Shane K. Bernard's Blog, page 7

October 7, 2012

Sur la Teche: Exploring the Bayou by Canoe, Stage 1

My next book is a history of Bayou Teche (due to be finished next year). As research for this project I resolved to row the entire length of the bayou. I didn’t see how I could not row it. Had I not rowed it, someone, somewhere — at a book signing, during an interview — would inevitably ask, “Have you ever been on Bayou Teche?” to which I would have had to answer, “No — but I live two blocks from it. And I drive across it every day on the way to work.”

The rowers for stage one, at the Courtableau landing.

The rowers for stage one, at the Courtableau landing.

Back row: Jacques, Preston, and me; in front, Keith.

(Click images to enlarge them; photograph by author)

So I decided to explore the entire bayou, and to do so not by motorboat (which seemed like cheating), but the old-fashioned way, by canoe — all approximately one hundred thirty-five miles of it. It just seemed like the right thing to do. And this proved correct, because I found there is no substitute for seeing for oneself, from a boat, where Bayou Courtableau gives rise to the Teche, where Bayou Fuselier cuts over from the Teche toward the Vermilion, where the Teche zigzags at Baldwin and juts out at Irish Bend, running ever closer to its mouth (which actually no longer exists — I’ll explain later).

I would not row the entire bayou at once, however, but in stages over many months. I planned to row slowly, stopping to take photographs and to record GPS coordinates.

Preston and Jacques heading into the Teche from the Courtableau.

Preston and Jacques heading into the Teche from the Courtableau.

(Photograph by author)

I drafted two friends to assist me in the trek, both archaeology graduates from UL-Lafayette: Preston Guidry and Jacques Doucet. Preston’s father, Keith Guidry, made up a last-minute addition to the team; and while Preston and Jacques ended up sitting out several of the stages, Keith became a constant. Preston’s brother, Ben Guidry, filled in for Preston on a couple of stages. Forestry biologist and fellow historical researcher Don Arceneaux joined us for one stage. Together — an Arceneaux, a Doucet, three Guidrys, and a Bernard — we would seek an answer to the profound question, “How many Cajuns does it take to row Bayou Teche?”

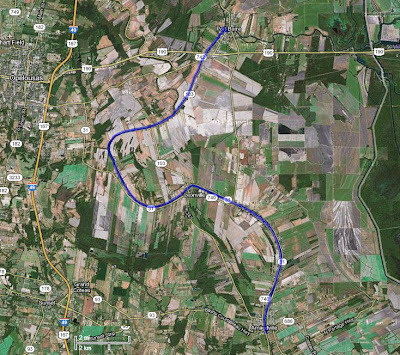

Aerial photograph of Stage 1, Port Barre to Arnaudville.

Aerial photograph of Stage 1, Port Barre to Arnaudville.

(Source: Google Maps)

We began around 9 am on October 23, 2011, by design a week after the annual Tour du Teche canoe race. (We didn’t want to get in the way of the racers, and so let them go first.) We put in at the public boat dock at Port Barre, on the Courtableau about three hundred yards east of the headwaters of the Teche. Within minutes we were rowing on the Teche itself, which is narrow there (varying from about 75 to 95 feet wide, not much larger than a sizable coulee), with dense tree canopies on either side reaching toward the opposite bank and pressing in toward our canoes.

On the Teche near its origin at Port Barre.

On the Teche near its origin at Port Barre.

(Photograph by author)

The current at Port Barre was fairly swift and strong for a bayou — they are usually noted for their slowness — and with our casual rowing it carried our two canoes down the bayou at a decent clip. This fooled us into thinking we would make similarly fast headway the entire length of the bayou; but farther down the current slowed considerably and, eventually, reversed — reducing our progress and making the rowing a more grueling effort. In fact, by the fourth or fifth stage it took us ten or twelve hours to accomplish what we originally did in half that time. But this lesson would not be learned for several more months, undertaking, as we did, a stage every month to month and a half.

The weather that day was cool and the sky mostly clear. Of the group I was the least experienced rower, but Preston, Jacques, and Keith, who rowed often — including in the challenging Atchafalaya swamp — made up for my greenness.

Grazing land along the Teche south of Port Barre.

Grazing land along the Teche south of Port Barre.

(Photograph by author)

Shortly after leaving Port Barre we spotted a coyote running parallel to the bayou on the east bank — the first sign of wildlife on our trip. We soon saw a number of large bones on the west bank, probably cattle. Right before that we had caught the strong scent of cattle dung and must have been passing a ranch (or vacherie, as our ancestors would have called it). At about 10:30 am Keith and I (who rode in the same canoe) stopped beside a bridge to wait for Preston and Jacques. As we floated there, someone up above threw a bottle from the window of a passing car: the bottle burst as it clipped the bridge railing and splashed in the water beside me, still in its anonymous paper bag. Keith found this amusing, and I joked someone had tried to kill me.

Shortly after Preston and Jacques caught up with us they spotted a water moccasin swimming in the bayou; surprisingly, it was the only snake we saw during the many stages of our trip.

An old car along the Teche.

An old car along the Teche.

(Photograph by author)

I noticed much less garbage on the bayou than expected, certainly a tribute to the efforts of Cajuns for Bayou Teche. This group sponsors the Tour du Teche race and uses funds generated from the event to clean up the bayou. The largest quantity of garbage I saw that day lay inside the city limits of Port Barre, where certain persons used the banks of the bayou as private trash heaps. Outside of town, however, the garbage became less frequent. Some it was clearly vintage, which gave it a certain respectability: no one wants to see a new clothes washing machine or recent-model car half-submerged in the bayou or half-buried in its rising banks; but a rusty Depression-era clothes washer or vintage 1950s coupe are more interesting and even somehow appealing in their antiquity.

Another old car along the Teche.

Another old car along the Teche.

(Photograph by author)

Only a few homes lined the Teche between Port Barre and the next bayouside community, Leonville. On the outskirts of Leonville, however, we saw a few suburban-style homes, which removed the illusion of being in wilderness. We reached Leonville at 11:45 am to the sounds of the church carillon. Just south of town, as we headed back into countryside, we spotted a nutria on the bank, scurrying to hide itself from us. Within the hour, just below the Oscar Rivette Bridge, we saw a large owl. Five minutes later we passed under high-voltage transmission lines, whose audible hum and static made me nervous to sit between them and a body of water.

Keith and me (in front) on the Teche.

Keith and me (in front) on the Teche.

(Photograph by Jacques Doucet)

We observed pecan pickers here and there just north of the next community on the bayou, Arnaudville, as well as a large bird I recorded as an “anhinga.” I’m no ornithologist, however, but it looked fairly large and sported dark plumage and black legs — possibly not an anhinga, but a little blue heron. We would see many herons or egrets on our stages, often a single large bird whose solitary hunting we interrupted repeatedly, spurring him farther and farther down the bayou in front of our boats.

View of the Teche from my canoe.

View of the Teche from my canoe.

(Photograph by author)

At 1:45 pm we arrived in Arnaudville, our terminus for this stage of the trip. We pulled ashore at Myron’s Maison de Manger (excellent burgers), right below the junction of the Teche and Bayou Fuselier.

On the other side of the Fuselier once stood the home of my colonial-era ancestor, Lyons-born planter Gabriel Fuselier de la Claire. It’s an extravagant name, but if he had been a big wheel in France I doubt he would have chosen to brave the south Louisiana frontier. With its heat, humidity, mosquitoes, alligators, pirates, and occasional slave or Indian revolts, the French and Spanish colony was no paradise, despite its idealized portrayals in literature. (See Longfellow’s Evangeline.)

Fuselier de la Claire prospered in Louisiana, however, as did his heirs — but somewhere down the line (probably during Reconstruction) the family lost its fortune and ended up marrying into my impoverished clan of subsistence-farming Cajuns. The same happened to the delaMorandieres, deLivaudaises, and other French Creole aristocrats who wound up in my family tree. After a generation or so nothing remained of them culturally, except for my grandmother’s memory that her elderly in-law, the last delaMorandiere of the line, “spoke that fancy French.”

My favorite photo from that day on the Teche, October 2011.

My favorite photo from that day on the Teche, October 2011.

(Photograph by author)

A folksy hand-painted sign hangs beside the bayou near the landing at Myron’s, erected by the local Sons of Confederate Veterans chapter (or “encampment,” as they call it). Erected solely for the benefit of boaters, the sign stated that several steamboats sank at that site during the Civil War.

Sign listing steamboats that sank on that spot during the Civil War.

Sign listing steamboats that sank on that spot during the Civil War.

(Photograph by author)

The Official Records of the conflict indicates that the five vessels had been scuttled by the Rebels to keep them from falling into enemy hands. As a Union officer wrote in April 1863:

Burning steamboats.

Burning steamboats.

(Source: Harper's Weekly [1869])

So who knows how many cannons, shot, belt buckles, bullets, and other Civil War artifacts lay in the mud at the bottom of the bayou, artifacts we paddled over unknowingly as our trip that day came to an end?

After 19 miles of rowing we all were exhausted, but I seemed by far in the worst shape. My arms hurt as though I'd been lifting barbells for too long, and my palms, covered with a metallic sheen from the oars, were sore with blisters. "Next time," I thought, "use gloves." By the time I reached home, I hurt all over: I don't exaggerate when I say I've never felt such excruciating pain in my arms, chest, and back. My bones themselves seemed to ache, right down to the marrow. No matter in what position I sat or lay, I could not make the discomfort go away. This was my penalty for undertaking the trip in poor shape. I swallowed some aspirin and slept horribly, but by morning the pain had disappeared except for vague aching in my upper arms. Fortunately, the pain did not return after future stages. I needed this first stage to break myself in.

The rowers for stage one, at the Courtableau landing.

The rowers for stage one, at the Courtableau landing.Back row: Jacques, Preston, and me; in front, Keith.

(Click images to enlarge them; photograph by author)

So I decided to explore the entire bayou, and to do so not by motorboat (which seemed like cheating), but the old-fashioned way, by canoe — all approximately one hundred thirty-five miles of it. It just seemed like the right thing to do. And this proved correct, because I found there is no substitute for seeing for oneself, from a boat, where Bayou Courtableau gives rise to the Teche, where Bayou Fuselier cuts over from the Teche toward the Vermilion, where the Teche zigzags at Baldwin and juts out at Irish Bend, running ever closer to its mouth (which actually no longer exists — I’ll explain later).

I would not row the entire bayou at once, however, but in stages over many months. I planned to row slowly, stopping to take photographs and to record GPS coordinates.

Preston and Jacques heading into the Teche from the Courtableau.

Preston and Jacques heading into the Teche from the Courtableau.(Photograph by author)

I drafted two friends to assist me in the trek, both archaeology graduates from UL-Lafayette: Preston Guidry and Jacques Doucet. Preston’s father, Keith Guidry, made up a last-minute addition to the team; and while Preston and Jacques ended up sitting out several of the stages, Keith became a constant. Preston’s brother, Ben Guidry, filled in for Preston on a couple of stages. Forestry biologist and fellow historical researcher Don Arceneaux joined us for one stage. Together — an Arceneaux, a Doucet, three Guidrys, and a Bernard — we would seek an answer to the profound question, “How many Cajuns does it take to row Bayou Teche?”

Aerial photograph of Stage 1, Port Barre to Arnaudville.

Aerial photograph of Stage 1, Port Barre to Arnaudville.(Source: Google Maps)

We began around 9 am on October 23, 2011, by design a week after the annual Tour du Teche canoe race. (We didn’t want to get in the way of the racers, and so let them go first.) We put in at the public boat dock at Port Barre, on the Courtableau about three hundred yards east of the headwaters of the Teche. Within minutes we were rowing on the Teche itself, which is narrow there (varying from about 75 to 95 feet wide, not much larger than a sizable coulee), with dense tree canopies on either side reaching toward the opposite bank and pressing in toward our canoes.

On the Teche near its origin at Port Barre.

On the Teche near its origin at Port Barre.(Photograph by author)

The current at Port Barre was fairly swift and strong for a bayou — they are usually noted for their slowness — and with our casual rowing it carried our two canoes down the bayou at a decent clip. This fooled us into thinking we would make similarly fast headway the entire length of the bayou; but farther down the current slowed considerably and, eventually, reversed — reducing our progress and making the rowing a more grueling effort. In fact, by the fourth or fifth stage it took us ten or twelve hours to accomplish what we originally did in half that time. But this lesson would not be learned for several more months, undertaking, as we did, a stage every month to month and a half.

The weather that day was cool and the sky mostly clear. Of the group I was the least experienced rower, but Preston, Jacques, and Keith, who rowed often — including in the challenging Atchafalaya swamp — made up for my greenness.

Grazing land along the Teche south of Port Barre.

Grazing land along the Teche south of Port Barre.(Photograph by author)

Shortly after leaving Port Barre we spotted a coyote running parallel to the bayou on the east bank — the first sign of wildlife on our trip. We soon saw a number of large bones on the west bank, probably cattle. Right before that we had caught the strong scent of cattle dung and must have been passing a ranch (or vacherie, as our ancestors would have called it). At about 10:30 am Keith and I (who rode in the same canoe) stopped beside a bridge to wait for Preston and Jacques. As we floated there, someone up above threw a bottle from the window of a passing car: the bottle burst as it clipped the bridge railing and splashed in the water beside me, still in its anonymous paper bag. Keith found this amusing, and I joked someone had tried to kill me.

Shortly after Preston and Jacques caught up with us they spotted a water moccasin swimming in the bayou; surprisingly, it was the only snake we saw during the many stages of our trip.

An old car along the Teche.

An old car along the Teche.(Photograph by author)

I noticed much less garbage on the bayou than expected, certainly a tribute to the efforts of Cajuns for Bayou Teche. This group sponsors the Tour du Teche race and uses funds generated from the event to clean up the bayou. The largest quantity of garbage I saw that day lay inside the city limits of Port Barre, where certain persons used the banks of the bayou as private trash heaps. Outside of town, however, the garbage became less frequent. Some it was clearly vintage, which gave it a certain respectability: no one wants to see a new clothes washing machine or recent-model car half-submerged in the bayou or half-buried in its rising banks; but a rusty Depression-era clothes washer or vintage 1950s coupe are more interesting and even somehow appealing in their antiquity.

Another old car along the Teche.

Another old car along the Teche.(Photograph by author)

Only a few homes lined the Teche between Port Barre and the next bayouside community, Leonville. On the outskirts of Leonville, however, we saw a few suburban-style homes, which removed the illusion of being in wilderness. We reached Leonville at 11:45 am to the sounds of the church carillon. Just south of town, as we headed back into countryside, we spotted a nutria on the bank, scurrying to hide itself from us. Within the hour, just below the Oscar Rivette Bridge, we saw a large owl. Five minutes later we passed under high-voltage transmission lines, whose audible hum and static made me nervous to sit between them and a body of water.

Keith and me (in front) on the Teche.

Keith and me (in front) on the Teche.(Photograph by Jacques Doucet)

We observed pecan pickers here and there just north of the next community on the bayou, Arnaudville, as well as a large bird I recorded as an “anhinga.” I’m no ornithologist, however, but it looked fairly large and sported dark plumage and black legs — possibly not an anhinga, but a little blue heron. We would see many herons or egrets on our stages, often a single large bird whose solitary hunting we interrupted repeatedly, spurring him farther and farther down the bayou in front of our boats.

View of the Teche from my canoe.

View of the Teche from my canoe.(Photograph by author)

At 1:45 pm we arrived in Arnaudville, our terminus for this stage of the trip. We pulled ashore at Myron’s Maison de Manger (excellent burgers), right below the junction of the Teche and Bayou Fuselier.

On the other side of the Fuselier once stood the home of my colonial-era ancestor, Lyons-born planter Gabriel Fuselier de la Claire. It’s an extravagant name, but if he had been a big wheel in France I doubt he would have chosen to brave the south Louisiana frontier. With its heat, humidity, mosquitoes, alligators, pirates, and occasional slave or Indian revolts, the French and Spanish colony was no paradise, despite its idealized portrayals in literature. (See Longfellow’s Evangeline.)

Fuselier de la Claire prospered in Louisiana, however, as did his heirs — but somewhere down the line (probably during Reconstruction) the family lost its fortune and ended up marrying into my impoverished clan of subsistence-farming Cajuns. The same happened to the delaMorandieres, deLivaudaises, and other French Creole aristocrats who wound up in my family tree. After a generation or so nothing remained of them culturally, except for my grandmother’s memory that her elderly in-law, the last delaMorandiere of the line, “spoke that fancy French.”

My favorite photo from that day on the Teche, October 2011.

My favorite photo from that day on the Teche, October 2011.(Photograph by author)

A folksy hand-painted sign hangs beside the bayou near the landing at Myron’s, erected by the local Sons of Confederate Veterans chapter (or “encampment,” as they call it). Erected solely for the benefit of boaters, the sign stated that several steamboats sank at that site during the Civil War.

Sign listing steamboats that sank on that spot during the Civil War.

Sign listing steamboats that sank on that spot during the Civil War.(Photograph by author)

The Official Records of the conflict indicates that the five vessels had been scuttled by the Rebels to keep them from falling into enemy hands. As a Union officer wrote in April 1863:

I was there [Breaux Bridge] informed that the steamboats Darby, Louise, Blue Hammock, and Uncle Tommy had passed up the bayou the day before — that is, the evening of the 16th instant — . . . having valuable stores belonging to the enemy. . . . I sent forward a man up the Bayou Teche to ascertain the position and condition of the boats. He reported next morning that all of them had been burned at the junction [of bayous Teche and Fuselier] as soon as the enemy learned of the arrival of my command at Breaux Bridge. . . . [At] the junction I examined the wreck of four steamboats. The water having risen after the rains of Saturday night and Sunday morning, 18th and 19th instant, I was unable to see any names on the boats, or the guns reported to have been left on the Darby. Their smoke-stacks and part of their machinery only were above water. From all the information I received I have no doubt of their being the Darby, Louise, Blue Hammock, and the Crocket. The Uncle Tommy is burned higher up in the Bayou Teche, and the wreck of this boat is high enough out of water to see her name. Cargoes of beef, rum, sugar, and commissary stores, cloth, uniforms, and large quantities of arms and ammunition were destroyed in these boats. Some barges took off portions of the cargoes of ammunition and arms from these steamboats before they were set on fire. (Source: The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Volume 15, Part 1 (Baton Rouge-Natchez), 343-44.)

Burning steamboats.

Burning steamboats.(Source: Harper's Weekly [1869])

So who knows how many cannons, shot, belt buckles, bullets, and other Civil War artifacts lay in the mud at the bottom of the bayou, artifacts we paddled over unknowingly as our trip that day came to an end?

After 19 miles of rowing we all were exhausted, but I seemed by far in the worst shape. My arms hurt as though I'd been lifting barbells for too long, and my palms, covered with a metallic sheen from the oars, were sore with blisters. "Next time," I thought, "use gloves." By the time I reached home, I hurt all over: I don't exaggerate when I say I've never felt such excruciating pain in my arms, chest, and back. My bones themselves seemed to ache, right down to the marrow. No matter in what position I sat or lay, I could not make the discomfort go away. This was my penalty for undertaking the trip in poor shape. I swallowed some aspirin and slept horribly, but by morning the pain had disappeared except for vague aching in my upper arms. Fortunately, the pain did not return after future stages. I needed this first stage to break myself in.

Published on October 07, 2012 16:10

July 9, 2012

Notes on Two Nineteenth-Century Engravings of South Louisiana Scenes

An acquaintance of mine, former Avery Island salt miner and sometimes sculptor Lonny Badeaux, recently showed me a photograph of one of his marble sculptures: a young woman washing laundry on her knees, with the annotation in Greek "Déjà Vu" (or so Lonny told me — I can't read Greek).

Badeaux's sculpture.

Badeaux's sculpture.

(Photo by Lonny Badeaux)

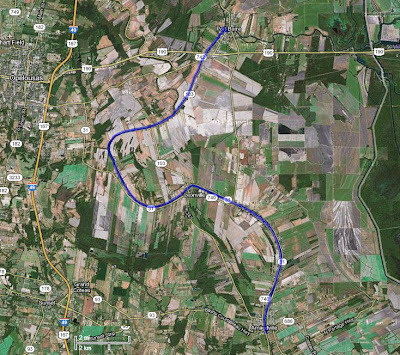

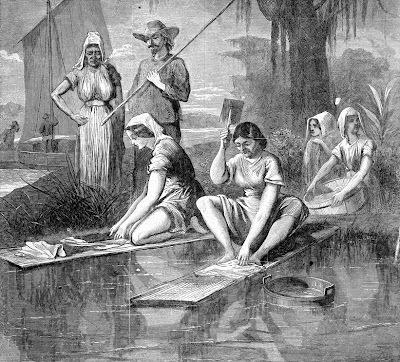

Lonny also showed me the inspiration for this work. As it turned out, I knew it well: An 1866 A. R. Waud engraving from Harper's Weekly showing Acadian (Cajun) women washing their laundry in Bayou Lafourche.

The inspiration for Badeaux's work,

The inspiration for Badeaux's work,

from an 1866 Harper's engraving.

I knew the image because I'd first seen it many years earlier as an illustration in Carl A. Brasseaux's excellent book, Acadian to Cajun: Transformation of a People, 1803-1877 .

The entire 1866 Harper's engraving, titled

The entire 1866 Harper's engraving, titled

"Washing-Day among the Acadians on the Bayou Lafourche, Louisiana."

In that book Brasseaux wrote of the engraving in question:

Brasseaux refers to the washerwomen engraving as Waud's "most notorious Louisiana illustration," adding that Waud "was perhaps most responsible for creating the negative national stereotype of the Cajuns, because of his dark sketches which emphasized his personal revulsion for the region's strange landscape and its even more exotic inhabitants." Furthermore, Brasseaux called Waud's accompanying article for Harper's "perhaps the most notorious" of negative Acadian stereotypes created by Northern journalists in the post-Civil War period. Here is an excerpt of that 1866 article:

Cover of Brasseaux's

Acadian to Cajun

.

Cover of Brasseaux's

Acadian to Cajun

.

Note that Waud's engraving serves as the book's cover art.

Waud himself noted of his engraving:

Badeaux knew of Waud's negative view of the Cajuns, having photocopied the author's vituperative article along with the engraving. Himself a Cajun, Badeaux nonetheless chose to use Waud's engraving as a model for his work of art. The finished sculpture now sits in Badeaux's yard in New Iberia; but with his permission I might try to find another home for it, so that the public can enjoy his modern interpretation of Waud's condemnatory original.

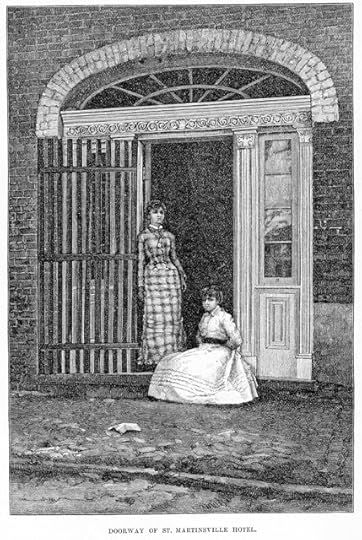

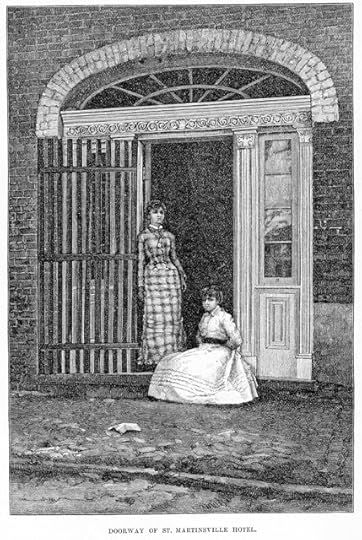

This reminds me of another nineteenth-century engraving, namely, of two women standing in the doorway of a St. Martinville hotel.

"Doorway of St. Martinville Hotel,"

"Doorway of St. Martinville Hotel,"

1887 Harper's engraving.

This image illustrates an 1887 article, also in Harper's, by author Charles Dudley Warner, whose depiction of Cajuns was a bit more complimentary than Waud's. Which is to say that when Warner's article denigrates Cajuns, it is not Warner himself who does so, but a local interviewee:

What I find intriguing about this 1887 engraving is that it shows a doorway that still exists; indeed, it is still a hotel doorway. It is the front door the Old Castillo Hotel, now known as La Place d'Evangeline, located in St. Martinville on the east bank of Bayou Teche next to the Evangeline Oak. (I have never stayed there, but the late Colonel Wallace J. Moulis, St. Martinville native, World War II veteran, and career military man formerly assigned to NATO, once treated me to an excellent dish of crawfish bisque in the hotel's dining room.)

The same doorway as it looks today,

The same doorway as it looks today,

125 years after it appeared in a Harper's engraving.

(Photo by the author, June 2012)

As Warner wrote in his Harper's article, titled "The Acadian Land":

Old Castillo Hotel, now known as

Old Castillo Hotel, now known as

La Place d'Evangeline,

St. Martinville, La.

(Photo by the author, June 2012)

Sources:

Carl A. Brasseaux, Acadian to Cajun: Transformation of a People, 1803-1877 (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1992).

Charles Dudley Warner, "The Acadian Land," Harper's New Monthly Magazine LXXIV (February 87), p. 345.

A.R.W. [A. R. Waud], "Acadians of Louisiana," Harper's Weekly X (20 October 1866), p. 657.

Badeaux's sculpture.

Badeaux's sculpture.(Photo by Lonny Badeaux)

Lonny also showed me the inspiration for this work. As it turned out, I knew it well: An 1866 A. R. Waud engraving from Harper's Weekly showing Acadian (Cajun) women washing their laundry in Bayou Lafourche.

The inspiration for Badeaux's work,

The inspiration for Badeaux's work,from an 1866 Harper's engraving.

I knew the image because I'd first seen it many years earlier as an illustration in Carl A. Brasseaux's excellent book, Acadian to Cajun: Transformation of a People, 1803-1877 .

The entire 1866 Harper's engraving, titled

The entire 1866 Harper's engraving, titled"Washing-Day among the Acadians on the Bayou Lafourche, Louisiana."

In that book Brasseaux wrote of the engraving in question:

Waud included with his short article [about the Acadians] a woodcut showing two Acadian washerwomen, their legs exposed to mid-thigh, a clear message of cultural and moral depravity to Victorian America. The image also featured prominently a woman smoking a corncob pipe and an idle (and thus manifestly lazy) man holding a small net used for recreational fishing, watching the women work nearby.

Brasseaux refers to the washerwomen engraving as Waud's "most notorious Louisiana illustration," adding that Waud "was perhaps most responsible for creating the negative national stereotype of the Cajuns, because of his dark sketches which emphasized his personal revulsion for the region's strange landscape and its even more exotic inhabitants." Furthermore, Brasseaux called Waud's accompanying article for Harper's "perhaps the most notorious" of negative Acadian stereotypes created by Northern journalists in the post-Civil War period. Here is an excerpt of that 1866 article:

These primitive people are the descendants of Canadian French settlers in Louisiana; and by dint of intermarriage they have succeeded in getting pretty well down in the social scale.Without energy, education, or ambition, they are good representatives of the white trash, behind the age in every thing. The majority of all the white inhabitants of these parishes are tolerably ignorant, but these are grossly so — so little are they thought of — that the niggers, when they want to express contempt for one of their own race, call him an Acadian nigger. . . .

To live without effort is their apparent aim in life, and they are satisfied with very little, and are, as a class, quite poor. Their language is a mixture of French and English, quite puzzling to the uninitiated. . . .

With a little mixture of fresh blood and some learning they might become much improved, and have higher aims than the possession of land enough to grow their corn and a sufficiency of "goujon" [gudgeon, a type of freshwater fish]. . . .

Cover of Brasseaux's

Acadian to Cajun

.

Cover of Brasseaux's

Acadian to Cajun

.Note that Waud's engraving serves as the book's cover art.

Waud himself noted of his engraving:

Washing day is a sketch from life. These simple folks have no acquaintance apparently with the wash-board, nor do they employ their knuckles. Placing their clothes upon a plank, either on the edge of a pool or the bayou, they draw their scanty drapery about them with the most reckless disregard to the exposure consequent, and squatting, or kneeling, beat them with a wooden bat. The approach of a stranger does not disconcert them much, if at all.

Badeaux knew of Waud's negative view of the Cajuns, having photocopied the author's vituperative article along with the engraving. Himself a Cajun, Badeaux nonetheless chose to use Waud's engraving as a model for his work of art. The finished sculpture now sits in Badeaux's yard in New Iberia; but with his permission I might try to find another home for it, so that the public can enjoy his modern interpretation of Waud's condemnatory original.

This reminds me of another nineteenth-century engraving, namely, of two women standing in the doorway of a St. Martinville hotel.

"Doorway of St. Martinville Hotel,"

"Doorway of St. Martinville Hotel,"1887 Harper's engraving.

This image illustrates an 1887 article, also in Harper's, by author Charles Dudley Warner, whose depiction of Cajuns was a bit more complimentary than Waud's. Which is to say that when Warner's article denigrates Cajuns, it is not Warner himself who does so, but a local interviewee:

My driver was an ex-Confederate soldier, whose tramp with a musket through Virginia had not greatly enlightened him as to what it was all about. As to the Acadians, however, he had a decided opinion, and it was a poor one. They are no good. “You ask them a question, and they shrug their shoulders like a tarrapin — don’t know no more’n a dead alligator; only language they ever have is ‘no’ and ‘what?’”

What I find intriguing about this 1887 engraving is that it shows a doorway that still exists; indeed, it is still a hotel doorway. It is the front door the Old Castillo Hotel, now known as La Place d'Evangeline, located in St. Martinville on the east bank of Bayou Teche next to the Evangeline Oak. (I have never stayed there, but the late Colonel Wallace J. Moulis, St. Martinville native, World War II veteran, and career military man formerly assigned to NATO, once treated me to an excellent dish of crawfish bisque in the hotel's dining room.)

The same doorway as it looks today,

The same doorway as it looks today, 125 years after it appeared in a Harper's engraving.

(Photo by the author, June 2012)

As Warner wrote in his Harper's article, titled "The Acadian Land":

I went to breakfast at a French inn, kept by Madame Castillo, a large red-brick house on the banks of the Teche, where the live-oaks cast shadows upon the silvery stream. It had, of course, a double gallery. Below, the waiting-room, dining-room, and general assembly-room were paved with brick, and instead of a door, Turkey-red curtains hung in the entrance, and blowing aside, hospitality invited the stranger within. The breakfast was neatly served, the house was scrupulously clean, and the guest felt the influence of that personal hospitality which is always so pleasing. Madame offered me a seat in her pew in church, and meantime a chair on the upper gallery, which opened from large square sleeping chambers. In that fresh morning I thought I never had seen a more sweet and peaceful place than this gallery. Close to it grew graceful China-trees in full blossom and odor; up and down the Teche were charming views under the oaks; only the roofs of the town could be seen amid the foliage of China-trees; and there was an atmosphere of repose in all the scene. It was Easter morning. I felt that I should like to linger there a week in absolute forgetfulness of the world. . . .

Old Castillo Hotel, now known as

Old Castillo Hotel, now known asLa Place d'Evangeline,

St. Martinville, La.

(Photo by the author, June 2012)

Sources:

Carl A. Brasseaux, Acadian to Cajun: Transformation of a People, 1803-1877 (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1992).

Charles Dudley Warner, "The Acadian Land," Harper's New Monthly Magazine LXXIV (February 87), p. 345.

A.R.W. [A. R. Waud], "Acadians of Louisiana," Harper's Weekly X (20 October 1866), p. 657.

Published on July 09, 2012 12:55

July 1, 2012

Finding History Right around the Corner: Heroism on the Cajun Home Front

The following serves as a good example of how history can be found right around the corner, literally, if you look for it.

In my book The Cajuns: Americanization of a People I wrote:

As it turns out, a residence only a block from my house served as a quarantine house for some of those who contracted the disease. As the Baton Rouge Sunday Advocate reported eighteen years later in 1961:

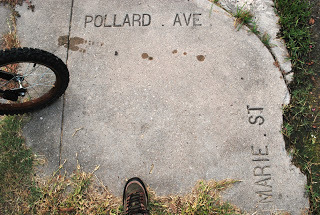

142 Pollard Avenue, New Iberia, Louisiana,

142 Pollard Avenue, New Iberia, Louisiana,

as it looks today (July 2012).

(Photo by the author)

The article continued:

The disease, however, was a potent one, taking the lives of both nurses Bourgeois and Bonin in March 1943.

Katherine Avery, one of the five nurses who entered

Katherine Avery, one of the five nurses who entered

the quarantine house on Pollard Avenue.

(Source: Avery Island, Inc., Archives)

"Back in the house on Pollard Avenue," recorded the Sunday Advocate , "the five women were hopefully waiting out their 21 days quarantine after the deaths of the two nurses." However, one of the five, Gerhart, contracted the disease. "But the people of the community then decided that they had assumed more than their fair share of the risk and an old plantation home six miles outside town was obtained. Three of the women were put in quarantine out there. . . . The [two remaining] women on Pollard Avenue waited out their 21 days and the quarantine was broken." (Gerhart survived after "repeated transfusions from recovered patients" under the supervision of Dr. Landry.)

Old street identifications in the pavement,

Old street identifications in the pavement,

New Iberia, Louisiana (July 2012).

(Photo by the author)

Much of this story transpired, commented the New Iberia Daily Iberian in response to the Advocate article, in "a house that still stands on Pollard Avenue" — as it stands today on that quiet suburban street . . . a quaint reminder of wartime heroism on the Cajun home front.

Nurse and patient Remas Gerhart, seated,

Nurse and patient Remas Gerhart, seated,

with additional nurse volunteers;

photo taken at 142 Pollard Avenue.

(Note house with tell-tale eaves in background.)

(Source: Sunday Advocate; original source unknown)

Sources: James H. Hughes, Jr., "Strange Malady Spread Terror through the Marshlands," (Baton Rouge) Sunday Advocate, 1 October 1961, p. 1-E; Jim Levy, "Talk of the Teche [column]," [(New Iberia) Daily Iberian], ca. 1 October 1961, n.p.

In my book The Cajuns: Americanization of a People I wrote:

As occurred elsewhere in the nation [during World War II], wartime anxiety sometimes escalated into wartime hysteria. When a highly contagious disease wiped out hundreds of muskrats in the coastal marshlands and spread to nineteen south Louisianians, killing eight, rumor circulated that the outbreak had been caused by Japanese germ warfare. Fearing widespread panic, the federal government moved in, quarantined all possible disease carriers, and asked the media to refrain from reporting the incident. The disease was eventually identified as psittacosis, or "parrot fever," a viral infection transmitted by birds (p. 13).

As it turns out, a residence only a block from my house served as a quarantine house for some of those who contracted the disease. As the Baton Rouge Sunday Advocate reported eighteen years later in 1961:

On March 3 [1943] the focus of the epidemic shifted from Ville Platte and Rayne to New Iberia. Miss Antoinette Bourgeois, one of the nurses from New Iberia who had volunteered to help at Rayne, felt a pain at the base of her neck. Miss Antoinette Bonin, also a nurse who had helped, felt the same pain plus a headache. They were returned to New Iberia and placed in quarantine in a duplex at 142 Pollard Avenue. Dr. Edwin L. Landry attended them and five women volunteers entered the house to care for them, knowing that their chances of ever leaving alive were about fifty-fifty.

142 Pollard Avenue, New Iberia, Louisiana,

142 Pollard Avenue, New Iberia, Louisiana,as it looks today (July 2012).

(Photo by the author)

The article continued:

The volunteers were Miss Cecile Bourgeois, a sister of Miss Antoinette Bourgeois, two sisters of Miss Bonin, Miss Helen Hobart and Miss Remas Gerhart. The physicians and Miss Katherine Avery, Iberia Parish Public Health nurse, entered the house frequently, always taking elaborate, almost ritualistic precautions. The townspeople, however, were deathly afraid of the disease. Some crossed to the opposite side of the street before passing the house. When groceries were delivered they were left on the sidewalk. Dr. Landry and Miss Avery were shunned.

The disease, however, was a potent one, taking the lives of both nurses Bourgeois and Bonin in March 1943.

Katherine Avery, one of the five nurses who entered

Katherine Avery, one of the five nurses who enteredthe quarantine house on Pollard Avenue.

(Source: Avery Island, Inc., Archives)

"Back in the house on Pollard Avenue," recorded the Sunday Advocate , "the five women were hopefully waiting out their 21 days quarantine after the deaths of the two nurses." However, one of the five, Gerhart, contracted the disease. "But the people of the community then decided that they had assumed more than their fair share of the risk and an old plantation home six miles outside town was obtained. Three of the women were put in quarantine out there. . . . The [two remaining] women on Pollard Avenue waited out their 21 days and the quarantine was broken." (Gerhart survived after "repeated transfusions from recovered patients" under the supervision of Dr. Landry.)

Old street identifications in the pavement,

Old street identifications in the pavement,New Iberia, Louisiana (July 2012).

(Photo by the author)

Much of this story transpired, commented the New Iberia Daily Iberian in response to the Advocate article, in "a house that still stands on Pollard Avenue" — as it stands today on that quiet suburban street . . . a quaint reminder of wartime heroism on the Cajun home front.

Nurse and patient Remas Gerhart, seated,

Nurse and patient Remas Gerhart, seated, with additional nurse volunteers;

photo taken at 142 Pollard Avenue.

(Note house with tell-tale eaves in background.)

(Source: Sunday Advocate; original source unknown)

Sources: James H. Hughes, Jr., "Strange Malady Spread Terror through the Marshlands," (Baton Rouge) Sunday Advocate, 1 October 1961, p. 1-E; Jim Levy, "Talk of the Teche [column]," [(New Iberia) Daily Iberian], ca. 1 October 1961, n.p.

Published on July 01, 2012 18:47

June 15, 2012

My Father's Childhood Autograph Book on the History Channel?*

Last night I was grocery shopping near my home in New Iberia when a woman I know came up to me and said, "Yesterday I was watching the History Channel and saw the episode of 'Cajun Pawn Stars' that mentioned your father."

I shook my head and replied that I didn't know what she meant. Surprised I was unaware of the program, she explained, "On the show a man went into the pawn shop with a battered little booklet, and inside the front cover was written 'My autograph book, Rodney Bernard, Opelousas, Louisiana, 1950.'"

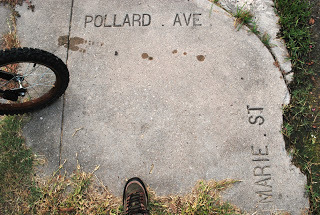

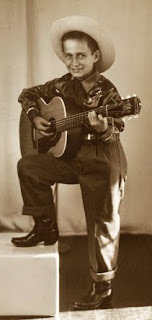

Dad around the time he met

Dad around the time he met

Hank Williams Sr. (ca. 1950).

(Author's collection)

"Well, yes," I replied, "that's my father's name and he did have an autograph book when he was a kid."

"And in the book," she continued, "were the autographs of Hank Williams Sr. and all the members of his band, the Drifting Cowboys, and also the autographs of Hank Snow, Ray Price, Grandpa Jones, and other Grand Ole Opry stars."

"That's right, too" I responded, amazed at the unfolding story. "My dad did have such an autograph book."

In fact, I explained, I kept it for him for many years. But about four years ago he asked me to sell it on eBay, so I put it up for auction for approximately $5,000. No one bid on it, so he asked me to return the book to him. Dad ended up trading it to a friend for something or another. This friend is a Hank Williams' fanatic and, last Dad saw the autograph booklet, it was framed and hanging on this friend's wall in Lafayette, its pages opened to Hank Williams' autograph.

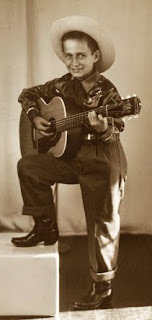

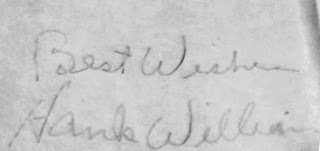

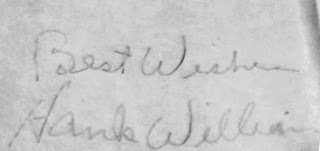

Hank Williams Sr.'s signature in my father's autograph book.

Hank Williams Sr.'s signature in my father's autograph book.

The woman told me that the pawn shop owner estimated the value of the book — mind you, I'm getting all this second-hand, and have not seen the show for myself — at $15,000 if the book were kept together, $18,000 if it were cut up into individual autographs. "The man with the book offered to sell it then and there," she told me, "but the pawn shop owner thought the price too high. So the man left with the book." [I've now seen the episode, and — if I remember correctly — the prices were $15,000 if cut up and sold as individual autographs and $10,000 if kept together.]

Interestingly, this man was not the person to whom my father gave the book.

During the episode the show properly identified my dad as a south Louisiana singer and mentioned the need to authenticate the autographs.

If "Cajun Pawn Stars" had contacted Dad, however, he could have explained that he met Hank Williams Sr. backstage at the Yambilee Festival in Opelousas around 1950, and got the autograph of Williams and his band at that time. As Dad told me in 1991, and as I quoted him in my book Swamp Pop: Cajun and Creole Rhythm and Blues (University Press of Mississippi, 1996):

Dad also could have explained that as a member of the Cajun swing band the Blue Room Gang, he visited the Grand Ole Opry around the same time and collected many of the other autographs in the book.

Dad (at front center) with members

Dad (at front center) with members

of the Blue Room Gang, ca. 1950.

(Author's collection)

Regardless, how Dad's childhood autograph book ended up on national TV remains unknown at present.

There is, however, a companion autograph booklet that belonged to Dad as a child, and that one I still have in my possession.

Addendum of 15 June 2012:

A number of websites have picked up on the autograph book's appearance on 'Cajun Pawn Stars,' including The Huffington Post, where you can see a video clip from the episode.

In addition, here is a list of all the notable signatures in Dad's autograph book:

____________

*Yes, I know, technically the network's name is not "the History Channel," but simply "History." No one, however, calls it that. Who says, "I was watching History last night"?

I shook my head and replied that I didn't know what she meant. Surprised I was unaware of the program, she explained, "On the show a man went into the pawn shop with a battered little booklet, and inside the front cover was written 'My autograph book, Rodney Bernard, Opelousas, Louisiana, 1950.'"

Dad around the time he met

Dad around the time he met Hank Williams Sr. (ca. 1950).

(Author's collection)

"Well, yes," I replied, "that's my father's name and he did have an autograph book when he was a kid."

"And in the book," she continued, "were the autographs of Hank Williams Sr. and all the members of his band, the Drifting Cowboys, and also the autographs of Hank Snow, Ray Price, Grandpa Jones, and other Grand Ole Opry stars."

"That's right, too" I responded, amazed at the unfolding story. "My dad did have such an autograph book."

In fact, I explained, I kept it for him for many years. But about four years ago he asked me to sell it on eBay, so I put it up for auction for approximately $5,000. No one bid on it, so he asked me to return the book to him. Dad ended up trading it to a friend for something or another. This friend is a Hank Williams' fanatic and, last Dad saw the autograph booklet, it was framed and hanging on this friend's wall in Lafayette, its pages opened to Hank Williams' autograph.

Hank Williams Sr.'s signature in my father's autograph book.

Hank Williams Sr.'s signature in my father's autograph book.The woman told me that the pawn shop owner estimated the value of the book — mind you, I'm getting all this second-hand, and have not seen the show for myself — at $15,000 if the book were kept together, $18,000 if it were cut up into individual autographs. "The man with the book offered to sell it then and there," she told me, "but the pawn shop owner thought the price too high. So the man left with the book." [I've now seen the episode, and — if I remember correctly — the prices were $15,000 if cut up and sold as individual autographs and $10,000 if kept together.]

Interestingly, this man was not the person to whom my father gave the book.

During the episode the show properly identified my dad as a south Louisiana singer and mentioned the need to authenticate the autographs.

If "Cajun Pawn Stars" had contacted Dad, however, he could have explained that he met Hank Williams Sr. backstage at the Yambilee Festival in Opelousas around 1950, and got the autograph of Williams and his band at that time. As Dad told me in 1991, and as I quoted him in my book Swamp Pop: Cajun and Creole Rhythm and Blues (University Press of Mississippi, 1996):

I met Hank Williams Sr. when I was about eight years old, I guess . . . no, I was probably about nine, 'cause he died, what, 1950? [Williams died in 1953.] It was probably about a year before he died. He played at the Opelousas High School gym. . . . Mr. Dezauche [a local businessman] took me backstage and Hank Williams was standing there in his underwear. I'll never forget that. And I walked up to him and that was my god at the time — or a god, it was like Elvis later on. Man, to see Hank Williams Sr. in person standing there! And he shook hands with me and I had an autograph book and he signed my autograph book and I found out later that he never signed many autographs, that he didn't really like to sign autographs. . . (p. 146).

Dad also could have explained that as a member of the Cajun swing band the Blue Room Gang, he visited the Grand Ole Opry around the same time and collected many of the other autographs in the book.

Dad (at front center) with members

Dad (at front center) with members of the Blue Room Gang, ca. 1950.

(Author's collection)

Regardless, how Dad's childhood autograph book ended up on national TV remains unknown at present.

There is, however, a companion autograph booklet that belonged to Dad as a child, and that one I still have in my possession.

Addendum of 15 June 2012:

A number of websites have picked up on the autograph book's appearance on 'Cajun Pawn Stars,' including The Huffington Post, where you can see a video clip from the episode.

In addition, here is a list of all the notable signatures in Dad's autograph book:

Hank Williams Sr. & His Drifting Cowboys, including band members Floyd Cramer, Don Helms, Jimmy Day, Tommy Bishop and Jerry RiversFinally, I learned late today that the autograph book is still in the possession of my father's friend and that it was never really up for sale. How it ended up on the "Cajun Pawn Stars" show, however, is a complicated matter and one I don't want to discuss here. Suffice it to say, the book is safe and in no danger of being dissected and sold off piecemeal . . . at least, not for now.

Chet Atkins

Roy Acuff

Eddie Hill

Hank Snow

June Carter (Cash)

George Morgan (signed twice; Lorrie Morgan's father)

Goldie Hill and Tommy Hill

Red Sovine

Ray Price

The Duke of Paducah (comedian)

T. Texas Tyler

Little Jimmy Dickens (signed twice, once in pencil, once in pen)

Ott Devine (WSM Radio Grand Ole Opry MC)

Oswald (comedian)

Faron Young

Marty Robbins

Cowboy Copas

Webb Pierce

Mother Maybelle Carter

Carl Smith

Grandpa Jones

Martha Carson

Moon Mulligan

Autry Inman

Hank Williams III (2001 autograph in same ca. 1950 autograph book)

____________

*Yes, I know, technically the network's name is not "the History Channel," but simply "History." No one, however, calls it that. Who says, "I was watching History last night"?

Published on June 15, 2012 13:22

May 31, 2012

My Oddball Collection of Cajun Warplane Photos

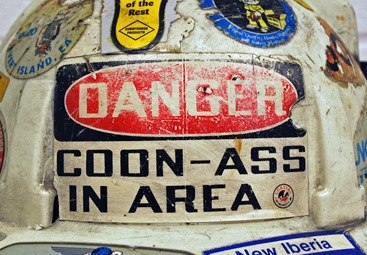

As I mentioned in one of my previous articles, I discovered a photo in the National Archives and Records Administration showing a U.S. World War II transport plane (a C-47, to be precise) with the nickname Cajun Coonass painted on its fuselage. I also found motion picture footage of the same plane. (See my previous article on the Cajun Coonass.)

The Cajun Coonass C-47 transport plane,

The Cajun Coonass C-47 transport plane,Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, 1943.

(National Archives and Records Administration)

Not only did this discovery lead, in my opinion, to the debunking of the alleged etymology of the word "coonass" (a controversial term meaning "Cajun"); it also led to my interest in collecting images of Cajun-themed warplanes.

For example, I purchased at auction an original B&W print and negative of a B-29 bomber named the Cajun Queen.

The Cajun Queen B-29 bomber,

The Cajun Queen B-29 bomber, possibly in Asia or the Pacific, ca. 1945.

(Author's collection)

Here is the same plane from a different angle:

(Author's collection)

(Author's collection)Other images of this plane are known to exist and some of them show a B-29 of the same name but with different nose art. Here is an example:

The Cajun Queen B-29 bomber,

The Cajun Queen B-29 bomber,different nose art, ca. 1945.

(Courtesy Randy Colby)

Could this be the same plane, but repainted? Or a replacement plane bearing the same name? In any event, each of the images shows a plane belonging to the 678th Bombardment Squadron, 444th Bombardment Group — the emblem of the 678th being a cobra spitting a bomb, both superimposed against a spade inside a circle.

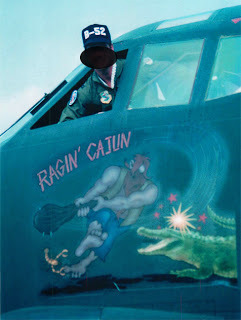

I recently met a US Air Force pilot who told me he knew of a B-52 bomber named the Ragin' Cajun. After returning to his airbase he sent me a photo of the plane in question. I show it here, but blot out the pilot's face for privacy's sake. (By coincidence, the phrase "Ragin' Cajun" was used as a nickname as early as 1950 by U.S. Marine Corps Reserve fighter squadron VMF-143. See my previous article on this subject.) Note that the neanderthalic (and stereotypical) Cajun is whacking an alligator over the head while a crawfish bites him on the toe — alligators and crawfish being symbols of Cajun ethnicity.

The Ragin' Cajun B-52 bomber, no date.

The Ragin' Cajun B-52 bomber, no date.(Source: Anonymous)

Likewise, a search of the Internet turned up the image of another Cajun-themed B-52 bomber: the Cajun Fear. Like the Ragin' Cajun, the Cajun Fear shows a rampant alligator, in this case seemingly bursting through the plane's fuselage. (Note the image of the state of Louisiana at lower right corner.)

The Cajun Fear B-52 bomber, 2011. (Courtesy Bruce Smith)

The Cajun Fear B-52 bomber, 2011. (Courtesy Bruce Smith)To bring up the "C word" again: "Coonass Militia" used to be the nickname of the Louisiana Air National Guard's 159th Tactical Fighter Group.

F-4C Phantom jet with "Coonass Militia" emblem, 1983.

F-4C Phantom jet with "Coonass Militia" emblem, 1983.(Click to enlarge; courtesy Gerrit Kok)

According to the Times-Picayune, the group changed its name in 1992 (no doubt because of complaints about the word "coonass," which some consider an ethnic slur against Cajuns). (Source: Ron Thibodeaux, "'Coonass' Carries Baggage Some Prefer to Leave Behind," Times-Picayune, 17 July 2001, accessed 1 June 2012.) It now goes by the nickname "Louisiana Bayou Militia," whose current emblem incorporates French fleurs-de-lis and traditional Mardi Gras colors, symbols associated with the state of Louisiana.

"Bayou Militia" emblem on jet fighter's vertical stabilizer, 2011.

"Bayou Militia" emblem on jet fighter's vertical stabilizer, 2011.(Photograph by author)

Here is one more Cajun-related, if not Cajun-themed, warplane: A full-scale replica of the P-40 Flying Tiger flown by Cajun fighter pilot Wiltz P. Segura.

Replica of Cajun pilot Wiltz P. Segura's P-40 Flying Tiger warplane,

Replica of Cajun pilot Wiltz P. Segura's P-40 Flying Tiger warplane,USS Kidd Veterans Memorial, Baton Rouge, La., 2012.

(Photograph by author)

Hailing from my adopted town of New Iberia, Segura joined the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1942 as an aviation cadet and received his commission the next year as a second lieutenant. As his U.S. Air Force biographical sketch notes:

During his World War II tour of duty in China . . . Segura flew 102 combat missions, destroyed one Japanese bomber and five fighter aircraft, and was credited with damaging three more. He was shot down twice by ground fire but each time parachuted to safety and successfully evaded enemy capture behind the lines. . . . In October 1965 he was assigned to England Air Force Base, La., as vice commander of the 3d Tactical Fighter Wing, and retained that position when the wing was transferred in November 1965 to Bien Hoa Air Base, Republic of Vietnam. During an extended absence of the wing commander, he assumed command. . . . Segura flew more than 125 combat missions in the F-100, and F-5 aircraft, and was the first pilot to check out in the F-5 in the combat theater. (Source: Wiltz P. Segura biographical sketch, U.S. Air Force web site, accessed 31 May 2012)

By the time of Segura's retirement he had attained the rank of brigadier general.

Close up of Wiltz P. Segura's P-40 fuselage.

Close up of Wiltz P. Segura's P-40 fuselage.(Photograph by author)

If you have photographs of other Cajun-themed warplanes — I'm sure there must be a very finite number of such aircraft — please let me know. I'd like to add them to my collection.

Incidentally, a few years ago I designed a faux Cajun-themed-World War II-nose-art T-shirt. Actually, I mixed bits and pieces of pre-existing art from around the Internet with my own art to create this T-shirt. Here is the design. . . .

Of course, "Jolie Blonde" (French for "Pretty Blonde") is a famous Cajun song, considered by many to be the "Cajun national anthem." If there was never a warplane by this name, there should have been!

Published on May 31, 2012 14:15

May 11, 2012

My Cajun Book for Children Soon Available in French Translation

I'm pleased to announce that my 2008 book, Cajuns and Their Acadian Ancestors: A Young Reader's History, will be available in May 2013 in a French translation by Faustine Hillard.

J’ai le plaisir d’annoncer que mon livre intitulé Les Cadiens et leurs ancêtres acadiens: l'histoire racontée aux jeunes sera disponible en mai 2013 en version française, traduite par Faustine Hillard.

[image error] Cover of the English version and the French translation.

Couverture du livre en anglais et la traduction en français.

Published by the University Press of Mississippi and funded in part through a translation grant from the

Quebec Ministère des Relations Internationales, the book, retitled Les Cadiens et leurs ancêtres acadiens: l'histoire racontée aux jeunes, is aimed at middle-school and high-school readers — though it is useful as an adult primer — particularly students in French Immersion and other French education courses.

Publié par la Presse Universitaire du Mississippi et financé en partie par une subvention du Ministère des Relations Internationales du Québec, le livre, intitulé Les Cadiens et leurs ancêtres acadiens: l'histoire racontée aux jeunes, cible le jeune lecteur collégien ou lycéen, surtout celui des classes d’immersion en français ou ceux qui apprennent le français langue seconde. Il s'avère toutefois une introduction enrichissante au lecteur adulte voulant s’initier à la question.

Inside the French version. (click to enlarge)

Inside the French version. (click to enlarge)

L'intérieur de la version en français. (Cliquez pour agrandir.)

Of the English version, the Times-Picayune noted:

Au sujet de la version en anglais, le quotidien de la Nouvelle Orléans, The Times-Picayune, remarqua:

En 2008, Les Cadiens et leurs ancêtres acadiens: l'histoire racontée aux jeunes (version langue anglaise) fut sélectionné par le Centre du Livre en Louisiane, qui se trouve à la bibliothèque de l’état, pour représenter la Louisiane au Pavillon des Etats du Festival National du Livre à Washington, D.C.

Inside the French version. (click to enlarge)

Inside the French version. (click to enlarge)

L'intérieur de la version en français. (Cliquez pour agrandir.)

If you wish to be notified of the French translation's release, please e-mail me at: inf...@cajunculture.com [Click on the "..." to reveal the full e-mail address]

Pour être averti de la date de sortie de la traduction en français, veuillez m’envoyer un message électronique à l'adresse suivante: inf...@cajunculture.com [Click on the "..." to reveal the full e-mail address]

J’ai le plaisir d’annoncer que mon livre intitulé Les Cadiens et leurs ancêtres acadiens: l'histoire racontée aux jeunes sera disponible en mai 2013 en version française, traduite par Faustine Hillard.

[image error] Cover of the English version and the French translation.

Couverture du livre en anglais et la traduction en français.

Published by the University Press of Mississippi and funded in part through a translation grant from the

Quebec Ministère des Relations Internationales, the book, retitled Les Cadiens et leurs ancêtres acadiens: l'histoire racontée aux jeunes, is aimed at middle-school and high-school readers — though it is useful as an adult primer — particularly students in French Immersion and other French education courses.

Publié par la Presse Universitaire du Mississippi et financé en partie par une subvention du Ministère des Relations Internationales du Québec, le livre, intitulé Les Cadiens et leurs ancêtres acadiens: l'histoire racontée aux jeunes, cible le jeune lecteur collégien ou lycéen, surtout celui des classes d’immersion en français ou ceux qui apprennent le français langue seconde. Il s'avère toutefois une introduction enrichissante au lecteur adulte voulant s’initier à la question.

Inside the French version. (click to enlarge)

Inside the French version. (click to enlarge)L'intérieur de la version en français. (Cliquez pour agrandir.)

Of the English version, the Times-Picayune noted:

Au sujet de la version en anglais, le quotidien de la Nouvelle Orléans, The Times-Picayune, remarqua:

Bernard takes just 85 pages to provide a concise history of one of the unique peoples that make Louisiana special. It is a brief but delightfully engaging account of who the Cajuns are and how they got that way, a narrative as informative as it is easy to navigate. . . . [The book] fills an important gap on the Louisiana history bookshelf, and its value can be appreciated by the not-so-young as well.

Bernard nous raconte l'histoire abrégée d’un des peuples qui contribue à l'extraordinaire mosaïque démographique de la Louisiane en un récit de moins de 85 pages. Ce bref mais charmant compte rendu entraîne le lecteur à découvrir le peuple cadien et suivre son évolution dans un récit qui informe tout en restant facile à naviguer. . . . [Ce livre] comble une lacune importante en ce qui est de l'histoire de la Louisiane. C'est un livre qui s'apprécie à tout âge.In 2008 the Louisiana Center for the Book, located in the state library, selected the English version of Cajuns and Their Acadian Ancestors to represent Louisiana at the National Book Festival's Pavilion of the States in Washington, D.C.

En 2008, Les Cadiens et leurs ancêtres acadiens: l'histoire racontée aux jeunes (version langue anglaise) fut sélectionné par le Centre du Livre en Louisiane, qui se trouve à la bibliothèque de l’état, pour représenter la Louisiane au Pavillon des Etats du Festival National du Livre à Washington, D.C.

Inside the French version. (click to enlarge)

Inside the French version. (click to enlarge)L'intérieur de la version en français. (Cliquez pour agrandir.)

If you wish to be notified of the French translation's release, please e-mail me at: inf...@cajunculture.com [Click on the "..." to reveal the full e-mail address]

Pour être averti de la date de sortie de la traduction en français, veuillez m’envoyer un message électronique à l'adresse suivante: inf...@cajunculture.com [Click on the "..." to reveal the full e-mail address]

Published on May 11, 2012 14:53

April 18, 2012

Elodie's Gift: A Family Photographic Mystery

This article is a draft at present:

Here is a photo that my great aunt, the late Elodie Bernard (married name Fontenot), gave me when I visited her around 1980.

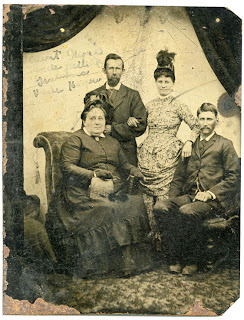

The mystery photo.

The mystery photo.

(Author's collection)

I remember Aunt Elodie as an elderly, white-haired woman, thin and gaunt. She seemed a stranger to me because, for whatever reason, Elodie never came to family get-togethers, whether for Christmas or Easter or what have you. Only rarely had I heard her name mentioned, and while I have no reason to believe there was any schism that kept her apart from us, it seemed odd to me that the extended family on my father's Cajun side of my family was hardly as close as the extended family on my mother's Anglo-Saxon side of the family. I am by no means making a sweeping implication about Cajuns: on the contrary, Cajuns, if anything, are known for the closeness of their extended families. It just seemed odd that Elodie never showed up at our family gatherings and that I really knew nothing about her, so much so that as a child I barely knew her name, much less what she looked like.

When Aunt Elodie gave me this photo, she explained that it depicted some of our ancestors. She explained to me that it showed my paternal great-great grandparents. It certainly did not show my paternal great-grandparents, for my grandfather's father was the splitting image of his son and I would have recognized him instantly. I recognized no one, however, in this image.

I remain uncertain who is shown in the image and if they are even really my relatives. So I thought I might analyze the photograph and try to determine who these people are.

Often mistakenly called a daguerreotype (including by me), the image is actually a tintype, which the Library of Congress describes as a "Direct-image photograph . . . in which the collodion [a viscous or syrupy solution] negative supported by a dark-lacquered thin iron sheet appears as a positive image." This process, notes the Library, was "Popular [from the] mid-1850s through 1860s" but still "in use through 1930s." (Source: Library of Congress Thesaurus for Graphic Materials, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/tgm0..., accessed 18 April 2012)

The tintype overall is in fair condition, with some chipping of the layer of collodion around the edges and some scratching and aging apparent on the image itself. The section of the image showing the subjects, however, is in fair to good condition, with none of their faces obscured or badly damaged, though some bear scratches.

The image shows two men and two women, dressed formally, and their physical pose, with one of the women touching both men, suggests a comfortable familiarity.

The writing in ink in upper left corner of the image, which presumably identifies the subjects, has faded, but by "tweaking" it in PhotoShop I've been able (tentatively) to discern these words:

Aunt Marie

Uncle Richard

Grandma

Uncle Homer

Bringing out the faded words using PhotoShop. (Click to enlarge)

Bringing out the faded words using PhotoShop. (Click to enlarge)

Of these words, only "Uncle Homer" rings a bell with me, since my great-great grandfather was named Homer Bernard — Homer being pronounced "O-MARE" in the Cajun French manner. I know nothing about him offhand, except that his father, Joseph Desparet Bernard, fought as a Confederate in the Civil War. I have Homer's vital statistics somewhere in my files, however, in genealogical material I collected in high school (an interest that played a major role in directing me toward a career as a historian). I believe Homer would have been from St. Landry Parish, possibly from the town of Opelousas itself, because that is where my Bernard family has lived for many generations.

Incidentally, I find it interesting that all the common nouns written on the photo ("Aunt," "Uncle," "Grandma") are English words, not French. Because my family spoke French as its primary if not only language in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the words must have been added later, after my family adopted English as its primary language — perhaps in the 1920s or '30s. (My grandfather, L. V. Bernard of Opelousas, told me that he did not really learn French until he married my grandmother, Irene Bordelon of Port Barre — indicating that despite his small-town Cajun heritage he was raised speaking English, not French. L.V. would be the grandson of the persons in the photo, if they are in fact Bernard ancestors as Elodie stated.)

I will check if Homer Bernard had a brother named Richard or a sister named Marie, or in-laws with these names. Or could "Aunt Marie" be the wife of "Uncle Homer," and not the wife of "Uncle Richard"? I will report back with my findings.

In the meantime, if anyone knows who these people are (all Cajuns pretty much being related to each other one way or another), please let me know. . . .

Addendum of 18 April 2012

According to my genealogical research — which, admittedly, I am unsure I entirely trust, since I conducted it as a teenager in the 1980s — my great-great-grandfather, Joseph Homer Bernard, was born 6 March 1864 in Opelousas. He had two sisters named Marie — Marie Lelia, born 20 July 1861, and Marie Lydia, born 25 October 1868 — either one of whom could be the "Aunt Marie" in the photograph. Homer did not have a brother named Richard, so perhaps the "Uncle Richard" in the photograph was the husband of one of these two Maries.

Homer himself was married to Louise Alma La Morandiere, who cannot be the other woman in the photo, else the person who wrote on the image would have identified her as "Aunt" (to his "Uncle") and not "Grandma." This other woman in the photo is possibly another of Homer's sisters, either the second Marie or his sister Josephine, born 2 March 1866.

But now I am speculating too much.

Still, if I can prove that one of Homer's three sisters had a husband named Richard, it would go far toward suggesting that the persons in the tintype might indeed be my ancestors.

(My source for this genealogical data is Reverend Donald J. Hebert, Southwest Louisiana Records [Eunice, La.: Hebert Publications, 1978], multiple volumes.)

Here is a photo that my great aunt, the late Elodie Bernard (married name Fontenot), gave me when I visited her around 1980.

The mystery photo.

The mystery photo.(Author's collection)

I remember Aunt Elodie as an elderly, white-haired woman, thin and gaunt. She seemed a stranger to me because, for whatever reason, Elodie never came to family get-togethers, whether for Christmas or Easter or what have you. Only rarely had I heard her name mentioned, and while I have no reason to believe there was any schism that kept her apart from us, it seemed odd to me that the extended family on my father's Cajun side of my family was hardly as close as the extended family on my mother's Anglo-Saxon side of the family. I am by no means making a sweeping implication about Cajuns: on the contrary, Cajuns, if anything, are known for the closeness of their extended families. It just seemed odd that Elodie never showed up at our family gatherings and that I really knew nothing about her, so much so that as a child I barely knew her name, much less what she looked like.

When Aunt Elodie gave me this photo, she explained that it depicted some of our ancestors. She explained to me that it showed my paternal great-great grandparents. It certainly did not show my paternal great-grandparents, for my grandfather's father was the splitting image of his son and I would have recognized him instantly. I recognized no one, however, in this image.

I remain uncertain who is shown in the image and if they are even really my relatives. So I thought I might analyze the photograph and try to determine who these people are.

Often mistakenly called a daguerreotype (including by me), the image is actually a tintype, which the Library of Congress describes as a "Direct-image photograph . . . in which the collodion [a viscous or syrupy solution] negative supported by a dark-lacquered thin iron sheet appears as a positive image." This process, notes the Library, was "Popular [from the] mid-1850s through 1860s" but still "in use through 1930s." (Source: Library of Congress Thesaurus for Graphic Materials, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/tgm0..., accessed 18 April 2012)

The tintype overall is in fair condition, with some chipping of the layer of collodion around the edges and some scratching and aging apparent on the image itself. The section of the image showing the subjects, however, is in fair to good condition, with none of their faces obscured or badly damaged, though some bear scratches.

The image shows two men and two women, dressed formally, and their physical pose, with one of the women touching both men, suggests a comfortable familiarity.

The writing in ink in upper left corner of the image, which presumably identifies the subjects, has faded, but by "tweaking" it in PhotoShop I've been able (tentatively) to discern these words:

Aunt Marie

Uncle Richard

Grandma

Uncle Homer

Bringing out the faded words using PhotoShop. (Click to enlarge)

Bringing out the faded words using PhotoShop. (Click to enlarge)Of these words, only "Uncle Homer" rings a bell with me, since my great-great grandfather was named Homer Bernard — Homer being pronounced "O-MARE" in the Cajun French manner. I know nothing about him offhand, except that his father, Joseph Desparet Bernard, fought as a Confederate in the Civil War. I have Homer's vital statistics somewhere in my files, however, in genealogical material I collected in high school (an interest that played a major role in directing me toward a career as a historian). I believe Homer would have been from St. Landry Parish, possibly from the town of Opelousas itself, because that is where my Bernard family has lived for many generations.

Incidentally, I find it interesting that all the common nouns written on the photo ("Aunt," "Uncle," "Grandma") are English words, not French. Because my family spoke French as its primary if not only language in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the words must have been added later, after my family adopted English as its primary language — perhaps in the 1920s or '30s. (My grandfather, L. V. Bernard of Opelousas, told me that he did not really learn French until he married my grandmother, Irene Bordelon of Port Barre — indicating that despite his small-town Cajun heritage he was raised speaking English, not French. L.V. would be the grandson of the persons in the photo, if they are in fact Bernard ancestors as Elodie stated.)

I will check if Homer Bernard had a brother named Richard or a sister named Marie, or in-laws with these names. Or could "Aunt Marie" be the wife of "Uncle Homer," and not the wife of "Uncle Richard"? I will report back with my findings.

In the meantime, if anyone knows who these people are (all Cajuns pretty much being related to each other one way or another), please let me know. . . .

Addendum of 18 April 2012

According to my genealogical research — which, admittedly, I am unsure I entirely trust, since I conducted it as a teenager in the 1980s — my great-great-grandfather, Joseph Homer Bernard, was born 6 March 1864 in Opelousas. He had two sisters named Marie — Marie Lelia, born 20 July 1861, and Marie Lydia, born 25 October 1868 — either one of whom could be the "Aunt Marie" in the photograph. Homer did not have a brother named Richard, so perhaps the "Uncle Richard" in the photograph was the husband of one of these two Maries.

Homer himself was married to Louise Alma La Morandiere, who cannot be the other woman in the photo, else the person who wrote on the image would have identified her as "Aunt" (to his "Uncle") and not "Grandma." This other woman in the photo is possibly another of Homer's sisters, either the second Marie or his sister Josephine, born 2 March 1866.

But now I am speculating too much.

Still, if I can prove that one of Homer's three sisters had a husband named Richard, it would go far toward suggesting that the persons in the tintype might indeed be my ancestors.

(My source for this genealogical data is Reverend Donald J. Hebert, Southwest Louisiana Records [Eunice, La.: Hebert Publications, 1978], multiple volumes.)

Published on April 18, 2012 11:34

April 11, 2012

The Nike-Cajun Rocket: How It Got Its Name

I promised some time ago that I would discuss the origin of the Nike-Cajun rocket, used as a sounding rocket by the U.S. Air Force, NASA, and other organizations during the Cold War.

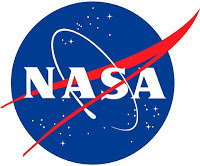

A Nike-Cajun rocket.

A Nike-Cajun rocket.(Source: National Archives and Records Administration.)

As I write in my book, The Cajuns: Americanization of a People :

Cajuns have further demonstrated their ability to adapt to the modern world by pursuing high-tech careers. A few Cajuns, for example, became veritable rocket scientists, among them J. G. Thibodaux [sic].

Born in a lumber camp in the Atchafalaya swamp, he helped to develop the Nike-Cajun rocket in the 1950s, whose second stage, a sounding missile used for testing the upper atmosphere, was named in honor of his ancestry. He went on to serve as chief of the Propulsion and Power Division at Johnson Space Center, assisting NASA with the Apollo moon missions and later with the space shuttle (p. 147).Interviewed in 1999 for the NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project, Thibodaux (full name Joseph Guy Thibodaux, Jr.) described his own origins as follows:

I was born in the Louisiana swamps. . . . I was born at the F.B. Williams Lumber Camp in the Atchafalaya swamp on the west side of Lake Verret. It is certainly a swamp. It was a big cypress logging organization. My father worked there.

My birthplace was registered as Napoleonville, Louisiana[,] which is twelve miles north of Thibodaux, Louisiana[,] on Louisiana Highway 1 which parallels Bayou Lafourche. . . . [W]e left there and moved to New Orleans when I was about five and I went to high school in New Orleans and later on I went to Louisiana State University.(1)Elsewhere, Thibodaux noted, “I consider myself a Cajun[,] both on my mother’s and father’s side.” He added, “My grandmother was an Hebert.”(2)

Logo of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics,

Logo of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics,forerunner of NASA.

Thibodaux graduated from LSU in Chemical Engineering in 1942 and served as a U.S. Army officer from 1943 to 1946, including wartime service in Burma. On separation from the military he went to work for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), forerunner of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), for whom he ultimately worked. Stationed at Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory/Langley Research Center at Langley Field, Virginia, Thibodaux aided NACA first as a propulsion engineer in its Pilotless Aircraft Research Division before moving on to a number of other posts under both NACA and, beginning in 1958, newly created NASA.(3)

Logo of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Logo of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.It was while working for NACA that Thibodaux helped to create the Cajun rocket. Mated to a Nike first-stage rocket, the resulting two-stage rocket was known as the "Nike-Cajun" rocket. As I have observed elsewhere in this blog, "The name evoked a strange combination of ancient Greek mythology and rural south Louisiana folklife."(3)