The Challenge of Storytelling by Numbers: Cajuns, Creoles, and the Limits of Census Data

“Historians and math

“Historians and math do not always go well together”

WhileI never excelled at math (an understatement), I nonetheless use quantitativeanalysis, albeit sparingly, in my books. I did so perhaps most notably in TheCajuns: Americanization of a People, which I sprinkled lightly with numericaldata gleaned from U.S. censuses, including, but not limited to, the most recentone, the 1990 Census. (I wrote in the late 1990s, before the 2000 U.S. Censushad been compiled.)(2)

My 2023 book The Cajuns:

Americanization of a People

Althoughonly about a quarter-century ago, I wrote The Cajuns at a time when censusdata was not, unlike today, readily available on the Internet — at least not inany detail. Researchers instead had to visit a brick-and-mortar library andconsult multi-volume censuses printed on actual paper as well as inother forms of media. Moreover, finding sought-after data could be extremelydifficult because, as one library notes, “the 1990 census filled hundreds ofvolumes, CDs and numerous tape files. . . .”(3) Even then, the required data might not actually exist in any ofthose published sources.

Inthat case, there was an alternate source of census data: the Public Use MicrodataSample (PUMS), a digital database of raw census data based on a 1-percent,3-percent, or (as I myself used) 5-percent sample of respondents in specificgeographic regions. This is important, because while the short-form 1990 U.S. Census — the version sent to most American households — askedrecipients how they identified racially (Black, White, Hispanic, and so on), itdid not ask how they identified ethnically (Italian, Jamaican, Filipino,Dutch, Norwegian, or any number of other ethnicities). However, the long-form 1990U.S. Census — received by 5 percent of U.S. households — did askrespondents to identify their ethnic ancestries. Using complicated formulas, theU.S. Census Bureau could then extrapolate from that sample to provide ancestral data aboutall U.S. households.

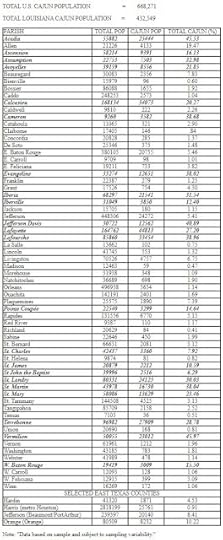

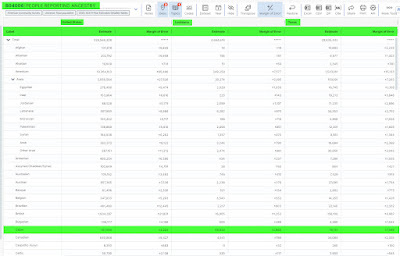

Figure 1: 1990 PUMS data, for Cajuns,

by Louisiana parishes and select Texas counties,

Acadiana parishes in bold,

(click to enlarge).

Image source: author's defunct website.

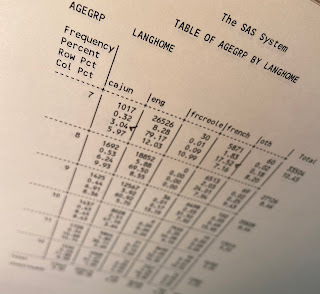

PUMSdata, however, was hardly perfect. Besides the fact it could never provide morethan an estimate (one would hope an accurate estimate),the general public often could not access PUMS data, which required somewhat powerfulcomputers (for the time) loaded with the proper, and rather complicated, software. As such, PUMS data generally had to be accessed through aninstitution, such as a university. Moreover, it was not enough to accessthe PUMS database: rather, you also had to know, or know someone who knew, how toprogram the database to obtain the sought-after data. And because that outputappeared in a form hardly describable as “WYSIWYG” (“what you see is what youget” or, more plainly, in a self-explanatory format), you also had to know, orknow someone who knew, how to interpret that very user-unfriendly data printout.

User-unfriendly PUMS data printout,

User-unfriendly PUMS data printout,1990 U.S. Census

Fortunately,I had access to PUMS data through the Sociology Department of Texas A&MUniversity, where I pursued my doctoral degree in History with a minor in RuralSociology of Minorities (very useful if, like me, you are studying the Cajunsand Creoles of rural and small-town south Louisiana). It was my Sociologyprofessor, Dr. Rogelio Saenz, who helped me to obtain and interpret the PUMsdata I sought.

For example, I might have asked the PUMS database to report howmany Louisianians in 1990 identified their ancestry as primarily Cajun or Acadian (the latter of whichI interpreted to mean “Cajun”)* and of those how many spoke French as theirfirst language in the home; or of those how many identified as World War IIveterans; or even of those how many spoke French in the home and also identifiedas World War II veterans. With this data I was able to extrapolatebackward and estimate the total number of Louisianians of Cajun ancestry who fought in World War II and how many of those “Cajun GIs” spoke French inwartime.(4) (A note: I did not compile 1990 PUMS data about Creoles,though that raw data did exist in the PUMS database. I chose not to do sobecause, while my dissertation topic originally focused on Cajuns andCreoles, I found it necessary to winnow my focus solely to Cajuns — otherwise Ibelieved the scope of my dissertation would have been too unwieldly. A fragment of my original research focusing on both Cajuns and Creoles can be found here.)

Intriguingly,the 1990 PUMS data revealed that there were 432,549 persons in Louisiana whoself-identified as primarily Cajun compared to 668,271 such persons in theentire U.S. (see Figure 1). Many of those out-of-state Cajuns no doubt emigrated fromLouisiana in the wake of the recent “oil glut” that shattered the state’soil-dependent economy in the mid- to late 1980s.(5)

ThisPUMS data also identified a number of quirks among the assumed Cajunpopulation. For example, it revealed that 10 percent of all Louisianians consideredthemselves as primarily Cajun. And while as mentioned 432,549 persons in Louisiana listed their primary ancestry as Cajun, another 25,000 listedtheir secondary ancestry as Cajun. Vermilion Parish, in south-central Louisiana,possessed the largest percentage of persons identifying primarily as Cajun, about 50percent. Also, the census suggested that most Cajun respondents had not strayedfar from their ancestral south Louisiana homeland: of the 668,271 persons throughout the U.S. identifying as primarily Cajun, 77 percent resided in Louisiana orneighboring Texas.(6)

Moreover,few persons in New Orleans considered themselves Cajun — despite the media andtourism industries painting New Orleans as a “Cajun” city, a claim thatappeared ad nauseum during the Cajun fad of the 1980s. Yet in 1990 only onepercent of respondents living in New Orleans proper (Orleans Parish) marked “Cajun” as their primary heritage. The percentage remained low (7 percent or less) in parishessurrounding New Orleans. Indeed, census data showed that New Orleans boasted about the same concentration of Cajuns as Houston. As I wrote in my book The Cajuns, “Houston, Texas, possessed nearly the same percentage of Cajuns as New Orleans — less than a quarter of a percent difference — and on a per capita basis Houston actually boasted 4.5 times as many Cajuns.” And yet, unlike New Orleans, the media and the tourism industries did not portray Houston as “the center of the Cajun universe.”(7)

❧

Overthe past twenty-five years since I did my PUMS research, the Internet has grownexponentially, along with the amount of useful (and not so useful) data it offersto scholars and laypersons alike. In fact, the U.S. Census Bureau’s website nowaffords the general public access to extremely detailed census results indigital format — meaning there is arguably no longer a need to navigate countlesshardcopy volumes to locate sought-after data. With a few clicks of a mouse,that information can now be accessed 24/7 using any computer (as well as digitaltablets and cell phones) linked to the Internet.

Thetask, however, still requires a degree of skill and patience because the requireddata might not at once be discernable. As with the old PUMS database,researchers might still have to figure out how to configure the census.govinterface to reveal the desired data — and just how to do that is not necessarily self-evident. In addition, it’s easier than ever to become mired in the sheervolume of census data now available to everyone. (Fortunately, I havefound that Census Bureau experts promptly answer requests for help submitted by the public per email.)

Thisbeing said, it is interesting to compare current U.S. census stats with the1990 census stats I consulted a quarter century ago. Moreover, it’s possible toconjure up similar stats for the other group of interest to me, Creoles — by which I mean, unless otherwise stated, Creoles by any definition, regardless of color. (In this essay I won’t wade into issues surrounding the word “Creole,” much less the assertion, which Iembrace, that “Cajuns are a type of Creole”; but my essays on these topics can befound here.)

Besidesconducting the usual decennial census, the U.S. Census Bureau now compilessomething called the American Community Survey (ACS). The Bureau describes theACS as “an ongoing survey that provides vital information on a yearly basisabout our nation and its people.” (You can read about the differences betweenthe decennial U.S. Census and the ACS here.)(8)And the ACS does count the number of respondents who identify as “Creole,” aswell as those who identify as “Cajun.” Accessing this sought-after data, however, is somewhatcomplicated: while population stats for “Cajuns” are fairly easy to find,those for “Creoles” are, unfortunately, buried a little deeper in the raw data.

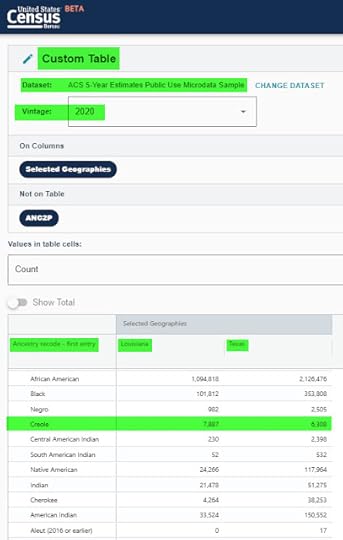

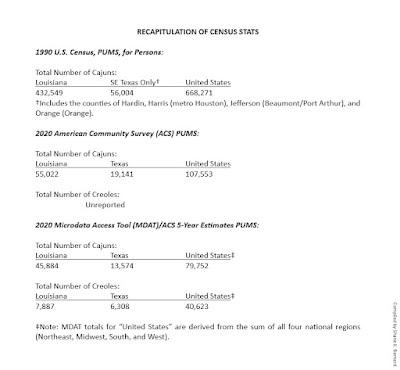

Accordingto one specific ACS table available on the U.S. Census Bureau website, namely,Table B04006, titled “People Reporting Ancestry” — accessible here, or see Figure 2 — 107,553 persons throughout the U.S. identified their primary ethnicity in2020 as “Cajun” (give or take about 4,222 persons according to the margin oferror — but I won’t list margins of error from here on out; you can find them onthe original charts). Of these, 55,022 lived in Louisiana, or 51.15 percent ofall Cajuns; while 19,141 lived in neighboring Texas, or 17.79 percent of allCajuns. (Note I am looking only at responses for primary ethnicity, not secondary,which I leave for others to explore.)(9)

Figure 2: Table B04006,

“People Reporting Ancestry,”

from the 2020 American Community Survey,

Cajun stats highlighted

(click to enlarge).

Alreadysomething odd is discernible: only 55,022 Cajuns exist in the entire stateof Louisiana? And those Cajuns comprise only 51 percent of the totalnumber of Cajun people in the entire U.S.? These stats seem way off! Butmore on this shortly.

Whatwe don’t find on Table B04006, however, is any reference to persons whoidentified as “Creole.” It seems the Census Bureau relegated those respondents to a catch-all “Other”category. As a result, Creoles went uncounted on this table as a standalone ethnic group.

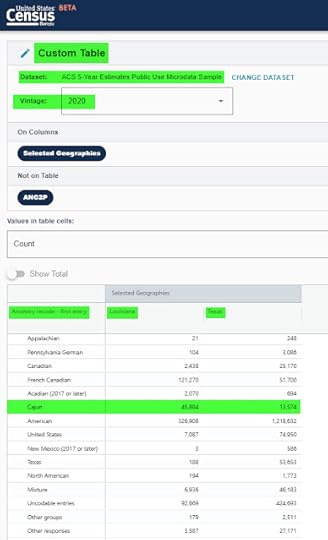

Thisdoes not mean the U.S. Census Bureau overlooked Creoles in 2020. In fact,self-described Creoles were counted, albeit on a different ACS table for2020: namely, a custom-generated table compiled using the Microdata AccessTool (MDAT), which drew its output from the ACS 5-Year Estimates PUMS dataset. The resultscan be accessed here, or see Figure 3.(10)

Accordingto this MDAT table, 7,887 persons in Louisiana identified their primaryethnicity in 2020 as “Creole,” while, for comparison, 6,308 persons in Texaslikewise identified their primary ethnicity as “Creole.” This reflects theemigration of south Louisiana Creoles to the Lone Star State, mainly itssoutheast region, over many generations going back well into the early to mid-20thcentury.

Again, however, these stats for Creoles, like those for Cajuns, seem incredibly off. Bywhich I mean “far too small.”

Figure 3: MDAT table for Creoles,

Louisiana and Texas, 2020,

Creole stats highlighted

(click to enlarge).

Otherconundrums also present themselves. Why, for example, are there so many fewer “Creoles”than “Cajuns”? If anything, I would expect more Creoles thanCajuns, not the other way around.

In my opinion these issues suggest we have run into the limitations of self-reported ethnic andracial data. A major issue, for example, is that a person of Creoleancestry might correctly identify as “Creole,” but just as correctly identifyas “African American” or “Afro American” or “Black” or “Afro” or “Negro” (all labelsrepresented on the MDAT table). They might also identify as members of thoseannoyingly generic, ill-defined, and I would assert almost meaningless “ethnicities,”namely “American” and “North American.” (Is “American” really an ethnicity or,as I would assert, a nationality?) They might also correctly identify as “Cajun”or “Acadian” or “French” or any number of other ethnicities they might claim. And this is considering only Creoles of African descent, not Creoles who identify as White and might correctly claim a variety of ancestries in their own right — thus further complicating the task of ethnic self-identification.

Theissue is the same for Cajuns. They might correctly identify as primarily “Cajun”or “Acadian” or “French” or “Canadian” or “French Canadian” or “Creole” (again,Cajuns can be viewed as a type of Creole) or “American” or “North American,”and so on.

Thismay explain why, whether we compare the 1990 census results to those in the2020 ACS Table, or the 2020 ACS table to the MDAT table for that same year, weend up with notable data discrepancies.

For example, the 2020 ACS table counted55,022 self-described Cajuns in Louisiana — but what happened to the other 377,527who identified as such in 1990? Similarly, according to the MDAT tablethere were 45,884 self-identified Cajuns in Louisiana in 2020 . . . about 9,000less than the 55,022 tallied for the same year on the separate ACStable (see Figure 4).(11)

Whythe difference between these two 2020 sources, both issued by the U.S. Census Bureau?

Figure 4: MDAT table for Cajuns,

Louisiana and Texas, 2020,

Cajun stats highlighted

(click to enlarge).

Asa demographic statistician at the Bureau kindly explained to me, “Forrelatively small groups there are sometimes differences in results depending onthe data set used. The microdata tool uses the American Community Survey (ACS)PUMS while Table B04006 uses the full ACS data set. This may be part of thereason why there would be a difference in a relatively small group such asCajun. Another reason is that 2020 was a difficult year for data collection dueto the [COVID] pandemic. The data from 2016-2020 for smaller groups may be lessreliable than normal.”(12)

Thisis, however, not the first time incongruities have been noticed by those whouse censuses to study south Louisiana. As I wrote in my Americanizationbook:

[R]esearchers have discovered a majordiscrepancy between the 1990 census and preliminary results from the 2000census. The 1990 census counted over 400,000 Cajuns in Louisiana, while the2000 census counted only about 40,000 — a roughly 90 percent decline in only tenyears! The U.S. Census Bureau clearly miscounted, either in 1990 or 2000 (orboth), for the disappearance of almost the entire Cajun population in only adecade is highly improbable. . . . Louisiana historian Carl A. Brasseaux . . .discounted the 2000 statistics, noting wryly that there are probably 40,000Cajuns on the north side of Lafayette Parish alone. Non-academics also havescoffed at the 2000 statistics. Lafayette’s Daily Advertiser [newspaper]ridiculed the figures as “cockeyed” and observed “Our government advises [us]that there aren’t as many Cajuns . . . as we saw dancing in the streets duringfestival time.” “If You’re One of 365,000 Missing Cajuns,” ran one of itsheadlines, “Please Send up a Flare.” Asked another newspaper, “Where Did Allthe Cajuns Go?”(13)

I in no way criticize the U.S. Census Bureau. In fact, Iwould now assert that such discrepancies in census data stem in part— perhaps in large part — from the fact that we are dealing (of course) with humanbeings; and human beings are innately subjective creatures.As such, they are not only difficult to pin down, but dislike being pinned down. As shown, the very multiplicity of correct answers a Cajun or Creole might give to an ancestry query is also problematic. Likewise, it is possible long-form census recipients chose, say, the first ethnic label that came to mind, rather than the ethnic label they themselves might have genuinely regarded as most suitable or accurate. Moreover, some, perhaps even many, recipients simply might not have answered the ancestry question, for whatever reason (confusion, impatience, privacy concerns, etc.).

Census data can be useful for indicating general demographic trends, but it can prove misleading if always taken at face value. (Again, only 7,887 Creoles in all of Louisiana in 2020? And only 55,022 Cajuns?) This, however, is where narrative history can complement census data, as well as complement more quantitative approaches to history in general. By drawing on traditional and — as I like to do — not-so-traditional sources, history as good old-fashioned storytelling can present fuller, more accurate, and I would argue more engaging views of the past. Conversely, quantitative data, when used in just the right, sparing amount, can complement traditional narrative history. And that quantitative data — wary as I am of math and my own math skills — has helped me to better understand the people called Cajuns and Creoles, and to convey that understanding to others.

Figure 5:

Figure 5: Recapitulation of statistics

used in this essay

(click to enlarge)

*Note: In the 1990 PUMS data I counted as “Cajun” both those who identified as primarily “Cajun” as well as those who identified as primarily “Acadian.” It could be argued I made a leap of faith by assuming that those persons of Acadian descent might be considered “Cajun.” Certainly, there would be exceptions. For example, a notable Acadian-derived population resides in Maine, which borders the former French colony of Acadie, now the Canadian provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. Those Mainers of Acadian descent most likely do not consider themselves “Cajuns” because Cajuns are largely a Louisiana phenomenon — the Cajuns arising in the first place from persons of Acadian descent intermarrying with other ethnic groups (French, German, Spanish, etc.) on the south Louisiana frontier. In general, however, I believed it reasonable to assume that persons in Louisiana (and east Texas, for that matter) who identified as Acadian by heritage might also identify as “Cajun.” Indeed, I would be surprised if they did not. Moreover, I regarded the percentage of exceptions to this rule as likely so small as to be irrelevant, because every other source of data (historical, journalistic, impressionistic, etc.) indicated the obvious: that a large population of persons residing in Louisiana and east Texas identified as “Cajuns.”

Special thanks to Angela (Angie) Buchanan, Demographic Statistician, Ethnicity and Ancestry Branch, Population Division, U.S. Census Bureau; and Alli Coritz, Ph.D., Statistician Demographer, Population Division/Racial Statistics Branch, U.S. Census Bureau, for explaining to me the workings of more recent census data available on https://data.census.gov/.

Notes

(1) Robert William Fogel and Stanley L. Engerman,Time on the Cross: The Economics of American Negro Slavery, revised ed. (New York: W.W. Norton, 1995). For an example of how quantitative data can be used to study Cajuns and Creoles from a sociological perspective, see, for instance, Carl L. Bankston III and Jacques Henry, “The Socioeconomic Position of the Louisiana Creoles: An Examination of Racial and Ethnic Stratification,” Social Thought & Research, 21 (April 1998): 253-277.

(2) Shane K. Bernard, The Cajuns:Americanization of a People(Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2003).

(3) “The U.S. Census Collection,” New York StateLibrary, 8 February 2024, https://www.nysl.nysed.gov/uscensus.htm, accessed 22May 2024.

(4) For more on Cajun GIs in World War II, seeBernard, “Cajuns during Wartime,” in The Cajuns, 3-22; and Jason P.Theriot, Frenchie: The Story of the French-Speaking Cajuns of World War II(Lafayette: UL Press, 2024 [forthcoming]).

(5) 1990 PUMS, for Persons. See Bernard, TheCajuns, xxiii-xxiv, 122-24, 152 (n. 9). See also Figure 1 in this blogarticle, from Shane K. Bernard, “Population Data, Cajuns,” Encyclopedia ofCajun Culture [author’s archived defunct website], 6 June 2002,https://web.archive.org/web/200206061... 16 May 2024.

For more on the interpretation of 1990PUMs data in my book The Cajuns, see my blog article “Tracking theDecline of Cajun French,” 22 March 2011, http://bayoutechedispatches.blogspot...., accessible here.

(6) Ibid.

(7) Bernard, The Cajuns, 120.

(8) “The Importance of the American CommunitySurvey and the Decennial Census,” 13 March 2024, United State Census Bureau,https://www.census.gov/programs-surve..., accessed16 May 2024.

(9) “People Reporting Ancestry,” United StatesCensus Bureau, 2020,https://data.census.gov/table/ACSDT5Y... 16 May 2024, or see Figure 2.

(10) Custom MDAT Table, for Creoles, based on ACS 5-YearEstimates Public Use Microdata Sample, 2020,https://data.census.gov/mdat/#/search... 16 May 2024, or see Figure 3.

(11) “People Reporting Ancestry”; Custom MDAT Table, for Cajuns, based on ACS 5-Year Estimates Public Use Microdata Sample, 2020, https://data.census.gov/mdat/#/search..., accessed 16 May 2024, or see Figure 4.

(12) Angela Buchanan, Demographic Statistician,Ethnicity and Ancestry Branch, Population Division, U.S. Census Bureau, [greaterWashington, D.C., area], to Shane K. Bernard, New Iberia, La., 13 May 2024, emailcorrespondence in author’s possession.

(13) Bernard, The Cajuns, xxiii-xxiv.