Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 25

May 31, 2022

The often-overlooked connection between traumatic brain injury and domestic violence

Both domestic violence and traumatic brain injury are recognized as important public health concerns, but they are often discussed as separate issues when really they should be considered together. While domestic violence can also be emotional abuse and not only physical abuse, this is an area of physical abuse that warrants more attention than it currently receives. In a recent piece for STAT News, I talk about the connection between domestic violence and traumatic brain injury:

As research on this relationship trickles in, what has been found is extremely troubling. The Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix opened a center in 2012 not only to look specifically at traumatic brain injuries among domestic violence survivors but also to connect them with treatment and assistance in navigating health systems that can be challenging even on the best of days, regardless of a person’s health and resources. Although one published study from this center is small, it hints at what may emerge given the time and effort of research on a much larger scale. Of the 115 patients in this retrospective study, 92% of those who reported one or more brain injuries related to domestic violence reported “too many injuries to quantify.

Read the full piece, here!

The National Domestic Violence Hotline is available 24/7: 800-799-7233.

The post The often-overlooked connection between traumatic brain injury and domestic violence first appeared on The Incidental Economist.May 23, 2022

When a Medicaid Card Isn’t Enough

Much of the discussion surrounding Medicaid focuses on expansion. However, is there enough being done to ensure care is accessible once people are enrolled? In Tradeoffs, Paul Shafer, argues that network adequacy standards for Medicaid plans are failing to ensure availability of providers. Access to care is limited for Medicaid enrollees in part because Medicare and private insurers provide physicians with higher payment rates. Shafer writes,

A new paper in Health Affairs by Avital Ludomirsky and colleagues looked at how well the networks of physicians supposedly participating in Medicaid reflect access to care. The researchers used claims data and provider directories from Medicaid managed care plans in Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan and Tennessee from 2015 and 2017 to assess how the delivery of care to Medicaid patients was distributed among participating doctors. Their results were striking:

One-quarter of primary care physicians provided 86% of the care; one-quarter of specialists provided 75%.

One-third of both types of physicians saw fewer than 10 Medicaid patients per year, hardly contributing any “access” at all.

There was only one psychiatrist for every 8,834 Medicaid enrollees after excluding those seeing fewer than 10 Medicaid patients per year. This is especially concerning given that the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened mental health in the U.S., particularly among children.

Read the full piece here!

Research for this piece was supported by Arnold Ventures.

The post When a Medicaid Card Isn’t Enough first appeared on The Incidental Economist.May 19, 2022

Translating Research into Policy and Action

A new special issue of Health Services Research, which I co-edited with Amy Kilbourne, PhD and Arleen Brown, MD, PhD, focuses on the translation of research into policy and action. This issue features work at the intersection of evidence-based policy evaluation, implementation science, and community engagement — our goal was to highlight work that bridges the gap between evidence generation and policy action.

In a commentary providing an overview of the issue, we write:

Science fails to make a real-world impact on health without adequate investment in implementation science and community-engaged research. Implementation science, or the study of strategies that promote uptake of research into the real world, must be coupled with an active and ongoing partnership with communities affected by the studied issues, so that scientific results are meaningful and used by the broader population.

Check out the entire issue here!

This issue was made possible with support from the Veterans Health Administration Health Services Research & Development Service.

The post Translating Research into Policy and Action first appeared on The Incidental Economist.May 17, 2022

Do Medicare Advantage Networks Vary by Plan within Contract?

Allison Dorneo (@allidorneo) is a Health Services Research PhD student at Boston University School of Public Health.

Medicare Advantage (MA) is the private insurance alternative to traditional Medicare. MA organizations contract with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to offer eligible beneficiaries residing in a defined geographic service area (a collection of counties) a selection of private plans. Insurers may offer multiple plans across different plan types under one contract. The service area is defined at the contract-level, and for most MA plans, service areas can include a single county or a collection of multiple counties. (There are other types of plans for which there are constraints on the boundaries of the service area, but these don’t account for very much of MA enrollment.)

As MA-offering insurers contract with CMS, they establish networks that govern patient liability for seeing in- and out-of-network providers. Consequently, plans will vary in their cost-sharing structures and benefit designs as they assume different levels of liability for the cost of out-of-network providers. Overall, plans will cover the cost of care (less copays and deductibles) for patients seeing providers in-network, and certain plan types may require that patients pay more for out-of-network services or receive referrals/prior authorization from primary care providers (PCP) to see specialists.

The most common plan types offered by MA insurers include the following:

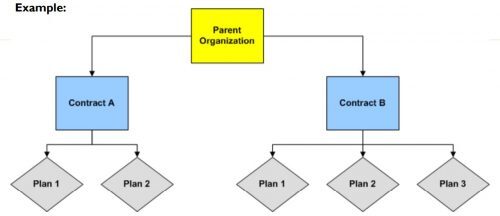

Preferred Provider Organizations (PPOs) are considered the most flexible type of plan in providing access to care and covering it out-of-network. PPO enrollees can use out-of-network providers for covered services without a referral from a PCP, albeit at greater cost to them than in-network providers.Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs), in comparison to PPOs, are more restrictive plans that provide less access to care and less coverage for out-of-network providers, with the exception of emergency, urgent, and dialysis care. HMO members are required to select a PCP and must get authorization for most specialty services. For any out-of-network services received, the patient bears the full cost, up to the traditional Medicare rate.Health Maintenance Organization Point-of- Service (HMO-POS) are a hybrid plan between PPOs and HMOs. Like an HMO, members must select a PCP for care coordination, but they do not need a referral for specialty services. (However, some services may require prior authorization for coverage.) Like a PPO, this plan does provide some coverage for out-of-network providers.The differences across plan types in access to and cost sharing for out-of-network providers leads to the important question, do MA networks vary by plan within contract? For example, in Figure 1 below, do the beneficiaries enrolled in Plan 1 or 2 under Contract A have the same set of in- and out-of-network providers (likewise for the beneficiaries in Plans 1-3 under contract B)? More specifically, what if Plan 1 is an HMO and Plan 2 is a HMO-POS plan, do they share the same network?

Figure 1: CMS Medicare Advantage and Part D Contract and Plan Enumeration (2010). Source: https://ncvhs.hhs.gov/wp-content/uplo...

Figure 1: CMS Medicare Advantage and Part D Contract and Plan Enumeration (2010). Source: https://ncvhs.hhs.gov/wp-content/uplo...The simple answer seems to be: not necessarily, though more recent regulations attempt to push insurers toward having the same networks across plans within contracts.

For instance, prior to 2019, CMS only reviewed the adequacy of an MA organization’s contracted network under a “triggering event,” like if an organization were to operate a new plan, expand coverage to additional service areas, or in a response to inadequate network complaints. The scope of CMS’ review varied depending on the triggering event that occurred. In some cases, CMS could only conduct partial reviews of a contract’s network, looking at a select set of specialties or counties. A study by the US Government Accountability Office found that between 2013 and 2015, CMS had reviewed less than 1% of all networks. Without regular scrutiny by regulators, it seems likely that networks varied across plans within contracts.

Under the current MA Network Adequacy Criteria Guidance, CMS assesses network adequacy requirements both under triggering events (as explained above) and, separate from that, on a triennial-basis at the contract-level. CMS has previously commented in the 2021 Final Rule that this approach allows them to assess the adequacy of organizations’ networks across all of their plan types (HMOs, PPOs, SNPs) and consider the broadest availability of providers and facilities for an organization. Again, this suggests that insurers may vary networks across plans within contracts.

There are at least two scenarios for which we know certain plans can and likely do have different networks compared with other plans in the contract.

Special Needs Plans (SNPs) are plans designed for individuals with specific diseases or characteristics, such as those who are dual-eligible, have institutional care needs, or have a chronic condition. SNPs can be allowed by regulators to augment the contract’s network to integrate care management teams and specialty providers to accommodate beneficiaries’ complex care needs under the plan’s Model of Care. While SNPs may be granted additional flexibility to alter the contract-level networks established, CMS does not allow SNPs to narrow or shrink that network. They can only expand it.Provider Specific Plan (PSPs) are plans often found under large, integrated medical groups or provider groups that are the primary bearers of risk. PSP enrollees have access to a smaller subset of in-network providers. Since this plan type has a network of fewer providers than the overall contracted network, organizations must request to offer a PSP from CMS and attest that these plans are in compliance with network adequacy requirements.Future work with Vericred provider-network data could be one approach to exploring variations in networks among plans under the same contract and service area, beyond the cases listed above. If networks are varying across HMO, PPO, and HMO-POS plans within contracts, it would be interesting to explore just how different they are from one another. Moreover, as CMS reviews continues to review network adequacy requirements at the contract-level (and if networks do differ by plan), one should consider the breadth of the network that organizations are submitting for evaluation. To what extent all plans in a contract are in compliance with network adequacy rules warrants future investigation.

Research for this piece was supported by Arnold Ventures.

The post Do Medicare Advantage Networks Vary by Plan within Contract? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.April 29, 2022

Red Meat Allergy from Tick Bites?

Can you really become allergic to red meat? Yes. Alpha-gal is a sugar molecule found in many mammals, including pigs, cattle, and lamb. And yes, it is possible for the human immune system to become reactive to alpha-gal, and growing evidence suggests that this sensitivity can develop from a tick bite.

The post Red Meat Allergy from Tick Bites? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.April 12, 2022

Do You Really Need 10,000 Steps a Day?

Your fitness tracker encourages you to take 10,000 steps a day for better health. Does science support that?

The post Do You Really Need 10,000 Steps a Day? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

March 29, 2022

The US Healthcare Market Debate, Explained Through Economics

This article is part of an educational video series created by BUSPH student, Tasha McAbee, and health economist, Dr. Austin Frakt, to explain the intersections of economics and health. The transcript follows the video below, which can also be found on YouTube at Health Economics Explainers.

Everyone agrees that the US healthcare system is not working so great. Compared to the rest of the world, our healthcare is extremely expensive and yet we suffer worse health by many measures. And we can’t seem to agree on what’s to blame, or what we should do about it. Do we have too much, or not enough, competition? Should the government intervene in health care markets more or less?

Basic economics can help us better understand what’s happening.

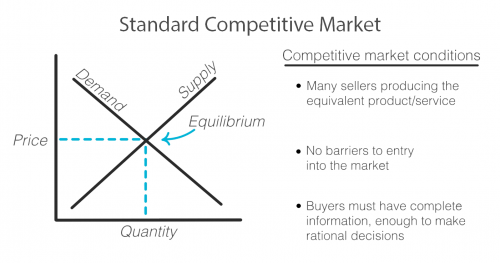

As with any exchange of goods and services, the standard competitive market model has the familiar upward sloping supply curve and downward sloping demand curve, illustrating that when prices are higher, demand decreases and supply increases as sellers are incentivized to produce more of that good or service at its higher price. Sellers and buyers arrive at what quantity to produce and consume and at what price based on where these two lines intersect, called the equilibrium. Both buyer and seller are happy with the deal they’ve struck!

But not every market works this way. There are actually standards that need to be met in order for a market to fit this model and for it to work efficiently for both the buyer and seller.

First, there must exist multiple sellers competing to sell the same goods or services and new sellers must be able to easily enter the market.

There must be a sufficient open exchange of information between buyer and seller about price, availability, and value of a service or good.

And buyers must make, or be in a position to make, rational decisions using the information they possess about the market.

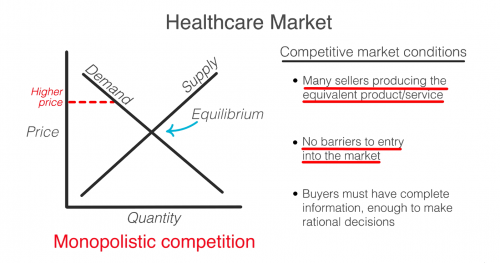

Healthcare does not meet these standards and when these standards are not met, the equilibrium cannot be reached or accurately known. Any price and quantity that falls outside of the equilibrium is considered a market failure. Using only this model, we can see how healthcare’s market failures contribute to high prices.

To start, it’s true that healthcare is failing the market standards when it comes to competition. The number of sellers in the market is decreasing due to both an increase in barriers to entry and due to consolidation, including hospital mergers. This causes an imbalance in power of the seller over the buyer that can begin to reflect what economists call monopolistic competition where sellers can charge a price above the perfect competition equilibrium. In the extreme, when there is only one seller, the market is a monopoly.

So then, don’t we just need more competition? Unfortunately, a lack of competition isn’t the only reason that healthcare fails the market standards.

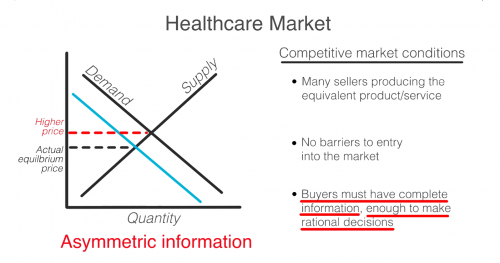

Another failure is that consumers in healthcare, patients, do not have all the information that providers, like doctors and hospitals, do. This is known as asymmetric information. Patients often have no idea before getting care how much it will cost, what the prices available to them elsewhere are, or what the quality will be. When consumers are in the dark about these basic features, the true demand and supply will be different than the model. The true demand may be lower if patients knew ahead of time how much it cost or how much less valuable the service is compared to how it is promoted. This means prices can be set higher than they likely would be if the true demand was known.

Even if patients had full information, they are not always in a position to act as rational consumers. A patient’s decision may be influenced by their concern for their health, or their ability to think rationally may itself be affected by their condition.

So, as you can see, the problem is that a lack of competition only accounts for part of the reason why healthcare doesn’t meet the market standards. No matter how much the government either steps back to allow for more competition or invests to foster competition, the market will never fix ALL of these failures on its own. Healthcare is not and can never be a free market. It simply does not fit this model.

In 1963, economist and later Nobel prize winner, Kenneth Arrow, warned us about this looming healthcare crisis. He explains that “If the actual market differs significantly from the competitive model […] coordination of purchases and sales must take place”

That coordination he is referring to is government intervention.

Dr. Mike Chernew, Health Economist and Professor of Health Policy at Harvard Medical School agrees…“an unregulated health care market is unlikely to lead to desired outcomes.”

In reality, health care always has, and always will, involve a combination of both government intervention and market forces to control prices and increase quality. The debate isn’t really whether or not the government should intervene, but by how much and in what way.

The post The US Healthcare Market Debate, Explained Through Economics first appeared on The Incidental Economist.One Million Dead

Sometime in late 2019, an outbreak of coronavirus-related pneumonia began in Wuhan, China. The first American case was reported on January 21. The WHO and the CDC warned of an impending pandemic in late February. On March 3, David States, Nicholas Bagley, and I wrote a TIE post predicting the severity of the pandemic. In this post, I will review what we got wrong.

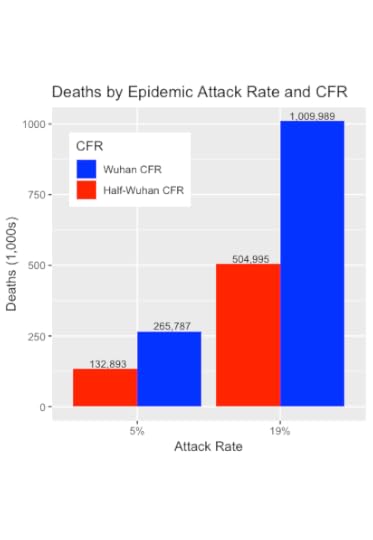

The key figure in our post is here.

The bars reflect our guesses about the epidemiological parameters driving the epidemic. Knowledge about them was highly uncertain at that time. Here’s what we said about this graph:

These numbers are shocking. Even under our most favourable scenario, roughly 133,000 people will die. Of greater concern, if we assume that US COVID-19 is half as lethal as the Wuhan data, then under a plausible 19% Attack Rate, there would be half a million deaths. Under the least favourable scenario, 1,000,000 will die.

Our prediction was wrong, but allow me to provide some context.

On the day we published that post there were only 6 confirmed US COVID deaths. There may have been other published predictions of the epidemic’s size, but I wasn’t aware of them. Knowledgable people derided us on Twitter; at least one, to his credit, wrote me later to apologize. Predictions soon appeared on other blogs. About two weeks later, for example, Richard Epstein of the Hoover Institute wrote that

The world is in a full state of panic about the spread and incidence of COVID-19.

Epstein thought that panic was unjustified because he was confident that only 5,000 Americans would die of COVID. A week later, he wrote that this was a typo and that he had intended to write 50,000 deaths. With that correction, he was only off by a factor of 20. At least we got the order of magnitude right.

Regardless, our prediction was wrong in three ways.

First and foremost, the pandemic in the US has been much worse than we predicted. The current count of confirmed deaths is nearly 1,000,000, at the top of our predicted range. Clearly, however, a BA.2 wave of COVID is coming. There is no reason to believe that that wave will be the last one and no reasonable argument that the final count — if there ever is one — will be ≤ 1,000,000. Moreover, the confirmed deaths count is a conservative estimate of the number of COVID deaths. A better gauge of the pandemic’s mortality, estimated excess mortality, exceeded one million months ago.

Second, the model we used to predict US COVID deaths was too simple. We just took a simple epidemic model and put in the estimates for the transmission rate of the infection and the age-specific mortality available from the early Wuhan data. David worked up a spreadsheet, which I translated into R over a weekend to capture the uncertainty in those data.

What was the model missing? A serious model would have tried to capture the social networks across which infections diffuse. We also missed the rapid evolution of the coronavirus, which has produced a series of new variants. Some of the new variants transmit faster than the alpha variant; others have some ability to evade the immunity conferred by either the vaccines or by previous exposure to coronavirus.

Finally, our prediction did not meet the Superforecasting standards for a good prediction, based on Philip Tetlock’s research. For example, we failed to give a specific date, as in “There will be at least X American COVID deaths as of date Y.”

When I ran the calculations for our prediction, I couldn’t believe them. The numbers of deaths were unthinkable. But the model said what it said, and we posted the results.

It is so sad that we were too optimistic.

The post One Million Dead first appeared on The Incidental Economist.March 28, 2022

What does getting covid cost, for international travelers?

Just something to think about, when considering international travel.The post What does getting covid cost, for international travelers? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Despite being fully vaccinated and boosted, I contracted Covid-19, but was actively sick only 36 hours. Unable to return to the US as originally scheduled, I needed to rebook and remain in Costa Rica for an additional 10 days. Fortunately, I could quarantine with family, so did not need to find and book a hotel. However, the costs of covid testing ($140), local transportation and domestic air fares ($359), hotel the night before flying ($188) and the increased cost of the rebooked international air fare ($360) drove the out-of-pocket costs for contracting covid to over $1000. Staying at a hotel for 10 days could add more than $1000 to that.

March 24, 2022

Cancer Journal: Nightmares

The Nightmare. J. Heinrich Füssli, 1781.

The Nightmare. J. Heinrich Füssli, 1781.I’m up again early in the morning, waking from another nightmare. Sometimes these dreams feature an assailant who rushes at me out of the dark. It’s as if I have been flung out of sleep. In others, I’m not threatened so much as trapped. For example, I recently dreamt that I had to give a lecture, but I was stuck in traffic and couldn’t get to the venue. Or anywhere else.

It’s wild that I would have problems sleeping now. I slept better when the tumour was growing like a pandemic case count. I dwindled as it grew: A tumour eats you from within. During the first stage of my cancer, it inefficiently consumed 20 kgs of me to attain the size of a ping pong ball. I slept well because I ended each day exhausted. Radiation, my first treatment, had the same effect. Now, with immunotherapy, the tumour is in retreat, and I am withered but recovering strength. But some nights I can’t sleep.

The nightmares could be nothing more than an immunotherapy side effect. Everything is tied to everything else in the body. A whole subdiscipline — psychoneuroimmunology — is devoted to how the immune system and the mind affect each other. There is, for example, a theory that stress leads to depression through inflammation and the immune system. Perhaps, then, pembrolizumab, the drug keeping me alive, causes these dreams.

However, maybe I am thinking through my future in my dreams. This is a task that my waking mind avoids. That’s not quite right: I understand that it is unlikely that I have been cured. It’s more likely that immunotherapy has knocked down my cancer, but hasn’t defeated it. In a few years, possibly just months, surviving tumour cells will evolve a strategy to circumvent the treatment, and then I’ll have another recurrence. Perhaps there will be a new medication I can take, or maybe the next recurrence will be the last one. I’ve lost several close friends to cancer; this is what happens.

However, it’s one thing to say that time is short and another to believe it. I don’t live as if I will be sick again: I spin out new projects as if I will see them through to completion. Tomorrow will be like today, or maybe a little better.

Except my dreams suggest that below my relentless self-improvement, I’m frightened. My dreams are wiser than I am. Cancer returns by smashing in the door. Suleika Jaouad wrote about she discovered that her leukemia had recurred:

When I returned home, the cough lingered. I couldn’t shake it for weeks. When I went in for routine blood work, my counts were low, and I was worried. My medical team said that if it would ease my mind, I could get a bone marrow biopsy, though the chances of my leukemia returning so many years later were extremely unlikely. I felt anxious and longed for an answer, so I pushed ahead and made the appointment [for a biopsy].

Jaouad’s experience — and mine — is that doctors discount signs that things are turning for the worse. My surgeon kept telling me that the CT scans showing recurrent tumour activity were false positives. Until a biopsy proved that they weren’t. The same happened to Jaouad.

[W]hen I got the biopsy results, it felt like a sinkhole opened up and swallowed everything. Within 72 hours, Jon and I packed our things, found friends to care for Oscar and Loulou, gave copies of our keys to our neighbor, cancelled work and cleared our schedules, and were on our way to the hospital in New York City. We haven’t been home since.

Likewise, just days after my biopsy confirmed the recurrence of my cancer, we were on the road, living in motels and a borrowed house. Not because the disease had bankrupted us — this is Canada, not the US — but because my Ottawa doctors told me they were out of care options, and I wasn’t ready to die.

We found an option, Deo gratias. My dreams tell me, however, that we’re not done. It’s a close-quarters battle, and the next time cancer breaks the perimeter, I want to be ready. I want a plan, and to that end, I have questions. Specifically,

How quickly will things fall apart if and when pembrolizumab fails?What treatment choices will I have, if any?And if there isn’t another great treatment option, when and how do we start palliative or hospice care?I need to plan which loved ones I need to see, what tasks I can finish, where I can get care, and how to marshal the funds to make all that possible.

Preparing patients to deal with treatment failure is not part of routine cancer care. I understand why. Oncologists have suffering patients who need care right now, and that’s a better use of time than talking with a patient in remission about what might happen in the future. Nevertheless, the only way to die well is to do it right the first time; you can’t learn from your mistakes.

Thor battling the monster in Midgard. J. Heinrich Füssli, 1790.

Thor battling the monster in Midgard. J. Heinrich Füssli, 1790.I’ve scorned the “fighting” metaphor because I can’t do anything to defeat cancer. Perhaps my immune system can be boosted by immunotherapy, but I’m just a witness if so. What I need to do is give up on “winning.” Recognizing that I will lose doesn’t mean I am giving up. I am arming myself to fight the long defeat.

If you know someone who has cancer, consider sending them a link to this post.To read the Cancer Journal from the start, please begin here.A table of contents for the Cancer Journal is here.To get the Cancer Journal in email, subscribe here.The post Cancer Journal: Nightmares first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers