Sur la Teche: Exploring the Bayou by Canoe, Stage 2

Continued from Part I:

Preston, Jacques, Keith and I made stage two of our run down the Teche on November 5, 2011, putting in where we left off last time, at Arnaudville, right behind Myron’s Maison de Manger. That day the sky was mostly clear and the temperature was 41 °F in the morning, 72 °F in the afternoon, and in the low to mid-50s °F by the time we got started. We paddled southeast with the current toward our stopping point, the town of Parks.

Bayou Teche on the morning of the second stage.

Bayou Teche on the morning of the second stage.

(Photo by author)

Early on I observed more garbage than previously in the bayou, including two basketballs and a few ice chests. Basketballs and ice chests became common sights on the Teche. (We saw about ten ice chests that day.) People spend an awful lot of money on basketballs and ice chests that ultimately become flotsam on the bayou. On this and future runs Keith and I competed half-heartedly to see who spotted the largest number of these objects.

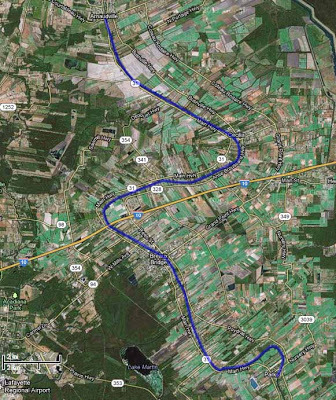

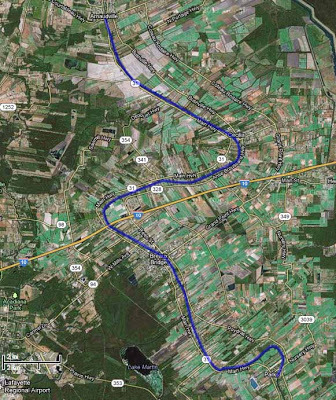

Aerial photograph of Stage 2, Arnaudville to Parks.

Aerial photograph of Stage 2, Arnaudville to Parks.

(Source: Google Maps)

The first town we reached was Cecilia. There many houses lined the Teche, one of which had a dock sporting a ship’s name plate: Argosy President. It sounded like a riverboat casino, many of which can be found along the Gulf Coast — not on the Teche, but, as I’ll discuss later, there is a land-based casino within site of the bayou farther downstream. (The nearest riverboat casino is the Amelia Belle, located on Bayou Boeuf some eight miles from the Teche’s mouth.) Some Internet sleuthing revealed that Argosy President was the former name of a 180-foot, 1,200-ton “platform ship” (built 1985) now known as the Ensco President. (Source: ShipsAndOil.com.) Given the region’s deep-rooted ties to the petroleum industry, it didn’t surprise me that the Argosy President supplied offshore oil platforms.

A typical bayou scene that day.

A typical bayou scene that day.

(Photo by author)

We soon paddled under Poché Bridge — known for the boudin at nearby Poché Market on the west bank of the Teche — and a short time later saw a patch of land occupied by numerous chickens, each in its own little coop. They looked like fighting cocks to me, even though Louisiana outlawed cockfighting in 2008. Some south Louisianians condemned the ban, asserting that cockfighting was a Cajun tradition and so ought to be preserved. Indeed, the symbol of the Cajun activist group Action Cadienne — dedicated to preserving the Cajun French dialect — is a fighting cock. (I suppose one could argue that the symbol is not a fighting cock — the animal has no metal spurs or barbs attached to its legs — but is merely a very angry rooster, talons poised to attack. Yet it seems clear to me that the symbol is meant to evoke south Louisiana’s rural cockfighting tradition.)

It was here, around Cecilia, that we first saw signs of beavers, whose gnaw marks now and then decorated the trunks of trees along the bayou. Many of these marks appeared fresh, yet we never spotted any of these creatures at work. On a later stage of the trip, when we diverted onto Bayou La Chute for a short paddle, we saw a few beaver slides — paths carved in the mud by these semi-aquatic rodents gliding into the water over and over again on the same spot. But again, no actual beavers. (They are largely nocturnal.)

Beaver gnaw marks on a cypress knee.

Beaver gnaw marks on a cypress knee.

(Photo by author)

On this stretch I took note of the many species of plant life along the Teche: live oak, cypress, pecan, elephant ears, reeds and rushes (called by our Cajun ancestors “les joncs”), many Chinese tallow (an invasive species). Occasionally we saw clumps of cypress knees rising from the water, or from the muddy batture, the sometimes flooded strip of land between the water’s edge and the bayou’s bank or natural levee. Some of the cypress knees along the Teche grow fairly tall, two or three feet in height. I've seen some of these knees (not necessarily those on the Teche) made into lamps or clocks.

Cypress knees along the Teche.

Cypress knees along the Teche.

(Photo by author)

It was also on this stretch that we found an interesting artifact protruding from the water: a rusted but intact riveted pipe about a foot in diameter and running a good eight to ten feet before disappearing into the dark, soggy bank. It looked like — well, a smokestack from a steamboat. There were certainly plenty of steamboats on the Teche from around 1830 to the steam era's final gasp around World War II. “And what if it belonged to a gunboat?” I could not help but wonder. Gunboats steamed up and down Bayou Teche during the Civil War, and sometimes went to the bottom, either because they sank in battle, were scuttled, or hit a snag.

The riveted pipe.

The riveted pipe.

(Photo by author)

I suspended judgment until I collected more evidence and eventually, I think, discovered the object’s purpose. Paddling downstream over several months, we saw here and there what at first appeared to be burial tombs, inevitably made of the red-orange brick common to the region. Some of these "tombs" sat close to the water’s edge; others crumbled into the water and in the shade disappeared beneath the bayou's black surface. These brick “tombs,” however, often sprouted sizable rusted iron bolts, which were clearly intended to hold a large piece of machinery in place.

"Tombs" along the Teche.

"Tombs" along the Teche.

(Photo by author)

At first I thought these “pilings,” as I began to call them in preference to “tombs,” must have been associated with sugarhouses, which once lined the bayou from St. Martin Parish to the bayou’s mouth. This was all sugar country, and one sugar plantation after another ran long the waterway. The pilings seemed to be of the correct nineteenth-century vintage for a sugarhouse. We finally noticed a piling with rusty iron machinery still bolted to it. It turned out to be a powerful steam pump — a beautiful machine that looked like it might have belonged in the engine room of the Titanic, if only it had been on larger scale. We stopped the canoe so that I could photograph it more closely. Letters embossed in the oxidized iron read:

IVENS DOUBLE SUCTION PUMPBOLAND & GSCHWIND CO LTDNEW ORLEANS LA

Model and manufacturer embossed on the pump housing.

Model and manufacturer embossed on the pump housing.

(Photo by author)

Rising vertically from this steam pump stood a riveted iron pipe very similar to the one we saw in the bayou around Cecilia.

The entire pump assembly with upright riveted pipe.

The entire pump assembly with upright riveted pipe.

(Photo by author)

But what was the purpose of this pump and the three or four others we eventually found along the Teche? Did they pump water from the Teche, or intothe Teche?

Sugarcane planting required excellent drainage, and as historians Glenn R. Conrad and Ray F. Lucas observe in their book White Gold: A Brief History of the Louisiana Sugar Industry, 1795-1995 (1995), “After the introduction of steam power, many planters installed steam water pumps to pump water over the protection levees into the back lowlands.” But the pumps we saw did not sit next to back lowlands; they sat next to the Teche itself.

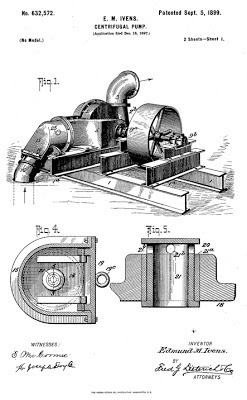

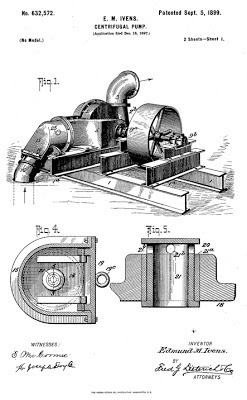

Patent drawing for a similar Ivens pump, dated 1899.

Patent drawing for a similar Ivens pump, dated 1899.

(Source: Google Books)

It is nonetheless possible the pumps fed excess rainwater into the bayou, or, in dry times, drew water from the Teche for irrigation. It may be, however, that some of these pumps were used to flood rice fields, because for a period some farmers along the Teche actually grew rice. I do not believe it is by chance, for example, that the Conrad Rice Mill (maker of KONRIKO products) stands in New Iberia, just blocks from the Teche. The mill’s location is likely a vestige of these nearly forgotten rice-growing days along the bayou.

In any event, I remain unsure of the exact purpose of these steam pumps.

Approaching I-10 by canoe.

Approaching I-10 by canoe.

(Photo by author)

Preston, Jacques, Keith and I continued to head downstream along the bayou. South of Cecelia the bayou skirted Interstate 10, the superhighway stretching from Florida to California. The sound of speeding vehicles, including eighteen-wheelers, became increasingly loud — an unavoidable incursion of the rapid modern world into our slow exploration of the Teche. To compound this feeling a B-52 bomber circled overhead, creating mammoth shadows on the clouds below it. I’d never seen a B-52 except in photos until the previous weekend, when I attended an airshow in Lafayette; now I’d seen two B-52s in only a week. Go figure! (The nearest B-52 base is Barksdale Air Force Base in north Louisiana, some two hundred miles to the north.)

The bayou gets wider as we paddle downstream.

The bayou gets wider as we paddle downstream.

Note egret in flight at left.

(Photo by author)

It was at this time we saw our first motorboat on the bayou. Previously we had encountered only canoes, pirogues, and other small wooden boats, all paddle-driven, and none of them actually on the bayou, but on shore, leaning against sheds or sitting upside down on blocks. Even the motorboat in question was moored to a dock. It drove home the point that the Teche so far seemed underutilized by sportsmen and pleasure boaters. We had traveled some thirty miles from the bayou's headwaters and had yet to see any other boaters. At 1:40 pm we passed under I-10 and reached the outskirts of Breaux Bridge. From this point on we saw increasing numbers of “bushlines,” “trotlines” (or “troutlines,” as some say), and “juglines,” all simple but effective means of fishing on the Teche. In the case of a bushline, a fishing line with hook and sinker is tied to a low-hanging branch and left unattended to make a catch. A trotline, on the other hand, consists of a line tied horizontally over the surface of the water, say from one low-hanging branch to another, and to which are tied several fishing lines with hooks and sinkers. A jugline consists of a floating plastic jug (often an empty soda or bleach bottle), to which are tied a hook and sinker, as well as a weight to keep the jug from drifting away. It is understood that one never touches another’s lines, but once I inspected a jugline out of curiosity. Pulling up the line I found it baited with chicken and weighted by a railroad spike. I immediately put the jugline back in the water so that it could “do its thing.”

A jugline farther down the Teche,

A jugline farther down the Teche,

with the Keystone Lock and Dam in background.

(Photo by author)

As we entered Breaux Bridge we saw modern suburban homes along the banks. Later, as we exited the town, we passed the entrance of the Ruth Canal in the west bank (+30° 14' 43.80", -91° 52' 51.77"); it runs to Lake Martin and from there to the Vermilion River. Along this stretch we spotted a blue heron on the hunt and two or three dead animals in the water — deer or goats or large dogs, I couldn’t tell. We saw enough of these in the Teche to dissuade me from ever wanting to swim in the bayou, much less drink from it, or even eat a fish from it. I admire, however, the brave appetites of those bushline, trotline, and jugline fishermen.

Approaching Parks, Louisiana.

Approaching Parks, Louisiana.

(Photo by author)

Toward the end of the day we finally encountered our first fellow boater.

We landed at Cecile Rousseau Memorial Park in Parks at 4:45 pm, having covered 23.6 miles in 5 hours, 57 minutes. We now had ninety miles left to go before we reached the mouth of the Teche.

Only in south Louisiana:

Only in south Louisiana:

trashcan in Rousseau Park, Parks, Louisiana.

(Photo by author)

Preston, Jacques, Keith and I made stage two of our run down the Teche on November 5, 2011, putting in where we left off last time, at Arnaudville, right behind Myron’s Maison de Manger. That day the sky was mostly clear and the temperature was 41 °F in the morning, 72 °F in the afternoon, and in the low to mid-50s °F by the time we got started. We paddled southeast with the current toward our stopping point, the town of Parks.

Bayou Teche on the morning of the second stage.

Bayou Teche on the morning of the second stage.(Photo by author)

Early on I observed more garbage than previously in the bayou, including two basketballs and a few ice chests. Basketballs and ice chests became common sights on the Teche. (We saw about ten ice chests that day.) People spend an awful lot of money on basketballs and ice chests that ultimately become flotsam on the bayou. On this and future runs Keith and I competed half-heartedly to see who spotted the largest number of these objects.

Aerial photograph of Stage 2, Arnaudville to Parks.

Aerial photograph of Stage 2, Arnaudville to Parks.(Source: Google Maps)

The first town we reached was Cecilia. There many houses lined the Teche, one of which had a dock sporting a ship’s name plate: Argosy President. It sounded like a riverboat casino, many of which can be found along the Gulf Coast — not on the Teche, but, as I’ll discuss later, there is a land-based casino within site of the bayou farther downstream. (The nearest riverboat casino is the Amelia Belle, located on Bayou Boeuf some eight miles from the Teche’s mouth.) Some Internet sleuthing revealed that Argosy President was the former name of a 180-foot, 1,200-ton “platform ship” (built 1985) now known as the Ensco President. (Source: ShipsAndOil.com.) Given the region’s deep-rooted ties to the petroleum industry, it didn’t surprise me that the Argosy President supplied offshore oil platforms.

A typical bayou scene that day.

A typical bayou scene that day.(Photo by author)

We soon paddled under Poché Bridge — known for the boudin at nearby Poché Market on the west bank of the Teche — and a short time later saw a patch of land occupied by numerous chickens, each in its own little coop. They looked like fighting cocks to me, even though Louisiana outlawed cockfighting in 2008. Some south Louisianians condemned the ban, asserting that cockfighting was a Cajun tradition and so ought to be preserved. Indeed, the symbol of the Cajun activist group Action Cadienne — dedicated to preserving the Cajun French dialect — is a fighting cock. (I suppose one could argue that the symbol is not a fighting cock — the animal has no metal spurs or barbs attached to its legs — but is merely a very angry rooster, talons poised to attack. Yet it seems clear to me that the symbol is meant to evoke south Louisiana’s rural cockfighting tradition.)

It was here, around Cecilia, that we first saw signs of beavers, whose gnaw marks now and then decorated the trunks of trees along the bayou. Many of these marks appeared fresh, yet we never spotted any of these creatures at work. On a later stage of the trip, when we diverted onto Bayou La Chute for a short paddle, we saw a few beaver slides — paths carved in the mud by these semi-aquatic rodents gliding into the water over and over again on the same spot. But again, no actual beavers. (They are largely nocturnal.)

Beaver gnaw marks on a cypress knee.

Beaver gnaw marks on a cypress knee.(Photo by author)

On this stretch I took note of the many species of plant life along the Teche: live oak, cypress, pecan, elephant ears, reeds and rushes (called by our Cajun ancestors “les joncs”), many Chinese tallow (an invasive species). Occasionally we saw clumps of cypress knees rising from the water, or from the muddy batture, the sometimes flooded strip of land between the water’s edge and the bayou’s bank or natural levee. Some of the cypress knees along the Teche grow fairly tall, two or three feet in height. I've seen some of these knees (not necessarily those on the Teche) made into lamps or clocks.

Cypress knees along the Teche.

Cypress knees along the Teche.(Photo by author)

It was also on this stretch that we found an interesting artifact protruding from the water: a rusted but intact riveted pipe about a foot in diameter and running a good eight to ten feet before disappearing into the dark, soggy bank. It looked like — well, a smokestack from a steamboat. There were certainly plenty of steamboats on the Teche from around 1830 to the steam era's final gasp around World War II. “And what if it belonged to a gunboat?” I could not help but wonder. Gunboats steamed up and down Bayou Teche during the Civil War, and sometimes went to the bottom, either because they sank in battle, were scuttled, or hit a snag.

The riveted pipe.

The riveted pipe.(Photo by author)

I suspended judgment until I collected more evidence and eventually, I think, discovered the object’s purpose. Paddling downstream over several months, we saw here and there what at first appeared to be burial tombs, inevitably made of the red-orange brick common to the region. Some of these "tombs" sat close to the water’s edge; others crumbled into the water and in the shade disappeared beneath the bayou's black surface. These brick “tombs,” however, often sprouted sizable rusted iron bolts, which were clearly intended to hold a large piece of machinery in place.

"Tombs" along the Teche.

"Tombs" along the Teche.(Photo by author)

At first I thought these “pilings,” as I began to call them in preference to “tombs,” must have been associated with sugarhouses, which once lined the bayou from St. Martin Parish to the bayou’s mouth. This was all sugar country, and one sugar plantation after another ran long the waterway. The pilings seemed to be of the correct nineteenth-century vintage for a sugarhouse. We finally noticed a piling with rusty iron machinery still bolted to it. It turned out to be a powerful steam pump — a beautiful machine that looked like it might have belonged in the engine room of the Titanic, if only it had been on larger scale. We stopped the canoe so that I could photograph it more closely. Letters embossed in the oxidized iron read:

IVENS DOUBLE SUCTION PUMPBOLAND & GSCHWIND CO LTDNEW ORLEANS LA

Model and manufacturer embossed on the pump housing.

Model and manufacturer embossed on the pump housing.(Photo by author)

Rising vertically from this steam pump stood a riveted iron pipe very similar to the one we saw in the bayou around Cecilia.

The entire pump assembly with upright riveted pipe.

The entire pump assembly with upright riveted pipe.(Photo by author)

But what was the purpose of this pump and the three or four others we eventually found along the Teche? Did they pump water from the Teche, or intothe Teche?

Sugarcane planting required excellent drainage, and as historians Glenn R. Conrad and Ray F. Lucas observe in their book White Gold: A Brief History of the Louisiana Sugar Industry, 1795-1995 (1995), “After the introduction of steam power, many planters installed steam water pumps to pump water over the protection levees into the back lowlands.” But the pumps we saw did not sit next to back lowlands; they sat next to the Teche itself.

Patent drawing for a similar Ivens pump, dated 1899.

Patent drawing for a similar Ivens pump, dated 1899.(Source: Google Books)

It is nonetheless possible the pumps fed excess rainwater into the bayou, or, in dry times, drew water from the Teche for irrigation. It may be, however, that some of these pumps were used to flood rice fields, because for a period some farmers along the Teche actually grew rice. I do not believe it is by chance, for example, that the Conrad Rice Mill (maker of KONRIKO products) stands in New Iberia, just blocks from the Teche. The mill’s location is likely a vestige of these nearly forgotten rice-growing days along the bayou.

In any event, I remain unsure of the exact purpose of these steam pumps.

Approaching I-10 by canoe.

Approaching I-10 by canoe.(Photo by author)

Preston, Jacques, Keith and I continued to head downstream along the bayou. South of Cecelia the bayou skirted Interstate 10, the superhighway stretching from Florida to California. The sound of speeding vehicles, including eighteen-wheelers, became increasingly loud — an unavoidable incursion of the rapid modern world into our slow exploration of the Teche. To compound this feeling a B-52 bomber circled overhead, creating mammoth shadows on the clouds below it. I’d never seen a B-52 except in photos until the previous weekend, when I attended an airshow in Lafayette; now I’d seen two B-52s in only a week. Go figure! (The nearest B-52 base is Barksdale Air Force Base in north Louisiana, some two hundred miles to the north.)

The bayou gets wider as we paddle downstream.

The bayou gets wider as we paddle downstream. Note egret in flight at left.

(Photo by author)

It was at this time we saw our first motorboat on the bayou. Previously we had encountered only canoes, pirogues, and other small wooden boats, all paddle-driven, and none of them actually on the bayou, but on shore, leaning against sheds or sitting upside down on blocks. Even the motorboat in question was moored to a dock. It drove home the point that the Teche so far seemed underutilized by sportsmen and pleasure boaters. We had traveled some thirty miles from the bayou's headwaters and had yet to see any other boaters. At 1:40 pm we passed under I-10 and reached the outskirts of Breaux Bridge. From this point on we saw increasing numbers of “bushlines,” “trotlines” (or “troutlines,” as some say), and “juglines,” all simple but effective means of fishing on the Teche. In the case of a bushline, a fishing line with hook and sinker is tied to a low-hanging branch and left unattended to make a catch. A trotline, on the other hand, consists of a line tied horizontally over the surface of the water, say from one low-hanging branch to another, and to which are tied several fishing lines with hooks and sinkers. A jugline consists of a floating plastic jug (often an empty soda or bleach bottle), to which are tied a hook and sinker, as well as a weight to keep the jug from drifting away. It is understood that one never touches another’s lines, but once I inspected a jugline out of curiosity. Pulling up the line I found it baited with chicken and weighted by a railroad spike. I immediately put the jugline back in the water so that it could “do its thing.”

A jugline farther down the Teche,

A jugline farther down the Teche,with the Keystone Lock and Dam in background.

(Photo by author)

As we entered Breaux Bridge we saw modern suburban homes along the banks. Later, as we exited the town, we passed the entrance of the Ruth Canal in the west bank (+30° 14' 43.80", -91° 52' 51.77"); it runs to Lake Martin and from there to the Vermilion River. Along this stretch we spotted a blue heron on the hunt and two or three dead animals in the water — deer or goats or large dogs, I couldn’t tell. We saw enough of these in the Teche to dissuade me from ever wanting to swim in the bayou, much less drink from it, or even eat a fish from it. I admire, however, the brave appetites of those bushline, trotline, and jugline fishermen.

Approaching Parks, Louisiana.

Approaching Parks, Louisiana.(Photo by author)

Toward the end of the day we finally encountered our first fellow boater.

We landed at Cecile Rousseau Memorial Park in Parks at 4:45 pm, having covered 23.6 miles in 5 hours, 57 minutes. We now had ninety miles left to go before we reached the mouth of the Teche.

Only in south Louisiana:

Only in south Louisiana:trashcan in Rousseau Park, Parks, Louisiana.

(Photo by author)

Published on October 30, 2012 15:56

No comments have been added yet.