Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 29

February 1, 2022

That Pricey New Alzheimer’s Drug? Still Not Great

We really need good treatments for Alzheimer’s. But Biogen’s very expensive (and maybe not very effective) drug Aduhelm is not the treatment we’re looking for. Today we look at the saga of Adulhelm’s approval and its road to acceptance (or lack thereof) in the medical community.

The post That Pricey New Alzheimer’s Drug? Still Not Great first appeared on The Incidental Economist.January 29, 2022

My take on responding to reviewer comments

This is an edited version of a recent Twitter thread, which will auto-delete after a year (the thread, not this post).

Responding to reviewer comments is my favorite part of academic writing. I have an excellent revision accept rate and am also a journal editor and reviewer, so I thought I’d share my reviewer response letter techniques, for what it’s worth. The following is what I do and advise and has never caused me difficulty.

First, I write the response to reviewer letter, and get input on it from my coauthors, before I revise the manuscript. The letter is my revision roadmap. Second, I always write a letter, not create a table. I think it is easier to read. As an editor and reviewer, I do not like a table layout for the revision letter, acknowledging that others may love it (I dunno).

Here’s how I write that letter:

1. Paraphrase, Part 1: I paraphrase reviewer comments and acknowledge that I am doing so. This gives me the freedom to (a) cut out useless stuff and (b) focus the editor and reviewers on action items. I have reasons for doing this (below), but I want to point out that others take or advise or have been advised a “full quote” approach (see this tweet and this one). A middle way, and essentially what I end up doing anyway, is to directly quote the actionable parts of review comments and leave out the throat clearing and stuff that doesn’t suggest what to do.

Why paraphrase or at least quote only actionable parts? A lot of what reviewers write you don’t want to remind them of and isn’t actionable anyway. E.g., “I had a hard time reading this paper.” Or, “I was initially troubled with the general approach.” Or, “While this topic doesn’t interest me, it may still be suitable for the journal.” Or, “[Insert very long paragraph of background with no action item for you.]”

Whatever! Not actionable. Not helpful to remind them of their prior, negative or irrelevant thoughts. Cut it!

Also, my main revision strategy is to make the letter super easy to read, but also self-contained — more on that later. Paraphrasing (or quoting only action items) goes a long way to tightening it up and reducing editor/reviewer (and coauthor) burden. It’s good for everyone, in my view. If you acknowledge you’ve done this up front, the editor can always ask you to put in full quotes. This has never, ever happened to me, but YMMV.

2. Paraphrase, Part 2: I never directly quote passages of my revised manuscripts in my letter. Why? It’s a pain to keep the quote in the letter the same as the revised paper as you go through revisions with coauthors. Instead, I paraphrase the changes in my letter.

Another reason: there’s a bit of artistry here. If a reviewer makes a comment that is reasonable enough to warrant an edit, but I feel really can be done in a more terse manner or slightly differently than the reviewer suggested, or if there’s just a lot of background I’d like to add to the letter but not to the specific change in the manuscript, I can do that and then say, “We have incorporated these ideas [meaning the ones the reviewer just stated or I just described] by augmenting the language in the [say where].”

See what I did there? The reviewer gets the full load of context and I reassure the reviewer that the ideas are incorporated, but the actual change may be modest. If I were to quote it in the letter, it could look insubstantial. I don’t want to give that impression.

But also, I always paraphrase or describe changes for every comment in the letter because I want the letter to be self-contained. I do not want the editor/reviewers to scrutinize the manuscript looking for how I changed it in response to a comment. Every second of additional scrutiny can raise new concerns! I don’t want that!

I want them to read the letter and think, “This looks good, I’ll sign off!” A good letter can do that. One that doesn’t say how the manuscript was changed is effectively telling the editor/reviewer to go do more work. You don’t want to do that! It is annoying to them, which is not in your interest.

Further pro tip: I do not, in the letter, reference changes in the manuscript by page number. Why? The page numbers won’t always be the same in the package reviewers get and/or the number of the PDF can be different than the numbers you put on the pages (maybe you didn’t number the title page or something) — it’s confusing. Plus, stuff can shift as I revise and I don’t want to get the page number wrong. I just say where the change is in the structure (Intro, Methods, etc. or 3rd paragraph of Results or whatever). Simple. Fool proof.

3. Unique Numbers: I uniquely number every (actionable!) reviewer comment. It doesn’t matter how they numbered them, if at all, or organized them, if at all. Some give three actions in one comment. I split them up and uniquely number. I use a system like E-1, E-2, … for the editor’s comments; 1-1, 1-2, 1-3 for reviewer 1; 2-1 2-2, 2-3 for reviewer 2, etc. (Exception: If a reviewer gave a long list of minor edits, I bundle them and just say I addressed them all.)

Why unique numbers? Many comments are duplicative. With unique numbers you can avoid duplicating yourself. Just refer back or forward by number. “See our response to 2-3” etc. Never type the same response twice! This is a burden for you, to keep them consistent, and a burden on the reader. You don’t want to burden the reader (editor/reviewer)!

Another use of unique review comment numbers that I’ve employed is to add comments with the numbers in the revised manuscripts where I’ve addressed each one. That is, where I added text to address comment 2-3, I make a comment, “Response to 2-3.” This is useful to make sure I addressed every comment with some kind of change to the manuscript. When I’m iterating between letter and manuscript it helps me keep them synced up. Admittedly, I don’t always use the comment numbers this way or always insist that advisees do so. But it can be helpful. (I remove these comments when I’m done, before submitting, though there really isn’t anything bad that is likely to happen if they were left in. Perhaps reviewers would like them.)

4. Fully Responsive: I am responsive to every comment. What is a response? This is an art. It’s everything I can think of within reason and within scope of the paper and that isn’t likely to raise new objections. Mostly it’s doing substantially more than just saying, “No we won’t.” (I call that giving a reviewer the “stiff arm.” It doesn’t feel good to them, so I don’t do it because I want them to like me and my paper.) That doesn’t mean do stupid stuff. At the least I explain why I considered the suggestion and decided against it, or refer the reviewer elsewhere for support for my view, etc.

5. Be Nice: I’m often angry at reviewers initially. That’s OK! I get through it by letting it out in a mean letter first. I write what I really think of their ideas or how they clearly didn’t read the paper! But, that’s just for me. I then revise it taking the more appropriate and professional high road. I express gratitude for every comment (with different language): “Thank you.” “Good idea.” “We concur.” “We apologize for the oversight.” “What a thoughtful suggestion.” “We appreciate the consideration you’ve given this.” “That initially occurred to us too. [Good for when you need to explain why it won’t work.]” “That’s a reasonable idea.” “Yours is an innovative suggestion.” …

Bottom line: Make the letter as concise, yet thorough, as possible, while ensuring it is self-contained, easy to follow, and kind/generous. That’s about it. (Even if you feel you need to fully or partially exactly quote the review comments, you can do all the rest and it will likely help!)

The post My take on responding to reviewer comments first appeared on The Incidental Economist.January 25, 2022

Who benefits from Medicaid Expansion? Hint: Everyone

Medicaid is an integral component of the United States’ health and social safety net, serving the most vulnerable members of society. The Affordable Care Act allowed states to expand Medicaid coverage to previously ineligible populations, though there exists a sizable contingent of states that have opposed doing so.

Most research considers the impact Medicaid expansion has on newly eligible enrollees. Far less is known about the ripple effect expansion has on individuals who were already enrolled. In Tradeoffs, TIE contributing author, Paul Shafer, discusses new research that explores exactly that in Louisiana:

[The authors] used Medicaid claims data to measure the distance traveled from patients’ homes to different care providers before and after expansion. They found that travel distance decreased across the board…The declines were even more pronounced among Black rural Medicaid enrollees, whose trips were on average nearly 10 miles shorter for general practice and 3 miles shorter for primary care after expansion.

Read the full piece here!

Research for this piece was supported by Arnold Ventures.

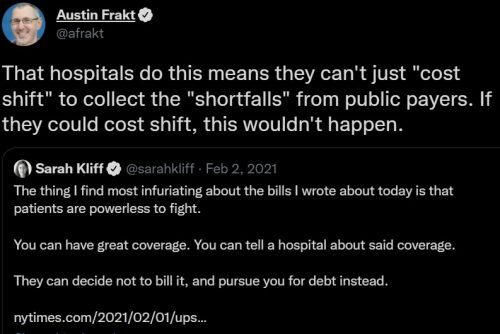

The post Who benefits from Medicaid Expansion? Hint: Everyone first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Cost shifting catch up

Looks like every 6-18 months or so I have enough fodder assembled to warrant a round up of cost shifting claims or takedowns. Here’s the latest:

1. Barack Obama in the New Yorker in November 2020:

Unable to afford regular checkups and preventive care, the uninsured often waited until they were very sick before seeking attention at hospital emergency rooms, where more advanced illnesses meant more expensive treatment. Hospitals made up for this uncompensated care by increasing prices for insured customers, which further jacked up premiums.

2. My tweet last February (which will auto-delete shortly*) about a Sarah Kliff piece:

3. Sherry Glied in JAMA Health Forum in June 2021:

The cost shifting theory persisted for a long time without being examined very rigorously. […] Economists [didn’t believe it] because it is difficult to come up with a rational economic model of cost shifting, but their objections were drowned in a flood of anecdotes.

In the mid-2000s, data on private payments began to become available. A series of studies by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission and by academic economists found that hospitals did not cost shift. On the contrary, when public insurers reduced their payments, private insurance payment levels tended to decline as well.

4. Michael Chernew, Hongyi He, Harrison Mintz, and Nancy Beaulieu in Health Affairs in August 2021:

We raise the possibility of “consolidation-induced cost shifting,” which recognizes that changes in public prices for hospital care can affect market structure and, through that mechanism, affect commercial prices. We investigated the first leg of that argument: that public payment may affect hospital market structure. After controlling for many confounders, we found that hospitals with a higher share of Medicare patients had lower and more rapidly declining profits and an increased likelihood of closure or acquisition compared with hospitals that were less reliant on Medicare. This is consistent with the existence of consolidation-induced cost shifting […]

5. Congressional Budget Office in January 2022:

The share of providers’ patients who are covered by Medicare and Medicaid is not related to higher

prices paid by commercial insurers. That finding suggests that providers do not raise the prices

they negotiate with commercial insurers to offset lower prices paid by government programs (a

concept known as cost shifting).

6. An American Enterprise Institute report by Benedic Ippolito, Loren Adler, and Conrad Milhaupt:

Do drugmakers "revenue target"?

After big revenue losses due to biosimilar entry in the EU but not US, we don't see offsetting revenue increases in the US.

This suggests that drugmakers similarly wouldn't be able to cost-shift after Medicare regulation.https://t.co/npV08XYv71 pic.twitter.com/MTrU0Cbe1G

— Loren Adler (@LorenAdler) January 18, 2022

* I use TweetDelete to delete tweets after a year.

The post Cost shifting catch up first appeared on The Incidental Economist.January 17, 2022

Addressing structural racism at Health Services Research

For much of the past year, the editors and editorial board of Health Services Research (HSR) have been refining goals and action items to identify and address structural racism at the journal. Today, I am pleased to announce that a report documenting those goals and action items is available online.

Accompanying the report is a shorter editorial that summarizes its contents. Both the report and editorial list our goals as follows:

For HSR to be equitable and accessible to the entire health services research community — from editorial positions to reviewer roles to publication in our journal.In reviewing and publishing manuscripts, for HSR to be consistent, fair, and objective in how it handles “race” and “ethnicity” however they arise (e.g., as a control variable, a main focus, etc.).For HSR to be intentionally and transparently receptive to scholarship on structural racism as an underlying driver of inequities.In addition, HSR has released today an open call for papers on topics in inequities due to marginalized social identities.

While the ideas in all three documents were shaped by the minds of many, I want to particularly thank HSR Senior Associate Editor Dr. Monica Peek for partnering with me in putting these ideas into the words that appear in them.

The post Addressing structural racism at Health Services Research first appeared on The Incidental Economist.January 16, 2022

Problems with EPA Pollution Reporting

While we’re all probably aware that we’re sometimes exposed to air pollution in one way or another, we generally assume that some official (you know, like from the EPA) is keeping tabs on it to make sure it isn’t excessive. However, a recent analysis of EPA data suggests that for those of us living in certain areas, the risk is much higher than we think.

The post Problems with EPA Pollution Reporting first appeared on The Incidental Economist.January 11, 2022

Too Many Kids are Uninsured or Underinsured in the US

Access to healthcare in childhood has long term effects on health outcomes, but many children in the US are either uninsured or underinsured, meaning they often don’t have access to the care they need. Why is that and what can we do about it?

The post Too Many Kids are Uninsured or Underinsured in the US first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

January 5, 2022

Call for Abstracts: Reproductive Wellness for Women with Chronic Conditions

This call is also posted on the Health Services Research website.

Sponsored by: The WK Kellogg Foundation

Submission deadline for abstracts: February 4, 2022

With sponsorship from The WK Kellogg Foundation, Health Services Research (HSR), the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) Jordan Institute for Families and the UNC Collaborative for Maternal and Infant Health are partnering to publish a series of special sections of upcoming issues focused on reproductive wellness for women with chronic conditions. The special sections will be edited by HSR’s team of Senior Associate Editors and Editor-in-Chief, with co-editor guidance from Sarah Verbiest, DrPH, MSW, MPH, and Natalie Hernandez, PhD, MPH.

These special sections will focus on reproductive wellness and preconception care for women with chronic conditions. Recent work listening to women of color with chronic conditions has underscored many gaps in care. These gaps contribute to maternal mortality and morbidity, infertility, miscarriage and infant loss, and long-term health impacts for women and their families. We are seeking to curate a series of articles, to be published in a special section across several regular HSR issues, that will highlight work being done across a variety of sectors — health care, public health, social work, community leadership, maternal and child health, chronic disease, and others — that offers solutions and strategies toward improving care.

We hope to receive abstract proposals from a range of disciplines and organizations, including community-based organizations and community leaders. From abstracts received, the editors will invite manuscripts, which will undergo peer review. Topics of interest include qualitative analysis of experience of care; quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods research revealing outcomes of current models of care, promising practices, partnership approaches, or strategies to foster equity; exploration of new data or measurements pertaining to reproductive wellness for women with chronic conditions. Articles may include in their discussions evidence-based recommendations for systems and/or policy change. We welcome abstracts from community-led organizations. If the abstracts are moved forward, the UNC Jordan Institute for Families can offer some writing assistance for these organizations. Geographically, articles should be focused on studies or initiatives within the United States. All articles in the special sections will be open access.

The deadline for abstract submissions is February 4. Abstracts may not exceed 300 words and must be formatted as indicated in the HSR Author Guidelines. These abstracts will be evaluated by a multidisciplinary review panel that will select authors to receive invitations to submit full manuscripts. The evaluation criteria will include: (1) responsiveness to the themes articulated in this call; (2) quality, rigor and originality; and (3) significance and usefulness for advancing knowledge.

Manuscripts invited for submission will undergo the same HSR peer review process as all regular manuscripts. All accepted articles will be published electronically within a few weeks of acceptance using Wiley’s Early View process. Articles published through Early View are fully published, appear in PubMed, and can be cited. Approximately 12 articles will be subsequently selected for print publication in a special section of a regular issue of HSR that will appear in several issues between December 2022 and December 2023. Accepted manuscripts that are not selected for the Special Sections will be automatically scheduled for print publication in a regular issue.

Key dates for authorsFriday, February 4, 2022: Abstracts submission deadlineFriday, March 4, 2022: Notification of manuscript invitationFriday, June 3, 2022: Manuscripts submission deadlineDecember 2022-December 2023: Publication of manuscripts in special sections of regular HSR issuesIf you would like to submit your abstract for consideration, please email your abstract and co-author contact information to the editorial office at hsr@aha.org, using the subject line “Special Section on Reproductive Wellness for Women with Chronic Conditions.”

The post Call for Abstracts: Reproductive Wellness for Women with Chronic Conditions first appeared on The Incidental Economist.January 4, 2022

Special Issue Call for Abstracts: Advancing a Culture of Health

This call is also posted on the Health Services Research website.

Special Issue of Health Services Research: Advancing a Culture of Health — Research from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Policy Research Scholars

Sponsored by: The Health Policy Research Scholars, a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Submission deadline for abstracts: February 4, 2022

Health Services Research (HSR) and the Health Policy Research Scholars (HPRS) program are partnering to publish a Special Issue on advancing a Culture of Health. The special issue will be co-edited by Monica Peek, MD, MPH, MS, Som Saha, MD, MPH, and Attia Goheer, PhD, MHS.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) is working alongside other organizations to build a national Culture of Health that provides everyone in America a fair and just opportunity for health and well-being. The Foundation supports several national leadership development programs to help train a generation of leaders who will use innovative approaches to advance a Culture of Health.

HPRS is one of these leadership programs. HPRS is a four-year program for doctoral students from historically marginalized backgrounds or who are underrepresented in their discipline and who want to improve health, well-being, and equity; challenge long-standing, entrenched systems; exhibit new ways of working; collaborate across disciplines and sectors; and bolster their leadership skills. By providing training in health policy, how to think strategically, and how to craft an actionable research question that can inform solutions to advance health equity—as well as mentorship and coaching — HPRS will develop a new cadre of research leaders who will build a Culture of Health in their disciplines and communities.

The goal of this Special Issue is to highlight impactful, innovative, and rigorous work from the HPRS community, with no restriction on professional or scholarly discipline, that can inform how to change systems and policy to advance a Culture of Health. The Special Issue will feature original research or methods articles and a limited number of evidence-based commentaries (see HSR Author Instructions for details). Questions about potential articles that do not fit these categories should be directed to hprs@jhu.edu.

We are interested in work that represents a range of disciplines and topics that are salient to advancing a Culture of Health. A critical aspect of a Culture of Health is health equity, so we also encourage papers that address barriers and opportunities for enabling everyone to live their healthiest life possible. Illustrative examples of the types of research projects that would align with the theme for this Special Issue include:

Examining efforts to dismantle structural racism in an organization and its impact on wellbeing and mental health.Exploring the role of civic engagement (e.g., voting, volunteerism) in promoting community well-being.Evaluating the health impact of policies that support collaboration between law enforcement and communities.Measuring walkability and safety hazards by neighborhood income.Studying Black women’s access to substance use treatment.Analyzing the impacts of COVID-19 on learning for school-aged children of color.Though we will consider work focused on populations and programs outside of the United States, we encourage authors to incorporate lessons for the U.S. as part of the broader discussion.

Abstract Submissions

The deadline for initial submission of abstracts is February 4, 2022. Abstracts may not exceed 500 words. Abstracts for research and methods articles must follow the structure outlined below:

Background, including the objective or study questionMethods and study design, including, as appropriate, data sources, geographic setting, time frame of the data collection, and eligibility and exclusion criteriaPrincipal findings, including, if applicable, numerical results with appropriate indicators of uncertainty such as confidence intervalsRelevance of this work to building a Culture of HealthConclusionsUnstructured abstracts still limited to 500 words will be accepted for commentaries only. Abstracts must address the relevance of the work to building a Culture of Health.

The lead author on each abstract submission must be an HPRS scholar or alum. Additional authors (e.g., faculty, community partners) need not be affiliated with the program. Scholars and alums may submit multiple abstracts as first author.

Abstracts will be evaluated by the co-editors of the special issue to determine which are invited to submit full manuscripts. Evaluation criteria will include: (1) quality, rigor, and originality; (2) relevance to the special issue theme, articulated above; and (3) clarity of writing and presentation.

If you would like to submit your abstract for consideration, please email your abstract and corresponding author contact information to the editorial office at hsr@aha.org. Include “Special Issue HPRS” in the subject line.

Invited Manuscripts

Manuscripts invited for submission to the Special Issue after abstract screening will undergo the same HSR peer review process as regular manuscripts. A primary goal is to publish the vast majority (if not all) of the invited manuscripts. This will, however, necessitate that we invite a smaller number of authors to submit full papers than is usual for an HSR special issue, and that we have a very high level of commitment from those submitting abstracts. To maximize the successful production of rigorous science, scholars will be paired with mentors, either self-identified or matched from faculty at Johns Hopkins, the editorial review pool at HSR, or other sources of senior faculty.

The print publication date for the Special Issue will be June 2023. Manuscripts will be published online ahead of the print edition once accepted. Accepted manuscripts that are not selected for the Special Issue will be scheduled for print publication in a regular issue of HSR.

Key dates for authors

Friday, February 4, 2022: Submission deadline for abstractsFriday, March 18, 2022: Notification of manuscript invitationFriday, June 17, 2022: Submission deadline of invited manuscriptsJune 2023: Print publication dateFor questions, please email hsr@aha.org and include “Special Issue HPRS” in the subject line.

The post Special Issue Call for Abstracts: Advancing a Culture of Health first appeared on The Incidental Economist.January 3, 2022

Cancer Journal: The COVID Pandemic on New Year’s Day, 2022

We travelled to the US over Christmas to see our children and our new grandchild. We were struck by the profound differences between Canada and the US in how the pandemic has played out, and I want to reflect on them here.

Canada is far from perfect, but in Ottawa, at least, people in stores are uniformly masked. You need to show proof of vaccination to board a plane or enter a theatre or restaurant. Regulations tighten quickly during epidemic waves. Most people still respect 2-meter social distancing. We had large groups of unmasked people crowding into elevators in the US. What the hell were they thinking?

Perhaps I’m oversensitive. I am 68 and a cancer patient, so I am at high risk from COVID. Not, however, because cancer has made me immunocompromised. My immune system holds my tumour at bay, thanks to immunotherapy. The problem is that severe COVID can lead to bacterial lung infections. I can’t take antibiotics while I take my immunotherapeutic medication. Therefore, if I got COVID-related pneumonia, I’d have to stop the immunotherapy, unleashing my tumour.

So, let’s talk about what the US and Canada have experienced during the pandemic. On March 3rd, 2020, David States, Nick Bagley, and I posted some projections for the possible course of the pandemic in the US. Applying elementary epidemiological models to the early data from Wuhan, we predicted that the US would experience somewhere between 0.5 and 1 million deaths. Many derided our projection, which was far higher than some others at that time. For example, two weeks after we published, law professor Richard Epstein predicted 500 US deaths.*

Sadly, we were correct. On New Year’s Day, 2022, the cumulative total American COVID deaths was 825,536. This is more than twice the number of American casualties in the Second World War. More Americans have died of COVID than AIDS in the 40 years since the latter was identified.

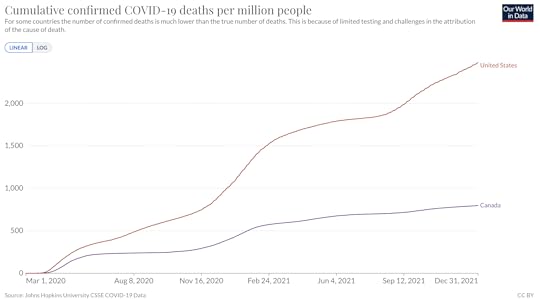

Canada had experienced 30,377 deaths on New Year’s Day. The US has a much bigger population, so let’s convert these numbers to deaths/1,000,000 population. For the entire epidemic, America has a rate of 2,494 COVID deaths per million compared to 805 Canadian deaths. That means there have been 3.1 American deaths for each Canadian death. Here is how these deaths have accumulated throughout the pandemic.

Cumulative Deaths from COVID: US vs Canada

Cumulative Deaths from COVID: US vs CanadaSuppose that, contrary to fact, Americans had died of COVID at the same rate as Canadians. How many American deaths would have occurred? If you multiply the American population by the Canadian rate, you get 266,409 deaths. This suggests that there have been 825,536 – 266,409 = 559,127 excess deaths in the US, relative to the counterfactual of a ‘Canadian’ pandemic.† This staggering number requires an explanation.

Unfortunately, it’s hard to say why Canada has suffered so much less. Some apparent differences between the two countries probably don’t matter. Canada is colder, but respiratory viruses often thrive in cold climates. Viruses also spread more easily in crowded environments. Canada has a much lower population density than the US; if that is, you calculate that density by dividing the total population by the entire landmass. But that can’t be the right way to do it. The proportions of city dwellers are about the same in the two countries. It is impossible to get infected in most of Canada because it is utterly uninhabited. It’s not clear that the average Canadian is less exposed to her neighbours than an American.§

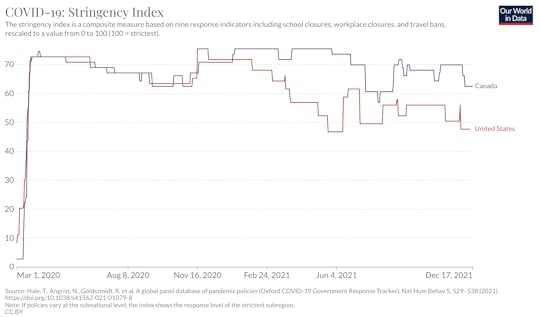

Canadians have, however, adopted and accepted more stringent pandemic control measures than Americans.

How stringent are the pandemic control measures in the US and Canada?

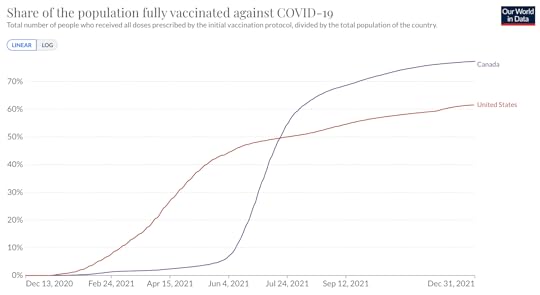

How stringent are the pandemic control measures in the US and Canada?And, despite a slow start, more Canadians are fully vaccinated.

Rates of Full Vaccination, US vs Canada.

Rates of Full Vaccination, US vs Canada.Surprisingly, Canada’s stringent control measures and higher vaccination rate have not resulted in a consistently lower value of the coronavirus’s effective reproduction rate (that’s R, not R0) relative to the US. Notice, however, that the initial spread in the US was substantially faster for unknown reasons. As a result, it might be that the number of US COVID cases/1,000,000 in early March was markedly greater than in Canada. In an exponential growth process, that greater initial size of the infected population would produce higher daily US new cases/1,000,000 throughout the pandemic.

[image error]The Effective Reproduction Rate: US vs Canada.Interestingly, the case fatality rate — the proportion of individuals with COVID who die — has usually been greater in the US, starting about the beginning of 2021. Why? Canadian vaccination rates might contribute to this, but notice that the difference isn’t consistent, and it precedes widespread vaccination in Canada. Canada, however, has universal health care. Perhaps universal health insurance means that Canadians with COVID have been more willing to get tested and seek health care earlier in the course of their illnesses? Getting earlier COVID treatment might lead to less severe disease and a lower fatality rate.

[image error]The Log of the Case Fatality Rate: US vs CanadaSo, I don’t know what specific factors account for the differences between the US and Canadian pandemic death rates. Until we know that, I believe that the package of COVID policies we have adopted here in Canada makes sense, acknowledging that hindsight will likely show that some of the specific policies in that package were unnecessary.

I get it that America is a libertarian culture and that you are willing to pay a price for that freedom (as you understand it). Some other time, let’s talk about striking a balance between individual liberty and the common good. But I ask you, even by your lights, was living without vaccine mandates worth half a million deaths?

*A month later, Epstein said that 500 was a typo, and he had meant to predict 5,000 deaths. This is two orders of magnitude smaller than what happened.

†A better calculation would account for the differences in the age structures of the American and Canadian populations. The proportion of the population 65 and older is slightly larger in Canada than in the US. Because the COVID case fatality rate is so much higher among the elderly, correcting it would make the Canadian death rate look better and the US death rate worse.

§A better way to measure the population density relevant to coronavirus transmission would be to compare the number of neighbours living in, say, a 1 km radius disc surrounding the average citizen in each country. I can’t find that statistic, but it’s possible that the average American’s neighbourhood is more crowded than the average Canadian’s. I’m skeptical that this difference, if it exists, would be sufficient to explain a threefold difference in the cumulative pandemic death rates.

Many thanks to Our World in Data for their extraordinary work curating and visualizing these data.

If you know someone who has cancer, consider sending them a link to this post.To read the Cancer Journal from the start, please begin here.A table of contents for the Cancer Journal is here.To get the Cancer Journal in email, subscribe here.The post Cancer Journal: The COVID Pandemic on New Year’s Day, 2022 first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers