Race, Language, and Culture: A Note on Identity in Louisiana

❧

I have seen it stated in a fewjournalistic and social media outlets that, to quote my fellow researcher JosephDunn (for whom I have great respect), “From the late 19th century through today,the baseline for identity in Louisiana shifted from language and culture torace and skin color.” This change occurred, he states, because “of heritagelanguage loss, forced assimilation into English, and Americanization.”(1)I think it is important, however, tonote that the idea of ascribing identity to race, or racialization, did not appear from nothingness afterthe Louisiana Purchase of 1803.(2) Indeed, there is strong evidence that race — notmerely language and culture — served as a vital element in fixing identity decadesbefore Napoleon sold Louisiana to the fledgling United States.

The Code Noir (1724)

The Code Noir (1724)Source: Bibliothèque Nationale de France

In 1724, for example, Frenchadministrators in Louisiana adopted a set of regulations aimed at governing racerelations in the colony. The very name of that decree invoked race: the CodeNoir — the Black Code. France created the Code Noir, to quoteLouisiana’s highly accessible state encyclopedia, “to regulate the interactionof European-descended (blancs) and African-descended people (noirs)in colonial Louisiana.”(3) Though itcontained some measures pertaining to Jews in the colony, the Code Noir(again, as its name implies) primarily concerned persons of African heritage:it regulated “nègres,” both “libres” and “esclaves,” aswell as their treatment by enslavers and by the colonial apparatus in general.

Furthermore, it identified those itregulated based not on their language or culture, but on their race and, beyond that, their status as free or enslaved. Forexample, the code outlawed (on paper if not in practice) marriage betweenWhites and persons of African descent, even if the latter were not enslaved but“gens de couleur libre” (free persons of color). It precluded enslavedBlacks from selling anything without the written permission of their enslavers.It forbade Blacks enslaved by different masters from gathering in large groups,even for weddings, on pain of being flogged or even branded. And so on.(4)

After Louisiana became Spanish territoryin 1762 its new rulers adopted (eventually) their own race-based regulations,the Sistema de Castas, or Caste System. Tulane historian Lawrence N.Powell describes this intricate system as “a taxonomic arrangement that oftenverged on the absurd” because of its tortuous attempt to categorize race. As Powellobserves about New Spain in general in The Accidental City: Improvising NewOrleans:

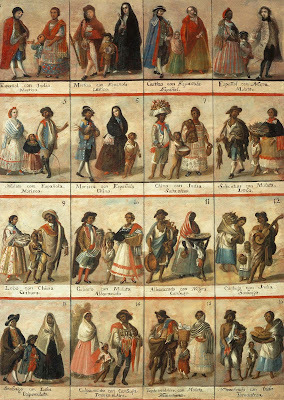

A mixed-race population was foreverspilling into the interstitial spaces, and obliging the Spanish bureaucratscharged with keeping track of it all — the census takers and notaries on theone hand, and thousands of parish priests on the other, all keeping raciallydistinct baptismal and marriage records — to devise, on the fly, cognitivelabels for new people. . . . One Mexican scholar counted forty-six differentmixed-blood types in the sources he consulted. Only ten categories werefundamental, however, and these were all spinoffs of three main divisions:Spaniards, Indians, and Negroes. . . . One scholar has dubbed the system a ‘pigmentocracy’[my italics].

Those racial categories and sub-categories used by the Spanish included Mestizos, Castizos, Mulatos, Moriscos, Lobos, and Coyotes, as well as the overtly quantitative Cuarterones and Quinterones, among other gradations based on racial descent and admixture.

Las castas (The Castes).

Las castas (The Castes). Anonymous, 18th century,

Museo Nacional del Virreinato,

Tepotzotlán, Mexico.

Source: Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Although the Spanish did not importthe full Sistema in all its complexity to Louisiana, Powellnonetheless remarks “the essence of the classificatory regime did gettransferred to Louisiana, implanted by the priests and notaries tasked withverifying individual genealogies and entering their verdicts in registry books segregatedby race” [my italics]. Racial gradations in Louisiana during the Spanishcolonial period included Negro, Mulato, Cuarterón(Quadroon), Grifo (or Grifa), Pardo (“Colored”), and Moreno(“Black”).(5)

What evolved over time from thisbyzantine race-based system of identity was a simpler, more fundamental three-tieredracial order placing enslaved Blacks on the bottom; free, often multiracial (part-White)persons in the middle; and free Whites on top. This framework would in time bereplaced by an even more fundamental binary system that viewed persons aseither “Black” or “White,” with no “in-between” multiracial gradations. Thebinary system arose, strangely enough, even as some continued to refer to a trichotomymade up of “Blancs,” “Noirs” and “Mulâtres.” (Indeed, aslate as 1920 the U.S. Census Bureau classified respondents as Black, White, orMulatto, among other racial/ethnic classes.)(6)

As illustrated by the Code Noirunder French rule and the Sistema de Castas under the Spanish, racializationexisted in Louisiana long before the coming of American rule. This is importantbecause, as noted, it has been argued that “heritage language loss, forcedassimilation into English, and Americanization” shifted “the baseline foridentity in Louisiana . . . from language and culture to race and skin color. .. .” Clearly, the issue is not so clear-cut. If a shift occurred, it may have beenone of degree, with Americans continuing to use race as the major criterion foridentity, albeit perhaps on a larger or more stringent scale than the colonial Frenchand Spanish (though the Spanish, as shown, were fairly stringent when it cameto racial identity).(7)

Powell's The Accidental City (2012)

Powell's The Accidental City (2012)Still, something must account for the presence of race-based identity in early colonial Louisiana. That something, I suggest, was an influence that existed on a vastly larger scale than Louisiana (even as colonial Louisiana covered about a third of the North American continent). I refer to novel if benighted theories of race — part quasi-religious, part pseudo-scientific — that permeated western thought at the time. These theories stemmed from interactions between Europeans and persons of African descent, both in the New World and on the African continent. In short, by the 18th century race as identity was a notion known across the western world, and not at all unique to Louisiana. This explains how Paris and Madrid were able to impose ideas about racial identity not merely on Louisiana, but on colonies throughout their far-flung empires.

This, however, does not mean languageand culture exerted no impact on identity. As they do today, language andculture, like race, ethnicity, religion, and other attributes, served asboundaries, markers, or shibboleths used to inform inclusion as well asexclusion (which, for good or bad, is how group identity works). Yet the riseto dominance of racial identity in colonial Louisiana occurred well before the comingof the American period and its pervasive Americanizing agent, the Englishlanguage.

NOTES

(1) JosephDunn, “A Primer on the Evolution of Creole Identity in Louisiana,” LouisianaPerspectives [blog], 13 February 2018,https://louisianaperspectives.wordpre... 1 May 2024. See also Howard Blount (with Joseph Dunn), “The AcadianExile, Louisiana Creoles, and the Rise of Cajun Branding,” Backroad Planet,6 December 2018,https://backroadplanet.com/acadian-ex... 4 May 2024; Jules Bentley, “Blanc like Me: Cajuns vs. Whiteness,”Antigravity, July 2019, https://antigravitymagazine.com/featu... 4 May 2024.

(2) Merriam-Webster defines racialization as "the act of giving a racial character to someone or something: the process of categorizing, marginalizing, or regarding according to race. . . . : an act or instance of racializing." "Racialization," Merriam-Webster.com, n.d., https://www.merriam-webster.com/dicti..., accessed 8 May 2024.

(3) MichaelT. Pasquier, “Code Noir of Louisiana,” 64 Parishes [Louisiana stateencyclopedia], 6 January 2011,https://64parishes.org/entry/code-noi..., accessed 2 May 2024.

(4) “Louisiana’sCode Noir (1724),” English translation, 64 Parishes, n.d. [October 2013],https://64parishes.org/wp-content/upl... 2 May 2024, see Secs. I, VI, XIII, XV. For the Code in theoriginal French see: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv...

(5) LawrenceN. Powell, The Accidental City: Improvising New Orleans (Cambridge,Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2012), 293, 294, 295; Benjamin Groth, “‘SacredLegalities’: The Indelible and Interconnected Relationship between Baptism andRace in Spanish New Orleans,” Louisiana History 64 (Winter 2023): 48,56.

(6) Powell,Accidental City, 293; Paul Schor, “The Disappearance of the ‘Mulatto’ asthe End of Inquiry into the Composition of the Black Population of the UnitedStates,” Counting Americans: How the US Census Classified the Nation (OxfordUniversity Press, 2017), abstract, July 2017, https://academic.oup.com/book/25441/c... 2 May 2024.

(7) Formore on Americanization, see my book The Cajuns: Americanization of a People(Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2003).

FURTHERREADING

Recent works touching on racialization in colonial Louisiana, as recommended by historian Michael S. Martin:Dewulf,Jeroen. From the Kingdom of Kongo to Congo Square: Kongo Dances and theOrigins of the Mardi Gras Indians (Lafayette: UL Press, 2017).

Groth,Benjamin. “‘Sacred Legalities’: The Indelible and Interconnected Relationship betweenBaptism and Race in Spanish New Orleans,” Louisiana History 64 (Winter 2023):45–82.

Johnson,Jessica Marie. Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in theAtlantic World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020).

Johnson,Rashauna. Slavery’s Metropolis: Unfree Labor in New Orleans during the Ageof Revolutions (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Milne,George. Natchez Country: Indians, Colonists, and the Landscapes of Race inFrench Louisiana (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015).

Wegmann,Andrew N. An American Color: Race and Identity in New Orleans and theAtlantic World (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2022).

White,Sophie. Wild Frenchmen and Frenchified Indians: Material Culture and Race inColonial Louisiana (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012).