Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 24

July 25, 2022

Covid Vaccine for Kids is Safe and Effective

The day has finally come: We have covid vaccines for kids under five. There are lots of questions and a few concerns. Let’s address them!

The post Covid Vaccine for Kids is Safe and Effective first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

Common Myths About Obesity

The obesity epidemic has received constant media attention for the better part of the twenty-first century. Unfortunately, much of the media coverage paints an inaccurate picture of obesity. I just published a Public Health Post article that examines the common myths surrounding the obesity epidemic; specifically, that BMI directly correlates to health, that obesity is the causal mechanism of illnesses, and that losing weight automatically improves your quality of life. The article argues,

Misinformation leads to ill-advised public health approaches to treating obesity. At least three quarters of media reports emphasize “individual responsibility” even though most scientific papers argue that obesity is the culmination of many factors often outside one’s control. The will-power myth and others lead to common misunderstandings of the role of weight in health.

One such myth is that body mass index (BMI) indicates healthy or unhealthy weight. Though it incorporates height and weight, BMI is an inaccurate predictor of health. This is especially true for people of color, because BMI thresholds were based on Western European body types. BMI also does not account for weight distribution, nor can it differentiate between adipose tissue and muscle.

Read the full piece here!

Research for this piece was supported by Arnold Ventures.

The post Common Myths About Obesity first appeared on The Incidental Economist.July 15, 2022

Abortion Access and Public Health

Health policies, including those related to abortion, should be guided by data. So what do the data have to say about restricting abortion access? How might it impact public health in the United States and what are some of the best ways to approach the issue?

The post Abortion Access and Public Health first appeared on The Incidental Economist.July 12, 2022

The missing Americans: early death in the United States 1933-2021

Jacob Bor, Andrew C. Stokes, and Julia Raifman are faculty at Boston University School of Public Health. Atheendar Venkataramani is faculty at the University of Pennsylvania. Mary T. Bassett directs the François-Xavier Bagnoud (FXB) Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard School of Public Health and is the Commissioner of the New York State Department of Health. David Himmelstein and Steffie Woolhandler are Distinguished Professors at Hunter College, City University of New York, and faculty at Cambridge Health Alliance/Harvard Medical School. The paper does not necessarily reflect the views of the NYS Department of Health or any of the authors’ institutions.

COVID-19 led to a large increase in U.S. deaths. However, even before the pandemic, the U.S. had higher death rates than other wealthy nations. How many deaths could be avoided if the U.S. had the same mortality rates as its peers?

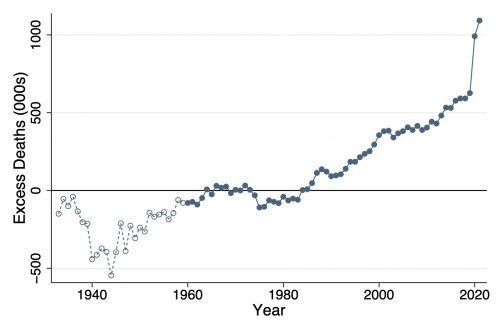

In a new study, we quantify the annual number of U.S. deaths that would have been averted over nearly a century if the U.S. had age-specific mortality rates equal to the average of 18 similarly wealthy nations. We refer to these excess U.S. deaths as “missing Americans.”

The annual number of “missing Americans” increased steadily beginning in the late 1970s, reaching 626,353 in 2019 (Figure). Excess U.S. deaths jumped sharply to 991,868 in 2020 and 1,092,293 in 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure. Excess deaths in the U.S. relative to other wealthy nations, 1933-2021. Source: Human Mortality Database. Note: Figure shows the difference between the number of deaths that occurred in the U.S. each year and the number of deaths that would have occurred if the U.S. had age-specific mortality rates equal to the average of other wealthy nations. The comparison set includes Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. The average of other wealthy nations excludes Portugal prior to 1940, Austria and Japan prior to 1947, Germany prior to 1956, and Luxembourg prior to 1960. From 1960, all countries are represented (solid dots).

Figure. Excess deaths in the U.S. relative to other wealthy nations, 1933-2021. Source: Human Mortality Database. Note: Figure shows the difference between the number of deaths that occurred in the U.S. each year and the number of deaths that would have occurred if the U.S. had age-specific mortality rates equal to the average of other wealthy nations. The comparison set includes Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. The average of other wealthy nations excludes Portugal prior to 1940, Austria and Japan prior to 1947, Germany prior to 1956, and Luxembourg prior to 1960. From 1960, all countries are represented (solid dots).In 2021, nearly 1 out of every 3 U.S. deaths would have been averted if U.S. mortality rates had equaled those of its peer nations. Half of these excess deaths were among U.S. residents under 65 years. We estimate that the 1.1M excess deaths in 2021 were associated with 25M years of life lost, accounting for the number of years the deceased would otherwise be expected to live.

We also compared mortality rates of U.S. racial and ethnic groups with the international benchmark. Black and Native Americans accounted for a disproportionate share of the “missing Americans.” However, the majority of “missing Americans” were White non-Hispanic persons.

Our findings are consistent with recent reports that the life expectancy gap between the U.S. and peer nations widened during the pandemic, with U.S. life expectancy falling from 78.9 to 76.6 years. Life expectancy is widely reported, but it is a complex measure and may be misinterpreted as reflecting small differences in mortality at advanced ages.

In fact, the greatest relative differences in mortality between the U.S. and peer countries occur before age 65. In 2021, half of all deaths to U.S. residents under 65 years – and 90% of the increase in under-65 mortality since 2019 – would have been avoided if the U.S. had the mortality rates of other wealthy nations. In addition to the loss of life, these early deaths often leave behind child (and elder) dependents without key social and economic support.

Our calculations were based on recently released mortality data, obtained from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WONDER Database and the Human Mortality Database. The international comparison group included all available countries with relatively complete mortality data starting in 1960 or earlier, after excluding former communist countries. Our paper builds on prior analyses of excess deaths by our study team and by others.

We find a very large increase in excess U.S. deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, this spike occurred on top of a growing trend that reached 600,000 excess deaths in 2019. Future COVID-19 deaths could be reduced with broader vaccine uptake, worker protections, and masking during surges. Even if COVID-19 mortality were eliminated, however, the U.S. would likely suffer hundreds of thousands of excess deaths each year, with many linked to firearms, opioids, and obesity.

Addressing excess deaths in the U.S. will require public health and social policies that target the root causes of U.S. health malaise, including fading economic opportunities and rising financial insecurity, structural racism, and failures of institutions at all levels of government to invest adequately in population health.

The post The missing Americans: early death in the United States 1933-2021 first appeared on The Incidental Economist.July 1, 2022

Gun Violence as a Public Health Issue

Gun violence is a public health problem, but we don’t approach it like one. The debate often gets framed as “guns or no guns” when it isn’t that black and white. In this episode we break down how and why to approach gun violence as a public health problem, what the current research has to say, and what we need to move forward.

The post Gun Violence as a Public Health Issue first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

June 28, 2022

The impact of housing on childhood asthma

Over four million children in the United States have asthma but it doesn’t affect them all the same. Often, it depends on where they live.

Social determinants of health — factors like where one works, lives, and plays — are finally getting the attention they deserve. It’s becoming clear that much of a person’s health depends on social determinants, not the doctor’s office.

For kids with asthma, the physical environment is especially important. Some of the most common allergen triggers are pests, mold, and dust, which are all routinely found at home and at school. Keeping these kids healthy depends on creating and maintaining healthy built environments.

But housing inequities are all too common. The Boston Globe recently spotlighted new research showing racial disparities in the quality of Boston housing. The asthma triggers mentioned above were more common in low-income, minority neighborhoods and there were more submitted inspection requests from those neighborhoods than from affluent ones.

This new research complements previous studies that show the impact of historical housing policies on the quality of current housing and health. Redlining, banning multiunit housing, and other policies limited the quantity and quality of housing available to minority families. The consequences are still felt today as those neighborhoods tend to be more run down.

Another inequity is the cost of home-based asthma prevention. Families are often told run the air conditioning instead of opening the windows, to buy dust mite covers for beds and pillows, to vacuum every day, to fix any leaks or mold issues; the list goes on. For low-income families, complying can be quite challenging.

However, the evidence is clear that improving a child’s living environment really does improve his health and is actually cost-effective in the long run.

To do so while also addressing inequity will require community partnership.

The Community Asthma Initiative through Boston Children’s Hospital is a great example. For kids with asthma who have had emergency department (ED) or inpatient visits, the program conducts in-home repairs or improvements geared towards the child’s specific asthma triggers. Children see a significant reduction in asthma-related hospitalizations and ED visits and missed school days. What’s more, the program costs are fully recovered within a few years.

The Community Asthma Prevention Program Plus, through Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, is similar. When the program completed comprehensive repairs for the first cohort of families, the parents reported a significant reduction of asthma triggers in the home and asthma-related ED visits and hospital stays.

But community partnership isn’t enough. We also need policy change.

Housing codes should be revisited. Routine pest and mold inspections — and mitigation — should be required and landlords should be obligated to fix structural issues quickly. Inspection processes should also be reviewed. When tenants submit complaints, are there enough inspectors to address them quickly? How does the city hold landlords accountable to make necessary improvements? Tenants should feel safe to submit complaints and assured that the underlying structural issues will be addressed.

Lastly, and simply put, homeownership must be attainable. Tenants have far less authority over their living spaces than homeowners do. But if homeownership is an impossible dream — given the market or historically discriminatory policies — families who rent will continue to be beholden to their landlords for the health of their homes.

So much of a child’s health depends on where she lives, plays, and learns. Expanding the conversation about childhood asthma beyond the doctor’s office is critical. The goal is to keep kids out of the hospital and on the playground. Getting there starts at home.

The post The impact of housing on childhood asthma first appeared on The Incidental Economist.100% Remission Rate in Rectal Cancer Drug Trial

Recently, a small trial of a drug for colorectal cancer saw a 100% remission rate. That means ALL the people in the study who received the drug experienced a remission of their cancer. It’s a small trial, and more study is needed, but this kind of result is unprecedented.

The post 100% Remission Rate in Rectal Cancer Drug Trial first appeared on The Incidental Economist.June 21, 2022

Healthcare Triage Series: Drug Approval in the United States

With support from the National Institute for Health Care Management, we’ve created a three-episode series focused on how drugs get approved in the United States. In the first episode, we discuss the drug approval process from the discovery phase all the way to what happens after its approval. In the second episode, we discuss the exceptions along that pathway. And in the third and final episode, we discuss recent, related controversies.

The post Healthcare Triage Series: Drug Approval in the United States first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

June 15, 2022

Focusing on the impacts of social determinants among the Medicare Advantage population is good – but it might be too late

Social factors impact a person’s health and their potential health outcomes. While this has long been discussed (especially by folks of color, individuals with lived experiences, and those in public health), it is finally now getting deserved mainstream attention, including by health insurers.

Medicare Advantage (MA) — a program that offers private plan alternatives to traditional Medicare — is one key player looking at social determinants of health. It’s a good thing, too; an estimated 42% of the Medicare population are enrolled in MA plans, and that share grows each year. MA plans have more flexibility in offering supplemental benefits and services, some of which can address social determinants of health.

In 2018, the Creating High-Quality Results and Outcomes Necessary to Improve Chronic (CHRONIC) Care Act passed with bipartisan support and marked a substantial shift in MA policy by including acknowledgment of the role of social determinants of health. It allows even greater flexibility for MA plans to help with the very conditions that impact how a person lives, such as providing financial assistance for nutritional needs, transportation to appointments, caregiver support, and even home construction projects. Interestingly, it does not mandate coverage, so it is still dependent on what plans an individual has access to and how health plans are choosing to move forward with this freedom.

The problem is, however, that most individuals aren’t eligible for Medicare until age 65 (there are some exceptions). If we wait until Medicare eligibility to act on social determinants of health, are we waiting too long?

The short answer is yes. Although addressing social determinants of health in the Medicare-eligible population is important, what we know suggests that more could be done earlier.

Why are social determinants important in Medicare Advantage?

Chronic disease is a significant issue among Medicare-eligible individuals, and one that’s exacerbated by social determinants of health. There are substantial implications for both beneficiaries and MA plans. For beneficiaries, chronic disease affects not only their quality of life, but also their wallet. From the plans’ perspectives, the presence of comorbid chronic diseases is a significant differentiator between so called “high cost” beneficiaries and those who are not.

Current MA enrollment trends also point to the need to sharpen the focus on social determinants of health. Although they make up a minority of MA enrollees, persons of color are enrolling in MA plans at a breakneck pace: especially among Black people, dual enrollees, and people living in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Historically, these are folks most negatively impacted by social determinants of health, and the likelihood of poor health outcomes is only compounded when enrollees reside in disadvantaged neighborhoods. These are neighborhoods commonly characterized by high concentrations of poverty, crime, and harmful environmental exposures compounded by limited resources to support economic and social well-being, and research has consistently found strong associations between neighborhood disadvantage and health risks and outcomes.

Health systems must do more about social determinants earlier in life

Social determinants of health affect us all — regardless of age. Until recently, they have received relatively little attention from insurers.

However, that’s changed in recent years. Insurers are making investments in affordable housing, funding research into food insecurity, and some are even willing to help their members pick up the tab on their internet bill.

It is difficult though to discern the extent that these actions are altruistic or opportunistic, especially when they can technically be both. While that might not be the worst thing, it does matter if it leaves out the very people it should be helping.

Let’s consider internet access, for example. If a patient isn’t connected to the web, they can’t participate in a telehealth visit, leaving in-person care as the only option. In a world where telehealth visits are reimbursed at a fraction of the in-person rate, there are substantial cost savings (read: profit) associated with facilitating and promoting virtual care. Critics have also pointed out that most of these steps can be attributed to insurers’ philanthropic apparatuses as opposed to any substantive change or innovation in member benefits.

What is also becoming readily apparent, is that while telehealth use is increasing, it does not make care accessible for everyone. It could even serve to increase disparities if it is not done properly.

Beyond insurance, there are several existing programs that aim to address social determinants of health and are accessible earlier in a person’s life cycle. Programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Early Intervention, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or even the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program can be a lifeline for those most in need.

However, administrative hurdles and societal stigma can challenge people’s willingness to participate in these programs no matter how beneficial they might be. We should all be asking what more the health system — providers, payers, and government — should be doing to improve social determinants of health earlier in life.

The CHRONIC Care Act has the potential to mitigate some of these harmful impacts of long-standing structural inequities by providing greater flexibility for plans to cover non-medical needs. The law illustrates that policymakers believe that health insurers should do more to address social determinants of health. Perhaps they should also focus on how plans can address these social factors earlier in the life cycle as well.

Research for this piece was supported by Arnold Ventures.

The post Focusing on the impacts of social determinants among the Medicare Advantage population is good – but it might be too late first appeared on The Incidental Economist.May 31, 2022

A Dedication to Mental Health Awareness Month

May was Mental Health Awareness month, and in honor of that, Healthcare Triage devoted all four of its May episodes to research on treatments for depression. We covered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Mushrooms, Ketamine, and Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. Check them out below:

The post A Dedication to Mental Health Awareness Month first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers