killed last week.

Dylann Roof was “blinded by hatred” when he shot Pinckney, he said:

He failed to comprehend what Reverend Pinckney so well understood—the power of God's grace. He's given us the chance where we've been lost to find our best selves. We may not have earned it, this grace, with our rancor and complacency short-sightedness and fear of each other, but we got it all the same.

Earlier this week, David Blight wrote for The Atlantic about attending an event in April at which both he and Pinckney were set to deliver speeches. It was a commemoration marking the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War in Charleston. He wrote:

Pinckney reminded us that we were commemorating a national event of equal gravity and tragedy. Our Civil War, said the minister, had been brother against brother, “father against son, generation against generation.” Then he found a refrain: “We stand in the gate, the archway, and remember a war that divided houses.” King David had both won and lost in his divided house and he wailed of his pain. Reverend Pinckney pushed on with the image of “divided houses,” but to remind us that from such depths of agony can come a dawn of knowledge, understanding, and even-tempered healing. Pinckney was suddenly the voice of reconciliation for the vast chasms left by the Civil War, not merely the sins of Christians.

Last week, The Atlantic’s Matt Thompson explained Pinckney’s place within the worlds of both religion and politics:

Clementa Pinckney knew the history of his own city. He probably knew the name Benjamin Franklin Randolph, another black minister and state senator from Charleston to have died at the hands of angry white men, 147 years prior.

He may not have suspected that the person who had joined his small fellowship of believers at Mother Emanuel that night would sit with these few people for an hour, listen to their prayers and their blessings, then take up a gun and end their lives. But he knew that humankind had been cursed from its beginnings by hatred so potent it could be lethal—the third human mentioned in Pinckney’s Bible, after all, had killed another man out of jealousy for what he had.

Kevin Sack of The New York Times offered a fuller biography:

Clementa Carlos Pinckney, who was martyred last week in the basement of Charleston’s Emanuel A.M.E. Church, and who will be eulogized on Friday morning by the president of the United States, never lacked for either precocity or audacity.

He was ordained at 18, and assigned almost immediately to fill in for an ailing pastor in Green Pond, S.C. He presided over student government in high school and in college and, seeing politics as complementary to his ministry, earned master’s degrees in both divinity and public administration. At 23, he became the youngest elected black member of South Carolina’s legislature.

In his speech, the president added another detail: Pinckney felt called to be a pastor at the age of 13. Last week, he died at the age of 41. It is fitting that he was eulogized by a president, and it may stand to be one of the defining speeches of Obama’s time in office. But the powerful speech only served as a reminder of how much the nation has lost.

The Modern Family Effect: Pop Culture’s Role in the Gay-Marriage Revolution

It you look at the trend line for the Gallup poll about American attitudes towards gay marriage, you’ll see that support for same-sex marriage, after cratering for a year, began to climb toward its now-historic height in 2009. A number of factors influenced that shift. Maybe one of them was Modern Family.

Related Story

'Love Is Love': Americans Celebrate Marriage Equality

It’s impossible to know how much entertainment ever drives society rather than merely reflecting it. But it’s hard to avoid the feeling that the past five or six years have seen a virtuous cultural cycle. 2009 was the year that audiences met Cam and Mitch, a gay couple living together with an adopted daughter. They weren’t married when the series began—Proposition 8 in their native California forbade them to, and they tied the knot once it was overturned—but they were navigating the challenges of being in a long-term relationship on screen every week as around 10 million people watched at home. The show became one of the few cross-culturally appealing TV works of the Obama years, viewed in red states and blue states, name-checked by Ann Romney and the president alike. A 2012 Hollywood Reporter poll found that 27 percent of likely voters said that depictions of gay characters on TV made them more pro-gay marriage, and there are news accounts of people crediting their newfound sympathy toward gay people to Modern Family.

Of course, television has spotlighted queer people for decades, both in major roles on shows like Will & Grace and Glee, and in minor ones on shows like All in the Family and Golden Girls. Progress has happened fitfully: Many of these programs perpetuated stereotypes, and often they focused on white people at the exclusion of all others. Cam and Mitch have been about as tame as anyone could ask—in contrast to the straight couples they hang out with, they rarely touch, never talk about sex, and make a big deal over kissing in public. But the fact remains that each popular depiction of gay life helped encourage networks to take chances on others, and today there’s unprecedented diversity in representation of sexuality on television, as shown in programs like Empire and Orange Is the New Black.

The next-generation Modern Family might focus on couples in the process of negotiating the rules as they go along.Did any of this matter to the Supreme Court, which just declared gay marriage a legal right? Antonin Scalia, whose dissent charged the majority with orchestrating a “super-legislative” power grab, clearly thinks the justices were influenced by popular attitudes and emotions rather than the idea that equal protection under the law applies to marriage. But speculating on judges’ motives is a losing task, and the rise in national support for gay marriage possibly owes less to sitcoms than it does to demographic shifts and political organizing efforts following ballot-box defeats in 2008.

When it comes to pop culture, it’s probably best to just focus on what it can accomplish now, in the wake of Obergefell v. Hodges. Film and TV has helped popularize the idea that gay couples can be “normal”—as banal as Cam and Mitch; as in dire need of counseling as Cyrus and James on Scandal; as lovingly parental as Stef and Lena on The Fosters. But the idea of “normal” is a dangerous one that can validate old, oppressive ideas about who’s abnormal. Same-sex couples, statistics show, often differ from straight ones when it comes to divisions of labor, monogamy, and problem-solving, and many gay people don’t want to get married and won’t after this decision. The norms are less fixed for same-sex couples—which can be a beautiful and frightening thing for them, and a fabulous prompt for storytellers.

One example: HBO’s Looking closed its most recent (and final) season with two men moving in together—and promptly getting into a fight when one party frankly stated his interest in sleeping with other people. Another example, related to both marriage and a different, arguably more urgent LGBT struggle: Sophia of Orange Is the New Black figuring out what it means for her wife and kid now that she has transitioned to female. The next-generation Modern Family might spotlight other kinds of situations that are new for TV, focusing on couples in the process of negotiating the rules as they go along. Already, Cam and Mitch seem a bit old-fashioned, which is in itself a sign of progress that they might deserve some credit for.

Ramadan Attacks on Three Continents

Updated at 1:13 p.m. ET.

On Friday, three deadly attacks struck Tunisia, Kuwait, and France. Many details are still unknown, and death tolls are not yet final, but the incidents on three different continents all coincided with Ramadan. Although all three attacks have been described as terrorism, there are no clear indications yet that the attacks were coordinated.

Earlier this week, Islamic State spokesman Abu Muhammed al-Adnani called for the organization’s followers to execute more attacks during Ramadan. “Aspire to battle in this noble month,” al-Adnani urged, according to a translation posted on Twitter by Charlie Winter, a senior researcher studying jihadism at the Quilliam Foundation.

While ISIS has claimed the attack in Kuwait, there have been no statements of responsibility for the events in France or Tunisia.

Sousse, Tunisia

Two gunmen opened fire at a beach resort, killing at least 37 people, according to the New York Times. According to the country’s Interior Ministry, one of the gunmen was killed, while another is still on the loose. It’s not yet known how many of those killed in the attack were foreigners, said the AP, but “during the holy month of Ramadan, those on the beach tend to be tourists.” Early reports indicate most of the victims were British and German.

In March, nearly two dozen people—most of them tourists—were killed in an attack at Tunisia’s Bardo Museum. “There's a clear logic at work when terrorists attack tourists,” wrote The Washington Post’s Adam Taylor at the time. “Not only do these attacks spread terror internationally, they also have a negative effect on the economy of the local government.”

These attacks are particularly significant because Tunisia’s fledgling democracy is seen as one of the fragile successes of the Arab Spring. After the Bardo Museum attack, Atlantic contributor Larry Diamond wrote that the violence didn’t diminish Tunisia’s accomplishments, or its prospects.

Tunisia remains full of promise. Alone among the Arab Spring states, it has achieved a remarkable level of political compromise among secular parties and the principal Islamist party, Ennahda. This has been due in no small measure to the leadership of Ennahda founder Rachid Ghannouchi, who has, at every crucial turn on the sometimes-troubled path from dictatorship, embraced flexibility and moderation and promoted the vision, as he put it in a March 20 statement celebrating the country’s 59th anniversary of independence, of “a republic of freedom, democracy, and social justice.”

Kuwait City, Kuwait

Over the last few years, the tiny Gulf state of Kuwait has been immune to the jihadist violence roiling many other countries in the Middle East. But on Friday, a terror attack punctured Kuwait’s calm.

“Kuwaiti parliament member Khalil al-Salih said worshippers were kneeling in prayer,” Reuters reported, “when a suicide bomber walked into the Imam al-Sadeq Mosque side and blew himself up, destroying walls and the ceiling.” At least 25 people have died in the bombing, and more than 200 are injured. Several of the victims—mainly men and boys attending midday prayers—remain missing. The Islamic State group claimed responsibility for the attack and identified the suicide bomber as Abu Suleiman al-Muwahed.

In a statement released after the attack, ISIS referred to its target as a “temple of rejectionists,” using a term the extremist Sunni group frequently uses to describe Shiite mosques. Friday’s attack was the first to target Kuwait’s Shiites, who make up about one-third of the country’s population.

“This incident targets our internal front, our national unity,” Sheikh Jaber al-Mubarak al-Sabah, Kuwait’s prime minister, told Reuters. “But this is too difficult for them and we are much stronger than that.”

Lyon, France

An attacker stormed into an American-owned factory, tried unsuccessfully to set off an explosion, and decapitated one person. According to French President François Hollande, the killer has been arrested. The man, whose identity has not been confirmed, had worked for the victim.

This post will be updated.

Humans Might Be the Ultimate A.I. Thought Experiment

Midway through the recent movie Ex Machina, one computer programmer asks another why he invented a machine that can think, talk, and act like a human. “That’s an odd question,” replies the tech visionary played by Oscar Isaac. “Wouldn’t you, if you could?”

Judging from both fiction and the real world, mankind itself finds the question of “why” a silly one when it comes to the notion of artificial intelligence. Whether it’s Tony Stark engineering Ultron as much for world peace as for his own ego, or Apple relentlessly upgrading Siri so as to offer ever-more-precise brunch recommendations, machines seem destined to get smarter—as Isaac’s character says, “the arrival of strong artificial intelligence has been inevitable for decades. The variable was when, not if.”

Related Story

Ex Machina Explores the Thrill (and Horror) of Romantic Uncertainty

AMC’s new show Humans underlines the simple fact that most people will get no say in whether the robots arrive, just as it’s always been with socially transformative technology. In its version of the present day, fake humans programmed to take orders from real ones have recently come to act as family maids, elderly caretakers, physical therapists, manual laborers, and prostitutes. Why? “The best reason to make machines more like people is to make people less like machines,” a TV talking head explains towards the end of the pilot. “The woman in China who works 11 hours a day, stitching footballs; the boy in Bangladesh inhaling poison as he breaks up a ship for scrap; the miner in Bolivia risking death every time he goes to work—they can all be part of the past.” The immediately apparent irony is that those words are being taken in by a middle-class English family whose newly bought “synth,” Anita, is cooking dinner in the other room. Dad rifles through the instructional literature that came with it—her?—and lingers on an “Adult Options, 18+” pamphlet.

With its small-bore, domestic focus, Humans has the potential to stand out in the supersaturated genre of A.I. fiction, which tends to consist—just to use the previously mentioned examples from 2015—of ethical ruminations on the soul, as in Ex Machina, or disaster/horror fantasies about being overtaken by our creations, as in Age of Ultron. It’s not that those ingredients aren’t in here: One plotline follows a group of synths who’ve somehow gained true consciousness and are trying to escape captivity, while the Anita narrative is plenty creepy thanks to fears of possibly sinister bot behavior that play on the same maternal anxieties as, say, A Deadly Adoption. What’s different is that as a serialized television show (a co-production with Britain’s Channel 4 and Kudos), Humans can run a greater number of thought experiments, and for longer, than a film or an episode of Twilight Zone or Black Mirror can.

As serialized TV, Humans explore more questions, for longer, than a film or Black Mirror episode.That mission is helped by the show’s clean, straightforward look, which indeed recalls Black Mirror and other recent trans-Atlantic outings like Orphan Black. Unlike so many hyper-stylized American prestige dramas, it wants to be a sturdy vessel for plot and ideas, not Emmy bait. The result is a cohesive and consistently engaging viewing hour that hopscotches between a variety of story types: chase, horror, comedy. Katherine Parkinson, as a workaholic mom in danger of being replaced at home, and William Hurt, as a retired inventor chafing at his government-owned elderly-care bot, movingly remind viewers of what makes humans human. But it’s the synth-actors’ performances that are the most striking. With lime-green irises and arms that don’t swing as they walk, these droids are both alien and sympathetic, and Gemma Chan as Anita somehow conveys budding consciousness even as she keeps her face entirely blank.

In the two episodes I’ve seen, the main action has largely been driven by deviants: a handful of synths illegally programmed to have souls who therefore don’t want to work as smiling slaves. But perhaps the more interesting narrative threads arise from drone-people behaving exactly as they’re supposed to—obedient and unfeeling. An overachieving teenager starts flunking her classes, reasoning that there’s no reason to excel in a world where machines can perform brain surgery. Anita’s arrival makes Parkinson’s Laura quietly struggle with the question of her role as a mother. And Hurt’s character holds paternal affection for his obsolete, malfunctioning synth, and has to reckon with a literal nanny-state situation due to his age. Disconcertingly plausible and emotionally complicated, these are the kinds of scenarios that civilization will have to ponder before the arrival of the singularity, if there’s chance to ponder anything at all.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower