Brian Clegg's Blog, page 137

July 24, 2012

Causality vs correlation in military domestic violence

Does this get you pregnant?Sorry if that title sounds a bit like an obscure scientific paper, but there's an important point to make. I was listening last night to a radio documentary about domestic violence among military personnel and it made the most fundamental scientific blunder. It missed a phrase that should be tattooed on the hand of every broadcaster: 'Do not confuse correlation and causation.'

Does this get you pregnant?Sorry if that title sounds a bit like an obscure scientific paper, but there's an important point to make. I was listening last night to a radio documentary about domestic violence among military personnel and it made the most fundamental scientific blunder. It missed a phrase that should be tattooed on the hand of every broadcaster: 'Do not confuse correlation and causation.'Let me take a step back with an example that was used on my Operational Research masters course. For a good few years after the war, the pregnancy rate in the UK had a strong correlation with the import of bananas. When more bananas were imported there were more pregnancies. Fewer bananas, fewer pregnancies.

The amusing response is that the bananas were causing the pregnancies. But to accept that at face value is to miss two other possibilities. One is simple reversal. The pregnancies could be causing the bananas. By this I mean that there could be a causal connection between someone being pregnant and increased consumption of bananas. Maybe pregnant women crave bananas. Or maybe young children (a common result of pregnancy) eat more bananas than older people.

The second, and much wider, option to explain the apparent link is that there is a third factor that causes both the increase in pregnancies and the increase in bananas. Perhaps there was more money around and this caused both. Or one of many other potential third factors.

I am not suggesting any of these alternative causal processes is correct, but that it would be absolutely stupid to make the initial assumption that because banana imports went up and pregnancies went up, eating bananas make you pregnant.

Now let's go back to that radio programme. Because it made just such a stupid assumption. Let's be clear again - I'm not saying what the causal link is, merely pointing out the unscientific way in which correlation was turned into a particular causality.

The topic of the radio programme was essentially that, despite denials from the MOD, there was more likelihood of domestic violence in an army household than a civilian one. The big, bad assumption was that being in the army (and the experiences you had there) made you a more violent person. There was no attempt whatsoever to look at the two alternative causalities. What if being a more violent than average person made you more likely to join the army? Was the causality the reverse of the one they assumed? For that matter could there be a third factor that caused people join the army and to be more violent?

This was sloppy journalism and bad science.

Published on July 24, 2012 23:14

Nature’s Nanotech #2 – The magic lotus leaf

This is one of a series of articles co-hosted with www.popularscience.co.uk

Living things are built on hidden nanotechnology components, but sometimes that technology achieves remarkable things in a very visible way. A great example is the ‘lotus leaf effect.’ This is named after the sacred lotus, the Nelumbo nucifera, an Asian plant that looks a little like a water lily. The plant’s leaves often emerge into the air covered in sticky mud, but when water runs over them they are self cleaning – the mud runs off, leaving a bare leaf exposed to the sunlight.

Living things are built on hidden nanotechnology components, but sometimes that technology achieves remarkable things in a very visible way. A great example is the ‘lotus leaf effect.’ This is named after the sacred lotus, the Nelumbo nucifera, an Asian plant that looks a little like a water lily. The plant’s leaves often emerge into the air covered in sticky mud, but when water runs over them they are self cleaning – the mud runs off, leaving a bare leaf exposed to the sunlight.

Water on a lotus leafOther plants have since been discovered to have a similar lotus leaf effect, including the nasturtium, the taro and the prickly pear cactus. Seen close up, the leaves of the sacred lotus are covered in a series of tiny protrusions, like a bad case of goose bumps. A combination of the shape of these projections and a covering of wax makes the surface hydrophobic. This literally means that it fears water, but more accurately, the leaf refuses to get too intimate with the liquid. This shouldn’t be confused with hydrophobia, a term for rabies!Water is naturally pulled into droplets by the hydrogen bonding that links its molecules and ensures that this essential liquid for life exists on the Earth (without hydrogen bonding, water would boil at around -70 Celsius). This attraction is why raindrops are spherical. They aren’t teardrop shaped as they are often portrayed. Left to their own devices, water drops are spherical because the force of the hydrogen bonding pulls all the molecules in towards each other, but there is no equivalent outward force, so the water naturally forms a sphere.The surface of the lotus leaf helps water stay in that spherical form, rather than spreading out and wetting the leaf. The result is that the water rolls off, carrying dirt with it, rather like an avalanche picking up rocks as it passes by. Because of the shape of the surface pimples on the leaf, known as papillae, particles of dirt do not stick to the surface well, but instead are more likely to stick to the rolling droplets and be carried away. As well as letting the light through to enable photosynthesis, this effect is beneficial to the leaves as it protects them against incursion by fungi and other predatory growths.Although the papillae themselves can be as large as 20,000 nanometres tall, the effectiveness of these bumps is in their nanoscale structure, with multiple tiny nobbly bits that reduce the amount of contact area the water has with the surface to a tiny percentage. After the effect was discovered in the 1960s, it seemed inevitable that industry would make use of it and there have been several remarkable applications.One example that is often used is self-cleaning glass – which seems very reasonable as the requirement is identical to the needs of the lotus leaf – yet strangely, what is used here is entirely different. Pilkington, the British company that invented the float glass process, has such a glass product known as Activ. This has a photo-catalytic material on its surface that helps daylight to break down dirt into small particles, but it also has a surface coating that works in the opposite way to the lotus leaf. It’s an anti-lotus leaf effect.The coating on this glass, a nanoscale thin film, is hydrophilic rather than hydrophobic. Instead of encouraging water to form into droplets that roll over the glass picking up the dirt as they go, this technology encourages water to slide over the surface in a sheet, sluicing the dirt away. In practice this works best with heavy rainfall, where the lotus effect is better at cleaning surfaces with less of a downpour – but both involve nanoscale modification of the surface to change the way that water molecules interact.Increasingly now, though, we are seeing true lotus leaf effect inspired products, that make objects hydrophobic. A process like P2i’s Aridion technology applies a nano-scale coating of a fluoro-polymer that keeps water in droplets. The most impressive aspect of this technology is just how flexible it is. Originally used to protect soldiers clothing against chemical attack , the coatings are now being applied to electronic equipment like smartphones, where internal and external components are coated to make them hydrophobic, as well as lifestyle products such as footwear, gloves and hats. Working like self-cleaning glass would be disastrous here. The whole point is to keep the water off the substance, not to get it wetter.We are really only just starting to see the applications of the lotus leaf effect come to full fruition. For now it is something of a rarity. Arguably it will become as common for a product to have a protective coating as it for it to be coloured with a dye or paint. Particularly for those of us who live in wet climates like the UK, it is hard to see why you wouldn’t want anything you use outdoors to shrug water off easily. I know there have been plenty of times when I have been worriedly rubbing my phone dry on my shirt that I would have loved the lotus leaf effect to have come to my rescue.Seeing nanotechnology at work in the natural world doesn’t have to help us come up with new products. It could just be a way of understanding better how a remarkable natural phenomenon takes place. In the next article in this series I will be looking at a mystery that was unlocked with a better understanding of nature’s nanotech – but one that also has significant commercial implications. How does a gecko cling on to apparently smooth walls?

Water on a lotus leafOther plants have since been discovered to have a similar lotus leaf effect, including the nasturtium, the taro and the prickly pear cactus. Seen close up, the leaves of the sacred lotus are covered in a series of tiny protrusions, like a bad case of goose bumps. A combination of the shape of these projections and a covering of wax makes the surface hydrophobic. This literally means that it fears water, but more accurately, the leaf refuses to get too intimate with the liquid. This shouldn’t be confused with hydrophobia, a term for rabies!Water is naturally pulled into droplets by the hydrogen bonding that links its molecules and ensures that this essential liquid for life exists on the Earth (without hydrogen bonding, water would boil at around -70 Celsius). This attraction is why raindrops are spherical. They aren’t teardrop shaped as they are often portrayed. Left to their own devices, water drops are spherical because the force of the hydrogen bonding pulls all the molecules in towards each other, but there is no equivalent outward force, so the water naturally forms a sphere.The surface of the lotus leaf helps water stay in that spherical form, rather than spreading out and wetting the leaf. The result is that the water rolls off, carrying dirt with it, rather like an avalanche picking up rocks as it passes by. Because of the shape of the surface pimples on the leaf, known as papillae, particles of dirt do not stick to the surface well, but instead are more likely to stick to the rolling droplets and be carried away. As well as letting the light through to enable photosynthesis, this effect is beneficial to the leaves as it protects them against incursion by fungi and other predatory growths.Although the papillae themselves can be as large as 20,000 nanometres tall, the effectiveness of these bumps is in their nanoscale structure, with multiple tiny nobbly bits that reduce the amount of contact area the water has with the surface to a tiny percentage. After the effect was discovered in the 1960s, it seemed inevitable that industry would make use of it and there have been several remarkable applications.One example that is often used is self-cleaning glass – which seems very reasonable as the requirement is identical to the needs of the lotus leaf – yet strangely, what is used here is entirely different. Pilkington, the British company that invented the float glass process, has such a glass product known as Activ. This has a photo-catalytic material on its surface that helps daylight to break down dirt into small particles, but it also has a surface coating that works in the opposite way to the lotus leaf. It’s an anti-lotus leaf effect.The coating on this glass, a nanoscale thin film, is hydrophilic rather than hydrophobic. Instead of encouraging water to form into droplets that roll over the glass picking up the dirt as they go, this technology encourages water to slide over the surface in a sheet, sluicing the dirt away. In practice this works best with heavy rainfall, where the lotus effect is better at cleaning surfaces with less of a downpour – but both involve nanoscale modification of the surface to change the way that water molecules interact.Increasingly now, though, we are seeing true lotus leaf effect inspired products, that make objects hydrophobic. A process like P2i’s Aridion technology applies a nano-scale coating of a fluoro-polymer that keeps water in droplets. The most impressive aspect of this technology is just how flexible it is. Originally used to protect soldiers clothing against chemical attack , the coatings are now being applied to electronic equipment like smartphones, where internal and external components are coated to make them hydrophobic, as well as lifestyle products such as footwear, gloves and hats. Working like self-cleaning glass would be disastrous here. The whole point is to keep the water off the substance, not to get it wetter.We are really only just starting to see the applications of the lotus leaf effect come to full fruition. For now it is something of a rarity. Arguably it will become as common for a product to have a protective coating as it for it to be coloured with a dye or paint. Particularly for those of us who live in wet climates like the UK, it is hard to see why you wouldn’t want anything you use outdoors to shrug water off easily. I know there have been plenty of times when I have been worriedly rubbing my phone dry on my shirt that I would have loved the lotus leaf effect to have come to my rescue.Seeing nanotechnology at work in the natural world doesn’t have to help us come up with new products. It could just be a way of understanding better how a remarkable natural phenomenon takes place. In the next article in this series I will be looking at a mystery that was unlocked with a better understanding of nature’s nanotech – but one that also has significant commercial implications. How does a gecko cling on to apparently smooth walls?Image from Wikipedia

Published on July 24, 2012 04:42

July 22, 2012

Hunting wild skeuomorphs

A skeuomorph sounds like a baddy on the set of Alien vs Predator, but in reality a skeuomorph is an object or feature that copies the design of, or is made to look like something else. And it's a topic of much soul searching among Apple fans at the moment.

Apple's skeuomorphic podcast app

Apple's skeuomorphic podcast app

There are some aspects of skeuomorphism few would question. Functional skeuomorphism is why spreadsheets look like sheets of lined paper accountants used to use, why a word processor is a bit like typing on a piece of paper, or why a button in a computer interface looks like - well - a button.

However the aspect that is causing some concern is a tendency to go beyond function to appearance for appearance sake. This can be a good thing - some kinds of decorative skeuomorphism work well with a computer. So, for instance, brushed aluminium goes well with an iMac. But the problem is with decorative appearance based on non-tech stuff like leather bindings on the address book and calendar, and wooden bookshelves. This can look just naff.

This isn't a new problem. I had a US made tape player and games console in the 1970s both of which had plastic fake wood finish - it looked terrible, and I could never understand why they did it, but I assume it appealed to the US consumer.

I think if Apple is sensible they will listen to the growing groundswell against this retro skeuomorphism and at the very least give the option of switching it off. After all, I even saw an article the other day that suggested that Microsoft now has better taste than Apple - surely a call to arms.

I think it's very sensible for an address book to have some address book like layout options, or business-card like displays, but please drop the phoney leather and wood surrounds, Apple.

At the top of this piece is an illustration of another example of this concept. Apple's relatively new podcast app for the iPhone has a design based on a reel-to-reel tape player. This one I have mixed feelings about. At least it is tech, if old tech - so it's not quite so painful. In fact I find it quite sweet. But I don't think anyone can defend faux leather and wood. Get a grip, guys!

Apple's skeuomorphic podcast app

Apple's skeuomorphic podcast appThere are some aspects of skeuomorphism few would question. Functional skeuomorphism is why spreadsheets look like sheets of lined paper accountants used to use, why a word processor is a bit like typing on a piece of paper, or why a button in a computer interface looks like - well - a button.

However the aspect that is causing some concern is a tendency to go beyond function to appearance for appearance sake. This can be a good thing - some kinds of decorative skeuomorphism work well with a computer. So, for instance, brushed aluminium goes well with an iMac. But the problem is with decorative appearance based on non-tech stuff like leather bindings on the address book and calendar, and wooden bookshelves. This can look just naff.

This isn't a new problem. I had a US made tape player and games console in the 1970s both of which had plastic fake wood finish - it looked terrible, and I could never understand why they did it, but I assume it appealed to the US consumer.

I think if Apple is sensible they will listen to the growing groundswell against this retro skeuomorphism and at the very least give the option of switching it off. After all, I even saw an article the other day that suggested that Microsoft now has better taste than Apple - surely a call to arms.

I think it's very sensible for an address book to have some address book like layout options, or business-card like displays, but please drop the phoney leather and wood surrounds, Apple.

At the top of this piece is an illustration of another example of this concept. Apple's relatively new podcast app for the iPhone has a design based on a reel-to-reel tape player. This one I have mixed feelings about. At least it is tech, if old tech - so it's not quite so painful. In fact I find it quite sweet. But I don't think anyone can defend faux leather and wood. Get a grip, guys!

Published on July 22, 2012 23:42

July 21, 2012

Universe Inside You on offer

Sorry, not really a post, more a shriek of excitement, but I had to mention that the Universe Inside You is on the same 24 hour Kindle offer that took Inflight Science up with the likes of 50 Shades of Grey.

Sorry, not really a post, more a shriek of excitement, but I had to mention that the Universe Inside You is on the same 24 hour Kindle offer that took Inflight Science up with the likes of 50 Shades of Grey.Today (Saturday 21 June) it's 99p from the UK Kindle store and $1.54 from the US Kindle store.

When I last looked was #63 on the paid Kindle list: hope to get it all the way! Please spread the word...

Here's a bit about it:

Built from the debris of exploding stars that floated through space for billions of years, home to a zoo of tiny aliens, and controlled by a brain with more possible connections than there are atoms in the universe, the human body is the most incredible thing in existence.

In the sequel to his bestselling Inflight Science, Brian explores mitochondria, in-cell powerhouses which are thought to have once been separate creatures; how your eyes are quantum traps, consuming photons of light from the night sky that have travelled for millions of years; your many senses, which include the ability to detect warps in space and time, and why meeting an attractive person can turn you into a gibbering idiot. Find out more at the book’s website.

Bursting with eye-popping facts and the latest mind-bending theories, the book takes you on journey through the mind-boggling science of the human body:

Every atom in your body was either produced in the Big Bang 13.7 billion years ago or made in a star between seven and twelve billion years ago

Your body contains around 10 times as many bacterial cells as it does human cells

When you make a decision to do something your brain fires up about 1/3 of a second before you are consciously aware of making the decision.

Published on July 21, 2012 03:11

July 19, 2012

The Baywatch principle

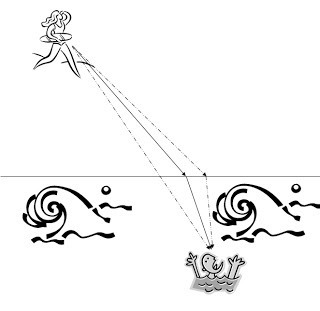

Science isn't always great at naming things. For every photon there are plenty of clunky names that don't do a lot for you. Take, for instance, the 'principle of least action', which sounds like a description of the lives of teenagers. This is a shame because it is really interesting. For reasons that will become clear I like to think of it as 'the Baywatch Principle.' And what it says, in essence, is that nature is lazy.

Science isn't always great at naming things. For every photon there are plenty of clunky names that don't do a lot for you. Take, for instance, the 'principle of least action', which sounds like a description of the lives of teenagers. This is a shame because it is really interesting. For reasons that will become clear I like to think of it as 'the Baywatch Principle.' And what it says, in essence, is that nature is lazy.French mathematician Pierre de Fermat used the principle of least action to explain why light bends as it moves from a thinner to a thicker substance (from air to glass, for instance) – and Richard Feynman made it a fundamental part of quantum electrodynamics.

The principle of least action describes why a basketball follows a particular route through space on its way to the basket. It rises and falls along the path that keeps the difference between the ball’s kinetic energy (the energy that makes it move) and potential energy (the energy that gravity gives it by pulling it downwards) to a minimum. Kinetic energy increases as the ball goes faster and decreases as it slows. Potential energy goes up as the ball gets higher in the air and reduces as it falls. The principle of least action establishes a balance between the two.

This principle is applied to light by considering time. The principle of least time says that light takes the quickest route. Fermat had to make two assumptions – that light’s speed isn’t infinite (the speed of light was yet to be measured in 1661 when Fermat produced this result), and that light moves slower in a dense material like glass than it does in air. We are used to straight lines being the quickest route between any two points – but that assumes that everything remains the same on the journey. In the case of light going from air to glass, bending is the quickest route. To see why this is the case, compare the light’s journey to a lifeguard, rescuing someone drowning in the sea. The obvious route is to head straight for the drowning person. But the lifeguard can run much faster on the beach than in the water. By heading away from the victim, taking a longer path on the sand, then bending inwards and taking a more direct path in the water, the lifeguard gets there quicker.

Similarly, a light ray can reduce its journey time by spending longer in air and less time in glass. The angle that minimizes the journey time is the one that actually occurs.

When Richard Feynman was inspired by the principle of least action to come up with quantum electrodynamics, the theory that describes the interaction of light and matter so brilliantly, he imagined not just the one “best” path but every single possible path a particle could take in getting from A to B. At the heart of QED is the idea that you can identify the particles behaviour by taking a sum of every single possible path combined with the probability of that path occurring.

Published on July 19, 2012 22:54

I blame Dawkins

The recent furore (well, furore in teacup) over Free Schools teaching creationism has made me quite angry. We have seen the creationist/intelligent design lobby in the US over the years use all sorts of dirty tricks to try to sneak creationist pseudo-science onto the agenda. But now those opposing religion, specifically the British Humanist Association, but also plenty of others who should know better, are resorting to their own dirty tricks, and it's not good enough.

The recent furore (well, furore in teacup) over Free Schools teaching creationism has made me quite angry. We have seen the creationist/intelligent design lobby in the US over the years use all sorts of dirty tricks to try to sneak creationist pseudo-science onto the agenda. But now those opposing religion, specifically the British Humanist Association, but also plenty of others who should know better, are resorting to their own dirty tricks, and it's not good enough.If you want to make your point by using good reasoned argument, you mustn't cheat or you will be ignored when the truth comes out.

The problem I have is this. There is every good reason to oppose creationism, which in its most extreme ('young Earth') form says God made the Earth, essentially as it is now, 6,000 years ago, and in its watered down ('old Earth') form says God made the Earth as it says in Genesis in the Bible, but over a longer timescale. Creationism is biblical literalism.

However the majority of believing Christians (and basically this is an attack on Christianity, let's not pretend otherwise) in the UK are neither creationists nor literalists. They believe in a creator God but believe that said God used the mechanisms that science thinks are responsible for things being the way they are, whether it's quantum theory and the standard model or evolution.

All this sound and fury is because certain factions are conflating creationism and a Christian belief in God, which are simply not the same thing. I don't think they are doing this accidentally - this appears to be a deliberate attempt to mislead. They are trying to make 'creationism' just another word for 'Christian' and I object, if only as a writer to this misuse. It would be ridiculous to say that, for instance, a CofE school in its assemblies or RE lessons could not teach about a creator God - that's thought police territory. Such a school shouldn't be able to teach creationism as science - and they aren't allowed to - but the two things are totally separate.

Of course there is a different issue of whether we ought to allow religious schools at all - I don't think we should - but that debate is quite different from this one. While they exist they have the right to do what the law says they can do.

I'm afraid I really do blame Richard Dawkins and his cohorts of muscular atheists who never seem to let their bad effect on the general public's opinion of science get in the way of really irritating people. This is anti-religious bigotry pure and simple.

Bah.

Published on July 19, 2012 00:47

July 17, 2012

I'm repressing my memory of Freud

I've been reading a lot on psychology recently for a book I'm writing and was fascinated to discover just how much doubt there is about the whole business of suppressed memories.

I've been reading a lot on psychology recently for a book I'm writing and was fascinated to discover just how much doubt there is about the whole business of suppressed memories.The idea that we can find memories so horrible that somehow the brain will edit them out has no scientific basis in origin, coming from the work of Freud and his ilk, who simply made things up as they went along. Freud's work has largely been removed from the the scientific viewpoint, but the idea of repressed memories got left behind. It's time we forgot it.

To make matters worse, we now know that processes like hypnosis are quite good at implanting fake memories. So when a 'therapist' tries to regress someone to get to memories that have been suppressed - of child abuse, say, or alien abduction - instead of getting to hidden memories what they are doing is constructing new ones. There are fascinating experiments where by simply being told a convincing story repeatedly even individuals who are not hypnotised can begin to incorporate these stories (a typical one is about getting lost in a shopping mall as a child) into their memories and treat them as 100 per cent real.

Even when an individual originally claims to have no memory of traumatic event that was known to have happen, all the evidence is that they are consciously failing to report it, because they find it embarrassing or don't want to be disloyal to someone else, not because their brain had decided to lock the memory away.

So please, fiction writers, stop making use of repressed memories - they are even less likely than that creaky old favourite of soap operas, amnesia. At least there are good examples of that happening, but not of repressed memories. It's as much the invention of the imagination of unscientific analysts as were Freud's lurid interpretations of dreams.

Published on July 17, 2012 23:53

It's time companies got the hang of networking

I've mentioned before the powerful aspects of networking as identified very clearly in the interesting book Wikinomics (see details at Amazon.co.uk or at Amazon.com) - unfortunately it's something many companies haven't got a clue about.

I've mentioned before the powerful aspects of networking as identified very clearly in the interesting book Wikinomics (see details at Amazon.co.uk or at Amazon.com) - unfortunately it's something many companies haven't got a clue about.I was just rapidly emptying my inbox of commercial newsletters, which I have a habit of accumulating in the hope of winning a year's supply of electric bananas or some such essential, when it struck me how many of them came from that strangely named person 'donotreply' AKA 'noreply' AKA 'dontreply'.

Even the rather witty weekly roundup from the IT intelligence site Silicon.com comes from a non-human sounding address silicon@newsletters.silicon.cneteu.net that it seems highly likely won't get you anywhere if you send an email to it.

These companies who employ 'noreply' are, frankly, dumb. Organizations spend a vast amount of money on building a relationship with customers - yet the very moment a customer wants to talk to them, they say 'we aren't interested in what you have to say: it's only what we say that's important.' Isn't it time they sacked noreply and replaced her with her cousin pleasereply, and waited for the conversation to begin?

This post first appeared on my Nature Network blog - I'm bringing some of the old posts over to my new home, as the NN blog is liable to disappear soon.

Published on July 17, 2012 00:07

July 16, 2012

Nature's Nanotech

This is the first of a series of features on www.popularscience.co.uk that I will also be featuring on my blog:

When we think of nanotechnology, it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that we are dealing with the ultimate in artificial manufacturing, the diametric opposite of something that’s natural. Yet in practice, nature is built on nanotechnology. From the day-to-day workings of the components of every single biological cell to the subtle optics of a peacock feather, what we see is nanotechnology at work.

Not only are the very building blocks of nature nanoscale, but natural nanotechnology is a magnificent inspiration for ways to make use of the microscopic to change our lives and environment for the better. By studying how very small things work in the natural world we can invent remarkable new products – and this feature is the first in a series that will explore just how much we can learn and gain from nature’s nano tech.

As I described in The Nanotechnology Myth the term ‘nanotechnology’ originates from the prefix nano- which is simply a billionth. Nanotechnology makes use of objects on the scale of a few nanometres, where a nanometre is a millionth of a millimetre. For comparison, a human hair is around 50,000 nanometres across. Nanotechnology encompasses objects that vary in size from a large molecule to a virus. A bacterium, typically around 1,000 nanometres in size, is around the upper limit of nanoscale items.

A first essential is to understand that although nanotechnology, like chemistry, is involved in the interaction of very small components of matter, it is entirely different from a chemical reaction. Chemistry is about the way those components join together and break apart. Nanotechnology is primarily about their physics – how the components interact. If we think of the analogy of making a bicycle, the ‘chemistry’ of the bicycle is how the individual components bolt together, the ‘nanotechnology’ is how, for example, the gear interacts with the chain or pushing the pedals makes the bike go.

This distinction is necessary to get over the concern some people raise about nature and nanotechnology. A while ago, when I wrote my book on environmental truth and lies, Ecologic , I had a strange argument with a representative of the Soil Association, the UK’s primary organic body. In 2008 the Soil Association banned nanoparticles from their products. But it only banned man-made nanoparticles, claiming that natural ones, like soot, are fine ‘because life has evolved with these.’

This is a total misunderstanding of the science. If there are any issues with nanotechnology they are about the physics, not the chemistry of the substance – and there is no sensible physical distinction between a natural nanoparticle and an artificial one. In the case of the Soil Association, the reasoning was revealed when they admitted that they take ‘a principles-based regulatory approach, rather than a case-by-case approach based on scientific information.’ In other words their opposition was a knee-jerk one to words like ‘natural’ and ‘artificial’ rather than based on substance.

Of themselves, like anything else, nanoparticles and nanotechnology in general can be used for bad or for good. Whether natural or artificial they have benefits and disadvantages. A virus, for example, is a purely natural nanotechnology that can be devastatingly destructive to living things. And as we will see, there are plenty of artificial nanotechnologies that bring huge benefits.

In nature, nanotechnology is constructed from large molecules. A molecule is nothing more than a collection of atoms, bonded together to form a structure, which can be as simple as a sodium chloride molecule – one atom each of the elements sodium and chlorine – or as complex as the dual helix of DNA. We don’t always appreciate how significant individual molecules are.

I had a good example of this a few days ago when I helped judge a competition run by the University of the West of England for school teams producing science videos. The topic they were given was the human genome – and the result was a set of very varied videos, some showing a surprising amount of talent. At the awards event I was giving a quick talk to the participants, looking at the essentials of a good science video. I pointed out that they had used a lot of jargon without explaining it – a common enough fault even in mainstream TV science.

Just to highlight this, I picked out a term most of them had used, but none had explained – chromosomes. What, I asked them was a chromosome? They told me what it did, but didn’t know what it was, except that it was a chunk of DNA and each human had 46 of them in most of their cells. This is true, but misses the big point. A chromosome is simply a single molecule of DNA. Nothing more, nothing less. One molecule.

Admittedly a chromosome is a very large molecule. Human chromosome 1 is the biggest molecule we know of, with around 10 billion atoms. Makes salt look a bit feeble. But it is still a molecule. The basic components of the biological mechanisms of everything living, up to an including human beings are molecules. Chromosomes provide one example, effectively information storage molecules with genes as chunks of information strung along a strip of DNA. Then there are proteins, the workhorses of the body. There are neurotransmitters and enzymes, and a whole host of molecules that are the equivalent of gears to the body’s magnificent clockwork. These are the building blocks of natural nanotechnology.

So with a picture of what we’re dealing with we can set out to see nature’s nanotech in action and the first example, in the next feature in this series, will show how nanotechnology on the surface of a leaf has inspired both self-cleaning glass and water resistant trainers.

When we think of nanotechnology, it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that we are dealing with the ultimate in artificial manufacturing, the diametric opposite of something that’s natural. Yet in practice, nature is built on nanotechnology. From the day-to-day workings of the components of every single biological cell to the subtle optics of a peacock feather, what we see is nanotechnology at work.

Not only are the very building blocks of nature nanoscale, but natural nanotechnology is a magnificent inspiration for ways to make use of the microscopic to change our lives and environment for the better. By studying how very small things work in the natural world we can invent remarkable new products – and this feature is the first in a series that will explore just how much we can learn and gain from nature’s nano tech.

As I described in The Nanotechnology Myth the term ‘nanotechnology’ originates from the prefix nano- which is simply a billionth. Nanotechnology makes use of objects on the scale of a few nanometres, where a nanometre is a millionth of a millimetre. For comparison, a human hair is around 50,000 nanometres across. Nanotechnology encompasses objects that vary in size from a large molecule to a virus. A bacterium, typically around 1,000 nanometres in size, is around the upper limit of nanoscale items.

A first essential is to understand that although nanotechnology, like chemistry, is involved in the interaction of very small components of matter, it is entirely different from a chemical reaction. Chemistry is about the way those components join together and break apart. Nanotechnology is primarily about their physics – how the components interact. If we think of the analogy of making a bicycle, the ‘chemistry’ of the bicycle is how the individual components bolt together, the ‘nanotechnology’ is how, for example, the gear interacts with the chain or pushing the pedals makes the bike go.

This distinction is necessary to get over the concern some people raise about nature and nanotechnology. A while ago, when I wrote my book on environmental truth and lies, Ecologic , I had a strange argument with a representative of the Soil Association, the UK’s primary organic body. In 2008 the Soil Association banned nanoparticles from their products. But it only banned man-made nanoparticles, claiming that natural ones, like soot, are fine ‘because life has evolved with these.’

This is a total misunderstanding of the science. If there are any issues with nanotechnology they are about the physics, not the chemistry of the substance – and there is no sensible physical distinction between a natural nanoparticle and an artificial one. In the case of the Soil Association, the reasoning was revealed when they admitted that they take ‘a principles-based regulatory approach, rather than a case-by-case approach based on scientific information.’ In other words their opposition was a knee-jerk one to words like ‘natural’ and ‘artificial’ rather than based on substance.

Of themselves, like anything else, nanoparticles and nanotechnology in general can be used for bad or for good. Whether natural or artificial they have benefits and disadvantages. A virus, for example, is a purely natural nanotechnology that can be devastatingly destructive to living things. And as we will see, there are plenty of artificial nanotechnologies that bring huge benefits.

In nature, nanotechnology is constructed from large molecules. A molecule is nothing more than a collection of atoms, bonded together to form a structure, which can be as simple as a sodium chloride molecule – one atom each of the elements sodium and chlorine – or as complex as the dual helix of DNA. We don’t always appreciate how significant individual molecules are.

I had a good example of this a few days ago when I helped judge a competition run by the University of the West of England for school teams producing science videos. The topic they were given was the human genome – and the result was a set of very varied videos, some showing a surprising amount of talent. At the awards event I was giving a quick talk to the participants, looking at the essentials of a good science video. I pointed out that they had used a lot of jargon without explaining it – a common enough fault even in mainstream TV science.

Just to highlight this, I picked out a term most of them had used, but none had explained – chromosomes. What, I asked them was a chromosome? They told me what it did, but didn’t know what it was, except that it was a chunk of DNA and each human had 46 of them in most of their cells. This is true, but misses the big point. A chromosome is simply a single molecule of DNA. Nothing more, nothing less. One molecule.

Admittedly a chromosome is a very large molecule. Human chromosome 1 is the biggest molecule we know of, with around 10 billion atoms. Makes salt look a bit feeble. But it is still a molecule. The basic components of the biological mechanisms of everything living, up to an including human beings are molecules. Chromosomes provide one example, effectively information storage molecules with genes as chunks of information strung along a strip of DNA. Then there are proteins, the workhorses of the body. There are neurotransmitters and enzymes, and a whole host of molecules that are the equivalent of gears to the body’s magnificent clockwork. These are the building blocks of natural nanotechnology.

So with a picture of what we’re dealing with we can set out to see nature’s nanotech in action and the first example, in the next feature in this series, will show how nanotechnology on the surface of a leaf has inspired both self-cleaning glass and water resistant trainers.

Published on July 16, 2012 05:40

July 13, 2012

It's got to be brown

A while ago I eulogised on the subject of barbecue sauce. I admit I am practically an addict - yet I ought also to recognise an older allegiance that is still there. Because I am also very fond of brown sauce.

A while ago I eulogised on the subject of barbecue sauce. I admit I am practically an addict - yet I ought also to recognise an older allegiance that is still there. Because I am also very fond of brown sauce.This is something that could only be invented (or at least named) in the UK. In France it would be (and is) sauce picante. In the US it would be super-tangy fruitified meat sauce or something. But here it's brown sauce. Brown. Plodding. Tells you nothing but the colour, nothing of the delights that lie within.

For me there is nothing better (sorry barbecue, but you don't cut the mustard) to go with, say, a sausage or a pie. I confess (though this is a personal oddity) I have it with fish and chips. But the ultimate has to be as an accompaniment to a cooked breakfast or a bacon sandwich. Those who go for ketchup in these circumstances totally miss the plot.

So essential is it to have this accompaniment that even those bastions of US imperialism McDonalds and Starbucks provide brown sauce with their breakfast rolls, wraps and paninis.

Rather like cola, while there are many clones and copies there are only two serious contenders for the brown sauce crown. I have to dismiss immediately Worcester(shire) sauce. This is a great cooking ingredient but it totally fails as an accompaniment to breakfast. When I lived with my parents we were a Daddies sauce family, but my grandparents went with HP sauce. I'd say Daddies is the Pepsi of brown sauces to HP's Coca Cola. HP is the original, the leader of the pack, and is more subtle than Daddies - a little less fruity, a bit more spicy. When I was a child I had my parents' brown sauce. When I became a man I put aside childish things and converted to HP. After all, how British can a sauce be? It's Houses of Parliament sauce, for goodness sake.

So, if you've never tried it, put off by the name and the look of it - be brave. If used correctly it is nectar of the gods.

Published on July 13, 2012 01:34