Brian Clegg's Blog, page 135

September 5, 2012

Get real, car manufacturers

Here's one I inflated earlierLike, I suspect, most drivers I don't check my tyre pressures anywhere near frequently enough. (This is not helped by the assumption of everyone else in my family that it's my job to look after their tyres too.) But when I do, as I did this morning, I feel a strong urge to get hold of the car maker and shake them until they rattle.

Here's one I inflated earlierLike, I suspect, most drivers I don't check my tyre pressures anywhere near frequently enough. (This is not helped by the assumption of everyone else in my family that it's my job to look after their tyres too.) But when I do, as I did this morning, I feel a strong urge to get hold of the car maker and shake them until they rattle.Pretty well every car I've ever had has presented the driver with two different pressures, one for if you just have one or two people in the car, and one for when the car is full and so is the boot. As if anyone is going to modify the tyre pressure every time someone gets in the car. 'Sorry, Auntie Carol, you can't get in my car, I would need to increase the tyre pressure to cope with your weight.' It's just not realistic.

What I need is a sensible inflation level (in bars, please - get over this pounds per square inch nonsense) that will do in all circumstances. It might not be ideal, but that's life. Few things are ideal. Let's just be given a practical value and get on with things. Life is too short to have to guess an interpolated value between the two. I wouldn't mind, but at least one of the cars I deal with has identical pressures all round if you have 2 people in the car but widely differently pressures front and back for a full load.

Arggh! Send the motor manufacturers to the naughty step.

Next week - does it have to be so difficult to change a bulb?

Published on September 05, 2012 00:15

September 4, 2012

Boneland - Alan Garner

I loved Alan Garner's books as a teenager. And I'd still say that Elidor and The Owl Service are the best Young Adult fantasy books ever written for the younger and older ends of that spectrum respectively. I was also quite fond of his first two books, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and its sequel The Moon of Gomrath. They were also gripping fantasy adventures, and I loved the setting of Alderly Edge, which I knew quite well. Even at the time, though, I had slight reservations about them. So it was with some interest that I got a copy of Boneland, described as 'the concluding volume in the Weirdstone trilogy.'

I loved Alan Garner's books as a teenager. And I'd still say that Elidor and The Owl Service are the best Young Adult fantasy books ever written for the younger and older ends of that spectrum respectively. I was also quite fond of his first two books, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and its sequel The Moon of Gomrath. They were also gripping fantasy adventures, and I loved the setting of Alderly Edge, which I knew quite well. Even at the time, though, I had slight reservations about them. So it was with some interest that I got a copy of Boneland, described as 'the concluding volume in the Weirdstone trilogy.'My issues with the originals, which feature a circa 12 year old pair of twins hurled into a Cheshire setting with supernatural goings-on, were two-fold. I was already a huge Lord of the Rings fan and I couldn't help feeling that the svarts that the children discover down the copper mines are extremely derivative of the orcs in the Moria scene in LotR. I also felt that Garner flung in every tradition he could think of in a messy mix. So we had witches, King Arthur and his knights sleeping under the hill to rescue England at its peril, a wizard, the Wild Hunt and even a chunk of Norse mythology.

So what of the 'sequel'? First the good news. Boneland is an interesting book in its own right, I love the way Garner weaves in Jodrell Bank (visible from his house), and the character Meg is superb. Colin, one of the twins from the original books, now middle-aged, is less appealing (and, I'm sorry, but Garner got his surname wrong. It just sounds wrong.) But the claims on the cover are downright fibs.

Not only is there no way this is the concluding book of a trilogy - it has no similarity of feel to the first books - Philip Pullman's comments on the rear are highly misleading. He calls it a resolution of the stories of the first two books, and says those who were young when they came out (as he and I both were) 'won't be disappointed: this was worth waiting for.' Actually I was hugely disappointed. The first books didn't need a resolution: the apparent cliff-hanger that links them and Boneland isn't in the original books. And this is anything but a resolution. Let me try to explain why have problems with this book.

One is inconsistency. Having said that the original books were a real mish-mash of legends and traditions, at least there was some consistency of having a medieval English feel (with a touch of Scandanavian) to them. Apart from the use of crows, there is hardly any overlap with the mystical content of this book, which is all cod-Stone age. And there is so much of that. I really had to fight myself not to skip over the huge chunks of mystical waffle to get back to Colin and Meg, because it is deliberately obscure and unsatisfying.

It didn't help for me, and I know not everyone will agree, that it was cod-Stone age. I have real problems with this particular style. I found the same experience with Michelle Paver's Wolf Brother books. The thing is, if you use an existing legend - like the Wild Hunt - you are tying into a true tradition, and that gives a story real resonance. But we have no idea what Stone age religion was like (or even if they had any: it's all supposition). So people make guesses from cave paintings. But it always feels really false and strained to me. But most of all, as already mentioned, what we find here has nothing to do with the mythos of the Weirdstone books.

So, all in all, a disappointment. Not a bad book, by any means. But it doesn't do what it says on the tin.

You can see more on Boneland or buy a copy (if I haven't put you off - note I did say it was an interesting book in its own right) at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com.

Published on September 04, 2012 00:39

September 3, 2012

Nature's Nanotech #5 - Catching a Cure

Fifth in our Nature's Nanotech series

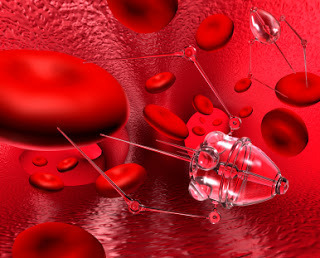

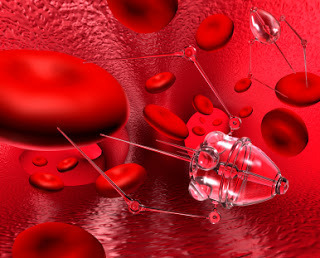

Isaac Asimov was a great science fiction writer, but even the best has his off days, and Asimov’s low point was probably his involvement with the dire science fiction movie Fantastic Voyage. Asimov wasn’t responsible for the story, but provided the novelization – and he probably regretted it. The premise of the film was that miniaturization technology has made it possible shrink a submarine and its crew down to around 1,000 nanometres, sending it into a man’s bloodstream to find and destroy a blood clot on his brain.

Along the way the crew have various silly encounters with the body’s systems – but strip away the Hollywood shlock and underneath is an idea that has been developed in a lot more detail by IT pioneer and life extension enthusiast Ray Kurzweil. Based on the idea of miniature robotic devices – nanobots – Kurzweil believes that in the future we will not have a single manned Proteus submarine as featured in Fantastic Voyage in our bloodstreams but rather a whole host of nanobots that will undertake medical functions and keep humans of the future alive indefinitely.

As we have seen in The Importance of Being Wet , the chances are that any such devices would not be a simple miniaturization of existing mechanical robots with their flat metal surfaces and gears, but rather would be based on the wet technology of the natural nanoscale world.

Among the possibilities Kurzweil suggests are on the cards are self-propelling robotic replacements for blood cells (this eliminates the importance of the heart as a pump, and hence the risk of heart disease), built in monitors for any sign of the body drifting away from ideal operation, nanobots that can deliver drugs to control cancer or remove cancer cells, and even miniature robots that make direct repairs to genes.

Among the possibilities Kurzweil suggests are on the cards are self-propelling robotic replacements for blood cells (this eliminates the importance of the heart as a pump, and hence the risk of heart disease), built in monitors for any sign of the body drifting away from ideal operation, nanobots that can deliver drugs to control cancer or remove cancer cells, and even miniature robots that make direct repairs to genes.

Kurzweil also expects we might separate the pleasure of eating from getting the nutrients we need, leaving the latter to nanobots in the bloodstream that release the essentials when we need them, while other nano devices remove toxins from the blood and destroy unwanted food without it ever influencing our metabolism. You could pig out on anything you wanted, all day and every day, and never suffer the consequences. (Given Kurzweil is notorious for living on an unpleasant diet to attempt to extend his life until nanotechnology is available, perhaps this is wishful thinking.)

If we are to develop this kind of nanotechnology, there are two aspects of nature that we will need to use as guides. One is to listen to the bees. Bearing in mind just how small a medical nanobot would have to be, even with the best developments in electronics the chances are it would have to be relatively unintelligent – yet it would need to achieve quite complex tasks. Bees are an excellent natural model for a way to achieve this.

A colony of bees achieves remarkable things in the construction and maintenance of its hive – yet taken as individuals, bees have very little capacity for mental activity. The realization that transformed our understanding of bees is that they form a super-organism. In effect, a whole colony is a single organism, not a collection of individual bees. A bee is more like a cell in a typical animal than it is a whole creature. By having appropriate mechanisms for communicating between the component parts – in the case of bees, using everything from chemical scent markers to waggle dances – relatively incapable individuals can come together to make a greater whole.

It would be sensible to expect something similar from medical nanobots at work in a human body. Individually they could not be intelligent enough to carry out their functions properly – but collectively, if they can interact to form a super-organism, they could operate autonomously without an external control mechanism continuously providing them with orders.

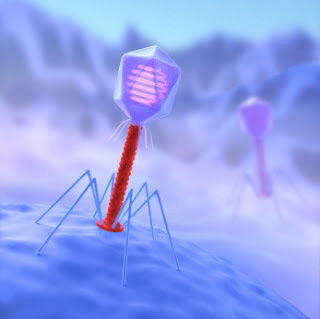

A second model for these miniature medics is a piece of natural nanotechnology that we usually regard as a bad guy – the virus. Viruses are very small – typically between 20 and 400 nanometres in size – and they lack many of the essential components of a living entity. However they are able to reproduce and thrive by using a remarkably clever cheat. Lacking the physical space to carry all the components of a living cell, they take over an existing cell in their host and subvert its mechanism to do their reproduction for them.

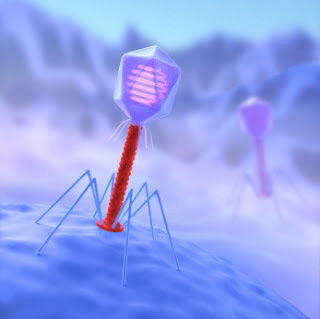

The particular class of virus that may be particularly useful as a model for medical nanobots is the phage. These are amongst the weirdest looking natural structure – some have an uncanny resemblance of the Apollo Lunar module: they actually look as if they are the sort of nanotechnology we might construct.

The particular class of virus that may be particularly useful as a model for medical nanobots is the phage. These are amongst the weirdest looking natural structure – some have an uncanny resemblance of the Apollo Lunar module: they actually look as if they are the sort of nanotechnology we might construct.

The word ‘phage’ is short for bacteriophage – ‘bacteria eater’. These are viruses than instead of preying on human cells – or those of any other large scale animals – attack and destroy bacteria. Because there are so many bacteria out there (even the human body has ten times more bacteria than human cells on board), their predators are also immensely populous and diverse. Phages may not be common fare on David Attenborough’s nature programmes, but they play a major role in the overall biological life of the Earth.

Because phages attack bacteria, they can be beneficial to human life. Throughout human existence we have been plagued with bacterial infections. (Literally – bacteria, for example, cause bubonic plague.) It is only relatively recently that antibiotics have provided us with a miracle cure for bacterial attacks – but that miracle is weakening. Bacteria breed and evolve quickly. There are strains of bacteria that can resist most of the existing antibiotics. But phages have the potential to attack bacteria resistant to all antibiotics. For a long time phage therapy was restricted to the former Soviet Union, but interest is spreading in making use of phages in medical procedures.

The biggest problem with phages is getting them to the right place. But medical nanobots based on a phage’s ability to attack or modify particular cells, combined with a super-organism’s ability to act in a collective manner would have huge potential. Modified viruses are already used to insert genetic payloads into cells – but the nanotechnology of the future, inspired by the phage and the bee, could see something much closer to Kurzweil’s vision.

Moving away from the medical, and from individual nanoscale elements, in the next installment of Nature’s Nanotech we will see how natural nanotechnology plays a role in silk and how fibres based on a nanotechnology structure could make rockets obsolete for putting satellites into space.

Images from iStockPhoto.com

Isaac Asimov was a great science fiction writer, but even the best has his off days, and Asimov’s low point was probably his involvement with the dire science fiction movie Fantastic Voyage. Asimov wasn’t responsible for the story, but provided the novelization – and he probably regretted it. The premise of the film was that miniaturization technology has made it possible shrink a submarine and its crew down to around 1,000 nanometres, sending it into a man’s bloodstream to find and destroy a blood clot on his brain.

Along the way the crew have various silly encounters with the body’s systems – but strip away the Hollywood shlock and underneath is an idea that has been developed in a lot more detail by IT pioneer and life extension enthusiast Ray Kurzweil. Based on the idea of miniature robotic devices – nanobots – Kurzweil believes that in the future we will not have a single manned Proteus submarine as featured in Fantastic Voyage in our bloodstreams but rather a whole host of nanobots that will undertake medical functions and keep humans of the future alive indefinitely.

As we have seen in The Importance of Being Wet , the chances are that any such devices would not be a simple miniaturization of existing mechanical robots with their flat metal surfaces and gears, but rather would be based on the wet technology of the natural nanoscale world.

Among the possibilities Kurzweil suggests are on the cards are self-propelling robotic replacements for blood cells (this eliminates the importance of the heart as a pump, and hence the risk of heart disease), built in monitors for any sign of the body drifting away from ideal operation, nanobots that can deliver drugs to control cancer or remove cancer cells, and even miniature robots that make direct repairs to genes.

Among the possibilities Kurzweil suggests are on the cards are self-propelling robotic replacements for blood cells (this eliminates the importance of the heart as a pump, and hence the risk of heart disease), built in monitors for any sign of the body drifting away from ideal operation, nanobots that can deliver drugs to control cancer or remove cancer cells, and even miniature robots that make direct repairs to genes.Kurzweil also expects we might separate the pleasure of eating from getting the nutrients we need, leaving the latter to nanobots in the bloodstream that release the essentials when we need them, while other nano devices remove toxins from the blood and destroy unwanted food without it ever influencing our metabolism. You could pig out on anything you wanted, all day and every day, and never suffer the consequences. (Given Kurzweil is notorious for living on an unpleasant diet to attempt to extend his life until nanotechnology is available, perhaps this is wishful thinking.)

If we are to develop this kind of nanotechnology, there are two aspects of nature that we will need to use as guides. One is to listen to the bees. Bearing in mind just how small a medical nanobot would have to be, even with the best developments in electronics the chances are it would have to be relatively unintelligent – yet it would need to achieve quite complex tasks. Bees are an excellent natural model for a way to achieve this.

A colony of bees achieves remarkable things in the construction and maintenance of its hive – yet taken as individuals, bees have very little capacity for mental activity. The realization that transformed our understanding of bees is that they form a super-organism. In effect, a whole colony is a single organism, not a collection of individual bees. A bee is more like a cell in a typical animal than it is a whole creature. By having appropriate mechanisms for communicating between the component parts – in the case of bees, using everything from chemical scent markers to waggle dances – relatively incapable individuals can come together to make a greater whole.

It would be sensible to expect something similar from medical nanobots at work in a human body. Individually they could not be intelligent enough to carry out their functions properly – but collectively, if they can interact to form a super-organism, they could operate autonomously without an external control mechanism continuously providing them with orders.

A second model for these miniature medics is a piece of natural nanotechnology that we usually regard as a bad guy – the virus. Viruses are very small – typically between 20 and 400 nanometres in size – and they lack many of the essential components of a living entity. However they are able to reproduce and thrive by using a remarkably clever cheat. Lacking the physical space to carry all the components of a living cell, they take over an existing cell in their host and subvert its mechanism to do their reproduction for them.

The particular class of virus that may be particularly useful as a model for medical nanobots is the phage. These are amongst the weirdest looking natural structure – some have an uncanny resemblance of the Apollo Lunar module: they actually look as if they are the sort of nanotechnology we might construct.

The particular class of virus that may be particularly useful as a model for medical nanobots is the phage. These are amongst the weirdest looking natural structure – some have an uncanny resemblance of the Apollo Lunar module: they actually look as if they are the sort of nanotechnology we might construct.The word ‘phage’ is short for bacteriophage – ‘bacteria eater’. These are viruses than instead of preying on human cells – or those of any other large scale animals – attack and destroy bacteria. Because there are so many bacteria out there (even the human body has ten times more bacteria than human cells on board), their predators are also immensely populous and diverse. Phages may not be common fare on David Attenborough’s nature programmes, but they play a major role in the overall biological life of the Earth.

Because phages attack bacteria, they can be beneficial to human life. Throughout human existence we have been plagued with bacterial infections. (Literally – bacteria, for example, cause bubonic plague.) It is only relatively recently that antibiotics have provided us with a miracle cure for bacterial attacks – but that miracle is weakening. Bacteria breed and evolve quickly. There are strains of bacteria that can resist most of the existing antibiotics. But phages have the potential to attack bacteria resistant to all antibiotics. For a long time phage therapy was restricted to the former Soviet Union, but interest is spreading in making use of phages in medical procedures.

The biggest problem with phages is getting them to the right place. But medical nanobots based on a phage’s ability to attack or modify particular cells, combined with a super-organism’s ability to act in a collective manner would have huge potential. Modified viruses are already used to insert genetic payloads into cells – but the nanotechnology of the future, inspired by the phage and the bee, could see something much closer to Kurzweil’s vision.

Moving away from the medical, and from individual nanoscale elements, in the next installment of Nature’s Nanotech we will see how natural nanotechnology plays a role in silk and how fibres based on a nanotechnology structure could make rockets obsolete for putting satellites into space.

Images from iStockPhoto.com

Published on September 03, 2012 00:47

August 31, 2012

Quark quandaries

Every now and then I think it's a good idea to dip into a basic aspect of physics that may not have been in the school curriculum. Take, for instance, the quark. I don't refer to the low fat cheese sometimes given this name but the particle at the heart of every atom in your body (and everywhere else for that matter).

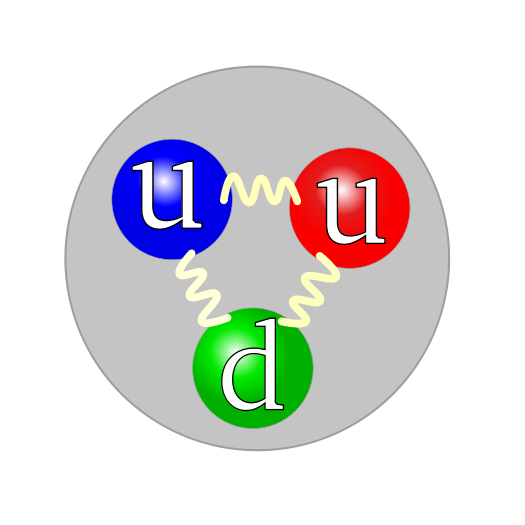

Proton structure

Proton structure

Once upon a time we talked about the basic particles in the nucleus in the middle of the atom being protons and neutrons. They haven't gone away, but they are no longer considered fundamental particles. Each is made up of three smaller particles – quarks. There’s a whole mess of quarks distinguished by characteristics known as flavors (no, really). The different flavors are charm, strangeness, top/bottom and up/down. (Even the more prosaic names can sound a bit odd with antimatter versions. One is the ‘anti-bottom quark.’) The proton is two ups and one down; the neutron two downs and one up.

Up quarks have a 2/3 charge and down quarks -1/3, resulting in a positive charge of 1 for the proton and no charge at all for the neutron. We aren’t used to nature coming up with quantities in thirds. But bear in mind the unit of charge is arbitrary. We really ought to say that up and down quarks have charges of 2 and -1 respectively – so a proton has a charge of 3 units – but because protons and electrons were the simplest particles known when the units were established we are stuck with thirds.

No one has ever seen a quark, nor broken a proton or neutron into its components. It is particularly difficult to do so, because the force that holds the quarks together gets stronger as they move further apart. As this is the case, it’s difficult to understand how quarks were ever dreamed up. The reason we believe that quarks exist owes its origins to a different type of physics that emerged in the early days of quantum theory.

As quantum theory was developed, two different approaches emerged. One had clear parallels in the real world. The second, matrix mechanics, was purely mathematical. It was by building on purely mathematical concepts, until they closely predicted what was seen in the real world, that the quark emerged. The existence of quarks themselves has since been indicated by experiments that show three constituents in a proton – and by the very short-lived production of otherwise unknown particles made up of combinations of different quarks. It’s possible things will go horribly wrong, and quarks will turn up not to exist – but it’s unlikely.

Although “quark” is usually pronounced to rhyme with bark, when American physicist Murray Gell-Mann came up with the name he wanted it to rhyme with dork. Gell-Mann says he used the “kwork” sound first without thinking about how to spell it, before coming across a line in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, which reads “three quarks for Muster Mark!” The way quarks come in threes made this line and the spelling very apt, but Gell-Mann wanted to keep his original pronunciation (Joyce clearly intended it to rhyme with mark).

Given all the fuss about the Higgs boson lately, there are some interesting observations to be made about the mass of quarks. Almost all the mass of atoms - and hence of you - comes from protons and neutrons. But the vast majority of has nothing to do with the Higgs field. Around 99 percent of the mass of those particles comes not from the intrinsic mass of quarks but from the energy coming from their movement and that of the gluon particles that hold them together. Thanks to Einstein we know energy and mass are equivalent, and though gluons are massless, the energy of the whole vibrant gluon/quark mix inside the protons and neutrons is experienced as mass. Bizarre or what?

Image from Wikipedia

Proton structure

Proton structureOnce upon a time we talked about the basic particles in the nucleus in the middle of the atom being protons and neutrons. They haven't gone away, but they are no longer considered fundamental particles. Each is made up of three smaller particles – quarks. There’s a whole mess of quarks distinguished by characteristics known as flavors (no, really). The different flavors are charm, strangeness, top/bottom and up/down. (Even the more prosaic names can sound a bit odd with antimatter versions. One is the ‘anti-bottom quark.’) The proton is two ups and one down; the neutron two downs and one up.

Up quarks have a 2/3 charge and down quarks -1/3, resulting in a positive charge of 1 for the proton and no charge at all for the neutron. We aren’t used to nature coming up with quantities in thirds. But bear in mind the unit of charge is arbitrary. We really ought to say that up and down quarks have charges of 2 and -1 respectively – so a proton has a charge of 3 units – but because protons and electrons were the simplest particles known when the units were established we are stuck with thirds.

No one has ever seen a quark, nor broken a proton or neutron into its components. It is particularly difficult to do so, because the force that holds the quarks together gets stronger as they move further apart. As this is the case, it’s difficult to understand how quarks were ever dreamed up. The reason we believe that quarks exist owes its origins to a different type of physics that emerged in the early days of quantum theory.

As quantum theory was developed, two different approaches emerged. One had clear parallels in the real world. The second, matrix mechanics, was purely mathematical. It was by building on purely mathematical concepts, until they closely predicted what was seen in the real world, that the quark emerged. The existence of quarks themselves has since been indicated by experiments that show three constituents in a proton – and by the very short-lived production of otherwise unknown particles made up of combinations of different quarks. It’s possible things will go horribly wrong, and quarks will turn up not to exist – but it’s unlikely.

Although “quark” is usually pronounced to rhyme with bark, when American physicist Murray Gell-Mann came up with the name he wanted it to rhyme with dork. Gell-Mann says he used the “kwork” sound first without thinking about how to spell it, before coming across a line in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, which reads “three quarks for Muster Mark!” The way quarks come in threes made this line and the spelling very apt, but Gell-Mann wanted to keep his original pronunciation (Joyce clearly intended it to rhyme with mark).

Given all the fuss about the Higgs boson lately, there are some interesting observations to be made about the mass of quarks. Almost all the mass of atoms - and hence of you - comes from protons and neutrons. But the vast majority of has nothing to do with the Higgs field. Around 99 percent of the mass of those particles comes not from the intrinsic mass of quarks but from the energy coming from their movement and that of the gluon particles that hold them together. Thanks to Einstein we know energy and mass are equivalent, and though gluons are massless, the energy of the whole vibrant gluon/quark mix inside the protons and neutrons is experienced as mass. Bizarre or what?

Image from Wikipedia

Published on August 31, 2012 01:29

August 30, 2012

John who?

The cover of my rather ancient

The cover of my rather ancientPenguin copyI occasionally like to revisit books I've read before, and recently picked up a title from my shelf by an author that seems to have almost disappeared from the collective memory of science fiction - John Brunner.

When I was in my teens and early twenties, Brunner was everywhere in the SF bookshops. He was a prolific author, and frankly some of his books were poor rushed jobs. But his best were excellent, and deserve to be remembered.

His most famous title is probably Stand on Zanzibar - not one of my favourites, but interesting in its use of news clippings etc to give the book a different feel. It's an over-population book and I was never thrilled by disaster novels. For me, one of his best was The Shockwave Rider. This used Alvin Toffler's extremely popular (and very inaccurate) stab at futurology Future Shock as a model. That part in itself wasn't very interesting, but Brunner gave us images like the computer virus before such things existed and made use of the fascinating if flawed concept of the Delphi principle (the idea that a group of people with no particular knowledge in a subject will improve their response to questions about it if there immediate answers are fed back to the group, which then re-thinks) as a mechanism for government - a really clever idea.

The book I re-read was a much smaller scale work, both physically and in it reach. Called The Productions of Time it features a collection of has-been actors brought together to put on an experimental play. What they don't know is that this is scheme to drive them further and further into their weaknesses to record the experience for an audience from the future. It's not bad as a novel, if not superbly written, but I think it's a great example of the sort of thing that those who criticize SF as a genre don't get. There is some technology (often painfully old-fashioned in its vision of the future: reels of tape? Perlease!) - but this is entirely a book about people.

Admittedly not all great SF is about people. I was amused to hear the excellent Angela Saini struggling to defend Asimov's Foundation trilogy on that rather smug A Good Read programme on Radio 4. The format of the show requires three people to read each others choices of books, and the arty types were definitely looking down their nose at Asimov's dire characterisation. It's true, he couldn't write convincing characters, especially women - but Asimov is great for his ideas, not his characters. The Productions of Time is the absolute opposite - it really is all about the characters and for me is good example of why you shouldn't pigeonhole SF as all blasters and space opera. I'm not ashamed to say I love the original Star Wars trilogy of movies... but sometimes I want something different, and Brunner could put it in SF with the best of them.

Published on August 30, 2012 02:04

August 29, 2012

It's Royal Society of Chemistry podcast time ag...

It's Royal Society of Chemistry podcast time again, and in this podcast I'm dealing with a slippery customer.

It's Royal Society of Chemistry podcast time again, and in this podcast I'm dealing with a slippery customer.PTFE - or teflon if you prefer was not invented. It was discovered by accident. And, in case you've heard otherwise, it wasn't a spin-off of NASA's space effort - they used PTFE, but it had been produced for years before NASA was even formed. And as for the involvement of a French housewife... Take a listen.

Published on August 29, 2012 00:21

August 28, 2012

It'll be a corkscrew next

We drive over to France at least once a year. It's a lovely place to visit and the roads are much nicer to drive on than ours. But I am getting a little tired of the game played by the French authorities where each time you go, they think of a new thing you have to carry in the car.

We drive over to France at least once a year. It's a lovely place to visit and the roads are much nicer to drive on than ours. But I am getting a little tired of the game played by the French authorities where each time you go, they think of a new thing you have to carry in the car.Recently it was a reflective jacket. Next a reflective jacket for everyone in the car. And this year it's breathalysers. Yes, unless you have a breathalyser in the car you can get an on-the-spot fine. I'm really not sure what they are for. After all, if you use your breathalyser, even if it comes up clear you can't drive, because you won't have a breathalyser in the car (OK it's a twin pack, but you know what I mean). It's hard not to see this as a way to rake in easy fines.

So I've been thinking about what next year's imposition might be. And I reckon it will be a corkscrew. You will be fined if you don't have a corkscrew in the car. This is partly because it is unFrench not to be able to open a bottle of wine at any time at a moment's notice, and partly because that way you are more likely to need the breathalysers.

However, just for once, I won't have to make a panic buy at the Shuttle terminal when I see the latest sign at the AA shop telling you what you must have in the car to avoid being hauled off to the chokey. You see, my trusty Swiss army knife already has a corkscrew on board. So there, French police! I'm ready for you.

Published on August 28, 2012 00:48

August 17, 2012

Janet and John scientific papers

There is no doubt that the best detailed source of information on the real science that is being done is in the published papers that scientists are required to turn out to prove that they are still alive and working. But the problem for everyday human beings is

There is no doubt that the best detailed source of information on the real science that is being done is in the published papers that scientists are required to turn out to prove that they are still alive and working. But the problem for everyday human beings isa) They are often expensive to get access to (hence the open access business that gets the likes of the excellent Stephen Curry so worked up)

b) The are often almost unreadable unless you are already an expert in the field.A new initiative called The 21st Floor Wiki Project aims to change that be asking scientists to contribute a page to a Wiki for each paper they publish that explains what the paper says to the general reader. It sounds a great idea, though I suspect many scientists couldn't be bothered to do it, and if they did do it would struggle to make it readable.

However, let's not damn it before it's tried. Here's more details from the handy press release. Why not take a look at the real thing? Though it is a bit devoid of content as yet. Fingers crossed...

Open Access has been a topic that has provoked much debate and discussion in the scientific community with many viewing it as a necessary step to opening up science to the general public and assisting engagement. It is clearly a good thing that research, at least that which is publicly funded, be available to the public whose money allowed research to take place.

However we at the 21st Floor feel that Open Access on it’s own may not be enough, science can be, at times, a complex an inaccessible thing. Research papers are full of disciplinary jargon and research terms that may be daunting to scientists from different disciplines or even from different fields within a single discipline. In short there are papers out there that may remain impenetrable to non-experts which is an issue that open access alone cannot fix.

The 21st Floor Wiki Project plans to open up scientific research to the public by offering plain-language summaries of important scientific research.

If scientists or researchers have written or read anything that has been published in the scientific literature then we would like to invite them to create a page which summarises the work for a lay audience.

We would also like to invite scientists, researchers and science fans to summarise your research, or research you feel is important, in a way that can be easily understood by those outside your field.

We would hope that we could then develop these contributions into a resource that spans all disciplines and makes science more accessible and understandable to both non-scientists and scientists in other fields alike.

If anyone wishes to contribute the page should be named after the published title of the work and should ideally include the following sections (loosely following the structure of a standard research paper):

• A brief summary

• Why the work was done (what inspired the research? why did the authors want to ask these questions?)

• What was done

• What the results were

• What conclusions can be drawn from these results

• Implications of the research (what has been done with the work since publication? has it been reported in the popular press? have any scientific or public controversies arisen from the work?)

The service will always remain completely free of charge and advertising. Hopefully, with your help, we can turn this into a worthwhile resource for everyone who is interested in science and research for any reason.

Published on August 17, 2012 09:36

August 14, 2012

What price being offended?

There's a nice game used by economists and psychologists to help understand human decision making that I investigated for The Universe Inside You called the ultimatum game.

There's a nice game used by economists and psychologists to help understand human decision making that I investigated for The Universe Inside You called the ultimatum game.In it you and a second person are asked to make a decision about some money. The two of you mustn’t discuss your decision in any way. You are given £1 (say) to share. There are no strings attached, it is a genuine gift, you simply have a decision to make before the money is given to you.

The other person decides how the money is split between you. They can split it however they like. The money can be split 50:50, they can keep all the money to themselves, or they can give you a penny and keep the rest… or split it any other way they like between the two of you. You then say either ‘Yes’ and the two of you will get the money, split between you the way the other person decided, or ‘No’ in which case neither of you gets any money. There can be no discussion between the two of you.

This game has been undertaken many times in many circumstances. The logical thing for the person in your place to do is to say ‘Yes’ as long as the first person gives you something. Anything. Even if you’re only offered a penny, it’s money for nothing. In practice, though, the person in your place tends to say ‘No’ unless they get what they regard as a fair proportion of the money.

What counts as a fair proportion varies from considerably from culture to culture. Some will accept as low as 15 percent, others expect a full 50 percent – but in Europe and the US we tend to expect around 30 percent or more before saying ‘Yes’.

What the experiment shows is that we consider trust and fairness worth paying for. We are willing to lose money in exchange for putting things right. If human logic were based purely on economics, then this just doesn’t make sense. You always should take the money. But your brain makes decisions based on a much more complex mix of factors than finance alone.

This is not to say that finance doesn’t have a significant input into decision making - and any psychologist who expects a Western player always to demand 30% or more hasn't really thought this through. If, for example, a billionaire decided to play this game, and offered a total stake of ten million pounds, the chances are that you would accept being offered just one percent - £100,000. Unless you are extremely rich yourself, that is just too life changing an amount of cash to turn it down to teach someone a lesson and punish their lack of fairness. You would swallow your pride, ignore the psychologists and take the one percent cut.

It’s an interesting exercise to think to yourself just how little you would accept in such circumstances. Where between £100,000 and £1 (which most people would reject) would you draw the line on a ten million pound split? (Please do add a comment and tell me). I think I might cave in for as little as £50 - but then I'm cheap.

Published on August 14, 2012 23:31

August 13, 2012

Time and motion

After they'd packed up the crew's kit was quite compact

After they'd packed up the crew's kit was quite compact(bottle for scale) - but this was still no iPhone jobLast week I had the fascinating experience of a film crew coming round to my house. I've done TV interviews in the past, but never had this level of direct exposure to the visual media at work.

I've had suggestions that I was engaged in an episode of Wife Swap or something similar. In fact it's both much less and much more at the same time. It's less because what I did will probably result in 10 seconds on screen, and it's more because this wasn't Channel 4 but a role with a Hollywood connection.

I'll reveal more when we get closer to the date, but the interview was for one of those bonus features you get on a movie DVD. It was about time travel and will accompany a science fiction movie that will be in the cinemas in September. What made it rather exciting was that I was sent a preview DVD of the film (with dire warnings about what would happen if it found its way into circulation, given it's not even in cinemas yet) - and I was then to be interviewed both on time travel in general and the movie in particular.

What I found particularly interesting is that old chestnut that everyone says, but it's hard to believe, about just how long it takes to get a relatively small amount of moving pictures captured. The crew were at my house for around three and a half hours. In that time, admittedly we did get over 40 minutes of interview, but I suspect that will end up as a few seconds on screen. So much of the time is just taken getting the lighting and the setup right - and this was just with a handful of people involved. Suddenly the fact that Hollywood movies cost millions of dollars to make doesn't seem so ridiculous.

It's funny, given we were discussing time, that this all a matter of time - time and motion.

Published on August 13, 2012 23:56