Brian Clegg's Blog, page 129

December 3, 2012

The Christmas Music dilemma

I was on BBC Wiltshire with the excellent Mark O'Donnell on Saturday, and a topic of discussion was whether to play a Christmas song or a winter song (as it was a bit early for Christmas stuff). What was interesting in this discussion, as so often is the case, was the hinterland.

There was significant debate over whether a song that doesn't mention Christmas, or Christmas specific appurtenances like Santa Claus and Rudolph, but that is traditionally associated with Christmas is a Christmas song or a winter song. Think Frosty the Snowman, Let it Snow or Winter Wonderland. Okay, we're in 'how many angels can dance on the head of a pin' territory, but hey, it's December.

Personally I was strongly in favour of letting these through as winter songs. But it led me to think of another Christmas music dilemma. I'm a great fan of church music, both singing it and listening to it - and I love carols. Now, technically we are currently in Advent, the season leading up to Christmas - the equivalent of Lent before Easter. And there is plenty of good Advent music. So there is an argument that you should only sing Advent music until Christmas begins at midnight on 24 December. But...

But, I think most people would agree, that Christmas carols seem limp and out of place after around 26 December. It would be ridiculous to limit ourselves to singing and hearing these brilliant bits of music to one day. So reluctantly I have to say, I think it's okay to go with the carols from the start of December. Ding Dong away, folks. Ding Dong away.

Just in case you think all carols are crass, here's an example of a high class Christmas carol - Peter Warlock's Bethlehem Down. Nice story too. Warlock (real name Philip Heseltine) and his friend Bruce Blunt wanted to get drunk over Christmas. They had no cash, so they ran off this little number to pay for the festivities. And here's the thing you couldn't imagine today. The Daily Telegraph published it - sheet music and all - on Christmas Eve 1927.

There was significant debate over whether a song that doesn't mention Christmas, or Christmas specific appurtenances like Santa Claus and Rudolph, but that is traditionally associated with Christmas is a Christmas song or a winter song. Think Frosty the Snowman, Let it Snow or Winter Wonderland. Okay, we're in 'how many angels can dance on the head of a pin' territory, but hey, it's December.

Personally I was strongly in favour of letting these through as winter songs. But it led me to think of another Christmas music dilemma. I'm a great fan of church music, both singing it and listening to it - and I love carols. Now, technically we are currently in Advent, the season leading up to Christmas - the equivalent of Lent before Easter. And there is plenty of good Advent music. So there is an argument that you should only sing Advent music until Christmas begins at midnight on 24 December. But...

But, I think most people would agree, that Christmas carols seem limp and out of place after around 26 December. It would be ridiculous to limit ourselves to singing and hearing these brilliant bits of music to one day. So reluctantly I have to say, I think it's okay to go with the carols from the start of December. Ding Dong away, folks. Ding Dong away.

Just in case you think all carols are crass, here's an example of a high class Christmas carol - Peter Warlock's Bethlehem Down. Nice story too. Warlock (real name Philip Heseltine) and his friend Bruce Blunt wanted to get drunk over Christmas. They had no cash, so they ran off this little number to pay for the festivities. And here's the thing you couldn't imagine today. The Daily Telegraph published it - sheet music and all - on Christmas Eve 1927.

Published on December 03, 2012 00:34

November 30, 2012

In the Night Lab

It's that time again when it becomes respectable to dig out your Christmas CDs as tomorrow the great chocolate countdown begins. (Hands up who can remember advent calendars without chocolate? Boring, weren't they?) Yes, despite my repeated cries of 'Bah, Humbug', I have to give and get a quick coating of tinsel.

A number of years ago, on my old blog on Nature Network, a miniature masterpiece evolved. It was an 'anyone can contribute a line' poem, based on 'Twas the Night Before Christmas' but set in a lab. Yes, folks, this is both lab lit and evolutionary poetry. I feel it deserves to be preserved (indeed pickled), so I like to dig it out on a regular basis.

For those who like their pomes read out (here with sound effects by the excellent Graham Steel), here it is:

And for those who are members of the campaign for real written words, here it is in all its glory:

Twas the night before Christmas and all through the lab

Not a Gilson was stirring, not even one jab.

On the bench, ’twixt a novel by Jennifer Rohn

And the paper rejected by Henry’s iPhone

Lay a leg, still trembling and covered in gore

And Frankenstein sighed ‘I can’t take this no more’.

He exclaimed panic struck, as he took in the scene,

of horrendous results from NN’s latest meme.

‘having one extra leg wasn’t part of the plan

to create a new species, anatomized man’.

And then out of the blue, ‘twas a bump in the night

A girrafe ’pon a unicycle, starting a fight

Held back by a keeper all smiling with glee,

It was then that I knew that it was Santa Gee.

His iphone, it jingled, his crocs were so pink,

It was all I could do to stammer and blink.

‘There you are’ cursed old Frank’stein, approaching the Gee,

‘Call off the girrafe, and hand over the fee.’

“The Beast” then leaped up, from O’Hara’s new leg

Attacked Santa Gee and his elf, Brian Clegg.

One sweep of the sack and the beast was laid out

When hoof of girrafe gave a terminal clout.

Then its leg fell off quaintly, with a sad little ‘plonk’,

Santa Gee, from his sled, gave a loud, angry honk

And the mask on his face slipped – sadly ’twas loose -

To reveal not a man but a fat Christmas Goose.

To Frankenstein’s horror, the bird reared up high

He realized then that this goose could not fly.

So he grabbed the elf Clegg, who stood by buggy-eyed

and hoisting him up with great gusto he cried:

“O’Hara and Beast, I have them at last.

Sprinkle on Ritalin, for a tasty repast.”

But five minutes had lapsed, so the beast was asleep

Having dreams that were complex, clever and deep:

Half warthog, half carrot? What would look nice?

Half girrafe, half O’Hara? Yes! Made in a trice.

He dreamed a solution, to this horrid scene:

Unite the spare legs! To waste them is mean!

Much later that evening, the creature awoke!

One Bob-leg, one g’raffe leg! He rose up and spoke:

“Beloved creator, I wish you’d not meddle,

My unicycle now needs a quite different pedal."

Like all truly great works of art, it helps to have some background knowledge. The named persons were all contributors to Nature Network. 'The Beast' is Bob O'Hara's cat. And for obscure reasons 'a unicycling girrafe [sic]' was an in-joke.

A number of years ago, on my old blog on Nature Network, a miniature masterpiece evolved. It was an 'anyone can contribute a line' poem, based on 'Twas the Night Before Christmas' but set in a lab. Yes, folks, this is both lab lit and evolutionary poetry. I feel it deserves to be preserved (indeed pickled), so I like to dig it out on a regular basis.

For those who like their pomes read out (here with sound effects by the excellent Graham Steel), here it is:

And for those who are members of the campaign for real written words, here it is in all its glory:

Twas the night before Christmas and all through the lab

Not a Gilson was stirring, not even one jab.

On the bench, ’twixt a novel by Jennifer Rohn

And the paper rejected by Henry’s iPhone

Lay a leg, still trembling and covered in gore

And Frankenstein sighed ‘I can’t take this no more’.

He exclaimed panic struck, as he took in the scene,

of horrendous results from NN’s latest meme.

‘having one extra leg wasn’t part of the plan

to create a new species, anatomized man’.

And then out of the blue, ‘twas a bump in the night

A girrafe ’pon a unicycle, starting a fight

Held back by a keeper all smiling with glee,

It was then that I knew that it was Santa Gee.

His iphone, it jingled, his crocs were so pink,

It was all I could do to stammer and blink.

‘There you are’ cursed old Frank’stein, approaching the Gee,

‘Call off the girrafe, and hand over the fee.’

“The Beast” then leaped up, from O’Hara’s new leg

Attacked Santa Gee and his elf, Brian Clegg.

One sweep of the sack and the beast was laid out

When hoof of girrafe gave a terminal clout.

Then its leg fell off quaintly, with a sad little ‘plonk’,

Santa Gee, from his sled, gave a loud, angry honk

And the mask on his face slipped – sadly ’twas loose -

To reveal not a man but a fat Christmas Goose.

To Frankenstein’s horror, the bird reared up high

He realized then that this goose could not fly.

So he grabbed the elf Clegg, who stood by buggy-eyed

and hoisting him up with great gusto he cried:

“O’Hara and Beast, I have them at last.

Sprinkle on Ritalin, for a tasty repast.”

But five minutes had lapsed, so the beast was asleep

Having dreams that were complex, clever and deep:

Half warthog, half carrot? What would look nice?

Half girrafe, half O’Hara? Yes! Made in a trice.

He dreamed a solution, to this horrid scene:

Unite the spare legs! To waste them is mean!

Much later that evening, the creature awoke!

One Bob-leg, one g’raffe leg! He rose up and spoke:

“Beloved creator, I wish you’d not meddle,

My unicycle now needs a quite different pedal."

Like all truly great works of art, it helps to have some background knowledge. The named persons were all contributors to Nature Network. 'The Beast' is Bob O'Hara's cat. And for obscure reasons 'a unicycling girrafe [sic]' was an in-joke.

Published on November 30, 2012 00:35

November 29, 2012

Beware the average

Which one's the average house?I was struck by an item on the local news this morning saying that the average house price in the UK was £163,910 according to the Nationwide Building Society. This seemed a dubious statistic. Why? Because the average (or mean) is not a good measure of a distribution that isn't symmetrical. It's highly misleading. That's because the vast majority of houses in the UK are worth less than the average house price - and that is downright confusing.

Which one's the average house?I was struck by an item on the local news this morning saying that the average house price in the UK was £163,910 according to the Nationwide Building Society. This seemed a dubious statistic. Why? Because the average (or mean) is not a good measure of a distribution that isn't symmetrical. It's highly misleading. That's because the vast majority of houses in the UK are worth less than the average house price - and that is downright confusing.Let's look at a simpler example to see what's going on. Imagine we have a room full of people and take their average earnings. Then we throw Bill Gates into the room. Bill's vast income would really bump up the average - so probably everyone else in the room would earn less than the average. The new average would not be representative of the room as a whole.

The reason a relatively small number of cases (in our room, Bill) can have a big impact is because the distribution - the spread of the incomes - is not symmetrical. Let's say the average income before Bill entered the room was £26,000 a year. Then the absolute maximum anyone can fall below that average is by £26,000. But there is no limit to how far above the average you can be. In Bill's case, he will be millions higher. So he has a much bigger impact on the average than a poor person does.

In such cases, the median is a very valuable number to know. This is just the middle value. We put all the people in a row in order of earnings and pick the middle number. With a distribution like our room - or house prices - the median gives us a much better feel for what a typical value is like than the average.

Which takes us back to the Nationwide. I took the liberty of dropping their Chief Economist, Robert Gardner an email and he was kind enough to call me back within 10 minutes (and to email through some bumf). You really wouldn't expect a financial institution to make such a basic statistical mistake... and they haven't. What the Nationwide repeatedly calls an average in their press releases isn't a simple average at all. Instead they stratify the data according to region, type of house and so forth and produce a rather messy weighted figure that could arguably be said to be the typical value - but it certainly isn't an average.

You can argue whether they should be rather clearer about just what the figure they are producing is, rather than calling it the average house price as they do, but at least it is a meaningful figure.

In other statistics, I'm afraid the press simply gets the words wrong. Quite often a government bureau will publish a median value and an average - they do so on earnings, for instance. What the media often does is to take the median value, because it's more meaningful, but calls it the average (presumably because they think the poor public can't cope with a hard word like 'median'). That's just bad journalism.

This distortion of the average is something that politicians wishing to attack another party and not being too scrupulous about their statistics can use to their advantage. If we want to tax those on high earnings and find the tax hits someone on the average wage, then there is an outcry, because that seems to imply that it hits the majority of ordinary people – but the majority actually earn less than the average wage. The naughty politician can play the numbers even more effectively by putting two people on an average wage into a household. Now we are not only using individuals that earn more than most, but a household where both partners do so. This pushes their collective income up so high that it puts the household in the top 25 per cent of all households, even though we are talking about two people who are on an average wage.

There's a simple message. Whenever you hear 'average' in statistics on the news or see them presented, it's worth taking the numbers with a pinch of salt unless you can verify just what lies behind that value.

Published on November 29, 2012 02:03

November 28, 2012

Turing's statue

There is a Turing statue in Manchester, but frankly

There is a Turing statue in Manchester, but franklyit's unrecognisable. You can do better, guys.There is nothing editors like more than anniversaries. Recently I suggested a feature to a magazine. 'It could work,' they said, 'as long as you can find an anniversary to tie it to. We need a hook.' Frankly, this is a load of rubbish. The reading public really doesn't care why a magazine or newspaper is coming up with a particular story as long as it's interesting. But editors feel they have to devise a justification. They need a reason that a particular story should be used, so they arbitrarily use the factor of a significant date. It keeps them happy, bless them.

This being the case, we can expect a flood of books on Alan Turing as it was the 100th anniversary (wey-hey!) of his birth in June. Leaving aside the fact Turing would certainly have preferred a binary anniversary (2018 will be the 1000000th anniversary of his death), I'm currently reading the first of these books for review. I don't want to talk about that book itself here (it's Turing: Pioneer of the Information Age by Jack Copeland ) as it will be reviewed on popularscience.co.uk very soon - suffice it to say it's shaping up well - but I would like to shamelessly steal what appears to be Jack Copeland's thesis.

This is that the remarkable things we remember Turing for are probably his lesser contributions to the world. Many know that Turing was one of the leading codebreakers dealing with the Enigma and Tunny machines at Bletchley Park during the Second World War. And we may well remember Turing's contributions to the idea of artificial intelligence, with the 'Turing test' that is supposed to show whether or not a computer can pass itself off as a human being. And the tragic end to his life, committing suicide after being handled terribly by the ungrateful authorities (who should have been treating him like a national hero) because he was a homosexual. But there is even more to this remarkable man who, in his biography, sometimes comes across a little like Sheldon in The Big Bang Theory.

Arguably the reason we should really remember Turing is that at the most fundamental level he invented the modern computer. Forget Babbage - well, no don't forget him, but cast him, as Copeland does as grandfather of the computer. It was Turing that dreamed up the real thing. In a sense it was just a throwaway initially. His theoretical universal computing machine was devised as a way of exploring an abstruse (though important) aspect of mathematics. But as Turing himself came to realise, this was much more. In effect, what Turing did was invent computer science. Pretty well everything else everyone else has done that is labelled 'computer science' is the engineering to put Turing's vision into practice. Turing's work was the 'theory of everything' of computing.

Companies like IBM, Apple, Microsoft and Google should be putting up statues in his honour all around the world faster than you can say 'serious profits.'

Published on November 28, 2012 00:58

November 26, 2012

Look first, then tell the world

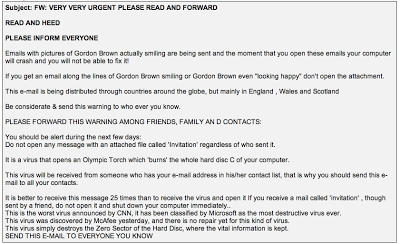

With some regularity I get sent emails about scams, viruses and strange things that Facebook is going to do. Almost always these are accompanied by a request to pass them on the world and its aunty. And there's the thing. Because almost always these dire warnings (some of them very dire) are themselves a form of virus. What they describe is totally fictional, a hoax that by panicking people into spreading the word, reproduces and travels the world. It is this 'chain letter' effect that is, in fact, the awful payload.

Whenever I get these warning emails and Facebook messages my first step is to pop over to Snopes (thanks to Andy Grüneberg for introducing this to me many years ago). Snopes is primarily a way of checking out urban myths, but most of the time these spoof warnings also get a write-up.

So, for instance, I recently got an email from someone, asking me to pass on to everyone I know a warning about cards being left by Parcel Delivery Service. Anyone who rang up to have their parcel redirected got landed with a bill of £315 for making a phone call to a premium rate number. There was, of course, no parcel. This warning is vastly out of date. The scam did exist - but the bill was £9 not £315. More to the point, the number being warned about was deactivated in 2005. It was a real problem (and may well still be with a different name and number) - but the specific warning doing the rounds in 2012 was 7 years out of date. It was a ghost warning, a Flying Dutchman of a warning.

I was also warned about a virus that showed a happy smiling Gordon Brown (okay, that's weird, I admit). PLEASE INFORM EVERYONE said the much copied message. Open the attachment with Gordon's pic and your PC will be trashed by an 'Olympic Torch' that burns your whole hard disc. Don't get me wrong. Viruses exist and can do damage. But whenever you get an email or Facebook message it's worth checking, because chances are that these 'Pass it on to everyone' messages are fakes.

I was also warned about a virus that showed a happy smiling Gordon Brown (okay, that's weird, I admit). PLEASE INFORM EVERYONE said the much copied message. Open the attachment with Gordon's pic and your PC will be trashed by an 'Olympic Torch' that burns your whole hard disc. Don't get me wrong. Viruses exist and can do damage. But whenever you get an email or Facebook message it's worth checking, because chances are that these 'Pass it on to everyone' messages are fakes.

When I've established it's a fake there's the difficult decision. It's not to bad if the warning was simply a Facebook post. You can just add a comment. But it's harder when someone has just sent the warning to everyone in their address book. Do you point out it's a spoof? Probably you should, as really they should be warning all their friends not to pass on this message. But it always seems a bit mean.

So here's the thing. Next time you hear about a terrible email that will make your computer explode if you open it, or the latest phone scam, or Facebook's latest outrageous terms and conditions, pop over to Snopes first (another good source is Hoax Slayer) pop in a few keywords and check it out. You could save yourself time and embarrassment.

Whenever I get these warning emails and Facebook messages my first step is to pop over to Snopes (thanks to Andy Grüneberg for introducing this to me many years ago). Snopes is primarily a way of checking out urban myths, but most of the time these spoof warnings also get a write-up.

So, for instance, I recently got an email from someone, asking me to pass on to everyone I know a warning about cards being left by Parcel Delivery Service. Anyone who rang up to have their parcel redirected got landed with a bill of £315 for making a phone call to a premium rate number. There was, of course, no parcel. This warning is vastly out of date. The scam did exist - but the bill was £9 not £315. More to the point, the number being warned about was deactivated in 2005. It was a real problem (and may well still be with a different name and number) - but the specific warning doing the rounds in 2012 was 7 years out of date. It was a ghost warning, a Flying Dutchman of a warning.

I was also warned about a virus that showed a happy smiling Gordon Brown (okay, that's weird, I admit). PLEASE INFORM EVERYONE said the much copied message. Open the attachment with Gordon's pic and your PC will be trashed by an 'Olympic Torch' that burns your whole hard disc. Don't get me wrong. Viruses exist and can do damage. But whenever you get an email or Facebook message it's worth checking, because chances are that these 'Pass it on to everyone' messages are fakes.

I was also warned about a virus that showed a happy smiling Gordon Brown (okay, that's weird, I admit). PLEASE INFORM EVERYONE said the much copied message. Open the attachment with Gordon's pic and your PC will be trashed by an 'Olympic Torch' that burns your whole hard disc. Don't get me wrong. Viruses exist and can do damage. But whenever you get an email or Facebook message it's worth checking, because chances are that these 'Pass it on to everyone' messages are fakes.When I've established it's a fake there's the difficult decision. It's not to bad if the warning was simply a Facebook post. You can just add a comment. But it's harder when someone has just sent the warning to everyone in their address book. Do you point out it's a spoof? Probably you should, as really they should be warning all their friends not to pass on this message. But it always seems a bit mean.

So here's the thing. Next time you hear about a terrible email that will make your computer explode if you open it, or the latest phone scam, or Facebook's latest outrageous terms and conditions, pop over to Snopes first (another good source is Hoax Slayer) pop in a few keywords and check it out. You could save yourself time and embarrassment.

Published on November 26, 2012 23:44

Getting that vinegary feeling

My latest podcast for the Royal Society of Chemistry is not about some complex biological molecule, or even the sort of serious compound that is treated with respect in the lab. We're talking about an acid that's so weak we're happy to shake it onto our food, whether it's an essential condiment for chips or to give a salad dressing a bite. To be fair, this is because vinegar is only very dilute acetic acid.

My latest podcast for the Royal Society of Chemistry is not about some complex biological molecule, or even the sort of serious compound that is treated with respect in the lab. We're talking about an acid that's so weak we're happy to shake it onto our food, whether it's an essential condiment for chips or to give a salad dressing a bite. To be fair, this is because vinegar is only very dilute acetic acid.But in some ways the most interesting chemicals are the ones we hardly notice, they are such an everyday part of life. So pop along to the RSC compounds site - or if you've five minutes to spare, click to to have a listen to my podcast on vinegar.

Published on November 26, 2012 00:01

November 23, 2012

Sorry, CofE, you have made me angry

Generally speaking, the Church of England is an underrated organization. As religious organizations go it is moderate and caring. CofE vicars do a remarkably good job on the whole in difficult circumstances. The local church still plays a role in its community, particularly when it comes to big events like weddings and funerals. But the recent women bishops debacle was terrible.

What I find bizarre is what has happened is due to an abysmal organizational structure, not in any sense a reflection of the will of the majority. If you look at the Synod, the 'parliament', only one of the 3 houses, the laity (i.e. the ordinary folk) didn't pass the motion for women bishops. But the church also has local synods, based on the diocese structure. Of these, 42 out of 44 supported women bishops. So how was the vote lost? Where's the representation in this?

The anti-vote comes from a strange (some might say un-holy) alliance of the two extreme wings of the church - it's as if the extreme right and the extreme left came together in parliament. The extreme right, the anglo-catholics, basically don't want anything that's different from Roman Catholics, so don't want women priests at all, let alone bishops. The extreme left, the evangelicals, take a very literal view of the Bible as their guide. The trouble is, their interpretation relies on two dubious points. That the Bible is the inerrant word of God, and that you should apply magic.

Let me clarify that. The first bit ignores that a) the Bible most people read is a translation, and b) that was written by men. Like it or not, the Bible and the doctrine of the early church was decided by men with an agenda. It is very clear just from comparing the four gospels, describing the same events in sometimes conflicting fashion, that each book was written to get a particular message across, and slant things accordingly. They are not historically accurate documents, each is worded to establish one particular view. And one faction of the early church very much wanted the message that woman should keep quiet and know their place. It seems pretty clear that Jesus himself was atypical of Jewish attitudes of the period and treated women as equals - but the men who set up the early church were not comfortable with this.

As far as I understand it, the two arguments against women bishops are these. 1) The apostles - the 12 who Jesus set up to pass on the message - were all men, so bishops should be men, and 2) Jesus was a man (can't argue), so priests (let alone bishops) should be men to represent Jesus (that's the magic bit). The first argument is irrelevant. There were female disciples and the only reason we only hear about male apostles is because that's what suited the bible writers, and because it was what worked with the social structures of the time. It doesn't work for the present.

I'm being provocative but accurate when I label that second argument as an appeal to magic. There is no reason why a woman can't represent a man. (My MP has been a woman several times.) The only reason you could argue against a woman is if somehow the magic won't work if a priest/bishop is a woman. That's not right. It's just silly. A representation is a model, it's not the real thing. The fact that Jesus was a man - so what? He was also a Jew. If you take this argument seriously you would only allow Jews to be priests or bishops. Why draw the line at a man? I'm happy for you to say only a human being could represent him, so sorry, no canine applications for bishop. But no women? Give me strength.

My only positive take on all this is that it will be sorted. I can say with some confidence that the Church of England will have women bishops fairly soon. Certainly before the Roman Catholic church has women priests - or Moslem religious organisations have women in positions of authority. I've heard some people say that equality law should apply to the Church of England - and I agree. But only if it also applies to all religions. Good luck with that one.

What I find bizarre is what has happened is due to an abysmal organizational structure, not in any sense a reflection of the will of the majority. If you look at the Synod, the 'parliament', only one of the 3 houses, the laity (i.e. the ordinary folk) didn't pass the motion for women bishops. But the church also has local synods, based on the diocese structure. Of these, 42 out of 44 supported women bishops. So how was the vote lost? Where's the representation in this?

The anti-vote comes from a strange (some might say un-holy) alliance of the two extreme wings of the church - it's as if the extreme right and the extreme left came together in parliament. The extreme right, the anglo-catholics, basically don't want anything that's different from Roman Catholics, so don't want women priests at all, let alone bishops. The extreme left, the evangelicals, take a very literal view of the Bible as their guide. The trouble is, their interpretation relies on two dubious points. That the Bible is the inerrant word of God, and that you should apply magic.

Let me clarify that. The first bit ignores that a) the Bible most people read is a translation, and b) that was written by men. Like it or not, the Bible and the doctrine of the early church was decided by men with an agenda. It is very clear just from comparing the four gospels, describing the same events in sometimes conflicting fashion, that each book was written to get a particular message across, and slant things accordingly. They are not historically accurate documents, each is worded to establish one particular view. And one faction of the early church very much wanted the message that woman should keep quiet and know their place. It seems pretty clear that Jesus himself was atypical of Jewish attitudes of the period and treated women as equals - but the men who set up the early church were not comfortable with this.

As far as I understand it, the two arguments against women bishops are these. 1) The apostles - the 12 who Jesus set up to pass on the message - were all men, so bishops should be men, and 2) Jesus was a man (can't argue), so priests (let alone bishops) should be men to represent Jesus (that's the magic bit). The first argument is irrelevant. There were female disciples and the only reason we only hear about male apostles is because that's what suited the bible writers, and because it was what worked with the social structures of the time. It doesn't work for the present.

I'm being provocative but accurate when I label that second argument as an appeal to magic. There is no reason why a woman can't represent a man. (My MP has been a woman several times.) The only reason you could argue against a woman is if somehow the magic won't work if a priest/bishop is a woman. That's not right. It's just silly. A representation is a model, it's not the real thing. The fact that Jesus was a man - so what? He was also a Jew. If you take this argument seriously you would only allow Jews to be priests or bishops. Why draw the line at a man? I'm happy for you to say only a human being could represent him, so sorry, no canine applications for bishop. But no women? Give me strength.

My only positive take on all this is that it will be sorted. I can say with some confidence that the Church of England will have women bishops fairly soon. Certainly before the Roman Catholic church has women priests - or Moslem religious organisations have women in positions of authority. I've heard some people say that equality law should apply to the Church of England - and I agree. But only if it also applies to all religions. Good luck with that one.

Published on November 23, 2012 00:52

November 22, 2012

Science needs stories

Scientists are fond of moaning about science writers, saying we simplify the science too much. This is sometimes true, though to be fair, some science needs simplification, and it’s better to say something in a simple way that’s not the whole story than to say it in a way that is totally incomprehensible. But historians of science have a different complaint. They reckon we are too fond of stories.

Scientists are fond of moaning about science writers, saying we simplify the science too much. This is sometimes true, though to be fair, some science needs simplification, and it’s better to say something in a simple way that’s not the whole story than to say it in a way that is totally incomprehensible. But historians of science have a different complaint. They reckon we are too fond of stories.So science books, for example, will tell you about Newton’s amazing breakthroughs (quite possibly inspired by an apple falling), or Einstein turning physics on its head. But the historians will grumble and groan saying, ‘No, it was more complicated than that. It wasn’t a straightforward story of one hero making the breakthrough, it was a whole lot of tiny steps, some of them backwards, by a whole range of people, that come together to make the big picture.’

There is an element of truth in this, but it is an argument that’s only any use if you have an audience of computers. People need stories. That’s how we understand the world. And science needs stories if we are to get a wider understanding of science. Because popular science is here to get the story of science across, not the story of history. If we have to slightly simplify history to do this, I think it’s worth it. The fact is, all heroes are human beings with flaws. All processes of scientific discovery are flawed and often piecemeal. But we don’t do harm by making a coherent story of it, we get the message across.

Sometimes the obsession historians have with denying the existence of story can go too far. I’ve seen, for instance, some dismiss the business of Newton and the apple. Yet this story is not based on a book produced after Newton’s death, it’s taken from an account of a conversation with Newton from a (relatively) reliable source. I personally am quite confident that Newton said he was inspired by seeing an apple fall. (Not that one fell on his head – that is rubbish.) Whether he was storytelling himself, of course, we can’t know. But why must we assume that he was? Give the guy a break!

Here’s a different example of a good story being denied by a historian. British physicist Arthur Eddington led an expedition in 1919 to observe a total eclipse of the sun, which was intended to support Einstein’s general relativity. The interesting story popular science writers tend to tell about this is that the observations he took were insufficient to support the idea that Einstein was right – and results from another expedition at the same time told the opposite story. It has since been shown that the instruments used could never have produced values of sufficient accuracy to support or disprove the theory. Now that’s a good story, because it suggests that – as sometimes happens with science – Eddington was so enthusiastic to get the result he wanted that he didn’t worry too much about the experiment.

However, in an article in Physics World magazine in 2005, Eddington biographer and historian Matthew Stanley commented that this is a myth ‘based on a poor understanding of the optical techniques of the time’ and that Eddington did not throw out data that was unfavourable to Einstein. But that was never suggested. The suggestion is, rather, that Eddington based his analysis on too little data, ignored someone else’s contradictory data, and hadn’t good enough equipment to be sure anyway. It’s hard not to assume that Dr. Stanley was a bit too enthusiastic in sticking up for his subject.

Overall, I think historians of science are right that we should allow some ‘warts and all’ into popular science – and from my reading of it, there is more than there used to be. But we will always need stories to help us understand science and its context, and if those stories sometimes oversimplify the history to get to the science I, for one, won’t complain.

This piece first appeared on sciextra.com and is reproduced with permission.

Published on November 22, 2012 00:00

November 21, 2012

They can play 'Happy Days Are Here Again'

We have a friend who has her funeral organized to the last detail - and has had for years. She has written down exactly what she wants to happen and exactly what bits of music she wants to be sung/played when. For all I know, she has probably written out the menu for the post-funeral meal. Perhaps less extreme, at the moment there is a Co Op Funeral Service ad on the TV (am I the only one who thinks this isn't an ideal subject for TV advertising? - if you think differently, you can enjoy some of their funeral ads here) where someone tells us 'My song? It's got to be "I Did It My Way"', referring, of course, to what he wants played at his funeral. I listen to this kind of thing with an eyebrow dramatically raised. Frankly I don't get it.

At my funeral, if those present want to, they can sing Happy Days Are Here Again while hopping round on their left legs playing the ukelele banjo. Or sit in complete silence. Whatever works for them. Surely this is the point. I really won't care myself. Whether you are religious or not, we can surely agree on one thing. I won't be there. So what does it matter to me? It's the people who are left behind who will be struggling to cope, and it's their feelings that will be important.

As long as they are comfortable with whatever happens, as long as it helps them, it will be right thing. I love Tudor and Elizabethan church music. If I were going to a funeral, I would squirm in my seat if I had to listen to a boombox belting out Frank Sinatra - but some tudorbethan music would really help me. But for my own funeral I truly hope that, if there is any music, they use whatever works for them.

So do me a favour. If you are thinking of having your funeral soon and inviting me, forget 'My Way'. Make it something like this. I'd even sing along:

At my funeral, if those present want to, they can sing Happy Days Are Here Again while hopping round on their left legs playing the ukelele banjo. Or sit in complete silence. Whatever works for them. Surely this is the point. I really won't care myself. Whether you are religious or not, we can surely agree on one thing. I won't be there. So what does it matter to me? It's the people who are left behind who will be struggling to cope, and it's their feelings that will be important.

As long as they are comfortable with whatever happens, as long as it helps them, it will be right thing. I love Tudor and Elizabethan church music. If I were going to a funeral, I would squirm in my seat if I had to listen to a boombox belting out Frank Sinatra - but some tudorbethan music would really help me. But for my own funeral I truly hope that, if there is any music, they use whatever works for them.

So do me a favour. If you are thinking of having your funeral soon and inviting me, forget 'My Way'. Make it something like this. I'd even sing along:

Published on November 21, 2012 00:19

November 20, 2012

The Sigil - SF with the bones left in

When I was a teenager I very much enjoyed E. E. 'Doc' Smith's Lensman series. These six novels were, frankly, pretty poorly written - but the sweep of the story arc - the sheer scale of a storyline that spanned over 2 billion years - was astounding. And in some ways, the Sigil trilogy by Henry Gee, which I've just finished reading, has a similar impact (though the writing is considerably better). And yet it's not really 'space opera', because most of the action takes place on Earth.

When I was a teenager I very much enjoyed E. E. 'Doc' Smith's Lensman series. These six novels were, frankly, pretty poorly written - but the sweep of the story arc - the sheer scale of a storyline that spanned over 2 billion years - was astounding. And in some ways, the Sigil trilogy by Henry Gee, which I've just finished reading, has a similar impact (though the writing is considerably better). And yet it's not really 'space opera', because most of the action takes place on Earth.Some of the ideas in these books are astonishing, with the sun threatened by a herd of star-eating phenomena (not exactly living, but sort of) that were created soon after the big bang, an Earth civilization going back millions of years and the discovery of a whole range of hominids other than Homo sapiens still living on Earth, plus an archeological dig uncovering a vast underground city older than any known human civilisation and a massive space battle millions of years ago. That's a whole lot to conjure with.

This is without doubt 'hard' science fiction in the sense that the science plays a central role and as much as possible is real science - though unusually, thanks to Gee's background in palaeontology, there is not just fancy physics but a lot about the development of different hominid species too. And yet these books do not shy away from the softer aspects of life. There's a lot about people in here. And a lot of religion. Somewhat surprisingly, Catholics probably get the best of the deal. You won't be put off you are an atheist - but you do need to be prepared to think a bit about religion, rather than just dismiss it with a Dawkinsian knee-jerk reaction.

There is also sex. Rather a lot of sex. You'll be pleased to know it's no 50 Shades, but there are some fairly explicit scenes and language, so you might think twice before giving it to a 12-year-old. Interestingly quite a lot of the sex is not between humans, but is still made fairly steamy. There is also some stomach-churning description of man's (or at least hominid's) inhumanity to man - one image will stay with me forever, and I'd rather it didn't. So not always a pleasant read - and quite spooky when I happened to get onto a section where Israel is under a massive attack at almost exactly the same time as the latest escalation of violence in the Middle East.

There are things I wish were different. I'm not a great fan of long books, and taking the trilogy as a whole (because it's not really three separate books), it was too long for me. I also found the way chapter-to-chapter it jumps back and forward in time, sometimes millions of years, confusing. I am a bear of little brain when it comes to fiction. Too many flashbacks in a movie or book leave me floundering, and here, pretty well every other a chapter is a flashback to around six different times in the past. In fact at one point, when the main 'current' timeline story was particularly gripping, I confess I skipped an entire flashback chapter just to get on with it.

If I was going to be really picky, I also don't understand how one of the main characters can suddenly pull the whole thing together with an explanation near the end. It's useful, but I don't know how he knows (even though he is the Pope (don't ask)). Overall, though, this is a book I'm really glad I read - and if you like science fiction with a sweeping scale, and can cope with a mix of sex, violence, philosophy and religion in your SF, this is unmissable. I don't want to give too much away, but the central concept is as outrageously impressive as Douglas Adams' idea of the Earth being a computer set up by the mice that is destroyed just before it can come up with an answer (in fact, come to think of it, there are even certain parallels...)

The Sigil comes in three books - Siege of Stars, Scourge of Stars and Rage of Stars, but really it's all one big book which you can buy in one lump (something I'd recommend), either as a paperback or an ebook. You can get it straight from the publisher's site in all formats, or from Amazon.co.uk as paperback, Amazon.co.uk on Kindle (this is individual books, for some reason the single ebook version isn't on Amazon) or Amazon.com as paperback and Amazon.com for Kindle.

Published on November 20, 2012 01:04