Shane K. Bernard's Blog

September 22, 2025

Why Do Cajuns Identify as Cajuns (And Not as Creoles)?

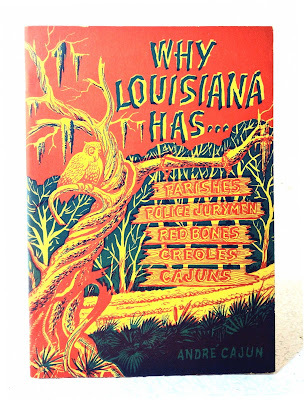

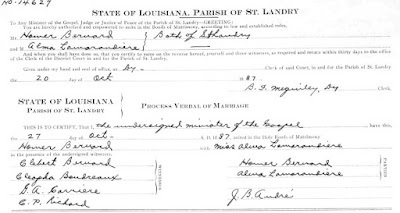

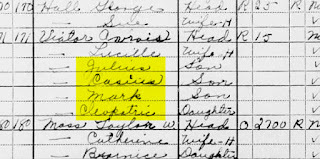

I wrote these works not only as a historian, but as someone who identifies as both a Cajun and a Creole. As I note below, “[M]any of my ancestors were Creoles of French heritage. My own family tree abounds with tell-tale Creole surnames: de la Morandière, Soileau, de la Pointe, Fuselier de la Claire, Brignac, Bordelon, de Livaudais, and others. . . . As such, I could, if I chose to do so (and sometimes I do), identify as Creole — doubly so because Cajuns themselves are to begin with a kind of Creole.”

I trust those with whom I express disagreement will accept this critique in the collegial spirit it is intended.

❧

“Recently, someone asked me, “Why do Cajuns identify as Cajuns?”

This implied other, related questions, namely “Why don’t Cajuns identify as Creoles? Aren’t they a type of Creole?” — as some, including myself, assert.

The short answer is: Like their Acadian ancestors, Cajuns have always viewed themselves as a distinct people. Even from other south Louisiana Creoles.

Not only culturally distinct, but, as importantly, historically distinct.

Poster in downtown Lafayette, La.

Poster in downtown Lafayette, La. (photo by the author, 2024)

Let’s start with a few definitions:

In its broadest sense, the term “Creole” can mean a native-born Louisianian of French-speaking (less commonly Spanish-speaking) Roman-Catholic heritage — a definition without racial connotation. According to this definition, one can be Black, White, or multiracial and still be considered Creole.(1)

As such, some ask “Wouldn’t Cajuns therefore qualify as Creoles?” Because what are Cajuns in a broad sense but native-born Louisianians of French-speaking, Roman-Catholic heritage?

A growing number of Cajuns, Creoles, scholars, and activists accept this notion of Cajun ethnicity. They agree that Cajuns are indeed a kind of Creole.

A kind of Creole — and yet, most would assert, still Cajun.

This might prompt the further inquiry: “Yes, but why do Cajuns continue to see themselves as distinct from other Creoles?” Creoles who today seem eager to welcome Cajuns into their fellowship, but only if, as some Creoles insist, they jettison the “Cajun” label.

In short, the message is “Stop calling yourselves ‘Cajuns,’ start calling yourselves ‘Creoles.’”

Unveiling of the "Flag of the Louisiana Acadians,"

Unveiling of the "Flag of the Louisiana Acadians," late 1960s.

Some who support this idea imply if not outright assert, without evidence, that Cajuns are not a real ethnic group. That Cajun identity came into being only in the late 1960s as a racist response to the Civil Rights Movement. That “Cajun” is therefore a made-up or fake ethnic label.(2) As the person who queried me about Cajun identity declared: “the word [Cajun] doesn’t mean anything.”

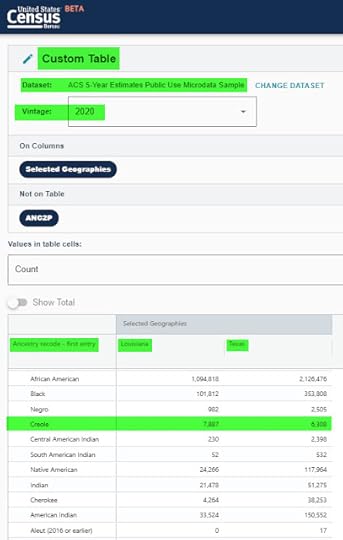

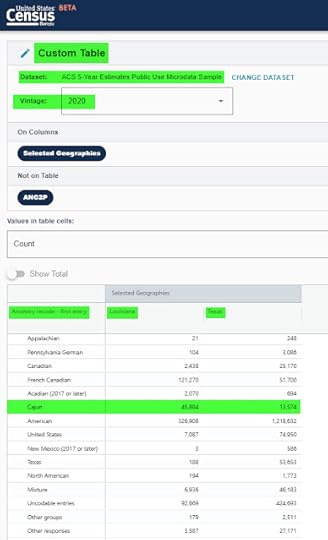

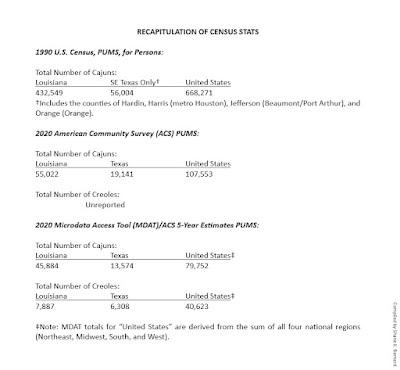

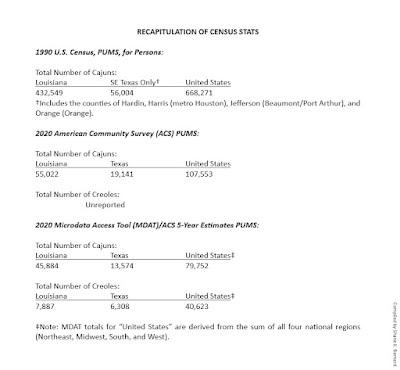

Clearly, however, the word means a great deal to a great many people. According to recent census data, over 107,000 Americans (more than 74,000 of whom reside in Louisiana and, to a lesser extent, Texas) identify their primary ethnicity as “Cajun.” (As an aside, the same census data shows only about 14,000 persons in Louisiana and Texas choosing “Creole” as their primary ethnicity.)(3)

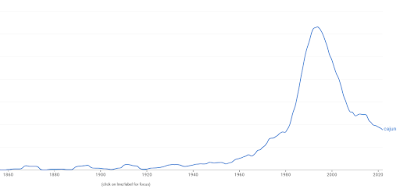

Despite the dubious claim that “Cajun” is “a new identity” dating back only 55 to 60 years, researchers (including me) have shown that the word originated as an ethnic label in English as early as 1862 — and in French as early as 1851.(4) Since then, the label’s use has not only persisted but grown enormously.

Google "Ngram" chart showing use of "Cajun"

Google "Ngram" chart showing use of "Cajun" in books. Note the uptick spurred by the Cajun fad of the 1980s.

(Source: Google Books Ngram Viewer)

And these findings are based solely on printed references. Who knows when the word “Cajun” (whatever its spelling) first sprang into existence purely as a spoken word?

Returning to the core issue “Why do Cajuns identify as Cajuns?”:

Given the size of their population (again, over 107,000), there could be any number of reasons why individuals identify as Cajuns. A theoretical Cajun might have embraced the term because their parents and other relatives identified as Cajuns; because they inherited a surname commonly regarded as Cajun; because they identified closely with other self-identifying Cajuns; because they discovered their Cajun ancestry through family oral traditions, genealogical research, or state-of-the-art DNA testing, among other reasons.

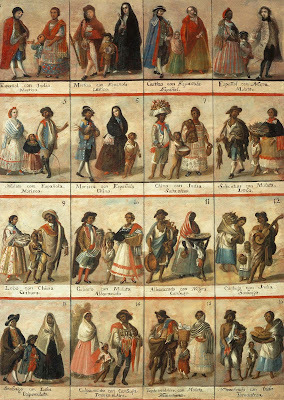

In other words, Cajuns choose to identify as Cajuns for the same reasons other peoples around the globe embrace their identities — whether we speak of present-day Assyrians in the Middle East, the Tagalog people of the Philippines, the Mestizos of Spanish America, or any other group. Including, for that matter, the Creoles of south Louisiana.

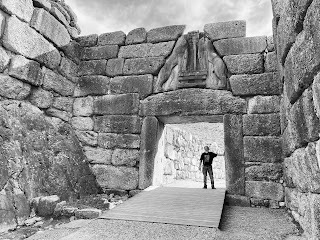

Consider, however, one particularly powerful driving force of ethnic identification: history or, less formally, storytelling — both of which play a vital role in creating group identity and cohesiveness. For example, the story of the Acadian expulsion fits into a long tradition of exile narratives, such as the Romans claiming descent from defeated sea-wandering Trojans, or the Israelites enduring a forty-year exodus from pharaonic Egypt that led them to the Promised Land.(5)

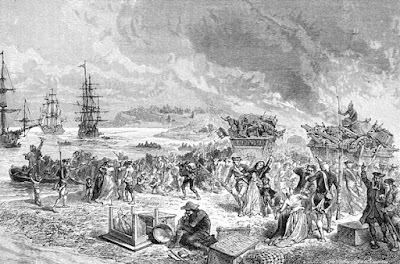

Called Le Grand Dérangement (The Great Upheaval), the Acadians’ tragic exile experience occurred when British redcoats (often New England colonists in service to the Crown) expelled up to 18,000 Acadian men, women, and children. As prisoners, they were shipped to inhospitable locales in England, the thirteen British colonies of North America, the French mainland, the Caribbean, and elsewhere. About a decade later, the first of roughly 3,000 Acadians arrived in south Louisiana, a new homeland they tellingly called Nouvelle Acadie. In time, their descendants would come to be known as the Cajuns.(6)

Carl Brasseaux's important study

Carl Brasseaux's important studyThe Founding of New Acadia.

This exile spread the distinct Acadian identity far and wide, as noted by Carl Brasseaux, author of seminal works about Cajun and Creole history:

[M]ainstream historians of the past 150 years . . . have clearly established that the French colonists of the Bay of Fundy Basin [i.e., Acadia] had forged a new, collective ethnic identity as Acadians long before their expulsion from Canada in 1755. . . . During the ensuing years of exile and wandering, the Acadians were universally regarded by their reluctant hosts [in the places to which they were deported] as a distinct people with a common ethnic identity. That identity clearly remained intact after successive waves of surviving Acadians made their way to Louisiana between 1764 and 1788.(7)

19th-century illustration of the 1755 expulsion

19th-century illustration of the 1755 expulsionof the Acadians.

Cajuns aware of their history regard the expulsion and its aftermath as a painful but defining legacy, one that serves to distinguish them from other ethnic groups. Even from those who endured their own diasporas, as in the case of Creoles of African heritage.(8)

Brasseaux moreover observes, “At the time of their arrival [in south Louisiana] and for decades afterward, the exiles’ ethnicity was clearly and unequivocally recognized by established Louisianians, including proto-Creoles, who clearly viewed the immigrants as the ‘other.’”

Another book by Brasseaux (et al.).

Another book by Brasseaux (et al.).Indeed, Creoles in the late 19th and early 20th century — white Creoles, but Creoles nevertheless — worked to distance themselves from, and exclude, Cajuns. As an 1881 federal census study maintained, “The Creoles proper will not share their distinction with the native descendants of those worthy Acadian exiles who . . . found refuge in Louisiana. These remain “cadjiens” or “cajuns”. . . .” As late as 1939 one scholar observed, “[The Creoles] often had a word for the poorer Cajuns: ‘Canaille!’ — that was their way of saying poor-white trash.”(9)

Brasseaux adds, “This does not mean that, after centuries of evolutionary adaptation to the same physical and cultural landscapes, there were not similarities. . . .”

So, yes, Brasseaux says, the Cajuns are similar to other south Louisiana groups. Similar, yet distinct.

Furthermore, modern evidence reveals legal and genetic proof of Cajuns separateness. In 1980 a U.S. federal court, per the lawsuit Roach v. Dresser, established that Cajuns are a people of “foreign descent” and thus protected from discrimination by the Civil Rights Act of 1964. As the presiding judge stated, “By affording coverage under the ‘national origin’ clause of Title VII [of the Civil Rights Act] he [the Cajun] is afforded no special privilege. He is given only the same protection as those with English, Spanish, French, Iranian, Czechoslovakian, Portuguese, Polish, Mexican, Italian, Irish, et al., ancestors.”(10)

My 2003 book The Cajuns:

My 2003 book The Cajuns:Americanization of a People.

Meanwhile, scientists identified a distinctive “Cajun genotype” traced to the early Acadians’ common origins in southwest France. Acadians and Cajuns both compounded this trait through intermarriage, a practice encouraged by generations of remote settlement patterns. As I wrote in my book, The Cajuns: Americanization of a People (University Press of Mississippi, 2003):

“John P. Doucet, a molecular geneticist at Nicholls State University . . . and other scientists studied genetic diseases that affected Cajuns more prevalently than the general population. These ailments included Friedreich’s ataxia, Tay-Sachs disease, and Usher syndrome. Interest in this new scientific field led to . . . DNA research at Tulane University that uncovered a common Cajun genotype — further evidence that Cajuns are indeed a bona fide ethnic group. . . .”(11)

So there you have it: Cajuns identify as Cajuns because they have always viewed themselves as a distinct people. And the reason they have viewed themselves as distinct is not merely cultural, but historical — a history in which observers not only categorized them as separate, but, as Brasseaux notes, one in which 19th-century white Creoles excluded them as undesirable "others." The Cajuns' distinct sense of identity has only been reinforced in recent decades by legal and genetic evidence.

As I have written before, today’s moral consensus demands we respect others’ professed identities and reject erasure in all its execrable forms. Is it therefore fitting that some would tell Cajuns their identity — one existing in the historical record for at least 175 years — is “meaningless”? Or should we respect how others choose to identify, put aside past and present enmities, and work together for mutual benefit, as many scholars, activists, and others have been doing for decades?

Notes

(1) For more information, see my previous essay: Shane K. Bernard, “Of Cajuns and Creoles: A Brief Historical Analysis,” Bayou Teche Dispatches, 13 February 2022, http://bayoutechedispatches.blogspot.com/2019/06/of-cajuns-and-creoles-brief-historical.html, accessed 22 September 2025.

(2) Shane K. Bernard, “Born of ‘Elite’ White Reactionism?: Assessing Claims about the Rise of Cajun Ethnicity,” Bayou Teche Dispatches, 5 May 2022, https://bayoutechedispatches.blogspot.com/2022/05/born-of-elite-white-reactionism.html, accessed 22 September 2025.

(3) Shane K. Bernard, “Disappearing Cajuns and Creoles? Ethnic Identity and the Limits of Census Data,” Bayou Teche Dispatches, 20 June 2024, http://bayoutechedispatches.blogspot.com/2024/06/cajuns-creoles-and-limits-of-census-data.html, accessed 22 September 2025.

Self-identification is by far the most common method of declaring one’s ethnic affiliation. Indeed, short of genetic testing and meticulous genealogical research — which some people consider deeply personal and extremely private — what other method of ethnic identification is there? Reliance on self-identification — practiced routinely, for example, by the U.S. Census Bureau — admittedly carries the possibility of error, even deception. It assumes, however, that most claimants respond in good faith and with some degree of accuracy.

(4) Shane K. Bernard, “Notes on the Birth of Cajun Ethnic Identity,” Bayou Teche Dispatches, 12 February 2022, http://bayoutechedispatches.blogspot.com/2020/09/notes-on-birth-of-cajun-ethnic-identity.html, accessed 22 September 2025.

Some counter that “Cajun” was used in south Louisiana solely as a negative term prior to the birth of the Cajun pride movement in the 1960s. They also claim “Cajun” was used solely as a catch-all term for any poor White French-speaker, no matter their culture or heritage. Yet analysis of 19th- and 20th-century primary-source evidence reveals a more complex, more nuanced use of “Cajun.” While negative occurrences of the word “Cajun” certainly exist — some of them scathing — so, too, do positive and neutral ones. Likewise, while “Cajun” was sometimes applied to all poor French-speaking Whites, it was also commonly used to denote those who descended from Acadian exiles. In short, the issue of how “Cajun” was used in the past is by no means monolithic.

Evangeline.

Evangeline.(5) Some might argue that the Acadian exile hardly merits comparison to such momentous events. Yet it remains a story so powerful and emotive that Longfellow — described as “for more than a century, the most famous poet in the English-speaking world” — adapted the Acadian exile as the basis for his epic poem Evangeline. A poem, as I have elsewhere noted, “Generations of schoolchildren memorized . . . alongside Byron, Tennyson, and Shakespeare.” A poem that inspired Broadway and Hollywood productions, as well as a veritable Evangeline cult centered on St. Martinville, Louisiana. See Shane K. Bernard, Teche: A History of Louisiana's Most Famous Bayou (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2016), pp. 5-6.

(6) Carl A. Brasseaux, “Scattered to the Wind”: Dispersal and Wanderings of the Acadians, 1755-1809 (Lafayette, La.: The Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Southwestern Louisiana [now University of Louisiana at Lafayette], 1991), p. 67, Table VI; ____________, The Founding of New Acadia: The Beginnings of Acadian Life in Louisiana, 1765-1803 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987), p. 91. In the former, Brasseaux places the number of Acadian exiles in colonial Louisiana at about 2,600. In the latter, however, he places the number at “2,600 to 3,000.”

One critic accuses present-day Cajuns and some who write their history of “romanticizing” the expulsion. The critic in question does not explain what is romantic about an event marked by disease, starvation, exposure, and outright physical violence — an event resulting in a roughly 55-percent mortality rate that claimed up to 10,000 Acadian lives. See John Mack Faragher, A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from their American Homeland (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), pp. 469-471. Faragher writes, “The Acadian entry in the book of the dead is staggering: in July 1755 they numbered eighteen thousand persons in the maritime region. Over the next eight years an estimated ten thousand exiles and refugees lost their lives as a direct result of the campaign of expulsion” (pp. 470-71).

Faragher's Great and Noble Scheme.

Faragher's Great and Noble Scheme.(7) All Brasseaux quotes in this essay derive from Carl A. Brasseaux, Lafayette, La., to Shane K. Bernard, New Iberia, La., 9 May 2022, email correspondence in Bernard’s possession.

(8) One might ask “What about persons of African heritage who, because of interracial relations, share the Cajuns’ genetic fingerprint and possibly also their language, music, foodways, and other cultural markers, right down to their Cajun surnames? Should they not be considered ‘Cajun’?” There is no denying a racial element to Cajun identity. As I have shown, despite claims to the contrary, Cajuns and their Acadian ancestors have historically been considered “White.” Regardless, I believe someone of both Acadian and African ancestry should be free to identify as Cajun. Indeed, there is no legitimate reason they should not identify as Cajun, if they so choose. I would, however, never tell someone how to identify: that is a choice they should decide for themselves, and their decision should be respected.

(9) George E. Waring Jr. and George W. Cable, History and Present Condition of New Orleans, Louisiana: Social Statistics of Cities, Tenth Census of the United States (Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior/U.S. Government Printing Office, 1881), 10; Shields McIlwaine, The Southern Poor-White from Lubberland to Tobacco Road (Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1939), p. 143.

(10) Shane K. Bernard, The Cajuns: Americanization of a People (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2003), pp. 136-37; ____________, “Calvin J. Roach v. Dresser Industrial Valve and Instrument Division,” 64 Parishes, 19 January 2023, https://64parishes.org/entry/calvin-j-roach-v-dresser-industrial-valve-and-instrument-division, accessed 22 September 2025; James Harvey Domengeaux, “Native-Born Acadians and the Equality Ideal,” Louisiana Law Review 46 (July 1986): 1152, 1158, 1159-60, 1194-95, passim.

(11) Bernard, The Cajuns, p. 147.

July 21, 2025

Notes on Emancipation in Louisiana, 1863-1865

The short answer is that slavery in Louisiana ended between the enactment of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, and the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on December 6, 1865.

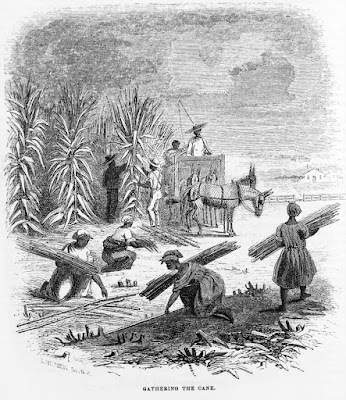

Enslaved sugarcane field workers in south Louisiana.

Enslaved sugarcane field workers in south Louisiana.Source: Harper's Monthly (1853)

Yet the question demands a more complicated response.

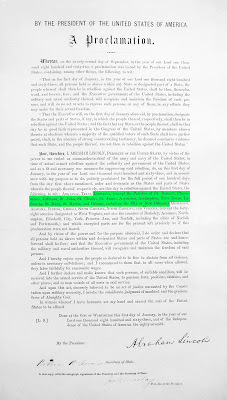

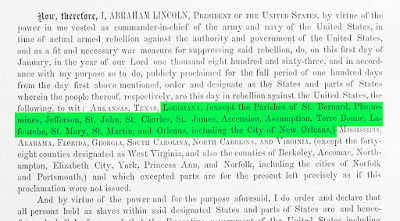

While the U.S. government dealt with the status of enslaved persons in the Confiscation Acts of 1861 and 1862 and the Captured and Abandoned Property Acts of 1863, those measures permitted Union troops to seize and free enslaved persons only under very specific conditions.(1) It was the Emancipation Proclamation, however, that aimed to free enslaved persons en masse. Yet a reading of the Proclamation reveals — much to the surprise of many who have never examined it, at least not in detail — that U.S. President Abraham Lincoln excluded from its effects by name the Louisiana parishes (counties) of, to quote the Proclamation itself, “St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James, Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans. . . .”

Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation (1863)

Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation (1863)with exempted parishes highlighted.

Source: Lincoln Presidential Library

(click to enlarge)

The question then arises, “Why did Lincoln exclude these parishes from the Proclamation?”

Many American historians declare that Lincoln excluded these parishes because they were “Union-held” and, as is commonly known, the Proclamation freed the enslaved only in areas held by Confederate forces. Thus, as one historian notes, “Lincoln’s critics were quick to . . . claim that the Proclamation had never freed anyone at all. ‘Where he has not power Mr. Lincoln will set the negroes free; where he retains power he will consider them as slaves,’. . .” Others, the same historian observes, strongly disagreed: “No one should ‘for a moment imagine that the Emancipation Proclamation had no force in law,’ warned one abolitionist. ‘By that instrument three millions of slaves were legally set free.’”(2)

It is telling that contemporary observers expressed such opposing views about the document’s impact. Today, historians continue to evaluate the subject. Yet the reason for Lincoln’s exclusion of those thirteen Louisiana parishes has been overlooked or explained away rather dubiously.

Section of the Emancipation Proclamation

Section of the Emancipation Proclamationexempting certain south Louisiana parishes.

Source: National Archives & Records Administration

As noted, some sources claim Lincoln excluded those thirteen parishes because they were Union-held and thus beyond the Proclamation’s stated intent of freeing the enslaved only in “the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion.”

“This day” meaning January 1, 1863, the day the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect.

Here a problem arises: on that date those thirteen parishes were not entirely Union-held.

While Orleans Parish (including the city of New Orleans) and other parishes along the Mississippi River were wholly or largely Union-held, others of those thirteen parishes were not Union-held. Take, for example, St. Martin and St. Mary parishes.(3) At the time of the Proclamation’s enactment, neither St. Martin Parish nor the majority of St. Mary Parish were Union-held,(4) despite the ability of Union gunboats to ascend their meandering rivers and bayous.

Map of the exempted parishes,

Map of the exempted parishes,by the author.

When in the middle of that very month, for instance, a Union flotilla dared to steam up Bayou Teche — a vital 125-mile waterway of both strategic and economic importance — it encountered a withering barrage of enemy fire hailing from sharpshooters on land and a Rebel gunboat on water. Both sides suffered losses (among them the flotilla’s commander), but it was the Union that withdrew, leaving Rebels in command of the entire Teche.(5)

Again, why did Lincoln exclude those thirteen parishes from the Emancipation Proclamation when some were demonstrably not Union-held?

Two present-day historians, Stephanie McCurry of Columbia University and Martin Ruef of Duke University independently put forth the idea that Lincoln excluded those parishes because he (correctly or not) believed them to be bastions of pro-Union sentiment.(6) In other words, Lincoln did not wish to spoil the goodwill he thought existed in that alleged pro-Union enclave.(7)

Granted, the two historians do not overtly state why Lincoln excluded those parishes. They do strongly imply he did so because he viewed them as pro-Union. McCurry, for example, observes, “Nor did the Emancipation Proclamation resolve the dilemma [of enslavement], because the southern Louisiana parishes, with their cohort of Unionist sugar planters, were officially exempt from its provisions” [my italics].

Regardless, McCurry and Ruef confirm my interpretation of their writings. To my query McCurry responded, “[Y]our reading accords with my own,” while Ruef likewise replied, “[M]y understanding certainly dovetails with yours. In the book [his Between Slavery and Capitalism], I suggest that the exclusion resulted from efforts by Union authorities to maintain the support of sugar plantation owners.”(8)

Another present-day historian, John C. Rodrigue, formerly of Louisiana State University, now of Stonehill College, offers a similar if slightly qualified view of Lincoln’s motivation. As Rodrigue states in his Reconstruction in the Cane Fields, “[T]he proclamation specifically exempted from its provisions the sugar parishes. . . . [I]n addition to Lincoln’s refusal, on grounds of constitutional scruples, to attack slavery in areas not in rebellion, he also hoped to win the support of loyal slaveholders for a Unionist government for Louisiana” [my italics].

Like McCurry and Ruef, Rodrigue further explained his outlook in correspondence with me. In that exchange, he noted

I’m not sure I would go so far as to say that Lincoln excluded those areas because they were “pro-Union,” or even because he thought they were pro-Union [my italics]. I think it would be more accurate to say that [there] were some slaveholders (and other whites) who were loyal [to the Union], or there were slaveholders in those parishes who had previously supported the Confederacy but who were now willing to resume their allegiance [to the North] if doing so would help them to keep their slaves. . . . But in terms of the political loyalties of the majority of the white populations, these were not pro-Union areas. . . . Again . . . I would not necessarily concur in the statement that the excluded areas were “pro-Union” in their sentiment. But they did have potential Unionist elements that Lincoln was hoping to build on.

In other words, Rodrigue avers that Lincoln excluded those thirteen south Louisiana parishes not because he viewed them as significantly “pro-Union,” but because they harbored a population of sugar-planter slaveowners whom the President viewed as “potential Unionist elements.”(9)

Notably, those thirteen excluded parishes made up the entirety of Louisiana’s first and second U.S. Congressional districts, which — despite the ongoing conflict — sent two congressmen to Washington in early December 1862. That Lincoln should one month later exclude those parishes, and only those parishes, from the Emancipation Proclamation hardly seems coincidental. As one of those congressmen shortly observed, “[I]n the first and second congressional districts . . . those people have always in every election, and under the most trying circumstances, shown their fidelity to this [U.S.] Government.” Lincoln, in short, had no wish to derail pro-Union sentiment in two south Louisiana congressional districts still active in the U.S. political system, even as the rest of the state deferred to the Confederacy.(10)

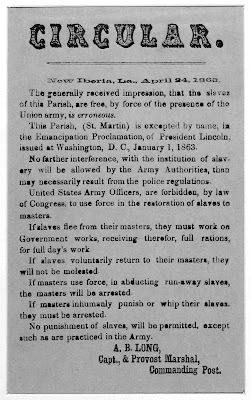

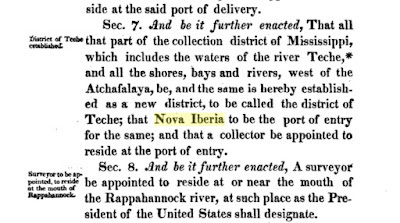

Whatever its impetus, the exclusion clause in the Emancipation Proclamation had real consequences. This is demonstrated by a circular printed by Union troops on capturing the town of New Iberia (located at the time, April 1863, in St. Martin Parish). Preserved in the Library of Congress, that circular declared, “The generally received impression, that the slaves of this Parish, are free, by force of the presence of the Union army is erroneous [original italics].” It continued, “This Parish . . . is excepted by name, in the Emancipation Proclamation, of President Lincoln, issued at Washington, D.C., January 1, 1863. . . . No farther [sic] interference, with the institution of slavery will be allowed by the Army Authorities, than may necessarily result from the police regulations.”(11)

Union circular stating that enslaved persons

Union circular stating that enslaved personsin occupied St. Martin Parish were not free.

Source: Library of Congress

Putting aside the Proclamation, the question remains, “When did slavery in Louisiana end in actuality, including in those thirteen excluded parishes?”

A reasonable answer might be that it ended months after the Civil War’s conclusion, when on December 6, 1865, the various states ratified the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. That amendment stated, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

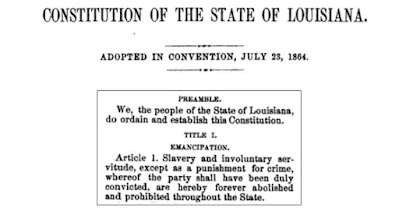

Yet the Union-held part of Louisiana had already abolished slavery as early as September 5, 1864.(12) On that date the state’s Union-controlled parishes ratified a new state constitution, the first article of which declared, “Slavery and involuntary servitude . . . are hereby forever abolished and prohibited throughout the state.”(13)

Detail of the 1864 Louisiana state constitution

Detail of the 1864 Louisiana state constitutionabolishing slavery (ratified September 1864).

Like the Emancipation Proclamation, this article was unenforceable in most of Louisiana, where the Confederate government remained in control. But with the South’s defeat in April 1865, the entire state fell under the rule of this new constitution and its vital antislavery article.

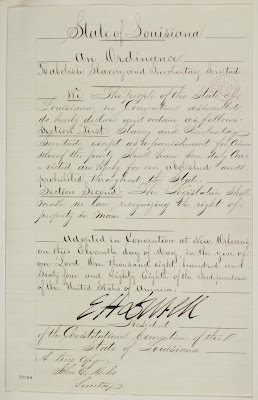

One could argue, however, that the Union-backed state government ended slavery even earlier than September 1864. On May 11 that year, the same state government issued an ordinance outlawing slavery within its borders.(14) Like the state constitution ratified months later, this May ordinance was unenforceable throughout most of Louisiana.

Louisiana ordinance

Louisiana ordinanceabolishing slavery (May 1864)

Source: Library of Congress

A mere ordinance might be said to lack the gravitas of a law framed in a state constitution. Yet an ordinance offered a notable benefit over a constitution and its complicated ratification process. As an abolitionist wrote of Louisiana’s new antislavery ordinance, “This important act, passed almost unanimously by the only legislative power in the State, does not need the ratification of the people to make it law. . . . [I]t no more stands in need of popular ratification than any other ordinance. . . . [W]ithout waiting for that endorsement, it is the law.”(15) In other words, the ordinance served as a feasible stop-gap measure pending ratification of the new antislavery state constitution.

This attempt to answer the broad question “When did slavery end in Louisiana?” demonstrates how messy history can be — even when dealing with a major well-documented event that occurred only 160 years ago.

To summarize, we might consider several possible dates for the end of slavery in Louisiana:

• January 1, 1863: when the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect (covering only Rebel-held parts of Louisiana);

• May 11, 1864: when the Union-backed Louisiana state government issued an ordinance banning slavery statewide (including both Union-held and, if symbolically, Rebel-held territory);

• September 5, 1864: when voters in Union-controlled parts of Louisiana ratified a new antislavery state constitution (effective in Union-held and, if symbolically, Rebel-held territory);

• December 6, 1865: when the various states ratified the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, banning slavery nationally.

As to the question of when slavery ended in those thirteen parishes excluded by the Emancipation Proclamation: it could be asserted the ordinance of May 1864 ended slavery in those places, either in theory or practice, depending on whether Union or Confederate forces locally held sway. Some four months later the newly ratified state constitution affirmed that ordinance. Moreover, that constitution became statewide law when the war ended in spring 1865. Finally, ratification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on December 6, 1865, declared on the federal level — and thus more commandingly — what Louisiana had already decided two summers earlier: that slavery was at long last a defunct institution.

NOTES

*I thank historian Daniel H. Usner of Vanderbilt University, independent geographer Lucy W. Osborn, and educator Tom Richey for critiquing my essay. I also express gratitude to Stephanie McCurry of Columbia University, Martin Ruef of Duke University, and John C. Rodrigue of Stonehill College for their substantive feedback on Lincoln’s reasons for excluding certain parishes from the Emancipation Proclamation.

(1) For example, enslaved persons could be seized if they had been used for “aiding, abetting, or promoting . . . insurrection or resistance to the laws” or when they had belonged to persons who “commit the crime of treason against the United States, and shall be adjudged guilty thereof. . . .”

(2) Allen C. Guelzo, Lincoln’s Emancipation: The End of Slavery in America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004), pp. 257, 258.

(3) I do not refer to Iberia Parish, which sits between St. Martin and St. Mary, because it did not exist in 1863.

(4) A Congressional document published in early February 1863 referred to the thirteen-parish region as “entirely within the federal lines [original italics], with the exception of the parish of St. Martin and a portion of St. Mary" [my italics]. Even then, the word “entirely” might have been an exaggeration. “Report No. 22,” House of Representatives, 37th Cong., 3rd Sess., 3 February 1863, in Reports of Committees of the House of Representatives and Court of Claims . . . 1862-’63 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1863), p. 1.

(5) Shane K. Bernard, Teche: A History of Louisiana’s Most Famous Bayou (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2016), pp. 81-83.

(6) As for the issue of why those parishes would have been pro-Union: their loyalty might have stemmed from a reliance on protective federal tariffs as well as on northern industry for refining their sugar. South Louisiana sugar planters produced brown sugar (and molasses), but left the commodity to others, outside the South, to refine into granulated white sugar.

(7) General Banks’ northern troops did much to dispel this pro-Union goodwill during their three Teche Country invasions of 1863-1864, burning and looting extensively. This fact stems not only from Confederate propagandists, but more importantly from Union soldiers who witnessed such behavior and condemned it. See Bernard, Teche, pp. 93-94.

(8) Stephanie McCurry, Confederate Reckoning: Power and Politics in the Civil War South (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2012), p. 254; Martin Ruef, Between Slavery and Capitalism: The Legacy of Emancipation in the American South (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2014), p. 44. McCurry, to Shane K. Bernard, 25 and 26 June 2025, email correspondence; Ruef, to Shane K. Bernard, 25 June 2026, email correspondence. I thank Dr. Stephanie McCurry of Columbia University and Dr. Martin Ruef of Duke University for their feedback on this topic and for permitting me to quote their correspondence.

(9) John C. Rodrigue, Reconstruction in the Cane Fields: From Slavery to Free Labor in Louisiana’s Sugar Parishes, 1862-1880 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001), p. 38; Rodrigue, to Shane K. Bernard, 15 July 2025, email correspondence. I thank Dr. Rodrigue for his feedback and for permitting me to quote his correspondence.

(10) The First Congressional District of Louisiana consisted of Plaquemines and St. Bernard parishes, and part of Orleans Parish, including a section of the city of New Orleans. The Second Congressional District consisted of Jefferson, St. Charles, St. John, St. James, Ascension, Assumption, Lafourche, Terrebonne, St. Martin, and St. Mary parishes, as well as, again, part of Orleans Parish and a section of New Orleans. “Report No. 22,” p. 1. Congressman Michael Hahn, Second Congressional District, State of Louisiana, in “Louisiana Elections,” The Congressional Globe, 17 February 1863, p. 1030. See also “Report No. 22,” pp. 1-3. I am indebted to Dr. Rodrigue for suggesting a link between the parishes in the First and Second congressional districts and those excluded from the Emancipation Proclamation. Rodrigue, to Bernard, 15 July 2025.

(11) This did not prevent enslaved persons from seizing de facto freedom for themselves. In south Louisiana many fled sugar plantations to seek protection with sometimes ambivalent Union troops. A. B. Long, Captain and Provost Marshall, Commanding Post, [Union Army], New Iberia, La., 24 April 1863, PD [digitized image], Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2020770803/, accessed 27 June 2025.

(12) I originally viewed 23 July 1864, the date of the constitution’s passage by the Union-backed state legislature, as a vital emancipative date. Dr. Rodrigue reminded me, however, that the constitution would not have become law until voters ratified it on 5 September 1864. See “Cases of Contested Elections in Congress from 1834 to 1865, Inclusive,” comp. D. W. Bartlett, Misc. Doc. No. 57, 38th Cong., 2nd. Sess., in Miscellaneous Documents of the House of Representatives, 1864-’65, Vol. 1 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1865), p. 585.

(13) Title I. Emancipation, “Constitution of the State of Louisiana, Adopted in Convention, July 23, 1864,” in Louisiana Annual Reports (Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Louisiana, for the Year 1865), Vol. XVII, (New Orleans: Bloomfield & Steel, 1866), Appendix, p. i.

(14) Ordinance Abolishing Slavery in Louisiana, 11 May 1864, ALS [digitized image], in Abraham Lincoln Papers: Series 1, General Correspondence, 1833-1916: Louisiana Constitutional Convention, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., https://www.loc.gov/resource/mal.3298..., accessed 17 July 1863.

(15)“Is the Black Code Still in Force?” New Orleans Tribune, 21 July 1864, p. 1.

October 11, 2024

Banned in the Classroom: Notes on the Outlawing of French in Louisiana's Public Schools

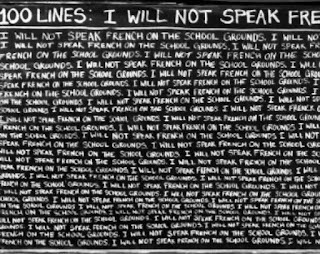

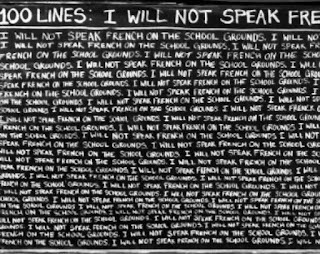

"I Will Not Speak French on the School Grounds,"

"I Will Not Speak French on the School Grounds,"from an exhibit at the Vermilionville

living history museum, Lafayette, La.

From approximately 1920 to 1960, educators routinely punished children in Louisiana's public school system for speaking French — often those students' primary if not sole language. As I wrote in my book The Cajuns: Americanization of a People (2003):

Some educators helped to bring about this change [i.e., Americanization] by punishing Cajun children who were caught speaking French at school. . . . Caught up in the Americanism of World War I and the following Red Scare sparked by the Russian Revolution, numerous states had designated English as the sole language of classroom instruction. Louisiana was among those states: in 1916 the state’s Board of Education banned French from classrooms, a move sanctioned by lawmakers in the state constitution of 1921.(1)

While many secondary sources refer to these two linguistic bans — the one of 1916 (about which more below) and the one of 1921 — I do not offhand know of any sources that actually quote the governmental primary sources in question. As a result, and for ease of reference, I compile the below primary-source references pertaining to the banning of French in the Louisiana public-school classroom — an event that opened the door to the punishment of Cajun children (and Creole children in general, I should add) for daring to speak their ancestral tongue on school grounds.

Some of the below information came to me from my mentor, Professor Carl A. Brasseaux, who I thank for sharing his knowledge of this topic.

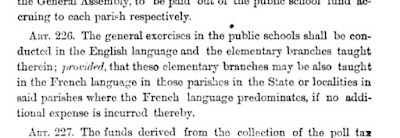

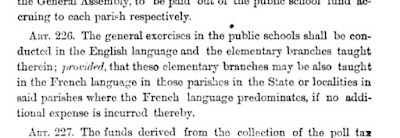

To the point — the Louisiana state constitution in effect in 1920 stated:"The general exercises in the public schools shall be conducted in the English language; provided, that the French language may be taught in those parishes or localities where the French language predominates, if no additional expense is incurred thereby."(2)

This clause had appeared in each of the state's constitutions since 1879, when it was first adopted, albeit with slightly different wording:

"The general exercises in the public schools shall be conducted in the English language and the elementary branches taught therein; provided, that these elementary branches may be also taught in the French language in those parishes in the State or localities where the French language predominates, if no additional expense is incurred thereby."(3)

From the 1879 state constitution.

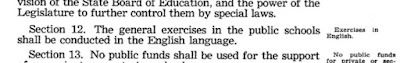

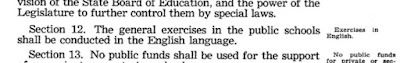

From the 1879 state constitution.In 1921, however, a new state constitution was ratified, which in regard to language in the classroom tersely read:

"The general exercises in the public schools shall be conducted in the English language."(4)

From the 1921 state constitution.

From the 1921 state constitution.In other words, from one year to the next — 1920 to 1921 — the French language became unacceptable for communication or instruction in Louisiana's public-school classrooms. (This ban did not affect the teaching of conversational French — explaining why, for instance, the Louisiana Department of Education issued a 24-page document in 1952 titled French Can Enrich Your Elementary School Program: A Progress Report on the Teaching of Conversational French in Several Louisiana School Systems. This may have been the case because students would have presumably mastered English by the time they reached high school, when schools offered conversational French as a topic of study. Another factor at work might have been a bias toward the "Parisian French" taught in conversational French, at the expense of Louisiana French, which many in the state unfortunately regarded as "bad French" or "not the real French.")(5)

This proscription, however, officially ended some fifty-three years later with ratification of the Louisiana state constitution of 1974. That document contained the following progressive article — one clearly influenced by the ethnic pride and empowerment movements of the 1960s and early '70s:

"The right of the people to preserve, foster, and promote their respective historic linguistic and cultural origins is recognized."(6)

❧

There is, however, serious need for reconsideration of a particular and rather common claim about this subject.

Despite frequent references by historians (including myself) and others to a 1916 ban on French in public-school classrooms — one allegedly enacted by the Louisiana state Board of Education five years before the overt "English-only" provision of the 1921 state constitution — I cannot locate any proof of such an order. An order that, in any event, would have been unconstitutional, because, as shown, the state constitution in effect in 1916 provided for French instruction "in those parishes or localities where the French language predominates."

However, I now believe there was no 1916 ban on French in public-school classrooms. Rather, I think claims to the contrary are based on a misreading or mischaracterization (albeit accidental) of the state directive in question.

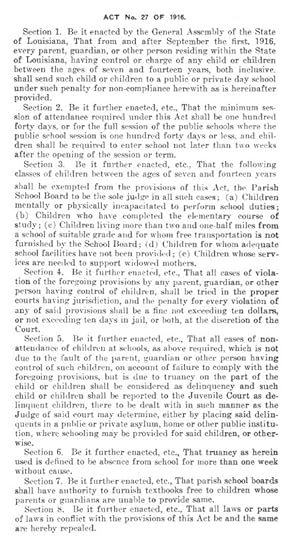

What actually occurred in 1916 was passage of compulsory education act, known generically as "Act No. 27 of 1916," sometimes retroactively called "the Mandatory Education Act." (See the image of the entire act located at the very bottom of this essay.)

Granted, this act — by levying penalties on parents and guardians who failed to send children to school — no doubt contributed indirectly to the punishment of French-speaking children, namely, by coaxing more French-speaking children into schools where they might be disciplined for speaking French. Yet it should be noted that the legislative act in question contained no mention of language — neither of the need for English to predominate in the classroom, nor the need to ban French.

In light of this finding — a new one for me, at least — I would no longer (to quote two sources chosen almost at random) characterize Act No. 27 as "the 1916 banning of French in Louisiana schools" nor claim that "In 1916, the state's board of education imposed a ban on French-language instruction."(7)

This was simply not the case.

I do not blame researchers who repeated this inaccuracy. Indeed, I myself am guilty of doing so — having heard the claim so many times from seemingly authoritative sources. Again, as I wrote in my book The Cajuns: Americanization of a People, "in 1916 the state's Board of Education banned French from classrooms. . . ."(8)But that I now know is incorrect.

What really happened in 1916 was not the banning of French, but rather the banning of truancy. Act No. 27, that is, stated (to seize on what is arguably the act's most essential passage):

And while the act goes on for several more paragraphs, it makes no mention of language, only mandatory school attendance.Some secondary sources, however, seem to have grasped the actual intent of Act No. 27. While still connecting this legislation to the punishment of French-speaking students, they more accurately characterize the act as only indirectly leading to punishment — particularly after ratification of the 1921 state constitution and its overt declaration that "The general exercises in the public schools shall be conducted in the English language." Even so, education officials and others complained that Act No. 27 of 1916, despite its apparent toughness on truancy, had no real teeth to it. And so, as I note in The Cajuns:

Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the State of Louisiana, That from and after September the first, 1916, every parent, guarding, or other person residing within the State of Louisiana, having control or charge of any child or children between the ages of seven and fourteen years, both inclusive, shall send such child or children to a public or private day school under such penalty for non-compliance herewith as is hereinafter provided. (9)

This larger [post-World War II] student population resulted not only from the period’s "baby boom," but from a tougher state compulsory attendance law, known as Act 239. Passed by the state legislature in 1944, it required all children between ages seven and fifteen to attend school regularly; it also provided for the punishment of parents who failed to comply. In addition, Louisiana created "visiting teachers," whose jobs combined the roles of truant officers and social workers.(10)I assert this 1944 mandatory education act ushered a "second wave" of French-speaking students into what were by then staunchly English-only schools. And, as I further contend, educators punished and denigrated this "flood of new students" for "their use of French, even as a second language because it allegedly corrupted their mastery of English." (Again, this ban did not affect the learning of conversational French.) Cajun children, and French or Creole-speaking children in general, were thus punished not merely in the years immediately following ratification of the 1921 state constitution, but into the 1940s and '50s — until by around 1960, as I observe, "youths had no reason to fear punishment at school for speaking French — because so few of them spoke French."(11)❧

For more on the topic of French and Creole (aka Kreyòl or Kouri-Vini) in Louisiana, see these other blog articles of mine:

French and Creole in Louisiana, 2010-2022: A Very Brief Analysis

Tracking the Decline of Cajun French

NOTES

(1)Shane K. Bernard, The Cajuns: Americanization of a People (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2003), p. 18.

(2)Article 226, Public Education, in Constitution of the State of Louisiana Adopted in Convention, at the City of New Orleans, the Twenty-Third Day of July, A.D. 1879 (New Orleans: Jas. H. Cosgrove, 1879), p. 55

(3)Article 251, in Constitution and Statutes of Louisiana . . . to January 1920, Vol. III, comp. Solomon Wolff (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1920), p. 2320.

(4)Article XII, Public Education, Section 12, in Constitution of the State of Louisiana Adopted in Convention at the City of Baton Rouge, June 18, 1921 (Baton Rouge: Ramirez-Jones Printing Company, [1921]), p. 93.

(5)Mabel Collette and Thomas R. Landry, French Can Enrich Your Elementary School Program: A Progress Report on the Teaching of Conversational French in Several Louisiana School Systems (Louisiana Department of Education, Division of Elementary and Secondary Education, 1952).

(6)Article XII: General Provisions, in Louisiana Constitution [1974 state constitution with amendments to 2024], Justia.com, https://law.justia.com/consti.../louisiana/Article12.html..., accessed 9 October 2024.

(7)Holly Duchmann, "French Language, Culture Alive but Struggling," HoumaToday, 12 April 2017, https://www.houmatoday.com/story/life..., accessed 13 October 2024; Ryan André Brasseaux, French North America in the Shadows of Conquest (New York: Routledge, 2021), p. 158, n. 92.

(8)Bernard, The Cajuns, p. 18.

(9)"Act No. 27 of 1916," Public School Laws of Louisiana, Tenth Compilation, T. H. Harris, State Superintendent (Baton Rouge: Ramires-Jones, 1916), pp. 109-110.

(10)Bernard, The Cajuns, p. 33.

(11)Ibid., p. 83.

Below, the entire text of Act No. 27 of 1916:

Banned in the Classroom: A Brief Note on the Outlawing of French in Louisiana's Public Schools

"I Will Not Speak French on the School Grounds,"

"I Will Not Speak French on the School Grounds,"from an exhibit at the Vermilionville

living history museum, Lafayette, La.

From approximately 1920 to 1960, educators routinely punished children in Louisiana's public school system for speaking French — often their primary if not sole language — on school grounds. As I write in my book The Cajuns: Americanization of a People (2003):

Some educators helped to bring about this change [Americanization] by punishing Cajun children who were caught speaking French at school. . . . Caught up in the Americanism of World War I and the following Red Scare sparked by the Russian Revolution, numerous states had designated English as the sole language of classroom instruction. Louisiana was among those states: in 1916 the state’s Board of Education banned French from classrooms, a move sanctioned by lawmakers in the state constitution of 1921.(1)

While many secondary sources refer to these two linguistic bans, I do not know of any that actually quote the governmental primary sources in question. As a result, I compile the below primary-source references pertaining to the banning of French in the Louisiana public-school classroom — an event that opened the door to the punishment of Cajun children (and Creole children, too, I should add) for daring to speak their ancestral tongues on school grounds.

Some of the below information came to me from my mentor, Professor Carl A. Brasseaux (retired), who I thank for sharing his knowledge on this topic.

To the point — the Louisiana state constitution in effect in 1920 stated:"The general exercises in the public schools shall be conducted in the English language; provided, that the French language may be taught in those parishes or localities where the French language predominates, if no additional expense is incurred thereby."(2)

This article had appeared in the state's various constitutions since 1879, when it was first adopted, albeit with slightly different wording:

"The general exercises in the public schools shall be conducted in the English language and the elementary branches taught therein; provided, that these elementary branches may be also taught in the French language in those parishes in the State or localities where the French language predominates, if no additional expense is incurred thereby."(3)

From the 1879 state constitution.

From the 1879 state constitution.In 1921, however, a new state constitution was ratified, which in regard to language in the classroom read:

"The general exercises in the public schools shall be conducted in the English language."(4)

From the 1921 state constitution.

From the 1921 state constitution.In other words, from one year to the next — 1920 to 1921 — the French language became unacceptable for communication or instruction in Louisiana's public-school classrooms. (This ban did not affect the teaching of conversational French — explaining why, for instance, in 1952 the Louisiana Department of Education issued a 24-page document titled French Can Enrich Your Elementary School Program: A Progress Report on the Teaching of Conversational French in Several Louisiana School Systems.)(5)

This proscription, however, officially ended with ratification of the Louisiana state constitution of 1974, which contained this article:

"The right of the people to preserve, foster, and promote their respective historic linguistic and cultural origins is recognized."(6)

A caveat: Despite frequent reference by historians and others to the state Board of Education banning English from public classrooms in 1916 — five years before such a ban appeared in the new state constitution — I cannot locate any proof of such a declaration (which, in any event, would have been unconstitutional because, as shown, the state constitution at the time provided for French instruction "in those parishes or localities where the French language predominates." I continue to look for this 1916 directive, if it even exists.

NOTES

(1)Shane K. Bernard, The Cajuns: Americanization of a People (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2003), p. 18.

(2)Article 226, Public Education, in Constitution of the State of Louisiana Adopted in Convention, at the City of New Orleans, the Twenty-Third Day of July, A.D. 1879 (New Orleans: Jas. H. Cosgrove, 1879), p. 55

(3)Article 251, in Constitution and Statutes of Louisiana . . . to January 1920, Vol. III, comp. Solomon Wolff (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1920), p. 2320.

(4)Article XII, Public Education, Section 12, in Constitution of the State of Louisiana Adopted in Convention at the City of Baton Rouge, June 18, 1921 (Baton Rouge: Ramirez-Jones Printing Company, [1921]), p. 93.

(5)Mabel Collette and Thomas R. Landry, French Can Enrich Your Elementary School Program: A Progress Report on the Teaching of Conversational French in Several Louisiana School Systems (Louisiana Department of Education, Division of Elementary and Secondary Education, 1952).

(6)Article XII: General Provisions, in Louisiana Constitution [1974 state constitution with amendments to 2024], Justia.com, https://law.justia.com/consti.../louisiana/Article12.html..., accessed 9 October 2024.

July 30, 2024

French and Creole in Louisiana, 2010-2022: A Very Brief Analysis

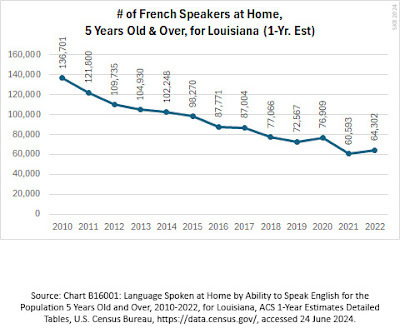

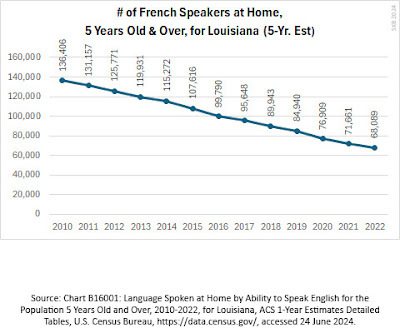

On viewing these charts one feature becomes immediately clear : a general decline in the number of Louisiana’s French and Creole speakers.

Discussing this with others who share my interest in all things Cajun and Creole, the consensus, though speculative, is that the decline stems largely if not solely from the demise of older French- or Creole-speaking persons, combined with an insufficient number of younger French- or Creole-speakers to replace them.

This downward trend — perceptible today even through impressionistic data (such as the dearth of French or Creole heard on the street, in commerce, or in other workday contexts) — explains the fervent “call to arms” among Louisiana’s sizeable corps of language and cultural activists.

Clearly there is no time to lose, yet, as esteemed folklorist and linguist Barry Jean Ancelet has often pointed out, “Chaque fois que l’on s’apprête à fermer le cercueil sur le cadavre de la culture cadienne et créole, il se lève et commande une bière!” Or, in translation, “Every time we prepare to close the coffin on Cajun and Creole culture, the corpse gets up and orders a beer!”(1)

It should be kept in mind that the stats in question are estimates derived from sampling and not the result of direct inquiry of all possible census respondents statewide. Moreover, while it is fact that the U.S. Census Bureau reports the results shown on the following charts (assuming, of course, I report the data accurately, and I think I do), readers with a healthy measure of skepticism might rightly ask, “Does this census data actually reflect the reality of language use in Louisiana?” That, however, is a topic for another day.

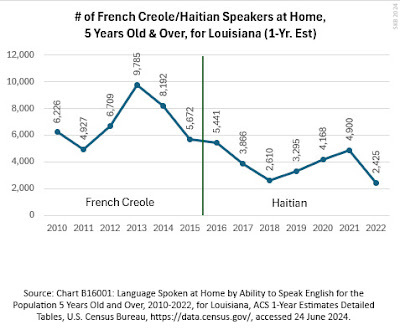

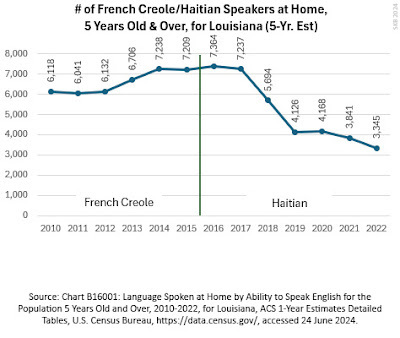

A note about the terms "French Creole" and "Haitian" as used by the U.S. Census Bureau: from 2010 to 2015 the Bureau collected language data on “French Creole.” From 2016 onward, however, it apparently ceased to collect data on that language or dialect, and instead began to collect data on what it referred to as “Haitian.” (A vertical red line on the "French Creole/Haitian" charts indicates where in time this change occurred.)

It is unclear if, in Louisiana’s case, the Census Bureau regarded “Haitian” as merely “French Creole” by another name. There does, however, appear to be some continuity in the numbers reported before and after the change in terms. It is therefore possible that census respondents considered “Haitian” a reasonable substitute for “French Creole,” especially given historic links between Louisiana and the people and culture of Haiti. I refer to large numbers of Haitians, both free and enslaved, who came to Louisiana in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

I leave it to others to determine why the Census Bureau made this switch and if, in the context of these ACS results, it is valid to interpret “Haitian” as synonymous with (or at least a close approximation of) “French Creole.” Regardless, “French Creole” is now viewed as a misnomer because it implies a dialect of continental French: rather, the tongue is now viewed as its own distinct standalone language called Creole, Kreyòl, or Kouri-Vini.

Finally, each language, French and Creole, is represented by two charts: one chart is based a one-year estimate and the other is based on a five-year estimate. As the Census Bureau explains:

Each year, the U.S. Census Bureau publishes American Community Survey (ACS) 1-year estimates for geographic areas with populations of 65,000 or more. . . . For geographic areas with smaller populations, the ACS samples too few housing units to provide reliable single-year estimates. For these areas, several years of data are pooled together to create more precise multiyear estimates. Since 2010, the ACS has published 5-year data (beginning with 2005–2009 estimates) for all geographic areas down to the census tract and block group levels. . . . This means that there are two sets of numbers — both 1-year estimates and 5-year estimates — available for geographic areas with at least 65,000 people. . . [while] Less populous areas . . . receive only 5-year estimates. . . . There are no hard-and-fast rules for choosing between 1-year and 5-year data.(2)

Notes

(1)Ancelet is quoted in Jean-Benoît Nadeau, “Mardi gras en Louisiane,” Le Devoir (Montreal), 24 February 2020, https://www.ledevoir.com/opinion/chro..., accessed 30 July 2024.

(2)“Understanding and Using ACS Single-Year And Multiyear Estimates,” U.S. Census Bureau, 2018 [PDF document (excerpt)], https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Ce..., accessed 30 July 2024.

June 20, 2024

Disappearing Cajuns and Creoles? Ethnic Identity and the Limits of Census Data

“Historians and math

“Historians and math do not always go well together”

WhileI never excelled at math (an understatement), I nonetheless use quantitativeanalysis, albeit sparingly, in my books. I did so perhaps most notably in TheCajuns: Americanization of a People, which I sprinkled lightly with numericaldata gleaned from U.S. censuses, including, but not limited to, the most recentone, the 1990 Census. (I wrote in the late 1990s, before the 2000 U.S. Censushad been compiled.)(2)

My 2023 book The Cajuns:

Americanization of a People

Althoughonly about a quarter-century ago, I wrote The Cajuns at a time when censusdata was not, unlike today, readily available on the Internet — at least not inany detail. Researchers instead had to visit a brick-and-mortar library andconsult multi-volume censuses printed on actual paper as well as inother forms of media. Moreover, finding sought-after data could be extremelydifficult because, as one library notes, “the 1990 census filled hundreds ofvolumes, CDs and numerous tape files. . . .”(3) Even then, the required data might not actually exist in any ofthose published sources.

Inthat case, there was an alternate source of census data: the Public Use MicrodataSample (PUMS), a digital database of raw census data based on a 1-percent,3-percent, or (as I myself used) 5-percent sample of respondents in specificgeographic regions. This is important, because while the short-form 1990 U.S. Census — the version sent to most American households — askedrecipients how they identified racially (Black, White, Hispanic, and so on), itdid not ask how they identified ethnically (Italian, Jamaican, Filipino,Dutch, Norwegian, or any number of other ethnicities). However, the long-form 1990U.S. Census — received by 5 percent of U.S. households and gathering the actual PUMS data — did askrespondents to identify their ethnic ancestries. Using complicated formulas, theU.S. Census Bureau could then extrapolate from that sample to provide ancestral data aboutall U.S. households.

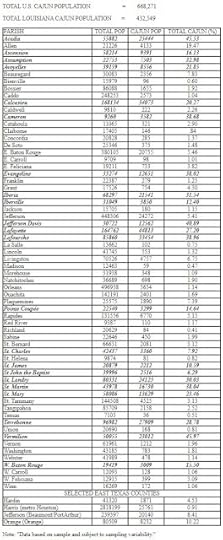

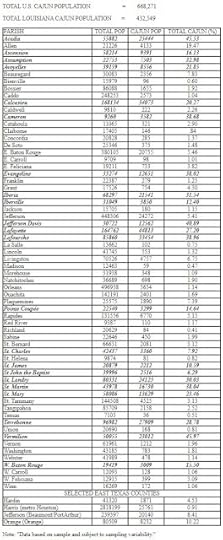

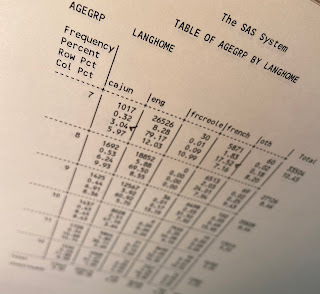

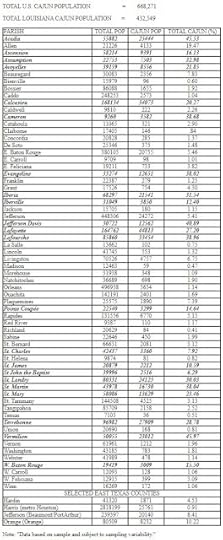

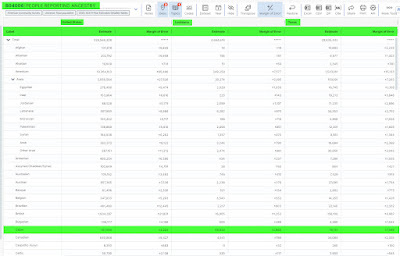

Figure 1: 1990 PUMS data, for Cajuns,

by Louisiana parishes and select Texas counties,

Acadiana parishes in bold,

(click to enlarge).

Image source: author's defunct website.

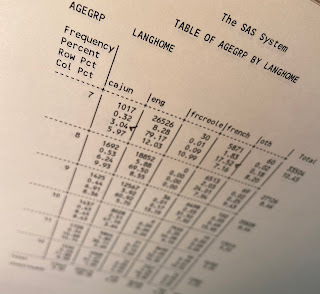

PUMSdata, however, was hardly perfect. Besides the fact it could never provide morethan an estimate (one would hope an accurate estimate),the general public often could not access PUMS data, which required somewhat powerfulcomputers (for the time) loaded with the proper, and rather complicated, software. As such, PUMS data generally had to be accessed through aninstitution, such as a university. Moreover, it was not enough to accessthe PUMS database: rather, you also had to know, or know someone who knew, how toprogram the database to obtain the sought-after data. And because that outputappeared in a form hardly describable as “WYSIWYG” (“what you see is what youget” or, more plainly, in a self-explanatory format), you also had to know, orknow someone who knew, how to interpret that very user-unfriendly data printout.

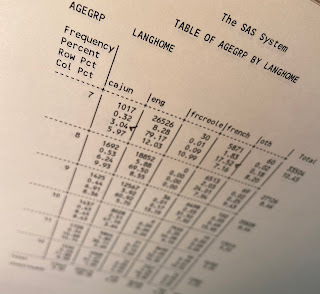

User-unfriendly PUMS data printout,

User-unfriendly PUMS data printout,1990 U.S. Census

Fortunately,I had access to PUMS data through the Sociology Department of Texas A&MUniversity, where I pursued my doctoral degree in History with a minor in RuralSociology of Minorities (very useful if, like me, you are studying the Cajunsand Creoles of rural and small-town south Louisiana). It was my Sociologyprofessor, Dr. Rogelio Saenz, who taught me about PUMS data and helped me to obtain and interpret the PUMS data I sought.

For example, I might have asked the PUMS database to report howmany Louisianians in 1990 identified their ancestry as primarily Cajun or Acadian (the latter of whichI interpreted to mean “Cajun”)* and of those how many spoke French as theirfirst language in the home; or of those how many identified as World War IIveterans; or even of those how many spoke French in the home and also identifiedas World War II veterans. To continue with this example, I was then able to extrapolatebackward and estimate the total number of Louisianians of Cajun ancestry who fought in World War II and how many of those “Cajun GIs” spoke French inwartime.(4) (A note: I did not compile 1990 PUMS data about Creoles,though that raw data did exist in the PUMS database. I chose not to do sobecause, while my dissertation topic originally focused on Cajuns andCreoles, I found it necessary to winnow my focus solely to Cajuns — otherwise Ibelieved the scope of my dissertation would have been too unwieldly. A fragment of my early research focusing on both Cajuns and Creoles can be found here.)

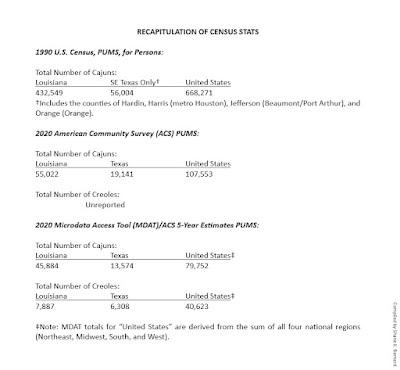

Intriguingly,the 1990 PUMS data revealed that there were 432,549 persons in Louisiana whoself-identified as primarily Cajun compared to 668,271 such persons in theentire U.S. (see Figure 1). Many of those out-of-state Cajuns no doubt emigrated fromLouisiana in the wake of the recent “oil glut” that shattered the state’soil-dependent economy in the mid- to late 1980s.(5)

ThisPUMS data also identified a number of quirks among the assumed Cajunpopulation. For example, it revealed that 10 percent of all Louisianians consideredthemselves as primarily Cajun. And while as mentioned 432,549 persons in Louisiana listed their primary ancestry as Cajun, another 25,000 listedtheir secondary ancestry as Cajun. Vermilion Parish, in south-central Louisiana,possessed the largest percentage of persons identifying primarily as Cajun, about 50percent. Also, the census suggested that most Cajun respondents had not strayedfar from their ancestral south Louisiana homeland: of the 668,271 persons throughout the U.S. identifying as primarily Cajun, 77 percent resided in Louisiana orneighboring Texas.(6)

Moreover,few persons in New Orleans considered themselves Cajun — despite the media andtourism industries painting New Orleans as a “Cajun” city, a claim thatappeared ad nauseum during the Cajun fad of the 1980s. Yet in 1990 only onepercent of respondents living in New Orleans proper (Orleans Parish) marked “Cajun” as their primary heritage. The percentage remained low (7 percent or less) in parishessurrounding New Orleans. Indeed, census data showed that New Orleans boasted about the same concentration of Cajuns as Houston. As I wrote in my book The Cajuns, “Houston, Texas, possessed nearly the same percentage of Cajuns as New Orleans — less than a quarter of a percent difference — and on a per capita basis Houston actually boasted 4.5 times as many Cajuns.” And yet, unlike New Orleans, the media and the tourism industries did not portray Houston as “the center of the Cajun universe.”(7)

❧

Overthe past twenty-five years since I did my PUMS research, the Internet has grownexponentially, along with the amount of useful (and not so useful) data it offersto scholars and laypersons alike. In fact, the U.S. Census Bureau’s website nowaffords the general public access to extremely detailed census results indigital format — meaning there is arguably no longer a need to navigate countlesshardcopy volumes to locate sought-after data. With a few clicks of a mouse,that information can now be accessed 24/7 using any computer (as well as digitaltablets and cell phones) linked to the Internet.

Thetask, however, still requires a degree of skill and patience because the requireddata might not at once be discernable. As with the old PUMS database,researchers might still have to figure out how to configure the census.govinterface to reveal the desired data — and just how to do that is not necessarily self-evident. In addition, it’s easier than ever to become mired in the sheervolume of census data now available to everyone. (Fortunately, I havefound that Census Bureau experts promptly answer requests for help submitted by the public per email.)

Thisbeing said, it is interesting to compare current U.S. census stats for Cajuns with the1990 census stats I consulted a quarter century ago. Moreover, it’s possible toconjure up similar stats for the other group of interest to me, Creoles — by which I mean, unless otherwise stated, Creoles by any definition, and regardless of color. (In this essay I won’t wade into issues surrounding the word “Creole,” much less the assertion, which Iembrace, that “Cajuns are a type of Creole”; but my essays on these topics can befound here.)

Besidesconducting the usual decennial census, the U.S. Census Bureau now compilessomething called the American Community Survey (ACS). The Bureau describes theACS as “an ongoing survey that provides vital information on a yearly basisabout our nation and its people.” (You can read about the differences betweenthe decennial U.S. Census and the ACS here.)(8)And the ACS does count the number of respondents who identify as “Creole,” aswell as those who identify as “Cajun.” Accessing this sought-after data, however, is somewhatcomplicated: while population stats for Cajuns are fairly easy to find,those for Creoles are, unfortunately, buried a little deeper in the raw data.

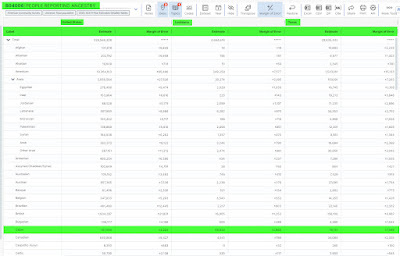

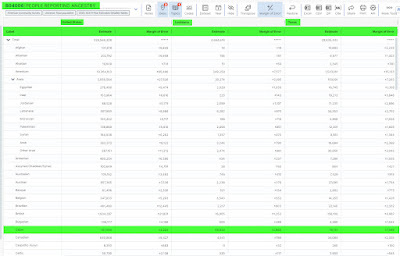

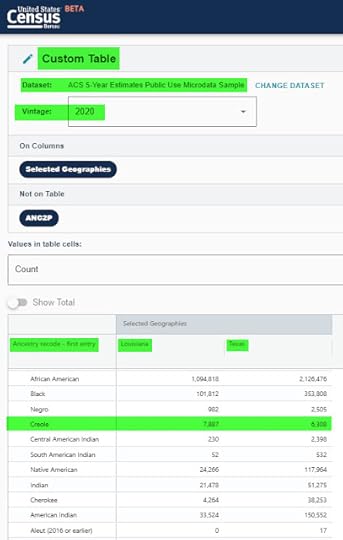

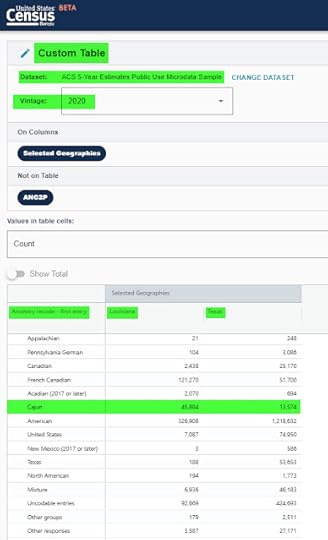

Accordingto one specific ACS table available on the U.S. Census Bureau website, namely,Table B04006, titled “People Reporting Ancestry” — accessible here, or see Figure 2 — 107,553 persons throughout the U.S. identified their primary ethnicity in2020 as “Cajun” (give or take about 4,222 persons according to the margin oferror — but I won’t list margins of error from here on out; you can find them onthe original charts). Of these, 55,022 lived in Louisiana, or 51.15 percent ofall Cajuns; while 19,141 lived in neighboring Texas, or 17.79 percent of allCajuns. (Note I am looking only at responses for primary ethnicity, not secondary,which I leave for others to explore.)(9)

Figure 2: Table B04006,

“People Reporting Ancestry,”

from the 2020 American Community Survey,

Cajun stats highlighted

(click to enlarge).

Alreadysomething odd is discernible: only 55,022 Cajuns exist in the entire stateof Louisiana? And those Cajuns comprise only 51 percent of the totalnumber of Cajun people in the entire U.S.? These stats seem way off. Butmore on this shortly.

Whatwe don’t find on Table B04006, however, is any reference to persons whoidentified as “Creole.” It seems the Census Bureau relegated those respondents to a catch-all “Other”category. As a result, Creoles went uncounted on this table as a standalone ethnic group.

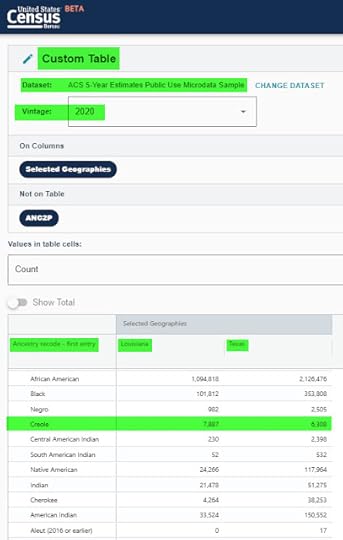

Thisdoes not mean the U.S. Census Bureau overlooked Creoles in 2020. In fact,self-described Creoles were counted, albeit on a different ACS table for2020: namely, a custom-generated table compiled using the Microdata AccessTool (MDAT), which drew its output from the ACS 5-Year Estimates PUMS dataset. The resultscan be accessed here, or see Figure 3.(10)

Accordingto this MDAT table, 7,887 persons in Louisiana identified their primaryethnicity in 2020 as “Creole,” while, for comparison, 6,308 persons in Texaslikewise identified their primary ethnicity as “Creole.” This reflects theemigration of south Louisiana Creoles to the Lone Star State, mainly itssoutheast region, over many generations going back well into the early to mid-20thcentury.

Again, however, these stats for Creoles, like those for Cajuns, seem incredibly off. Bywhich I mean “far too small.”

Figure 3: MDAT table for Creoles,

Louisiana and Texas, 2020,

Creole stats highlighted

(click to enlarge).

Otherconundrums also present themselves. Why, for example, are there so many fewer “Creoles”than “Cajuns”? If anything, I would expect more Creoles thanCajuns, not the other way around.

In my opinion these issues reveal the limitations of self-reported ethnic andracial data. A major issue, for example, is that a person of Creoleancestry might correctly identify as “Creole,” but just as correctly identifyas “African American” or “Afro American” or “Black” or “Afro” or “Negro” (all labelsrepresented on the MDAT table). They might also identify as members of thoseannoyingly generic, ill-defined, and I would assert almost meaningless “ethnicities,”namely “American” and “North American.” (Is “American” really an ethnicity or,as I would assert, a nationality?) They might also correctly identify as “Cajun”or “Acadian” or “French” or any number of other ethnicities they might claim. And this is considering only Creoles of African descent, not Creoles who identify as White and might correctly claim a variety of ancestries in their own right — thus further complicating the task of ethnic self-identification.

Theissue is the same for Cajuns. They might correctly identify as primarily “Cajun”or “Acadian” or “French” or “Canadian” or “French Canadian” or “Creole” (again,Cajuns can be viewed as a type of Creole) or “American” or “North American,”and so on.

Thismay explain why, whether we compare the 1990 census results to those in the2020 ACS Table, or the 2020 ACS table to the MDAT table for that same year, weend up with notable data discrepancies.

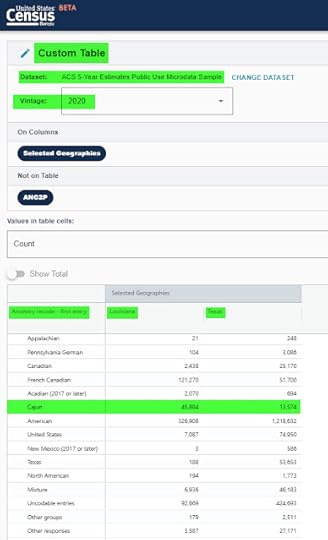

For example, the 2020 ACS table counted55,022 self-described Cajuns in Louisiana — but what happened to the other 377,527who identified as such in 1990? Similarly, according to the MDAT tablethere were 45,884 self-identified Cajuns in Louisiana in 2020 . . . about 9,000less than the 55,022 tallied for the same year on the separate ACStable (see Figure 4).(11)

Whythe difference between these two 2020 sources, both issued by the U.S. Census Bureau?

Figure 4: MDAT table for Cajuns,

Louisiana and Texas, 2020,

Cajun stats highlighted

(click to enlarge).

Asa demographic statistician at the Bureau kindly explained to me, “Forrelatively small groups there are sometimes differences in results depending onthe data set used. The microdata tool uses the American Community Survey (ACS)PUMS while Table B04006 uses the full ACS data set. This may be part of thereason why there would be a difference in a relatively small group such asCajun. Another reason is that 2020 was a difficult year for data collection dueto the [COVID] pandemic. The data from 2016-2020 for smaller groups may be lessreliable than normal.”(12)

Thisis, however, not the first time incongruities have been noticed by those whouse censuses to study south Louisiana. As I wrote in my Americanizationbook:

[R]esearchers have discovered a majordiscrepancy between the 1990 census and preliminary results from the 2000census. The 1990 census counted over 400,000 Cajuns in Louisiana, while the2000 census counted only about 40,000 — a roughly 90 percent decline in only tenyears! The U.S. Census Bureau clearly miscounted, either in 1990 or 2000 (orboth), for the disappearance of almost the entire Cajun population in only adecade is highly improbable. . . . Louisiana historian Carl A. Brasseaux . . .discounted the 2000 statistics, noting wryly that there are probably 40,000Cajuns on the north side of Lafayette Parish alone. Non-academics also havescoffed at the 2000 statistics. Lafayette’s Daily Advertiser [newspaper]ridiculed the figures as “cockeyed” and observed “Our government advises [us]that there aren’t as many Cajuns . . . as we saw dancing in the streets duringfestival time.” “If You’re One of 365,000 Missing Cajuns,” ran one of itsheadlines, “Please Send up a Flare.” Asked another newspaper, “Where Did Allthe Cajuns Go?”(13)

I in no way criticize the U.S. Census Bureau. In fact, Iwould now assert that such discrepancies in census data stem in part— perhaps in large part — from the fact that we are dealing (of course) with humanbeings; and human beings are innately subjective creatures.As such, they are not only difficult to pin down, but very much dislike being pinned down. As shown, the very multiplicity of correct answers a Cajun or Creole might give to an ancestry query is also problematic. Likewise, it is possible long-form census recipients chose, say, the first ethnic label that came to mind, rather than the ethnic label they themselves might have genuinely regarded as most suitable or accurate. Moreover, some, perhaps even many, recipients simply might not have answered the ancestry question, for whatever reason (confusion, impatience, privacy concerns, etc.).

Census data can be useful for indicating general demographic trends, but it can prove misleading if always taken at face value. (Again, only 7,887 Creoles in all of Louisiana in 2020? And only 55,022 Cajuns?) This, however, is where narrative history can complement census data, as well as complement more quantitative approaches to history in general. By drawing on traditional and — as I like to do — not-so-traditional sources, history as good old-fashioned storytelling can present fuller, more accurate, and I would argue more engaging views of the past. Conversely, quantitative data, when used in just the right, sparing amount, can complement traditional narrative history. And that quantitative data — wary as I am of math and my own math skills — has helped me to better understand the people called Cajuns and Creoles, and to convey that understanding to others.

Figure 5:

Figure 5: Recapitulation of statistics

used in this essay

(click to enlarge)

After writing theabove blog article about the limits of census data pertaining to Cajuns andCreoles, a couple of readers asked me to examine what the census results sayabout present-day language use in Louisiana. That is, how many persons in thestate today speak French as their primary language in the home? This is indeedpossible to gauge. But, as with census data concerning how many people identifyas Cajuns and Creoles, we should examine the language data with a degree of skepticism.My review of these numbers, by the way, is hardly exhaustive, and is meant toafford only a glimpse at recent language traits in Louisiana, and of only twoor three languages at that.

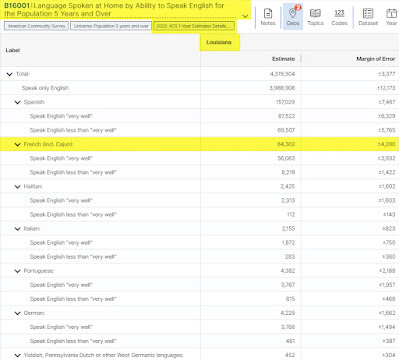

Let’s first go back afew years: in 2015 the U.S Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS)5-year estimate, accessible here, found 107,616 Louisianians speaking French “at home,” as wellas 7,209 who spoke French Creole (now widely regarded not as a dialect ofFrench, but as a distinct, standalone language called Creole, Kreyòlor Kouri-Vini). Unfortunately, later census results do not mentionFrench Creole by any name, though perhaps it might be found much deeper in theraw data. As for “French” in Louisiana, the U.S. Census Bureau regards thatlanguage as including more than one strain, including what it calls “Cajun” — despitethe fact that some linguists now assert Cajun French does not exist (a view Imyself do not embrace, but then, I am not a linguist).(14)

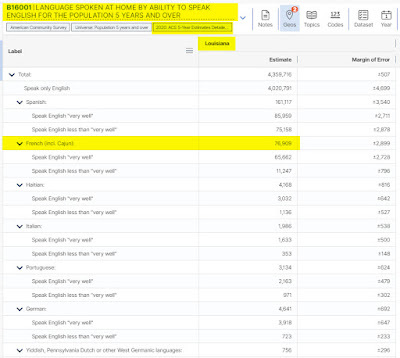

Figure 6: Table B16001,

“Language Spoken at Home. . . ,”

from the 2015 American Community Survey,

French and French Creole stats highlighted

(click to enlarge).

Seven years later the2022 ACS 1-year estimate (the most recent year for which data is presently available, accessible here)found the number of French speakers in Louisiana to be only 64,302 — a decline of40.24 percent since 2015. This trend might be explained by the dying out ofolder, primarily French-speaking Louisianians (and too few French-speakingyouths taking their places, despite the advent of French Immersion schools).Even so, other explanations might account in part for this precipitous decline.(15)

Figure 7: Table B16001,

“Language Spoken at Home. . . ,”

from the 2022 American Community Survey,

French and French Creole stats highlighted

(click to enlarge).

Out of curiosity, Iwent to the 2020 ACS 5-year estimate, accessible here, which recorded the number of Frenchspeakers in Louisiana that year as 76,909 — considerably less than the 2015figure of 107,616, but notably more than the 2022 figures of 64,302.(16) This2020 stat, however, is consistent with a downward trend.

Figure 8: Table B16001,

“Language Spoken at Home. . . ,”

from the 2020 American Community Survey,

French and French Creole stats highlighted

(click to enlarge).

It is interesting tocompare the number of present-day French speakers in Louisiana homes to that ofpresent-day Spanish speakers. As elsewhere in the U.S., Louisiana has in recentdecades experienced a significant rise in the number of Latino residents. (Fittingly,Louisiana belonged to the Spanish Empire from 1762 to 1800. It was thus aSpanish colony, at least on paper, when the Cajuns’ exiled Acadian ancestors beganto arrive in the colony in 1764. Moreover, in 1779 Spaniards founded the southLouisiana town where I live, New Iberia, as the village of Nueva Iberia.)