Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 28

February 21, 2022

Healthcare Triage Podcast: What is the Reproducibility Crisis?

This is episode 1 in a special podcast series that focuses on the relationship between science culture and reproducibility. To lay the foundation for that, we first need to discuss the replication crisis: What is it and what are some of the major factors that have come to light in the last decade or so?

Transcript: https://bit.ly/3JxSDtR

If you’re interested in using this series in your undergraduate or graduate courses, free lesson guides are available for each episode at https://www.healthcaretriage.info/reproducibility-podcast

This project was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award number R25GM132785. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The post Healthcare Triage Podcast: What is the Reproducibility Crisis? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.February 18, 2022

Cancer Journal: The Gift of Time

I have recurrent head and neck cancer. A year ago, I received an end-stage diagnosis with a prognosis of months. The surgeons said that the tumour at the base of my tongue was inoperable.

Out in the Canadian winter. The wind causes the redness in my cheeks, but that’s also a side effect of pembrolizumab.

Out in the Canadian winter. The wind causes the redness in my cheeks, but that’s also a side effect of pembrolizumab.Yet here I am this morning, skiing down a trail by the Ottawa River. How and why?

Because we just got the report from my most recent CT scan. In the wretched prose they apparently teach in Med School, the radiologist begins:

The previously described tongue base lesion is not identified. No other soft tissue lesion of the neck identified.

Get it? THEY CAN’T EVEN FIND THE TUMOUR. How did this happen?

Here I should tell you an inspiring story of how I fought on the beaches, fought on the landing grounds, fought in the fields and in the streets, fought in the hills; how I never surrendered and never gave up.

Did I fight? I have worked out every day I’ve been sick (albeit, on the worst days, the workout was just a long dog walk). But all that did was keep me sane. My tumour shrugged off 35 sessions of radiation that killed nearly everything else in my throat. Possibly my pushups entertained it.

What’s killing my tumour is pembrolizumab, the immunotherapeutic drug that the chemotherapy unit drips into my veins every three weeks. It works by disabling the molecular mechanisms whereby the tumour evades my immune system. The drug works only with a small group of people whose immune system is calibrated in just the right way, and I am such a person. The remission is a pure unmerited gift.

How do I go forward from here? The odds are still that cancer will come back to kill me. There are likely a few cells somewhere, multiplying away. If they survive, these cells will eventually evolve a new way to counter my immune system that the pembrolizumab cannot fix. If so, cancer will return.

After having been through an extended period of facing death every day, I’d be a fool to think that “my life is saved.” I have an extension for which I am deeply grateful. I hope I can use it well.

If you know someone who has cancer, consider sending them a link to this post.To read the Cancer Journal from the start, please begin here.A table of contents for the Cancer Journal is here.To get the Cancer Journal in email, subscribe here.The post Cancer Journal: The Gift of Time first appeared on The Incidental Economist.February 17, 2022

New Evidence Suggests a Lack of Cost-Shifting in Prescription Drug Markets

Recent legislative efforts to regulate drug prices have reignited debates about the interaction between price setting in public insurance programs and commercial market spending. In particular, some worry that proposals to regulate drug prices in Medicare will cause drug manufacturers to “make up” lost revenues in the unconstrained commercial market. In this piece, we summarize arguments for and against this theory and present suggestive quantitative evidence from a related context.

The allegation that public insurance price reductions will cause compensatory behavior in the private sector is hardly new in health care. Researchers and practitioners have long debated the existence of “cost shifting” within the provider market—the theory that if public payers reduce payment rates, providers will raise prices on private payers to cover their costs. Economic theory predicts that such behavior is unlikely since it implies providers “leave dollars on the table” in negotiations with private insurers prior to public payer price reductions. Indeed, most recent empirical evidence confirms this, or in some cases, finds that public and private prices move in parallel.

The analogous theory most commonly posited in the drug market is more accurately characterized as a “revenue targeting” strategy, where drug makers alter behavior to achieve a desired level of total product revenues as opposed to covering costs (since revenues of commercially successful products meaningfully exceed fixed costs and variable costs are often modest).

Proponents of this theory implicitly argue that there are features of the drug market that make this kind of compensatory behavior more likely. In particular, they emphasize that drug makers have both intellectual property protection over their products and often face relatively inelastic demand, conferring significant pricing power. In addition, they often point to an empirical reality of drug markets—that the list and net prices of brand drugs increase after a product has been launched—as evidence of unconstrained pricing power.

Opponents of this theory instead argue that these features do not imply the existence of untapped market power and that it is unlikely manufacturers would willingly leave any such market power unused. In particular, inelastic demand and intellectual property protection are features of the current market, meaning that whatever pricing power they convey is already present. Moreover, increasing pricing over time is consistent with profit maximizing behavior in markets where drug makers aim to increase utilization in the early years of a product’s launch and increase prices as patient populations become more established.

That said, we were not aware of any research that bears directly on this debate. In an effort to inform discussions, we (jointly with Conrad Milhaupt) considered whether drug makers engaged in compensatory behavior in a similar setting—when revenues fell owing to the entry of lower-cost biosimilar drugs in the European Union (EU) market, but where drug makers retained monopoly rights in the unregulated portion of the US market. Our analysis focused on four large biologic products that met all sample criteria.

While this is an international setting, it shares many similarities with price regulation specific to Medicare in the US. EU biosimilar entry has substantial effects on global revenues, which are the ultimate focus of for-profit manufacturers considered here. Indeed, executive pay was even formally linked to global sales of one analyzed product (Humira), providing an explicit incentive to offset losses if possible. Moreover, manufacturers held the same market power in the commercial market following these revenue reductions as they would following losses in the Medicare market (and in our setting, could have increased revenues in the Medicare market too).

In short, biosimilar entry in the EU caused sharp reductions to global revenue but we observe little evidence of offsetting revenue increases in the US market relative to prior trend.

These results are consistent with the theory that drug makers are already using their market power in full. At a minimum, revenue targeting arguments must contend with the reality that firms appear willing to accept revenue losses internationally, despite holding similar market power in the US commercial market as they would in the wake of Medicare price regulation.

As this conversation continues, it is important to distinguish that cross-market effects would be expected if drug policy proposals create direct linkages between two markets. For example, tying prices in one market to those in another, as the Trump Administrations International Pricing Index would have, creates a shadow cost of lower prices in reference countries. Thus, the economics underpinning pricing decisions in both markets would change and cross-market effects do not rely on a “revenue targeting” theory.

The post New Evidence Suggests a Lack of Cost-Shifting in Prescription Drug Markets first appeared on The Incidental Economist.February 16, 2022

Science Culture and Reproducibility on the Healthcare Triage Podcast

Most people agree that there’s a major problem with reproducibility of scientific studies. In fact, it’s been estimated that as much as HALF of scientific studies are producing results that cannot be replicated. We wanted to know more about this problem, what is contributing to it, and how we can fix it.

So, thanks to support from the National Institutes of Health, we’ve created a special, 8-episode podcast series on this topic: Science culture and reproducibility.

We talk to funders, journalists, and scientists from various backgrounds and at various career stages to try and outline what the issues are. We spend an episode digging into the incentives built into the system of academia and the pressure on scientists to produce big, splashy, positive results. We touch on the often troubled ways in which we use statistics. We zero in on grant writing and funding practices and the ways in which universities depend on their faculty getting grants. We pick apart journals, peer-review, and publishing practices and expectations as a whole, highlighting our problematic obsession with bibliometrics. We examine the role the media has to play in science culture and in holding science accountable, and we ask questions about the way we mentor young scientists, including the pressures they face and the career options for which they’re trained. And then after all that we ask our experts: What can we do about it?

As of today the first 3 episodes are available on our website or anywhere you get your podcasts. The remaining episodes will drop one per week from here on out. We’ve also created free, downloadable lesson guides (also available on our website) if you’d like to take this discussion to the classroom or to your lab meetings. There are also comment sections on the website if you’d like to start a discussion there. And if you like the series, share it far and wide!

The post Science Culture and Reproducibility on the Healthcare Triage Podcast first appeared on The Incidental Economist.February 15, 2022

Most Americans Exercise. What About You?

Is that video title going to convince you to exercise? MEGASTUDY alert. The term megastudy is a pretty new one to us, and we like it. Basically, a MEGASTUDY is a group of large randomized controlled trials run simultaneously to explore multiple questions. Today, we’re talking about a MEGASTUDY on exercise and the ways we encourage people to be more active. Some of the ways that were effective and the ways they worked surprised us. For example, just telling a group of participants that most Americans exercise regularly was enough to increase visits to the gym.

The post Most Americans Exercise. What About You? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.HSR: Call for commentary proposals to expand the diversity of topics and voices

This call is also posted on the HSR website.

Health Services Research (HSR) publishes two types of commentaries in most issues: those discussing a research article in the same issue and stand-alone commentaries that are not tied to another article in the issue. With an ambition to expand the diversity of topics and voices that are typically underrepresented in health services research while remaining true to the HSR mission including relevance to U.S. health care policy and practice, we are calling for proposals for stand-alone commentaries.

A proposal for a stand-alone commentary should take the form of a brief (300-word maximum) summary of the issue you wish to address. As all commentaries must be evidence-based, this summary should indicate at least some of the research on which it draws (references do not count toward the word limit). The summary should be accompanied by a statement (not counting toward the word limit) of how the proposed commentary would further HSR’s ambition articulated above — to expand the diversity of topics and voices while remaining true to the HSR mission.

Proposed summaries will be evaluated by the editors based on the:

suitability of the topic for HSRdegree to which it advances the goal indicated above to expand diversity, including (but not limited to) around age, career-stage, race and ethnicity, educational or socioeconomic status, gender identity or sexual orientation, and lived-experience with health servicessalience or urgency of the topicextent to which the perspective of the author is evidence-basednovelty of the topic relative to other, recent commentaries in the journalPlease consult the author instructions for general criteria about suitable content for the journal, as well as other stylistic guidance. This example may serve as a stylistic model. The author instructions also indicate the requirements for full-length commentaries. Note as well that HSR has limited space for stand-alone commentaries (about one per issue), so many worthy commentaries may not be invited for this reason.

Editors will notify authors by email with a decision about the proposed commentary. Due to space limitations, invited commentaries may not appear in a print issue for some months after acceptance, though they will be posted online within weeks of acceptance. Submit proposals to hsr@aha.org.

The post HSR: Call for commentary proposals to expand the diversity of topics and voices first appeared on The Incidental Economist.February 10, 2022

Cancer Journal: Not to Hope

Last February, my surgeon told me that I had “months, not years,” and no further treatment options were available.

Today, February 10, 2022, I skied 5 kilometres. Pathetic, by the standards of my youth, which only shows how warped those standards were. Gratitude is all I feel today, and it was likewise the appropriate emotion 50 years ago.

You might expect me to quote Churchill,

Never, never, never, never–in nothing, great or small, large or petty–never give in.

And that you shouldn’t listen to a doctor who says you are going to die.

No. Listen to doctors. Don’t be bitter if they tell you things you do not want to hear, not even if reality proves them wrong. Physicians make mistakes and work in broken systems that no one knows how to fix.

If you are told there are no more options, but you think you can still live, by all means, seek other medical opinions.

However, never giving up is delusional. I will die; there will be a time when the right choice is acceptance. Or surrender if the process isn’t going well.

Am I counselling you to be hopeless? I hope not, but I am saying to be careful to hope for the right thing. I have this moment, not forever: What should I hope for right now?

If you know someone who has cancer, consider sending them a link to this post.To read the Cancer Journal from the start, please begin here.A table of contents for the Cancer Journal is here.To get the Cancer Journal in email, subscribe here.The post Cancer Journal: Not to Hope first appeared on The Incidental Economist.February 6, 2022

2021 Shkreli Awards: The 10 Worst Examples of Healthcare Profiteering and Dysfunction

Each year, the Lown Institute gives out the Shkreli Awards, named for disgraced and imprisoned “Pharma Bro” Martin Shkreli. The awards go to the perpetrators of the most egregious examples of dysfunction and profiteering in healthcare. To be clear, these are not awards that anyone hopes to win. The whole bit serves as an opportunity to examine ways that the American health system puts profit over patients and organizes healthcare in ways that are bad for both patients and front-line health workers. Enjoy seething at this list of the 10 worst.

The post 2021 Shkreli Awards: The 10 Worst Examples of Healthcare Profiteering and Dysfunction first appeared on The Incidental Economist.February 4, 2022

*DEADLINE EXTENDED* | Call for Abstracts: Reproductive Wellness for Women with Chronic Conditions

This call is also posted on the Health Services Research website.

Sponsored by: The WK Kellogg Foundation

Submission deadline for abstracts: February 4, 2022 February 14, 2022

With sponsorship from The WK Kellogg Foundation, Health Services Research (HSR), the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) Jordan Institute for Families and the UNC Collaborative for Maternal and Infant Health are partnering to publish a series of special sections of upcoming issues focused on reproductive wellness for women with chronic conditions. The special sections will be edited by HSR’s team of Senior Associate Editors and Editor-in-Chief, with co-editor guidance from Sarah Verbiest, DrPH, MSW, MPH, and Natalie Hernandez, PhD, MPH.

These special sections will focus on reproductive wellness and preconception care for women with chronic conditions. Recent work listening to women of color with chronic conditions has underscored many gaps in care. These gaps contribute to maternal mortality and morbidity, infertility, miscarriage and infant loss, and long-term health impacts for women and their families. We are seeking to curate a series of articles, to be published in a special section across several regular HSR issues, that will highlight work being done across a variety of sectors — health care, public health, social work, community leadership, maternal and child health, chronic disease, and others — that offers solutions and strategies toward improving care.

We hope to receive abstract proposals from a range of disciplines and organizations, including community-based organizations and community leaders, and strongly encourage and welcome abstracts from community-based organizations and community leaders. From abstracts received, the editors will invite manuscripts, which will undergo peer review. Topics of interest include qualitative analysis of experience of care; quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods research revealing outcomes of current models of care, promising practices, partnership approaches, or strategies to foster equity; exploration of new data or measurements pertaining to reproductive wellness for women with chronic conditions. Articles may include in their discussions evidence-based recommendations for systems and/or policy change. We welcome abstracts from community-led organizations. If the abstracts are moved forward, the UNC Jordan Institute for Families can offer some writing assistance for these organizations. Geographically, articles should be focused on studies or initiatives within the United States. All articles in the special sections will be open access.

The deadline for abstract submissions is February 4, 2022 February 14, 2022. Abstracts may not exceed 300 words and must be formatted as indicated in the HSR Author Guidelines. These abstracts will be evaluated by a multidisciplinary review panel that will select authors to receive invitations to submit full manuscripts. The evaluation criteria will include: (1) responsiveness to the themes articulated in this call; (2) quality, rigor and originality; and (3) significance and usefulness for advancing knowledge.

Manuscripts invited for submission will undergo the same HSR peer review process as all regular manuscripts. All accepted articles will be published electronically within a few weeks of acceptance using Wiley’s Early View process. Articles published through Early View are fully published, appear in PubMed, and can be cited. Approximately 12 articles will be subsequently selected for print publication in a special section of a regular issue of HSR that will appear in several issues between December 2022 and December 2023. Accepted manuscripts that are not selected for the Special Sections will be automatically scheduled for print publication in a regular issue.

Key dates for authorsFriday, February 4, 2022 February 14, 2022: Abstracts submission deadlineFriday, March 4, 2022: Notification of manuscript invitationFriday, June 3, 2022: Manuscripts submission deadlineDecember 2022-December 2023: Publication of manuscripts in special sections of regular HSR issuesIf you would like to submit your abstract for consideration, please email your abstract and co-author contact information to the editorial office at hsr@aha.org, using the subject line “Special Section on Reproductive Wellness for Women with Chronic Conditions.”

The post *DEADLINE EXTENDED* | Call for Abstracts: Reproductive Wellness for Women with Chronic Conditions first appeared on The Incidental Economist.February 1, 2022

Employer-Sponsored Insurance: Friend or Foe?

This article is part of an educational video series created by BUSPH student, Tasha McAbee, and health economist, Dr. Austin Frakt, to explain the intersections of economics and health. The transcript follows the video below, which can also be found on YouTube at Health Economics Explainers.

The Covid-19 pandemic caused a sudden and drastic rise in unemployment.

For most non-elderly working individuals in the United States, losing employment means also losing, or at least disrupting, their access to affordable health insurance. As a result, the pandemic resurfaced discussions about our long-standing relationship with employer-sponsored insurance. Is it time to sever that tie? What would happen to individual costs if employees no longer got health insurance through their employers?

The employer sponsored insurance system that accounts for half of the US population’s source of health care coverage began in the late 1920s when a small proportion of employers assisted people struggling to cover rising healthcare costs. Then, during World War II, employers were unable to increase salaries due to a federal freeze on wages, so, instead, more of them began offering assistance with health insurance as a benefit to their workers. In 1943, the IRS made this benefit tax-free, meaning employers and employees kick in money for coverage before it is hit with federal income and payroll taxes. This “tax subsidy” effectively makes insurance cheaper, but it has other effects that are problematic.

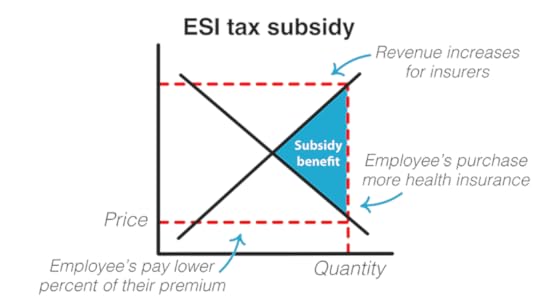

What exactly is a tax subsidy and how does it work? Principles of economics tell us that in a competitive, free market, the price of a good or service, in this case a health insurance plan, is determined by the market equilibrium, where supply meets demand.

The tax break is a subsidy that allows the price offered to consumers to decrease — because the government is picking up part of the tab. And when consumers’ prices drop, the amount of health insurance purchased increases. In the case of health care coverage, more employees purchase health insurance plans through their employer.

This, in turn, increases revenue to insurance providers. They, along with the employer and the employee benefit from the subsidy.

The savings are substantial – an estimated $303 billion in 2021 alone that would otherwise be taxes. To put this in perspective, the government could fund universal paid family leave for an entire decade with just $225 billion. In addition to this large loss in federal revenue, there are other problems with the tax subsidy. One is job lock, where people feel they cannot leave a position due to the risk of losing their access to affordable health insurance. Another is inherent inequity in the system — the employer sponsored insurance tax subsidy does not benefit everyone equally.

Because taxes are percentage-based calculations, those with higher wages benefit more from this system. Take for instance, two employees, both part of their employer sponsored health insurance plan that includes a $1,000 monthly premium before the subsidy is taken into account. Once the tax break is applied, the lower wage employee, who falls in the 12% income tax bracket saves $254, paying $746 while the higher paid employee saves $347, only paying $653.

Said another way, the subsidy compounds the inequality faced by lower-income workers, who are already paying a higher percentage of their income on health insurance than higher-income workers. In 2017, those earning around $40,000 in annual income paid around 14% of their income on health insurance, in premiums and out-of-pocket costs combined, while those making over $80,000 only had to put 4.5% of their income towards health insurance.

Not only that, but the disparity between low and high income workers is widening, just as overall employee contribution to health care expenses is increasing at a higher rate than employer contribution, wages, and inflation.

There are problems with our current system and in general with tying health insurance to employment. But if we get rid of the subsidy benefit, wouldn’t our individual health care costs and premiums rise? While it’s true that if the employer sponsored insurance tax subsidy disappeared, the price of health plans would return to market equilibrium, there are other ways to subsidize coverage without going through employers. This is what the Affordable Care Act aimed to achieve by offering individual subsidies through the public marketplace for health plans. These tax credit subsidies similarly work on a sliding scale based on annual income, but flipped around from the employer sponsored insurance tax subsidy. The ACA tax credits are designed to benefit low-income individuals more, instead of benefiting those with higher wages, as with employer sponsored insurance. The lower one’s income, the greater the tax break, and as of 2021, there is no income cutoff on eligibility for a subsidy.

If you take our example from earlier, comparing two people, each with a $1,000 premium, the lower wage employee pays a smaller percentage of their income for health insurance than the higher wage employee under the ACA’s tax credit program.

While removing the tax break on employer sponsored insurance would, by itself, increase the cost of coverage to individuals and families, the government could then use that large sum of money to help people cover costs in a more equitable way that doesn’t tie coverage to employment. And as we saw with the Covid-19 pandemic, there are plenty of reasons why we may want to someday make this kind of change.

The post Employer-Sponsored Insurance: Friend or Foe? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers