Sur la Teche: Exploring the Bayou by Canoe, Stage 1

My next book is a history of Bayou Teche (due to be finished next year). As research for this project I resolved to row the entire length of the bayou. I didn’t see how I could not row it. Had I not rowed it, someone, somewhere — at a book signing, during an interview — would inevitably ask, “Have you ever been on Bayou Teche?” to which I would have had to answer, “No — but I live two blocks from it. And I drive across it every day on the way to work.”

The rowers for stage one, at the Courtableau landing.

The rowers for stage one, at the Courtableau landing.

Back row: Jacques, Preston, and me; in front, Keith.

(Click images to enlarge them; photograph by author)

So I decided to explore the entire bayou, and to do so not by motorboat (which seemed like cheating), but the old-fashioned way, by canoe — all approximately one hundred thirty-five miles of it. It just seemed like the right thing to do. And this proved correct, because I found there is no substitute for seeing for oneself, from a boat, where Bayou Courtableau gives rise to the Teche, where Bayou Fuselier cuts over from the Teche toward the Vermilion, where the Teche zigzags at Baldwin and juts out at Irish Bend, running ever closer to its mouth (which actually no longer exists — I’ll explain later).

I would not row the entire bayou at once, however, but in stages over many months. I planned to row slowly, stopping to take photographs and to record GPS coordinates.

Preston and Jacques heading into the Teche from the Courtableau.

Preston and Jacques heading into the Teche from the Courtableau.

(Photograph by author)

I drafted two friends to assist me in the trek, both archaeology graduates from UL-Lafayette: Preston Guidry and Jacques Doucet. Preston’s father, Keith Guidry, made up a last-minute addition to the team; and while Preston and Jacques ended up sitting out several of the stages, Keith became a constant. Preston’s brother, Ben Guidry, filled in for Preston on a couple of stages. Forestry biologist and fellow historical researcher Don Arceneaux joined us for one stage. Together — an Arceneaux, a Doucet, three Guidrys, and a Bernard — we would seek an answer to the profound question, “How many Cajuns does it take to row Bayou Teche?”

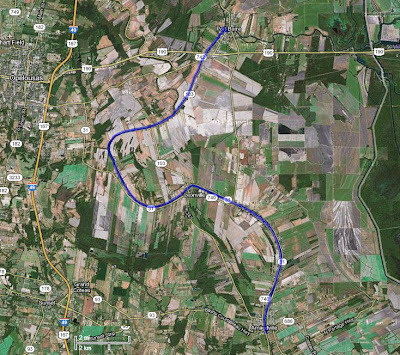

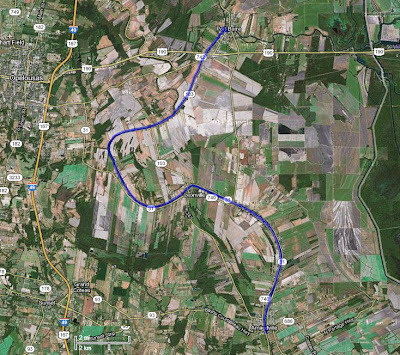

Aerial photograph of Stage 1, Port Barre to Arnaudville.

Aerial photograph of Stage 1, Port Barre to Arnaudville.

(Source: Google Maps)

We began around 9 am on October 23, 2011, by design a week after the annual Tour du Teche canoe race. (We didn’t want to get in the way of the racers, and so let them go first.) We put in at the public boat dock at Port Barre, on the Courtableau about three hundred yards east of the headwaters of the Teche. Within minutes we were rowing on the Teche itself, which is narrow there (varying from about 75 to 95 feet wide, not much larger than a sizable coulee), with dense tree canopies on either side reaching toward the opposite bank and pressing in toward our canoes.

On the Teche near its origin at Port Barre.

On the Teche near its origin at Port Barre.

(Photograph by author)

The current at Port Barre was fairly swift and strong for a bayou — they are usually noted for their slowness — and with our casual rowing it carried our two canoes down the bayou at a decent clip. This fooled us into thinking we would make similarly fast headway the entire length of the bayou; but farther down the current slowed considerably and, eventually, reversed — reducing our progress and making the rowing a more grueling effort. In fact, by the fourth or fifth stage it took us ten or twelve hours to accomplish what we originally did in half that time. But this lesson would not be learned for several more months, undertaking, as we did, a stage every month to month and a half.

The weather that day was cool and the sky mostly clear. Of the group I was the least experienced rower, but Preston, Jacques, and Keith, who rowed often — including in the challenging Atchafalaya swamp — made up for my greenness.

Grazing land along the Teche south of Port Barre.

Grazing land along the Teche south of Port Barre.

(Photograph by author)

Shortly after leaving Port Barre we spotted a coyote running parallel to the bayou on the east bank — the first sign of wildlife on our trip. We soon saw a number of large bones on the west bank, probably cattle. Right before that we had caught the strong scent of cattle dung and must have been passing a ranch (or vacherie, as our ancestors would have called it). At about 10:30 am Keith and I (who rode in the same canoe) stopped beside a bridge to wait for Preston and Jacques. As we floated there, someone up above threw a bottle from the window of a passing car: the bottle burst as it clipped the bridge railing and splashed in the water beside me, still in its anonymous paper bag. Keith found this amusing, and I joked someone had tried to kill me.

Shortly after Preston and Jacques caught up with us they spotted a water moccasin swimming in the bayou; surprisingly, it was the only snake we saw during the many stages of our trip.

An old car along the Teche.

An old car along the Teche.

(Photograph by author)

I noticed much less garbage on the bayou than expected, certainly a tribute to the efforts of Cajuns for Bayou Teche. This group sponsors the Tour du Teche race and uses funds generated from the event to clean up the bayou. The largest quantity of garbage I saw that day lay inside the city limits of Port Barre, where certain persons used the banks of the bayou as private trash heaps. Outside of town, however, the garbage became less frequent. Some it was clearly vintage, which gave it a certain respectability: no one wants to see a new clothes washing machine or recent-model car half-submerged in the bayou or half-buried in its rising banks; but a rusty Depression-era clothes washer or vintage 1950s coupe are more interesting and even somehow appealing in their antiquity.

Another old car along the Teche.

Another old car along the Teche.

(Photograph by author)

Only a few homes lined the Teche between Port Barre and the next bayouside community, Leonville. On the outskirts of Leonville, however, we saw a few suburban-style homes, which removed the illusion of being in wilderness. We reached Leonville at 11:45 am to the sounds of the church carillon. Just south of town, as we headed back into countryside, we spotted a nutria on the bank, scurrying to hide itself from us. Within the hour, just below the Oscar Rivette Bridge, we saw a large owl. Five minutes later we passed under high-voltage transmission lines, whose audible hum and static made me nervous to sit between them and a body of water.

Keith and me (in front) on the Teche.

Keith and me (in front) on the Teche.

(Photograph by Jacques Doucet)

We observed pecan pickers here and there just north of the next community on the bayou, Arnaudville, as well as a large bird I recorded as an “anhinga.” I’m no ornithologist, however, but it looked fairly large and sported dark plumage and black legs — possibly not an anhinga, but a little blue heron. We would see many herons or egrets on our stages, often a single large bird whose solitary hunting we interrupted repeatedly, spurring him farther and farther down the bayou in front of our boats.

View of the Teche from my canoe.

View of the Teche from my canoe.

(Photograph by author)

At 1:45 pm we arrived in Arnaudville, our terminus for this stage of the trip. We pulled ashore at Myron’s Maison de Manger (excellent burgers), right below the junction of the Teche and Bayou Fuselier.

On the other side of the Fuselier once stood the home of my colonial-era ancestor, Lyons-born planter Gabriel Fuselier de la Claire. It’s an extravagant name, but if he had been a big wheel in France I doubt he would have chosen to brave the south Louisiana frontier. With its heat, humidity, mosquitoes, alligators, pirates, and occasional slave or Indian revolts, the French and Spanish colony was no paradise, despite its idealized portrayals in literature. (See Longfellow’s Evangeline.)

Fuselier de la Claire prospered in Louisiana, however, as did his heirs — but somewhere down the line (probably during Reconstruction) the family lost its fortune and ended up marrying into my impoverished clan of subsistence-farming Cajuns. The same happened to the delaMorandieres, deLivaudaises, and other French Creole aristocrats who wound up in my family tree. After a generation or so nothing remained of them culturally, except for my grandmother’s memory that her elderly in-law, the last delaMorandiere of the line, “spoke that fancy French.”

My favorite photo from that day on the Teche, October 2011.

My favorite photo from that day on the Teche, October 2011.

(Photograph by author)

A folksy hand-painted sign hangs beside the bayou near the landing at Myron’s, erected by the local Sons of Confederate Veterans chapter (or “encampment,” as they call it). Erected solely for the benefit of boaters, the sign stated that several steamboats sank at that site during the Civil War.

Sign listing steamboats that sank on that spot during the Civil War.

Sign listing steamboats that sank on that spot during the Civil War.

(Photograph by author)

The Official Records of the conflict indicates that the five vessels had been scuttled by the Rebels to keep them from falling into enemy hands. As a Union officer wrote in April 1863:

Burning steamboats.

Burning steamboats.

(Source: Harper's Weekly [1869])

So who knows how many cannons, shot, belt buckles, bullets, and other Civil War artifacts lay in the mud at the bottom of the bayou, artifacts we paddled over unknowingly as our trip that day came to an end?

After 19 miles of rowing we all were exhausted, but I seemed by far in the worst shape. My arms hurt as though I'd been lifting barbells for too long, and my palms, covered with a metallic sheen from the oars, were sore with blisters. "Next time," I thought, "use gloves." By the time I reached home, I hurt all over: I don't exaggerate when I say I've never felt such excruciating pain in my arms, chest, and back. My bones themselves seemed to ache, right down to the marrow. No matter in what position I sat or lay, I could not make the discomfort go away. This was my penalty for undertaking the trip in poor shape. I swallowed some aspirin and slept horribly, but by morning the pain had disappeared except for vague aching in my upper arms. Fortunately, the pain did not return after future stages. I needed this first stage to break myself in.

The rowers for stage one, at the Courtableau landing.

The rowers for stage one, at the Courtableau landing.Back row: Jacques, Preston, and me; in front, Keith.

(Click images to enlarge them; photograph by author)

So I decided to explore the entire bayou, and to do so not by motorboat (which seemed like cheating), but the old-fashioned way, by canoe — all approximately one hundred thirty-five miles of it. It just seemed like the right thing to do. And this proved correct, because I found there is no substitute for seeing for oneself, from a boat, where Bayou Courtableau gives rise to the Teche, where Bayou Fuselier cuts over from the Teche toward the Vermilion, where the Teche zigzags at Baldwin and juts out at Irish Bend, running ever closer to its mouth (which actually no longer exists — I’ll explain later).

I would not row the entire bayou at once, however, but in stages over many months. I planned to row slowly, stopping to take photographs and to record GPS coordinates.

Preston and Jacques heading into the Teche from the Courtableau.

Preston and Jacques heading into the Teche from the Courtableau.(Photograph by author)

I drafted two friends to assist me in the trek, both archaeology graduates from UL-Lafayette: Preston Guidry and Jacques Doucet. Preston’s father, Keith Guidry, made up a last-minute addition to the team; and while Preston and Jacques ended up sitting out several of the stages, Keith became a constant. Preston’s brother, Ben Guidry, filled in for Preston on a couple of stages. Forestry biologist and fellow historical researcher Don Arceneaux joined us for one stage. Together — an Arceneaux, a Doucet, three Guidrys, and a Bernard — we would seek an answer to the profound question, “How many Cajuns does it take to row Bayou Teche?”

Aerial photograph of Stage 1, Port Barre to Arnaudville.

Aerial photograph of Stage 1, Port Barre to Arnaudville.(Source: Google Maps)

We began around 9 am on October 23, 2011, by design a week after the annual Tour du Teche canoe race. (We didn’t want to get in the way of the racers, and so let them go first.) We put in at the public boat dock at Port Barre, on the Courtableau about three hundred yards east of the headwaters of the Teche. Within minutes we were rowing on the Teche itself, which is narrow there (varying from about 75 to 95 feet wide, not much larger than a sizable coulee), with dense tree canopies on either side reaching toward the opposite bank and pressing in toward our canoes.

On the Teche near its origin at Port Barre.

On the Teche near its origin at Port Barre.(Photograph by author)

The current at Port Barre was fairly swift and strong for a bayou — they are usually noted for their slowness — and with our casual rowing it carried our two canoes down the bayou at a decent clip. This fooled us into thinking we would make similarly fast headway the entire length of the bayou; but farther down the current slowed considerably and, eventually, reversed — reducing our progress and making the rowing a more grueling effort. In fact, by the fourth or fifth stage it took us ten or twelve hours to accomplish what we originally did in half that time. But this lesson would not be learned for several more months, undertaking, as we did, a stage every month to month and a half.

The weather that day was cool and the sky mostly clear. Of the group I was the least experienced rower, but Preston, Jacques, and Keith, who rowed often — including in the challenging Atchafalaya swamp — made up for my greenness.

Grazing land along the Teche south of Port Barre.

Grazing land along the Teche south of Port Barre.(Photograph by author)

Shortly after leaving Port Barre we spotted a coyote running parallel to the bayou on the east bank — the first sign of wildlife on our trip. We soon saw a number of large bones on the west bank, probably cattle. Right before that we had caught the strong scent of cattle dung and must have been passing a ranch (or vacherie, as our ancestors would have called it). At about 10:30 am Keith and I (who rode in the same canoe) stopped beside a bridge to wait for Preston and Jacques. As we floated there, someone up above threw a bottle from the window of a passing car: the bottle burst as it clipped the bridge railing and splashed in the water beside me, still in its anonymous paper bag. Keith found this amusing, and I joked someone had tried to kill me.

Shortly after Preston and Jacques caught up with us they spotted a water moccasin swimming in the bayou; surprisingly, it was the only snake we saw during the many stages of our trip.

An old car along the Teche.

An old car along the Teche.(Photograph by author)

I noticed much less garbage on the bayou than expected, certainly a tribute to the efforts of Cajuns for Bayou Teche. This group sponsors the Tour du Teche race and uses funds generated from the event to clean up the bayou. The largest quantity of garbage I saw that day lay inside the city limits of Port Barre, where certain persons used the banks of the bayou as private trash heaps. Outside of town, however, the garbage became less frequent. Some it was clearly vintage, which gave it a certain respectability: no one wants to see a new clothes washing machine or recent-model car half-submerged in the bayou or half-buried in its rising banks; but a rusty Depression-era clothes washer or vintage 1950s coupe are more interesting and even somehow appealing in their antiquity.

Another old car along the Teche.

Another old car along the Teche.(Photograph by author)

Only a few homes lined the Teche between Port Barre and the next bayouside community, Leonville. On the outskirts of Leonville, however, we saw a few suburban-style homes, which removed the illusion of being in wilderness. We reached Leonville at 11:45 am to the sounds of the church carillon. Just south of town, as we headed back into countryside, we spotted a nutria on the bank, scurrying to hide itself from us. Within the hour, just below the Oscar Rivette Bridge, we saw a large owl. Five minutes later we passed under high-voltage transmission lines, whose audible hum and static made me nervous to sit between them and a body of water.

Keith and me (in front) on the Teche.

Keith and me (in front) on the Teche.(Photograph by Jacques Doucet)

We observed pecan pickers here and there just north of the next community on the bayou, Arnaudville, as well as a large bird I recorded as an “anhinga.” I’m no ornithologist, however, but it looked fairly large and sported dark plumage and black legs — possibly not an anhinga, but a little blue heron. We would see many herons or egrets on our stages, often a single large bird whose solitary hunting we interrupted repeatedly, spurring him farther and farther down the bayou in front of our boats.

View of the Teche from my canoe.

View of the Teche from my canoe.(Photograph by author)

At 1:45 pm we arrived in Arnaudville, our terminus for this stage of the trip. We pulled ashore at Myron’s Maison de Manger (excellent burgers), right below the junction of the Teche and Bayou Fuselier.

On the other side of the Fuselier once stood the home of my colonial-era ancestor, Lyons-born planter Gabriel Fuselier de la Claire. It’s an extravagant name, but if he had been a big wheel in France I doubt he would have chosen to brave the south Louisiana frontier. With its heat, humidity, mosquitoes, alligators, pirates, and occasional slave or Indian revolts, the French and Spanish colony was no paradise, despite its idealized portrayals in literature. (See Longfellow’s Evangeline.)

Fuselier de la Claire prospered in Louisiana, however, as did his heirs — but somewhere down the line (probably during Reconstruction) the family lost its fortune and ended up marrying into my impoverished clan of subsistence-farming Cajuns. The same happened to the delaMorandieres, deLivaudaises, and other French Creole aristocrats who wound up in my family tree. After a generation or so nothing remained of them culturally, except for my grandmother’s memory that her elderly in-law, the last delaMorandiere of the line, “spoke that fancy French.”

My favorite photo from that day on the Teche, October 2011.

My favorite photo from that day on the Teche, October 2011.(Photograph by author)

A folksy hand-painted sign hangs beside the bayou near the landing at Myron’s, erected by the local Sons of Confederate Veterans chapter (or “encampment,” as they call it). Erected solely for the benefit of boaters, the sign stated that several steamboats sank at that site during the Civil War.

Sign listing steamboats that sank on that spot during the Civil War.

Sign listing steamboats that sank on that spot during the Civil War.(Photograph by author)

The Official Records of the conflict indicates that the five vessels had been scuttled by the Rebels to keep them from falling into enemy hands. As a Union officer wrote in April 1863:

I was there [Breaux Bridge] informed that the steamboats Darby, Louise, Blue Hammock, and Uncle Tommy had passed up the bayou the day before — that is, the evening of the 16th instant — . . . having valuable stores belonging to the enemy. . . . I sent forward a man up the Bayou Teche to ascertain the position and condition of the boats. He reported next morning that all of them had been burned at the junction [of bayous Teche and Fuselier] as soon as the enemy learned of the arrival of my command at Breaux Bridge. . . . [At] the junction I examined the wreck of four steamboats. The water having risen after the rains of Saturday night and Sunday morning, 18th and 19th instant, I was unable to see any names on the boats, or the guns reported to have been left on the Darby. Their smoke-stacks and part of their machinery only were above water. From all the information I received I have no doubt of their being the Darby, Louise, Blue Hammock, and the Crocket. The Uncle Tommy is burned higher up in the Bayou Teche, and the wreck of this boat is high enough out of water to see her name. Cargoes of beef, rum, sugar, and commissary stores, cloth, uniforms, and large quantities of arms and ammunition were destroyed in these boats. Some barges took off portions of the cargoes of ammunition and arms from these steamboats before they were set on fire. (Source: The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Volume 15, Part 1 (Baton Rouge-Natchez), 343-44.)

Burning steamboats.

Burning steamboats.(Source: Harper's Weekly [1869])

So who knows how many cannons, shot, belt buckles, bullets, and other Civil War artifacts lay in the mud at the bottom of the bayou, artifacts we paddled over unknowingly as our trip that day came to an end?

After 19 miles of rowing we all were exhausted, but I seemed by far in the worst shape. My arms hurt as though I'd been lifting barbells for too long, and my palms, covered with a metallic sheen from the oars, were sore with blisters. "Next time," I thought, "use gloves." By the time I reached home, I hurt all over: I don't exaggerate when I say I've never felt such excruciating pain in my arms, chest, and back. My bones themselves seemed to ache, right down to the marrow. No matter in what position I sat or lay, I could not make the discomfort go away. This was my penalty for undertaking the trip in poor shape. I swallowed some aspirin and slept horribly, but by morning the pain had disappeared except for vague aching in my upper arms. Fortunately, the pain did not return after future stages. I needed this first stage to break myself in.

Published on October 07, 2012 16:10

No comments have been added yet.