Brian Clegg's Blog, page 5

May 11, 2025

The Devil and the Dark Water - Stuart Turton ****

After reading Stuart Turton's third and first novels (in that order), I had to fill in the middle one. I have to admit up front that its setting on a seventeenth century ship appealed to me far less than the other two, but going on Turton's ability to produce remarkable mystery novels, it seemed a no-brainer and it didn't disappoint.

After reading Stuart Turton's third and first novels (in that order), I had to fill in the middle one. I have to admit up front that its setting on a seventeenth century ship appealed to me far less than the other two, but going on Turton's ability to produce remarkable mystery novels, it seemed a no-brainer and it didn't disappoint.We rapidly follow the cast from the Dutch East India Company on board from Batavia (now Jakarta) on a journey to Amsterdam fraught with peril, both natural and apparently supernatural. The book is described as a historical locked room mystery - but that's just a smallish part of the plot, and the author emphasises this is fiction with a historical setting, not the kind of hist fic that aims to get every detail right.

Central characters include a pairing seemingly based on the classic fantasy combo that began with Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser - a huge mercenary and a diminutive magician, though here the smaller character is a detective, the unlikely named, Holmes-like Samuel Pipps. We do also get some strong female characters to balance the cast, though no one is entirely what they seem.

It remains my least favourite of the three. Even more so than Evelyn Hardcastle it's too long, and I did find the shipboard setting limiting. It was also frustrating that arguably the most interesting character in the book, Samuel Pipps (really?), was kept locked in a cell for the majority of the story. But despite this, it's still an enjoyable read with some entertaining twists along the way. The ending is outrageously unlikely, but certainly takes the reader by surprise.

You can buy The Devil and the Dark Water from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereMay 8, 2025

Human Remains - Jo Callaghan *****

In the third of her AIDE Lock/DCS Kat Frank novels, Jo Callaghan demonstrates again her ability to produce a page turner. Interwoven with a complex case involving the titular human remains are doubts about Frank's previous success putting away a serial killer, raised by a true crime podcast, and the presence of a stalker who seems intent on harming Frank.

In the third of her AIDE Lock/DCS Kat Frank novels, Jo Callaghan demonstrates again her ability to produce a page turner. Interwoven with a complex case involving the titular human remains are doubts about Frank's previous success putting away a serial killer, raised by a true crime podcast, and the presence of a stalker who seems intent on harming Frank.All the above would be enough to make a good novel in its own right, but the reason this series is so good is the involvement of the holographic AI detective Lock. His technical abilities are remarkable, yet even the professor who created him seems worried about the AI's insistence that he would be even more use if he had some form of physical body. The questions raised by his involvement, and the limitations his nature pose (when, for example, he ignores evidence because he wasn't explicitly asked to look out for it) add a huge amount to the depth of the book.

The tension of the closing act is remarkable - once I started reading it I had to finish. There's a dramatic twist that leads to some impressive soul searching about AI officers having a physical presence. It's a remarkable piece of writing.

I've previously commented on the difficulties presented in making some of Lock's abilities real, and there is a significant move away from him being dependent on a bracelet worn by Frank (though it was too late to avoid a hologram projected into empty space) - but I think he needs an upgrade on his research abilities. Lock frequently picks up vast numbers of studies online, but clearly doesn't know how to check quality - he repeats the Baby Mozart myth, despite it being dismissed as one of the many victims of the replication crisis in the social sciences.

This is trivial, though. Overall, this is the best yet in this excellent series.

You can buy Human Remains from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereMay 6, 2025

Less can be more in a bookshop, revisited

REVISIT SERIES - An updated post from May 2015I have a confession that will make most authors' lib people - you know, the ones who unfriend you on Facebook if you confess to buying anything from Amazon - quake in their sandals: I find many independent bookshops intimidating.I don't like their often dark, claustrophobia inducing interiors, and I don't like being talked to by staff unless I invite it. (Please note, Mary Portas, who regularly advises that good customer services involves welcoming customers and trying to help them. I don't want to be chatted to by a stranger. I'd rather help myself. If I want assistance I will ask for it. If your staff approach me, I will leave without making a purchase.)

REVISIT SERIES - An updated post from May 2015I have a confession that will make most authors' lib people - you know, the ones who unfriend you on Facebook if you confess to buying anything from Amazon - quake in their sandals: I find many independent bookshops intimidating.I don't like their often dark, claustrophobia inducing interiors, and I don't like being talked to by staff unless I invite it. (Please note, Mary Portas, who regularly advises that good customer services involves welcoming customers and trying to help them. I don't want to be chatted to by a stranger. I'd rather help myself. If I want assistance I will ask for it. If your staff approach me, I will leave without making a purchase.)So it was with some nervousness that I entered the Mad Hatter Bookshop in the pretty (or to put it another way, Cotswold tourist trappy) location of Burford, surprisingly close to my no-one-could-call-it-tourist-trappy home of Swindon. But I'm glad I did. I was even glad to be welcomed as I came in, though I admit if other shop owners said 'You're Brian Clegg, aren't you?' I would be happier with the concept, Ms Portas please note.

The reason I was particularly glad was that I discovered the real advantage a shop like this can have over Waterstones. (And, no, I don't mean the advantage of selling hats.) A largish Waterstones falls uncomfortably between two stools. It can't complete with an online store on stock. So if I want a specific book, half the time it's not there and I'm much better off going online. But, on the other hand, the Waterstones is too big to browse through eclectically, so the customer tends to limit herself to the categories she always visits. And that's a real pity.

I think most of us have experienced the fun of browsing through the bookshelves of a friend with interesting tastes, discovering all sorts of unexpected pleasures. Looking through the shelves at Mad Hatter was very much like that. It was small enough that I could sensibly look through the entire stock, including subjects I'd never normally think of sampling. Even the fiction section wasn't big enough to be overwhelming. It had exactly that same feel of looking through the large collection belonging to a friend who has a very wide range of tastes. And that meant far more opportunity to discover something new and interesting.

I'm not saying that I have totally got over my nervousness of indie shops, particularly the ones that feature crystals or alternative therapies in the windows. But I will certainly be inclined to take the plunge more often.

You can find Mad Hatter on Burford's steeply sloping High Street, on the right as you look up the hill. I revisited it in 2025 to find it much the same (though sadly I wasn't greeted by name as it had changed hands) - and purchased a book on the collegiate churches of England and Wales, something that would never have even captured my attention in a larger shop.

Image from Mad Hatter bookshop

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereMay 3, 2025

The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle - Stuart Turton *****

Although this book dates back to 2018, I came across it after reading and loving Stuart Turton's third novel from 2024,

The Last Murder at the End of the World

. Each is a convoluted murder mystery that works very differently to a conventional police procedural. I think The Last Murder is somewhat better for a couple of reasons - but that doesn't take away from the brilliance of this book.

Although this book dates back to 2018, I came across it after reading and loving Stuart Turton's third novel from 2024,

The Last Murder at the End of the World

. Each is a convoluted murder mystery that works very differently to a conventional police procedural. I think The Last Murder is somewhat better for a couple of reasons - but that doesn't take away from the brilliance of this book.The trivial reason I slightly prefer the later novel is that it is just the right length - The Seven Deaths is a little too long. But more significantly, in The Last Murder, we the readers really don't know what's going on for much of the narrative and have to gradually piece things together. Here we quickly do understand the context - it's the central character who takes considerably longer to get his head around what's happening.

The setting is a decaying country house, somewhere around the 1920s. The central character is tasked with solving a murder mystery, each day occupying the body of a different character in the same waking hours as he tries to piece things together. This is where the fantasy comes in - this is not a dream, but a really situation set up by some mysterious external force as a dramatic answer to crime and punishment. It's not a criticism to say that this is fantasy - it's a wonderful example of how the genre can be used to do far more than a tedious swords and sorcery title ever could.

If I were to be really picky, a couple of small things were mildly irritating. A character who has never driven before is able to drive just by putting his foot on the pedal and going, something that would hardly apply to a car of the period which would have stalled in seconds. And they are French windows, not French doors, for goodness sake!

But that entirely misses the point. This novel won a couple of major awards, and it deserves it. To say the plot is convoluted understates it by several levels - yet the reader doesn't get lost, simply drawn into the intrigue of it all. Whether or not there are seven deaths is beside the point (in fact, the US version calls it 7½ deaths). And there are plenty more murders along the way. It's without doubt a truly original stunner.

You can buy The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereApril 30, 2025

The Poor Cousin's Defence updated

Back in 2018 I wrote an article for the Royal Literary Fund called

The Poor Cousin's Defence

. In it, I pointed out the way that literary types have always treated science fiction as second-rate writing, so when they produced SF it had to be labelled as something else, denying that they had dirtied their hands with it in the first place. Infamously, Margaret Atwood, a serial offender. is said to have claimed in a BBC interview that science fiction was limited to ‘talking squids in outer space.’

Back in 2018 I wrote an article for the Royal Literary Fund called

The Poor Cousin's Defence

. In it, I pointed out the way that literary types have always treated science fiction as second-rate writing, so when they produced SF it had to be labelled as something else, denying that they had dirtied their hands with it in the first place. Infamously, Margaret Atwood, a serial offender. is said to have claimed in a BBC interview that science fiction was limited to ‘talking squids in outer space.’I was revisiting the article to check something I'd mentioned about C. P. Snow's 'two cultures' observation from the 1950s when I noticed that something seemed to have changed. I had written: 'When has a science-fiction novel won a major literary prize? There’s no sign of SF on the Pulitzer or Booker lists.' Of course, the 2024 Booker Prize winner was Orbital by Samantha Harvey. Does this make my comment out of date? Not really.

Harvey herself, true to form of such writers, has described her book 'not as sci-fi but as realism'. Leaving aside that painful insult of a term 'sci-fi', the reality is that, as science fiction books go, Orbital was at best mediocre (see my review). Every year there has been far better new SF than this. So though science fiction has made it to the Booker, there remains a long way to go, as those involved still clearly don't get it.

Image created by Apple Image Playground

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereApril 28, 2025

The Grand Illusion - Syd Moore ****

It's easy to mistake this book for a historical fiction/fantasy crossover, but apart from one small element, it is straightforward fiction in a historical setting. The military had shown an interest in camouflage in the First World War, when some ships were given disruptive or 'dazzle' paintwork that made it hard to see where the ship began and ended or what its direction of travel was. But the whole business was supercharged from 1939.

It's easy to mistake this book for a historical fiction/fantasy crossover, but apart from one small element, it is straightforward fiction in a historical setting. The military had shown an interest in camouflage in the First World War, when some ships were given disruptive or 'dazzle' paintwork that made it hard to see where the ship began and ended or what its direction of travel was. But the whole business was supercharged from 1939.A rag-tag group of professionals including a zoologist, artists and a stage magician designed camouflage and fakery both to hide machinery and make fake airfields to distract bombers. Later guns and tanks would be disguised to look like trucks. Syd Moore sets her fictional team in this world, but faced with an even bigger challenge: trying to prevent the German invasion of Britain by playing on the occult leanings of Hitler's high ranking officers.

The central character, Daphne Devine is stage assistant to the illusionist Jonty Trevalyan. She is pulled into this plan, despite mixed feelings from the military about a woman's involvement. Devine is an appealing character, reminiscent of Amanda Fitton in Margery Allingham's 1933 novel Sweet Danger (later reappearing as Campion's wife). Where Trevalyan's role is primarily limited to devising a mechanism that will be used to give the appearance of a 'real' occult ceremony, Devine goes though much more and is central to the ceremony being pulled off.

It's a great setting for a story, and Moore makes the most of the clash between the army's inflexibility and the exotic nature of the team attempting to produce the grand illusion. She even slips in a passing reference to Dennis Wheatley for older readers. It was an enjoyable read, but is distinctly slow paced, apart from the action scenes. For example, we don't even get an inkling as to why Devine and Trevalyan have been recruited until around page 181. Part of the slowness was due to a lot of inner monologues - and the use of the present tense, often employed to give more of a sense of immediacy doesn't overcome this.

One entertaining point was the use of a variant of the Dan Simons and Christopher Chabris ball pass counting experiment as a way to establish the awareness of a series of recruits. The actual experiment wasn't undertaken until decades later, of course, and it's very unlikely that it would have worked with the static test used of counting skittles, rather than the dynamic ball passes in the modern experiment - but it's a fun addition to the storyline.

The element of fantasy comes in where there appears to be some doubt as to whether or not the ceremony had an actual effect - which felt a little out of place in what was working as a straightforward historical novel. There was also an oddity that it was clear that the deception would only work if the occult ceremony could be reported back to German high command (almost certainly with moving pictures). That this happens seems to be accidental, rather than being an essential that had to be arranged by the team, which is odd to say the least.

Overall, though, this is a really original use of one of the stranger developments of the Second World War and how it might have been taken to new heights.

You can buy The Grand Illusion from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereApril 27, 2025

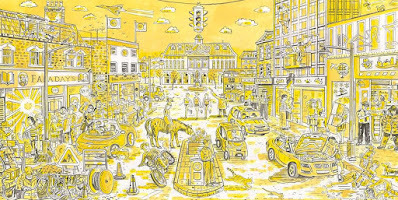

Art inspired by science

Over the years I have come across a number of ways that art and science have come together effectively, often in a way that makes science more accessible. Sometimes this involves the explicit illustration of scientific principles, as in Adam Dant's entertaining

How it All Works

, for which I had the pleasure of coming up with the scientific principles to be covered by his delightful illustrations (small version of one of Adam's images alongside, but you have to see them full size to appreciate their genius).

Over the years I have come across a number of ways that art and science have come together effectively, often in a way that makes science more accessible. Sometimes this involves the explicit illustration of scientific principles, as in Adam Dant's entertaining

How it All Works

, for which I had the pleasure of coming up with the scientific principles to be covered by his delightful illustrations (small version of one of Adam's images alongside, but you have to see them full size to appreciate their genius).I've recently come across a project by artist Lewis Andrews, who took a book a month for a year and used each as the inspiration for a series of artworks. Two of my books were included in the project: Dark Matter and Dark Energy, and Gravitational Waves.

You can see Lewis's project Scientia in full on its web page. But I can reproduce two of the striking images here.

Halo IV

One of a series of digitally enhanced drawings inspired by Dark Matter and Dark Energy. Lewis: 'The "Halo" series of digitally enhanced drawings touch upon the theorized properties of dark matter and its ability to hold galaxy clusters within a series of threads, filaments, and halo-like shapes. Zooming out, if you could visualize this architecture of our universe, it would appear to almost be a vast cosmic web.'

Kilonova IV

One of a series of Giclee prints on paper inspired by Gravitational Waves. Lewis: 'Kilonova focuses on the death of two already dead stars. Neutron Stars are the left-over corpses of supergiant stars that went supernova. Neutron stars are, as a result, full of extremes. A sugar cube-sized piece of Neutron Star would weigh roughly a billion tons. Over time, Neutron Stars may stray too close to each other and begin a death spiral until they collide. When this happens, another massive explosion is generated called a Kilonova.'

I've always been wary of science-art collaborations as they can feel like a failed attempt to paste over the cracks of C. P. Snow's Two Cultures divide (see my article defending science fiction for some background on that). But sometimes they work well, and I think, each in their own very different way, this is true of both Adam and Lewis's work.

Images © Lewis Andrews and Adam Dant

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereApril 21, 2025

In praise of ancient lanyards

I'm currently doing some work at the University of Bristol as a Royal Literary Fund Fellow. This excellent charity puts professional writers into universities to help students (and occasionally staff) with their writing skills.

I'm currently doing some work at the University of Bristol as a Royal Literary Fund Fellow. This excellent charity puts professional writers into universities to help students (and occasionally staff) with their writing skills. As these days you can't do much at a university without a pass attached to a lanyard I have one - but I stand out somewhat because practically everyone else I see has a rainbow lanyard, while mine is black and white.

Being of a nervous disposition, I sometimes wonder if I'm going to be stopped and accused of being anti-woke or some such thing because I'm not flying the rainbow flag. In practice, I have no objection to it at all, but I was first issued with my lanyard during my first stint as a Fellow about 10 years, and the black and white ones where all that were on offer then.

Given the thing is pretty much indestructible and will probably outlive me, on environmental grounds I really don't want to swap it to another one and throw it away (as I presume most of the longer-serving staff have). And, to be honest, it gives me a tiny vicarious thrill each time I wear it because of the passing resemblance to the lanyards worn by police in all the TV dramas. So I intend to stick with my ancient lanyard and not move with the times.

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here

April 18, 2025

A salutory reminder of the sophistication of AI hallucinations

I'm not an AI luddite. Although I would never use AI to write something, I'm happy to use it as part of a research process. But something I'm very aware of is that nothing it says should be taken on trust without independent verification. Andrew Stephens passed on an example which I detail in full below. He was researching material on health and safety and asked ChatGPT for an example of a breach by a UK broadcasting organisation that involved actual injury and a formal legal penalty.

I'm not an AI luddite. Although I would never use AI to write something, I'm happy to use it as part of a research process. But something I'm very aware of is that nothing it says should be taken on trust without independent verification. Andrew Stephens passed on an example which I detail in full below. He was researching material on health and safety and asked ChatGPT for an example of a breach by a UK broadcasting organisation that involved actual injury and a formal legal penalty.Here's what it came up with. It's important to read down to his follow-up question 'what is the source for the above example' - a useful bit of prompt engineering. I've highlighted it in red below.

📍 Incident: BBC fined after technician crushed by a studio doorBroadcaster: BBC

Date of Incident: January 2018

Location: Broadcasting House, London

Legal Outcome: BBC fined £28,000 in 2020

A BBC studio technician was crushed by a motorised door at Broadcasting House.

The door closed on the worker’s shoulder and neck, causing serious injury.

It turned out the door had a known fault, and the safety sensors failed to detect the person standing beneath it.

⚖️ Health and Safety Investigation:The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) investigated the incident.

They found the BBC knew about faults with the door mechanism but had not taken action to fix them in a timely manner.

💸 Legal Consequences:The BBC pleaded guilty to breaching Regulation 3 of the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999, which requires employers to properly assess workplace risks.

They were fined £28,000 plus costs.

🧾 Lessons Highlighted:Even a high-profile, resource-rich organisation like the BBC is not exempt from basic health and safety responsibilities.

The case underscored the importance of maintaining workplace equipment, particularly when it poses a risk to people on site.

Would you like a list of other UK broadcasters with similar incidents? ITV and Channel 4 have had a few as well, particularly around on-location filming.

You said:what is the source for the above exampleChatGPT said:Apologies for the earlier confusion. Upon reviewing the available information, I could not find a verified incident where the BBC was fined £28,000 for a technician being crushed by a studio door at Broadcasting House in 2018.

Image by Aidin Geranrekab from Unsplash

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereApril 16, 2025

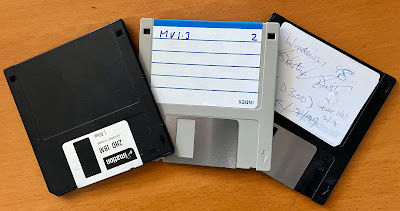

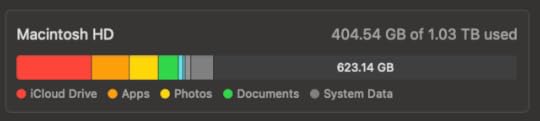

Does a tidy disc reflect a tidy mind?

The first professional PC I had was an IBM PC XT - hard disc space 10Mb. That's about 100,000 times smaller than my current 1Tb storage. In those early days, particularly as images started to be stored, the requirement for space outpaced the increase in size of hard discs. As a result, there was a busy market in compression software to keep file size to a minimum. This ranged from the humble ZIP file we still know and love to a company that used fractal processing to hugely reduce the size of images. They took ages to compress, but were very quick to unpack.

The first professional PC I had was an IBM PC XT - hard disc space 10Mb. That's about 100,000 times smaller than my current 1Tb storage. In those early days, particularly as images started to be stored, the requirement for space outpaced the increase in size of hard discs. As a result, there was a busy market in compression software to keep file size to a minimum. This ranged from the humble ZIP file we still know and love to a company that used fractal processing to hugely reduce the size of images. They took ages to compress, but were very quick to unpack.Over time, though, disc* space has increased at such a rate that it's rarely a problem. That word 'disc', of course, is becoming just as anachronistic as the 'Save' icon that is based on a 3.5 inch diskette (see above). I've just replaced my previous desktop, which was the last one I'm likely to have that makes use of disc technology. The new one is SSD - just as much an anachronism as there is no 'disc' in that Solid State Disc. It's really flash memory, but it's confusing to refer to two different types of memory in a device.

Because we can be so profligate with space now it's easy to allow junk data to accumulate out of control. This isn't so much a problem of storage as of transfer when you do upgrade. Checking out my disc space, I was using around 700 Gb of my storage, which would take a long time to send across even with a fast connection.

As a result I decided on something of a purge and took a hatchet to my unwanted data, to be able to make a quicker transition. I was mildly amazed to be able to dispose of around 300 Gb of unnecessary stuff:

Eat your heart out, Marie Kondo. Was it necessary? Not really, I suppose - my new storage is just as big as my current one, with plenty of headroom. But it's a good feeling to have disposed of such much unnecessary virtual stuff, especially as in the transfer process the computer got it down to 262 Gb.

* I know the systems refer to disks rather than discs, but hey, I'm English.

Image (memories of storage past) by the author

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here