Brian Clegg's Blog, page 8

February 12, 2025

A Short Infinite Series #3 - Achilles and the tortoise

An infinite series is a familiar mathematical concept, where '...' effectively indicates 'don't ever stop' - for example 1 + ½ + ¼ + ⅛... an infinite series totalling 2. This, though is a short series of posts about infinity, based on my book

A Brief History of Infinity

.At first sight, chains of numbers that go on forever seem harmless and without consequence, but it doesn’t take long to find some that will cause difficulties. Let’s say that rather than just list the numbers we add them all up as we go along to produce a sum. And let’s take a very simple series – just alternating 1 and -1: something like 1-1+1-1+1-1+1-1...

An infinite series is a familiar mathematical concept, where '...' effectively indicates 'don't ever stop' - for example 1 + ½ + ¼ + ⅛... an infinite series totalling 2. This, though is a short series of posts about infinity, based on my book

A Brief History of Infinity

.At first sight, chains of numbers that go on forever seem harmless and without consequence, but it doesn’t take long to find some that will cause difficulties. Let’s say that rather than just list the numbers we add them all up as we go along to produce a sum. And let’s take a very simple series – just alternating 1 and -1: something like 1-1+1-1+1-1+1-1...It’s hardly rocket science. We can see how it will total by adding some brackets:(1-1)+(1-1)+(1-1)...

Each 1 is cancelled out by a -1, so the total of the series is 0. Or is it? Just shift the brackets and we still have a series that cancels out, but now we’ve got a 1 left over:1+(-1+1)+(-1+1)...

So the same series has a value of 0 and 1. Scary. This has been rephrased as 'If you turn a light bulb off and on for infinity, does it end up on or off?' It could be either. That is clearly an example told by a mathematician – a physicist would tell you that it will obviously be off, because the bulb will have blown.

Or take the simple series at the top of this post where each item is half the value of the last:1 + ½ + ¼ + ⅛...

It seems, as we add in element after element, that it’s going to eventually reach two, though in practice with any particular number there’s always a little gap left. In fact you could say it added up to two if you had an infinite set of numbers – but what does that mean? And how can an infinite list of things (whatever it is) add up to a finite quantity?

This was the basis of one Zeno’s famous paradoxes. Zeno, who was born as far back as around 539 BC, belonged to the school of Parmenides, which considered reality to be unchanging and movement to be an illusion. Zeno knocked up a number of rather entertaining examples to demonstrate the faulty nature of our attitude to change and motion.

Probably the best known is the arrow, which encourages us to imagine two arrows. One floats stationary in space. The other is flying at full speed. Now catch them at a snapshot in time. How do we tell the difference? For that matter, how does one arrow know to move in the next fraction of time while the other doesn’t? But the paradox that reflects our sequence concerns Achilles and the Tortoise. This unlikely pair are setting out on a race. Achilles, being after all a hero, gives the slower tortoise a lead. And they’re off.In a very small amount of time, Achilles has reached the Tortoise’s position. But by then, the tortoise has moved on. In an even shorter amount of time, Achilles has reached the Tortoise’s new spot. And again it has moved on. And it doesn’t matter how many times you go through this procedure – an infinite set of times if you like – Achilles will never catch the Tortoise up.

It’s easy to see the relationship of this paradox and the series if we pretend that Achilles only runs twice as fast as the tortoise (perhaps he’s pulled a hamstring or his Achilles tendon). In the time Achilles covers the first distance, the Tortoise moves half that distance. While Achilles is catching up, the tortoise moves ¼ the original distance. In an infinite number of moves they will only get to twice the original distance (which is where, of course the paradox falls down as Achilles powers through that mark).

There certainly is something unsettling, both about the idea of infinity itself and some infinite series. The Greeks weren’t really sure what to do with it. They called infinity 'apeiron', a word that had the same sort of negative connotations as chaos does today. It meant unbounded, uncontrolled, dangerous.

You can buy my book A Brief History of Infinity from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youImage from Unsplash by Joel Mathey (Achilles is just out of shot)These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:Article by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereFebruary 10, 2025

Quantum mechanics in five minutes

A few years ago I was set the challenge of explaining quantum physics to the then BBC broadcast journalist Robert Peston in 5 minutes.

A few years ago I was set the challenge of explaining quantum physics to the then BBC broadcast journalist Robert Peston in 5 minutes.In practice, of course, this is a pretty much an impossible task, but the idea was to give a quick taster - which I hope it does.

I've written quite a bit on quantum physics, if it's something you'd like to dig into a bit deeper:

The God Effect - exploring quantum theory's most mind-boggling concept, entanglement with implications from teleportation to unbreakable encryption Cracking Quantum Physics - an illustrated beginner's guide to the quantum world The Quantum Age - focuses on the applications of quantum physics that have transformed our world Quantum Computing - how computers making use of explicit quantum effects have the potential to run algorithms that perform in ways impossible to duplicate with conventional devices.Here's that video:These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereFebruary 3, 2025

A Short Infinite Series #2 - big numbers

An infinite series is a familiar mathematical concept, where '...' effectively indicates 'don't ever stop' - for example 1 + ½ + ¼ + ⅛... an infinite series totalling 2. This, though is a short series of posts about infinity.Strictly, this one is just about big numbers - but it's on the way to the real thing. There’s something special about big numbers. It’s almost as if by being able to give a big number a name we demonstrate our power over it – and, of course, the bigger the number is, the more power we have. A classic example of this is in the reported early life of Gautama Buddha. As part of his testing as a young man in an attempt to win the hand of his beloved Gopa, Gautama was required to name numbers up to some huge, totally worthless value – and managed to go even further to show how clever he was.

An infinite series is a familiar mathematical concept, where '...' effectively indicates 'don't ever stop' - for example 1 + ½ + ¼ + ⅛... an infinite series totalling 2. This, though is a short series of posts about infinity.Strictly, this one is just about big numbers - but it's on the way to the real thing. There’s something special about big numbers. It’s almost as if by being able to give a big number a name we demonstrate our power over it – and, of course, the bigger the number is, the more power we have. A classic example of this is in the reported early life of Gautama Buddha. As part of his testing as a young man in an attempt to win the hand of his beloved Gopa, Gautama was required to name numbers up to some huge, totally worthless value – and managed to go even further to show how clever he was. But you don’t need to go back in history to examine this fascination. Anyone with children will have heard them counting, running away with sequences of numbers as if they’re trying to find the end. It’s not just for fun, of course. These counting sequences are hammered into us at school to help build familiarity with the numbers. Most of you will also be familiar with rhymes, used for the same purpose. For example, One two three four five, once I caught a fish alive, and so on. But there is a slight danger that arises from the use of these sequences – our tendency to remember in strings of information can become a hindrance to flexibility. Try counting 1 to 10 then 10 to 1 in a language you aren’t totally fluent in – you will find 10 to 1 much harder.

It’s fine giving names to numbers we need to use (or useless ones to show off), but realistically how many of us ever use this number:

10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000

As it happens it does have a name, one that proved something of a problem for the unfortunate Major Charles Ingram when it was his million pound question on Who Wants to be a Millionaire. He was asked if the number – 1 with 100 noughts after it – was a googol, a megatron, a gigabit or a nanomol. Major Ingram favoured the last of these until a cough from the audience came along to push him in he right direction, and to be honest, who can blame him? A googol frankly sounds childish. And there’s a good reason for that. It is. Literally.

In 1938, according to maths legend, mathematician Ed Kasner was working on some numbers at home and his nephew, 9-year-old Milton Sirotta, spotted this and said something to the effect of ‘that looks like a google’. I’m not convinced – I just can’t see why Kasner would bother to write that on a blackboard, and think it’s more likely he just asked his nephew, what you call a really, really, REALLY big number (say 1 with 100 noughts after it)’ and up pipes Milton ‘a google.’

But this urge to give names to large numbers dates back even further than Buddha. Right back, in fact, to Archimedes, who was born some time around 287 BC. In one rather strange little book, Archimedes made an attempt to count the number of grains of sand that would fill the universe. This clearly wasn’t a practical proposition. But the Greek number system was extremely clumsy, and what Archimedes seems to have been doing in his book, The Sand Reckoner, is to demonstrate that it’s perfectly possible to extend the system as far as you like.

Archimedes starts the book, addressed to King Gelon of Syracuse, by pointing out that some people reckon that there are an infinite number of grains of sand in the world. What he meant by this was not literally infinite, but an uncountable and incalculable number. And then, perversely, Archimedes set out to show this wasn’t true – and just to rub it in, calculated how many grains it would take not only to cover the Earth, but to fill the whole universe. It’s an impressive feat, though we need to be a little careful about what we mean by universe. Archimedes had in mind a picture of everything that had the Earth at the centre of a number of spheres. Around us went the moon, the sun, the planets and finally the stars. So the ‘universe’ he would fill with sand was more like our idea of the solar system – even so, quite a size. Tantalisingly, Archimedes goes a little further. He imagines an even bigger universe, suggested by an off-the-wall theory around at the time that instead of the sun moving around the Earth as it obviously does, the Earth moved around the sun. It’s tantalising because Archimedes’ passing mention of this theory of Aristarchus is the only surviving reference to the earliest known person to spot that we move around the sun rather than the other way around. After making a few assumptions like ‘the diameter of the earth is greater than the moon, and the diameter of the sun is greater than the earth’ (many close to the truth) and some elegant geometry, Archimedes comes to the conclusion that the universe is no more than 10 billion stades across. That’s a measurement based on a stadium, just as we often estimate in football pitches, at around 180 metres, so it probably makes his universe 1,800 million kilometres, which at just outside the orbit of Saturn really isn’t bad. I say probably because stades were a local measure - a stadion was the distance around your local stadium and didn't have a universally accepted value. But it's order of magnitude correct. Archmedes then begins to work up from a grain of sand, through a poppy seed to greater and greater size. He had a bit of a problem, though, as the biggest number in the Greek system was a myriad – 10,000. Archimedes set up a whole supersystem. Everything up to a myriad myriads was the first order. Multiply that by itself and you got the second order. And so on. Do that a myriad myriad times and you’d reached the end of the first period. And so on one again. With a few rules to make this ‘new maths’ work, he was able to put the number of grains of sand in the universe as less than 1,000 units of the seventh order (1051), or in Aristarchus’s bigger universe, less than 10 million of the eighth order (1063). Even by today's standards these are pretty big numbers.

You can buy my book A Brief History of Infinity from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youImage from Unsplash by Keith Hardy - not much sand by Archimedes' reckoning.These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereFebruary 1, 2025

Exceptions, proofs, rules and puddings

The English language is a tricksy thing, replete with sayings that can, on the face of it, appear odd, or that get mangled after many repetitions. I recently heard something about one of these on the excellent The Studies Show podcast, hosted by Stuart Ritchie and Tom Chivers, that made me raise an eyebrow, because they claimed my interpretation of a saying was a myth.

The English language is a tricksy thing, replete with sayings that can, on the face of it, appear odd, or that get mangled after many repetitions. I recently heard something about one of these on the excellent The Studies Show podcast, hosted by Stuart Ritchie and Tom Chivers, that made me raise an eyebrow, because they claimed my interpretation of a saying was a myth.The saying in question was 'the exception proves the rule'. I want to come back to that after a brief excursion into another saying that involves puddings.

One of the most cringe-making things for me is when I hear someone on the TV or radio say 'The proof is in the pudding.' This is a totally meaningless statement resulting from mangling the saying 'The proof of the pudding is in the eating'. Anyone using the first version needs to be sent to an English Language re-education camp immediately. But the real version itself can look distinctly confusing. We can prove a mathematical theorem, or that black swans exist... but how do you prove a pudding?

The saying depends on being aware that 'prove' has a less familiar meaning of 'test'. In fact, if you look up 'prove' in the Oxford English Dictionary, the very first definition is 'to make a trial of; to try, to test'. With this in mind, we can see that what's being said here is you can test how good a pudding is by eating it. It's not exactly great wisdom, but it makes sense.

So we move onto that disputed saying 'the exception proves the rule'. This feels weird because you might think that an exception disproves a rule. If a rule is, for example, if we posit a rule that 'all prime numbers are odd' and we point out that 2 is a prime number, this is an exception to that rule, which disproves it. Disproving theories and rules is a central part of doing science or maths.

However, if we use the same meaning of 'test' for 'prove' as we did with the pudding, it makes total sense. We are 'making a trial' of that rule with an exception and breaking it. Yet Chivers and Ritchie (sound like an upmarket jam manufacturer) say that this is a myth.

The basis for this suggestion, I suspect, is that there was a Latin legal phrase 'exceptio probat regulam in casibus non exceptis', which translates as 'the exception proves the rule in cases without exceptions' - which, to be honest, doesn't make much sense except as an indirect way of saying that rules need to exclude situations where the rules don't apply - a total truism. But these aren't the same words, and there is always a danger of deriving English constructs from Latin - this is what led to the bizarre idea that split infinitives should be allowed in English because you can't do them in Latin.

I don't doubt that the Latin phrase may have been the original inspiration of the English phrase. Emphasis on the 'may' - I am not aware of good evidence for the direct link. However, equally there is no doubt that the pudding-style 'proof' here is a valid interpretation of the phrase that frankly is more effective than the Latin use (and the OED supports it as a possible meaning), so it feels wrong to call it a myth.

While we're in the world of puddings, incidentally, I'll finish by briefly mentioning Rutherford's 'plum pudding' model of the atom, where there definitely is a myth involved. I've seen many popular science titles say that in this model the electrons are represented by plums. Unfortunately, plum pudding is an archaic name for a Christmas pudding (see illustration), where 'plum' was as a generic term for dried fruit. Christmas puddings don't contain plums and Rutherford had grape-derived dried fruit such as raisins in mind.

Image from Unsplash by Matt Seymour

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereJanuary 29, 2025

Coming Soon

After my voluntary break from popular science over the Christmas period, I've also had a dearth of review copies for books out in January. But there's a whole heap of both science and science fiction titles sitting on the review pile - so while reviews themselves are in short supply, here's a few books where the reviews are coming soon:Already published (awaiting copy) - I

nto the Great Wide Ocean

- Sönke Johnsen - takes readers inside the peculiar world of the seagoing scientists who are providing tantalizing new insights into how the animals of the open ocean solve the problems of their existence.4 February -

Hoodwinked

- Mara Einstein - from viral leggings to must-have apps, exposes the hidden parallels between cult manipulation and modern marketing strategies in this eye-opening investigation. Reveals how companies weaponize psychology to transform casual customers into devoted followers.6 February -

Phenomena

- Camille Juzeau and The Shelf Company - from fireflies to the Big Bang, from the magnificent maps of the world’s sands to the anatomy of ice crystals, these 125 illustrated graphic phenomena are designed to take you on a stroll through the vast world of knowledge.13 February -

Against the Odds

- John and Mary Gribbin - highlights the achievements of women who overcame hurdles and achieved scientific success (although not always as much as they deserved) in spite of male prejudice, as society changed over about 150 years, from the middle of the nineteenth century to the end of the twentieth century. Includes Eunice Newton Foote, who discovered the carbon dioxide greenhouse effect; Chien-Shiung Wu, who discovered the law which allows matter to exist in the Universe today; and Barbara McClintock, who discovered how genes turn on and off.27 February -

Pagans

- James Alistair Henry - an alternative history crime novel set in a 21st century London where the Norman conquest never happened and Christianity is a minor cult, with modern Britain based on the ancient tribes - but murders still need to be solved.1 March -

Amazing Worlds of Science Fiction and Science Fact

- Keith Cooper - explores the fictional planets from films such as Star Wars, Dune and Avatar, and discusses how realistic they are based on our current scientific understanding and astronomical observations. 13 March -

The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire

- Henry Gee - inspired by Edward Gibbon's The History of the Decline and Fall of the Human Empire, Gee follows up his Royal Society Prize winner

A (Very) Short History of Life on Earth

with a book that plots the future of humanity, suggesting that space habitats may be the best way to keep our species alive.... and many more. Note that the dates are the release date of the books in the UK - I aim to get reviews out as close as possible to this, but it's not a guarantee!

After my voluntary break from popular science over the Christmas period, I've also had a dearth of review copies for books out in January. But there's a whole heap of both science and science fiction titles sitting on the review pile - so while reviews themselves are in short supply, here's a few books where the reviews are coming soon:Already published (awaiting copy) - I

nto the Great Wide Ocean

- Sönke Johnsen - takes readers inside the peculiar world of the seagoing scientists who are providing tantalizing new insights into how the animals of the open ocean solve the problems of their existence.4 February -

Hoodwinked

- Mara Einstein - from viral leggings to must-have apps, exposes the hidden parallels between cult manipulation and modern marketing strategies in this eye-opening investigation. Reveals how companies weaponize psychology to transform casual customers into devoted followers.6 February -

Phenomena

- Camille Juzeau and The Shelf Company - from fireflies to the Big Bang, from the magnificent maps of the world’s sands to the anatomy of ice crystals, these 125 illustrated graphic phenomena are designed to take you on a stroll through the vast world of knowledge.13 February -

Against the Odds

- John and Mary Gribbin - highlights the achievements of women who overcame hurdles and achieved scientific success (although not always as much as they deserved) in spite of male prejudice, as society changed over about 150 years, from the middle of the nineteenth century to the end of the twentieth century. Includes Eunice Newton Foote, who discovered the carbon dioxide greenhouse effect; Chien-Shiung Wu, who discovered the law which allows matter to exist in the Universe today; and Barbara McClintock, who discovered how genes turn on and off.27 February -

Pagans

- James Alistair Henry - an alternative history crime novel set in a 21st century London where the Norman conquest never happened and Christianity is a minor cult, with modern Britain based on the ancient tribes - but murders still need to be solved.1 March -

Amazing Worlds of Science Fiction and Science Fact

- Keith Cooper - explores the fictional planets from films such as Star Wars, Dune and Avatar, and discusses how realistic they are based on our current scientific understanding and astronomical observations. 13 March -

The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire

- Henry Gee - inspired by Edward Gibbon's The History of the Decline and Fall of the Human Empire, Gee follows up his Royal Society Prize winner

A (Very) Short History of Life on Earth

with a book that plots the future of humanity, suggesting that space habitats may be the best way to keep our species alive.... and many more. Note that the dates are the release date of the books in the UK - I aim to get reviews out as close as possible to this, but it's not a guarantee!These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here

January 27, 2025

Patronising Bastards - Quentin Letts ****

Parliamentary sketch writers have a very dated style of writing - their 'humour' feels both heavy handed and has a grotesquery more suited to an eighteenth century political cartoon than the modern day. In this book, Quentin Letts (a sketch writer in his day job) does deploy some of this style in his ad hominem remarks about individuals - and I probably disagree with about 90 per cent of his viewpoints (though I'm definitely with him on hymns, the House of Lords and justice being blind).

Parliamentary sketch writers have a very dated style of writing - their 'humour' feels both heavy handed and has a grotesquery more suited to an eighteenth century political cartoon than the modern day. In this book, Quentin Letts (a sketch writer in his day job) does deploy some of this style in his ad hominem remarks about individuals - and I probably disagree with about 90 per cent of his viewpoints (though I'm definitely with him on hymns, the House of Lords and justice being blind).But - and it's a big but - what I do absolutely agree with is that subtitle - 'how the elites betrayed Britain'. Letts highlights the horror of the Establishment when the people turn against them by, say, voting for Brexit or a certain US president. Without supporting either of these it is easy to see why it is happening. Just this morning I heard on a podcast a well-known political commentator (and self-affirmed member of said elite) saying how Brexit remains incomprehensible to people like him. And that's the problem.

Letts catalogues a whole parcel of ways members of the Establishment feather their own nest without considering the ordinary people. He gives us a tour of public bodies such as the Arts Council, various commissions, the whole EU gravy train, of course the House of Lords, and far more where our liberal elite rewards those who network well and have friends in the right places at the expense of the rest of us. He is pitiless in uncovering the patronising attitude of the liberal elite to ordinary people. The same commentator on the podcast was hoping that the voters would realise how wrong they were in a wonderfully patronising fashion - he called their decisions irrational, without even trying to understand the genuine reasoning that is there.

This combination of patronising distaste and 'we're obviously right because we personally benefit from the approach' is particularly obvious if you live outside of London and the South East (think of the difference between the treatment of the Elizabeth Line and HS2). The result is lashing out the only way the masses can. Leaving the EU, for instance, may well be considered self-destructive in terms of GDP, say, but to paraphrase a northerner Letts quotes, why should he care about GDP when he never sees any of it.

This, then, is the reason I give the book four stars. There are very few commentators from the elite (which Letts certainly is) who really get what's behind the populism and how things really need to change if we are to get away from this situation. It's a difficult book to read when you do feel naturally antagonistic to many of Letts' viewpoints... but if you can put aside that feeling it's very informative.

You can buy Patronising Bastards from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereJanuary 24, 2025

A Short Infinite Series - #1

An infinite series is a familiar mathematical concept, where '...' effectively indicates 'don't ever stop' - for example 1 + ½ + ¼ + ⅛... an infinite series totalling 2. This, though is a short series of posts about infinity.

An infinite series is a familiar mathematical concept, where '...' effectively indicates 'don't ever stop' - for example 1 + ½ + ¼ + ⅛... an infinite series totalling 2. This, though is a short series of posts about infinity.I wrote A Brief History of Infinity a while ago because it's a topic I've found fascinating since I was at school. To kick off the series, here's the introduction of that book, which summarises why it's a subject that intrigues so many:

The infinite is a concept so remarkable, so strange, that contemplating it has apparently driven at least two great mathematicians over the edge into insanity. In the Hitch-hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Douglas Adams described how the writers of his imaginary guidebook got carried away in devising its introduction:

‘Space’, it says, ‘is big. Really big. You just won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is. I mean, you may think it’s a long way down the street to the chemist, but that’s just peanuts to space. Listen…’ and so on. After a while the style settles down a bit and it starts telling you things you actually need to know…

Infinity makes space seem small.

Yet this apparently unmanageable concept is also with us every day. My daughters were no older than six when they first began to count quicker and quicker, ending with a blur of words and a triumphant cry of ‘infinity!’ And though infinity may in truth make space seem small, when we try to think of something as vast as the universe, infinite is about the best label our minds can apply.

Anyone who has broken through the bounds of basic maths will have found the little ∞ symbol creeping into their work (though we will discover that this drunken number eight that has fallen into the gutter is not the real infinity, but a ghostly impostor). Physicists, with a typical carelessness that would make any mathematician wince, are cavalier with the concept. When I was at school, studying A-level (high school) physics, a common saying was ‘the toast rack is at infinity.’ This referred to a nearby building, part of Manchester Catering College, built in the shape of a giant toast rack. (The resemblance is intentional, a rare example of humour in architecture. The companion building across the road, when seen from the air, looks like a fried egg.) We used the bricks on this imaginative structure to focus optical instruments. What we really meant by infinity was that the building was ‘far enough away to pretend that it is infinitely distant’.

Infinity fascinates because it gives us the opportunity to think beyond our everyday concerns, beyond everything to something more – as a subject it is quite literally mind-stretching. As soon as infinity enters the stage it seems as if common sense sanity leaves. Here is a quantity that turns arithmetic on its head, making it seem entirely feasible that 1 = 0. Here is a quantity that enables us to cram as many extra guests as we like into an already full hotel. Most bizarrely of all, it is quite easy to show that there must be something that is bigger than infinity – which surely should be the biggest thing there could possibly be.

Although there is no science more abstract than mathematics, when it comes to infinity, it has proved hard to keep spiritual considerations out of the equation. When human beings contemplate the infinite, it is almost impossible to avoid things theological, whether in an attempt to disprove or prove the existence of something more, something greater than the physical universe. Infinity has this strange ability to be many things at once. It is both practical and mysterious. Mathematicians, scientists and engineers use it quite happily because it works – but they consider it a black box, having the same relationship with it that most of us do with a computer or a mobile phone, something that does the job even though we don’t quite understand how.

The position of mathematicians is rather different. For them, modern considerations of infinity shake up the comfortable, traditional world in the same way that physicists suffered after quantum mechanics shattered the neat, classical view of the way the world operated. Reluctant scientists have found themselves having to handle such concepts as particles travelling backwards in time, or being in two opposite states at the same time. As human beings, they don’t understand why things should be like this, but as scientists they know that if they accept the picture it helps predict what actually happens. As the great twentieth century physicist Richard Feynman said in a lecture to a non-technical audience:

It is my task to convince you not to turn away because you don’t understand it. You see, my physics students don’t understand it either. That is because I don’t understand it. Nobody does.

Infinity provides a similar tantalising mix of the normal and the counter-intuitive.

All of this makes infinity a fascinating, elusive topic. It can be like a deer, spotted in the depths of a thick wood. You will catch a glimpse of beauty that stops you in your tracks, but moments later you are not sure if you saw anything at all. Then, quite unexpectedly, the magnificent animal stalks out into full view for a few, fleeting seconds.

A real problem with infinity has always been getting though the dense undergrowth of symbols and jargon that mathematicians throw up. The jargon is there for a very good reason. It’s not practical to handle the subject without some use of these near-magical incantations. But it is very possible to make them transparent enough that they don’t get in the way. To open up clear views on this most remarkable of mathematical creatures, a concept that goes far beyond sheer numbers, forcing us to question our understanding of reality.

Welcome to the world of infinity.

You can buy A Brief History of Infinity from Amazon.co.uk, NEXT Amazon.com and Bookshop.org

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereJanuary 18, 2025

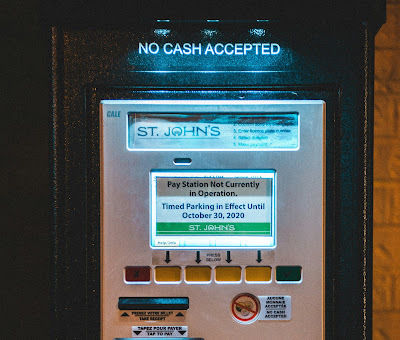

Cashless spending 2008 style revisited

REVISIT SERIES - An updated post from October 2008The excellent Claudia Hammond has recently done a podcast on the Mondex experiment, an early attempt at a cashless approach to shopping. I took part in this experiment, so it seemed an ideal opportunity to take a look back, both at the experiment itself and how cashless payments differ from what seemed likely in those heady days when contactless and smartphones were in their infancy.

REVISIT SERIES - An updated post from October 2008The excellent Claudia Hammond has recently done a podcast on the Mondex experiment, an early attempt at a cashless approach to shopping. I took part in this experiment, so it seemed an ideal opportunity to take a look back, both at the experiment itself and how cashless payments differ from what seemed likely in those heady days when contactless and smartphones were in their infancy.Pretty well everyone needs money really, I guess, but what I meant was 'who needs cash?' [The original post was entitled 'Who needs money?'] The irritating chunks of metal that mean I rarely have a pair of trousers that last more than a year without holes appearing in the pockets (hint, trouser designers - stronger pockets, please). And you always accumulate all those copper coins that you can't be bothered to bag up and take to the bank, so they end up in a charity box or gather dust in a big jar.

Now, when I first moved to the Swindon area a little over 12 years ago, I arrived at the tail end of an experiment that held out hopes of changing all that. It was called Mondex, and it was brilliant.

You got a chip and PIN style card and you downloaded money onto it. Then you used it for all purchases where you'd normally use cash. Of course that's not so different from a debit card, but this was more controllable, and you could use it at lots of places that wouldn't have a debit/credit card reader. Where merchants get stung for accepting a credit card in a way that makes buying a bag of sweets that way inacceptable, with Mondex it was fine. Even the street newspaper vendors in Swindon had them.

Perhaps the biggest advantage it had over cash was you could get money at home. With a card-reading/writing Mondex phone, you could put cash on your card whenever you liked.

Now Mondex is a museum piece but Barclays has recently announced the OnePulse card, combining a credit card, Oyster Card and payment card, usable in over 1,000 shops in London for purchases under £10 (though payment does come from the credit card, not loaded cash), which may see the resurrection of the concept. I'm very tempted to get one.

However, I suspect the next generation of cashless payment will be different. The best contenders at the moment are either expanding debit card use so it is acceptable for a 20p purchase (and everyone accepts them, which means slashing the cost to merchants) or using something else like a mobile phone to initiate the payment.

Admittedly we already have this to an extent in those car parks where you can pay by phone, but they are too low tech and desperately slow. With mark II phone payment I would imagine typing a number from the car park (or newspaper vendor or whatever) into my phone (or more likely scanning a barcode or reading an RFID chip), entering the amount I want to pay and paying instantly.

Whatever the technical solution, I just can't wait to get rid of cash!

I'm rather proud looking back from 2025 just how much I got right - including using a phone and reading an RFID chip (i.e. contactless), though parking apps on the phone were something I'd yet to encounter. I didn't get a OnePulse, which rapidly disappeared.

Image by Erik Mclean from Unsplash

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereJanuary 16, 2025

How not to sell AI

I get a fair amount of cold selling emails, and recently received one that showed exactly why it's important to check what is going into an email, particularly if the email itself reflects what it is you are trying to sell.

I get a fair amount of cold selling emails, and recently received one that showed exactly why it's important to check what is going into an email, particularly if the email itself reflects what it is you are trying to sell. The company in question is attempting to demonstrate how AI can help a business... but all they manage to do is show how it can be a disaster.

Here's what I received (to avoid embarrassment I have removed the name and website of the sender who was the owner of a company whose strapline is 'Do you know how to effectively integrate AI into your business':

What is clear is they don't know how to effectively integrate AI into their business. It doesn't help that they actually tell us that the email is supposed to include an AI-sourced first line from a 'artical' (sic) they saw. And what did they really appreciate? Their website is slick and clearly has had a fair amount of effort put into it. It's unfortunate that they could demonstrate so effectively how to get it wrong.

Image by Igor Omilaev from Unsplash

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereJanuary 15, 2025

O Sing Unto the Lord: Andrew Gant *****

This is one for the music history fans, and/or those with an interest in church music. This definitely includes me - I've sung in choirs since I was about 10 and this kind of music is amongst my favourite listening. Andrew Gant does a brilliant job of digging into English church music throughout history, though almost inevitably the biggest focus is from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries.

This is one for the music history fans, and/or those with an interest in church music. This definitely includes me - I've sung in choirs since I was about 10 and this kind of music is amongst my favourite listening. Andrew Gant does a brilliant job of digging into English church music throughout history, though almost inevitably the biggest focus is from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries.This might seem a very dry subject, but Gant brings it alive, helped by his even drier sense of humour. This is obviously a matter of taste, but if you find amusing his remark on Prince Albert's compositions 'He certainly did not possess a strong enough musical personality to overcome the prevailing tendency to write bad Mendelssohn, but he did it quite well. His Te Deum and Jubilate contain some quite good bad Mendelssohn,' you will enjoy it as I did.

Inevitably the Reformation and subsequent switches of England between protestant and Catholic features heavily with its fascinating impact on composers and their work - particularly complex during Elizabeth's reign, when a staunchly Catholic composer like Byrd was able to keep his balance (and his head) by being considered a sufficiently impressive musician that he was allowed to get away with much that might have end the career or life of another. The basics of that were familiar to me, but a lot of the period through to the Victorians was new. Music we would consider everyday now like hymns and their tunes (which Gant points out even turn up as football chants) really only started to come together towards the end of the eighteenth century (and weren't technically legal for use in Church of England services until 1820), while Anglican chant, familiar to any choral evensong fan was primarily a nineteenth century innovation - along, of course, with much of the Christmas repertoire.

The twentieth century and beyond gets rather summary treatment. In part I think this is fair. As Gant points out it was a time of splintering. Where almost all earlier periods had specific styles and approaches, most twentieth century church composers very much did their own thing. I think Gant could have put a bit more into analysis of the development of worship songs (rather outside his comfort zone, I suspect, though he says some positive, or at least fair things).

A couple of small negatives. The book is a bit too long. While prepared to mention quite a few unfamiliar names from, say, the Tudorbethan period, it sticks to the well-known in Victorian and Edwardian times, ignoring those who were very popular then but have pretty much disappeared. For example, I was disappointed not get a mention of Caleb Simper whose sheet music sold incredibly well (over 5 million copies) and was a staple of many country and colonial churches. The illustrations are also irritating - they were clearly designed for plates, so are bunched together in two lumps, but are just printed on ordinary pages, so could have been placed near the text they illustrate to much greater effect.

I realise that the readership of a book like this is relatively limited. But if, like me, this kind of music plays an important part in your life, then it is an absolute must to own.

You can buy O Sing Unto the Lord from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here