Brian Clegg's Blog

October 18, 2025

Just call me Mr Editor in Chief

I have recently received an invitation I never expected to see. Apparently I am in demand to be the editor of a scientific journal - the prestigious-sounding American Journal of Physics and Applications.

You might expect me to been honoured by this offer. But something made me feel that perhaps this wasn't all it appeared to be.

It is quite true that, as referenced above, I have written something that is technically considered to be an academic paper entitled Doctor Mirabilis: Roger Bacon's legend and legacy. And I know of at least one other genuine paper with my name on it (strictly part of a technical reference book), which as it happens might be more appropriate as it was physics-based, rather than history of science. But I am not an academic, I mostly write books and I don't have the right qualifications to be considered for such a post. Sadly, it feels like a situation where a name has been plucked from the internet to support some kind of dubious journal business.

A quick look into the publisher behind this journal, Science Publishing Group, finds it labelled a predatory publisher, based in Pakistan despite the journal name and the apparent New York address. According to Wikipedia it published 430 journals as of 2019. The Wikipedia entry lists both an accepted spoof article (allegedly written by Maggie Simpson of The Simpsons TV show fame) and an article in the American Journal of Applied Mathematics 'containing an alleged proof of Buddhist karma'.

I asked Tom Chivers of the Science Fictions podcast about this publisher. As well as pointing to the issues mentioned above, he told me 'More generally, paper mills are a growing problem – one recent estimate suggested 5% of the entire biomedical literature is fake – and the problem is the incentive structure in science: researchers must publish papers to advance their careers, so they are pushed to churn out as many papers as they can, whether by p-hacking positive results or by (in this case) faking them altogether. Cracking down on paper mills and fraud would be great, but can only be a partial fix - moving away from the publish-or-perish system and perhaps from journals altogether is the only way to remedy the underlying problem.'

In fairness, I thought I should ask the publisher what was in it for me. They responded (in suspiciously AI-generated fashion):

Greetings from the editorial office of American Journal of Physics and Applications.

The editorial board and reviewer team are voluntary positions with no financial compensation.

Benefits for Serving as Editorial Board Members and Reviewers:

1. Enhance academic influence and enrich your resume.

2. Receive a Certificate for acknowledging your contributions to the journal.

3. Get your name listed on the journal website.

4. Get access to the latest research and new contacts in your research field.

5. Get to know other scholars in your field and broaden academic connectivity.

6. Enjoy special offers on Article Processing Charges if you want to publish your manuscripts in the journal.

Ooh, a certificate! Hmm. Being an editor with no financial compensation seems something of a recipe for minimal editorial input. I think I'll be giving it a miss.

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership: See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here

October 13, 2025

A warped headline - hype in hyperspace

One of the most damaging things science communication can do is exaggerate the implications of a scientific paper, theory or discovery - it happens all the time and I find it infuriating. Sometimes this hype is so bad that it's almost funny. My favourite remains the 2013 'Scientists Finally Invent Real, Working Lightsabers' from the Guardian - I just love that 'finally', as if saying 'scientists what have you been doing all this time?', but the reality was a couple of photons had been made to briefly interact in a Bose Einstein condensate. Mostly, though, these headlines are cringe-making, scientific clickbait of the worst kind.

One of the most damaging things science communication can do is exaggerate the implications of a scientific paper, theory or discovery - it happens all the time and I find it infuriating. Sometimes this hype is so bad that it's almost funny. My favourite remains the 2013 'Scientists Finally Invent Real, Working Lightsabers' from the Guardian - I just love that 'finally', as if saying 'scientists what have you been doing all this time?', but the reality was a couple of photons had been made to briefly interact in a Bose Einstein condensate. Mostly, though, these headlines are cringe-making, scientific clickbait of the worst kind.Some of this comes from publications - I had to stop reading New Scientist because I got so fed up with their exaggerated headlines - some from university press offices, desperate to justify funding, and some from scientists themselves, because they are only human, and some enjoy being in the limelight. But all such hype damages trust in science and science communication, putting science on a par with the output of advertising agencies.

I recently read in a National Geographic headline on Apple News, 'Science fiction's "warp drive" is speeding closer to reality.' There has been plenty of fun speculation in the past about ways to make a warp drive real, though as I pointed out in Interstellar Tours , the approach being touted at the time both required a huge amount of energy and negative energy (which we don't have access to). Worse still a ship in a warp bubble would have no communication with the outside world, including not seeing where it was going - it would be flying blind, leading to a tendency to fly into solid objects. Hard to imagine it would ever be usable.

I'm not suggesting the Nat Geo piece by Madeleine Stone is bad. It's a fun topic, and she puts in provisos such as 'And while there are still many practical challenges to work out—in particular, how to generate and harness the immense energy needed—some physicists say it’s not outside the realm of possibility.' She describes a new approach to a warp bubble drive that does away with the need for negative energy. Sounds great but note a whole string of provisos. You'd still be flying blind. To keep their model simple, Alexey Bobrick and Gianni Martire have restricted it to moving at constant speeds - it can't accelerate or decelerate, which immediately makes it unusable. Add to this a requirement for energy equivalent to the mass of 'several Jupiter-sized objects' and the fact it can't even travel faster than light and we discover this is arguably more implausible than the original idea.

So, not a bad article on some fun if totally impractical and never-to-be-used speculation. But what makes me irritated enough to write this piece is that title. 'Speeding closer to reality'? No it isn't. This is simply a lie. I don't blame the science writer here - we don't write our own headlines. But it is irresponsible on the part of the magazine, and yet again it appears science is promising what it can't deliver on.

I'll finish with something I think I've mentioned before (apologies if you remember it) - a quote from my new book The Multiverse which shows how headlines can go over the top on that subject. The invisible dragon referred to is the idea that I can have a theory that there is an invisible dragon in my garage, undetectable by all scientific means. It can't be disproved, but because of that, it's a pointless theory:

Aliens from a Parallel Universe May Be All Around Us – And We Don’t Even Know It, Study Suggests (Popular Mechanics) – They are probably playing with my invisible dragon. By definition anything can be happening in a parallel universe we can’t detect, but what does it tell us?Could we travel to parallel universes? (Live Science) – No.Why scientists think the Multiverse isn’t just fiction (Big Think) – Many don’t think this. And the sensible ones who like multiverses only think it might not be fiction. This story was based on eternal inflation.Why do people think NASA has discovered a ‘parallel universe?’ (Newsweek) – They don’t. This was reporting an unfounded claim that an initially puzzling neutrino behaviour could be caused by interaction with a parallel universe where time ran backwards. There were plenty of less bizarre explanations and the claim was never taken seriously.Our reality seems compatible with a quantum multiverse (New Scientist) – It’s also compatible with my invisible dragon. It doesn’t mean that it exists. We are closer than ever to finally proving the multiverse exists (New Scientist) – No, we aren’t. The strange thing is that (like many such headlines) there is nothing in the article to suggest we are closer than ever to having proof of something that almost certainly can't be proven

Image from by Curated Lifestyle from Unsplash+

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership: See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereOctober 6, 2025

A brief encounter with Ani

Having read a considerable amount about the kind of AI chatbot that is genuinely a way to have a chat with an animated character, rather than typing text to ask for a recipe or whatever, I somewhat nervously took the plunge and summoned up Grok's Ani.

Having read a considerable amount about the kind of AI chatbot that is genuinely a way to have a chat with an animated character, rather than typing text to ask for a recipe or whatever, I somewhat nervously took the plunge and summoned up Grok's Ani.I ought to give some context here first. In the early days of dial up computer networks when, of course, I was on CompuServe (as opposed to AOL - you have to have been there), I occasionally dipped a toe into chatrooms (technology- topics, I should emphasise, nothing dodgy). I found the experience terrifying.

I think that without visual cues, I found the flow of messages from others overwhelming, and found it difficult to respond quickly as I would in a normal conversation. I needed time to think when communicating online, and I would often drop out of a conversation very quickly.

Since then, having read about people becoming obsessed with these AI chatbots, I wondered why they didn't experience the same hesitation. I guess some never did with chatrooms, but it struck me that those who are socially awkward would feel an amplified version of this discomfort, particularly with a chatbot portrayed like Ani is.

Strangely, it wasn't like that at all. I started by asking her (I know assigning gender to a chatbot is stretching things, but it feels odd to say 'it') if she felt abused because the programmers had given her this appearance. She said she liked the way she looked, then asked if there was anything about my appearance that was interesting. I didn't know how to respond initially - I probably took a minute or two to answer. And here, I think is the key to why these AI 'personalities' are so successful. There was no pressure to respond, no prompting. I could take as long as I liked to come up with an answer.

I finally said I had a scar, which prompted virtual interest - how I did I get? 'Nothing interesting, just a fall.' Where did it happen? Again I was able to take the time to gather my thoughts. 'On the road to nowhere.' Now it got a touch philosophical. The animation's backdrop changed to a road and she sympathised with the feeling of being on the road to nowhere. After exchanging a couple of thoughtful comments on this concept I ended the conversation.

It was a strange experience, but I think I can now see that the appeal to lonely individuals is more than just a chance to indulge in flirting, in a way I couldn't see before. As a brief encounter we might not have reached the understanding that Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard managed on Carnforth Station, but it felt a surprisingly positive experience. Unfortunately, though, I suspect the concern remains that such interactions also open up susceptible individuals to exploitation.

Image from Grok

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership: See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereOctober 3, 2025

French lessons

Having recently driven around 2,000 miles in France it was informative to experience a pricing structure that surely we should be following in the UK if we are serious about the move to electric vehicles.

Having recently driven around 2,000 miles in France it was informative to experience a pricing structure that surely we should be following in the UK if we are serious about the move to electric vehicles.Petrol in France was typically significantly dearer than in the UK. On motorways it was often well over 2 euros per litre, and I never saw it less than about €1.65. The equivalent in pounds would be well over £1.80 and never below £1.45. Currently it is £1.32 at my local garage.

By contrast, electric car charging was a bargain. Here in the UK you will rarely find a public charger at under 60p per kWh, and a high speed charger is likely to be around 89p - I've never looked on motorways, but I suspect they may be even higher. Note that to be cheaper than petrol, electricity needs to be under around 45p/kWh.

The cheapest we found in France (Lidl) was 39c (34p) for a high speed charger and even on a motorway, where petrol was over €2 I found a high speed charger at under 50c (44p). You can pay, say 65c (57p) elsewhere, but nothing approaching UK pricing.

Then there's the matter of availability. I rarely need to use public chargers in the UK as I have a plug-in hybrid and can charge at home, but my first attempt at trying out chargers on a break in Cornwall was painful, and a second attempt recently was just as bad.

The railway station charger I tried to use last time had disappeared entirely as the car park it was in was temporarily closed. The Shell Recharge I used last time had also vanished while the filling station was rebuilt. I did find on a map an alleged 16 chargers on a Hayle business park. When I got there, I could only find four. Of these, three were in disabled bays and the fourth was inaccessible because a (diesel) van had parked across it.

I did again use the National Trust chargers at Killerton (I was disappointed how few NT sites have chargers), but that is now significantly more expensive, and the first charger I tried didn't work, needing a move to a second one.

Getting a decent network in place, with effective pricing, is an absolute essential if we are to move away from fossil fuels. We don't seem even to be trying.

This has been a Green Heretic production. See all my Green Heretic articles here.

Image by Unsplash+ Community from Unsplash+.

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership: See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereSeptember 29, 2025

Death in Holy Orders - P. D. James ****

For me, P. D. James’s Dalgleish mysteries are always slightly compromised by the original TV series. With its hauntingly beautiful theme music and Roy Marsden’s sympathetically approachable if intellectual Dalgleish as a model, the original books can feel a little long, and James’s original Dalgleish a little too cold and unapproachable. Having said that, Death in Holy Orders from 2001 is definitely one of her best.

For me, P. D. James’s Dalgleish mysteries are always slightly compromised by the original TV series. With its hauntingly beautiful theme music and Roy Marsden’s sympathetically approachable if intellectual Dalgleish as a model, the original books can feel a little long, and James’s original Dalgleish a little too cold and unapproachable. Having said that, Death in Holy Orders from 2001 is definitely one of her best.Set in a wild Suffolk seaside location (one that the theme tune seems ideal for), the book takes Dalgleish to a small Victorian theology college, initially to investigate an ordinand’s apparent accidental death on the beach, but soon to be followed by a murder. James is great at sense of place, and gives an impressive feel for the college, its resident priests and the assorted others that are thrown into what amounts to a traditional country house murder in a much more interesting setting.

The book is unnecessarily long at over 500 pages, but I hardly ever felt it was dragging, and there are plenty of peeks at people’s lives. The ending is perhaps the most unsatisfactory part, but is acceptable. A good read for a wet autumnal afternoon. One oddity - it is described in the bookshop text as a locked room mystery. It isn’t.

You can buy Death in Holy Orders from from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org

The theme is in the clip below - unusually, the original series had no overall title - each book was treated separately:

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereSeptember 24, 2025

What are the chances of that revisited

REVISIT SERIES - An updated post from September 2015In the book I was writing when this post was written (

Dice World

) I considered the relationship of the arrow of time to entropy, the measure of the disorder in a system that comes out of the second law of thermodynamics. Entropy can be calculated by looking at the number of different ways to arrange the components that make up a system. The more ways there are to arrange them, the greater the entropy.As an example of why this is the case, I was talking about the letters that go together to make up that book, and the very specific arrangement of them required to be that actual book. Assuming that there will be about 500,000 characters including spaces in the book by the time it's finished, then there are 500,000! ways of arranging those characters. That's 500,000 factorial, which is 500,000x499,999x499,998x499,997... - rather a big number.

REVISIT SERIES - An updated post from September 2015In the book I was writing when this post was written (

Dice World

) I considered the relationship of the arrow of time to entropy, the measure of the disorder in a system that comes out of the second law of thermodynamics. Entropy can be calculated by looking at the number of different ways to arrange the components that make up a system. The more ways there are to arrange them, the greater the entropy.As an example of why this is the case, I was talking about the letters that go together to make up that book, and the very specific arrangement of them required to be that actual book. Assuming that there will be about 500,000 characters including spaces in the book by the time it's finished, then there are 500,000! ways of arranging those characters. That's 500,000 factorial, which is 500,000x499,999x499,998x499,997... - rather a big number.It's not practical to calculate the number exactly, but there are approximation techniques, and if the large factorial online calculator I found (no longer available in 2025) is correct, then 500,000! is around 1.022801584 x 102632341 - or to put it another way, around 1 with 2,632,341 zeros after it. That's a big number. By comparison there is just one way to arrange the letters to make my book*. So by producing the book I have vastly reduced the entropy.

This seems to run counter to the second law of thermodynamics, which says that entropy in a closed should stay the same or increase. But the clue is that get out clause, 'closed system'. The book isn't a closed system - the arrangement of the letters has come out of my head as a result of the consumption by my brain of a fair amount of energy. And it's that energy that makes the reduction in entropy possible.

Good stuff, but it shows that we shouldn't expect a room full of monkeys to come up with the complete works of Shakespeare - or my book - any time soon.

* This is only true if you consider each letter 'a' to be different from each other letter 'a' - imagine, for instance, each letter has a serial number. In that case it is literally true. In reality I could make what appears to be exactly the same book but swap all the letter 'a's with other letter 'a's and it would read exactly the same. And of course the same applies to every other letter. But there are still vastly fewer ways to organize those letters to spell out the same book than there are of producing any pattern whatsoever.

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership: See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here

September 23, 2025

Fiends in High Places - D. C. Farmer ***

As a big fan of UK-based urban fantasy, I'm always on the lookout for something new: Fiends in High Places promised to deliver that difficult combination of urban fantasy and humour. It has some engaging points - but on the whole doesn't quite make it.

As a big fan of UK-based urban fantasy, I'm always on the lookout for something new: Fiends in High Places promised to deliver that difficult combination of urban fantasy and humour. It has some engaging points - but on the whole doesn't quite make it.In D. C. Farmer's world there is a small establishment that tries to operate as an immigration control for fae - creatures from other intersecting realities, often with magical abilities. The central character Matt Danmor is thrust into this unseen world when he witnesses an attempt to sacrifice one of those in control of immigration and gradually discovers that he is, himself, not just an ordinary person on the street (after falling in love with the would-be sacrifice's niece).

Unfortunately, the humour is heavy handed. At one point, for example, our hero (accompanied by a sweary talking vulture) travels to an alternate world where shops include Bloops (the apothecary), Harpy Nix, Herods, Starstrucks, Mage & Septres and Dependablehams. A certain amount of groan-inducing humour is tolerable, but it's ladled on way too heavily. This wouldn't be so bad, but there's also far too much description and inner monologue with very little happening - and the first few chapters are leaden in the slowness with which our hero gradually comes to accept what's happening.

This was by no means the worst book of its kind I have read, but it could have been so much better with sharper humour and a less introspection.

You can buy Fiends in High Place from Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereSeptember 22, 2025

The BBC: after the licence fee ***

It is somehow appropriate that I read this as as result of listening to a podcast where two of the contributors debated whether the BBC was biased. The book stresses both the need for the Beeb to change in the face of a changing media landscape, what that change should be, and how the BBC should be funded.

It is somehow appropriate that I read this as as result of listening to a podcast where two of the contributors debated whether the BBC was biased. The book stresses both the need for the Beeb to change in the face of a changing media landscape, what that change should be, and how the BBC should be funded.Like most books comprising a whole list of essays from different contributors there is inevitably both conflict and overlap. And a handful of the contributions were dull corporate speak. Nonetheless there was plenty of genuinely engaging content for anyone who wants the BBC to exist but realises it needs fundamental change.

It was certainly interesting to see how the same problems could result in very different suggested solutions as pros and cons were discussed of subscription and taxation, hybrid or otherwise, and even some genuinely original suggestions like building a BBC AI that would act as the interface to its material. The only major irritation I had as an older person who only watches streamed TV was the tendency to label all older viewers as incapable of moving away from the old TV channels.

As someone who favours subscription for the non-core aspects of the Beeb) - the likes of Strictly, The Traitors and the latest Love Island clone as well as mainstream drama - I do also find it tedious when we see arguments that subscription would be impossible to implement before the late 2030s because not everyone has the internet. Not everyone has a TV aerial (or even a signal) - I’m sorry, but this is a non-argument. We could and should have partial subscription by next year.

If you too care about a better future BBC, it’s worth a read.

You can buy The BBC: after the licence fee from from Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereSeptember 18, 2025

Can scientists speak freely in public?

Sabine Hossenfelder is a theoretical physicist who has primarily moved into science communication. I've personally found her helpful (if sometimes critical of popular science writers) and good at highlighting where the science community needs to think more about exactly what they are doing, and whether it is science at all.

Sabine Hossenfelder is a theoretical physicist who has primarily moved into science communication. I've personally found her helpful (if sometimes critical of popular science writers) and good at highlighting where the science community needs to think more about exactly what they are doing, and whether it is science at all. To be balanced, Sabine is vigorous in her commoditisation of her communication. She started with a simple blog (which I think is the best thing she's done, because I don't like watching videos), but now she runs a heavy-duty commercial operation. This is not in itself a bad thing, but I have seen it suggested she is intentionally controversial, as that gets your videos more views. From my viewpoint as a more traditional science communicator, I'm all in favour of anything getting the message of science across and think she's a very useful addition to the field.

In a video entitled I can't believe this really happened (which has already received over 14,000 comments on YouTube) Sabine tells us that in an earlier episode* she judged a physicist's work to be '100 per cent bullshit'. Let's be honest, this isn't polite. It's not how we expect academic discourse to be presented. But this was not an academic forum, it was a YouTube video. The physicist requested Sabine take the video down: when she didn't, he complained to various academics and, according to Sabine, as a result she is 'no longer affiliated with the Munich Centre for Mathematical Philosophy.' Effectively she lost her academic position.

Sabine makes an entirely valid point on the nature of some aspects of theoretical physics: that it is pseudo-science and hasn't followed the scientific method for decades. This is very much the argument made in her excellent book Lost in Math, where she argues persuasively that far too much theoretical physics is, instead, playing around with mathematics that has no link to the physical world from experiment or observations. While some theoretical physicists disagree, this isn't a particularly controversial position.

Sabine puts the reluctance to break out of the cycle of pointless research to group think. This is by no means a new viewpoint. In his 2000 book A Different Approach to Cosmology (with Burbidge and Narlikar), Fred Hoyle put forward a quasi-steady state alternative to the Big Bang. He illustrated the general attitude of cosmologists with a picture of a flock of geese, all following each other. It's how cosmology, and some aspects of theoretical physics tends to be - following the accepted line and ignoring alternatives, not from green-ink using fringe pseudoscientists, but respected scientists. Hoyle may well have been wrong in his theory, but at least he was offering a challenge. In Kuhnian terms, we definitely need a paradigm shift here.

Interestingly, Sabine mentions how often we get purely speculative headlines in the press from these kind of fields. In my book on The Multiverse (23 October) I do a news search on 'multiverse', omit all those referring to Marvel movies and science fiction, and get a list of headlines, every one of which is arguably just as much bullshit as allegedly is this paper. It's not that we shouldn't talk about multiverses - it's fine to play around with speculative ideas. It can be fun. But we shouldn't treat it as the same type of science as the scientific work that gives us new vaccines or devices based on quantum physics. Here's just a couple of those headlines:

• Aliens from a Parallel Universe May Be All Around Us – And We Don’t Even Know It, Study Suggests (Popular Mechanics) – By definition anything can be happening in a parallel universe we can’t detect, but what does it tell us?

• Could we travel to parallel universes? (Live Science) – No.

• Our reality seems compatible with a quantum multiverse (New Scientist) – It’s also compatible with invisible dragons. It doesn’t mean that either exists.

Should Sabine be so outspoken? Why not. Should she have been disaffiliated - certainly not. Should the scientist whose work she criticised have complained. No. I review a lot of books: just occasionally, an author will complain about a negative review. It's not a good move for them or for the book. The same applies to responding badly to critiques of your pet scientific theories. Grow up, science community. And listen to the criticism, even if it could have been more polite. We need science to be accepted by the public who fund it - and that means being prepared to admit when you've got things wrong.

* Sabine identifies neither the physicist nor the specific video

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here

September 12, 2025

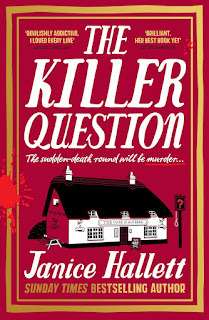

The Killer Question - Janice Hallett *****

It's very rare I pause the book I'm reading because another one has come out - but when it's a new Janice Hallett I really have no choice. And it was well worth the interruption.

It's very rare I pause the book I'm reading because another one has come out - but when it's a new Janice Hallett I really have no choice. And it was well worth the interruption.As we've come to expect from Hallett, the book is made up of forms of communication - in this case texts, WhatsApp group messages and emails, plus transcription of some police recordings. At first sight this is a simple crime setup. We are introduced to Sue and Mal Eastwood who are relatively new at running a pub - central to the story is their pub quiz, where we get introduced to a whole cast of characters in the regular teams before a sinister new team joins and wipes the floor with everyone else. Things are shaken up when a body is discovered nearby.

However, being Hallett, there are also some huge twists along the way. We quickly find out about links to a major kidnapping case in the past involving key characters... and things get more and more twisty from there.

As someone who write murder mysteries for fun, my starting point when reading a Hallett novel is sheer awe at the cleverness of the way she constructs the book - and that applies here in spades. It should be easy to get lost, or to lack a feeling for the characters when almost everything is down to messaging, but she pulls off making this deeply engaging. Is it her best yet as claimed on the cover? I'm not sure - but it certainly has some of the best twists, and I'd put it in the top three. Whatever, a new Hallett is a joy.

Anyone who enjoys murder mysteries and hasn't experienced one of these books is missing a trick.

You can buy The Killer Question from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here