Shane K. Bernard's Blog, page 6

February 12, 2013

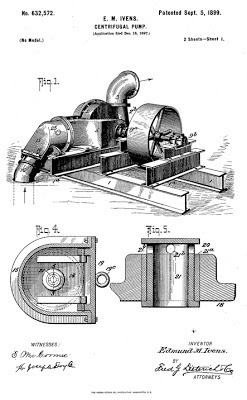

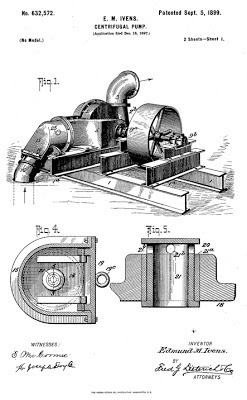

A Film Documents South Louisiana's Logging Industry, ca. 1925: Responsible Stewardship or Environmental Disaster?

Earlier today I learned of a two-part, roughly thirty-minute black-and-white silent film from circa 1925 documenting the daily operations of a south Louisiana cypress company. (I later realized that, purely by coincidence, an old high-school classmate of mine put the digitized film online.)

The movie shows lumberjacks in pirogues (small flat-bottomed boats) cutting down ancient cypress trees in or around the Atchafalaya Basin; a pull boat drawing the logs onto a canal using a chain and windlass; a dredge boat armed with a steam shovel extending the logging canals into a cypress swamp; a locomotive pulling flatcars of logs to the mill; a "towboat" (actually the full-fledged steamboat Sewanee) pulling a "boom" of logs to the mill; "overhead electric cars" — presumably state-of-the-art technology at the time — carrying logs around the lumberyard; "mechanical electric stackers" piling lumber; and early gas-powered trucks pulling wagons of lumber.

The film in question was shot by L. K. Williams, a member of the Williams family of Patterson who operated the massive F. B. Williams Cypress Company, located in that same town on or near the banks of Bayou Teche. The waterway from which L. K. Williams filmed the cypress mill (seen on reel two) is quite possibly the Teche itself, but it's difficult to say because there are many man-made canals around Patterson. The scene in question just as easily could have been shot from one of those canals.

Advertisement for F. B. Williams Cypress Company, Patterson, La.

Advertisement for F. B. Williams Cypress Company, Patterson, La.

(Source: The Lumber Trade Journal, 15 Sept 1914)

Note the industry-specific terms* that appear in the film’s captions: F. B. Williams Cypress Company, Patterson, La.,

F. B. Williams Cypress Company, Patterson, La.,

as shown in the ca. 1925 film.

I cannot find a definition for a run, another term used in the captions, but it is presumably the same as that for gutter road, which is "The path followed in skidding logs" — skid meaning "To draw logs from the stump to the skidway, landing, or mill." In turn, a skidway is "Two skids laid parallel at right angles to a road, usually raised above the ground at the end nearest the road.” The same source adds, "Logs are usually piled upon a skidway as they are brought from the stump for loading upon sleds, wagons, or cars."

This film provides a valuable insight into a now dormant Teche country industry: once lumber mills dotted the lower bayou, drawing on the nearby massive cypress swamp that is the Atchafalaya Basin, as well as on other, smaller cypress swamps in the region. Whether or not this turn-of-the-twentieth-century industry represented responsible stewardship of Louisiana’s natural resources or an environmental disaster (or something in between), I leave to viewers to decide. I myself do not weigh in on the issue because I have not researched the matter, and while it would be easy to deem it an "environmental disaster" I do not know this as a matter of fact.

The steamboat Sewanee, as shown in the ca. 1925 film.

The steamboat Sewanee, as shown in the ca. 1925 film.

It tows a "boom" of logs behind it.

*Definitions are quoted from: Bureau of Forestry, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Terms Used in Forestry and Logging (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1905).

The movie shows lumberjacks in pirogues (small flat-bottomed boats) cutting down ancient cypress trees in or around the Atchafalaya Basin; a pull boat drawing the logs onto a canal using a chain and windlass; a dredge boat armed with a steam shovel extending the logging canals into a cypress swamp; a locomotive pulling flatcars of logs to the mill; a "towboat" (actually the full-fledged steamboat Sewanee) pulling a "boom" of logs to the mill; "overhead electric cars" — presumably state-of-the-art technology at the time — carrying logs around the lumberyard; "mechanical electric stackers" piling lumber; and early gas-powered trucks pulling wagons of lumber.

The film in question was shot by L. K. Williams, a member of the Williams family of Patterson who operated the massive F. B. Williams Cypress Company, located in that same town on or near the banks of Bayou Teche. The waterway from which L. K. Williams filmed the cypress mill (seen on reel two) is quite possibly the Teche itself, but it's difficult to say because there are many man-made canals around Patterson. The scene in question just as easily could have been shot from one of those canals.

Advertisement for F. B. Williams Cypress Company, Patterson, La.

Advertisement for F. B. Williams Cypress Company, Patterson, La.(Source: The Lumber Trade Journal, 15 Sept 1914)

Note the industry-specific terms* that appear in the film’s captions:

Boom, n. Logs or timbers fastened together end to end and used to hold floating logs. The term sometimes includes the logs enclosed, as a boom of logs.

Crib, n. Specifically, a raft of logs; loosely applied to a boom of logs.

Float road[, n.]. A channel cleared in a swamp and used to float cypress logs from the woods to the boom at the river or mill.

F. B. Williams Cypress Company, Patterson, La.,

F. B. Williams Cypress Company, Patterson, La.,as shown in the ca. 1925 film.

I cannot find a definition for a run, another term used in the captions, but it is presumably the same as that for gutter road, which is "The path followed in skidding logs" — skid meaning "To draw logs from the stump to the skidway, landing, or mill." In turn, a skidway is "Two skids laid parallel at right angles to a road, usually raised above the ground at the end nearest the road.” The same source adds, "Logs are usually piled upon a skidway as they are brought from the stump for loading upon sleds, wagons, or cars."

This film provides a valuable insight into a now dormant Teche country industry: once lumber mills dotted the lower bayou, drawing on the nearby massive cypress swamp that is the Atchafalaya Basin, as well as on other, smaller cypress swamps in the region. Whether or not this turn-of-the-twentieth-century industry represented responsible stewardship of Louisiana’s natural resources or an environmental disaster (or something in between), I leave to viewers to decide. I myself do not weigh in on the issue because I have not researched the matter, and while it would be easy to deem it an "environmental disaster" I do not know this as a matter of fact.

The steamboat Sewanee, as shown in the ca. 1925 film.

The steamboat Sewanee, as shown in the ca. 1925 film.It tows a "boom" of logs behind it.

*Definitions are quoted from: Bureau of Forestry, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Terms Used in Forestry and Logging (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1905).

Published on February 12, 2013 14:17

February 4, 2013

A Glimpse from 1968: Historic Films Looked at Cajuns and Creoles in Epic Year

A couple months ago or so Cajun fiddler David Greely sent me a link to a 1968 film on YouTube. The film showed elderly Cajun couples dancing to late Cajun accordionist Aldus Roger (pronounced RO-ZHAY in the French manner).

Aldus Roger and his band perform for dancers.

Aldus Roger and his band perform for dancers.

Source: La Louisiane (1968)

The video captivated me because moving images of Cajun musicians from the late 1960s or earlier are rare. I was not alone in my interest — the video caused a momentary stir among others interested in Cajun culture.

I say "momentary" because almost as soon as David spread the word about this YouTube footage, the original poster suddenly yanked it from the Internet. This is quite possibly my fault, because when I saw the film I immediately e-mailed the original poster to ask, "Where did you get this? Do you know where I can get a copy? It is extremely important to those who study Cajun culture, and I would like to obtain dubs for preservation and research purposes." (I paraphrase.)

Within a few hours the YouTube video was gone and the poster never answered my query. Indeed, with the video removed I had no way to contact the poster, even to ask the name of the film.

Today I decided to see if I could track down the documentary in question. And, by Googling the words "cadien," "documentaire," "musique," and "1968," I was able to find the film.

Logo of the ORTF.

Logo of the ORTF.

Source: Les archives de la télévision

Actually, I found three films (and there are perhaps more), all shot between 1968 and 1969 by the Office de radiodiffusion télévision française(ORTF), operated by the French government.

This was a vital time in Cajun and Creole history. As I note in my book The Cajuns: Americanization of a People : Cover of my book

Cover of my book

The Cajuns: Americanization of a People (2003)

La Louisiane : Fête de l'écrevisse, May 1968 (14 mins. 31 secs.)Source: INA.fr

One of the two films, titled "La Louisiane : Fête de l'écrevisse" ("Louisiana: Crawish Festival"), features the 1968 Breaux Bridge Crawfish Festival. It originally aired in May that year and its summary reads:

A crawfish float on Bayou Teche,

A crawfish float on Bayou Teche,

Breaux Bridge Crawfish Festival.

Source: La Louisiane: Fête de l'écrevisse (1968)

On a less serious note, the film depicts a boat parade on Bayou Teche, a crawfish race, and, in one scene, a van decorated to promote Cajun musician Happy Fats LeBlanc's live Saturday TV program, Mariné, which aired on KLFY-TV 10.

The other film, titled "La Louisiane," was originally released in September 1968 and documents French culture in general in and around Lafayette, Louisiana. It begins with Cajun fishermen in the Gulf of Mexico and, later, includes that priceless footage of Cajun musician Aldus Roger playing for elderly Cajun dancers. It appears to me that the Roger footage was shot at KLFY's studio, originally located on Jefferson Street near its intersection with Pinhook Road. I assume the event is Roger's weekend live Cajun music TV program, which aired on KLFY from the mid-1950s through the 1960s. (I'm unsure when it fell from the station's lineup.) The only reason I doubt we are seeing Roger's weekend program, however, is the inclusion of news in French — unless that was actually part of Roger's program. (The show might be one of KLFY's other long-running local programs, Passe Partoutor Meet Your Neighbor, but I've never heard of either having live studio dancers.)

La Louisiane, September 1968 (15 mins. 2 secs.)Source: INA.fr

Intriguingly, this second film includes an interview in French with future Louisiana governor Edwin Edwards and a rare interview with former U.S. congressman James "Jimmy" Domengeaux (pronounced in the French manner as DUH-MAZH-ZHEE-O, much like the surname of baseball great Joe DiMaggio). (I mention Domengeaux in previous articles here and here.) The same year this documentary appeared, Domengeaux became president of the newly created Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL) — a group that in coming decades would spearhead the teaching of French in Louisiana public schools. It was a revolutionary idea, for less than a decade earlier Louisiana children had been punished in schools for speaking French.

The summary of this film reads: Jimmy Domengeaux interviewed.

Jimmy Domengeaux interviewed.

Source: La Louisiane (1968)

A third film, shot the next year, is available per the INA website, but only as a short preview: it is titled, " Les Enfants de Francien : En Louisiane ," which I suppose could be translated as "The Children of Old French: In Louisiana." It originally aired in June 1969 and according to the summary it asks:

Addendum of 12 February 2013

A third south Louisiana-related film is available for viewing in its entirety through the INA website. Shot in 1976 — eight years after the above two La Louisiane films — it depicts, among other subjects, Louisiana schoolchildren singing "Frère Jacques"; Cajun radio-and-TV personality (and sometimes Cajun singer) Jim Olivier giving a weather forecast in French (another KLFY reference, possibly from the Passe Partout morning program); a second interview with Jimmy Domengeaux (whose group, CODOFIL, is mistakenly called the "Comité du defense du français" — unless a distinct group by this name existed, but I've never heard of it); and a glimpse of Michael Doucet and a few other Cajun musicians performing for the camera. (The musicians may comprise an early version of the band BeauSoleil or perhaps another of Doucet's groups, Coteau.)

Aldus Roger and his band perform for dancers.

Aldus Roger and his band perform for dancers.Source: La Louisiane (1968)

The video captivated me because moving images of Cajun musicians from the late 1960s or earlier are rare. I was not alone in my interest — the video caused a momentary stir among others interested in Cajun culture.

I say "momentary" because almost as soon as David spread the word about this YouTube footage, the original poster suddenly yanked it from the Internet. This is quite possibly my fault, because when I saw the film I immediately e-mailed the original poster to ask, "Where did you get this? Do you know where I can get a copy? It is extremely important to those who study Cajun culture, and I would like to obtain dubs for preservation and research purposes." (I paraphrase.)

Within a few hours the YouTube video was gone and the poster never answered my query. Indeed, with the video removed I had no way to contact the poster, even to ask the name of the film.

Today I decided to see if I could track down the documentary in question. And, by Googling the words "cadien," "documentaire," "musique," and "1968," I was able to find the film.

Logo of the ORTF.

Logo of the ORTF.Source: Les archives de la télévision

Actually, I found three films (and there are perhaps more), all shot between 1968 and 1969 by the Office de radiodiffusion télévision française(ORTF), operated by the French government.

This was a vital time in Cajun and Creole history. As I note in my book The Cajuns: Americanization of a People :

That year, 1968, was remarkable nationally and internationally. The Tet Offensive marked a turning point in the Vietnam War. LBJ announced he would not seek reelection to the presidency. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy were assassinated. Campus rallies erupted into violence amid cries of “Revolution!” Police bullied protestors and innocent bystanders at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. . . .

Acadiana [i.e., Cajun Louisiana] also witnessed incredible events of its own during 1968. Besides the creation of [French education group] CODOFIL, it saw the passage of several laws that bolstered the status of French in Louisiana. The state legislature mandated that public elementary schools offer at least five years of French instruction, and that public high schools offer the subject for at least three years, along with at least one course on the history and culture of French America. It required state colleges and universities to offer teacher certification in elementary school French, and it approved the publication of legal notices and other public documents in French. It also demanded that state-funded educational television be bilingual, showing French programming in equal proportion to its French-speaking viewers. Finally, the legislature authorized the establishment of a non-profit French-language television corporation in conjunction with [local university] USL, to be called Télévision-Louisiane.

Cover of my book

Cover of my book The Cajuns: Americanization of a People (2003)

Other events contributed to making 1968 an astounding year for the French preservation movement. USL committed itself to becoming “a world linguistic center” by establishing an Institute of French Studies and by expanding its role in training French educators. Civic leaders opened cultural exchanges with other French-speaking regions, symbolically pairing Lafayette with the city of Longueuil, Quebec, in what became known as a jumelage (twinning). Business leaders conducted a trade mission to Quebec in order to develop commercial ties. Educators started a summer student exchange program, sending Cajun children to Quebec, and hosting French Canadian children in south Louisiana. An International Acadian Festival took placed in Lafayette, attracting over one hundred governmental and media visitors from Canada and France for two days of receptions, lectures, exhibits, films, tours, and other events that highlighted the region’s French heritage.

Cajuns quickly grasped the significance of this amazing period. “Historians will circle calendar year 1968,” announced Acadiana Profile, a new bilingual magazine, “as the time when the . . . French Renaissance took form and shape and direction in Louisiana.” . . .Shot in 1968, two of the films appeared in a French series called "En Couleur des U.S.A" ("In Color USA"). Both are available for viewing in their entirety per the website of the Institut national de l'audiovisuel (INA), or National Audiovisual Institute, of France.

La Louisiane : Fête de l'écrevisse, May 1968 (14 mins. 31 secs.)Source: INA.fr

One of the two films, titled "La Louisiane : Fête de l'écrevisse" ("Louisiana: Crawish Festival"), features the 1968 Breaux Bridge Crawfish Festival. It originally aired in May that year and its summary reads:

Reportage sur le festival de l'écrevisse à Breaux Bridge, en Louisiane, dans le pays cajun, avec de nombreuses festivités : course d'écrevisses, fanfares, danses, concours d'épluchage d'écrevisses et parades (une pour les blancs et une autre pour les noirs, alors qu'en théorie la ségrégation n'a plus cours).Translation:

Report on the Crawfish Festival of Breaux, Bridge, in Louisiana, in Cajun country, with many festivities: crawfish races, bands, dances, crawfish peeling contests, and parades (one for whites and another for blacks, even though segregation is no longer acceptable).The absence of black people among the festival goers struck me as peculiar, even as the film itself depicts a black parade and a white parade. This was, of course, 1968, about a year before south Louisiana finally integrated its elementary and high schools (despite the fact that fifteen years earlier the Supreme Court, per the case Brown v. the Board of Education, had declared "separate-but-equal" education to be unconstitutional).

A crawfish float on Bayou Teche,

A crawfish float on Bayou Teche,Breaux Bridge Crawfish Festival.

Source: La Louisiane: Fête de l'écrevisse (1968)

On a less serious note, the film depicts a boat parade on Bayou Teche, a crawfish race, and, in one scene, a van decorated to promote Cajun musician Happy Fats LeBlanc's live Saturday TV program, Mariné, which aired on KLFY-TV 10.

The other film, titled "La Louisiane," was originally released in September 1968 and documents French culture in general in and around Lafayette, Louisiana. It begins with Cajun fishermen in the Gulf of Mexico and, later, includes that priceless footage of Cajun musician Aldus Roger playing for elderly Cajun dancers. It appears to me that the Roger footage was shot at KLFY's studio, originally located on Jefferson Street near its intersection with Pinhook Road. I assume the event is Roger's weekend live Cajun music TV program, which aired on KLFY from the mid-1950s through the 1960s. (I'm unsure when it fell from the station's lineup.) The only reason I doubt we are seeing Roger's weekend program, however, is the inclusion of news in French — unless that was actually part of Roger's program. (The show might be one of KLFY's other long-running local programs, Passe Partoutor Meet Your Neighbor, but I've never heard of either having live studio dancers.)

La Louisiane, September 1968 (15 mins. 2 secs.)Source: INA.fr

Intriguingly, this second film includes an interview in French with future Louisiana governor Edwin Edwards and a rare interview with former U.S. congressman James "Jimmy" Domengeaux (pronounced in the French manner as DUH-MAZH-ZHEE-O, much like the surname of baseball great Joe DiMaggio). (I mention Domengeaux in previous articles here and here.) The same year this documentary appeared, Domengeaux became president of the newly created Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL) — a group that in coming decades would spearhead the teaching of French in Louisiana public schools. It was a revolutionary idea, for less than a decade earlier Louisiana children had been punished in schools for speaking French.

The summary of this film reads:

Ce reportage en Louisiane du sud part à la découverte des habitants francophones du pays acadien, dans la région de Lafayette : les trappeurs (piégeurs) des marécages du bayou Vermilion, les pêcheurs de crevettes (descendants de bretons ou normands installés d'abord au Canada) dans le port de Delcambre, les noirs descendants de créoles de Saint Domingue et Haiti. A Lafayette, une chaine de télévision et une station de radio émettent des programmes en français. James Domegeaux (un avocat de Lafayette), un représentant du Congrès et le gouverneur de Louisiane témoignent de leur volonté de sauvegarder le français en Louisiane.Translation:

This report on south Louisiana sets out to discover the French-speaking residents of Acadian country in the Lafayette area: trappers of the wetlands of Bayou Vermilion, shrimp fishermen (descendants of Bretons and Normans who first settled in Canada) at the port of Delcambre, black descendants of Creoles from Santo Domingo and Haiti. In Lafayette, a television station and a radio station broadcast programs in French. James Domegeaux (a lawyer from Lafayette), a congressman [Edwards, who was not yet governor], and a governor of Louisiana [John McKeithen], show their desire to preserve French in Louisiana.

Jimmy Domengeaux interviewed.

Jimmy Domengeaux interviewed.Source: La Louisiane (1968)

A third film, shot the next year, is available per the INA website, but only as a short preview: it is titled, " Les Enfants de Francien : En Louisiane ," which I suppose could be translated as "The Children of Old French: In Louisiana." It originally aired in June 1969 and according to the summary it asks:

Comment peut-on être de culture française sans être français ? Ce reportage présente la communauté acadienne située dans les marais du delta du Mississippi.Translation:

Can French culture exist without being French? This report presents the Acadian community located in the marshes of the Mississippi delta. [I suspect the geography is off slightly.]I re-post these videos because they afford a fascinating glimpse into the state of south Louisiana’s Cajun and Creole culture in the late 1960s, right at the birth of the French revival movement — as perceived at the time by the French media.

Addendum of 12 February 2013

A third south Louisiana-related film is available for viewing in its entirety through the INA website. Shot in 1976 — eight years after the above two La Louisiane films — it depicts, among other subjects, Louisiana schoolchildren singing "Frère Jacques"; Cajun radio-and-TV personality (and sometimes Cajun singer) Jim Olivier giving a weather forecast in French (another KLFY reference, possibly from the Passe Partout morning program); a second interview with Jimmy Domengeaux (whose group, CODOFIL, is mistakenly called the "Comité du defense du français" — unless a distinct group by this name existed, but I've never heard of it); and a glimpse of Michael Doucet and a few other Cajun musicians performing for the camera. (The musicians may comprise an early version of the band BeauSoleil or perhaps another of Doucet's groups, Coteau.)

Published on February 04, 2013 11:43

January 30, 2013

A Snake, a Worm, and a Dead End: In Search of the Meaning of "Teche"

Note: This is a draft. . . .

I recently read about astronomer Johannes Kepler, who spent years forging a theory about the operation of the Solar System — only to admit to himself eventually that the data simply did not support his theory.

Keppler had to throw out his beloved theory.

So I suppose I should not feel too bad about spending the past five days fleshing out a theory about the origin of the word Teche, only to have to toss it after realizing it just didn't stand up to scrutiny.

I ought to explain that in my forthcoming book about the history of Bayou Teche, I grapple with the alleged origins of the word Teche. One of these etymologies — indeed, the one cited most commonly in popular and academic literature — holds that Teche derives from the Chitimacha word for “snake.” The problem with this claim, I observed, is that there is no known Chitimacha word for “snake” that even remotely resembles Teche.

In short, I found this etymology dubious and searched for other explanations. And for the past five days I thought I’d found one — a good one.

Last week I drove to Louisiana State University to visit its Museum of Natural Science. I made the two-hour drive to examine Chitimacha Indian baskets, some of them a century old. All came ultimately from the Chitimachas’ ancestral lands at Charenton, Louisiana (now the Sovereign Nation of the Chitimacha), located about 25 miles southeast of my home.

While scrutinizing the baskets, the museum staff showed me a booklet of handwritten notes by Mrs. Sidney Bradford, née Mary Avery McIlhenny, daughter of Tabasco sauce inventor E. McIlhenny. An avid basket collector, Bradford used the booklet around 1900 to record traditional basket pattern names.

Glancing through the booklet, I noticed under one drawing of a basket pattern she (or a member of the tribe) had written in pencil, “Tesh mich.”

Tesh?

This, of course, is the exact pronunciation of the name of the bayou.

Beneath “Tesh mich” someone had translated the phrase into English: “worm tracks.”

Previously I had been unable to find a Chitimacha word that sounded like Teche. I had consulted Daniel W. Hieber’s Chitimacha-English dictionary (a work in progress accessible here via the Internet), Morris Swadesh’s 1950 Chitimacha-English dictionary, and the published research of noted anthropologist John R. Swanton. But I did so all without success. This confused me, because according to any number of present-day sources, Teche is supposed to mean “snake,” and according to legend the bayou bears this purportedly Chitimacha name because long ago a giant snake created the bayou’s meandering course. As tribal legend maintains:

Yet Bradford had translated Tesh as “worm.” Perhaps, I thought, the word Teche didn’t come from the Chitimacha for “snake”; perhaps it came instead from the Chitimacha for “worm.” A snake and a worm are similar in shape: both are writhing, legless, elongated creatures. Perhaps someone long ago garbled the original story and in translation the worm became a snake?

Swanton’s published writings seemed to support my budding hypothesis. Aware of Bradford’s interest in Chitimacha basketry, Swanton in 1911 wrote of a few specimens she had collected, “All of the designs are tci'cmic, or ‘worm-track’ designs. . . .”

Here, Swanton rendered the Chitimacha word for “worm” not as “tesh,” as Bradford did, but as “tci’c,” and elsewhere “tciic”.

Well, I thought, tci’c and tciic vaguely remind me of Teche.

I further sensed I was on the right track when I read Swanton’s note that “[the letter] c in Chitimacha words used in these [basket] descriptions is pronounced the same as English sh.” In other words, tci’c and tciic were pronounced “tshesh” and “tsheesh”— extremely close to the modern pronunciation of Teche!

I believed I had just about nailed down the origin of Bayou Teche’s name. I had strong evidence, I felt, that the name came from tci’c and tciic, the Chitimacha words for “worm,” which Bradford had rendered as Tesh. Moreover, tradition held that a giant snake had formed the Teche, and does not a worm twist and turn like snake? Could not someone have confused the two creatures when translating the myth into English? And, finally, was not the winding shape of the bayou reflected in the very “worm track” pattern of the Chitimacha baskets?

Then my hypothesis unraveled. Consulting a noted linguist who specializes in Native American languages in the South, I learned that Swanton had used “Americanist phonetic notation” when writing out Chitimacha words. This phonetic system did not correspond to the phonetics learned in elementary schools or used in standard dictionaries. In fact, when Swanton wrote tci’c and tciic, I learned, he meant for them to be pronounced not “tsheesh,” as I thought, but “cheesh”. This, I had to admit, didn’t sound so much like Teche anymore.

Still, I countered, why would Mrs. Bradford (or one of her Chitimacha contacts) have written Tesh in her booklet as the tribal word for “worm”?

I double checked the booklet: Yes, it definitely read Tesh. But as I leafed through the booklet’s other handwritten notes, I saw that the same person who penciled Tesh as Chitimacha for “worm” rendered the word on other pages as chi, chie, chis, and chish. These sounded little like Teche, but very close to “cheesh,” the correct pronunciation.

Indeed, Swadesh, using a different phonetic system when he compiled his Chitimacha dictionary in 1950, wrote the word for “worm” as ǯiːš. When translated into easy-to-read phonetics (for non-linguists like me), ǯiːš would similarly be pronounced “cheesh.”

Moreover, the linguist told me that in the early twentieth century Swanton noted in an unpublished work that the Chitimacha name for the Teche was qukx — a word that sounded nothing like Teche.

In fact, the Chitimacha phrase for “Bayou Teche” was qukx caad.

I already knew the phrase qukx caad. Indeed, it was the very fact that qukx sounded nothing like Teche that caused me to question the popular etymology in the first place. Frankly, I had suspected that qukx caad was a recent folk etymology — that is, I thought perhaps someone, hearing that the Chitimacha had traditionally called the bayou (albeit in their own language) “Snake Bayou,” had consulted a Chitimacha dictionary (perhaps one of those I myself was using), looked up the tribal words for “snake” and “bayou,” and assumed that Chitimachas in earlier times must have used the same words, qukx caad, to indicate Bayou Teche.

Now, however, I knew my hunch was wrong: Swanton’s unpublished work from the early twentieth century proved that the Chitimacha had indeed traditionally called the bayou qukx caad — Snake Bayou.

But — and this is important — if the traditional Chitimacha name for Bayou Teche was qukx caad . . . then where did the word Teche fit into the story?

I was back where I started: qukx and Teche bore no resemblance to each other, either in pronunciation or appearance. So where did the word Teche come from? And if the Chitimacha had not used the term, had it come from the early French or Spanish pioneers and cartographers? And if from them, where did they get it? Perhaps from the Attakapas, or the Houma, or the Choctaw? The latter seemed possible, for other nearby place names derive their names from Choctaw — for example, Atchafalaya and Catahoula.

What if Teche came to the region from the Afro-Caribbean world, I wondered, perhaps even from West Africa itself? Certainly there is precedent in words like yamand gumbo. (See my previous articles about the Afro-Caribbean origin of the word gumbo here and here.)

As I’ve stated previously, I enjoy historical detection. It’s what drew me to my career in history. And while the detective work sometimes pays off, other times it leads nowhere — such as in this instance. But I have another hypothesis, one I won’t discuss here, that remains feasible. And so I fall back on that idea, but will keep looking for alternate explanations for the name of the bayou.

I recently read about astronomer Johannes Kepler, who spent years forging a theory about the operation of the Solar System — only to admit to himself eventually that the data simply did not support his theory.

Keppler had to throw out his beloved theory.

So I suppose I should not feel too bad about spending the past five days fleshing out a theory about the origin of the word Teche, only to have to toss it after realizing it just didn't stand up to scrutiny.

I ought to explain that in my forthcoming book about the history of Bayou Teche, I grapple with the alleged origins of the word Teche. One of these etymologies — indeed, the one cited most commonly in popular and academic literature — holds that Teche derives from the Chitimacha word for “snake.” The problem with this claim, I observed, is that there is no known Chitimacha word for “snake” that even remotely resembles Teche.

In short, I found this etymology dubious and searched for other explanations. And for the past five days I thought I’d found one — a good one.

Last week I drove to Louisiana State University to visit its Museum of Natural Science. I made the two-hour drive to examine Chitimacha Indian baskets, some of them a century old. All came ultimately from the Chitimachas’ ancestral lands at Charenton, Louisiana (now the Sovereign Nation of the Chitimacha), located about 25 miles southeast of my home.

While scrutinizing the baskets, the museum staff showed me a booklet of handwritten notes by Mrs. Sidney Bradford, née Mary Avery McIlhenny, daughter of Tabasco sauce inventor E. McIlhenny. An avid basket collector, Bradford used the booklet around 1900 to record traditional basket pattern names.

Glancing through the booklet, I noticed under one drawing of a basket pattern she (or a member of the tribe) had written in pencil, “Tesh mich.”

Tesh?

This, of course, is the exact pronunciation of the name of the bayou.

Beneath “Tesh mich” someone had translated the phrase into English: “worm tracks.”

Previously I had been unable to find a Chitimacha word that sounded like Teche. I had consulted Daniel W. Hieber’s Chitimacha-English dictionary (a work in progress accessible here via the Internet), Morris Swadesh’s 1950 Chitimacha-English dictionary, and the published research of noted anthropologist John R. Swanton. But I did so all without success. This confused me, because according to any number of present-day sources, Teche is supposed to mean “snake,” and according to legend the bayou bears this purportedly Chitimacha name because long ago a giant snake created the bayou’s meandering course. As tribal legend maintains:

Many years ago . . . there was a huge and venomous snake. This snake was so large, and so long, that its size was not measured in feet, but in miles. This enormous snake had been an enemy of the Chitimacha for many years, because of its destruction to many of their ways of life. One day, the Chitimacha chief called together his warriors, and had them prepare themselves for a battle with their enemy. In those days, there were no guns that could be used to kill this snake. All they had were clubs and bows and arrows, with arrowheads made of large bones from the garfish. . . . The warriors fought courageously to kill the enemy, but the snake fought just as hard to survive. As the beast turned and twisted in the last few days of a slow death, it broadened, curved and deepened the place wherein his huge body lay. The Bayou Teche is proof of the exact position into which this enemy placed himself when overcome by the Chitimacha warriors. (Source: Chitimacha.gov)

Yet Bradford had translated Tesh as “worm.” Perhaps, I thought, the word Teche didn’t come from the Chitimacha for “snake”; perhaps it came instead from the Chitimacha for “worm.” A snake and a worm are similar in shape: both are writhing, legless, elongated creatures. Perhaps someone long ago garbled the original story and in translation the worm became a snake?

Swanton’s published writings seemed to support my budding hypothesis. Aware of Bradford’s interest in Chitimacha basketry, Swanton in 1911 wrote of a few specimens she had collected, “All of the designs are tci'cmic, or ‘worm-track’ designs. . . .”

Here, Swanton rendered the Chitimacha word for “worm” not as “tesh,” as Bradford did, but as “tci’c,” and elsewhere “tciic”.

Well, I thought, tci’c and tciic vaguely remind me of Teche.

I further sensed I was on the right track when I read Swanton’s note that “[the letter] c in Chitimacha words used in these [basket] descriptions is pronounced the same as English sh.” In other words, tci’c and tciic were pronounced “tshesh” and “tsheesh”— extremely close to the modern pronunciation of Teche!

I believed I had just about nailed down the origin of Bayou Teche’s name. I had strong evidence, I felt, that the name came from tci’c and tciic, the Chitimacha words for “worm,” which Bradford had rendered as Tesh. Moreover, tradition held that a giant snake had formed the Teche, and does not a worm twist and turn like snake? Could not someone have confused the two creatures when translating the myth into English? And, finally, was not the winding shape of the bayou reflected in the very “worm track” pattern of the Chitimacha baskets?

Then my hypothesis unraveled. Consulting a noted linguist who specializes in Native American languages in the South, I learned that Swanton had used “Americanist phonetic notation” when writing out Chitimacha words. This phonetic system did not correspond to the phonetics learned in elementary schools or used in standard dictionaries. In fact, when Swanton wrote tci’c and tciic, I learned, he meant for them to be pronounced not “tsheesh,” as I thought, but “cheesh”. This, I had to admit, didn’t sound so much like Teche anymore.

Still, I countered, why would Mrs. Bradford (or one of her Chitimacha contacts) have written Tesh in her booklet as the tribal word for “worm”?

I double checked the booklet: Yes, it definitely read Tesh. But as I leafed through the booklet’s other handwritten notes, I saw that the same person who penciled Tesh as Chitimacha for “worm” rendered the word on other pages as chi, chie, chis, and chish. These sounded little like Teche, but very close to “cheesh,” the correct pronunciation.

Indeed, Swadesh, using a different phonetic system when he compiled his Chitimacha dictionary in 1950, wrote the word for “worm” as ǯiːš. When translated into easy-to-read phonetics (for non-linguists like me), ǯiːš would similarly be pronounced “cheesh.”

Moreover, the linguist told me that in the early twentieth century Swanton noted in an unpublished work that the Chitimacha name for the Teche was qukx — a word that sounded nothing like Teche.

In fact, the Chitimacha phrase for “Bayou Teche” was qukx caad.

I already knew the phrase qukx caad. Indeed, it was the very fact that qukx sounded nothing like Teche that caused me to question the popular etymology in the first place. Frankly, I had suspected that qukx caad was a recent folk etymology — that is, I thought perhaps someone, hearing that the Chitimacha had traditionally called the bayou (albeit in their own language) “Snake Bayou,” had consulted a Chitimacha dictionary (perhaps one of those I myself was using), looked up the tribal words for “snake” and “bayou,” and assumed that Chitimachas in earlier times must have used the same words, qukx caad, to indicate Bayou Teche.

Now, however, I knew my hunch was wrong: Swanton’s unpublished work from the early twentieth century proved that the Chitimacha had indeed traditionally called the bayou qukx caad — Snake Bayou.

But — and this is important — if the traditional Chitimacha name for Bayou Teche was qukx caad . . . then where did the word Teche fit into the story?

I was back where I started: qukx and Teche bore no resemblance to each other, either in pronunciation or appearance. So where did the word Teche come from? And if the Chitimacha had not used the term, had it come from the early French or Spanish pioneers and cartographers? And if from them, where did they get it? Perhaps from the Attakapas, or the Houma, or the Choctaw? The latter seemed possible, for other nearby place names derive their names from Choctaw — for example, Atchafalaya and Catahoula.

What if Teche came to the region from the Afro-Caribbean world, I wondered, perhaps even from West Africa itself? Certainly there is precedent in words like yamand gumbo. (See my previous articles about the Afro-Caribbean origin of the word gumbo here and here.)

As I’ve stated previously, I enjoy historical detection. It’s what drew me to my career in history. And while the detective work sometimes pays off, other times it leads nowhere — such as in this instance. But I have another hypothesis, one I won’t discuss here, that remains feasible. And so I fall back on that idea, but will keep looking for alternate explanations for the name of the bayou.

Published on January 30, 2013 20:06

January 10, 2013

Galaxies, Bowling and Swamp Pop: Johnny Preston and The Cajuns in Escondido

This is so trivial a matter I'm unsure why I wrote it up . . . but I did. And so here you have it:

A friend of mine sent me a link to one of those "remember-the-days?" websites that feature images of a younger America. This particular collection of photographs focused on gas stations across the country from the 1920s through the 1960s. You can see the site for yourself here.

One of the images captured a California gas station and what I believe to be a 1962 Ford Galaxie at the pump. (Correct me if I'm wrong about the make or model — I originally thought it was a 1960 Chevy Impala.)

Filling up next to the Escondido Bowl.

Filling up next to the Escondido Bowl.Behind the car stands a sign for a bowling alley, restaurant, and coffee shop called the Escondido Bowl. Thus, judging from this sign and the Galaxie — as well as from the other cars in the image — the photograph was taken in Escondido, California (located below Los Angeles near San Diego), in or shortly after 1962.

What really caught my eye, however, was the marquee below the Escondido Bowl signage. It read:

Johnny PrestonThe Cajuns

See? "Johnny Preston" and "The Cajuns."

See? "Johnny Preston" and "The Cajuns."For those who don't know, Johnny Preston had an international number one hit single in 1959 with the song, "Running Bear," written by J. P. Richardson (aka The Big Bopper, who died in the same plane crash that killed Buddy Holly).

Johnnie Preston singing "Running Bear."(Source: NRRArchives on YouTube.com)

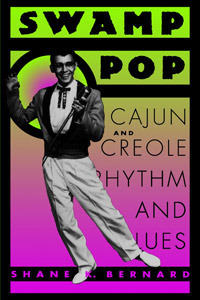

In 1996 I published my first book, Swamp Pop: Cajun and Creole Rhythm and Blues, about the swamp pop musical genre of south Louisiana and east Texas. Swamp pop is a combination of New Orleans-style rhythm-and-blues, country-and-western, and Cajun and black Creole music. It was invented by Cajun and black Creole teenagers in the mid- to late 1950s, and its heyday stretched from 1958 to 1964, ending with the advent of the British Invasion.

Cover of my book Swamp Pop.

Cover of my book Swamp Pop.Among the pioneer swamp pop musicians I interviewed for the book was Johnny Preston — real name Johnny Preston Courville. As his tell-tale ethnic surname suggests, he was a Cajun, hailing from the Beaumont-Port Arthur area of east Texas (to which many south Louisiana Cajuns migrated during the early to mid-twentieth century). I assumed "The Cajuns" was the name of Preston's band — though I'd never heard of him fronting a band by this name.

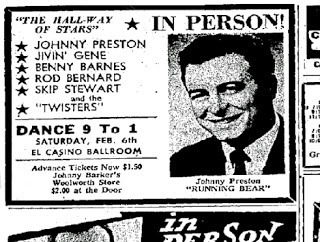

I told my father, swamp pop musician Rod Bernard, about Johnny’s name appearing on the marquee. He replied, "Well, I toured with Johnny on the West Coast around that time. A bunch of us from around here toured with him out west."

Newspaper ad for a 1960 tour out west featuring Dad,

Newspaper ad for a 1960 tour out west featuring Dad,Johnny Preston, Jivin' Gene, Benny Barnes, and Skip Stewart.

(Source: Tucson Daily Citizen, 30 January 1960)

Dad and I suddenly had the same thought: What if he had been there, with Johnny, at the Escondido Bowl when the photograph in question had been taken? Perhaps "The Cajuns" referred to the other singers in the tour group, all but one of whom, Benny Barnes, were indeed Cajuns? The other singers were Dad, Jivin’ Gene (real name Gene Bourgeois) and Skip Stewart (Maurice Guillory); Dad’s band, The Twisters — some of whose members were Cajuns — served as the backing band for the tour group.

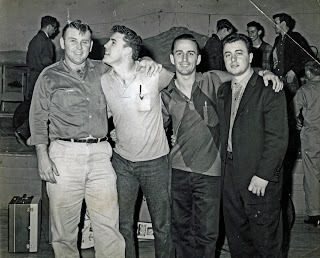

Left to right, Benny Barnes, Jivin' Gene,

Left to right, Benny Barnes, Jivin' Gene, Dad, and Johnny Preston, ca. 1960.

(Source: Author's Collection)

I checked a few online newspaper archives and found that Johnny Preston toured the West Coast, including the Escondido area, with a band called "The Cajuns" in 1964 and 1965 — a few years after he toured the West Coast with Dad and the other swamp pop artists. In other words, Dad was not with Johnny when the gas station photograph was taken. Not that it matters. Still, it would have been a neat coincidence. In any event, the gas station photograph captures a moment in time when swamp pop music was young and often performed by its pioneers far beyond its homeland. Swamp pop still exists today, but its pioneers are slowly passing away, and the genre is largely confined to the dance halls and honky tonks of south Louisiana and East Texas.

Addendum: In retrospect I think I wrote this as nothing more than an exercise in historical detection (which I enjoy).

Published on January 10, 2013 10:28

November 25, 2012

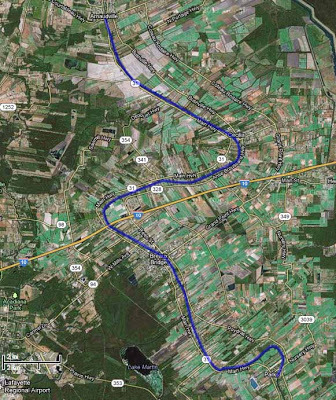

Sur le Teche: Exploring the Bayou by Canoe, Stage 3

Continued from Part II:

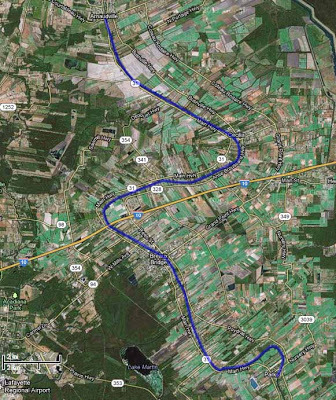

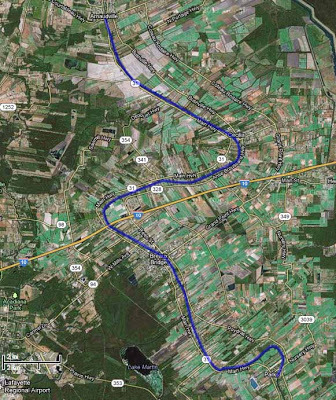

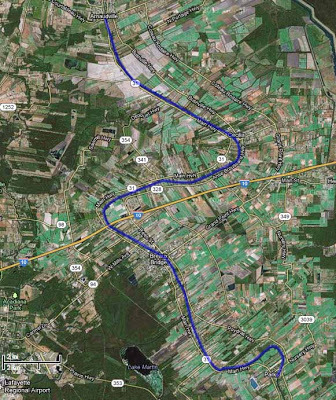

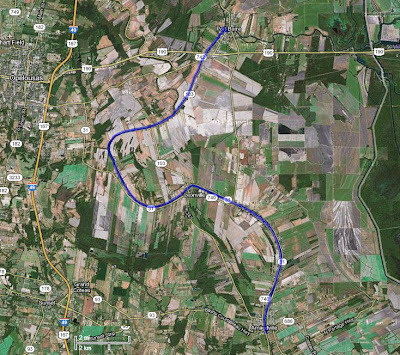

The third leg of our Teche trip took place on December 3, 2011, and stretched between the towns of Parks and Loreauville. The temperature that day was 55 °F in the morning, 81 °F in the afternoon; the sky was partly cloudy. Present, as always, were Keith Guidry and myself. On this particular stage, however, we were accompanied by Don Arceneaux, who shared our interest in the bayou and its history. Don would follow us in his small one-man kayak.

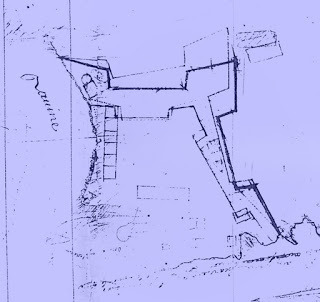

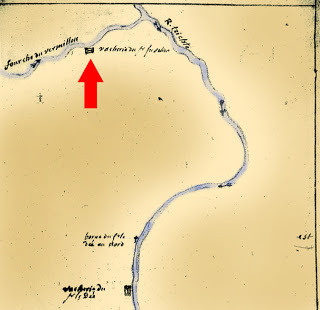

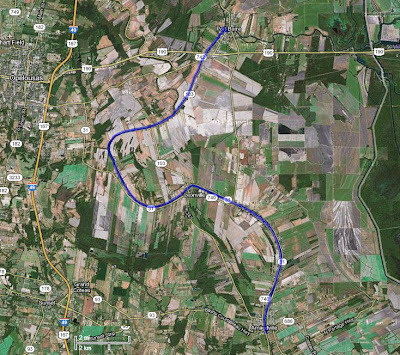

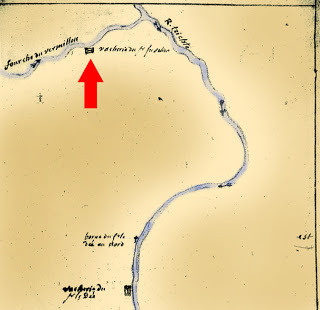

Aerial photograph of Stage 3, Parks to Loreauville.

Aerial photograph of Stage 3, Parks to Loreauville.

(Source: Google Maps)

We put in at 9 a.m. at Cecile Rousseau Memorial Park [30.214696, -91.82829] in Parks. Passing many modern houses along the Teche, we soon reached the community of Levert-St. John [30.158533, -91.812519], the first sugar plantation we encountered (to my knowledge) since starting our trip at Port Barre months earlier. As The Louisiana Planter and Sugar Manufacturer noted in 1890:

Approaching the Levert-St. John sugar refinery near St. Martinville.

Approaching the Levert-St. John sugar refinery near St. Martinville.

(Photo by author)

St. John Plantation, now organized under the modern corporate name Levert-St. John, LLC, is owned by the Levert Companies. As the company’s website notes, “The principal asset of this company [Levert-St. John] is agricultural land (approximately 11,000 total acres), all in St. Martin Parish, Louisiana. The Levert-St. John, LLC lands are made up primarily of four plantations, St. John, Banker, Burton and Stella, all in St. Martin Parish.” Of that 11,000 acres, approximately 75% is dedicated to sugar production, the remainder focusing on rice and crawfish production.

Levert-St. John sugar refinery on Bayou Teche.

Levert-St. John sugar refinery on Bayou Teche.

(Photo by author)

The sugar refinery at Levert-St. John dominates the surrounding flat sugarcane fields. We were fortunate to canoe past the structure at the height of grinding season (which runs from October to January), when the complex belches enormous clouds of steam into the winter sky. At any given time sugar mills either smell pleasantly sweet, like molasses, or they emit a god-awful stench, to which nothing of a polite nature compares. Levert-St. John must have smelled sweet that day, because I made no reference to the odor in my journal, and I believe I would have remembered the alternative.

In addition to the hissing, breathing refinery, we saw here the 264-foot-long, 14.7-foot-wide Levert-St. John Bridge, which appears on the National Register of Historic Places (site #98000268, added 1998). A double Warren truss swing bridge made of rusted steel girders, it was constructed in 1895 for railroad and pedestrian traffic. Eventually, however, the rails were covered with asphalt to form a single-lane bridge for automobiles (which I remember driving across in the 1980s — not the most secure experience). According to a study conducted for its National Register candidacy, the Levert-St. John Bridge is “the oldest known [extant] bridge in Louisiana, as well as the only known bridge of its type in the state. . . .”

The now defunct Levert-St. John Bridge.

The now defunct Levert-St. John Bridge.

The year "1895" is cut into the steel plate above the opening.

(Click to enlarge; photo by author)

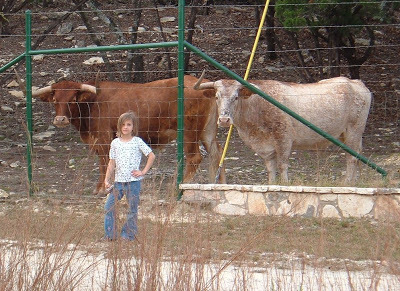

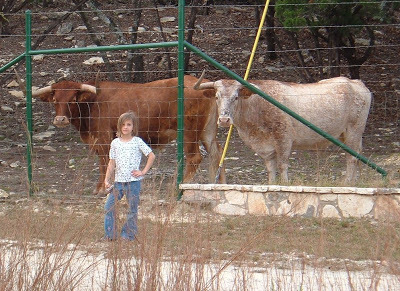

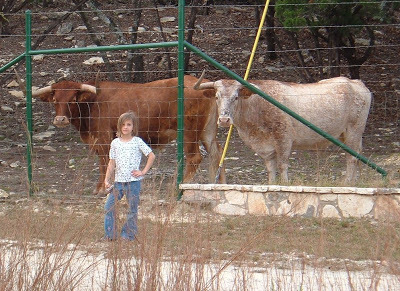

After paddling around and even under the bridge, Keith, Don, and I continued on toward St. Martinville. On the outskirts of town we reached the Longfellow-Evangeline State Historic Site [30.135863, -91.819224](more on Longfellow and Evangeline below), the centerpiece of which is Maison Olivier, a “Raised Creole Cottage . . . which shows a mixture of Creole, Caribbean, and French influences.” The home was built circa 1815 by French Creole planter Pierre Olivier Duclozel de Vezin, from whom two of my occasional canoeing partners, Preston Guidry and his brother Ben, trace direct lineage. I could not see the cottage from the bayou, but I did see Spanish longhorn cattle — a fitting living history display, because Spanish longhorn was indeed the variety of cattle raised in Louisiana during its colonial period (1699-1803). This variety is no longer seen in south Louisiana — at least not from my experience — although Texas longhorns still inhabit parts of that state, I having seen them for myself in the Hill Country.

My daughter flanked by two longhorns in Texas.

My daughter flanked by two longhorns in Texas.

(Photo by author)

Immediately south of Longfellow-Evangeline, and just beside St. Martinville Senior High School (from which, by the way, Preston and Ben graduated), one can see, behind a low dam, the Cypress Bayou Coulee Canal [30.131748, -91.822636] running northwest into Bayou Tortue Swamp. A major wetlands area, Bayou Tortue Swamp begins on the north near Breaux Bridge and stretches to the Terrace Highway (Highway 96) on the south, and from the natural Teche levee on the east to an area abutting the Lafayette Regional Airport on the west. (It’s funny how I grew up in Lafayette never knowing such a large swamp existed nearby. Granted, I knew Lake Martin, but I had no idea it was part of a much larger swamp ecosystem.)

The cement boat at St. Martinville.

The cement boat at St. Martinville.

(Photo by author)

As we neared downtown St. Martinville, Keith showed me two peculiar landmarks. One of these is a boat made of cement, now dilapidated and slowly sinking into the bayou. Cement boats, it turns out, are not unheard of. The other landmark is the site of a small cave [30.124257, -91.826246] in which local children used to play. Infinitely smaller than the one in which Tom Sawyer and Becky Thatcher became lost, the cave entrance has now been sealed with cement for reasons of safety; but you can see the cement patch over the cave’s entrance, about a hundred yards from the downtown bridge over the Teche. Preston once shoved a paddle into a crack in the cement, and the paddle went in all the way to the grip — a good five feet or so. (Decades ago I explored a similar cave in a bluff of the Vermilion River, just south of the bridge over which E. Broussard Road [Highway 733] crosses that bayou. There was not much to the cave: its pale clay walls extended into the bluff about ten or twelve feet before ending in a small hole in the ceiling, which in turn opened onto a pasture.)

Cement now covers the cave entrance.

Cement now covers the cave entrance.

(Photo by author)

From the bayou at St. Martinville we saw St. Martin de Tours Catholic Church, the Acadian Memorial, the Museum of the Acadian Memorial, the adjacent African-American Museum, the Old Castillo Hotel (about which I’ve written previously) and the Evangeline Oak [30.121953, -91.827244], under which the Acadian maiden Evangeline went insane pining for her lost love Gabriel . . . well, that is how I heard the story.

American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow mentions St. Martinville in his epic poem Evangeline, first published in 1847:

In his book In Search of Evangeline, historian Carl A. Brasseaux has demonstrated that Evangeline never existed; nor did Emmeline Labiche, an Acadian exile on whom Longfellow supposedly based the character of Evangeline. Thus, neither Evangeline nor Emmeline are buried in “Evangeline’s Tomb” next to St. Martin de Tours. Yet the events against which Longfellow set the tragedy of Evangeline — the brutal mid-eighteenth-century expulsion of the Acadians from Nova Scotia by the British military — are factual, as is the settlement of many Acadian exiles in the St. Martinville area (among them my own ancestors, including Michel Bernard, who arrived in 1765 with

Evangeline.

Evangeline.

(Artist: Frank Dicksee, 1882)

According to various sources, St. Martinville was known in olden times as “le petit Paris” because of its lavish social life — a story I’ve always regarded with some skepticism. Occupied by a church since the 1770s, the place, known as the Poste des Attakapas (a term that often referred to the region and not a specific locale), amounted to little until the early nineteenth century. At that time, however, local landowners divided their property into lots; sold or rented these parcels to settlers; and called the resulting community “St. Martinsville” after the local church’s patron saint. Thus, there seems to have been little time for St. Martinville to have flourished as a “little Paris” before the onslaught of tough economic times during and after the Civil War. The “petit Paris” claim, however, can be traced back as far as 1884, when (oddly enough) The Irish Monthly magazine of Dublin reported, “Before the war, which was peculiarly disastrous in its effects on this town, St. Martin’s used to be called Le petit Paris and was perhaps the most aristocratic place in Louisiana. But now many of its houses look old and dilapidated, and few traces of the little Paris remain.” (Source: Anonymous, “From Acadie to Attakapas: The Wanderings of Evangeline,” The Irish Monthly 12 [1884], p. 179.)

"Evangeline's Tomb," St. Martinville, Louisiana.

"Evangeline's Tomb," St. Martinville, Louisiana.

(Photo by author)

Brasseaux shares my skepticism, however, observing,

Cover of Brasseaux's French, Cajun, Creole, Houma (2005).

Cover of Brasseaux's French, Cajun, Creole, Houma (2005).

As we left St. Martinville and paddled into the countryside, I spotted a few ibises on a mud flat, pecking away at minnows. As a historian I found this of interest because the ibis, with its distinctive downturned beak, is strongly linked to ancient Egypt. There religious mythology associated the ibis with Thoth, the ibis-headed god of wisdom and writing. The “father of history,” Herodotus, recorded of ancient Egypt, “When a man has killed one of the sacred animals, if he did it with malice . . . he is punished with death; if unwittingly, he has to pay such a fine as the priests choose to impose. When an ibis, however, or a hawk is killed, whether it was done by accident or on purpose, the man must needs die [my italics].” The ibises we saw that day were young white ibises whose plumage had not yet turned completely white.

A pair of ibises along the Teche below St. Martinville.

A pair of ibises along the Teche below St. Martinville.

(Photo by author)

A little after 1 p.m. we spotted the Keystone Lock and Dam [30.071095, -91.828859], for all practical purposes a convenient line of demarcation between the upper and lower Teche. Between the dam and us floated numerous islands of water hyacinth, one of them, the largest, measuring about 75 feet in length. Since starting our trip at Port Barre, we have worried about hyacinth. An invasive species, we feared it would at some point block our progress, clogging the entire bayou from one bank to the other. Those we now saw represented the largest concentration we had yet encountered, but it was not enough to stop us; we merely paddled around the aquatic plants or sometimes plowed straight through them, feeling the drag on the bottom of the canoe. Aerial photographs showed even denser masses of water hyacinth ahead of us, near Baldwin and Franklin. But we would not reach those towns on the current stage.

A raft of water hyacinths floating on the Teche.

A raft of water hyacinths floating on the Teche.

The Keystone Lock and Dam are in the distance.

(Photo by author)

As we closed in on the dam, the sound of water topping the cement structure became louder. Here we had no choice but to do a portage. I don’t know how people pronounce “portage” elsewhere in the country, but in south Louisiana the most common pronunciation I hear is the French pronunciation, which is POR-TAHZH. What is perplexing, however, is that the French place name Fausse Pointe — an archaic name for our stopping point that day, Loreauville, as well as for a stretch of the Teche near New Iberia, and now the name of a nearby lake and state park — is almost universally pronounced (that is, arguably mispronounced), even by Cajuns who know the local patois, as FAW-SEE POINT instead of FAHS POINT. This Anglicized pronunciation jars me, just as the English pronunciation of portage jars me.

We went ashore here to make a portage.

We went ashore here to make a portage.

(Photo by author)

So we made a portage, hauling our canoe and Don’s kayak up a steep embankment on the east side of the Teche, carrying the boats about a hundred yards along a trail through a patch of woods, lowering them down another embankment (much steeper than the first), and putting them back into the water just below the lock and dam. The Tour du Teche race organizers had sunk some 4x4 posts in this last embankment and, evidently running ropes between the posts, had rigged up a method for lowering canoes into the bayou. Unfortunately, no ropes were present on our visit, so we had to make do without this convenience. (Were we trespassing here? It was unclear: We exited the bayou on federal property, but at some point may have entered private property. I say this because just before we lowered our canoes back into the water we spotted a “Private Property” sign — but, confusingly, it was facing the wrong direction, so that canoers could not see the sign until after the fact. In any event, canoers cannot pass the dam and lock without making a portage, and as a result the location offers itself as a legitimate candidate for right of way. But I leave this matter for others to solve.)

Keystone Lock and Dam from downstream.

Keystone Lock and Dam from downstream.

(Photo by author)

Once back in the water, we continued to paddle downstream, noting juglines on the bayou and beaver gnaw marks on tree trunks. We passed the entrance to the Joe Daigre Canal [30.064878, -91.826166], which runs a short distance to Bayou Tortue. In turn, that bayou wraps itself around the northern bank of Spanish Lake before entering Bayou Tortue Swamp.

Don Arceneaux in his kayak.

Don Arceneaux in his kayak.

(Photo by author)

At 2:50 p.m. we reached Daspit Bridge [30.040546, -91.800843], and it was around this time that we noticed a sweet molasses smell — another sugar refinery in operation. We passed many modern suburban houses on the east bank and at 3:20 p.m. I spotted a wall of green in front of us — What was it? I wondered. A painted green wall, perhaps the side of a large barn? It seemed to rise two stories or more. I realized it was a grassy hill rising above the bayou's bluff. (An archaeology friend later suggested the hill as a likely candidate for an Indian mound.) “What is this place?” I asked Don, who, it turned out, knew precisely what it was. He’d scouted ahead, putting his kayak in near Daspit Bridge a few days earlier. Now he was toying with me, awaiting my reaction to the grassy hill, below which a coulee or small bayou entered the Teche.

It was the mouth of Bayou La Chute [30.03667, -91.786284] and the site of the eighteenth-century waterfall that emptied into the Teche.

Entrance to Bayou La Chute (center) as seen from the Teche.

Entrance to Bayou La Chute (center) as seen from the Teche.

The grassy hill at right appears much higher from a distance.

(Photo by author)

Don had identified this site as the probable location of the waterfall — it just made sense, topographically. Additional research on my part revealed that locals called this small tributary Bayou La Chute . . . and “La Chute” in French means “the waterfall.” (See my detailed article on our search for the waterfall’s site.) There is no waterfall today, its ten-foot drop, made of dirt or clay, having eroded away, or been removed by human activity.

A paddle up Bayou La Chute is worth the effort. Although modern neighborhoods encroach on more than one side (including a neighborhood under construction), I found Bayou La Chute in some ways more beautiful than the Teche. In its dark swampiness I half expected to see Yoda, and because of its winding narrowness, lined with bamboo (a nonindigenous plant no doubt loosed from someone’s garden), it reminded me of an amusement park jungle ride.

On Bayou La Chute; for scale, note fishing chair on left bank.

On Bayou La Chute; for scale, note fishing chair on left bank.

(Photo by author)

We stopped at a fork in Bayou La Chute, and made our way back to the Teche to continue toward Loreauville. With the sun sinking and the sky dimming, we had one more discovery to make that day, the so-called “tombs” [30.062517, -91.769417] I mentioned in one of my previous articles. I no longer think these are tombs, but, rather, pilings belonging to a nineteenth-century sugar mill or steam pump. Indeed, we were now in sugar country, passing through one old sugar plantation after another — some now transformed into neighborhoods, some still producing sugar, but, of course, without the slaves who once carried out the grueling tasks associated with making sugar — cutting cane by hand, hauling it to the sugar house, feeding it into the rollers, boiling the saccharine juice, refining it again and again until, at the exact moment, a “strike” was poured, and if all went well creating granulated brown sugar seeped with molasses. Loaded into oversized barrels called hogsheads, the commodity traveled via Teche steamboats to New Orleans, where it would be sold on the local market, or transferred to schooners for sale on the East Coast market.

"Tombs" on the Teche.

"Tombs" on the Teche.

I now believe these are old industrial pilings.

(Photo by author)

On the outskirts of Loreauville we saw three immense boat-building facilities and a couple of vessels associated with the petroleum industry — a living quarters boat and a jack-up boat. These sights reminded us that although we paddled inland on a bayou whose mouth did not empty into open water (the Teche originally poured into the Lower Atchafalaya River, but now diverts into the Calumet Cut, known less poetically as the Wax Lake Outlet), we were nonetheless not that far from the Gulf of Mexico.

A typical scene on the Teche that day.

A typical scene on the Teche that day.

(Photo by author)

Modern homes and businesses ran along the bayou at Loreauville. We drew up to our designated landing, the town’s bridge [30.056791, -91.740185], which stands next to a volunteer fire station and an old jailhouse. We debarked and hauled the canoe and kayak up a high bluff below the jailhouse. Don had an easier time with his small kayak, but Keith and I struggled with the 17-foot metal canoe. Wrestling with the boat, the two of us suffered simultaneous asthma attacks — a humorous coincidence, but only in retrospect. Fortunately, we each brought an inhaler, and soon we were enjoying hamburgers at the nearby (and aptly named) Teche Inn, located a block or two from the bayou. Distance covered that day: 19.15 miles.

The old Loreauville jail on the banks of the Teche.

The old Loreauville jail on the banks of the Teche.

(Photo by author)

Continued in Part IV. . . .

The third leg of our Teche trip took place on December 3, 2011, and stretched between the towns of Parks and Loreauville. The temperature that day was 55 °F in the morning, 81 °F in the afternoon; the sky was partly cloudy. Present, as always, were Keith Guidry and myself. On this particular stage, however, we were accompanied by Don Arceneaux, who shared our interest in the bayou and its history. Don would follow us in his small one-man kayak.

Aerial photograph of Stage 3, Parks to Loreauville.

Aerial photograph of Stage 3, Parks to Loreauville.(Source: Google Maps)

We put in at 9 a.m. at Cecile Rousseau Memorial Park [30.214696, -91.82829] in Parks. Passing many modern houses along the Teche, we soon reached the community of Levert-St. John [30.158533, -91.812519], the first sugar plantation we encountered (to my knowledge) since starting our trip at Port Barre months earlier. As The Louisiana Planter and Sugar Manufacturer noted in 1890:

St. John sugar refinery’s almost new outfit will meet a splendid and very large sugar crop this grinding [season] in St Martin parish. This excellent central sugar system by its benign influence . . . has encouraged for many miles around the growth of sugar cane. Col. J. B. Levert, the enterprising owner of the large sugar estate St. John and its grand sugar refinery, deserves credit for his push and energy and public spirit.

Approaching the Levert-St. John sugar refinery near St. Martinville.

Approaching the Levert-St. John sugar refinery near St. Martinville.(Photo by author)

St. John Plantation, now organized under the modern corporate name Levert-St. John, LLC, is owned by the Levert Companies. As the company’s website notes, “The principal asset of this company [Levert-St. John] is agricultural land (approximately 11,000 total acres), all in St. Martin Parish, Louisiana. The Levert-St. John, LLC lands are made up primarily of four plantations, St. John, Banker, Burton and Stella, all in St. Martin Parish.” Of that 11,000 acres, approximately 75% is dedicated to sugar production, the remainder focusing on rice and crawfish production.

Levert-St. John sugar refinery on Bayou Teche.

Levert-St. John sugar refinery on Bayou Teche.(Photo by author)

The sugar refinery at Levert-St. John dominates the surrounding flat sugarcane fields. We were fortunate to canoe past the structure at the height of grinding season (which runs from October to January), when the complex belches enormous clouds of steam into the winter sky. At any given time sugar mills either smell pleasantly sweet, like molasses, or they emit a god-awful stench, to which nothing of a polite nature compares. Levert-St. John must have smelled sweet that day, because I made no reference to the odor in my journal, and I believe I would have remembered the alternative.

In addition to the hissing, breathing refinery, we saw here the 264-foot-long, 14.7-foot-wide Levert-St. John Bridge, which appears on the National Register of Historic Places (site #98000268, added 1998). A double Warren truss swing bridge made of rusted steel girders, it was constructed in 1895 for railroad and pedestrian traffic. Eventually, however, the rails were covered with asphalt to form a single-lane bridge for automobiles (which I remember driving across in the 1980s — not the most secure experience). According to a study conducted for its National Register candidacy, the Levert-St. John Bridge is “the oldest known [extant] bridge in Louisiana, as well as the only known bridge of its type in the state. . . .”

The now defunct Levert-St. John Bridge.

The now defunct Levert-St. John Bridge.The year "1895" is cut into the steel plate above the opening.

(Click to enlarge; photo by author)

After paddling around and even under the bridge, Keith, Don, and I continued on toward St. Martinville. On the outskirts of town we reached the Longfellow-Evangeline State Historic Site [30.135863, -91.819224](more on Longfellow and Evangeline below), the centerpiece of which is Maison Olivier, a “Raised Creole Cottage . . . which shows a mixture of Creole, Caribbean, and French influences.” The home was built circa 1815 by French Creole planter Pierre Olivier Duclozel de Vezin, from whom two of my occasional canoeing partners, Preston Guidry and his brother Ben, trace direct lineage. I could not see the cottage from the bayou, but I did see Spanish longhorn cattle — a fitting living history display, because Spanish longhorn was indeed the variety of cattle raised in Louisiana during its colonial period (1699-1803). This variety is no longer seen in south Louisiana — at least not from my experience — although Texas longhorns still inhabit parts of that state, I having seen them for myself in the Hill Country.

My daughter flanked by two longhorns in Texas.

My daughter flanked by two longhorns in Texas.(Photo by author)

Immediately south of Longfellow-Evangeline, and just beside St. Martinville Senior High School (from which, by the way, Preston and Ben graduated), one can see, behind a low dam, the Cypress Bayou Coulee Canal [30.131748, -91.822636] running northwest into Bayou Tortue Swamp. A major wetlands area, Bayou Tortue Swamp begins on the north near Breaux Bridge and stretches to the Terrace Highway (Highway 96) on the south, and from the natural Teche levee on the east to an area abutting the Lafayette Regional Airport on the west. (It’s funny how I grew up in Lafayette never knowing such a large swamp existed nearby. Granted, I knew Lake Martin, but I had no idea it was part of a much larger swamp ecosystem.)

The cement boat at St. Martinville.

The cement boat at St. Martinville.(Photo by author)

As we neared downtown St. Martinville, Keith showed me two peculiar landmarks. One of these is a boat made of cement, now dilapidated and slowly sinking into the bayou. Cement boats, it turns out, are not unheard of. The other landmark is the site of a small cave [30.124257, -91.826246] in which local children used to play. Infinitely smaller than the one in which Tom Sawyer and Becky Thatcher became lost, the cave entrance has now been sealed with cement for reasons of safety; but you can see the cement patch over the cave’s entrance, about a hundred yards from the downtown bridge over the Teche. Preston once shoved a paddle into a crack in the cement, and the paddle went in all the way to the grip — a good five feet or so. (Decades ago I explored a similar cave in a bluff of the Vermilion River, just south of the bridge over which E. Broussard Road [Highway 733] crosses that bayou. There was not much to the cave: its pale clay walls extended into the bluff about ten or twelve feet before ending in a small hole in the ceiling, which in turn opened onto a pasture.)

Cement now covers the cave entrance.

Cement now covers the cave entrance.(Photo by author)

From the bayou at St. Martinville we saw St. Martin de Tours Catholic Church, the Acadian Memorial, the Museum of the Acadian Memorial, the adjacent African-American Museum, the Old Castillo Hotel (about which I’ve written previously) and the Evangeline Oak [30.121953, -91.827244], under which the Acadian maiden Evangeline went insane pining for her lost love Gabriel . . . well, that is how I heard the story.

American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow mentions St. Martinville in his epic poem Evangeline, first published in 1847:

On the banks of the Têche, are the towns of St. Maur and St. Martin. There the long-wandering bride shall be given again to her bridegroom, There the long-absent pastor regain his flock and his sheepfold.

In his book In Search of Evangeline, historian Carl A. Brasseaux has demonstrated that Evangeline never existed; nor did Emmeline Labiche, an Acadian exile on whom Longfellow supposedly based the character of Evangeline. Thus, neither Evangeline nor Emmeline are buried in “Evangeline’s Tomb” next to St. Martin de Tours. Yet the events against which Longfellow set the tragedy of Evangeline — the brutal mid-eighteenth-century expulsion of the Acadians from Nova Scotia by the British military — are factual, as is the settlement of many Acadian exiles in the St. Martinville area (among them my own ancestors, including Michel Bernard, who arrived in 1765 with

Evangeline.

Evangeline.(Artist: Frank Dicksee, 1882)

According to various sources, St. Martinville was known in olden times as “le petit Paris” because of its lavish social life — a story I’ve always regarded with some skepticism. Occupied by a church since the 1770s, the place, known as the Poste des Attakapas (a term that often referred to the region and not a specific locale), amounted to little until the early nineteenth century. At that time, however, local landowners divided their property into lots; sold or rented these parcels to settlers; and called the resulting community “St. Martinsville” after the local church’s patron saint. Thus, there seems to have been little time for St. Martinville to have flourished as a “little Paris” before the onslaught of tough economic times during and after the Civil War. The “petit Paris” claim, however, can be traced back as far as 1884, when (oddly enough) The Irish Monthly magazine of Dublin reported, “Before the war, which was peculiarly disastrous in its effects on this town, St. Martin’s used to be called Le petit Paris and was perhaps the most aristocratic place in Louisiana. But now many of its houses look old and dilapidated, and few traces of the little Paris remain.” (Source: Anonymous, “From Acadie to Attakapas: The Wanderings of Evangeline,” The Irish Monthly 12 [1884], p. 179.)

"Evangeline's Tomb," St. Martinville, Louisiana.

"Evangeline's Tomb," St. Martinville, Louisiana.(Photo by author)

Brasseaux shares my skepticism, however, observing,

The Creoles’ fall from grace [after the economic devastation of the Civil War] gave rise to a body of mythology regarding a golden age that never was. Most southern Louisianians are familiar with the stories of the spiders imported from China for the Oak and Pine Alley wedding [held near St. Martinville], with the celebrated performances of French opera companies in antebellum St. Martinville, with the presence of the great houses of French nobility who took refuge along Bayou Teche after the French Revolution, and with the donation of a baptismal font by Louis XVI to St. Martin of Tours Catholic Church — all stories proven unfounded by recent historical research. Yet these stories persist because they gave, and still provide, the fallen Creole elite with a continuing sense of social prominence based upon perceived past glories. (Brasseaux, French, Cajun, Creole, Houma: A Primer on Francophone Louisiana [2005], p. 102.)

Cover of Brasseaux's French, Cajun, Creole, Houma (2005).

Cover of Brasseaux's French, Cajun, Creole, Houma (2005).As we left St. Martinville and paddled into the countryside, I spotted a few ibises on a mud flat, pecking away at minnows. As a historian I found this of interest because the ibis, with its distinctive downturned beak, is strongly linked to ancient Egypt. There religious mythology associated the ibis with Thoth, the ibis-headed god of wisdom and writing. The “father of history,” Herodotus, recorded of ancient Egypt, “When a man has killed one of the sacred animals, if he did it with malice . . . he is punished with death; if unwittingly, he has to pay such a fine as the priests choose to impose. When an ibis, however, or a hawk is killed, whether it was done by accident or on purpose, the man must needs die [my italics].” The ibises we saw that day were young white ibises whose plumage had not yet turned completely white.

A pair of ibises along the Teche below St. Martinville.

A pair of ibises along the Teche below St. Martinville.(Photo by author)

A little after 1 p.m. we spotted the Keystone Lock and Dam [30.071095, -91.828859], for all practical purposes a convenient line of demarcation between the upper and lower Teche. Between the dam and us floated numerous islands of water hyacinth, one of them, the largest, measuring about 75 feet in length. Since starting our trip at Port Barre, we have worried about hyacinth. An invasive species, we feared it would at some point block our progress, clogging the entire bayou from one bank to the other. Those we now saw represented the largest concentration we had yet encountered, but it was not enough to stop us; we merely paddled around the aquatic plants or sometimes plowed straight through them, feeling the drag on the bottom of the canoe. Aerial photographs showed even denser masses of water hyacinth ahead of us, near Baldwin and Franklin. But we would not reach those towns on the current stage.

A raft of water hyacinths floating on the Teche.

A raft of water hyacinths floating on the Teche.The Keystone Lock and Dam are in the distance.

(Photo by author)

As we closed in on the dam, the sound of water topping the cement structure became louder. Here we had no choice but to do a portage. I don’t know how people pronounce “portage” elsewhere in the country, but in south Louisiana the most common pronunciation I hear is the French pronunciation, which is POR-TAHZH. What is perplexing, however, is that the French place name Fausse Pointe — an archaic name for our stopping point that day, Loreauville, as well as for a stretch of the Teche near New Iberia, and now the name of a nearby lake and state park — is almost universally pronounced (that is, arguably mispronounced), even by Cajuns who know the local patois, as FAW-SEE POINT instead of FAHS POINT. This Anglicized pronunciation jars me, just as the English pronunciation of portage jars me.

We went ashore here to make a portage.

We went ashore here to make a portage.(Photo by author)