Randy Susan Meyers's Blog, page 25

April 22, 2015

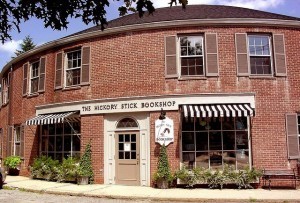

Book Club of the Week: Hickory Stick Bookshop

While not a typical book club, per se, after having the great good luck to be invited to two of their intimate author luncheons, all I can say is: Yes! Yes! Yes! Owner Fran Keilty of The Hickory Stick Bookshop has designed a perfect marriage of delicious food, great readers and hungry authors. What else does together so well? (Yes, after being alone in our sweat pants, eating cereal and milk for as many as three meals a day (oops, is that only me? TMI?) what could make me happier than a bookstore in a gorgeous setting in Connecticut, artfully prepared real food and talking to sharp fun women who love to read?

And all this for the price of a book? That’s the price of admission. It’s a gift to the author and the reader, as everyone walks out with the author’s novel, a satisfied appetite and, in the case of this author, a much lighter wallet—because the Hickory Stick Bookshop is so completely wonderful (books, gifts, chocolate) that I walked out having bought a huge bag of gifts for my family. And for me.

Wait . . . is this part of the Hickory Stick Bookshop plan?

Either way, I love the place. Please have me back for my next book, Fran?

April 14, 2015

Book Club of the Week: Club Red in Braintree

Club Red in Braintree MA

One of the best parts of being an author is getting to eat cake . . . wait a minute, I meant visiting book groups. Who also happen to have the best cake, gossip, wine & ideas for new books to read. Of course, when I meet with a group by Skype I don’t get to drink the wine, but I do get to be invited into beautiful living rooms all over the country.

This weeks club, Club Red, has women from many towns in Massachusetts, because the club glue, club leader, and all-around incredibly brilliant woman, Christine Powers, draws friends from all over—they even have a ‘sister’ club in England. And a logo!

With Christine Powers

I’ve visited with Club Red for my last two books and am crossing my fingers I get to be with them for my next one. They made me (and my husband—who is always kind enough to give me a ride when I’m not up to driving) feel truly welcome.

Also, this is the only group for whom I made a book game–when challenged to match the previous author, Thomas Donahue, who brought ice cream from his shop.

April 10, 2015

Raised by Books

Perhaps every insatiable reader has a book so thoroughly imprinted at a vulnerable age, that they carry those characters like family of the heart forever. Some marked me for horror. IN COLD BLOOD assured I’d never stay alone in a country house. Others taught me about the awful mixes of fear, revulsion, and sadness we can barely tolerate, like OUR GUYS, by Bernard Lefkowitz, a book which assured I’d look at any boy my daughters dated with more judgment than I wanted.

And some taught me faith in the future.

A TREE GROWS IN BROOKLYN by Betty Smith was the only bible I ever owned, my personal talisman of hopefulness. Perhaps it was partially because, though in different times, like Francie, I grew up in Brooklyn and I missed my father. He, like Francie’s, ran from by what we now call self-medicating (and what Francie’s mother and mine, called nothing, because who talked about it in Brooklyn?) And then they escaped forever by dying young.

Like Francie, I’d experienced the horror of old men liking young girls, of having an aunt I worshipped, and a school I hated. Each time I read A TREE GROWS IN BROOKLYN I was struck anew by how this author knew so much and dared to write it.

That’s the beauty of books. They don’t just transport, they heal, they teach, and they soothe. On the loneliest of days, they ask no more than picking them up. In the worst of times, they stand by. And those old friends—like Francie Nolan—they don’t only offer a ‘you are not alone,’ they provide you with the promise that there will be a way out. Maybe not the happiest ending in the world, but at least you knew you could end strong at the broken places.

Thank you, Francie Nolan.

Bless you, Betty Smith.

March 19, 2015

How To Use Critique & Advice

When it comes to criticism from my writer’s group, I need to hear or read the same idea two, three, or four times before I can incorporate it into my work-in-progress. Months after arguing with my fellow writers, (so blind! so ignorant!) I re-read their notes and am struck by wisdom where I formerly saw idiocy.

How do you decide what to keep and what to leave behind from critiques? One sure bet is the power of all yea or nay. I can’t say it any better than Stephen Koch did in A Guide to the Craft of Fiction:

“When a value judgment is unanimous, be it favorable or unfavorable, something important was said. It is, of course, possible — unlikely but possible — that you are right and everyone else is wrong ... But usually something everybody dislikes needs fixing. Unanimity is rare.”

An all thumbs up or down is easy to use, but how do you assimilate varied opinions, let alone chose what is useful? H.G Wells noted: “No passion in the world is equal to the passion to alter someone else’s draft.”

I give deeper consideration to the comments of those with whose responses I agreed with when critiquing other’s work. If I thought they were so spot-on when deconstructing other’s work, chances are pretty good they’re on target with mine (no matter how much I try to convince myself otherwise.)

If you’re in a writing workshop, by the time you’ve finished your book you’ve collected a notebook of criticism and compliments. Be wise with both. Be humble and rent all advice even if you don’t buy it. Critique has saved me from simpy, saccharine, and sentimental work. (Also, wise-alecky.)

On the other hand, the worst, sent me into a fog of depression. One particular person sent me into a long period of avoiding the page. Beware of cutting critique meant to show how very clever is the person criticizing. Good advice comes from a well of appreciation of your intent and should be without bitterness or denigration.

As for compliments, they’re lovely! Just beware of drinking from that particular pitcher too often or deeply. If it is your friends and family who are your readers, they can be bewitched by every word because they’re yours and they love you. Many grains of salt can be useful.

Somewhere in the middle you find your answers. Some critique may be veiled insult. Sometimes praise is the easiest way for folks to respond (those who’d rather be false than take a chance of hurting someone’s feelings,) however in all circumstances other reader’s eyes are needed.

Find the writer’s group that works for you. Do not settle for working with folks who are trying to re-write your work, jockey for position, or show how smart they are by riffing on other’s writing. Find writing friends who believe they are in a mutual mission to raise everyone’s writing to the highest level.

Waiting until the end of my draft before incorporating ideas from my writing group works best for me. Rushing to change characters, plot, or style too soon doesn’t allow me to wash the ideas through my own beliefs. Waiting allows me to take in criticism. When I look at critique notes weeks or even months after receiving them, they make more sense. My instinct to fight is gone. I become a believer of their ideas or I become stronger in my own gut. I no longer have to say, “But you don’t understand!”

I remember that having to explain my work means something is wrong. Your work must always stand on its own pages. After all, you’ll never get to explain anything to the reader who buys your book.

March 14, 2015

Writer’s Groups: Don’t Drink and Read

“No child could possibly be happy about her father moving out!”

The above was said to me at a writing workshop, in a discussion about my then unpublished novel (it eventually became The Murderer’s Daughters.) The ‘child’ in question lived with a selfish, sarcastic, angry mother and an oft-drunk “mooning around” father. In the questioned scene this 10-year-old protagonist voices guilty relief at finding a less troubling atmosphere after her father moved out. A workshop member, adamant in his belief that no child would ever feel relief at her father leaving the house, expressed insistence bordering on disbelief (that I would write such an emotion)! bordering on disdain (that I would be able to dredge up such an emotion)!

Really?

Precious minutes slipped away as the group debated this point. The workshop operated under the “in-the-box” silenced writer rule (which most of the time I agree with) so I could only listen as time ticked by and the debate raged.

Should this point have been up for grabs? (And should anyone wag their finger when giving critique?) This is problem I’ve found in writing workshops. Let’s call it the ‘scrim’ factor. Aside from the craft of the work, the plotting, the plausibility, believable motives, and the ability of the writer to engender suspension-of-disbelief, when (if ever) is a character’s ‘belief system’ up for judgment — especially if the judgment is made based on the belief system of a fellow workshop member?

Never.

That’s only my opinion, but one I hold dear. A writer’s workshop is not there to tell you:

1. Your character would be better served as a secretary than as a doctor. They can say you didn’t write a believable doctor. They can say they didn’t believe someone with an IQ of seventy could become a doctor. Then, it’s up to you to make the reader believe.

When stuck in the ‘scrim’ factor, your fellow-workshop members try to revise your manuscript to live within parameters in which they are comfortable.

2. Your character wouldn’t: give up a child, become president, cook roast chicken. The workshop is there to let you know if they believed your character (the vegan) would suddenly roast the chicken, not if they would ever roast.

Beware workshops that become arbiters of morality and comfort levels, rather than sharp-eyed watchers of motive, plotting, and plodding prose. One wants a workshop that scrawls MEGO (my eyes glaze over) on the page, not one that says, “women don’t usually change the oil in the car.”

If they do mention the oil, your writerly job is to discern whether your workshop buddy meant that women don’t change oil, or they didn’t believe your particular woman character would change oil.

In one workshop the leader (making this problem more egregious for me — a neophyte) went on a rant about the non-political nature of my character. Why wasn’t she out making the world a better place, rather than worrying about having sex with her neighbor?

Did she mean I wasn’t writing the book she wanted to read?

I’ve been in workshops where men have been lectured about how disrespectful their characters were to women. I probably even got heated up enough to agree and join in — Yeah! He was awful! We forgot the author was building a character, not our new boyfriend.

The thing is this: to write well, you have to first write terribly — allowing those crappy first drafts to get out. You need this awful draft — otherwise what would you have to revise and, eventually, make wonderful? The danger in writer’s workshops is writing for the others, writing for the workshop, rather than writing for your eventual audience:

Today, writers want to impress other writers. — Paulo Coelho

I believe in writer’s workshops and groups. Without the best of them, I’d have a weaker novel. But without the worst of them, I’d have built that better novel faster.

Use workshops wisely, taking the best and leaving the rest. Take off blinders and examine your motives and those of members. Purity of member’s motives can never be guaranteed. Some are angels leading to Pulitzers — some are devils sent to torture us. Use guidelines:

1. Are you coming with the secret belief that you will be the one “perfect nothing-needs-changing” writer? They will be astonished by my piece! Not going to happen my friend. Not to you. Not to me. Not even to Marilyn Robinson should she wander in from the Iowa Writer’s Workshop (OK, maybe her.)

If what you seek is pure approbation and amazement at your genius, send your story to your family.

2. Beware of hardening yourself to protect your ego. Even the smartest critique stings. It is common to hate, really hate, someone who points out that five backflashes in a row might leave the reader confused. I make a deal with myself when I’m ‘up’ in my writer’s group. I am allowed to think everyone is stupid for 10 minutes. Then I have to consider their ideas. I don’t have to buy them, but I must rent them.

3. Beware of drinking the Kool-aid of love. Or the river of hate. My first time ever at a writer’s group was at a local adult education venue. “Brilliant!” the teacher told me. (It wasn’t.) A few years later, at another venue, I was told how much my character sucked — that she defined worthless. (She wasn’t.)

Teachers and groups often have cultures that overshadow reason. Listen hard to what members say about other’s books — especially books about which you feel strongly one way or another. If the general consensus (there are always outliers) makes sense for those books, take what they say about your book (good and bad) seriously.

4. Critique benefits from compassion. At an education conference, an expert (whose opinion I value) said a version of the following: “Why do we get mad at students for not knowing the answers? Isn’t that why we’re there? To teach them?” Those who sneer at your work are not helping. Don’t fall under the sway of a writer-bully.

5. Yes, Virginia, there is jealousy in groups, and it can be poisonous. Sometimes it comes from the leader, sometimes it comes from members, and sometimes it comes from our own gnarled little hearts. Accept it, don’t act on it, and move on. Carol Burnett, when talking about the parts she didn’t get, said it well: “It wasn’t my turn.”

6. Don’t let the group write your book. Look around the room. Does one choose Gillian Flynn as their favorite writer, another Ian Rankin, and a third Virginia Woolf? Will they all perhaps, subconsciously, push your romantic comedy towards the twisted, or encourage your historical fiction to become a ghost story? Listen for majority opinions (if everyone found those back flashes unintelligible, perhaps they are. If the person who only likes terse experimental fiction work harps on it, consider the source.)

Your book needs your passion — not the reduction of a committee.

7. Be cautious of the five-page-a-week workshops. It has been my experience that a group which looks at a large chunk of one (or two) writer’s work in one night benefits more than those that read a few pages of all. Reasons? Reading weekly installments of five pages a week leaves the group more likely to want to be in on writing the next scene — thus making writing by committee more likely.

8. If you are ‘advanced’ consider an ‘entire book’ writer’s group. My current (and perfect) group will do the entire book. We meet less often (sometimes once a month, sometimes less often) and read more. Our goals are getting a read on the entire arc of the novel and it’s been invaluable.

9. Fresh work might not be the best for critique groups. I believe you should let your work cool down a bit before sending it to anyone’s eyes. Going through at least one revision is helpful — this allows you to hear yourself before the committee voice rushes in.

10. Don’t drink. That’s a rule I use for myself. I believe alcohol engenders stupidity in all things. Wine is for partying, relaxing, or watching television. Not for helping each other reach full writing potential.

March 11, 2015

How Besteller Lists Are Made, Authors, & A Bit of Crazy

“My agent and editor started talking about ‘the list’ from the start, virtually ensuring that I’d consider myself a failure if I didn’t make it. At first, when they talked about it, I didn’t even know what “the list” was—didn’t know there was truly only one ‘list.’

“You must stay drunk on writing so reality cannot destroy you.” Ray Bradbury

The New York Times Bestseller list (AKA “the list”) is the writer’s holy grail. Despite being rife with methodology that many claim to comprehend, but none can swear to understanding; despite not being a measure of selling the most books, but of selling the most books that week at those stores, every author wants the honor.

And yet, because it is considered so terribly jejune to admit that you want it, most of us toss our heads and roll our eyes when our moms and cousins ask one of these hated questions:

* Are you going to be on Oprah? (This even after her show ended.)

* Is your book going to be made into a movie?

* Are you a NYT Bestseller?

Only a few brave souls will go on record with their feelings about being (or not) a bestseller. (Which is why many of the authors here are speaking off the record below, but they are all published (most multiple times) authors from “Big 5” houses.

One anonymous author admitted to being ecstatic, even as she was a bit unsure how it all happened:

“When my first book hit the NYT trade list, I felt like I’d been handed the moon. I couldn’t believe there were all those strangers out there reading my little book. Then, my second novel debuted at number five on the NYT hardcover list, a fact we learned days before it even came out—back when no one had yet bought or read it. Crazy. Magical math? ESP? Barnes and Noble omnipotence? (It was a B&N Recommends.) I still have no idea. The List moves in mysterious ways.” Anon

Bestselling author Tish Cohen, a finalist for the Commonwealth Writer’s Prize, gave her feelings about “the list” in this succinct honest statement:

“For me, I haven’t made it until I hit the NYT list. Sigh?”

Ah, “the list.”

C.W. Gornter, celebrated author of six novels said:

“I think the list creates a feeling of have or have-not among the writing community; as authors, we vie for it, long for it, and can find ourselves sorely disappointed and disillusioned when we don’t achieve it, without understanding the numerous factors behind it over which we have no control.

To me personally, the list reflects more of a popularity contest, often engineered by publishers to gild chosen titles. It does not reflect the particular merits of any book—though sometimes, it does—but rather the fact that for various reasons that remain a mystery to the majority of writers, the publisher has decided to allocate monetary resources to create buzz for said book.

Nor does the lack of transparency as to how the list is actually achieved (last I heard, it was not based on Bookscan numbers) make deciphering it any easier. To want to be on the list is to be expected: it signals to the world at large that you are a success. But success in writing can be measured by more than that. I have never made the list, but make quite a good living with my writing. Would I welcome the chance to be on it? Absolutely. Will my career implode or will I plunge into despair if I don’t? No.”

Killer of dreams, maker of literary royalty: the road to the list is strewn with broken hearts. Two words whispered, fought over, dreamed of, and inducing more jealousy than Swiss bank accounts. I’ve heard rumors since I published my first book:

“You know, I should have been on the list—I sold more books than number 10 last week.”

How did he know that?

“If you’re over number 15 in the hardcover list, you don’t have the right to call yourself a NYT bestseller.”

Where could I get a list of these rules?

“You know, publishers pick the books they want to be on the list and then make it happen.”

Really? How did one get anointed?

Was any of this true? God knows it’s seductive, this insider baseball: The list. The list. The list. Who’s on, who’s not—who gets to have those golden words, New York Times Bestseller, plastered on their cover?International bestselling author Karen Essex has a simple answer to what being a bestseller means:

“You can finally prove to your parents that you were correct in not going to law school.”

Few, almost none, know the secrets to entering the gray lady’s scroll, while other bestselling lists are less opaque. Everyone agrees that being on “the list” is like winning the book beauty pageant, but no one will reveal the trade secrets that make the algorithm building “the list” Most agree it is a curated one—not one made up of pure math. There are list rules and strictures within “The List.”

According to the site Dear Author. “Each publisher house has its own standard for when the moniker “Bestseller” can be imprinted on the front of a cover. For some houses, the standard is to say “NYT Bestselling author of Book A”. Some houses won’t allow authors to put the label on the book unless they make the print list of the Times or USA Today. For example, there is an “extended” NY Times list and if you make it on there more than once, a publisher might allow the author to put “NY Times Bestselling Author” on the cover. In other words, at some houses, Snooki wouldn’t get to call herself a NY Times Bestselling Author.”

One online writers group broke into virtual fisticuffs over this, with one author declaring her publisher’s method (no “extended” NY Times list” authors allowed to use the moniker,) versus those whose broader-minded publishers allowed all authors making any part of the list (print, digital, extended) to use the lable publicly.

It got ugly. After fighting to reach the highest rungs of a hierarchy, some want to kick down the climbers.

There’s no inoculation to list fever, and there are far more bestselling lists than ‘the list’: Wall Street Journal, USA Today, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Indiebound for a start. List makers range in the information given out on how data is collected—below is information listed on their websites:

NYT Bestsellers Data Collection: “The universe of print book dealers is well established, and sales of print titles are statistically weighted to represent all outlets nationwide. The universe of e-book publishers and vendors is rapidly emerging, and until the industry is settled sales of e-books will not be weighted . . . The appearance of a ranked title reflects the fact that sales data from reporting vendors has been provided to The Times and has satisfied commonly accepted industry standards of universal identification (such as ISBN13 and EISBN13 codes). Publishers and vendors of all ranked titles conformed in timely fashion to The New York Times Best Seller Lists requirement to allow for independent corroboration of sales for that week.”

USA Today Bestsellers Data Collection: “Methodology: Each week, USA TODAY collects sales data from booksellers representing a variety of outlets: bookstore chains, independent bookstores, mass merchandisers and online retailers. Using that data, we determine the week’s 150 top-selling titles. The first 50 are published in the print version of USA TODAY each Thursday, and the top 150 are published on the USA TODAY website. Each week’s analysis reflects sales of about 2.5 million books at about 7,000 physical retail outlets in addition to books sold online. Book formats and rankings: USA TODAY’s Best-Selling Books list ranks titles regardless of format. Each week, for each title, available sales of hardcover, paperback and e-book versions are combined. If, for example, Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice sells copies in hardcover, paperback and e-book during a particular week, sales from each format would be reflected in that week’s ranking. The ISBN for the format that sold the most copies is presented with each list entry.”

Amazon Top 100 Bestsellers Data Collection: “About Best Sellers in Books: These lists, updated hourly, contain best-selling items in books. Here you can discover the best books in Amazon Best Sellers, and find the top 100 most popular Amazon books.”

Barnes & Noble Bestsellers Data Collection:” B&N Top 100: Book Bestsellers”

Wall Street Journal Bestsellers Data Collection: “With data from Nielsen BookScan”

Indiebound National Indie Bestsellers: “Based on sales in independent bookstores across America. The Indie Bestseller Lists put the diversity of America’s independent bookstores on display. It’s produced just two days after the end of the sales week, and is the most current snapshot of what’s selling in indie bookstores nationwide.”

There is no place one can go and get a true list of how, in particular, the New York Times list is made—but, according to the many articles I read, and authors I’ve spoken with, the following seem to be widely accepted, though none can be backed this up with hard sourced fact:

1. “The list” captures the velocity of a give week, thus a book having high sales for one week can make the list, even while another book selling an overall far higher number for that month does not make the list.

2. There are stores deemed “New York Times Reporting” stores. Supposedly, some publishers and authors, aware of these stores will go all out to hit them within one week. Thus, gathering the velocity.

3. According to Wikopedia (yes, not always accurate—but this story of ‘leading data collection’ is often reported): The Times provides booksellers with a form containing a list of books it believes might be bestsellers, to check off, with an alternative “Other” column to fill in manually.It’s been criticized as a leading technique to create a best-seller list based on books the Times thinks might be included.

According to the NYT “Readers Representative” (data is from 2009) “the above is not quite accurate. “Another misconception is that booksellers are surveyed only on a list of titles determined by publishers’ shipments, keeping “sleeper” books — distributed in smaller numbers — off the list. That is not the way it happens. Instead, some companies dump all of their book sales to The Times, while others fill out an online form based on the previous week’s best sellers and including space for unlisted books that have sold well.”

4. Some try to manipulate lists by bulk buying—which is frowned upon (more below) and often found out—or by underpricing. I’m unclear on exactly how underpricing works, but it’s along the lies of giant retailer (such as Amazon) offering or agreeing to lower the price for an E-book (such as lowering the price from 11.99 to 1.99.) The author, friends of the author, etc., all shout out the bargain price. Then, the book, at this low price, shoots up the Amazon E-book list, enabling authors to write phrases such as “Number-one bestselling Kindle Kabbalah mystery!” Often an author will hit “the list” for a week through this method, and thus be forever deemed a “New York Times Bestseller. Then this book drops to it’s usual ranking.

5. There are services and sites devoted to quid-pro-quo for authors, meant to skew sales and rankings, and preying on self-published authors. And then there is the straight-up buy-in, reported on by Jeffrey Trachtenberg, Wall Street Journal in the article: “The Mystery of the Book Sales Spike: How Are Some Authors Landing On Best-Seller Lists? They’re Buying Their Way”. According to WSJ, “authors hired a marketing firm that purchased books ahead of publication date, creating a spike in sales that landed titles on the lists. The marketing firm, San Diego-based ResultSource, charges thousands of dollars for its services in addition to the cost of the books, according to authors interviewed.”

One author using the service said she didn’t know how ResultSource managed to skew sales so that the books landed on bestseller lists. “It’s a secret sauce,” she said.

Hmm… the last time I read the claim of “secret sauce” as the reason for a business success, it was attributed to Bernie Madoff.

After reading reams of supposed ‘inside scoops,’ I still can’t figure out a take-away. It seems too facile to deem anything (except buying one’s way onto a list) as something deserving of finger wagging. Jealousy and hope make for odd stews. Knowing insider-baseball can be as much loss of innocence as information-is-power (like learning the genesis of bright purple blurbs, or finding out the truth of a publisher’s reassurance that “you’ll have a social-media campaign!” means “good luck tweeting, honey.”

One author friend, one with his head tied on especially straight and smart, said this when I gathered quotes for this essay:

Marketing and sales are not my area of expertise. I do what I can and will be pleased, of course, if “The List” happens to me. But I focus on what I can control, the quality of my work. Anon

In the end, yes, Virginia, there is truth in basic advice, it does come down to living by those axioms which keep us honest, even as we pray to be touched by the Fairy Godmother of “The List.”

On the other hand, there isn’t a damn thing wrong with dreaming.

“I don’t care who you are. When you sit down to write the first page of your screenplay, in your head, you’re also writing your Oscar acceptance speech.” Nora Ephron

We have a hundred sides fighting inside us. We are like salt and snow.

Checking the list, hoping a frenemy didn’t make it. Being truly grateful at how deep a lens your friend brings to a story, and then feeling snarled and small when he hits “the list” and it seemed like a little part of you just died. We’re both parts and it’s okay to admit to the green monster in the shriveled corners of our hearts, but we must be on guard against being overtaken by coldness. If we’re not willing to appreciate the beauty brought forth by others, it’s unlikely we’ll be able to write our own.

(first published Jan 2014)

March 2, 2015

Debut Books by Writers Over 40

(first published in 2011)

Originally, I tried to resist writing this—especially after my plea against categorizing authors. Plus, so many of us hide our age in this world of never-get-old, unearthing this information, even in our Googlized world, was difficult.

But when , along with the plethora of lists of writers under 40, I was faced with the declaration that, as headlined in a Guardian UK article about writers, ‘Let’s Face It, After 40 You’re Past It.”

Then I read Sam Tanenhaus opine in the New York Times that there was “an essential truth about fiction writers: They often compose their best and most lasting work when they are young. “There’s something very misleading about the literary culture that looks at writers in their 30s and calls them ‘budding’ or ‘promising,’ when in fact they’re peaking.”

Thus, in the interest not of division, but of keeping up the flagging spirits of those who don’t want to be pushed out on the ice floe until after publishing all those words jangling in their head, I present 40+++ 0ver 40, updated once again.

Charlotte Rogan was 57 when she published Lifeboat to great acclaim. Erika Dreifus launched the outstanding short story collection Quiet Americans at the age of 41. Judy Merrill Larsen’s first well-received novel All The Numbers came out when Judy was 46.

Donald Ray Pollock was 55 when his short stories debuted, his novel The Devil All The Time launched three years later.

Laura Harrington launched her debut novel, Alice Bliss, when she was 58, after years as a playwright, lyricist and librettist. Shelter Me, Juliette Fay’s award-winning first novel came out when she was 45 years old. The Marquis de Sade wrote his first novel, Justine, at the age of 47.

Paul Harding, author of Tinkers, won the 2010 Pulitzer Prize with his debut novel, published when he was 42. Robin Black, author of If I Loved You I Would Tell you this, was 48 when she debuted this year. Holly LeCraw published her debut novel The Swimming Pool at 43. Julia Glass was in her early 40s when she published Three Junes. Charles Bukowski’s first novel, Post Office, was published at 49. James Michner’s first book, Tales of the South Pacific was published when he was forty—he went on to publish over 40 titles. Sherwood Anderson, author of Winesburg, Ohio published his first novel at the age of 40. Amy Mackinnon debuted Tethered in her 4o’s.

Henry Miller’s first published book, Tropic of Capricorn, was released when he was over forty. Tillie Olsen published Tell Me A Riddle just shy of 50. Edward P Jones was 41 when his first book Lost In The City came out. Claire Cook published her first novel at age 45. Chris Abouzied published his first novel Anatopsis at 46. Kylie Ladd was 41 when her debut, After The Fall, was published.

Lynne Griffin published her first novel, Life Without Summer at 49. Elizabeth Strout’s first novel Amy & Isabel debuted when she was 42. MJ Rose first novel came out when she was in her mid forties. Melanie Benjamin was 42 when she debuted. Therese Fowler was forty exactly when Souvenir debuted. Julie Wu’s about-to-debut novel The Third Son will launch when she is 46.

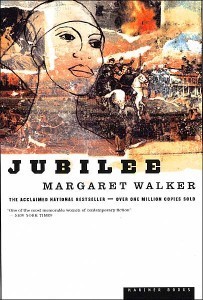

Margaret Walker wrote Jubilee, her only novel at 51. Raymond Chandler debuted at 51 with The Big Sleep. Belva Plain published her first novel, Evergreen, at 50. Alex Haley published his debut novel Roots when he was 55. (His first book, the nonfiction The Autobiography of Malcolm X was published when he was in his mid-forties.) Jon Clinch debuted with Finn at age 52. In 2010 his wife Wendy Clinch published Double Black.

Also in 2010 Iris Gomez published Try To Remember in her fifties, as did Joseph Wallace with Diamond Ruby, and I published The Murderer’s Daughters at 57. Sue Monk Kidd was 54 when she debuted The Secret Life of Bees. Annie Proulx’s first novel, Postcards, was published when she was 57. Jeanne Ray published debut, Julie and Romeo in her fifties.

George Elliot’s first novel, Adam Bede, debuted when Elliot turned 50. Isak Dineson’s first, Seven Gothic Tales came out when she turned 50. Hallie Ephron author of Never Tell A Lie began publishing fiction after fifty. Richard Adams debuted with Watership Down at 52.

Laura Ingalls Wilder published her first novel (beginning the Little House series) at 65. Harriet Doerr won the National Book Award, for Stones for Ibarra, written when she was 74. Katherine Anne Porter published her only novel, Ship of Fools, at age 72. EJ Knapp just debuted Stealing The Marbles, saying “I’m so far past forty I can’t remember it anymore.” Norman McLean wrote A River Runs Through It at age 74. Amy Sue Nathan will be 49 when The Glass Wives releases in May.

Lise Saffran released Juno’s Daughters when she was 46. Astrid and Veronika was published when Linda Olsson was 56. Joan Medlicott published The Ladies of Covington Send Their Love when she was 65. And she published 6 books after that. Sally Koslow’s first novel Little Pink Slips was written when she was over 50.

Ellen Meeropol‘s first novel House Arrest, came out two months before her 65th birthday.” Karen LaFreya Simpson will be 55 when her first novel Act of Grace debuts next year and Nichole Bernier was 44 when The Unfinished Live of Elizabeth D published in 2012. Yes, that’s my answer, Ellen. We all count.

This is only a list of first novels. Compiling lists of bestselling, Pulitzer Prize winning, Orange Prize winning, etc. books written after the age of 40—that will take several essays.

Kathy Handley’s debut collection of short stories, A World of Love and Envy launched when she was 71.

Dyan deNapoli’s story of rescuing penguins (nonfiction) The Great Penguin Rescue came out when she was 49.

James Arruda Henry learned to read and write when he was in his mid-nineties. He published his autobiography In A Fisherman’s Language at the age of 98–going on to have it be a bestseller in his town and being featured in People.

Lydia Netzer’s novel Shine Shine Shine is being launched tomorrow. She is forty years old.

Sarah Pinneo launched her novel Julia’s Child when she was forty (ten years later than she’d planned.)

C.W. Gortner was 44 at the publication of his first novel, The Last Queen in 2008–he has gone on to publish 3 more as of June 2012.

Penelope Fitzgerald published her first novel The Golden Child in 1977, at the age of 60. She went on to win the Booker Prize in 1979 for Offshore.

I was told today by the incredibly talented Elizabeth McCracken that Bruce Holbert, author of the just launched (and much lauded) Lonesome Animals deserves a place here–though I am not sure of his exact age.

Kerry Schafer‘s Between, came out from Ace in January 2013. Jessica Keener’s novel, Night Swim, launched when she was 57. Becalmed will debut when Normandie Fischer is “so far past 40 that she can’t remember it.”

In the UK, Dorothea Tanning published her first novel, Chasm: A Weekend (also surrealist) by Virago when Tanning was 93 years old Harriet Doerr published her first novel, Stones for Ibarra, at age 73. She was awarded a National Book Award for this work and Helen Hoover Santmyer published the bestselling And Ladies of the Club at age 88.

February 23, 2015

Micro-Inequality: Why Review Equality Matters

The first time I looked for a job, Help Wanted was divided into three sections: Men, Women, and General. If memory serves me (I doubt it) men’s jobs were the professional ones, women’s were the handmaiden ones, and general included dishwashers and drivers.

Trust me, the career paths were separate and not equal.

I remembered those categories while writing this post (which I wish I wasn’t writing) when I came across the terms microinequity and micro-affirmation, first coined by Mary Rowe, who defined micro-inequities as “apparently small events which are often ephemeral and hard-to-prove, events which are covert, often unintentional, frequently unrecognized by the perpetrator, which occur wherever people are perceived to be ‘different.’”

A micro-affirmation, in Rowe’s writing, is the reverse phenomenon. “Micro-affirmations are subtle or apparently small acknowledgements of a person’s value and accomplishments. They may take the shape of public recognition of the person, “opening a door,” referring positively to the work of a person, commending someone on the spot, or making a happy introduction. Apparently “small” affirmations form the basis of successful mentoring, successful colleagueships and of most caring relationships. They may lead to greater self-esteem and improved performance.”

On the front page of today’s Boston Sunday Globe is an article entitled: “About-face at Harvard: A push is on to make the portraits on the walls — white men, almost all — reflect the diverse face of the university today.”

In this article, Tracy Jan reports: “There’s a significance to portraiture, in demonstrating to people of all backgrounds that their presence and contribution are appreciated,’’ said Dr. S. Allen Counter, director of The Harvard Foundation for Intercultural and Race Relations, which for eight years has been quietly commissioning portraits of distinguished minorities and women to hang in Harvard’s hallowed halls.

“We simply wish to place portraits of persons of color and others who’ve served Harvard among the panoply of portraits that already exists,’’ Counter said. “We will not displace any portrait, just simply add to them.’’

A micro-affirmation of great proportions.

Also in today’s Sunday Boston Globe are four full reviews of books by men, no full reviews of books by women. (“Short Takes,” a column of brief reviews covered two books by women and one by a man.) Monday through Saturday, during the past three weeks, there were 17 reviews of books by men and one review of a book by a woman.

Microinequality.

Last weekend, when I briefly touched on this on my Facebook page, a friend asked “but how many books by men vs. women are published?” I’d love to know and spent too many should-be-writing hours looking, but I wonder if the question and answer would beget a chicken-egg quandary. In addition, there is the question of equality in marketing, book covers, etc—a topic well covered by Lionel Shriver (winner of the 2005 Orange Prize and a finalist for the 2010 National Book Awards).

To repeat: I didn’t want to write this post. I’m frightened of writing this post (but impulse and passion control has never been my strongest suit). I’ve had very fair shakes from newspapers and radio—great reviews and mentions in The Boston Globe, The NYT, and NPR (referenced below). They are my main and beloved news sources. I’ve subscribed to both for enough years to have bought a shiny new car.

The last thing in the world I want is to bite the hand . . . but I have two daughters and a tiny granddaughter.

When women write about this phenomenon, they can usually count on the eye-rolling responses, the sigh that says “isn’t this topic getting tedious” and wild assertions that women run publishing. Disparaging responses such as, “Unfortunately, what gets lost in this smokescreen is the more important (and dangerously tricky) question of “Why isn’t there more serious literary fiction being published by women?”” by bloggers such as The Grumbler who assert that women don’t deserve reviews in serious media.

Thankfully, I also find great hope. The Economist took a sharp look at this question, noting how reviews written will translate to books read, writing, “All readers are gently trained to empathise with white male narrators.”

In private, most female writers talk about mainstream media (and often non-mainstream media) review numbers, but we’re terrified to go public, easily imagining the scenario that could result:

“Oh, so you want a review, do you?” asks Important Editor after hearing about your . . . whining. “Fine. Here’s your review. Read it and weep.”

Do I truly think an editor would be that crass? No, but there is that ingrained awful fear about not being a good girl. About being called a whiner, a baby, and a jealous harpy. When Jennifer Weiner and Jodie Picoult talked about this they were accused of ugly motives as well as having their talent denigrated, and they’re best-selling authors. Thus, why would any woman want to go there? Why do I?

Would it help if men joined in this?

Does it matter? Does it matter that in 2009, Publishers Weekly didn’t include a single woman in their list of the Top 10 Books of 2009?

Carolyn Kellog writing in the LA Times on Dick Meyer’s NPR list of 100 Best Books of the Twentieth Century (a list that included only 7 books written by women) quotes Meyer as saying “My taste is probably medium-brow, male and parochial in many ways. Tough. It’s my list.” In response, Kellog asks, “but it begs the question: can one imagine a female writing for NPR having a nearly all female Best Books List?”

Does this matter? According to NPR, “As NPR’s executive editor, Dick Meyer shapes and oversees NPR’s worldwide news operation on-air and online. Meyer plays a critical role in integrating NPR’s on-air sound with its dynamic and growing online and mobile platforms, and in fostering the organization’s distinctive storytelling and enterprise reporting.”

That sounds to me as though his opinion very much matters.

The number of book reviews of women is indicative of a micro inequality, which piles up to matter quite a bit. Julianna Baggot captured it well, writing in the Washington Post, “So how do we strip away our prejudice? First, we have to see prejudice. The top prizes’ discrimination against women has been largely ignored. We can’t ignore it any longer.”

Some not only ignore it, they deny it. Writing about this issue, Slate.com wrote: “The bookish blogosphere continues to debate whether the New York Times—and, by extension, other cultural gatekeepers—really does give white male fiction writers preferential coverage over authors of the distaff and ethnic variety . . . So we decided to gather some statistics in order to determine whether the Times’ book pages really are a boys’ club.”

You can download the actual spreadsheet at Slate, but their conclusions boiled down to this: Of the 545 books reviewed in the NYT between June 29, 2008 and Aug. 27, 2010:

—338 were written by men (62 percent of the total)

—207 were written by women (38 percent of the total)

Of the 101 books that received two reviews in that period:

—72 were written by men (71 percent)

—29 were written by women (29 percent)

In 2002, the Complete Review of Books admirably took themselves to task for their miserable coverage of books written by women authors at 12.61%.

During that same period, they examined the track record of major literary papers of record:

Reviews of Books by Women

Publication

Total

Percent

London Review of Books

40

15.00

The NY Review of Books

76

18.42

The NY Times Book Review

120

30.00

Times Literary Supplement

130

24.60

.

.

.

TOTAL

366

24.04

If women’s books aren’t reviewed, when women’s books are declared “less literary, and when women’s books on family are declared women’s fiction, while men’s domestic books are declared brave and eye-opening, it adds many pounds to the micro-inequality pile.

Do we care enough to fight about this?

I think it comes down to this: people in power rarely give up power voluntarily; sometimes they don’t even recognize that they have the power. I think it’s up to us to join the brave authors like Julianna Baggot, Jennifer Weiner, Jodi Picoult, and Lionel Shriver, who are willing to talk about this. We need to tell ourselves and ask the men who are our friends, who are the fathers of daughters and father of sons who will marry daughters, that it’s time.

It’s time to rid ourselves of micro-indignity, and remember that men and women each hold up half the the sky.

January 30, 2015

Soothing Words For Bad Reviews

It was the best of times; it was the worst of times.

For every moment of awe a writer has at seeing her book on a shelf, at being told by readers they found comfort they found in your words, for each time you visit a warm and loving book club, there come the time when you read the word “blech” in a reader’s review. It’s part of the business and there’s no answer except chocolate and wine. It hurts. Writers from NYT bestsellers to just-on-the-shelves authors must find ways to soothe themselves through the pain.

I come bearing brownies and a shot of tequila. The comfort needed for times when nothing but schadenfreude will do. I would offer mead to Shakespeare, had he lived in the time of Amazon and read this review of Romeo and Juliet:

“As far as I’m concerned, the only good thing about “Romeo and Juliet” is that it spawned the plot for “West Side Story,” which, although laden with cheese, doeshighlight some of the more noble facets of the human character (along the less noble) and features some wonderful music. “Romeo and Juliet” will, however, simply annoy anyone with half a brain.”

A newly published author-friend privately spilled her horror (to a group of not-surprised writers) when, after a spate of reader-love, she found this on a popular book site: “To those who loved this book, may we never meet on subway, train, or plane.”

Shock usually follows the first angry reader review. I don’t think they’re as hurtful as critical professional reviews, but they go where NYT reviewers would never tread.

The not-surprised writers, as always, gathered around the newly launched author referenced above, and shared their own hurtful reader reviews.:

“Someone once hated one of my books so much that she made a custom e-stamp that said, “This book is so bad it should be banned from the face of the earth.”

“There is just no level on which this book was not bad. Bad, bad writing.”

One writer’s had her book put on a reviewers “crap-i-couldn’t-finish shelf.”

Another was told, “This author had no right to write this book because she doesn’t really know what it’s like to be divorced. I went to school with her and I know for a fact she’s never been divorced.”

One friend’s book was compared to a Tampon ad.

Or was it a Tampon?

Each time I spin into a decline induced by a reader hating my book, I look up a classic, a best seller, a book I loved, and read Amazon reviews such as those below (sic included.) And then I wonder, would these classic writers have reached for the Ben & Jerry’s, were it then available?

Wuthering Heights

“I began reading–“though you mayn’t believe it,” to quote Lewis Carroll’s Mock Turtle–at the age of 1 and 9 months. Since then I have read literally thousands of books. And of them all, “Wuthering Heights” is my least favorite. The characters are so unpleasant and cruel to each other that reading the book is a seemingly endless nightmare.”

1984 by George Orwell

“Only read this if you like getting depressed. This is a good example of the fact that pessimistic and shocking books often receive rave criticism while dynamically optimistic books are dubbed “unrealistic”... NO further comment.”

The Woman’s Room by Marilyn French

“The worst book ever written. The most insulting and boring book ever written. It is a biting social commentary on men-women relations that is so one-sided and vulgar that most readers do not take seriously. Don’t ask me how it ended because I couldn’t stand the torture of the book.”

Anne of Green Gables

“Here is what most people and fans don’t know about the author:

Lucy Maud Montgomery was into the occult and worshipped nature. She taught girls how to make a “table rap” or to call up an evil spirit, and she introduced the Ouija board to the young fry of Cavendish. I believe that her books are “blessed” by an evil force, which is part of the reason that they (her books) have millions of fans. Lucy Maud’s ungodly beliefs appear often in her writings.

God opened my eyes to the bad influence of Anne Shirley and her author, and also to all the wrongs in L. M. Montgomery’s books.”

Goodnight Moon

“We were given this books as a gift. I really dislike it–there seems to be an upleasant undertone: “bowl full of mush”, “goodnight nobody”. I find the illustrations equally unpleasant (or maybe that’s why I find the book unpleasant). I recycled it.”

Tale of Two Cities

“I feel this could have been a better book had he not been paid for its length. It takes him too long to say simple things. If you hated Old Man and the Sea, you too will hate this.”

Bangers and mash, Mr. Dickens?

Pint of ale?

(first posted in 2011)

January 26, 2015

Food and Loathing and Hamper Cookies

Everyone hates a fat woman. Or is it that a fat woman thinks everyone hates her? Or does a fat woman simply hate herself?

As someone who’s measured her worth in dress sizes, waistbands, and, when in the midst of bravery, the hard-core truth of pounds, I’ve felt all of the above. We are a harsh country, filled with both self-loathing and a Calvinist push towards walking off, dieting away, running away from, and when all else fails, surgically sucking out unwanted fat.

Do men suffer as women do? I’m not sure. I don’t think so, not as much—not when fat men on screen are allowed to bed and wed women as lovely as Katherine Heigl. I think being fat is painful for men. I simply don’t think they’re as reviled; they need to climb far higher up the scale to merit as much hate as heavy women.

I recently re-read (even re-bought, when I couldn’t find my copy) Food and Loathing by Betsy Lerner. From far too young, Lerner’s existence rested on her body size—real and perceived. The book begins thusly:

“It is 1972. I am twelve years old. It is the first day of sixth grade, and I am standing in the girls’ gymnasium waiting to be weighed.”

If your flesh doesn’t crawl with those words, if you don’t want to either go running for a cream cheese smothered bagel, or conversely, vow to stop eating as of tomorrow, this book will still interest you, but you may not swallow it whole.

The hatred of our flesh often has no bearing in reality. One of my best friends in the world begins each day pinching her flesh with callipered fingers and living for her daily-rationed cookie. She is tight and muscled and yet lives each day as though a sorcerer might drop fifty pounds on her at any moment.

Do I understand this?

I do.

I grew up with a thin mother who lived for leanness and beauty. My sister’s body mirrored hers. To the day she died at eighty, my mother would ask, “how’s your weight” each time we spoke, as though my ‘weight’ was a living-breathing entity separate from that which she liked about me.

I sloughed her words off with sarcasm and sighs, still my life was frozen in moments: My mother hiding cookies in a pot on the top of the cabinets. (I got exercise climbing up.) Swiping the icing from the middle of the Entenmanns, until the cake became thinner and thinner (but not me.)

I remember the horror of looking for a dress for my cousin’s Bar Mitzvah as my mother rolled her eyes and complained to the sales women about her disgust at the lack of gowns into which I could zip. Last week I had to search for old family photos for an article. While doing so, I came across a picture of me at the Bar Mitzvah, wearing the gown.

This was the ‘me’ that wanted to die from being so fat. I can’t believe I suffered as I did. Of course, I also found pictures where I really was plump. But deserving of loathing?

Of course, that’s a mildly plump picture. Even now, it’s hard to put the real ones up.

We’re hated, we hate ourselves, and we learn to sneak our food. I devoured cookies that I hid in the bathroom hamper.

Betsy Lerner joined Overeaters Anonymous in junior high, where she learned to divide food into forbidden and good. She became a compulsive eater or a compulsive dieter, depending on the day, the month, and the moment. When binging, real life was always a day away. When dieting, she considered herself abstinent—except that sex became her comfort.

Mixed in for Lerner, was her struggle with depression and anxiety, finally ending up in a New York mental hospital after a suicide attempt, where, after years of being ill-treated by shrinks, she is diagnosed as bi-polar. This is presented neither as an answer to her relationship with food, nor as separate. It is part of her ongoing puzzle.

Food and Loathing is not a self-help book; it’s no guide for losing weight. Nor is it a companionable hug for staying heavy. It’s a mirror. It’s looking back, looking forward, or looking at who you are right this moment.

After finishing it, I thought (not for the first time, not for the last) about how much space I want to rent in my head to the mirror and to the scale. Right now, at this moment, month, minute, I am sorta-okay, and that’s probably okay. I think that perhaps, sorta-okay is as good as it gets with acceptance for some of us.

Yeah, when you grow up with hamper cookies and sighs, getting to sorta-okay when you look in the mirror can be a damned miracle.

That’s what I loved about Food and Loathing. Betsy Lerner tells that particular story very well.

(from the re-run collection.)