Brian Clegg's Blog, page 136

August 13, 2012

Remember those for whom sport is hell

[image error]

The Olympics has quite rightly generated a lot of enthusiasm for sport in the UK after all those shiny medals were won, and that's fine. To be honest, I found the Olympic thing much more interesting than I thought I would. But there is one clamour that I think needs a little balance.

We have Boris Johnson, for instance, weighing in saying that schools should institute 2 hours compulsory sport a day like he enjoyed at school, and all the Tories are baying about the importance of forcing competitive team sport on young people. I absolutely understand their aversion to 'everyone is equal and there are no winners and losers' type inclusive sports days.

But.

In all this enthusiasm to force our youth into as much compulsory competitive sport as possible, spare a thought for the poor people like me who hated sport at school. I didn't mildly dislike it - I truly found it the most unpleasant experience of my life. Think of the poor sods like me who were truly rubbish at sport. Who never had a hope of coming in the first twenty in a race. Who were always the last ones picked when teams were chosen.

Football wasn't bad as I fairly quickly got the position of dog catcher. There were two dogs (Prince and Rex if memory serves - very regal stray dogs, we had in Manchester) who constantly invaded our school football pitches and tried to get possession of the ball. The only hope of having a game was if someone fended off the dogs and that I was very happy to do as long as I didn't have to come close to that leather, mud-coated monstrosity.

But the rest was hell, and our PE teacher, one Mr Welsby, really was of the evil sadist mould that you often see portrayed in humorous fiction. Cross country running was a constant agony as I suffered badly from stitches. Cricket was a nightmare as I couldn't hit the ball, run quickly enough or catch. We'll draw a veil over lacrosse, rugby and swimming lessons that (genuinely) would be a criminal offence if still operated as they were then. And the gym was vast embarrassment as I couldn't do a forward roll without falling over sideways, couldn't make it over the vaulting horse and couldn't climb a rope. And still couldn't after four years of gym classes. Then throw in the horror of communal showers and you've got something Dante would be proud of.

It's easy to make all this sound funny, but it really wasn't. We had two hours of outdoor sport and one hour in the gym a week. If we had suffered the regime Boris suggested I genuinely would have contemplated suicide. These were the most horrible hours of my young life. If we had been able to play something like badminton or table tennis, it might have been different. But traditional school team sports were a horror for me, and I can't believe I was the only one.

So by all means celebrate the Olympic triumphs. Do consider how we can get our youth exercising. But don't make it the sort of experience I had for people who think that a kick around with a ball is on a par with waterboarding.

Image from Wikipedia

We have Boris Johnson, for instance, weighing in saying that schools should institute 2 hours compulsory sport a day like he enjoyed at school, and all the Tories are baying about the importance of forcing competitive team sport on young people. I absolutely understand their aversion to 'everyone is equal and there are no winners and losers' type inclusive sports days.

But.

In all this enthusiasm to force our youth into as much compulsory competitive sport as possible, spare a thought for the poor people like me who hated sport at school. I didn't mildly dislike it - I truly found it the most unpleasant experience of my life. Think of the poor sods like me who were truly rubbish at sport. Who never had a hope of coming in the first twenty in a race. Who were always the last ones picked when teams were chosen.

Football wasn't bad as I fairly quickly got the position of dog catcher. There were two dogs (Prince and Rex if memory serves - very regal stray dogs, we had in Manchester) who constantly invaded our school football pitches and tried to get possession of the ball. The only hope of having a game was if someone fended off the dogs and that I was very happy to do as long as I didn't have to come close to that leather, mud-coated monstrosity.

But the rest was hell, and our PE teacher, one Mr Welsby, really was of the evil sadist mould that you often see portrayed in humorous fiction. Cross country running was a constant agony as I suffered badly from stitches. Cricket was a nightmare as I couldn't hit the ball, run quickly enough or catch. We'll draw a veil over lacrosse, rugby and swimming lessons that (genuinely) would be a criminal offence if still operated as they were then. And the gym was vast embarrassment as I couldn't do a forward roll without falling over sideways, couldn't make it over the vaulting horse and couldn't climb a rope. And still couldn't after four years of gym classes. Then throw in the horror of communal showers and you've got something Dante would be proud of.

It's easy to make all this sound funny, but it really wasn't. We had two hours of outdoor sport and one hour in the gym a week. If we had suffered the regime Boris suggested I genuinely would have contemplated suicide. These were the most horrible hours of my young life. If we had been able to play something like badminton or table tennis, it might have been different. But traditional school team sports were a horror for me, and I can't believe I was the only one.

So by all means celebrate the Olympic triumphs. Do consider how we can get our youth exercising. But don't make it the sort of experience I had for people who think that a kick around with a ball is on a par with waterboarding.

Image from Wikipedia

Published on August 13, 2012 01:25

August 10, 2012

On mysterious gasses and robins

Full marks to any movie buff who can say which classic cult film from the 1980s gave me the ability to include a mysterious gas and robins in the title of this post. Take a guess...

... no, go on, I can wait...

... any idea?...

It was, in fact, David Lynch's Blue Velvet, which I have heard much of and have finally had a chance to watch thanks to Netflix. It would be an exaggeration to say I liked the film, but I am certainly glad I've seen it - and unpleasant though it is, it's hard not to admire Lynch's work.

The gas in question is the one inhaled at various points by the truly menacing figure of Frank, played by Dennis Hopper. I'd read somewhere before watching the film that this was helium, so I was expecting some scenes with a bizarre silly voice - it might have worked in a menace-by-contrast way, but his voice never changed - so it wasn't helium. (I do find it amazing that a very rare element, so difficult to keep on this planet that it was first discovered on the sun, should be primarily a thing we buy to put in party balloons and to make silly voices. But that's a different blog post.) My suspicion is that it was nitrous oxide - while Frank doesn't display the merriness that often accompanies this, that could be down to his psychotic personality.

And then there's the robin. At the end of the film, the main character's girlfriend played by Laura Dern has been making comments about having a dream about robins being the essence of love - and they see a robin perched outside the window. But the robin is eating a black bug, which rather reduces the 'awww' factor. Reading the Wikipedia entry on the movie's symbolism, I was rather surprised that they didn't notice what, to me, was an obvious reference to and distortion of a scene in Mary Poppins.

In that film an equally fake looking robin (could it be the same one? There can't be too many mechanical robins in Hollywood) also perches outside a window. This has always been a moment that jarred for me because, although Mary Poppins is set in London, the 'robin' portrayed in that film is what's called a robin in the US and bears no resemblance to an actual European robin. Because of this, the image stuck with me - and it's hard not to see a parallel. Of course you can work too hard looking for symbolism... but for me it's a definite reference. Nice one, Dave.

... no, go on, I can wait...

... any idea?...

It was, in fact, David Lynch's Blue Velvet, which I have heard much of and have finally had a chance to watch thanks to Netflix. It would be an exaggeration to say I liked the film, but I am certainly glad I've seen it - and unpleasant though it is, it's hard not to admire Lynch's work.

The gas in question is the one inhaled at various points by the truly menacing figure of Frank, played by Dennis Hopper. I'd read somewhere before watching the film that this was helium, so I was expecting some scenes with a bizarre silly voice - it might have worked in a menace-by-contrast way, but his voice never changed - so it wasn't helium. (I do find it amazing that a very rare element, so difficult to keep on this planet that it was first discovered on the sun, should be primarily a thing we buy to put in party balloons and to make silly voices. But that's a different blog post.) My suspicion is that it was nitrous oxide - while Frank doesn't display the merriness that often accompanies this, that could be down to his psychotic personality.

And then there's the robin. At the end of the film, the main character's girlfriend played by Laura Dern has been making comments about having a dream about robins being the essence of love - and they see a robin perched outside the window. But the robin is eating a black bug, which rather reduces the 'awww' factor. Reading the Wikipedia entry on the movie's symbolism, I was rather surprised that they didn't notice what, to me, was an obvious reference to and distortion of a scene in Mary Poppins.

In that film an equally fake looking robin (could it be the same one? There can't be too many mechanical robins in Hollywood) also perches outside a window. This has always been a moment that jarred for me because, although Mary Poppins is set in London, the 'robin' portrayed in that film is what's called a robin in the US and bears no resemblance to an actual European robin. Because of this, the image stuck with me - and it's hard not to see a parallel. Of course you can work too hard looking for symbolism... but for me it's a definite reference. Nice one, Dave.

Published on August 10, 2012 00:13

August 9, 2012

A la recherche de mushy pea perdu

I am generally dubious about the whole A La Recherche de Temps Perdu thing, a) because I suspect (I've never read it) the novel is a load of pretentious tosh and b) because it is scientifically incorrect. When Marcel Proust tediously droned on about childhood memories evoked by the taste of a Madeleine cake dipped in tea, he was using the wrong sense as a trigger. Maybe he should have gone for a smell.

While it apparently isn't true that the sense of smell is the strongest when evoking memories (vision wins), it does seem from the way the neurons fire in the brain that the first time a smell gets tied to a particular object or activity it kicks of considerably more energetic brain activity than it does on other occasions - so first smell associations appear to be powerful.

I had one brought back to me the other day when, for reasons we don't need to go into, I ended up boiling a pan of mushy peas on the stove for 25 minutes. I was instantly transported to my grandma's house. That smell was the smell of being at my grandmother's, yet until that moment I hadn't realized it - or I had forgotten.

For some reason, she always used dried peas, so they would almost always be either soaking or cooking until mushy, with that distinctive smell that if I were a wine expert I would suggest had hints of flannel and bicarbonate of soda. More often than not it would be black peas (nothing to do with black-eyed peas) on the go. This particular pea variant, actually a dark brown, was a favourite in Lancashire mill towns - a speciality for bonfire night alongside parkin and jacket potatoes, but also an everyday treat. On my aunt's council estate in Rochdale there was even a black pea man who came round selling them every evening. He started with a bicycle, but ended up with a converted ice cream van.

If you ever have the joy of eating mushy peas, or even better mushy black peas (they are nicer - nuttier and with more complex flavours), one word of warning. I have had people (mostly ignorant southerners) say to me that mushy peas are tasteless. If this is your opinion, you haven't eaten them properly. They MUST have a pinch of salt and a good sloshing of vinegar - more vinegar than you could possibly imagine was necessary. (First time round keep adding a bit at a time until you see why.) This transforms the flavour and makes them delectable. What's not to love?

P.S. In looking for a picture of black peas to include I came across a picture of mushy peas that was actually pea puree. Mushy peas should not be a puree - they still have their pea form, but have exuded enough gunk to have a thick 'gravy'. If they end up as literal mush you have gone to far.

While it apparently isn't true that the sense of smell is the strongest when evoking memories (vision wins), it does seem from the way the neurons fire in the brain that the first time a smell gets tied to a particular object or activity it kicks of considerably more energetic brain activity than it does on other occasions - so first smell associations appear to be powerful.

I had one brought back to me the other day when, for reasons we don't need to go into, I ended up boiling a pan of mushy peas on the stove for 25 minutes. I was instantly transported to my grandma's house. That smell was the smell of being at my grandmother's, yet until that moment I hadn't realized it - or I had forgotten.

For some reason, she always used dried peas, so they would almost always be either soaking or cooking until mushy, with that distinctive smell that if I were a wine expert I would suggest had hints of flannel and bicarbonate of soda. More often than not it would be black peas (nothing to do with black-eyed peas) on the go. This particular pea variant, actually a dark brown, was a favourite in Lancashire mill towns - a speciality for bonfire night alongside parkin and jacket potatoes, but also an everyday treat. On my aunt's council estate in Rochdale there was even a black pea man who came round selling them every evening. He started with a bicycle, but ended up with a converted ice cream van.

If you ever have the joy of eating mushy peas, or even better mushy black peas (they are nicer - nuttier and with more complex flavours), one word of warning. I have had people (mostly ignorant southerners) say to me that mushy peas are tasteless. If this is your opinion, you haven't eaten them properly. They MUST have a pinch of salt and a good sloshing of vinegar - more vinegar than you could possibly imagine was necessary. (First time round keep adding a bit at a time until you see why.) This transforms the flavour and makes them delectable. What's not to love?

P.S. In looking for a picture of black peas to include I came across a picture of mushy peas that was actually pea puree. Mushy peas should not be a puree - they still have their pea form, but have exuded enough gunk to have a thick 'gravy'. If they end up as literal mush you have gone to far.

Published on August 09, 2012 01:06

August 8, 2012

Nature's Nanotech #4 - The Importance of Being Wet

The fourth in my series of posts on nature's nanotechnology, also featuring on www.popularscience.co.uk

The image that almost always springs to mind when nanotechnology is mention is Drexler’s tiny army of assemblers and the threat of being overwhelmed by grey goo. But what many forget is that there is a fundamental problem in physics facing anyone building invisibly small robots (nanobots) – something that was spotted by the man who first came up with the concept of working on the nanoscale.

That man was Richard Feynman. His name may not be as well known outside physics circles as, say, Stephen Hawking, but ask a physicist to add a third to a triumvirate of heroes with Newton and Einstein and most would immediately choose Feynman. It didn’t hurt that Richard Feynman was a bongo-playing charmer whose lectures delighted even those who couldn’t understand the science, helped by an unexpected Bronx accent – imagine Tony Curtis lecturing on quantum theory.

That man was Richard Feynman. His name may not be as well known outside physics circles as, say, Stephen Hawking, but ask a physicist to add a third to a triumvirate of heroes with Newton and Einstein and most would immediately choose Feynman. It didn’t hurt that Richard Feynman was a bongo-playing charmer whose lectures delighted even those who couldn’t understand the science, helped by an unexpected Bronx accent – imagine Tony Curtis lecturing on quantum theory.Feynman became best known to the media for his dramatic contribution to the Challenger inquiry, when in front of the cameras he plunged an O-ring into iced water to show how it lost its elasticity. But on an evening in December 1959 he gave a lecture that laid the foundation for all future ideas of nanobots. His talk at the annual meeting of the American Physical Society was titled There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom, and his subject was manipulating and controlling things on a small scale.

Feynman pointed out that people were amazed by a device that could write the Lord’s Prayer on the head of a pin. But ‘Why cannot we write the entire 24 volumes of the Encyclopedia Britannica on the head of a pin?’ As he pointed out, the dots that make up a printed image, if reduced to a scale that took the area of paper in the encyclopedia down to pinhead size, would still contain 1,000 atoms each – plenty of material to make a pixel. And it could be read with technology they had already.

Feynman went on to describe how it would be possible to write at this scale, but also took in the idea that the monster computers of his day would have to become smaller and smaller to cram in the extra circuits required for sophisticated computation. Then he described how engineering could be undertaken on the nanoscale, and to do so, he let his imagination run a little wild.

What Feynman envisaged was making use of the servo ‘hands’ found in nuclear plants to act remotely, but instead of making the hands the same size as the original human hands, building them on a quarter scale. He would also construct quarter size lathes to produce scaled down parts for new devices. These quarter scale tools would be used to produce sixteenth scale hands and lathes, which themselves would produce sixty-fourth scale items… and so on, until reaching the nanoscale.

The second component of Feynman’s vision was a corresponding multiplication of quantity, as you would need billions of nanobots to do anything practical. So he would not make one set of quarter scale hands, but ten. Each of those would produce 10 sixteenth scale devices, so there would be 100 of them - and so on. Feynman points out there would not be a problem of space or materials, because one billion 1/4000 scale lathes would only take up two percent of the space and materials of a conventional lathe.

When he discussed running nanoscale machines, Feynman even considered the effect on lubrication. The mechanical devices we are familiar with need oil to prevent them ceasing up. As he pointed out, the effective viscosity of oil gets higher and higher in proportion as you go down in scale. It stops being a lubricant and starts being like attempting to operate in a bowl of tar. But, he argues, you may well not need lubricants, as the bearings won’t run hot because the heat would escape very rapidly from such a small device.

So far, so good, but what is the problem Feynman mentions? He points out that ‘As we go down in size there are a number of interesting problems that arise. All things do not simply scale down in proportion.’ Specifically, as things get smaller they begin to stick together. If you unscrewed a nanonut from a nanobolt it wouldn’t fall off – the Van der Waals force we met on the gecko’s foot is stronger than the force of gravity on this scale. Small things stick together in a big way.

Feynman is aware there would be problems. ‘It would be like those old movies of a man with his hands full of molasses, trying to get rid of a glass of water.’ But he does effectively dismiss the problems. In reality, the nano-engineer doesn’t just have Van der Waals forces to deal with. Mechanical engineering generally involves flat surfaces briefly coming together to transfer force from one to the other, as when the teeth of a pair of gears mesh. But down at the nanoscale a new, almost magical, force springs into life – the Casimir effect.

If two plates get very close, they are attracted towards each other. This has nothing to do with electromagnetism, like the Van der Waals force, but is the result of a weird aspect of quantum theory. All the time, throughout all of space, quantum particles briefly spring into existence, then annihilate each other. An apparently empty vacuum is, in fact, a seething mass of particles that exist for such a short space of time that we don’t notice them.

However, one circumstance when these particles do come to the fore is when there are two sheets of material very close to each other. If the space separating the sheets is close enough, far fewer of these ‘virtual’ particles can appear between them than outside them. The result is a real pressure that pushes the plates together. Tiny parallel surfaces slam together under this pressure.

The result of these effects is that even though toy nanoscale gears have been constructed from atoms, a real nanotechnology machine – a nanobot – would simply not work using conventional engineering. Instead the makers of nanobots need to look to nature. Because the natural world has plenty of nanoscale machines, moving around, interacting and working. What’s the big difference? Biological machines are wet and soft.

By this I don’t mean they use water as a lubricant rather than oil, but rather they are not usually a device made up of a series of interlocking mechanical components like our machines but rather use a totally different approach to mechanisms and interaction that results in a ‘wet’, soft environment lacking flat surfaces and the opportunities for small scale stickiness to get in the way of their workings.

If we are to build nanomachines, our engineers need to think in a totally different way. We need to dismiss Feynman’s picture of miniature lathes, nuts, bolts and gears. Instead our model has to be the natural world and the mechanisms that evolution has generated to make our, admittedly inefficient, but still functioning nanoscale technology work and thrive. The challenge is huge – but so is the potential.

In the next article in this series we will look at the lessons we can learn from a specific example of nature’s ability to manufacture technology on the nanoscale – the remarkable virus.

Image from Wikipedia

Published on August 08, 2012 00:33

August 6, 2012

Nice one, Boris

Unlike the inestimable Henry Gee, I am not a 100 per cent supporter of everything Boris Johnson does and says - though I think a lot of people do underestimate him.

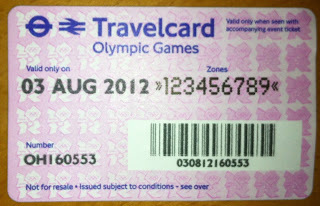

Unlike the inestimable Henry Gee, I am not a 100 per cent supporter of everything Boris Johnson does and says - though I think a lot of people do underestimate him.There's one thing, though, from my experience of visiting the Olympics last Friday, for which I award Boris a gold medal (or LOCOG or whoever thought of it). Quite unexpectedly, along with our Olympic tickets we found day passes for London Underground, busses etc in our jolly Olympics welcome pack.

Leaving aside this saved us around £30 on what was inevitably quite an expensive day out, it was such a good idea. It felt like a positive gesture - we were getting something for nothing we would otherwise pay for - and it encouraged people to use public transport to go to the games. Best of all, it looked like joined up thinking. I was a little worried that the tickets would only take us to and from the venue, but we happily made an excursion to Covent Garden (no, not the opera house) on the way back with no trouble.

Forget celebrating all those British medals. This, for me, was the real success of the 2012 Games.

Published on August 06, 2012 01:30

August 2, 2012

What goes around comes around

Another Fred and George, now sadly no

Another Fred and George, now sadly nolonger with usI've always been interested in the things that inspire writers of fiction. I'm not talking about that painful interview question 'Where do you get your ideas from?' which makes every writer cringe. That is silly indeed. But there are certainly things that point writers in certain directions over and above the output of their own creative juices.

I was inspired to think about this in a big way while re-reading, for a spot of summer light relief, one of the P. G. Wodehouse Jeeves books - to be precise, The Inimitable Jeeves. It struck me that consciously or unconsciously J. K. Rowling (notice a similarity in the authors' names?) must have been influenced by a pair of characters in this book.

Specifically there are twins, named Claude and Eustace, who are at college when we meet them. This pair are always up to mischief, either simply causing havoc or, if possible, running dubious schemes to make themselves cash. Does this sound at all familiar?

I don't know if Fred and George Weasley were a conscious hat tip to P. G. from J. K. or simply inspired by a session reading Wodehouse long before that was not directly remembered - but either way it is hard to believe that Claude and Eustace were not prototypes of the mischievous Hogwarts entrepreneurs.

I don't think this is a bad thing, merely worthy of note.

Published on August 02, 2012 02:04

July 31, 2012

Are you a humanist?

Are you a humanist? Should you care? Take a look at this short, interesting video featuring some quite well known people talking on the subject, and then I'll share my thoughts with you.

Okay, what did you think? My feeling after watching it is that I quite like a lot that goes with being a humanist, apart from one huge assumption that all those taking part seem to make, which is that if you are a humanist you must be an atheist. You see, I think the most scientific religious viewpoint to take is to be an agnostic, and I don't see any conflict with being a humanist.

If you are an atheist you say 'I refuse to be open minded. I KNOW what the truth is and no evidence will sway me.' I don't think that's scientific. As an agnostic, I would say I don't think there is clear evidence either way, so it would be silly to take a Dawkinsesque stand on the subject.

Just to draw a parallel with a science issue, take the business of string theory. There is no evidence for string theory - it is totally untestable at the moment. Now the atheist view would be to say 'Because string theory is untestable, I will assume it doesn't have any validity and I will mock people who do think it's worth giving time to. We don't need string theory, we can get along perfectly well without it.' But as an agnostic I would say 'Okay, we don't have evidence either way yet, so let's suspend judgement until we do. I want to hear more about string theory and I will not mindlessly attack it. And frankly it would be very upsetting to all those people who have given their (working) lives to it, so I will be a little more considerate.' I know which sounds the better approach to me.

I have one other problem with this video, which is the section on death. I think all those smug, middle class, wealthy (mostly middle aged) people have a very specific view of how you can make the best of life and enjoy it to the full. It's a bit harder if you are a starving infant expected to die before your first birthday. I think they totally underestimate the comfort that religion has given to many people in dire conditions. This doesn't make religion true - but it does make the humanist view of death, as stated in this video, very much a view that would appeal best to a group of comfortable, privileged intellectuals with a good long life expectancy.

So will I be asking to join the British Humanist Association? I don't think so - but I genuinely thank them for a thought provoking video that raises some serious and important issues.

Okay, what did you think? My feeling after watching it is that I quite like a lot that goes with being a humanist, apart from one huge assumption that all those taking part seem to make, which is that if you are a humanist you must be an atheist. You see, I think the most scientific religious viewpoint to take is to be an agnostic, and I don't see any conflict with being a humanist.

If you are an atheist you say 'I refuse to be open minded. I KNOW what the truth is and no evidence will sway me.' I don't think that's scientific. As an agnostic, I would say I don't think there is clear evidence either way, so it would be silly to take a Dawkinsesque stand on the subject.

Just to draw a parallel with a science issue, take the business of string theory. There is no evidence for string theory - it is totally untestable at the moment. Now the atheist view would be to say 'Because string theory is untestable, I will assume it doesn't have any validity and I will mock people who do think it's worth giving time to. We don't need string theory, we can get along perfectly well without it.' But as an agnostic I would say 'Okay, we don't have evidence either way yet, so let's suspend judgement until we do. I want to hear more about string theory and I will not mindlessly attack it. And frankly it would be very upsetting to all those people who have given their (working) lives to it, so I will be a little more considerate.' I know which sounds the better approach to me.

I have one other problem with this video, which is the section on death. I think all those smug, middle class, wealthy (mostly middle aged) people have a very specific view of how you can make the best of life and enjoy it to the full. It's a bit harder if you are a starving infant expected to die before your first birthday. I think they totally underestimate the comfort that religion has given to many people in dire conditions. This doesn't make religion true - but it does make the humanist view of death, as stated in this video, very much a view that would appeal best to a group of comfortable, privileged intellectuals with a good long life expectancy.

So will I be asking to join the British Humanist Association? I don't think so - but I genuinely thank them for a thought provoking video that raises some serious and important issues.

Published on July 31, 2012 23:15

Hanging with the Gecko

This is the third in my Nature's Nanotech series also featured on www.popularscience.co.uk

If you’ve ever seen gecko walking up a wall, it’s an uncanny experience. Okay, it’s not a 40 kilo golden retriever, but we are still talking about an animal weighing around 70 grams that can suspend itself from a smooth wall as if it were a fly. For a gecko, even a surface like glass presents no problems. This is nature’s Spiderman.

It might be reasonable to assume that the gecko’s gravity defying feats were down to sucker cups on its feet, a bit like a lizard version of a squid, but the reality is much more interesting. Take a look at a gecko’s toes and you’ll see a series of horizontal pads called setae. Seen close up they look like collections of hairs, but in fact they are the confusingly named ‘processes’ – very thin extensions of the tissue of toe which branch out into vast numbers of nanometer scale bristles.

It might be reasonable to assume that the gecko’s gravity defying feats were down to sucker cups on its feet, a bit like a lizard version of a squid, but the reality is much more interesting. Take a look at a gecko’s toes and you’ll see a series of horizontal pads called setae. Seen close up they look like collections of hairs, but in fact they are the confusingly named ‘processes’ – very thin extensions of the tissue of toe which branch out into vast numbers of nanometer scale bristles.

These tiny projections add up to a huge surface area that is in contact with the wall or other surface the gecko decides to encounter. And that’s the secret of their glue-free adhesion. Because the gecko’s setae are ideally structured to make the most of the van der Waals force. This is a quantum effect resulting from interaction between molecules in the gecko’s foot and the surface.

We are used to atoms being attracted to each other by the electromagnetic force between different charged particles. So, for example, water molecules are attracted to each other by the hydrogen bonding we saw producing spherical water droplets in the previous feature. The relative positive charge on one of the hydrogen atoms is attracted to the relative negative charge on an oxygen. But the van der Waals force is a result of additional attraction after the usual forces that bond atoms together in molecules and hydrogen bonding have been accounted for.

Because of the strange quantum motion of electrons around the outside of an atom, the charge at any point undergoes small fluctuations – van der Waals forces arise when these fluctuations pair up with opposite fluctuations in a nearby atom. The result is a tiny attraction between each of the nanoscale protrusions on the foot and the nearby surface, which add up over the whole of the foot to provide enough force to keep the gecko in place.

Remarkably, if every single protrusion on a typical gecko’s foot was simultaneously in contact with a surface it could keep a heavy human in place – up to around 133 kg. In fact the biggest problem a gecko has is not staying on a surface, but getting its foot off. To make this possible its toes are jointed unusually and it seems to secrete a lubricating fluid that makes it easier to detach its otherwise dry but sticky pads.

Not surprisingly, there is a lot of interest in making use of gecko-style technology. After all, master this approach and you have a form of adhesion that is extremely powerful, yet doesn’t deteriorate with repeated attaching and detaching like a conventional adhesive. A number of universities have been researching the subject.

The first publication seems to have been from the University of Akron in Ohio, where a paper in 2007 described a gecko technology sticky tape with four times the sticking power of a gecko’s foot, meaning fully deployed gecko-sized pads could hold up around half a tonne. With these on its feet, a 40 kilogram golden retriever would have no problem walking up walls – the only difficulty would be managing to apply enough force to detach its paws as it walked. In the tape, the gecko’s setae are replaced by nanotubes of carbon fibre which are attached to a sheet of flexible polymer, acting as the tape.

The great thing about carbon nanotubes, which are effectively long, thin, flexible carbon crystals, is that they can be significantly narrower than the smallest protrusions from a gecko’s foot. A typical nanotube has a diameter of a single nanometer – pure nanotechnology – maximising the opportunity for van der Waals attraction. Within a year, other researchers at the University of Dayton (Ohio again!) were announcing a glue with ten times the sticking power of the gecko’s foot.

Such adhesives are available commercially on a small scale, offering the ability to stick under extreme temperature conditions and to surfaces that are wet or flexible that would defeat practically any conventional adhesive. We can expect to see a lot more gecko tapes (like the Geckskin product) and gecko glues in the future.

There have been other theories to explain the mechanism of the gecko’s foot, including a form of capillary attraction, but the best evidence at the moment is in favour of van der Waals forces. This seems to be borne out by the problem geckos have sticking to Teflon – PTFE has very low van der Waals attractiveness. To find out more about the gecko’s foot (and other technological inspirations from nature) I would recommend the aptly titled The Gecko’s Foot by Peter Forbes.

The action that keeps a gecko in place is a dry application of natural nanotechnology, but the more you look at the nanotech biological world, the more you realize it’s mostly a wet world. In the next feature in this series we’ll look at why conventional ‘dry’ engineering often won’t work on nanoscales and how we need to take a different look at the way we build our technology, bringing liquids into the mix.

Image from Wikipedia

If you’ve ever seen gecko walking up a wall, it’s an uncanny experience. Okay, it’s not a 40 kilo golden retriever, but we are still talking about an animal weighing around 70 grams that can suspend itself from a smooth wall as if it were a fly. For a gecko, even a surface like glass presents no problems. This is nature’s Spiderman.

It might be reasonable to assume that the gecko’s gravity defying feats were down to sucker cups on its feet, a bit like a lizard version of a squid, but the reality is much more interesting. Take a look at a gecko’s toes and you’ll see a series of horizontal pads called setae. Seen close up they look like collections of hairs, but in fact they are the confusingly named ‘processes’ – very thin extensions of the tissue of toe which branch out into vast numbers of nanometer scale bristles.

It might be reasonable to assume that the gecko’s gravity defying feats were down to sucker cups on its feet, a bit like a lizard version of a squid, but the reality is much more interesting. Take a look at a gecko’s toes and you’ll see a series of horizontal pads called setae. Seen close up they look like collections of hairs, but in fact they are the confusingly named ‘processes’ – very thin extensions of the tissue of toe which branch out into vast numbers of nanometer scale bristles.These tiny projections add up to a huge surface area that is in contact with the wall or other surface the gecko decides to encounter. And that’s the secret of their glue-free adhesion. Because the gecko’s setae are ideally structured to make the most of the van der Waals force. This is a quantum effect resulting from interaction between molecules in the gecko’s foot and the surface.

We are used to atoms being attracted to each other by the electromagnetic force between different charged particles. So, for example, water molecules are attracted to each other by the hydrogen bonding we saw producing spherical water droplets in the previous feature. The relative positive charge on one of the hydrogen atoms is attracted to the relative negative charge on an oxygen. But the van der Waals force is a result of additional attraction after the usual forces that bond atoms together in molecules and hydrogen bonding have been accounted for.

Because of the strange quantum motion of electrons around the outside of an atom, the charge at any point undergoes small fluctuations – van der Waals forces arise when these fluctuations pair up with opposite fluctuations in a nearby atom. The result is a tiny attraction between each of the nanoscale protrusions on the foot and the nearby surface, which add up over the whole of the foot to provide enough force to keep the gecko in place.

Remarkably, if every single protrusion on a typical gecko’s foot was simultaneously in contact with a surface it could keep a heavy human in place – up to around 133 kg. In fact the biggest problem a gecko has is not staying on a surface, but getting its foot off. To make this possible its toes are jointed unusually and it seems to secrete a lubricating fluid that makes it easier to detach its otherwise dry but sticky pads.

Not surprisingly, there is a lot of interest in making use of gecko-style technology. After all, master this approach and you have a form of adhesion that is extremely powerful, yet doesn’t deteriorate with repeated attaching and detaching like a conventional adhesive. A number of universities have been researching the subject.

The first publication seems to have been from the University of Akron in Ohio, where a paper in 2007 described a gecko technology sticky tape with four times the sticking power of a gecko’s foot, meaning fully deployed gecko-sized pads could hold up around half a tonne. With these on its feet, a 40 kilogram golden retriever would have no problem walking up walls – the only difficulty would be managing to apply enough force to detach its paws as it walked. In the tape, the gecko’s setae are replaced by nanotubes of carbon fibre which are attached to a sheet of flexible polymer, acting as the tape.

The great thing about carbon nanotubes, which are effectively long, thin, flexible carbon crystals, is that they can be significantly narrower than the smallest protrusions from a gecko’s foot. A typical nanotube has a diameter of a single nanometer – pure nanotechnology – maximising the opportunity for van der Waals attraction. Within a year, other researchers at the University of Dayton (Ohio again!) were announcing a glue with ten times the sticking power of the gecko’s foot.

Such adhesives are available commercially on a small scale, offering the ability to stick under extreme temperature conditions and to surfaces that are wet or flexible that would defeat practically any conventional adhesive. We can expect to see a lot more gecko tapes (like the Geckskin product) and gecko glues in the future.

There have been other theories to explain the mechanism of the gecko’s foot, including a form of capillary attraction, but the best evidence at the moment is in favour of van der Waals forces. This seems to be borne out by the problem geckos have sticking to Teflon – PTFE has very low van der Waals attractiveness. To find out more about the gecko’s foot (and other technological inspirations from nature) I would recommend the aptly titled The Gecko’s Foot by Peter Forbes.

The action that keeps a gecko in place is a dry application of natural nanotechnology, but the more you look at the nanotech biological world, the more you realize it’s mostly a wet world. In the next feature in this series we’ll look at why conventional ‘dry’ engineering often won’t work on nanoscales and how we need to take a different look at the way we build our technology, bringing liquids into the mix.

Image from Wikipedia

Published on July 31, 2012 04:23

July 26, 2012

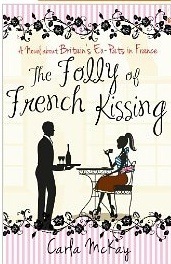

In which we go bonkers in the Languedoc

I quite often get asked if I'd like a book for review. If it's not self published and it's a science book, it's usually an easy yes. With fiction, it's very much a matter of whether or not it tickles my fancy - hence the review a while ago of

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children

. So when I received the offer of Carla McKay's The Folly of French Kissing, not an obvious choice of reading for me, I at least weighed up the pros and cons.

I quite often get asked if I'd like a book for review. If it's not self published and it's a science book, it's usually an easy yes. With fiction, it's very much a matter of whether or not it tickles my fancy - hence the review a while ago of

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children

. So when I received the offer of Carla McKay's The Folly of French Kissing, not an obvious choice of reading for me, I at least weighed up the pros and cons.On the plus side it was set it France, which I love, and the puff comments ('The Gallic equivalent of something out of Midsomer Murders...') caught my eye. I like a touch of murder if it's British in feel, and this was an ex-pat novel. On the downside it really wasn't the kind of book I usually read (and the cover, according to the chick-lit convention, seems to suggest it's aimed at women).

Now the publisher did themselves no favours sending me a bound proof to review. I hate reading from bound proofs - they don't look and feel right (this one had a blank white cover), and there's always something irritatingly wrong with the text - in this case a whole repeated page (which I hope didn't make it to the printed version). But I persevered and on the whole I'm glad I did. It's a novel of three parts.

At the beginning, when we're being introduced to the ex-pats we'll find in an obscure part of the Languedoc, and how they got there, it's a bit slow. I also was beginning to worry this was a self-published book, as there were a few writing issues that needed some stern editing (more than the requisite zero adverbs, for example). But once we got into the main middle section the style picked up a little and the plot got some pace. Before long I was tearing through it, wanting to find what happened next. For older readers I could best describe it as a girlie version of Leslie Thomas - a lighter touch, but a similar feel in many respects. Like Thomas there was a slight tendency to 2D secondary characters - there was a bluff northerner who was straight out of central casting - but the main characters were quite well drawn.

Then came the final section where the strings were drawn together. I found this a little disappointing as it seemed rushed and a little calculating.

Altogether it was interesting to dive beneath a chick-lit cover, something I would never normally do. The Midsomer Murders hint was entirely misleading - there is crime in it, but not in the way that would give you to expect - but on the whole I enjoyed the experience of The Folly of French Kissing. Ideal for a hot weather, lightweight summer read. See at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com

Published on July 26, 2012 23:59

July 25, 2012

Time to pull on the Lycra

It's Royal Society of Chemistry podcast time again, and hard though I may try, I can't totally ignore the Olympics.

It's Royal Society of Chemistry podcast time again, and hard though I may try, I can't totally ignore the Olympics.What does 'The Olympics' say to the compound-loving chemist? The achievement? The national pride? No! The Lycra. We may mock the weekend cyclists puffing along in their shiny Lycra shorts, but the fact is it's an essential these days for many sports. And Lycra turns up in some surprising places. So maybe it's time to slip into something stretchy and find out more. Take a listen.

Published on July 25, 2012 23:32