Brian Clegg's Blog, page 4

June 16, 2025

The joy of covers

Authors have mixed relationships with book covers. Some publishers give us full right of veto on what a cover looks like, others simply show us what it's going to be. Some covers are great - others are, frankly, dull. There have been covers I treasure (for example, when I was still writing business books, the Spanish translation of my book Capturing Customers Hearts took the title literally, featuring a scarred chest with the heart removed), while others I'd rather ignore.

Authors have mixed relationships with book covers. Some publishers give us full right of veto on what a cover looks like, others simply show us what it's going to be. Some covers are great - others are, frankly, dull. There have been covers I treasure (for example, when I was still writing business books, the Spanish translation of my book Capturing Customers Hearts took the title literally, featuring a scarred chest with the heart removed), while others I'd rather ignore.It is also possible to be misled by the appearance of covers on well-known online bookshops. I've recently had published a book called Navigating Artificial Intelligence - a highly-illustrated overview

book that gives you (I hope) a good introduction to the topic and its significance: and let's face it, there isn't much that is as significant as AI at the moment. To go along with some fun illustrations inside (who wouldn't want to see a dog dressed as Henry VIII?), the cover is impressively striking, if perhaps a little busy. It's not entirely clear from the selfie above, but the cover features the kind of fluorescent orange that makes you reach for the sunglasses.

book that gives you (I hope) a good introduction to the topic and its significance: and let's face it, there isn't much that is as significant as AI at the moment. To go along with some fun illustrations inside (who wouldn't want to see a dog dressed as Henry VIII?), the cover is impressively striking, if perhaps a little busy. It's not entirely clear from the selfie above, but the cover features the kind of fluorescent orange that makes you reach for the sunglasses.But take a look at the book on Amazon (left) and, while it's still eye-popping it's now a deep pink (the little known Deep Purple/Pink Floyd crossover cover band). Then pop over to Bookshop.org (right) and there's yet another version, this time also pink but with different colours elsewhere, including a brain that pretty much obscures the title.

I suspect what tends to happen is that publishers set up listings in online bookshops before the final cover has been printed and forget to make changes. Incidentally, there's also distinctly dodgy content in the Amazon listing which says 'Review' and then has a quote from Alain de Botton: 'He still manages to surprise me with something new on every page'. While this is indeed something de Botton said in a review of one of my books, it was

Inflight Science

, not this one.

I suspect what tends to happen is that publishers set up listings in online bookshops before the final cover has been printed and forget to make changes. Incidentally, there's also distinctly dodgy content in the Amazon listing which says 'Review' and then has a quote from Alain de Botton: 'He still manages to surprise me with something new on every page'. While this is indeed something de Botton said in a review of one of my books, it was

Inflight Science

, not this one.They say 'Don't judge a book by its cover' - but sometimes it's hard not to. Personally, though, if it's an author I like, I pretty much ignore the cover... which in some cases it's just as well.

You can get Navigating Artificial Intelligence from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free herePandora by Holly Hollander - Gene Wolfe ****

This is a real oddity - in my quest to re-read my Gene Wolfe collection and review the books I hadn't covered so far, I'd mentally pigeonholed this 1990 book as urban fantasy, but it's actually a murder mystery. Being Wolfe, things aren't as straightforward as you might imagine, though. The book is allegedly written by the seventeen-year-old Holly, just edited and smartened up by Wolfe.

This is a real oddity - in my quest to re-read my Gene Wolfe collection and review the books I hadn't covered so far, I'd mentally pigeonholed this 1990 book as urban fantasy, but it's actually a murder mystery. Being Wolfe, things aren't as straightforward as you might imagine, though. The book is allegedly written by the seventeen-year-old Holly, just edited and smartened up by Wolfe.It's set in the 1980s, but the feel of the place (and this teen's viewpoint) is very much not post-punk - it's more like something from the Mad Men era. Trivial example: Holly and her friends never cuss (as she would probably put it). Like Castleview this is a slice of small town American life, but here seen through the eyes of a young would-be author.

The Pandora reference is to a mysterious box, to be opened at the town fair, with a prize if anyone guesses what's in it. At this point there's a sudden transition to murder mystery, with Holly both injured and acting as amateur sleuth, assisted by her new friend, the unlikely-named Aladdin Blue a twenty-something who styles himself a criminologist as (having been to jail) he can't be a private eye.

Although some of Holly's writing is cringe-making, she can be refreshingly blunt and bitchy, for example describing the sister-in-law of her best friend as follows: 'Basically what she had was one of those thin poor-li'l-me hillbilly faces, with lots of yellow hair as puffy as cotton candy (and sticky, too, I'd bet) piled up on top, and a shape like a sack of grapefruit.'

The mystery is suitably convoluted in what's probably best described as a long novella, and though Aladdin Blue is a little too capable, the indirect approach of making this Holly's book works pretty well, if you bear in mind she may not always be an entirely accurate witness.

You can buy Pandora by Holly Hollander (used on paper but still on Kindle) from Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereJune 11, 2025

Why I don't use OpenOffice revisited

REVISIT SERIES - An updated post from June 2015

REVISIT SERIES - An updated post from June 2015Recently (this is 2025 recently), I moaned on X and Bluesky about the bizarre way that Word (the word processing software - and doesn't the term 'word processing' look old fashioned?) was incapable of opening earlier versions of its own files. Science/SF writer John Gilbey responded 'Go directly to LibreOffice,' as apparently it's extremely accurate for opening old formats. This may be true, but the concerns from 10 years ago below about OpenOffice would also apply. It may be IBM's old weapon of FUD (fear, uncertainty and doubt) in action, but I am still wary of abandoning Word because of the usual interplay with the vast majority of publishers and magazine which do still use that software.

Broadly speaking, most professional writers either use Word or a specialist program like the much-praised Scrivener, which is apparently excellent for fiction work. However, every now and then, someone asks me 'Why do you spend all that money on Office, when you can get OpenOffice for free - and you can just export a Word file when you need it?' (For that matter, as a Mac user, I could use the excellent free Pages app that comes with it.)

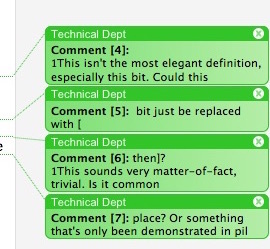

People have been saying this kind of thing to me ever since I ran the PC department at British Airways, and my answer has always been the same. If all you are doing is handling lightly formatted text, cheap and cheerful is fine, but as soon as you use the more sophisticated aspects of a word processing program, this kind of transfer becomes risky, and simply isn't worth it.I've just had a good example of how things can go wrong using OpenOffice. I was sent a document to check as an ODT file - the file format from OpenOffice. It had a series of appended comments. The file doesn't open in Word or Pages, but I tried it in both Google Documents and Textedit and neither showed the comments. No problem - the person who produced it exported a Word document from OpenOffice for me. And, yes, it did have comments - but they had been bizarrely scrambled. The image above shows some of the actual comments, rendered utterly unreadable - and none of them pointed to the right bit of body text. It was garbage, pure and simple. (Incidentally, I deny writing something 'very matter of fact, trivial'...)

In the end, I had to download a copy of OpenOffice and work on the original with that. As it happens this was fine, because it was this way round - OpenOffice happened to be the standard used by the company I was doing some work for. But almost all publishers, magazines etc. expect material in Word format. And if you are working in OpenOffice, you will have to export your document to Word. Potentially with the kind of result I just experienced.

By all means use OpenOffice for printed documents, or those for internal use. But if you intend to share anything more sophisticated than straightforward text with a publisher, say, in a professional capacity, then think twice about turning up your nose at Word.

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereJune 8, 2025

Castleview - Gene Wolfe *****

Having recently covered Adam Roberts'

Fantasy: a short history

, I became aware I'd never reviewed some of my favourite fantasy books. I'm starting with one of Gene Wolfe's masterpieces, Castleview, first published in 1990. This is a booked that is steeped in a particular small town America with a strong mid-twentieth century atmosphere - I can't think of another fantasy novel that does this so well apart from Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes.

Having recently covered Adam Roberts'

Fantasy: a short history

, I became aware I'd never reviewed some of my favourite fantasy books. I'm starting with one of Gene Wolfe's masterpieces, Castleview, first published in 1990. This is a booked that is steeped in a particular small town America with a strong mid-twentieth century atmosphere - I can't think of another fantasy novel that does this so well apart from Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes.We are plunged straight into this when a new family is viewing a house for sale in the town of Castleview. From the very beginning, the cosy, folksy setting clashes with events - a death, the mysterious viewing of what may or not be a ghost castle, a dark horseman nearly causing a car crash - Wolfe piles on the mysterious events while maintaining a small-town-USA vibe. It is masterfully done. Practically every chapter ends with a notching up of the mystery level and tension.

It's a thankfully short book (I really can't be doing with brick-style fantasies, with the inevitable exception of Lord of the Rings): despite having read it at least four times before, I had to keep going to the end as soon as I could. The otherworldly intrusion is a magnificent hotchpotch of English and Irish folklore, including Arthurian legend, where Wolfe has clearly enjoyed piling in everything he can possibly think of.

Only two small moans. There are a couple of foreign accents that these days might be thought a little lacking in political correctness, and Wolfe often has endings that don't entirely satisfy, as he tends not to tidy everything up, though this one does have a fairly clear ending. But neither of these gets in the way of the book's appeal.

You can buy Castleview (used on paper but still on Kindle) from Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com - it's appalling this isn't still in print.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereJune 2, 2025

TANSTAAFL revisited

REVISIT SERIES - An updated post from June 2015

REVISIT SERIES - An updated post from June 2015The other day I got a piece of junk mail that made a bit of a change from SEO and diet supplements: 'THE FIRST FREE ENERGY GENERATOR' it proclaimed, and just to rub it in, 'Humiliates top scientists.'

Well, there's nothing I like better than humiliating top scientists* and what's more, apparently this energy generator 'violates all the laws of physics', which is even more fun. So what would this involve? If you look up 'free energy generator' on Google you'll find lots of examples claiming to be just this - but overall it is a worrying concept.The obvious problem is conservation of energy, one of the most fundamental aspects of physics. You have to be a little careful with conservation of energy - it does require a closed system, and we patently don't live in a closed system, so it's easy enough to get 'free' energy in the sense that the Sun is pumping vast quantities of it in our direction and doesn't expect to be paid for it. Similarly, a 'free energy generator' could just be a way to steal energy from someone else. It's perfectly possible to light a fluorescent strip light by earthing it near a high voltage power cable - but you aren't producing energy from nowhere, you are just acquiring (to put it euphemistically) a small amount from the power company. Which they probably aren't too enthusiastic about.

However, the kind of 'free energy' device being advertised in the spam is usually supposed to get energy from nowhere, so we are indeed talking breaking conservation of energy - and you might as well throw in perpetual motion, because the one implies the other. And that's a bit worrying because things have to come from somewhere... so where is the energy coming from? (You could also get a bit excited about the great German mathematician Emmy Noether's proof that conservation of energy was equivalent to symmetry in time, but that's probably too subtle to be useful here.) Energy conservation isn't always obvious, because energy can change forms and so become apparent where it wasn't obvious before - but in the end, this has to be one of the best established and easiest to support natural laws. At the point, supporters of the concept would probably bring in zero point energy - but the whole point of that is you can't get less, and if you were somehow to extract it, that's what you would be doing.

More dramatic still is the claim that this device violates ALL the laws of physics. I can't even begin to imagine what something that did that would be like. Of course, the concept of 'physical laws' is somewhat fuzzy. It dates back to a time when it was assumed that God was in charge and these were the laws he laid down. A law requires the same thing to always happen in the same circumstances - in practice this can never be proven, but is a good assumption. However if all physical laws are broken, it would seem likely that the universe as we know it would fall apart, which doesn't sound too healthy. I'm not sure free energy is worth that consequence.

In the end, I refer the con persons behind the email to that classic science fiction writer, Robert Heinlein who regularly pointed out TANSTAAFL. This may sound like a shouty Scandinavian delicacy but in reality is: 'There ain't no such thing as a free lunch'.

* Actually there are plenty of things I like better than humiliating top scientists, this was just rhetoric.

Image from Unsplash by Mary Borozdina. I have no idea what a free energy generator looks like (it certainly wouldn't look like this) but it seemed to me the kind of thing a props department might use for one.

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereMay 31, 2025

Creativity and Gene Wolfe

About thirty years ago, I wrote a book on business creativity with my friend Paul Birch. We wanted to make the book format itself innovative - part of this involved incorporating sidebars with many asides, further reading, suggestions and more. But also we finished each chapter with a short piece of fiction, because we both believed that reading fiction was important to help business people be creative.

About thirty years ago, I wrote a book on business creativity with my friend Paul Birch. We wanted to make the book format itself innovative - part of this involved incorporating sidebars with many asides, further reading, suggestions and more. But also we finished each chapter with a short piece of fiction, because we both believed that reading fiction was important to help business people be creative.This didn't work for everyone. The British Airways chairman at the time, Sir Colin Marshall, who gave us a cover quote, told us that he didn't like having the stories. But some did appreciate them.

Some of these stories we wrote ourselves. Others were out of copyright - for example wonderfully witty extracts from Lewis Carroll's Hunting of the Snark and Jane Austen's Northanger Abbey, where she breaks the fourth wall delightfully. But I also wanted to include a short story by my favourite fantasy writer, Gene Wolfe - and knew just the one, a short short called My Book, where the apparent author explains how he decided to write his book backwards, first writing the last word, as that's the most important word in the book. He chooses to end with 'preface', then before that 'begin' to emphasise the process (technically there's a 'the' between them, but artistic licence) - and, beautifully, the story itself ends this way.

After a little time discovering the right person to write to (this was before the internet was any help), I received two letters from Gene Wolfe, which I would like to reproduce here. They are both typewriter carbons - I was writing on a PC but, at this stage at least, he was still old school. The first was his very polite response to my request:

And the second was when he was in receipt of a copy of the finished book:

I know he was just being polite, but I treasure those letters.

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereMay 28, 2025

How not to write Popular Science

I get sent many popular science books to review, a very small percentage of which are self-published (never one based on the author's 'new theory'). A recent example was, for me, an object lesson in the pitfalls of writing science for the public, most of which apply whether you are DIY or with a mainstream publisher. (In fact, some big names, particularly academic publishers, provide very limited editing these days.)

I get sent many popular science books to review, a very small percentage of which are self-published (never one based on the author's 'new theory'). A recent example was, for me, an object lesson in the pitfalls of writing science for the public, most of which apply whether you are DIY or with a mainstream publisher. (In fact, some big names, particularly academic publishers, provide very limited editing these days.)Note, by the way, I am not talking about quality of writing here. A starting point is having a good narrative and making your writing engaging and readable. That's a given. But this is more about the content that is presented in the book.

There was one issue that was specific to self-publishing: make sure there are no layout oddities. Appearance is as important as fixing typos. This particular book had a first paragraph in a smaller font that the rest of the text (as well as a couple of spurious bursts of italics, finishing part way through a word). More generally applicable, the author was a medical doctor and used 'Doctor X Y' as their author name. I strongly recommend not doing this - many popular science writers have doctorates, but very few use the title in their author name - it just looks tacky. (It's even worse if, say, you are writing about physics but are a medic.)

The book covered a phenomenon that could have a physical cause, could be purely psychological or simply the result of lying (or any combination of the above) - important to know, as we will see, when looking at a survey that was central to the story. A first content lesson is that it's really important to present numbers in an easily-followed way - if there is some oddity in the statistics, for example, then it needs to be carefully explained. In the survey, 50% of the studied population had a particular experience, but 75% of the population had a subset of the experience. This clearly can't be literally true - it turned out to be because the survey was not particularly well worded, and a fair number of participants didn't realise that the second type of experience was just one example of the first.

It's also important only to state what can be logically deduced from a study. In this case, the author assumed because 200 experiences were described in the survey, there must be a physical explanation. Unfortunately, as suggested above, this is a false deduction. The fact that 200 people described subjective experiences does not mean that there anything physical happened - far more evidence than a self-reporting survey is needed to be able to make this deduction. It does mean there is something to investigate - but does not give any direction on what that might be.

We next hit on problems with probability. This is never an easy subject to deal with - if it's outside your personal area of expertise, then it's always worth getting expert guidance. The author works out an incredibly small likelihood of something happening by chance. Unfortunately, in doing so, she hits two familiar probability pitfalls. The first is of dismissing an occurrence as too unlikely to be coincidental when it happens to a specific person, where the relevant probability was the likeliness of it happening to anyone. It's a bit like saying the probability of me winning the lottery at 16 million to one is almost zero - but the reality is that someone wins most weeks. Similarly, I've more than once bumped into someone I know in a different country from the one where we both live. The probability of both that specific person and me being in that place at that specific time is ridiculously small. But the chances of such a chance meeting happening at some time is large.

The second probability error is the probability equivalent of the false deduction from the survey: the false dichotomy. The author mentions p values - the probability of something happening if the null hypothesis applies. But it's essential to remember that this is not the probability that your hypothesis isn't true. If it's very unlikely that there is no cause for something occuring, it doesn't mean that your theory for what that cause is happens to be true. Again, I'm not saying there isn't something worth investigating further, but there is no evidence by suggesting the null hypothesis is unlikely that your preferred reason is correct.

Later on we get some physical science, but unfortunately the author has limited knowledge of physics and gets enough wrong to make the whole proposition open to doubt. We are told that humans 'generate 25 watts per second in our brain alone'. Unfortunately a watt is a measure of energy per second already, so 'watts per second' is meaningless unless we're talking about a rate of change. Also, the brain doesn't generate 25 watts of electrical power, it consumes about 20 watts, not all of which will be translated into electrical energy. We are also told that neurons have a 'negative electrical charge at rest of minus 70 millivolts/millimetre.' Leaving aside voltage not being a measure of charge, we are told this is equivalent to 14 million volts per metre, which makes it more powerful than lightning. Even if the numbers were correct, this is highly misleading, both because the neuron's potential of 70mV isn't measured across a millimetre, and because you can't multiple the potential difference up meaningfully in the way it was done here.

A final major issue is the haphazard use of studies to back up a theory. Bearing in mind we are dealing with a topic that could both involve physical and psychological effects, there is no mention of the replication crisis in psychology and plenty of use of psychology studies going as far back as the 1970s. Some of these have been thoroughly discredited (particularly where physicists were trying to work outside their own field) and others have repeatedly failed to reproduce. There was a time when even high profile popular science titles (for example Daniel Kahneman's Thinking Fast and Slow) could get away with using studies from the swamps of pre-2012 psychology that would later prove unreproducible, but that should no longer be the case.

Some insist that an author should be an expert in the field they are writing a popular science book about. I disagree (I would have to, given the range of books I've written) - but if you are stepping outside your areas of expertise, you do need to be extremely careful about these kind of issues if you are to produce a title that does justice to the topic and doesn't mislead the reader.

Image from Unsplash by Eliott Reyna.

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free hereMay 27, 2025

Pass the buck sustainability revisited

REVISIT SERIES - An updated post from May 2010

REVISIT SERIES - An updated post from May 2010'Sustainable' is a word you hear banded about a lot these days. As I described in Ecologic, it's a term that is often used because it sounds good, without thinking through what it really means.

There are broadly two possible meanings, sustainable lite and full-fat sustainable. Sustainable lite means something that's viable to continue operating. It makes economic sense, it is obtainable and there's a continued demand for it. If any of those three conditions don't apply it is no longer a sustainable activity. Full-fat sustainable is what is usually implied in the environmental usage of the word. Here it means something that can operate without external inputs that will run out, or negative environmental impact. So, for instance, a sustainable farm should be able to operate without bringing in fertiliser and other inputs. A sustainable house should be 'zero energy' requiring no energy input from the grid.Unfortunately, all too often, people try to give the impression of having full fat sustainability by sleight of hand. They try to make it look as if they are truly sustainable, while passing on the problems to someone else. There was a great example of this in the news recently. The Register reported on a 'zero energy' house that was anything but. This California building had won awards for its sustainability. Yet this was no hut in the woods, depending on burning willow twigs - it was a big modern construction ablaze with power.

So how did they acheive this? Vast solar panels, wind turbines and banks of energy stores? Nope. By not including the use of natural gas in their zero energy calculations. When the gas usage was taken into account, the house used more fossil fuel energy than an average house in the area. Hmm.

Organic farms play similar tricks to claim to be sustainable, though they do it more subtly. The fact is, an organic farm can't be fully sustainable because it has matter going out (the food produced) so needs something coming in to replace that matter. Some of it, admittedly, can come from the air. Carbon, for instance, from carbon dioxide and a certain amount of nitrogen from the air too by using plants like clover that 'fix' nitrogen. There's water from rain as well. But that doesn't provide everything that's needed.

Nitrogen, for example, comes in part from manure. But that just shifts the nitrogen input to the animals' feedstuff where not enough can be got from nitrogen fixers. (Incidentally it also means that organic farms pretty well have to be mixed farms to produce that manure, so they can't take the true green route and do away with greenhouse gas belching meat animals.) So organic farms buy in nitrogen-rich feed from other organic farms. But of course that means those farms become depleted of nitrogen. And at some point the buck has to stop.

One of the tricks used at this point is to buy straw from a conventional farm. This is allowed, because it's bedding, not food, so it's okay that the nitrogen has come from a nitrogen fertiliser. But, of course, the animals don't know it's bedding. They eat it, gain the nitrogen, and the 'sustainable' organic system can pretend it never got nitrogen from artificial fertilisers.

There's even worse fiddling of the books to get in important trace elements like potassium. Such is the organic movement's aversion to 'chemicals' they will go wildly out of their way to use something that sounds natural, even though it's a much less effective source than many alternatives. All trace elements are chemicals, guys. Get over it. More to the point here, they all have to be brought in. They can't be produced from the air. A farm can't be sustainable in minerals.

There's nothing wrong with calling an organic farm sustainable lite - but it can never be full fat sustainable. Sustainability is an excellent goal, but playing a game of 'find the lady' to conceal your inputs (especially as ineptly as was the case with the zero energy house) discredits the term.

This has been a Green Heretic production. See all my Green Heretic articles here.

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here

May 20, 2025

The joys of green driving - early days

It's early days using a plug-in hybrid, but after a holiday trip to Cornwall I now have some experience of commercial chargers, though admittedly a small sample. When at home I always charge there - my electricity costs about half the rate per mile of petrol. Looking at commercial chargers, moderate ones (or those at friendly locations) are similar to petrol, while fast chargers can be up to twice the petrol price.

It's early days using a plug-in hybrid, but after a holiday trip to Cornwall I now have some experience of commercial chargers, though admittedly a small sample. When at home I always charge there - my electricity costs about half the rate per mile of petrol. Looking at commercial chargers, moderate ones (or those at friendly locations) are similar to petrol, while fast chargers can be up to twice the petrol price.For this reason I thought I wouldn’t bother to charge before the return journey, as there wouldn't be a financial advantage, but in reality, travelling the 223 miles down to Gwithian, I found the cleverness of the hybrid mode meant that I got significantly more miles per gallon/kWh than I would on petrol alone. As a result I had four attempts at charging in Cornwall, of which two were successful.

The first one seemed perfect. It was at a location we were staying several hours, at a rate a little cheaper than petrol. I plugged in, started a charge on the app… and nothing happened. Ringing the support number, I was told there was a hardware fault, but they only looked after the software, so there was nothing they could do but cancel.

A couple of days later I was catching the delightful little train that shuttles between St Erth and St Ives. According to the apps, it had four chargers at a reasonable rate - again, ideal to leave the car and let it get on with its thing. When we got there, the four chargers had all disappeared (you could see where they were in the app photos and they aren’t any more.) Instead there was a single charger (admittedly faster), but with a nearly twice petrol rate - and you couldn’t access it without an obscure app I didn’t have and couldn’t be bothered to download. Result - no charging.

I was so frustrated at this point that when I topped up with petrol before the return journey, I added some charge at a Shell Recharge. Ridiculously expensive, but very easy to use (no app needed) and fast.

Finally, we called over at a National Trust house (Killerton) on the way back. This seemed ideal. Chargers in a preferential parking location, cheap, again no app required and l would get a good charge while we looked around. When I got back I terminated the charge… and the charger refused to release the cable. I had to ring the support number (that’s 2 cases out of 4). Thankfully they could reboot the charger, which let me unplug.

As a plug-in hybrid user, I’m far less susceptible to range anxiety than a pure electric driver. I have to say, that my experience so far suggests the charging network is not yet ready for large scale use, particularly when you are a little off the beaten track.

Image from Unsplash by Zaptec

This has been a Green Heretic production. See all my Green Heretic articles here.

These articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:

See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here

May 14, 2025

Fantasy: a short history - Adam Roberts *****

If you have an interest in fantasy books, or where they came from, this is a must-read title. It’s not a popular history of the genre: this is Adam Roberts in professorial mode. He doesn’t make it too easy for the reader - for instance, in a section on Arthurian fantasy, he several times uses segments of ‘Rex quondam, rex futurusque’ without any explanation, and is perhaps unnecessarily liberal with academic lit crit terminology (though there is also the odd ‘Boing!’). As such, I’m probably not the ideal audience, but I still got a huge amount out of it.

If you have an interest in fantasy books, or where they came from, this is a must-read title. It’s not a popular history of the genre: this is Adam Roberts in professorial mode. He doesn’t make it too easy for the reader - for instance, in a section on Arthurian fantasy, he several times uses segments of ‘Rex quondam, rex futurusque’ without any explanation, and is perhaps unnecessarily liberal with academic lit crit terminology (though there is also the odd ‘Boing!’). As such, I’m probably not the ideal audience, but I still got a huge amount out of it.The structure is broadly chronological, though there are occasional thematic leaps forward in time, with the paradigm shift coming post-war when the Lord of the Rings and its endless league of copycat stories changed the way fantasy was handled (though Roberts doesn’t ignore, for instance, Paradise Lost, the genius of Lewis Carroll or now largely ignored earlier fantasises such as The Water Babies). Although the strong British or European influence is obvious in much fantasy, apart from obvious allegory, such as in the Narnia books, I wasn’t aware how much Christian influence there was (including, of course, on Harry Potter - humorous given the anti-witchcraft backlash it received in some parts).

Inevitably in a book like this there will be plenty of omissions, including, I suspect, many readers’ pet titles. Roberts explicitly points out this is a short history (though this doesn’t mean it’s shallow), not a comprehensive encyclopaedia. However, I do think there is one significant omission, which is to my mind the best of fantasy - where it’s set in the ordinary, everyday world. (I refuse to use the term ‘magical realism’ which seems to me the same kind of weasel words as calling science fiction ‘speculative fiction’.) It’s not entirely omitted. There is reference, for example, to the wondrous Mythago Wood, but this does mean we miss out on so much.

For example, we don’t get Ray Bradbury’s beautiful Something Wicked This Way Comes. There is no mention of Robert Rankin. Although Alan Garner is included, no mention of his real world fantasy masterpiece, The Owl Service. When venturing into TV, we get the inevitable Game of Thrones, but not the ultimate TV fantasy show, Buffy the Vampire Slayer. And though Gene Wolfe gets a short section, it is only for his Sword and Sorcery ‘New Sun’ books, not the (to my mind) much better real or mixed world fantasies such as There are Doors (only a passing reference as a portal book), Free Live Free, Castleview and so on. And then, of course, we miss out on the hugely successful fantasy policing crossovers such as the Rivers of London series. A real shame.

One other moan is that the book was poorly edited: a considerable number of typos slipped through. But that doesn’t take away from the excellence of what we do get. I learned a lot and found the book full of insights. Recommended for fantasy fans.

You can buy Fantasy: a short history from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to youThese articles will always be free - but if you'd like to support my online work, consider buying a virtual coffee or taking out a membership:Review by Brian Clegg - See all Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly email free here