Randy Susan Meyers's Blog, page 27

November 8, 2014

The Ben Chart

October 29, 2014

Break-Your-Heart Books

Write a book that breaks your own heart. That’s one of the reminders I wrote myself before outlining my novel. (The other was don’t rescue your characters—a reminder not to fall so in love with them that I couldn’t bear having them in pain.

Whether or not a book digs deep and delivers the bones of an author’s truth—through memoirs revealing facts or novels delivering emotional authenticity—is apparent upon the reading. These are the books that pop me in the heart or provide moment of reality mirrored back.

I thought about this when I read Darin Strauss’s memoir, Half A Life, which explores his examination of living with the guilt of having accidently killed a high school classmate in a driving accident. Strauss goes that extra step, providing the squirmy details that take us into his experience and have us reflect on our own:

The accident had also turned me squishily obliging. I always cozied up to people—so that if they ever learned the story they’d say: “He seems so decent and kind. How awful that such a thing would happen to him!

Jesse, A Mother’s Story was written by Marianne Leone, a mother who loved her son with ferocity—the ferocity parents of disabled children need more than others parents. Jesse Cooper had severe cerebral palsy, was unable to speak, and was quadriplegic and wracked by severe seizures. He was also stunningly bright, funny, and loving. His parents, Marianne Leone and Chris Cooper, needed both rage and ferocious love if Jesse’s light was to come out in full.

Leone wrote her book so close that I felt the cigarette she held as I read how she:

Our session with the physical therapist was a disaster. She roughly stripped Jesse of his outside clothes, and he began to howl. “Well, I can’t work with him if he’s going to cry all the time,” she said . . . Jesse was failing physical therapy. Or was the therapist failing Jesse? To watch your child handled roughly is to have a piece of your soul crumple into ash.

In the opening of Tayari Jones’ novel Silver Sparrow the narrator’s direct candor took me deep faster than any string of fancified words could:

My father, James Witherspoon, is a bigamist. He was already married ten years when he first clamped eyes on my mother. In 1968, she was working at the gift-wrap counter at Davison’s downtown when my father asked her to wrap the carving knife he had bought his wife for their wedding anniversary. Mother said she knew that something wasn’t right between a man and woman when the gift was a blade. I said that maybe it means there was a kind of trust between them.

Right from the start I knew I was getting truth straight up.

Truthiness in books delivers windows on the world that help us understand; it also delivers those oh-so-important I’m not alone moments which get can get you through everyday pain—and isn’t it the everyday pain that often breaks our hearts? Jennifer Weiner’s Good In Bed explores the aftermath of a young woman reading her ex’s description of her in a national magazine, a dramatization of how so many of us fear being called out for being fat:

I could hear the blood roaring in my ears as I read the first line of the article: ”I’ll never forget the day I found out my girlfriend weighed more than I did . . . I never thought of myself as a chubby chaser”’ I read.

Dani Shapiro’s memoir Slow Motion provides understanding of the ways in which a complicated childhood can lead to a self-loathing-inducing affair (hers only struck down because of a family tragedy.)

I cannot face dinner with Lenny without a vial of cocaine in my handbag. My friend buzzed me in, and I run five flights up to her loft, skimming my hand along the chipped wood banister. I ring her doorbell, and she opens it, holding a paper bag. I know what will be inside without even looking, and I hand her a check for one hundred dollars. She trusts me and always takes my checks—a nifty trait in a drug dealer.

Depth of truth is not limited to particular genres—it resonates from the author’s willingness to reveal the squirmy details, the inside-thoughts, and the unheroic. It can be exposed with humor, straight on, or with chilling particulars (though self-pity generally sinks the impact of candor.)

Writing and reading books that hit the bone isn’t to everyone’s taste (some have told me my book is too dark,) but they help me. Even as a kid, I was never one for the happily-ever-after. Opening my eyes to the wounds of others helps me understand my own transgressions and spreads an empathy that balms my tender spots. Other times, I am given the gift of appreciating what I haven’t had to endure.

Writing towards the worst makes me braver—a trait I dearly need to employ more often. In my family, my sister and I are known for doing our ‘death watches’—always waiting for people to disappear and disaster to strike. Reading and writing about the dark side seems to be one of the ways in which I can lighten up.

Lord knows it’s better than whiskey,

October 21, 2014

GIMME A CAPPACHINO: 5 CAFFEINATED GOTTA KNOW READS

Halloween nears. Winter approaches. In the Northeast we face snow shoveling, icy roads, and bleak grey skies. Our rewards? Sundays curled on the couch with a great book. I could offer lists of classics you can finally settle into, uber-literary masterpieces to read with your dictionary at your side, or I can tell the truth. There’s nothing like a ‘gotta know’ book to get you through a blizzard. (Think Gone Girl … those books you absolutely must finish, cause (as Stephen King says in On Writing) you ‘gotta know’ how it ends.

For me, gotta know can be anything from a memoir on mountain climbing to a novel of a woman battling a town’s humiliation. It’s all about books that stole my sleep:

THE LITTLE GIANT OF ABERDEEN COUNTY by Tiffany Baker

When Truly Plaice’s mother was pregnant, the town of Aberdeen joined together in betting how recordbreakingly huge the baby boy would ultimately be. The girl who proved to be Truly paid the price of her enormity; her father blamed her for her mother’s death in childbirth, and was totally ill equipped to raise either this giant child or her polar opposite sister Serena Jane, the epitome of feminine perfection. When he, too, relinquished his increasingly tenuous grip on life, Truly and Serena Jane are separated—Serena Jane to live a life of privilege as the future May Queen and Truly to live on the outskirts of town on the farm of the town sadsack, the subject of constant abuse and humiliation at the hands of her peers.

“...the kind of book you find yourself stealing time from workday chores to read.” USA Today

THE DEEPEST SECRET by Carla Buckley

If you read The Deepest Secret late at night, better drink some coffee. This multi-layered story of a family beset by multiple crises is outstanding—the beauty of Buckley’s writing has us treasure each character, even as we cringe at the choices they make.

“Smart and thrilling...A taut family drama about a mother blindly obsessed with protecting her teen son from the UV light that could kill him.” PEOPLE magazine

In the winter of 1897, a trio of killers descends upon an isolated farm in upstate New York. Midwife Elspeth Howell returns home to the carnage: her husband, and four of her children, murdered. Before she can discover her remaining son Caleb, alive and hiding in the kitchen pantry, another shot rings out over the snow-covered valley. Twelve-year-old Caleb must tend to his mother until she recovers enough for them to take to the frozen wilderness in search of the men responsible.

Scott’s characters are dark brush strokes of appetite and deceit.” New York Times

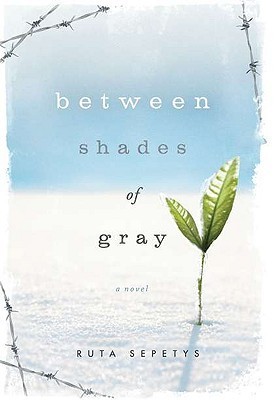

BETWEEN SHADES OF GRAY by Ruta Sepetys

Shelved as YA, it’s is most certainly an incredible read of adults.

A harrowing and horrifying account of the forcible relocation of countless Lithuanians in the wake of the Russian invasion of their country in 1939. In the case of 16-year-old Lina, her mother, and her younger brother, this means deportation to a forced-labor camp in Siberia, where conditions are all too painfully similar to those of Nazi concentration camps. Lina’s great hope is that somehow her father, who has already been arrested by the Soviet secret police, might find and rescue them.

“This superlative first novel by Ruta Sepetys demonstrates the strength of its unembellished language. A hefty emotional punch.”—The New York Times

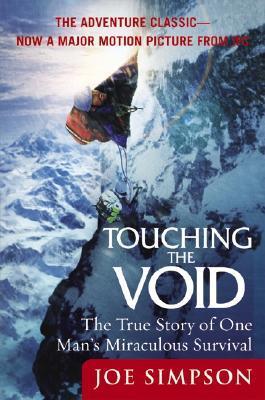

TOUCHING THE VOID by Joe Simpson

Joe Simpson and his climbing partner, Simon Yates, had just reached the top of a 21,000-foot peak in the Andes when disaster struck. Simpson plunged off the vertical face of an ice ledge, breaking his leg. In the hours that followed, darkness fell and a blizzard raged as Yates tried to lower his friend to safety. Finally, Yates was forced to cut the rope, moments before he would have been pulled to his own death.

The next three days were an impossibly grueling ordeal for both men.

“One of the absolute classics of mountaineering...a document of psychological, even philosophical witness of the rarest compulsion” —Sunday Times

Now get yourself a nice wool blanket, some cocoa, and enjoy....

October 14, 2014

A Furious Love

While readying to write about Professor Cromer Learns to Read, I searched for a quote or statistic that would put in perspective the overwhelming job families have caring for brain-injured loved ones, words that said how much we are failing brain injured soldiers returning from war, athletes cast aside after they’ve suffered irreparable damage to their brain, those who’ve fallen, those who’ve been in car accidents—all our mothers, fathers, wives, husbands, friends, partners, and children who struggle to make it back and most of whom will never be the same.

As Cromer says about many things, “all the above is true”, but instead, I’ll offer the words Janet Cromer said to her brain-injured husband each night:

“Alan, the joy of my life is waking up with you each morning. The joy of my life is going to sleep with you each night.”

Before his acquired brain injury, anoxic brain damage (and later dementia and Parkinson’s disease) engendered by his massive heart attack and cardiac arrest, Alan Cromer was a prolific author and physics professor at Northeastern University. Like so many of us, reading was the center of his life.

In Professor Cromer Learns to Read, author Jane Cromer takes us on an unprecedented love story. The author struggles through the caretaking of her brain injured husband—years when he is often scary and sometimes unmanageable, and yet this is a love story so tender that one finds many moments to envy their relationship.

Janet and Alan Cromer traveled from Boston to Chicago for a family reunion. A few days later, on the return flight, Alan’s heart and the Cromer’s life stopped. Both were resuscitated. Neither remained recognizable.

Most books of recovery end when the healing begins—leaving the reader uplifted and with the ability to imagine a trajectory of continuing good change. Janet Cromer brings us through the entire cycle of her husband’s tortuous road, first to some semblance of recovery—but never of a return to his former life—and then lets us into their lives and their marriage as medically and emotionally things become worse, leading towards Alan’s death seven years after his heart attack.

This book grabbed me by my heart and held tight until the final page. Cromer, both a poetic and a plainspoken writer, offers shining tough honesty. She shares her fear of losing this man for whom she has a ‘ferocious love.’ She also shares the loneliness, grief and exhaustion of living with this new Alan, who in the grasp of brain injury could become rage-filled and frightening. Calling it “all the above is true” the author paints a picture of her life ricocheting from hope to tenderness to her own dark rage.

Janet Cromer brings the ultimate gift to the reader: opening a door to her furious experience with authenticity, openness, and a page-turning craft. She captures the medical information gracefully and clearly, never turning away from the difficult parts. She opens the door to her marriage and lets us in every room. Never do Alan or Janet Cromer get saint treatment (though at times I thought they should.)

Professor Cromer Learns To Read is a memoir, a story of medical courage, but at its’ core it is a love story.

I read this book because it was written by one of my closest friend’s dear friend. When Diane promised it was a magnificent read I tried to believe her, but I worried. I didn’t open it with great hope. I was prejudiced by most of my experiences with self-published work (which lacked proper editing and suffered from the lack of an objective eye pulling out the weaker parts.)

Professor Cromer Learns To Read so surpassed my expectations (reflecting the authors’ dedicated participation in writer’s groups in Provincetown, Cambridge, and Boston) that I wrote the author asking why she’d not taken the traditional publishing route. In her answer she wrote:

“Timing was my main consideration. Alan had been dead for a few years already and I wanted the story to be timely. Brain injury (BI) is in the news constantly due to the estimated 300,000 returning vets with some degree of BI, and I want to be of some assistance to their families. Last summer as I raced to finish the book, I was in a whirlwind of preparing my 12 room JP house to be sold after living there 25 years, undergoing unexpected spinal fusion surgery with a long recovery, and planning my wedding. I remarried last August and moved to Bethesda, MD. My husband has been terrific in this bizarre situation: his new wife is spending their first year together promoting a book about her first husband!

So, with all that going on, I didn’t want to spend another year sending out book proposals, then another year for the book to be published if I was really lucky. My plan was to publish first with Author House, then send out proposals to traditional publishers. I’m still interested in that route.”

Lucky is the agent and publisher who adopts this book. Janet Cromer has already received an award for “Excellence in Medical Communication” and the “Neil Duane Award of Distinction” from the American Medical Writers Association New England Chapter.

Janet Cromer’s book can be purchased at Amazon and through janetcromer.com.

I loved this book. Buy it now, and then later you can say you were one of those smart early readers.

October 9, 2014

From Metal Sculptor to EMT to Novelist: “An Unseemly Wife”— A Fascinating Look At E.B. Moore

Nichole Bernier talks to E.B. Moore about publishing her debut novel at 72: “The Amish life is exotic to behold and comforting, a little like going to a habitat zoo to watch the slow march of elephants cropping grass with their trunks and blowing dust over their backs.”

When I first moved to Boston and began attending literary events, I noticed a striking woman who seemed to be at all of them. She was statuesque and ageless, with long white braids piled on top of her head, blue eyes twinkling and, at the same time, penetrating behind wire-rimmed glasses. Reserved, but appeared to know everyone. Usually in jeans, wool socks, sneakers, and a sensible Oxford blouse. Extraordinarily good posture. Who was she?

She was, I came to know, E.B. Moore, a poet and a prize-winning metalworker, and part of the Grub Street writing community. And she’d recently been accepted to Yaddo to work on a novel based on her Old Order Amish ancestors (she herself grew up Quaker) who broke from their tradition to head west by wagon trail and mix with outsiders, to disastrous result.

These days, to my good fortune, she is, to me, simply Liz, a dear friend and writing-group member whose debut novel I get to cheer out of the gates this month. I love her lyrical and spare writing—she delights and surprises me constantly with her observations and turns of phrase. Among my first hints that this self-contained septuagenarian held unexpected gem-seeds of rebellion was her essay “Baby Boomer Warns Women.” In it, she playfully but resolutely urges women to protect their time and dreams rather than succumb to the cult of perfect laundry:

Beware the sneaky creature polluting your habits, attacking your time, the destroyer of liberty and libidinous thought….the good girl. You can’t be nice to the nice, to the one who wields guilt like a sword. You must tie her and gag her, garrote her and take what you need. Even garroted her head will shriek from the floor, “You’d abandon your family?” She’s a siren, so stuff your ears, cover your eyes when the family sweatpants march on their own, remember your loved-ones who master a Wii can easily program a washer; and never fall for puppy-eyes, the helpless shrug when they can’t find an app for that vacuum.

September 25, 2014

20 Fiction Techniques . . . Quickly

During my (self-guided, self-nagged) courses in my ‘Homemade MFA’ I did many things: I read stacks of books, I read multiple favorite novels with an analytical eye, I participated in multiple writer’s groups and revised, revised, and then revised some more. And, I wrote ‘papers’ for myself, in an attempt to distill down all the fantastic advice I’d gleaned from those book stacks.

What I couldn’t learn from the books was ‘voice,’ ‘passion’ or ‘perseverance’ — that required mining my own soul and level of commitment; what I could learn was those all important, and too often ignored, techniques that make one’s prose more sophisticated. Gathering from all the sources I could find, I make my “Cliff Notes for Fiction Techniques” otherwise known as Common Fiction Issues in Super-Short, Simplified Format.

What’s below isn’t prettied up or served with garnish–it’s my original ‘just the facts, mam.

1) Showing or telling? How much narrative summary do you have? Do you write “He was fuming” or “He kicked the wall?”

“Don’t say the old lady screamed. Bring her on and let her scream.” Mark Twain

2) Characterization? What’s going on with your character? Can we see her worries, fears, and hopes? How many? We seldom feel one thing at a time. Have you tried a little tenderness? Shown the characters vulnerability? Readers like vulnerability, but beware showing pain laced with self-pity: readers dislike weakness and self-pity; show pain subtly and whenever possible, with humor.

Avoid thumbnails sketches and let character unfold before the reader. Don’t define everything about them the moment they come on stage, start with a bit of looks, and let character’s personality reveal the character, rather than relying on physical sketches. Watch ‘looking in the mirror’ descriptions. Have your characters misunderstand each other at times. Have them answer the unspoken question rather than the one asked aloud. Have them hedge, talk at cross-purposes, disagree, lie, sound human.

What does your character(s) want? What’s the obstacle to the want? What action has your character taken to overcome the obstacles? Are things too easy for your characters—thus tamping down tension and conflict?

“Readers want to be haunted by characters” Jessica Morrell

3) Is your point of view pitch perfect? Keep the camera angle straight. Keep description and observation within character’s point of view: is your Hell’s Angel guy describing the sunset too poetically? Nasty Jack rode along a sunshine drenched highway vs. Nasty Jack rode along the heat-choked highway.

4) Does your dialog hold interest and is it sophisticated? Dialogue: Watch tagging – use the invisible ‘said’ most often. Watch ‘ly’ adverbs or emotional attributions. Replace “Do you still love me?” Maria asked nervously with “You still love me, right?” Maria gripped the steering wheel with both hands.

Could you use more contractions, more sentence fragments, and more run-on sentences? Is stiff dialog really exposition in disguise? Avoid dialect and weird spellings.

5) Do YEGO or MEGO? (Your/my eyes glaze over, courtesy of Stephen Koch, The Modern Library Writer’s Workshop.) Are you bored when reading any sections of your book? So is the reader.

6) Lost in interior monologue? Enough is enough—is it getting self-indulgent? Sound like an essay? Or, conversely, do your clients move, move, move without any introspection?

“Stick to the point.” W. Somerset Maugham

7) Do you have stage business: don’t forget the little bits of action interspersed through a scene. Avoid repetitive stage business. (Always drinking or smoking?) Do they illuminate your character? Are they particular to him/her? Do they fit the rhythm of dialog?

8) Can you judge anything through the white space? Enough? Too much? Are your characters making speeches rather than speaking?

9) Did you repeat? Watch repetitive action, characters, emotions, etc. Readers don’t need sledgehammers.

10) How the proportion? Watch the blow by blow. Don’t lose drive. Your interest/hobby/knowledge isn’t fascinating to everyone. Too many flashbacks rob narrative drive.

“The secret to being tiresome is to tell everything.” Voltaire

11) Is your writing sophisticated or amateur? Janet Burroway writes in A Guide to Narrative Craft:

“John Gardner says in addition to the fault of insufficient details and excessive use of abstraction there is a third failure: ‘…the needless filtering of the image through some observing consciousness. The amateur writes: Turning she noticed two snakes fighting in among the rocks. Compare: She turned. In among the rocks, two snakes were fighting. Generally speaking–though no laws are absolute in fiction—vividness urges that almost every occurrence of such phrases as “she noticed” and “she saw” be suppressed in favor of direct presentation of the thing seen.’

The filter is a common fault and often difficult to recognize—although once the principle is grasped, cutting away filters is an easy means to more vivid writing. As a fiction writer you will often be working through “some observing consciousness.” Yet, when you step back and ask readers to observe the observer, to look at, rather than through the character—you start to tell, not show, and rip us briefly out of the scene.”

Watch simplicity, construction and linking verbs (fought as opposed to were fighting.) a) Maria swore at Joe as she tore off her shirt vs. As Maria was ripping off her shirt she angrily flung swears at Joe. b) Maria slammed her cup on the counter vs. Hating Jim, Maria viciously set her cup on the counter.

Sentence choppy? Too short? Overly-said-killing-the-point-long? Leaning on Italics? Or explanation points! Flowery descriptions everywhere? Sex not leaving enough to the imagination? Are you making it into a manual? Too much profanity? Are your starting sentences with when, suddenly and then? Did Maria nod her head? Have Maria nod. Did Maria sit down on the bed? Have Maria sit on the bed.

“Omit needless words.” Stunk and White

12) Always sure of your setting? Where are your characters? Is it hot? Cold? What month? School in session? Summer vacation? Holidays coming? Orient the reader.

“If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.“ Elmore Leonard

13) Have enough details? What are they wearing? Look up, look down: shoes, hair (messy, neat?) what are they sitting on? Nails bitten? Polished? Desk messy or neat? Any dust on the dresser?

14) Avoiding passive construction. Is your voice active? Does enough happen in scene? Are you overusing ‘was,’ leading to the dreaded passive voice? Maria spilled the milk as opposed to the passive voice: The milk was spilled by Maria.

15) Explaining too much? Resist the urge to tell the reader what is funny, what is sad, etc. If you think it’s unclear, rewrite, don’t explain.

“Storytelling reveals meaning without committing the error of defining it” Hannah Arendt

16) Have you checked your sentence mechanics: Do you have a changing rhythm of short and long sentences? Does your sentence begin or end with the drama? A) The stolen diamonds were in Maria’s purse. Or: B) Maria’s purse held the stolen diamonds. How’s your grammar?

“Clarity. Clarity. Clarity.

When you become hopelessly mired in a sentence,

it is best to start fresh.” Strunk & White

17) Are your tics showing? All of us have writing tics—discover yours or have someone point them out (If I let them, all my characters will lean toward the other characters during times of stress) and remove most of them,

18) Have you balanced scenes and sequels? Can you feel a good rhythm of active scenes vs. reflective sequels? (Scene: Maria stole the diamonds. Sequel: Maria googled “arrest” to determine her chances of doing time.

19) Transitions clear and smooth? Are you moving the reader through time? Sliding effortlessly into flashback? Showing setting changes? Showing changes in mood, tone, emotion, weather, and POV? Are transition sentences performing double duty?

Examples of transition sentences: James arrived on drizzly evening with an envelope in the pocket of his jeans. “I got rejected at Putnam’s” he said when she opened the door. From Rosie by Anne Lamott.

20) Descriptions: Characters & More: Watch out for the ubiquitous ‘looking in the mirror’ descriptions. Don’t rely on the ‘hair, eyes, height’ character picture. Rather than writing how beautiful Elisha had tumbling red lock spilling over her shoulder, sparkling green eyes and towered over most of her coworkers, try Elisha towered over her coworkers in a manner reminiscent of a supermodel crossed with scariest grade school teacher.

Similarly, when describing settings and objects, less is more. Think of how combining too many colors can lead to a muddy picture. The same happens with an overuse of descriptive words: the reader is left trying to build the scene/character and is no longer lost in your world.

“To write simply is as difficult as to be good.” Somerset Maugham

September 21, 2014

First Paragraph Love

“I was born twice: first, as a baby girl, on a remarkably smogless Detroit day in January of 1960; and then again, as a teenage boy, in an emergency room near Petoskey, Michigan, in August of 1974.” Opening to Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides

I read that sentence and I immediately want to re-read Middlesex.

Sometimes I think I can write an entire book in the time it takes me to revise the first paragraphs of a novel. At the very least, I can write 3 chapters in that time. Lately, as I’ve been lost in the world of revision, when I read, I find myself studying the first paragraph.

What do I want from that introduction? Set up. Intrigue. A gotta-keep-going.

“After my brother went missing, my parents let me use their car whenever I wanted, even though I only have a learner’s permit. The didn’t enforce my curfew. I didn’t have to be excused from the dinner table. The dinner table, in fact, had all but disappeared, covered with posters of Danny, a box of the yellow ribbons that our whole neighborhood had tied around trees and mailboxes and car antennas, and piles of the letters we’d gotten from people praying for Danny’s safe return or who thought they saw him hitchhiking along a highway a couple states away. I didn’t have to do any more chores.” Opening to The Local News by Miriam Gershow.

It’s impossible for me not to continue reading a book with that beginning.

Each time I try convincing myself that I don’t have to spend hours, weeks, days on the opening, I remember my own book buying habits:

Go to bookstore. Pick book up (based on some inexplicable reaction to the title, recognizing the author’s name, or perhaps the color of the jacket?) Open book. Read first paragraph.

Read book flap. Glance at blurbs. Briefly. Neither of those will make or break a purchase for me, but the next step will. I open the book and read the first paragraph. If, and only if, that first paragraph intrigues me, then I will skim the first page. I am not recommending this as a way to judge a book, but instinctually, it’s what I do repeatedly. (Of course this is only with books I am picking up at random—I’ll give reviewed or recommended books a bit more lee-way.)

It’s easy to dismiss this first-paragraph mania. I’ve heard many say: but you have to get past my beginning—that’s the set-up. The book really begins in chapter two. Really? Then begin your book in chapter two.

Of course, giving advice is different from taking it. It took five revisions for me to comb out pages of backstory when writing my book. Every word, every detail, every bit of the character’s history seemed so important to me. So interesting! Aha, that was the problem, I realized. It seemed important to me, but perhaps it not so much to the reader. It may be similar to having children. Your kid’s every drawing? Fascinating. Other kid’s art work? Hmm . . . not so much.

I can’t lay out rules for opening a novel, but I think writers should lay out rules for opening their novel. I would suggest including some general guidelines:

– Don’t be lazy. Yeah, this sounds stupid, but I think many openings are marred by a “I don’t want to do anymore” set of mind. You know when it’s not good enough, don’t ignore that feeling.

–Work for the ‘ring’ and then, when you think you have it, read it out loud. Many times. I think there is a sort of hum in one’s chest when you hit the sweet spot with an opening. Write until you feel it.

– Pick books off your shelves at random. Go to the library and the bookstore and chose books that you don’t know. See which ones you want to read after reading the beginning, and then figure out why. That’s the beginning of how you make rules for your opening paragraphs.

Good openings can’t guarantee anything except increasing the chances that your readers will turn the page, but that’s a big one.

Grab your reader by the throat:

“The physical inspection was first. Eyes. Nose. On her chin, a thumb opened her jaw. The woman’s hands weren’t soft but they were dry, a least, like salted fish. Minna closed her eyes, then worried she looked afraid and opened them. The fingers tugged on her earlobes. They prowled at her nape.”

Opening to Little Wife by Anna Solomon

Intrigue them:

“My first patient had been dead for over a year before I laid hands on her.” Opening for Final Exam, A Surgeons Reflections on Morality by Pauline W. Chen.

Find that opening that makes the reader-heart beat just a bit faster.

September 15, 2014

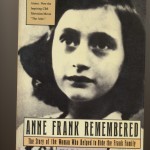

Anne Frank Remembered: The Story of the Woman Who Helped the Frank Family By Miep Gies with Alison Leslie Gold

“I am not a hero. I stand at the end of the long, long line of good Dutch people who did what I

did or more—much more—during those dark and terrible times years ago, but always like yesterday in the hearts of those of us who bear witness. Never a day goes by that I do not think of what happened then.

did or more—much more—during those dark and terrible times years ago, but always like yesterday in the hearts of those of us who bear witness. Never a day goes by that I do not think of what happened then.

More than twenty thousand Dutch people helped to hide Jews and others in need of hiding during those years. I willingly did what I could to help. My husband did as well. It was not enough.” (from the prologue.)

This is not a new book, but one of those to which I return. I even like holding it in my hands and just looking at the name of the woman whose journey it reveals: Miep Gies.

Miep is the woman who, with her husband Jan Gies, helped hide Anne Frank from the Nazis. Like so many young Jewish girls growing up I was more than a little obsessed with stories from the Holocaust; especially The Diary of Anne Frank. At the time she wrote in her diary, she was probably only a bit older than I was at the time I read the book, so, of course, I walked in her shoes. It certainly didn’t seem long enough ago to not think about her as me, and me as her.

Was there a Jewish child growing up anywhere in the world who didn’t think what if? Some, I imagine, averted their thoughts from the events of WWII and pretended it was all as far away as the Roman Empire. Others, went through life compulsively reading about it, breathing the lives of those who’d lived through it and those who had lost their lives.

On top of the obvious victims, were the other victims—those who were forced to witness the atrocity, those who participated. After visiting the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC, and I paraphrase here, what my husband and I remembered most deeply, were the audio-taped words of a survivor. In speaking about his experience in a concentration camp, he related a story of being berated by a fellow internee for praying.

“Why are you thanking God?” he was asked.

“I am thanking him for not making me him,” the man said, pointing to a guard.

It is horror without relief to have been a slave, a concentration camp internee, and a victim in Darfur. It is another horror, to have been the victimizer.

Books like this, they always make me wonder, given the circumstances, on which side would I end up? We read the books, we watch the movies, and we assume we’d have the courage of the righteous, but I believe it bears remembering how brave people like Miep Gies had to be, and to remember all the Miep and Jans out there today. I pray that given the circumstances, we’d follow their path.

September 8, 2014

Why Did She Stay? How Come Nobody’s Asking Why He Did It?

Twitter & Facebook abound with it. Some claim with surety that they’d leave after the first minute a man touched them. Other wonder (with an air of superiority) why Janay Rice married Ray Rice in the first place (often accompanied with gold-digging, victim-blaming reasons.) Many question her ‘role’ in the situation—wondering why she stayed, sat next to him, tweeted support, etc, etc, etc.

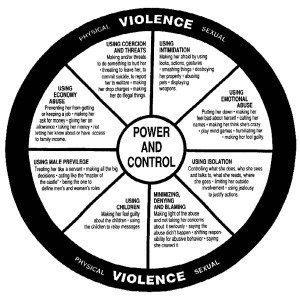

Everyone has an opinion about and questions about Janay Rice. Why, why, why. I pray someone is there for her, helping deflect the meanness and judgment. I worked in the field (working with batterers) for ten years. I could write pages of ‘why women stay’—explaining how women become trapped by violent men, but instead I provide the above link, and concentrate on the important question we should be asking:

Why did Ray Rice, this 218-pound professional athlete, pound on his wife, the mother of his child?

For years I sat in church basements listening to men speak about their violence towards woman. I worked in a Certified Batterer Intervention Program where men blamed their violence against women on everything from invisible buttons their unreasonable wives pressed, to whiskey and beer.

These men weren’t different from the bad boys to whom I’d once been drawn. I craved them before, but never again. My father tried to kill my mother—maybe that’s why I switched from dating these ‘bad boys’ to offering them education, and education that offered tools for change, but they had to choose to use them.

They fought the idea that they could control themselves. Thinking themselves victims of invisible buttons was more comfortable than admitting they chose violence to get their way. And what did they want? Why did cheeks get shattered and tender skin become black and blue?

Money, sex, too-cold food. When honest, they admitted they simply wanted her to shut the “f” up. They didn’t have the goal of breaking a bone. They had goals like hot suppers and sex and met them the quickest way they knew: fists and raised voices.

The curriculum included drawing triangles with chalk to help the men look at their belief system. During this lesson on the hierarchy of power, we’d use different ‘systems’ so they could identify the ways they classified people. Schools, corporations and prisons were just a few of the organizations we sliced and diced.

And family.

When asked to define the layers of family, the woman were on the bottom of the heap. Some men argued that the women rated a place above the male children, but they were always wedged under the husbands and fathers. Men who’d grown up in single mother households still stuck the father figure on top.

This doesn’t come from the air.

Honestly? I got shaky watching the video of Ray Rice beating on his wife. One of my novels, The Murderer’s Daughters, revolves around young girls witnessing their father murdering their mother. I worked with men who savagely beat (and some murdered) their partners. My father tried to kill my mother, and still I try to pretend that it’s not happening. If I attempt to live in this fantasy world, how deep do others bury it? How many of us try to pretend it’s not happening, that it can’t happen to us, and instead think of reasons why she stayed, why it happened to her, but could never happen to us.

But it’s not true. There’s an awful lot of woman-hating in the world, and it’s all too acceptable. And men who batter and kill their partners are usually self-pitying and see themselves as victims —victims with fists. For these men, it’s all too comfortable to step on someone else’s head to lift oneself up.

The men I worked with, after being arrested for hurting their wives, usually claimed good reason. “She pushed my buttons.” “She was being a bitch.” “She knows I hate it when she ... “

I’d ask them if they ever punched their boss, and they’d laugh as though I were crazy.

“Don’t you ever get mad at your boss?” I’d ask. “Don’t they push your buttons?”

“Of course, but I don’t hit them.”

“Why?” I’d want to know. “Do you love your boss more than you love your wife?”

Usually they’d open their mouth and sputter, not knowing what to say. That’s when we’d go back to the hierarchy of power.

It’s easier to step on the person on the bottom, and we’re still sadly in a world that places wives, girlfriends, daughters and mothers on the bottom rung for the crime of being female in this world.

There’s a lot left to teach our children, such as notions that equality can equal life, and bring authentic relationships. Hitting, yelling, pushing–these are all bad. It doesn’t make you big and manly. It makes you small and mean.

So why did Janay Rice stay?

It doesn’t matter one bit.

All that matters is why Ray Rice punched her, and why he chose the path of anger, violence, and meanness. How he can learn he has control. Whether he chooses to use it.

It’s on him.

September 2, 2014

Likeability Factors Laced With The Betty Crocker Syndrome (In Fiction)

Speaking with readers, reading reviews, and being interviewed means walking between fascination, terror, joy, and angst. Three days ago, speaking about my just-released novel Accidents of Marriage, a reporter mentioned how surprised she was by her negative reactions to the main character—how she seemed to ‘provoke’ her husband and how she sympathized with the husband’s anger. The next day, participating on a book festival panel, the moderator spoke of the husband as a virtual out-of-control monster, and Maddy as a frightened woman battling emotional abuse.

Yes! My job here was done. Making characters as nuanced on the page as we are in real life is one of my priorities. Plus, readers bring their own experiences to fictional characters, to our stories, and to however authors’ belief systems color our work. (Similar to how each one of us found our favorite Beatle—mine was George—I’ve always been drawn to the quiet ones).

But there’s a troubling undertone I’m noting in some reactions to novels about domestic drama books, books that examine whether a woman (or man) ‘deserves’ to live without verbal, emotional, or any other sort of abuse. In Accidents of Marriage (using multiple points of view: a wife, a husband, and their 14-year-old daughter) Maddy is married to Ben, a man with a trigger-temper; she never knows what will set it off. When he’s charming, he’s terrific: funny, smart, and capable. When he’s irate, he’s terrifying: raging, critical and blaming the world for his troubles.

Relationship interactions are never static. Sometimes Maddy placates, working hard to keep her children unaware of the problems she and Ben face; other times she gives in to her frustration and answers back, giving in to her edginess. Plus, she’s a bit messy, a working mother with three children, who’s rarely (if ever) on top of the unending chores facing the family. When life becomes too much, she’ll nibble a Xanax. But she doesn’t deserve to be screamed at, raged at, to be driven at speeds that petrify her. She certainly doesn’t deserve to end up in an accident that changes her entire life.

For years I worked with batterers, criminals, men ordered to a violence intervention program and the hardest nut to crack was this: one’s violence, one’s temper, one’s temperament, should not be contingent on another’s behavior. We all control ourselves. To whit, we scream at our spouses and children—rarely do we verbally attack our bosses no matter how much they enrage us. Why? Because a) they have power over us, and b) we do have control—it’s all about whether we choose to use that skill or not. And yes, it takes some work. When do we choose to use it and why?

Which brings me to the likable character. There’s been a debate back and forth for a while in literature (especially when the author is a woman) as to whether or not a book should be judged on the likeability of a character. This flies in the face of what I want in a book: to be fascinated by the men and women populating it, to root for them to change, and for them to get through their crucibles as unburned as possible.

And with the ‘bad guys’? I want them to own up to their deeds and pay for them.

In Accidents of Marriage, only the children are the innocents. (And they have their extremely unlikable moments; is there a child that doesn’t?

Which brings me to Betty Crocker. When I worked in domestic violence, we spoke about working against the Betty Crocker syndrome (Betty Crocker representing the lovely perfect woman,) the importance of teaching the public, the men we worked with, and those in the field, how we should never judge the behavior of a perpetrator by the personality of their victim. Nobody deserves to be abused or terrified. Nobody learns (not children, not adults) through terror.

Terror is for the one doing the terrifying. It’s how they off load their own defeat. It’s how they release their own negativity on those around them.

It’s never a tool for building family. Not in real life, not on the pages of a novel.

The very best way to comport oneself is too follow the moral code you’ve built for yourself, and it shouldn’t be mutable based on other’s behavior.

It’s hard work to get there.

In real life.

And on the page.

That’s what I want in the novels I read and write: stories of imperfect men and flawed women taking the long hard journey to get to that place.

So, I think I’m speaking on behalf of many authors: judge us on our lousy writing, our bad grammar, our lack of plot, our sloppy syntax, and our purple prose. But please don’t expect all us to feature Betty Crocker. Sometimes we really want to get inside the head of the Carmela Sopranos of the world. The complicated women.