Brian Clegg's Blog, page 133

October 4, 2012

Physics lessens (sic)

The book is for teachers, but primary

The book is for teachers, but primarychildren need to get why physics is funThere has been much talk in the news of late, thanks to an IoP report showing how few girls are taking physics at A level. The fuss arises because we are in serious need of more physics graduates for science, engineering and business alike. This seems to be the prime driver per se. As one of my daughters pointed out, you don't hear much moaning about how few boys take textiles at A level, so it's more about utility than equality. (Which is fair enough.)

However, I think if we want more people doing physics A levels and degrees (and we do!) we need to address the rot much earlier. I've just reviewed a physics book for primary school children. As a book it's fine, but the content, driven by the curriculum, is rubbish.

The first problem is that it is pure Victorian science. We teach primary school children the basics as they were understood well over a hundred years ago. There are two problems with this. You don't teach them English by giving seven-year-olds classic texts, you use modern catchy stuff - but we still get the dull old droning stuff about friction and mechanics and such. Mechanics is important stuff, of course, just as Shakespeare is in English - but why not start with the weird and wonderful stuff to grab their attention? The other problem is that you want to get the fundamentals in place. What the curriculum fails to recognise is that all the fundamentals of physics changed in the twentieth century.

The second problem (in part because of that Victorian viewpoint) is that what we do teach often verges on being wrong. So, for instance, electricity and magnetism are treated totally separately. Light is often just considered as 'rays', but after that purely as waves. Mirrors, we are told, flip left and right. No they don't. And so on.

Those who justify the current crappy curriculum have two arguments. One is that the children can't understand complicated stuff like relativity and quantum theory and modern cosmology and particle physics. This is just, to use the technical teaching term, bollocks. I don't often resort to bad language, but I have to here, because the premise is so offensive, condescending and ridiculous. I regularly expose primary children to all these areas and they lap it up. It's where all the exciting stuff is, after all. It is perfectly possible to teach relativity, for example, in a way that eight-year-olds can totally get it.

The second argument is that the teachers in primary school don't understand complicated stuff like relativity and quantum theory and modern cosmology and particle physics. This is certainly the biggest barrier to effective teaching of physics in primary schools. Most primary teachers do not have a science background. They are more comfortable with potato prints than Large Hadron Colliders. They will certainly need some handholding to get them past their own blockages until they too realize this stuff isn't complicated and scary at the level they will be presenting it.

The first step, I would suggest, then, is to change the primary school science curriculum and to re-educate primary teachers so they can do physics justice. I have a rather nice little book, Getting Science which gives primary school teachers the basics they need - but without that curriculum change we haven't a hope because most won't bother. It's not what they are supposed to teach.

Let's be clear about this. At the moment, primary school children, who could be fired up with excitement about physics are taught that it is mostly rather dull stuff about materials and friction and forces, with an uninspiring bit of light, sound, electricity and magnetism thrown in. If instead they were taught it was the most amazing, mind-boggling stuff, full of particles that can be in two places at once, and time travel, and big bangs creating a universe that is 94% missing... maybe, just maybe, fewer children would drop the subject as soon as they could.

Published on October 04, 2012 00:52

October 3, 2012

The spam fairy

Blogs traditionally suffer from a fair number of spam comments, which try (feebly) to look like real comments, but are really just there to include a link to their own website. I didn't realize just how much this happened until I changed the www.popularscience.co.uk website into a format that allowed comments on each page and got absolutely inundated - probably at least 10 spam comments a day.

So I signed up to a spam blocking service that's well-integrated with the WordPress environment I now use for that website. For months, all those comments were slammed into a holding area by the blocking service and I could see them building up more and more. But then they just stopped coming. For weeks now there hasn't been a single one. Somehow, the spam fairy is catching them before the blocker gets its hands on them.

I thought initially that this was down to a change of approach by the blocker, simply trashing the spam rather than displaying its trophies. But now I'm not so sure.

The thing is, I subscribe to the comments on this blog as an RSS feed, meaning I get alerted whenever someone makes a comment, so I can come back with a snide (sorry, supportive) reply. What is really weird is that I am still getting the spam posts here (the spam blocker isn't on this site) - they turn up in the RSS feed - but the spam fairy is deleting them before I get to the actual blog to do anything about them. They have just disappeared.

I really have no idea what is happening and where this beneficial help is coming from. Can I stop paying for the spam blocking service, thanks to the spam fairy? I really don't know!

Just to show you the kind of thing I receive, particularly because I love the wording of this one, here is the latest spam comment for this blog, as seen in my RSS reader, but which simply isn't there when I go to the blog. Don't you just love that sentence? Eat your heart out, James Joyce.

So I signed up to a spam blocking service that's well-integrated with the WordPress environment I now use for that website. For months, all those comments were slammed into a holding area by the blocking service and I could see them building up more and more. But then they just stopped coming. For weeks now there hasn't been a single one. Somehow, the spam fairy is catching them before the blocker gets its hands on them.

I thought initially that this was down to a change of approach by the blocker, simply trashing the spam rather than displaying its trophies. But now I'm not so sure.

The thing is, I subscribe to the comments on this blog as an RSS feed, meaning I get alerted whenever someone makes a comment, so I can come back with a snide (sorry, supportive) reply. What is really weird is that I am still getting the spam posts here (the spam blocker isn't on this site) - they turn up in the RSS feed - but the spam fairy is deleting them before I get to the actual blog to do anything about them. They have just disappeared.

I really have no idea what is happening and where this beneficial help is coming from. Can I stop paying for the spam blocking service, thanks to the spam fairy? I really don't know!

Just to show you the kind of thing I receive, particularly because I love the wording of this one, here is the latest spam comment for this blog, as seen in my RSS reader, but which simply isn't there when I go to the blog. Don't you just love that sentence? Eat your heart out, James Joyce.

Published on October 03, 2012 00:17

October 2, 2012

Magnetic moment

Taken in a break on my visit to LichfieldI very much enjoyed appearing at the Lichfield festival on Sunday to speak about Build Your Own Time Machine. At the end of the talk, I opened things up to questions, as usual offering to discuss not only the subject of my talk, but any aspect of physics or science communication. And I came a bit of a cropper.

Taken in a break on my visit to LichfieldI very much enjoyed appearing at the Lichfield festival on Sunday to speak about Build Your Own Time Machine. At the end of the talk, I opened things up to questions, as usual offering to discuss not only the subject of my talk, but any aspect of physics or science communication. And I came a bit of a cropper.I'm generally able to answer the typical questions that arise on abstruse topics like relativity or quantum theory. I cope, on the whole, with the latest news stories - I've lost count of queries about the LHC and Higgs bosons or, a little while ago, faster than light neutrinos (remember them?). But the ones that tend to catch me out have a habit of being questions that rely more on the kind of basic physics I've not had to think about for a long time. And the one that tripped me up on Sunday was just such a question. It was about magnetism.

The questioner asked why is that a (permanent) magnet doesn't run out of energy. After all, it seems to be able to hold a piece of metal up against the force of gravity indefinitely.

I could answer part of the question. If you think of the magnet attracting a piece of metal up off the ground, then keeping it in the air, it only takes energy to move the metal. Keeping it in place takes no energy. It can be useful to think of what happens with gravity, as it's something we're more familiar with than magnetism. If I lift a ball off the floor and put it on a table, I do work (use energy) to lift the ball against the pull of gravity. But once the ball is on the table there is no energy being used to keep it there. How could there be? Where would it be coming from? Out of the table? Then surely the table would some how drain away?

We tend to be fooled into thinking there is an exertion of energy required just to hold something up because if we imagine holding a heavy object up for a long time ourselves, our arms would begin to ache more and more and eventually we would have to drop it - but this is all about human physiology, not physics.

That leaves us with the energy needed for the magnet to lift the piece of metal in the first place. Where did that come from? This is what threw me at the time, and I was only able to prevaricate. It's tempting to think that somehow the energy is coming out of the magnet, so if it lifted things often enough it would run out. But that's wrong. Once again this is a case where thinking of the case of gravity can be helpful.

If I lift something off the Earth, then let go, there is energy required to move that object. I put the energy into the system when I lift it, the energy is then 'released' when I let go to propel it back to Earth. Potential energy from its position in the gravitational field is translated into kinetic energy of movement. Exactly the same goes for the magnet. The potential energy the piece of metal has from its position in the magnetic field is translated into the kinetic energy of movement. The energy is not somehow sucked out of the magnet to propel the metal.

I think the reason it's fairly obvious with gravity, but less so with magnetism is that our experience tends to be inverted. On the Earth we usually lift things up against gravity's pull, then let go. The only things that get placed in the Earth's gravitational field from outside (the aspect that confuses us with a magnet) tend to be meteors and other space debris. By contrast, with the magnet we are usually putting the piece of metal in from the outside, so it is less obvious that we are giving it potential energy than if we start with the metal stuck to the magnet and drag it away before letting go.

I am sure I will be caught out again this way. When you are thinking on your feet, unless you are working in a subject day to day, it's easy to get into rabbit-in-the-headlights mode and fail to come with a sensible answer. But it won't stop me giving that open request for questions. What I've got to work on is saying 'I'm not sure, I'll check and get back to you,' rather than woffling as I tend to...

Published on October 02, 2012 00:22

October 1, 2012

The unbearable heaviness of being Welsh

Eight booklets? No, just four, twice.I'm not Welsh, but the title of this post refers to a reflection that to do business in Wales seems to carry a painful overhead.

Eight booklets? No, just four, twice.I'm not Welsh, but the title of this post refers to a reflection that to do business in Wales seems to carry a painful overhead.Over the last couple of years I've been working with an excellent project called CIME which has been bringing the sort of business creativity support than can usually only be afforded by big companies to micro-businesses in the south west corner of Wales.

The project has just finished, and as part of the wind up, a pack was produced with a booklet on the different contributors with hints on creativity, plus three well-written booklets on creativity techniques and applications by consultant Derek Cheshire. These are very professionally produced and look extremely smart, and probably quite expensive.

Read all about me...

Read all about me...Anywhere else, that would be it. But because it's Wales they have had to duplicate all the documentation in Welsh. So instead of getting a pack of four booklets, you get eight booklets. Whatever your language, half of those are going straight in the bin. But more to the point, I can appreciate the value of the Welsh language, but I think to be so rigid about requiring all this kind of documentation to be bi-lingual is simply a huge waste of money.

It's fine if we are talking government forms - but it's a different matter for booklets from a project like this. There needs to be more flexibility, the option to choose whether to go for a single language or both, depending on your audience.

... in Welsh

... in WelshAs it happens, this project was funded by the EU, so had plenty of money for this kind of thing (in itself, perhaps an indictment of EU projects) - but, really, Welsh people. Would you rather your money was spent on duplicating every document in sight, or on services like schools and health? Just wondering.

For that matter, just think of the impact on the environment. Half these booklets you can absolutely guarantee are going to be thrown away without being looked at. That's really thinking of the environment, isn't it?

Since this was the finale of CIME, I'll leave you with a fun video from one of my sessions featuring the 'visual minutes' taken by a couple of enterprising art students.

Published on October 01, 2012 00:25

September 28, 2012

Looping the Looper

Since writing How to Build a Time Machine/Build Your Own Time Machine, time travel has been a particular interest for me, so I was delighted to be offered a chance to have a preview of the new movie Looper a few weeks ago. (No spoilers in the first part of this piece.)

Since writing How to Build a Time Machine/Build Your Own Time Machine, time travel has been a particular interest for me, so I was delighted to be offered a chance to have a preview of the new movie Looper a few weeks ago. (No spoilers in the first part of this piece.)The premise is an interesting one. In the future, criminals send people they want to get rid of back in time around 30 years. There a hired killer shoots them as they arrive. But part of the contract is knowing that eventually the person who gets sent back with you. At that point the killer gets enough money to retire on and has 30 years left. But, of course, things get complicated when our hero, Joe, faces the future version of himself. (I'm not sure how he knows it's him as there is no resemblance, but hey.)

I'll give you some general feelings here, safe, if you are going to see the movie, and then some detailed comments after the spoiler break. It's being promoted as this decade's Matrix. I think that's wrong - for me that accolade could only be applied to Inception. But I know why they've said it. Looper is good at combining exciting action with bits where you have to think a bit. And segments of it are downright clever. I think they could have made more of the possibilities for Inception like multi-layered action, but is still works well and I would highly recommend it if you like science fiction action movies with a little more thought that a typical Arnie movie. Certainly streets ahead of the recent remake of Total Recall.

The spoilers come after this trailer:

-

-

-

-

-

-

SPOILERS!

-

-

-

-

-

There are some lovely ideas in this movie. I like the concept of the killer finishing his contract by killing himself. There was some real poignancy in Bruce Willis losing his memories of his wife as young Joe's future changes as a result of old Joe's presence in the past. And the time travel comes close to making logical scientific sense. There's one big science fact error - it is loudly announced that time travel hasn't been invented, but it will be. The implication is people are travelling back to a point before time travel has been invented, which isn't possible. But I like to think this is the director/writer Rian Johnson setting us up for a Looper 2 where it turns out that time travel really had been invented earlier.

One weird thing was the telekinesis aspect. It has nothing to do with the rest of the plot - I just can't see the point of it. Should have been binned unless it too is primarily for future movies.

I had more trouble with a couple of basic logic issues. The whole point of the looper system is that it's not safe to kill people in the future as you will definitely get caught, so they send people back thirty years to kill them there. But we see them kill Bruce Willis's wife quite casually in the future. Why doesn't this present the same problem? If they can get away with this, they can find an easier way to get away with other killings than sending people into the past.

Small physical quibble. The blunderbuss used to kill the victims would not send the bodies flying back. Simple Newtonian physics, guys. I know a lot of movies get this wrong, but it's poor science.

The other big logic problem is over the use of resets. Fairly early on, young Joe is killed. Then the action just restarts a little earlier. The (sensible) implication is that if he was dead his future self couldn't come back, so the chain of events would never have started. That's fine, though it is presented in a rather confusing way. But the denouement involves young Joe killing himself to stop old Joe from killing others people. Why didn't this also cause a reset? It's inconsistent.

One lovely idea I've never seen before was that the young versions of loopers could communicate with the old version by carving a message on their arms to leave a scar. This is brilliant - the only slight problem with the execution is that the old loopers suddenly realize the message is there, where actually they would have known about it for 30 years.

I'm nitpicking here, but detail can make a lot of difference to a science-driven movie like this. I know it is fiction, and I'm quite happy for science to be distorted to fit the storyline - but it doesn't do any harm to point out where it went wrong. Overall, though, I really enjoyed the movie and it even occasionally made me think, which can't be bad.

Published on September 28, 2012 01:51

September 27, 2012

Who's for a little Nookie?

All the ebooks I can eat on my iPadThere is little doubt - e-readers and ebooks are finally taking off. Whether pure e-readers like the original Kindle or tablets like the iPad, more and more people are reading books in this format. While I would scatter a little fairy dust of doubt over statistics that Amazon puts out comparing how many ebooks it sells with paper (bear in mind their ebook sales probably include all free downloads, which is a lot), there is no doubt that the market is finally becoming serious. Using the not-entirely-always-accurate service Novelrank, I can roughly compare sales on Amazon of my latest book that's both on Kindle and in paper format -

The Universe Inside You

. Roughly speaking it is selling twice as many ebook copies as paper.

All the ebooks I can eat on my iPadThere is little doubt - e-readers and ebooks are finally taking off. Whether pure e-readers like the original Kindle or tablets like the iPad, more and more people are reading books in this format. While I would scatter a little fairy dust of doubt over statistics that Amazon puts out comparing how many ebooks it sells with paper (bear in mind their ebook sales probably include all free downloads, which is a lot), there is no doubt that the market is finally becoming serious. Using the not-entirely-always-accurate service Novelrank, I can roughly compare sales on Amazon of my latest book that's both on Kindle and in paper format -

The Universe Inside You

. Roughly speaking it is selling twice as many ebook copies as paper.So the market is ripe for lots of different ebook readers, hence presumably the launch of US bookstore giant Barnes & Noble's Nook tablets alongside its e-readers in the UK. Only I'm not totally convinced. iPad and Kindle dominate their respective markets. There are some up and coming Android tablets. But a lot of also ran makes like Kobo and even the mighty Sony have struggled to really get out there. And I suspect it may also be true of Barnes & Noble.

The thing is, B&N is a big name in the US, but it's an unknown here. If they had branded it Waterstones, it may just have got a bit more credibility, but as it stands I'm not sure why anyone will buy them, unless they are seriously cheap for what they offer. They will be selling through Sainsbury's, which should get them some sales, and Blackwell's. But I am just not sure they will catch on in a big way.

There are probably interesting parallels to draw with the MP3 player market. Apple was not first with the iPod, but they have dominated the market ever since they first got properly established. Sony could have got there first (remember how dominant the Walkman was on the cassette side), but messed up by making the PC software to go with their MP3s very clumsy and obtrusive (their ebook products have had the same problem). Now on the MP3 front you have Apple, then a couple of also rans like Sandisk, then the tat. I think the same is likely to be the case with ebook readers. The top slots are already filled. Barnes & Noble will fighting to make sure they're an also ran.

Published on September 27, 2012 00:39

September 26, 2012

Midsomer Madness

A meteorite that went nowhere near a black holeIt can be highly entertaining when a drama series attempts to incorporate science into the plot, so last night I watched Midsomer Murders, and the entertainment came thick and fast.

A meteorite that went nowhere near a black holeIt can be highly entertaining when a drama series attempts to incorporate science into the plot, so last night I watched Midsomer Murders, and the entertainment came thick and fast.In this particular case, the science in question was astronomy. We started with a dramatic scene. A total eclipse of the Sun. Many folk from kids to serious astronomers are gathering to a witness it. I was a little unhappy with the advice an expert gave a youngster (roughly 'don't look at it through binoculars or a telescope...' so far so good... 'unless you use one of these filters.' Not so good.) But we'll overlook that. What, though, about the eclipse itself? These don't happen randomly, after all.

From the car registrations this clearly wasn't the last eclipse visible in the UK in 1999. Anyway, while the location of Midsomer isn't specified (it's filmed in Buckinghamshire and Berkshire), it clearly isn't Cornwall. And the next... is not until 2090. Hmm.

This falls into the 'irritating but possibly allowable to keep the story going' class. But the next one was a doozie. In a conversation with Inspector Barnaby, an astronomy professor is musing over the meteorite that killed someone during the eclipse. (Don't ask.) I nearly literally rolled on the floor laughing. So wonderful was it that I have gone back on ITVPlayer to get an exact transcript of his words.

There's megatons of metal floating around out there. Carbon compressed to its deepest density, sucked into black holes. Which is probably where our own planet will end its days.What?!? There are not words to describe the awe I feel at the magnificent incorrectness of that little speech. What black holes? If the carbon was sucked into them, how did it get out again? No, it's not 'probably where our own planet will end its days.' Lovely.

One other example that raised a snigger. One of the amateur astronomers who had supposedly discovered an extra-solar planet (yes, I know) is asked for an alibi during another murder. It was nighttime and, like most astronomers he was observing. Good alibi. But then he has to go and give some detail that spoils it. I haven't bothered finding the exact words but it was approximately 'I was watching the transit of Venus.' Marvellous. Leaving aside the fact that this is a much rarer event than a solar eclipse, there's one big problem. Like eclipses, transits of Venus are one of the few times when astronomers get to work during the day. It's Venus crossing the face of the Sun. It happens in daytime. So not exactly a great nighttime alibi. For one brief moment I thought this might be intentional, a subtle hint that this was the killer. But no. It was just a script error.

On one level, moaning about this kind of thing is nerdy silliness. It's a story, get over it. But on another level it is perfectly legitimate. Making a two hour drama is an expensive business. They could have afforded a few hundred pounds to have someone who knew their science look over the script. (I'm available, TV people!) The eclipse itself we'd let through, because it was fairly central to the plot, and so it's fine to bend the facts. But the dialogue that went horribly wrong could easily have been made accurate without any impact on the storyline. Surely they could have managed that?

Image from Wikipedia

Published on September 26, 2012 00:38

September 25, 2012

The P word

There has been a lot of fuss lately over what the Chief Whip Andrew Mitchell did or didn't say to a policeman at Downing Street. Leaving aside that I have some sympathy with Mitchell, as he wasn't talking to a policeman as defender of liberty, but rather a policeman as jobsworth refusing to do his job and open a gate, I find the reaction to one word fascinating.

Mitchell is accused by the policeman (though he denies it) of calling him a pleb. This is being treated by parts of the media as if he had used the N word - but I would say there is a fundamental difference. I absolutely understand why those who take offence from the use of the N word get upset, because it links them to an unpleasant historical context. This isn't the case for pleb.

'Pleb' is short for 'plebeian' from the Roman distinction between a plebeius - one of the common people - and a patricius, a patrician, a member of the nobility or (post classically) a high ranking official. Practically everyone was a pleb. So basically what Mitchell (if he said it) was accusing the policeman of being was one of what our US cousins tend to call 'We the people'. Not a waste of space, toffy-nosed idiot, but the salt of the earth. And this is offensive because?...

Of course, you might argue that it's not offensive in itself, but rather in the way it is typically used by a certain class of people. They (we could class them as Bullingdon Club types) consider themselves a cut above the rest, and consider the plebs to be oiks, the ones who didn't go to Eton or have some minor title in the family. But to take offence is to suggest that these idiots are right. And they aren't. Given the choice between Bullingdon Club types ('hearties' we used to call them at university, and it wasn't intended as a compliment either) and being a pleb, I know which I'd choose. My grandparents were mill workers from Rochdale. What else could I be? Plebeian and proud of it.

Up the plebs!

Mitchell is accused by the policeman (though he denies it) of calling him a pleb. This is being treated by parts of the media as if he had used the N word - but I would say there is a fundamental difference. I absolutely understand why those who take offence from the use of the N word get upset, because it links them to an unpleasant historical context. This isn't the case for pleb.

'Pleb' is short for 'plebeian' from the Roman distinction between a plebeius - one of the common people - and a patricius, a patrician, a member of the nobility or (post classically) a high ranking official. Practically everyone was a pleb. So basically what Mitchell (if he said it) was accusing the policeman of being was one of what our US cousins tend to call 'We the people'. Not a waste of space, toffy-nosed idiot, but the salt of the earth. And this is offensive because?...

Of course, you might argue that it's not offensive in itself, but rather in the way it is typically used by a certain class of people. They (we could class them as Bullingdon Club types) consider themselves a cut above the rest, and consider the plebs to be oiks, the ones who didn't go to Eton or have some minor title in the family. But to take offence is to suggest that these idiots are right. And they aren't. Given the choice between Bullingdon Club types ('hearties' we used to call them at university, and it wasn't intended as a compliment either) and being a pleb, I know which I'd choose. My grandparents were mill workers from Rochdale. What else could I be? Plebeian and proud of it.

Up the plebs!

Published on September 25, 2012 01:34

September 24, 2012

Where's my Streetview?

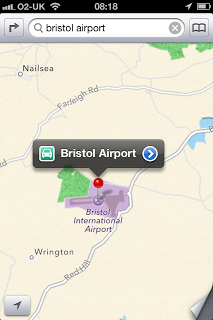

Find me Bristol Airport and make

Find me Bristol Airport and makeit snappy (the new Maps app)There has been a lot of excitement in the Apple world in recent days with the launch of iPhone 5 and suchlike goodies. To accompany it, there has been an outbreak of new software - specifically iOs 6, the new version of the iPhone/iPad operating system.

As usual this has quite a few nice goodies, but also one hugely controversial feature. Apple has replaced the excellent Google Maps with their own software. The Apple Maps app has some very swish 'fly over' features, which are toys that will be used twice and discarded. But it isn't as good as the old master on some of the basics.

There has been much whingeing about the new app, as the occasional place gets mislaid etc, but I suspect that will be fixed fairly quickly. They are relying on TomTom for much of the UK mapping, and on the whole TomTom know their stuff. And they have added turn by turn directions, which is potentially useful.

However, there is one particularly painful aspect of the change. I always found Google Streetview really useful. You can take a look at your destination and be clear exactly how the end of your journey looks. But there is no Streetview in Apple Maps. No worries - you can still go into Google Maps in the web browser... only Streetview uses Flash, which isn't supported on iPhone or iPad. So still no opportunity to have a quick preview of your destination.

Oh, that's what it looks like (Live Street View)Thankfully there is a little app called Live Street View which is dirt cheap (there is a free version, but I'd recommend paying the 69p both to reward the developer and to avoid the adverts, which take up valuable screen space) and which displays those essential views in native mode, so all is well.

Oh, that's what it looks like (Live Street View)Thankfully there is a little app called Live Street View which is dirt cheap (there is a free version, but I'd recommend paying the 69p both to reward the developer and to avoid the adverts, which take up valuable screen space) and which displays those essential views in native mode, so all is well.Phew.

Published on September 24, 2012 00:32

September 21, 2012

What is it about BMWs?

A BMW, it seemsIf I'm honest I am not a big fan of BMWs. I can't imagine every buying one: while I know at least two really nice people who drive them, I experience an awful lot more unpleasant people driving them. They seem to be more pushy, nasty drivers for some reason. And for that matter, there isn't a BMW model where there isn't another car I'd rather have.

A BMW, it seemsIf I'm honest I am not a big fan of BMWs. I can't imagine every buying one: while I know at least two really nice people who drive them, I experience an awful lot more unpleasant people driving them. They seem to be more pushy, nasty drivers for some reason. And for that matter, there isn't a BMW model where there isn't another car I'd rather have.However, even as a non-fan, I have to have admit that BMWs are superbly engineered - which is why I am so baffled about their attitude to security. Recently in the news there has been a lot of fuss about BMWs with those automatic key fob thingies being easy to break into. Despite being aware of this, apparently BMW don't feel it's their responsibility to sort things out. Which isn't good.

Of itself, this is a one-off concern. But the fact is it's not the first time BMWs have been identified as being easy to break into. A good number of years ago, my car was broken into in a car park in Windsor. (You may think Windsor is a nice place, but I've only had cars broken into twice, both times in Windsor.) The thieves smashed a window to get a few cassette tapes and the (rubbish) car radio. My car wasn't a BMW - but I learned something interesting that night.

A policewoman came out to examine the scene. In conversation she pointed out that, in a way, it was a pity that my car wasn't a BMW as they were so easy to break into. Apparently, she said, there was a fault in the automatic locking mechanism, and if you bashed a BMW just there (she indicated on a nearby example) the locks popped open. For her benefit I won't say whether or not she actually demonstrated it, but it was painfully easy. Of course that was back then - this doesn't work on today's cars. But even so, as Lady Bracknell might have said, to mess up one locking mechanism is unfortunate; to mess up two is careless.

Image from Wikipedia

Published on September 21, 2012 02:44