Brian Clegg's Blog, page 138

July 11, 2012

Are you having a laugh?

It's Royal Society of Chemistry podcast time again, and this time round we're having a laugh. In fact it's a gas. Nitrous oxide to be precise. Why not spare five minutes for a giggle - and you'll learn a bit as well about a substance that had them rolling in the aisles over a hundred years ago and has become popular at parties again. Take a listen.

It's Royal Society of Chemistry podcast time again, and this time round we're having a laugh. In fact it's a gas. Nitrous oxide to be precise. Why not spare five minutes for a giggle - and you'll learn a bit as well about a substance that had them rolling in the aisles over a hundred years ago and has become popular at parties again. Take a listen.

Published on July 11, 2012 23:45

Too cheap to meter?

This is the sort of thing you can do with cheap powerWhen I was researching my book Ecologic I came across one of those irritating quotes that seem to belong to more than one person.

This is the sort of thing you can do with cheap powerWhen I was researching my book Ecologic I came across one of those irritating quotes that seem to belong to more than one person.(The classic example of this phenomenon is the aphorism 'Immature poets imitate, mature poets steal' or its variant 'Good artists copy, great artists steal', which are attributed to T. S. Eliot, Stravinsky and Picasso.)

A popular quote that the media use to show how misguided early fans of atomic energy were is that they thought it would be 'too cheap to meter.'

A fair number of UK sources attribute this to one of the British pioneers, Walter Marshall. But I am yet to find a single reference as to the context in which this was said or written, if it ever was, by Marshall.

What seems to have a stronger attribution is that these words were said by the chairman of the US atomic energy commission, Lewis L. Strauss. However the context in which he said this is absolutely essential in understanding it.

Strauss was addressing the National Association of Science Writers in 1954. It was one of those hand-waving, vague visions of a utopian future. Yes, he did say that 'our children will enjoy in their homes electrical energy too cheap to meter' (though not specifically that it would be generated by nuclear fission) but also that there would be an end to disease, hugely extended human lifetimes and world peace. It was that kind of speech. You know the sort of thing.

This is a prediction with about as much support at the time as Alvin Toffler in Future Shock saying that by now we would all be wearing paper clothes, or Clarke and Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey showing Pan Am commercial flights to a space station, and life-size video telephone booths operated by Bell in 2001. It was woffly future-gazing, yet the media repeatedly pick it up as a real expectation that wasn't present in either science or industry at the time.

This prediction isn't a miss, it's a myth.

(If anyone can give me a source for the quote from Walter Marshall, I would be grateful.)

This post first appeared on my Nature Network blog - I'm bringing some of the old posts over to my new home, as the NN blog is liable to disappear soon.

Image from Wikipedia

Published on July 11, 2012 00:25

July 9, 2012

The footballist and the law

Warning - this post contains asterisks

I gather from the news that a footballist by the name of John Terry is in court because of saying something to another footballist called Anton Ferdinand. For me the court case highlights a perversity in the law that I've mentioned before, but this brings it out stronger than ever.

According to what I remember from last night's news (so wording may not be exact), Ferdinand taunted Terry about his extra-marital affair and used an obscene gesture. In response, Terry said to Ferdinand 'F*** off! F*** off! You black c***!' and it is this phrase that has landed him in court.

As someone with once red hair, who got the usual taunting when younger, I think it is totally unfair that this is treated totally differently to what would have happened had Terry responded to a red-haired player by saying 'F*** off! F*** off! You ginger c***!' In those circumstances I presume there would have been no case.

Surely the law itself is racist here. It is illegal to abuse someone based on their colouring if they are one race, but it is not illegal to abuse someone based on their colouring if they are another race. This is blatant discrimination.

In practice it is a travesty that a week's court time is being taken up with this. Okay, the footballists will be paying their legal bills, I guess, but there is still the cost to the taxpayer of the whole business and a court locked up for a week delaying other cases. I'm not saying the incident should have been ignored. The FA should have fined both of them for verbal abuse and bringing the game into disrepute - and rather than the piddling fine liable to come from court I'd suggest at least a month's wages, which should be paid to charity rather than going to the FA. But the court case is just wrong.

I gather from the news that a footballist by the name of John Terry is in court because of saying something to another footballist called Anton Ferdinand. For me the court case highlights a perversity in the law that I've mentioned before, but this brings it out stronger than ever.

According to what I remember from last night's news (so wording may not be exact), Ferdinand taunted Terry about his extra-marital affair and used an obscene gesture. In response, Terry said to Ferdinand 'F*** off! F*** off! You black c***!' and it is this phrase that has landed him in court.

As someone with once red hair, who got the usual taunting when younger, I think it is totally unfair that this is treated totally differently to what would have happened had Terry responded to a red-haired player by saying 'F*** off! F*** off! You ginger c***!' In those circumstances I presume there would have been no case.

Surely the law itself is racist here. It is illegal to abuse someone based on their colouring if they are one race, but it is not illegal to abuse someone based on their colouring if they are another race. This is blatant discrimination.

In practice it is a travesty that a week's court time is being taken up with this. Okay, the footballists will be paying their legal bills, I guess, but there is still the cost to the taxpayer of the whole business and a court locked up for a week delaying other cases. I'm not saying the incident should have been ignored. The FA should have fined both of them for verbal abuse and bringing the game into disrepute - and rather than the piddling fine liable to come from court I'd suggest at least a month's wages, which should be paid to charity rather than going to the FA. But the court case is just wrong.

Published on July 09, 2012 23:57

Do sceptics rush in where angels fear to tread?

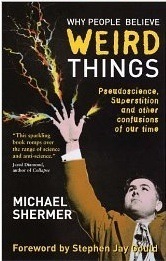

I'm currently reading the new edition of Michael Shermer's

Why People Believe Weird Things

which is an excellent book debunking pseudoscience and superstition, from the man who is probably our best known media sceptic.

I'm currently reading the new edition of Michael Shermer's

Why People Believe Weird Things

which is an excellent book debunking pseudoscience and superstition, from the man who is probably our best known media sceptic.However, at one point, Shermer does trip over his own assertions. (I point this out in the same spirit as that of Bill Bryson, using examples of bad English that he found in guides to English usage in his own guide.)

Shermer is careful to first explain the difference between the scientific method and the way most pseudoscience is reported. (He doesn't mention it, but I love Robert Park's encapsulation of this in Voodoo Science as 'data is not the plural of anecdote'.)

Shermer tells us that in science we should be scrupulous about presenting data that goes against our theories, rather than being selective with the observations. But then, only pages later, he indulges in a little selectivity himself. To illustrate the recent growth of science and technology, he tells us that transportation speed has undergone geometric growth. His list goes from stagecoach (1784) 10 miles per hour, through bicycle (1870) 17 mph, steam train (1880) 100 mph, airplane (1934) 400 mph, rocket (1960) 4000 mph, space shuttle (1985) 18000 mph to TAU deep space probe (2000) 225,000 mph. (I've skipped some entries, but this gives a feel for the sequence.)

There's more than one bit of naughtiness with the data here, I fear. The last entry isn't human transport, so really can't be counted as being from the same data set - you might as well put the speed of a bullet in there. If you drop that last entry we have a graph that flatlines 22 years ago.

But, more worryingly, there is also a discontinuity in the data. Up to airplane, they are all modes of transport available to normal people. From rocket onwards, they are specialist devices not available to the rest of us. If you keep the more consistent comparison of generally available transport, the graph is much more interesting. It goes a lot higher than 'airplane', because in the 1970s we got Concorde taking us to Mach 2 (over 1500 mph). But that was the last upward step. And since Concorde was withdrawn, the transport speed graph drops to less than half its previous value. It is currently in the high 500s. So that geometric progression isn't anywhere near so solid as Shermer's figures suggest. Say after me, Michael - 'We should be scrupulous about presenting data that goes against our theories'.

I don't point this out to knock Shermer, or the book, which is very good, just to point out the difficulties that come hand in hand with being a sceptic. (Or should I say skeptic, as the book uses US spelling. I just love reading the word 'skeptic' because to UK eyes it looks so seventeenth century, a bit like spelling optics or physics as opticks and physicks - I'm sure the reverse is true when US readers see some of our spellings.)

This post first appeared on my Nature Network blog - I'm bringing some of the old posts over to my new home, as the NN blog is liable to disappear soon.

Published on July 09, 2012 00:18

July 6, 2012

Supporting zombies everywhere

Okay, there are some causes that not everyone buys into. If you are dog lover, for instance, you might not want to contribute to the cat's protection league. But there is one cause I feel everyone can get behind. Who doesn't love a good zombie? Even better, who doesn't love a zombie crawl?

If you happen to live in sunny Herne Bay you can go along and see one on November 3rd 2012 - but even if you don't, you can give those zombies money to stop them scooping out your brains electronically by clicking through to JustGiving.

Best of all, rather than trying to eat your money, said zombies are giving the donations to Kent Air Ambulance. Awww. Sweet.

If you happen to live in sunny Herne Bay you can go along and see one on November 3rd 2012 - but even if you don't, you can give those zombies money to stop them scooping out your brains electronically by clicking through to JustGiving.

Best of all, rather than trying to eat your money, said zombies are giving the donations to Kent Air Ambulance. Awww. Sweet.

Published on July 06, 2012 07:04

July 5, 2012

We're going on Higgs hunt

We're going on Higgs hunt,

We're going on Higgs hunt,Going to catch a big one!

I'm not scared - been here before.

And haven't we just. With rumours flying wildly that the discovery of the existence of the Higgs boson (or that nautical favourite, the Higgs bosun as some members of the press will unerringly refer to it) would be announced from CERN yesterday morning (and in the end it was, sort of), it was fascinating to see the US Tevatron team rushing in with a non-announcement earlier in the week that they might have seen something that might be significant.

This is ironic in a way, because the US should have been here first with the heavy guns. The Superconducting Super Collider was going to be the machine that finally laid the is-it-isn't-it saga to rest on the Higgs boson, a.k.a. the God particle. After spending around 2 billion dollars on it, funding was pulled when the option was to either continue this or the US contribution to the International Space Station (which, incidentally, has much less scientific benefit). Now the European Large Hadron Collider, which interestingly hasn't cost hugely more than had already been spent on the SSC, has delivered the goods.

Yesterday we were bombarded with the Higgs on the news - this is the sort of science news that makes the mainstream, though it usually gets the non-science journalists in a twist as they try to explain with limited success what a Higgs boson is (or isn't). And inevitably there was some muttering about whether we should be spending all that money on pure scientific research.

A frequent argument in support is spin-offs. Look at all the benefits we've got, they say. This is actually often a weak argument. Admittedly pure quantum physics research led us to electronics (I was amused to hear a particle physicist say that electronics was a spin-off of particle physics rather than quantum physics), and CERN has already given us the world wide web, but this isn't really the right argument. Also it can be mis-deployed. Look at NASA, with a budget last year of around £12 billion. Well, they've given us, erm teflon, haven't they? Well, no. It was discovered long before NASA existed, and its first big commercial use was by a Frenchman in Tefal frying pans. Okay, well, there was velcro, wasn't there? Well, no. That was also invented long before NASA existed. By a Swiss guy. About the best you can do for NASA is memory foam mattresses.

(Please don't tell me NASA was responsible for the microcomputer - development of that was driven by commercial pressures, not one-off uses.)

However, I'd say that focussing on spin-offs misses the point. The circa £2.6 billion spent on the LHC is worth spending for pure science, for the discovery, for the wonder. Let's put it in perspective. The UK contribution to CERN is around £95 million a year, of which just over a third is direct to the LHC. Compare that with the UK's international aid budget where we happily spend over £9 billion - indubitably more than £95 million of that goes into back pockets of dictators and corrupt officials. Or even our arts budget at over £1 billion helping subsidise opera houses and knit-your-own-yoghurt whale hugging seminars. By comparison £34 million or so a year on the LHC to help discover the mechanism of the universe seems a very small price to pay indeed.

Introductory verse with HT to Michael Rosen

Image from Wikipedia

Published on July 05, 2012 00:56

July 4, 2012

On the merits of rock concerts

Someone whose gig I would go toMusically speaking, I was a strange child. The first album I ever bought, age 11, was Elgar's Dream of Gerontius (Barbirolli, I think). To be fair, we were doing it in the school choir, I didn't just didn't randomly feel the urge to buy it. I was 15 when I first bought a contemporary record - the Beatles' Abbey Road.

Someone whose gig I would go toMusically speaking, I was a strange child. The first album I ever bought, age 11, was Elgar's Dream of Gerontius (Barbirolli, I think). To be fair, we were doing it in the school choir, I didn't just didn't randomly feel the urge to buy it. I was 15 when I first bought a contemporary record - the Beatles' Abbey Road.Similarly, while all my friends were going to gigs by Tyrannosaurus (sic) Rex and Van der Graaf Generator, I...wasn't. I just wasn't interested. Since then the closest I have come to a rock concert has been Cliff Richard (don't laugh - I didn't go voluntarily), the Flying Pickets and Al Stewart. (Now that was a brilliant gig. Next time Mr Stewart is touring in the UK I will be along there like the proverbial gig ferret.)

Now I've always said, if there's one band I really would like to see live it's Pink Floyd. I love their music and they allegedly gave great shows. Realistically it is never going to happen, so when it turned out that acclaimed tribute band Brit Floyd were coming to a theatre near us, I jumped at the chance and bought tickets.

The gig was last night. And I nearly didn't go. When it came to it, on the day, I wasn't sure I could be bothered. What I think it really was is that I rarely have enthusiasm for sitting listening to music (unless it is the brilliant Mr Stewart). I normally only do it in the car. I can't work to music, for instance - I just find it an irritating distraction. So despite paying nearly £60 for two tickets, I almost left them to get on with it and stayed at home.

However I did go, and I have to say they were brilliant. Ever since mistakenly buying a live Yes album I've always been a little worried about live performance of complex contemporary music, but Brit Floyd really hit the classics (and they did many of them) spot on. It was visually impressive and musically excellent. The only time I raised an eyebrow is I didn't remember a Floyd piece that had a reference to the Doctor Who theme in it, but a quick web search tells me there is one, on Meddle, one of the few of their albums I don't have.

I'm not sure I'd go to one of their gigs again - it's one of those 'I've done it now' things. But I'm really glad I went. In case you don't believe decent Floyd-a-like can be done, here's Brit Floyd doing Money:

Image from Wikipedia

Published on July 04, 2012 00:15

July 2, 2012

O stoats and weasels!

Leaving aside the fact that the title of this blog post would make quite a good mild expletive - something definitely due a comeback after all the explicit four letter words on reality TV - it reflects a frustration I've finally decided to finish.

Taking the dog for an afternoon walk in pale autumn sunlight [ok, this is a repost of an old one, but to be honest, pale autumn sunlight seems about the best we can hope for this July], our path was crossed by a creature resembling a stretched limo version of a mouse. But was it a stoat or a weasel? Which is the mouse-sized version?

My frustrated lack of ability to remember is stoked to greater heights of fury by a friend and ex-King's Singer (but that's another story) I occasionally go for a walk with, who has the habit of gnomically uttering 'a weasel is w-easily recognised as a stoat is s-totally different' or some such remark, which doesn't help a great deal.

If I read Wikipedia right, the weasel, as we know it in the UK, is actually the least weasel and is a lot smaller than the stoat. (Don't you just love it that an animal can be a 'least something'?) So with natural perversity, the one with the shorter name is the bigger of the two (to help me remember). So there.

This post first appeared on my Nature Network blog - I'm bringing some of the old posts over to my new home, as the NN blog is liable to disappear soon.

Image from Wikipedia

Published on July 02, 2012 23:59

Einstein does a funny

A journal which I'm sure is very readableA while ago, straying through the depths of Nature Network, I saw an item on writing more readable papers. There may well be several out there - it's a hoary old topic.

A journal which I'm sure is very readableA while ago, straying through the depths of Nature Network, I saw an item on writing more readable papers. There may well be several out there - it's a hoary old topic.I don't dispute the suggestion that many scientific papers could be better written, but in the end, however approachable, they are unlikely to get a reprint in Heat magazine, so it is still a matter of writing to the audience. Without doubt, though, it's a relief when the writer of a paper adopts a lighter tone and writes like a human being, rather than a robot.

I suppose the best known instance of putting a human face to a paper, which some have held up as a shining example of what's possible, is Einstein's paper on subjective time. The abstract reads:

When a man sits with a pretty girl for an hour, it seems like a minute. But let him sit on a hot stove for a minute - and it’s longer than any hour. That’s relativity.In the paper he allegedly describes undertaking an experiment to test this, with the help of film star Paulette Goddard, who he met through mutual friend Charlie Chaplin. However there are three big problems if anyone considers Einstein's very approachable sounding paper a model of how to write more effectively.

First, get real. This was Einstein. He could have written a paper in mirror writing and someone would have published it.

Second, we usually only hear of the abstract. The main body of the paper sounds very unlikely. Einstein undertaking an experiment? That's fishy.

Finally, though I have only ever seen this mentioned as if it were a real paper, I haven't been able to find any reference to the journal it was supposed to be published in anywhere, other than references to Einstein's contribution. It may be this is a really obscure journal (or even a very famous one in its own field), but given what its significant initials spell, I'm inclined to doubt it. And if the whole thing is fictional, maybe it doesn't provide such a great role model.

Where was it allegedly published? In the Journal of Exothermic Science and Technology.

This post first appeared on my Nature Network blog - I'm bringing some of the old posts over to my new home, as the NN blog is liable to disappear soon.

Image from Wikipedia

Published on July 02, 2012 01:22

June 29, 2012

Science and Paris Hilton

A not very popular science writer at workI write in a genre that's usually labelled "popular science" to distinguish it from the real academic stuff. In a recent Scientific American, the excellent Michael Shermer writes that popular science writing is often esteemed less than technical writing, and that he considers it very narrow and naive to regard anything other than peer reviewed papers as "mere popularization."

A not very popular science writer at workI write in a genre that's usually labelled "popular science" to distinguish it from the real academic stuff. In a recent Scientific American, the excellent Michael Shermer writes that popular science writing is often esteemed less than technical writing, and that he considers it very narrow and naive to regard anything other than peer reviewed papers as "mere popularization."I must admit, I've always had a bit of inverted view, thinking that, at least from a quality of writing viewpoint, most science writing other than popular science is pretty unreadable. (Someone has to stick up for the poor science writers.)

Yet enthusiastic though I am about popular science, I feel a little nervous about that word "popular." Reading about celebrities like Ms Hilton is popular [2012 note - of course celebrities come and go - if I was writing this now I suppose it would someone from TOWIE or Pippa Middleton], but is reading about science? It's certainly true that there was a brief flowering of popularity around A Brief History of Time, but on the whole, I don't see much science up the front of the bookstores on the "new and exciting things" shelves. I'm much more likely to find a cookbook or a celebrity biography.

This may sound like a moan, but it's not, it's a spur to action. All of us who write this kind of book should be looking for ways to make science genuinely popular. Not only would this boost our royalties (which few of us would object to), it's also important because getting science across to a wider public matters a lot.

My first small contribution is the website www.popularscience.co.uk which is a review site for popular science books, but that's largely preaching to the converted. As for the rest, I intend to keep trying.

This post first appeared on my Nature Network blog back in 2007- I'm bringing some of the old posts over to my new home, as the NN blog is liable to disappear soon.

Published on June 29, 2012 01:03